St Boniface on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Boniface, OSB ( la, Bonifatius; 675 – 5 June 754) was an English

The earliest Bonifacian , Willibald's, does not indicate his place of birth but says that at an early age he attended a monastery ruled by Abbot Wulfhard in , or ''Examchester'', which seems to denote

The earliest Bonifacian , Willibald's, does not indicate his place of birth but says that at an early age he attended a monastery ruled by Abbot Wulfhard in , or ''Examchester'', which seems to denote

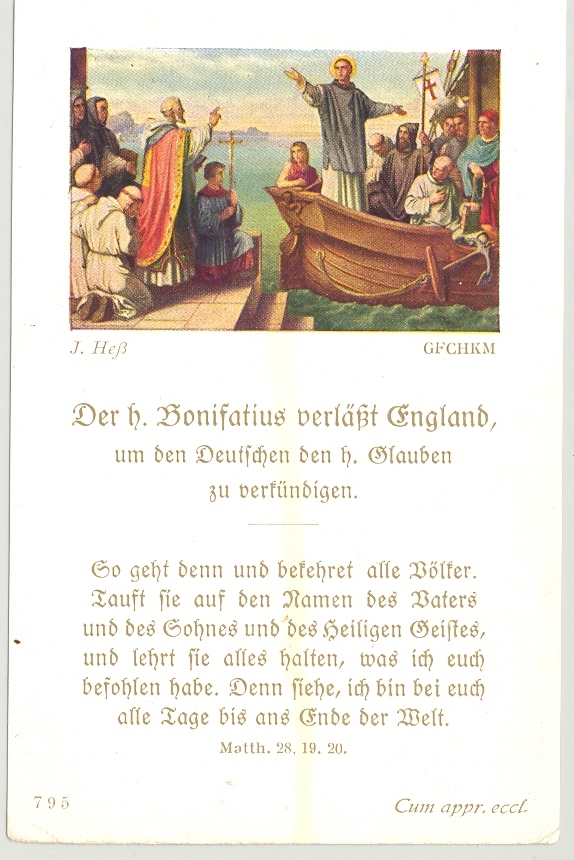

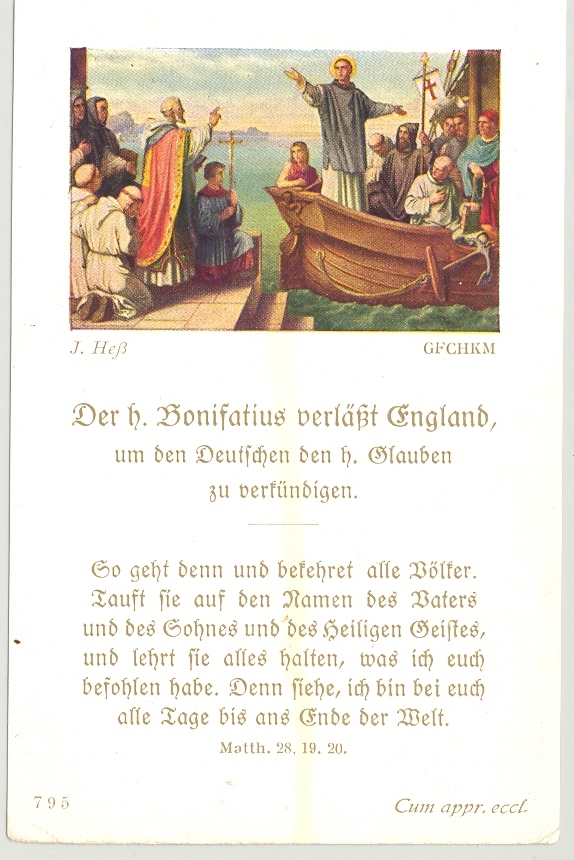

Boniface first left for the continent in 716. He traveled to

Boniface first left for the continent in 716. He traveled to

The support of the Frankish mayors of the palace ( maior domos), and later the early

The support of the Frankish mayors of the palace ( maior domos), and later the early

According to the , Boniface had never relinquished his hope of converting the

According to the , Boniface had never relinquished his hope of converting the

Saint Boniface's feast day is celebrated on 5 June in the Roman

Saint Boniface's feast day is celebrated on 5 June in the Roman

The first German celebration on a fairly large scale was held in 1805 (the 1,050th anniversary of his death), followed by a similar celebration in a number of towns in 1855; both of these were predominantly Catholic affairs emphasizing the role of Boniface in German history. But if the celebrations were mostly Catholic, in the first part of the 19th century the respect for Boniface in general was an ecumenical affair, with both Protestants and Catholics praising Boniface as a founder of the German nation, in response to the German nationalism that arose after the Napoleonic era came to an end. The second part of the 19th century saw increased tension between Catholics and Protestants; for the latter,

The first German celebration on a fairly large scale was held in 1805 (the 1,050th anniversary of his death), followed by a similar celebration in a number of towns in 1855; both of these were predominantly Catholic affairs emphasizing the role of Boniface in German history. But if the celebrations were mostly Catholic, in the first part of the 19th century the respect for Boniface in general was an ecumenical affair, with both Protestants and Catholics praising Boniface as a founder of the German nation, in response to the German nationalism that arose after the Napoleonic era came to an end. The second part of the 19th century saw increased tension between Catholics and Protestants; for the latter,

"St. Boniface"

entry from online version of the ''Catholic Encyclopedia'', 1913 edition. * *Talbot, C. H., ed. ''The Anglo-Saxon Missionaries in Germany: Being the Lives of S.S. Willibrord, Boniface, Strum, Leoba and Lebuin, together with the Hodoeporicon of St. Willibald and a Selection from the Correspondence of St. Boniface''. New York: Sheed and Ward, 1954. **The Bonifacian ''vita'' was republished in Noble, Thomas F. X. and Thomas Head, eds. ''Soldiers of Christ: Saints and Saints' Lives in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages''. University Park: Pennsylvania State UP, 1995. 109–40. * * *

''Butler's Lives of the Saints''

Wilhelm Levison, ''Vitae Sancti Bonifatii''

{{DEFAULTSORT:Boniface 7th-century births 754 deaths 8th-century Christian theologians Anglo-Saxon saints Archbishops of Mainz Christmas trees Diplomats of the Holy See German folklore Medieval German saints History of Catholicism in Germany Medieval legends People from Crediton West Saxon saints Burials at Fulda Cathedral 8th-century bishops 8th-century Frankish saints 8th-century Frankish writers 8th-century English writers 8th-century poets 8th-century Latin writers Roman Catholic bishops in Germany Anglican saints English Roman Catholic saints English Roman Catholics

Benedictine

, image = Medalla San Benito.PNG

, caption = Design on the obverse side of the Saint Benedict Medal

, abbreviation = OSB

, formation =

, motto = (English: 'Pray and Work')

, found ...

monk and leading figure in the Anglo-Saxon mission to the Germanic parts of the Frankish Empire

Francia, also called the Kingdom of the Franks ( la, Regnum Francorum), Frankish Kingdom, Frankland or Frankish Empire ( la, Imperium Francorum), was the largest post-Roman barbarian kingdom in Western Europe. It was ruled by the Franks dur ...

during the eighth century. He organised significant foundations of the church in Germany and was made archbishop of Mainz

The Elector of Mainz was one of the seven Prince-electors of the Holy Roman Empire. As both the Archbishop of Mainz and the ruling prince of the Electorate of Mainz, the Elector of Mainz held a powerful position during the Middle Ages. The Archb ...

by Pope Gregory III

Pope Gregory III ( la, Gregorius III; died 28 November 741) was the bishop of Rome from 11 February 731 to his death. His pontificate, like that of his predecessor, was disturbed by Byzantine iconoclasm and the advance of the Lombards, in which ...

. He was martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an external ...

ed in Frisia in 754, along with 52 others, and his remains were returned to Fulda

Fulda () (historically in English called Fuld) is a town in Hesse, Germany; it is located on the river Fulda and is the administrative seat of the Fulda district (''Kreis''). In 1990, the town hosted the 30th Hessentag state festival.

Histor ...

, where they rest in a sarcophagus

A sarcophagus (plural sarcophagi or sarcophaguses) is a box-like funeral receptacle for a corpse, most commonly carved in stone, and usually displayed above ground, though it may also be buried. The word ''sarcophagus'' comes from the Gre ...

which has become a site of pilgrimage.

Boniface's life and death as well as his work became widely known, there being a wealth of material available — a number of , especially the near-contemporary , legal documents, possibly some sermons, and above all his correspondence. He is venerated as a saint in the Christian church and became the patron saint

A patron saint, patroness saint, patron hallow or heavenly protector is a saint who in Catholic Church, Catholicism, Anglicanism, or Eastern Orthodoxy is regarded as the heavenly advocacy, advocate of a nation, place, craft, activity, class, ...

of Germania

Germania ( ; ), also called Magna Germania (English: ''Great Germania''), Germania Libera (English: ''Free Germania''), or Germanic Barbaricum to distinguish it from the Roman province of the same name, was a large historical region in north ...

, known as the "Apostle to the Germans".

Norman F. Cantor

Norman Frank Cantor (November 19, 1929 – September 18, 2004) was a Canadian-American historian who specialized in the medieval period. Known for his accessible writing and engaging narrative style, Cantor's books were among the most widely rea ...

notes the three roles Boniface played that made him "one of the truly outstanding creators of the first Europe, as the apostle of Germania, the reformer of the Frankish church, and the chief fomentor of the alliance between the papacy

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

and the Carolingian family." Through his efforts to reorganize and regulate the church of the Franks, he helped shape the Latin Church

, native_name_lang = la

, image = San Giovanni in Laterano - Rome.jpg

, imagewidth = 250px

, alt = Façade of the Archbasilica of St. John in Lateran

, caption = Archbasilica of Saint Jo ...

in Europe, and many of the dioceses he proposed remain today. After his martyrdom, he was quickly hailed as a saint in Fulda and other areas in Germania and in England. He is still venerated strongly today by German Catholics. Boniface is celebrated as a missionary; he is regarded as a unifier of Europe, and he is regarded by German Roman Catholics as a national figure.

In 2019, Devon County Council

Devon County Council is the county council administering the English county of Devon. Based in the city of Exeter, the council covers the non-metropolitan county area of Devon. Members of the council (councillors) are elected every four years to ...

with the support of the Anglican and Catholic churches in Exeter

Exeter () is a city in Devon, South West England. It is situated on the River Exe, approximately northeast of Plymouth and southwest of Bristol.

In Roman Britain, Exeter was established as the base of Legio II Augusta under the personal c ...

and Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymout ...

, officially recognised St Boniface as the Patron Saint of Devon

Devon ( , historically known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South West England. The most populous settlement in Devon is the city of Plymouth, followed by Devon's county town, the city of Exeter. Devon is ...

.

Early life

The earliest Bonifacian , Willibald's, does not indicate his place of birth but says that at an early age he attended a monastery ruled by Abbot Wulfhard in , or ''Examchester'', which seems to denote

The earliest Bonifacian , Willibald's, does not indicate his place of birth but says that at an early age he attended a monastery ruled by Abbot Wulfhard in , or ''Examchester'', which seems to denote Exeter

Exeter () is a city in Devon, South West England. It is situated on the River Exe, approximately northeast of Plymouth and southwest of Bristol.

In Roman Britain, Exeter was established as the base of Legio II Augusta under the personal c ...

, and may have been one of many built by local landowners and churchmen; nothing else is known of it outside the Bonifacian . This monastery is believed to have occupied the site of the Church of St Mary Major in the City of Exeter

Exeter () is a city in Devon, South West England. It is situated on the River Exe, approximately northeast of Plymouth and southwest of Bristol.

In Roman Britain, Exeter was established as the base of Legio II Augusta under the personal com ...

, demolished in 1971, next to which was later built Exeter Cathedral

Exeter Cathedral, properly known as the Cathedral Church of Saint Peter in Exeter, is an Anglican cathedral, and the seat of the Bishop of Exeter, in the city of Exeter, Devon, in South West England. The present building was complete by about 14 ...

. Later tradition places his birth at Crediton

Crediton is a town and civil parish in the Mid Devon district of Devon in England. It stands on the A377 Exeter to Barnstaple road at the junction with the A3072 road to Tiverton, about north west of Exeter and around from the M5 motorwa ...

, but the earliest mention of Crediton in connection to Boniface is from the early fourteenth century, in John Grandisson

The '' British Museum">John Grandisson Triptych'', displaying on two small escutcheons the arms of Bishop Grandisson. British Museum

John de Grandisson (1292 – 16 July 1369), also spelt Grandison, was Bishop of Exeter, in Devon, England, from ...

's ''Legenda Sanctorum: The Proper Lessons for Saints' Days according to the use of Exeter''. In one of his letters Boniface mentions he was "born and reared... nthe synod of London", but he may have been speaking metaphorically. His English name is recorded as being Winfrid or Winfred.

According to the , Winfrid was of a respected and prosperous family. Against his father's wishes he devoted himself at an early age to the monastic life. He received further theological training in the Benedictine

, image = Medalla San Benito.PNG

, caption = Design on the obverse side of the Saint Benedict Medal

, abbreviation = OSB

, formation =

, motto = (English: 'Pray and Work')

, found ...

monastery and minster of Nhutscelle (Nursling), not far from Winchester, which under the direction of abbot Winbert had grown into an industrious centre of learning in the tradition of Aldhelm

Aldhelm ( ang, Ealdhelm, la, Aldhelmus Malmesberiensis) (c. 63925 May 709), Abbot of Malmesbury Abbey, Bishop of Sherborne, and a writer and scholar of Latin poetry, was born before the middle of the 7th century. He is said to have been the ...

. Winfrid taught in the abbey school and at the age of 30 became a priest; in this time, he wrote a Latin grammar, the , besides a treatise on verse and some Aldhelm

Aldhelm ( ang, Ealdhelm, la, Aldhelmus Malmesberiensis) (c. 63925 May 709), Abbot of Malmesbury Abbey, Bishop of Sherborne, and a writer and scholar of Latin poetry, was born before the middle of the 7th century. He is said to have been the ...

-inspired riddles. While little is known about Nursling outside of Boniface's , it seems clear that the library there was significant. To supply Boniface with the materials he needed, it would have contained works by Donatus, Priscian

Priscianus Caesariensis (), commonly known as Priscian ( or ), was a Latin grammarian and the author of the ''Institutes of Grammar'', which was the standard textbook for the study of Latin during the Middle Ages. It also provided the raw materia ...

, Isidore, and many others. Around 716, when his abbot Wynberth of Nursling died, he was invited (or expected) to assume his position—it is possible that they were related, and the practice of hereditary right among the early Anglo-Saxons would affirm this. Winfrid, however, declined the position and in 716 set out on a missionary expedition to Frisia.

Early missionary work in Frisia and Germania

Boniface first left for the continent in 716. He traveled to

Boniface first left for the continent in 716. He traveled to Utrecht

Utrecht ( , , ) is the fourth-largest city and a municipality of the Netherlands, capital and most populous city of the province of Utrecht. It is located in the eastern corner of the Randstad conurbation, in the very centre of mainland Nethe ...

, where Willibrord

Willibrord (; 658 – 7 November AD 739) was an Anglo-Saxon missionary and saint, known as the "Apostle to the Frisians" in the modern Netherlands. He became the first bishop of Utrecht and died at Echternach, Luxembourg.

Early life

His fath ...

, the "Apostle to the Frisians," had been working since the 690s. He spent a year with Willibrord, preaching in the countryside, but their efforts were frustrated by the war then being carried on between Charles Martel

Charles Martel ( – 22 October 741) was a Frankish political and military leader who, as Duke and Prince of the Franks and Mayor of the Palace, was the de facto ruler of Francia from 718 until his death. He was a son of the Frankish state ...

and Radbod, King of the Frisians

Redbad or Radbod (died 719) was the king (or duke) of Frisia from c. 680 until his death. He is often considered the last independent ruler of Frisia before Frankish domination. He defeated Charles Martel at Cologne. Eventually, Charles prevaile ...

. Willibrord fled to the abbey he had founded in Echternach

Echternach ( lb, Iechternach or (locally) ) is a commune with town status in the canton of Echternach, which is part of the district of Grevenmacher, in eastern Luxembourg. Echternach lies near the border with Germany, and is the oldest town in ...

(in modern-day Luxembourg

Luxembourg ( ; lb, Lëtzebuerg ; french: link=no, Luxembourg; german: link=no, Luxemburg), officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, ; french: link=no, Grand-Duché de Luxembourg ; german: link=no, Großherzogtum Luxemburg is a small land ...

) while Boniface returned to Nursling.

Boniface returned to the continent the next year and went straight to Rome, where Pope Gregory II

Pope Gregory II ( la, Gregorius II; 669 – 11 February 731) was the bishop of Rome from 19 May 715 to his death.

renamed him "Boniface", after the (legendary) fourth-century martyr Boniface of Tarsus

Saint Boniface of Tarsus was, according to legend, executed for being a Christian in the year 307 at Tarsus, where he had gone from Rome in order to bring back to his mistress Aglaida (also written Aglaia) relics of the martyrs.

Biography

Bon ...

, and appointed him missionary bishop for Germania

Germania ( ; ), also called Magna Germania (English: ''Great Germania''), Germania Libera (English: ''Free Germania''), or Germanic Barbaricum to distinguish it from the Roman province of the same name, was a large historical region in north ...

—he became a bishop without a diocese for an area that lacked any church organization. He would never return to England, though he remained in correspondence with his countrymen and kinfolk throughout his life.

According to the ''vitae'' Boniface felled the Donar Oak, Latinized by Willibald as "Jupiter's oak," near the present-day town of Fritzlar

Fritzlar () is a small town (pop. 15,000) in the Schwalm-Eder district in northern Hesse, Germany, north of Frankfurt, with a storied history.

The town has a medieval center ringed by a wall with numerous watch towers. Thirty-eight meters (125 ...

in northern Hesse

Hesse (, , ) or Hessia (, ; german: Hessen ), officially the State of Hessen (german: links=no, Land Hessen), is a state in Germany. Its capital city is Wiesbaden, and the largest urban area is Frankfurt. Two other major historic cities are Da ...

. According to his early biographer Willibald, Boniface started to chop the oak down, when suddenly a great wind, as if by miracle, blew the ancient oak over. When the gods did not strike him down, the people were amazed and converted to Christianity. He built a chapel dedicated to Saint Peter

) (Simeon, Simon)

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Bethsaida, Gaulanitis, Syria, Roman Empire

, death_date = Between AD 64–68

, death_place = probably Vatican Hill, Rome, Italia, Roman Empire

, parents = John (or Jonah; Jona)

, occupa ...

from its wood at the site—the chapel was the beginning of the monastery in Fritzlar. This account from the ''vita'' is stylized to portray Boniface as a singular character who alone acts to root out paganism. Lutz von Padberg and others point out that what the ''vitae'' leave out is that the action was most likely well-prepared and widely publicized in advance for maximum effect, and that Boniface had little reason to fear for his personal safety since the Frankish fortified settlement of Büraburg was nearby. According to Willibald, Boniface later had a church with an attached monastery built in Fritzlar, on the site of the previously built chapel, according to tradition.

Boniface and the Carolingians

The support of the Frankish mayors of the palace ( maior domos), and later the early

The support of the Frankish mayors of the palace ( maior domos), and later the early Pippinid

The Pippinids and the Arnulfings were two Frankish aristocratic families from Austrasia during the Merovingian period. They dominated the office of mayor of the palace after 687 and eventually supplanted the Merovingians as kings in 751, foundin ...

and Carolingian

The Carolingian dynasty (; known variously as the Carlovingians, Carolingus, Carolings, Karolinger or Karlings) was a Frankish noble family named after Charlemagne, grandson of mayor Charles Martel and a descendant of the Arnulfing and Pippi ...

rulers, was essential for Boniface's work. Boniface had been under the protection of Charles Martel

Charles Martel ( – 22 October 741) was a Frankish political and military leader who, as Duke and Prince of the Franks and Mayor of the Palace, was the de facto ruler of Francia from 718 until his death. He was a son of the Frankish state ...

from 723 onwards. The Christian Frankish leaders desired to defeat their rival power, the pagan Saxons, and to incorporate the Saxon lands into their own growing empire. Boniface's campaign of destruction of indigenous Germanic pagan sites may have benefited the Franks in their campaign against the Saxons.

In 732, Boniface traveled again to Rome to report, and Pope Gregory III

Pope Gregory III ( la, Gregorius III; died 28 November 741) was the bishop of Rome from 11 February 731 to his death. His pontificate, like that of his predecessor, was disturbed by Byzantine iconoclasm and the advance of the Lombards, in which ...

conferred upon him the pallium

The pallium (derived from the Roman ''pallium'' or ''palla'', a woolen cloak; : ''pallia'') is an ecclesiastical vestment in the Catholic Church, originally peculiar to the pope, but for many centuries bestowed by the Holy See upon metropoli ...

as archbishop with jurisdiction over what is now Germany. Boniface again set out for the German lands and continued his mission, but also used his authority to work on the relations between the papacy and the Frankish church. Rome wanted more control over that church, which it felt was much too independent and which, in the eyes of Boniface, was subject to worldly corruption. Charles Martel

Charles Martel ( – 22 October 741) was a Frankish political and military leader who, as Duke and Prince of the Franks and Mayor of the Palace, was the de facto ruler of Francia from 718 until his death. He was a son of the Frankish state ...

, after having defeated the forces of the Umayyad Caliphate

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by the ...

during the Battle of Tours

The Battle of Tours, also called the Battle of Poitiers and, by Arab sources, the Battle of tiles of Martyrs ( ar, معركة بلاط الشهداء, Maʿrakat Balāṭ ash-Shuhadā'), was fought on 10 October 732, and was an important battle ...

(732), had rewarded many churches and monasteries with lands, but typically his supporters who held church offices were allowed to benefit from those possessions. Boniface would have to wait until the 740s before he could try to address this situation, in which Frankish church officials were essentially sinecures, and the church itself paid little heed to Rome. During his third visit to Rome in 737–38, he was made papal legate

300px, A woodcut showing Henry II of England greeting the pope's legate.

A papal legate or apostolic legate (from the ancient Roman title ''legatus'') is a personal representative of the pope to foreign nations, or to some part of the Catholic ...

for Germany.

After Boniface's third trip to Rome, Charles Martel established four dioceses in Bavaria (Salzburg

Salzburg (, ; literally "Salt-Castle"; bar, Soizbuag, label=Austro-Bavarian) is the fourth-largest city in Austria. In 2020, it had a population of 156,872.

The town is on the site of the Roman settlement of ''Iuvavum''. Salzburg was founded ...

, Regensburg, Freising

Freising () is a university town in Bavaria, Germany, and the capital of the Freising ''Landkreis'' (district), with a population of about 50,000.

Location

Freising is the oldest town between Regensburg and Bolzano, and is located on the ...

, and Passau) and gave them to Boniface as archbishop and metropolitan

Metropolitan may refer to:

* Metropolitan area, a region consisting of a densely populated urban core and its less-populated surrounding territories

* Metropolitan borough, a form of local government district in England

* Metropolitan county, a typ ...

over all Germany east of the Rhine. In 745, he was granted Mainz as metropolitan see. In 742, one of his disciples, Sturm

Sturm (German for storm) may refer to:

People

* Sturm (surname), surname (includes a list)

* Saint Sturm (died 779), 8th-century monk

Food

* Federweisser, known as ''Sturm'' in Austria, wine in the fermentation stage

* Sturm Foods, an Ameri ...

(also known as Sturmi, or Sturmius), founded the abbey of Fulda

The Abbey of Fulda (German ''Kloster Fulda'', Latin ''Abbatia Fuldensis''), from 1221 the Princely Abbey of Fulda (''Fürstabtei Fulda'') and from 1752 the Prince-Bishopric of Fulda (''Fürstbistum Fulda''), was a Benedictine abbey and ecclesiasti ...

not far from Boniface's earlier missionary outpost at Fritzlar. Although Sturm was the founding abbot of Fulda, Boniface was very involved in the foundation. The initial grant for the abbey was signed by Carloman, the son of Charles Martel

Charles Martel ( – 22 October 741) was a Frankish political and military leader who, as Duke and Prince of the Franks and Mayor of the Palace, was the de facto ruler of Francia from 718 until his death. He was a son of the Frankish state ...

, and a supporter of Boniface's reform efforts in the Frankish church. Boniface himself explained to his old friend, Daniel of Winchester, that without the protection of Charles Martel he could "neither administer his church, defend his clergy, nor prevent idolatry".

According to German historian Gunther Wolf, the high point of Boniface's career was the Concilium Germanicum The Concilium Germanicum was the first major Church synod to be held in the eastern parts of the Frankish kingdoms. It was called by Carloman on 21 April 742/743 at an unknown location, and presided over by Boniface, who was solidified in his pos ...

, organized by Carloman in an unknown location in April 743. Although Boniface was not able to safeguard the church from property seizures by the local nobility, he did achieve one goal, the adoption of stricter guidelines for the Frankish clergy, who often hailed directly from the nobility. After Carloman's resignation in 747 he maintained a sometimes turbulent relationship with the king of the Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools, ...

, Pepin; the claim that he would have crowned Pepin at Soissons

Soissons () is a commune in the northern French department of Aisne, in the region of Hauts-de-France. Located on the river Aisne, about northeast of Paris, it is one of the most ancient towns of France, and is probably the ancient capital ...

in 751 is now generally discredited.

Boniface balanced this support and attempted to maintain some independence, however, by attaining the support of the papacy

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

and of the Agilolfing rulers of Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total l ...

. In Frankish, Hessian, and Thuringian territory, he established the dioceses of Würzburg

Würzburg (; Main-Franconian: ) is a city in the region of Franconia in the north of the German state of Bavaria. Würzburg is the administrative seat of the '' Regierungsbezirk'' Lower Franconia. It spans the banks of the Main River.

Würzbur ...

and Erfurt

Erfurt () is the capital and largest city in the Central German state of Thuringia. It is located in the wide valley of the Gera river (progression: ), in the southern part of the Thuringian Basin, north of the Thuringian Forest. It sits ...

. By appointing his own followers as bishops, he was able to retain some independence from the Carolingians, who most likely were content to give him leeway as long as Christianity was imposed on the Saxons and other Germanic tribes.

Last mission to Frisia

According to the , Boniface had never relinquished his hope of converting the

According to the , Boniface had never relinquished his hope of converting the Frisians

The Frisians are a Germanic ethnic group native to the coastal regions of the Netherlands and northwestern Germany. They inhabit an area known as Frisia and are concentrated in the Dutch provinces of Friesland and Groningen and, in Germany ...

, and in 754 he set out with a retinue for Frisia. He baptized a great number and summoned a general meeting for confirmation at a place not far from Dokkum

Dokkum is a Dutch fortified city in the municipality of Noardeast-Fryslân in the province of Friesland. It has 12,669 inhabitants (February 8, 2020). The fortifications of Dokkum are well preserved and are known as the ''bolwerken'' (bulwarks) ...

, between Franeker

Franeker (; fry, Frjentsjer) is one of the eleven historical cities of Friesland and capital of the municipality of Waadhoeke. It is located north of the Van Harinxmakanaal and about 20 km west of Leeuwarden. As of 1 January 2014, it had 12 ...

and Groningen

Groningen (; gos, Grunn or ) is the capital city and main municipality of Groningen province in the Netherlands. The ''capital of the north'', Groningen is the largest place as well as the economic and cultural centre of the northern part of t ...

. Instead of his converts, however, a group of armed robbers appeared who slew the aged archbishop. The mention that Boniface persuaded his (armed) comrades to lay down their arms: "Cease fighting. Lay down your arms, for we are told in Scripture not to render evil for evil but to overcome evil by good."

Having killed Boniface and his company, the Frisian bandits ransacked their possessions but found that the company's luggage did not contain the riches they had hoped for: "they broke open the chests containing the books and found, to their dismay, that they held manuscripts instead of gold vessels, pages of sacred texts instead of silver plates." They attempted to destroy these books, the earliest already says, and this account underlies the status of the Ragyndrudis Codex, now held as a Bonifacian relic in Fulda, and supposedly one of three books found on the field by the Christians who inspected it afterward. Of those three books, the Ragyndrudis Codex shows incisions that could have been made by sword or axe; its story appears confirmed in the Utrecht hagiography, the , which reports that an eye-witness saw that the saint at the moment of death held up a gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christian message (" the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words a ...

as spiritual protection. The story was later repeated by Otloh's ; at that time, the Ragyndrudis Codex seems to have been firmly connected to the martyrdom.

Boniface's remains were moved from the Frisian countryside to Utrecht, and then to Mainz, where sources contradict each other regarding the behavior of Lullus

Saint Lullus (Lull or Lul) (born about 710 AD in Wessex, died 16 October 786 in Hersfeld) was the first permanent archbishop of Mainz, succeeding Saint Boniface, and first abbot of the Benedictine Hersfeld Abbey. He is historiographically conside ...

, Boniface's successor as archbishop of Mainz. According to Willibald's Lullus allowed the body to be moved to Fulda, while the (later) , a hagiography of Sturm by Eigil of Fulda Eigil (also called Aeigil or Egil) (c. 750–822) was the fourth abbot of Fulda. He was the nephew and biographer of the abbey's founder and first abbot Saint Sturm. We know about Eigil primarily from the Latin ''Life'' (''Vita Aegili'') that the ...

, Lullus attempted to block the move and keep the body in Mainz.

His remains were eventually buried in the abbey church of Fulda after resting for some time in Utrecht

Utrecht ( , , ) is the fourth-largest city and a municipality of the Netherlands, capital and most populous city of the province of Utrecht. It is located in the eastern corner of the Randstad conurbation, in the very centre of mainland Nethe ...

, and they are entombed within a shrine beneath the high altar of Fulda Cathedral, previously the abbey church.

There is good reason to believe that the Gospel he held up was the 56, which shows damage to the upper margin, which has been cut back as a form of repair.

Veneration

Fulda

Veneration of Boniface in Fulda began immediately after his death; his grave was equipped with a decorative tomb around ten years after his burial, and the grave and relics became the center of the abbey. Fulda monks prayed for newly elected abbots at the grave site before greeting them, and every Monday the saint was remembered in prayer, the monks prostrating themselves and recitingPsalm 50

Psalm 50, a Psalm of Asaph, is the 50th psalm from the Book of Psalms in the Bible, beginning in English in the King James Version: "The mighty God, even the LORD, hath spoken, and called the earth from the rising of the sun unto the going down ...

. After the abbey church was rebuilt to become the Ratgar Basilica (dedicated 791), Boniface's remains were translated

Translation is the communication of the meaning of a source-language text by means of an equivalent target-language text. The English language draws a terminological distinction (which does not exist in every language) between ''transla ...

to a new grave: since the church had been enlarged, his grave, originally in the west, was now in the middle; his relics were moved to a new apse

In architecture, an apse (plural apses; from Latin 'arch, vault' from Ancient Greek 'arch'; sometimes written apsis, plural apsides) is a semicircular recess covered with a hemispherical vault or semi-dome, also known as an '' exedra''. ...

in 819. From then on Boniface, as patron

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, arts patronage refers to the support that kings, popes, and the wealthy have provided to artists su ...

of the abbey, was regarded as both spiritual intercessor for the monks and legal owner of the abbey and its possessions, and all donations to the abbey were done in his name. He was honored on the date of his martyrdom, 5 June (with a mass written by Alcuin

Alcuin of York (; la, Flaccus Albinus Alcuinus; 735 – 19 May 804) – also called Ealhwine, Alhwin, or Alchoin – was a scholar, clergyman, poet, and teacher from York, Northumbria. He was born around 735 and became the student o ...

), and (around the year 1000) with a mass dedicated to his appointment as bishop, on 1 December.

Dokkum

Willibald's describes how a visitor on horseback came to the site of the martyrdom, and a hoof of his horse got stuck in the mire. When it was pulled loose, a well sprang up. By the time of the (9th century), there was a church on the site, and the well had become a "fountain of sweet water" used to sanctify people. The , a hagiographical account of the work ofLudger

Ludger ( la, Ludgerus; also Lüdiger or Liudger) (born at Zuilen near Utrecht 742; died 26 March 809 at Billerbeck) was a missionary among the Frisians and Saxons, founder of Werden Abbey and the first Bishop of Münster in Westphalia. He has ...

, describes how Ludger himself had built the church, sharing duties with two other priests. According to James Palmer, the well was of great importance since the saint's body was hundreds of miles away; the physicality of the well allowed for an ongoing connection with the saint. In addition, Boniface signified Dokkum's and Frisia's "connect onto the rest of (Frankish) Christendom".

Memorials

Saint Boniface's feast day is celebrated on 5 June in the Roman

Saint Boniface's feast day is celebrated on 5 June in the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, the Lutheran Church

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

, the Anglican Communion

The Anglican Communion is the third largest Christian communion after the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches. Founded in 1867 in London, the communion has more than 85 million members within the Church of England and oth ...

and the Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, also called the Orthodox Church, is the second-largest Christian church, with approximately 220 million baptized members. It operates as a communion of autocephalous churches, each governed by its bishops vi ...

.

A famous statue of Saint Boniface stands on the grounds of Mainz Cathedral

, native_name_lang =

, image = Mainzer Dom nw.jpg

, imagesize =

, imagelink =

, imagealt =

, caption =

, pushpin map =

, pushpin label position =

, pushpin map alt =

, pushpin mapsize =

, relief =

, map caption =

, iso regi ...

, seat of the archbishop of Mainz

The Elector of Mainz was one of the seven Prince-electors of the Holy Roman Empire. As both the Archbishop of Mainz and the ruling prince of the Electorate of Mainz, the Elector of Mainz held a powerful position during the Middle Ages. The Archb ...

. A more modern rendition stands facing St. Peter's Church of Fritzlar.

The UK National Shrine is located at the Catholic church at Crediton

Crediton is a town and civil parish in the Mid Devon district of Devon in England. It stands on the A377 Exeter to Barnstaple road at the junction with the A3072 road to Tiverton, about north west of Exeter and around from the M5 motorwa ...

, Devon, which has a bas-relief

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces are bonded to a solid background of the same material. The term '' relief'' is from the Latin verb ''relevo'', to raise. To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that th ...

of the felling of Thor's Oak, by sculptor Kenneth Carter. The sculpture was unveiled by Princess Margaret

Princess Margaret, Countess of Snowdon, (Margaret Rose; 21 August 1930 – 9 February 2002) was the younger daughter of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, and the younger sister and only sibling of Queen Elizabeth ...

in his native Crediton

Crediton is a town and civil parish in the Mid Devon district of Devon in England. It stands on the A377 Exeter to Barnstaple road at the junction with the A3072 road to Tiverton, about north west of Exeter and around from the M5 motorwa ...

, located in Newcombes Meadow Park. There is also a series of paintings there by Timothy Moore. There are quite a few churches dedicated to St. Boniface in the United Kingdom: Bunbury, Cheshire; Chandler's Ford and Southampton

Southampton () is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire, S ...

Hampshire; Adler Street, London; Papa Westray

Papa Westray () ( sco, Papa Westree), also known as Papay, is one of the Orkney Islands in Scotland, United Kingdom. The fertile soilKeay, J. & Keay, J. (1994) ''Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland''. London. HarperCollins. has long been a draw ...

, Orkney; St Budeaux

St Budeaux is an area and ward in the north west of Plymouth in the English county of Devon.

Original settlement

The name St Budeaux comes from Saint Budoc, the Bishop of Dol (Brittany). Around 480, Budoc is said to have founded a settleme ...

, Plymouth (now demolished); Bonchurch

Bonchurch is a small village to the east of Ventnor, now largely connected to the latter by suburban development, on the southern part of the Isle of Wight, England. One of the oldest settlements on the Isle of Wight, it is situated on The Under ...

, Isle of Wight; Cullompton, Devon.

St Boniface Down, the highest point in the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a Counties of England, county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the List of islands of England#Largest islands, largest and List of islands of England#Mo ...

, is named after him.

Bishop George Errington founded St Boniface's Catholic College

St Boniface's Catholic College is a secondary school for boys, under the direction and trustees of the Roman Catholic Community in the Plymouth area in the South West of England. Founded in 1856 as an independent boarding and day school for "you ...

, Plymouth in 1856. The school celebrates Saint Boniface on 5 June each year.

In 1818, Father Norbert Provencher

Joseph-Norbert Provencher (February 12, 1787 – June 7, 1853) was a Canadian clergyman and missionary and one of the founders of the modern province of Manitoba. He was the first Bishop of Saint Boniface and was an important figure in the histo ...

founded a mission on the east bank of the Red River in what was then Rupert's Land

Rupert's Land (french: Terre de Rupert), or Prince Rupert's Land (french: Terre du Prince Rupert, link=no), was a territory in British North America which comprised the Hudson Bay drainage basin; this was further extended from Rupert's Land ...

, building a log church and naming it after St. Boniface. The log church was consecrated as Saint Boniface Cathedral

Saint Boniface Cathedral (french: Cathédrale Saint-Boniface) is a Roman Catholic cathedral of Saint Boniface, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. It is an important building in Winnipeg, and is the principal church in the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Sai ...

after Provencher was himself consecrated as a bishop and the diocese

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associat ...

was formed. The community that grew around the cathedral eventually became the city of Saint Boniface

Boniface, OSB ( la, Bonifatius; 675 – 5 June 754) was an English Benedictine monk and leading figure in the Anglo-Saxon mission to the Germanic parts of the Frankish Empire during the eighth century. He organised significant foundations o ...

, which merged into the city of Winnipeg

Winnipeg () is the capital and largest city of the province of Manitoba in Canada. It is centred on the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine rivers, near the longitudinal centre of North America. , Winnipeg had a city population of 749 ...

in 1971. In 1844, four Grey Nuns

The Sisters of Charity of Montreal, formerly called The Sisters of Charity of the Hôpital Général of Montreal and more commonly known as the Grey Nuns of Montreal, is a Canadian religious institute of Roman Catholic religious sisters, founde ...

arrived by canoe in Manitoba, and in 1871, built Western Canada's first hospital: St. Boniface Hospital

Saint Boniface Hospital (french: Hôpital Saint-Boniface; also called St. B; previously called the Saint-Boniface General Hospital) is Manitoba's second-largest hospital, located in the Saint Boniface neighbourhood of Winnipeg. Founded by the Si ...

, where the Assiniboine and Red Rivers meet. Today, St. Boniface is regarded as Winnipeg's main French-speaking district and the centre of the Franco-Manitobain

Franco-Manitobans (french: Franco-Manitobains) are French Canadians or Canadian francophones living in the province of Manitoba. According to the 2016 Canadian Census, 40,975 residents of the province stated that French was their mother tongue. I ...

community, and St. Boniface Hospital is the second-largest hospital in Manitoba.

Boniface (Wynfrith) of Crediton

Crediton is a town and civil parish in the Mid Devon district of Devon in England. It stands on the A377 Exeter to Barnstaple road at the junction with the A3072 road to Tiverton, about north west of Exeter and around from the M5 motorwa ...

is remembered in the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

with a Lesser Festival Lesser Festivals are a type of observance in the Anglican Communion, including the Church of England, considered to be less significant than a Principal Feast, Principal Holy Day, or Festival, but more significant than a Commemoration. Whereas Pr ...

on 1 June

Events Pre-1600

*1215 – Zhongdu (now Beijing), then under the control of the Jurchen ruler Emperor Xuanzong of Jin, is captured by the Mongols under Genghis Khan, ending the Battle of Zhongdu.

*1252 – Alfonso X is proclaimed king o ...

.

Legends

Some traditions credit Saint Boniface with the invention of theChristmas tree

A Christmas tree is a decorated tree, usually an evergreen conifer, such as a spruce, pine or fir, or an artificial tree of similar appearance, associated with the celebration of Christmas. The custom was further developed in early modern G ...

. It is mentioned on a BBC-Devon website, in an account which places Geismar in Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total l ...

, and in a number of educational books, including ''St. Boniface and the Little Fir Tree'', ''The Brightest Star of All: Christmas Stories for the Family'', ''The American normal readers'', and a short story by Henry van Dyke, "The First Christmas Tree".

Sources and writings

The earliest "Life" of Boniface was written by a certain Willibald, an Anglo-Saxon priest who came to

Mainz

Mainz () is the capital and largest city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Mainz is on the left bank of the Rhine, opposite to the place that the Main joins the Rhine. Downstream of the confluence, the Rhine flows to the north-west, with Ma ...

after Boniface's death, around 765. Willibald's biography was widely dispersed; Levison lists some forty manuscripts. According to his lemma, a group of four manuscripts including 1086 are copies directly from the original.

Listed second in Levison's edition is the entry from a late ninth-century Fulda document: Boniface's status as a martyr is attested by his inclusion in the ''Fulda Martyrology'' which also lists, for instance, the date (1 November) of his translation

Translation is the communication of the Meaning (linguistic), meaning of a #Source and target languages, source-language text by means of an Dynamic and formal equivalence, equivalent #Source and target languages, target-language text. The ...

in 819, when the Fulda Cathedral had been rebuilt. A was written in Fulda in the ninth century, possibly by Candidus of Fulda Candidus (Bruun) of Fulda was a Benedictine scholar of the ninth-century Carolingian Renaissance, a student of Einhard, and author of the ''vita'' of his abbot at Fulda, Eigil.

Biography

He received his first instruction from the learned Eigil, ...

, but is now lost.

The next , chronologically, is the , which originates in the Bishopric of Utrecht

The Bishopric of Utrecht ( nl, Sticht Utrecht) was an ecclesiastical principality of the Holy Roman Empire in the Low Countries, in the present-day Netherlands. From 1024 to 1528, as one of the prince-bishoprics of the Holy Roman Empire, it ...

, and was probably revised by Radboud of Utrecht

Saint Radbod (or Radboud) (before 850 – 917) was bishop of Utrecht from 899 to 917.

Life

Radboud was born around the middle of the 9th century from a noble Frankish family near Namur. His mother was of Frisian origin and a descendant of the ...

(899–917). Mainly agreeing with Willibald, it adds an eye-witness who presumably saw the martyrdom at Dokkum. The likewise originates in Utrecht. It is dated between 917 (Radboud's death) and 1075, the year Adam of Bremen

Adam of Bremen ( la, Adamus Bremensis; german: Adam von Bremen) (before 1050 – 12 October 1081/1085) was a German medieval chronicler. He lived and worked in the second half of the eleventh century. Adam is most famous for his chronicle '' Ges ...

wrote his , which used the .

A later , written by Otloh of St. Emmeram (1062–1066), is based on Willibald's and a number of other as well as the correspondence, and also includes information from local traditions.

Correspondence

Boniface engaged in regular correspondence with fellow churchmen all over Western Europe, including the three popes he worked with, and with some of his kinsmen back in England. Many of these letters contain questions about church reform and liturgical or doctrinal matters. In most cases, what remains is one half of the conversation, either the question or the answer. The correspondence as a whole gives evidence of Boniface's widespread connections; some of the letters also prove an intimate relationship especially with female correspondents.Noble xxxiv–xxxv. There are 150 letters in what is generally called the Bonifatian correspondence, though not all them are by Boniface or addressed to him. They were assembled by order of archbishopLullus

Saint Lullus (Lull or Lul) (born about 710 AD in Wessex, died 16 October 786 in Hersfeld) was the first permanent archbishop of Mainz, succeeding Saint Boniface, and first abbot of the Benedictine Hersfeld Abbey. He is historiographically conside ...

, Boniface's successor in Mainz, and were initially organized into two parts, a section containing the papal correspondence and another with his private letters. They were reorganized in the eighth century, in a roughly chronological ordering. Otloh of St. Emmeram, who worked on a new of Boniface in the eleventh century, is credited with compiling the complete correspondence as we have it. Much of this correspondence comprises the first part of the Vienna Boniface Codex, also known as .

The correspondence was edited and published already in the seventeenth century, by Nicolaus Serarius. Stephan Alexander Würdtwein's 1789 edition, , was the basis for a number of (partial) translations in the nineteenth century. The first version to be published by (MGH) was the edition by Ernst Dümmler (1892); the most authoritative version until today is Michael Tangl's 1912 , published by MGH in 1916. This edition is the basis of Ephraim Emerton's selection and translation in English, ''The Letters of Saint Boniface'', first published in New York in 1940; it was republished most recently with a new introduction by Thomas F.X. Noble in 2000.

Included among his letters and dated to 716 is one to Abbess Edburga of Minster-in-Thanet containing the ''Vision of the Monk of Wenlock Wenlock may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Little Wenlock, a village in Shropshire

* Much Wenlock, a town in Shropshire

** (Much) Wenlock (UK Parliament constituency)

** Wenlock Priory, a 7th/12th-century monastery

* Wenlock Basin, a canal basi ...

''. This otherworld vision describes how a violently ill monk is freed from his body and guided by angels to a place of judgment, where angels and devils fight over his soul as his sins and virtues come alive to accuse and defend him. He sees a hell of purgation full of pits vomiting flames. There is a bridge over a pitch-black boiling river. Souls either fall from it or safely reach the other side cleansed of their sins. This monk even sees some of his contemporary monks and is told to warn them to repent before they die. This vision bears signs of influence by the Apocalypse of Paul, the visions from the ''Dialogues'' of Gregory the Great

Pope Gregory I ( la, Gregorius I; – 12 March 604), commonly known as Saint Gregory the Great, was the bishop of Rome from 3 September 590 to his death. He is known for instigating the first recorded large-scale mission from Rome, the Gregori ...

, and the visions recorded by Bede

Bede ( ; ang, Bǣda , ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, The Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable ( la, Beda Venerabilis), was an English monk at the monastery of St Peter and its companion monastery of St Paul in the Kingdom ...

.

Sermons

Some fifteen preserved sermons are traditionally associated with Boniface, but that they were actually his is not generally accepted.Grammar and poetry

Early in his career, before he left for the continent, Boniface wrote the , a grammatical treatise presumably for his students in Nursling. Helmut Gneuss reports that one manuscript copy of the treatise originates from (the south of) England, mid-eighth century; it is now held inMarburg

Marburg ( or ) is a university town in the German federal state (''Bundesland'') of Hesse, capital of the Marburg-Biedenkopf district (''Landkreis''). The town area spreads along the valley of the river Lahn and has a population of approx ...

, in the Hessisches Staatsarchiv. He also wrote a treatise on verse, the , and a collection of twenty acrostic riddle

A riddle is a statement, question or phrase having a double or veiled meaning, put forth as a puzzle to be solved. Riddles are of two types: ''enigmas'', which are problems generally expressed in metaphorical or allegorical language that requi ...

s, the , influenced greatly by Aldhelm

Aldhelm ( ang, Ealdhelm, la, Aldhelmus Malmesberiensis) (c. 63925 May 709), Abbot of Malmesbury Abbey, Bishop of Sherborne, and a writer and scholar of Latin poetry, was born before the middle of the 7th century. He is said to have been the ...

and containing many references to works of Vergil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: the ...

(the ''Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; la, Aenē̆is or ) is a Latin Epic poetry, epic poem, written by Virgil between 29 and 19 BC, that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Troy, Trojan who fled the Trojan_War#Sack_of_Troy, fall of Troy and travelled to ...

'', the ''Georgics

The ''Georgics'' ( ; ) is a poem by Latin poet Virgil, likely published in 29 BCE. As the name suggests (from the Greek word , ''geōrgika'', i.e. "agricultural (things)") the subject of the poem is agriculture; but far from being an example ...

'', and the ''Eclogues

The ''Eclogues'' (; ), also called the ''Bucolics'', is the first of the three major works of the Latin poet Virgil.

Background

Taking as his generic model the Greek bucolic poetry of Theocritus, Virgil created a Roman version partly by offer ...

''). The riddles fall into two sequences of ten poems. The first, ('on the virtues'), comprises: 1. /truth; 2. /the Catholic faith; 3. /hope; 4. /compassion; 5. /love; 6. /justice; 7. /patience; 8. /true, Christian peace; 9. /Christian humility; 10. /virginity. The second sequence, ('on the vices'), comprises: 1. /carelessness; 2. /hot temper; 3. /greed; 4. /pride; 5. /intemperance; 6. /drunkenness; 7. /fornication; 8. /envy; 9. /ignorance; 10. /vainglory.

Three octosyllabic poems written in clearly Aldhelmian fashion (according to Andy Orchard

Andrew Philip McDowell Orchard (born 27 February 1964) is a scholar and teacher of Old English, Norse and Celtic literature. He is Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon at the University of Oxford and a Fellow#Oxford.2C Cambridge and ...

) are preserved in his correspondence, all composed before he left for the continent.

Additional materials

A letter by Boniface charging Aldebert and Clement with heresy is preserved in the records of the Roman Council of 745 that condemned the two. Boniface had an interest in the Irish canon law collection known as , and a late eighth/early ninth-century manuscript inWürzburg

Würzburg (; Main-Franconian: ) is a city in the region of Franconia in the north of the German state of Bavaria. Würzburg is the administrative seat of the '' Regierungsbezirk'' Lower Franconia. It spans the banks of the Main River.

Würzbur ...

contains, besides a selection from the , a list of rubrics that mention the heresies of Clemens and Aldebert. The relevant folios containing these rubrics were most likely copied in Mainz, Würzburg, or Fulda—all places associated with Boniface. Michael Glatthaar Michael Glatthaar (born 3 May 1953) is a German scholar of the Middle Ages, specializing in the documents of the Carolingians and the study of Saint Boniface. A student of Hubert Mordek, he is the author of ''Bonifatius und das Sakrileg'' (2004), ...

suggested that the rubrics should be seen as Boniface's contribution to the agenda for a synod.

Anniversary and other celebrations

Boniface's death (and birth) has given rise to a number of noteworthy celebrations. The dates for some of these celebrations have undergone some changes: in 1805, 1855, and 1905 (and in England in 1955) anniversaries were calculated with Boniface's death dated in 755, according to the "Mainz tradition"; in Mainz, Michael Tangl's dating of the martyrdom in 754 was not accepted until after 1955. Celebrations in Germany centered on Fulda and Mainz, in the Netherlands on Dokkum and Utrecht, and in England on Crediton and Exeter.Celebrations in Germany: 1805, 1855, 1905

The first German celebration on a fairly large scale was held in 1805 (the 1,050th anniversary of his death), followed by a similar celebration in a number of towns in 1855; both of these were predominantly Catholic affairs emphasizing the role of Boniface in German history. But if the celebrations were mostly Catholic, in the first part of the 19th century the respect for Boniface in general was an ecumenical affair, with both Protestants and Catholics praising Boniface as a founder of the German nation, in response to the German nationalism that arose after the Napoleonic era came to an end. The second part of the 19th century saw increased tension between Catholics and Protestants; for the latter,

The first German celebration on a fairly large scale was held in 1805 (the 1,050th anniversary of his death), followed by a similar celebration in a number of towns in 1855; both of these were predominantly Catholic affairs emphasizing the role of Boniface in German history. But if the celebrations were mostly Catholic, in the first part of the 19th century the respect for Boniface in general was an ecumenical affair, with both Protestants and Catholics praising Boniface as a founder of the German nation, in response to the German nationalism that arose after the Napoleonic era came to an end. The second part of the 19th century saw increased tension between Catholics and Protestants; for the latter, Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Luther ...

had become the model German, the founder of the modern nation, and he and Boniface were in direct competition for the honor. In 1905, when strife between Catholic and Protestant factions had eased (one Protestant church published a celebratory pamphlet, Gerhard Ficker's ), there were modest celebrations and a publication for the occasion on historical aspects of Boniface and his work, the 1905 by Gregor Richter and Carl Scherer. In all, the content of these early celebrations showed evidence of the continuing question about the meaning of Boniface for Germany, though the importance of Boniface in cities associated with him was without question.

1954 celebrations

In 1954, celebrations were widespread in England, Germany, and the Netherlands, and a number of these celebrations were international affairs. Especially in Germany, these celebrations had a distinctly political note to them and often stressed Boniface as a kind of founder of Europe, such as whenKonrad Adenauer

Konrad Hermann Joseph Adenauer (; 5 January 1876 – 19 April 1967) was a Germany, German statesman who served as the first Chancellor of Germany, chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany from 1949 to 1963. From 1946 to 1966, he was the fir ...

, the (Catholic) German chancellor, addressed a crowd of 60,000 in Fulda, celebrating the feast day of the saint in a European context: ("What we have in common in Europe comes from the same source").

1980 papal visit

WhenPope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II ( la, Ioannes Paulus II; it, Giovanni Paolo II; pl, Jan Paweł II; born Karol Józef Wojtyła ; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 1978 until his ...

visited Germany in November 1980, he spent two days in Fulda (17 and 18 November). He celebrated Mass in Fulda Cathedral with 30,000 gathered on the square in front of the building, and met with the German Bishops' Conference (held in Fulda since 1867). The pope next celebrated mass outside the cathedral, in front of an estimated crowd of 100,000, and hailed the importance of Boniface for German Christianity: ("The holy Boniface, bishop and martyr, 'signifies' the beginning of the gospel and the church in your country"). A photograph of the pope praying at Boniface's grave became the centerpiece of a prayer card distributed from the cathedral.

2004 celebrations

In 2004, anniversary celebrations were held throughout Northwestern Germany and Utrecht, and Fulda and Mainz—generating a great amount of academic and popular interest. The event occasioned a number of scholarly studies, esp. biographies (for instance, by Auke Jelsma in Dutch, Lutz von Padberg in German, and Klaas Bruinsma in Frisian), and a fictional completion of the Boniface correspondence (Lutterbach, ). A German musical proved a great commercial success, and in the Netherlands an opera was staged.Scholarship on Boniface

There is an extensive body of literature on the saint and his work. At the time of the various anniversaries, edited collections were published containing essays by some of the best-known scholars of the time, such as the 1954 collection and the 2004 collection . In the modern era, Lutz von Padberg published a number of biographies and articles on the saint focusing on his missionary praxis and his relics. The most authoritative biography remains Theodor Schieffer's (1954).See also

*List of Catholic saints

This is an incomplete list of people and angels whom the Catholic Church has canonized as saints. According to Catholic theology, all saints enjoy the beatific vision. Many of the saints listed here are to be found in the General Roman Calend ...

* Religion in Germany

* Saint Boniface, patron saint archive

*St Boniface's Catholic College

St Boniface's Catholic College is a secondary school for boys, under the direction and trustees of the Roman Catholic Community in the Plymouth area in the South West of England. Founded in 1856 as an independent boarding and day school for "you ...

, Plymouth, England

References

Notes

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *"St. Boniface"

entry from online version of the ''Catholic Encyclopedia'', 1913 edition. * *Talbot, C. H., ed. ''The Anglo-Saxon Missionaries in Germany: Being the Lives of S.S. Willibrord, Boniface, Strum, Leoba and Lebuin, together with the Hodoeporicon of St. Willibald and a Selection from the Correspondence of St. Boniface''. New York: Sheed and Ward, 1954. **The Bonifacian ''vita'' was republished in Noble, Thomas F. X. and Thomas Head, eds. ''Soldiers of Christ: Saints and Saints' Lives in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages''. University Park: Pennsylvania State UP, 1995. 109–40. * * *

External links

''Butler's Lives of the Saints''

Wilhelm Levison, ''Vitae Sancti Bonifatii''

{{DEFAULTSORT:Boniface 7th-century births 754 deaths 8th-century Christian theologians Anglo-Saxon saints Archbishops of Mainz Christmas trees Diplomats of the Holy See German folklore Medieval German saints History of Catholicism in Germany Medieval legends People from Crediton West Saxon saints Burials at Fulda Cathedral 8th-century bishops 8th-century Frankish saints 8th-century Frankish writers 8th-century English writers 8th-century poets 8th-century Latin writers Roman Catholic bishops in Germany Anglican saints English Roman Catholic saints English Roman Catholics