SY Aurora's Drift on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The drift of the Antarctic exploration vessel SY ''Aurora'' was an ordeal which lasted 312 days, affecting the

The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition comprised two parties. The first, under

The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition comprised two parties. The first, under  Of the Ross Sea party that eventually sailed from Australia in December 1914, only Mackintosh,

Of the Ross Sea party that eventually sailed from Australia in December 1914, only Mackintosh,

The only known safe winter anchorage in McMurdo Sound was Scott's original

The only known safe winter anchorage in McMurdo Sound was Scott's original

By 8 May a continuous southerly gale had driven the ship northwards, still locked in the ice, out of McMurdo Sound and into the open Ross Sea. In his diary for 9 May Stenhouse summarised ''Aurora''s position: "...fast in the pack and drifting God knows where ..We are all in good health ..we have good spirits and we will get through." He recognised that this was the end of any hope of wintering the ship in McMurdo Sound, and expressed concern for the men at Cape Evans: "It is a dismal prospect for them ..we have the remaining Burberrys, clothing etc for next year's sledging still on board."Shackleton, pp. 309–13 During the next two days the winds reached a force that made it impossible for the men to work on deck,Haddelsey, pp. 53–57 but on 12 May the weather had moderated sufficiently for a temporary wireless aerial to be rigged, and Hooke began trying to contact the men ashore. His

By 8 May a continuous southerly gale had driven the ship northwards, still locked in the ice, out of McMurdo Sound and into the open Ross Sea. In his diary for 9 May Stenhouse summarised ''Aurora''s position: "...fast in the pack and drifting God knows where ..We are all in good health ..we have good spirits and we will get through." He recognised that this was the end of any hope of wintering the ship in McMurdo Sound, and expressed concern for the men at Cape Evans: "It is a dismal prospect for them ..we have the remaining Burberrys, clothing etc for next year's sledging still on board."Shackleton, pp. 309–13 During the next two days the winds reached a force that made it impossible for the men to work on deck,Haddelsey, pp. 53–57 but on 12 May the weather had moderated sufficiently for a temporary wireless aerial to be rigged, and Hooke began trying to contact the men ashore. His

With the Antarctic summer waning, Stenhouse had to consider the possibility that ''Aurora'' might be trapped for another year, and after reviewing fuel and stores he ordered the capture of more seals and penguins. This proved difficult, as the soft state of the ice made travel away from the ship hazardous.Tyler-Lewis, pp. 207–10 As the ice encasing the ship melted, the timber seams opened and were admitting around three to four feet (about a metre) of water daily, requiring regular work with the pumps. On 12 February, while the crew were busy with this activity, the ice around the ship finally began to break away. Within minutes the whole floe had splintered into fragments, a pool of water opened up, and ''Aurora'' was floating free.Haddelsey, pp. 65–68 Next morning Stenhouse ordered the setting of sails, but on 15 February the ship was stopped by accumulated ice and remained, unable to move, for a further two weeks. Stenhouse was reluctant to use the engines because coal supplies were low, but on 1 March he decided he had no choice; he ordered steam to be raised, and next day the ship edged forward under engine power. After a series of stops and starts, on 6 March the edge of the ice was sighted from the crow's nest. On 14 March ''Aurora'' finally cleared the pack, after a drift of 312 days covering . Stenhouse recorded the ship's position on reaching the open sea as

With the Antarctic summer waning, Stenhouse had to consider the possibility that ''Aurora'' might be trapped for another year, and after reviewing fuel and stores he ordered the capture of more seals and penguins. This proved difficult, as the soft state of the ice made travel away from the ship hazardous.Tyler-Lewis, pp. 207–10 As the ice encasing the ship melted, the timber seams opened and were admitting around three to four feet (about a metre) of water daily, requiring regular work with the pumps. On 12 February, while the crew were busy with this activity, the ice around the ship finally began to break away. Within minutes the whole floe had splintered into fragments, a pool of water opened up, and ''Aurora'' was floating free.Haddelsey, pp. 65–68 Next morning Stenhouse ordered the setting of sails, but on 15 February the ship was stopped by accumulated ice and remained, unable to move, for a further two weeks. Stenhouse was reluctant to use the engines because coal supplies were low, but on 1 March he decided he had no choice; he ordered steam to be raised, and next day the ship edged forward under engine power. After a series of stops and starts, on 6 March the edge of the ice was sighted from the crow's nest. On 14 March ''Aurora'' finally cleared the pack, after a drift of 312 days covering . Stenhouse recorded the ship's position on reaching the open sea as

The delays in breaking free from the pack had ended Stenhouse's hopes of bringing rapid relief to Cape Evans. His priority now was to reach New Zealand and return to the Antarctic the following spring. During the final frustrating weeks in the pack, Hooke had been working on the wireless apparatus and had started transmitting again. He and the rest of the crew were unaware that the wireless station at Macquarie Island, the closest to their drift, had recently been closed by the Australian government as an economy measure. On 23 March, using a specially-rigged quadruple aerial, Hookes transmitted a message which, in freak atmospheric conditions, reached Bluff Station, New Zealand. The next day his signals were received in Hobart, Tasmania, and during the following days he reported the details of Aurora's position, its general situation, and the plight of the stranded party. These messages, and the freak conditions which made transmission possible over a much greater distance than the equipment's normal range, were reported throughout the world.

''Aurora''s passage from the ice towards safety proved slow and perilous. Coal supplies had to be conserved, allowing only limited use of the engines, and the improvised emergency rudder made steering difficult; the ship wallowed helplessly at times, in danger of foundering.Haddelsey, pp. 69–70 Even after making contact with the outside world, Stenhouse was initially reluctant to seek direct assistance, fearful that a salvage claim might create further embarrassment for the expedition. He was obliged to request help when, as ''Aurora'' neared New Zealand in stormy weather on 31 March, it was in danger of being driven on the rocks. Two days later the tug ''Dunedin'' reached the ship and a towline was secured. On the following morning, 3 April 1916, ''Aurora'' was brought into the harbour at Port Chalmers.

The delays in breaking free from the pack had ended Stenhouse's hopes of bringing rapid relief to Cape Evans. His priority now was to reach New Zealand and return to the Antarctic the following spring. During the final frustrating weeks in the pack, Hooke had been working on the wireless apparatus and had started transmitting again. He and the rest of the crew were unaware that the wireless station at Macquarie Island, the closest to their drift, had recently been closed by the Australian government as an economy measure. On 23 March, using a specially-rigged quadruple aerial, Hookes transmitted a message which, in freak atmospheric conditions, reached Bluff Station, New Zealand. The next day his signals were received in Hobart, Tasmania, and during the following days he reported the details of Aurora's position, its general situation, and the plight of the stranded party. These messages, and the freak conditions which made transmission possible over a much greater distance than the equipment's normal range, were reported throughout the world.

''Aurora''s passage from the ice towards safety proved slow and perilous. Coal supplies had to be conserved, allowing only limited use of the engines, and the improvised emergency rudder made steering difficult; the ship wallowed helplessly at times, in danger of foundering.Haddelsey, pp. 69–70 Even after making contact with the outside world, Stenhouse was initially reluctant to seek direct assistance, fearful that a salvage claim might create further embarrassment for the expedition. He was obliged to request help when, as ''Aurora'' neared New Zealand in stormy weather on 31 March, it was in danger of being driven on the rocks. Two days later the tug ''Dunedin'' reached the ship and a towline was secured. On the following morning, 3 April 1916, ''Aurora'' was brought into the harbour at Port Chalmers.

On his arrival in New Zealand Stenhouse learned that nothing had been heard from Shackleton and the Weddell Sea party since their departure from South Georgia in December 1914; it seemed probable that both arms of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition were requiring relief.Tyler-Lewis, pp. 214–15 Stenhouse was informed by the expedition offices in London that funds had long since been exhausted and that money for the necessary work on ''Aurora'' would have to be found elsewhere. It was also evident that in the minds of the authorities the relief of Shackleton's party should have priority over the men marooned at Cape Evans.

Inaction continued until Shackleton's sudden reappearance in the

On his arrival in New Zealand Stenhouse learned that nothing had been heard from Shackleton and the Weddell Sea party since their departure from South Georgia in December 1914; it seemed probable that both arms of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition were requiring relief.Tyler-Lewis, pp. 214–15 Stenhouse was informed by the expedition offices in London that funds had long since been exhausted and that money for the necessary work on ''Aurora'' would have to be found elsewhere. It was also evident that in the minds of the authorities the relief of Shackleton's party should have priority over the men marooned at Cape Evans.

Inaction continued until Shackleton's sudden reappearance in the

Ross Sea party

The Ross Sea party was a component of Sir Ernest Shackleton's 1914–1917 Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition. Its task was to lay a series of supply depots across the Great Ice Barrier from the Ross Sea to the Beardmore Glacier, along the polar ...

of Sir Ernest Shackleton

Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton (15 February 1874 – 5 January 1922) was an Anglo-Irish Antarctic explorer who led three British expeditions to the Antarctic. He was one of the principal figures of the period known as the Heroic Age of ...

's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition

The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914–1917 is considered to be the last major expedition of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. Conceived by Sir Ernest Shackleton, the expedition was an attempt to make the first land crossing ...

, 1914–1917. It began when the ship broke loose from its anchorage in McMurdo Sound

McMurdo Sound is a sound in Antarctica. It is the southernmost navigable body of water in the world, and is about from the South Pole.

Captain James Clark Ross discovered the sound in February 1841, and named it after Lt. Archibald McMurdo ...

in May 1915, during a gale. Caught in heavy pack ice

Drift ice, also called brash ice, is sea ice that is not attached to the shoreline or any other fixed object (shoals, grounded icebergs, etc.).Leppäranta, M. 2011. The Drift of Sea Ice. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. Unlike fast ice, which is "fasten ...

and unable to manoeuvre, ''Aurora'', with eighteen men aboard, was carried into the open waters of the Ross Sea

The Ross Sea is a deep bay of the Southern Ocean in Antarctica, between Victoria Land and Marie Byrd Land and within the Ross Embayment, and is the southernmost sea on Earth. It derives its name from the British explorer James Clark Ross who vi ...

and Southern Ocean

The Southern Ocean, also known as the Antarctic Ocean, comprises the southernmost waters of the World Ocean, generally taken to be south of 60° S latitude and encircling Antarctica. With a size of , it is regarded as the second-small ...

, leaving ten men stranded ashore with meagre provisions.

''Aurora'', a 40-year-old former Arctic whaler

A whaler or whaling ship is a specialized vessel, designed or adapted for whaling: the catching or processing of whales.

Terminology

The term ''whaler'' is mostly historic. A handful of nations continue with industrial whaling, and one, Japa ...

registered as a steam yacht

A steam yacht is a class of luxury or commercial yacht with primary or secondary steam propulsion in addition to the sails usually carried by yachts.

Origin of the name

The English steamboat entrepreneur George Dodd (1783–1827) used the term ...

, had brought the Ross Sea party

The Ross Sea party was a component of Sir Ernest Shackleton's 1914–1917 Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition. Its task was to lay a series of supply depots across the Great Ice Barrier from the Ross Sea to the Beardmore Glacier, along the polar ...

to Cape Evans

Cape Evans is a rocky cape on the west side of Ross Island, Antarctica, forming the north side of the entrance to Erebus Bay.

History

The cape was discovered by the British National Antarctic Expedition, 1901–04, under Robert Falcon Scott, ...

in McMurdo Sound in January 1915, to establish its base there in support of Shackleton's proposed transcontinental crossing. When ''Aurora''s captain Aeneas Mackintosh

Aeneas Lionel Acton Mackintosh (1 July 1879 – 8 May 1916) was a British Merchant Navy officer and Antarctic explorer, who commanded the Ross Sea party as part of Sir Ernest Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1914–1917. ...

took charge of activities ashore, first officer Joseph Stenhouse

Commander Joseph Russell Stenhouse, DSO, OBE, DSC, RD, RNR (1887–1941) was a Scottish-born seaman, Royal Navy Officer and Antarctic navigator, who commanded the expedition vessel during her 283-day drift in the ice while on service with t ...

assumed command of the ship. Stenhouse's inexperience may have contributed to the choice of an inappropriate winter's berth, although his options were restricted by the instructions of his superiors. After the ship was blown away it suffered severe damage in the ice, including the destruction of its rudder and the loss of its anchors; on several occasions its situation was such that Stenhouse considered abandonment. Efforts to make wireless

Wireless communication (or just wireless, when the context allows) is the transfer of information between two or more points without the use of an electrical conductor, optical fiber or other continuous guided medium for the transfer. The most ...

contact with Cape Evans and, later, with stations in New Zealand and Australia, were unavailing; the drift extended through the southern winter and spring to reach a position north of the Antarctic Circle

The Antarctic Circle is the most southerly of the five major circles of latitude that mark maps of Earth. The region south of this circle is known as the Antarctic, and the zone immediately to the north is called the Southern Temperate Zone. S ...

. In February 1916 the ice broke up, and a month later the ship was free. It was subsequently able to reach New Zealand for repairs and resupply, before returning to Antarctica to rescue the seven surviving members of the shore party.

The committee charged with supervision of the relief effort were critical of Shackleton's initial organisation of personnel and equipment for the Ross Sea expedition. Despite his role in saving the ship, after ''Aurora''s arrival in Port Chalmers

Port Chalmers is a town serving as the main port of the city of Dunedin, New Zealand. Port Chalmers lies ten kilometres inside Otago Harbour, some 15 kilometres northeast of Dunedin's city centre.

History

Early Māori settlement

The origi ...

, Stenhouse was removed from command by the organisers of the relief expedition, so the ship returned to McMurdo Sound under a new commander and with a substantially different crew. Stenhouse was later appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

(OBE) for his service aboard ''Aurora''.

Background

The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition comprised two parties. The first, under

The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition comprised two parties. The first, under Sir Ernest Shackleton

Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton (15 February 1874 – 5 January 1922) was an Anglo-Irish Antarctic explorer who led three British expeditions to the Antarctic. He was one of the principal figures of the period known as the Heroic Age of ...

, sailed to the Weddell Sea

The Weddell Sea is part of the Southern Ocean and contains the Weddell Gyre. Its land boundaries are defined by the bay formed from the coasts of Coats Land and the Antarctic Peninsula. The easternmost point is Cape Norvegia at Princess Martha ...

in ''Endurance'', intending to establish a base there from which a group would march across the continent via the South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole, Terrestrial South Pole or 90th Parallel South, is one of the two points where Earth's axis of rotation intersects its surface. It is the southernmost point on Earth and lies antipod ...

to McMurdo Sound

McMurdo Sound is a sound in Antarctica. It is the southernmost navigable body of water in the world, and is about from the South Pole.

Captain James Clark Ross discovered the sound in February 1841, and named it after Lt. Archibald McMurdo ...

on the Ross Sea

The Ross Sea is a deep bay of the Southern Ocean in Antarctica, between Victoria Land and Marie Byrd Land and within the Ross Embayment, and is the southernmost sea on Earth. It derives its name from the British explorer James Clark Ross who vi ...

side. A second party under Aeneas Mackintosh

Aeneas Lionel Acton Mackintosh (1 July 1879 – 8 May 1916) was a British Merchant Navy officer and Antarctic explorer, who commanded the Ross Sea party as part of Sir Ernest Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1914–1917. ...

in ''Aurora'' was landed at a Ross Sea base, with the task of laying supply depots along the expected route of the latter stages of Shackleton's march, a mission which Shackleton thought straightforward. Shackleton devoted little time to the details of the Ross Sea operation; thus, on arriving in Australia to take up his appointment, Mackintosh found himself faced with an unseaworthy ship and no funds to rectify the situation. ''Aurora'', though strongly built, was 40 years old and had recently returned from Douglas Mawson

Sir Douglas Mawson OBE FRS FAA (5 May 1882 – 14 October 1958) was an Australian geologist, Antarctic explorer, and academic. Along with Roald Amundsen, Robert Falcon Scott, and Sir Ernest Shackleton, he was a key expedition leader during ...

's Australasian Antarctic Expedition

The Australasian Antarctic Expedition was a 1911–1914 expedition headed by Douglas Mawson that explored the largely uncharted Antarctic coast due south of Australia. Mawson had been inspired to lead his own venture by his experiences on Ernest ...

in need of an extensive refit.Haddelsey, pp. 25–28 After the intervention of the eminent Australian polar scientist Edgeworth David

Sir Tannatt William Edgeworth David (28 January 1858 – 28 August 1934) was a Welsh Australian geologist and Antarctic explorer. A household name in his lifetime, David's most significant achievements were discovering the major Hunter ...

the Australian government provided money and dockyard facilities to make ''Aurora'' fit for further Antarctic service.

Of the Ross Sea party that eventually sailed from Australia in December 1914, only Mackintosh,

Of the Ross Sea party that eventually sailed from Australia in December 1914, only Mackintosh, Ernest Joyce

Ernest Edward Mills Joyce AM ( – 2 May 1940) was a Royal Naval seaman and explorer who participated in four Antarctic expeditions during the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, in the early 20th century. He served under both Robert Falcon ...

, who was in charge of the dogs, and the ship's boatswain

A boatswain ( , ), bo's'n, bos'n, or bosun, also known as a deck boss, or a qualified member of the deck department, is the most senior rate of the deck department and is responsible for the components of a ship's hull. The boatswain supervi ...

James "Scotty" Paton had significant experience with Antarctic conditions. Some of the party were last-minute additions: Adrian Donnelly, a railway engineer who had never been to sea, became ''Aurora''s second engineering officer,Tyler-Lewis, p. 50 while Lionel Hooke, the wireless operator, was an 18-year-old apprentice. ''Aurora''s chief officer was Joseph Stenhouse

Commander Joseph Russell Stenhouse, DSO, OBE, DSC, RD, RNR (1887–1941) was a Scottish-born seaman, Royal Navy Officer and Antarctic navigator, who commanded the expedition vessel during her 283-day drift in the ice while on service with t ...

, from the British India Steam Navigation Company

British India Steam Navigation Company ("BI") was formed in 1856 as the Calcutta and Burmah Steam Navigation Company.

History

The ''Calcutta and Burmah Steam Navigation Company'' had been formed out of Mackinnon, Mackenzie & Co, a trading partn ...

. Stenhouse, who was 26 years old when he joined the expedition, was in Australia recovering from a bout of depression when he heard of Shackleton's plans, and had travelled to London to secure the ''Aurora'' post. Although as a boy he had been inspired by the polar exploits of Fridtjof Nansen

Fridtjof Wedel-Jarlsberg Nansen (; 10 October 186113 May 1930) was a Norwegian polymath and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. He gained prominence at various points in his life as an explorer, scientist, diplomat, and humanitarian. He led the team t ...

, Scott and William Speirs Bruce

William Speirs Bruce (1 August 1867 – 28 October 1921) was a British Natural history, naturalist, polar region, polar scientist and Oceanography, oceanographer who organized and led the Scottish National Antarctic Expedition (SNAE, 1902–04) ...

, Stenhouse had no direct experience of Antarctic waters or ice conditions.

In McMurdo Sound

Winter anchorage

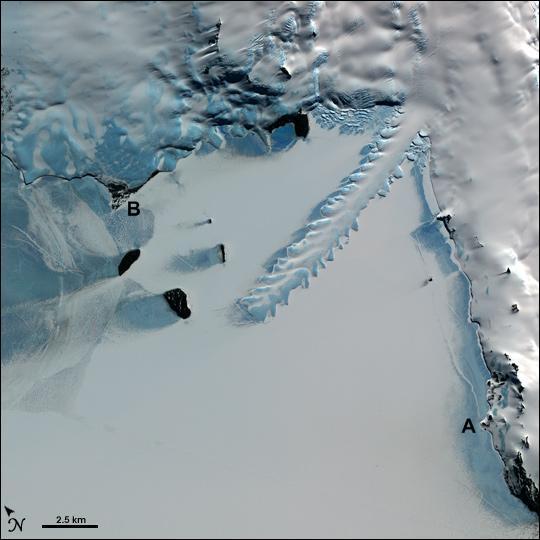

''Aurora'' arrived in McMurdo Sound in January 1915, late in the season due to its delayed departure from Australia. Because the party was three weeks behind schedule Mackintosh decided that the depot-laying work should begin at once,Tyler-Lewis, p. 66 and took charge of this himself. By 25 January he was leading one of the early sledging parties, leaving Stenhouse in command of the ship. In the few weeks before the sound froze over for the winter, Stenhouse had to supervise the landing of most of the equipment and stores, and find a safe winter berth for the ship; Mackintosh's departing instruction had been explicit that this was Stenhouse's paramount duty. The only known safe winter anchorage in McMurdo Sound was Scott's original

The only known safe winter anchorage in McMurdo Sound was Scott's original Discovery Expedition

The ''Discovery'' Expedition of 1901–1904, known officially as the British National Antarctic Expedition, was the first official British exploration of the Antarctic regions since the voyage of James Clark Ross sixty years earlier (1839–184 ...

headquarters from 1901–1903, at Hut Point

A hut is a small dwelling, which may be constructed of various local materials. Huts are a type of vernacular architecture because they are built of readily available materials such as wood, snow, ice, stone, grass, palm leaves, branches, hid ...

, south of the projection known as Glacier Tongue

An ice tongue is a long and narrow sheet of ice projecting out from the coastline. An ice tongue forms when a valley glacier moves very rapidly (relative to surrounding ice) out into the ocean or a lake. They can gain mass from water freezing at t ...

which divided the sound into two sectors. Scott's ship had been frozen in the ice for two years, and had needed two rescue ships and several explosive charges to release it. Shackleton was determined to avoid this, and had given Mackintosh instructions, relayed to Stenhouse, to winter ''Aurora'' north of the Tongue.Tyler-Lewis, pp. 114–16 No ship had previously wintered in the exposed northern section of the sound, and the wisdom of doing this was questioned by the experienced seamen Ernest Joyce and James Paton in their private journals. After the expedition was over, John King Davis

John King Davis (19 February 1884 – 8 May 1967) was an English-born Australian explorer and navigator notable for his work captaining exploration ships in Antarctic waters as well as for establishing meteorological stations on Macquar ...

, who was to lead the Ross Sea party relief mission, wrote that Shackleton's instruction should have been ignored and that Stenhouse should have taken ''Aurora'' to the safety of Hut Point, even at the risk of becoming frozen in.

Stenhouse first attempted to anchor the ship on the north side of Glacier Tongue itself. Disaster was only narrowly avoided when a change in the wind direction threatened to imprison ''Aurora'' between the Tongue and the advancing pack ice. With other options considered and rejected, Stenhouse finally decided to anchor at Cape Evans

Cape Evans is a rocky cape on the west side of Ross Island, Antarctica, forming the north side of the entrance to Erebus Bay.

History

The cape was discovered by the British National Antarctic Expedition, 1901–04, under Robert Falcon Scott, ...

, site of Captain Scott's 1911 Terra Nova headquarters, six nautical miles (11 km) north of Glacier Tongue. On 14 March, after numerous failed attempts, Stenhouse manoeuvred ''Aurora'' into position, stern-first towards the shore at Cape Evans, where two large anchors had been sunk and cemented into the ground. Cables, hawsers, and a heavy chain attached these to the ship's stern

The stern is the back or aft-most part of a ship or boat, technically defined as the area built up over the sternpost, extending upwards from the counter rail to the taffrail. The stern lies opposite the bow, the foremost part of a ship. Ori ...

. Two bower

Bower may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Catherine, or The Bower'', an unfinished Jane Austen novel

* A high-ranking card (usually a Jack) in certain card games:

** The Right and Left Bower (or Bauer), the two highest-ranking cards in the g ...

anchors were also dropped. By 14 March the ship was settling into the shore ice with, according to second officer Leslie Thomson, "enough hawsers and anchors to hold a battleship".

Blown away

The unsheltered Cape Evans anchorage exposed ''Aurora'' to the full harshness of the winter weather. By mid-April the ship resembled a "wrecked hulk", listing sharply to starboard and subject to violent shocks and tremors as the ice moved around it.Tyler-Lewis, pp. 125–27 When the weather permitted, attempts were made to rig the wireless aerials that would enable communication with the shore parties and later, it was hoped, with Australia and New Zealand.Haddelsey, pp. 48–49 The remaining sledging rations for the depots were put ashore, but much of the shore parties' personal supplies, fuel and equipment remained on board, as it was assumed that the ship would stay where it was throughout the winter. At about 9 p.m. on 6 May, during a fierce storm, the men aboard heard two "explosive reports" as the main hawsers parted from the anchors. The combined forces of the wind and the rapidly moving ice had torn ''Aurora'' from its berth and, encased in a large ice floe, the ship was adrift in the Sound. Stenhouse ordered that steam be raised in the hopes that, under engine power, ''Aurora'' might be able to work back to the shore when the gale abated, but the engines had been partly dismantled for winter repairs, and could not be started immediately. In any event the engine and single-screw propeller lacked the required power. Slowly, the ship drifted further from the shore; the noise of the storm meant that the scientific party ashore at Cape Evans hut heard nothing. It would be morning before they found the ship had gone.Haddelsey, pp. 51–52 Eighteen men were aboard when ''Aurora'' broke away, leaving ten marooned ashore. Four scientists were living in the Cape Evans hut; six members of the first depot-laying parties, including Mackintosh and Joyce, were stranded at Hut Point waiting an opportunity to cross the sea ice and return to Cape Evans.Drift

First phase

By 8 May a continuous southerly gale had driven the ship northwards, still locked in the ice, out of McMurdo Sound and into the open Ross Sea. In his diary for 9 May Stenhouse summarised ''Aurora''s position: "...fast in the pack and drifting God knows where ..We are all in good health ..we have good spirits and we will get through." He recognised that this was the end of any hope of wintering the ship in McMurdo Sound, and expressed concern for the men at Cape Evans: "It is a dismal prospect for them ..we have the remaining Burberrys, clothing etc for next year's sledging still on board."Shackleton, pp. 309–13 During the next two days the winds reached a force that made it impossible for the men to work on deck,Haddelsey, pp. 53–57 but on 12 May the weather had moderated sufficiently for a temporary wireless aerial to be rigged, and Hooke began trying to contact the men ashore. His

By 8 May a continuous southerly gale had driven the ship northwards, still locked in the ice, out of McMurdo Sound and into the open Ross Sea. In his diary for 9 May Stenhouse summarised ''Aurora''s position: "...fast in the pack and drifting God knows where ..We are all in good health ..we have good spirits and we will get through." He recognised that this was the end of any hope of wintering the ship in McMurdo Sound, and expressed concern for the men at Cape Evans: "It is a dismal prospect for them ..we have the remaining Burberrys, clothing etc for next year's sledging still on board."Shackleton, pp. 309–13 During the next two days the winds reached a force that made it impossible for the men to work on deck,Haddelsey, pp. 53–57 but on 12 May the weather had moderated sufficiently for a temporary wireless aerial to be rigged, and Hooke began trying to contact the men ashore. His Morse

Morse may refer to:

People

* Morse (surname)

* Morse Goodman (1917-1993), Anglican Bishop of Calgary, Canada

* Morse Robb (1902–1992), Canadian inventor and entrepreneur

Geography Antarctica

* Cape Morse, Wilkes Land

* Mount Morse, Churchi ...

messages failed to reach Cape Evans.Tyler-Lewis, p. 199 Although the transmitter's range was normally no more than , Hooke attempted to raise the radio station at Macquarie Island

Macquarie Island is an island in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, about halfway between New Zealand and Antarctica. Regionally part of Oceania and politically a part of Tasmania, Australia, since 1900, it became a Tasmanian State Reserve in 197 ...

, more than away, again without success.

On 14 May the broken remains of the two bower anchors, which were threatening to capsize the ship, were hauled in.Shackleton, pp. 310–11 During the following days the pack ice thickened, and in increasingly turbulent weather the boilers were closed down, since attempting to manoeuvre under power in these conditions would merely waste coal. Replenishing the ship's supply of fresh water was a further difficulty. A large iceberg was in view, but too far away in the prevailing weather conditions to be accessible, so to obtain drinking water the crew had to gather snow. Food was less of a problem; they were able to augment ''Aurora''s food supplies from the penguins and seals that gathered around the ship. To boost morale the crew were given a ration of rum to celebrate Empire Day

Commonwealth Day (formerly Empire Day) is the annual celebration of the Commonwealth of Nations, since 1977 often held on the second Monday in March. It is marked by an Anglican service in Westminster Abbey, normally attended by the monarch a ...

on 24 May.

On 25 May, as ''Aurora'' drifted towards the Victoria Land

Victoria Land is a region in eastern Antarctica which fronts the western side of the Ross Sea and the Ross Ice Shelf, extending southward from about 70°30'S to 78°00'S, and westward from the Ross Sea to the edge of the Antarctic Plateau. It ...

coast, Stenhouse described a scene "like a graveyard", with heavy blocks of ice twisted and standing up on end. ''Aurora'' was under constant danger as this ice shifted around her. Stenhouse ordered the crew to prepare sledging gear and supplies for a possible march for the shore should ''Aurora'' be caught and crushed, but that immediate danger passed.Shackleton, p. 312 Weeks of relative inactivity followed, while Stenhouse considered his options. If the ship remained icebound but stationary he would, if the sea ice allowed, send a sledge party back to Cape Evans with equipment and supplies. If the drift continued northward, as soon as the ship was free of the ice Stenhouse would head for New Zealand and, after repairs and resupply, would return to Cape Evans in September or October.

By 9 July the speed of the drift had increased, and there were signs of increasing pressure in the pack. On 21 July the ship was caught in a position that allowed the ice to squeeze it at both ends, a grip that smashed its rudder beyond repair. According to Hooke's diary: "All hands were ready to jump overboard onto the ice. It seemed certain that the ship must go." The next day Stenhouse prepared to abandon ship, but new movements in the ice eased the situation and eventually brought ''Aurora'' to a safer position.Haddelsey, pp. 58–59 Plans to abandon the vessel were cancelled; Hooke repaired his wireless aerials and resumed his attempts to contact Macquarie Island. On 6 August the sun made its first appearance since the start of the drift. ''Aurora'', still firmly held, was now north of Cape Evans, close to Cape Adare at the northern tip of Victoria Land, where the Ross Sea merges into the Southern Ocean.

Southern Ocean phase

When the ship passed Cape Adare, the direction of drift changed to north-westerly. On 10 August Stenhouse estimated that they were north-east of the Cape, and that their daily drift was averaging just over .Shackleton, pp. 320–21 A few days later Stenhouse recorded that the ship was "backing and filling", meaning that it was drifting back and forth without making progress. "However, we cannot grumble and must be patient", he wrote, adding that from thecrow's nest

A crow's nest is a structure in the upper part of the main mast of a ship or a structure that is used as a lookout point.

On ships, this position ensured the widest field of view for lookouts to spot approaching hazards, other ships, or land b ...

a distinct impression of open water could be seen. With the possibility that the edge of the pack was nearby, work on the construction of a jury

A jury is a sworn body of people (jurors) convened to hear evidence and render an impartiality, impartial verdict (a Question of fact, finding of fact on a question) officially submitted to them by a court, or to set a sentence (law), penalty o ...

rudder began. This first involved the removal of the wreckage of the smashed rudder, a task largely carried out by Engineer Donnelly.Haddelsey, p. 61 The jury rudder was constructed from makeshift materials, and by 26 August was ready for use as soon as ''Aurora'' cleared the ice. It would then be lowered over the stern and operated manually, "like a huge oar".Tyler-Lewis, p. 205

On 25 August Hooke began picking up occasional radio signals being exchanged between Macquarie Island and New Zealand.Shackleton, pp. 322–24 By the end of August open leads

Lead is a chemical element with symbol Pb and atomic number 82.

Lead or The Lead may also refer to:

Animal handling

* Leash, or lead

* Lead (leg), the leg that advances most in a quadruped's cantering or galloping stride

* Lead (tack), a lin ...

were beginning to appear, and sometimes it was possible to discern a sea-swell under the ship. Severe weather returned in September, when a hurricane-force wind destroyed the wireless aerial and temporarily halted Hooke's efforts. On 22 September, when ''Aurora'' was in sight of the uninhabited Balleny Islands

The Balleny Islands () are a series of uninhabited islands in the Southern Ocean extending from 66°15' to 67°35'S and 162°30' to 165°00'E. The group extends for about in a northwest-southeast direction. The islands are heavily glaciated an ...

, Stenhouse estimated that they had travelled over from Cape Evans, in what he called a "wonderful drift". He added that regular observations and records of the nature and direction of the ice had been maintained throughout: "It he drifthas not been in vain, and ..knowledge of the set and drift of the pack will be a valuable addition to the sum of human knowledge".

Aurora's circumstances changed little during the following months. Stenhouse worked hard to maintain morale, keeping the crew working whenever possible and organising leisure activities, including games of football and cricket on the ice.Haddelsey, pp. 62–64 On 21 November ''Aurora'' crossed the Antarctic Circle

The Antarctic Circle is the most southerly of the five major circles of latitude that mark maps of Earth. The region south of this circle is known as the Antarctic, and the zone immediately to the north is called the Southern Temperate Zone. S ...

, and it was at last evident that the ice around the ship was beginning to melt: "...one good hefty blizzard would cause a general break up", wrote Stenhouse. Christmas approached with the ice still holding firm; Stenhouse allowed the crew to prepare a feast, but noted in his journal: "I wish to God the blasted festivities were over ..we are hogging in to the best while the poor beggars at Cape Evans have little or nothing!" A few days later the New Year was celebrated with an improvised band leading choruses of "Rule, Britannia" and "God Save the King".

Release

In the early days of January 1916 the floe which held the ship began to crack in the sun. Stenhouse surmised that, after repairs in New Zealand: "if we could leave Lyttleton 'sic''at the end of February, with luck and a quick passage south we might make Hut Point before the general freezing of the Sound." Fast-moving ice could be seen a short distance from the ship, but ''Aurora'' remained held fast throughout January.Shackleton, p. 328 With the Antarctic summer waning, Stenhouse had to consider the possibility that ''Aurora'' might be trapped for another year, and after reviewing fuel and stores he ordered the capture of more seals and penguins. This proved difficult, as the soft state of the ice made travel away from the ship hazardous.Tyler-Lewis, pp. 207–10 As the ice encasing the ship melted, the timber seams opened and were admitting around three to four feet (about a metre) of water daily, requiring regular work with the pumps. On 12 February, while the crew were busy with this activity, the ice around the ship finally began to break away. Within minutes the whole floe had splintered into fragments, a pool of water opened up, and ''Aurora'' was floating free.Haddelsey, pp. 65–68 Next morning Stenhouse ordered the setting of sails, but on 15 February the ship was stopped by accumulated ice and remained, unable to move, for a further two weeks. Stenhouse was reluctant to use the engines because coal supplies were low, but on 1 March he decided he had no choice; he ordered steam to be raised, and next day the ship edged forward under engine power. After a series of stops and starts, on 6 March the edge of the ice was sighted from the crow's nest. On 14 March ''Aurora'' finally cleared the pack, after a drift of 312 days covering . Stenhouse recorded the ship's position on reaching the open sea as

With the Antarctic summer waning, Stenhouse had to consider the possibility that ''Aurora'' might be trapped for another year, and after reviewing fuel and stores he ordered the capture of more seals and penguins. This proved difficult, as the soft state of the ice made travel away from the ship hazardous.Tyler-Lewis, pp. 207–10 As the ice encasing the ship melted, the timber seams opened and were admitting around three to four feet (about a metre) of water daily, requiring regular work with the pumps. On 12 February, while the crew were busy with this activity, the ice around the ship finally began to break away. Within minutes the whole floe had splintered into fragments, a pool of water opened up, and ''Aurora'' was floating free.Haddelsey, pp. 65–68 Next morning Stenhouse ordered the setting of sails, but on 15 February the ship was stopped by accumulated ice and remained, unable to move, for a further two weeks. Stenhouse was reluctant to use the engines because coal supplies were low, but on 1 March he decided he had no choice; he ordered steam to be raised, and next day the ship edged forward under engine power. After a series of stops and starts, on 6 March the edge of the ice was sighted from the crow's nest. On 14 March ''Aurora'' finally cleared the pack, after a drift of 312 days covering . Stenhouse recorded the ship's position on reaching the open sea as latitude

In geography, latitude is a coordinate that specifies the north– south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from –90° at the south pole to 90° at the north pol ...

64°27'S, longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east–west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek letter l ...

157°32'E.

Return to civilization

The delays in breaking free from the pack had ended Stenhouse's hopes of bringing rapid relief to Cape Evans. His priority now was to reach New Zealand and return to the Antarctic the following spring. During the final frustrating weeks in the pack, Hooke had been working on the wireless apparatus and had started transmitting again. He and the rest of the crew were unaware that the wireless station at Macquarie Island, the closest to their drift, had recently been closed by the Australian government as an economy measure. On 23 March, using a specially-rigged quadruple aerial, Hookes transmitted a message which, in freak atmospheric conditions, reached Bluff Station, New Zealand. The next day his signals were received in Hobart, Tasmania, and during the following days he reported the details of Aurora's position, its general situation, and the plight of the stranded party. These messages, and the freak conditions which made transmission possible over a much greater distance than the equipment's normal range, were reported throughout the world.

''Aurora''s passage from the ice towards safety proved slow and perilous. Coal supplies had to be conserved, allowing only limited use of the engines, and the improvised emergency rudder made steering difficult; the ship wallowed helplessly at times, in danger of foundering.Haddelsey, pp. 69–70 Even after making contact with the outside world, Stenhouse was initially reluctant to seek direct assistance, fearful that a salvage claim might create further embarrassment for the expedition. He was obliged to request help when, as ''Aurora'' neared New Zealand in stormy weather on 31 March, it was in danger of being driven on the rocks. Two days later the tug ''Dunedin'' reached the ship and a towline was secured. On the following morning, 3 April 1916, ''Aurora'' was brought into the harbour at Port Chalmers.

The delays in breaking free from the pack had ended Stenhouse's hopes of bringing rapid relief to Cape Evans. His priority now was to reach New Zealand and return to the Antarctic the following spring. During the final frustrating weeks in the pack, Hooke had been working on the wireless apparatus and had started transmitting again. He and the rest of the crew were unaware that the wireless station at Macquarie Island, the closest to their drift, had recently been closed by the Australian government as an economy measure. On 23 March, using a specially-rigged quadruple aerial, Hookes transmitted a message which, in freak atmospheric conditions, reached Bluff Station, New Zealand. The next day his signals were received in Hobart, Tasmania, and during the following days he reported the details of Aurora's position, its general situation, and the plight of the stranded party. These messages, and the freak conditions which made transmission possible over a much greater distance than the equipment's normal range, were reported throughout the world.

''Aurora''s passage from the ice towards safety proved slow and perilous. Coal supplies had to be conserved, allowing only limited use of the engines, and the improvised emergency rudder made steering difficult; the ship wallowed helplessly at times, in danger of foundering.Haddelsey, pp. 69–70 Even after making contact with the outside world, Stenhouse was initially reluctant to seek direct assistance, fearful that a salvage claim might create further embarrassment for the expedition. He was obliged to request help when, as ''Aurora'' neared New Zealand in stormy weather on 31 March, it was in danger of being driven on the rocks. Two days later the tug ''Dunedin'' reached the ship and a towline was secured. On the following morning, 3 April 1916, ''Aurora'' was brought into the harbour at Port Chalmers.

Aftermath

On his arrival in New Zealand Stenhouse learned that nothing had been heard from Shackleton and the Weddell Sea party since their departure from South Georgia in December 1914; it seemed probable that both arms of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition were requiring relief.Tyler-Lewis, pp. 214–15 Stenhouse was informed by the expedition offices in London that funds had long since been exhausted and that money for the necessary work on ''Aurora'' would have to be found elsewhere. It was also evident that in the minds of the authorities the relief of Shackleton's party should have priority over the men marooned at Cape Evans.

Inaction continued until Shackleton's sudden reappearance in the

On his arrival in New Zealand Stenhouse learned that nothing had been heard from Shackleton and the Weddell Sea party since their departure from South Georgia in December 1914; it seemed probable that both arms of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition were requiring relief.Tyler-Lewis, pp. 214–15 Stenhouse was informed by the expedition offices in London that funds had long since been exhausted and that money for the necessary work on ''Aurora'' would have to be found elsewhere. It was also evident that in the minds of the authorities the relief of Shackleton's party should have priority over the men marooned at Cape Evans.

Inaction continued until Shackleton's sudden reappearance in the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubouzet ...

, at the beginning of June. The governments of Britain, Australia and New Zealand then agreed jointly to finance the Ross Sea relief expedition, and on 28 June work on ''Aurora'' began. Stenhouse still assumed that as ''de facto'' captain of the vessel he would lead the relief party, but the committee responsible for the refit were critical of Shackleton's initial organisation of the Ross Sea expedition. They wished to appoint their own commander for the relief expedition, and Stenhouse, as a Shackleton loyalist, was unacceptable to them.Haddelsey, pp. 77–80 They also questioned whether Stenhouse had sufficient experience for command, citing his unfortunate choice of a winter berth. After months of uncertainty Stenhouse learned, through a newspaper account on 4 October, that John King Davis had been appointed as ''Aurora''s new captain.Tyler-Lewis, pp. 227–30 Urged by Shackleton not to cooperate with this arrangement, Stenhouse turned down the post of chief officer and was discharged, along with Thompson, Donnelly and Hooke. Shackleton arrived in New Zealand too late to influence matters, beyond arranging his own appointment as a supernumerary officer on ''Aurora'' before its departure for Cape Evans on 20 December 1916.

On 10 January 1917, manned by an almost entirely new crew, ''Aurora'' arrived at Cape Evans and picked up the seven survivors of the Ross Sea shore party; Mackintosh, Victor Hayward

Victor George Hayward (23 October 1887 – 8 May 1916) was a London-born accounts clerk whose taste for adventure took him to Antarctica as a member of Sir Ernest Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1914–17. He had previo ...

and Arnold Spencer-Smith

Arnold Patrick Spencer-Smith (17 March 1883 – 9 March 1916) was an English clergyman and amateur photographer who joined Sir Ernest Shackleton's 1914–1917 Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition as chaplain on the Ross Sea party, who were ...

had all died. This was the vessel's final visit to Antarctic waters; on return to New Zealand it was sold by Shackleton to a coal carrier. ''Aurora'' left Newcastle, New South Wales

Newcastle ( ; Awabakal: ) is a metropolitan area and the second most populated city in the state of New South Wales, Australia. It includes the Newcastle and Lake Macquarie local government areas, and is the hub of the Greater Newcastle area, w ...

, on 20 June 1917 bound for Chile, and was never seen again, posted as missing by Lloyd's of London

Lloyd's of London, generally known simply as Lloyd's, is an insurance and reinsurance market located in London, England. Unlike most of its competitors in the industry, it is not an insurance company; rather, Lloyd's is a corporate body gov ...

on 2 January 1918. Among those dead were James Paton, who had acted as the ship's boatswain throughout the Ross Sea Party expedition and the drift, and on the subsequent relief mission. In 1920 King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Que ...

appointed Joseph Stenhouse an Officer of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

(OBE), for his service aboard ''Aurora''.Haddelsey, p. 129

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * PDF format * *External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Sy Aurora's Drift 1915 in Antarctica 1916 in Antarctica Exploration of Antarctica History of the Ross Dependency