Science and Technology in the Ottoman Empire on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

During its 600-year existence, the Ottoman Empire made significant advances in science and technology, in a wide range of fields including mathematics, astronomy and medicine.

The Islamic Golden Age was traditionally believed to have ended in the thirteenth century, but has been extended to the fifteenth George Saliba (1994), ''A History of Arabic Astronomy: Planetary Theories During the Golden Age of Islam'', pp. 245, 250, 256–7,

Factors Behind the Decline of Islamic Science After the Sixteenth Century

/ref> centuries by some, who have included continuing scientific activity in the Ottoman Empire in the west and in

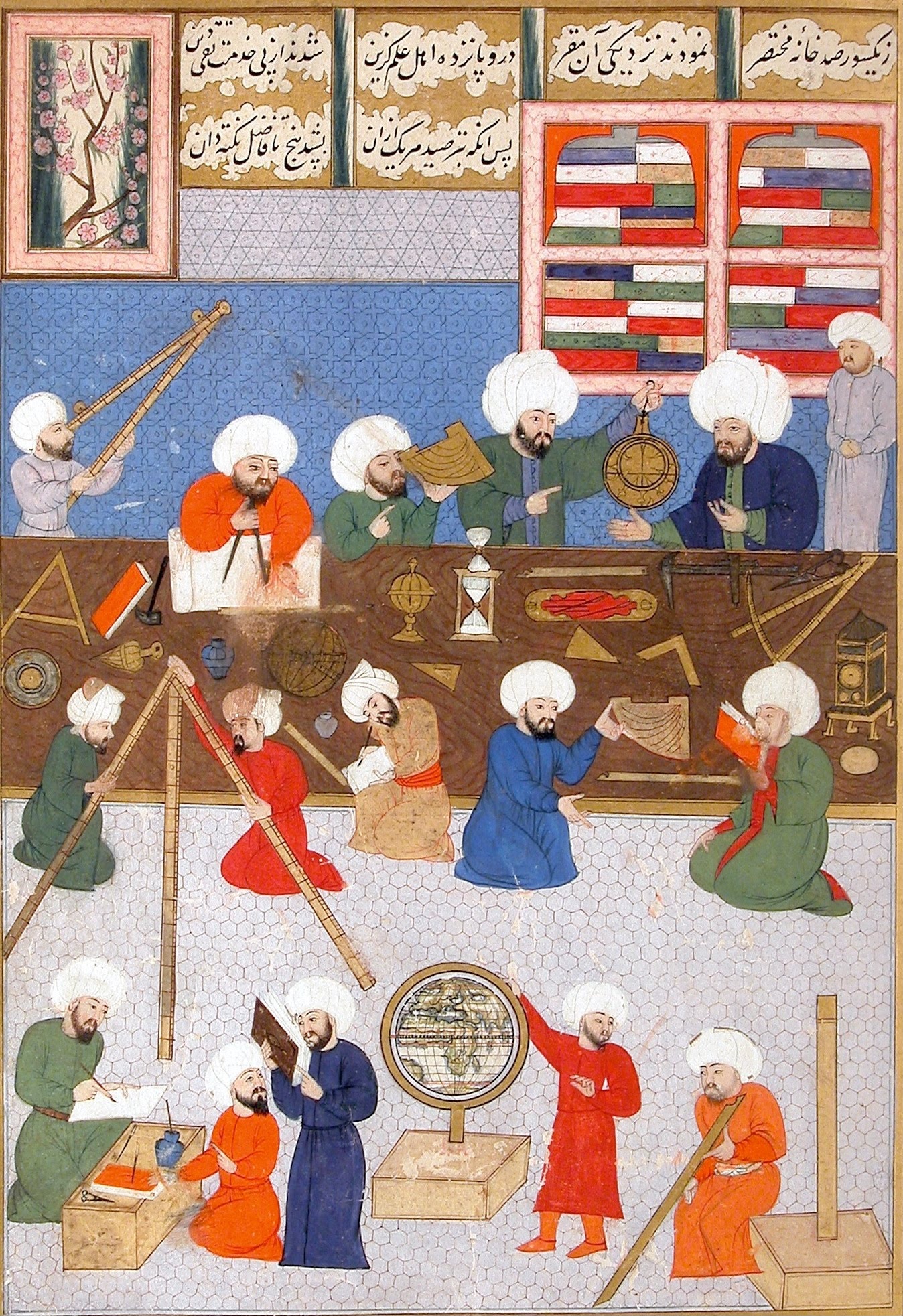

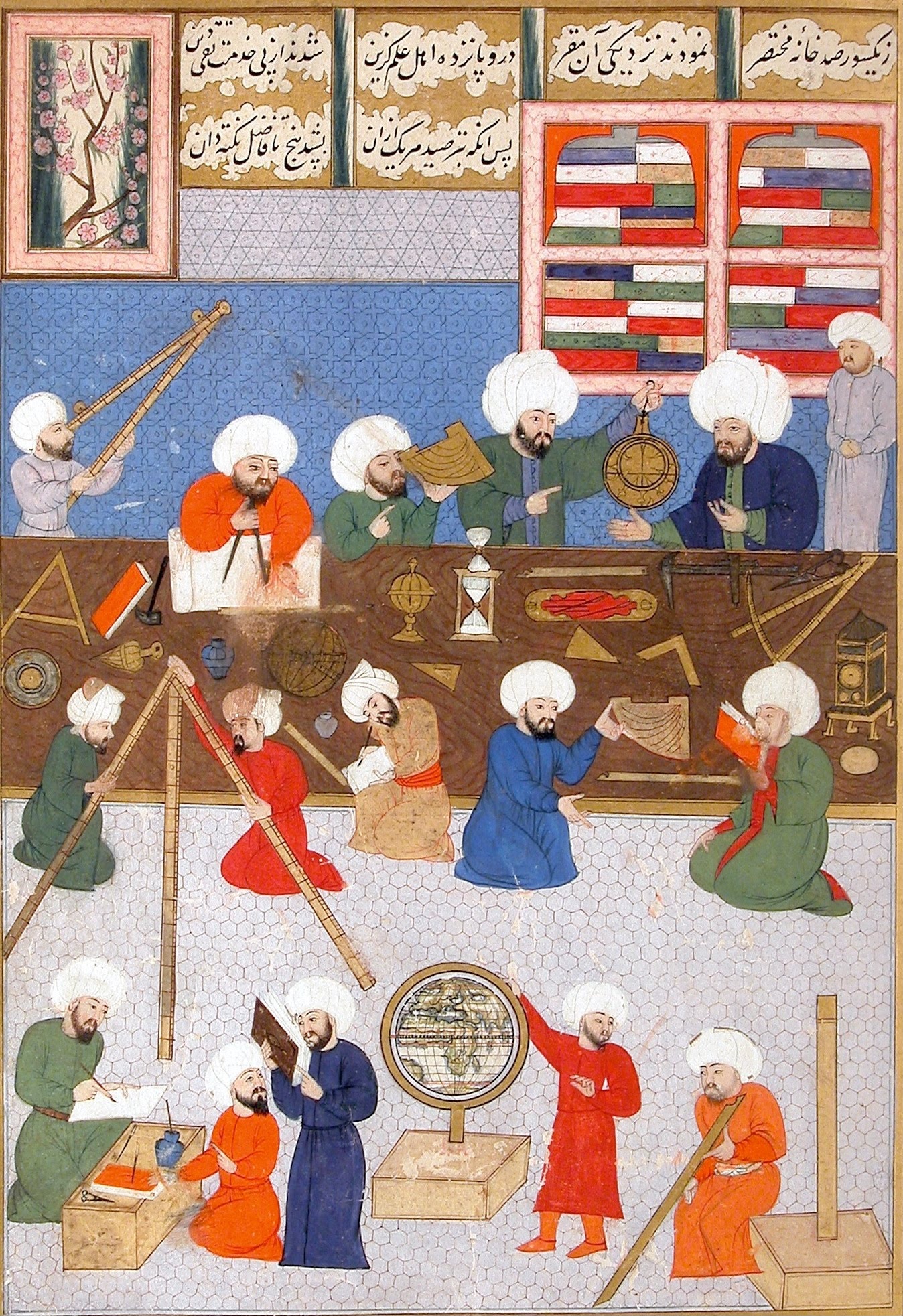

Taqi al-Din later built the Constantinople Observatory of Taqi ad-Din in 1577, where he carried out astronomical observations until 1580. He produced a

Taqi al-Din later built the Constantinople Observatory of Taqi ad-Din in 1577, where he carried out astronomical observations until 1580. He produced a

Medicine in the Ottoman Empire was practiced in nearly all places of society as physicians treated patients in homes, markets, and hospitals. Treatment at these different locations were generally the same, but different modalities of treatment existed throughout the Ottoman Empire. Different methodologies included humoral principles, curative medicine, preventative medicine, and prophetic medicine. Ottoman hospitals also adopted the concept of integralism in which a holistic approach to treatment was used. Considerations of this approach included quality of life and care and treatment of both physical and mental health. The integralistic approach shaped the structure of the Ottoman hospital as each sector and group of workers was dedicated to treating a different aspect of the patient's well-being. All shared the general consensus of treating patients with kindness and gentility, but physicians treated the physical body, and musicians used music therapy to treat the mind. Music was regarded as a powerful healing tune and that different sounds had the ability to create different mental states of health.

One of the original building blocks of early Ottoman medicine was

Medicine in the Ottoman Empire was practiced in nearly all places of society as physicians treated patients in homes, markets, and hospitals. Treatment at these different locations were generally the same, but different modalities of treatment existed throughout the Ottoman Empire. Different methodologies included humoral principles, curative medicine, preventative medicine, and prophetic medicine. Ottoman hospitals also adopted the concept of integralism in which a holistic approach to treatment was used. Considerations of this approach included quality of life and care and treatment of both physical and mental health. The integralistic approach shaped the structure of the Ottoman hospital as each sector and group of workers was dedicated to treating a different aspect of the patient's well-being. All shared the general consensus of treating patients with kindness and gentility, but physicians treated the physical body, and musicians used music therapy to treat the mind. Music was regarded as a powerful healing tune and that different sounds had the ability to create different mental states of health.

One of the original building blocks of early Ottoman medicine was

In 1574, Taqi al-Din (1526–1585) wrote the last major Arabic work on optics, entitled ''Kitab Nūr hadaqat al-ibsār wa-nūr haqīqat al-anzār'' (''Book of the Light of the Pupil of Vision and the Light of the Truth of the Sights''), which contains

In 1574, Taqi al-Din (1526–1585) wrote the last major Arabic work on optics, entitled ''Kitab Nūr hadaqat al-ibsār wa-nūr haqīqat al-anzār'' (''Book of the Light of the Pupil of Vision and the Light of the Truth of the Sights''), which contains

The Ottoman engineer Taqi al-Din invented a mechanical

The Ottoman engineer Taqi al-Din invented a mechanical

The Ottoman Empire in the 16th century was known for their military power throughout southern Europe and the Middle East. The

The Ottoman Empire in the 16th century was known for their military power throughout southern Europe and the Middle East. The

New York University Press

New York University Press (or NYU Press) is a university press that is part of New York University.

History

NYU Press was founded in 1916 by the then chancellor of NYU, Elmer Ellsworth Brown.

Directors

* Arthur Huntington Nason, 1916–1932 ...

, and sixteenthAhmad Y Hassan

Ahmad Yousef Al-Hassan ( ar, links=no, أحمد يوسف الحسن) (June 25, 1925 – April 28, 2012) was a Palestinian/Syrian/Canadian historian of Arabic and Islamic science and technology, educated in Jerusalem, Cairo, and London with a PhD i ...

Factors Behind the Decline of Islamic Science After the Sixteenth Century

/ref> centuries by some, who have included continuing scientific activity in the Ottoman Empire in the west and in

Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

and Mughal India

The Mughal Empire was an early-modern empire that controlled much of South Asia between the 16th and 19th centuries. Quote: "Although the first two Timurid emperors and many of their noblemen were recent migrants to the subcontinent, the d ...

in the east.

Education

Advancement of madrasah

Themadrasah

Madrasa (, also , ; Arabic: مدرسة , pl. , ) is the Arabic word for any type of educational institution, secular or religious (of any religion), whether for elementary instruction or higher learning. The word is variously transliterated '' ...

education institution, which first originated during the Seljuk Seljuk or Saljuq (سلجوق) may refer to:

* Seljuk Empire (1051–1153), a medieval empire in the Middle East and central Asia

* Seljuk dynasty (c. 950–1307), the ruling dynasty of the Seljuk Empire and subsequent polities

* Seljuk (warlord) (di ...

period, reached its highest point during the Ottoman reign.İnalcık, Halil. 1973. "Learning, the Medrese, and the Ulema." In ''The Ottoman Empire: The Classical Age 1300–1600''. New York: Praeger, pp. 165–178.

Education of Ottoman Women in Medicine

Harem

Harem (Persian: حرمسرا ''haramsarā'', ar, حَرِيمٌ ''ḥarīm'', "a sacred inviolable place; harem; female members of the family") refers to domestic spaces that are reserved for the women of the house in a Muslim family. A hare ...

s were places within a Sultan's palace where his wives, daughters, and female slaves were expected to stay. However, accounts of teaching young girls and boys here have been recorded. Most education of women in the Ottoman Empire was focused on teaching the women to be good house wives and social etiquette. Although the formal education of women was not popular, female physicians and surgeons were still accounted for. Female physicians were given an informal education instead of a formal one. However, the first properly trained female Turkish physician was Safiye Ali

Safiye Ali (2 February 1894 – 5 July 1952) was a Turkish physician, the first female medical doctor of the Republic of Turkey. She was a graduate of Robert College in Istanbul. She treated soldiers in the Balkan Wars, World War I, and the Turkis ...

. Ali studied medicine in Germany and opened her own practice in Istanbul

Istanbul ( , ; tr, İstanbul ), formerly known as Constantinople ( grc-gre, Κωνσταντινούπολις; la, Constantinopolis), is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, serving as the country's economic, ...

in 1922, 1 year before the fall of the Ottoman Empire

The dissolution of the Ottoman Empire (1908–1922) began with the Young Turk Revolution which restored the constitution of 1876 and brought in multi-party politics with a two-stage electoral system for the Ottoman parliament. At the same ti ...

.

Technical education

Istanbul Technical University

Istanbul Technical University ( tr, İstanbul Teknik Üniversitesi, commonly referred to as ITU or The Technical University) is an international technical university located in Istanbul, Turkey. It is the world's third-oldest technical university ...

has a history that began in 1773. It was founded by Sultan Mustafa III

Mustafa III (; ''Muṣṭafā-yi sālis''; 28 January 1717 – 21 January 1774) was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1757 to 1774. He was a son of Sultan Ahmed III (1703–30), and his consort Mihrişah Kadın. He was succeeded by his ...

as the Imperial Naval Engineers' School (original name: Mühendishane-i Bahr-i Humayun), and it was originally dedicated to the training of ship builders and cartographers. In 1795 the scope of the school was broadened to train technical military staff to modernize the Ottoman army to match the European standards. In 1845 the engineering department of the school was further developed with the addition of a program devoted to the training of architects. The scope and name of the school were extended and changed again in 1883 and in 1909 the school became a public engineering school which was aimed at training civil engineers

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who invent, design, analyze, build and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while considering the limit ...

who could create new infrastructure to develop the empire.

Sciences

Astronomy

Taqi al-Din later built the Constantinople Observatory of Taqi ad-Din in 1577, where he carried out astronomical observations until 1580. He produced a

Taqi al-Din later built the Constantinople Observatory of Taqi ad-Din in 1577, where he carried out astronomical observations until 1580. He produced a Zij

A zij ( fa, زيج, zīj) is an Islamic astronomical book that tabulates parameters used for astronomical calculations of the positions of the Sun, Moon, stars, and planets.

Etymology

The name ''zij'' is derived from the Middle Persian term ' ...

(named ''Unbored Pearl'') and astronomical catalog

An astronomical catalog or catalogue is a List (information), list or tabulation of astronomical objects, typically grouped together because they share a common type, Galaxy morphological classification, morphology, origin, means of detection, or ...

ues that were more accurate than those of his contemporaries, Tycho Brahe

Tycho Brahe ( ; born Tyge Ottesen Brahe; generally called Tycho (14 December 154624 October 1601) was a Danish astronomer, known for his comprehensive astronomical observations, generally considered to be the most accurate of his time. He was k ...

and Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic Church, Catholic cano ...

. Taqi al-Din was also the first astronomer to employ a decimal point

A decimal separator is a symbol used to separate the integer part from the fractional part of a number written in decimal form (e.g., "." in 12.45). Different countries officially designate different symbols for use as the separator. The choi ...

notation in his observation

Observation is the active acquisition of information from a primary source. In living beings, observation employs the senses. In science, observation can also involve the perception and recording of data via the use of scientific instruments. The ...

s rather than the sexagesimal

Sexagesimal, also known as base 60 or sexagenary, is a numeral system with sixty as its base. It originated with the ancient Sumerians in the 3rd millennium BC, was passed down to the ancient Babylonians, and is still used—in a modified form� ...

fractions used by his contemporaries and predecessors. He also made use of Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (973 – after 1050) commonly known as al-Biruni, was a Khwarazmian Iranian in scholar and polymath during the Islamic Golden Age. He has been called variously the "founder of Indology", "Father of Co ...

's method of "three points observation". In ''The Nabk Tree'', Taqi al-Din described the three points as "two of them being in opposition in the ecliptic

The ecliptic or ecliptic plane is the orbital plane of the Earth around the Sun. From the perspective of an observer on Earth, the Sun's movement around the celestial sphere over the course of a year traces out a path along the ecliptic again ...

and the third in any desired place." He used this method to calculate the eccentricity

Eccentricity or eccentric may refer to:

* Eccentricity (behavior), odd behavior on the part of a person, as opposed to being "normal"

Mathematics, science and technology Mathematics

* Off-center, in geometry

* Eccentricity (graph theory) of a v ...

of the Sun's orbit and the annual motion of the apogee

An apsis (; ) is the farthest or nearest point in the orbit of a planetary body about its primary body. For example, the apsides of the Earth are called the aphelion and perihelion.

General description

There are two apsides in any ellip ...

, and so did Copernicus before him, and Tycho Brahe shortly afterwards. He also invented a variety of other astronomical instruments, including accurate mechanical astronomical clock

An astronomical clock, horologium, or orloj is a clock with special mechanisms and dials to display astronomical information, such as the relative positions of the Sun, Moon, zodiacal constellations, and sometimes major planets.

Definition

...

s from 1556 to 1580.Due to his observational clock and other more accurate instruments Taqi al-Din's values were more accurate.Sevim Tekeli, "Taqi al-Din", in Helaine Selin (1997), ''Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures'', Kluwer Academic Publishers

Springer Science+Business Media, commonly known as Springer, is a German multinational publishing company of books, e-books and peer-reviewed journals in science, humanities, technical and medical (STM) publishing.

Originally founded in 1842 in ...

, .

After the destruction of the Constantinople observatory of Taqi al-Din in 1580, astronomical activity stagnated in the Ottoman Empire, until the introduction of Copernican heliocentrism

Copernican heliocentrism is the astronomical model developed by Nicolaus Copernicus and published in 1543. This model positioned the Sun at the center of the Universe, motionless, with Earth and the other planets orbiting around it in circular pa ...

in 1660, when the Ottoman scholar Ibrahim Efendi al-Zigetvari Tezkireci translated Noël Duret's French astronomical work (written in 1637) into Arabic.

Geography

Ottoman admiralPiri Reis

Ahmet Muhiddin Piri ( 1465 – 1553), better known as Piri Reis ( tr, Pîrî Reis (military rank), Reis or ''Hacı Ahmet Muhittin Pîrî Bey''), was a Navigation, navigator, Geography in medieval Islam, geographer and Cartography, cartographer. ...

( tr, Pîrî Reis

Reis may refer to :

*Reis (surname), a Portuguese and German surname

*Reis (military rank), an Ottoman military rank and obscure Lebanese/Syrian noble title

Currency

*Portuguese Indian rupia (subdivided into ''réis''), the currency of Portugues ...

or ''Hacı

Hacı is the Turkish spelling of the title and epithet Hajji. It may refer to:

People

* Hacı I Giray (died 1466), founder and the first ruler of the Crimean Khanate

* Hacı Ahmet ( 1566), purported Turkish cartographer

* Hacı Arif Bey (1831� ...

Ahmet Muhittin Pîrî Bey

Bey ( ota, بك, beğ, script=Arab, tr, bey, az, bəy, tk, beg, uz, бек, kz, би/бек, tt-Cyrl, бәк, translit=bäk, cjs, пий/пек, sq, beu/bej, sh, beg, fa, بیگ, beyg/, tg, бек, ar, بك, bak, gr, μπέης) is ...

'') was a navigator

A navigator is the person on board a ship or aircraft responsible for its navigation.Grierson, MikeAviation History—Demise of the Flight Navigator FrancoFlyers.org website, October 14, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2014. The navigator's primar ...

, geographer

A geographer is a physical scientist, social scientist or humanist whose area of study is geography, the study of Earth's natural environment and human society, including how society and nature interacts. The Greek prefix "geo" means "earth" a ...

and cartographer

Cartography (; from grc, χάρτης , "papyrus, sheet of paper, map"; and , "write") is the study and practice of making and using maps. Combining science, aesthetics and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality (or an im ...

active in the early 1500s. He is known today for his maps and charts collected in his ''Kitab-ı Bahriye'' (''Book of Navigation''), and for the Piri Reis map

The Piri Reis map is a world map compiled in 1513 by the Ottoman admiral and cartographer Piri Reis. Approximately one third of the map survives; it shows the western coasts of Europe and North Africa and the coast of Brazil with reasonable accu ...

, one of the oldest maps of America still in existence.

His book contains detailed information on navigation, as well as accurate charts (for their time) describing the important port

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as Ham ...

s and cities of the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ea ...

. His world map, drawn in 1513, is the oldest known Turkish atlas showing the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 3 ...

. The map was rediscovered by German theologian Gustav Adolf Deissmann

Gustav Adolf Deissmann (7 November 1866 – 5 April 1937) was a German Protestant theologian, best known for his leading work on the Greek language used in the New Testament, which he showed was the ''koine'', or commonly used tongue of the He ...

in 1929 in the course of work cataloging items held by the Topkapı Palace

The Topkapı Palace ( tr, Topkapı Sarayı; ota, طوپقپو سرايى, ṭopḳapu sarāyı, lit=cannon gate palace), or the Seraglio

A seraglio, serail, seray or saray (from fa, سرای, sarāy, palace, via Turkish and Italian) i ...

library.

Medicine

Medicine in the Ottoman Empire was practiced in nearly all places of society as physicians treated patients in homes, markets, and hospitals. Treatment at these different locations were generally the same, but different modalities of treatment existed throughout the Ottoman Empire. Different methodologies included humoral principles, curative medicine, preventative medicine, and prophetic medicine. Ottoman hospitals also adopted the concept of integralism in which a holistic approach to treatment was used. Considerations of this approach included quality of life and care and treatment of both physical and mental health. The integralistic approach shaped the structure of the Ottoman hospital as each sector and group of workers was dedicated to treating a different aspect of the patient's well-being. All shared the general consensus of treating patients with kindness and gentility, but physicians treated the physical body, and musicians used music therapy to treat the mind. Music was regarded as a powerful healing tune and that different sounds had the ability to create different mental states of health.

One of the original building blocks of early Ottoman medicine was

Medicine in the Ottoman Empire was practiced in nearly all places of society as physicians treated patients in homes, markets, and hospitals. Treatment at these different locations were generally the same, but different modalities of treatment existed throughout the Ottoman Empire. Different methodologies included humoral principles, curative medicine, preventative medicine, and prophetic medicine. Ottoman hospitals also adopted the concept of integralism in which a holistic approach to treatment was used. Considerations of this approach included quality of life and care and treatment of both physical and mental health. The integralistic approach shaped the structure of the Ottoman hospital as each sector and group of workers was dedicated to treating a different aspect of the patient's well-being. All shared the general consensus of treating patients with kindness and gentility, but physicians treated the physical body, and musicians used music therapy to treat the mind. Music was regarded as a powerful healing tune and that different sounds had the ability to create different mental states of health.

One of the original building blocks of early Ottoman medicine was humoralism

Humorism, the humoral theory, or humoralism, was a system of medicine detailing a supposed makeup and workings of the human body, adopted by Ancient Greek and Roman physicians and philosophers.

Humorism began to fall out of favor in the 1850s ...

, and the concept of illness to be a result of disequilibrium among the four humors of the body. The four physiological humors each related to one of the four elements: blood and air, phlegm and water, black bile and earth, yellow bile and fire.

Medicinal treatments in early Ottoman medicine often include the use of foods and beverages. Coffee, taken both medicinally and recreationally, was used to treat stomach problems and indigestion by working as a laxative. The stimulant properties of coffee eventually gained recognition and coffee was used to curb fatigue and exhaustion. The use of coffee in medicinal senses was done more in practice by civilians than hospital professionals.

Hospitals and related health-care institutions were referred to as a variety of names: ''dârüşşifâ'', ''dârüssıhhâ'', ''şifâhâne'', ''bîmaristân'', ''bîmarhâne'', and ''timarhâne''. Hospitals were ''vakif'' institutions, dedicated to charity and offering care to people of all social classes. The aesthetic aspects of the hospitals, including gardens and architecture, were said to be "healing by design". The hospitals also included hammams, or bathhouses, to treat the patients' humors.

The first Ottoman hospital established was the Faith Complex ''dârüşşifâ'' in 1470; it closed in 1824. Unique features of the hospital were the separation of patients by sex and the use of music to treat the mentally ill. The Bâyezîd ''Dârüşşifâ'' was founded in 1488 and is most recognized for its unique architecture that served as an influence an influence in the architecture of later European hospitals. The hospital built by Ayşe Hafsa Sulta in 1522 is recognized as one of the most esteemed hospitals of the Ottoman Empire. The hospital devoted a separate wing for the mentally ill, until later limiting all treatment to only the mentally ill. The ''bîmârîstâns ''medrese

Madrasa (, also , ; Arabic: مدرسة , pl. , ) is the Arabic word for any type of educational institution, secular or religious (of any religion), whether for elementary instruction or higher learning. The word is variously transliterated '' ...

'' provided medical students with combined theoretical and clinical coursework through hospital internships.

Notable Ottoman medical literature includes the work of the Jewish doctor Mûsâ b. Hamun who wrote one of the first literature primarily about dentistry. Hamun also wrote ''Risâle fî Tabâyi’l-Edviye ve İsti’mâlihâ'', which used a combination of Hebrew, Arabic, Greek, and European works to transfer European knowledge of medicine to the Ottoman realm. The writer Ibn Cânî, after noticing the prevalence of tobacco use in Turkey, translated Spanish and Arabic works discussing the use of tobacco leaf in medical treatment. The physician Ömer b. Sinan el-İznikî’s works follow the theme of the Chemical Medicine movement and in his two books, ''Kitâb-I Künûz-I Hayâti’l-İnsân'' and ''Kanûn-I Etibbâ-yi Feylosofân'', enclosing directions for the production of medicines. One of the key contributors to Ottoman medical education was Şânizâde Mehmed Atâullah Efendi, whose ''Hamse-I Şânizâde'' presented modern European anatomy to Ottoman medicine. In 1873, Cemaleddin Efendi and a group of students from the Imperial Medical School put out the ''Lügat-I Tıbbiye'', the first modern medical dictionary written in Turkish. Şerafeddin Sabuncuoğlu was the author of the ''Cerrahiyyetu'l-Haniyye'' (''Imperial Surgery''), the first illustrated surgical atlas, and the ''Mücerrebname'' (''On Attemption''). The ''Cerrahiyyetu'l-Haniyye'' (''Imperial Surgery'') was the first surgical atlas and the last major medical encyclopedia from the Islamic world. Though his work was largely based on Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi

Abū al-Qāsim Khalaf ibn al-'Abbās al-Zahrāwī al-Ansari ( ar, أبو القاسم خلف بن العباس الزهراوي; 936–1013), popularly known as al-Zahrawi (), Latinised as Albucasis (from Arabic ''Abū al-Qāsim''), was ...

's ''Al-Tasrif

The ''Kitāb al-Taṣrīf'' ( ar, كتاب التصريف لمن عجز عن التأليف, lit=The Arrangement of Medical Knowledge for One Who is Not Able to Compile a Book for Himself), known in English as The Method of Medicine, is a 30-volume ...

'', Sabuncuoğlu introduced many innovations of his own. Female surgeons were also illustrated for the first time in the ''Cerrahiyyetu'l-Haniyye''.

The first modern medical school of the Ottoman Empire was the Naval Medical School, or ''Tersâne Tıbbiyesi'', established in January 1806. The education of the school was largely European-based, using texts in Italian or French and medical journals published in Europe. Behçet Efendi founded the Imperial Medical School, ''Tıbhâne-I Âmire'', of Istanbul in 1827 which was based on the following structural guidelines: the acceptance only of Muslim students, and the teachings would be almost entirely in French. In 1839, after Tanzimat

The Tanzimat (; ota, تنظيمات, translit=Tanzimāt, lit=Reorganization, ''see'' nizām) was a period of reform in the Ottoman Empire that began with the Gülhane Hatt-ı Şerif in 1839 and ended with the First Constitutional Era in 1876. ...

reforms, the school was opened to non-Muslim individuals as well. After this point, non-Muslim students became the majority of graduating class and were better able to adapt and take advantage of the European-based education as many of them already spoke French and were placed into the higher ranking class in the school. The Civilian Medical School (''Mekteb-I Tıbbiye-I Mülkiye'') was founded in 1866 to raise the number of Muslim doctors. The school’s teachings were done in Turkish and focused on training students to become civilian physicians rather than military physicians.

Ottoman medicine in the mid-nineteenth century developed institutions for preventative medicine and public health. A quarantine office and quarantine council, the ''Meclis-I Tahaffuz-I Ulâ'' were established. The council eventually became an international organization with participation from European countries, the United States, Iran, and Russia. The Quarantine Administration, founded in 1838, established permanent anti-plague quarantines, based on the western Mediterranean quarantine model, throughout the Ottoman Empire.

The Ottoman Empire was also home to many institutions organized for the purpose of inoculation vaccination research and investigations. In Istanbul, the İstanbul Rabies and Bacteriological Laboratory was founded in 1877 for research in microbiology and the testing of rabies inoculation. The Smallpox Vaccination Laboratory and the Imperial Vaccination Center were also created in the late nineteenth century.

The first Ottoman hospital, Dar al-Shifa

A bimaristan (; ), also known as ''dar al-shifa'' (also ''darüşşifa'' in Turkish) or simply maristan, is a hospital in the historic Islamic world.

Etymology

''Bimaristan'' is a Persian word ( ''bīmārestān'') meaning "hospital", with ' ...

(literally "house of health"), was built in the Ottoman’s capital city of Bursa

( grc-gre, Προῦσα, Proûsa, Latin: Prusa, ota, بورسه, Arabic:بورصة) is a city in northwestern Turkey and the administrative center of Bursa Province. The fourth-most populous city in Turkey and second-most populous in the ...

in 1399. This hospital and the ones built after were structured similarly to the ones of the Seljuk Empire

The Great Seljuk Empire, or the Seljuk Empire was a high medieval, culturally Turco-Persian tradition, Turko-Persian, Sunni Islam, Sunni Muslim empire, founded and ruled by the Qiniq (tribe), Qïnïq branch of Oghuz Turks. It spanned a total are ...

, where "even wounded crusaders preferred Muslim doctors as they were very knowledgeable." However, in Ottoman hospitals, mentally ill patients were treated with music therapy

Music therapy, an allied health profession, "is the clinical and evidence-based use of music interventions to accomplish individualized goals within a therapeutic relationship by a credentialed professional who has completed an approved music th ...

in separated buildings that were still part of the hospital complex. Different mental illnesses were treated with different modes of music therapy. Ottoman Empire hospitals were primarily established and used for treating the sick then developed into centers for medical science teaching as well.

Physics

In 1574, Taqi al-Din (1526–1585) wrote the last major Arabic work on optics, entitled ''Kitab Nūr hadaqat al-ibsār wa-nūr haqīqat al-anzār'' (''Book of the Light of the Pupil of Vision and the Light of the Truth of the Sights''), which contains

In 1574, Taqi al-Din (1526–1585) wrote the last major Arabic work on optics, entitled ''Kitab Nūr hadaqat al-ibsār wa-nūr haqīqat al-anzār'' (''Book of the Light of the Pupil of Vision and the Light of the Truth of the Sights''), which contains experiment

An experiment is a procedure carried out to support or refute a hypothesis, or determine the efficacy or likelihood of something previously untried. Experiments provide insight into Causality, cause-and-effect by demonstrating what outcome oc ...

al investigations in three volumes on vision

Vision, Visions, or The Vision may refer to:

Perception Optical perception

* Visual perception, the sense of sight

* Visual system, the physical mechanism of eyesight

* Computer vision, a field dealing with how computers can be made to gain un ...

, the light

Light or visible light is electromagnetic radiation that can be perceived by the human eye. Visible light is usually defined as having wavelengths in the range of 400–700 nanometres (nm), corresponding to frequencies of 750–420 tera ...

's reflection Reflection or reflexion may refer to:

Science and technology

* Reflection (physics), a common wave phenomenon

** Specular reflection, reflection from a smooth surface

*** Mirror image, a reflection in a mirror or in water

** Signal reflection, in ...

, and the light's refraction

In physics, refraction is the redirection of a wave as it passes from one medium to another. The redirection can be caused by the wave's change in speed or by a change in the medium. Refraction of light is the most commonly observed phenomeno ...

. The book deals with the structure of light, its diffusion

Diffusion is the net movement of anything (for example, atoms, ions, molecules, energy) generally from a region of higher concentration to a region of lower concentration. Diffusion is driven by a gradient in Gibbs free energy or chemical p ...

and global refraction, and the relation between light and colour

Color (American English) or colour (British English) is the visual perceptual property deriving from the spectrum of light interacting with the photoreceptor cells of the eyes. Color categories and physical specifications of color are associ ...

. In the first volume, he discusses "the nature of light, the source of light, the nature of the propagation of light, the formation of sight, and the effect of light on the eye and sight". In the second volume, he provides "experimental proof of the specular reflection

Specular reflection, or regular reflection, is the mirror-like reflection of waves, such as light, from a surface.

The law of reflection states that a reflected ray of light emerges from the reflecting surface at the same angle to the surf ...

of accidental as well as essential light, a complete formulation of the laws of reflection, and a description of the construction and use of a copper instrument for measuring reflections from plane

Plane(s) most often refers to:

* Aero- or airplane, a powered, fixed-wing aircraft

* Plane (geometry), a flat, 2-dimensional surface

Plane or planes may also refer to:

Biology

* Plane (tree) or ''Platanus'', wetland native plant

* ''Planes' ...

, spherical, cylindrical, and conical mirror

A mirror or looking glass is an object that Reflection (physics), reflects an image. Light that bounces off a mirror will show an image of whatever is in front of it, when focused through the lens of the eye or a camera. Mirrors reverse the ...

s, whether convex or concave." The third volume "analyses the important question of the variations light undergoes while traveling in mediums

Mediumship is the practice of purportedly mediating communication between familiar spirits or spirits of the dead and living human beings. Practitioners are known as "mediums" or "spirit mediums". There are different types of mediumship or spir ...

having different densities

Density (volumetric mass density or specific mass) is the substance's mass per unit of volume. The symbol most often used for density is ''ρ'' (the lower case Greek language, Greek letter Rho (letter), rho), although the Latin letter ''D'' ca ...

, i.e. the nature of refracted light, the formation of refraction, the nature of images formed by refracted light."

Mechanical technology

In 1559, Taqi al-Din invented asix-cylinder

The straight-six engine (also referred to as an inline-six engine; abbreviated I6 or L6) is a piston engine with six cylinders arranged in a straight line along the crankshaft. A straight-six engine has perfect primary and secondary engine balan ...

'Monoblock' pump

A pump is a device that moves fluids (liquids or gases), or sometimes slurries, by mechanical action, typically converted from electrical energy into hydraulic energy. Pumps can be classified into three major groups according to the method they u ...

. It was a hydropower

Hydropower (from el, ὕδωρ, "water"), also known as water power, is the use of falling or fast-running water to Electricity generation, produce electricity or to power machines. This is achieved by energy transformation, converting the Pot ...

ed water

Water (chemical formula ) is an inorganic, transparent, tasteless, odorless, and nearly colorless chemical substance, which is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known living organisms (in which it acts as a ...

-raising machine

A machine is a physical system using Power (physics), power to apply Force, forces and control Motion, movement to perform an action. The term is commonly applied to artificial devices, such as those employing engines or motors, but also to na ...

incorporating valve

A valve is a device or natural object that regulates, directs or controls the flow of a fluid (gases, liquids, fluidized solids, or slurries) by opening, closing, or partially obstructing various passageways. Valves are technically fittings ...

s, suction

Suction is the colloquial term to describe the air pressure differential between areas.

Removing air from a space results in a pressure differential. Suction pressure is therefore limited by external air pressure. Even a perfect vacuum cannot ...

and delivery pipes, piston

A piston is a component of reciprocating engines, reciprocating pumps, gas compressors, hydraulic cylinders and pneumatic cylinders, among other similar mechanisms. It is the moving component that is contained by a cylinder and is made gas-tig ...

rods with lead weights, trip

Trip may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Fictional characters

* Trip (''Pokémon''), a ''Pokémon'' character

* Trip (Power Rangers), in the American television series ''Time Force Power Rangers''

* Trip, in the 2013 film ''Metallica Through th ...

lever

A lever is a simple machine consisting of a beam or rigid rod pivoted at a fixed hinge, or ''fulcrum''. A lever is a rigid body capable of rotating on a point on itself. On the basis of the locations of fulcrum, load and effort, the lever is div ...

s with pin

A pin is a device used for fastening objects or material together.

Pin or PIN may also refer to:

Computers and technology

* Personal identification number (PIN), to access a secured system

** PIN pad, a PIN entry device

* PIN, a former Dutch ...

joint

A joint or articulation (or articular surface) is the connection made between bones, ossicles, or other hard structures in the body which link an animal's skeletal system into a functional whole.Saladin, Ken. Anatomy & Physiology. 7th ed. McGraw ...

s, and cam

Calmodulin (CaM) (an abbreviation for calcium-modulated protein) is a multifunctional intermediate calcium-binding messenger protein expressed in all eukaryotic cells. It is an intracellular target of the secondary messenger Ca2+, and the bind ...

s on the axle

An axle or axletree is a central shaft for a rotating wheel or gear. On wheeled vehicles, the axle may be fixed to the wheels, rotating with them, or fixed to the vehicle, with the wheels rotating around the axle. In the former case, bearing ...

of a water-driven scoop

Scoop, Scoops or The scoop may refer to:

Objects

* Scoop (tool), a shovel-like tool, particularly one deep and curved, used in digging

* Scoop (machine part), a component of machinery to carry things

* Scoop stretcher, a device used for casualty ...

-wheel

A wheel is a circular component that is intended to rotate on an axle Bearing (mechanical), bearing. The wheel is one of the key components of the wheel and axle which is one of the Simple machine, six simple machines. Wheels, in conjunction wi ...

. His 'Monobloc' pump could also create a partial vacuum

A vacuum is a space devoid of matter. The word is derived from the Latin adjective ''vacuus'' for "vacant" or "void". An approximation to such vacuum is a region with a gaseous pressure much less than atmospheric pressure. Physicists often dis ...

.

Mechanical clocks

The Ottoman engineer Taqi al-Din invented a mechanical

The Ottoman engineer Taqi al-Din invented a mechanical astronomical clock

An astronomical clock, horologium, or orloj is a clock with special mechanisms and dials to display astronomical information, such as the relative positions of the Sun, Moon, zodiacal constellations, and sometimes major planets.

Definition

...

, capable of striking an alarm

An alarm device is a mechanism that gives an audible, visual or other kind of alarm signal to alert someone to a problem or condition that requires urgent attention.

Alphabetical musical instruments

Etymology

The word ''alarm'' comes from th ...

at any time specified by the user. He described the clock in his book, ''The Brightest Stars for the Construction of Mechanical Clocks'' (''Al-Kawākib al-durriyya fī wadh' al-bankāmat al-dawriyya''), published in 1559. Similarly to earlier 15th-century European alarm clocks, his clock was capable of sounding at a specified time, achieved by placing a peg on the dial wheel. At the requested time, the peg activated a ringing device. This clock had three dials which showed the hours, degrees and minutes.

He later designed an observational clock to aid in observations at his Constantinople Observatory of Taqi ad-Din (1577–1580). In his treatise ''In The Nabk Tree of the Extremity of Thoughts'', he wrote: "We constructed a mechanical clock with three dials which show the hours, the minutes, and the seconds. We divided each minute into five seconds". This was an important innovation in 16th-century practical astronomy, as at the start of the century clocks were not accurate enough to be used for astronomical purposes.

An example of a watch which measured time in minutes was created by an Ottoman watchmaker, Meshur Sheyh Dede, in 1702.

Steam power

In 1551, Taqi al-Din described an early example of an impulsesteam turbine

A steam turbine is a machine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work on a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Charles Parsons in 1884. Fabrication of a modern steam turbin ...

and also noted practical applications for a steam turbine as a prime mover for rotating a spit, predating Giovanni Branca

Giovanni Branca (22 April 1571 – 24 January 1645) was an Italian engineer and architect, chiefly remembered today for what some commentators have taken to be an early steam turbine.

Life

Branca was born on 22 April 1571 in Sant'Angelo in Liz ...

's later impulse steam turbine from 1629. Taqi al-Din described such a device in his book, ''Al-Turuq al-saniyya fi al-alat al-ruhaniyya'' (''The Sublime Methods of Spiritual Machines''), completed in 1551 AD (959 AH).Ahmad Y Hassan

Ahmad Yousef Al-Hassan ( ar, links=no, أحمد يوسف الحسن) (June 25, 1925 – April 28, 2012) was a Palestinian/Syrian/Canadian historian of Arabic and Islamic science and technology, educated in Jerusalem, Cairo, and London with a PhD i ...

(1976), ''Taqi al-Din and Arabic Mechanical Engineering'', p. 34-35. Institute for the History of Arabic Science, University of Aleppo

University of Aleppo ( ar, جَامِعَة حَلَب, Jāmiʿat Ḥalab, also called Aleppo University) is a public university located in Aleppo, Syria. It is the second largest university in Syria after the University of Damascus.

During 2005 ...

. (See ''Steam jack

A roasting jack is a machine which rotates meat roasting on a spit. It can also be called a spit jack, a spit engine or a turnspit, although this name can also refer to a human turning the spit, or a turnspit dog. Cooking meat on a spit dates b ...

''.)

Ottoman Egypt

The Eyalet of Egypt (, ) operated as an administrative division of the Ottoman Empire from 1517 to 1867. It originated as a result of the conquest of Mamluk Egypt by the Ottomans in 1517, following the Ottoman–Mamluk War (1516–17) and the a ...

ian industries began moving towards steam power

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be trans ...

in the early 19th century. In Egypt under Muhammad Ali

The history of Egypt under the Muhammad Ali dynasty (1805–1953) spanned the later period of Ottoman Egypt, the Khedivate of Egypt under British occupation, and the nominally independent Sultanate of Egypt and Kingdom of Egypt, ending with the ...

, industrial manufacturing was initially driven by machinery that relied on traditional energy sources, such as animal power

A working animal is an animal, usually domesticated, that is kept by humans and trained to perform tasks instead of being slaughtered to harvest animal products. Some are used for their physical strength (e.g. oxen and draft horses) or for tr ...

, water wheel

A water wheel is a machine for converting the energy of flowing or falling water into useful forms of power, often in a watermill. A water wheel consists of a wheel (usually constructed from wood or metal), with a number of blades or buckets ...

s, and windmill

A windmill is a structure that converts wind power into rotational energy using vanes called windmill sail, sails or blades, specifically to mill (grinding), mill grain (gristmills), but the term is also extended to windpumps, wind turbines, and ...

s, which were also the principle energy sources in Western Europe up until around 1870. Under Muhammad Ali of Egypt

Muhammad Ali Pasha al-Mas'ud ibn Agha, also known as Muhammad Ali of Egypt and the Sudan ( sq, Mehmet Ali Pasha, ar, محمد علي باشا, ; ota, محمد علی پاشا المسعود بن آغا; ; 4 March 1769 – 2 August 1849), was ...

in the early 19th century, steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be trans ...

s were introduced to Egyptian industrial manufacturing, with boiler

A boiler is a closed vessel in which fluid (generally water) is heated. The fluid does not necessarily boil. The heated or vaporized fluid exits the boiler for use in various processes or heating applications, including water heating, central h ...

s manufactured and installed in industries such as ironworks

An ironworks or iron works is an industrial plant where iron is smelted and where heavy iron and steel products are made. The term is both singular and plural, i.e. the singular of ''ironworks'' is ''ironworks''.

Ironworks succeeded bloomeri ...

, textile manufacturing, paper mill

A paper mill is a factory devoted to making paper from vegetable fibres such as wood pulp, old rags, and other ingredients. Prior to the invention and adoption of the Fourdrinier machine and other types of paper machine that use an endless belt, ...

s, and hulling

Husk (or hull) in botany is the outer shell or coating of a seed. In the United States, the term husk often refers to the leafy outer covering of an ear of maize (corn) as it grows on the plant. Literally, a husk or hull includes the protect ...

mills. While there was a lack of coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when dea ...

deposits in Egypt, prospectors searched for coal deposits there, and imported coal from overseas, at similar prices to what imported coal cost in France, until the 1830s, when Egypt gained access to coal sources in Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus li ...

, which had a yearly coal output of 4,000 tons. Compared to Western Europe, Egypt also had superior agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people to ...

and an efficient transport

Transport (in British English), or transportation (in American English), is the intentional movement of humans, animals, and goods from one location to another. Modes of transport include air, land (rail and road), water, cable, pipeline, an ...

network through the Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin language, Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered ...

. Economic historian Jean Batou argues that the necessary economic conditions for rapid industrialization

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econo ...

existed in Egypt during the 1820s–1830s, as well as for the adoption of oil

An oil is any nonpolar chemical substance that is composed primarily of hydrocarbons and is hydrophobic (does not mix with water) & lipophilic (mixes with other oils). Oils are usually flammable and surface active. Most oils are unsaturated ...

as a potential energy source for its steam engines later in the 19th century.

Military

The Ottoman Empire in the 16th century was known for their military power throughout southern Europe and the Middle East. The

The Ottoman Empire in the 16th century was known for their military power throughout southern Europe and the Middle East. The Harquebus

An arquebus ( ) is a form of long gun that appeared in Europe and the Ottoman Empire during the 15th century. An infantryman armed with an arquebus is called an arquebusier.

Although the term ''arquebus'', derived from the Dutch word ''Haakbus ...

, "also spelled arquebus, also called hackbut

An arquebus ( ) is a form of long gun that appeared in Europe and the Ottoman Empire during the 15th century. An infantryman armed with an arquebus is called an arquebusier.

Although the term ''arquebus'', derived from the Dutch word ''Haakbus ...

, first gun fired from the shoulder, a smoothbore matchlock with a stock resembling that of a rifle". It was also first appeared in the Ottoman Empire and was referred to as a handgun. The German Gun was obtained by the German word "hooked gun".

Ottoman artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

included a number of cannons

A cannon is a large-caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder during ...

, most of which were designed by Turkish engineers, in addition to a cannon designed by Hungarian engineer Orban Orban, also known as Urban ( hu, Orbán; died 1453), was an iron founder and engineer from Brassó, Transylvania, in the Kingdom of Hungary (today Brașov, Romania), who cast large-calibre artillery for the Ottoman siege of Constantinople in 1453.

...

, who had earlier offered his services to the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

emperor Constantine XI

Constantine XI Dragases Palaiologos or Dragaš Palaeologus ( el, Κωνσταντῖνος Δραγάσης Παλαιολόγος, ''Kōnstantînos Dragásēs Palaiológos''; 8 February 1405 – 29 May 1453) was the last Roman (Byzantine) e ...

., pp.79-80, pp. 13, 22 Orban's price for the cannons was high, so the Byzantine emperor

This is a list of the Byzantine emperors from the foundation of Constantinople in 330 AD, which marks the conventional start of the Eastern Roman Empire, to its fall to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 AD. Only the emperors who were recognized as le ...

of Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

was not able to afford it. Mehmed II

Mehmed II ( ota, محمد ثانى, translit=Meḥmed-i s̱ānī; tr, II. Mehmed, ; 30 March 14323 May 1481), commonly known as Mehmed the Conqueror ( ota, ابو الفتح, Ebū'l-fetḥ, lit=the Father of Conquest, links=no; tr, Fâtih Su ...

was determined to win the battle, and used cannons to blast through Constantinople's huge wall during the siege of Constantinople

The following is a list of sieges of Constantinople, a historic city located in an area which is today part of Istanbul, Turkey. The city was built on the land that links Europe to Asia through Bosporus and connects the Sea of Marmara and the ...

on 6 April 1453.

The Dardanelles Gun

The Basillica or Great Turkish Bombard ( tr, Şahi topu or simply ''Şahi'') is a 15th-century siege cannon, specifically a super-sized bombard, which saw action in the 1807 Dardanelles operation.Schmidtchen (1977b), p. 228 It was built in 1 ...

was designed and cast in bronze in 1464 by Munir Ali, weighed nearly a ton, and had a length of 5.18m. The large gun operated a 635mm caliber rounds and was able to fire marble boulders. To put things into perspective, this round was nearly 6 times larger than the main British tank caliber gun at 120mm. The Dardanelles Gun was still present for duty more than 340 years later in 1807, when a Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

force appeared and commenced the Dardanelles Operation. Turkish forces loaded the ancient relics with propellant

A propellant (or propellent) is a mass that is expelled or expanded in such a way as to create a thrust or other motive force in accordance with Newton's third law of motion, and "propel" a vehicle, projectile, or fluid payload. In vehicles, the e ...

and projectile

A projectile is an object that is propelled by the application of an external force and then moves freely under the influence of gravity and air resistance. Although any objects in motion through space are projectiles, they are commonly found in ...

s, then fired them at the British ships. The British squadron suffered 28 casualties from this bombardment.Schmidtchen, Volker (1977b), "Riesengeschütze des 15. Jahrhunderts. Technische Höchstleistungen ihrer Zeit", ''Technikgeschichte'' 44 (3): 213–237 (226–228)

The musket

A musket is a muzzle-loaded long gun that appeared as a smoothbore weapon in the early 16th century, at first as a heavier variant of the arquebus, capable of penetrating plate armour. By the mid-16th century, this type of musket gradually d ...

appeared in the Ottoman Empire by 1465. Damascus steel

Damascus steel was the forged steel of the blades of swords smithed in the Near East from ingots of Wootz steel either imported from Southern India or made in production centres in Sri Lanka, or Khorasan, Iran. These swords are characterize ...

was used in the production of firearms such as the musket from the 16th century. A musket is a long gun which materialized in the Ottoman Empire by 1465. These were large hand-held guns made out of steel and were capable of penetrating heavy armor; however, these guns by the mid-16th century disappeared because heavy armor declined. There were many more versions of the musket which eventually became known as the rifle. In the 15th century the Ottomans had perfected the musket by creating a gun that used a lever and spring. These were much more easy to use during combat. Eventually the rifle as we know today ended the era of the musket

Turkish arquebuses may have reached China before Portuguese ones. In 1598, Chinese writer Zhao Shizhen described Turkish muskets as being superior to European muskets.

The Chinese military book ''Wu Pei Chih

The ''Wubei Zhi'' (; ''Treatise on Armament Technology'' or ''Records of Armaments and Military Provisions''), also commonly known by its Japanese translated name Bubishi, is a military book in Chinese history. It was compiled in 1621 by Mao Yu ...

'' (1621) describes a Turkish musket that, rather than using a matchlock mechanism, instead uses a rack-and-pinion

A rack and pinion is a type of linear actuator that comprises a circular gear (the ''pinion'') engaging a linear gear (the ''rack''). Together, they convert rotational motion into linear motion. Rotating the pinion causes the rack to be driven i ...

mechanism. On release of the trigger, the two racks return automatically to their original positions. This was the first time a rack-and-pinion mechanism is known to have been used in a firearm, with no evidence of its use in any European or East-Asian firearms at the time.

The Ottoman Empire military was also tactically proficient in the use of small arms weapons such as rifle

A rifle is a long-barreled firearm designed for accurate shooting, with a barrel that has a helical pattern of grooves ( rifling) cut into the bore wall. In keeping with their focus on accuracy, rifles are typically designed to be held with ...

s and handgun

A handgun is a short- barrelled gun, typically a firearm, that is designed to be usable with only one hand. It is distinguished from a long gun (i.e. rifle, shotgun or machine gun, etc.), which needs to be held by both hands and also braced ...

s. Like many other great powers, the Ottomans issued the M1903 Mauser bolt-action

Bolt-action is a type of manual firearm action that is operated by ''directly'' manipulating the bolt via a bolt handle, which is most commonly placed on the right-hand side of the weapon (as most users are right-handed).

Most bolt-action ...

rifle to its most elite front-line infantry and cavalry soldiers, also known as Janissaries

A Janissary ( ota, یڭیچری, yeŋiçeri, , ) was a member of the elite infantry units that formed the Ottoman Sultan's household troops and the first modern standing army in Europe. The corps was most likely established under sultan Orhan ( ...

. With a five-round box magazine and maximum effective range of 600 meters, the Ottomans were able to effectively engage enemy soldiers when they were unable to utilize field artillery cannons. Second line units, or Jardamas, were primarily issued obsolete single shot weapons such as the M1887 rife, M1874 rifle or older modeled revolvers. Officers in the Ottoman Empire Army

The military of the Ottoman Empire ( tr, Osmanlı İmparatorluğu'nun silahlı kuvvetleri) was the armed forces of the Ottoman Empire.

Army

The military of the Ottoman Empire can be divided in five main periods. The foundation era covers th ...

were authorized to purchase their own personal handguns from the various number of European craftsmen.

See also

*Ali Qushji

Ala al-Dīn Ali ibn Muhammed (1403 – 16 December 1474), known as Ali Qushji (Ottoman Turkish : علی قوشچی, ''kuşçu'' – falconer in Turkish; Latin: ''Ali Kushgii'') was a Timurid theologian, jurist, astronomer, mathematician a ...

* Hezarfen Ahmet Celebi, Ottoman aviator

* Lagari Hasan Celebi, Ottoman aviator

* List of inventions in the medieval Islamic world

The following is a list of inventions made in the medieval Islamic world, especially during the Islamic Golden Age,George Saliba (1994), ''A History of Arabic Astronomy: Planetary Theories During the Golden Age of Islam'', pp. 245, 250, 256–57 ...

* Piri Reis

Ahmet Muhiddin Piri ( 1465 – 1553), better known as Piri Reis ( tr, Pîrî Reis (military rank), Reis or ''Hacı Ahmet Muhittin Pîrî Bey''), was a Navigation, navigator, Geography in medieval Islam, geographer and Cartography, cartographer. ...

* Science in the medieval Islamic world

Science in the medieval Islamic world was the science developed and practised during the Islamic Golden Age under the Umayyads of Córdoba, the Abbadids of Seville, the Samanids, the Ziyarids, the Buyids in Persia, the Abbasid Caliphate and ...

* Taqi ad-Din Muhammad ibn Ma'ruf

Taqi ad-Din Muhammad ibn Ma'ruf ash-Shami al-Asadi ( ar, تقي الدين محمد بن معروف الشامي; ota, تقي الدين محمد بن معروف الشامي السعدي; tr, Takiyüddin 1526–1585) was an Ottoman poly ...

* Timeline of science and engineering in the Islamic world

This timeline of science and engineering in the Muslim world covers the time period from the eighth century AD to the introduction of History of Europe, European science to the Muslim world in the nineteenth century. All year dates are given ...

Notes

References

* ''History of Astronomy Literature during the Ottoman Period'' byEkmeleddin İhsanoğlu

Ekmeleddin Mehmet İhsanoğlu (; born 26 December 1943) is a Turkish academic, diplomat and politician who was Secretary-General of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) from 2004 to 2014. He is also an author and editor of academic jour ...

*

* .

*"Weapons of the Ottoman Army - The Ottoman Empire , NZHistory, New Zealand history online". ''nzhistory.govt.nz''. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

*''5 Weapons Used by the Ottomans'', retrieved 22 November 2019

*"Ottoman military band", ''Wikipedia'', 30 September 2019, retrieved 22 November 2019

*"Mehter-The Oldest Band in the World". ''web.archive.org''. 1 January 2014. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

Further reading

* ''Science among the Ottomans: The Cultural Creation and Exchange of Knowledge'' by Miri Shefer-Mossensohn, 2015, University of Texas Press {{DEFAULTSORT:Science And Technology in the Ottoman EmpireOttoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

Technology in the Middle Ages

Science in the Middle Ages