SS George Washington on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

SS ''George Washington'' was an

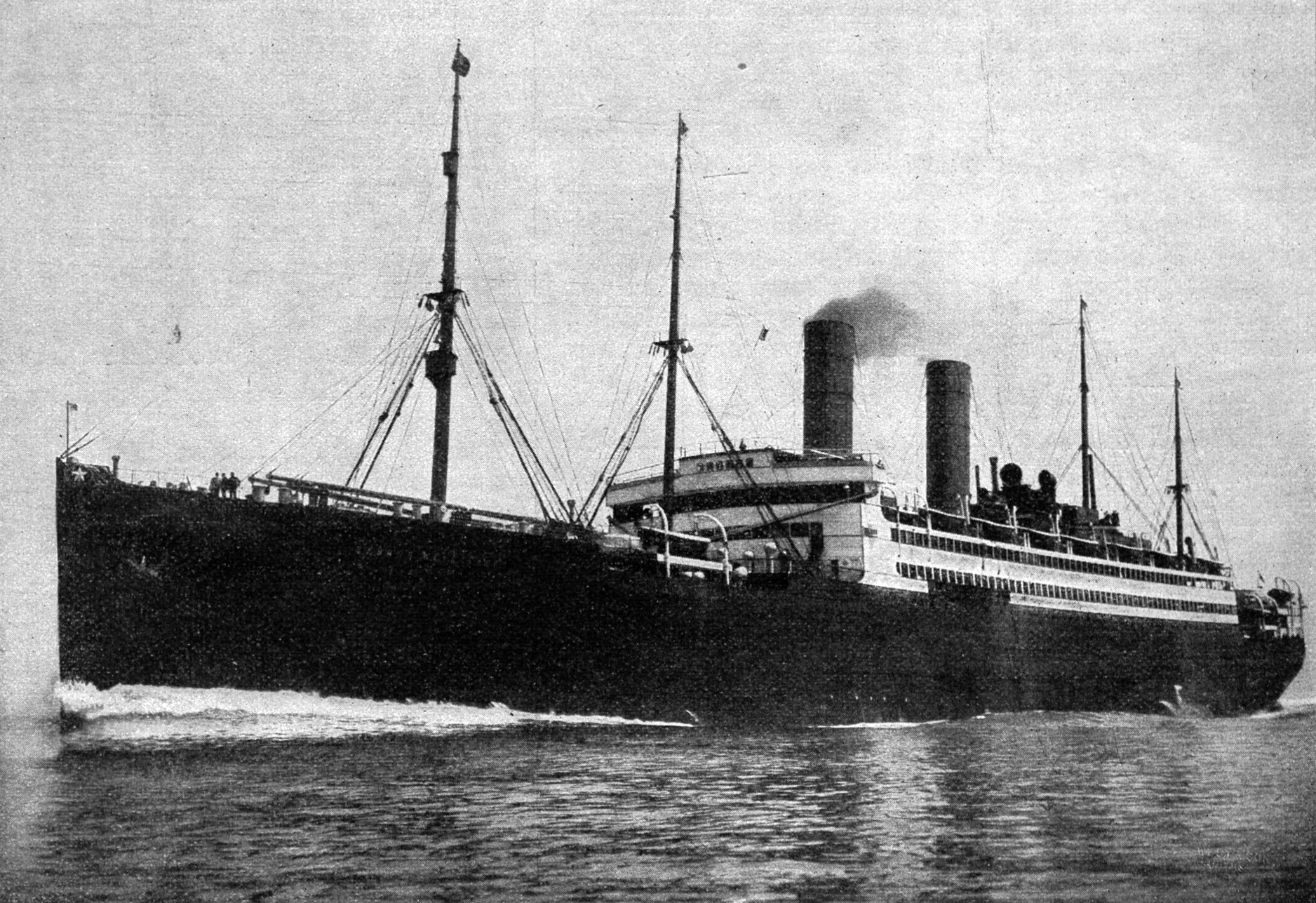

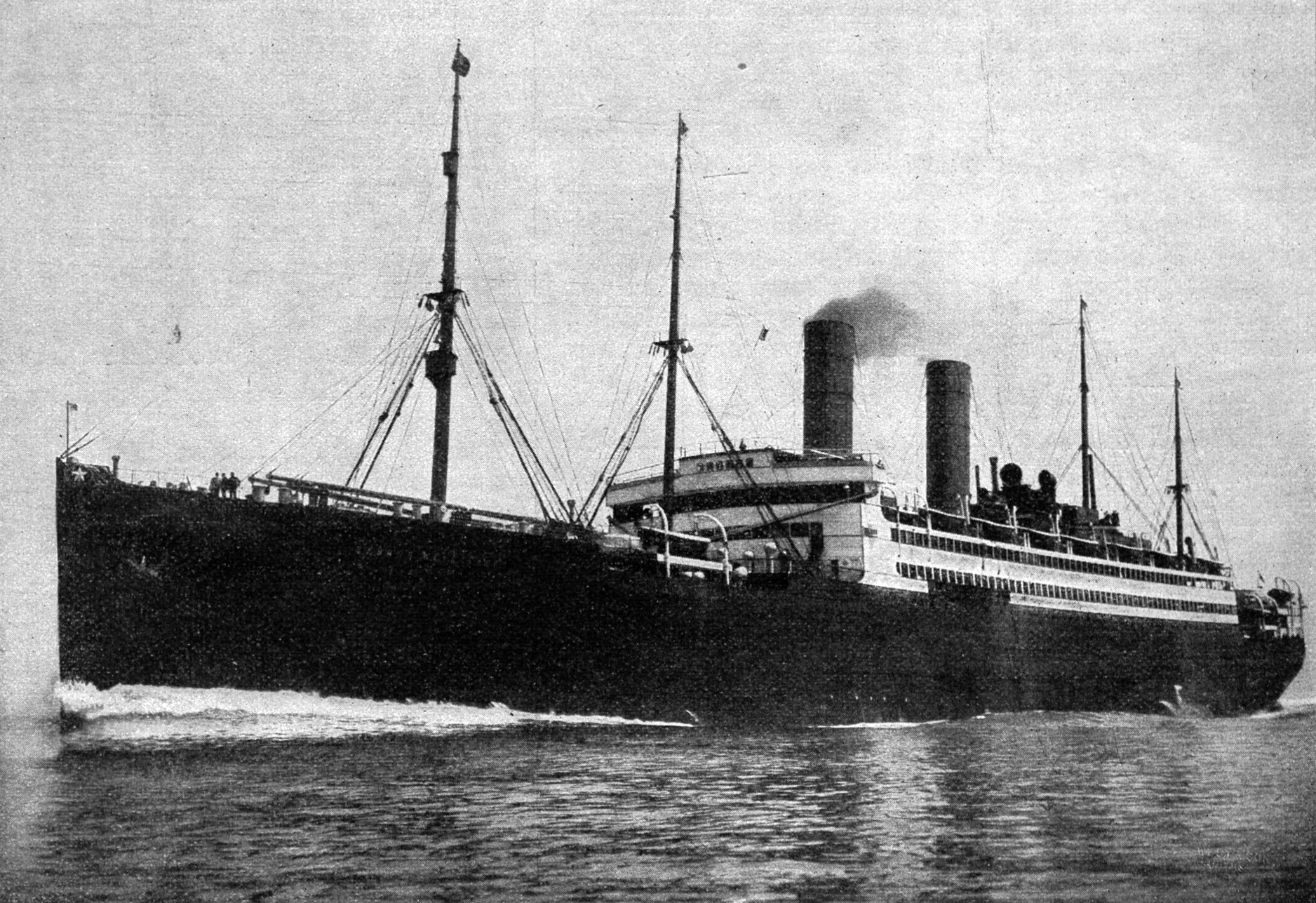

SS ''George Washington'' was an ocean liner built within two years (1907–1908) by

SS ''George Washington'' was an ocean liner built within two years (1907–1908) by ' s engines consumed an economical of coal daily, or about one-third as much as the Cunard speedsters ''Lusitania'' and ''Mauretania''. By using less coal, and, consequently, needing less space to carry it, the liner was able to carry up to of cargo. The liner also featured the Stone-Lloyd system of hydraulically operated bulkhead doors for her thirteen watertight compartments.

''George Washington'' had accommodations for nearly 2,900 passengers, with 900 divided between first and second class and the balance as third class or

On 22 June, the liner hosted a press luncheon, and, the next afternoon, hosted some 3,000 members of the

On 22 June, the liner hosted a press luncheon, and, the next afternoon, hosted some 3,000 members of the ' s position, acknowledged receipt of the warning,Drechsel, pp. 33–34. one of several her radio operators received. On 15 April, ''George Washington'' received garbled transmissions that informed that ''Titanic'' had struck an iceberg less than twelve hours later, and in nearly the same position as the one that ''George Washington'' had reported. Edwin Drechsel, in his 2-volume chronicle of North German Lloyd, draws comparisons between the iceberg photographed by ''George Washington'' (and first published in his book),Drechsel's father, Willy Drechsel, was the Second Officer on ''George Washington'' in April 1912. and a better-known photo taken from the

' s imperial suites after a four-day visit to New York in May; the Chinese Imperial flag flew from the ' s November crossing was ' s imperial suites. The following January, English playwright

''George Washington'' continued operating on the Bremen – New York route until World War I when she sought refuge in New York, a neutral port in 1914. With the American entry into the war in 1917, ''George Washington'' was taken over 6 April and towed to the

''George Washington'' continued operating on the Bremen – New York route until World War I when she sought refuge in New York, a neutral port in 1914. With the American entry into the war in 1917, ''George Washington'' was taken over 6 April and towed to the

Started in February 1918; as a means to relieve the stress the troops, sailors, and officers were under aboard a ship in the danger zone; it was written by officers who had previous literary experience and produced by men who had printing and publishing experience. It was printed on a small hand press – 5,000 copies with the first issue but this was increased to 7,000 – and titled ''The Hatchet'' (a reference to the tale about

Started in February 1918; as a means to relieve the stress the troops, sailors, and officers were under aboard a ship in the danger zone; it was written by officers who had previous literary experience and produced by men who had printing and publishing experience. It was printed on a small hand press – 5,000 copies with the first issue but this was increased to 7,000 – and titled ''The Hatchet'' (a reference to the tale about

ocean liner

An ocean liner is a passenger ship primarily used as a form of transportation across seas or oceans. Ocean liners may also carry cargo or mail, and may sometimes be used for other purposes (such as for pleasure cruises or as hospital ships).

Ca ...

built in 1908 for the Bremen

Bremen ( Low German also: ''Breem'' or ''Bräm''), officially the City Municipality of Bremen (german: Stadtgemeinde Bremen, ), is the capital of the German state Free Hanseatic City of Bremen (''Freie Hansestadt Bremen''), a two-city-state cons ...

-based North German Lloyd

Norddeutscher Lloyd (NDL; North German Lloyd) was a German shipping company. It was founded by Hermann Henrich Meier and Eduard Crüsemann in Bremen on 20 February 1857. It developed into one of the most important German shipping companies of th ...

and was named after George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

, the first President of the United States. The ship was also known as USS ''George Washington'' (ID-3018) and USAT ''George Washington'' in service of the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

and United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

, respectively, during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. In the interwar period, she reverted to her original name of SS ''George Washington''. During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, the ship was known as both USAT ''George Washington'' and, briefly, as USS ''Catlin'' (AP-19), in a short, second stint in the U.S. Navy.

When ''George Washington'' was launched in 1908, she was the largest German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

-built steamship and the third-largest ship in the world. ''George Washington'' was built to emphasize comfort over speed and was sumptuously appointed in her first-class passenger areas. The ship could carry a total of 2,900 passengers, and made her maiden voyage in January 1909 to New York. In June 1911, ''George Washington'' was the largest ship to participate in the Coronation Fleet Review

A fleet review or naval review is an event where a gathering of ships from a particular navy is paraded and reviewed by an incumbent head of state and/or other official civilian and military dignitaries. A number of national navies continue to ...

by the United Kingdom's newly crowned king, George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother ...

.

On 14 April 1912, ''George Washington'' passed a particularly large iceberg

An iceberg is a piece of freshwater ice more than 15 m long that has broken off a glacier or an ice shelf and is floating freely in open (salt) water. Smaller chunks of floating glacially-derived ice are called "growlers" or "bergy bits". The ...

south of the Grand Banks of Newfoundland

The Grand Banks of Newfoundland are a series of underwater plateaus south-east of the island of Newfoundland on the North American continental shelf. The Grand Banks are one of the world's richest fishing grounds, supporting Atlantic cod, sword ...

and radioed a warning to all ships in the area, including White Star Line

The White Star Line was a British shipping company. Founded out of the remains of a defunct packet company, it gradually rose up to become one of the most prominent shipping lines in the world, providing passenger and cargo services between ...

ocean liner , which sank near the same location. Throughout her German passenger career, contemporary news accounts often reported on notable persons—typically actors, singers, and politicians—who sailed on ''George Washington''.

At the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, ''George Washington'' was interned by the then-neutral United States, until that country entered into the conflict in April 1917. ''George Washington'' was seized by the United States and taken over for use as a troop transport by the U.S. Navy. Commissioned as USS ''George Washington'' (ID-3018), she sailed with her first load of American troops in December 1917.

In total, she carried 48,000 passengers to France, and returned 34,000 to the United States after the Armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the ...

. ''George Washington'' also carried U.S. President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

to France twice for the Paris Peace Conference. ''George Washington'' was decommissioned in 1920 and handed over the United States Shipping Board

The United States Shipping Board (USSB) was established as an emergency agency by the 1916 Shipping Act (39 Stat. 729), on September 7, 1916. The United States Shipping Board's task was to increase the number of US ships supporting the World War ...

(USSB), who reconditioned her for passenger service. SS ''George Washington'' sailed in transatlantic passenger service for both the United States Mail Steamship Company (one voyage) and United States Lines

United States Lines was the trade name of an organization of the United States Shipping Board (USSB), Emergency Fleet Corporation (EFC) created to operate German liners seized by the United States in 1917. The ships were owned by the USSB and al ...

for ten years, before she was laid up in the Patuxent River

The Patuxent River is a tributary of the Chesapeake Bay in the state of Maryland. There are three main river drainages for central Maryland: the Potomac River to the west passing through Washington, D.C., the Patapsco River to the northeast ...

in Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean t ...

in 1931.

During World War II, the ship was re-commissioned by the U.S. Navy as USS ''Catlin'' (AP-19) for about six months and was operated by the British under Lend-Lease

Lend-Lease, formally the Lend-Lease Act and introduced as An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States (), was a policy under which the United States supplied the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and other Allied nations with food, oil, ...

, but her old coal-fired engines were too slow for effective combat use. After conversion to oil-fired boilers, the ship was chartered to the U.S. Army as USAT ''George Washington'' and sailed around the world in 1943 in trooping duties. The ship sailed in regular service to the United Kingdom and the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

from 1944 to 1947, and was laid up in Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore was ...

after ending her Army service. A fire in January 1951 damaged the ship severely, and she was sold for scrapping the following month.

Design and construction

SS ''George Washington'' was an ocean liner built within two years (1907–1908) by

SS ''George Washington'' was an ocean liner built within two years (1907–1908) by AG Vulcan

Aktien-Gesellschaft Vulcan Stettin (short AG Vulcan Stettin) was a German shipbuilding and locomotive building company. Founded in 1851, it was located near the former eastern German city of Stettin, today Polish Szczecin. Because of the limited ...

of Stettin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the German border, it is a major s ...

, Germany (now Szczecin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the German border, it is a major s ...

, Poland), for North German Lloyd

Norddeutscher Lloyd (NDL; North German Lloyd) was a German shipping company. It was founded by Hermann Henrich Meier and Eduard Crüsemann in Bremen on 20 February 1857. It developed into one of the most important German shipping companies of th ...

(german: link=no, Norddeutscher Lloyd or NDL).Bonsor, p. 570. Intended for Bremen

Bremen ( Low German also: ''Breem'' or ''Bräm''), officially the City Municipality of Bremen (german: Stadtgemeinde Bremen, ), is the capital of the German state Free Hanseatic City of Bremen (''Freie Hansestadt Bremen''), a two-city-state cons ...

– New York passenger service, the ship was named after George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

, the first President of the United States as a way to make the ship more appealing to immigrants, who then made up the majority of transatlantic passengers and believed formalities on arrival would be easier on a ship with an American name. ''George Washington'' was launched on 10 November 1908 by the United States Ambassador to Germany, David Jayne Hill

Rev. David Jayne Hill (June 10, 1850 – March 2, 1932) was an American academic, diplomat and author.

Early life

The son of Baptist minister David T. Hill, David Jayne Hill was born in Plainfield, New Jersey, on June 10, 1850. He graduated f ...

.The launching was originally scheduled for 31 October 1908, but was postponed due to low water in the Oder River

The Oder ( , ; Czech, Lower Sorbian and ; ) is a river in Central Europe. It is Poland's second-longest river in total length and third-longest within its borders after the Vistula and Warta. The Oder rises in the Czech Republic and flows t ...

. See: Drechsel, p. 374. At the time of her launch, she was the third-largest ocean liner in the world, behind only Cunard Line

Cunard () is a British shipping and cruise line based at Carnival House at Southampton, England, operated by Carnival Corporation & plc#Carnival United Kingdom, Carnival UK and owned by Carnival Corporation & plc. Since 2011, Cunard and its ...

ships and .Bonsor, p. 533. ''George Washington'' also became the largest German-built steamship, surpassing the Hamburg America Line

The Hamburg-Amerikanische Packetfahrt-Aktien-Gesellschaft (HAPAG), known in English as the Hamburg America Line, was a transatlantic shipping enterprise established in Hamburg, in 1847. Among those involved in its development were prominent citi ...

's , and held that distinction until the 1913 launch of Hamburg America's .Putnam, p. 164.

After ''George Washington'' was completed, she was reported in contemporary news accounts as being , though present-day sources agree on a figure of . Her displacement was reported as being approximately , more than twice the 18420 t displacement of the British battleship . She was powered by two quadruple-expansion steam engines that generated and propelled her considerably faster than the guaranteed by her builders. Because she was designed to emphasize comfort over speed, ''George Washington''steerage

Steerage is a term for the lowest category of passenger accommodation in a ship. In the nineteenth and early twentieth century considerable numbers of persons travelled from their homeland to seek a new life elsewhere, in many cases North America ...

. The ship had only eight decks rather than a more typical nine, which gave her passenger accommodations a spacious feel. The first-class passenger section included 31 cabins with attached baths, and the liner's imperial suites were designed by German architect Rudolf Alexander Schröder

Rudolf Alexander Schröder (26 January 1878 – 22 August 1962) was a German translator and poet. In 1962 he was awarded the Johann-Heinrich-Voß-Preis für Übersetzung. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature five times.

Career

Much ...

. The second-class, third-class, and steerage compartments were fitted out in a "comfortable manner" suitable for each class.

The first class public rooms were "sumptuously appointed", and included murals by German fresco

Fresco (plural ''frescos'' or ''frescoes'') is a technique of mural painting executed upon freshly laid ("wet") lime plaster. Water is used as the vehicle for the dry-powder pigment to merge with the plaster, and with the setting of the plast ...

artist Otto Bollhagen that commemorated the life and times of George Washington. First-class passengers could visit a separate lounge, a reading room decorated by Bruno Paul

Bruno Paul (19 January 1874 – 17 August 1968) was a German architect, illustrator, interior designer, and furniture designer.

Trained as a painter in the royal academy just as the Munich Secession developed against academic art, he first ca ...

, a two-story smoking room

A smoking room (or smoking lounge) is a room which is specifically provided and furnished for smoking, generally in buildings where smoking is otherwise prohibited.

Locations and facilities

Smoking rooms can be found in public buildings suc ...

, and their own dining room that spanned the width of the ship. The upper and lower floors of the smoking room were joined by a broad staircase which helped, according to a report in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', make it "one of the most attractive parts" of the first-class areas. The dining saloon seated 350 diners at small tables designed for between two and six diners in "roomy and moveable" red Morocco chairs. The dining room was decorated in white and gold, with a gilded dome rising above, while its walls featured floral designs executed against a blue background.

Other first-class passenger amenities aboard ''George Washington'' included a gymnasium with machines for "Swedish exercises", and two electric elevators for those who didn't want to exercise at all. There was also a darkroom open to amateur photographers; 20 dog kennels, along with a kennel master; a solarium decorated with green and gold tapestry, palms, and flowers of all kinds; and an open air cafe on the awning deck for taking after-dinner coffee. Second-class passengers had a separate dining room, a drawing room

A drawing room is a room in a house where visitors may be entertained, and an alternative name for a living room. The name is derived from the 16th-century terms withdrawing room and withdrawing chamber, which remained in use through the 17th cen ...

, and a smoking room, and third-class passengers had similar amenities.

North German Lloyd passenger service

''George Washington'' began her maiden voyage on 12 June 1909, sailing from Bremen to New York viaSouthampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

and Cherbourg

Cherbourg (; , , ), nrf, Chèrbourg, ) is a former commune and subprefecture located at the northern end of the Cotentin peninsula in the northwestern French department of Manche. It was merged into the commune of Cherbourg-Octeville on 28 Feb ...

. On board were 1,169 passengers which included a German press contingent; Philipp Heineken, the ''Generaldirektor'' of North German Lloyd; and a chimpanzee

The chimpanzee (''Pan troglodytes''), also known as simply the chimp, is a species of great ape native to the forest and savannah of tropical Africa. It has four confirmed subspecies and a fifth proposed subspecies. When its close relative t ...

named Consul, billed as "his Darwinian Highness", the "Almost Monkey-Man", who was coming to America under contract for the William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was a British textile designer, poet, artist, novelist, architectural conservationist, printer, translator and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts Movement. He w ...

Vaudeville

Vaudeville (; ) is a theatrical genre of variety entertainment born in France at the end of the 19th century. A vaudeville was originally a comedy without psychological or moral intentions, based on a comical situation: a dramatic composition ...

circuit.

Upon her arrival in New York on 20 June, ''George Washington'' was greeted by the unfurling of the official banner of the League of Peace from the Singer Building

The Singer Building (also known as the Singer Tower) was an office building and early skyscraper in Manhattan, New York City. The headquarters of the Singer Manufacturing Company, it was at the northwestern corner of Liberty Street and Broad ...

,The Singer Building

The Singer Building (also known as the Singer Tower) was an office building and early skyscraper in Manhattan, New York City. The headquarters of the Singer Manufacturing Company, it was at the northwestern corner of Liberty Street and Broad ...

, then the world's tallest building at , was shorter than ''George Washington'' was long. See: and docked at 18:30 at the North German Lloyd piers in Hoboken, New Jersey

Hoboken ( ; Unami: ') is a city in Hudson County in the U.S. state of New Jersey. As of the 2020 U.S. census, the city's population was 60,417. The Census Bureau's Population Estimates Program calculated that the city's population was 58,690 ...

. Coincidentally, , an ocean liner of the unrelated Austro-American Line, was in port when ''George Washington'' docked in New York for the first time.

On 22 June, the liner hosted a press luncheon, and, the next afternoon, hosted some 3,000 members of the

On 22 June, the liner hosted a press luncheon, and, the next afternoon, hosted some 3,000 members of the Daughters of the American Revolution

The Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) is a lineage-based membership service organization for women who are directly descended from a person involved in the United States' efforts towards independence.

A non-profit group, they promote ...

who presented a commemorative bronze tablet. Stewart L. Woodford

Stewart Lyndon Woodford (September 3, 1835 – February 14, 1913) was an American attorney and politician who served as a member of the United States House of Representatives and Lieutenant Governor of New York.

Born in New York City, Woodf ...

, a former Congressman and ambassador, spoke at the ceremony dedicating the tablet, which was placed at the base of the staircase in the first-class smoking room. Beginning 24 June, the North German Lloyd opened ''George Washington'' to the public for five days of viewing of the new ship.

Sailing on her first eastbound journey on 1 July, ''George Washington'' commenced regular service between Bremen and New York with intermediate stops in Southampton and Cherbourg. North German Lloyd considered the ''Washington'', as her crew affectionately called her, such a success that they soon ordered another liner of similar, but slightly larger, size.The new ship, SS ''Columbus'', was launched in 1913 and scheduled for her maiden voyage on 11 August 1914. The outbreak of the war cancelled her completion and the ship never sailed in passenger service for North German Lloyd. She was awarded to the United Kingdom as a war reparation

War reparations are compensation payments made after a war by one side to the other. They are intended to cover damage or injury inflicted during a war.

History

Making one party pay a war indemnity is a common practice with a long history.

R ...

and was renamed and sailed for the White Star Line

The White Star Line was a British shipping company. Founded out of the remains of a defunct packet company, it gradually rose up to become one of the most prominent shipping lines in the world, providing passenger and cargo services between ...

. See: Drechsel, p. 433.

On 24 June 1911, ''George Washington'' participated in the Coronation Fleet Review

A fleet review or naval review is an event where a gathering of ships from a particular navy is paraded and reviewed by an incumbent head of state and/or other official civilian and military dignitaries. A number of national navies continue to ...

by the United Kingdom's newly crowned king, George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother ...

. Stationed at the head of the second row of merchant ship

A merchant ship, merchant vessel, trading vessel, or merchantman is a watercraft that transports cargo or carries passengers for hire. This is in contrast to pleasure craft, which are used for personal recreation, and naval ships, which are ...

s, ''George Washington''—full dress

Western dress codes are a set of dress codes detailing what clothes are worn for what occasion. Conversely, since most cultures have intuitively applied some level equivalent to the more formal Western dress code traditions, these dress codes a ...

ed for the occasion—was reported by ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ( ...

'' as "by far the largest ship present".

While headed to New York on the morning of 14 April 1912, crew aboard ''George Washington'' observed a large iceberg

An iceberg is a piece of freshwater ice more than 15 m long that has broken off a glacier or an ice shelf and is floating freely in open (salt) water. Smaller chunks of floating glacially-derived ice are called "growlers" or "bergy bits". The ...

as the ship passed south of the Grand Banks of Newfoundland

The Grand Banks of Newfoundland are a series of underwater plateaus south-east of the island of Newfoundland on the North American continental shelf. The Grand Banks are one of the world's richest fishing grounds, supporting Atlantic cod, sword ...

. By noon the ship passed within a half-mile (900 m) of the iceberg, estimated by the crew at above the waterline and long. After recording the ship's position, ''George Washington'' radioed a warning to all ships in the area. The White Star steamship , some east of ''George Washington''Hamburg America Line

The Hamburg-Amerikanische Packetfahrt-Aktien-Gesellschaft (HAPAG), known in English as the Hamburg America Line, was a transatlantic shipping enterprise established in Hamburg, in 1847. Among those involved in its development were prominent citi ...

ship , purportedly of the ''Titanic'' iceberg. Drechsel suggests that the iceberg photographed and reported by ''George Washington'' may have been one and the same.

Notable passengers

Throughout her Lloyd transatlantic career ''George Washington'' carried some notable and interesting passengers to and from Europe. In August 1909Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud ( , ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating pathologies explained as originating in conflicts i ...

sailed from Bremen bound for New York on his one and only trip to the US. He was accompanied by his colleagues Carl Jung

Carl Gustav Jung ( ; ; 26 July 1875 – 6 June 1961) was a Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst who founded analytical psychology. Jung's work has been influential in the fields of psychiatry, anthropology, archaeology, literature, ph ...

and Sándor Ferenczi

Sándor Ferenczi (7 July 1873 – 22 May 1933) was a Hungarian psychoanalyst, a key theorist of the psychoanalytic school and a close associate of Sigmund Freud.

Biography

Born Sándor Fränkel to Baruch Fränkel and Rosa Eibenschütz, bo ...

. In February 1910, banker Edgar Speyer

Sir Edgar Speyer, 1st Baronet (7 September 1862 – 16 February 1932) was an American-born financier and philanthropist. Barker 2004. He became a British subject in 1892 and was chairman of Speyer Brothers, the British branch of the Speyer fami ...

, a Privy Counsellor

The Privy Council (PC), officially His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, is a formal body of advisers to the sovereign of the United Kingdom. Its membership mainly comprises senior politicians who are current or former members of ei ...

appointed by Edward VII of the United Kingdom

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910.

The second child and eldest son of Queen Victoria and ...

, arrived for a visit to the United States. Prince Tsai Tao, the uncle of the Emperor of China, departed in one of ''George Washington''mainmast

The mast of a sailing vessel is a tall spar, or arrangement of spars, erected more or less vertically on the centre-line of a ship or boat. Its purposes include carrying sails, spars, and derricks, and giving necessary height to a navigation lig ...

in his honor as the ship departed. In October, Henry W. Taft, brother of U.S. President William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

returned from a visit to Europe. In December, disgraced Arctic explorer Frederick Cook

Frederick Albert Cook (June 10, 1865 – August 5, 1940) was an American explorer, physician, and ethnographer who claimed to have reached the North Pole on April 21, 1908. That was nearly a year before Robert Peary, who similarly clai ...

arrived on the liner; conflicting opinions on the veracity of his claims of reaching the North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distinguish from the Ma ...

nearly caused a fight to erupt on board. On the same voyage as Cook, German actor Ernst von Possart

Ernst von Possart (11 May 18418 April 1921) was a German actor and theatre director.

Possart was born in Berlin and was early an actor at Breslau, Bern, and Hamburg. Connected with the Munich Court Theatre after 1864, he became the oberregis ...

arrived for his first stage performances in New York in over 20 years.

Composer Engelbert Humperdinck, after attending the debut of his opera ''Königskinder

' (German for ''King's Children'' or “Royal Children”) is a stage work by Engelbert Humperdinck that exists in two versions: as a melodrama and as an opera or more precisely a '' Märchenoper''. The libretto was written by Ernst Rosmer (pen n ...

'' at the Metropolitan Opera

The Metropolitan Opera (commonly known as the Met) is an American opera company based in New York City, resident at the Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center, currently situated on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. The company is opera ...

, sailed on ''George Washington'' in early January 1911 in order to attend the opera's Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

premiere. American sculptor George Grey Barnard

George Grey Barnard (May 24, 1863 – April 24, 1938), often written George Gray Barnard, was an American sculptor who trained in Paris. He is especially noted for his heroic sized '' Struggle of the Two Natures in Man'' at the Metropolitan Museu ...

returned to New York in April amidst controversy over some of his works. An organization called the National Society for Protection of Morals was protesting the presence of nude figures in sculptures he executed for the Pennsylvania State Capitol in Harrisburg

Harrisburg is the capital city of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Dauphin County. With a population of 50,135 as of the 2021 census, Harrisburg is the 9th largest city and 15th largest municipality in ...

. July saw ''George Washington'' transporting a menagerie of sorts. The liner was carrying a shipment from India of 6 white peacocks, 2 lions, 2 elephants, 150 monkeys, and some 2,000 canaries destined for the recently organized Saint Louis Zoological Park. In August, two men of note—both headed for Berlin—sailed on ''George Washington''. Nathan Straus

Nathan Straus (January 31, 1848 – January 11, 1931) was an American merchant and philanthropist who co-owned two of New York City's biggest department stores, R. H. Macy & Company and Abraham & Straus. He is a founding father and namesake f ...

, co-owner with his brother Isidor

Isidore ( ; also spelled Isador, Isadore and Isidor) is an English and French masculine given name. The name is derived from the Greek name ''Isídōros'' (Ἰσίδωρος) and can literally be translated to "gift of Isis." The name has survived ...

of R.H. Macy & Company, sailed as the U.S. delegate to the third world congress for the protection of infants held in Berlin. Congressman Richard Bartholdt, charged by President Taft to deliver a statue of Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben

Friedrich Wilhelm August Heinrich Ferdinand von Steuben (born Friedrich Wilhelm Ludolf Gerhard Augustin Louis von Steuben; September 17, 1730 – November 28, 1794), also referred to as Baron von Steuben (), was a Prussian military officer who ...

to the German government, sailed with the statue, which was a gift from the American people.

Financier and philanthropist J. P. Morgan, Jr.

John Pierpont Morgan Jr. (September 7, 1867 – March 13, 1943) was an American banker, finance executive, and philanthropist. He inherited the family fortune and took over the business interests including J.P. Morgan & Co. after his father J. ...

returned from a two-month trip to Europe in November 1912; his wife followed him home the next month. Also arriving on ''George Washington''Mary Garden

A Mary garden is a small sacred garden enclosing a statue or shrine of the Virgin Mary, who is known to many Christians as the Blessed Virgin, Our Lady, or the Mother of God. In the New Testament, Mary is the mother of Jesus of Nazareth. Mary g ...

, a Scottish-born soprano

A soprano () is a type of classical female singing voice and has the highest vocal range of all voice types. The soprano's vocal range (using scientific pitch notation) is from approximately middle C (C4) = 261 Hz to "high A" (A5) = 880& ...

, who was returning from a sabbatical in Scotland. The next month, opera singers Frieda Hempel

Frieda Hempel (26 June 1885 – 7 October 1955) was a German lyric coloratura soprano singer in operatic and concert work who had an international career in Europe and the United States.

Life

Hempel was born in Leipzig and studied first at the ...

and Leon Rains

Eleazer Leon Rains, also ''Léon Rains'', (October 1, 1870 – June 11, 1954) was an American operatic bass, film actor and voice teacher. After studies in New York City and Paris, he toured in the U.S. for two years with Frank Damrosch's opera t ...

, both headed for appearances with the Metropolitan Opera, arrived on the same voyage as Mrs. Morgan. Hempel, a German soprano

A soprano () is a type of classical female singing voice and has the highest vocal range of all voice types. The soprano's vocal range (using scientific pitch notation) is from approximately middle C (C4) = 261 Hz to "high A" (A5) = 880& ...

, was with the Berlin Royal Opera

The (), also known as the Berlin State Opera (german: Staatsoper Berlin), is a listed building on Unter den Linden boulevard in the historic center of Berlin, Germany. The opera house was built by order of Prussian king Frederick the Great from ...

, and American tenor

A tenor is a type of classical male singing voice whose vocal range lies between the countertenor and baritone voice types. It is the highest male chest voice type. The tenor's vocal range extends up to C5. The low extreme for tenors is wide ...

Rains was with the Saxon Royal Opera of Dresden

Dresden (, ; Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; wen, label= Upper Sorbian, Drježdźany) is the capital city of the German state of Saxony and its second most populous city, after Leipzig. It is the 12th most populous city of Germany, the fourth ...

.

Newlyweds Francis B. Sayre, an assistant district attorney in New York, and Jessie Woodrow Wilson Sayre, the daughter of U.S. President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

, sailed in November 1913 for a European honeymoon. The couple, wed at the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in ...

, traveled in one of ''George Washington''W. Somerset Maugham

William Somerset Maugham ( ; 25 January 1874 – 16 December 1965) was an English writer, known for his plays, novels and short stories. Born in Paris, where he spent his first ten years, Maugham was schooled in England and went to a German un ...

quietly slipped out of New York on ''George Washington''. Maugham had arrived in New York in mid November to see Billie Burke

Mary William Ethelbert Appleton Burke (August 7, 1884 – May 14, 1970) was an American actress who was famous on Broadway and radio, and in silent and sound films. She is best known to modern audiences as Glinda the Good Witch of the North ...

in the New York premiere of his play, ''The Land of Promise''.

Socialite

A socialite is a person from a wealthy and (possibly) aristocratic background, who is prominent in high society. A socialite generally spends a significant amount of time attending various fashionable social gatherings, instead of having tradit ...

and philanthropist Sarah Polk Fall, left for a six-month tour of Europe in August 1923. She was traveling First Class to England. Her daughter Saidee Grant and her husband New York Banker Rollin Grant, along with their servants accompanied her for the journey. They returned to New York in February 1924.

World War I

''George Washington'' continued operating on the Bremen – New York route until World War I when she sought refuge in New York, a neutral port in 1914. With the American entry into the war in 1917, ''George Washington'' was taken over 6 April and towed to the

''George Washington'' continued operating on the Bremen – New York route until World War I when she sought refuge in New York, a neutral port in 1914. With the American entry into the war in 1917, ''George Washington'' was taken over 6 April and towed to the New York Navy Yard

The Brooklyn Navy Yard (originally known as the New York Navy Yard) is a shipyard and industrial complex located in northwest Brooklyn in New York City, New York (state), New York. The Navy Yard is located on the East River in Wallabout Bay, a ...

for conversion into a transport. She commissioned 6 September 1917.

''George Washington'' sailed with her first load of troops 4 December 1917 and during the next 2 years made 18 round trip voyages in support of the American Expeditionary Forces

The American Expeditionary Forces (A. E. F.) was a formation of the United States Army on the Western Front of World War I. The A. E. F. was established on July 5, 1917, in France under the command of General John J. Pershing. It fought along ...

. During this period she also made several special voyages. President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

and the American representatives to the Paris Peace Conference sailed for Europe in ''George Washington'' 4 December 1918. On this crossing she was protected by , and was escorted into Brest, France, 13 December by ten battleship

A battleship is a large armour, armored warship with a main artillery battery, battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1 ...

s and twenty-eight destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed ...

s in an impressive demonstration of American naval strength. After carrying 4000 soldiers back home to the U.S., ''George Washington'' carried Assistant Secretary of the Navy

Assistant Secretary of the Navy (ASN) is the title given to certain civilian senior officials in the United States Department of the Navy.

From 1861 to 1954, the Assistant Secretary of the Navy was the second-highest civilian office in the Depa ...

Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

and the Chinese and Mexican

Mexican may refer to:

Mexico and its culture

*Being related to, from, or connected to the country of Mexico, in North America

** People

*** Mexicans, inhabitants of the country Mexico and their descendants

*** Mexica, ancient indigenous people ...

peace commissions to France in January 1919. On 24 February, she returned President Wilson to the United States.

The President again embarked on board ''George Washington'' in March 1919; arriving France 13 March, and returned at the conclusion of the historic conference 8 July 1919. During this voyage, the ship carried radiotelephone equipment, then a new technology, and during much of the trip Wilson was able converse with officials back in Washington. The radio transmitter was also used to broadcast entertainment to the troops, and it was planned to broadcast Wilson's 4 July Independence Day speech to accompanying vessels, which would have been the first radio address by a U.S. president. However Wilson stood too far from the microphone, and the technicians were too intimidated to try to get him to stand in the correct spot.

During the fall of 1919, ''George Washington'' carried another group of distinguished passengers— King Albert and Queen Elizabeth

Queen Elizabeth, Queen Elisabeth or Elizabeth the Queen may refer to:

Queens regnant

* Elizabeth I (1533–1603; ), Queen of England and Ireland

* Elizabeth II (1926–2022; ), Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms

* Queen ...

of Belgium and their party. Arriving New York 2 October, the royal couple paid a visit before returning to Brest 12 November. Subsequently, the ship was decommissioned 28 November 1919 after having transported some 48,000 passengers to Europe and 34,000 back to the United States. The ship was turned over to the United States Shipping Board

The United States Shipping Board (USSB) was established as an emergency agency by the 1916 Shipping Act (39 Stat. 729), on September 7, 1916. The United States Shipping Board's task was to increase the number of US ships supporting the World War ...

on 28 January 1920.

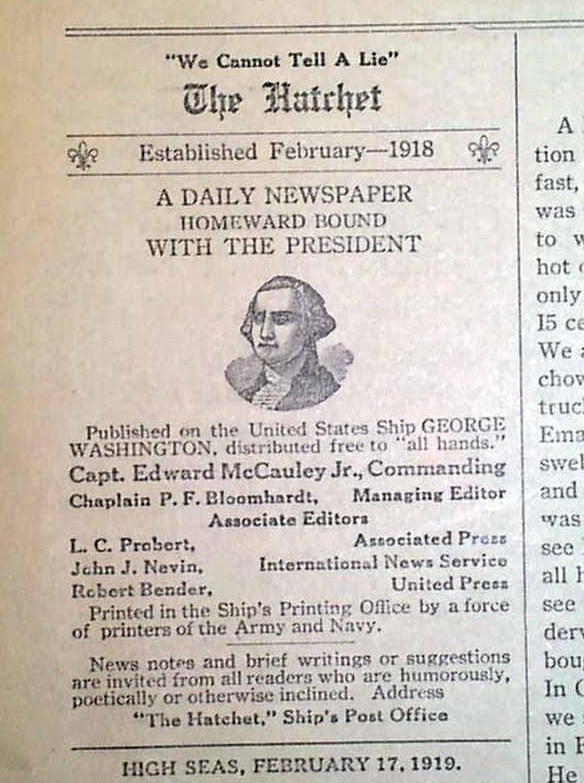

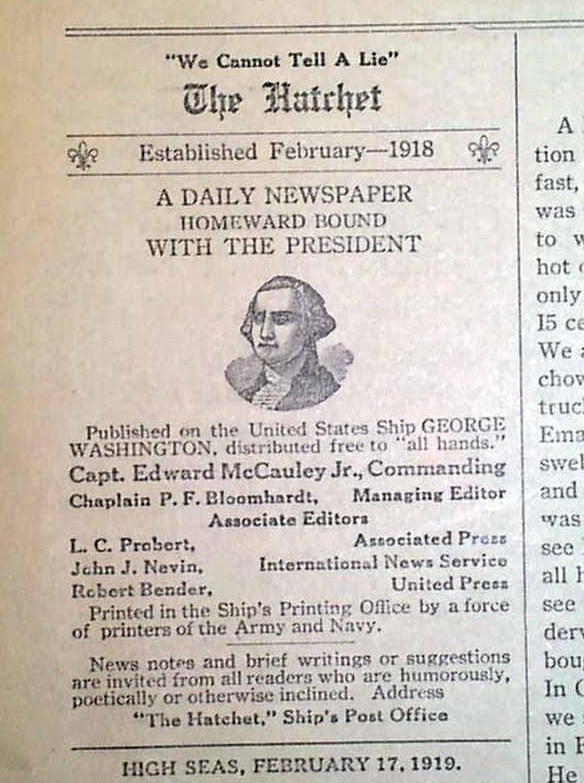

''The Hatchet'' newspaper

Started in February 1918; as a means to relieve the stress the troops, sailors, and officers were under aboard a ship in the danger zone; it was written by officers who had previous literary experience and produced by men who had printing and publishing experience. It was printed on a small hand press – 5,000 copies with the first issue but this was increased to 7,000 – and titled ''The Hatchet'' (a reference to the tale about

Started in February 1918; as a means to relieve the stress the troops, sailors, and officers were under aboard a ship in the danger zone; it was written by officers who had previous literary experience and produced by men who had printing and publishing experience. It was printed on a small hand press – 5,000 copies with the first issue but this was increased to 7,000 – and titled ''The Hatchet'' (a reference to the tale about George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

and the cherry tree). News from the ship and news received by radio were in the single-sheet newspaper. The masthead in 1919 listed the ship chaplain as managing editor and three reporters—one each from the Associated Press, International News Service and the United Press as "associate editors". The newspaper pages, printed on a shipboard press, measured about . The newspaper's motto: "We Cannot Tell a Lie". Its front page claimed it had "The Largest Circulation on the Atlantic Ocean".

Interwar passenger service

After her delivery to the United States Shipping Board (USSB), ''George Washington'' was used to transport 250 members of the American Legion to France as guests of the French Government in 1921. The vessel was then reconditioned by USSB for transatlantic service, and chartered by the U.S. Mail Steamship Company, for whom she made one voyage to Europe in March 1921. The company was taken over by the government August 1921 and its name changed to theUnited States Lines

United States Lines was the trade name of an organization of the United States Shipping Board (USSB), Emergency Fleet Corporation (EFC) created to operate German liners seized by the United States in 1917. The ships were owned by the USSB and al ...

. In 1930, she transported the first group of American Gold Star Mothers to France to visit the graves of their sons. ''George Washington'' served the Line on the transatlantic route until 1931 when she was laid up in the Patuxent River

The Patuxent River is a tributary of the Chesapeake Bay in the state of Maryland. There are three main river drainages for central Maryland: the Potomac River to the west passing through Washington, D.C., the Patapsco River to the northeast ...

, Maryland.

World War II

''George Washington'' was reacquired for Navy use from the United States Maritime Commission on 28 January 1941 and commissioned as USS ''Catlin'' (AP-19) on 13 March 1941. She was named in honor of Brigadier General (United States), Brigadier General Albertus W. Catlin, United States Marine Corps, USMC. It was found, however, that the coal-burning engines did not give the required speed for protection against submarines, and she was decommissioned on 26 September 1941. Because of their great need for ships in 1941, Great Britain took the ship over underLend-Lease

Lend-Lease, formally the Lend-Lease Act and introduced as An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States (), was a policy under which the United States supplied the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and other Allied nations with food, oil, ...

on 29 September 1941 as ''George Washington'', but they found after one voyage to Dominion of Newfoundland, Newfoundland that her aging boilers could not safely maintain sufficient steam pressure to drive her otherwise serviceable engines. A secondary contributing factor was the difficulty in manning her with sufficient skilled stokers – the role having been supplanted with the steady introduction of oil fired ships in the 1930s.Bone, David W., E:''Merchantman Rearmed'', Chapter XIII. Chatto and Windus, London, 1949. With the ship unfit for combat service the British returned her to the War Shipping Administration (WSA) on 17 April 1942.

The ship was next operated under General Agency Agreement by the Waterman Steamship Co., Mobile, Alabama, and made a voyage to Panama. After her return on 5 September 1942 the WSA assigned ''George Washington'' to be converted to an oil-burner at Todd Shipbuilding's Brooklyn, New York, Brooklyn Yard. When she emerged on 17 April 1943, the transport was bareboat chartered by the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

and made a voyage to Casablanca and back to New York with troops between April and May 1943.A coastal transport, ''George Washington'' built 1924 , was WSA operated from East Coast ports to the islands of the Caribbean. That ship was dubbed little ''George Washington''.

In July, ''George Washington'' sailed from New York to the Panama Canal, thence to Los Angeles and Brisbane, Queensland, Brisbane, Australia. Returning to Los Angeles, she sailed again in September to Bombay and Cape Town, and arrived at New York to complete her round-the-world voyage in December 1943. In January 1944 ''George Washington'' began regular service to the United Kingdom and the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

, again carrying troops in support of the Allies in Europe. She made frequent stops at Le Havre, Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

, and Liverpool.

''George Washington'' was taken out of service and returned to the Maritime Commission 21 April 1947. She remained tied to a pier at Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore was ...

, until a fire damaged her 16 January 1951. She was subsequently sold for scrap to the Boston Metals Corporation of Baltimore on 13 February 1951.

Awards

*World War I Victory Medal (United States), World War I Victory Medal *American Defense Service Medal *Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal *European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal *World War II Victory Medal *Army of Occupation Medal with "Germany" claspNotes

References

Bibliography

* * * * *External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:George Washington Ships built in Stettin Steamships Ocean liners Ships of Norddeutscher Lloyd World War I auxiliary ships of the United States World War II auxiliary ships of the United States Transports of the United States Navy Transport ships of the United States Army Ships of the United States Lines Troop ships of the United Kingdom Troop ships of the United States 1908 ships Maritime incidents in 1951 Ships named for Founding Fathers of the United States