Stonehenge Stukley Oxford 03543 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

, ''University of Birmingham Press Release, 26 November 2011 The new discovery was made as part of the Stonehenge Hidden Landscape Project which began in the summer of 2010. The project uses non-invasive geophysical imaging technique to reveal and visually recreate the landscape. According to team leader Vince Gaffney, this discovery may provide a direct link between the rituals and astronomical events to activities within the Cursus at Stonehenge. In December 2011, geologists from University of Leicester and the National Museum of Wales announced the discovery of the source of some of the

google books

* Godsell, Andrew "Stonehenge: Older Than the Centuries" in "Legends of British History" (2008) * Hall, R, Leather, K., & Dobson, G., ''Stonehenge Aotearoa'' (Awa Press, 2005) * Hawley, Lt-Col W, ''The Excavations at Stonehenge.'' (The Antiquaries Journal 1, Oxford University Press, 19–41). 1921. * Hawley, Lt-Col W., ''Second Report on the Excavations at Stonehenge.'' (The Antiquaries Journal 2, Oxford University Press, 1922) * Hawley, Lt-Col W., ''Third Report on the Excavations at Stonehenge.'' (The Antiquaries Journal 3, Oxford University Press, 1923) * Hawley, Lt-Col W, ''Fourth Report on the Excavations at Stonehenge.'' (The Antiquaries Journal 4, Oxford University Press, 1923) * Hawley, Lt-Col W., ''Report on the Excavations at Stonehenge during the season of 1923.'' (The Antiquaries Journal 5, Oxford University Press, 1925) * Hawley, Lt-Col W., ''Report on the Excavations at Stonehenge during the season of 1924.'' (The Antiquaries Journal 6, Oxford University Press, 1926) * Hawley, Lt-Col W., ''Report on the Excavations at Stonehenge during 1925 and 1926.'' (The Antiquaries Journal 8, Oxford University Press, 1928) * Hutton, R., ''From Universal Bond to Public Free For All'' (British Archaeology 83, 2005) * Hutton, Ronald, ''Blood and Mistletoe: The History of the Druids in Britain'' (Yale University Press, London, 2009 * John, Brian, "The Bluestone Enigma: Stonehenge, Preseli and the Ice Age" (Greencroft Books, 2008) * Johnson, Anthony, ''Solving Stonehenge: The New Key to an Ancient Enigma'' (Thames & Hudson, 2008) * Legg, Rodney, "Stonehenge Antiquaries" (Dorset Publishing Company, 1986) * Mooney, J., ''Encyclopedia of the Bizarre'' (Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, 2002) * Newall, R. S., ''Stonehenge, Wiltshire – Ancient monuments and historic buildings'' (Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1959) * North, J., ''Stonehenge: Ritual Origins and Astronomy'' (HarperCollins, 1997) * Pitts, M., ''Hengeworld'' (Arrow, London, 2001) * Pitts, M. W., "On the Road to Stonehenge: Report on Investigations beside the A344 in 1968, 1979 and 1980" (''Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society'' 48, 1982) * Richards, J. C., ''English Heritage Book of Stonehenge'' (B T Batsford Ltd, 1991) * Julian Richards ''Stonehenge: A History in Photographs'' (English Heritage, London, 2004) * Stone, J. F. S., ''Wessex Before the Celts'' (Frederick A Praeger Publishers, 1958) * Worthington, A., ''Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion'' (Alternative Albion, 2004) * English Heritage: ''Stonehenge: Historical Background''

Stonehenge

English Heritage official site: access and visiting information; research; future plans

Skyscape- live webfeed

360° panoramic

English Heritage: interactive view from the centre

Stonehenge Landscape

Stonehenge Today and Yesterday

By Frank Stevens, at

Stonehenge, a Temple Restor'd to the British Druids

By William Stukeley

Stonehenge, and Other British Monuments Astronomically Considered

By Norman Lockyer

British Archaeology essay about the bluestones as glacial deposits.

Stonehenge Twentieth Century Excavations Databases

An

Stonehenge is a

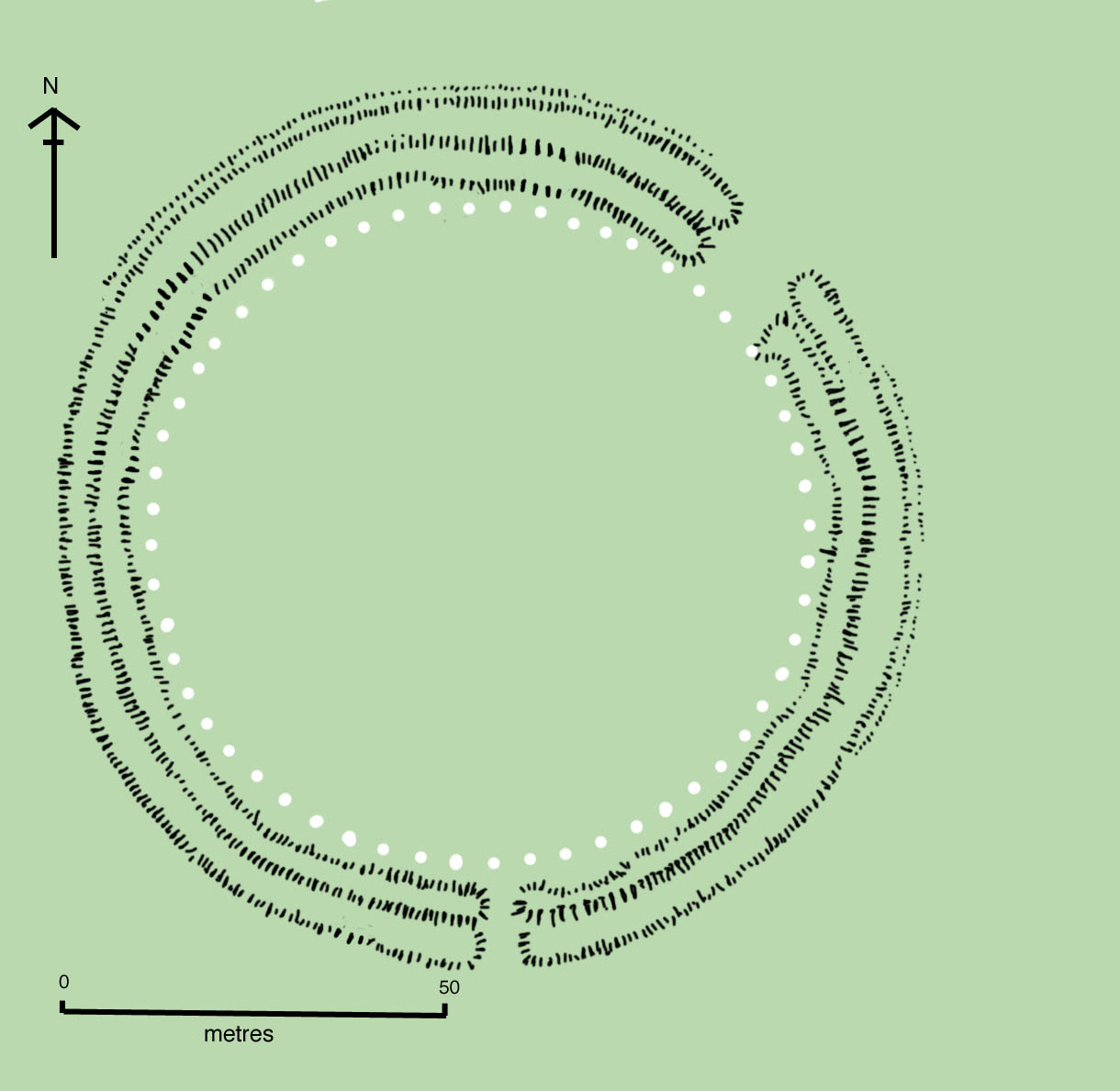

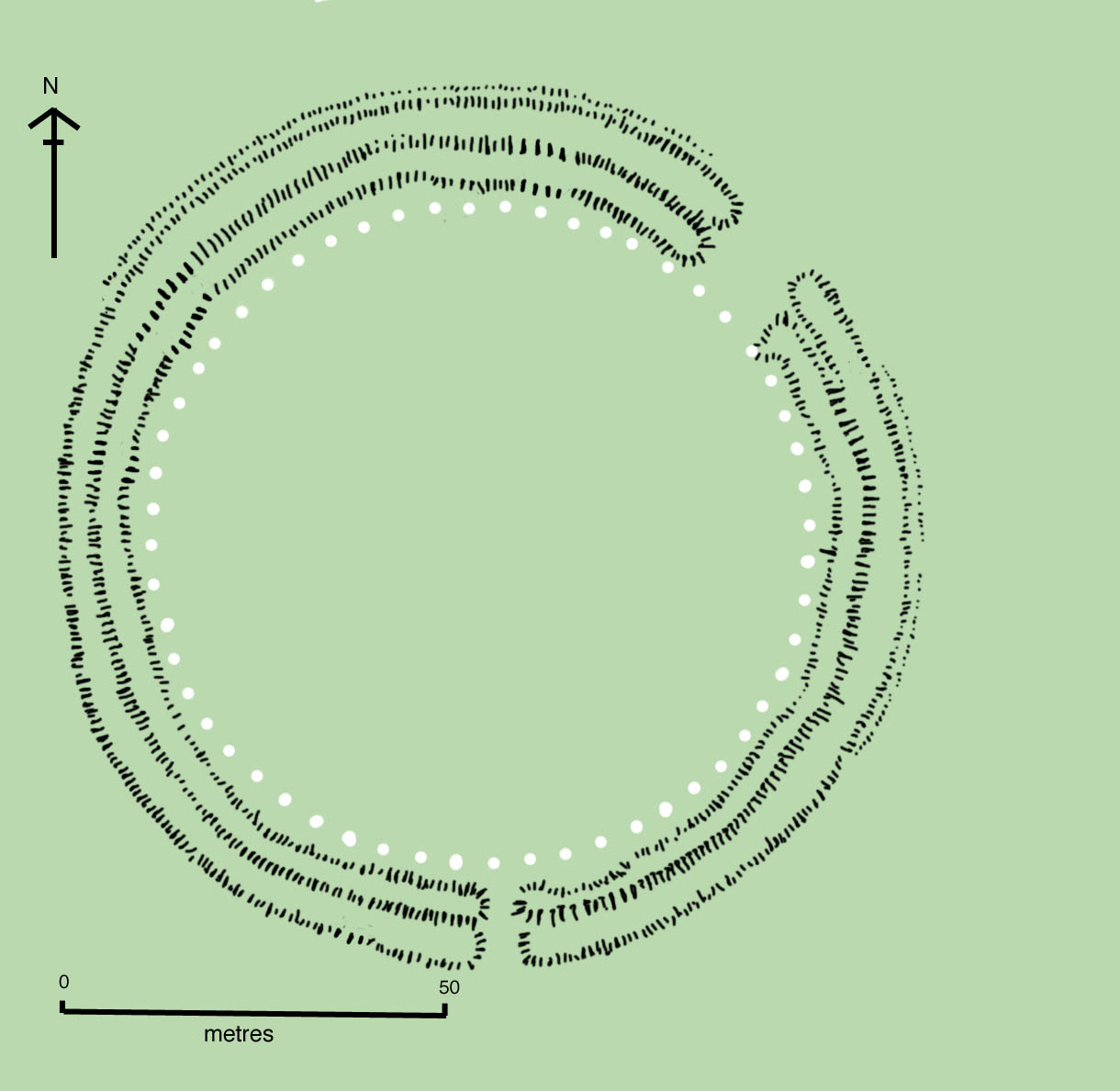

The first monument consisted of a circular bank and ditch

The first monument consisted of a circular bank and ditch

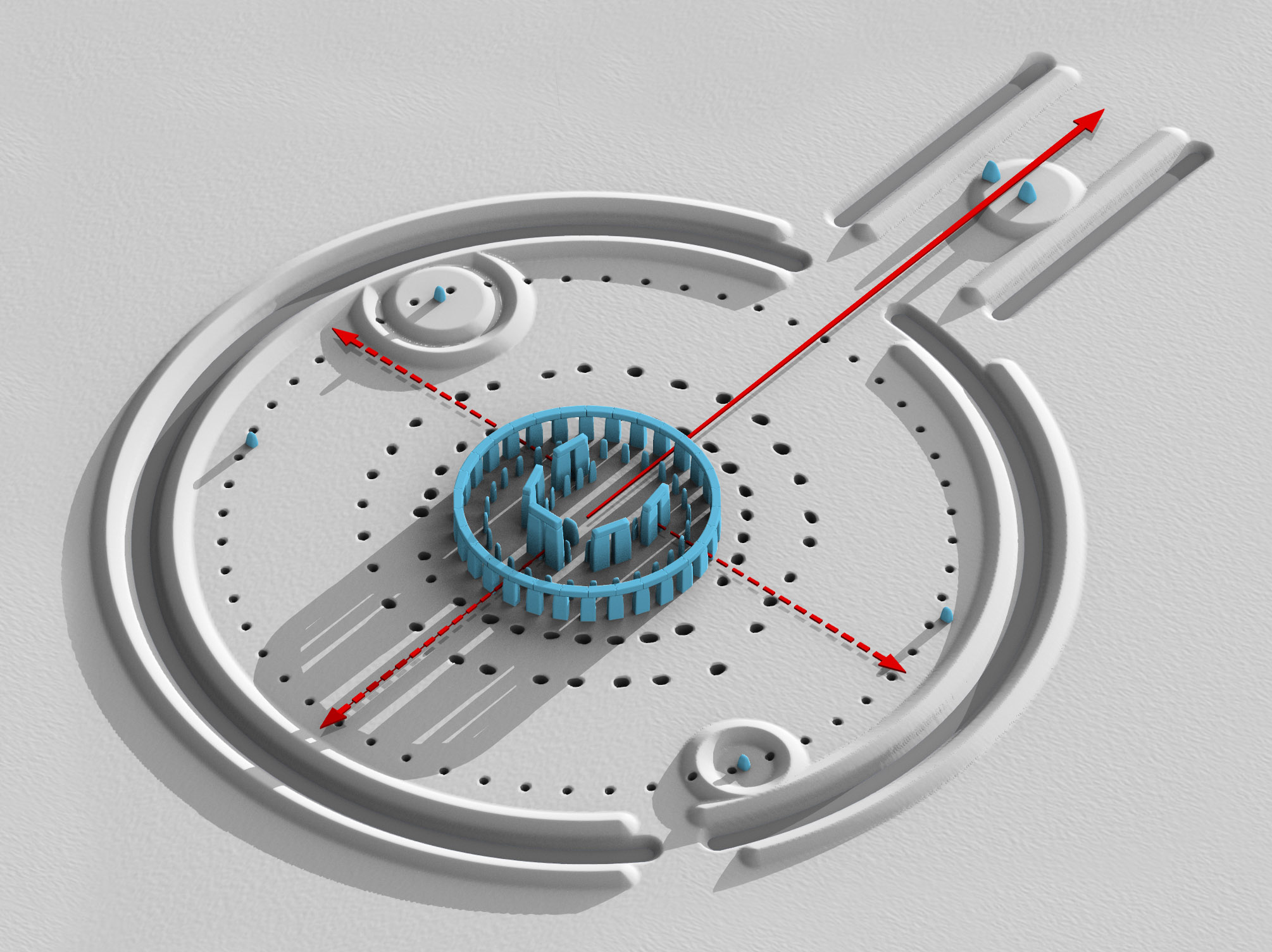

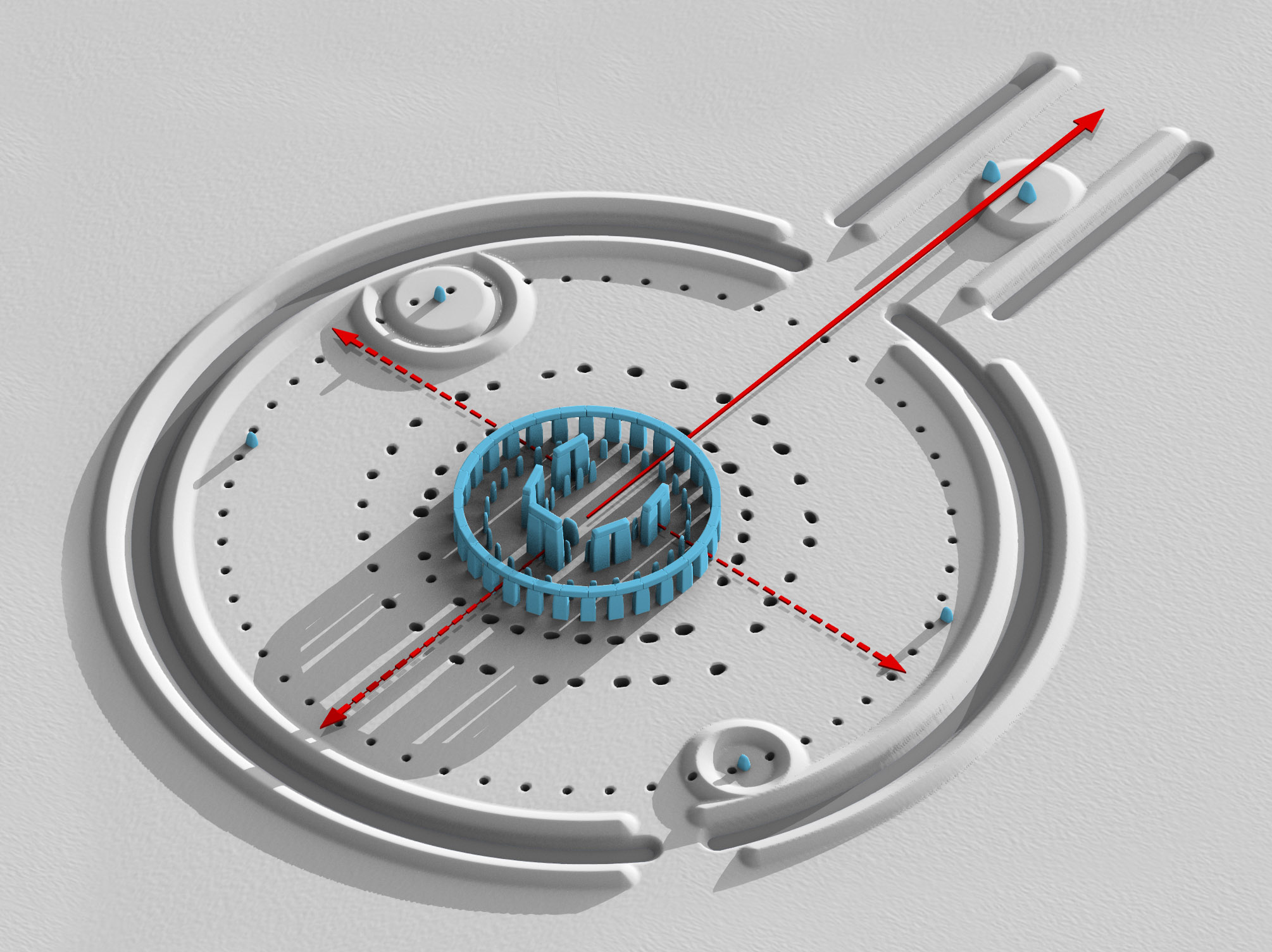

Archaeological excavation has indicated that around 2600 BC, the builders abandoned timber in favour of stone and dug two concentric arrays of holes (the Q and R Holes) in the centre of the site. These stone sockets are only partly known (hence on present evidence are sometimes described as forming 'crescents'); however, they could be the remains of a double ring. Again, there is little firm dating evidence for this phase. The holes held up to 80 standing stones (shown blue on the plan), only 43 of which can be traced today. It is generally accepted that the

Archaeological excavation has indicated that around 2600 BC, the builders abandoned timber in favour of stone and dug two concentric arrays of holes (the Q and R Holes) in the centre of the site. These stone sockets are only partly known (hence on present evidence are sometimes described as forming 'crescents'); however, they could be the remains of a double ring. Again, there is little firm dating evidence for this phase. The holes held up to 80 standing stones (shown blue on the plan), only 43 of which can be traced today. It is generally accepted that the

During the next major phase of activity, 30 enormous

During the next major phase of activity, 30 enormous

Researchers studying DNA extracted from Neolithic human remains across Britain determined that the ancestors of the people who built Stonehenge were

Researchers studying DNA extracted from Neolithic human remains across Britain determined that the ancestors of the people who built Stonehenge were

Stonehenge: DNA reveals origin of builders.

BBC News website, 16 April 2019 Neolithic individuals in the British Isles were close to Iberian and Central European Early and Middle Neolithic populations, modelled as having about 75% ancestry from Aegean farmers with the rest coming from Western Hunter-Gatherers in continental Europe. They subsequently replaced most of the hunter-gatherer population in the British Isles without mixing much with them. At that time, Britain was inhabited by groups of hunter-gatherers who were the first inhabitants of the island after the last Ice Age ended about 11,700 years ago. Despite their mostly Aegean ancestry, the paternal (Y-DNA) lineages of Neolithic farmers in Britain were almost exclusively of Western Hunter-Gatherer origin. This was also the case among other megalithic-building populations in northwest Europe, meaning that these populations were descended from a mixture of hunter-gatherer males and farmer females. This mixture appears to have happened primarily on the continent before the Neolithic farmers migrated to Britain. The dominance of Western Hunter-Gatherer male lineages in Britain and northwest Europe is also reflected in a general 'resurgence' of hunter-gatherer ancestry, predominantly from males, across western and central Europe in the Middle Neolithic. The Bell Beaker people arrived later, around 2,500 BC, migrating from mainland Europe. The earliest British beakers, most likely speakers of

The

The

The twelfth-century ''

The twelfth-century ''

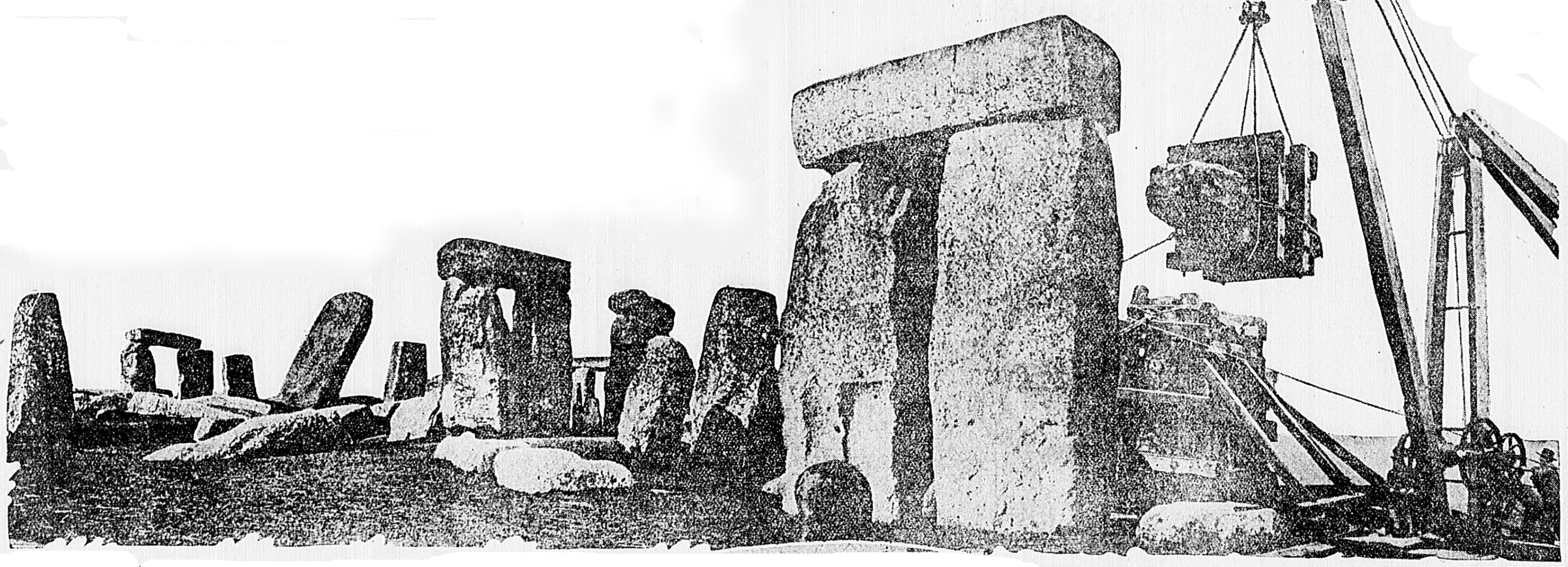

Stonehenge has changed ownership several times since

Stonehenge has changed ownership several times since  In 1915,

In 1915,  In the late 1920s a nationwide appeal was launched to save Stonehenge from the encroachment of the modern buildings that had begun to rise around it. By 1928 the land around the monument had been purchased with the appeal donations and given to the National Trust to preserve. The buildings were removed (although the roads were not), and the land returned to agriculture. More recently the land has been part of a grassland reversion scheme, returning the surrounding fields to native

In the late 1920s a nationwide appeal was launched to save Stonehenge from the encroachment of the modern buildings that had begun to rise around it. By 1928 the land around the monument had been purchased with the appeal donations and given to the National Trust to preserve. The buildings were removed (although the roads were not), and the land returned to agriculture. More recently the land has been part of a grassland reversion scheme, returning the surrounding fields to native

During the twentieth century, Stonehenge began to revive as a place of religious significance, this time by adherents of

During the twentieth century, Stonehenge began to revive as a place of religious significance, this time by adherents of  The earlier rituals were complemented by the

The earlier rituals were complemented by the

When Stonehenge was first opened to the public it was possible to walk among and even climb on the stones, but the stones were roped off in 1977 as a result of serious erosion. Visitors are no longer permitted to touch the stones but are able to walk around the monument from a short distance away. English Heritage does, however, permit access during the summer and winter solstice, and the spring and autumn equinox. Additionally, visitors can make special bookings to access the stones throughout the year. Local residents are still entitled to free admission to Stonehenge because of an agreement concerning the moving of a right of way.

The access situation and the proximity of the two roads have drawn widespread criticism, highlighted by a 2006

When Stonehenge was first opened to the public it was possible to walk among and even climb on the stones, but the stones were roped off in 1977 as a result of serious erosion. Visitors are no longer permitted to touch the stones but are able to walk around the monument from a short distance away. English Heritage does, however, permit access during the summer and winter solstice, and the spring and autumn equinox. Additionally, visitors can make special bookings to access the stones throughout the year. Local residents are still entitled to free admission to Stonehenge because of an agreement concerning the moving of a right of way.

The access situation and the proximity of the two roads have drawn widespread criticism, highlighted by a 2006  On 13 May 2009, the government gave approval for a £25 million scheme to create a smaller visitors' centre and close the A344, although this was dependent on funding and local authority planning consent. On 20 January 2010 Wiltshire Council granted planning permission for a centre to the west and English Heritage confirmed that funds to build it would be available, supported by a £10m grant from the

On 13 May 2009, the government gave approval for a £25 million scheme to create a smaller visitors' centre and close the A344, although this was dependent on funding and local authority planning consent. On 20 January 2010 Wiltshire Council granted planning permission for a centre to the west and English Heritage confirmed that funds to build it would be available, supported by a £10m grant from the

''.

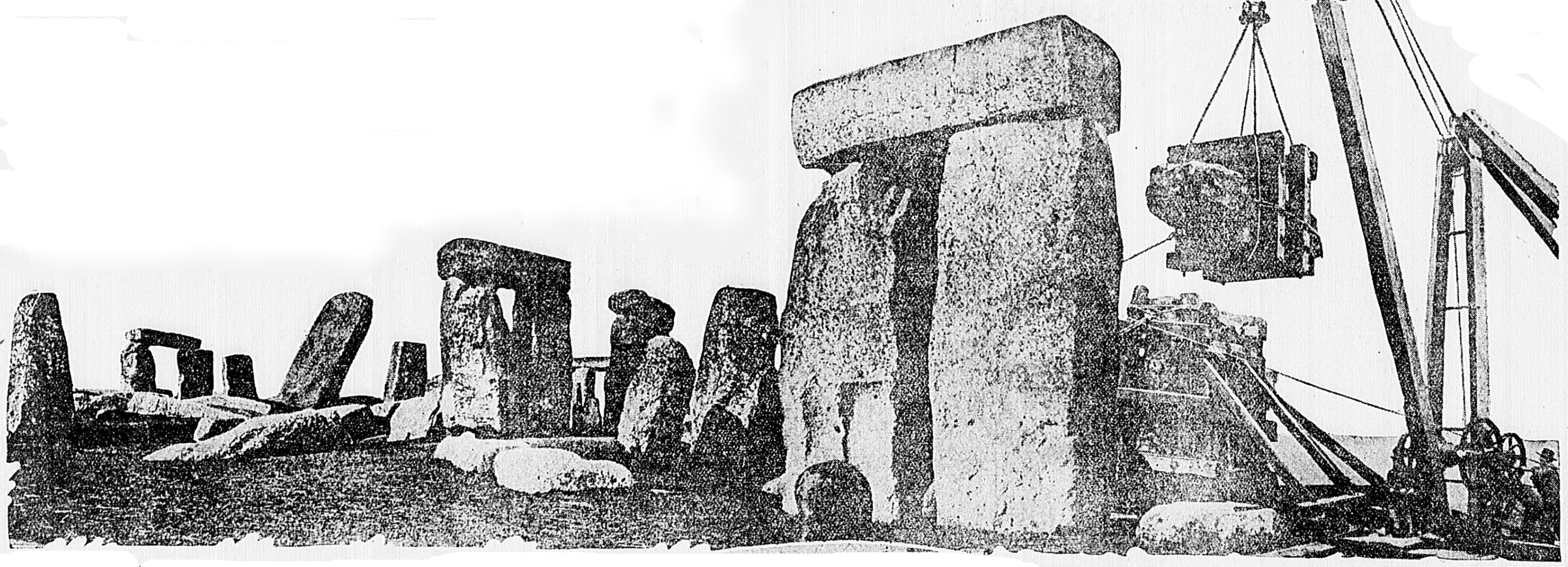

Stone 22 fell during a fierce storm on 31 December 1900.

prehistoric

Prehistory, also known as pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the use of the first stone tools by hominins 3.3 million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use of ...

monument

A monument is a type of structure that was explicitly created to commemorate a person or event, or which has become relevant to a social group as a part of their remembrance of historic times or cultural heritage, due to its artistic, his ...

on Salisbury Plain

Salisbury Plain is a chalk plateau in the south western part of central southern England covering . It is part of a system of chalk downlands throughout eastern and southern England formed by the rocks of the Chalk Group and largely lies wi ...

in Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

, England, west of Amesbury

Amesbury () is a town and civil parish in Wiltshire, England. It is known for the prehistoric monument of Stonehenge which is within the parish. The town is claimed to be the oldest occupied settlement in Great Britain, having been first settle ...

. It consists of an outer ring of vertical sarsen

Sarsen stones are silicified sandstone blocks found in quantity in Southern England on Salisbury Plain and the Marlborough Downs in Wiltshire; in Kent; and in smaller quantities in Berkshire, Essex, Oxfordshire, Dorset, and Hampshire.

Geology ...

standing stones

A menhir (from Brittonic languages: ''maen'' or ''men'', "stone" and ''hir'' or ''hîr'', "long"), standing stone, orthostat, or lith is a large human-made upright stone, typically dating from the European middle Bronze Age. They can be foun ...

, each around high, wide, and weighing around 25 tons, topped by connecting horizontal lintel

A lintel or lintol is a type of beam (a horizontal structural element) that spans openings such as portals, doors, windows and fireplaces. It can be a decorative architectural element, or a combined ornamented structural item. In the case of w ...

stones. Inside is a ring of smaller bluestone

Bluestone is a cultural or commercial name for a number of dimension or building stone varieties, including:

* basalt in Victoria, Australia, and in New Zealand

* dolerites in Tasmania, Australia; and in Britain (including Stonehenge)

* felds ...

s. Inside these are free-standing trilithon

A trilithon or trilith is a structure consisting of two large vertical stones (posts) supporting a third stone set horizontally across the top (lintel). It is commonly used in the context of megalithic monuments. The most famous trilithons ar ...

s, two bulkier vertical sarsens joined by one lintel. The whole monument, now ruinous, is aligned towards the sunrise on the summer solstice

The summer solstice, also called the estival solstice or midsummer, occurs when one of Earth's poles has its maximum tilt toward the Sun. It happens twice yearly, once in each hemisphere ( Northern and Southern). For that hemisphere, the summer ...

. The stones are set within earthworks

Earthworks may refer to:

Construction

*Earthworks (archaeology), human-made constructions that modify the land contour

* Earthworks (engineering), civil engineering works created by moving or processing quantities of soil

*Earthworks (military), m ...

in the middle of the densest complex of Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several parts ...

and Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

monuments in England, including several hundred ''tumuli

A tumulus (plural tumuli) is a mound of earth and stones raised over a grave or graves. Tumuli are also known as barrows, burial mounds or ''kurgans'', and may be found throughout much of the world. A cairn, which is a mound of stones buil ...

'' (burial mounds).

Archaeologists believe that Stonehenge was constructed from around 3000 BC to 2000 BC. The surrounding circular earth bank and ditch, which constitute the earliest phase of the monument, have been dated to about 3100 BC. Radiocarbon dating

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of radiocarbon, a radioactive isotope of carbon.

The method was dev ...

suggests that the first bluestone

Bluestone is a cultural or commercial name for a number of dimension or building stone varieties, including:

* basalt in Victoria, Australia, and in New Zealand

* dolerites in Tasmania, Australia; and in Britain (including Stonehenge)

* felds ...

s were raised between 2400 and 2200 BC, although they may have been at the site as early as 3000 BC.

One of the most famous landmarks in the United Kingdom, Stonehenge is regarded as a British cultural icon. It has been a legally protected scheduled monument

In the United Kingdom, a scheduled monument is a nationally important archaeological site or historic building, given protection against unauthorised change.

The various pieces of legislation that legally protect heritage assets from damage and d ...

since 1882, when legislation to protect historic monuments was first successfully introduced in Britain. The site and its surroundings were added to UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

's list of World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for h ...

s in 1986. Stonehenge is owned by the Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has different ...

and managed by English Heritage

English Heritage (officially the English Heritage Trust) is a charity that manages over 400 historic monuments, buildings and places. These include prehistoric sites, medieval castles, Roman forts and country houses.

The charity states that i ...

; the surrounding land is owned by the National Trust

The National Trust, formally the National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty, is a charity and membership organisation for heritage conservation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. In Scotland, there is a separate and ...

.

Stonehenge could have been a burial ground from its earliest beginnings. Deposits containing human bone date from as early as 3000 BC, when the ditch and bank were first dug, and continued for at least another 500 years.

Etymology

The ''Oxford English Dictionary

The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED'') is the first and foundational historical dictionary of the English language, published by Oxford University Press (OUP). It traces the historical development of the English language, providing a com ...

'' cites Ælfric Ælfric (Old English ', Middle English ''Elfric'') is an Anglo-Saxon given name.

Churchmen

*Ælfric of Eynsham (c. 955–c. 1010), late 10th century Anglo-Saxon abbot and writer

*Ælfric of Abingdon (died 1005), late 10th century Anglo-Saxon Archbi ...

's tenth-century glossary, in which ''henge-cliff'' is given the meaning "precipice", or stone; thus, the ''stanenges'' or ''Stanheng'' "not far from Salisbury

Salisbury ( ) is a cathedral city in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers Avon, Nadder and Bourne. The city is approximately from Southampton and from Bath.

Salisbury is in the southeast of Wil ...

" recorded by eleventh-century writers are "stones supported in the air". In 1740, William Stukeley

William Stukeley (7 November 1687 – 3 March 1765) was an English antiquarian, physician and Anglican clergyman. A significant influence on the later development of archaeology, he pioneered the scholarly investigation of the prehistoric ...

notes: "Pendulous rocks are now called henges in Yorkshire ... I doubt not, Stonehenge in Saxon signifies the hanging stones." Christopher Chippindale

Christopher Ralph Chippindale, FSA (born 13 October 1951) is a British archaeologist. He worked at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology from 1988 to his retirement in 2013, and was additionally Reader in Archaeology at the University of C ...

's ''Stonehenge Complete'' gives the derivation of the name ''Stonehenge'' as coming from the Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, Anglo ...

words ''stān'' meaning "stone", and either ''hencg'' meaning "hinge

A hinge is a mechanical bearing that connects two solid objects, typically allowing only a limited angle of rotation between them. Two objects connected by an ideal hinge rotate relative to each other about a fixed axis of rotation: all other ...

" (because the stone lintel

A lintel or lintol is a type of beam (a horizontal structural element) that spans openings such as portals, doors, windows and fireplaces. It can be a decorative architectural element, or a combined ornamented structural item. In the case of w ...

s hinge on the upright stones) or ''hen(c)en'' meaning " to hang" or "gallows

A gallows (or scaffold) is a frame or elevated beam, typically wooden, from which objects can be suspended (i.e., hung) or "weighed". Gallows were thus widely used to suspend public weighing scales for large and heavy objects such as sacks ...

" or "instrument of torture" (though elsewhere in his book, Chippindale cites the "suspended stones" etymology).

The "henge" portion has given its name to a class of monuments known as henge

There are three related types of Neolithic earthwork that are all sometimes loosely called henges. The essential characteristic of all three is that they feature a ring-shaped bank and ditch, with the ditch inside the bank. Because the internal ...

s. Archaeologists define henges as earthworks consisting of a circular banked enclosure with an internal ditch. As often happens in archaeological terminology, this is a holdover from antiquarian

An antiquarian or antiquary () is an fan (person), aficionado or student of antiquities or things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient artifact (archaeology), artifac ...

use.

Despite being contemporary with true Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several parts ...

henges and stone circle

A stone circle is a ring of standing stones. Most are found in Northwestern Europe – especially in Britain, Ireland, and Brittany – and typically date from the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age, with most being built from 3000 BC. The be ...

s, Stonehenge is in many ways atypical – for example, at more than tall, its extant trilithons' lintels, held in place with mortise and tenon

A mortise and tenon (occasionally mortice and tenon) joint connects two pieces of wood or other material. Woodworkers around the world have used it for thousands of years to join pieces of wood, mainly when the adjoining pieces connect at right ...

joints, make it unique.

Early history

Mike Parker Pearson

Michael Parker Pearson, (born 26 June 1957) is an English archaeologist specialising in the study of the Neolithic British Isles, Madagascar and the archaeology of death and burial. A professor at the UCL Institute of Archaeology, he previous ...

, leader of the Stonehenge Riverside Project

The Stonehenge Riverside Project was a major Arts and Humanities Research Council-funded archaeological research study of the development of the Stonehenge landscape in Neolithic and Bronze Age Britain. In particular, the project examined the rela ...

based around Durrington Walls

Durrington Walls is the site of a large Neolithic settlement and later henge enclosure located in the Stonehenge World Heritage Site in England. It lies north-east of Stonehenge in the parish of Durrington, just north of Amesbury in Wiltshir ...

, noted that Stonehenge appears to have been associated with burial from the earliest period of its existence:

Stonehenge evolved in several construction phases spanning at least 1500 years. There is evidence of large-scale construction on and around the monument that perhaps extends the landscape's time frame to 6500 years. Dating and understanding the various phases of activity are complicated by disturbance of the natural chalk

Chalk is a soft, white, porous, sedimentary carbonate rock. It is a form of limestone composed of the mineral calcite and originally formed deep under the sea by the compression of microscopic plankton that had settled to the sea floor. Chalk ...

by periglacial

Periglaciation (adjective: "periglacial", also referring to places at the edges of glacial areas) describes geomorphic processes that result from seasonal thawing of snow in areas of permafrost, the runoff from which refreezes in ice wedges and ot ...

effects and animal burrowing, poor quality early excavation records, and a lack of accurate, scientifically verified dates. The modern phasing most generally agreed to by archaeologists is detailed below. Features mentioned in the text are numbered and shown on the plan, right.

Before the monument (from 8000 BC)

Archaeologists have found four, or possibly five, largeMesolithic

The Mesolithic (Greek: μέσος, ''mesos'' 'middle' + λίθος, ''lithos'' 'stone') or Middle Stone Age is the Old World archaeological period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The term Epipaleolithic is often used synonymous ...

posthole

In archaeology a posthole or post-hole is a cut feature used to hold a surface timber or stone. They are usually much deeper than they are wide; however, truncation may not make this apparent. Although the remains of the timber may survive, most p ...

s (one may have been a natural tree throw

In botany, a tree is a perennial plant with an elongated stem, or trunk, usually supporting branches and leaves. In some usages, the definition of a tree may be narrower, including only woody plants with secondary growth, plants that are u ...

), which date to around 8000 BC, beneath the nearby old tourist car-park in use until 2013. These held pine posts around in diameter, which were erected and eventually rotted ''in situ''. Three of the posts (and possibly four) were in an east–west alignment which may have had ritual

A ritual is a sequence of activities involving gestures, words, actions, or objects, performed according to a set sequence. Rituals may be prescribed by the traditions of a community, including a religious community. Rituals are characterized, b ...

significance. Another Mesolithic astronomical site in Britain is the Warren Field

Warren Field is the location of a mesolithic calendar monument built about 8,000 BCE.

It includes 12 pits believed to correlate with phases of the Moon and used as a lunar calendar. It is considered to be the oldest lunar calendar yet found. It ...

site in Aberdeenshire

Aberdeenshire ( sco, Aiberdeenshire; gd, Siorrachd Obar Dheathain) is one of the 32 Subdivisions of Scotland#council areas of Scotland, council areas of Scotland.

It takes its name from the County of Aberdeen which has substantially differe ...

, which is considered the world's oldest lunar calendar

A lunar calendar is a calendar based on the monthly cycles of the Moon's phases (synodic months, lunations), in contrast to solar calendars, whose annual cycles are based only directly on the solar year. The most commonly used calendar, the Gre ...

, corrected yearly by observing the midwinter solstice

The winter solstice, also called the hibernal solstice, occurs when either of Earth's poles reaches its maximum tilt away from the Sun. This happens twice yearly, once in each hemisphere ( Northern and Southern). For that hemisphere, the winte ...

. Similar but later sites have been found in Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion#Europe, subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, ...

. A settlement that may have been contemporaneous with the posts has been found at Blick Mead

Blick Mead is a chalkland spring in Wiltshire, England, separated by the River Avon from the northwest edge of the town of Amesbury. It is close to an Iron Age hillfort known as Vespasian's Camp and about a mile east of the Stonehenge ancient ...

, a reliable year-round spring from Stonehenge.

Salisbury Plain

Salisbury Plain is a chalk plateau in the south western part of central southern England covering . It is part of a system of chalk downlands throughout eastern and southern England formed by the rocks of the Chalk Group and largely lies wi ...

was then still wooded, but 4,000 years later, during the earlier Neolithic, people built a causewayed enclosure

A causewayed enclosure is a type of large prehistoric earthwork common to the early Neolithic in Europe. It is an enclosure marked out by ditches and banks, with a number of causeways crossing the ditches. More than 100 examples are recorded in ...

at Robin Hood's Ball

Robin Hood’s Ball is a Neolithic causewayed enclosure on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, England, approximately northwest of the town of Amesbury, and northwest of Stonehenge. The site was designated as a scheduled monument in 1965.

Etymology ...

, and long barrow

Long barrows are a style of monument constructed across Western Europe in the fifth and fourth millennia BCE, during the Early Neolithic period. Typically constructed from earth and either timber or stone, those using the latter material repres ...

tombs in the surrounding landscape. In approximately 3500 BC, a Stonehenge Cursus

The Stonehenge Cursus (sometimes known as the Greater Cursus) is a large Neolithic cursus monument on Salisbury plain, near to Stonehenge in Wiltshire, England. It is roughly long and between and wide. Excavations in 2007 dated the construct ...

was built north of the site as the first farmers began to clear the trees and develop the area. Other previously overlooked stone or wooden structures and burial mounds may date as far back as 4000 BC. Charcoal from the ‘Blick Mead’ camp from Stonehenge (near the Vespasian's Camp site) has been dated to 4000 BC. The University of Buckingham

, mottoeng = Flying on Our Own Wings

, established = 1973; as university college1983; as university

, type = Private

, endowment =

, administrative_staff = 97 academic, 103 support

, chance ...

's Humanities Research Institute believes that the community who built Stonehenge lived here over a period of several millennia, making it potentially "one of the pivotal places in the history of the Stonehenge landscape."

Stonehenge 1 (c. 3100 BC)

The first monument consisted of a circular bank and ditch

The first monument consisted of a circular bank and ditch enclosure

Enclosure or Inclosure is a term, used in English landownership, that refers to the appropriation of "waste" or " common land" enclosing it and by doing so depriving commoners of their rights of access and privilege. Agreements to enclose land ...

made of Late Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the younger of two epochs into which the Cretaceous Period is divided in the geologic time scale. Rock strata from this epoch form the Upper Cretaceous Series. The Cretaceous is named after ''creta'', the ...

(Santonian

The Santonian is an age in the geologic timescale or a chronostratigraphic stage. It is a subdivision of the Late Cretaceous Epoch or Upper Cretaceous Series. It spans the time between 86.3 ± 0.7 mya (million years ago) and 83.6 ± 0.7 mya. The ...

Age) Seaford chalk

Chalk is a soft, white, porous, sedimentary carbonate rock. It is a form of limestone composed of the mineral calcite and originally formed deep under the sea by the compression of microscopic plankton that had settled to the sea floor. Chalk ...

, measuring about in diameter, with a large entrance to the north east and a smaller one to the south. It stood in open grassland

A grassland is an area where the vegetation is dominated by grasses (Poaceae). However, sedge (Cyperaceae) and rush (Juncaceae) can also be found along with variable proportions of legumes, like clover, and other herbs. Grasslands occur natur ...

on a slightly sloping spot. The builders placed the bones of deer

Deer or true deer are hoofed ruminant mammals forming the family Cervidae. The two main groups of deer are the Cervinae, including the muntjac, the elk (wapiti), the red deer, and the fallow deer; and the Capreolinae, including the reindeer ...

and oxen in the bottom of the ditch, as well as some worked flint

Flint, occasionally flintstone, is a sedimentary cryptocrystalline form of the mineral quartz, categorized as the variety of chert that occurs in chalk or marly limestone. Flint was widely used historically to make stone tools and start fir ...

tools. The bones were considerably older than the antler picks used to dig the ditch, and the people who buried them had looked after them for some time prior to burial. The ditch was continuous but had been dug in sections, like the ditches of the earlier causewayed enclosures in the area. The chalk dug from the ditch was piled up to form the bank. This first stage is dated to around 3100 BC, after which the ditch began to silt up naturally. Within the outer edge of the enclosed area is a circle of 56 pits, each about in diameter, known as the Aubrey holes

The Aubrey holes are a ring of fifty-six (56) chalk pits at Stonehenge, named after the seventeenth-century antiquarian John Aubrey. They date to the earliest phases of Stonehenge in the late fourth and early third millennium BC. Despite decade ...

after John Aubrey

John Aubrey (12 March 1626 – 7 June 1697) was an English antiquary, natural philosopher and writer. He is perhaps best known as the author of the ''Brief Lives'', his collection of short biographical pieces. He was a pioneer archaeologist, ...

, the seventeenth-century antiquarian

An antiquarian or antiquary () is an fan (person), aficionado or student of antiquities or things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient artifact (archaeology), artifac ...

who was thought to have first identified them. These pits and the bank and ditch together are known as the Palisade or Gate Ditch. The pits may have contained standing timbers creating a timber circle

In archaeology, timber circles are rings of upright wooden posts, built mainly by ancient peoples in the British Isles and North America. They survive only as gapped rings of post-holes, with no evidence they formed walls, making them distinct fro ...

, although there is no excavated evidence of them. A recent excavation has suggested that the Aubrey Holes may have originally been used to erect a bluestone

Bluestone is a cultural or commercial name for a number of dimension or building stone varieties, including:

* basalt in Victoria, Australia, and in New Zealand

* dolerites in Tasmania, Australia; and in Britain (including Stonehenge)

* felds ...

circle. If this were the case, it would advance the earliest known stone structure at the monument by some 500 years.

In 2013 a team of archaeologists, led by Mike Parker Pearson

Michael Parker Pearson, (born 26 June 1957) is an English archaeologist specialising in the study of the Neolithic British Isles, Madagascar and the archaeology of death and burial. A professor at the UCL Institute of Archaeology, he previous ...

, excavated more than 50,000 cremated bone fragments, from 63 individuals, buried at Stonehenge. These remains had originally been buried individually in the Aubrey holes, exhumed during a previous excavation conducted by William Hawley

Lieutenant-Colonel William Hawley (1851–1941) was a British archaeologist who undertook pioneering excavations at Stonehenge.

Military career

Hawley joined the Royal Engineers and was a captain of the Portsmouth division of the Royal Engin ...

in 1920, been considered unimportant by him, and subsequently re-interred together in one hole, Aubrey Hole 7, in 1935. Physical and chemical analysis of the remains has shown that the cremated were almost equally men and women, and included some children. As there was evidence of the underlying chalk beneath the graves being crushed by substantial weight, the team concluded that the first bluestones brought from Wales were probably used as grave markers. Radiocarbon dating

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of radiocarbon, a radioactive isotope of carbon.

The method was dev ...

of the remains has put the date of the site 500 years earlier than previously estimated, to around 3000 BC. A 2018 study of the strontium

Strontium is the chemical element with the symbol Sr and atomic number 38. An alkaline earth metal, strontium is a soft silver-white yellowish metallic element that is highly chemically reactive. The metal forms a dark oxide layer when it is ex ...

content of the bones found that many of the individuals buried there around the time of construction had probably come from near the source of the bluestone in Wales and had not extensively lived in the area of Stonehenge before death.

Between 2017 and 2021, studies by Professor Pearson (UCL) and his team suggested that the bluestone

Bluestone is a cultural or commercial name for a number of dimension or building stone varieties, including:

* basalt in Victoria, Australia, and in New Zealand

* dolerites in Tasmania, Australia; and in Britain (including Stonehenge)

* felds ...

s used in Stonehenge had been moved there following dismantling of a stone circle of identical size to the first known Stonehenge circle (110m) at the Welsh site of Waun Mawn

Waun Mawn (Welsh for "peat moor") is the site of a possible dismantled Neolithic stone circle in the Preseli Hills of Pembrokeshire, Wales. The diameter of the postulated circle is estimated to be , the third largest diameter for a British stone c ...

in the Preseli Hills

The Preseli Hills or, as they are known locally and historically, Preseli Mountains, (Welsh: ''Mynyddoedd y Preseli / Y Preselau'' , ) is a range of hills in western Wales, mostly within the Pembrokeshire Coast National Park.

The range stret ...

. It had contained bluestones, one of which showed evidence of having been reused in Stonehenge. The stone was identified by its unusual pentagonal shape and by luminescence soil dating from the filled-in sockets which showed the circle had been erected around 3400-3200 BC, and dismantled around 300–400 years later, consistent with the dates attributed to the creation of Stonehenge. The cessation of human activity in that area at the same time suggested migration as a reason, but it is believed that other stones may have come from other sources.

Stonehenge 2 (c. 2900 BC)

The second phase of construction occurred approximately between 2900 and 2600 BC. The number of postholes dating to the early third millennium BC suggests that some form of timber structure was built within the enclosure during this period. Further standing timbers were placed at the northeast entrance, and a parallel alignment of posts ran inwards from the southern entrance. The postholes are smaller than the Aubrey Holes, being only around in diameter, and are much less regularly spaced. The bank was purposely reduced in height and the ditch continued to silt up. At least twenty-five of the Aubrey Holes are known to have contained later, intrusive,cremation

Cremation is a method of Disposal of human corpses, final disposition of a Cadaver, dead body through Combustion, burning.

Cremation may serve as a funeral or post-funeral rite and as an alternative to burial. In some countries, including India ...

burials dating to the two centuries after the monument's inception. It seems that whatever the holes' initial function, it changed to become a funerary one during Phase two. Thirty further cremations were placed in the enclosure's ditch and at other points within the monument, mostly in the eastern half. Stonehenge is therefore interpreted as functioning as an enclosed cremation cemetery

Enclosed cremation cemetery is a term used by archaeologists to describe a type of cemetery found in north western Europe during the late Neolithic and early Bronze Age. They are similar to urnfield burial grounds in that they consist of a concen ...

at this time, the earliest known cremation cemetery in the British Isles. Fragments of unburnt human bone have also been found in the ditch-fill. Dating evidence is provided by the late Neolithic grooved ware

Grooved ware is the name given to a pottery style of the British Neolithic. Its manufacturers are sometimes known as the Grooved ware people. Unlike the later Beaker ware, Grooved culture was not an import from the continent but seems to have dev ...

pottery that has been found in connection with the features from this phase.

Stonehenge 3 I (c. 2600 BC)

Archaeological excavation has indicated that around 2600 BC, the builders abandoned timber in favour of stone and dug two concentric arrays of holes (the Q and R Holes) in the centre of the site. These stone sockets are only partly known (hence on present evidence are sometimes described as forming 'crescents'); however, they could be the remains of a double ring. Again, there is little firm dating evidence for this phase. The holes held up to 80 standing stones (shown blue on the plan), only 43 of which can be traced today. It is generally accepted that the

Archaeological excavation has indicated that around 2600 BC, the builders abandoned timber in favour of stone and dug two concentric arrays of holes (the Q and R Holes) in the centre of the site. These stone sockets are only partly known (hence on present evidence are sometimes described as forming 'crescents'); however, they could be the remains of a double ring. Again, there is little firm dating evidence for this phase. The holes held up to 80 standing stones (shown blue on the plan), only 43 of which can be traced today. It is generally accepted that the bluestone

Bluestone is a cultural or commercial name for a number of dimension or building stone varieties, including:

* basalt in Victoria, Australia, and in New Zealand

* dolerites in Tasmania, Australia; and in Britain (including Stonehenge)

* felds ...

s (some of which are made of dolerite

Diabase (), also called dolerite () or microgabbro,

is a mafic, holocrystalline, subvolcanic rock equivalent to volcanic basalt or plutonic gabbro. Diabase dikes and sills are typically shallow intrusive bodies and often exhibit fine-grained ...

, an igneous rock), were transported by the builders from the Preseli Hills

The Preseli Hills or, as they are known locally and historically, Preseli Mountains, (Welsh: ''Mynyddoedd y Preseli / Y Preselau'' , ) is a range of hills in western Wales, mostly within the Pembrokeshire Coast National Park.

The range stret ...

, away in modern-day Pembrokeshire

Pembrokeshire ( ; cy, Sir Benfro ) is a Local government in Wales#Principal areas, county in the South West Wales, south-west of Wales. It is bordered by Carmarthenshire to the east, Ceredigion to the northeast, and the rest by sea. The count ...

in Wales. Another theory is that they were brought much nearer to the site as glacial erratics

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate betw ...

by the Irish Sea Glacier

The Irish Sea Glacier was a huge glacier during the Pleistocene Ice Age that, probably on more than one occasion, flowed southwards from its source areas in Scotland and Ireland and across the Isle of Man, Anglesey and Pembrokeshire. It probab ...

although there is no evidence of glacial deposition within southern central England. A 2019 publication announced that evidence of Megalithic quarrying had been found at quarries in Wales identified as a source of Stonehenge's bluestone, indicating that the bluestone was quarried by human agency and not transported by glacial action.

The long-distance human transport theory was bolstered in 2011 by the discovery of a megalithic bluestone quarry at Craig Rhos-y-felin

Craig Rhos-y-felin is a rocky outcrop on the north side of the Preseli Mountains in Wales, which is designated as a RIGS site on the basis of its geological and geomorphological interest. It is accepted by some in the archaeological community tha ...

, near Crymych

Crymych () is a village of around 800 inhabitants and a community (population 1,739) in the northeast of Pembrokeshire, Wales. It is situated approximately above sea level at the eastern end of the Preseli Mountains, on the old Tenby to Cardiga ...

in Pembrokeshire, which is the most likely place for some of the stones to have been obtained. Other standing stones may well have been small sarsen

Sarsen stones are silicified sandstone blocks found in quantity in Southern England on Salisbury Plain and the Marlborough Downs in Wiltshire; in Kent; and in smaller quantities in Berkshire, Essex, Oxfordshire, Dorset, and Hampshire.

Geology ...

s (sandstone), used later as lintels. The stones, which weighed about two tons, could have been moved by lifting and carrying them on rows of poles and rectangular frameworks of poles, as recorded in China, Japan and India. It is not known whether the stones were taken directly from their quarries to Salisbury Plain or were the result of the removal of a venerated stone circle from Preseli to Salisbury Plain to "merge two sacred centres into one, to unify two politically separate regions, or to legitimise the ancestral identity of migrants moving from one region to another". Evidence of a 110-m stone circle at Waun Mawn

Waun Mawn (Welsh for "peat moor") is the site of a possible dismantled Neolithic stone circle in the Preseli Hills of Pembrokeshire, Wales. The diameter of the postulated circle is estimated to be , the third largest diameter for a British stone c ...

near Preseli, which could have contained some or all of the stones in Stonehenge, has been found, including a hole from a rock that matches the unusual cross-section of a Stonehenge bluestone "like a key in a lock". Each monolith measures around in height, between wide and around thick. What was to become known as the Altar Stone

An altar stone is a piece of natural stone containing relics in a cavity and intended to serve as the essential part of an altar for the celebration of Mass in the Catholic Church. Consecration by a bishop of the same rite was required. In the Byza ...

is almost certainly derived from the Senni Beds, perhaps from east of the Preseli Hills in the Brecon Beacons.

The north-eastern entrance was widened at this time, with the result that it precisely matched the direction of the midsummer sunrise and midwinter sunset of the period. This phase of the monument was abandoned unfinished, however; the small standing stones were apparently removed and the Q and R holes purposefully backfilled.

The Heel Stone

The Heel Stone is a single large block of sarsen stone standing within the Avenue outside the entrance of the Stonehenge earthwork in Wiltshire, England. In section it is sub-rectangular, with a minimum thickness of , rising to a tapered to ...

, a Tertiary

Tertiary ( ) is a widely used but obsolete term for the geologic period from 66 million to 2.6 million years ago.

The period began with the demise of the non-avian dinosaurs in the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, at the start ...

sandstone, may also have been erected outside the north-eastern entrance during this period. It cannot be accurately dated and may have been installed at any time during phase 3. At first, it was accompanied by a second stone, which is no longer visible. Two, or possibly three, large portal stones

This article describes several characteristic architectural elements typical of European megalithic (Stone Age) structures.

Forecourt

In archaeology, a forecourt is the name given to the area in front of certain types of chamber tomb. Forecourts ...

were set up just inside the north-eastern entrance, of which only one, the fallen Slaughter Stone, long, now remains. Other features, loosely dated to phase 3, include the four Station Stones, two of which stood atop mounds. The mounds are known as " barrows" although they do not contain burials. Stonehenge Avenue

Stonehenge Avenue is an ancient avenue on Salisbury plain, Wiltshire, England. It is part of the Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites UNESCO World Heritage Site. Discovered in the 18th century, it measures nearly 3 kilometers, connecting Ston ...

, a parallel pair of ditches and banks leading to the River Avon, was also added.

Stonehenge 3 II (2600 BC to 2400 BC)

During the next major phase of activity, 30 enormous

During the next major phase of activity, 30 enormous Oligocene

The Oligocene ( ) is a geologic epoch of the Paleogene Period and extends from about 33.9 million to 23 million years before the present ( to ). As with other older geologic periods, the rock beds that define the epoch are well identified but the ...

–Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and means "less recen ...

sarsen stones (shown grey on the plan) were brought to the site. They came from a quarry around north of Stonehenge, in West Woods

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some R ...

, Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

. The stones were dressed and fashioned with mortise and tenon

A mortise and tenon (occasionally mortice and tenon) joint connects two pieces of wood or other material. Woodworkers around the world have used it for thousands of years to join pieces of wood, mainly when the adjoining pieces connect at right ...

joints before 30 sarsens were erected as a diameter circle of standing stones, with a ring of 30 lintel stones resting on top. The lintels were fitted to one another using tongue and groove

Tongue and groove is a method of fitting similar objects together, edge to edge, used mainly with wood, in flooring, parquetry, panelling, and similar constructions. Tongue and groove joints allow two flat pieces to be joined strongly together t ...

joints – a woodworking method, again. Each standing stone was around high, wide and weighed around 25 tons. Each had clearly been worked with the final visual effect in mind: The orthostat

This article describes several characteristic architectural elements typical of European megalithic (Stone Age) structures.

Forecourt

In archaeology, a forecourt is the name given to the area in front of certain types of chamber tomb. Forecourts ...

s widen slightly towards the top in order that their perspective remains constant when viewed from the ground, while the lintel stones curve slightly to continue the circular appearance of the earlier monument.

The inward-facing surfaces of the stones are smoother and more finely worked than the outer surfaces. The average thickness of the stones is and the average distance between them is . A total of 75 stones would have been needed to complete the circle (60 stones) and the trilithon horseshoe (15 stones). It was thought the ring might have been left incomplete, but an exceptionally dry summer in 2013 revealed patches of parched grass which may correspond to the location of missing sarsens. The lintel stones are each around long, wide and thick. The tops of the lintels are above the ground.

Within this circle stood five trilithon

A trilithon or trilith is a structure consisting of two large vertical stones (posts) supporting a third stone set horizontally across the top (lintel). It is commonly used in the context of megalithic monuments. The most famous trilithons ar ...

s of dressed sarsen

Sarsen stones are silicified sandstone blocks found in quantity in Southern England on Salisbury Plain and the Marlborough Downs in Wiltshire; in Kent; and in smaller quantities in Berkshire, Essex, Oxfordshire, Dorset, and Hampshire.

Geology ...

stone arranged in a horseshoe shape across, with its open end facing northeast. These huge stones, ten uprights and five lintels, weigh up to 50 tons each. They were linked using complex jointing. They are arranged symmetrically. The smallest pair of trilithons were around tall, the next pair a little higher, and the largest, single trilithon in the south-west corner would have been tall. Only one upright from the Great Trilithon still stands, of which is visible and a further is below ground. The images of a 'dagger' and 14 'axeheads' have been carved on one of the sarsens, known as stone 53; further carvings of axeheads have been seen on the outer faces of stones 3, 4, and 5. The carvings are difficult to date but are morphologically similar to late Bronze Age weapons. Early 21st century laser scanning of the carvings supports this interpretation. The pair of trilithons in the north east are smallest, measuring around in height; the largest, which is in the south-west of the horseshoe, is almost tall.

This ambitious phase has been radiocarbon dated

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of radiocarbon, a radioactive isotope of carbon.

The method was dev ...

to between 2600 and 2400 BC, slightly earlier than the Stonehenge Archer, discovered in the outer ditch of the monument in 1978, and the two sets of burials, known as the Amesbury Archer

The Amesbury Archer is an early Bronze Age (Bell Beaker) man whose grave was discovered during excavations at the site of a new housing development () in Amesbury near Stonehenge. The grave was uncovered in May 2002. The man was middle aged ...

and the Boscombe Bowmen

The Boscombe Bowmen is the name given by archaeologists to a group of early Bronze Age people found in a shared burial at Boscombe Down in Amesbury () near Stonehenge in Wiltshire, England.

Discovery

The burials were found in 2003 during roadwork ...

, discovered to the west. Analysis of animal teeth found away at Durrington Walls

Durrington Walls is the site of a large Neolithic settlement and later henge enclosure located in the Stonehenge World Heritage Site in England. It lies north-east of Stonehenge in the parish of Durrington, just north of Amesbury in Wiltshir ...

, thought by Parker Pearson to be the 'builders camp', suggests that, during some period between 2600 and 2400 BC, as many as 4,000 people gathered at the site for the mid-winter and mid-summer festivals; the evidence showed that the animals had been slaughtered around nine months or 15 months after their spring birth. Strontium

Strontium is the chemical element with the symbol Sr and atomic number 38. An alkaline earth metal, strontium is a soft silver-white yellowish metallic element that is highly chemically reactive. The metal forms a dark oxide layer when it is ex ...

isotope analysis

Isotope analysis is the identification of isotopic signature, abundance of certain stable isotopes of chemical elements within organic and inorganic compounds. Isotopic analysis can be used to understand the flow of energy through a food web ...

of the animal teeth showed that some had been brought from as far afield as the Scottish Highlands for the celebrations.

At about the same time, a large timber circle

In archaeology, timber circles are rings of upright wooden posts, built mainly by ancient peoples in the British Isles and North America. They survive only as gapped rings of post-holes, with no evidence they formed walls, making them distinct fro ...

and a second avenue were constructed at Durrington Walls

Durrington Walls is the site of a large Neolithic settlement and later henge enclosure located in the Stonehenge World Heritage Site in England. It lies north-east of Stonehenge in the parish of Durrington, just north of Amesbury in Wiltshir ...

overlooking the River Avon. The timber circle was orientated towards the rising Sun on the midwinter solstice

The winter solstice, also called the hibernal solstice, occurs when either of Earth's poles reaches its maximum tilt away from the Sun. This happens twice yearly, once in each hemisphere ( Northern and Southern). For that hemisphere, the winte ...

, opposing the solar alignments at Stonehenge. The avenue was aligned with the setting Sun on the summer solstice

The summer solstice, also called the estival solstice or midsummer, occurs when one of Earth's poles has its maximum tilt toward the Sun. It happens twice yearly, once in each hemisphere ( Northern and Southern). For that hemisphere, the summer ...

and led from the river to the timber circle. Evidence of huge fires on the banks of the Avon between the two avenues also suggests that both circles were linked. They were perhaps used as a procession route on the longest and shortest days of the year. Parker Pearson speculates that the wooden circle at Durrington Walls was the centre of a 'land of the living', whilst the stone circle represented a 'land of the dead', with the Avon serving as a journey between the two.

Stonehenge 3 III (2400 BC to 2280 BC)

Later in theBronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

, although the exact details of activities during this period are still unclear, the bluestones appear to have been re-erected. They were placed within the outer sarsen circle and may have been trimmed in some way. Like the sarsens, a few have timber-working style cuts in them suggesting that, during this phase, they may have been linked with lintels and were part of a larger structure.

Stonehenge 3 IV (2280 BC to 1930 BC)

This phase saw further rearrangement of the bluestones. They were arranged in a circle between the two rings of sarsens and in an oval at the centre of the inner ring. Some archaeologists argue that some of these bluestones were from a second group brought from Wales. All the stones formed well-spaced uprights without any of the linking lintels inferred in Stonehenge 3 III. The Altar Stone may have been moved within the oval at this time and re-erected vertically. Although this would seem the most impressive phase of work, Stonehenge 3 IV was rather shabbily built compared to its immediate predecessors, as the newly re-installed bluestones were not well-founded and began to fall over. However, only minor changes were made after this phase.

Stonehenge 3 V (1930 BC to 1600 BC)

Soon afterwards, the northeastern section of the Phase 3 IV bluestone circle was removed, creating a horseshoe-shaped setting (the Bluestone Horseshoe) which mirrored the shape of the central sarsen Trilithons. This phase is contemporary with theSeahenge

Seahenge, also known as Holme I, was a prehistoric monument located in the village of Holme-next-the-Sea, near Old Hunstanton in the English county of Norfolk. A timber circle with an upturned tree root in the centre, Seahenge, along wi ...

site in Norfolk.

After the monument (1600 BC on)

The Y and Z Holes are the last known construction at Stonehenge, built about 1600 BC, and the last usage of it was probably during theIron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

. Roman coins

Roman currency for most of Roman history consisted of gold, silver, bronze, orichalcum and copper coinage. From its introduction to the Republic, during the third century BC, well into Imperial times, Roman currency saw many changes in form, denomi ...

and medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the Post-classical, post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with t ...

artefacts have all been found in or around the monument but it is unknown if the monument was in continuous use throughout British prehistory and beyond, or exactly how it would have been used. Notable is the massive Iron Age hillfort

A hillfort is a type of earthwork used as a fortified refuge or defended settlement, located to exploit a rise in elevation for defensive advantage. They are typically European and of the Bronze Age or Iron Age. Some were used in the post-Roma ...

known as Vespasian's Camp (despite its name, not a Roman site) built alongside the Avenue near the Avon. A decapitated seventh-century Saxon

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

man was excavated from Stonehenge in 1923. The site was known to scholars during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

and since then it has been studied and adopted by numerous groups.

Function and construction

Stonehenge was produced by a culture that left no written records. Many aspects of Stonehenge, such as how it was built and for what purposes it was used, remain subject to debate. A number of myths surround the stones. The site, specifically the great trilithon, the encompassing horseshoe arrangement of the five central trilithons, the heel stone, and the embanked avenue, are aligned to the sunset of the winter solstice and the opposing sunrise of the summer solstice. A natural landform at the monument's location followed this line, and may have inspired its construction. The excavated remains of culled animal bones suggest that people may have gathered at the site for the winter rather than the summer. Further astronomical associations, and the precise astronomical significance of the site for its people, are a matter of speculation and debate. There is little or no direct evidence revealing the construction techniques used by the Stonehenge builders. Over the years, various authors have suggested that supernatural or anachronistic methods were used, usually asserting that the stones were impossible to move otherwise due to their massive size. However, conventional techniques, using Neolithic technology as basic asshear legs

Shear legs, also known as sheers, shears, or sheer legs, are a form of two-legged lifting device. Shear legs may be permanent, formed of a solid A-frame and supports, as commonly seen on land and the floating sheerleg, or temporary, as aboard a ...

, have been demonstrably effective at moving and placing stones of a similar size. The most common theory of how prehistoric people moved megaliths has them creating a track of logs which the large stones were rolled along. Another megalith transport theory involves the use of a type of sleigh running on a track greased with animal fat. Such an experiment with a sleigh carrying a 40-ton slab of stone was successfully conducted near Stonehenge in 1995. A team of more than 100 workers managed to push and pull the slab along the journey from the Marlborough Downs

The North Wessex Downs Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) is located in the English counties of Berkshire, Hampshire, Oxfordshire and Wiltshire. The name ''North Wessex Downs'' is not a traditional one, the area covered being better kno ...

.

Proposed functions for the site include usage as an astronomical observatory or as a religious site. In the 1960s Gerald Hawkins

Gerald Stanley Hawkins (20 April 1928– 26 May 2003) was a British-born American astronomer and author noted for his work in the field of archaeoastronomy. A professor and chair of the astronomy department at Boston University in the Unit ...

described in detail how the site was apparently set out to observe the sun and moon over a recurring 56-year cycle. More recently two major new theories have been proposed. Geoffrey Wainwright

Geoffrey Wainwright (1939 – 17 March 2020) was an English theologian. He spent much of his career in the United States and taught at Duke Divinity School. Wainwright made major contributions to modern Methodist theology and Christian liturgy, ...

, president of the Society of Antiquaries of London

A society is a group of individuals involved in persistent social interaction, or a large social group sharing the same spatial or social territory, typically subject to the same political authority and dominant cultural expectations. Societ ...

, and Timothy Darvill, of Bournemouth University

Bournemouth University is a public university in Bournemouth, England, with its main campus situated in neighbouring Poole. The university was founded in 1992; however, the origins of its predecessor date back to the early 1900s.

The univer ...

, have suggested that Stonehenge was a place of healing—the primeval equivalent of Lourdes

Lourdes (, also , ; oc, Lorda ) is a market town situated in the Pyrenees. It is part of the Hautes-Pyrénées department in the Occitanie region in southwestern France. Prior to the mid-19th century, the town was best known for the Château ...

. They argue that this accounts for the high number of burials in the area and for the evidence of trauma deformity in some of the graves. However, they do concede that the site was probably multifunctional and used for ancestor worship as well. Isotope analysis indicates that some of the buried individuals were from other regions. A teenage boy buried approximately 1550 BC was raised near the Mediterranean Sea; a metal worker from 2300 BC dubbed the "Amesbury Archer

The Amesbury Archer is an early Bronze Age (Bell Beaker) man whose grave was discovered during excavations at the site of a new housing development () in Amesbury near Stonehenge. The grave was uncovered in May 2002. The man was middle aged ...

" grew up near the Alpine foothills of Germany; and the "Boscombe Bowmen

The Boscombe Bowmen is the name given by archaeologists to a group of early Bronze Age people found in a shared burial at Boscombe Down in Amesbury () near Stonehenge in Wiltshire, England.

Discovery

The burials were found in 2003 during roadwork ...

" probably arrived from Wales or Brittany, France.

On the other hand, Mike Parker Pearson of Sheffield University

, mottoeng = To discover the causes of things

, established = – University of SheffieldPredecessor institutions:

– Sheffield Medical School – Firth College – Sheffield Technical School – University College of Sheffield

, type = Pu ...

has suggested that Stonehenge was part of a ritual landscape Ritual landscapes or ceremonial landscapes are large archaeological areas that were seemingly dedicated to ceremonial purposes in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages. Most are dated to around 3500–1800 BC, though a mustatil in Arabia has been dated to ...

and was joined to Durrington Walls by their corresponding avenues and the River Avon. He suggests that the area around Durrington Walls Henge was a place of the living, whilst Stonehenge was a domain of the dead. A journey along the Avon to reach Stonehenge was part of a ritual passage from life to death, to celebrate past ancestors and the recently deceased. Both explanations were first mooted in the twelfth century by Geoffrey of Monmouth

Geoffrey of Monmouth ( la, Galfridus Monemutensis, Galfridus Arturus, cy, Gruffudd ap Arthur, Sieffre o Fynwy; 1095 – 1155) was a British cleric from Monmouth, Wales and one of the major figures in the development of British historiograph ...

, who extolled the curative properties of the stones and was also the first to advance the idea that Stonehenge was constructed as a funerary monument. Whatever religious, mystical or spiritual elements were central to Stonehenge, its design includes a celestial observatory function, which might have allowed prediction of eclipse, solstice, equinox and other celestial events important to a contemporary religion.

There are other hypotheses and theories. According to a team of British researchers led by Mike Parker Pearson of the University of Sheffield, Stonehenge may have been built as a symbol of "peace and unity", indicated in part by the fact that at the time of its construction, Britain's Neolithic people were experiencing a period of cultural unification.

Stonehenge megaliths include smaller bluestones and larger sarsens (a term for silicified sandstone boulders found in the chalk downs of southern England). The bluestones are composed of dolerite, tuff, rhyolite, or sandstone. The igneous bluestones appear to have originated in the Preseli hills of southwestern Wales about from the monument. The sandstone Altar Stone may have originated in east Wales. Recent analysis has indicated the sarsens originated from West Woods

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some R ...

, about from the monument.

Researchers from the Royal College of Art in London have discovered that the monument's igneous bluestones possess "unusual acoustic properties" – when struck they respond with a "loud clanging noise". Rocks with such acoustic properties are frequent in the Carn Melyn ridge of Presili; the Presili village of Maenclochog

Maenclochog () is a village, parish and Community (Wales), community in Pembrokeshire, south-west Wales. It is also the name of Maenclochog (electoral ward), an electoral ward comprising a wider area of four surrounding communities. Maenclocho ...

(Welsh for bell or ringing stones), used local bluestones as church bells until the 18th century. According to the team, these acoustic properties could explain why certain bluestones were hauled such a long distance, a major technical accomplishment at the time. In certain ancient cultures, rocks that ring out, known as lithophonic rocks, were believed to contain mystic or healing powers, and Stonehenge has a history of association with rituals. The presence of these "ringing rocks" seems to support the hypothesis that Stonehenge was a "place for healing" put forward by Darvill, who consulted with the researchers.

DNA studies clarify the historical context

Researchers studying DNA extracted from Neolithic human remains across Britain determined that the ancestors of the people who built Stonehenge were

Researchers studying DNA extracted from Neolithic human remains across Britain determined that the ancestors of the people who built Stonehenge were early European farmers

Early European Farmers (EEF), First European Farmers (FEF), Neolithic European Farmers, Ancient Aegean Farmers, or Anatolian Neolithic Farmers (ANF) are names used to describe a distinct group of early Neolithic farmers who brought agriculture to E ...

who came from the Eastern Mediterranean, travelling west from there, as well as Western hunter-gatherers

In archaeogenetics, the term Western Hunter-Gatherer (WHG), West European Hunter-Gatherer or Western European Hunter-Gatherer names a distinct ancestral component of modern Europeans, representing descent from a population of Mesolithic hunter-gat ...

from western Europe. DNA studies indicate that they had a predominantly Aegean ancestry, although their agricultural techniques seem to have come originally from Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

. These Aegean farmers then moved to Iberia

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

before heading north, reaching Britain in about 4,000 BC.Paul RinconStonehenge: DNA reveals origin of builders.

BBC News website, 16 April 2019 Neolithic individuals in the British Isles were close to Iberian and Central European Early and Middle Neolithic populations, modelled as having about 75% ancestry from Aegean farmers with the rest coming from Western Hunter-Gatherers in continental Europe. They subsequently replaced most of the hunter-gatherer population in the British Isles without mixing much with them. At that time, Britain was inhabited by groups of hunter-gatherers who were the first inhabitants of the island after the last Ice Age ended about 11,700 years ago. Despite their mostly Aegean ancestry, the paternal (Y-DNA) lineages of Neolithic farmers in Britain were almost exclusively of Western Hunter-Gatherer origin. This was also the case among other megalithic-building populations in northwest Europe, meaning that these populations were descended from a mixture of hunter-gatherer males and farmer females. This mixture appears to have happened primarily on the continent before the Neolithic farmers migrated to Britain. The dominance of Western Hunter-Gatherer male lineages in Britain and northwest Europe is also reflected in a general 'resurgence' of hunter-gatherer ancestry, predominantly from males, across western and central Europe in the Middle Neolithic. The Bell Beaker people arrived later, around 2,500 BC, migrating from mainland Europe. The earliest British beakers, most likely speakers of

Indo-European languages

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Dutc ...

whose ancestors migrated from the Pontic–Caspian steppe, were similar to those from the Rhine. There was again a large population replacement in Britain. More than 90% of Britain's Neolithic gene pool was replaced with the arrival of the Bell Beaker people, who had approximately 50% WSH ancestry. The Bell Beakers also left their impact on Stonehenge construction. They are also associated with the Wessex culture

The Wessex culture is the predominant prehistoric culture of central and southern Britain during the early Bronze Age, originally defined by the British archaeologist Stuart Piggott in 1938.Mycenaean Greece

Mycenaean Greece (or the Mycenaean civilization) was the last phase of the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in ...

. The wealth from such trade probably permitted the Wessex people to construct the second and third (''megalithic'') phases of Stonehenge and also indicates a powerful form of social organisation.

The Bell Beakers were also associated with the tin

Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn (from la, stannum) and atomic number 50. Tin is a silvery-coloured metal.

Tin is soft enough to be cut with little force and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, t ...

trade, which was Britain's only unique export at the time. Tin was important because it was used to turn copper into bronze, and the Beakers derived much wealth from this.

Modern history

Folklore

"Heel Stone", "Friar’s Heel", or "Sun-Stone"

The

The Heel Stone

The Heel Stone is a single large block of sarsen stone standing within the Avenue outside the entrance of the Stonehenge earthwork in Wiltshire, England. In section it is sub-rectangular, with a minimum thickness of , rising to a tapered to ...

lies northeast of the sarsen circle, beside the end portion of Stonehenge Avenue. It is a rough stone, above ground, leaning inwards towards the stone circle. It has been known by many names in the past, including "Friar's Heel" and "Sun-stone". At the Summer solstice

The summer solstice, also called the estival solstice or midsummer, occurs when one of Earth's poles has its maximum tilt toward the Sun. It happens twice yearly, once in each hemisphere ( Northern and Southern). For that hemisphere, the summer ...