Symphony Of The New World on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Symphony of the New World was a

The program notes stated:

The program notes stated:

symphony orchestra

An orchestra (; ) is a large instrumental ensemble typical of classical music, which combines instruments from different families.

There are typically four main sections of instruments:

* bowed string instruments, such as the violin, viola, ce ...

based in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

. It was the first racially integrated orchestra in the United States. The Symphony gave its debut concert on 6 May 1965 at Carnegie Hall

Carnegie Hall ( ) is a concert venue in Midtown Manhattan in New York City. It is at 881 Seventh Avenue (Manhattan), Seventh Avenue, occupying the east side of Seventh Avenue between West 56th Street (Manhattan), 56th and 57th Street (Manhatta ...

, conducted by Benjamin Steinberg, who said of the orchestra: "We have a lot of talent in this city, and we have to create the opportunities to present it to the public".

The symphony's musicians were graduates of music schools such as Juilliard

The Juilliard School ( ) is a private performing arts conservatory in New York City. Established in 1905, the school trains about 850 undergraduate and graduate students in dance, drama, and music. It is widely regarded as one of the most elit ...

, Eastman School of Music

The Eastman School of Music is the music school of the University of Rochester, a private research university in Rochester, New York. It was established in 1921 by industrialist and philanthropist George Eastman.

It offers Bachelor of Music (B.M ...

, the Manhattan School of Music

The Manhattan School of Music (MSM) is a private music conservatory in New York City. The school offers bachelor's, master's, and doctoral degrees in the areas of classical and jazz performance and composition, as well as a bachelor's in mu ...

, and the New England Conservatory

The New England Conservatory of Music (NEC) is a private music school in Boston, Massachusetts. It is the oldest independent music conservatory in the United States and among the most prestigious in the world. The conservatory is located on Hu ...

. Its performances were broadcast on the Voice of America

Voice of America (VOA or VoA) is the state-owned news network and international radio broadcaster of the United States of America. It is the largest and oldest U.S.-funded international broadcaster. VOA produces digital, TV, and radio content ...

and Armed Forces Radio

The American Forces Network (AFN) is a government television and radio broadcast service the U.S. military provides to those stationed or assigned overseas. Headquartered at Fort George G. Meade, Maryland, AFN's broadcast operations, which i ...

to audiences worldwide. ''Ebony

Ebony is a dense black/brown hardwood, coming from several species in the genus ''Diospyros'', which also contains the persimmons. Unlike most woods, ebony is dense enough to sink in water. It is finely textured and has a mirror finish when pol ...

'' magazine pronounced it, "for both artistic and sociological reasons, a major development in the musical history of the United States".

Steinberg continued as music director and conductor until 12 December 1971, when a dispute between him and some of the orchestra's members resulted in his resignation backstage shortly before the start in order for the concert to continue under his baton. Financial difficulties, caused by the general economic situation and by a delay in receiving $100,000 of scheduled grants led to the rest of the 1971–72 concert season being cancelled. The Symphony gave its last concert on Sunday, 9 April 1978.

Founding

In 1940, Steinberg had begun to work with conductorsDean Dixon

Charles Dean Dixon (January 10, 1915November 3, 1976) was an American conductor.

Career

Dixon was born in the upper-Manhattan neighborhood of Harlem in New York City to parents who had earlier migrated from the Caribbean. He studied conducting ...

and Everett Lee to establish the first fully integrated professional symphony orchestra in the U.S. The dream never materialized because of insufficient funds.

When the Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and United States labor law, labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on Race (human categorization), race, Person of color, color, religion, sex, and nationa ...

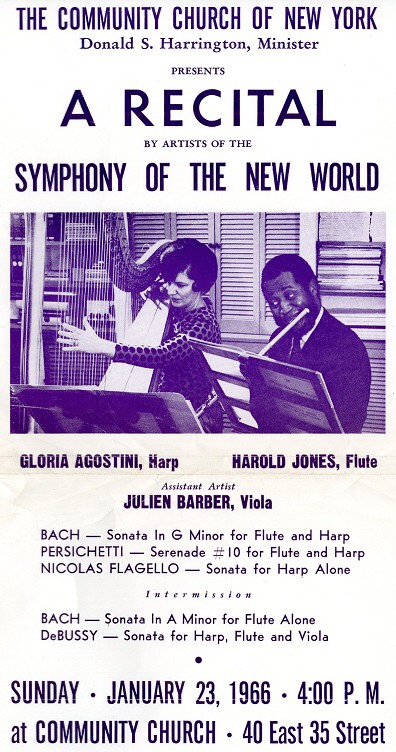

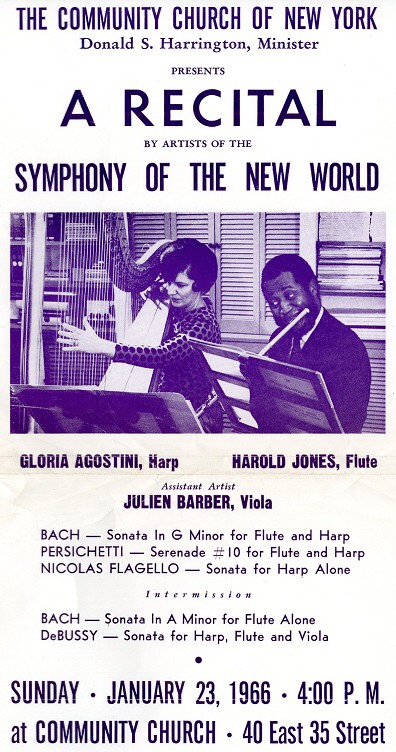

was passed on July 2, flutist Harold Jones remembered: "There was a nucleus of people: Elayne Jones, Harry Smyles, Joe Wilder

Joseph Benjamin Wilder (February 22, 1922 – May 9, 2014) was an American jazz trumpeter, bandleader, and composer.

Wilder was awarded the Temple University Jazz Master's Hall of Fame Award in 2006. The National Endowment for the Arts honored h ...

, Wilmer Wise, Kermit Moore

Kermit Moore (March 11, 1929 – November 11, 2013) was an American conductor, cellist, and composer.

Early life and education

Of African American heritage, Moore was born in Akron, Ohio.

While still in high school, Moore studied at the Cl ...

, Lucille Dixon. We all got together and had these meetings. 'Are we interested?' Everyone jumped to the idea. 'Yes. Let's do this. We're going to do it -- have an integrated orchestra.' The standards of the musicians were very high. We had to deal with personnel. Designating the spots to play was a big-time meeting. Benny organized who was going to be first chair, who was going to be second. Then he asked, 'How many concerts would you like to do?' We discussed it, and he took it to heart. Benny went out and got the money. He asked Zero Mostel, who was doing ''A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum'' on Broadway at the time."

The series of meetings produced the mission statement for the Symphony of the New World, an orchestral expression of the Civil Rights Movement. The name was chosen to reflect the conviction that segregated ensembles were "not of today's world". The mission statement was written by Benjamin Steinberg as Music Director and 11 founders: Alfred Brown, Selwart R. Clarke, Richard Davis, Elayne Jones, Harold M. Jones, Frederick L. King, Kermit D. Moore, Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson

Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson (June 14, 1932, Manhattan, New York City or possibly (unconfirmed) Winston-Salem, North Carolina – March 9, 2004, Chicago) was an American composer whose interests spanned the worlds of jazz, dance, pop, film, ...

, Ross C. Shub, Harry M. Smyles, and Joseph B. Wilder. The goals of The Symphony of the New World were:

# To create job opportunities for the many talented non-white classical instrumentalists who have so far not been accepted in this nation's symphony orchestras.

# To present qualified conductors and, as a basic responsibility, qualified non-white conductors under professional standards.

# To give concerts of the highest artistic and professional standards in communities of low-income families, such as Bedford-Stuyvesant and Harlem areas of New York City. However, the orchestra will periodically appear in Carnegie Hall and Lincoln Center, and in many of the city's schools and colleges.

# To so establish the Symphony of the New World as to make it our nation's cultural beacon in the eyes of the peoples of Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

The orchestra debuted with 36 black and 52 white musicians. Beyond the mission statement, the Symphony wanted to integrate the symphonic stage with female musicians, as well; in 1975 the then director said it was 40% black, with most of those being black women. Among the orchestra’s original sponsors were Samuel Barber

Samuel Osmond Barber II (March 9, 1910 – January 23, 1981) was an American composer, pianist, conductor, baritone, and music educator, and one of the most celebrated composers of the 20th century. The music critic Donal Henahan said, "Proba ...

, Leonard Bernstein

Leonard Bernstein ( ; August 25, 1918 – October 14, 1990) was an American conductor, composer, pianist, music educator, author, and humanitarian. Considered to be one of the most important conductors of his time, he was the first America ...

, Aaron Copland

Aaron Copland (, ; November 14, 1900December 2, 1990) was an American composer, composition teacher, writer, and later a conductor of his own and other American music. Copland was referred to by his peers and critics as "the Dean of American Com ...

, Paul Creston

Paul Creston (born Giuseppe Guttoveggio; October 10, 1906 – August 24, 1985) was an Italian American composer of classical music.

Biography

Born in New York City to Sicilian immigrants, Creston was self-taught as a composer. His work ten ...

, Ruby Dee, Langston Hughes

James Mercer Langston Hughes (February 1, 1901 – May 22, 1967) was an American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist from Joplin, Missouri. One of the earliest innovators of the literary art form called jazz poetry, Hug ...

, Hershy Kay

Hershy Kay (November 17, 1919 – December 2, 1981) was an American composer, arranger, and orchestrator. He is most noteworthy for the orchestrations of several Broadway shows, and for the ballets he arranged for George Balanchine's New York City ...

, Gian Carlo Menotti

Gian Carlo Menotti (, ; July 7, 1911 – February 1, 2007) was an Italian composer, librettist, director, and playwright who is primarily known for his output of 25 operas. Although he often referred to himself as an American composer, he kept h ...

, Zero Mostel, Ruggiero Ricci

Ruggiero Ricci (24 July 1918 – 5 August 2012) was an American violinist known for performances and recordings of the works of Niccolò Paganini, Paganini.

Biography

He was born in San Bruno, California, the son of Italian immigrants who first ...

, and William Warfield

William Caesar Warfield (January 22, 1920 – August 25, 2002) was an American concert bass-baritone singer and actor, known for his appearances in stage productions, Hollywood films, and television programs. A prominent African American artist ...

.

A gift of $1000 from the Equitable Life Assurance Society, a grant from the fund of Martha Baird Rockefeller

Martha Baird Rockefeller (March 15, 1895 – January 24, 1971) was an American pianist, philanthropist and longtime advocate for the arts.�Martha Baird Rockefeller, 1895—1971 in “The Rockefellers.” Sleepy Hollow, New York: The Rockefelle ...

, and many small donations from Black supporters provided the initial backing for the Symphony of the New World. Zero Mostel also contributed.

Performances

On 6 May 1965, two months after the "Bloody Sunday" civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery and exactly three months before theVoting Rights Act of 1965

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of federal legislation in the United States that prohibits racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson during the height of the civil rights movement ...

took effect, the Symphony of the New World performed its debut concert at Carnegie Hall. Soprano Evelyn Mandac

Evelyn Mandac (born August 16, 1945 in Malaybalay) is a soprano opera singer, orchestra soloist, recitalist and voice teacher from the Philippines. She is based in New York City. She's also listed in "Who's Who in Music and Musicians."

A native ...

sang Francesco Cilea

Francesco Cilea (; 23 July 1866 – 20 November 1950) was an Italian composer. Today he is particularly known for his operas ''L'arlesiana'' and ''Adriana Lecouvreur''.

Biography

Born in Palmi near Reggio di Calabria, Cilea gave early indicatio ...

's aria "Iu son l'umile ancella" from his opera, ''Adriana Lecouvreur

''Adriana Lecouvreur'' () is an opera in four acts by Francesco Cilea to an Italian libretto by Arturo Colautti, based on the 1849 play ''Adrienne Lecouvreur'' by Eugène Scribe and Ernest Legouvé. It was first performed on 6 November 1902 at t ...

'' and "Depuis le jour" from ''Louise

Louise or Luise may refer to:

* Louise (given name)

Arts Songs

* "Louise" (Bonnie Tyler song), 2005

* "Louise" (The Human League song), 1984

* "Louise" (Jett Rebel song), 2013

* "Louise" (Maurice Chevalier song), 1929

*"Louise", by Clan of ...

'' by Gustave Charpentier

Gustave Charpentier (; 25 June 1860 – 18 February 1956) was a French composer, best known for his opera '' Louise''.Langham Smith R., "Gustave Charpentier", ''The New Grove Dictionary of Opera.'' Macmillan, London and New York, 1997.

Life and c ...

. Allan Booth was the piano soloist, and Joe Wilder played the trumpet solo for Stravinsky

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (6 April 1971) was a Russian composer, pianist and conductor, later of French (from 1934) and American (from 1945) citizenship. He is widely considered one of the most important and influential 20th-century clas ...

's ''Petrouchka

''Petrushka'' (french: link=no, Pétrouchka; russian: link=no, Петрушка) is a ballet and orchestral concert work by Russian composer Igor Stravinsky. It was written for the 1911 Paris season of Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes company; ...

''.

Trumpeter Wilmer Wise recalled: "Some people were crying because it was something we had dreamt about and it had finally come to fruition. I never felt in my life the way I did when I sat on the stage with Benjamin Steinberg in a fully integrated orchestra – because, usually, I was the one integrating it."

The program notes stated:

The program notes stated:

At this period in our history, when the problem of racial integration has become crucial to our nation's internal well-being as well as to its position in the world, the debut concert tonight of the Symphony of the New World is a historic event in the music life of our time. Under the direction of the noted conductor and music director Benjamin Steinberg, the Symphony consists of 36 Negro and 52 white musicians. Never before in the musical history of the nation has such a completely integrated symphonic ensemble been created. Following its Carnegie Hall debut concert, the Symphony of the New World will repeat its program in Harlem on Sunday afternoon, May 9, at the High School of Music and Art, 135th Street and Convent Avenue. This concert will be the first in the Symphony's long-range plan of performing in communities of low-income families and in reaching a public outside the orbit of the traditional concert world. The idea of the symphony has long been a hope of conductor Steinberg, who has over the past 25 years worked closely with the American Negro conductors, Dean Dixon and Everett Lee, as well as with innumerable nonwhite instrumentalists. In May 1964, Mr. Steinberg and a group of 13 prominent musicians organized a founding committee to create a symphony in which the principle of racial integration would find complete expression. It has taken almost one year for this artistic project to reach fruition. From its inception, the symphony has maintained a strict policy of accepting only thoroughly trained, top-flight performers. In creating job opportunities for the many talented nonwhite instrumentalists who hitherto have not been widely accepted in this nation's symphony orchestras, the Symphony of the New World aims to serve as an example of the principle of racial-equality-in-action to musical groups throughout the country. In the belief that so many of our symphony orchestras are not of today's world, it has called itself the Symphony of the New World. The Symphony has been granted tax exempt status by the Department of Internal Revenue so that tax deductible contributions can be made to support what may well be the most important culture venture of our time.On October 11, 1965, Leonard Bernstein wrote to Donald L. Engle, Director of The Martha Baird Rockefeller Fund for Music.

Dear Mr. Engle: It is a pleasure for me to be able to recommend The Symphony of the New World for a sizable grant. I have not actually heard the orchestra perform. But I have heard and known Mr. Steinberg, who conducted one of my theatre works 15 years ago (1950 Broadway production of ''Peter Pan''). He is extremely able and gifted; and I am sure that under his guidance the orchestra will flourish. Most important of all, of course, is the sociological impetus behind the project – a truly integrated symphony orchestra. The success of this project will certainly stimulate more of the same, and may provide us with our first big step out of the unfair and illogical situation in which we now find ourselves with the Negro musician. Respectfully yours, Leonard BernsteinThe Symphony received a grant of $5,000 "to be matched two for one", and was able to raise the required $10,000 with help from

American Airlines

American Airlines is a major airlines of the United States, major US-based airline headquartered in Fort Worth, Texas, within the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex. It is the Largest airlines in the world, largest airline in the world when measured ...

(which gave $1,000) and the National Endowment for the Arts

The National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) is an independent agency of the United States federal government that offers support and funding for projects exhibiting artistic excellence. It was created in 1965 as an independent agency of the federal ...

(which gave $25,000 in 1967); the New York State Council on the Arts

The New York State Council on the Arts (NYSCA) is an arts council serving the U.S. state of New York. It was established in 1960 through a bill introduced in the New York State Legislature by New York State Senator MacNeil Mitchell (1905–1996), ...

undertook to subsidize concerts in low-income New York City neighborhoods. During its lifetime, the orchestra was also supported by the Ford Foundation

The Ford Foundation is an American private foundation with the stated goal of advancing human welfare. Created in 1936 by Edsel Ford and his father Henry Ford, it was originally funded by a US$25,000 gift from Edsel Ford. By 1947, after the death ...

, the Exxon

ExxonMobil Corporation (commonly shortened to Exxon) is an American multinational oil and gas corporation headquartered in Irving, Texas. It is the largest direct descendant of John D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil, and was formed on November 30, ...

Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts

The National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) is an independent agency of the United States federal government that offers support and funding for projects exhibiting artistic excellence. It was created in 1965 as an independent agency of the federal ...

.

Many successful concerts and collaborations followed. James DePreist

James Anderson DePreist (November 21, 1936 – February 8, 2013) was an American conductor. DePreist was one of the first African-American conductors on the world stage. He was the director emeritus of conducting and orchestral studies at T ...

was the Symphony’s principal guest conductor. John Hammond was President of the Board of Directors, which included Marian Anderson

Marian Anderson (February 27, 1897April 8, 1993) was an American contralto. She performed a wide range of music, from opera to Spiritual (music), spirituals. Anderson performed with renowned orchestras in major concert and recital venues throu ...

, Leontyne Price

Mary Violet Leontyne Price (born February 10, 1927) is an American soprano who was the first African Americans, African American soprano to receive international acclaim. From 1961 she began a long association with the Metropolitan Opera, where s ...

, and Zero Mostel. Anderson and Mostel were also patron artists, along with the Modern Jazz Quartet

The Modern Jazz Quartet (MJQ) was a jazz combo established in 1952 that played music influenced by classical music, classical, cool jazz, blues and bebop. For most of its history the Quartet consisted of John Lewis (pianist), John Lewis (piano), ...

, George Shirley

George Irving Shirley (born April 18, 1934) is an American operatic tenor, and was the first African-American tenor to perform a leading role at the Metropolitan Opera in New York City.

Early life

Shirley was born in Indianapolis, Indiana, and r ...

and William Warfield.

There were also breakthroughs. Marilyn Dubow, a soloist with the symphony, won a seat in the New York Philharmonic

The New York Philharmonic, officially the Philharmonic-Symphony Society of New York, Inc., globally known as New York Philharmonic Orchestra (NYPO) or New York Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra, is a symphony orchestra based in New York City. It is ...

as the first female violinist. Elayne Jones, one of the founders, joined the San Francisco Symphony as its first black woman timpanist. Thinking back on her days with the Symphony of the New World, Jones remembers, "The legitimacy of our organization was not acceptable until we had people who were supporting us. We had to have donations to begin to establish as a viable organization and to get union support! We had to begin getting players for this orchestra. All I remember is how complicated it was and what we went through. We had to also deal with those who said it couldn’t be done."

In 1968, the Symphony of the New World performed the premiere of ''Address for Orchestra'', composed by concert pianist and Smith College professor George Walker George Walker may refer to:

Arts and letters

* George Walker (chess player) (1803–1879), English chess player and writer

*George Walker (composer) (1922–2018), American composer

* George Walker (illustrator) (1781–1856), author of ''The Co ...

, at the High School of Music & Art

The High School of Music & Art, informally known as "Music & Art" (or "M&A"), was a public specialized high school located at 443-465 West 135th Street in the borough of Manhattan, New York, from 1936 until 1984. In 1961, Music & Art and the High ...

in Harlem. They performed it again the following day at Lincoln Center

Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts (also simply known as Lincoln Center) is a complex of buildings in the Lincoln Square neighborhood on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. It has thirty indoor and outdoor facilities and is host to 5 millio ...

. In a special concert for Black History Month

Black History Month is an annual observance originating in the United States, where it is also known as African-American History Month. It has received official recognition from governments in the United States and Canada, and more recently ...

in 1974, the Symphony premiered Wade Marcus Wade Marcus was a music producer and arranger associated with the Motown sound during the 1970s. He composed the music to the film ''The Final Comedown'' with Grant Green. He also produced albums by The Blackbyrds, Gary Bartz, A Taste of Honey, T ...

' ''A Moorish Sonata'' and also, with Ruggiero Ricci, the 1864 ''Concerto for Violin and Orchestra'' by the Cuban composer Joseph White that had been rediscovered by Paul Glass, a professor at Brooklyn College

Brooklyn College is a public university in Brooklyn, Brooklyn, New York. It is part of the City University of New York system and enrolls about 15,000 undergraduate and 2,800 graduate students on a 35-acre campus.

Being New York City's first publ ...

.

In a 1969 concert, Mostel occasioned hilarity, including reportedly among the orchestra players, in his conducting debut with Rossini's overture to ''Semiramide

''Semiramide'' () is an opera in two acts by Gioachino Rossini.

The libretto by Gaetano Rossi is based on Voltaire's tragedy ''Semiramis'', which in turn was based on the legend of Semiramis of Assyria. The opera was first performed at La Fenice ...

''.

End of the orchestra

By 1971, the orchestra and its supporters had great hopes for the season, but the 1971 season was never completed. One of the things Steinberg used to do was ask principal players to sit second chair, so an up-and-coming musician could have a chance to gain experience. Everyone was happy to do it, until one person changed his mind. Two factions emerged. Eventually Steinberg had to resign backstage at Philharmonic Hall just before a concert on 12 December 1971, so the concert could go on. He conducted the concert nonetheless. The dispute went to arbitration, and control of the Symphony of the New World was taken away from Steinberg on 12 June 1972. "Egos", said Joe Wilder. "It was all about egos. I had been very proud to be a member of the orchestra, but I was annoyed at some of the racial overtones to Ben Steinberg’s resigning." Jazz writer Ed Berger’s biography of Joe Wilder also quotes founding member and violist Alfred Brown: "There were some people – not the majority – who had a problem with him. Some of them felt the conductor should be black. I was not one of them. I liked him very much. He was very idealistic." On 1 February 1972, Benjamin Steinberg wrote his last fundraising letter. It said: "It is with sincere regret that we must advise that, due to an internal controversy as well as unforeseen financial difficulties arising from the current general economic situation, the Symphony of the New World is canceling the rest of the 1971–1972 concert season. Not only have we sustained the economic pinch facing all non-profit cultural institutions this season, but because of the difficulties, some $100,000 in scheduled grants could not be received in time to permit the completion of this concert season." Later that year, after an arbitration process, the symphony regrouped under a new board of directors and new music director Everett Lee, who had been one of the African American guest conductors brought in by Steinberg. Over the following few years, the orchestra persevered with an ambitious series of concerts, making its debut in Washington, D.C., in October 1975 and returning to Carnegie Hall as its home base the same month. In March 1977, a ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' reviewer praised the performers' "technical security", judging the twelfth season the orchestra's best. However, funding remained a perennial problem. In February 1975, the orchestra was forced to cancel a scheduled concert for financial reasons. Conductor George Byrd, who had led the symphony in an October 29, 1972, concert, remarked, "It seems to me macabre that the Black Panthers find it easier to raise money than the Symphony of the New World." The 1977–78 season seems to have been the symphony’s swan song. ''The New York Times'' Arts and Leisure section lists a Symphony of the New World concert for Sunday, April 9, 1978, and no dates beyond that. The groundbreaking orchestra seems to have dissolved without fanfare or even an announcement.

Despite its inglorious end, the musicians who were part of the Symphony of the New World felt proud to be a part of the project. "It built hope where there was very little", flutist Harold Jones said. "It showed that, as black people, we had paid our dues and we could do it as well as anyone else. It was such a moment in life that I’m overwhelmed with it. I just wish it could have lasted. The inspiration that this could be done emainsin all of us."

A commemorative exhibit on the 50th anniversary of the founding of the Symphony of the New World was held at the New York Public Library

The New York Public Library (NYPL) is a public library system in New York City. With nearly 53 million items and 92 locations, the New York Public Library is the second largest public library in the United States (behind the Library of Congress ...

in 2014. The orchestra's papers reside at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture

The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture is a research library of the New York Public Library (NYPL) and an archive repository for information on people of African descent worldwide. Located at 515 Malcolm X Boulevard (Lenox Avenue) b ...

.

"Concert Black" by Terrance McKnight

The Symphony of the New World will be a focus of WQXR host's Terrance McKnight's upcoming book, ''Concert Black''. In an article for ''National Sawdust'' magazine, he wrote: "In many American cities you’ll find two communities of classical musicians and organizations: one Black and one white. A focal point in ''Concert Black'' is a moment when those two communities came together in New York in the 1960s to form the first professionally integrated orchestra in the country. The Symphony of the New World played concerts from 1965–1978, and at one point more than 80% of its subscribers were people of color. "The Symphony of the New World was successful in building new audiences for and for accomplishing multiculturalism in the concert hall. Duke Ellington and the Modern Jazz Quartet performed with this orchestra. Marian Anderson and Martina Arroyo appeared with the orchestra. There were Black conductors and composers regularly represented and more than a few Asian musicians were in the ranks, which was rare for the times. The Symphony of the New World was where our cultural institutions say they want to be."References

{{authority control 1965 establishments in New York City 1978 disestablishments in New York (state) Symphony orchestras Disbanded American orchestras Musical groups established in 1965 Musical groups disestablished in 1978 Musical groups from New York City