Temnodontosaurus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

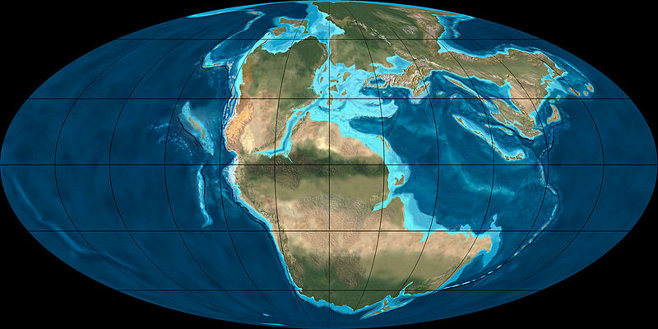

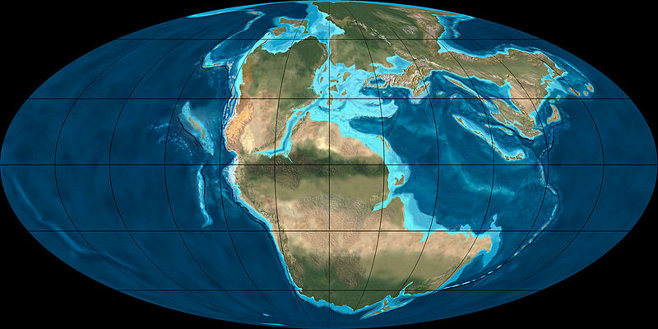

''Temnodontosaurus'' (meaning "cutting-tooth lizard") is an

In 1889, Henry Alleyne Nicholson and

In 1889, Henry Alleyne Nicholson and

In 1880, Harry Govier Seeley described the species ''I. zetlandicus'' on the basis of a well-preserved skull loaned by an

In 1880, Harry Govier Seeley described the species ''I. zetlandicus'' on the basis of a well-preserved skull loaned by an

In 1892, Albert Gaudry officially described a new species of ''Ichthyosaurus'', ''I. burgundiae'', on the basis of a specimen discovered in the quarries of the town of Sainte-Colombe, in

In 1892, Albert Gaudry officially described a new species of ''Ichthyosaurus'', ''I. burgundiae'', on the basis of a specimen discovered in the quarries of the town of Sainte-Colombe, in  In 1974, McGowan described an additional species of ''Temnodontosaurus'', ''T. risor'', based on three skulls discovered at Lyme Regis, designating NHMUK PV R43971 as the holotype specimen. The specific name of this taxon comes from the

In 1974, McGowan described an additional species of ''Temnodontosaurus'', ''T. risor'', based on three skulls discovered at Lyme Regis, designating NHMUK PV R43971 as the holotype specimen. The specific name of this taxon comes from the

One of the earliest representations of ''Temnodontosaurus'' in paleoart is a life-size concrete sculpture created by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins between 1852 and 1854, as part of the collection of sculptures of prehistoric animals on display at the

One of the earliest representations of ''Temnodontosaurus'' in paleoart is a life-size concrete sculpture created by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins between 1852 and 1854, as part of the collection of sculptures of prehistoric animals on display at the

''Temnodontosaurus'' is one of the largest ichthyosaurs identified to date, although the species which belong to it are not as imposing as

''Temnodontosaurus'' is one of the largest ichthyosaurs identified to date, although the species which belong to it are not as imposing as

The forefins and hindfins of ''Temnodontosaurus'' were of roughly the same length and were rather narrow and elongated. This characteristic is unlike other post-Triassic ichthyosaurs such as the

The forefins and hindfins of ''Temnodontosaurus'' were of roughly the same length and were rather narrow and elongated. This characteristic is unlike other post-Triassic ichthyosaurs such as the

The majority of the currently recognized species of ''Temnodontosaurus'' were originally described as species of ''Ichthyosaurus'', before the type species ''T. platyodon'' was moved to a separate genus in 1889 by Lydekker. In 1974, McGowan established the

The majority of the currently recognized species of ''Temnodontosaurus'' were originally described as species of ''Ichthyosaurus'', before the type species ''T. platyodon'' was moved to a separate genus in 1889 by Lydekker. In 1974, McGowan established the

There is fossil evidence that ''Temnodontosaurus'' engaged in aggressive combat, possibly with other members of its own genus. Several specimens exhibit healed traumatic injuries that were likely inflicted by other large marine reptiles. A particular specimen of ''T. trigonodon'' (SMNS 15950) exhibits ten roughly circular areas separated by only a few centimeters, suggesting that it was bitten by a large marine reptile with a long rostrum. The size and location of these injuries suggest that it was either attacked by another ''T. trigonodon'' or by a thalattosuchian similar to the contemporary '' Steneosaurus''. Two other specimens, including the holotype of ''T. nuertingensis'', exhibit deep wounds in the most posterior part of the mandible. Both specimens also exhibit healed wounds ventral to the

There is fossil evidence that ''Temnodontosaurus'' engaged in aggressive combat, possibly with other members of its own genus. Several specimens exhibit healed traumatic injuries that were likely inflicted by other large marine reptiles. A particular specimen of ''T. trigonodon'' (SMNS 15950) exhibits ten roughly circular areas separated by only a few centimeters, suggesting that it was bitten by a large marine reptile with a long rostrum. The size and location of these injuries suggest that it was either attacked by another ''T. trigonodon'' or by a thalattosuchian similar to the contemporary '' Steneosaurus''. Two other specimens, including the holotype of ''T. nuertingensis'', exhibit deep wounds in the most posterior part of the mandible. Both specimens also exhibit healed wounds ventral to the

extinct

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

of large ichthyosaurs

Ichthyosauria is an taxonomy (biology), order of large extinction, extinct marine reptiles sometimes referred to as "ichthyosaurs", although the term is also used for wider clades in which the order resides.

Ichthyosaurians thrived during much of ...

that lived during the Lower Jurassic in what is now Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

and possibly Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in western South America. It is the southernmost country in the world and the closest to Antarctica, stretching along a narrow strip of land between the Andes, Andes Mountains and the Paci ...

. The first known fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

is a specimen consisting of a complete skull

The skull, or cranium, is typically a bony enclosure around the brain of a vertebrate. In some fish, and amphibians, the skull is of cartilage. The skull is at the head end of the vertebrate.

In the human, the skull comprises two prominent ...

and partial skeleton

A skeleton is the structural frame that supports the body of most animals. There are several types of skeletons, including the exoskeleton, which is a rigid outer shell that holds up an organism's shape; the endoskeleton, a rigid internal fra ...

discovered on a cliff

In geography and geology, a cliff or rock face is an area of Rock (geology), rock which has a general angle defined by the vertical, or nearly vertical. Cliffs are formed by the processes of weathering and erosion, with the effect of gravity. ...

by Joseph and Mary Anning

Mary Anning (21 May 1799 – 9 March 1847) was an English fossil collector, fossil trade, dealer, and palaeontologist. She became known internationally for her discoveries in Jurassic marine fossil beds in the cliffs along the English Cha ...

around the early 1810s in Dorset

Dorset ( ; Archaism, archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by Somerset to the north-west, Wiltshire to the north and the north-east, Hampshire to the east, t ...

, England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

. The anatomy of this specimen was subsequently analyzed in a series of articles written by Sir Everard Home between 1814 and 1819, making it the very first ichthyosaur to have been scientifically described. In 1822, the specimen was assigned to the genus '' Ichthyosaurus'' by William Conybeare, and more precisely to the species ''I. platyodon''. Noting the large dental differences with other species of ''Ichthyosaurus'', Richard Lydekker

Richard Lydekker (; 25 July 1849 – 16 April 1915) was a British naturalist, geologist and writer of numerous books on natural history. He was known for his contributions to zoology, paleontology, and biogeography. He worked extensively in cata ...

suggested in 1889 moving this species into a separate genus, which he named ''Temnodontosaurus''. While many species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

have been assigned to the genus, only five are currently recognized as valid, the others being considered as synonymous

A synonym is a word, morpheme, or phrase that means precisely or nearly the same as another word, morpheme, or phrase in a given language. For example, in the English language, the words ''begin'', ''start'', ''commence'', and ''initiate'' are a ...

, doubtful or possibly belonging to other taxa

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; : taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular name and ...

.

Generally estimated at long, ''Temnodontosaurus'' is one of the largest known ichthyosaurs, although not as imposing as some Triassic

The Triassic ( ; sometimes symbolized 🝈) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.5 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.4 Mya. The Triassic is t ...

forms. Specimens assigned to the genus may nevertheless have reached larger measurements. As an ichthyosaur, ''Temnodontosaurus'' had flippers for limbs and a fin on the tail. Boasting eye socket

In anatomy, the orbit is the cavity or socket/hole of the skull in which the eye and its appendages are situated. "Orbit" can refer to the bony socket, or it can also be used to imply the contents. In the adult human, the volume of the orbit is ...

s measuring more than wide, ''Temnodontosaurus'' quite possibly had the largest eye

An eye is a sensory organ that allows an organism to perceive visual information. It detects light and converts it into electro-chemical impulses in neurons (neurones). It is part of an organism's visual system.

In higher organisms, the ey ...

s known in the entire animal kingdom, rivaling in size those of the colossal squid. The snout

A snout is the protruding portion of an animal's face, consisting of its nose, mouth, and jaw. In many animals, the structure is called a muzzle, Rostrum (anatomy), rostrum, beak or proboscis. The wet furless surface around the nostrils of the n ...

appears to be longer than the mandible

In jawed vertebrates, the mandible (from the Latin ''mandibula'', 'for chewing'), lower jaw, or jawbone is a bone that makes up the lowerand typically more mobilecomponent of the mouth (the upper jaw being known as the maxilla).

The jawbone i ...

, being equipped with several sharp teeth (hence its name). On the basis of numerous very complete skeletons, it is estimated that the animal had at least more than 40 presacral vertebrae. ''Temnodontosaurus'' is a basal representative of the parvipelvia

Parvipelvia (Latin for "little pelvis" - ''parvus'' meaning "little" and ''pelvis'' meaning "pelvis") is an extinct clade of euichthyosaur ichthyosaurs that existed from the Late Triassic to the early Late Cretaceous (middle Norian to Cenomanian ...

n subgroup of ichthyosaurs, in addition to being its largest representative. A monotypic

In biology, a monotypic taxon is a taxonomic group (taxon) that contains only one immediately subordinate taxon. A monotypic species is one that does not include subspecies or smaller, infraspecific taxa. In the case of genera, the term "unisp ...

family

Family (from ) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictabili ...

, Temnodontosauridae, was even established in 1974 to include the genus. Various phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics () is the study of the evolutionary history of life using observable characteristics of organisms (or genes), which is known as phylogenetic inference. It infers the relationship among organisms based on empirical dat ...

analyses as well as diagnostic problems concerning the genus make it, for the moment, a polyphyletic

A polyphyletic group is an assemblage that includes organisms with mixed evolutionary origin but does not include their most recent common ancestor. The term is often applied to groups that share similar features known as Homoplasy, homoplasies ...

taxon (unnatural grouping), and therefore in need of revision.

Research history

Discovery and identification

''Temnodontosaurus'' is historically the very firstichthyosaur

Ichthyosauria is an order of large extinct marine reptiles sometimes referred to as "ichthyosaurs", although the term is also used for wider clades in which the order resides.

Ichthyosaurians thrived during much of the Mesozoic era; based on fo ...

to have been scientifically described. Around 1810, a certain Joseph Anning discovered the first skull of the taxon

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; : taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular name and ...

on the cliff

In geography and geology, a cliff or rock face is an area of Rock (geology), rock which has a general angle defined by the vertical, or nearly vertical. Cliffs are formed by the processes of weathering and erosion, with the effect of gravity. ...

s of Black Ven, between the town of Lyme Regis

Lyme Regis ( ) is a town in west Dorset, England, west of Dorchester, Dorset, Dorchester and east of Exeter. Sometimes dubbed the "Pearl of Dorset", it lies by the English Channel at the Dorset–Devon border. It has noted fossils in cliffs and ...

and the village of Charmouth

Charmouth is a village and civil parish in west Dorset, England. The village is situated on the mouth of the River Char, around north-east of Lyme Regis. Dorset County Council estimated that in 2013 the population of the civil parish was 1,31 ...

, two localities located in the county

A county () is a geographic region of a country used for administrative or other purposesL. Brookes (ed.) '' Chambers Dictionary''. Edinburgh: Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, 2005. in some nations. The term is derived from the Old French denoti ...

of Dorset

Dorset ( ; Archaism, archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by Somerset to the north-west, Wiltshire to the north and the north-east, Hampshire to the east, t ...

, in the south of England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

. The remaining skeleton was later discovered by his sister, the now famous Mary Anning

Mary Anning (21 May 1799 – 9 March 1847) was an English fossil collector, fossil trade, dealer, and palaeontologist. She became known internationally for her discoveries in Jurassic marine fossil beds in the cliffs along the English Cha ...

, in 1812. Although other ichthyosaur skeletons had been discovered locally and elsewhere, this particular specimen was the first to attract attention of the scientific community

The scientific community is a diverse network of interacting scientists. It includes many "working group, sub-communities" working on particular scientific fields, and within particular institutions; interdisciplinary and cross-institutional acti ...

. After the discovery was announced in the press, the specimen was purchased by the lord of a local manor, Henry Hoste Henley, for a price of £23. Subsequently, Henley passed the fossils on to the naturalist William Bullock, who put them on display in the collections of his museum in London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

. In 1819, Bullock's own collection was sold to the Natural History Museum in London for a price of around £47. The specimen, now cataloged as NHMUK PV R1158, is still currently housed at this museum, although the postcranial remains have since been lost.

Beginning in 1814, Sir Everard Home wrote a series of six papers for the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

describing the specimen, initially identifying it as a crocodile

Crocodiles (family (biology), family Crocodylidae) or true crocodiles are large, semiaquatic reptiles that live throughout the tropics in Africa, Asia, the Americas and Australia. The term "crocodile" is sometimes used more loosely to include ...

. Perplexed as to the real nature of the fossil, Home kept changing his mind about its classification, thinking that it would be a fish, then as an animal sharing affinities with the platypus

The platypus (''Ornithorhynchus anatinus''), sometimes referred to as the duck-billed platypus, is a semiaquatic, egg-laying mammal endemic to eastern Australia, including Tasmania. The platypus is the sole living representative or monotypi ...

, which was then recently described at that time. Finally, in 1819, he thought that the fossil represented an animal that embodied an intermediate form between salamander

Salamanders are a group of amphibians typically characterized by their lizard-like appearance, with slender bodies, blunt snouts, short limbs projecting at right angles to the body, and the presence of a tail in both larvae and adults. All t ...

s and lizard

Lizard is the common name used for all Squamata, squamate reptiles other than snakes (and to a lesser extent amphisbaenians), encompassing over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most Island#Oceanic isla ...

s, which led him to erect the genus name ''Proteosaurus'' (originally written as ''Proteo-Saurus''). In 1821, Henry De la Beche

Sir Henry Thomas De la Beche KCB, FRS (10 February 179613 April 1855) was an English geologist and palaeontologist, the first director of the Geological Survey of Great Britain, who helped pioneer early geological survey methods. He was the ...

and his colleague William Daniel Conybeare made the very first scientific description of '' Ichthyosaurus'', but did not name any species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

. Although being initially a ''nomen nudum

In Taxonomy (biology), taxonomy, a ''nomen nudum'' ('naked name'; plural ''nomina nuda'') is a designation which looks exactly like a scientific name of an organism, and may have originally been intended to be one, but it has not been published ...

'', this generic name was already proposed in 1818 by Charles Konig

Charles Dietrich Eberhard Konig or Karl Dietrich Eberhard König, Royal Guelphic Order, KH (1774 – 6 September 1851) was a German natural history, naturalist.

He was born in Braunschweig, Brunswick and educated at University of Göttingen, ...

, but was thus chosen as the definitive scientific name

In Taxonomy (biology), taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, both of which use Latin gramm ...

of this genus, ''Proteosaurus'' having since become a ''nomen oblitum

In zoological nomenclature, a ''nomen oblitum'' (plural: ''nomina oblita''; Latin for "forgotten name") is a disused scientific name which has been declared to be obsolete (figuratively "forgotten") in favor of another "protected" name.

In its pr ...

''. In their article, De la Beche and Conybeare refer several additional fossils discovered at Black Ven to this genus, also including the specimen originally described by Home, and finally identify it as a marine reptile

Marine reptiles are reptiles which have become secondarily adapted for an aquatic or semiaquatic life in a marine environment. Only about 100 of the 12,000 extant reptile species and subspecies are classed as marine reptiles, including mari ...

. It was in 1822 that De la Beche named three species of ''Ichthyosaurus'' on the basis of several anatomical differences distinguishing the specimens, one of them being ''I. platyodon''. He nevertheless announces that future descriptions will be done with the help of Conybeare. However, it was Conybeare himself who described the fossils the same year, attributing the largest specimens to ''I. platyodon'', The specific name Specific name may refer to:

* in Database management systems, a system-assigned name that is unique within a particular database

In taxonomy, either of these two meanings, each with its own set of rules:

* Specific name (botany), the two-part (bino ...

''platyodon'' comes from the Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

(, "flat", "broad"), and (, "tooth"), all meaning "flat teeth", in reference to the rather distinctive dentition of this species.

In 1889, Henry Alleyne Nicholson and

In 1889, Henry Alleyne Nicholson and Richard Lydekker

Richard Lydekker (; 25 July 1849 – 16 April 1915) was a British naturalist, geologist and writer of numerous books on natural history. He was known for his contributions to zoology, paleontology, and biogeography. He worked extensively in cata ...

published a two-volume work that served as an introduction to the rules of paleontology

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure ge ...

for students. However, it is in the second volume that the two paleontologists gave a very detailed description of numerous prehistoric vertebrate

Vertebrates () are animals with a vertebral column (backbone or spine), and a cranium, or skull. The vertebral column surrounds and protects the spinal cord, while the cranium protects the brain.

The vertebrates make up the subphylum Vertebra ...

s, and during which the taxonomy

image:Hierarchical clustering diagram.png, 280px, Generalized scheme of taxonomy

Taxonomy is a practice and science concerned with classification or categorization. Typically, there are two parts to it: the development of an underlying scheme o ...

of ''I. platyodon'' took another direction. Indeed, in his correction notes, Lydekker noticed that the teeth of ''I. platyodon'' had great differences from those of other previously recognized species of ''Ichthyosaurus'' and suggest that the latter could be the type species

In International_Code_of_Zoological_Nomenclature, zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the spe ...

of a completely new genus of ichthyosaurs, which he named ''Temnodontosaurus''. This generic name is formed from the Ancient Greek (, "to cut"), (, "tooth"), and (''saûros'', "lizard"), to give "cutting-tooth lizard". In a broad review of fossil vertebrates published in 1902, Oliver Perry Hay

Oliver Perry Hay (May 22, 1846 – November 2, 1930) was an American herpetologist, ichthyologist, and paleontologist.

Hay was born in Jefferson County, Indiana, to Robert and Margaret Hay. In 1870, Hay graduated with a bachelor of arts from ...

suggested that because the name ''Proteosaurus'' technically took precedence over ''Ichthyosaurus'', he then displaced ''I. platyodon'' as the type species of that genus, then renamed ''Proteosaurus platyodon''. In 1972, Christopher McGowan again used this combination proposed by Hay (although not mentioned), but the latter revised his judgment two years later, in 1974, in which he moved this species to ''Temnodontosaurus'', as originally proposed by Lydekker. The holotype

A holotype (Latin: ''holotypus'') is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of s ...

of ''Temnodontosaurus platyodon'' consisted of a single tooth which was preserved by the Geological Society of London

The Geological Society of London, known commonly as the Geological Society, is a learned society based in the United Kingdom. It is the oldest national geological society in the world and the largest in Europe, with more than 12,000 Fellows.

Fe ...

. As the latter has since been noted as lost in 1960, McGowan designated specimen NHMUK PV R2003 as the neotype

In biology, a type is a particular specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally associated. In other words, a type is an example that serves to anchor or centralizes ...

of this taxon

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; : taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular name and ...

. This specimen, already mentioned as a representative of the species by Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

in 1881, was originally discovered and partly collected by Mary Anning in July 1832 in Lyme Regis. After the discovery, she sold the find to Thomas Hawkins, who himself sold the specimen to the Natural History Museum in London in 1834 for a price of £210.

Other species

Recognized species

In 1843, described a new species of ''Ichthyosaurus'', ''I. trigonodon'', which he described as "colossal", based on an imposing specimen comprising a complete skull and a partial postcranial skeleton discovered in the town ofHolzmaden

Holzmaden is a town in Baden-Württemberg, Germany that lies between Stuttgart and Ulm.

Holzmaden is 4 km south-east from Kirchheim unter Teck and 19 km south-east of Esslingen am Neckar. The A 8 runs south from Holzmaden. The town a ...

in the state

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

of Baden-Württemberg

Baden-Württemberg ( ; ), commonly shortened to BW or BaWü, is a states of Germany, German state () in Southwest Germany, east of the Rhine, which forms the southern part of Germany's western border with France. With more than 11.07 million i ...

, Germany. The specific name comes from Ancient Greek (, "triangle

A triangle is a polygon with three corners and three sides, one of the basic shapes in geometry. The corners, also called ''vertices'', are zero-dimensional points while the sides connecting them, also called ''edges'', are one-dimension ...

") and (, "tooth"), in reference to the dental crown which is visibly triangular in this species. In 1854, von Theodori made a much more in-depth description of the holotype specimen. In 1889, only some time before he established the genus ''Temnodontosaurus'', Lydekker noted that the dentition of ''I. trigonodon'' was quite similar to that of ''I. platyodon''. Based on these dental characteristics, he moved this species to the genus ''Temnodontosaurus'' the following year, consequently being renamed ''T. trigonodon''. In 1931, Friedrich von Huene transferred this species to the genus ''Leptopterygius''. In 1998, Michael W. Maisch moved the species again to the genus ''Temnodontosaurus'', and attributed to this taxon other, mostly very complete, specimens having been discovered in Germany and France. This classification has since been retained in subsequent works, to the point that a large specimen discovered in England in 2021, nicknamed as the ‘Rutland

Rutland is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands of England. It borders Leicestershire to the north and west, Lincolnshire to the north-east, and Northamptonshire to the south-west. Oakham is the largest town and county town.

Rutland has a ...

Sea Dragon’, was even considered as the first probable representative within this country. However, a 2023 morphological study conducted by Rebecca F. Bennion and colleagues shows that the holotype specimen differs in cranial and dental traits from other specimens since assigned to the species. The authors therefore suggest that a future re-evaluation is necessary for better a diagnosis

Diagnosis (: diagnoses) is the identification of the nature and cause of a certain phenomenon. Diagnosis is used in a lot of different academic discipline, disciplines, with variations in the use of logic, analytics, and experience, to determine " ...

of ''T. trigonodon''.

In 1857, an almost complete skeleton of a large ichthyosaur was discovered north of Whitby

Whitby is a seaside town, port and civil parish in North Yorkshire, England. It is on the Yorkshire Coast at the mouth of the River Esk, North Yorkshire, River Esk and has a maritime, mineral and tourist economy.

From the Middle Ages, Whitby ...

, Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ) is an area of Northern England which was History of Yorkshire, historically a county. Despite no longer being used for administration, Yorkshire retains a strong regional identity. The county was named after its county town, the ...

. The latter was also found near another skeleton, that of a pliosaur, which is today recognized as the holotype specimen of '' Rhomaleosaurus cramptoni''. Shortly after its discovery, the ichthyosaurian skeleton was subsequently sent to the Yorkshire Museum

The Yorkshire Museum is a museum in York, England. It was opened in 1830, and has five permanent collections, covering biology, geology, archaeology, numismatics and astronomy.

History

The museum was founded by the Yorkshire Philosophical Soci ...

, where it was cataloged as YORYM 497. The following year, 1858, Owen examined the specimen and classified it as distinct from ''I. platyodon'', attributing it to a completely new species which he named ''I. crassimanus''. However, the latter was never scientifically described by Owen, although it is briefly mentioned in a work by John Phillips and Robert Etheridge published in 1875. It was in 1876 that John Frederick Blake made the first scientific description of the animal, although he did so only very briefly. In 1889, Lydekker considered this species as a potential junior synonym of ''I. trigonodon'', an opinion which was followed by numerous authors until around the beginning of the 20th century. In 1930, Sidney Melmore made the first in-depth description of ''I. crassimanus'' based on the holotype specimen, restoring the distinct status of the species. In his revision published in 1974, McGowan synonymized ''I. crassimanus'' with the proposed taxon '' Stenopterygius acutirostis'', also attributing other specimens discovered in the original locality. In 2003, McGowan and Ryosuke Motani suggested that all specimens historically attributed to ''I. crassimanus'' appeared sufficiently different from ''T. platyodon'' and ''T. trigonodon'' to belong to a distinct species of the genus ''Temnodontosaurus'', being renamed ''T. crassimanus''. However, they note that further research could question its validity. Long remaining an under-analyzed taxon, it was in 2020 that Emily J. Swaby wrote a thesis

A thesis (: theses), or dissertation (abbreviated diss.), is a document submitted in support of candidature for an academic degree or professional qualification presenting the author's research and findings.International Standard ISO 7144: D ...

considerably revising it. Contrary to the suggestion previously made by McGowan and Motani, Swaby maintains the attribution of this species to ''Temnodontosaurus''. The descriptions of this same thesis were finally published the following year in a study co-authored with Daniel R. Lomax.

In 1880, Harry Govier Seeley described the species ''I. zetlandicus'' on the basis of a well-preserved skull loaned by an

In 1880, Harry Govier Seeley described the species ''I. zetlandicus'' on the basis of a well-preserved skull loaned by an Earl

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. In modern Britain, an earl is a member of the Peerages in the United Kingdom, peerage, ranking below a marquess and above a viscount. A feminine form of ''earl'' never developed; instead, ...

of Shetland

Shetland (until 1975 spelled Zetland), also called the Shetland Islands, is an archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands, and Norway, marking the northernmost region of the United Kingdom. The islands lie about to the ...

(hence its name) around an unspecified date to the Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences in Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

. This skull, cataloged as CAMSM J35176, was discovered in the coast

A coast (coastline, shoreline, seashore) is the land next to the sea or the line that forms the boundary between the land and the ocean or a lake. Coasts are influenced by the topography of the surrounding landscape and by aquatic erosion, su ...

s of Whitby, near the locality where ''T. crassimanus'' was already discovered. In 1922, von Huene moved the species within ''Stenopterygius''. In 1974, McGowan considered ''S. zetlandicus'' as a synonym of ''S. acutirostris'', before this species was itself synonymized with ''T. acutirostris'' from 1997. In 2022, Antoine Laboury and colleagues reestablished the validity of the species by redescribing CAMSM J35176, but moved it to the genus ''Temnodontosaurus'', being renamed ''T. zetlandicus''. In their description, they attribute another specimen to the taxon, cataloged as MNHNL TU885, a partial skull which was originally discovered in Schouweiler, southern Luxembourg

Luxembourg, officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, is a landlocked country in Western Europe. It is bordered by Belgium to the west and north, Germany to the east, and France on the south. Its capital and most populous city, Luxembour ...

.

In 1931, von Huene described a new species of the genus ''Leptopterygius'', ''L. nürtingensis'', based on a skull and some postcranial remains of a single specimen discovered in a quarry in the town of Nürtingen (hence its name), Baden-Württemberg, Germany. This specimen, cataloged as SMNS 13488, is mentioned for the first time in a work by Eberhard Fraas published posthumously in 1919, in which the author considers it to be the representative of an undetermined species of ''Ichthyosaurus''. In another work also published posthumously in 1926, Fraas attributed this specimen to a proposed new species which he named ''I. bellicosus''. Fraas was initially expected to carry out the first scientific description of this taxon, but the latter's premature death in 1915 prevented this project from being achieved. Thus, in the absence of a scientific description, the name ''I. bellicosus'' is seen as a ''nomen nudum'', and therefore does not have priority over ''L. nürtingensis''. Although ''L. nürtingensis'' was only officially described in 1931 by von Huene, the taxon was already mentioned a year earlier by the same author in an article concerning the rib

In vertebrate anatomy, ribs () are the long curved bones which form the rib cage, part of the axial skeleton. In most tetrapods, ribs surround the thoracic cavity, enabling the lungs to expand and thus facilitate breathing by expanding the ...

s of the holotype specimen, which have since been noted as lost. In 1939, Oskar Kuhn assimilated an incomplete specimen discovered in Aue-Fallstein, Lower Saxony

Lower Saxony is a States of Germany, German state (') in Northern Germany, northwestern Germany. It is the second-largest state by land area, with , and fourth-largest in population (8 million in 2021) among the 16 ' of the Germany, Federal Re ...

, to this species. However, Kuhn did not present sufficient evidence to confirm his claims, and the specimen has since been viewed as indeterminate. In 1979, McGowan carried out a large revision of the ichthyosaurs known from Germany, in which he classified ''L. nürtingensis'' as a ''nomen dubium

In binomial nomenclature, a ''nomen dubium'' (Latin for "doubtful name", plural ''nomina dubia'') is a scientific name that is of unknown or doubtful application.

Zoology

In case of a ''nomen dubium,'' it may be impossible to determine whether a ...

''. In 1997, Maisch and Axel Hungerbühler formally criticized McGowan's view, given that the holotype specimen is preserved in an excellent state of conservation and is easily diagnosable. He then redescribed this specimen and considered it to be attributable to ''Temnodontosaurus''. In their analysis, the authors change the typography of the species ''nürtingensis'' to ''nuertingensis'', due to rule 32.C of the ICZN

The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) is a widely accepted convention in zoology that rules the formal scientific naming of organisms treated as animals. It is also informally known as the ICZN Code, for its formal author, t ...

requiring it. The species is again considered a ''nomen dubium'' by McGowan and Motani in 2003, but its validity as well as its belonging to this genus is maintained in subsequent studies.

Dubious species

In 1881, Owen attributed a large isolated skull discovered at Lyme Regis, cataloged as NHMUK PV R1157, to the newly erected species of the genus ''Ichthyosaurus'', ''I. breviceps''. In 1922, von Huene moved this species to the genus ''Eurypterygius'', a taxon which is itself recognized as a junior synonym of ''Ichthyosaurus''. Although ''I. breviceps'' is still recognized as belonging to this genus, the large skull historically attributed to the species has large differences with the holotype specimen. Noting this, McGowan redescribed this specimen in more detail and made it the holotype of an entirely new species of ''Temnodontosaurus'', ''T. eurycephalus''. The specific name comes from the Ancient Greek (, "broad"), and (, "head"), all meaning "broad head", in reference to the cranial morphology of the taxon. In 1984, an almost complete skeleton of a large ichthyosaur was discovered in the Lafarge quarries in theFrench commune

A () is a level of administrative division in the French Republic. French are analogous to civil townships and incorporated municipalities in Canada and the United States; ' in Germany; ' in Italy; ' in Spain; or civil parishes in the Uni ...

of Belmont-d'Azergues, located near Lyon

Lyon (Franco-Provençal: ''Liyon'') is a city in France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of the French Alps, southeast of Paris, north of Marseille, southwest of Geneva, Switzerland, north ...

. Although the specimen is mentioned in a detailed biostratigraphic

Biostratigraphy is the branch of stratigraphy which focuses on correlating and assigning relative ages of rock strata by using the fossil assemblages contained within them.Hine, Robert. "Biostratigraphy." ''Oxford Reference: Dictionary of Biology ...

analysis of the Lafarge quarries published in 1991, it was in 2012 when the fossil, uncatalogued but stored in the Saint-Pierre-la-Palud , was officially designated as the holotype of the new species ''T. azerguensis'' by Jeremy E. Martin and his colleagues. The specific name comes from the Azergues

The Azergues () is a river in the department of Rhône, eastern France. It is a right tributary of the Saône, which it joins in Anse. It is long. Its source is in the Beaujolais hills, near Chénelette. The Azergues flows through the following ...

, a river

A river is a natural stream of fresh water that flows on land or inside Subterranean river, caves towards another body of water at a lower elevation, such as an ocean, lake, or another river. A river may run dry before reaching the end of ...

located near the site of the discovery.

In 2014, British paleontologist Darren Naish

Darren William Naish (born 26 September 1975) is a British vertebrate palaeontologist, author and science communicator.

As a researcher, he is best known for his work describing and reevaluating dinosaurs and other Mesozoic reptiles, including ...

expressed doubts in a blog in the journal ''Scientific American

''Scientific American'', informally abbreviated ''SciAm'' or sometimes ''SA'', is an American popular science magazine. Many scientists, including Albert Einstein and Nikola Tesla, have contributed articles to it, with more than 150 Nobel Pri ...

'' about the attribution of these two species to ''Temnodontosaurus'', noting their large anatomical differences highlighting the need for a taxonomic revision of this genus. A similar observation is shared in the study describing ''T. zetlandicus'' in 2022, with the authors mentioning these two species as too phylogenetically unstable to be included in a monophyletic grouping of ''Temnodontosaurus''.

Formerly assigned species

In 1840, Owen named the species ''I. acutirostris'' on the basis of a partial skeleton discovered near Whitby, now numbered NHMUK PV OR 14553. The holotype specimen was for a long time noted as lost, but this was only in 2002 when it was officially found, although some anatomical parts such as the snout are missing. Even before the specimen was found, some studies classified this species within the genus ''Temnodontosaurus'', as Maisch and Hungerbühler did in 1997. However, Maisch reversed his decision in 2010, citing that numerous cranial features prove it is not part of the genus. Therefore, the author withdraws his attribution of this specimen to ''Temnodontosaurus'' and instead suggests that the latter would be the representative of a completely new genus. In 2022, Laboury and colleagues share the same conclusions and considers "''I.''" ''acutirostris'' as a ''species inquirenda

In biological classification, a ''species inquirenda'' is a species of doubtful identity requiring further investigation. The use of the term in English-language biological literature dates back to at least the early nineteenth century.

The ter ...

''.

Yonne

Yonne (, in Burgundian: ''Ghienne'') is a department in the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté region in France. It is named after the river Yonne, which flows through it, in the country's north-central part. One of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté's eight con ...

, France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

. Even before the taxon was described by Gaudry, the specimen, being one of the largest ichthyosaurs known at the time, led to it being presented at the 1889 Paris Exposition, the same exhibition for which the Eiffel Tower

The Eiffel Tower ( ; ) is a wrought-iron lattice tower on the Champ de Mars in Paris, France. It is named after the engineer Gustave Eiffel, whose company designed and built the tower from 1887 to 1889.

Locally nicknamed "''La dame de fe ...

was built. After the end of the exhibition, the specimen was subsequently donated to the National Museum of Natural History

The National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) is a natural history museum administered by the Smithsonian Institution, located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., United States. It has free admission and is open 364 days a year. With 4.4 ...

in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

, joining its collection on November 12, 1889, where it is still exhibited to this day. Gaudry already proposed the name of ''I. burgundiae'' at the French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (, ) is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French Scientific method, scientific research. It was at the forefron ...

in 1891, but it was not until the following year that he published the first formal description of the taxon. In 1996, McGowan attributed a number of specimens discovered in Germany to this species, but moved it there to the genus ''Temnodontosaurus''. In 1998, Maisch compared these specimens to the holotype of ''T. trigonodon'', and suggested synonymizing ''T. burgundiae'' with the latter. Maisch's opinion is followed by McGowan and Motani in 2003, considering ''T. burgundiae'' as a junior synonym of ''T. trigonodon'', despite slight osteological differences. The synonymy is however based only on German specimens, a new examination of the holotype specimen discovered in Sainte-Colombe having never been carried out due to its questionable state of conservation.

Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

''Risor'', meaning "mocker". In his description, he justifies the distinction of this species via the larger orbits

In celestial mechanics, an orbit (also known as orbital revolution) is the curved trajectory of an physical body, object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an satellite, artificia ...

, the smaller maxilla

In vertebrates, the maxilla (: maxillae ) is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The two maxil ...

e and the curved snout

A snout is the protruding portion of an animal's face, consisting of its nose, mouth, and jaw. In many animals, the structure is called a muzzle, Rostrum (anatomy), rostrum, beak or proboscis. The wet furless surface around the nostrils of the n ...

. In 1995, the same author carried out a more in-depth revision of the three specimens attributed to this taxon. He then discovered that the characteristics he had previously judged to be distinctive were in fact stages of growth, the three specimens representing juveniles of ''T. platyodon''.

Early depictions

One of the earliest representations of ''Temnodontosaurus'' in paleoart is a life-size concrete sculpture created by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins between 1852 and 1854, as part of the collection of sculptures of prehistoric animals on display at the

One of the earliest representations of ''Temnodontosaurus'' in paleoart is a life-size concrete sculpture created by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins between 1852 and 1854, as part of the collection of sculptures of prehistoric animals on display at the Crystal Palace Park

Crystal Palace Park is a park in south-east London, Grade II* listed on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens. It was laid out in the 1850s as a pleasure ground, centred around the re-location of The Crystal Palace – the largest glass ...

in London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

. It is one of the three ichthyosaur sculptures exhibited in the park, the other two representing ''Ichthyosaurus'' and '' Leptonectes''. Although the park is known for its obsolete or even false reconstructions of extinct animals, the sculptures depicting ichthyosaurs have the most elements still recognized as valid. These recognized features include smooth, scaleless skin, a fin at the end of the tail, and large eyes. Hawkins also reconstructed the facial features of these three ichthyosaurs based on those of whale

Whales are a widely distributed and diverse group of fully Aquatic animal, aquatic placental mammal, placental marine mammals. As an informal and Colloquialism, colloquial grouping, they correspond to large members of the infraorder Cetacea ...

s and dolphin

A dolphin is an aquatic mammal in the cetacean clade Odontoceti (toothed whale). Dolphins belong to the families Delphinidae (the oceanic dolphins), Platanistidae (the Indian river dolphins), Iniidae (the New World river dolphins), Pontopori ...

s, which is still recognized as reasonable given their strong morphological similarities. Discoveries and reconstructions subsequent to those at the Crystal Palace add to this the presence of a dorsal fin

A dorsal fin is a fin on the back of most marine and freshwater vertebrates. Dorsal fins have evolved independently several times through convergent evolution adapting to marine environments, so the fins are not all homologous. They are found ...

, a caudal fin

Fins are moving appendages protruding from the body of fish that interact with water to generate thrust and help the fish swim. Apart from the tail or caudal fin, fish fins have no direct connection with the back bone and are supported only ...

with two crescent-shaped lobes as well as a reconstruction of the skin on the basis of most well-preserved fossils.

Many elements of these reconstructions still remain obsolete, such as the eyes and the flippers which are reconstructed by the shape of their bones, namely the sclerotic ring

The scleral ring or sclerotic ring is a hardened ring of plates, often derived from bone, that is found in the eyes of many animals in several groups of vertebrates. Some species of mammals, amphibians, and crocodilians lack scleral rings. The rin ...

s and the phalanges

The phalanges (: phalanx ) are digit (anatomy), digital bones in the hands and foot, feet of most vertebrates. In primates, the Thumb, thumbs and Hallux, big toes have two phalanges while the other Digit (anatomy), digits have three phalanges. ...

. Although Owen suggested the still viable hypothesis that the scleral rings served to protect the eye, it is highly unlikely that the eyes of ichthyosaurs would have looked as shown in the carvings, given that the scleral rings are located under the eyelid

An eyelid ( ) is a thin fold of skin that covers and protects an eye. The levator palpebrae superioris muscle retracts the eyelid, exposing the cornea to the outside, giving vision. This can be either voluntarily or involuntarily. "Palpebral ...

s. The flippers were faithfully reconstructed by Hawkins based on Owen's misinterpretation of the phalanges as scales. The park's ichthyosaurs are depicted as crawling in shallow water, reflecting the ancient hypothesis that they came to the shores to sleep or to breed. Additionally, their tails are shown to be eel

Eels are ray-finned fish belonging to the order Anguilliformes (), which consists of eight suborders, 20 families, 164 genera, and about 1000 species. Eels undergo considerable development from the early larval stage to the eventual adult stage ...

-like and having a great degree of flexibility. However, the three ichthyosaurs actually had a fairly variable degree of flexibility. Two of the three taxa shown, i. e. ''Temnodontosaurus'' and ''Leptonectes'', were found to have much more flexible tails than that of ''Ichthyosaurus'', the latter having a tuna

A tuna (: tunas or tuna) is a saltwater fish that belongs to the tribe Thunnini, a subgrouping of the Scombridae ( mackerel) family. The Thunnini comprise 15 species across five genera, the sizes of which vary greatly, ranging from the bul ...

-like morphology. This way of reconstructing the tail of ichthyosaurs as similar to those of eels is not an error specific to Hawkins, being the norm in reconstructions dating from the 19th century.

Description

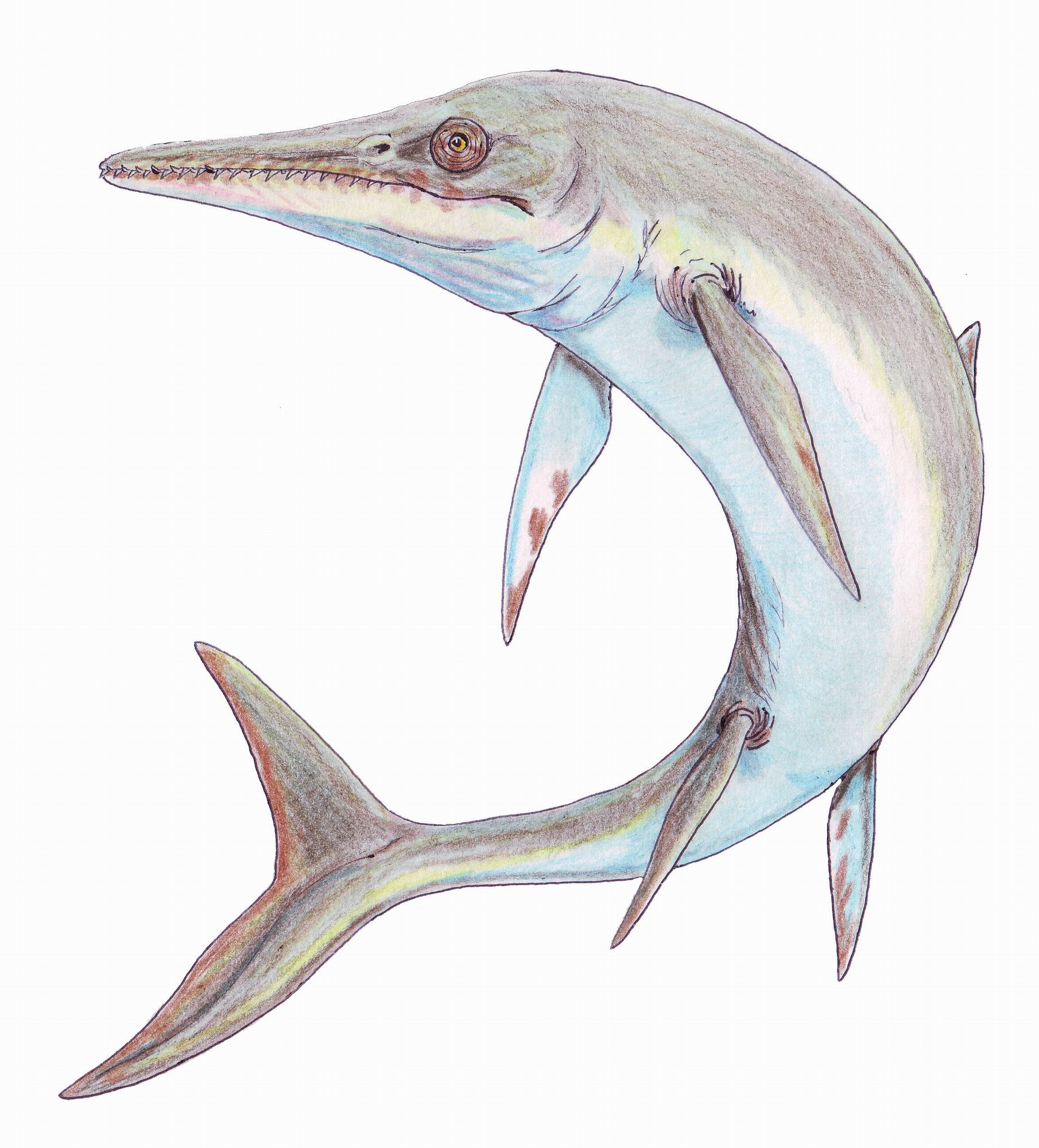

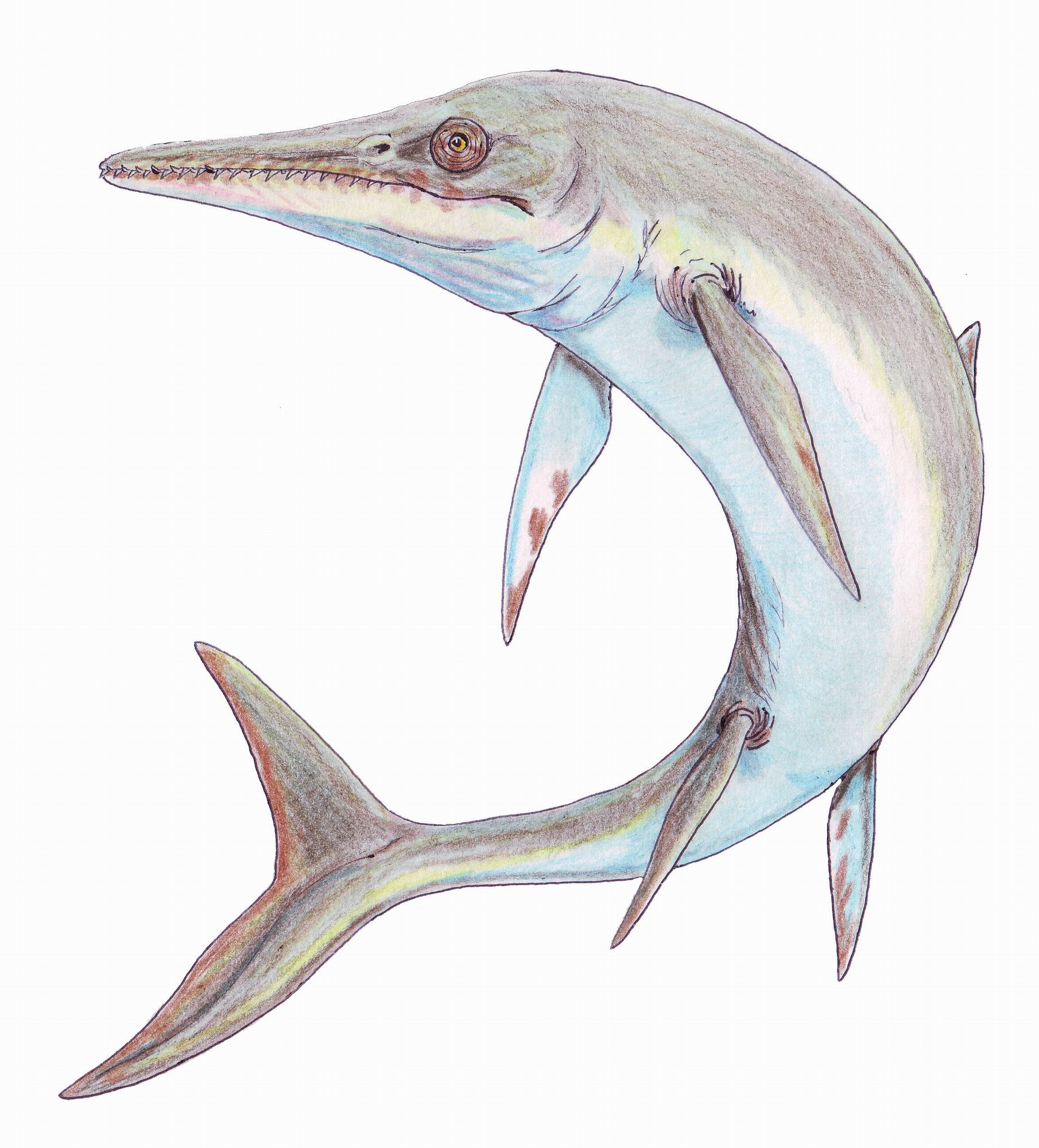

''Temnodontosaurus'', like other ichthyosaurs, had a long, thinsnout

A snout is the protruding portion of an animal's face, consisting of its nose, mouth, and jaw. In many animals, the structure is called a muzzle, Rostrum (anatomy), rostrum, beak or proboscis. The wet furless surface around the nostrils of the n ...

, large eye sockets, and a tail fluke

A fin is a thin component or appendage attached to a larger body or structure. Fins typically function as foil (fluid mechanics), foils that produce lift (force), lift or thrust, or provide the ability to steer or stabilize motion while travelin ...

that was supported by vertebrae in the lower half. Ichthyosaurs were superficially similar to dolphin

A dolphin is an aquatic mammal in the cetacean clade Odontoceti (toothed whale). Dolphins belong to the families Delphinidae (the oceanic dolphins), Platanistidae (the Indian river dolphins), Iniidae (the New World river dolphins), Pontopori ...

s and had flippers rather than legs, and most (except for early species) had dorsal fin

A dorsal fin is a fin on the back of most marine and freshwater vertebrates. Dorsal fins have evolved independently several times through convergent evolution adapting to marine environments, so the fins are not all homologous. They are found ...

s. Although the colour of ''Temnodontosaurus'' is unknown, at least some ichthyosaurs may have been uniformly dark-coloured in life, which is evidenced by the discovery of high concentrations of eumelanin

Melanin (; ) is a family of biomolecules organized as oligomers or polymers, which among other functions provide the pigments of many organisms. Melanin pigments are produced in a specialized group of cells known as melanocytes.

There are ...

pigments in the preserved skin of an early ichthyosaur fossil.

Size

''Temnodontosaurus'' is one of the largest ichthyosaurs identified to date, although the species which belong to it are not as imposing as

''Temnodontosaurus'' is one of the largest ichthyosaurs identified to date, although the species which belong to it are not as imposing as Triassic

The Triassic ( ; sometimes symbolized 🝈) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.5 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.4 Mya. The Triassic is t ...

forms like '' Shonisaurus'', '' Himalayasaurus'', '' Cymbospondylus'' or ''Ichthyotitan

''Ichthyotitan'' ( ) is an extinct genus of giant ichthyosaur from the Late Triassic (Rhaetian), known from the Westbury Formation, Westbury Mudstone Formation in Somerset, England. It is believed to be a shastasaurid, extending the family's ra ...

''. It nevertheless represents the largest known ichthyosaur of the parvipelvia

Parvipelvia (Latin for "little pelvis" - ''parvus'' meaning "little" and ''pelvis'' meaning "pelvis") is an extinct clade of euichthyosaur ichthyosaurs that existed from the Late Triassic to the early Late Cretaceous (middle Norian to Cenomanian ...

n group. Based on different specimens, the species ''T. platyodon'', ''T. trigonodon'' and ''T. crassimanus'' have a body size which is estimated to be around long. The ‘Rutland Sea Dragon’, a possible specimen of ''T. trigonodon'' discovered in January 2021 in the Rutland Water

Rutland Water is a reservoir in Rutland, England, east of Rutland's county town, Oakham. It is filled by pumping from the River Nene and River Welland, and provides water to the East Midlands. By surface area it is the largest reservoir in E ...

, near Oakham

Oakham is a market town and civil parish in Rutland (of which it is the county town) in the East Midlands of England. The town is located east of Leicester, southeast of Nottingham and northwest of Peterborough. It had a population of 12,14 ...

, is estimated to be slightly over long. Skull size varies between these three species. The largest known skulls of ''T. trigonodon'' and ''T. platyodon'' are to long, respectively. Although incomplete, the holotype specimen of ''T. crassimanus'' would have had a skull estimated to be around long. No body length estimates for ''T. zetlandicus'' and ''T. nuertingensis'' have currently been given. However, the measurement of their skull, reaching respectively in length, suggests that they are smaller representatives when compared to the three species previously mentioned.

Individual bones suggest that ''Temnodontosaurus'' may have grown to a larger size. In his extensive revision published in 1922, von Huene described a series of very imposing vertebrae from the collections of the Banz Abbey

Banz Abbey (), now known as Banz Castle (), is a former Benedictine monastery, since 1978 a part of the town of Bad Staffelstein north of Bamberg, Bavaria, southern Germany.

History

The abbey was founded in about 1070 by Countess Alberada o ...

Museum, Germany, the largest of them measuring high. In 1996, McGowan nominally assigned the specimen to ''Temnodontosaurus'', although without specific assignment. Based on SMNS 50000, a nearly complete skeleton of ''T. trigonodon'', the author estimated the size of Banz's specimen at long, as Huene initially suggested. However, the estimate he proposes turns out to be exaggerated, given that the source of its size is incorrect based on the actual measurements of the specimen SMNS 50000, which is of a shorter length.

Morphology

The forefins and hindfins of ''Temnodontosaurus'' were of roughly the same length and were rather narrow and elongated. This characteristic is unlike other post-Triassic ichthyosaurs such as the

The forefins and hindfins of ''Temnodontosaurus'' were of roughly the same length and were rather narrow and elongated. This characteristic is unlike other post-Triassic ichthyosaurs such as the thunnosauria

Thunnosauria (Ancient Greek, Greek for "tuna lizard" – ''thunnos'' meaning "tuna" and ''sauros'' meaning "lizard") is an extinct clade of parvipelvian ichthyosaurs from the Early Jurassic to the early Late Cretaceous (Hettangian–Cenomanian) o ...

ns, which had forefins at least twice the length of their hindfins. It was different from other post-Triassic

The Triassic ( ; sometimes symbolized 🝈) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.5 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.4 Mya. The Triassic is t ...

ichthyosaurs like ''Ichthyosaurus'', possessing an unreduced, tripartite pelvic girdle and having only three primary digits with one postaxial accessory digit. Like other ichthyosaurs, the fins exhibited strong hyperphalangy, but the fins were not involved in body propulsion; only the tail was used as the main propulsive force for movement, although it had a weak tail bend at an angle of less than 35°. Its caudal fin has variously been described as either lunate or semi-lunate; it was made of two lobes, in which the lower lobe was skeletally supported whereas the upper lobe was unsupported. The proximal elements of the fin formed a mosaic pattern, while the more distal elements were relatively round. It also had a triangular dorsal fin and had two notches on the fin's anterior margin; the paired fins were used to steer and stabilize the animal while swimming instead of paddling or propulsion devices. It had roughly less than 90 vertebrae, and the axis and atlas of the vertebrae were fused together, serving as stabilization during swimming. ''T. trigonodon'' possessed unicipital ribs near the sacral region and the bicipital ribs more anteriorly, which helped to increase flexibility while swimming.

Like other ichthyosaurs, ''Temnodontosaurus'' likely had high visual capacity and used vision as its primary sense while hunting. ''Temnodontosaurus'' had the largest eyes of any ichthyosaur and of any animal measured. The largest eyes measured belonged to the species ''T. platyodon''. Despite the enormous size of its eyes, ''Temnodontosaurus'' had blind spots directly above its head due to the angle at which its eyes were pointed. The eyes of ''Temnodontosaurus'' had sclerotic ring

The scleral ring or sclerotic ring is a hardened ring of plates, often derived from bone, that is found in the eyes of many animals in several groups of vertebrates. Some species of mammals, amphibians, and crocodilians lack scleral rings. The rin ...

s, hypothesized to have provided the eyes with rigidity. The sclerotic rings of ''T. platyodon'' were at least 25 cm in diameter.

The head of ''Temnodontosaurus'' had a long robust snout with an antorbital constriction. It also had an elongated maxilla, a long cheek region, and a long postorbital segment. The carotid foramen in the basisphenoid in the skull was paired and was separated by the parasphenoid. The parasphenoid had a processus cultriformis. The skull of ''T. platyodon'' measured about long, while ''T. eurycephalus'' had a shorter rostrum and a deeper skull compared to other species, perhaps serving to help crush prey. ''T. platyodon'' and ''T. trigadon'' had a very long snout that was slightly curved on its dorsal side and ventrally curved, respectively. It also had many pointed conical teeth that were set in continuous grooves, rather than having individual sockets. This form of tooth implantation is known as aulacodonty. Its teeth typically had two or three carinae; notably, ''T. eurycephalus'' possessed bulbous roots, while ''T. nuertingensis'' had no canine or bulbous roots.

Classification

The majority of the currently recognized species of ''Temnodontosaurus'' were originally described as species of ''Ichthyosaurus'', before the type species ''T. platyodon'' was moved to a separate genus in 1889 by Lydekker. In 1974, McGowan established the

The majority of the currently recognized species of ''Temnodontosaurus'' were originally described as species of ''Ichthyosaurus'', before the type species ''T. platyodon'' was moved to a separate genus in 1889 by Lydekker. In 1974, McGowan established the family

Family (from ) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictabili ...

Temnodontosauridae, to which it is still the only genus recognized. ''Temnodontosaurus'' is one of the most basal post-Triassic

The Triassic ( ; sometimes symbolized 🝈) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.5 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.4 Mya. The Triassic is t ...

ichthyosaurs. In the first major phylogenetic revision of ichthyosaurs, carried out in 1999 by Motani, ''Temnodontosaurus'' is placed in the Parvipelvia

Parvipelvia (Latin for "little pelvis" - ''parvus'' meaning "little" and ''pelvis'' meaning "pelvis") is an extinct clade of euichthyosaur ichthyosaurs that existed from the Late Triassic to the early Late Cretaceous (middle Norian to Cenomanian ...

clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

. It is this specific group of ichthyosaurs that includes all of the "fish-shaped" representatives, with the more basal ichthyosaurs having more elongated body plans. In 2000, erected a new clade within this subgroup, which he named Neoichthyosauria. This clade notably brings together ''Temnodontosaurus'', ''Suevoleviathan

''Suevoleviathan'' is an extinct genus of primitive ichthyosaur found in the Early Jurassic (Toarcian) of Holzmaden, Germany.

Taxonomy

The genus was named in 1998 by Michael Maisch for ''Leptopterygius disinteger'' and ''Ichthyosaurus integer' ...

'', Leptonectidae

Leptonectidae is a family of ichthyosaurs

Ichthyosauria is an taxonomy (biology), order of large extinction, extinct marine reptiles sometimes referred to as "ichthyosaurs", although the term is also used for wider clades in which the order res ...

and Thunnosauria

Thunnosauria (Ancient Greek, Greek for "tuna lizard" – ''thunnos'' meaning "tuna" and ''sauros'' meaning "lizard") is an extinct clade of parvipelvian ichthyosaurs from the Early Jurassic to the early Late Cretaceous (Hettangian–Cenomanian) o ...

, the latter including all of the ichthyosaurs that lived until the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 143.1 to 66 mya (unit), million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era (geology), Era, as well as the longest. At around 77.1 million years, it is the ...

. For reasons of classification convenience, McGowan and Motani established the superfamily Temnodontosauroidea in 2003. In their phylogenetic revision published in 2016, Ji and colleagues classify Leptonectidae within this proposed superfamily, recovering ''Temnodontosaurus'' as the latter's sister taxon

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Definition

The expression is most easily illustrated by a cladogram:

Taxon A and ...

. However, other classifications clearly do not follow this model, preferring to stick to the definition of Neoichthyosauria as previously mentioned.

For several decades, ''Temnodontosaurus'' was a taxon whose monophyly

In biological cladistics for the classification of organisms, monophyly is the condition of a taxonomic grouping being a clade – that is, a grouping of organisms which meets these criteria:

# the grouping contains its own most recent comm ...

was rarely questioned. The current diagnostic of the genus was first established in the revision made by McGowan in 1974 based on some cranial and postcranial characteristics. However, as the cranial features of aquatic tetrapod

A tetrapod (; from Ancient Greek :wiktionary:τετρα-#Ancient Greek, τετρα- ''(tetra-)'' 'four' and :wiktionary:πούς#Ancient Greek, πούς ''(poús)'' 'foot') is any four-Limb (anatomy), limbed vertebrate animal of the clade Tetr ...

s are strongly influenced by convergent evolution

Convergent evolution is the independent evolution of similar features in species of different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last comm ...

, this does not seem ideal for establishing a stable taxonomy. Thus, since the late 1990s, many authors, including McGowan himself, have advocated that ''Temnodontosaurus'' needs to be revised. Additionally, numerous recent phylogenetic analyzes showing that the genus as currently defined is polyphyletic

A polyphyletic group is an assemblage that includes organisms with mixed evolutionary origin but does not include their most recent common ancestor. The term is often applied to groups that share similar features known as Homoplasy, homoplasies ...

, with some historically assigned species being unrelated each other. Thus, pending future studies, ''Temnodontosaurus'' is currently seen as a wastebasket taxon

Wastebasket taxon (also called a wastebin taxon, dustbin taxon or catch-all taxon) is a term used by some taxonomists to refer to a taxon that has the purpose of classifying organisms that do not fit anywhere else. They are typically defined by e ...

including some large, more or less related neoichthyosaurians dating from the Lower Jurassic. In the last major study investigating the taxonomy of this genus, having been carried out by Laboury ''et al.'' (2022), only four species appear to form a monophyletic grouping, namely ''T. platyodon'', ''T. trigonodon'', ''T. zetlandicus'' and ''T. nuertingensis''.

Below, a simplified cladogram

A cladogram (from Greek language, Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an Phylogenetic tree, evolutionary tree because it does not s ...

based on a Bayesian analysis

Thomas Bayes ( ; c. 1701 – 1761) was an English statistician, philosopher, and Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elde ...

conducted by Laboury ''et al.'' (2022):

Paleobiology

With their dolphin-like bodies, ichthyosaurs were better adapted to their aquatic environment than any other group of marine reptiles. They wereviviparous

In animals, viviparity is development of the embryo inside the body of the mother, with the maternal circulation providing for the metabolic needs of the embryo's development, until the mother gives birth to a fully or partially developed juve ...

that gave birth to live young and were likely incapable of leaving the water. As homeotherms ("warm-blooded") with high metabolic rates, ichthyosaurs would have been active swimmers. Jurassic and Cretaceous ichthyosaurs, including ''Temnodontosaurus'', had evolved a thunniform method of swimming rather than the anguilliform

Fish locomotion is the various types of animal locomotion used by fish, principally by aquatic locomotion, swimming. This is achieved in different groups of fish by a variety of mechanisms of propulsion, most often by wave-like lateral flexions ...

(undulating or eel-like) methods of earlier species. ''Temnodontosaurus'', particularly the species ''T. trigonodon'', is quite flexible in morphology for a parvipelvian, using its imposing flippers to maneuver under water.

Ichthyosaurs have the largest eyes of any known vertebrate

Vertebrates () are animals with a vertebral column (backbone or spine), and a cranium, or skull. The vertebral column surrounds and protects the spinal cord, while the cranium protects the brain.

The vertebrates make up the subphylum Vertebra ...

s, with ''Temnodontosaurus'' having the largest identified. The sclerotic ring

The scleral ring or sclerotic ring is a hardened ring of plates, often derived from bone, that is found in the eyes of many animals in several groups of vertebrates. Some species of mammals, amphibians, and crocodilians lack scleral rings. The rin ...

s in their eyes would have served to resist aquatic pressures. The eyes of ichthyosaurs like those of ''Temnodontosaurus'' would have a great visual capacity via the high number of photoreceptor cell

A photoreceptor cell is a specialized type of neuroepithelial cell found in the retina that is capable of visual phototransduction. The great biological importance of photoreceptors is that they convert light (visible electromagnetic radiation ...

s. In addition to good eyesight, the enlarged olfactory region of the brain indicates that ichthyosaurs had a sensitive sense of smell.

Diet and feeding

Paleontologists generally agree that ''Temnodontosaurus'' was likely an active predator of a variety of other marine animals. Fauna hunted by the genus includebony fish

Osteichthyes ( ; ), also known as osteichthyans or commonly referred to as the bony fish, is a Biodiversity, diverse clade of vertebrate animals that have endoskeletons primarily composed of bone tissue. They can be contrasted with the Chondricht ...

, cephalopod

A cephalopod is any member of the molluscan Taxonomic rank, class Cephalopoda (Greek language, Greek plural , ; "head-feet") such as a squid, octopus, cuttlefish, or nautilus. These exclusively marine animals are characterized by bilateral symm ...

s, and aquatic reptiles, including even other ichthyosaurs. The skeletal anatomy of ''Temnodontosaurus'' suggests that it may have been an ambush predator

Ambush predators or sit-and-wait predators are carnivorous animals that capture their prey via stealth, luring or by (typically instinctive) strategies utilizing an element of surprise. Unlike pursuit predators, who chase to capture prey u ...

. A particular skeleton of ''T. trigonodon'' (SMNS 50000) preserves in its stomach the remains of three juvenile '' Stenopterygius'' accompanied by a large number of cephalopod hooks. This proves that the animal was indeed an apex predator

An apex predator, also known as a top predator or superpredator, is a predator at the top of a food chain, without natural predators of its own.

Apex predators are usually defined in terms of trophic dynamics, meaning that they occupy the hig ...

, but its diet consisted mainly of mollusc

Mollusca is a phylum of protostome, protostomic invertebrate animals, whose members are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 76,000 extant taxon, extant species of molluscs are recognized, making it the second-largest animal phylum ...

s, with the large number of undigested hooks being compressed into a large gastric mass. Bromalites attributed to ''T. trigonodon'' suggest that it specifically targeted neonatal and juvenile ''Stenopterygius'' when hunting.

Paleopathology

There is fossil evidence that ''Temnodontosaurus'' engaged in aggressive combat, possibly with other members of its own genus. Several specimens exhibit healed traumatic injuries that were likely inflicted by other large marine reptiles. A particular specimen of ''T. trigonodon'' (SMNS 15950) exhibits ten roughly circular areas separated by only a few centimeters, suggesting that it was bitten by a large marine reptile with a long rostrum. The size and location of these injuries suggest that it was either attacked by another ''T. trigonodon'' or by a thalattosuchian similar to the contemporary '' Steneosaurus''. Two other specimens, including the holotype of ''T. nuertingensis'', exhibit deep wounds in the most posterior part of the mandible. Both specimens also exhibit healed wounds ventral to the

There is fossil evidence that ''Temnodontosaurus'' engaged in aggressive combat, possibly with other members of its own genus. Several specimens exhibit healed traumatic injuries that were likely inflicted by other large marine reptiles. A particular specimen of ''T. trigonodon'' (SMNS 15950) exhibits ten roughly circular areas separated by only a few centimeters, suggesting that it was bitten by a large marine reptile with a long rostrum. The size and location of these injuries suggest that it was either attacked by another ''T. trigonodon'' or by a thalattosuchian similar to the contemporary '' Steneosaurus''. Two other specimens, including the holotype of ''T. nuertingensis'', exhibit deep wounds in the most posterior part of the mandible. Both specimens also exhibit healed wounds ventral to the splenial

The splenial is a small bone in the lower jaw of reptile

Reptiles, as commonly defined, are a group of tetrapods with an ectothermic metabolism and Amniotic egg, amniotic development. Living traditional reptiles comprise four Order (biology ...

bone, in the mandibular symphysis. These injuries, combined with the size of the teeth of the animals potentially responsible for them, suggest that the tissues of the mandible of ''Temnodontosaurus'' would have been very thin.

Paleoecology

Western Europe

In Europe, ''Temnodontosaurus'' is mainly known from fossils dating from the various stages of the Lower Jurassic of England, Germany, France and Luxembourg, with nevertheless some more or less fragmentary specimens having been reported inArlon

Arlon (; ; ; ) is a City status in Belgium, city and Municipalities in Belgium, municipality of Wallonia, and the capital of the Luxembourg (Belgium), province of Luxembourg in the Ardennes, Belgium. With a population of just over 28,000, it ...

, Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

, in Italy, and in Basel