Swedish invasion of Brandenburg (1674–75) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Swedish invasion of Brandenburg (1674–75) (german: Schwedeneinfall 1674/75) involved the occupation of the undefended

Immediately thereafter, in June 1672,

Immediately thereafter, in June 1672,

The Swedes then began to assemble an invasion force in

The Swedes then began to assemble an invasion force in

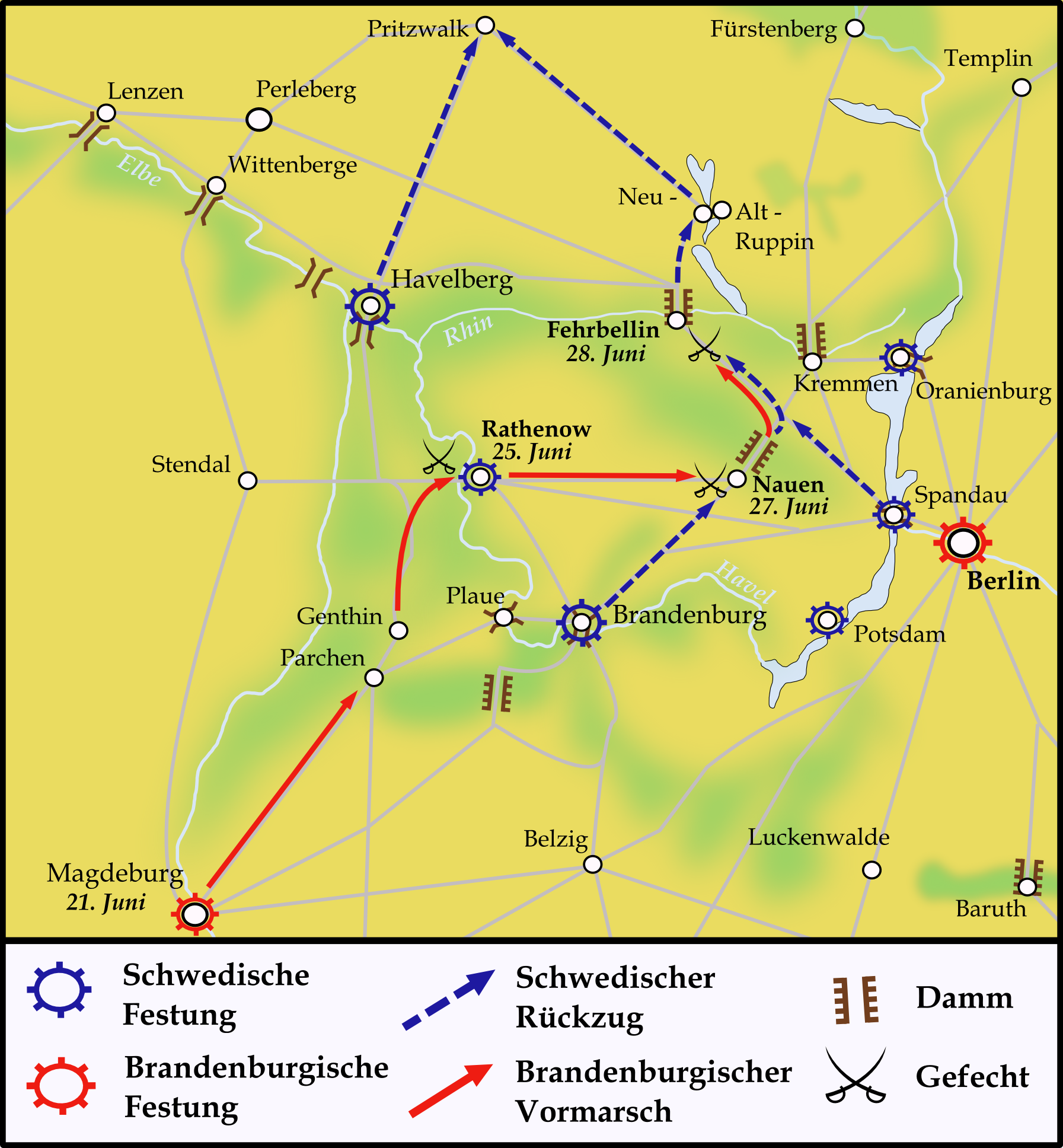

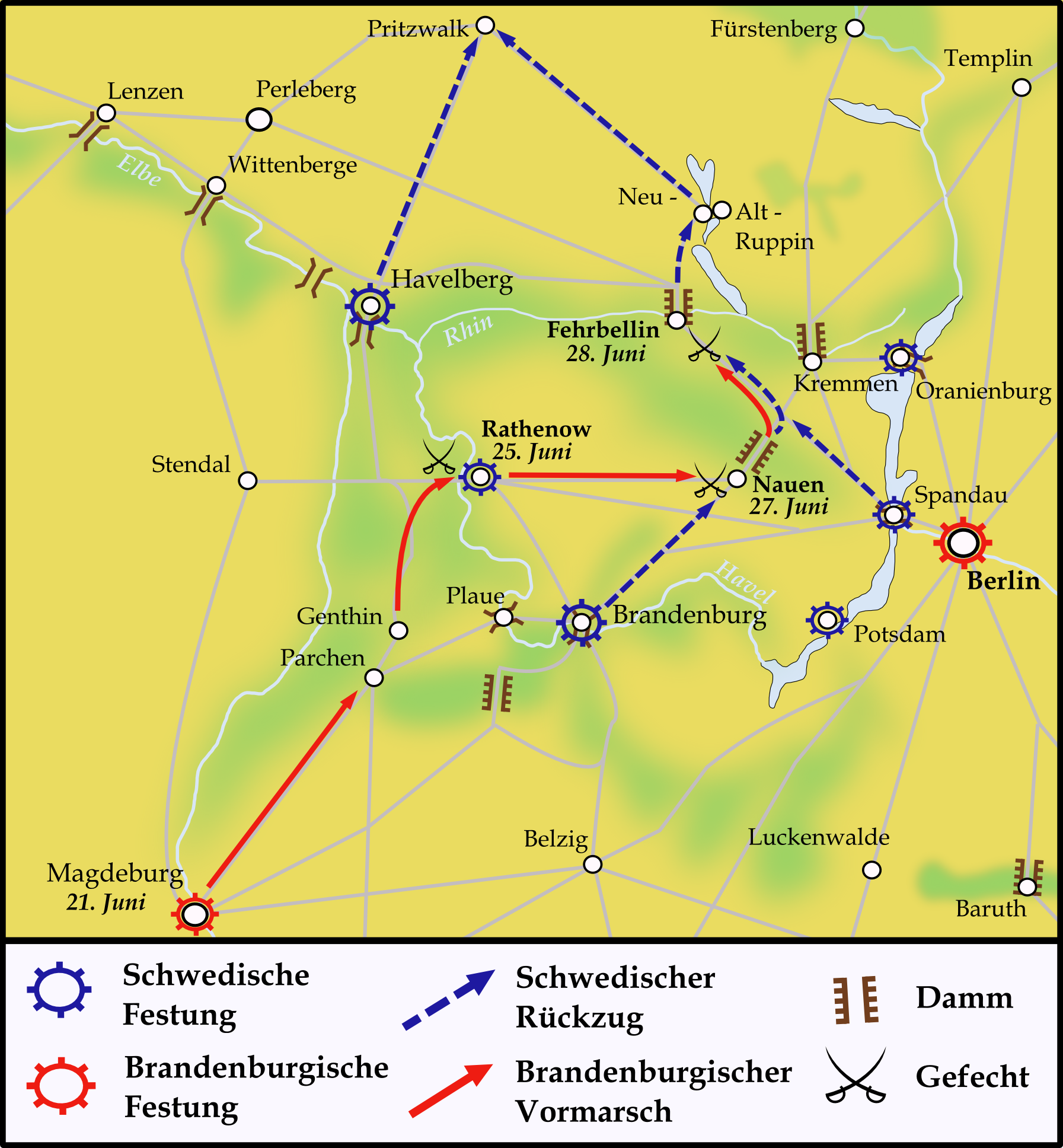

On 21 June the Brandenburg army reached Magdeburg. As a result of inadequate reconnaissance the arrival of Brandenburg appeared not to have been noticed by the Swedes, and so Frederick William adopted security measures to protect this tactical advantage. Not until he reached Magdeburg did he receive accurate information about the local situation. From intercepted letters, it appeared that Swedish and Hanoverian troops were about to join forces and attack the fortress of Magdeburg. After holding a military council, the Elector decided to break through the line of the Havel that the Swedes had now reached at their weakest point, at Rathenow. His intent was to separate the two parts of the Swedish army at Havelberg and the city of Brandenburg from one another.

On the morning of 23 June, around 3 a.m., the army set out from Magdeburg. Since the success of the plan depended on the element of surprise, the Elector advanced only with his cavalry, which consisted of 5,000 troopers in 30 squadrons and 600 dragoons. In addition there were 1,350

On 21 June the Brandenburg army reached Magdeburg. As a result of inadequate reconnaissance the arrival of Brandenburg appeared not to have been noticed by the Swedes, and so Frederick William adopted security measures to protect this tactical advantage. Not until he reached Magdeburg did he receive accurate information about the local situation. From intercepted letters, it appeared that Swedish and Hanoverian troops were about to join forces and attack the fortress of Magdeburg. After holding a military council, the Elector decided to break through the line of the Havel that the Swedes had now reached at their weakest point, at Rathenow. His intent was to separate the two parts of the Swedish army at Havelberg and the city of Brandenburg from one another.

On the morning of 23 June, around 3 a.m., the army set out from Magdeburg. Since the success of the plan depended on the element of surprise, the Elector advanced only with his cavalry, which consisted of 5,000 troopers in 30 squadrons and 600 dragoons. In addition there were 1,350

Since no order was issued to hold the pass at all costs because of its importance for the possible withdrawal of Swedish troops, the Brandenburg division attempted to rejoin the main army. On the afternoon of 17/27 June (after the actual battle at Nauen) they arrived back with the main body. The reports by this and the two other divisions reinforced the Elector's view to fight a decisive battle against the Swedes.

On 27 June the first battle between the Swedish rearguard and Brandenburg vanguard took place: the

Since no order was issued to hold the pass at all costs because of its importance for the possible withdrawal of Swedish troops, the Brandenburg division attempted to rejoin the main army. On the afternoon of 17/27 June (after the actual battle at Nauen) they arrived back with the main body. The reports by this and the two other divisions reinforced the Elector's view to fight a decisive battle against the Swedes.

On 27 June the first battle between the Swedish rearguard and Brandenburg vanguard took place: the

Margraviate of Brandenburg

The Margraviate of Brandenburg (german: link=no, Markgrafschaft Brandenburg) was a major principality of the Holy Roman Empire from 1157 to 1806 that played a pivotal role in the history of Germany and Central Europe.

Brandenburg developed out ...

by a Swedish army launched from Swedish Pomerania

Swedish Pomerania ( sv, Svenska Pommern; german: Schwedisch-Pommern) was a dominion under the Swedish Crown from 1630 to 1815 on what is now the Baltic coast of Germany and Poland. Following the Polish War and the Thirty Years' War, Sweden hel ...

during the period 26 December 1674 to the end of June 1675. The Swedish invasion sparked the Swedish-Brandenburg War that, following further declarations of war by European powers allied with Brandenburg, expanded into a North European conflict that did not end until 1679.

The trigger for the Swedish invasion was the participation of a 20,000 strong Brandenburg Army in the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

's war on France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan ar ...

as part of the Franco-Dutch War

The Franco-Dutch War, also known as the Dutch War (french: Guerre de Hollande; nl, Hollandse Oorlog), was fought between France and the Dutch Republic, supported by its allies the Holy Roman Empire, Spain, Brandenburg-Prussia and Denmark-No ...

. As a result, Sweden, a traditional ally of France, occupied the militarily unprotected margraviate with the declared aim of forcing the Elector of Brandenburg to sue for peace with France. In early June 1675 the Elector and his 15,000 strong army decamped at Schweinfurt

Schweinfurt ( , ; ) is a city in the district of Lower Franconia in Bavaria, Germany. It is the administrative centre of the surrounding district (''Landkreis'') of Schweinfurt and a major industrial, cultural and educational hub. The urban a ...

in Franconia

Franconia (german: Franken, ; Franconian dialect: ''Franggn'' ; bar, Frankn) is a region of Germany, characterised by its culture and Franconian dialect (German: ''Fränkisch'').

The three administrative regions of Lower, Middle and Upper F ...

, now southern Germany, and reached the city of Magdeburg

Magdeburg (; nds, label= Low Saxon, Meideborg ) is the capital and second-largest city of the German state Saxony-Anhalt. The city is situated at the Elbe river.

Otto I, the first Holy Roman Emperor and founder of the Archdiocese of Mag ...

on . In a campaign lasting less than ten days, Elector Frederick William forced the Swedish troops to retreat from the Margraviate of Brandenburg.

Background

After theWar of Devolution

In the 1667 to 1668 War of Devolution (, ), France occupied large parts of the Spanish Netherlands and Franche-Comté, both then provinces of the Holy Roman Empire (and properties of the King of Spain). The name derives from an obscure law known ...

, Louis XIV, King of France, pressed for retribution against the States-General. He initiated diplomatic activities with the aim of isolating Holland completely. To that end, on 24 April 1672 in Stockholm, France concluded a secret treaty with Sweden that bound the Scandinavian power to contribute 16,000 troops against any German state that gave military support to the Republic of Holland.

Louis XIV

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Ve ...

invaded the States-General - thus sparking the Franco-Dutch War

The Franco-Dutch War, also known as the Dutch War (french: Guerre de Hollande; nl, Hollandse Oorlog), was fought between France and the Dutch Republic, supported by its allies the Holy Roman Empire, Spain, Brandenburg-Prussia and Denmark-No ...

- and advanced to just short of Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the Capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population ...

. The Elector of Brandenburg, in accordance with treaty provisions, supported the Dutch in the fight against France with 20,000 men in August 1672. In December 1673, Brandenburg-Prussia and Sweden concluded a ten-year defensive alliance. However, both sides reserved freedom to choose their alliances in the event of war. Because of his defensive alliance with Sweden, during the period that followed the Elector of Brandenburg did not expect Sweden to enter the war on the French side. And despite the separate Treaty of Vossem agreed between Brandenburg and France on 16 June 1673, Brandenburg rejoined the war against France in the following year, when the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

declared an imperial war (''Reichskrieg'') against France in May 1674.

On 23 August 1674, therefore, a 20,000 strong Brandenburg army marched out again from the Margraviate of Brandenburg heading for Strasbourg. Elector Frederick William and Electoral Prince Charles Emil of Brandenburg accompanied this army. John George II of Anhalt-Dessau was appointed '' Statthalter'' ("Governor") of Brandenburg.

Through bribes and by promising subsidies

A subsidy or government incentive is a form of financial aid or support extended to an economic sector (business, or individual) generally with the aim of promoting economic and social policy. Although commonly extended from the government, the ter ...

France now succeeded in persuading its traditional allies, Sweden, which had only escaped losing all of Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to t ...

with France's intervention in the Treaty of Oliva

The Treaty or Peace of Oliva of 23 April (OS)/3 May (NS) 1660Evans (2008), p.55 ( pl, Pokój Oliwski, sv, Freden i Oliva, german: Vertrag von Oliva) was one of the peace treaties ending the Second Northern War (1655-1660).Frost (2000), p.183 ...

in 1660, to enter the war against Brandenburg. The decisive factor was the concern of the Swedish royal court that a French defeat would result in the political isolation of Sweden. The goal of Sweden's entry into the war was to occupy the undefended state of Brandenburg

Brandenburg (; nds, Brannenborg; dsb, Bramborska ) is a state in the northeast of Germany bordering the states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony, as well as the country of Poland. With an area of 29,480 square ...

in order to force Brandenburg-Prussia to withdraw its troops from war zones in the Upper Rhine and the Alsace

Alsace (, ; ; Low Alemannic German/ gsw-FR, Elsàss ; german: Elsass ; la, Alsatia) is a cultural region and a territorial collectivity in eastern France, on the west bank of the upper Rhine next to Germany and Switzerland. In 2020, it ha ...

.

Preparations for war

The Swedes then began to assemble an invasion force in

The Swedes then began to assemble an invasion force in Swedish Pomerania

Swedish Pomerania ( sv, Svenska Pommern; german: Schwedisch-Pommern) was a dominion under the Swedish Crown from 1630 to 1815 on what is now the Baltic coast of Germany and Poland. Following the Polish War and the Thirty Years' War, Sweden hel ...

. From September more and more reports of these troops movements were received in Berlin. In particular, the Governor of Brandenburg notified his Elector in early September of a conversation with the Swedish envoy, Wangelin, in which he had announced that about 20,000 Swedish troops would be available in Pomerania before the end of the month.Michael Rohrschneider: ''Johann Georg II. von Anhalt-Dessau (1627–1693). Eine politische Biographie'', p. 233 The news of an impending attack by the Swedish army grew stronger when, in the second half of October, the arrival in Wolgast

Wolgast (; csb, Wòłogòszcz) is a town in the district of Vorpommern-Greifswald, in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany. It is situated on the bank of the river (or strait) Peenestrom, vis-a-vis the island of Usedom on the Baltic Sea, Baltic coast ...

of the Swedish commander-in-chief, Carl Gustav Wrangel, was reported.

John George II of Anhalt-Dessau, clearly troubled by news of the troop build-up, asked Field Marshal Carl Gustav Wrangel several times in late October, through Brandenburg colonel, Mikrander for the reasons for these troop movements. Wrangel, however, failed to answer and refused another attempt at dialogue by the Prince of AnhaltSamuel Buchholz:''Versuch einer Geschichte der Churmark Brandenburg'', Vierter Teil: neue Geschichte, p. 92 In mid-November the governor, John George II, had received assurance of an impending Swedish invasion, but in Berlin the exact causes and motives for such imminent aggression remained unclear.Michael Rohrschneider: ''Johann Georg II. von Anhalt-Dessau (1627–1693). Eine politische Biographie'', p. 238

In spite of the disturbing news coming from Berlin, Elector Frederick William himself did not believe that there was an imminent Swedish invasion of the Margraviate of Brandenburg. He expressed this in a letter to the Governor of Brandenburg on 31 October 1674, which stated: "I consider the Swedes better than that and do not think they will do such a dastardly thing."

The strength of the assembled Swedish invasion army in Swedish Pomerania before they entered the Uckermark at the end of December 1674 was, according to the contemporary sources in the '' Theatrum Europaeum'' as follows:

* Infantry: eleven regiments with a total of 7,620 men.Anonym: '' Theatrum Europaeum'', Vol. 11, p. 566

* Cavalry: eight regiments, totalling 6,080 men.

* Artillery: 15 cannon of various calibres.

The forces available on 23 August 1674 to defend the Margraviate of Brandenburg, following the departure of its main army for Alsace, were pitiful. The Elector had few soldiers, and they were mainly old or disabled. The few combat-capable units at his disposal were stationed in fortresses as garrison troops. The overal strength of the garrison troops that the Governor had at his disposal at the end of August 1674 was only around 3,000 men. In the capital city, Berlin, there were at the time only 500 older soldiers, left behind due to their limited fighting ability, and 300 new recruits.Michael Rohrschneider: ''Johann Georg II. von Anhalt-Dessau (1627–1693). Eine politische Biographie'', p. 234 The recruitment of fresh troops had therefore to be enforced immediately. In addition, the Elector ordered the Governor to issue a general call up to the rural population and the towns and cities, in order to compensate for the lack of trained soldiers. The so-called ''Landvolkaufgebot'' ("people's call up") went back to medieval legal standards in the state of Brandenburg, by which farmers and citizens could be used in case of need for local defence. But only after protracted negotiations between the Imperial Estate

An Imperial State or Imperial Estate ( la, Status Imperii; german: Reichsstand, plural: ') was a part of the Holy Roman Empire with representation and the right to vote in the Imperial Diet ('). Rulers of these Estates were able to exercise si ...

s, towns and cities on the one hand and the privy councillors

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

and the Governor on the other hand did the state succeed at the end of December 1674 in enforcing the call up. Most of this edict was applied in the ''residenz

Residenz () is a German word for "place of living", now obsolete except in the formal sense of an official residence. A related term, Residenzstadt, denotes a city where a sovereign ruler resided, therefore carrying a similar meaning as the modern ...

'' towns of Cölln

Cölln () was the twin city of Old Berlin ( Altberlin) from the 13th century to the 18th century. Cölln was located on the Fisher Island section of Spree Island, opposite Altberlin on the western bank of the River Spree, until the cities ...

, Berlin and Friedrichswerder (8 companies of 1,300 men). It was also successfully employed in the Altmark :''See German tanker Altmark for the ship named after Altmark and Stary Targ for the Polish village named Altmark in German.''

The (English: Old MarchHansard, ''The Parliamentary Debates from the Year 1803 to the Present Time ...'', Volume 32. ...

to mobilize farmers and heathland rangers (mounted forestry personnel familiar with the terrain) and for defence. The governor received more reinforcements at the end of January 1675 through the dispatch of troops from the Westphalian provinces.

Course of the campaign

Swedish invasion – Occupation of the Margraviate (25 December 1674 – April 1675)

On 15/25 December 1674 Swedish troops marched throughPasewalk

Pasewalk () is a town in the Vorpommern-Greifswald district, in the state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern in Germany. Located on the Uecker river, it is the capital of the former Uecker-Randow district, and the seat of the Uecker-Randow-Tal ''Amt'', ...

and invaded the Uckermark

The Uckermark () is a historical region in northeastern Germany, straddles the Uckermark District of Brandenburg and the Vorpommern-Greifswald District of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. Its traditional capital is Prenzlau.

Geography

The region is ...

without a formal declaration of war. In fact, according to a message from the Swedish field marshal, Carl Gustav Wrangel, to the Brandenburg envoy, Dubislav von Hagen, on 20/30 December 1674, the Swedish Army would leave the Mark of Brandenburg as soon as Brandenburg ended its state of war with France. A complete break of relations between Sweden and Brandenburg was not intended however.Michael Rohrschneider: ''Johann Georg II. von Anhalt-Dessau (1627–1693). Eine politische Biographie'', p. 239

Figures relating the initial strength of this army, almost half of which was to consist of Germans by spring, vary in the sources between 13,700 and 16,000 men and 30 guns.

To support Field Marshal Carl Gustav Wrangel, who was over 60 years old, often bedridden and suffering from gout

Gout ( ) is a form of inflammatory arthritis characterized by recurrent attacks of a red, tender, hot and swollen joint, caused by deposition of monosodium urate monohydrate crystals. Pain typically comes on rapidly, reaching maximal intens ...

, field marshals Simon Grundel-Helmfelt

Baron Simon Grundel-Helmfelt (1617–1677) was a Swedish field marshal and governor.Alf ÅbergSimon Grundel-Helmfelt Riksarkivet.se, retrieved 28 August 2013 Helmfelt is most notable for his overwhelming victory at the Battle of Lund despite ...

and Otto Wilhelm von Königsmarck were appointed alongside him. However, this unclear assignment prevented, ''inter alia'', clear orders being issued, so that directions for the movement of the army were only put into effect very slowly.Friedrich Ferdinand Carlson, ''Geschichte Schwedens – bis zum Reichstage 1680.'' p. 603

The entry of Sweden into the war attracted the general attention of European powers. The military glory of the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of battl ...

had made the military power of Sweden seem overpowering in the eyes of her contemporaries. German mercenaries willingly offered their services to the Swedes. Some German states (Bavaria, the Electorate of Saxony

The Electorate of Saxony, also known as Electoral Saxony (German: or ), was a territory of the Holy Roman Empire from 1356–1806. It was centered around the cities of Dresden, Leipzig and Chemnitz.

In the Golden Bull of 1356, Emperor Charl ...

, Hanover, and the Bishopric of Münster

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associate ...

) agreed to join the Swedish–French alliance.Friedrich Ferdinand Carlson, ''Geschichte Schwedens – bis zum Reichstage 1680.'' p. 602

The Swedish Army established its headquarters at Prenzlau

Prenzlau (, formerly also Prenzlow) is a town in Brandenburg, Germany, the administrative seat of Uckermark District. It is also the centre of the historic Uckermark region.

Geography

The town is located on the Ucker river, about north of Berl ...

. It was joined there another department, established in Swedish Bremen-Verden

), which is a public-law corporation established in 1865 succeeding the estates of the Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen (established in 1397), now providing the local fire insurance in the shown area and supporting with its surplusses cultural effor ...

, under General Dalwig.

At the same time, after the defeat of imperial Brandenburg in the Battle of Turckheim

The Battle of Turckheim was a battle during the Franco-Dutch War that occurred on 5 January 1675 at a site between the towns of Colmar and Turckheim in Alsace. The French army, commanded by the Viscount of Turenne, defeated the armies of Austri ...

against the French on 26 December 1674, Brandenburg's main army marched to its winter quarters in and around Schweinfurt

Schweinfurt ( , ; ) is a city in the district of Lower Franconia in Bavaria, Germany. It is the administrative centre of the surrounding district (''Landkreis'') of Schweinfurt and a major industrial, cultural and educational hub. The urban a ...

, reaching the area on 31 January 1675. Because of wintry weather and the losses he had suffered, the Elector decided that he would not deploy his main army immediately on a new campaign in the Uckermark. Friedrich Förster, ''Friedrich Wilhelm, der grosse Kurfürst, und seine Zeit'', p. 131 In addition, a sudden withdrawal from the western theatre of war would have alarmed Brandenburg-Prussia's allies – thus achieving the ultimate goal of the Swedish invasion, i.e. to force Brandenburg to withdraw from the war with France.

Without further reinforcements the open regions of the Neumark

The Neumark (), also known as the New March ( pl, Nowa Marchia) or as East Brandenburg (), was a region of the Margraviate of Brandenburg and its successors located east of the Oder River in territory which became part of Poland in 1945.

Cal ...

east of the Oder and Farther Pomerania

Farther Pomerania, Hinder Pomerania, Rear Pomerania or Eastern Pomerania (german: Hinterpommern, Ostpommern), is the part of Pomerania which comprised the eastern part of the Duchy and later Province of Pomerania. It stretched roughly from the ...

could not be held by Brandenburg, except at a few fortified locations. The Mittelmark, by contrast, could be held with relatively few troops, because to the north there were only a few easily defended passes, near Oranienburg, Kremmen, Fehrbellin

Fehrbellin is a municipality in Germany, located 60 km NW of Berlin. It had 9,310 inhabitants as of 2005, but has since declined to 8,606 inhabitants in 2012.

History

In 1675, the Battle of Fehrbellin was fought there, in which the troops of ...

and Friesack

Friesack (; also Friesack/Mark) is a town in the Havelland district, in Brandenburg, Germany. It is situated northeast of Rathenow, and southwest of Neuruppin

Neuruppin (; North Brandenburgisch: ''Reppin'') is a town in Brandenburg, Germany, ...

, through the marshlands of the Havelland Luch

The Havelland Luch (german: Havelländisches Luch) is a lowland area inside a bend of the River Havel west of Berlin, and forms the heart of the Havelland region.

Location

The '' luch'', a former marshland, lies in a basin that is part of ...

and the Rhinluch. In the east, the March was covered by the river course of the Oder. The few available Brandenburg soldiers were recalled to fortified locations. In this way, as a result of the prevailing circumstances, Brandenburg's defences were formed along the line from Köpenick

Köpenick () is a historic town and locality (''Ortsteil'') in Berlin, situated at the confluence of the rivers Dahme and Spree in the south-east of the German capital. It was formerly known as Copanic and then Cöpenick, only officially adop ...

, via Berlin, Spandau

Spandau () is the westernmost of the 12 boroughs () of Berlin, situated at the confluence of the Havel and Spree rivers and extending along the western bank of the Havel. It is the smallest borough by population, but the fourth largest by la ...

, Oranienburg, Kremmen, Fehrbellin and Havelberg to the River Elbe

The Elbe (; cs, Labe ; nds, Ilv or ''Elv''; Upper and dsb, Łobjo) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Rep ...

. In addition the garrison of Spandau Fortress was reinforced from 250 to 800 men; it also had 24 cannon of varying calibres. In Berlin the garrison was increased to 5,000 men, including the ("dragoon bodyguard") dispatched by the Elector from Franconia and the reinforcements sent from the province of Westphalia at the end of January.

The Swedes, however, remained inactive and failed to take advantage of the absence of the Brandenburg army and occupy wide areas of the Margraviate of Brandenburg. They focused first – whilst maintaining strict discipline – on the levying of war contributions and on building up the army to 20,000 by recruiting mercenaries

A mercenary, sometimes also known as a soldier of fortune or hired gun, is a private individual, particularly a soldier, that joins a military conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any ...

. This inaction was partially due to the internal political conflict between the old and the new government of Sweden, which prevented clear military aims being set. Contradictory orders were issued; command was soon followed by counter-command.

At the end of January 1675, Carl Gustav Wrangel assembled his forces near Prenzlau and, on 4 February, crossed the Oder with his main body heading for Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to t ...

and Neumark

The Neumark (), also known as the New March ( pl, Nowa Marchia) or as East Brandenburg (), was a region of the Margraviate of Brandenburg and its successors located east of the Oder River in territory which became part of Poland in 1945.

Cal ...

. Swedish troops occupied Stargard in Pommern, Landsberg, Neustettin, Kossen, and Züllichau in order to recruit there as well. Farther Pomerania was occupied as far as Lauenburg

Lauenburg (), or Lauenburg an der Elbe ( en, Lauenberg on the Elbe), is a town in the state of Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. It is situated on the northern bank of the river Elbe, east of Hamburg. It is the southernmost town of Schleswig-Holstein ...

and several smaller places. Then Wrangel settled the Swedish army into winter quarters in Pomerania and the Neumark.

When it became clear in the early spring that Brandenburg-Prussia would not withdraw from the war, the Swedish court in Stockholm issued the order for a stricter regime of occupation to be enforced in order to raise pressure on the Elector to pull out of the war. This change in Swedish occupation policy followed swiftly, with the result that repression of the state and the civilian population increased sharply. Several contemporary chroniclers described these excesses as worse, both in extent and brutality, than during the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of battl ...

. There was no significant fighting, however, until spring 1675. The of the March of Brandenburg, John George II of Anhalt-Dessau, described this state of limbo in a letter to the Elector on 24 March/3 April 1675 as "neither peace nor war".

Swedish spring campaign (early May 1675 – 25 June 1675)

The French envoy in Stockholm demanded on 20/30 March that the Swedish Army extend its occupation toSilesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is spli ...

and conduct itself in agreement with French plans. The French position changed, however, in the weeks that followed and gave the Swedes more leeway in decision making in this theatre. However the envoy in Stockholm expressed concern due to the alleged failure of the Swedish troops.Friedrich Ferdinand Carlson, ''Geschichte Schwedens – bis zum Reichstage 1680.'' p. 604

In early May 1675 the Swedes began the spring campaign that had been strongly urged by the French. Its aim was to cross the Elbe

The Elbe (; cs, Labe ; nds, Ilv or ''Elv''; Upper and dsb, Łobjo) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Rep ...

to link up with Swedish forces in Bremen-Verden and the 13,000 strong army of their ally, John Frederick, Duke of Brunswick and Lunenburg, in order to cut the approach route of the Elector and his army into Brandenburg. So an army that had now grown to 20,000 men and 64 cannon entered the Uckermark, passing through Stettin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the German border, it is a major s ...

. Although the capability of the Swedish Army was not comparable to that of earlier times, the former view of Sweden's military might remained. This led, not least, to rapid early success. The first fighting took place in the region of Löcknitz where, on 5/15 May 1675, the fortified castle held by a 180-man garrison under Colonel Götz was surrendered after a day's shelling to the Swedish Army under the command of Jobst Sigismund, in return for free passage to Oderburg. As a result, Götz was later sentenced to death by a court martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of me ...

and executed on 24 March 1676.

Following the capture of Löcknitz, the Swedes pushed rapidly south and occupied Neustadt, Wriezen and Bernau. Their next objective was the Rhinluch, which was only passable in a few places. These had been occupied by Brandenburg with militia (), armed farmers and heath rangers () as a precaution. The governor () sent troops from Berlin and six cannon as reinforcements under the command of Major General von Sommerfeld in order to be able to mount a coordinated defence of the passes at Oranienburg, Kremmen and Fehrbellin.

The Swedes advanced on the Rhin line in three columns: the first, under General Stahl, against Oranienburg; the second, under General Dalwig, against Kremmen; and the third, which at 2,000 men was the strongest, under General Groothausen, against Fehrbellin. There was heavy fighting for the river crossing for several days in front of Fehrbellin. Because the Swedes did not succeed in breaking through here, the column diverted to Oranienburg, where, thanks to advice from local farmers, a crossing had been found which enabled about 2,000 Swedes to press on to the south. As a consequence, the positions on either side at Kremmen, Oranienburg and Fehrbellin had to be abandoned by Brandenburg.

Shortly thereafter, the Swedes mounted an unsuccessful storming of Spandau Fortress. The whole Havelland was now occupied by the Swedes, whose headquarters was initially established in the town of Brandenburg

Brandenburg (; nds, Brannenborg; dsb, Bramborska ) is a state in the northeast of Germany bordering the states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony, as well as the country of Poland. With an area of 29,480 square ...

. After the capture of Havelberg

Havelberg () is a town in the district of Stendal, in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. It is situated on the Havel, and part of the town is built on an island in the centre of the river. The two parts were incorporated as a town in 1875. It has a populati ...

the Swedish HQ was moved to Rheinsberg

Rheinsberg () is a town and a municipality in the Ostprignitz-Ruppin district, in Brandenburg, Germany. It is located on lake and the river Rhin, approximately 20 km north-east of Neuruppin and 75 km north-west of Berlin.

History

...

on 8/18 June.

Field Marshal Carl Gustav Wrangel, who left Stettin on 26 May/6 June to follow the army, only made it as far Neubrandenburg

Neubrandenburg (lit. ''New Brandenburg'', ) is a city in the southeast of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany. It is located on the shore of a lake called Tollensesee and forms the urban centre of the Mecklenburg Lakeland.

The city is famous for i ...

, because a severe attack of gout left him bedridden for 10 days. Overall command was devolved to Lieutenant General Wolmar Wrangel Waldemar Wrangel af Lindeberg (1641–1675) was a Sweden, Swedish baron (''Friherre'') and soldier. He was the step-brother of ''Lord High Admiral of Sweden, Riksamiral'' Carl Gustaf Wrangel. Also known as "Wolmar", he was married to Christina of Va ...

. To make matters worse, disunity broke out amongst the generals, resulting in general discipline in the army being lost and serious plundering and other abuses by the soldiery against the civil population took place. So that the troops could continue to be supplied with the necessary food and provision, their quarters were widely separated. As a result of this interruption the Swedes lost two valuable weeks in crossing the Elbe.

Sick and borne on a sedan chair, Field Marshal Carl Gustav Wrangel finally reached Neuruppin

Neuruppin (; North Brandenburgisch: ''Reppin'') is a town in Brandenburg, Germany, the administrative seat of Ostprignitz-Ruppin district. It is the birthplace of the novelist Theodor Fontane (1819–1898) and therefore also referred to as ''Fon ...

on 9/19 June. He immediately banned all looting and ordered reconnaissance detachments to be sent towards Magdeburg. On 11/21 June, he set out with a regiment of infantry and two cavalry regiments (1,500 horse) for Havelberg

Havelberg () is a town in the district of Stendal, in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. It is situated on the Havel, and part of the town is built on an island in the centre of the river. The two parts were incorporated as a town in 1875. It has a populati ...

, which he reached the following day in order to occupy the Altmark :''See German tanker Altmark for the ship named after Altmark and Stary Targ for the Polish village named Altmark in German.''

The (English: Old MarchHansard, ''The Parliamentary Debates from the Year 1803 to the Present Time ...'', Volume 32. ...

that summer. To that end, he had all available craft assembled on the River Havel in order to construct a pontoon bridge

A pontoon bridge (or ponton bridge), also known as a floating bridge, uses floats or shallow- draft boats to support a continuous deck for pedestrian and vehicle travel. The buoyancy of the supports limits the maximum load that they can carry. ...

across the Elbe.

At the same time he gave orders

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* Heterarchy, a system of organization wherein the elements have the potential to be ranked a number of ...

to his stepbrother, Lieutenant General Wolmar Wrangel, to bring up the main army and advance with him over the bridge at Rathenow towards Havelberg.Friedrich Ferdinand Carlson, ''Geschichte Schwedens – bis zum Reichstage 1680.'' p. 605 Lieutenant General Wrangel, commander-in-chief of the main body, under whose command were some 12,000 men, was at this time in the city of Brandenburg an der Havel. The communication link between Havelberg and Brandenburg an der Havel was held by just one regiment at Rathenow. This flank, secured only by a small force, offered a good point of attack for an enemy advancing from the west. At this time, on 21 June, a majority of the March of Brandenburg was in Swedish hands. However, the planned Swedish crossing of the Elbe at Havelberg on 27 June never came to fruition.

In the meantime, Elector of Brandenburg Frederick William tried to secure allies, knowing full well that the national forces at his disposal were, on their own, not sufficient for a campaign against the military might of Sweden. For this purpose, he went on 9 March for talks at The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a list of cities in the Netherlands by province, city and municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's ad ...

, which he reached on 3 May. The negotiations and necessary appointments with the friendly powers gathered there lasted until 20 May. As a result, Holland and Spain declared war on Sweden at the urging of the Elector. Apart from that, he received no concrete assistance from the Holy Roman Empire or Denmark, whereupon the Elector decided to retake the March of Brandenburg from the Swedes without assistance. On 6 June 1675 he held a military parade

A military parade is a formation of soldiers whose movement is restricted by close-order manoeuvering known as drilling or marching. The military parade is now almost entirely ceremonial, though soldiers from time immemorial up until the lat ...

and had the army break camp from its quarters on the River Main. The advance of the 15,000 strong army to Magdeburg was undertaken in three columns.

Campaign by Elector Frederick William (23–29 June 1675)

On 21 June the Brandenburg army reached Magdeburg. As a result of inadequate reconnaissance the arrival of Brandenburg appeared not to have been noticed by the Swedes, and so Frederick William adopted security measures to protect this tactical advantage. Not until he reached Magdeburg did he receive accurate information about the local situation. From intercepted letters, it appeared that Swedish and Hanoverian troops were about to join forces and attack the fortress of Magdeburg. After holding a military council, the Elector decided to break through the line of the Havel that the Swedes had now reached at their weakest point, at Rathenow. His intent was to separate the two parts of the Swedish army at Havelberg and the city of Brandenburg from one another.

On the morning of 23 June, around 3 a.m., the army set out from Magdeburg. Since the success of the plan depended on the element of surprise, the Elector advanced only with his cavalry, which consisted of 5,000 troopers in 30 squadrons and 600 dragoons. In addition there were 1,350

On 21 June the Brandenburg army reached Magdeburg. As a result of inadequate reconnaissance the arrival of Brandenburg appeared not to have been noticed by the Swedes, and so Frederick William adopted security measures to protect this tactical advantage. Not until he reached Magdeburg did he receive accurate information about the local situation. From intercepted letters, it appeared that Swedish and Hanoverian troops were about to join forces and attack the fortress of Magdeburg. After holding a military council, the Elector decided to break through the line of the Havel that the Swedes had now reached at their weakest point, at Rathenow. His intent was to separate the two parts of the Swedish army at Havelberg and the city of Brandenburg from one another.

On the morning of 23 June, around 3 a.m., the army set out from Magdeburg. Since the success of the plan depended on the element of surprise, the Elector advanced only with his cavalry, which consisted of 5,000 troopers in 30 squadrons and 600 dragoons. In addition there were 1,350 musketeer

A musketeer (french: mousquetaire) was a type of soldier equipped with a musket. Musketeers were an important part of early modern warfare particularly in Europe as they normally comprised the majority of their infantry. The musketeer was a pre ...

s who were transported on wagons to ensure their mobility. The artillery comprised 14 guns of various calibres. This army was led by the Elector and the already 69-year-old Field Marshal Georg von Derfflinger

Georg von Derfflinger (20 March 1606 – 14 February 1695) was a field marshal in the army of Brandenburg-Prussia during and after the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648).

Early years

Born 1606 at Neuhofen an der Krems in Austria, into a family ...

. The cavalry was under the command of General of Cavalry Frederick, Landgrave of Hesse-Homburg, Lieutenant General of Görztke and Major General Lüdeke. The infantry was commanded by two major-generals, von Götze and von Pöllnitz.

On 25 June 1675 the Brandenburg army reached Rathenow. Under the personal guidance of Brandenburg's Field Marshal Georg von Derfflinger

Georg von Derfflinger (20 March 1606 – 14 February 1695) was a field marshal in the army of Brandenburg-Prussia during and after the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648).

Early years

Born 1606 at Neuhofen an der Krems in Austria, into a family ...

, they succeeded in defeating the Swedish garrison consisting of six companies of dragoons in bloody street fighting

Street fighting is hand-to-hand combat in public places, between individuals or groups of people. The venue is usually a public place (e.g. a street) and the fight sometimes results in serious injury or occasionally even death. Some street fig ...

.

That same day the Swedish main army marched from Brandenburg an der Havel to Havelberg

Havelberg () is a town in the district of Stendal, in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. It is situated on the Havel, and part of the town is built on an island in the centre of the river. The two parts were incorporated as a town in 1875. It has a populati ...

, where the crossing of the Elbe was to take place. But the overall strategic situation had changed dramatically because of the recapture of this important position. The ensuing separation of the two Swedish armies, who were caught entirely by surprise, meant that a crossing of the Elbe at Havelber was no longer possible. Field Marshal Carl Gustav Wrangel, who was in Havelberg at an undefended location and without supplies, now gave the main Swedish army under Wolmar Wrangel the command to join him via Fehrbellin. So in order to unite his troops with the main army Field Marshal Carl Gustav Wrangel left for Neustadt on 16/26 June.

The Swedish headquarters appears to have been completely unaware of the actual location and the strength of the Brandenburg army. Lieutenant General Wolmar Wrangel now retired rapidly north to secure his lines of communication and, as ordered, to unite with the now separated Swedish advance guard. The location of Sweden at the fall of Rathenow on 25 June/5 July was Pritzerbe. From here there were only 2 exit routes because of the peculiar natural features in the March of Brandenburg at that time. The shorter passage was, however, threatened by the Brandenburg troops and the road conditions were considered to be extremely difficult. So the Swedes decided to use the route via Nauen

Nauen is a small town in the Havelland district, in Brandenburg, Germany. It is chiefly known for Nauen Transmitter Station, the world's oldest preserved radio transmitting installation.

Geography

Nauen is situated within the Havelland Luch g ...

, where they could branch out from a) Fehrbellin

Fehrbellin is a municipality in Germany, located 60 km NW of Berlin. It had 9,310 inhabitants as of 2005, but has since declined to 8,606 inhabitants in 2012.

History

In 1675, the Battle of Fehrbellin was fought there, in which the troops of ...

to Neuruppin

Neuruppin (; North Brandenburgisch: ''Reppin'') is a town in Brandenburg, Germany, the administrative seat of Ostprignitz-Ruppin district. It is the birthplace of the novelist Theodor Fontane (1819–1898) and therefore also referred to as ''Fon ...

, b) Kremmen to Gransee and c) Oranienburg to Prenzlau

Prenzlau (, formerly also Prenzlow) is a town in Brandenburg, Germany, the administrative seat of Uckermark District. It is also the centre of the historic Uckermark region.

Geography

The town is located on the Ucker river, about north of Berl ...

.

However, since both Oranienburg and Kremmen appeared to the Swedes to be occupied by the enemy, the only option open to them was to retreat via Nauen to Fehrbellin. Early on, the Swedish general sent an advance party of 160 cavalry to secure the passage of Fehrbellin.

The Elector immediately divided his force into three to block the only three passes. The first division under Lieutenant Colonel Hennig was dispatched to Fehrbellin, the second under Adjutant General Kunowski was sent to Kremmen, the third under the command of Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

() Zabelitz was deployed to Oranienburg. They had the task, with the help of expert local hunters, of getting to the exits to the Havelland Luch swamps ahead of the Swedes, using little known routes through rough terrain. There, the bridges were to be destroyed and the roads made impassable. For this purpose, these exits were to be defended by an armed militia group and by hunters.

Details are only available for the first troop of Lieutenant Colonel Hennig's division. This sub-unit of 100 cuirassiers and 20 dragoons, guided by an experienced local forester, rode through the Rhinfurt at Landin and thence to Fehrbellin. Once there, taking advantage of the element of surprise, they attacked the contingent of 160 Swedish cuirassiers manning the fieldworks guarding the causeway. In this battle, about 50 Swedes were killed A captain, a lieutenant and eight soldiers were captured, the rest escaping with their commander, Lieutenant Colonel Tropp, leaving their horses behind. Brandenburg lost 10 troopers. The Brandenburg soldiers then set fire to the two Rhin bridges on the causeway. Then the causeway itself was also breached in order to cut off the Swedes' avenue of retreat to the north.

Battle of Nauen

The Skirmish at Nauen (german: Gefecht bei Nauen or ''Duell vor Nauen''), took place on near the town of Nauen between the vanguard of the Brandenburg-Prussian army and Swedish rearguard units during the Swedish-Brandenburg War.

The engagement ...

, which ended with the recapture of the town. By evening, the two main armies were drawn up opposite one another in battle formation. However, the Swedish position appeared too strong for a successful attack by Brandenburg and the Brandenburg troops were exhausted by having to undertake forced marches in the days beforehand. So the Elector's orders were to withdraw into or behind the town of Nauen and make camp there. On the Brandenburg side the expectation was that they would begin engaging the next morning at the gates of Nauen in the decisive battle. The Swedes, however, took advantage of the cover of night to retreat towards Fehrbellin. From the beginning of their withdrawal on 25 June until after the battle at Nauen on 27 June, the Swedes lost a total of about 600 men during their retreat and another 600 were taken prisoner.

As the causeway and the bridge over the Rhin had been destroyed the day before by the Brandenburg raid, Sweden were forced to participate in the decisive battle. Lieutenant General Wolmar Wrangel had 11,000–12,000 men and seven cannon at his disposal.

The Swedes were disastrously defeated in this well-known engagement known as the Battle of Fehrbellin

The Battle of Fehrbellin was fought on June 18, 1675 (Julian calendar date, June 28th, Gregorian), between Swedish and Brandenburg-Prussian troops. The Swedes, under Count Waldemar von Wrangel (stepbrother of '' Riksamiral'' Carl Gustaf Wrange ...

, but succeeded under cover of night in crossing of the restored bridge. But their losses increased significantly during the retreat through the Prignitz

Prignitz () is a ''Kreis'' (district) in the northwestern part of Brandenburg, Germany. Neighboring are (from the north clockwise) the district Ludwigslust-Parchim in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, the district Ostprignitz-Ruppin in Brandenburg, t ...

and Mecklenburg

Mecklenburg (; nds, label=Low German, Mękel(n)borg ) is a historical region in northern Germany comprising the western and larger part of the federal-state Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. The largest cities of the region are Rostock, Schwer ...

. During the battle and subsequent rout 2,400 Swedish troops were killed, and 300 to 400 captured, whilst Brandenburg lost 500 men killed or wounded.Frank Bauer. ''Fehrbellin 1675. Brandenburg-Preußens Aufbruch zur Großmacht'', p. 131 Not until they reached Wittstock did Brandenburg call off the pursuit.

Consequences

The Swedish army had suffered a crushing defeat and, particularly as a result of their defeat at Fehrbellin, lost their hitherto perceived aura of invincibility. The remnants of the army found themselves back on Swedish territory in Pomerania, from where they had started the war. Sweden's overall strategic situation deteriorated further when, during the summer months, Denmark and the Holy Roman Empire declared war on Sweden. Their possessions in North Germany (the bishoprics ofBremen

Bremen (Low German also: ''Breem'' or ''Bräm''), officially the City Municipality of Bremen (german: Stadtgemeinde Bremen, ), is the capital of the Germany, German States of Germany, state Bremen (state), Free Hanseatic City of Bremen (''Freie H ...

and Verden Verden can refer to:

* Verden an der Aller, a town in Lower Saxony, Germany

* Verden, Oklahoma, a small town in the USA

* Verden (district), a district in Lower Saxony, Germany

* Diocese of Verden (768–1648), a former diocese of the Catholic Chur ...

) were suddenly under threat. In the years that followed, Sweden, now forced onto the back foot, had to concentrate on defending its territories in northern Europe against numerous attacks, succeeding in the end only in holding onto Scania

Scania, also known by its native name of Skåne (, ), is the southernmost of the historical provinces (''landskap'') of Sweden. Located in the south tip of the geographical region of Götaland, the province is roughly conterminous with Skå ...

.

France's strategic plan, by contrast, had proved successful: Brandenburg-Prussia was still officially at war with France, but its army had pulled back from the Rhine front and had to concentrate all its further efforts in the war against Sweden.

References

Literature

* Anonym: '' Theatrum Europaeum''. Vol. 11: ''1672–1679''. Merian, Frankfurt am Main, 1682. * Frank Bauer: ''Fehrbellin 1675. Brandenburg-Preußens Aufbruch zur Großmacht''. Vowinckel, Berg am Starnberger See and Potsdam, 1998, . * Samuel Buchholz: ''Versuch einer Geschichte der Churmark Brandenburg von der ersten Erscheinung der deutschen Sennonen an bis auf jetzige Zeiten''. Vol. 4. Birnstiel, Berlin, 1771. * Friedrich Ferdinand Carlson: ''Geschichte Schwedens''. Vol. 4: ''Bis zum Reichstage 1680''. Perthes, Gotha, 1855. * Friedrich Förster: ''Friedrich Wilhelm, der grosse Kurfürst, und seine Zeit. Eine Geschichte des Preussischen Staates während der Dauer seiner Regierung; in biographischen''. In: ''Preußens Helden in Krieg und Frieden''. Vol. 1.1 Hempel, Berlin, 1855. * Curt Jany: ''Geschichte der Preußischen Armee. Vom 15. Jahrhundert–1914''. Vol. 1: ''Von den Anfängen bis 1740''. 2nd expanded edition. Biblio Verlag, Osnabrück, 1967, . * Paul Douglas Lockhart: ''Sweden in the Seventeenth Century''. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke etc., 2004, , (English) * Maren Lorenz: ''Das Rad der Gewalt. Militär und Zivilbevölkerung in Norddeutschland nach dem Dreißigjährigen Krieg (1650–1700)''. Böhlau, Cologne, 2007, . * Martin Philippson: ''Der große Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm von Brandenburg.'' Part III 660 to 1688 In: ''Elibron Classics'', Adamant Media Corporation, Boston, MA, 2005 , (German, reprint of the first edition of 1903 by Siegfried Cronbach in Berlin). * Michael Rohrschneider: '' Johann Georg II. von Anhalt-Dessau (1627–1693). ''Eine politische Biographie. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin, 1998, . * Ralph Tuchtenhagen: ''Kleine Geschichte Schwedens''. 1. Auflage, In: ''Beck’sche Reihe,'' Vol. 1787, Beck, Munich, 2008, . * Matthias Nistahl: Die Reichsexekution gegen Schweden in Bremen Verden, in Heinz-Joachim Schulze, Landschaft und regionale Identität, Stade, 1989 {{DEFAULTSORT:Swedish invasion of 1674 1675 Northern Wars Military history of Sweden Wars involving Brandenburg-Prussia Invasions of the Holy Roman Empire 1670s conflicts 1674 in the Holy Roman Empire 1675 in the Holy Roman EmpireBrandenburg

Brandenburg (; nds, Brannenborg; dsb, Bramborska ) is a state in the northeast of Germany bordering the states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony, as well as the country of Poland. With an area of 29,480 square ...