Student Protests In Canada on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Student activism or campus activism is work by students to cause political, environmental, economic, or social change. Although often focused on schools, curriculum, and educational funding, student groups have influenced greater political events.

Modern student activist movements vary widely in subject, size, and success, with a variety of students in various educational settings participating, including public and private school students; elementary, middle, senior, undergraduate, and graduate students; and all races, socio-economic backgrounds, and political perspectives. Some

Student activism or campus activism is work by students to cause political, environmental, economic, or social change. Although often focused on schools, curriculum, and educational funding, student groups have influenced greater political events.

Modern student activist movements vary widely in subject, size, and success, with a variety of students in various educational settings participating, including public and private school students; elementary, middle, senior, undergraduate, and graduate students; and all races, socio-economic backgrounds, and political perspectives. Some

In

In

In

In

From 2011 to 2013, Chile was rocked by a series of student-led nationwide protests across

From 2011 to 2013, Chile was rocked by a series of student-led nationwide protests across

Government of Chile. July 5, 2011. Accessdate July 5, 2011 and a

Since the defeat of the

Since the defeat of the

During communist rule, students in

During communist rule, students in

In

In

In 1815 in

In 1815 in

The

The  On 16 January 2017 a large group of students (more than 2 million) protested in state of

On 16 January 2017 a large group of students (more than 2 million) protested in state of

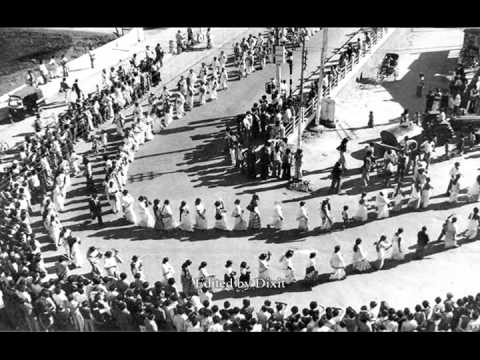

Indonesia is often believed to have hosted "some of the most important acts of student resistance in the world's history". University student groups have repeatedly been the first groups to stage street demonstrations calling for governmental change at key points in the nation's history, and other organizations from across the political spectrum have sought to align themselves with student groups. In 1928, the Youth Pledge (Sumpah Pemuda) helped to give voice to anti-colonial sentiments.

During the political turmoil of the 1960s, right-wing student groups staged demonstrations calling for then-President Sukarno to eliminate alleged Communists from his government, and later demanding that he resign. Sukarno did step down in 1967, and was replaced by Army general Suharto.

Student groups also played a key role in Suharto's 1998 fall by initiating large demonstrations that gave voice to widespread popular discontent with the president in the aftermath of the May 1998 riots of Indonesia, May 1998 riots. High school and university students in Jakarta, Yogyakarta (city), Yogyakarta, Medan, Indonesia, Medan, and elsewhere were some of the first groups willing to speak out publicly against the military government. Student groups were a key part of the political scene during this period. Upon taking office after Suharto stepped down, B. J. Habibie made numerous mostly unsuccessful overtures to placate the student groups that had brought down his predecessor. When that failed, he sent a combined force of police and Preman (Indonesian gangster), gangsters to evict protesters occupying a government building by force. The ensuing carnage left two students dead and 181 injured.

Indonesia is often believed to have hosted "some of the most important acts of student resistance in the world's history". University student groups have repeatedly been the first groups to stage street demonstrations calling for governmental change at key points in the nation's history, and other organizations from across the political spectrum have sought to align themselves with student groups. In 1928, the Youth Pledge (Sumpah Pemuda) helped to give voice to anti-colonial sentiments.

During the political turmoil of the 1960s, right-wing student groups staged demonstrations calling for then-President Sukarno to eliminate alleged Communists from his government, and later demanding that he resign. Sukarno did step down in 1967, and was replaced by Army general Suharto.

Student groups also played a key role in Suharto's 1998 fall by initiating large demonstrations that gave voice to widespread popular discontent with the president in the aftermath of the May 1998 riots of Indonesia, May 1998 riots. High school and university students in Jakarta, Yogyakarta (city), Yogyakarta, Medan, Indonesia, Medan, and elsewhere were some of the first groups willing to speak out publicly against the military government. Student groups were a key part of the political scene during this period. Upon taking office after Suharto stepped down, B. J. Habibie made numerous mostly unsuccessful overtures to placate the student groups that had brought down his predecessor. When that failed, he sent a combined force of police and Preman (Indonesian gangster), gangsters to evict protesters occupying a government building by force. The ensuing carnage left two students dead and 181 injured.

In Iran, students have been at the forefront of protests both against the pre-1979 secular monarchy and, in recent years, against the theocratic islamic republic. Both religious and more moderate students played a major part in Ruhollah Khomeini's opposition network against the Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. In January 1978 the army dispersed demonstrating students and religious leaders, killing several students and sparking a series of widespread protests that ultimately led to the Iranian Revolution the following year. On November 4, 1979, militant Iranian students calling themselves the Muslim Students Following the Line of the Imam seized the United States of America, US embassy in Tehran holding 52 embassy employees hostage for a 444 days (see Iran hostage crisis).

Recent years have seen several incidents when liberal students have clashed with the Iranian government, most notably the Iran student riots, July 1999, Iranian student riots of July 1999. Several people were killed in a week of violent confrontations that started with a police raid on a university dormitory, a response to demonstrations by a group of students of Tehran University against the closure of a reformist newspaper. Akbar Mohammadi (student), Akbar Mohammadi was given a capital punishment, death sentence, later reduced to 15 years in prison, for his role in the protests. In 2006, he died at Evin prison after a hunger strike protesting the refusal to allow him to seek medical treatment for injuries suffered as a result of torture.

At the end of 2002, students held mass demonstrations protesting the death sentence of reformist lecturer Hashem Aghajari for alleged blasphemy. In June 2003, several thousand students took to the streets of Tehran in anti-government protests sparked by government plans to privatise some universities.

In the May 2005 Iranian presidential election, 2005, Iranian presidential election, Iran's largest student organization, The Office to Consolidate Unity, advocated a voting boycott. After the election of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, student protests against the government has continued. In May 2006, up to 40 police officers were injured in clashes with demonstrating students in Tehran. At the same time, the Iranian government has called for student action in line with its own political agenda. In 2006, President Ahmadinejad urged students to organize campaigns to demand that liberal and secular university teachers be removed.

In 2009, after the 2009 Iranian election, disputed presidential election, a series of student protests broke out, which became known as the Iranian Green Movement. The violent measures used by the Iranian government to suppress these protests have been the subject of widespread international condemnation. As a consequence of hash repression, "the student movement entered a period of silence during Government of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (2009–13), Ahmadinejad's second term (2009–2013)".

During Government of Hassan Rouhani (2013–17), the first term of Hassan Rouhani in office (2013-2017) several groups endeavored to revive the student movement through rebuilding student organizations.

In Iran, students have been at the forefront of protests both against the pre-1979 secular monarchy and, in recent years, against the theocratic islamic republic. Both religious and more moderate students played a major part in Ruhollah Khomeini's opposition network against the Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. In January 1978 the army dispersed demonstrating students and religious leaders, killing several students and sparking a series of widespread protests that ultimately led to the Iranian Revolution the following year. On November 4, 1979, militant Iranian students calling themselves the Muslim Students Following the Line of the Imam seized the United States of America, US embassy in Tehran holding 52 embassy employees hostage for a 444 days (see Iran hostage crisis).

Recent years have seen several incidents when liberal students have clashed with the Iranian government, most notably the Iran student riots, July 1999, Iranian student riots of July 1999. Several people were killed in a week of violent confrontations that started with a police raid on a university dormitory, a response to demonstrations by a group of students of Tehran University against the closure of a reformist newspaper. Akbar Mohammadi (student), Akbar Mohammadi was given a capital punishment, death sentence, later reduced to 15 years in prison, for his role in the protests. In 2006, he died at Evin prison after a hunger strike protesting the refusal to allow him to seek medical treatment for injuries suffered as a result of torture.

At the end of 2002, students held mass demonstrations protesting the death sentence of reformist lecturer Hashem Aghajari for alleged blasphemy. In June 2003, several thousand students took to the streets of Tehran in anti-government protests sparked by government plans to privatise some universities.

In the May 2005 Iranian presidential election, 2005, Iranian presidential election, Iran's largest student organization, The Office to Consolidate Unity, advocated a voting boycott. After the election of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, student protests against the government has continued. In May 2006, up to 40 police officers were injured in clashes with demonstrating students in Tehran. At the same time, the Iranian government has called for student action in line with its own political agenda. In 2006, President Ahmadinejad urged students to organize campaigns to demand that liberal and secular university teachers be removed.

In 2009, after the 2009 Iranian election, disputed presidential election, a series of student protests broke out, which became known as the Iranian Green Movement. The violent measures used by the Iranian government to suppress these protests have been the subject of widespread international condemnation. As a consequence of hash repression, "the student movement entered a period of silence during Government of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (2009–13), Ahmadinejad's second term (2009–2013)".

During Government of Hassan Rouhani (2013–17), the first term of Hassan Rouhani in office (2013-2017) several groups endeavored to revive the student movement through rebuilding student organizations.

During the protests of 1968, México, Mexican government killed an estimated 30 to 300 students and civilian protesters. This killing is known as in the

During the protests of 1968, México, Mexican government killed an estimated 30 to 300 students and civilian protesters. This killing is known as in the

In the

In the

Team Enough

which is being overseen by the Brady Campaign, an

Students Demand Action

which is being overseen by Everytown for Gun Safety. Youth activism also became popular for other issues after the March for Our Lives movement, includin

EighteenX18

an organization started by actress Yara Shahidi of Black-ish, ABC's Blacki-sh devoted to increased voter turnout in youth

OneMillionOfUs

a national youth voting and advocacy organization working to educate and empower 1 million young people to vote which started by Jerome Foster II, an

This is Zero Hour

an environmentally-focused youth organization started by Jamie Margolin.

Guide to Social Change Led By and With Young People

Olympia, WA: CommonAction, 2006.

by David Linhardt, The New York Times (NYTimes.com).

from Campus Compact.

Student Activism at Gettysburg College

from Gettysburg College Musselman Library

Women's Protest at Gettysburg College, 1965–1975

from Gettysburg College Musselman Library * Andrews, William. "Dissenting Japan: A History of Japanese Radicalism and Counterculture, from 1945 to Fukushima." London: Hurst, 2016. * Brax, Ralph S. "The first student movement." Port Washington, NY : Kennikat Press, 1980. * Carson, Claybourne. "In Struggle, SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s." Cambridge Massachusetts: Harvard University Press., 1981 * Cohen, Robert. "When the old left was young." New York : Oxford University Press, 1993. * Fletcher, Adam. (2005

HumanLinks Foundation. * Kreider, Aaron ed

"The SEAC Organizing Guide."

Student Environmental Action Coalition, 2004. * Loeb, Paul. "Generation at the Crossroads: Apathy and Action on the American Campus." New Brunswick, N.J. : Rutgers University Press, 1994. * McGhan, Barry

Time Magazine, 1971. * Sale, Kirkpatrick. "SDS: Ten Years Towards a Revolution." New York, Random House, 1973. * Students for a Democratic Society

Author, 1962. * Vellela, Tony. "New Voices: Student Activism in the 80s and 90s." Boston, MA: South End Press, 1988. * Manabu Miyazaki; ''Toppamono: Outlaw. Radical. Suspect. My Life in Japan's Underworld'' (2005, Kotan Publishing, ) * Student Movements in India, An AICUF Publication, Chennai 1999 *Deka, Kaustub

"From Movements to Accords and Beyond : The critical role of student organizations in the formation and performance of identity in Assam"

Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, 2013

This collection contains leaflets and newspapers that were distributed on the University of Washington campus during the decades of the 1960s and 1970s. They reflect the social environment and political activities of the youth movement in Seattle during that period.

Campus Activism

(Networking site with resources for student activists)

Dosomething.org

(Youth Activism Social Networking site) {{DEFAULTSORT:Student Activism Student politics, Activism Social movements

Student activism or campus activism is work by students to cause political, environmental, economic, or social change. Although often focused on schools, curriculum, and educational funding, student groups have influenced greater political events.

Modern student activist movements vary widely in subject, size, and success, with a variety of students in various educational settings participating, including public and private school students; elementary, middle, senior, undergraduate, and graduate students; and all races, socio-economic backgrounds, and political perspectives. Some

Student activism or campus activism is work by students to cause political, environmental, economic, or social change. Although often focused on schools, curriculum, and educational funding, student groups have influenced greater political events.

Modern student activist movements vary widely in subject, size, and success, with a variety of students in various educational settings participating, including public and private school students; elementary, middle, senior, undergraduate, and graduate students; and all races, socio-economic backgrounds, and political perspectives. Some student protests

Campus protest or student protest is a form of student activism that takes the form of protest at university campuses. Such protests encompass a wide range of activities that indicate student dissatisfaction with a given political or acad ...

focus on the internal affairs of a specific institution; others focus on broader issues such as a war or dictatorship

A dictatorship is a form of government which is characterized by a leader, or a group of leaders, which holds governmental powers with few to no limitations on them. The leader of a dictatorship is called a dictator. Politics in a dictatorship a ...

. Likewise, some student protests focus on an institution's impact on the world, such as a disinvestment

Disinvestment refers to the use of a concerted economic boycott to pressure a government, industry, or company towards a change in policy, or in the case of governments, even regime change. The term was first used in the 1980s, most commonly in ...

campaign, while others may focus on a regional or national policy's impact on the institution, such as a campaign against government education policy. Although student activism is commonly associated with left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in so ...

politics, right-wing student movements are not uncommon; for example, large student movements fought on both sides of the apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

struggle in South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring count ...

.

Student activism at the university level is nearly as old as the university

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. ''University'' is derived from the Latin phrase ''universitas magistrorum et scholarium'', which ...

itself. Students in Paris and Bologna staged collective actions as early as the 13th century, chiefly over town and gown

Town and gown are two distinct communities of a university town; 'town' being the non-academic population and 'gown' metonymically being the university community, especially in ancient seats of learning such as Oxford, Cambridge, Durham, and ...

issues. Student protests over broader political issues also have a long pedigree. In Joseon Dynasty

Joseon (; ; Middle Korean: 됴ᇢ〯션〮 Dyǒw syéon or 됴ᇢ〯션〯 Dyǒw syěon), officially the Great Joseon (; ), was the last dynastic kingdom of Korea, lasting just over 500 years. It was founded by Yi Seong-gye in July 1392 and ...

Korea, 150 Sungkyunkwan

Sungkyunkwan was the foremost educational institution in Korea during the late Goryeo and Joseon Dynasties. Today, it sits in its original location, at the south end of the Humanities and Social Sciences Campus of Sungkyunkwan University in Seoul ...

students staged an unprecedented demonstration against the king in 1519 over the Kimyo purge.

Extreme forms of student activism include suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and ...

such as the case of Jan Palach

Jan Palach (; 11 August 1948 – 19 January 1969) was a Czech student of history and political economics at Charles University in Prague. His self-immolation was a political protest against the end of the Prague Spring resulting from the 1968 i ...

's, and Jan Zajíc

Jan Zajíc (July 3, 1950 – February 25, 1969) was a Czech student who committed suicide by self-immolation as a political protest. He was a student of the Střední průmyslová škola železniční (Industrial Highschool of Railways) technic ...

's protests against the end of the Prague Spring

The Prague Spring ( cs, Pražské jaro, sk, Pražská jar) was a period of political liberalization and mass protest in

the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. It began on 5 January 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubček was elected First Se ...

and Kostas Georgakis

Kostas Georgakis ( el, Κώστας Γεωργάκης) (23 August 194819 September 1970) was a Greek student of geology, who in the early hours of 19 September 1970, set himself ablaze in Matteotti square in Genoa in a fatal protest against t ...

' protest against the Greek military junta of 1967–1974

The Greek junta or Regime of the Colonels, . Also known within Greece as just the Junta ( el, η Χούντα, i Choúnta, links=no, ), the Dictatorship ( el, η Δικτατορία, i Diktatoría, links=no, ) or the Seven Years ( el, η Ε ...

.

By country

Argentina

In

In Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, t ...

, as elsewhere in Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived ...

, the tradition of student activism dates back to at least the 19th century, but it was not until after 1900 that it became a major political force. in 1918 student activism triggered a general modernization of the universities especially tending towards democratization, called the University Revolution

The Argentine university reform of 1918 was a general modernization of the universities, especially tending towards democratization, brought about by student activism during the presidency of Hipolito Yrigoyen, the first democratic government. Th ...

(Spanish: ''revolución universitaria''). The events started in Córdoba Córdoba most commonly refers to:

* Córdoba, Spain, a major city in southern Spain and formerly the imperial capital of Islamic Spain

* Córdoba, Argentina, 2nd largest city in the country and capital of Córdoba Province

Córdoba or Cordoba may ...

and were accompanied by similar uprisings across Latin America.

Australia

Australian Students have a long history of being active in political debates. This is particularly true in the newer universities that have been established in suburban areas. For much of the 20th century, the major campus organizing group across Australia was theAustralian Union of Students

The Australian Union of Students (AUS), formerly National Union of Australian University Students (NUAUS), was a representative body and lobby group for Australian university and college of advanced education students. It collapsed in 1984 and ...

, which was founded in 1937 as the Union of Australian University Students. The AUS folded in 1984. It was replaced by the National Union of Students in 1987.

Bangladesh

Student politics of Bangladesh is reactive, confrontational and violent. Student organizations act as the armament of the political parties they are part of. Over the years, political clashes and factional feuds in the educational institutes killed many, seriously hampering the academic atmosphere. To check those hitches, universities have no options but go to lengthy and unexpected closures. Therefore, classes are not completed on time and there are session jams. The student wings of ruling parties dominate the campuses and residential halls through crime and violence to enjoy various unauthorized facilities. They control the residential halls to manage seats in favor of their party members and loyal pupils. They eat and buy for free from the restaurants and shops nearby. They extort and grab tenders to earn illicit money. They take money from the freshmen candidates and put pressure on teachers to get an acceptance for them. They take money from the job seekers and put pressures on university administrations to appoint them.Brazil

On August 11, 1937, theUnião Nacional dos Estudantes

The National Union of Students (''União Nacional dos Estudantes'' or UNE) is a student organization in Brazil. Founded on 11 August 1937, it represents more than 5 million students of higher education, and is headquartered in São Paulo, with bra ...

(UNE) was formed as a platform for students to create change in Brazil. The organization tried to unite students from all over Brazil. However, in the 1940s the group had aligned more with socialism. Then in the 1950s the group changed alignment again, this time aligning with more conservative values. The União Metropolitana dos Estudantes rose up in replacement of the once socialist UNE. However, it was not long until União Nacional dos Estudantes once again sided with socialism, thus joining forces with the União Metropolitana dos Estudantes.

The União Nacional dos Estudantes was influential in the democratization of higher education. Their first significant feat occurred during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

when they successfully pressured Brazilian president Getúlio Vargas

Getúlio Dornelles Vargas (; 19 April 1882 – 24 August 1954) was a Brazilian lawyer and politician who served as the 14th and 17th president of Brazil, from 1930 to 1945 and from 1951 to 1954. Due to his long and controversial tenure as Braz ...

to join the side of the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

.

In 1964, UNE was outlawed after elected leader João Goulart

João Belchior Marques Goulart (1 March 1919 – 6 December 1976), commonly known as Jango, was a Brazilian politician who served as the 24th president of Brazil until a military coup d'état deposed him on 1 April 1964. He was considered the ...

was disposed of power by a military coup

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

. The military regime terrorized students in an effort to make them subservient. In 1966, students began protesting anyway despite the reality of further terror.

All the protests led up to the March of the One Hundred Thousand The March of the One Hundred Thousand ( pt, Passeata dos Cem Mil) was a manifestation of popular protest against the Military dictatorship in Brazil, which occurred on June 26, 1968 in Rio de Janeiro, organized by the student movement and with the ...

in June 1968. Organized by the UNE, this protest was the largest yet. A few months later the government passed Institutional Act Number Five

The Ato Institucional Número Cinco – AI-5 ( en, Institutional Act Number Five) was the fifth of seventeen major decrees issued by the military dictatorship in the years following the 1964 coup d'état in Brazil. ''Institutional Acts'' were ...

which officially banned students from any further protest.

Canada

In

In Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tota ...

, New Left

The New Left was a broad political movement mainly in the 1960s and 1970s consisting of activists in the Western world who campaigned for a broad range of social issues such as civil and political rights, environmentalism, feminism, gay rights, ...

student organizations from the late 1950s and 1960s became mainly two: SUPA (Student Union for Peace Action

A student is a person enrolled in a school or other educational institution.

In the United Kingdom and most commonwealth countries, a "student" attends a secondary school or higher (e.g., college or university); those in primary or elementary ...

) and CYC (Company of Young Canadians). SUPA grew out of the CUCND (Combined Universities Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament) in December 1964, at a University of Saskatchewan conference. While CUCND had focused on protest marches, SUPA sought to change Canadian society as a whole. The scope expanded to grass-roots politics in disadvantaged communities and 'consciousness raising' to radicalize and raise awareness of the 'generation gap' experienced by Canadian youth. SUPA was a decentralized organization, rooted in local university campuses. SUPA however disintegrated in late 1967 over debates concerning the role of working class and 'Old Left'. Members moved to the CYC or became active leaders in CUS (Canadian Union of Students), leading the CUS to assume the mantle of New Left student agitation.

In 1968, SDU (Students for a Democratic University) was formed at McGill and Simon Fraser Universities. SFU SDU, originally former SUPA members and New Democratic Youth, absorbed members from the campus Liberal Club and Young Socialists. SDU was prominent in an Administration occupation in 1968, and a student strike in 1969. After the failure of the student strike, SDU broke up. Some members joined the IWW and Yippies (Youth International Party). Other members helped form the Vancouver Liberation Front in 1970. The FLQ (Quebec Liberation Front) was considered a terrorist organization, causing the use of the War Measures Act

The ''War Measures Act'' (french: Loi sur les mesures de guerre; 5 George V, Chap. 2) was a statute of the Parliament of Canada that provided for the declaration of war, invasion, or insurrection, and the types of emergency measures that co ...

after 95 bombings in the October Crisis

The October Crisis (french: Crise d'Octobre) refers to a chain of events that started in October 1970 when members of the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) kidnapped the provincial Labour Minister Pierre Laporte and British diplomat James Cr ...

. This was the only peacetime use of the War Measures Act.

Since the 1970s, PIRGs (Public Interest Research Groups

Public Interest Research Groups (PIRGs) are a federation of U.S. and Canadian non-profit organizations that employ grassroots organizing and direct advocacy on issues such as consumer protection, public health and transportation. The PIRGs are c ...

) have been created as a result of Student Union referendums across Canada in individual provinces. Like their American counterparts, Canadian PIRGs are student directed, run, and funded. Most operate on a consensus decision making

Consensus decision-making or consensus process (often abbreviated to ''consensus'') are group decision-making processes in which participants develop and decide on proposals with the aim, or requirement, of acceptance by all. The focus on es ...

model. Despite efforts at collaboration, Canadian PIRGs are independent of each other.

Anti-Bullying Day

Anti-Bullying Day (or Pink Shirt Day) is an annual event, held in Canada and other parts of the world, where people wear a pink-coloured shirt to stand against bullying.

The initiative was started in Canada, where it is held on the last Wednesd ...

(a.k.a. Pink Shirt Day) was created by high school students David Shepherd, and Travis Price of Berwick, Nova Scotia, and is now celebrated annually across Canada.

In 2012, the Quebec Student Movement

Quebec ( ; )According to the Government of Canada, Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is ...

arose due to an increase of tuition of 75%; that took students out of class and into the streets because that increase did not allow students to comfortably extend their education, because of fear of debt or not having money at all. Following elections that year, premier Jean Charest

John James "Jean" Charest (; born June 24, 1958) is a Canadian lawyer and former politician who served as the 29th premier of Quebec from 2003 to 2012 and the fifth deputy prime minister of Canada in 1993. Charest was elected to the House o ...

promised to repeal anti-assembly laws and cancel the tuition hike.

Chile

From 2011 to 2013, Chile was rocked by a series of student-led nationwide protests across

From 2011 to 2013, Chile was rocked by a series of student-led nationwide protests across Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the eas ...

, demanding a new framework for education in the country, including more direct state participation in secondary education and an end to the existence of profit in higher education. Currently in Chile, only 45% of high school students study in traditional public schools and most universities are also private. No new public universities have been built since the end of the Chilean transition to democracy

The Chilean transition to democracy is the name given to the process of restoration of democracy carried out in Chile after the end of the military dictatorship of Pinochet, in 1990, and particularly to the first two democratic terms that suc ...

in 1990, even though the number of university students has swelled. Beyond the specific demands regarding education, the protests reflected a "deep discontent" among some parts of society with Chile's high level of inequality. Protests have included massive non-violent marches, but also a considerable amount of violence on the part of a side of protestors as well as riot police.

The first clear government response to the protests was a proposal for a new education fundCadena Nacional de Radio y Televisión: Presidente Piñera anunció Gran Acuerdo Nacional por la EducaciónGovernment of Chile. July 5, 2011. Accessdate July 5, 2011 and a

cabinet shuffle

A cabinet reshuffle or shuffle occurs when a head of government rotates or changes the composition of ministers in their cabinet, or when the Head of State changes the head of government and a number of ministers. They are more common in parliam ...

which replaced Minister of Education Joaquín Lavín

Joaquín José Lavín Infante (born 23 October 1953) is a Chilean politician of the Independent Democratic Union (UDI) party and former mayor of Las Condes, in the northeastern zone of Santiago. Formerly Lavín has also been mayor of Santiago ...

http://www.latercera.com/noticia/politica/2011/07/674-380393-9-pinera-opta-por-mantener-a-hinzpeter-incorporar-a-longueira-y-cambiar-de.shtml Canales, Javier. La Tercera

''La Tercera'' ( es, The Third One), formerly known as ''La Tercera de la Hora'' ('the third of the hour'), is a daily newspaper published in Santiago, Chile and owned by Copesa. It is ''El Mercurio''s closest competitor.

''La Tercera'' is part ...

July 18, 2011. Access date July 18, 2011 and was seen as not fundamentally addressing student movement concerns. Other government proposals were also rejected.

China

Since the defeat of the

Since the defeat of the Qing Dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

during the First

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and reco ...

(1839–1842) and Second Opium Wars (1856–1860), student activism has played a significant role in the modern Chinese history.

Fueled mostly by Chinese nationalism

Chinese nationalism () is a form of nationalism in the People's Republic of China (Mainland China) and the Republic of China on Taiwan which asserts that the Chinese people are a nation and promotes the cultural and national unity of all C ...

, Chinese student activism strongly believes that young people are responsible for China's future. This strong nationalistic belief has been able to manifest in several forms such as democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which people, the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation ("direct democracy"), or to choo ...

, anti-Americanism

Anti-Americanism (also called anti-American sentiment) is prejudice, fear, or hatred of the United States, its government, its foreign policy, or Americans in general.

Political scientist Brendon O'Connor at the United States Studies Ce ...

and Communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society ...

.

One of the most important acts of student activism in Chinese history is the 1919 May Fourth Movement

The May Fourth Movement was a Chinese anti-imperialist, cultural, and political movement which grew out of student protests in Beijing on May 4, 1919. Students gathered in front of Tiananmen (The Gate of Heavenly Peace) to protest the Chin ...

that saw over 3,000 students of Peking University

Peking University (PKU; ) is a public research university in Beijing, China. The university is funded by the Ministry of Education.

Peking University was established as the Imperial University of Peking in 1898 when it received its royal charte ...

and other schools gathered together in front of Tiananmen

The Tiananmen (also Tian'anmen (天安门), Tienanmen, T’ien-an Men; ), or the Gate of Heaven-Sent Pacification, is a monumental gate in the city center of Beijing, China, the front gate of the Imperial City of Beijing, located near the ...

and holding a demonstration. It is regarded as an essential step of the democratic revolution in China, and it had also give birth to Chinese Communism. Anti-Americanism movements led by the students during the Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on main ...

were also instrumental in discrediting the KMT government and bring the Communist victory in China. In 1989, the democracy movement led by the students at the Tiananmen Square protests

The Tiananmen Square protests, known in Chinese as the June Fourth Incident (), were student-led demonstrations held in Tiananmen Square, Beijing during 1989. In what is known as the Tiananmen Square Massacre, or in Chinese the June Fourth ...

ended in a brutal government crackdown which would later be called a massacre.

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Student activism played an important, yet understudied, role in Congo's crisis of decolonisation. Throughout the 1960s, students denounced the unfinished decolonisation of higher education and the unrealised promises of national independence. The two issues crossed in the demonstration of June 4, 1969. Student activism continues and women such as Aline Mukovi Neema, winner of 100 Women BBC award, continue to campaign for political change in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.Eastern Europe and the post-Soviet Union states

During communist rule, students in

During communist rule, students in Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, wh ...

were the force behind several of the best-known instances of protest. The chain of events leading to the 1956 Hungarian Revolution

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 (23 October – 10 November 1956; hu, 1956-os forradalom), also known as the Hungarian Uprising, was a countrywide revolution against the government of the Hungarian People's Republic (1949–1989) and the Hunga ...

was started by peaceful student demonstrations in the streets of Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population ...

, later attracting workers and other Hungarians. In Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

, one of the most known faces of the protests following the Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

-led invasion that ended the Prague Spring

The Prague Spring ( cs, Pražské jaro, sk, Pražská jar) was a period of political liberalization and mass protest in

the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. It began on 5 January 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubček was elected First Se ...

was Jan Palach

Jan Palach (; 11 August 1948 – 19 January 1969) was a Czech student of history and political economics at Charles University in Prague. His self-immolation was a political protest against the end of the Prague Spring resulting from the 1968 i ...

, a student who committed suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and ...

by setting fire to himself on January 16, 1969. The act triggered a major protest against the occupation.

Student-dominated youth movements have also played a central role in the "color revolutions

Colour revolution (sometimes coloured revolution) is a term used since around 2004 by worldwide media to describe various anti-regime protest movements and accompanying (attempted or successful) changes of government that took place in po ...

" seen in post-communist societies in recent years.

Of the color revolutions, the Velvet Revolution of 1989 in the Czechoslovak capital of Prague was one of them. Though the Velvet Revolution began as a celebration of International Students Day, the single event quickly turned into a nationwide ordeal aimed at the dissolution of communism. The demonstration had turned violent when police intervened. However, the police attacks garnered nationwide sympathy for the student protesters. Soon enough multiple other protests unraveled in an effort to breakdown the one party communist regime of Czechoslovakia. The series of protests were successful; they broke down the communist regime and implemented the use of democratic elections in 1990, only a few months after the first protest.

Another example of this was the Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin and the Balkans. It shares land borders with Hung ...

n Otpor!

Otpor ( sr-Cyrl, Отпор!, en, Resistance!, stylized as Otpor!) was a political organization in Serbia (then part of FR Yugoslavia) from 1998 until 2004.

In its initial period from 1998 to 2000, Otpor began as a civic protest group, eventua ...

("Resistance!" in Serbian

Serbian may refer to:

* someone or something related to Serbia, a country in Southeastern Europe

* someone or something related to the Serbs, a South Slavic people

* Serbian language

* Serbian names

See also

*

*

* Old Serbian (disambigua ...

), formed in October 1998 as a response to repressive university and media laws that were introduced that year. In the presidential campaign in September 2000, the organisation engineered the "Gotov je" ("He's finished") campaign that galvanized Serbian discontent with Slobodan Milošević

Slobodan Milošević (, ; 20 August 1941 – 11 March 2006) was a Yugoslav and Serbian politician who was the president of Serbia within Yugoslavia from 1989 to 1997 (originally the Socialist Republic of Serbia, a constituent republic of ...

, ultimately resulting in his defeat.

Otpor has inspired other youth movements in Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, wh ...

, such as Kmara

Kmara ( ka, კმარა; "Enough!") was a civic youth resistance movement in Georgia, active in the protests prior to and during the November 2003 Rose Revolution, which toppled down the government of Eduard Shevardnadze. Consciously modeled on ...

in Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to t ...

, which played an important role in the Rose Revolution

The Rose Revolution or Revolution of Roses ( ka, ვარდების რევოლუცია, tr) was a nonviolent change of power that occurred in Georgia in November 2003. The event was brought about by widespread protests over the ...

, and PORA

Pora! ( uk, Пора!, Russian: Пора!), meaning “''It's time!”'' in both Ukrainian and Russian, is a civic youth organization (Black Pora!) and political party in Ukraine ( Yellow Pora!) espousing nonviolent resistance and advocating in ...

in Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian invas ...

, which was key in organising the demonstrations that led to the Orange Revolution

The Orange Revolution ( uk, Помаранчева революція, translit=Pomarancheva revoliutsiia) was a series of protests and political events that took place in Ukraine from late November 2004 to January 2005, in the immediate afterm ...

. Like Otpor, these organisations have consequently practiced non-violent resistance

Nonviolent resistance (NVR), or nonviolent action, sometimes called civil resistance, is the practice of achieving goals such as social change through symbolic protests, civil disobedience, economic or political noncooperation, satyagraha, cons ...

and used ridiculing humor in opposing authoritarian leaders. Similar movements include KelKel

KelKel is a youth movement in Kyrgyzstan that gained some prominence during the Tulip Revolution of March 2005 that culminated in the ousting of President Askar Akayev. In Kyrgyz, KelKel means renaissance.

In many of the post-communist revolutions ...

in Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan,, pronounced or the Kyrgyz Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Asia. Kyrgyzstan is bordered by Kazakhstan to the north, Uzbekistan to the west, Tajikistan to the south, and the People's Republic of China to the ea ...

, Zubr Zubr may refer to:

*Żubr or Zubr, the name in several Slavic languages for the wisent or European bison (''Bison bonasus'')

* Zubr (political organization), a civic youth organization in Belarus

*''Zubr'', a novel by Daniil Granin

* TOZ-55 "Zubr" ...

in Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by ...

and MJAFT!

MJAFT! () is a non governmental organisation in Albania that is partly funded by the U.S. government.

See also

* Erion Veliaj

* Elisa Spiropali

* Politics of Albania

* Color Revolution

References

{{commons category, MJAFT!

External links

...

in Albania

Albania ( ; sq, Shqipëri or ), or , also or . officially the Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika e Shqipërisë), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is located on the Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the ...

.

Opponents of the "color revolutions" have accused the Soros Foundation

Open Society Foundations (OSF), formerly the Open Society Institute, is a grantmaking network founded and chaired by business magnate George Soros. Open Society Foundations financially supports civil society groups around the world, with a st ...

s and/or the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

government of supporting and even planning the revolutions in order to serve western interests. Supporters of the revolutions have argued that these allegations are greatly exaggerated, and that the revolutions were positive events, morally justified, whether or not Western support had an influence on the events.

France

In

In France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan ar ...

, student activists have been influential in shaping public debate. In May 1968

The following events occurred in May 1968:

May 1, 1968 (Wednesday)

* CARIFTA, the Caribbean Free Trade Association, was formally created as an agreement between Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Guyana, and Trinidad and Tobago.

*RAF Strike ...

the University of Paris

The University of Paris (french: link=no, Université de Paris), Metonymy, metonymically known as the Sorbonne (), was the leading university in Paris, France, active from 1150 to 1970, with the exception between 1793 and 1806 under the French Revo ...

at Nanterre

Nanterre (, ) is the prefecture of the Hauts-de-Seine department in the western suburbs of Paris. It is located some northwest of the centre of Paris. In 2018, the commune had a population of 96,807.

The eastern part of Nanterre, bordering ...

was closed due to problems between the students and the administration. In protest of the closure and the expulsion of Nanterre students, students of the Sorbonne

Sorbonne may refer to:

* Sorbonne (building), historic building in Paris, which housed the University of Paris and is now shared among multiple universities.

*the University of Paris (c. 1150 – 1970)

*one of its components or linked institution, ...

in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. ...

began their own demonstration. The situation escalated into a nationwide insurrection

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

.

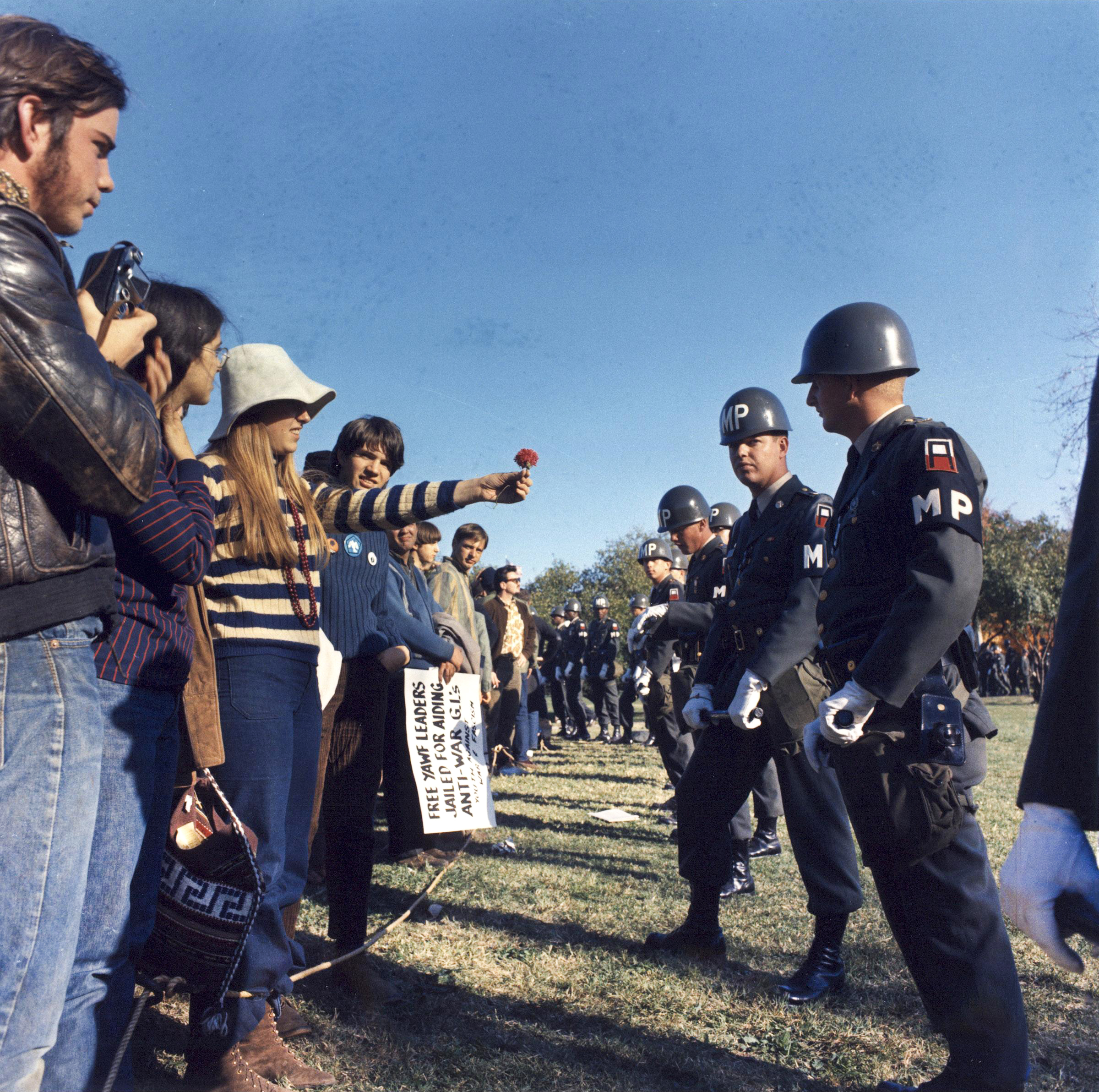

The events in Paris were followed by student protests throughout the world. The German student movement

The West German student movement or sometimes called the 1968 movement in West Germany was a social movement that consisted of mass student protests in West Germany in 1968; participants in the movement would later come to be known as 68ers. Th ...

participated in major demonstrations against proposed emergency legislation

An emergency is an urgent, unexpected, and usually dangerous situation that poses an immediate risk to health, life, property, or environment and requires immediate action. Most emergencies require urgent intervention to prevent a worseni ...

. In many countries, the student protests caused authorities to respond with violence. In Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' ( Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

, student demonstrations against Franco's

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War and thereafter ruled over Spain from 193 ...

dictatorship led to clashes with police. A student demonstration in Mexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital and largest city of Mexico, and the most populous city in North America. One of the world's alpha cities, it is located in the Valley of ...

ended in a storm of bullets on the night of October 2, 1968, an event known as the Tlatelolco massacre

On October 2, 1968 in the Tlatelolco section of Mexico City, the Mexican Armed Forces opened fire on a group of unarmed civilians in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas who were protesting the upcoming 1968 Summer Olympics. The Mexican government an ...

. Even in Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

, students took to the streets to protest changes in education policy, and on November 7 two college students died after police opened fire on a demonstration. The global reverberations from the French uprising of 1968 continued into 1969 and even into the 1970s.

Germany

In 1815 in

In 1815 in Jena

Jena () is a German city and the second largest city in Thuringia. Together with the nearby cities of Erfurt and Weimar, it forms the central metropolitan area of Thuringia with approximately 500,000 inhabitants, while the city itself has a po ...

(Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG),, is a country in Central Europe. It is the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany lies between the Baltic and North Sea to the north and the Alps to the sou ...

) the "Urburschenschaft" was founded. That was a Studentenverbindung

(; often referred to as Verbindung) is the umbrella term for many different kinds of fraternity-type associations in German-speaking countries, including Corps, , , , and Catholic fraternities. Worldwide, there are over 1,600 , about a thousa ...

that was concentrated on national and democratic ideas.

In 1817, inspired by liberal and patriotic ideas of a united Germany, student organisations gathered for the Wartburg festival at Wartburg Castle

The Wartburg () is a castle originally built in the Middle Ages. It is situated on a precipice of to the southwest of and overlooking the town of Eisenach, in the state of Thuringia, Germany. It was the home of St. Elisabeth of Hungary, the ...

, at Eisenach

Eisenach () is a town in Thuringia, Germany with 42,000 inhabitants, located west of Erfurt, southeast of Kassel and northeast of Frankfurt. It is the main urban centre of western Thuringia and bordering northeastern Hessian regions, sit ...

in Thuringia

Thuringia (; german: Thüringen ), officially the Free State of Thuringia ( ), is a state of central Germany, covering , the sixth smallest of the sixteen German states. It has a population of about 2.1 million.

Erfurt is the capital and lar ...

, on the occasion of which reactionary books were burnt.

In 1819 the student Karl Ludwig Sand

Karl Ludwig Sand (Wunsiedel, Upper Franconia (then in Prussia), 5 October 1795 – Mannheim, 20 May 1820) was a German university student and member of a liberal Burschenschaft (student association). He was executed in 1820 for the murder of the ...

murdered the writer August von Kotzebue

August Friedrich Ferdinand von Kotzebue (; – ) was a German dramatist and writer who also worked as a consul in Russia and Germany.

In 1817, one of Kotzebue's books was burned during the Wartburg festival. He was murdered in 1819 by Karl L ...

, who had scoffed at liberal student organisations.

In May 1832 the Hambacher Fest

The Hambacher Festival was a German national democratic festival celebrated from 27 May to 30 May 1832 at Hambach Castle, near Neustadt an der Weinstraße, in present-day Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. The event was disguised as a nonpolitical cou ...

was celebrated at Hambach Castle

Hambach Castle (german: Hambacher Schloss) is a castle near the urban district Hambach of Neustadt an der Weinstraße in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. It is considered a symbol of the German democracy movement because of the Hambacher Fest whic ...

near Neustadt an der Weinstraße

Neustadt an der Weinstraße (, formerly known as ; lb, Neustadt op der Wäistrooss ; pfl, Naischdadt) is a town in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. With 53,300 inhabitants , it is the largest town called ''Neustadt''.

Geography

Location

T ...

with about 30 000 participants, amongst them many students. Together with the Frankfurter Wachensturm

The Frankfurter Wachensturm (German: charge of the Frankfurt guard house) on 3 April 1833 was a failed attempt to start a revolution in Germany.

Events

About 50 students attacked the soldiers and policemen of the Frankfurt Police offices '' Hau ...

in 1833 planned to free students held in prison at Frankfurt and Georg Büchner

Karl Georg Büchner (17 October 1813 – 19 February 1837) was a German dramatist and writer of poetry and prose, considered part of the Young Germany movement. He was also a revolutionary and the brother of physician and philosopher Ludwig Büch ...

's revolutionary pamphlet

A pamphlet is an unbound book (that is, without a hard cover or binding). Pamphlets may consist of a single sheet of paper that is printed on both sides and folded in half, in thirds, or in fourths, called a ''leaflet'' or it may consist of a f ...

''Der Hessische Landbote'' that were events that led to the revolutions in the German states in 1848.

In the 1960s, the worldwide upswing in student and youth radicalism manifested itself through the German student movement

The West German student movement or sometimes called the 1968 movement in West Germany was a social movement that consisted of mass student protests in West Germany in 1968; participants in the movement would later come to be known as 68ers. Th ...

and organisations such as the German Socialist Student Union. The movement in Germany shared many concerns of similar groups elsewhere, such as the democratisation of society and opposing the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

, but also stressed more nationally specific issues such as coming to terms with the legacy of the Nazi regime

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and opposing the German Emergency Acts

The German Emergency Acts (') were passed on 30 May 1968 at the time of the '' First Grand Coalition'' between the Social Democratic Party of Germany and the Christian Democratic Union of Germany. It was the 17th constitutional amendment to the Ba ...

.

Greece

Student activism in Greece has a long and intense history. Student activism in the 1960s was one of the reasons cited to justify the imposition of the dictatorship in 1967. Following the imposition of the dictatorship, the Athens Polytechnic uprising in 1973 triggered a series of events that led to the abrupt end of the regime's attempted "liberalisation" process underSpiros Markezinis

Spyridon "Spyros" Markezinis (or Markesinis; ; 22 April 1909 – 4 January 2000) was a Greek politician, longtime member of the Hellenic Parliament, and briefly the Prime Minister of Greece during the aborted attempt at metapolitefsi (democra ...

, and, after that, to the eventual collapse of the Greek junta during Metapolitefsi

The Metapolitefsi ( el, Μεταπολίτευση, , " regime change") was a period in modern Greek history from the fall of the Ioaniddes military junta of 1973–74 to the transition period shortly after the 1974 legislative elections.

The ...

and the return of democracy in Greece. Kostas Georgakis

Kostas Georgakis ( el, Κώστας Γεωργάκης) (23 August 194819 September 1970) was a Greek student of geology, who in the early hours of 19 September 1970, set himself ablaze in Matteotti square in Genoa in a fatal protest against t ...

was a Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

student of geology

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Ea ...

, who, in the early hours of 19 September 1970, set himself ablaze in Matteotti Matteotti is an Italian surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*Giacomo Matteotti (1885–1924), Italian politician

*Gianmatteo Matteotti (1921–2000), Italian politician

*Luca Matteotti (born 1989), Italian snowboarder

See also

*Pon ...

square in Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Regions of Italy, Italian region of Liguria and the List of cities in Italy, sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of t ...

as a protest

A protest (also called a demonstration, remonstration or remonstrance) is a public expression of objection, disapproval or dissent towards an idea or action, typically a political one.

Protests can be thought of as acts of coopera ...

against the dictatorial regime of Georgios Papadopoulos

Geórgios Papadopoulos (; el, Γεώργιος Παπαδόπουλος ; 5 May 1919 – 27 June 1999) was a Greek military officer and political leader who ruled Greece as a military dictator from 1967 to 1973. He joined the Royal Hellenic ...

. His suicide greatly embarrassed the junta, and caused a sensation in Greece and abroad as it was the first tangible manifestation of the depth of resistance against the junta. The junta delayed the arrival of his remains to Corfu for four months citing security reasons and fearing demonstrations while presenting bureaucratic

The term bureaucracy () refers to a body of non-elected governing officials as well as to an administrative policy-making group. Historically, a bureaucracy was a government administration managed by departments staffed with non-elected offi ...

obstacles through the Greek consulate and the junta government.

Hong Kong

Hong Kong Student activist groupScholarism

Scholarism was a Hong Kong pro-democracyWilfred Chan and Yuli Yang, CNNbr>Echoing Tiananmen, 17-year-old Hong Kong student prepares for democracy battle 28 September 2014 student activist group active in the fields of Hong Kong's education ...

began an occupation of the Hong Kong government headquarters on 30 August 2012. The goal of the protest was, expressly, to force the government to retract its plans to introduce Moral and National Education as a compulsory subject. On 1 September, an open concert was held as part of the protest, with an attendance of 40,000. At last, the government de facto struck down the Moral and National Education.

Student organizations made important roles during the Umbrella Movement

The Umbrella Movement () was a political movement that emerged during the Hong Kong democracy protests of 2014. Its name arose from the use of umbrellas as a tool for passive resistance to the Hong Kong Police's use of pepper spray to dispe ...

. Standing Committee of the National People's Congress

The Standing Committee of the National People's Congress of the People's Republic of China (NPCSC) is the permanent body of the National People's Congress (NPC) of the People's Republic of China (PRC), which is the highest organ of state po ...

(NPCSC) made decisions on the Hong Kong political reform on 31 August 2014, which the Nominating Committee

A committee or commission is a body of one or more persons subordinate to a deliberative assembly. A committee is not itself considered to be a form of assembly. Usually, the assembly sends matters into a committee as a way to explore them mor ...

would tightly control the nomination of the Chief Executive candidate, candidates outside the Pro-Beijing camp

The pro-Beijing camp, pro-establishment camp, pro-government camp or pro-China camp refers to a political alignment in Hong Kong which generally supports the policies of the Beijing central government and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) t ...

would not have opportunities to be nominated. The Hong Kong Federation of Students

The Hong Kong Federation of Students (HKFS, or 學聯) is a student organisation founded in May 1958 by the student unions of four higher education institutions in Hong Kong. The inaugural committee had seven members representing the four sc ...

and Scholarism

Scholarism was a Hong Kong pro-democracyWilfred Chan and Yuli Yang, CNNbr>Echoing Tiananmen, 17-year-old Hong Kong student prepares for democracy battle 28 September 2014 student activist group active in the fields of Hong Kong's education ...

led a strike against the NPCSC's decision beginning on 22 September 2014, and started protesting outside the government headquarters on 26 September 2014. On 28 September, the Occupy Central with Love and Peace

Occupy Central with Love and Peace (OCLP) was a single-purpose Hong Kong civil disobedience campaign initiated by Reverend Chu Yiu-ming, Benny Tai and Chan Kin-man on 27 March 2013. The campaign was launched on 24 September 2014, partially l ...

movement announced that the beginning of their civil disobedience campaign. Students and other members of the public demonstrated outside government headquarters, and some began to occupy several major city intersections.

India

The

The Assam Movement

The Assam Movement (also Anti-Foreigners Agitation) (1979–1985) was a popular uprising in Assam, India, that demanded the Government of India to detect, disenfranchise and deport illegal aliens. Led by All Assam Students Union (AASU) and A ...

(or Assam Agitation) (1979–1985) was a popular movement against illegal immigrants

Illegal immigration is the migration of people into a country in violation of the immigration laws of that country or the continued residence without the legal right to live in that country. Illegal immigration tends to be financially upwar ...

in Assam

Assam (; ) is a state in northeastern India, south of the eastern Himalayas along the Brahmaputra and Barak River valleys. Assam covers an area of . The state is bordered by Bhutan and Arunachal Pradesh to the north; Nagaland and Manipur ...

. The movement, led by All Assam Students Union

All Assam Students' Union or AASU is a Assamese nationalist students' organisation in Assam, India. It is best known for leading the six-year Assam Movement against Bengalis of both Indian and Bangladeshi origin living in Assam. The leadership, ...

(AASU) and the 'All Assam Gana Sangram Parishad' (AAGSP), developed a program of protests and demonstration to compel the Indian government

The Government of India (ISO: ; often abbreviated as GoI), known as the Union Government or Central Government but often simply as the Centre, is the national government of the Republic of India, a federal democracy located in South Asia, c ...

to identify and expel illegal, (mostly Bangladeshis

Bangladeshis ( bn, বাংলাদেশী ) are the citizens of Bangladesh, a South Asian country centered on the transnational historical region of Bengal along the eponymous bay.

Bangladeshi citizenship was formed in 1971, when th ...

i), immigrants and protect and provide constitutional, legislative and administrative safeguards to the indigenous Assamese people

The Assamese people are a socio- ethnic linguistic identity that has been described at various times as nationalistic or micro-nationalistic. This group is often associated with the Assamese language, the easternmost Indo-Aryan language, ...

.

On 16 January 2017 a large group of students (more than 2 million) protested in state of

On 16 January 2017 a large group of students (more than 2 million) protested in state of Tamil Nadu

Tamil Nadu (; , TN) is a state in southern India. It is the tenth largest Indian state by area and the sixth largest by population. Its capital and largest city is Chennai. Tamil Nadu is the home of the Tamil people, whose Tamil languag ...

and Puducherry Puducherry or Pondicherry may refer to:

* Puducherry (union territory), a union territory of India

** Pondicherry, capital of the union territory of Puducherry

** Puducherry district, a district of the union territory of Puducherry

** Puducherry ta ...

against the ban on Jallikattu

(or ), also known as and , is a traditional event in which a bull ('' Bos indicus''), such as the Pulikulam or Kangayam breeds, is released into a crowd of people, and multiple human participants attempt to grab the large hump on the bull's b ...

. The ban was made by the Supreme Court of India in 2014 when PETA filed a petition against Jallikattu as a cruelty to animals. On 20 January a temporary ordinance was passed, lifting the ban on Jallikattu.

The Jadavpur University of Kolkata have played an important role to contribute to the student activism of India. The 2014 Jadavpur University protests, Hokkolorob Movement (2014) stirred the nation as well as abroad which took place over here. It took place after the alleged police attack over unarmed students inside the campus demanding the fair justice of a student who was molested inside the campus. The Movement finally led to the expulsion of the contemporary Vice-chancellor, Vice Chancellor of the university, Mr. Abhijit Chakraborty, who allegedly ordered the police to do open lathicharge over the students. Some anti-social goons were also involved in the harassment of the students.

Indonesia

Indonesia is often believed to have hosted "some of the most important acts of student resistance in the world's history". University student groups have repeatedly been the first groups to stage street demonstrations calling for governmental change at key points in the nation's history, and other organizations from across the political spectrum have sought to align themselves with student groups. In 1928, the Youth Pledge (Sumpah Pemuda) helped to give voice to anti-colonial sentiments.

During the political turmoil of the 1960s, right-wing student groups staged demonstrations calling for then-President Sukarno to eliminate alleged Communists from his government, and later demanding that he resign. Sukarno did step down in 1967, and was replaced by Army general Suharto.

Student groups also played a key role in Suharto's 1998 fall by initiating large demonstrations that gave voice to widespread popular discontent with the president in the aftermath of the May 1998 riots of Indonesia, May 1998 riots. High school and university students in Jakarta, Yogyakarta (city), Yogyakarta, Medan, Indonesia, Medan, and elsewhere were some of the first groups willing to speak out publicly against the military government. Student groups were a key part of the political scene during this period. Upon taking office after Suharto stepped down, B. J. Habibie made numerous mostly unsuccessful overtures to placate the student groups that had brought down his predecessor. When that failed, he sent a combined force of police and Preman (Indonesian gangster), gangsters to evict protesters occupying a government building by force. The ensuing carnage left two students dead and 181 injured.

Indonesia is often believed to have hosted "some of the most important acts of student resistance in the world's history". University student groups have repeatedly been the first groups to stage street demonstrations calling for governmental change at key points in the nation's history, and other organizations from across the political spectrum have sought to align themselves with student groups. In 1928, the Youth Pledge (Sumpah Pemuda) helped to give voice to anti-colonial sentiments.

During the political turmoil of the 1960s, right-wing student groups staged demonstrations calling for then-President Sukarno to eliminate alleged Communists from his government, and later demanding that he resign. Sukarno did step down in 1967, and was replaced by Army general Suharto.

Student groups also played a key role in Suharto's 1998 fall by initiating large demonstrations that gave voice to widespread popular discontent with the president in the aftermath of the May 1998 riots of Indonesia, May 1998 riots. High school and university students in Jakarta, Yogyakarta (city), Yogyakarta, Medan, Indonesia, Medan, and elsewhere were some of the first groups willing to speak out publicly against the military government. Student groups were a key part of the political scene during this period. Upon taking office after Suharto stepped down, B. J. Habibie made numerous mostly unsuccessful overtures to placate the student groups that had brought down his predecessor. When that failed, he sent a combined force of police and Preman (Indonesian gangster), gangsters to evict protesters occupying a government building by force. The ensuing carnage left two students dead and 181 injured.

Iran

In Iran, students have been at the forefront of protests both against the pre-1979 secular monarchy and, in recent years, against the theocratic islamic republic. Both religious and more moderate students played a major part in Ruhollah Khomeini's opposition network against the Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. In January 1978 the army dispersed demonstrating students and religious leaders, killing several students and sparking a series of widespread protests that ultimately led to the Iranian Revolution the following year. On November 4, 1979, militant Iranian students calling themselves the Muslim Students Following the Line of the Imam seized the United States of America, US embassy in Tehran holding 52 embassy employees hostage for a 444 days (see Iran hostage crisis).

Recent years have seen several incidents when liberal students have clashed with the Iranian government, most notably the Iran student riots, July 1999, Iranian student riots of July 1999. Several people were killed in a week of violent confrontations that started with a police raid on a university dormitory, a response to demonstrations by a group of students of Tehran University against the closure of a reformist newspaper. Akbar Mohammadi (student), Akbar Mohammadi was given a capital punishment, death sentence, later reduced to 15 years in prison, for his role in the protests. In 2006, he died at Evin prison after a hunger strike protesting the refusal to allow him to seek medical treatment for injuries suffered as a result of torture.

At the end of 2002, students held mass demonstrations protesting the death sentence of reformist lecturer Hashem Aghajari for alleged blasphemy. In June 2003, several thousand students took to the streets of Tehran in anti-government protests sparked by government plans to privatise some universities.

In the May 2005 Iranian presidential election, 2005, Iranian presidential election, Iran's largest student organization, The Office to Consolidate Unity, advocated a voting boycott. After the election of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, student protests against the government has continued. In May 2006, up to 40 police officers were injured in clashes with demonstrating students in Tehran. At the same time, the Iranian government has called for student action in line with its own political agenda. In 2006, President Ahmadinejad urged students to organize campaigns to demand that liberal and secular university teachers be removed.