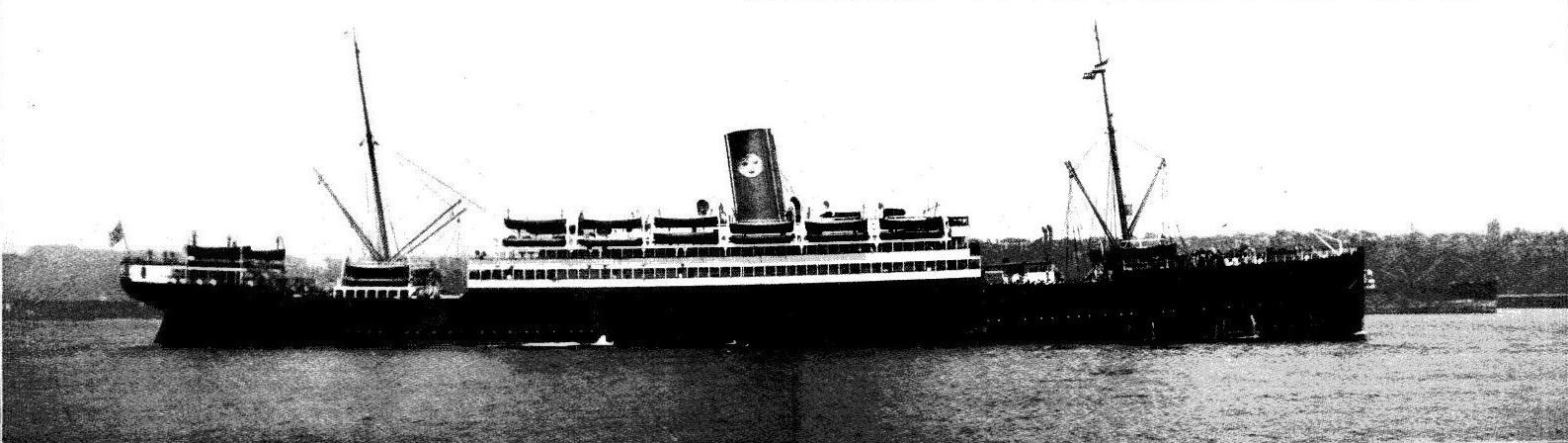

SS Drottningholm on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

SS ''Drottningholm'' was one of the earliest

From August 1914 the UK Government used ''Virginian'' as a troop ship. Then in December the

From August 1914 the UK Government used ''Virginian'' as a troop ship. Then in December the

steam turbine

A steam turbine is a machine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work on a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Charles Parsons in 1884. Fabrication of a modern steam turbin ...

ocean liner

An ocean liner is a passenger ship primarily used as a form of transportation across seas or oceans. Ocean liners may also carry cargo or mail, and may sometimes be used for other purposes (such as for pleasure cruises or as hospital ships).

Ca ...

s. She was designed as a transatlantic

Transatlantic, Trans-Atlantic or TransAtlantic may refer to:

Film

* Transatlantic Pictures, a film production company from 1948 to 1950

* Transatlantic Enterprises, an American production company in the late 1970s

* ''Transatlantic'' (1931 film), ...

liner and mail ship for Allan Line

The Allan Shipping Line was started in 1819, by Alexander Allan (ship-owner), Captain Alexander Allan of Saltcoats, Ayrshire, trading and transporting between Scotland and Montreal, a route which quickly became synonymous with the Allan Line. By th ...

, built in Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

, and launched in 1904 as RMS ''Virginian''. Her sister ship

A sister ship is a ship of the same class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They often share a ...

, , was built in Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, launched four months earlier, and was the World's first turbine-powered liner.

In the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

''Virginian'' spent a few months as a troopship

A troopship (also troop ship or troop transport or trooper) is a ship used to carry soldiers, either in peacetime or wartime. Troopships were often drafted from commercial shipping fleets, and were unable land troops directly on shore, typicall ...

and was then converted into an armed merchant cruiser

An armed merchantman is a merchant ship equipped with guns, usually for defensive purposes, either by design or after the fact. In the days of sail, piracy and privateers, many merchantmen would be routinely armed, especially those engaging in lo ...

(AMC). In August 1917 a U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare role ...

damaged her with a torpedo.

In 1920 she was sold to the Swedish American Line

Swedish American Line ( sv, Svenska Amerika Linien, abbr. SAL) was a Swedish passenger shipping line. It was founded in December 1914 under the name Rederiaktiebolaget Sverige-Nordamerika and began ocean liner service from Gothenburg to New Y ...

and remnamed ''Drottningholm''. As a neutral passenger ship during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

she performed notable service repatriating thousands of civilians of various countries on both sides of the war.

In 1948 ''Drottningholm'' was then sold to a company in the Italian Home Lines

Home Lines was an Italian passenger shipping company that operated both ocean liners and cruise ships. The company was founded in 1946, and it ceased operations in 1988 when merged into Holland America Line. Although based in Genoa, Home Lines was ...

group, who changed her name to ''Brasil''.

In 1951 Home Lines chartered her to Hamburg America Line

The Hamburg-Amerikanische Packetfahrt-Aktien-Gesellschaft (HAPAG), known in English as the Hamburg America Line, was a transatlantic shipping enterprise established in Hamburg, in 1847. Among those involved in its development were prominent citi ...

, and the line her name changed again, this time to ''Homeland''.

''Homeland'' was scrapped in Italy in 1955.

Background

The World's first steam turbine merchant ship, , was launched in 1901. She was a technological and commercial success, but was only a excursion steamship making short-sea trips in and around theFirth of Clyde

The Firth of Clyde is the mouth of the River Clyde. It is located on the west coast of Scotland and constitutes the deepest coastal waters in the British Isles (it is 164 metres deep at its deepest). The firth is sheltered from the Atlantic ...

, and her running costs – and hence passenger fares – were higher than those of her competitors with conventional reciprocating engine

A reciprocating engine, also often known as a piston engine, is typically a heat engine that uses one or more reciprocating pistons to convert high temperature and high pressure into a rotating motion. This article describes the common featu ...

s.

However, in October 1903 Allan Line announced that it had ordered a pair of new liners, that they would be turbine-powered, and that they would have the same three-screw

A screw and a bolt (see '' Differentiation between bolt and screw'' below) are similar types of fastener typically made of metal and characterized by a helical ridge, called a ''male thread'' (external thread). Screws and bolts are used to fa ...

arrangement as ''King Edward''. And on 28 January 1904, seven months before ''Victorian'' was launched, the Government of Canada

The government of Canada (french: gouvernement du Canada) is the body responsible for the federal administration of Canada. A constitutional monarchy, the Crown is the corporation sole, assuming distinct roles: the executive, as the ''Crown ...

announced it had awarded Allan Line a transatlantic mail contract.

The Canadian contract required a regular scheduled service with four ships. Allan Line allocated the new ''Victorian'' and ''Virginian'', which were still being built, and its existing liners ''Bavarian'' and ''Tunisian''. The subsidy would be $5,000 per trip for ''Bavarian'' and ''Tunisian'', and $10,000 per trip for each of the new turbine ships.

Design and building

Allan Line ordered both ''Victorian'' and ''Virginian'' fromWorkman, Clark and Company

Workman, Clark and Company was a shipbuilding company based in Belfast.

History

The business was established by Frank Workman and George Clark in Belfast in 1879 and incorporated Workman, Clark and Company Limited in 1880. By 1895 it was the UK ...

in Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdo ...

. But Workman, Clark did not find enough labour to build both ships in time, so the order for ''Virginian'' was transferred to Alexander Stephen and Sons

Alexander Stephen and Sons Limited, often referred to simply as Alex Stephens or just Stephens, was a Scottish shipbuilding company based in Linthouse, Glasgow, on the River Clyde and, initially, on the east coast of Scotland.

History

The comp ...

at Linthouse

Linthouse is a neighbourhood in the city of Glasgow, Scotland. It is situated directly south of the River Clyde and lies immediately west of Govan, with other adjacent areas including Shieldhall and the Southern General Hospital to the west, a ...

on the River Clyde

The River Clyde ( gd, Abhainn Chluaidh, , sco, Clyde Watter, or ) is a river that flows into the Firth of Clyde in Scotland. It is the ninth-longest river in the United Kingdom, and the third-longest in Scotland. It runs through the major cit ...

.

''Virginian'' was launched on 25 August 1904, four months after ''Victorian''. But ''Victorian'' completion was then delayed by performance problems with her turbines. Both sisters were completed in March 1905.

As built, ''Virginian'' had three Parsons turbines. A high-pressure turbine drove her middle screw. Its exhaust steam was fed to a pair of low-pressure turbines that drove her port and starboard

Port and starboard are nautical terms for watercraft and aircraft, referring respectively to the left and right sides of the vessel, when aboard and facing the bow (front).

Vessels with bilateral symmetry have left and right halves which are ...

screws. The three turbines combined gave her a total power output of 12,000 IHP.

''Virginian'' was long, her beam was and her depth was . She had berths for 1,912 passengers: 426 in first class, 286 in second class and 1,000 in third class. Her holds had of refrigerated space for perishable cargo. As built, her tonnage

Tonnage is a measure of the cargo-carrying capacity of a ship, and is commonly used to assess fees on commercial shipping. The term derives from the taxation paid on ''tuns'' or casks of wine. In modern maritime usage, "tonnage" specifically ref ...

s were and .

RMS ''Virginian''

''Virginian'' began her maiden voyage fromLiverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

on 6 April 1905, a fortnight after ''Victorian''. She called at Moville

Moville (; ) is a coastal town located on the Inishowen Peninsula of County Donegal, Ireland, close to the northern tip of the island of Ireland. It is the first coastal town of the Wild Atlantic Way when starting on the northern end.

Location

...

in Ireland the next day and reached Halifax, Nova Scotia

Halifax is the capital and largest municipality of the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, and the largest municipality in Atlantic Canada. As of the 2021 Census, the municipal population was 439,819, with 348,634 people in its urban area. The ...

on the morning of 14 April. Two months later ''Virginian'' set a westbound record, leaving Moville at 1400 hrs on 9 June and reaching Cape Race

Cape Race is a point of land located at the southeastern tip of the Avalon Peninsula on the island of Newfoundland, in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. Its name is thought to come from the original Portuguese name for this cape, "Raso", mea ...

at 2100 hrs on 13 June. This was despite having to slow down for a bank of fog.

The speed at which steam turbines run efficiently is several times faster than the speed at which marine propellers work efficiently. But the turbines in ''Victorian'' and ''Virginian'', like those in ''King Edward'', drove the propellers directly, without reduction gearing. As a result ''Virginian'' suffered cavitation

Cavitation is a phenomenon in which the static pressure of a liquid reduces to below the liquid's vapour pressure, leading to the formation of small vapor-filled cavities in the liquid. When subjected to higher pressure, these cavities, cal ...

, which not only impedes propulsion but also damages propellers.

''Virginian'' also tended to roll

Roll or Rolls may refer to:

Movement about the longitudinal axis

* Roll angle (or roll rotation), one of the 3 angular degrees of freedom of any stiff body (for example a vehicle), describing motion about the longitudinal axis

** Roll (aviation), ...

violently in heavy seas.

''Titanic'' sinking

By 1912 ''Virginian'' was equipped forwireless telegraphy

Wireless telegraphy or radiotelegraphy is transmission of text messages by radio waves, analogous to electrical telegraphy using cables. Before about 1910, the term ''wireless telegraphy'' was also used for other experimental technologies for ...

, operating on the 300 and 600 metre wavelengths. Her call sign

In broadcasting and radio communications, a call sign (also known as a call name or call letters—and historically as a call signal—or abbreviated as a call) is a unique identifier for a transmitter station. A call sign can be formally assigne ...

was MGN.

When RMS ''Titanic

RMS ''Titanic'' was a British passenger liner, operated by the White Star Line, which sank in the North Atlantic Ocean on 15 April 1912 after striking an iceberg during her maiden voyage from Southampton, England, to New York City, United ...

'' sank on 15 April 1912, ''Virginian'' was about north of her, steaming in the opposite direction. At 2310 hrs (0040 hrs ship's time) the Marconi Company

The Marconi Company was a British telecommunications and engineering company that did business under that name from 1963 to 1987. Its roots were in the Wireless Telegraph & Signal Company founded by Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi in 1897 ...

radio station at Cape Race relayed ''Titanic''s distress messages to ''Virginian'', whose Master

Master or masters may refer to:

Ranks or titles

* Ascended master, a term used in the Theosophical religious tradition to refer to spiritually enlightened beings who in past incarnations were ordinary humans

*Grandmaster (chess), National Master ...

, Captain Gambell changed course to try to reach ''Titanic''. ''Virginian'' also received ''Titanic''s distress signals. The last signal ''Virginian'' received from ''Titanic'' was at 0027 hrs (0157 hrs by ship's time), and "these signals were blurred and ended abruptly".

reached the position of the sinking and rescued 705 survivors. There was a false report that ''Virginian'' rescued some passengers and transferred them to ''Carpathia''. In fact ''Virginian'' did not arrive in time to assist.

There was also a false report that ''Virginian'' had taken ''Titanic'' in tow, that all of ''Titanic''s passengers were safe, and that Herbert Haddock, Master of , was the source of the report. Haddock, however, dismissed the report as "a flagrant invention".

Captain Gambell said ''Virginian'' passed where ''Titanic'' sank "at a distance of six or seven miles", but could get no closer as "The ice was closely packed... and there would have been great danger in going nearer. No boats, packages or wreckage were to be seen." Gambell said ''Virginian'' steamed toward ''Titanic'', until at 1000 hrs ''Carpathia'' signalled ''Virginian'' "Turn back. Everything O. K. Have 800 on board. Return to your northern track".

Substitute for ''Empress of Ireland''

On 29 May 1914Canadian Pacific

The Canadian Pacific Railway (french: Chemin de fer Canadien Pacifique) , also known simply as CPR or Canadian Pacific and formerly as CP Rail (1968–1996), is a Canadian Class I railway incorporated in 1881. The railway is owned by Canadi ...

lost the liner in a collision with the collier , and 1,024 people were killed. Canadian Pacific chartered ''Virginian'' from Allan Line to replace her. The charter was cut short by the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, which began on 28 July.

First World War

From August 1914 the UK Government used ''Virginian'' as a troop ship. Then in December the

From August 1914 the UK Government used ''Virginian'' as a troop ship. Then in December the British Admiralty

The Admiralty was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom responsible for the command of the Royal Navy until 1964, historically under its titular head, the Lord High Admiral – one of the Great Officers of State. For much of it ...

requisitioned her and had her converted into an armed merchant cruiser (AMC). Initially her armament was eight 4.7-inch QF guns and her pennant number

In the Royal Navy and other navies of Europe and the Commonwealth of Nations, ships are identified by pennant number (an internationalisation of ''pendant number'', which it was called before 1948). Historically, naval ships flew a flag that iden ...

was M 72. She was commissioned as HMS ''Virginian'' on 10 December 1914.

''Virginian'' joined the 10th Cruiser Squadron

The 10th Cruiser Squadron, also known as Cruiser Force B was a formation of cruisers of the British Royal Navy from 1913 to 1917 and then again from 1940 to 1946.

First formation

The squadron was established in July 1913 and allocated to the T ...

, with which she was on the Northern Patrol

The Northern Patrol, also known as Cruiser Force B and the Northern Patrol Force, was an operation of the British Royal Navy during the First World War and Second World War. The Patrol was part of the British "distant" blockade of Germany. Its ma ...

from December 1914 until the end of June 1917. She patrolled mostly around the Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ), or simply the Faroes ( fo, Føroyar ; da, Færøerne ), are a North Atlantic island group and an autonomous territory of the Kingdom of Denmark.

They are located north-northwest of Scotland, and about halfway bet ...

and the northern part of the Western Approaches

The Western Approaches is an approximately rectangular area of the Atlantic Ocean lying immediately to the west of Ireland and parts of Great Britain. Its north and south boundaries are defined by the corresponding extremities of Britain. The c ...

. In 1915 she occasionally patrolled the Norwegian Sea

The Norwegian Sea ( no, Norskehavet; is, Noregshaf; fo, Norskahavið) is a marginal sea, grouped with either the Atlantic Ocean or the Arctic Ocean, northwest of Norway between the North Sea and the Greenland Sea, adjoining the Barents Sea to ...

and the east and south coasts of Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

.

By October 1915 two of ''Virginian''s 4.7-inch guns were replaced with six-pounder guns. On 16 June 1916 ''Virginian'' arrived in Canada Dock

Canada Dock is a dock on the River Mersey, England, and part of the Port of Liverpool. It is situated in the northern dock system in Kirkdale. Canada Dock consists of a main basin nearest the river wall with three branch docks and a graving ...

in Liverpool to have her remaining 4.7-inch guns were replaced with six BL 6-inch and QF 6-inch naval gun

The QF 6-inch 40 calibre naval gun ( Quick-Firing) was used by many United Kingdom-built warships around the end of the 19th century and the start of the 20th century.

In UK service it was known as the QF 6-inch Mk I, II, III guns.Mk I, II and II ...

s. She was there for just over two months, until 18 August, and the Admiralty became concerned that the conversion took an inordinately long time.

By October 1916 ''Virginian''s armament also included depth charge

A depth charge is an anti-submarine warfare (ASW) weapon. It is intended to destroy a submarine by being dropped into the water nearby and detonating, subjecting the target to a powerful and destructive Shock factor, hydraulic shock. Most depth ...

s.

Convoy escort

From the beginning of July 1917 ''Virginian'' escorted transatlantic convoys. On 19 August 1917 ''Virginian'' left Liverpool escorting a convoy, which called atLough Swilly

Lough Swilly () in Ireland is a glacial fjord or sea inlet lying between the western side of the Inishowen, Inishowen Peninsula and the Fanad Peninsula, in County Donegal. Along with Carlingford Lough and Killary Harbour it is one of three glaci ...

on 20–21 August. U-boats attacked the convoy off the coast of Donegal Donegal may refer to:

County Donegal, Ireland

* County Donegal, a county in the Republic of Ireland, part of the province of Ulster

* Donegal (town), a town in County Donegal in Ulster, Ireland

* Donegal Bay, an inlet in the northwest of Ireland b ...

. torpedoed Leyland Line

The Leyland Line was a British shipping transport line founded in 1873 by Frederick Richards Leyland after his apprenticeship in the firm of John Bibby, Sons & Co. After Frederick Leyland's death, the company was taken over by Sir John Ellerma ...

's liner ''Devonian'' at 1152 hrs, and she sank at 1245 hrs about northeast of Tory Island

Tory Island, or simply Tory (officially known by its Irish name ''Toraigh''),Toraigh/Tory Island

Union Steamship Company's cargo liner ''Roscommon''.

At 1312 hrs ''Virginian'' sighted a periscope off her starboard bow and turned to engage the submarine. It was , which hit ''Virginian'' with a torpedo on her starboard quarter, killing three of her crew. The

At 1312 hrs ''Virginian'' sighted a periscope off her starboard bow and turned to engage the submarine. It was , which hit ''Virginian'' with a torpedo on her starboard quarter, killing three of her crew. The

In 1920 Swedish America Line bought ''Virginian'', reportedly for the equivalent of $100,000, and renamed her ''Drottningholm'', after a small community near

In 1920 Swedish America Line bought ''Virginian'', reportedly for the equivalent of $100,000, and renamed her ''Drottningholm'', after a small community near

In 1925

In 1925

In March 1942 the

In March 1942 the  US officials released about 125 passengers on 2 July and allowed them ashore. First to be released was the reporter Ruth Knowles, who had escaped execution by the Gestapo after spending a year serving with the

US officials released about 125 passengers on 2 July and allowed them ashore. First to be released was the reporter Ruth Knowles, who had escaped execution by the Gestapo after spending a year serving with the

''Drottningholm'' continued to serve the UK and French governments as a repatriation ship. Her white hull was emblazoned on both sides with her name and "Sverige" ("Sweden") in huge capital letters, between them were stripes of blue and yellow, the colours of the Swedish flag, and above them was the word "Diplomat". As a neutral ship she was fully lit so that her markings could be easily seen. By 1945 the word "Diplomat" had been replaced with "Freigeleit – Protected".

In October 1943 ''Drottningholm'' and arrived in the

''Drottningholm'' continued to serve the UK and French governments as a repatriation ship. Her white hull was emblazoned on both sides with her name and "Sverige" ("Sweden") in huge capital letters, between them were stripes of blue and yellow, the colours of the Swedish flag, and above them was the word "Diplomat". As a neutral ship she was fully lit so that her markings could be easily seen. By 1945 the word "Diplomat" had been replaced with "Freigeleit – Protected".

In October 1943 ''Drottningholm'' and arrived in the  In September 1944 the

In September 1944 the

''Drottningholm'' started a Gothenburg – Liverpool – New York service in late August 1945 and was expected to reach Gothenburg from New York by this route for the first time on 6 September.

On 22 July 1946 ''Drottningholm'' completed her first

''Drottningholm'' started a Gothenburg – Liverpool – New York service in late August 1945 and was expected to reach Gothenburg from New York by this route for the first time on 6 September.

On 22 July 1946 ''Drottningholm'' completed her first

At 1312 hrs ''Virginian'' sighted a periscope off her starboard bow and turned to engage the submarine. It was , which hit ''Virginian'' with a torpedo on her starboard quarter, killing three of her crew. The

At 1312 hrs ''Virginian'' sighted a periscope off her starboard bow and turned to engage the submarine. It was , which hit ''Virginian'' with a torpedo on her starboard quarter, killing three of her crew. The magazines

A magazine is a periodical publication, generally published on a regular schedule (often weekly or monthly), containing a variety of content. They are generally financed by advertising, purchase price, prepaid subscriptions, or by a combination ...

for her six-inch guns and part of her number five hold were flooded, but ''Virginian'' remained afloat. ''Virginian'' tried to return to Lough Swilly, but found it very difficult to steer. The destroyer tried to assist but failed. Nevertheless ''Virginian'' managed to reach Lough Swilly, and anchored at 2048 hrs.

''Virginian'' underwent temporary repairs, and then on 4–5 September 1917 returned to Liverpool, where she was dry dock

A dry dock (sometimes drydock or dry-dock) is a narrow basin or vessel that can be flooded to allow a load to be floated in, then drained to allow that load to come to rest on a dry platform. Dry docks are used for the construction, maintenance, ...

ed from 7 September until 16 November and returned to sea on 4 December.

In 1918 her pennant number was changed twice: to MI 95 in January and MI 52 in April. She continued to escort transatlantic convoys until just after the Armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the La ...

. She reached Liverpool on 30 November 1918 and was decommissioned some time thereafter.

Canadian Pacific had taken over Allan Line in 1917. The Admiralty released ''Virginian'' to her new owners, and in 1919 she was registered in Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-most populous city in Canada and List of towns in Quebec, most populous city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian ...

.

''Drottningholm''

In 1920 Swedish America Line bought ''Virginian'', reportedly for the equivalent of $100,000, and renamed her ''Drottningholm'', after a small community near

In 1920 Swedish America Line bought ''Virginian'', reportedly for the equivalent of $100,000, and renamed her ''Drottningholm'', after a small community near Stockholm

Stockholm () is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in Sweden by population, largest city of Sweden as well as the List of urban areas in the Nordic countries, largest urban area in Scandinavia. Approximately 980,000 people liv ...

that includes the royal

Royal may refer to:

People

* Royal (name), a list of people with either the surname or given name

* A member of a royal family

Places United States

* Royal, Arkansas, an unincorporated community

* Royal, Illinois, a village

* Royal, Iowa, a cit ...

Drottningholm Palace

The Drottningholm Palace ( sv, Drottningholms slott) is the private residence of the Swedish royal family. Drottningholm is near the capital Stockholm. Built on the island Lovön (in Ekerö Municipality of Stockholm County), it is one of Swede ...

. Götaverken

Götaverken was a shipbuilding company that was located on Hisingen, Gothenburg. During the 1930s it was the world's biggest shipyard by launched gross registered tonnage. It was founded in 1841, and went bankrupt in 1989.

History

The company w ...

in Gothenburg

Gothenburg (; abbreviated Gbg; sv, Göteborg ) is the second-largest city in Sweden, fifth-largest in the Nordic countries, and capital of the Västra Götaland County. It is situated by the Kattegat, on the west coast of Sweden, and has ...

refitted ''Drottningholm'', and particularly improved her third class accommodation. As refitted she had berths for 280 cabin class, 300 second class and 700 third class passengers. ''Drottningholm'' sailed from Gothenburg for the first time at the end of May, and arrived in New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

for the first time on 9 June. She retained her notoriety for rolling, and her new name inspired the nickname "Rollingholm" or "Rollinghome".

SAL had carried significant numbers of Swedish migrants to the USA, but in the 1920s new US immigration laws affected the transatlantic trade. In May 1921 the Federal Government implemented the Emergency Quota Act

__NOTOC__

The Emergency Quota Act, also known as the Emergency Immigration Act of 1921, the Immigration Restriction Act of 1921, the Per Centum Law, and the Johnson Quota Act (ch. 8, of May 19, 1921), was formulated mainly in response to the larg ...

, and allotted Sweden a quota for 20,000 migrants a year. Barely two months later, on 15 July, immigration authorities in New York detained 78 of ''Drottningholm''s second-class passengers on arrival. After four hours a message from Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

confirming that the quota for Sweden had not been fulfilled, and all 78 were allowed to land.

In 1922 Götaverken re-engined ''Drottningholm'' with new A/B De Lavals Ångturbin turbines. They were less powerful than her original Parsons turbines, because SAL wanted better fuel economy, but she could still do . Götaverken also replaced her direct drive with single-reduction gearing, which at last solved her cavitation problem. At the same time Götaverken enlarged her superstructure by extending her bridge deck aft. ''Drottningholm'' returned to service in 1923.

By 1930 ''Drottningholm''s tonnages were and . In 1934 her Swedish code letters

Code letters or ship's call sign (or callsign) Mtide Taurus - IMO 7626853"> SHIPSPOTTING.COM >> Mtide Taurus - IMO 7626853/ref> were a method of identifying ships before the introduction of modern navigation aids and today also. Later, with the i ...

KCMH were superseded by the call sign

In broadcasting and radio communications, a call sign (also known as a call name or call letters—and historically as a call signal—or abbreviated as a call) is a unique identifier for a transmitter station. A call sign can be formally assigne ...

SJMA.

On 8 January 1935 while ''Drottningholm'' was docking in fog at West 57th Street Pier in New York a steel cable fouled one of her propellers. Her return sailing was deferred from 12 to 15 January to allow time for her to be repaired in dry dock.

In 1937 ''Drottningholm''s hull was repainted white.

Notable passengers

In 1925

In 1925 Greta Garbo

Greta Garbo (born Greta Lovisa Gustafsson; 18 September 1905 – 15 April 1990) was a Swedish-American actress. Regarded as one of the greatest screen actresses, she was known for her melancholic, somber persona, her film portrayals of tragedy, ...

and Mauritz Stiller

Mauritz Stiller (born Moshe Stiller, 17 July 1883 – 18 November 1928) was a Swedish film director of Finnish Jewish origin, best known for discovering Greta Garbo and bringing her to America.

Stiller had been a pioneer of the Swedish film ...

sailed to the USA on ''Drottingholm'', leaving Gothenburg on 26 June and arriving in New York 10 days later.

On 30 December 1928 the newly-wed Count

Count (feminine: countess) is a historical title of nobility in certain European countries, varying in relative status, generally of middling rank in the hierarchy of nobility. Pine, L. G. ''Titles: How the King Became His Majesty''. New York: ...

and Countess

Count (feminine: countess) is a historical title of nobility in certain European countries, varying in relative status, generally of middling rank in the hierarchy of nobility.L. G. Pine, Pine, L. G. ''Titles: How the King Became His Majesty'' ...

Bernadotte left New York for Gothenburg on ''Drottningholm''. The couple returned to the USA on ''Drottningholm'' in June 1933.

In 1932 ''Drottningholm'' took Swedish athletes home from the 1932 Summer Olympics

The 1932 Summer Olympics (officially the Games of the X Olympiad and also known as Los Angeles 1932) were an international multi-sport event held from July 30 to August 14, 1932 in Los Angeles, California, United States. The Games were held duri ...

in Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world' ...

.

Second World War

In theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

Sweden was neutral, and until December 1941 so was the USA. At first ''Drottningholm'' continued the service between Gothenburg and New York.

By the end of January 1940 ''Drottningholm'' was the only SAL passenger liner still operating between Gothenburg and New York. On 3 February, 150 Finnish-American

Finnish Americans ( fi, amerikansuomalaiset, ) comprise Americans with ancestral roots from Finland or Finnish people who immigrated to and reside in the United States. The Finnish-American population numbers a little bit more than 650,000. Man ...

and Finnish-Canadian volunteers to fight for Finland in the Winter War sailed on ''Drottningholm'' from New York.

In March 1940 Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn

Yosef Yitzchak (Joseph Isaac) Schneersohn ( yi, יוסף יצחק שניאורסאהן; 21 June 1880 – 28 January 1950) was an Orthodox rabbi and the sixth Rebbe (spiritual leader) of the Chabad Lubavitch Chasidic movement. He is also known a ...

from German-occupied Poland

German-occupied Poland during World War II consisted of two major parts with different types of administration.

The Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany following the invasion of Poland at the beginning of World War II—nearly a quarter of the ...

reached New York aboard ''Drottningholm''.

Later in the war the US, UK and French governments each chartered ''Drottningholm'' to repatriate civilian internees, prisoners of war (PoWs) and diplomats between the two belligerent sides. She also carried PoWs and civilians for the Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million Volunteering, volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure re ...

.

One source states that ''Drottningholm'' repatriated 14,093 people. Another says she made 14 voyages and repatriated about 18,160 people. Another states that between 1940 and 1946 she made 30 voyages and carried about 25,000 people. The discrepancy may be because in August 1945 ''Drottningholm'' reverted from charter trips to her regular commercial Gothenburg – New York route, but she continued to carry refugees from Europe to North America.

In March 1942 the

In March 1942 the US Department of State

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other ...

and US Maritime Commission

The United States Maritime Commission (MARCOM) was an independent executive agency of the U.S. federal government that was created by the Merchant Marine Act of 1936, which was passed by Congress on June 29, 1936, and was abolished on May 24, 195 ...

chartered ''Drottningholm'' via an arrangement with Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

and the other Axis powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

, facilitated by the Swiss and Swedish governments and with the cooperation of 15 Latin American republics who had also broken off diplomatic relations with the Axis. On her first eastbound voyage she left from New York on 7 May 1942 for Lisbon

Lisbon (; pt, Lisboa ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 544,851 within its administrative limits in an area of 100.05 km2. Grande Lisboa, Lisbon's urban area extends beyond the city's administr ...

carrying Bulgarian, German, Italian, Romanian nationals including ambassadors and diplomats.

Her first westbound voyage was from Lisbon on 22 May, reaching New York on 1 June. Her passengers included the US diplomats Leland B. Morris

Leland Burnette Morris (February 7, 1886 – July 2, 1950) was an American diplomat. A native of Fort Clark, Texas, he was the first United States Ambassador to Iran, serving that post from 1944 to 1945. Earlier he was United States Ambassador to ...

and George F. Kennan

George Frost Kennan (February 16, 1904 – March 17, 2005) was an American diplomat and historian. He was best known as an advocate of a policy of containment of Soviet expansion during the Cold War. He lectured widely and wrote scholarly histo ...

.

''Drottningholm'' started her second eastbound crossing from Jersey City

Jersey City is the second-most populous city in the U.S. state of New Jersey, after Newark.South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the southe ...

. Many had been released from Nazi concentration camps

From 1933 to 1945, Nazi Germany operated more than a thousand concentration camps, (officially) or (more commonly). The Nazi concentration camps are distinguished from other types of Nazi camps such as forced-labor camps, as well as concen ...

.

When ''Drottningholm'' reached New York on 30 June 1942, US immigration authorities and military and naval intelligence personnel came aboard and prevented her passengers from disembarking until they had searched the ship and questioned each of the passengers. They included 470 US citizens, 110 South American diplomats and nationals, and a group of Canadian women rescued from the Egyptian

Egyptian describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of years of ...

liner , which the had sunk in April 1941.

US officials released about 125 passengers on 2 July and allowed them ashore. First to be released was the reporter Ruth Knowles, who had escaped execution by the Gestapo after spending a year serving with the

US officials released about 125 passengers on 2 July and allowed them ashore. First to be released was the reporter Ruth Knowles, who had escaped execution by the Gestapo after spending a year serving with the Chetniks

The Chetniks ( sh-Cyrl-Latn, Четници, Četnici, ; sl, Četniki), formally the Chetnik Detachments of the Yugoslav Army, and also the Yugoslav Army in the Homeland and the Ravna Gora Movement, was a Yugoslav royalist and Serbian nationa ...

resisting the German and Italian occupation of Yugoslavia. By 3 July nearly 700 passengers were still being held aboard. and by 8 July about 400 had been released, but 300 had been detained on Ellis Island

Ellis Island is a federally owned island in New York Harbor, situated within the U.S. states of New York and New Jersey, that was the busiest immigrant inspection and processing station in the United States. From 1892 to 1954, nearly 12 mi ...

until their cases were decided.

At the end of June 1942 the Nazi government

The government of Nazi Germany was totalitarian, run by the Nazi Party in Germany according to the Führerprinzip through the dictatorship of Adolf Hitler. Nazi Germany began with the fact that the Enabling Act was enacted to give Hitler's gover ...

withdrew its guarantee of safe passage for the ship, which prevented further exchanges. On 15 July ''Drottningholm'' left New York for Gothenburg carrying at least 800 Axis nationals. Most were German or Italian, plus a few Bulgarians and Romanians.

''Drottningholm'' continued to serve the UK and French governments as a repatriation ship. Her white hull was emblazoned on both sides with her name and "Sverige" ("Sweden") in huge capital letters, between them were stripes of blue and yellow, the colours of the Swedish flag, and above them was the word "Diplomat". As a neutral ship she was fully lit so that her markings could be easily seen. By 1945 the word "Diplomat" had been replaced with "Freigeleit – Protected".

In October 1943 ''Drottningholm'' and arrived in the

''Drottningholm'' continued to serve the UK and French governments as a repatriation ship. Her white hull was emblazoned on both sides with her name and "Sverige" ("Sweden") in huge capital letters, between them were stripes of blue and yellow, the colours of the Swedish flag, and above them was the word "Diplomat". As a neutral ship she was fully lit so that her markings could be easily seen. By 1945 the word "Diplomat" had been replaced with "Freigeleit – Protected".

In October 1943 ''Drottningholm'' and arrived in the Firth of Forth

The Firth of Forth () is the estuary, or firth, of several Scottish rivers including the River Forth. It meets the North Sea with Fife on the north coast and Lothian on the south.

Name

''Firth'' is a cognate of ''fjord'', a Norse word meani ...

carrying a total of about 4,000 Allied PoWs. They nicknamed ''Drottningholm'' "Trotting Home".

On 15 or 16 March 1944 ''Drottningholm'' reached Jersey City from Lisbon with 662 passengers including 160 civilian internees from Vittel internment camp

Ilag is an abbreviation of the German word ''Internierungslager''. They were internment camps established by the German Army in World War II to hold Allied civilians, caught in areas that were occupied by the German Army. They included United State ...

, 35 or 36 wounded US servicemen and a group of US diplomats from the former Vichy France

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its ter ...

, which Germany and Italy had occupied since November 1942. Internees released from Vittel included Mary Berg and her family. ''Drottningholm''s previous eastbound voyage had returned about 750 Germans to Europe.

In summer 1944 the Swiss government facilitated an agreement between the German and UK governments to repatriate almost all of each other's interned civilian nationals. ''Drottningholm'' was chartered, and on 11 July reached Lisbon carrying 900 German nationals who had been interned in South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

. She was then to await three trains carrying UK nationals from German-occupied Europe

German-occupied Europe refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly occupied and civil-occupied (including puppet governments) by the military forces and the government of Nazi Germany at various times between 1939 an ...

. 900 UK civilians and PoWs were brought by train under International Red Cross protection from German-occupied countries to Lisbon.

However, by summer 1944 the French Resistance was at its height, sabotaging rail and road transport in France, and especially in the southwest toward the Spanish frontier. The trains had left Germany on 6 July but were struggling to cross France. By 16 July the trains still had not arrived, so the UK was threatening to return the German internees to South Africa on ''Drottningholm''. However, on 21 July trains carrying 414 UK and other evacuees from Germany reached Irun

Irun ( es, Irún, eu, Irun) is a town of the Bidasoaldea region in the province of Gipuzkoa in the Basque Country (autonomous community), Basque Autonomous Community, Spain.

History

It lies on the foundations of the ancient Oiasso, cited as ...

on the Spanish frontier, where they changed to Spanish trains to continue toward Lisbon. On 4 August ''Drottningholm'' at last left Lisbon taking them to England.

In September 1944 the

In September 1944 the Swedish Red Cross

The Swedish Red Cross (Swedish: ''Svenska Röda Korset'') is a Swedish humanitarian organisation and a member of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. Founded in 1865, its purpose is to prevent and alleviate human suffering where ...

arranged an exchange of 2,345 Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

PoWs for a similar number of Germans. The Allied PoWs would be brought by sea and land to Gothenburg, where they would embark on ''Drottningholm'', and the UK troop ship

A troopship (also troop ship or troop transport or trooper) is a ship used to carry soldiers, either in peacetime or wartime. Troopships were often drafted from commercial shipping fleets, and were unable land troops directly on shore, typicall ...

. When the Allied prisoners reached Gothenburg their number was reported to be 2,600.

In March 1945 the UK and Germany agreed via Swiss and Swedish intermediaries to another exchange of civilian internees via ''Drottningholm''. On 15 March she left Gothenburg carrying UK internees, Argentinian and Turkish diplomats, Portuguese nationals and 212 released Channel Islands

The Channel Islands ( nrf, Îles d'la Manche; french: îles Anglo-Normandes or ''îles de la Manche'') are an archipelago in the English Channel, off the French coast of Normandy. They include two Crown Dependencies: the Bailiwick of Jersey, ...

internees. She had landed the Channel Islands and UK nationals in Liverpool by 23 March and was then due to take the Argentinians and Portuguese to Lisbon and the Turks to Istanbul.

On 11 April she arrived in Istanbul, carrying 137 Turkish Jews who had been released from Ravensbrück and Bergen-Belsen concentration camp

Bergen-Belsen , or Belsen, was a Nazi concentration camp in what is today Lower Saxony in northern Germany, southwest of the town of Bergen near Celle. Originally established as a prisoner of war camp, in 1943, parts of it became a concent ...

s as part of a prisoner exchange. Turkish authorities temporarily refused entry to 119 of her passengers.

On 3 May, the eve of the German unconditional surrender, ''Drottningholm'' was in Lisbon where she was meant to embark 200 Germans to be repatriated. But 61 of them refused to go, and the Portuguese authorities were reported to be assessing them as civilian refugees.

Post-war service

''Drottningholm'' started a Gothenburg – Liverpool – New York service in late August 1945 and was expected to reach Gothenburg from New York by this route for the first time on 6 September.

On 22 July 1946 ''Drottningholm'' completed her first

''Drottningholm'' started a Gothenburg – Liverpool – New York service in late August 1945 and was expected to reach Gothenburg from New York by this route for the first time on 6 September.

On 22 July 1946 ''Drottningholm'' completed her first radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, w ...

-equipped voyage from Gothenburg to New York. That August ''Drottningholm'' and ''Gripsholm'' resumed a fortnightly direct service between Gothenburg and New York.

On 16 September 1946 ''Drottningholm'' was in the middle of a New York labour dispute. 24 police officers encircled 10 National Maritime Union

The National Maritime Union (NMU) was an American labor union founded in May 1937. It affiliated with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) in July 1937. After a failed merger with a different maritime group in 1988, the union merged w ...

pickets to separate them from International Longshoremen's Association

The International Longshoremen's Association (ILA) is a North American labor union representing longshore workers along the East Coast of the United States and Canada, the Gulf Coast, the Great Lakes, Puerto Rico, and inland waterways. The ILA h ...

men who crossed the picket line to work the ship.

On 29 October 1946 SAL announced that at the end of the year it would sell ''Drottningholm'' and that her buyers would register her in Panama and operate her between Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the List of cities in Italy, sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian ce ...

and Argentina. However, the sale depended on ''Drottningholm''s replacement, the ''Stockholm

Stockholm () is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in Sweden by population, largest city of Sweden as well as the List of urban areas in the Nordic countries, largest urban area in Scandinavia. Approximately 980,000 people liv ...

'', being completed and entering service in time. ''Stockholm'' had been launched on 6 September but did not enter service until February 1948, which delayed ''Drottningholm''s sale. The sale price was not disclosed, but was reported to be in the order of $1,000,000.

By February 1948 ''Drottningholm'' was recorded as having made 220 transatlantic crossings for SAL, carried 192,735 transatlantic passengers and taken 12,882 people on cruises. She was also reported to have taken part in four rescues at sea, including two from Norwegian ships called ''Solglimt'' and ''Isefjell''.

''Drottningholm''s final westbound crossing for SAL took 11 days. She weathered three storms, was forced to heave to

In sailing, heaving to (to heave to and to be hove to) is a way of slowing a sailing vessel's forward progress, as well as fixing the helm and sail positions so that the vessel does not have to be steered. It is commonly used for a "break"; this ...

for 43 hours and was covered with ice when she reached New York two days late on 11 February 1948. Her Master, John Nordlander

John Leonard Nordlander (1894–1961) was a Swedish sea captain and Commander commissioned by the shipping line Swedish American Line, crossing the Atlantic Ocean 532 times.

During World War II, while serving as Master of , Captain Nordlander wa ...

, called it the worst passage he had had in 350 Atlantic crossings. The ship left New York for her final eastbound crossing as ''Drottningholm'' on 13 February.

Home Lines

The company that bought ''Drottningholm'' in 1948, renamed her ''Brasil'' and registered her in Panama is variously reported to have been the Panamanian Navigation Company or South American Lines. It was associated with the ItalianHome Lines

Home Lines was an Italian passenger shipping company that operated both ocean liners and cruise ships. The company was founded in 1946, and it ceased operations in 1988 when merged into Holland America Line. Although based in Genoa, Home Lines was ...

, and SAL was a major shareholder. ''Brasil''s new route was between Genoa and Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a b ...

.

In 1951 the ship was refitted in Italy with modern, more spacious accommodation for fewer passengers, and reduced tonnage. Her ownership was transferred to Mediterranean Lines, Hamburg America Line

The Hamburg-Amerikanische Packetfahrt-Aktien-Gesellschaft (HAPAG), known in English as the Hamburg America Line, was a transatlantic shipping enterprise established in Hamburg, in 1847. Among those involved in its development were prominent citi ...

chartered her, renamed her ''Homeland'' and put her on a route between Hamburg and New York via Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

and Halifax, NS.

In 1952 the ship was transferred to the route between Genoa and New York via Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

and Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within ci ...

. From 1953 she was owned directly by Home Lines.

The ship served for half a century. When built she was a technological pioneer. In one world war she was a warship and survived being torpedoed. In another she was a peace ship and did notable humanitarian work. By the end of her career was the oldest liner in scheduled transatlantic service.

In 1955 she was sold to the Società Italiana di Armamento (Sidarma), who scrapped her at Trieste

Trieste ( , ; sl, Trst ; german: Triest ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital city, and largest city, of the autonomous region of Friuli Venezia Giulia, one of two autonomous regions which are not subdivided into provi ...

. The liner was 50 years old by then and, other than the shore tender ''Nomadic

A nomad is a member of a community without fixed habitation who regularly moves to and from the same areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the popu ...

'', was the last surviving ship in connection with the ''Titanic'' incident as well as the last former member of the Allan Line.

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * *External links

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Drottningholm, SS 1904 ships World War I Auxiliary cruisers of the Royal Navy Ocean liners of Canada Ocean liners of the United Kingdom Passenger ships of Panama Passenger ships of Sweden RMS Titanic Ships built in Glasgow Steamships of Canada Steamships of Panama Steamships of Sweden Steamships of the United Kingdom World War I cruisers of the United Kingdom