St Peter's Collegiate Church is located in central

Wolverhampton

Wolverhampton () is a city, metropolitan borough and administrative centre in the West Midlands, England. The population size has increased by 5.7%, from around 249,500 in 2011 to 263,700 in 2021. People from the city are called "Wulfrunian ...

,

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

. For many centuries it was a

chapel royal

The Chapel Royal is an establishment in the Royal Household serving the spiritual needs of the sovereign and the British Royal Family. Historically it was a body of priests and singers that travelled with the monarch. The term is now also applie ...

and from 1480 a

royal peculiar

A royal peculiar is a Church of England parish or church exempt from the jurisdiction of the diocese and the province in which it lies, and subject to the direct jurisdiction of the monarch, or in Cornwall by the duke.

Definition

The church par ...

, independent of the

Diocese of Lichfield and even the

Province of Canterbury

The Province of Canterbury, or less formally the Southern Province, is one of two ecclesiastical provinces which constitute the Church of England. The other is the Province of York (which consists of 12 dioceses).

Overview

The Province consist ...

. The

collegiate church was central to the development of the town of Wolverhampton, much of which belonged to its dean. Until the 18th century, it was the only church in Wolverhampton and the control of the college extended far into the surrounding area, with dependent chapels in several towns and villages of southern

Staffordshire

Staffordshire (; postal abbreviation Staffs.) is a landlocked county in the West Midlands region of England. It borders Cheshire to the northwest, Derbyshire and Leicestershire to the east, Warwickshire to the southeast, the West Midlands Cou ...

.

Fully integrated into the diocesan structure since 1848, today St Peter's is part of the

Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

Parish of Central Wolverhampton. The Grade I

listed building

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern Irel ...

, much of which is

Perpendicular

In elementary geometry, two geometric objects are perpendicular if they intersect at a right angle (90 degrees or π/2 radians). The condition of perpendicularity may be represented graphically using the ''perpendicular symbol'', ⟂. It can ...

in style, dating from the 15th century, is of significant architectural and historical interest. Although it is not a

cathedral

A cathedral is a church that contains the '' cathedra'' () of a bishop, thus serving as the central church of a diocese, conference, or episcopate. Churches with the function of "cathedral" are usually specific to those Christian denomination ...

, it has a strong choral foundation in keeping with English Cathedral tradition. The

Father Willis

Henry Willis (27 April 1821 – 11 February 1901), also known as "Father" Willis, was an English organ player and builder, who is regarded as the foremost organ builder of the Victorian era. His company Henry Willis & Sons remains in busin ...

organ is of particular note: a campaign to raise £300,000 for its restoration was launched in 2008. Restoration began in 2018.

History

St Peter's is an

Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons were a Cultural identity, cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo- ...

foundation. The history of St Peter's was dominated for centuries by its

collegiate status, from the 12th century constituted as a

dean and

prebendaries, and by its royal connections, which were crystallised in the form of the

Royal Peculiar

A royal peculiar is a Church of England parish or church exempt from the jurisdiction of the diocese and the province in which it lies, and subject to the direct jurisdiction of the monarch, or in Cornwall by the duke.

Definition

The church par ...

in 1480. Although a source of pride and prosperity to both town and church, this institutional framework, hard-won and doggedly defended, made the church subject to the whims of the monarch or governing elite and unresponsive to the needs of its people. Characterised by absenteeism and corruption through most of its history, the college was involved in constant political and legal strife, and it was dissolved and restored a total of three times, before a fourth and final dissolution in 1846-8 cleared the way for St Peter's to become an active urban

parish

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest, often termed a parish priest, who might be assisted by one or m ...

church and the focus of civic pride.

994–1066: Origins and endowments

Wulfrun's charter

There is some doubt about the origins of the

College

A college (Latin: ''collegium'') is an educational institution or a constituent part of one. A college may be a degree-awarding tertiary educational institution, a part of a collegiate or federal university, an institution offering ...

of Wolverhampton. The most important item of evidence is a

charter

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified. It is implicit that the granter retains superiority (or sovereignty), and that the rec ...

, alleged by an anonymous history of the

Diocese of Lichfield to have been discovered around 1560 ''in ruderibus muri'', "in the ruins of a wall." The story of its discovery and its subsequent disappearance has cast doubt on the authenticity of the charter. It is known from a transcription made by

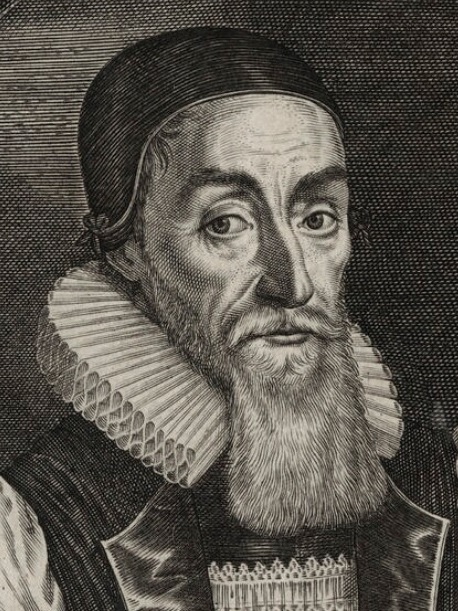

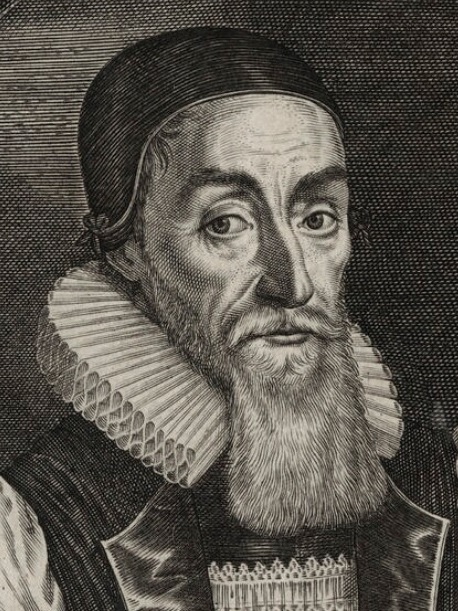

William Dugdale

Sir William Dugdale (12 September 1605 – 10 February 1686) was an English antiquary and herald. As a scholar he was influential in the development of medieval history as an academic subject.

Life

Dugdale was born at Shustoke, near Coleshi ...

in 1640, when the original was in the library at

St. George's Chapel, Windsor Castle, and included in his famous survey, ''Monasticon Anglicanum''.

Sigeric, Archbishop of Canterbury, confirms Lady

Wulfrun

__NOTOC__

Wulfrun(a) (-) was an Anglo-Saxon (early English) noble woman of Mercia and a landowner who held estates in Staffordshire.

Today she is particularly remembered for her association with ''Hēatūn'', Anglo-Saxon for "high or principal ...

's endowment of a Minster at Hampton. The original grant by Wulfrun, partly Latin and partly

Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, Anglo ...

, is quoted in the charter. A translation begins:

:''I, Wulfrun, do grant to the proper patron and high-throned King of Kings, and (in honour of) the everlasting Virgin mother of God, Mary, and of all the saints, for the body of my husband, and of my soul, ten hides of land, to that aforesaid monastery of the servants of God there, and in another convenient place another ten hides for the offences of Wulfgeat my kinsman lest he should hear in the judgment to be dreaded from the severe Judge, "Go away from me, I hungered and thirsted," and so on. Because he is blessed who shall eat bread in the kingdom of God. Finally now my sole daughter, Elfthryth, has migrated from the world to the life-giving airs. For the third time I have granted 10 hides to the almighty God, with ineffable charity, more willingly than the others (Which are surrounded by these territories). These are the boundaries of the land that Wulfrun has given to the minster in Hamtun and the names of the towns that this privilegium refers to:

:First of

Earn-leie and

Eswick and

Bilsetna-tun and

Willan-hale and

Wodnesfeld and

Peoleshale and

Ocgingtun and

Hiltun and

Hagenthorndun and Kynwaldes-tun (Kinvaston) and another Hiltune and

Feotherstun.''

The charter then defines the boundaries of the estates given by Wulfrun in considerable detail. Some of the places named are fairly easy to recognise from their modern or medieval forms: Arley, Bilston, Willenhall, Wednesfield, Pelsall, Ogley Hay, Hilton, Hatherton, Kinvaston, Featherstone. Others raise problems. These were discussed in the notes to a collection of Anglo-Saxon charters prepared for publication by C. G. O. Bridgeman in 1916, and his conclusions have been generally accepted. These include the identification of ''Eswick'' as

Ashwood, Staffordshire

Ashwood is a small area of Staffordshire, England.

It is situated in the South Staffordshire district, approximately two miles west of the West Midlands conurbation and the Metropolitan Borough of Dudley. Population details for the 2011 census ...

, as it was ''Haswic'' in the

Domesday Book

Domesday Book () – the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book" – is a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 by order of King William I, known as William the Conqueror. The manusc ...

, and of the second Hilton as a village of that name near Ogley and

Wall, Staffordshire

Wall is a small village and civil parish in Staffordshire, England, just south of Lichfield. It lies on the site of the Roman settlement of Letocetum.

The parish includes the small villages of Pipehill, Hilton and Chesterfield, and the tiny ham ...

. The ten

hides of land at Wolverhampton were probably those which Wulfrun herself had received from

Ethelred II by a charter of 985. These were specified as ''ix uidelicet in loco qui dicitur aet Heantune, et aeque unam manentem in eo loco quae Anglice aet Treselcotum uocitatur'' ("nine plainly in the place which is called Hampton and equally the remaining one in the place called by the English Trescott"): the latter is a place on the

River Smestow to the west of Wolverhampton. The Arley lands probably came from a grant which King

Edgar the Peaceful had made to Wulfgeat, a relative of Wulfrun, in 963. In 1548, before the alleged discovery of Wulfrun's charter, Edgar himselfwas generally accepted as the founder of the College. Wulfgeat was an important adviser to Ethelred, a king who proverbially, as the Unready or ''Redeless'', did not accept good advice: he fell into disgrace and Wulfrun's grants were partly to make amends for his perceived injustices. When Wulfgeat died in about 1006, he left four

oxen

An ox ( : oxen, ), also known as a bullock (in BrE

British English (BrE, en-GB, or BE) is, according to Oxford Dictionaries, "English as used in Great Britain, as distinct from that used elsewhere". More narrowly, it can refer spec ...

to the church at ''Heantune''.

Heantun church

The church was originally dedicated to

St Mary

Mary; arc, ܡܪܝܡ, translit=Mariam; ar, مريم, translit=Maryam; grc, Μαρία, translit=María; la, Maria; cop, Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ, translit=Maria was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Joseph and the mother of ...

and this was still the dedication at the

Domesday

Domesday Book () – the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book" – is a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 by order of King William I, known as William the Conqueror. The manusc ...

survey:

[ It was switched to ]St Peter

) (Simeon, Simon)

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Bethsaida, Gaulanitis, Syria, Roman Empire

, death_date = Between AD 64–68

, death_place = probably Vatican Hill, Rome, Italia, Roman Empire

, parents = John (or Jonah; Jona)

, occupation ...

, probably in the mid-12th century: an escheator's inquisition in 1393 recalled that it was still St Mary's when Henry I Henry I may refer to:

876–1366

* Henry I the Fowler, King of Germany (876–936)

* Henry I, Duke of Bavaria (died 955)

* Henry I of Austria, Margrave of Austria (died 1018)

* Henry I of France (1008–1060)

* Henry I the Long, Margrave of the No ...

(1100–35) granted a small estate to set up a chantry for himself and his parents.[Calendar of Inquisitions Miscellaneous, 1392–1399, p. 20, no. 44.]

/ref> It seems likely that the College always consisted of secular clergy

In Christianity, the term secular clergy refers to deacons and priests who are not monastics or otherwise members of religious life. A secular priest (sometimes known as a diocesan priest) is a priest who commits themselves to a certain geogra ...

—priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in particu ...

s who did not belong to a religious order

A religious order is a lineage of communities and organizations of people who live in some way set apart from society in accordance with their specific religious devotion, usually characterized by the principles of its founder's religious practi ...

, rather than monk

A monk (, from el, μοναχός, ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a person who practices religious asceticism by monastic living, either alone or with any number of other monks. A monk may be a person who decides to dedica ...

s. A writ

In common law, a writ (Anglo-Saxon ''gewrit'', Latin ''breve'') is a formal written order issued by a body with administrative or judicial jurisdiction; in modern usage, this body is generally a court. Warrants, prerogative writs, subpoenas, a ...

attributed to King Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor ; la, Eduardus Confessor , ; ( 1003 – 5 January 1066) was one of the last Anglo-Saxon English kings. Usually considered the last king of the House of Wessex, he ruled from 1042 to 1066.

Edward was the son of Æth ...

(1042–1066) refers to the College as "my priests at Hampton." Although the document is known to be a forgery, probably dating from a century later, the secular character of the chapter seems to have been accepted unchallenged, despite the implication in the foundation charter that it might be a monastery. All of the Domesday entries relating to the church of Wolverhampton refer to clergy

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

, canons or priests, never monks. There is no evidence that a monastery ever existed at Wolverhampton.

A college was not originally an educational institution but rather a body of people with a shared purpose, in this case a community of priests charged with pastoral care

Pastoral care is an ancient model of emotional, social and spiritual support that can be found in all cultures and traditions.

The term is considered inclusive of distinctly non-religious forms of support, as well as support for people from rel ...

over a wide and wild area. Wulfruna's was far from unique, even in its locality. The collegiate church of St Michael at nearby Penkridge

Penkridge ( ) is a village and civil parishes in England, civil parish in South Staffordshire, South Staffordshire District in Staffordshire, England. It is to the south of Stafford, north of Wolverhampton, west of Cannock and east of Telford. ...

pre-dated Wulfruna's church, probably by about half a century. Frank Stenton pointed out that Old English word ''mynster'' was often used as a word for churches served by such communities of priests and does not necessarily indicate that a community was made up of monks, although it is derived from the Latin ''monasterium''. Rather than conventional parishes, substantial areas in Anglo-Saxon England were served by groups of priests who replicated the bishop's cathedral chapter in which they had been trained by working in community. These were generally not monastic houses in the full sense. Ethelred II did decree clerical celibacy

Clerical celibacy is the requirement in certain religions that some or all members of the clergy be unmarried. Clerical celibacy also requires abstention from deliberately indulging in sexual thoughts and behavior outside of marriage, because the ...

for such bodies, in an effort them more monastic in character, but without success. Richard A. Fletcher noted that in this period of renewed Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

activity there were numerous "communities of clergy at which reformers looked askance but which very probably made a significant if unobtrusive contribution to the Christianization of Anglo-Scandinavian England." In some cases, like that of Ripon Cathedral, former monasteries were revived as collegiate churches. At least one, Stow Minster

The Minster Church of St Mary, Stow in Lindsey, is a major Anglo-Saxon church in Lincolnshire and is one of the largest and oldest parish church buildings in England. It has been claimed that the Minster originally served as the cathedral church ...

in Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (abbreviated Lincs.) is a county in the East Midlands of England, with a long coastline on the North Sea to the east. It borders Norfolk to the south-east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south-west, Leicestershire ...

, benefited greatly from the generosity of another Mercian noblewoman, Godgifu or Lady Godiva

Lady Godiva (; died between 1066 and 1086), in Old English , was a late Anglo-Saxon noblewoman who is relatively well documented as the wife of Leofric, Earl of Mercia, and a patron of various churches and monasteries. Today, she is mainly reme ...

. Wulfrun's foundation belonged firmly in this wave of lay foundations. By Domesday Wolverhampton and Penkridge had been joined by St Mary's Church, Stafford

St Mary's Church, Stafford is a Grade I listed parish church in Stafford, Staffordshire, England.

History

The church dates from the early 13th century, with 14th century transepts and 15th century clerestories and crossing tower.

Excavations i ...

and St Michael's at Tettenhall.

1066–1135: Norman conquest and its consequences

It is not clear when the College began to have a close connection with the Crown, although this was to become a defining characteristic, which shaped much of its history. The forged letter of Edward the Confessor is meant to point to just such a close relationship, but we know it dates from a century later, after the church had Wolverhampton had passed through a series of difficulties which it probably wanted to resolve permanently. Some of these stemmed from the Norman Conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Conque ...

, which brought considerable disruption to Staffordshire's collegiate churches. Wolverhampton's was given by William the Conqueror

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first House of Normandy, Norman List of English monarchs#House of Norman ...

to his own personal chaplain, Samson.

The following table summarises information in the Domesday Book relating to locations that were or had been holdings of the canons of Wolverhampton. The information is derived from the relevant facsimile page at Open Domesday and the translation at the University of Hull

The University of Hull is a public research university in Kingston upon Hull, a city in the East Riding of Yorkshire, England. It was founded in 1927 as University College Hull. The main university campus is located in Hull and is home to the Hull ...

's Hydra Repository.

Domesday shows a variable situation of retreat and advance for the canons of Wolverhampton. They no longer held Wolverhampton itself as tenants-in-chief but as tenants of Samson.[ No holdings of the canons are mentioned at Bilston, either before of after the Conquest: the whole of Bilston now belonged to the king himself. Other lands he had let out to other priests: certainly Hatherton, although the ]Victoria County History

The Victoria History of the Counties of England, commonly known as the Victoria County History or the VCH, is an English history project which began in 1899 with the aim of creating an encyclopaedic history of each of the historic counties of En ...

includes, while Open Domesday does not, Kinvaston, Hilton and Featherstone. At Arley, some of their land had been seized forcibly by one Osbern Fitz Richard. On the other hand, even before the Conquest, they had acquired an estate at Lutley, Worcestershire, and they claimed woodland at Sedgeley: neither of these was in Wulfrun's grant.

At Wolverhampton, the canons' land was cultivated by 14 slaves, alongside 36 other peasants. Samson was elected Bishop of Worcester on 8 June 1096. He may have been previously in only minor orders, as he had to be ordained a priest the day before his consecration. He became notorious, despite his vow of clerical celibacy, as the father of at least three children, two of whom later became bishops. During the reign of

Samson was elected Bishop of Worcester on 8 June 1096. He may have been previously in only minor orders, as he had to be ordained a priest the day before his consecration. He became notorious, despite his vow of clerical celibacy, as the father of at least three children, two of whom later became bishops. During the reign of Henry I Henry I may refer to:

876–1366

* Henry I the Fowler, King of Germany (876–936)

* Henry I, Duke of Bavaria (died 955)

* Henry I of Austria, Margrave of Austria (died 1018)

* Henry I of France (1008–1060)

* Henry I the Long, Margrave of the No ...

, he donated the church at Wolverhampton to his cathedral priory

A priory is a monastery of men or women under religious vows that is headed by a prior or prioress. Priories may be houses of mendicant friars or nuns (such as the Dominicans, Augustinians, Franciscans, and Carmelites), or monasteries of mon ...

at Worcester, although its lands and privileges were protected. Henry I himself made a very substantial grant to Wolverhampton church to establish his chantry there: a house with forty acre

The acre is a unit of land area used in the imperial

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imp ...

s of land and rents worth £20 a year.[

]

1135–89: Anarchy and after

However,

However, The Anarchy

The Anarchy was a civil war in England and Normandy between 1138 and 1153, which resulted in a widespread breakdown in law and order. The conflict was a war of succession precipitated by the accidental death of William Adelin, the only legiti ...

, the confused civil strife of King Stephen's reign, brought great challenges. First the church was seized by Roger, Bishop of Salisbury

Roger of Salisbury (died 1139), was a Norman medieval bishop of Salisbury and the seventh Lord Chancellor and Lord Keeper of England.

Life

Roger was originally priest of a small chapel near Caen in Normandy. He was called "Roger, priest of the c ...

. Roger had risen to be Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. The ...

and Henry I's chief minister and had vowed to support the succession of the Empress Matilda

Empress Matilda ( 7 February 110210 September 1167), also known as the Empress Maude, was one of the claimants to the English throne during the civil war known as the Anarchy. The daughter of King Henry I of England, she moved to Germany as ...

, Henry I's daughter and chosen heir. He broke his word on Henry's death, citing her marriage to Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou

Geoffrey V (24 August 1113 – 7 September 1151), called the Handsome, the Fair (french: link=no, le Bel) or Plantagenet, was the count of Anjou, Count of Tours, Touraine and Count of Maine, Maine by inheritance from 1129, and also Duke of Nor ...

, as justification. His support was initially crucial in allowing Stephen to consolidate his rule after his coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

of 1135, and he used his influence to extend his property, building a powerful political clique that included his nephews, Nigel, Bishop of Ely and Alexander, Bishop of Lincoln. Stephen felt threatened by his over-mighty Chancellor and moved against him on 24 October 1139. Provoked into a brawl at the king's court at Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, Roger and his family were disgraced and dispossessed. He lost the church at Wolverhampton and its lands, along with much else, and died in December. At Oxford, in 1139 or 1140, Stephen granted Wolverhampton church to Roger de Clinton, described as Bishop of Chester

The Bishop of Chester is the Ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Chester in the Province of York.

The diocese extends across most of the historic county boundaries of Cheshire, including the Wirral Peninsula and has its see in the C ...

and Lichfield Cathedral

Lichfield Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in Lichfield, Staffordshire, England, one of only three cathedrals in the United Kingdom with three spires (together with Truro Cathedral and St Mary's Cathedral in Edinburgh), and the only medie ...

. He also issued a writ of intendence, calling on all the clergy, laity and tenants to transfer their loyalty to Bishop Roger.

The canons were outraged at this betrayal of trust, which left them at the mercy of a powerful magnate in their own vicinity, and appealed to Pope Eugenius III

Pope Eugene III ( la, Eugenius III; c. 1080 – 8 July 1153), born Bernardo Pignatelli, or possibly Paganelli, called Bernardo da Pisa, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 15 February 1145 to his death in 1153. He w ...

. It is notable that around this time the dedication was changed to St Peter, which would be a flattering move in negotiations with Rome. Occasionally thereafter it was described as the Church of St Peter and St Paul

Paul; grc, Παῦλος, translit=Paulos; cop, ⲡⲁⲩⲗⲟⲥ; hbo, פאולוס השליח (previously called Saul of Tarsus;; ar, بولس الطرسوسي; grc, Σαῦλος Ταρσεύς, Saũlos Tarseús; tr, Tarsuslu Pavlus; ...

. Whatever dedication is given, the church's seals generally picture both saints. Despite the briefness of the interlude under Lichfield, the impact of Bishop Roger de Clinton and his chapter of secular clergy at Lichfield may have been considerable. The diocese had three centres: Coventry

Coventry ( or ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city in the West Midlands (county), West Midlands, England. It is on the River Sherbourne. Coventry has been a large settlement for centuries, although it was not founded and given its ...

, Chester

Chester is a cathedral city and the county town of Cheshire, England. It is located on the River Dee, close to the English–Welsh border. With a population of 79,645 in 2011,"2011 Census results: People and Population Profile: Chester Loca ...

and Lichfield

Lichfield () is a cathedral city and civil parish in Staffordshire, England. Lichfield is situated roughly south-east of the county town of Stafford, south-east of Rugeley, north-east of Walsall, north-west of Tamworth and south-west of B ...

. As the other centres were so heavily involved in the military action of Stephen's reign, it seems that Clinton gave renewed emphasis to the religious role of Lichfield, re-establishing it as the headquarters of his see. It seems that he reorganised Lichfield's chapter on a prebend

A prebendary is a member of the Roman Catholic or Anglican clergy, a form of canon with a role in the administration of a cathedral or collegiate church. When attending services, prebendaries sit in particular seats, usually at the back of the ...

al model in order to counterbalance the monastic chapter at Coventry and using Rouen Cathedral as his model. At some time in the mid-12th century, probably under the control of Lichfield, Wolverhampton was reorganised along similar lines, with a dean and prebendaries. King Stephen restored Wolverhampton church to Worcester priory by 1152, perhaps as early as 1144. In his concession, he described himself as ''prius inconsulte'' – previously ill-advised.

Stephen was forced to agree that he would be succeeded by Matilda's son,

Stephen was forced to agree that he would be succeeded by Matilda's son, Henry Plantagenet

Henry II (5 March 1133 – 6 July 1189), also known as Henry Curtmantle (french: link=no, Court-manteau), Henry FitzEmpress, or Henry Plantagenet, was King of England from 1154 until his death in 1189, and as such, was the first Angevin king ...

, at that time already Duke of Normandy

In the Middle Ages, the duke of Normandy was the ruler of the Duchy of Normandy in north-western Kingdom of France, France. The duchy arose out of a grant of land to the Viking leader Rollo by the French king Charles the Simple, Charles III in ...

and Duke of Aquitaine. Even before he succeeded to the throne, Henry issued a charter in which he described the church at Wolverhampton as "my chapel", restored all its privileges from the time of Henry I, and recognised it as free from secular taxation.

As soon as he came to the throne in 1154 as Henry II, he issued another charter recognising the right of the canons to hold a manorial court

The manorial courts were the lowest courts of law in England during the feudal period. They had a civil jurisdiction limited both in subject matter and geography. They dealt with matters over which the lord of the manor had jurisdiction, primarily ...

. Neither of these charters explicitly stated Wolverhampton was not subject to the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Lichfield, but the king had clearly asserted a special relationship with the Crown, recognising the church at Wolverhampton as a royal chapel. It was probably Henry II who appointed Peter of Blois

Peter of Blois ( la, Petrus Blesensis; French: ''Pierre de Blois''; ) was a French cleric, theologian, poet and diplomat. He is particularly noted for his corpus of Latin letters.

Early life and education

Peter of Blois was born about 1130. Ear ...

as Dean of Wolverhampton: he is the first dean whose name is known. Peter was a Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

poet, lawyer and a diplomat of considerable experience. He had been tutor to William II of Sicily

William II (December 115311 November 1189), called the Good, was king of Sicily from 1166 to 1189. From surviving sources William's character is indistinct. Lacking in military enterprise, secluded and pleasure-loving, he seldom emerged from his ...

, one of the most cultivated rulers of his time, and Henry had brought him into his circle of close supporters when he was under extreme pressure because of the murder of Thomas Becket

Thomas Becket (), also known as Saint Thomas of Canterbury, Thomas of London and later Thomas à Becket (21 December 1119 or 1120 – 29 December 1170), was an English nobleman who served as Lord Chancellor from 1155 to 1162, and then ...

and ruptures in the royal family.

1189–1224: Dissolution and restoration

By the time Peter of Blois was appointed, the College was organised as a community of prebendaries, headed by a dean. Peter seems to have taken little interest in his Wolverhampton deanery until after the death of Henry II: he had numerous other benefice

A benefice () or living is a reward received in exchange for services rendered and as a retainer for future services. The Roman Empire used the Latin term as a benefit to an individual from the Empire for services rendered. Its use was adopted by ...

s and was heavily involved in Archbishop Baldwin's prolonged feud with his own cathedral chapter, spending a year away, arguing Baldwin's case at the Papal Curia in 1187-88.[

The earliest extant evidence of any interest Wolverhampton is a letter he wrote to the ]Chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

, William Longchamp, to denounce the “tyranny of the Sheriff of Stafford” who was, he complained, trampling on the church's ancient privileges and oppressing the townspeople. The letter was well-calculated to win sympathy, as the sheriff was Hugh Nonant

Hugh Nonant (sometimes Hugh de Nonant; died 27 March 1198) was a medieval Bishop of Coventry in England. A great-nephew and nephew of two Bishops of Lisieux, he held the office of archdeacon in that diocese before serving successively Thomas Be ...

, Bishop of Coventry, an enemy of Longchamp because he supported the Prince John, the regent. It must have been written in 1190-1, as Longchamp's ascendancy dates from mid-1190 and he was forced to leave the country in October 1191. Although he championed the church against outsiders, Peter considered the prebendaries corrupt. He wrote a stinging rebuke to Robert of Shrewsbury who held one of the Wolverhampton prebends and sought to retain it after he was elected Bishop of Bangor.

Around 1202, Peter resigned his post and put forward a revolutionary plan from outside. In a letter to

Around 1202, Peter resigned his post and put forward a revolutionary plan from outside. In a letter to Pope Innocent III

Pope Innocent III ( la, Innocentius III; 1160 or 1161 – 16 July 1216), born Lotario dei Conti di Segni (anglicized as Lothar of Segni), was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1198 to his death in 16 J ...

, Peter denounced the college as composed of a clique, so closely and notoriously intermarried that no-one was able to prise them apart. As they were incorrigible, a complete reform was necessary. With the assent of the Archbishop of Canterbury and the king, a Cistercian

The Cistercians, () officially the Order of Cistercians ( la, (Sacer) Ordo Cisterciensis, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Saint ...

monastery could be established, as the area abounded in the woods, meadows and waters needed by this ascetic French order dedicated to a radical and literal interpretation of the Benedictine Rule. Peter did persuade Archbishop Hubert Walter

Hubert Walter ( – 13 July 1205) was an influential royal adviser in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries in the positions of Chief Justiciar of England, Archbishop of Canterbury, and Lord Chancellor. As chancellor, Walter b ...

and King John of the advantages of his plan and it received royal assent early in 1203. It appears that John had already appointed one Nicholas to the deanery, left vacant by Peter's resignation. This Nicholas appeared as Dean of Wolverhampton when he was taken to court in September 1203 by Elias Fitz Philip in a property case involving an estate at Kinvaston. Shortly afterwards, he appears in court again, shorn of his title, as plain Nicholas de Hamton, and later again under the same designation, when it is specified that the dispute is over one virgate of land. It appears that this marks his loss of the deanery, in line with the king's decision to wind up the college of Wolverhampton..

Early in 1204 John transferred the deanery and prebends to the archbishop in order for him to establish a monastery, which should pray for souls of the king and his ancestors after death, as well as in their lifetimes. He dispensed with Forest law and exactions for these properties. On 28 July 1204 John also granted the manor of Wolverhampton: his charter suggests that there were already Cistercian monks waiting there in readiness. On 31 May 1205 at Portchester

Portchester is a locality and suburb northwest of Portsmouth, England. It is part of the borough of Fareham in Hampshire. Once a small village, Portchester is now a busy part of the expanding conurbation between Portsmouth and Southampton o ...

John granted the vill of Tettenhall. These were additional to the deanery and prebends and represented a further level of security in possession of the estates: the Pipe rolls show that in 1203/4 Hubert Walter had already drawn an income of 20 shillings per quarter or £4 a year from Tettenhall, while in 1204/5 he received the same from Tettenhall (but in three instalments) and 33 shillings quarterly or £6 12s. for the year from Wolverhampton. On 1 June 1205, still at Portchester, John issued a charter transferring to Archbishop Hubert woodland at Kingsley in Kinver Forest

Kinver Forest was a Royal Forest, mainly in Staffordshire.

Extent

References to "forest" in Domesday Book suggest that the forest was of similar extent in 1086 and in the 14th century. Its precise extent in the intervening period can only be dedu ...

, which was close to Tettenhall, this time specifying that it was for the construction of a Cistercian monastery: once again, it was dispensed from Forest law and customs. John also had a full charter drafted, granting in perpetual alms "the deanery, prebends and whole manor of Wolverhampton, the wood of Kingsley and the vill of Tettenhall and all their parts."[''Rotuli Chartarum'', p. 154.]

/ref> The scheme also received the reforming Innocent III's approval, which was still in force when Archbishop Hubert Walter died on 13 July 1205.

Immediately everything was reversed. The draft charter of liberties was marked as cancelled because of archbishop's death.[ John had changed his mind completely and on 5 August 1205, only three weeks after the archbishop's death, he appointed a replacement dean of Wolverhampton: Henry, the son of his Chief Justiciar, ]Geoffrey Fitz Peter, 1st Earl of Essex

Geoffrey Fitz Peter, Earl of Essex (c. 1162–1213) was a prominent member of the government of England during the reigns of Richard I and John. The patronymic is sometimes rendered Fitz Piers, for he was the son of Piers de Lutegareshale (born ...

. Abandoning any pretence of reform, the terms of Henry's appointment specified that he was to hold the deanery with its liberties and honours exactly as his predecessors. Well-connected to all the centres of power in the kingdom, he seems to have held the post of dean for nearly two decades. It is often claimed that the new church was begun early in the 13th century, probably during the interregnum, meaning that it would have been constructed largely under Henry. However, the building's Historic England listing now suggests that the earliest part of the present building, the crossing and south transept

A transept (with two semitransepts) is a transverse part of any building, which lies across the main body of the building. In cruciform churches, a transept is an area set crosswise to the nave in a cruciform ("cross-shaped") building withi ...

, date from the late 13th century.

1224–1300: Disputes and prosperity

Giles de Erdington

Giles of Erdington, who became Dean of St Peter's around 1224, was a talented lawyer and was already set on a career that would make him one of Henry III's most eminent judges, a Justice of the Common Bench

The Court of Common Pleas, or Common Bench, was a common law court in the English legal system that covered "common pleas"; actions between subject and subject, which did not concern the king. Created in the late 12th to early 13th century afte ...

. He soon seized the opportunity afforded by the appointment of a new and inexperienced bishop, Alexander Stavensby

Alexander de Stavenby (or Alexander of Stainsby; died 26 December 1238) was a medieval Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield.

Alexander was probably a native of Stainsby, Lincolnshire, and had two brothers, William and Gilbert, who held land there. ...

, to make a formal deal with the Diocese of Lichfield. The dean's right to appoint and discipline the prebends was recognised. The bishop was to intervene only in the last resort, if the dean was not carrying out his functions. For his part, the dean recognised the bishop's right to be received with honour at St Peter's and to administer the sacraments

A sacrament is a Christian rite that is recognized as being particularly important and significant. There are various views on the existence and meaning of such rites. Many Christians consider the sacraments to be a visible symbol of the real ...

there. However the whole issue blew up again in 1260, when Erdington repelled an attempt by Bishop Roger de Meyland

Roger de Meyland (died 1295) was a medieval Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield, England.

Roger was a cousin of King Henry III of England, although the exact relationship is unclear.Moorman ''Church Life in England'' p. 159 Roger was born c. 1215, ...

to hold a canonical visitation

In the Catholic Church, a canonical visitation is the act of an ecclesiastical superior who in the discharge of his office visits persons or places with a view to maintaining faith and discipline and of correcting abuses. A person delegated to car ...

by getting a royal prohibition on 8 November "against any person attempting anything against the privileges of Giles de Erdinton, king's clerk

In the Kingdom of England, the title of Secretary of State came into being near the end of the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603), the usual title before that having been King's Clerk, King's Secretary, or Principal Secretary.

From the ...

, dean of Wolverhampton, or of the king's chapel of Wolverhampton, or of the canons or servitors there." The prohibition cited a Papal rescript

Papal rescripts are responses of the pope or a Congregation of the Roman Curia, in writing, to queries or petitions of individuals. Some rescripts concern the granting of favours; others the administration of justice under canon law, e. g. the i ...

, issued at Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the third-largest city and second-largest metropolitan area of France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of t ...

in 1245, that guaranteed the independence of royal chapels, which it characterised as ''ecclesiae Romanae immediate subjecta'', directly subordinate to the Roman Church. They were therefore immune even from excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

and interdict pronounced at a lower level, which disarmed the local bishop in his dealings with them.

Erdington was equally vigorous in promoting the economic interests of the college. Sometimes this meant taking a firm line over local issues: in 1230 he literally raised a stink by taking legal action against a chaplain at Tettenhall over marshland at Codsall

Codsall is a large village in the South Staffordshire district of Staffordshire, England. It is situated 4.5 miles northwest of the city of Wolverhampton and 13 miles east-southeast of Telford. It forms part of the boundary of the Staffordshire ...

that was creating a health hazard. Property agreements were carefully recorded, often by the device of a fine of lands

A fine of lands, also called a final concord, or simply a fine, was a species of property conveyance which existed in England (and later in Wales) from at least the 12th century until its abolition in 1833 by the Fines and Recoveries Act.

...

, a conveyance registered by a fictional lawsuit. On 18 November 1236, for example, he was notionally sued for land at Kinvaston by Athelard: the two sides came to an agreement that Athelard's family would rent 1½ virgates from the dean and his successors for ½ mark

Mark may refer to:

Currency

* Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark, the currency of Bosnia and Herzegovina

* East German mark, the currency of the German Democratic Republic

* Estonian mark, the currency of Estonia between 1918 and 1927

* Fi ...

annually. To make clear the college's territorial sway, he had the boundaries walked ceremonially. In 1248, for example, the king ordered the sheriff to organise a perambulation with twelve knights near Codsall where the College's lands bordered the Oaken

Oaken is a small village in Staffordshire, England. The first mention of the Oaken place-name was in 1086 when it was listed in the Domesday book as ''Ache''. Its origin appears to be from the Old English, ''ācum'' - (place of) the oaks.

Oaken ...

estate of Croxden Abbey

Croxden Abbey, also known as "Abbey of the Vale of St. Mary at Croxden", was a Cistercian abbey at Croxden, Staffordshire, United Kingdom. A daughter house of the abbey in Aunay-sur-Odon, Normandy, the abbey was founded by Bertram III de Verdun ...

. Sometimes it was necessary to pursue offenders. In June 1253 the Dean and Chapter prosecute 39 local men who had entered the College's lands as an armed band, destroying fences and crops. None turned up in court and their sureties

In finance, a surety , surety bond or guaranty involves a promise by one party to assume responsibility for the debt obligation of a borrower if that borrower defaults. Usually, a surety bond or surety is a promise by a surety or guarantor to pay ...

proved worthless, so the sheriff was ordered to take appropriate action.

Erdington was concerned that the church benefit from the town's booming trade, which was based mainly on wool. In 1258 Erdington secured for the deanery the lucrative right to hold a "weekly market on Wednesaday at Wolverhampton, co. Stafford, and of a yearly fair there on the vigil and Feast of Saints Peter and Paul and the six days following," both of which took place thereafter at the foot of the church steps. Erdington took care to placate other local magnates who might take offence at the growth of Wolverhampton, foremost among them being Roger de Somery, lord of neighbouring Sedgley. Somery was an ambitious man who wanted to establish himself in a castle at Dudley and had an interest in the town's future. In February 1261 the two sides came to a compromise. Erdington conceded various useful pieces of land, including 20 acres at Wolverhampton and roadside verges on the route through Ettingshall and Sedgley, in return for an annual rent of eight pounds of wax

Waxes are a diverse class of organic compounds that are lipophilic, malleable solids near ambient temperatures. They include higher alkanes and lipids, typically with melting points above about 40 °C (104 °F), melting to give low ...

– useful to the church with its constant need for candles. Somery accepted Erdington's market without challenge, on condition his own family, as well as the burgesses and villeins might travel to and from Wolverhampton without tolls. In 1263 Erdington reinforced the position of his own burgesses by granting them the right to succeed to their burgages freely, on the same terms as those of Stafford. He established a chaplain in the church, probably a chantry priest. In 1398 a Chantry of St Mary was mentioned when Thomas of Wrottesley was appointed to it by the king: this may have been Erdington's chantry. Whatever the exemptions granted by earlier kings, it is clear that Wolverhampton and the other royal chapels in Staffordshire were paying secular taxation by this time: Wolverhampton's payment of 53s. 4d. towards the levy of a tenth was acknowledged in April 1268, along with similar sums from the chapels at Tettenhall, Stafford and Penkridge.

Theodosius de Camilla

The next dean was Theodosius de Camilla, an Italian cleric related to the powerful Fieschi familyGenoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the List of cities in Italy, sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian ce ...

, and a cousin of Pope Adrian V.[Calendar of Papal Registers, Volume 1, Regesta 37, 4 Kal. July, 1275.]

/ref> He was appointed on 10 January 1269, following Erdington's death. As early as 1218, It was roundly asserted at Lichfield Assizes that "the Church and Deanery of Wuvlrenehamtum is of the King's gift. Giles de Ardington holds it by gift of the present King." However, in 1252, after Henry de Hastings perished in the Seventh Crusade, it was made clear that he had held the advowson

Advowson () or patronage is the right in English law of a patron (avowee) to present to the diocesan bishop (or in some cases the ordinary if not the same person) a nominee for appointment to a vacant ecclesiastical benefice or church living, ...

of Wolverhampton deanery. Although the king was keen to assert his right, it seems likely that he was willing to sell or rent it if the need was great enough. However, the appointment of Theodosius was by the king himself. Moreover, the notification made clear that it included collation to the prebends – a potentially lucrative right.

Theodosius was just as vigorous as Erdington in defending the college, but his tenure began to demonstrate some of the disadvantages of royal appointment. He was a notorious pluralist and a career diplomat rather than a pastor. In 1274 he came into conflict with Canterbury over the issue and his

Theodosius was just as vigorous as Erdington in defending the college, but his tenure began to demonstrate some of the disadvantages of royal appointment. He was a notorious pluralist and a career diplomat rather than a pastor. In 1274 he came into conflict with Canterbury over the issue and his rectory

A clergy house is the residence, or former residence, of one or more priests or ministers of religion. Residences of this type can have a variety of names, such as manse, parsonage, rectory or vicarage.

Function

A clergy house is typically ow ...

of Wingham, Kent

Wingham is a village and civil parishes in England, civil parish in the Dover District of Kent, England. The village lies along the ancient coastal road, now the A257, from Richborough to London, and is close to Canterbury.

History

A settlement ...

sequestrated by the Dominican Archbishop Robert Kilwardby until restored to him on the intervention of his cousin, Cardinal Ottobuono de' Fieschi

Pope Adrian V (Latin: ''Adrianus V''; c. 1210/1220 – 18 August 1276), born Ottobuono de' Fieschi, was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 11 July 1276 to his death on 18 August 1276. He was an envoy of Pope Cle ...

.[ In 1276 he had even obtained a dispensation from ]Pope John XXI

Pope John XXI ( la, Ioannes XXI; – 20 May 1277), born Pedro Julião ( la, Petrus Iulianus), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 September 1276 to his death on 20 May 1277. Apart from Damasus I (from ...

allowing him to hold both Wingham and Wolverhampton, without need of residence or even ordination

Ordination is the process by which individuals are Consecration, consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorization, authorized (usually by the religious denomination, denominational ...

, suggesting he was no more than a sub-deacon. The dispensation was conditional on his resigning two other benefices, one in the Diocese of Lincoln

The Diocese of Lincoln forms part of the Province of Canterbury in England. The present diocese covers the ceremonial county of Lincolnshire.

History

The diocese traces its roots in an unbroken line to the Pre-Reformation Diocese of Leices ...

, the other York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

. No mention was ever made in this context of his prebends of Bartonsham in Hereford Cathedral

Hereford Cathedral is the cathedral church of the Anglican Diocese of Hereford in Hereford, England.

A place of worship has existed on the site of the present building since the 8th century or earlier. The present building was begun in 1079. S ...

and Yetminster

Yetminster is a village and civil parish in the English county of Dorset. It lies south-west of Sherborne. It is sited on the River Wriggle, a tributary of the River Yeo, and is built almost entirely of honey-coloured limestone, which gives ...

Prima in Salisbury Cathedral

Salisbury Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary, is an Anglican cathedral in Salisbury, England. The cathedral is the mother church of the Diocese of Salisbury and is the seat of the Bishop of Salisbury.

The buildi ...

[ His absences from the country on royal or personal business continued throughout his life. In February 1286 ]Edward I

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he ruled the duchies of Aquitaine and Gascony as a vassal o ...

gave him letters to cover a visit to the Papal Curia and he appointed attorneys for his absence. In September 1289, again going overseas, he appointed Andrew of Genoa his attorney for a year. He was sent abroad again by the king in January 1291, and nominated attorneys until Midsummer.

Andrew of Genoa, was the main representative of Theodosius in and around Wolverhampton, his bailiff

A bailiff (from Middle English baillif, Old French ''baillis'', ''bail'' "custody") is a manager, overseer or custodian – a legal officer to whom some degree of authority or jurisdiction is given. Bailiffs are of various kinds and their offi ...

and proctor

Proctor (a variant of ''procurator'') is a person who takes charge of, or acts for, another.

The title is used in England and some other English-speaking countries in three principal contexts:

* In law, a proctor is a historical class of lawye ...

as well as his attorney. The deanery lands were exploited with great thoroughness. Around 1274, finding that tenants at Bilbrook had failed to pay their tallage or hand over their best pigs in return for pannage

Pannage (also referred to as ''Eichelmast'' or ''Eckerich'' in Germany, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Austria, Slovenia and Croatia) is the practice of releasing livestock-domestic pig, pigs in a forest, so that they can feed on falle ...

in the woods, the deanery simply seized their cattle on the road and sat out their attempt to gain restitution. In 1292 Andrew appeared in court for Theodosius as his bailiff in a dispute with the Abbot of Croxden over woodland at Oaken. After getting the case postponed with ingenious arguments about the true pronunciation of the name of the place, he resorted to challenging the property boundary and the jury found against him. It seems that he was ruthless in extracting value from the dean's woodland. The exploitation was so intense that Roger Le Strange, the Justice in Eyre

In English law, the justices in eyre were the highest magistrates, and presided over the ''court of justice-seat'', a triennial court held to punish offenders against the forest law and enquire into the state of the forest and its officers ('' eyr ...

took deanery woods back into Cannock Chase for protection: this area was recovered in June 1293. A writ for a full-scale inquisition into infractions of deanery and prebendal rights was issued later that year from Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

and it was held in Lichfield, with numerous issues rehearsed, particularly concerning woods and assart

Assarting is the act of clearing forested lands for use in agriculture or other purposes. In English land law, it was illegal to assart any part of a royal forest without permission. This was the greatest trespass that could be committed in a ...

s around Hatherton, Wednesfield and Codsall.

At least some of the prebendaries were royal servants with pressing obligations elsewhere, while some travelled widely abroad. Geoffrey of Aspall was keeper of the wardrobe to Queen Eleanor, responsible for her finances. Theodosius collated at least three of his relatives to prebends. Edward de Camilla is known from a case in which Master Andrew was trying to recover £50 arrears for the farm of the deanery and Edward's prebend, which was let to a Wolverhampton entrepreneur: the largely absentee dean and canons did not manage their own estates but lived on advance fees paid by the farmers. Another Theodosius of Camilla, a canon of Wolverhampton, made preparations for a two-year overseas trip in 1298, nominating Andrew as his attorney, three years after Dean Theodosius died. Gregory of Camilla was setting off for Rome in July 1304.

Although he was seldom if ever present in Wolverhampton, the church was important enough to Theodosius for him to face down even the Archbishop of Canterbury in its defence. The Second Council of Lyons in 1274 denounced a number of abuses of which the prebendaries were plainly guilty, including non-residence and pluralism. The

Although he was seldom if ever present in Wolverhampton, the church was important enough to Theodosius for him to face down even the Archbishop of Canterbury in its defence. The Second Council of Lyons in 1274 denounced a number of abuses of which the prebendaries were plainly guilty, including non-residence and pluralism. The Franciscan

The Franciscans are a group of related Mendicant orders, mendicant Christianity, Christian Catholic religious order, religious orders within the Catholic Church. Founded in 1209 by Italian Catholic friar Francis of Assisi, these orders include t ...

Archbishop John Peckham

John Peckham (c. 1230 – 8 December 1292) was Archbishop of Canterbury in the years 1279–1292. He was a native of Sussex who was educated at Lewes Priory and became a Friar Minor about 1250. He studied at the University of Paris under B ...

was determined to bring the royal chapels to book. On 1 April 1280, while staying at Trentham Priory

Trentham Priory was a Christian priory in North Staffordshire, England, near the confluence between the young River Trent and two local streams, where the Trentham Estate is today.

History The Mercian nunnery

A nunnery is said to have been built ...

, he wrote a letter to the king, setting out clearly his intention to carry out a metropolitical visitation, against an explicit royal prohibition he had just received, and of backing it with excommunications where necessary.

On 27 July 1280, Peckham appeared at the doors of St Peter's, which were shut against him. He was forced to write to the dean and canons from the church cemetery, noting that "Tedisius of Camilla, who calls himself dean," was apparently overseas. He threatened them all with excommunication and summoned the prebendaries to meet him on 31 July. However, the canons of all the royal chapels in the diocese ignored him and on 11 November the sentences of excommunication were confirmed. On 13 December Peckham appointed Philip of St Austell, a cleric on his own staff, to complete the visitation. In February 1281 he wrote to the king to reiterate and to justify the sentences: apparently he was already feeling the force of royal censure. The pressure on Peckham seems to have been building, as he was compelled to write to the Bishop of Dublin

The Archbishop of Dublin is an archepiscopal title which takes its name after Dublin, Ireland. Since the Reformation, there have been parallel apostolic successions to the title: one in the Catholic Church and the other in the Church of Irelan ...

, who was dean of Penkridge, and at least twice more to the king, arguing his case, which rested on his own interpretation of the precedent of Archbishop Boniface. On 23 February he wrote to Jordan, Bishop Meyland's official at Lichfield, warning him that it was a profanation of the sacrament to allow the excommunicated clerics to officiate at Mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different elementar ...

. However, only a day later he wrote to the king to inform him that he had postponed the excommunications, excepting those of the clergy at Penkridge, pending the calling of a Parliament. Peckham agreed to allow the issue to be decided by a tribunal specially constituted for the purpose and on 21 May nominated the Dean of Arches

The Dean of the Arches is the judge who presides in the provincial ecclesiastical court of the Archbishop of Canterbury. This court is called the Arches Court of Canterbury. It hears appeals from consistory courts and bishop's disciplinary trib ...

as his proctor. An agreement was reached the following month by which Bishop Meyland accepted that six of the chapels, including Wolverhampton, were beyond the reach of any ordinary

Ordinary or The Ordinary often refer to:

Music

* ''Ordinary'' (EP) (2015), by South Korean group Beast

* ''Ordinary'' (Every Little Thing album) (2011)

* "Ordinary" (Two Door Cinema Club song) (2016)

* "Ordinary" (Wayne Brady song) (2008)

* ...

, on condition that he be honourably received in them, as before.

The archbishop's feud with Theodosius continued, however. He briefed his proctor in Rome for a campaign, stressing the dean's absenteeism and pluralism. In 1282 Camilla was excommunicated and deprived of his Wingham rectory and the church at Tarring. However, events began to move in his direction early in the following year, when

The archbishop's feud with Theodosius continued, however. He briefed his proctor in Rome for a campaign, stressing the dean's absenteeism and pluralism. In 1282 Camilla was excommunicated and deprived of his Wingham rectory and the church at Tarring. However, events began to move in his direction early in the following year, when Pope Martin IV

Pope Martin IV ( la, Martinus IV; c. 1210/1220 – 28 March 1285), born Simon de Brion, was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 22 February 1281 to his death on 28 March 1285. He was the last French pope to have ...

ordered Peckham to restore the churches. His impunity was largely the result of his powerful contacts, including Benedetto Caetani, the future Pope Boniface VIII

Pope Boniface VIII ( la, Bonifatius PP. VIII; born Benedetto Caetani, c. 1230 – 11 October 1303) was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 24 December 1294 to his death in 1303. The Caetani, Caetani family was of b ...

: Peckham wrote directly to him in an attempt to improve relations, but without result. Theodosius then began to pursue Peckham and his associates, the incumbents of the disputed churches, through the ecclesiastical courts. After arguments at a tribunal, the sides agreed to arbitration by Bernard, Bishop of Porto, which resulted in a triumph for Theodosius. Peckham and his group were ordered to pay him and his successors a pension of 200 marks in compensation. When he died in 1295, he was still Dean of Wolverhampton, despite all opposition.

Erdington and Theodosius brought St Peter's to its medieval peak of prosperity and influence, although its spiritual standards were already notorious. The economic well-being of the church was greatly improved by their unwillingness to pay tax. Theodosius was deriving 50 marks a year from the deanery by the 1290s, but declared only 20 marks for tax purposes. The total taxable value of the church was reported in the ''Taxatio Ecclesiastica

The ''Taxatio Ecclesiastica'', often referred to as the ''Taxatio Nicholai'' or just the ''Taxatio'', compiled in 1291–92 under the order of Pope Nicholas IV, is a detailed database valuation for ecclesiastical taxation of English, Welsh, an ...

'', compiled 1291-2, as only £54 13s. 4d. This included six prebends, which are named for the first time at this point: Featherstone, Willenhall, Wobaston, Hilton, Monmore, Kinvaston. In addition there was the chantry of St. Mary in Hatherton, which was shortly to become a seventh prebend.

1300–1480: Neglect and revival

Dilapidation of fabric and alienation of land

Philip of Everdon was appointed dean by Edward I on 15 September 1295. In December 1302 he was warned by the king to revoke the collation of Ottobonus Malespania to a prebend by Papal provision

''Canonical provision'' is a term of the canon law of the Catholic Church, signifying regular induction into a benefice.

Analysis

It comprises three distinct acts - the designation of the person, canonical institution, and installation. In variou ...

. The following month the king ordered the sheriff to defend the rights of Nicholas de Luvetot, whom Philip had previously collated to the prebend of Kinvaston, against the Italian claimant. The incident seems to have marked a serious breach between king and dean. Further problems were to follow. While the 13th century deans had been shrewd in business, enriching themselves through improvements to the church estates, their 14th century successors would have struggled because of the economic crisis of the early 14th century and the ensuing Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

. However, they frittered away the assets, and in some cases resorted to plain embezzlement. An underlying problem was the enclosure of waste for sale, which alienated it from the church's estates. On 1 May 1311 John of Everdon (1303–23) was licensed to enclose no less than 400 acres at Prestwood and Blakeley, on the edge of Wednesfield and inside Cannock Chase: by 1322 he was selling off this land in fee simple

In English law, a fee simple or fee simple absolute is an estate in land, a form of freehold ownership. A "fee" is a vested, inheritable, present possessory interest in land. A "fee simple" is real property held without limit of time (i.e., perm ...

to John Hampton. In 1323, after John's death, Edward II

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir apparent to t ...

ordered the escheator to sequester lands that he had alienated without licence, "to the prejudice of the king and the peril of disherison of the deanery, whereat the king is much disturbed." An ''inspeximus'' of 1376 revealed another of John's land sales in the area, and one dating from the time of Theodosius, but confirms both, "notwithstanding that the said plots were of the foundation of the said church, which is now called the king's free chapel of Wolvernehampton."

Dean Hugh Ellis (1328–39) was suspected of giving away much of the stock of the deanery and left the buildings dilapidated. After his death Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring r ...

ordered a thorough survey and inquiry by a commission of justices in the presence of his new dean, Philip de Weston. A further commission in March 1340 added an investigation of the books, vestment

Vestments are liturgical garments and articles associated primarily with the Christian religion, especially by Eastern Churches, Catholics (of all rites), Anglicans, and Lutherans. Many other groups also make use of liturgical garments; this ...

s and ornaments, while in the following year the king opined that Ellis had "wasted the goods and possessions of the deanery, whereby the divine worship and works of piety of old established there have been withdrawn." The report revealed great prodigality. A vast quantity of expensive cutlery, silverware, tableware, linen, precious stones, horses, livestock, even a relic of the True Cross

The True Cross is the cross upon which Jesus was said to have been crucified, particularly as an object of religious veneration. There are no early accounts that the apostles or early Christians preserved the physical cross themselves, althoug ...

, had been dispersed among friends and retainers or stolen from Hugh's custody. His own manse

A manse () is a clergy house inhabited by, or formerly inhabited by, a minister, usually used in the context of Presbyterian, Methodist, Baptist and other Christian traditions.

Ultimately derived from the Latin ''mansus'', "dwelling", from '' ...

had fallen into serious disrepair, with defects in the walls, kitchen, part of the roof and farm buildings. Three cottages at Wednesfield had fallen into disrepair and been plundered for the materials. Oak

An oak is a tree or shrub in the genus ''Quercus'' (; Latin "oak tree") of the beech family, Fagaceae. There are approximately 500 extant species of oaks. The common name "oak" also appears in the names of species in related genera, notably ''L ...

s worth £10 had been felled and sold off at Pelsall. A mill and its pool were in disrepair. There were substantial tax arrears. However, the vestments and ornaments were not found defective. Philip de Weston himself seems to have problems with one of his bailiffs, John Buffry, who failed to render account of his work and failed to appear in court at Michaelmas

Michaelmas ( ; also known as the Feast of Saints Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael, the Feast of the Archangels, or the Feast of Saint Michael and All Angels) is a Christian festival observed in some Western liturgical calendars on 29 September, a ...

1356. It transpired that he had defrauded Weston and a chaplain of 55 marks. He was outlaw

An outlaw, in its original and legal meaning, is a person declared as outside the protection of the law. In pre-modern societies, all legal protection was withdrawn from the criminal, so that anyone was legally empowered to persecute or kill them ...

ed, surrendered himself and was confined in the Fleet Prison: the king pardoned him the following May. The incompetence and waste seems to have infected many of the royal chapels in the region and in 1368 the king, noting that they were immune from ordinary jurisdiction, set up commissions to carry out visitations of Wolverhampton, St Mary's Church, Bridgnorth, Stafford, Tettenhall and St Mary's Church, Shrewsbury

St Mary's Church is a redundant Anglican church in St Mary's Place, Shrewsbury, Shropshire, England. It is recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a designated Grade I listed building, and is under the care of the Churches Co ...

. He alleged alienation, poor estate management, loss of books and vestments, the dissolute lives of the canons, neglect of worship and alms

Alms (, ) are money, food, or other material goods donated to people living in poverty. Providing alms is often considered an act of virtue or Charity (practice), charity. The act of providing alms is called almsgiving, and it is a widespread p ...

giving, and misappropriation of funds. The visitation of Wolverhampton was headed by the Abbots of Halesowen and Evesham

Evesham () is a market town and parish in the Wychavon district of Worcestershire, in the West Midlands region of England. It is located roughly equidistant between Worcester, Cheltenham and Stratford-upon-Avon. It lies within the Vale of Evesha ...

. In fact, Wolverhampton's deans had remained zealous in maintaining the college's rights and privileges, getting successive kings to confirm its charters, if most of the other accusations were true.

Continued decay and emerging opposition

After the king's visitation, the running of the church was much as before. Dean Richard Postell

Richard Postell (died 1400) was a Canon of Windsor from 1373 to 1400''Fasti Wyndesorienses'', May 1950. S.L. Ollard. Published by the Dean and Canons of St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle and Dean of Wolverhampton.

Career

He was appointed:

*Rect ...

(1373–94) was careful of the church's liberties: in 1379 he obtained ''inspeximus'' and confirmation of letters patent

Letters patent ( la, litterae patentes) ( always in the plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, president or other head of state, generally granting an office, right, monopoly, titl ...

of Edward III, a document that confirmed charters further back, to the time of Edward the Confessor. However, an inquisition of 1393 found that he had dismissed the six priests funded by Henry I's grant to celebrate the liturgy and for 19 years he had diverted the income, amounting to £26 13s. 4d. annually, to his own uses.[ It seems that he also embezzled money entrusted to him by prominent lay members of the congregation, Roger Leveson, John Salford and John Waterfall. There were complaints and appeals to the king about the judicial functions of his officials, with the cases being referred to the ]Archdeacon of Coventry

The Archdeacon of Coventry is a senior ecclesiastical officer in the Church of England Diocese of Coventry. The post has been called the ''Archdeacon Pastor'' since 2012.

History

The post was historically within the Diocese of Lichfield beginning ...

for decision, presumably because these were matters concerning marriage and family. Near the end of his life his exasperated tenants launched a rent strike.

Lawrence Allerthorpe (1394–1406) continued to neglect the deanery. For his first three years of office he was also dean of St Mary's Stafford. In September 1399 he was made a Baron of the Exchequer

The Barons of the Exchequer, or ''barones scaccarii'', were the judges of the English court known as the Exchequer of Pleas. The Barons consisted of a Chief Baron of the Exchequer and several puisne (''inferior'') barons. When Robert Shute was a ...

by Henry IV, who had seized power that year. In February 1401 Archbishop Thomas Arundel sent delegates to carry out a visitation of St. Peter's. Allerthorpe objected but had to back down, probably as Arundel was a key pillar of the new régime. Allerthorpe certainly retained royal favour after the affair and on 31 May 1401 was appointed Lord High Treasurer

The post of Lord High Treasurer or Lord Treasurer was an English government position and has been a British government position since the Acts of Union of 1707. A holder of the post would be the third-highest-ranked Great Officer of State in ...

, a near-impossible job, given the disorder in the country and the low levels of royal receipts, as he made clear to the king later in the year. At Michaelmas 1402 his attorney appeared in court to complain that a group of Wolverhampton people had attacked and torn down the refreshment stalls he maintained in the town, perhaps enraged at a commercial monopoly enforced under spiritual excuses: the culprits did not appear and the case disappears from view. After Allerthorpe's death, rumours reached the king that great damage had been done to the deanery assets: the chancel