Stanisław August Poniatowski on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Stanisław II August (born Stanisław Antoni Poniatowski; 17 January 1732 – 12 February 1798), known also by his regnal Latin name Stanislaus II Augustus, was

Stanisław Antoni Poniatowski was born on 17 January 1732 in Wołczyn (then in the

Stanisław Antoni Poniatowski was born on 17 January 1732 in Wołczyn (then in the

King of Poland

Poland was ruled at various times either by dukes and princes (10th to 14th centuries) or by kings (11th to 18th centuries). During the latter period, a tradition of free election of monarchs made it a uniquely electable position in Europe (16t ...

and Grand Duke of Lithuania

The monarchy of Lithuania concerned the monarchical head of state of Kingdom of Lithuania, Lithuania, which was established as an Absolute monarchy, absolute and hereditary monarchy. Throughout Lithuania's history there were three Duke, ducal D ...

from 1764 to 1795, and the last monarch of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi- confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Poland and Lithuania ...

.

Born into wealthy Polish aristocracy, Poniatowski arrived as a diplomat at the Russian imperial court in Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

in 1755 at the age of 22 and became intimately involved with the future empress Catherine the Great. With her connivance, he was elected King of Poland by the Polish Diet in September 1764 following the death of Augustus III. Contrary to expectations, Poniatowski attempted to reform and strengthen the large but ailing Commonwealth. His efforts were met with external opposition from neighbouring Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

, Russia and Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, all committed to keeping the Commonwealth weak. From within he was opposed by conservative interests, which saw the reforms as a threat to their traditional liberties and privileges

Privilege may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Privilege'' (film), a 1967 film directed by Peter Watkins

* ''Privilege'' (Ivor Cutler album), 1983

* ''Privilege'' (Television Personalities album), 1990

* ''Privilege (Abridged)'', an alb ...

granted centuries earlier.

The defining crisis of his early reign was the War of the Bar Confederation

The Bar Confederation ( pl, Konfederacja barska; 1768–1772) was an association of Polish nobles (szlachta) formed at the fortress of Bar in Podolia (now part of Ukraine) in 1768 to defend the internal and external independence of the Polish� ...

(1768–1772) that led to the First Partition of Poland (1772). The later part of his reign saw reforms wrought by the Diet (1788–1792) and the Constitution of 3 May 1791. These reforms were overthrown by the 1792 Targowica Confederation

The Targowica Confederation ( pl, konfederacja targowicka, , lt, Targovicos konfederacija) was a confederation established by Polish and Lithuanian magnates on 27 April 1792, in Saint Petersburg, with the backing of the Russian Empress Catheri ...

and by the Polish–Russian War of 1792

The Polish–Russian War of 1792 (also, War of the Second Partition, and in Polish sources, War in Defence of the Constitution ) was fought between the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth on one side, and the Targowica Confederation (conserva ...

, leading directly to the Second Partition of Poland

The 1793 Second Partition of Poland was the second of three partitions (or partial annexations) that ended the existence of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth by 1795. The second partition occurred in the aftermath of the Polish–Russian ...

(1793), the Kościuszko Uprising (1794) and the final and Third Partition of Poland

The Third Partition of Poland (1795) was the last in a series of the Partitions of Poland–Lithuania and the land of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth among Prussia, the Habsburg monarchy, and the Russian Empire which effectively ended Poli ...

(1795), marking the end of the Commonwealth. Stripped of all meaningful power, Poniatowski abdicated in November 1795 and spent the last years of his life as a captive in Saint Petersburg's Marble Palace.

A controversial figure in Poland's history, he is criticized primarily for his failure to resolutely stand against and prevent the partitions, which led to the destruction of the Polish state. On the other hand, he is remembered as a great patron of the arts and sciences who laid the foundation for the Commission of National Education, the first institution of its kind in the world, and sponsored many architectural landmarks.

Youth

Stanisław Antoni Poniatowski was born on 17 January 1732 in Wołczyn (then in the

Stanisław Antoni Poniatowski was born on 17 January 1732 in Wołczyn (then in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi- confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Poland and Lithuania ...

and now Voŭčyn, Belarus). He was one of eight surviving children, and the fourth son, of Princess Konstancja Czartoryska and of Count Stanisław Poniatowski, Ciołek coat of arms, Castellan

A castellan is the title used in Medieval Europe for an appointed official, a governor of a castle and its surrounding territory referred to as the castellany. The title of ''governor'' is retained in the English prison system, as a remnant o ...

of Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 159 ...

, who started as a Lithuanian

Lithuanian may refer to:

* Lithuanians

* Lithuanian language

* The country of Lithuania

* Grand Duchy of Lithuania

* Culture of Lithuania

* Lithuanian cuisine

* Lithuanian Jews as often called "Lithuanians" (''Lita'im'' or ''Litvaks'') by other Jew ...

domestic servant

A domestic worker or domestic servant is a person who works within the scope of a residence. The term "domestic service" applies to the equivalent occupational category. In traditional English contexts, such a person was said to be "in service ...

. His older brothers were Kazimierz Poniatowski (1721–1800), a Podkomorzy at Court, Franciszek Poniatowski (1723–1749), Canon of Wawel Cathedral who suffered from Epilepsy

Epilepsy is a group of non-communicable neurological disorders characterized by recurrent epileptic seizures. Epileptic seizures can vary from brief and nearly undetectable periods to long periods of vigorous shaking due to abnormal electrical ...

and Aleksander Poniatowski (1725–1744), an officer killed in the Rhineland-Palatinate

Rhineland-Palatinate ( , ; german: link=no, Rheinland-Pfalz ; lb, Rheinland-Pfalz ; pfl, Rhoilond-Palz) is a western state of Germany. It covers and has about 4.05 million residents. It is the ninth largest and sixth most populous of the ...

during the War of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession () was a European conflict that took place between 1740 and 1748. Fought primarily in Central Europe, the Austrian Netherlands, Italy, the Atlantic and Mediterranean, related conflicts included King George' ...

. His younger brothers were, Andrzej Poniatowski (1734–1773), an Austrian Feldmarschall

''Generalfeldmarschall'' (from Old High German ''marahscalc'', "marshal, stable master, groom"; en, general field marshal, field marshal general, or field marshal; ; often abbreviated to ''Feldmarschall'') was a rank in the armies of several ...

, Michał Jerzy Poniatowski (1736–94) who became Primate of Poland

This is a list of archbishops of the Archdiocese of Gniezno, who are simultaneously primates of Poland since 1418.Ludwika Zamoyska (1728–1804) and Izabella Branicka (1730–1808). Among his nephews was Prince

The following year Poniatowski was apprenticed to the office of Michał Fryderyk Czartoryski, the then Deputy Chancellor of Lithuania. In 1750, he travelled to

The following year Poniatowski was apprenticed to the office of Michał Fryderyk Czartoryski, the then Deputy Chancellor of Lithuania. In 1750, he travelled to  In Saint Petersburg, Williams introduced Poniatowski to the 26-year-old Catherine Alexeievna, the future empress Catherine the Great. The two became lovers. Whatever his feelings for Catherine, it is likely Poniatowski also saw an opportunity to use the relationship for his own benefit, using her influence to bolster his career.

Poniatowski had to leave St. Petersburg in July 1756 due to court intrigue. Through the combined influence of Catherine, of Russian empress Elizabeth and of chancellor

In Saint Petersburg, Williams introduced Poniatowski to the 26-year-old Catherine Alexeievna, the future empress Catherine the Great. The two became lovers. Whatever his feelings for Catherine, it is likely Poniatowski also saw an opportunity to use the relationship for his own benefit, using her influence to bolster his career.

Poniatowski had to leave St. Petersburg in July 1756 due to court intrigue. Through the combined influence of Catherine, of Russian empress Elizabeth and of chancellor

Upon the death of Poland's King Augustus III in October 1763, lobbying began for the election of the new king. Catherine threw her support behind Poniatowski. The Russians spent about 2.5m rubles in aid of his election. Poniatowski's supporters and opponents engaged in some military posturing and even minor clashes. In the end, the Russian army was deployed only a few kilometres from the election sejm, which met at

Upon the death of Poland's King Augustus III in October 1763, lobbying began for the election of the new king. Catherine threw her support behind Poniatowski. The Russians spent about 2.5m rubles in aid of his election. Poniatowski's supporters and opponents engaged in some military posturing and even minor clashes. In the end, the Russian army was deployed only a few kilometres from the election sejm, which met at  "Stanisław August", as he now styled himself combining the names of his two immediate royal predecessors, began his rule with only mixed support within the nation. It was mainly the small nobility who favoured his election. In his first years on the throne he attempted to introduce a number of reforms. He founded the Knights School, and began to form a diplomatic service, with semi-permanent diplomatic representatives throughout Europe, Russia and the

"Stanisław August", as he now styled himself combining the names of his two immediate royal predecessors, began his rule with only mixed support within the nation. It was mainly the small nobility who favoured his election. In his first years on the throne he attempted to introduce a number of reforms. He founded the Knights School, and began to form a diplomatic service, with semi-permanent diplomatic representatives throughout Europe, Russia and the

Although Poniatowski protested against the First Partition of the Commonwealth (1772), he was powerless to do anything about it. He considered

Although Poniatowski protested against the First Partition of the Commonwealth (1772), he was powerless to do anything about it. He considered

Reforms became possible again in the late 1780s. In the context of the wars being waged against the Ottoman Empire by both the

Reforms became possible again in the late 1780s. In the context of the wars being waged against the Ottoman Empire by both the

Shortly thereafter, conservative Polish nobility formed the

Shortly thereafter, conservative Polish nobility formed the

Poniatowski's plans had been ruined by the Kościuszko Uprising. The King had not encouraged it, but once it began he supported it, seeing no other honourable option. Its defeat marked the end of the Commonwealth. Poniatowski tried to govern the country in the brief period after the fall of the Uprising, but on 2 December 1794, Catherine demanded he leave Warsaw, a request to which he acceded on 7 January 1795, leaving the capital under Russian military escort and settling briefly in

Poniatowski's plans had been ruined by the Kościuszko Uprising. The King had not encouraged it, but once it began he supported it, seeing no other honourable option. Its defeat marked the end of the Commonwealth. Poniatowski tried to govern the country in the brief period after the fall of the Uprising, but on 2 December 1794, Catherine demanded he leave Warsaw, a request to which he acceded on 7 January 1795, leaving the capital under Russian military escort and settling briefly in  Poniatowski died of a stroke on 12 February 1798. Paul I sponsored a royal state funeral, and on 3 March he was buried at the Catholic Church of St. Catherine in St. Petersburg. In 1938, when the

Poniatowski died of a stroke on 12 February 1798. Paul I sponsored a royal state funeral, and on 3 March he was buried at the Catholic Church of St. Catherine in St. Petersburg. In 1938, when the

Stanisław August Poniatowski has been called the Polish Enlightenment's most important patron of the arts. His cultural projects were attuned to his socio-political aims of overthrowing the myth of the Golden Freedoms and the traditional ideology of Sarmatism. His weekly " Thursday Dinners" were considered the most scintillating social functions in the Polish capital.

He founded Warsaw's National Theatre, Poland's first public theatre, and sponsored an associated Ballet schoolsballet school. He remodeled

Stanisław August Poniatowski has been called the Polish Enlightenment's most important patron of the arts. His cultural projects were attuned to his socio-political aims of overthrowing the myth of the Golden Freedoms and the traditional ideology of Sarmatism. His weekly " Thursday Dinners" were considered the most scintillating social functions in the Polish capital.

He founded Warsaw's National Theatre, Poland's first public theatre, and sponsored an associated Ballet schoolsballet school. He remodeled  He supported the development of the sciences, particularly

He supported the development of the sciences, particularly

King Stanisław Augustus remains a controversial figure. In Polish

King Stanisław Augustus remains a controversial figure. In Polish  When elected to the throne, he was seen by many as simply an "instrument for displacing the somnolent Saxons from the throne of Poland", yet as the British historian, Norman Davies notes, "''he turned out to be an ardent patriot, and a convinced reformer.''" Still, according to many, his reforms did not go far enough, leading to accusations that he was being overly cautious, even indecisive, a fault to which he himself admitted. His decision to rely on Russia has been often criticized. Poniatowski saw Russia as a "lesser evil" – willing to support the notional "independence" of a weak Poland within the Russian sphere of influence. However, in the event Russia imposed the Partitions of Poland rather than choose to support internal reform. He was accused by others of weakness and subservience, even of treason, especially in the years following the Second Partition. During the Kościuszko Uprising, there were rumours that Polish Jacobins had been planning a

When elected to the throne, he was seen by many as simply an "instrument for displacing the somnolent Saxons from the throne of Poland", yet as the British historian, Norman Davies notes, "''he turned out to be an ardent patriot, and a convinced reformer.''" Still, according to many, his reforms did not go far enough, leading to accusations that he was being overly cautious, even indecisive, a fault to which he himself admitted. His decision to rely on Russia has been often criticized. Poniatowski saw Russia as a "lesser evil" – willing to support the notional "independence" of a weak Poland within the Russian sphere of influence. However, in the event Russia imposed the Partitions of Poland rather than choose to support internal reform. He was accused by others of weakness and subservience, even of treason, especially in the years following the Second Partition. During the Kościuszko Uprising, there were rumours that Polish Jacobins had been planning a

Poniatowski has been the subject of numerous biographies and many works of art.

Poniatowski has been the subject of numerous biographies and many works of art.

A few historians believe that he later contracted a secret marriage with Elżbieta Szydłowska. However, according to

A few historians believe that he later contracted a secret marriage with Elżbieta Szydłowska. However, according to

p. 9

/ref> * : Order of Saint Andrew (1764)''Kawalerowie i statuty Orderu Orła Białego 1705–2008''. Zamek Królewski w Warszawie: 2008, p. 186.

website

on descendants of

''Stanisław August w Petersburgu'' (Stanisław August in Saint Petersburg), "Życie Literackie", No. 43, 1987, p. 1, 6.

(Official page of the Royal Łazienki Museum in Warsaw)

Poniatowski, in: The Historical Geography of the Ciołek clan AD 950–1950

Poniatowski's memoirs

Works by Stanisław August Poniatowski

in digital library Polona {{DEFAULTSORT:Poniatowski, Stanislaw August 1732 births 1798 deaths People from Kamenets District People from Brest Litovsk Voivodeship

Józef Poniatowski

Prince Józef Antoni Poniatowski (; 7 May 1763 – 19 October 1813) was a Polish general, minister of war and army chief, who became a Marshal of the French Empire during the Napoleonic Wars.

A nephew of king Stanislaus Augustus of Poland (), P ...

(1763–1813), son of Andrzej. He was a great-grandson of poet and courtier Jan Andrzej Morsztyn and through his great-grandmother, Catherine Gordon, lady-in-waiting

A lady-in-waiting or court lady is a female personal assistant at a court, attending on a royal woman or a high-ranking noblewoman. Historically, in Europe, a lady-in-waiting was often a noblewoman but of lower rank than the woman to whom ...

to Queen Marie Louise Gonzaga, he was related to the House of Stuart

The House of Stuart, originally spelt Stewart, was a royal house of Scotland, England, Ireland and later Great Britain. The family name comes from the office of High Steward of Scotland, which had been held by the family progenitor Walter ...

and thereby connected to the leading families of Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to th ...

, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' ( Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan ar ...

. The Poniatowski family had achieved high status among the Polish nobility (szlachta

The ''szlachta'' (Polish: endonym, Lithuanian: šlėkta) were the noble estate of the realm in the Kingdom of Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth who, as a class, had the dominating position in ...

) of the time.

He spent the first few years of his childhood in Gdańsk

Gdańsk ( , also ; ; csb, Gduńsk;Stefan Ramułt, ''Słownik języka pomorskiego, czyli kaszubskiego'', Kraków 1893, Gdańsk 2003, ISBN 83-87408-64-6. , Johann Georg Theodor Grässe, ''Orbis latinus oder Verzeichniss der lateinischen Benen ...

. He was temporarily kidnapped as a toddler, on the orders of Józef Potocki, Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

of Kiev

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

, as a reprisal for his father's support for King Augustus III and held for some months in Kamieniec-Podolski. He was returned to his parents in Gdańsk. Later he moved with his family to Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is official ...

. He was initially educated by his mother, then by private tutors, including Russian ambassador

This is a list of diplomatic missions of Russia. These missions are subordinate to the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The Russian Federation has one of the largest networks of embassies and consulates of any country. Russia has significant ...

Herman Karl von Keyserling. He had few friends in his teenage years and instead developed a fondness for books which continued throughout his life. He went on his first foreign trip in 1748, with elements of the Imperial Russian army

The Imperial Russian Army (russian: Ру́сская импера́торская а́рмия, Romanization of Russian, tr. ) was the armed land force of the Russian Empire, active from around 1721 to the Russian Revolution of 1917. In the earl ...

as it advanced into the Rhineland

The Rhineland (german: Rheinland; french: Rhénanie; nl, Rijnland; ksh, Rhingland; Latinised name: ''Rhenania'') is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly its middle section.

Term

Historically, the Rhineland ...

to aid Maria Theresia

Maria Theresa Walburga Amalia Christina (german: Maria Theresia; 13 May 1717 – 29 November 1780) was ruler of the Habsburg dominions from 1740 until her death in 1780, and the only woman to hold the position '' suo jure'' (in her own right) ...

's troops during the War of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession () was a European conflict that took place between 1740 and 1748. Fought primarily in Central Europe, the Austrian Netherlands, Italy, the Atlantic and Mediterranean, related conflicts included King George' ...

which ended with the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748). This enabled Poniatowski both to visit the city, also known as Aachen, and to venture into the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

. On his return journey he stopped in Dresden

Dresden (, ; Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; wen, label=Upper Sorbian, Drježdźany) is the capital city of the German state of Saxony and its second most populous city, after Leipzig. It is the 12th most populous city of Germany, the fourth ...

.

Political career

The following year Poniatowski was apprenticed to the office of Michał Fryderyk Czartoryski, the then Deputy Chancellor of Lithuania. In 1750, he travelled to

The following year Poniatowski was apprenticed to the office of Michał Fryderyk Czartoryski, the then Deputy Chancellor of Lithuania. In 1750, he travelled to Berlin

Berlin is Capital of Germany, the capital and largest city of Germany, both by area and List of cities in Germany by population, by population. Its more than 3.85 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European U ...

where he met a British diplomat, Charles Hanbury Williams, who became his mentor and friend. In 1751, Poniatowski was elected to the Treasury Tribunal in Radom

Radom is a city in east-central Poland, located approximately south of the capital, Warsaw. It is situated on the Mleczna River in the Masovian Voivodeship (since 1999), having previously been the seat of a separate Radom Voivodeship (1975–1 ...

, where he served as a commissioner. He spent most of January 1752 at the Austrian court in Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

. Later that year, after serving at the Radom Tribunal and meeting King Augustus III of Poland, he was elected deputy of the Sejm

The Sejm (English: , Polish: ), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland ( Polish: ''Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), is the lower house of the bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of ...

(Polish parliament). While there his father secured for him the title of Starosta

The starosta or starost ( Cyrillic: ''старост/а'', Latin: ''capitaneus'', german: link=no, Starost, Hauptmann) is a term of Slavic origin denoting a community elder whose role was to administer the assets of a clan or family estates. T ...

of Przemyśl

Przemyśl (; yi, פשעמישל, Pshemishl; uk, Перемишль, Peremyshl; german: Premissel) is a city in southeastern Poland with 58,721 inhabitants, as of December 2021. In 1999, it became part of the Subcarpathian Voivodeship; it was pr ...

. In March 1753, he travelled to Hungary and Vienna, where he again met with Williams. He returned to the Netherlands, where he met many key members of that country's political and economic sphere. By late August he had arrived in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. ...

, where he moved among the elites. In February 1754, he travelled on to Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

, where he spent some months. There, he was befriended by Charles Yorke, the future Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. T ...

of Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

. He returned to the Commonwealth later that year, however he eschewed the Sejm, as his parents wanted to keep him out of the political furore surrounding the Ostrogski family's land inheritance (see: fee tail

In English common law, fee tail or entail is a form of trust established by deed or settlement which restricts the sale or inheritance of an estate in real property and prevents the property from being sold, devised by will, or otherwise alien ...

– ''Ordynacja Ostrogska''). The following year he received the title of '' Stolnik'' of Lithuania.

Poniatowski owed his rise and influence to his family connections with the powerful Czartoryski family

The House of Czartoryski (feminine form: Czartoryska, plural: Czartoryscy; lt, Čartoriskiai) is a Polish princely family of Lithuanian- Ruthenian origin, also known as the Familia. The family, which derived their kin from the Gediminids dyna ...

and their political faction, known as the '' Familia'', with whom he had grown close. It was the ''Familia'' who sent him in 1755 to Saint Petersburg in the service of Williams, who had been nominated British ambassador to Russia.

In Saint Petersburg, Williams introduced Poniatowski to the 26-year-old Catherine Alexeievna, the future empress Catherine the Great. The two became lovers. Whatever his feelings for Catherine, it is likely Poniatowski also saw an opportunity to use the relationship for his own benefit, using her influence to bolster his career.

Poniatowski had to leave St. Petersburg in July 1756 due to court intrigue. Through the combined influence of Catherine, of Russian empress Elizabeth and of chancellor

In Saint Petersburg, Williams introduced Poniatowski to the 26-year-old Catherine Alexeievna, the future empress Catherine the Great. The two became lovers. Whatever his feelings for Catherine, it is likely Poniatowski also saw an opportunity to use the relationship for his own benefit, using her influence to bolster his career.

Poniatowski had to leave St. Petersburg in July 1756 due to court intrigue. Through the combined influence of Catherine, of Russian empress Elizabeth and of chancellor Bestuzhev-Ryumin Bestuzhev-Ryumin (russian: Бестужев-Рюмин) is a Russian masculine surname, its feminine counterpart is Bestuzheva-Ryumina. It may refer to

* Alexey Bestuzhev-Ryumin (1693–1768), Grand Chancellor of Russia, son of Pyotr

* Konstantin Be ...

, Poniatowski was able to rejoin the Russian court now as ambassador of Saxony

Saxony (german: Sachsen ; Upper Saxon: ''Saggsn''; hsb, Sakska), officially the Free State of Saxony (german: Freistaat Sachsen, links=no ; Upper Saxon: ''Freischdaad Saggsn''; hsb, Swobodny stat Sakska, links=no), is a landlocked state of ...

the following January. Still in St Petersburg, he appears to have been a source of intrigue between various European governments, some supporting his appointment, others demanding his withdrawal. He eventually left the Russian capital on 14 August 1758.

Poniatowski attended the Sejms of 1758, 1760 and 1762. He continued his involvement with the ''Familia'', and supported a pro-Russian and anti-Prussian stance in Polish politics. His father died in 1762, leaving him a modest inheritance. In 1762, when Catherine ascended the Russian throne, she sent him several letters professing her support for his own ascension to the Polish throne, but asking him to stay away from St. Petersburg. Nevertheless, Poniatowski hoped that Catherine would consider his offer of marriage, an idea seen as plausible by some international observers. He participated in the failed plot by the ''Familia'' to stage a coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, ...

against King Augustus III. In August 1763, however, Catherine advised him and the ''Familia'' that she would not support a coup as long as King Augustus was alive.

Kingship

Years of hope

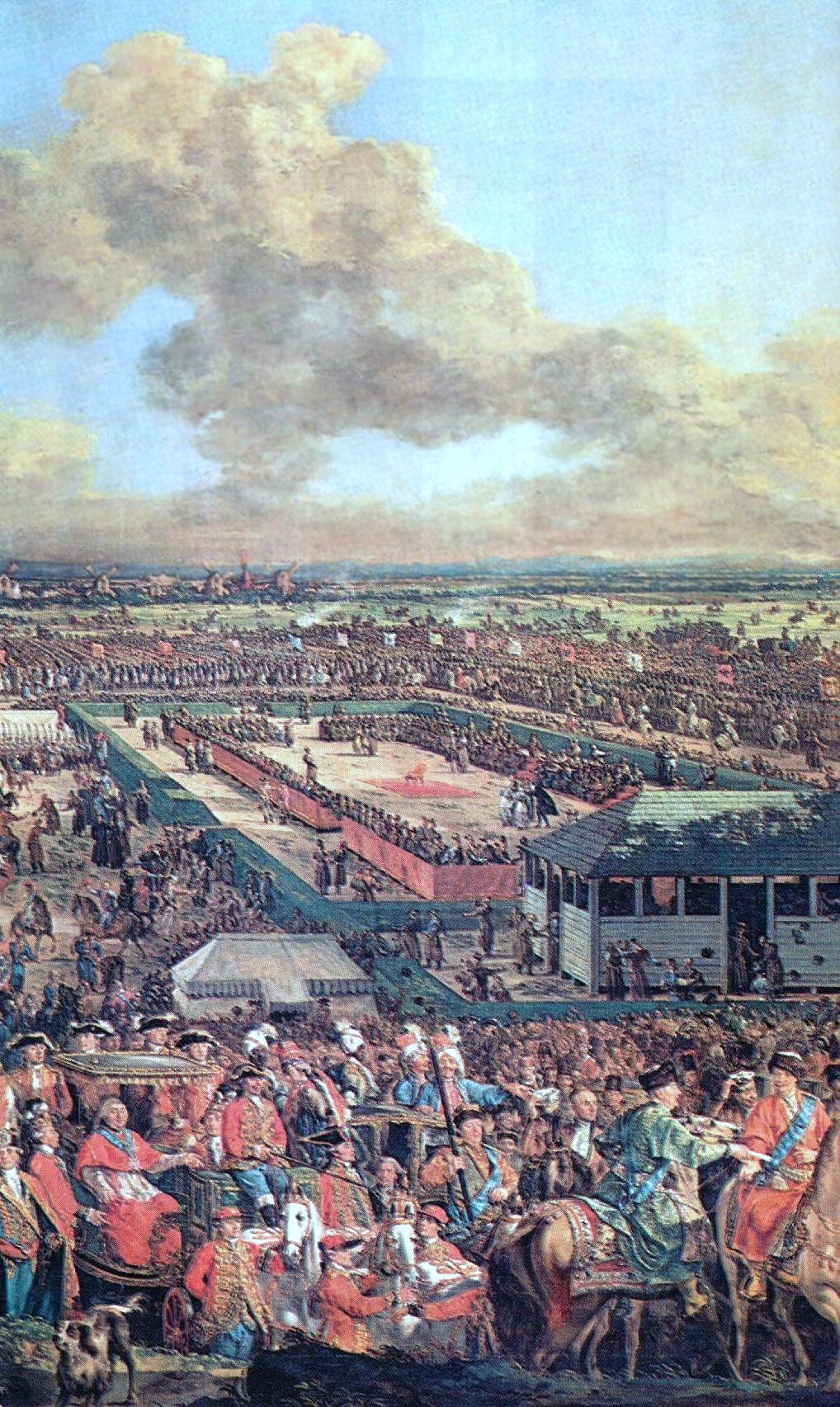

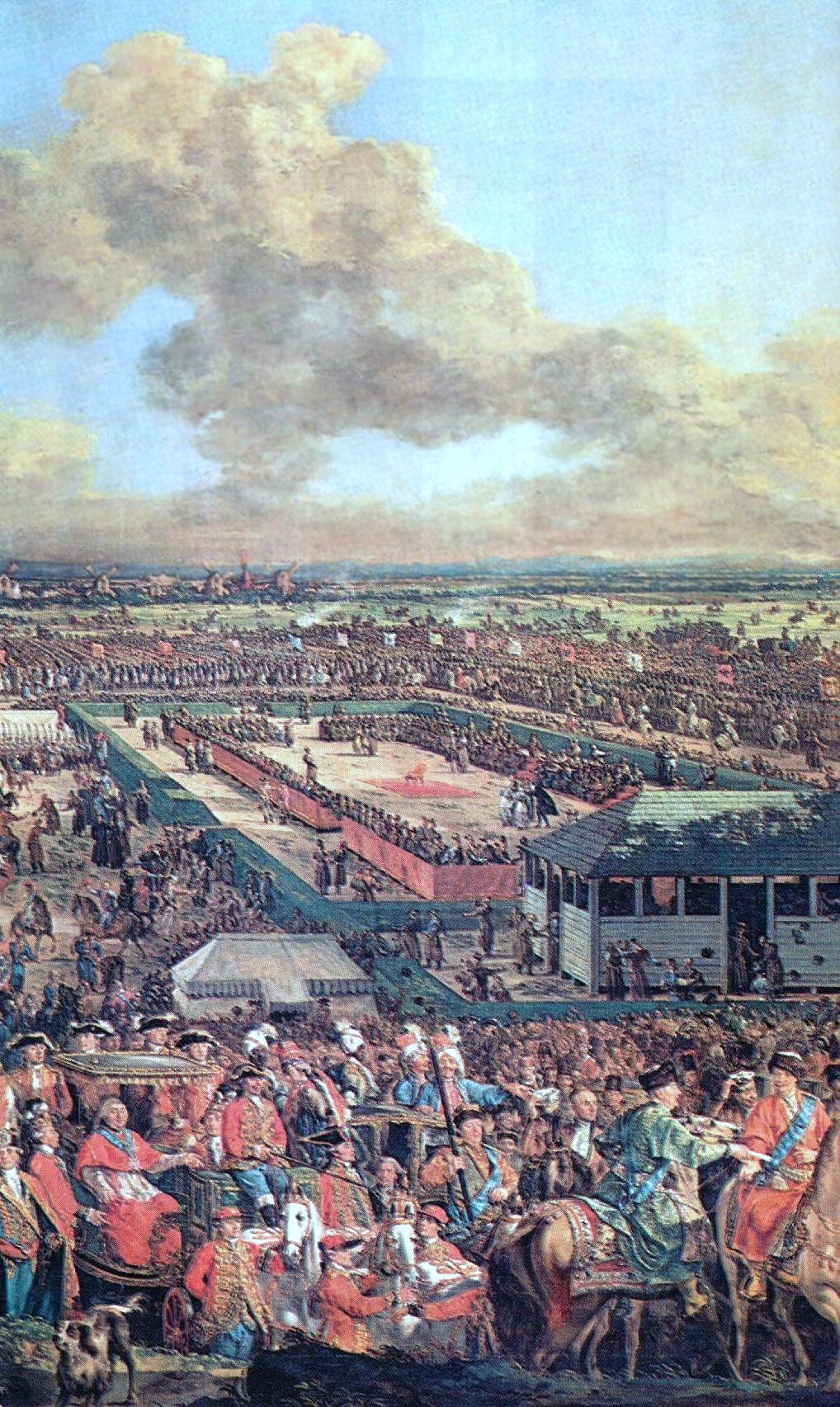

Upon the death of Poland's King Augustus III in October 1763, lobbying began for the election of the new king. Catherine threw her support behind Poniatowski. The Russians spent about 2.5m rubles in aid of his election. Poniatowski's supporters and opponents engaged in some military posturing and even minor clashes. In the end, the Russian army was deployed only a few kilometres from the election sejm, which met at

Upon the death of Poland's King Augustus III in October 1763, lobbying began for the election of the new king. Catherine threw her support behind Poniatowski. The Russians spent about 2.5m rubles in aid of his election. Poniatowski's supporters and opponents engaged in some military posturing and even minor clashes. In the end, the Russian army was deployed only a few kilometres from the election sejm, which met at Wola

Wola (, ) is a district in western Warsaw, Poland, formerly the village of Wielka Wola, incorporated into Warsaw in 1916. An industrial area with traditions reaching back to the early 19th century, it underwent a transformation into an office (co ...

near Warsaw. In the event, there were no other serious contenders, and during the convocation sejm on 7 September 1764, 32-year-old Poniatowski was elected king, with 5,584 votes. He swore the pacta conventa on 13 November, and a formal coronation took place in Warsaw on 25 November. The new king's "uncles" in the ''Familia'' would have preferred another nephew on the throne, Prince Adam Kazimierz Czartoryski, characterized by one of his contemporaries as "''débauché, si non dévoyé''" (French: "debauched if not depraved"), but Czartoryski had declined to seek office.

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

. On 7 May 1765, Poniatowski established the Order of the Knights of Saint Stanislaus, in honour of Saint Stanislaus of Krakow

In religious belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and denomination. In Catholic, Eastern O ...

, Bishop and Martyr, Poland's and his own patron saint, as the country's second order of chivalry, to reward Poles and others for noteworthy service to the King. Together with the ''Familia'' he tried to reform the ineffective system of government, by reducing the powers of the hetmans (Commonwealth's top military commanders) and treasurers, moving them to commissions elected by the Sejm and accountable to the King. In his memoirs, Poniatowski called this period the "years of hope." The ''Familia'', which was interested in strengthening its own power base, was dissatisfied with his conciliatory attitude as he reached out to many former opponents of their policies. This uneasy alliance between Poniatowski and the ''Familia'' continued for most of the first decade of his rule. One of the points of contention between Poniatowski and the ''Familia'' concerned the rights of religious minorities in Poland. Whereas Poniatowski reluctantly supported a policy of religious tolerance, the ''Familia'' was opposed to it. The growing rift between Poniatowski and the ''Familia'' was exploited by the Russians, who used the issue as a pretext to intervene in the Commonwealth's internal politics and to destabilize the country. Catherine had no wish to see Poniatowski's reform succeed. She had supported his ascent to the throne to ensure the Commonwealth remained a virtual puppet state

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside power and subject to its orders.Compare: Puppet states have nominal sover ...

under Russian control, so his attempts to reform the Commonwealth's ailing government structures were a threat to the ''status quo''.

The Bar Confederation and First Partition of Poland

Matters came to a head in 1766. During the Sejm in October of that year, Poniatowski attempted to push through a radical reform, restricting the disastrous '' liberum veto'' provision. He was opposed by conservatives such as Michał Wielhorski, who were supported by the Prussian and Russian ambassadors and who threatened war if the reform was passed. The dissidents, supported by the Russians, formed the Radom Confederation. Abandoned by the ''Familia'', Poniatowski's reforms failed to pass at the Repnin Sejm, named after Russian ambassadorNicholas Repnin

Prince Nikolai Vasilyevich Repnin (russian: Никола́й Васи́льевич Репни́н; – ) was an Imperial Russian statesman and general from the Repnin princely family who played a key role in the dissolution of the Polish–Lit ...

, who promised to guarantee with all the might of the Russian Empire the Golden Liberties of the Polish nobility, enshrined in the Cardinal Laws The Cardinal Laws ( pl, Prawa kardynalne) were a quasi-constitution enacted in Warsaw, Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, by the Repnin Sejm of 1767–68. Enshrining most of the conservative laws responsible for the inefficient functioning of the Com ...

.

Although it had abandoned the cause of Poniatowski's reforms, the ''Familia'' did not receive the support it expected from the Russians who continued to press for the conservatives' rights. Meanwhile, other factions now rallied under the banner of the Bar Confederation

The Bar Confederation ( pl, Konfederacja barska; 1768–1772) was an association of Polish nobles ( szlachta) formed at the fortress of Bar in Podolia (now part of Ukraine) in 1768 to defend the internal and external independence of the Polis ...

, aimed against the conservatives, Poniatowski and the Russians. After an unsuccessful attempt to raise allies in Western Europe, France, Britain and Austria, Poniatowski and the ''Familia'' had no choice but to rely more heavily on the Russian Empire, which treated Poland as a protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over most of its inte ...

. In the War of the Bar Confederation

The Bar Confederation ( pl, Konfederacja barska; 1768–1772) was an association of Polish nobles (szlachta) formed at the fortress of Bar in Podolia (now part of Ukraine) in 1768 to defend the internal and external independence of the Polish� ...

(1768–1772), Poniatowski supported the Russian army's repression of the Bar Confederation. In 1770, the Council of the Bar Confederation proclaimed him dethroned. The following year, he was kidnapped by Bar Confederates and was briefly held prisoner outside of Warsaw, but he managed to escape. In view of the continuing weakness of the Polish-Lithuanian state, Austria, Russia, and Prussia collaborated to threaten military intervention in exchange for substantial territorial concessions from the Commonwealth – a decision they made without consulting Poniatowski or any other Polish parties.

Although Poniatowski protested against the First Partition of the Commonwealth (1772), he was powerless to do anything about it. He considered

Although Poniatowski protested against the First Partition of the Commonwealth (1772), he was powerless to do anything about it. He considered abdication

Abdication is the act of formally relinquishing monarchical authority. Abdications have played various roles in the succession procedures of monarchies. While some cultures have viewed abdication as an extreme abandonment of duty, in other societ ...

, but decided against it.

During the Partition Sejm of 1773–1775, in which Russia was represented by ambassador Otto von Stackelberg, with no allied assistance forthcoming from abroad and with the armies of the partitioning powers occupying Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is official ...

to compel the Sejm by force of arms, no alternative was available save submission to their will. Eventually Poniatowski and the Sejm acceded to the "partition treaty". At the same time, several other reforms were passed. The Cardinal Laws The Cardinal Laws ( pl, Prawa kardynalne) were a quasi-constitution enacted in Warsaw, Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, by the Repnin Sejm of 1767–68. Enshrining most of the conservative laws responsible for the inefficient functioning of the Com ...

were confirmed and guaranteed by the partitioning powers. Royal prerogative was restricted, so that the King lost the power to confer titular roles, and military promotions, to appoint ministers and senators. Starostwo territories, and Crown land

Crown land (sometimes spelled crownland), also known as royal domain, is a territorial area belonging to the monarch, who personifies the Crown. It is the equivalent of an entailed estate and passes with the monarchy, being inseparable from it ...

s would be awarded by auction. The Sejm also created two notable institutions: the Permanent Council, a government body in continuous operation, and the Commission of National Education. The partitioning powers intended the council to be easier to control than the unruly Sejms, and indeed it remained under the influence of the Russian Empire. Nevertheless, it was a significant improvement on the earlier Commonwealth governance. The new legislation was guaranteed by the Russian Empire, giving it licence to interfere in Commonwealth politics when legislation it favoured was threatened.

The aftermath of the Partition Sejm saw the rise of a conservative faction opposed to the Permanent Council, seeing it as a threat to their Golden Freedoms. This faction was supported by the Czartoryski family, but not by Poniatowski, who proved to be quite adept at making the Council follow his wishes. This marked the formation of new anti-royal and pro-royal factions in Polish politics. The royal faction was made up primarily of people indebted to the King, who planned to build their careers on service to him. Few were privy to his plans for reforms, which were kept hidden from the conservative opposition and Russia. Poniatowski scored a political victory during the Sejm of 1776, which further strengthened the council. Chancellor Andrzej Zamoyski was tasked with the codification of the Polish law, a project that became known as the Zamoyski Code. Russia supported some, but not all, of the 1776 reforms, and to prevent Poniatowski from growing too powerful, it supported the opposition during the Sejm of 1778. This marked the end of Poniatowski's reforms, as he found himself without sufficient support to carry them through.

The Great Sejm and the Constitution of 3 May 1791

In the 1780s, Catherine appeared to favour Poniatowski marginally over the opposition, but she did not support any of his plans for significant reform. Despite repeated attempts, Poniatowski failed to confederate the sejms, which would have made them immune to the ''liberum veto''. Thus, although he had a majority in the Sejms, Poniatowski was unable to pass even the smallest reform. The Zamoyski Code was rejected by the Sejm of 1780, and opposition attacks on the King dominated the Sejms of 1782 and 1786. Reforms became possible again in the late 1780s. In the context of the wars being waged against the Ottoman Empire by both the

Reforms became possible again in the late 1780s. In the context of the wars being waged against the Ottoman Empire by both the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central- Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence ...

and the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the List of Russian monarchs, Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended th ...

, Poniatowski tried to draw Poland into the Austro-Russian alliance, seeing a war with the Ottomans as an opportunity to strengthen the Commonwealth. Catherine gave permission for the next Sejm to be called, as she considered some form of limited military alliance with Poland against the Ottomans might be useful.

The Polish-Russian alliance was not implemented, as in the end the only acceptable compromise proved unattractive to both sides. However, in the ensuing Four-Year Sejm of 1788–92 (known as the Great Sejm

The Great Sejm, also known as the Four-Year Sejm ( Polish: ''Sejm Wielki'' or ''Sejm Czteroletni''; Lithuanian: ''Didysis seimas'' or ''Ketverių metų seimas'') was a Sejm (parliament) of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that was held in Wars ...

), Poniatowski threw his lot in with the reformers associated with the Patriotic Party of Stanisław Małachowski

Count Stanisław Małachowski, of the Nałęcz coat-of-arms (; 1736–1809) was the first Prime Minister of Poland, a member of the Polish government's Permanent Council (Rada Nieustająca) (1776–1780), Marshal of the Crown Courts of Justice fr ...

, Ignacy Potocki and Hugo Kołłątaj

Hugo Stumberg Kołłątaj, also spelled ''Kołłątay'' (pronounced , 1 April 1750 – 28 February 1812), was a prominent Polish constitutional reformer and educationalist, and one of the most prominent figures of the Polish Enlightenment. He s ...

, and co-authored the Constitution of 3 May 1791. The Constitution introduced sweeping reforms. According to Jacek Jędruch, the Constitution, despite its liberal provisions, "fell somewhere below the French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

, above the Canadian

Canadians (french: Canadiens) are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of ...

, and left the General State Laws for the Prussian States (in German: ''Allgemeines Landrecht für die Preußischen Staaten'') far behind", but was "no match for the American Constitution".

George Sanford notes that the Constitution gave Poland "a constitutional monarchy close to the British model of the time." According to a contemporary account, Poniatowski himself described it, as "founded principally on those of England and the United States of America, but avoiding the faults and errors of both, and adapted as much as possible to the local and particular circumstances of the country." The Constitution of 3 May remained to the end a work in progress. A new civil

Civil may refer to:

*Civic virtue, or civility

*Civil action, or lawsuit

* Civil affairs

*Civil and political rights

*Civil disobedience

*Civil engineering

*Civil (journalism), a platform for independent journalism

*Civilian, someone not a membe ...

and criminal code

A criminal code (or penal code) is a document that compiles all, or a significant amount of a particular jurisdiction's criminal law. Typically a criminal code will contain offences that are recognised in the jurisdiction, penalties that migh ...

(provisionally called the "Stanisław Augustus Code") was among the proposals. Poniatowski also planned a reform to improve the situation of Polish Jews

The history of the Jews in Poland dates back at least 1,000 years. For centuries, Poland was home to the largest and most significant Ashkenazi Jewish community in the world. Poland was a principal center of Jewish culture, because of the lon ...

.

In foreign policy, spurned by Russia, Poland turned to another potential ally, the Triple Alliance Triple Alliance may refer to:

* Aztec Triple Alliance (1428–1521), Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan and in central Mexico

* Triple Alliance (1596), England, France, and the Dutch Republic to counter Spain

* Triple Alliance (1668), England, the ...

, represented on the Polish diplomatic scene primarily by the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) constituted the German state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918. Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Rev. ed. Oxford: ...

, which led to the formation of the ultimately futile Polish–Prussian alliance. The pro-Prussian shift was not supported by Poniatowski, who nevertheless acceded to the decision of the majority of Sejm deputies. The passing of the Constitution of 3 May, although officially applauded by Frederick William II of Prussia

Frederick William II (german: Friedrich Wilhelm II.; 25 September 1744 – 16 November 1797) was King of Prussia from 1786 until his death in 1797. He was in personal union the Prince-elector of Brandenburg and (via the Orange-Nassau inherita ...

, who sent a congratulatory note to Warsaw, caused further worry in Prussia. The contacts of Polish reformers with the revolutionary French National Assembly were seen by Poland's neighbours as evidence of a conspiracy and a threat to their absolute monarchies. Prussian statesman Ewald von Hertzberg expressed the fears of European conservatives: "The Poles have given the ''coup de grâce'' to the Prussian monarchy by voting in a constitution", elaborating that a strong Commonwealth would likely demand the return of the lands Prussia acquired in the First Partition; a similar sentiment was later expressed by Prussian Foreign Minister, Count Friedrich Wilhelm von der Schulenburg-Kehnert. Russia's wars with the Ottomans and Sweden having ended, Catherine was furious over the adoption of the Constitution, which threatened Russian influence in Poland. One of Russia's chief foreign policy authors, Alexander Bezborodko, upon learning of the Constitution, commented that "the worst possible news have arrived from Warsaw: the Polish king has become almost sovereign."

War in Defence of the Constitution and fall of the Commonwealth

Shortly thereafter, conservative Polish nobility formed the

Shortly thereafter, conservative Polish nobility formed the Targowica Confederation

The Targowica Confederation ( pl, konfederacja targowicka, , lt, Targovicos konfederacija) was a confederation established by Polish and Lithuanian magnates on 27 April 1792, in Saint Petersburg, with the backing of the Russian Empress Catheri ...

to overthrow the Constitution, which they saw as a threat to the traditional freedoms and privileges they enjoyed. The confederates aligned themselves with Russia's Catherine the Great, and the Russian army entered Poland, marking the start of the Polish–Russian War of 1792

The Polish–Russian War of 1792 (also, War of the Second Partition, and in Polish sources, War in Defence of the Constitution ) was fought between the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth on one side, and the Targowica Confederation (conserva ...

, also known as the War in Defence of the Constitution. The Sejm voted to increase the Polish Army to 100,000 men, but due to insufficient time and funds this number was never achieved. Poniatowski and the reformers could field only a 37,000-man army, many of them untested recruits. This army, under the command of the King's nephew Józef Poniatowski

Prince Józef Antoni Poniatowski (; 7 May 1763 – 19 October 1813) was a Polish general, minister of war and army chief, who became a Marshal of the French Empire during the Napoleonic Wars.

A nephew of king Stanislaus Augustus of Poland (), P ...

and Tadeusz Kościuszko

Andrzej Tadeusz Bonawentura Kościuszko ( be, Andréj Tadévuš Banavientúra Kasciúška, en, Andrew Thaddeus Bonaventure Kosciuszko; 4 or 12 February 174615 October 1817) was a Polish military engineer, statesman, and military leader who ...

, managed to defeat the Russians or fight them to a draw on several occasions. Following the victorious Battle of Zieleńce, in which Polish forces were commanded by his nephew, the King founded a new order, the Order of Virtuti Militari, to reward Poles for exceptional military leadership and courage in combat.

Despite Polish requests, Prussia refused to honour its alliance obligations. In the end, the numerical superiority of the Russians was too great, and defeat looked inevitable. Poniatowski's attempts at negotiations with Russia proved futile. In July 1792, when Warsaw was threatened with siege by the Russians, the king came to believe that surrender was the only alternative to total defeat. Having received assurances from Russian ambassador Yakov Bulgakov that no territorial changes would occur, a cabinet of ministers called the Guard of Laws

Guardians of the Laws or Guard of Laws ( pl, Straż Praw) was a short-lived supreme executive governing body of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth established by the Constitution of May 3, 1791. It was abolished, together with other reforms of ...

(or Guardians of Law, pl, Straż Praw) voted eight to four in favor of surrender. On 24 July 1792, Poniatowski joined the Targowica Confederation. The Polish Army disintegrated. Many reform leaders, believing their cause lost, went into self-exile, although they hoped that Poniatowski would be able to negotiate an acceptable compromise with the Russians, as he had done in the past. Poniatowski had not saved the Commonwealth, however. He and the reformers had lost much of their influence, both within the country and with Catherine. Neither were the Targowica Confederates victorious. To their surprise, there ensued the Second Partition of Poland

The 1793 Second Partition of Poland was the second of three partitions (or partial annexations) that ended the existence of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth by 1795. The second partition occurred in the aftermath of the Polish–Russian ...

. With the new deputies bribed or intimidated by the Russian troops, the Grodno Sejm

Grodno Sejm ( pl, Sejm grodzieński; be, Гарадзенскі сойм; lt, Gardino seimas) was the last Sejm (session of parliament) of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. The Grodno Sejm, held in autumn 1793 in Grodno, Grand Duchy of Li ...

took place. On 23 November 1793, it annulled all acts of the Great Sejm, including the Constitution. Faced with his powerlessness, Poniatowski once again considered abdication; in the meantime he tried to salvage whatever reforms he could.

Final years

Poniatowski's plans had been ruined by the Kościuszko Uprising. The King had not encouraged it, but once it began he supported it, seeing no other honourable option. Its defeat marked the end of the Commonwealth. Poniatowski tried to govern the country in the brief period after the fall of the Uprising, but on 2 December 1794, Catherine demanded he leave Warsaw, a request to which he acceded on 7 January 1795, leaving the capital under Russian military escort and settling briefly in

Poniatowski's plans had been ruined by the Kościuszko Uprising. The King had not encouraged it, but once it began he supported it, seeing no other honourable option. Its defeat marked the end of the Commonwealth. Poniatowski tried to govern the country in the brief period after the fall of the Uprising, but on 2 December 1794, Catherine demanded he leave Warsaw, a request to which he acceded on 7 January 1795, leaving the capital under Russian military escort and settling briefly in Grodno

Grodno (russian: Гродно, pl, Grodno; lt, Gardinas) or Hrodna ( be, Гродна ), is a city in western Belarus. The city is located on the Neman River, 300 km (186 mi) from Minsk, about 15 km (9 mi) from the Polish ...

. On 24 October 1795, the Act of the final, Third Partition of Poland

The Third Partition of Poland (1795) was the last in a series of the Partitions of Poland–Lithuania and the land of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth among Prussia, the Habsburg monarchy, and the Russian Empire which effectively ended Poli ...

was signed. One month and one day later, on 25 November, Poniatowski signed his abdication.

Reportedly, his sister, Ludwika Maria Zamoyska and her daughter also his favourite niece, Urszula Zamoyska, who had been threatened with confiscation of their property, had contributed to persuading him to sign the abdication: they feared that his refusal would lead to a Russian confiscation of their properties and their ruin.

Catherine died on 17 November 1796, succeeded by her son, Paul I of Russia

Paul I (russian: Па́вел I Петро́вич ; – ) was Emperor of Russia from 1796 until his assassination. Officially, he was the only son of Peter III and Catherine the Great, although Catherine hinted that he was fathered by her l ...

. On 15 February 1797, Poniatowski left for Saint Petersburg. He had hoped to be allowed to travel abroad, but was unable to secure permission to do so. A virtual prisoner in St. Petersburg's Marble Palace, he subsisted on a pension granted to him by Catherine. Despite financial troubles, he still supported some of his former allies, and continued to try to represent the Polish cause at the Russian court. He also worked on his memoirs.

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

planned to demolish the Church, his remains were transferred to the Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 1918 and 1939. The state was established on 6 November 1918, before the end of the First World ...

and interred in a church at Wołczyn, his birthplace. This was done in secret and caused controversy in Poland when the matter became known. In 1990, due to the poor state of the Wołczyn church (then in the Byelorussian SSR

The Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (BSSR, or Byelorussian SSR; be, Беларуская Савецкая Сацыялістычная Рэспубліка, Bielaruskaja Savieckaja Sacyjalistyčnaja Respublika; russian: Белор� ...

), his body was once more exhumed and was brought to Poland, to St. John's Cathedral in Warsaw, where on 3 May 1791 he had celebrated the adoption of the Constitution that he had coauthored. A third funeral ceremony was held on 14 February 1995.

Legacy

Patron of culture

Stanisław August Poniatowski has been called the Polish Enlightenment's most important patron of the arts. His cultural projects were attuned to his socio-political aims of overthrowing the myth of the Golden Freedoms and the traditional ideology of Sarmatism. His weekly " Thursday Dinners" were considered the most scintillating social functions in the Polish capital.

He founded Warsaw's National Theatre, Poland's first public theatre, and sponsored an associated Ballet schoolsballet school. He remodeled

Stanisław August Poniatowski has been called the Polish Enlightenment's most important patron of the arts. His cultural projects were attuned to his socio-political aims of overthrowing the myth of the Golden Freedoms and the traditional ideology of Sarmatism. His weekly " Thursday Dinners" were considered the most scintillating social functions in the Polish capital.

He founded Warsaw's National Theatre, Poland's first public theatre, and sponsored an associated Ballet schoolsballet school. He remodeled Ujazdów Palace Ujazdów may refer to the following places in Poland:

*Ujazdów, Warsaw, a neighbourhood in Śródmieście, Warsaw

**Ujazdów Avenue in Warsaw

**Ujazdów Castle in Warsaw

**Ujazdów Park in Warsaw

*Ujazdów, Włodawa County in Lublin Voivodeship (e ...

and the Royal Castle in Warsaw, and erected the elegant Łazienki (Royal Baths) Palace in Warsaw's Łazienki, Park. He involved himself deeply in the detail of his architectural projects, and his eclectic style has been dubbed the "Stanisław August style" by Polish art historian Władysław Tatarkiewicz

Władysław Tatarkiewicz (; 3 April 1886, Warsaw – 4 April 1980, Warsaw) was a Polish philosopher, historian of philosophy, historian of art, esthetician, and ethicist.

Early life and education

Tatarkiewicz began his higher education a ...

. His chief architects included Domenico Merlini and Jan Kammsetzer.

He was also patron to numerous painters. They included Poles such as his protégée, Anna Rajecka

Anna Rajecka (c.1762, Warsaw – 1832, Paris), was a Polish portrait painter and pastellist. She was also known as Madame Gault de Saint-Germain.

Biography

She was born to a portrait painter named Józef Rajecki and raised as a protégée of kin ...

and Franciszek Smuglewicz, Jan Bogumił Plersch, son of Jan Jerzy Plersch

Jan Jerzy Plersch also Johann Georg Plersch (1704 or 1705 – 1 January 1774) was a Polish sculptor of German origin.

The design of Plersch's sculptures refers to some extent to the so-called "School of Lviv" in sculpture. A symbolic tombsto ...

, Józef Wall, and Zygmunt Vogel, as well as foreign painters including, Marcello Bacciarelli, Bernardo Bellotto, Jean Pillement

Jean-Baptiste Pillement (Lyon, 24 May 1728 – Lyon, 26 April 1808) was a French painter and designer, known for his exquisite and delicate landscapes, but whose importance lies primarily in the engravings done after his drawings, and their infl ...

, Ludwik Marteau

Ludwik Marteau, originally Louis-François Marteau (c.1715 - 2 November 1804) was a Polish court painter who served under kings Augustus III of Poland, Augustus III and Stanisław August Poniatowski. All of his known works are portraits; both full ...

, and Per Krafft the Elder. His retinue of sculptors, headed by André-Jean Lebrun

André-Jean Lebrun (1737–1811) was a French sculptor.

Life

André-Jean Lebrun was born in Paris in 1737. He studied under Jean-Baptiste Pigalle.

Lebrun won the Grand Prix of the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture in 1756.

He tied wi ...

, included Giacomo Monaldi, Franz Pinck, and Tommaso Righi. Jan Filip Holzhaeusser was his court engraver and the designer of many commemorative medals. According to a 1795 inventory, Stanisław August's art collection, spread among numerous buildings, contained 2,889 pieces, including works by Rembrandt

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (, ; 15 July 1606 – 4 October 1669), usually simply known as Rembrandt, was a Dutch Golden Age painter, printmaker and draughtsman. An innovative and prolific master in three media, he is generally co ...

, Rubens, and van Dyck

Sir Anthony van Dyck (, many variant spellings; 22 March 1599 – 9 December 1641) was a Brabantian Flemish Baroque artist who became the leading court painter in England after success in the Southern Netherlands and Italy.

The seventh ...

. His plan to create a large gallery of paintings in Warsaw was disrupted by the dismemberment of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Most of the paintings that he had ordered for it can now be seen in London's Dulwich Picture Gallery. Poniatowski also planned to found an Academy of Fine Arts, but this finally came about only after his abdication and departure from Warsaw.

Poniatowski accomplished much in the realm of education and literature. He established the School of Chivalry, also called the "Cadet Corps", which functioned from 1765 to 1794 and whose alumni included Tadeusz Kościuszko

Andrzej Tadeusz Bonawentura Kościuszko ( be, Andréj Tadévuš Banavientúra Kasciúška, en, Andrew Thaddeus Bonaventure Kosciuszko; 4 or 12 February 174615 October 1817) was a Polish military engineer, statesman, and military leader who ...

. He supported the creation of the Commission of National Education, considered to be the world's first Ministry of Education. In 1765 he helped found the '' Monitor'', one of the first Polish newspapers and the leading periodical of the Polish Enlightenment. He sponsored many articles that appeared in the ''Monitor''. Writers and poets who received his patronage included, Stanisław Trembecki, Franciszek Salezy Jezierski Franciszek Salezy Jezierski (1740–1791) was a Polish writer, social and political activist of the Enlightenment period. A Catholic priest, he was involved with the creation of the Commission of National Education. Member of the Hugo Kołłątaj

...

, Franciszek Bohomolec and Franciszek Zabłocki. He also supported publishers including, Piotr Świtkowski, and library owners such as Józef Lex.

He supported the development of the sciences, particularly

He supported the development of the sciences, particularly cartography

Cartography (; from grc, χάρτης , "papyrus, sheet of paper, map"; and , "write") is the study and practice of making and using maps. Combining science, aesthetics and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality (or an ...

; he hired a personal cartographer, Karol de Perthees, even before he was elected king. A plan he initiated to map the entire territory of the Commonwealth, however, was never finished. At the Royal Castle in Warsaw, he organized an astronomical observatory

An observatory is a location used for observing terrestrial, marine, or celestial events. Astronomy, climatology/meteorology, geophysical, oceanography and volcanology are examples of disciplines for which observatories have been constructed. H ...

and supported astronomers Jan Śniadecki and Marcin Odlanicki Poczobutt. He also sponsored historical studies, including the collection, cataloging and copying of historical manuscripts. He encouraged publications of biographies of famous Polish historical figures, and sponsored paintings and sculptures of them.

For his contributions to the arts and sciences, Poniatowski was awarded in 1766 a royal Fellowship of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the judges of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural knowledge, including mathemati ...

, where he became the first royal Fellow outside British royalty. In 1778 he was awarded fellowship of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences

The Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS; russian: Росси́йская акаде́мия нау́к (РАН) ''Rossíyskaya akadémiya naúk'') consists of the national academy of Russia; a network of scientific research institutes from across t ...

, and in 1791 of the Berlin Academy of Sciences.

He also supported the development of industry and manufacturing, areas in which the Commonwealth lagged behind most of Western Europe. Among the endeavours in which he invested were the manufacture of cannons and firearms and the mining industry.

Poniatowski himself left several literary works: his memoirs, some political brochures and recorded speeches from the Sejm. He was considered a great orator and a skilled conversationalist.

Conflicting assessments

King Stanisław Augustus remains a controversial figure. In Polish

King Stanisław Augustus remains a controversial figure. In Polish historiography

Historiography is the study of the methods of historians in developing history as an academic discipline, and by extension is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiography of a specific topic covers how historians hav ...

and in popular works, he has been criticized or marginalized by authors such as, Szymon Askenazy, Joachim Lelewel, Jerzy Łojek whom Andrzej Zahorski describes as Poniatowski's most vocal critic among modern historians, Tadeusz Korzon, Karol Zyszewski and Krystyna Zienkowska; whereas more neutral or positive views have been expressed by Paweł Jasienica, Walerian Kalinka, Władysław Konopczyński, Stanisław Mackiewicz

Stanisław "Cat" Mackiewicz (18 December 1896 in Saint Petersburg, Russia – 18 February 1966 in Warsaw, Poland) was a conservative Polish writer, journalist and monarchist.

Interwar journalist Adolf Maria Bocheński called him the foremost p ...

, Emanuel Rostworowski and Stanisław Wasylewski.

coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, ...

and Poniatowski's assassination. Another line of criticism alleged poor financial management on his part. Poniatowski actually had little personal wealth. Most of his income came from Crown Estate

The Crown Estate is a collection of lands and holdings in the United Kingdom belonging to the British monarch as a corporation sole, making it "the sovereign's public estate", which is neither government property nor part of the monarch's priv ...

s and monopolies. His lavish patronage of the arts and sciences was a major drain on the royal treasury. He also supported numerous public initiatives, and attempted to use the royal treasury to cover the state's expenses when tax revenues were insufficient. The Sejm promised several times to compensate his treasury to little practical effect. Nonetheless contemporary critics frequently accused him of being a spendthrift.

Andrzej Zahorski dedicated a book to a discussion of Poniatowski, ''The Dispute over Stanisław August'' (''Spór o Stanisława Augusta'', Warsaw, 1988). He notes that the discourse concerning Poniatowski is significantly coloured by the fact that he was the last King of Poland – the King who failed to save the country. This failure, and his prominent position, rendered him a convenient scapegoat for many. Zahorski argues that Poniatowski made the error of joining the Targowica Confederation. Although he wanted to preserve the integrity of the Polish state, it was far too late for that – he succeeded instead in cementing the damage to his own reputation for succeeding centuries.

Remembrance

Poniatowski has been the subject of numerous biographies and many works of art.

Poniatowski has been the subject of numerous biographies and many works of art. Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his '' nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his criticism of Christianity—es ...

, who saw Poniatowski as a model reformist, based his character, King Teucer in the play ''Les Lois de Minos'' (1772) on Poniatowski. At least 58 contemporary poems were dedicated to him or praised him. Since then, he has been a major character in many works of Józef Ignacy Kraszewski, in the ''Rok 1794'' trilogy by Władysław Stanisław Reymont, in the novels of Tadeusz Łopalewski

Tadeusz Łopalewski (August 17, 1900 in Ostrowce, near Kutno – March 29, 1979) was a Polish poet, prose writer, dramatist and translator of Russian literature

Russian literature refers to the literature of Russia and its émigrés and ...

, and in the dramas of Ignacy Grabowski, Tadeusz Miciński

Tadeusz Miciński (9 November 1873, in Łódź – February 1918, in Cherykaw Raion, Belarus) was an influential Polish poet, gnostic and playwright, and was a forerunner of Expressionism and Surrealism. He is one of the writers of the Young Po ...

, Roman Brandstaetter

Roman Brandstaetter (January 3, 1906 – September 28, 1987) was a Polish writer, poet, playwright, journalist and translator.

Life and career

Early life: 1906 –1940

Roman Brandstaetter was born in Tarnów, to a religious Jewish family, being t ...

and Bogdan Śmigielski. He is discussed in Luise Mühlbach's novel ''Joseph II and His Court'', and appears in Jane Porter's 1803 novel, '' Thaddeus of Warsaw''.

On screen he has been played by Wieńczysław Gliński in the 1976 ''3 Maja'' directed by Grzegorz Królikiewicz. He appears in a Russian TV series.

Poniatowski is depicted in numerous portraits, medals and coins. He is prominent in Jan Matejko

Jan Alojzy Matejko (; also known as Jan Mateyko; 24 June 1838 – 1 November 1893) was a Polish painter, a leading 19th-century exponent of history painting, known for depicting nodal events from Polish history. His works include large scale oil ...

's work, especially in the 1891 painting, '' Constitution of 3 May 1791'' and in another large canvas, '' Rejtan'', and in his series of portraits of Polish monarchs. A bust of Poniatowski was unveiled in Łazienki Palace in 1992. A number of cities in Poland have streets named after him, including Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 159 ...

and Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is official ...

.

Family

Poniatowski never married. In his youth, he had loved his cousin Elżbieta Czartoryska, but her father August Aleksander Czartoryski disapproved because he did not think him influential or rich enough. When this was no longer an issue, she was already married. His '' pacta conventa'' specified that he should marry a Polish noblewoman, although he himself always hoped to marry into someroyal family

A royal family is the immediate family of kings/queens, emirs/emiras, sultans/ sultanas, or raja/ rani and sometimes their extended family. The term imperial family appropriately describes the family of an emperor or empress, and the term p ...

.

Upon his accession to the throne, he had hopes of marrying Catherine II

, en, Catherine Alexeievna Romanova, link=yes

, house =

, father = Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst

, mother = Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp

, birth_date =

, birth_name = Princess Sophie of Anha ...

, writing to her on 2 November 1763 in a moment of doubt, "If I desired the throne, it was because I saw you on it." When she made it clear through his envoy Rzewuski that she would not marry him, there were hopes of an Austrian archduchess, Archduchess Maria Elisabeth of Austria (1743–1808). A marriage to Princess Sophia Albertina of Sweden was suggested despite the religious differences, but this match was opposed by his sisters, Ludwika Maria Poniatowska and Izabella Poniatowska, and nothing came of it. The ceremonial role of queen and hostess of his court was played by his favourite niece, Urszula Zamoyska.

A few historians believe that he later contracted a secret marriage with Elżbieta Szydłowska. However, according to

A few historians believe that he later contracted a secret marriage with Elżbieta Szydłowska. However, according to Wirydianna Fiszerowa

Wirydianna Fiszerowa (born Wirydianna Radolińska, using the Leszczyc coat of arms, later Wirydianna Kwilecka) (1761 in Wyszyny - 1826 in Działyń) was a Polish noblewoman best known for her memoirs, which mention her life in pre- and post-pa ...

, a contemporary who knew them both, this rumour only spread after the death of Poniatowski, was generally disbelieved, and moreover, was circulated by Elżbieta herself, so the marriage is considered by most to be unlikely.

He had several notable lovers, including Elżbieta Branicka

Elżbieta Branicka (c. 1734 – 3 September 1800) was a Polish noblewoman (''szlachcianka'') and politician. She is known for her political career, being the financier of the King Stanisław August Poniatowski prior to his election as king, his a ...

, who acted as his political adviser and financier, and had children with two of them. With Magdalena Agnieszka Sapieżyna

Magdalena Agnieszka Sapieżyna (1739-1780), was a Polish aristocrat. She was known as the mistress of King Stanisław August Poniatowski and had a child with him, Michał Cichocki, in 1770.

Life

She was born as daughter of Prince Antoni Benedykt L ...

(1739–1780), he became the father of Konstancja Żwanowa (1768–1810) and Michał Cichocki (1770–1828). With Elżbieta Szydłowska (1748–1810), he became the father of Stanisław Konopnicy-Grabowski (1780–1845), Michał Grabowski (1773–1812), Kazimierz Grabowski (1770-?), Konstancja Grabowska and Izabela Grabowska (1776–1858).

Issue

Titles, honours and arms

The English translation of the Polish text of the 1791 Constitution gives his title as ''Stanisław August, by the grace of God and the will of the people, King ofPoland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, , is a country in Central Europe. Poland is divided into Voivodeships of Poland, sixteen voivodeships and is the fifth most populous member state of the European Union (EU), with over 38 mill ...

, Grand Duke of Lithuania and Duke of Ruthenia, Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

, Masovia

Mazovia or Masovia ( pl, Mazowsze) is a historical region in mid-north-eastern Poland. It spans the North European Plain, roughly between Łódź and Białystok, with Warsaw being the unofficial capital and largest city. Throughout the centuri ...

, Samogitia

Samogitia or Žemaitija ( Samogitian: ''Žemaitėjė''; see below for alternative and historical names) is one of the five cultural regions of Lithuania and formerly one of the two core administrative divisions of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

, Kiev

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

, Volhynia