Spiritualist Movement on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Spiritualism is the

Spiritualism is the

Image:Emanuel Swedenborg, 1688-1772, ämbetsman (Per Krafft d.ä.) - Nationalmuseum - 15710.tif,

Spiritualists often set March 31, 1848, as the beginning of their movement. On that date, Kate and Margaret Fox, of Hydesville, New York, reported that they had made contact with a spirit that was later claimed to be the spirit of a murdered peddler whose body was found in the house, though no record of such a person was ever found. The spirit was said to have communicated through rapping noises, audible to onlookers. The evidence of the senses appealed to practically minded Americans, and the Fox sisters became a sensation. As the first celebrity mediums, the sisters quickly became famous for their public séances in New York. However, in 1888 the Fox sisters admitted that this "contact" with the spirit was a hoax, though shortly afterward they recanted that admission.

Spiritualists often set March 31, 1848, as the beginning of their movement. On that date, Kate and Margaret Fox, of Hydesville, New York, reported that they had made contact with a spirit that was later claimed to be the spirit of a murdered peddler whose body was found in the house, though no record of such a person was ever found. The spirit was said to have communicated through rapping noises, audible to onlookers. The evidence of the senses appealed to practically minded Americans, and the Fox sisters became a sensation. As the first celebrity mediums, the sisters quickly became famous for their public séances in New York. However, in 1888 the Fox sisters admitted that this "contact" with the spirit was a hoax, though shortly afterward they recanted that admission.

Consequently, many early participants in Spiritualism were radical Quakers and others involved in the mid-nineteenth-century

Consequently, many early participants in Spiritualism were radical Quakers and others involved in the mid-nineteenth-century

''The History of Spiritualism Vol I''

Arthur Conan Doyle, 1926. In addition, the movement appealed to reformers, who fortuitously found that the spirits favoured such causes ''du jour'' as abolition of slavery, and equal rights for women. It also appealed to some who had a

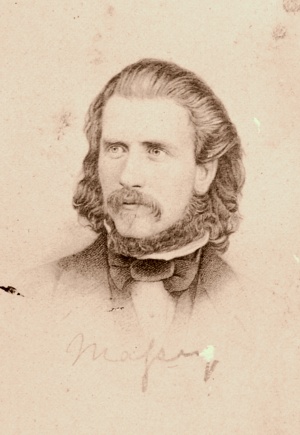

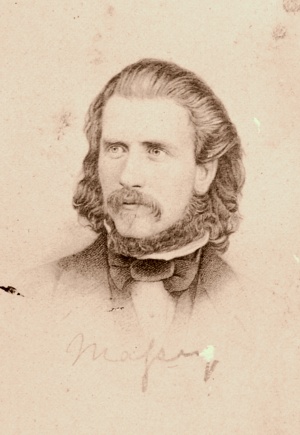

Image:Frank Podmore.jpg,

A number of scientists who investigated the phenomenon also became converts. They included chemist and physicist  The psychical researcher

The psychical researcher

Spiritualism was mainly a middle- and upper-class movement, and especially popular with women. American Spiritualists would meet in private homes for séances, at lecture halls for trance lectures, at state or national conventions, and at summer camps attended by thousands. Among the most significant of the camp meetings were Camp Etna, in

Spiritualism was mainly a middle- and upper-class movement, and especially popular with women. American Spiritualists would meet in private homes for séances, at lecture halls for trance lectures, at state or national conventions, and at summer camps attended by thousands. Among the most significant of the camp meetings were Camp Etna, in

London-born

London-born  The American voice medium

The American voice medium

The Spiritualist

The Spiritualist

Formal education in spiritualist practice emerged in 1920s, with organizations like the William T. Stead Center in Chicago, Illinois, and continue today with the

Formal education in spiritualist practice emerged in 1920s, with organizations like the William T. Stead Center in Chicago, Illinois, and continue today with the

Supernatural Entertainments: Victorian Spiritualism and the Rise of Modern Media Culture

'. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. . * Podmore, Frank, ''Mediums of the 19th Century'', 2 vols., University Books, 1963. * Salter, William H., ''Zoar; or the Evidence of Psychical Research Concerning Survival'', Sidgwick, 1961. * Strube, Julian (2016).

Socialist Religion and the Emergence of Occultism: A Genealogical Approach to Socialism and Secularization in 19th-Century France

" ''Religion''. . * Strube, Julian (2016).

Sozialismus, Katholizisimus und Okkultismus im Frankreich des 19. Jahrhunderts

'' Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter. . * ''Telegrams from the Dead'' (a

The question: "If a man die, shall he live again?" a brief history and examination of modern spiritualism

''The Question: A Brief History and Examination of Modern Spiritualism]''. Grant Richards, London. * Arthur Conan Doyle, Doyle, Arthur Conan (1975) The History of Spiritualism. Arno Press. New York. * * Kurtz, Paul (1985). "Spiritualists, Mediums and Psychics: Some Evidence of Fraud". In Paul Kurtz (ed.). ''A Skeptic's Handbook of Parapsychology''. Prometheus Books. pp. 177–223. . * * Mann, Walter (1919)

''The Follies and Frauds of Spiritualism''

Rationalist Association. London: Watts & Co. * McCabe, Joseph. (1920)

''Is Spiritualism Based on Fraud? The Evidence Given by Sir A. C. Doyle and Others Drastically Examined''

London: Watts & Co. * Mercier, Charles Arthur (1917)

''Spiritualism and Sir Oliver Lodge''

London: Mental Culture Enterprise. * * Podmore, Frank (1911)

The newer spiritualism

''The Newer Spiritualism]''. Henry Holt and Company. * Harry Price, Price, Harry; Dingwall, Eric (1975)

''Revelations of a Spirit Medium''

Arno Press. Reprint of 1891 edition by Charles F. Pidgeon. This rare, overlooked, and forgotten, book gives the "insider's knowledge" of 19th century deceptions. * Richet, Charles (1924). Thirty Years of Psychical Research being a Treatise on Metaphysics. The Macmillan Company. New York. . * Rinn, Joseph (1950). ''Sixty Years Of Psychical Research: Houdini and I Among the Spiritualists''. Truth Seeker. * Sera-Shriar, Efram (2022). Psychic Investigators Anthropology, Modern Spiritualism, and Credible Witnessing in the Late Victorian Age. University of Pittsburgh Press. Pittsburgh. .

"American Spirit: A History of the Supernatural"

n hour-long history public radio program exploring American spiritualism.

Open Directory Project page for "Spiritualism"

Video and Images of the original Fox Family historic home site.

"Investigating Spirit Communications"

oe Nickell

"Spiritualism Exposed: Margaret Fox Kane Confesses Fraud"

keptic Report {{Authority control New religious movements Religious belief systems founded in the United States

Spiritualism is the

Spiritualism is the metaphysical

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

school of thought opposing physicalism

In philosophy, physicalism is the metaphysical thesis that "everything is physical", that there is "nothing over and above" the physical, or that everything supervenes on the physical. Physicalism is a form of ontological monism—a "one substanc ...

and also is the category of all spiritual beliefs/views (in monism

Monism attributes oneness or singleness (Greek: μόνος) to a concept e.g., existence. Various kinds of monism can be distinguished:

* Priority monism states that all existing things go back to a source that is distinct from them; e.g., i ...

and dualism) from ancient to modern. In the long nineteenth century

The ''long nineteenth century'' is a term for the 125-year period beginning with the onset of the French Revolution in 1789 and ending with the outbreak of World War I in 1914. It was coined by Russian writer Ilya Ehrenburg and British Marxist his ...

, Spiritualism (when not lowercase) became most known as a social religious

Religion is usually defined as a social system, social-cultural system of designated religious behaviour, behaviors and practices, morality, morals, beliefs, worldviews, religious text, texts, sacred site, sanctified places, prophecy, prophecie ...

movement

Movement may refer to:

Common uses

* Movement (clockwork), the internal mechanism of a timepiece

* Motion, commonly referred to as movement

Arts, entertainment, and media

Literature

* "Movement" (short story), a short story by Nancy Fu ...

according to which the laws of nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physics, physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomenon, phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. ...

and of God

In monotheism, monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator deity, creator, and principal object of Faith#Religious views, faith.Richard Swinburne, Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Ted Honderich, Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Ox ...

include "the continuity of consciousness

Consciousness, at its simplest, is sentience and awareness of internal and external existence. However, the lack of definitions has led to millennia of analyses, explanations and debates by philosophers, theologians, linguisticians, and scien ...

after the transition of death

Death is the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain an organism. For organisms with a brain, death can also be defined as the irreversible cessation of functioning of the whole brain, including brainstem, and brain ...

" and "the possibility of communication between those living on Earth and those who have made the transition". The afterlife

The afterlife (also referred to as life after death) is a purported existence in which the essential part of an individual's identity or their stream of consciousness continues to live after the death of their physical body. The surviving ess ...

, or the " spirit world", is seen by spiritualists not as a static place, but as one in which spirits continue to evolve. These two beliefs—that contact with spirits is possible, and that spirits are more advanced than humans—lead spiritualists to a third belief: that spirits are capable of providing useful insight regarding moral

A moral (from Latin ''morālis'') is a message that is conveyed or a lesson to be learned from a story or event. The moral may be left to the hearer, reader, or viewer to determine for themselves, or may be explicitly encapsulated in a maxim. A ...

and ethical issues

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior".''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concerns ma ...

, as well as about the nature of God

In monotheism, monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator deity, creator, and principal object of Faith#Religious views, faith.Richard Swinburne, Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Ted Honderich, Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Ox ...

. Some spiritualists will speak of a concept which they refer to as "spirit guide

A spirit guide, in Western spiritualism, is an entity that remains as a discarnate spirit to act as a guide or protector to a living incarnation, incarnated human being.

Description

In traditional African belief systems, well before the spre ...

s"—specific spirits, often contacted, who are relied upon for spiritual guidance. Emanuel Swedenborg

Emanuel Swedenborg (, ; born Emanuel Swedberg; 29 March 1772) was a Swedish pluralistic-Christian theologian, scientist, philosopher and mystic. He became best known for his book on the afterlife, ''Heaven and Hell'' (1758).

Swedenborg had ...

has some claim to be the father of Spiritualism. Spiritism

Spiritism (French: ''spiritisme''; Portuguese: ''espiritismo'') is a spiritualist, religious, and philosophical doctrine established in France in the 1850s by the French teacher, educational writer, and translator Hippolyte Léon Denizard Riva ...

, a branch of spiritualism developed by Allan Kardec

Allan Kardec () is the pen name of the French educator, translator, and author Hippolyte Léon Denizard Rivail (; 3 October 1804 – 31 March 1869). He is the author of the five books known as the Spiritist Codification, and the founder of S ...

and today practiced mostly in Continental Europe

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous continent of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, – which can conversely mean the whole of Europe – and, by ...

and Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived f ...

, especially in Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

, emphasizes reincarnation

Reincarnation, also known as rebirth or transmigration, is the philosophical or religious concept that the non-physical essence of a living being begins a new life in a different physical form or body after biological death. Resurrection is a ...

.

Spiritualism developed and reached its peak growth in membership from the 1840s to the 1920s, especially in English-speaking countries

The following is a list of English-speaking population by country, including information on both native speakers and second-language speakers.

List

* The European Union is a supranational union composed of 27 member states. The total Engl ...

. By 1897, spiritualism was said to have more than eight million followers in the United States and Europe, mostly drawn from the middle and upper class

Upper class in modern societies is the social class composed of people who hold the highest social status, usually are the wealthiest members of class society, and wield the greatest political power. According to this view, the upper class is gen ...

es.

Spiritualism flourished for a half century without canonical texts or formal organization, attaining cohesion through periodicals, tours by trance lecturers, camp meetings, and the missionary activities of accomplished mediums. Many prominent spiritualists were women, and like most spiritualists, supported causes such as the abolition of slavery

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

and women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

. By the late 1880s the credibility of the informal movement had weakened due to accusations of fraud perpetrated by mediums, and formal spiritualist organizations began to appear. Spiritualism is currently practiced primarily through various denominational spiritualist church

A spiritualist church is a church affiliated with the informal spiritualist movement which began in the United States in the 1840s. Spiritualist churches are now found around the world, but are most common in English-speaking countries, while in L ...

es in the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom.

Beliefs

Spiritualism and its belief system became protected characteristics under Law in the U.K. in 2009 by Alan Power at the UKEAT (Appeal Court,) London, England.Mediumship and spirits

Spiritualists believe in the possibility of communication with the spirits of dead people, whom they regard as "discarnate humans". They believe that spirit mediums are gifted to carry on such communication, but that anyone may become a medium through study and practice. They believe that spirits are capable of growth and perfection, progressing through higher spheres or planes, and that theafterlife

The afterlife (also referred to as life after death) is a purported existence in which the essential part of an individual's identity or their stream of consciousness continues to live after the death of their physical body. The surviving ess ...

is not a static state, but one in which spirits evolve. The two beliefs—that contact with spirits is possible, and that spirits may dwell on a higher plane—lead to a third belief, that spirits can provide knowledge about moral and ethical issues, as well as about God

In monotheism, monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator deity, creator, and principal object of Faith#Religious views, faith.Richard Swinburne, Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Ted Honderich, Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Ox ...

and the afterlife. Many believers therefore speak of "spirit guides

A spirit guide, in Western spiritualism, is an entity that remains as a discarnate spirit to act as a guide or protector to a living incarnated human being.

Description

In traditional African belief systems, well before the spread of Christ ...

"—specific spirits, often contacted, and relied upon for worldly and spiritual guidance.

According to Spiritualists, anyone may receive spirit messages, but formal communication sessions (séances) are held by mediums, who claim thereby to receive information about the afterlife.

Religious views

Declaration of Principles

As an informal movement, Spiritualism does not have a defined set of rules, but various Spiritualist organizations within the United States have adopted variations on some or all of a "Declaration of Principles" developed between 1899 and 1944 and revised as recently as 2004. In October 1899, a six article "Declaration of Principles" was adopted by theNational Spiritualist Association

The National Spiritualist Association of Churches (NSAC) is one of the oldest and largest of the national Spiritualist church organizations in the United States. The NSAC was formed as the National Spiritualist Association of the United States ...

(NSA) at a convention in Chicago, Illinois. An additional two principles were added by the NSA in October 1909, at a convention in Rochester, New York. Finally, in October 1944, a ninth principle was adopted by the National Spiritualist Association of Churches, at a convention in St. Louis, Missouri.

In the UK, the main organization representing Spiritualism is the Spiritualists' National Union (SNU), whose teachings are based on the Seven Principles.

Origins

Spiritualism first appeared in the 1840s in the "Burned-over District

The term "burned-over district" refers to the western and central regions of New York State in the early 19th century, where religious revivals and the formation of new religious movements of the Second Great Awakening took place, to such a ...

" of upstate New York

Upstate New York is a geographic region consisting of the area of New York State that lies north and northwest of the New York City metropolitan area. Although the precise boundary is debated, Upstate New York excludes New York City and Long Is ...

, where earlier religious movements such as Millerism

The Millerites were the followers of the teachings of William Miller, who in 1831 first shared publicly his belief that the Second Advent of Jesus Christ would occur in roughly the year 1843–1844. Coming during the Second Great Awakening, his ...

and Mormonism

Mormonism is the religious tradition and theology of the Latter Day Saint movement of Restorationist Christianity started by Joseph Smith in Western New York in the 1820s and 1830s. As a label, Mormonism has been applied to various aspects of t ...

had emerged during the Second Great Awakening

The Second Great Awakening was a Protestant religious revival during the early 19th century in the United States. The Second Great Awakening, which spread religion through revivals and emotional preaching, sparked a number of reform movements. R ...

, although Millerism and Mormonism did not associate themselves with Spiritualism.

This region of New York State was an environment in which many thought direct communication with God or angels was possible, and that God would not behave harshly—for example, that God would not condemn unbaptised infants to an eternity in Hell.

Swedenborg and Mesmer

In this environment, the writings ofEmanuel Swedenborg

Emanuel Swedenborg (, ; born Emanuel Swedberg; 29 March 1772) was a Swedish pluralistic-Christian theologian, scientist, philosopher and mystic. He became best known for his book on the afterlife, ''Heaven and Hell'' (1758).

Swedenborg had ...

(1688–1772) and the teachings of Franz Mesmer

Franz Anton Mesmer (; ; 23 May 1734 – 5 March 1815) was a German physician with an interest in astronomy. He theorised the existence of a natural energy transference occurring between all animated and inanimate objects; this he called " ani ...

(1734–1815) provided an example for those seeking direct personal knowledge of the afterlife. Swedenborg, who claimed to communicate with spirits while awake, described the structure of the spirit world. Two features of his view particularly resonated with the early Spiritualists: first, that there is not a single Hell and a single Heaven, but rather a series of higher and lower heavens and hells; second, that spirits are intermediates between God and humans, so that the divine sometimes uses them as a means of communication. Although Swedenborg warned against seeking out spirit contact, his works seem to have inspired in others the desire to do so.

Swedenborg was formerly a highly regarded inventor and scientist, achieving several engineering innovations and studying physiology and anatomy. Then, “in 1741, he also began to have a series of intense mystical experiences, dreams, and visions, claiming that he had been called by God to reform Christianity and introduce a new church."

Mesmer did not contribute religious beliefs, but he brought a technique, later known as hypnotism

Hypnosis is a human condition involving focused attention (the selective attention/selective inattention hypothesis, SASI), reduced peripheral awareness, and an enhanced capacity to respond to suggestion.In 2015, the American Psychologica ...

, that it was claimed could induce trances and cause subjects to report contact with supernatural beings. There was a great deal of professional showmanship inherent to demonstrations of Mesmerism

Animal magnetism, also known as mesmerism, was a protoscientific theory developed by German doctor Franz Mesmer in the 18th century in relation to what he claimed to be an invisible natural force (''Lebensmagnetismus'') possessed by all livi ...

, and the practitioners who lectured in mid-19th-century North America sought to entertain their audiences as well as to demonstrate methods for personal contact with the divine.

Perhaps the best known of those who combined Swedenborg and Mesmer in a peculiarly North American synthesis was Andrew Jackson Davis

Andrew Jackson Davis (August 11, 1826January 13, 1910) was an American Spiritualist, born in Blooming Grove, New York.

Early years

Davis had little education. In 1843 he heard lectures in Poughkeepsie on animal magnetism, the precursor of hypn ...

, who called his system the "harmonial philosophy". Davis was a practising Mesmerist

Animal magnetism, also known as mesmerism, was a Protoscience#Prescientific protoscience, protoscientific theory developed by German doctor Franz Mesmer in the 18th century in relation to what he claimed to be an invisible natural force (''Le ...

, faith healer

Faith healing is the practice of prayer and gestures (such as laying on of hands) that are believed by some to elicit divine intervention in spiritual and physical healing, especially the Christian practice. Believers assert that the healing ...

and clairvoyant

Clairvoyance (; ) is the magical ability to gain information about an object, person, location, or physical event through extrasensory perception. Any person who is claimed to have such ability is said to be a clairvoyant () ("one who sees cl ...

from Blooming Grove, New York

Blooming Grove is a town in Orange County, New York, United States. The population was 18,811 at the 2020 census. It is located in the central part of the county, southwest of Newburgh.

History

Vincent Mathews was likely the earliest settler ...

. He was also strongly influenced by the socialist theories of Fourierism

Fourierism () is the systematic set of economic, political, and social beliefs first espoused by French intellectual Charles Fourier (1772–1837). Based upon a belief in the inevitability of communal associations of people who worked and lived to ...

. His 1847 book, ''The Principles of Nature, Her Divine Revelations, and a Voice to Mankind'', dictated to a friend while in a trance state, eventually became the nearest thing to a canonical work in a Spiritualist movement whose extreme individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote the exercise of one's goals and desires and to value independence and self-reli ...

precluded the development of a single coherent worldview.

Emanuel Swedenborg

Emanuel Swedenborg (, ; born Emanuel Swedberg; 29 March 1772) was a Swedish pluralistic-Christian theologian, scientist, philosopher and mystic. He became best known for his book on the afterlife, ''Heaven and Hell'' (1758).

Swedenborg had ...

Image:Franz Anton Mesmer.jpg, Franz Mesmer

Franz Anton Mesmer (; ; 23 May 1734 – 5 March 1815) was a German physician with an interest in astronomy. He theorised the existence of a natural energy transference occurring between all animated and inanimate objects; this he called " ani ...

Image:Andrew Jackson Davis.003.jpg, Andrew Jackson Davis, about 1860

Reform-movement links

Spiritualists often set March 31, 1848, as the beginning of their movement. On that date, Kate and Margaret Fox, of Hydesville, New York, reported that they had made contact with a spirit that was later claimed to be the spirit of a murdered peddler whose body was found in the house, though no record of such a person was ever found. The spirit was said to have communicated through rapping noises, audible to onlookers. The evidence of the senses appealed to practically minded Americans, and the Fox sisters became a sensation. As the first celebrity mediums, the sisters quickly became famous for their public séances in New York. However, in 1888 the Fox sisters admitted that this "contact" with the spirit was a hoax, though shortly afterward they recanted that admission.

Spiritualists often set March 31, 1848, as the beginning of their movement. On that date, Kate and Margaret Fox, of Hydesville, New York, reported that they had made contact with a spirit that was later claimed to be the spirit of a murdered peddler whose body was found in the house, though no record of such a person was ever found. The spirit was said to have communicated through rapping noises, audible to onlookers. The evidence of the senses appealed to practically minded Americans, and the Fox sisters became a sensation. As the first celebrity mediums, the sisters quickly became famous for their public séances in New York. However, in 1888 the Fox sisters admitted that this "contact" with the spirit was a hoax, though shortly afterward they recanted that admission.

Amy and Isaac Post

Isaac and Amy Post, were radical Hicksite Quakers from Rochester, New York, and leaders in the nineteenth-century anti-slavery and women's rights movements. Among the first believers in Spiritualism, they helped to associate the young religious ...

, Hicksite Quakers from Rochester, New York

Rochester () is a City (New York), city in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York, the county seat, seat of Monroe County, New York, Monroe County, and the fourth-most populous in the state after New York City, Buffalo, New York, Buffalo, ...

, had long been acquainted with the Fox family, and took the two girls into their home in the late spring of 1848. Immediately convinced of the veracity of the sisters' communications, they became early converts and introduced the young mediums to their circle of radical Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belie ...

friends.

Consequently, many early participants in Spiritualism were radical Quakers and others involved in the mid-nineteenth-century

Consequently, many early participants in Spiritualism were radical Quakers and others involved in the mid-nineteenth-century reforming movement

The Reformist Movement (french: Mouvement réformateur, MR) was a French centrist political alliance created in 1971 by the Radical Party (PR) led by Jean-Jacques Servan-Schreiber, and the Christian-democratic Democratic Centre (CD) headed by Je ...

. These reformers were uncomfortable with more prominent churches because those churches did little to fight slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

and even less to advance the cause of women's rights

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countries, ...

.

Such links with reform movements, often radically socialist, had already been prepared in the 1840s, as the example of Andrew Jackson Davis

Andrew Jackson Davis (August 11, 1826January 13, 1910) was an American Spiritualist, born in Blooming Grove, New York.

Early years

Davis had little education. In 1843 he heard lectures in Poughkeepsie on animal magnetism, the precursor of hypn ...

shows. After 1848, many socialists became ardent spiritualists or occultists. Socialist ideas, especially in the Fourierist

Fourierism () is the systematic set of economic, political, and social beliefs first espoused by French intellectual Charles Fourier (1772–1837). Based upon a belief in the inevitability of communal associations of people who worked and lived to ...

vein, exerted a decisive influence on Kardec and other Spiritists.

The most popular trance lecturer prior to the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

was Cora L. V. Scott

Cora Lodencia Veronica Scott (April 21, 1840 – January 3, 1923) was one of the best-known mediums of the Spiritualism movement of the last half of the 19th century. Most of her work was done as a trance lecturer, though she also wrote some books ...

(1840–1923). Young and beautiful, her appearance on stage fascinated men. Her audiences were struck by the contrast between her physical girlishness and the eloquence with which she spoke of spiritual matters, and found in that contrast support for the notion that spirits were speaking through her. Cora married four times, and on each occasion adopted her husband's last name. During her period of greatest activity, she was known as Cora Hatch.

Another famous woman Spiritualist was Achsa W. Sprague

Achsa W. Sprague (November 17, 1827 – July 6, 1862) was one of the best-known Spiritualists during the 1850s in the United States. Primarily a medium and trance lecturer, she also wrote articles and poetry for Spiritualist publications such as ...

, who was born November 17, 1827, in Plymouth Notch, Vermont

Plymouth Notch is an unincorporated community in the town of Plymouth, Windsor County, Vermont, United States. All or most of the village is included in the Calvin Coolidge Homestead District, a National Historic Landmark.

History

John Calvin Co ...

. At the age of 20, she became ill with rheumatic fever

Rheumatic fever (RF) is an inflammatory disease that can involve the heart, joints, skin, and brain. The disease typically develops two to four weeks after a streptococcal throat infection. Signs and symptoms include fever, multiple painful jo ...

and credited her eventual recovery to intercession by spirits. An extremely popular trance lecturer, she traveled about the United States until her death in 1861. Sprague was an abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

and an advocate of women's rights

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countries, ...

.

Yet another prominent Spiritualist and trance medium prior to the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

was Paschal Beverly Randolph

Paschal Beverly Randolph (October 8, 1825 – July 29, 1875) was an American medical doctor, occultist, spiritualist, trance medium, and writer. He is notable as perhaps the first person to introduce the principles of erotic alchemy to North Am ...

(1825–1875), a man of mixed race, who also played a part in the abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

movement. Nevertheless, many abolitionists and reformers held themselves aloof from the Spiritualist movement; among the skeptics was the famous abolitionist Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

.''Telegrams from the Dead'' (a PBS

The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) is an American public broadcasting, public broadcaster and Non-commercial activity, non-commercial, Terrestrial television, free-to-air television network based in Arlington, Virginia. PBS is a publicly fu ...

television documentary in the "American Experience

''American Experience'' is a television program airing on the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) in the United States. The program airs documentaries, many of which have won awards, about important or interesting events and people in American his ...

" series, first aired October 19, 1994).

Another social reform movement with significant Spiritualist involvement was the effort to improve conditions of Native Americans. As Kathryn Troy notes in a study of Indian ghosts in seances:

Undoubtedly, on some level Spiritualists recognized the Indian spectres that appeared at seances as a symbol of the sins and subsequent guilt of the United States in its dealings with Native Americans. Spiritualists were literally haunted by the presence of Indians. But for many that guilt was not assuaged: rather, in order to confront the haunting and rectify it, they were galvanized into action. The political activism of Spiritualists on behalf of Indians was thus the result of combining white guilt and fear of divine judgment with a new sense of purpose and responsibility.

Believers and skeptics

In the years following the sensation that greeted the Fox sisters, demonstrations of mediumship (séances andautomatic writing

Automatic writing, also called psychography, is a claimed psychic ability allowing a person to produce written words without consciously writing. Practitioners engage in automatic writing by holding a writing instrument and allowing alleged spiri ...

, for example) proved to be a profitable venture, and soon became popular forms of entertainment and spiritual catharsis. The Fox sisters were to earn a living this way and others would follow their lead. Showmanship became an increasingly important part of spiritualism, and the visible, audible, and tangible evidence of spirits escalated as mediums competed for paying audiences. As independent investigating commissions repeatedly established, most notably the 1887 report of the Seybert Commission The Seybert Commission was a group of faculty members at the University of Pennsylvania who in 1884–1887 investigated a number of respected spiritualist mediums, uncovering fraud or suspected fraud in every case that they examined.

Establishment ...

, fraud was widespread, and some of these cases were prosecuted in the courts.

Despite numerous instances of chicanery, the appeal of Spiritualism was strong. Prominent in the ranks of its adherents were those grieving the death of a loved one. Many families during the time of the American Civil War had seen their men go off and never return, and images of the battlefield, produced through the new medium of photography, demonstrated that their loved ones had not only died in overwhelmingly huge numbers, but horribly as well. One well known case is that of Mary Todd Lincoln

Mary Ann Todd Lincoln (December 13, 1818July 16, 1882) served as First Lady of the United States from 1861 until the assassination of her husband, President Abraham Lincoln in 1865.

Mary Lincoln was a member of a large and wealthy, slave-owning ...

who, grieving the loss of her son, organized séances in the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

which were attended by her husband, President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

. The surge of Spiritualism during this time, and later during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, was a direct response to those massive battlefield casualties.Arthur Conan Doyle''The History of Spiritualism Vol I''

Arthur Conan Doyle, 1926. In addition, the movement appealed to reformers, who fortuitously found that the spirits favoured such causes ''du jour'' as abolition of slavery, and equal rights for women. It also appealed to some who had a

materialist

Materialism is a form of philosophical monism which holds matter to be the fundamental substance in nature, and all things, including mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. According to philosophical materialis ...

orientation and rejected organized religion. In 1854 the utopian socialist

Utopian socialism is the term often used to describe the first current of modern socialism and socialist thought as exemplified by the work of Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, Étienne Cabet, and Robert Owen. Utopian socialism is often de ...

Robert Owen

Robert Owen (; 14 May 1771 – 17 November 1858) was a Welsh textile manufacturer, philanthropist and social reformer, and a founder of utopian socialism and the cooperative movement. He strove to improve factory working conditions, promoted e ...

was converted to Spiritualism after "sittings" with the American medium Maria B. Hayden (credited with introducing Spiritualism to England); Owen made a public profession of his new faith in his publication ''The Rational quarterly review'' and later wrote a pamphlet, ''The future of the Human race; or great glorious and future revolution to be effected through the agency of departed spirits of good and superior men and women.

Frank Podmore

Frank Podmore (5 February 1856 – 14 August 1910) was an English author, and founding member of the Fabian Society. He is best known as an influential member of the Society for Psychical Research and for his sceptical writings on spiritualism.

...

, ca. 1895.

File:Portrait of Sir William Crookes (1832 - 1919), chemist Wellcome M0002308.jpg, William Crookes

Sir William Crookes (; 17 June 1832 – 4 April 1919) was a British chemist and physicist who attended the Royal College of Chemistry, now part of Imperial College London, and worked on spectroscopy. He was a pioneer of vacuum tubes, inventing t ...

. Photo published 1904.

Image:Harry price by william hope.jpg, Harry Price

Harry Price (17 January 1881 – 29 March 1948) was a British psychic researcher and author, who gained public prominence for his investigations into psychical phenomena and exposing fraudulent spiritualist mediums. He is best known for ...

, 1922.

William Crookes

Sir William Crookes (; 17 June 1832 – 4 April 1919) was a British chemist and physicist who attended the Royal College of Chemistry, now part of Imperial College London, and worked on spectroscopy. He was a pioneer of vacuum tubes, inventing t ...

(1832–1919), evolutionary biologist Alfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace (8 January 1823 – 7 November 1913) was a British naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator. He is best known for independently conceiving the theory of evolution through natural se ...

(1823–1913) and physicist Sir Oliver Lodge. Nobel laureate Pierre Curie

Pierre Curie ( , ; 15 May 1859 – 19 April 1906) was a French physicist, a pioneer in crystallography, magnetism, piezoelectricity, and radioactivity. In 1903, he received the Nobel Prize in Physics with his wife, Marie Curie, and Henri Becqu ...

was impressed by the mediumistic performances of Eusapia Palladino

Eusapia Palladino (alternative spelling: ''Paladino''; 21 January 1854 – 16 May 1918) was an Italian Spiritualist physical medium. She claimed extraordinary powers such as the ability to levitate tables, communicate with the dead through he ...

and advocated their scientific study. Other prominent adherents included journalist and pacifist William T. Stead

William Thomas Stead (5 July 184915 April 1912) was a British newspaper editor who, as a pioneer of investigative journalism, became a controversial figure of the Victorian era. Stead published a series of hugely influential campaigns whilst ed ...

(1849–1912) and physician and author Arthur Conan Doyle

Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle (22 May 1859 – 7 July 1930) was a British writer and physician. He created the character Sherlock Holmes in 1887 for ''A Study in Scarlet'', the first of four novels and fifty-six short stories about Ho ...

(1859–1930).

Doyle, who lost his son Kingsley in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, was also a member of the Ghost Club

The Ghost Club is a paranormal investigation and research organization, founded in London in 1862. It is believed to be the oldest such organization in the world, though its history has not been continuous. The club still investigates mainly gho ...

. Founded in London in 1862, its focus was the scientific study of alleged paranormal activities in order to prove (or refute) the existence of paranormal phenomena. Famous members of the club included Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian e ...

, Sir William Crookes, Sir William F. Barrett

Sir William Fletcher Barrett (10 February 1844 in Kingston, Jamaica – 26 May 1925) was an English physicist and parapsychologist.

Life

He was born in Jamaica where his father, William Garland Barrett, who was an amateur naturalist, Congre ...

, and Harry Price

Harry Price (17 January 1881 – 29 March 1948) was a British psychic researcher and author, who gained public prominence for his investigations into psychical phenomena and exposing fraudulent spiritualist mediums. He is best known for ...

.Underwood, Peter (1978) "Dictionary of the Supernatural", Harrap Ltd., , p. 144 The Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

séances of Eusapia Palladino

Eusapia Palladino (alternative spelling: ''Paladino''; 21 January 1854 – 16 May 1918) was an Italian Spiritualist physical medium. She claimed extraordinary powers such as the ability to levitate tables, communicate with the dead through he ...

were attended by an enthusiastic Pierre Curie

Pierre Curie ( , ; 15 May 1859 – 19 April 1906) was a French physicist, a pioneer in crystallography, magnetism, piezoelectricity, and radioactivity. In 1903, he received the Nobel Prize in Physics with his wife, Marie Curie, and Henri Becqu ...

and a dubious Marie Curie

Marie Salomea Skłodowska–Curie ( , , ; born Maria Salomea Skłodowska, ; 7 November 1867 – 4 July 1934) was a Polish and naturalized-French physicist and chemist who conducted pioneering research on radioactivity. She was the first ...

. The celebrated New York City physician, John Franklin Gray

John Franklin Gray (September 23, 1804 – June 9, 1882) was an American educator and physician, a pioneer in the field of homoeopathy and one of its first practitioners in the United States. He is also recognized as an important medical reforme ...

, was a prominent spiritualist. Thomas Edison

Thomas Alva Edison (February 11, 1847October 18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices in fields such as electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and motion pictures. These inventio ...

wanted to develop a "spirit phone", an ethereal device that would summon to the living the voices of the dead and record them for posterity.

The claims of Spiritualists and others as to the reality of spirits were investigated by the Society for Psychical Research

The Society for Psychical Research (SPR) is a nonprofit organisation in the United Kingdom. Its stated purpose is to understand events and abilities commonly described as psychic or paranormal. It describes itself as the "first society to condu ...

, founded in London in 1882. The society set up a Committee on Haunted Houses.

Prominent investigators who exposed cases of fraud came from a variety of backgrounds, including professional researchers such as Frank Podmore

Frank Podmore (5 February 1856 – 14 August 1910) was an English author, and founding member of the Fabian Society. He is best known as an influential member of the Society for Psychical Research and for his sceptical writings on spiritualism.

...

of the Society for Psychical Research

The Society for Psychical Research (SPR) is a nonprofit organisation in the United Kingdom. Its stated purpose is to understand events and abilities commonly described as psychic or paranormal. It describes itself as the "first society to condu ...

and Harry Price

Harry Price (17 January 1881 – 29 March 1948) was a British psychic researcher and author, who gained public prominence for his investigations into psychical phenomena and exposing fraudulent spiritualist mediums. He is best known for ...

of the National Laboratory of Psychical Research

The National Laboratory of Psychical Research was established in 1926 by Harry Price, at 16 Queensberry Place, London. Its aim was "to investigate in a dispassionate manner and by purely scientific means every phase of psychic or alleged psychic ...

, and professional conjurers such as John Nevil Maskelyne

John Nevil Maskelyne (22 December 183918 May 1917) was an English stage magician and inventor of the pay toilet, along with other Victorian-era devices. He worked with magicians George Alfred Cooke and David Devant, and many of his illusions a ...

. Maskelyne exposed the Davenport brothers by appearing in the audience during their shows and explaining how the trick was done.

The psychical researcher

The psychical researcher Hereward Carrington

Hereward Carrington (17 October 1880 – 26 December 1958) was a well-known British-born American investigator of psychic phenomena and author. His subjects included several of the most high-profile cases of apparent psychic ability of his times, ...

exposed fraudulent mediums' tricks, such as those used in slate-writing, table-turning

Table-turning (also known as table-tapping, table-tipping or table-tilting) is a type of séance in which participants sit around a table, place their hands on it, and wait for rotations. The table was purportedly made to serve as a means of comm ...

, trumpet mediumship, materializations, sealed-letter reading, and spirit photography

Spirit photography (also called ghost photography) is a type of photography whose primary goal is to capture images of ghosts and other spiritual Non-physical entity, entities, especially in ghost hunting. It dates back to the late 19th century. ...

. The skeptic Joseph McCabe

Joseph Martin McCabe (12 November 1867 – 10 January 1955) was an English writer and speaker on freethought, after having been a Roman Catholic priest earlier in his life. He was "one of the great mouthpieces of freethought in England". Becomi ...

, in his book ''Is Spiritualism Based on Fraud?'' (1920), documented many fraudulent mediums and their tricks.

Magicians

Magician or The Magician may refer to:

Performers

* A practitioner of magic (supernatural)

* A practitioner of magic (illusion)

* Magician (fantasy), a character in a fictional fantasy context

Entertainment

Books

* ''The Magician'', an 18th-ce ...

and writers on magic have a long history of exposing the fraudulent methods of mediumship. During the 1920s, professional magician Harry Houdini

Harry Houdini (, born Erik Weisz; March 24, 1874 – October 31, 1926) was a Hungarian-American escape artist, magic man, and stunt performer, noted for his escape acts. His pseudonym is a reference to his spiritual master, French magician ...

undertook a well-publicised campaign to expose fraudulent mediums; he was adamant that "Up to the present time everything that I have investigated has been the result of deluded brains."''A Magician Among the Spirits'', Harry Houdini

Harry Houdini (, born Erik Weisz; March 24, 1874 – October 31, 1926) was a Hungarian-American escape artist, magic man, and stunt performer, noted for his escape acts. His pseudonym is a reference to his spiritual master, French magician ...

, Arno Press (June 1987), Other magician or magic-author debunkers of spiritualist mediumship have included Chung Ling Soo

William Ellsworth Robinson (April 2, 1861 – March 24, 1918) was an American magician who went by the stage name Chung Ling Soo (). He is mostly remembered today for his accidental death due to a failed bullet catch trick.

Early years

Robinson ...

, Henry Evans, Julien Proskauer

Julien J. Proskauer (June 14, 1893 – December 18, 1958) was an American magician and author.

Proskauer was born June 14, 1893, to Joseph Proskauer and Bertha Richman Proskauer in New York City. He was a friend of Harry Houdini and was well kn ...

, Fulton Oursler

Charles Fulton Oursler (January 22, 1893 – May 24, 1952) was an American journalist, playwright, editor and writer. Writing as Anthony Abbot, he was an author of mysteries and detective fiction. His son was the journalist and author Will Ou ...

, Joseph Dunninger

Joseph Dunninger (April 28, 1892 – March 9, 1975), known as "The Amazing Dunninger", was one of the most famous and proficient mentalists of all time. He was one of the pioneer performers of magic on radio and television. A debunker of fraudulen ...

, and Joseph Rinn

Joseph Francis Rinn (1868–1952) was an American magician and skeptic of paranormal phenomena.

Career

Rinn grew up in New York City. He coached Harry Houdini as a teenager in running at the Pastime Athletic Club. He remained a friend to Houdin ...

.

In February 1921 Thomas Lynn Bradford

Thomas Lynn Bradford ( – February 5, 1921) of Detroit, Michigan was a Spiritualism, spiritualist who died by suicide in an attempt to ascertain the existence of an afterlife and communicate that information to a living accomplice, Ruth Doran. On ...

, in an experiment designed to ascertain the existence of an afterlife, committed suicide in his apartment by blowing out the pilot light on his heater and turning on the gas. After that date, no further communication from him was received by an associate whom he had recruited for the purpose.

Unorganized movement

The movement quickly spread throughout the world; though only in the United Kingdom did it become as widespread as in the United States. Spiritualist organizations were formed in America and Europe, such as the London Spiritualist Alliance, which published a newspaper called ''The Light'', featuring articles such as "Evenings at Home in Spiritual Séance", "Ghosts in Africa" and "Chronicles of Spirit Photography", advertisements for "Mesmerists" andpatent medicine

A patent medicine, sometimes called a proprietary medicine, is an over-the-counter (nonprescription) medicine or medicinal preparation that is typically protected and advertised by a trademark and trade name (and sometimes a patent) and claimed ...

s, and letters from readers about personal contact with ghosts.

In Britain, by 1853, invitations to tea among the prosperous and fashionable often included table-turning, a type of séance in which spirits were said to communicate with people seated around a table by tilting and rotating the table. One prominent convert was the French pedagogist Allan Kardec

Allan Kardec () is the pen name of the French educator, translator, and author Hippolyte Léon Denizard Rivail (; 3 October 1804 – 31 March 1869). He is the author of the five books known as the Spiritist Codification, and the founder of S ...

(1804–1869), who made the first attempt to systematise the movement's practices and ideas into a consistent philosophical system. Kardec's books, written in the last 15 years of his life, became the textual basis of spiritism, which became widespread in Latin countries. In Brazil, Kardec's ideas are embraced by many followers today. In Puerto Rico, Kardec's books were widely read by the upper classes, and eventually gave birth to a movement known as '' mesa blanca'' (white table).

Spiritualism was mainly a middle- and upper-class movement, and especially popular with women. American Spiritualists would meet in private homes for séances, at lecture halls for trance lectures, at state or national conventions, and at summer camps attended by thousands. Among the most significant of the camp meetings were Camp Etna, in

Spiritualism was mainly a middle- and upper-class movement, and especially popular with women. American Spiritualists would meet in private homes for séances, at lecture halls for trance lectures, at state or national conventions, and at summer camps attended by thousands. Among the most significant of the camp meetings were Camp Etna, in Etna, Maine

Etna is a town in Penobscot County, Maine, United States. The population was 1,226 at the 2020 census.

History

Etna is named for the famed Mount Etna in Italy. It was originally known as "Crosbytown" after its first proprietor, Gen. John Cros ...

; Onset Bay Grove, in Onset, Massachusetts

Onset is a census-designated place (CDP) in the town of Wareham, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 1,573 at the 2010 census.

Geography

Onset is located at (41.746424, -70.663251).

According to the United States Census Bureau, th ...

; Lily Dale

Lily Dale is a hamlet, connected with the Spiritualist movement, located in the Town of Pomfret on the east side of Cassadaga Lake, next to the Village of Cassadaga. Located in southwestern New York State, it is one hour southwest of Buffalo ...

, in western New York State; Camp Chesterfield

Camp Chesterfield was founded in 1891 and is the home of the Indiana Association of Spiritualists, located in Chesterfield, Indiana. Camp Chesterfield offers Spiritualist Church services, seminary, and mediumship, faith healing, and spiritual ...

, in Indiana; the Wonewoc Spiritualist Camp

Wonewoc Spiritualist Camp is a Spiritualist Church

A spiritualist church is a church affiliated with the informal spiritualist movement which began in the United States in the 1840s. Spiritualist churches are now found around the world, but are ...

, in Wonewoc, Wisconsin

Wonewoc is a village along the Baraboo River in Juneau County, Wisconsin. The population was 816 at the time of the 2010 census.

History

The name “Wonewoc” is of Indigenous American origin, probably meaning "howling hills". However, at the ...

; and Lake Pleasant, in Montague, Massachusetts

Montague is a town in Franklin County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 8,580 at the 2020 census. It is part of the Springfield, Massachusetts metropolitan statistical area.

The villages of Montague Center, Montague City, Lake ...

. In founding camp meeting

The camp meeting is a form of Protestant Christian religious service originating in England and Scotland as an evangelical event in association with the communion season. It was held for worship, preaching and communion on the American frontier d ...

s, the Spiritualists appropriated a form developed by U.S. Protestant denominations in the early nineteenth century. Spiritualist camp meetings were located most densely in New England, but were also established across the upper Midwest. Cassadaga, Florida

Cassadaga (a Seneca Indian word meaning ''"Water beneath the rocks"'') is a small unincorporated community located in Volusia County, Florida, United States, just north of Deltona. It is especially known for having many psychics and mediums, and ...

, is the most notable Spiritualist camp meeting in the southern states.

A number of Spiritualist periodicals appeared in the nineteenth century, and these did much to hold the movement together. Among the most important were the weeklies the ''Banner of Light

The ''Banner of Light'' was an American spiritualist journal published weekly in newspaper format between 1857 and 1907, the longest lasting and most influential of such journals. It was based in Boston, but covered the movement across the US. The ...

'' (Boston), the ''Religio-Philosophical Journal'' (Chicago), ''Mind and Matter'' (Philadelphia), the ''Spiritualist'' (London), and the ''Medium'' (London). Other influential periodicals were the ''Revue Spirite'' (France), ''Le Messager'' (Belgium), ''Annali dello Spiritismo'' (Italy), ''El Criterio Espiritista'' (Spain), and the ''Harbinger of Light'' (Australia). By 1880, there were about three dozen monthly Spiritualist periodicals published around the world. These periodicals differed a great deal from one another, reflecting the great differences among Spiritualists. Some, such as the British ''Spiritual Magazine'' were Christian and conservative, openly rejecting the reform currents so strong within Spiritualism. Others, such as ''Human Nature'', were pointedly non-Christian and supportive of socialism and reform efforts. Still others, such as the ''Spiritualist'', attempted to view Spiritualist phenomena from a scientific perspective, eschewing discussion on both theological and reform issues.

Books on the supernatural were published for the growing middle class, such as 1852's ''Mysteries'', by Charles Elliott, which contains "sketches of spirits and spiritual things", including accounts of the Salem witch trials

The Salem witch trials were a series of hearings and prosecutions of people accused of witchcraft in colonial Massachusetts between February 1692 and May 1693. More than 200 people were accused. Thirty people were found guilty, 19 of whom w ...

, the Lane ghost

In road transport, a lane is part of a roadway that is designated to be used by a single line of vehicles to control and guide drivers and reduce traffic conflicts. Most public roads (highways) have at least two lanes, one for traffic in each ...

, and the Rochester rappings.

''The Night Side of Nature'', by Catherine Crowe, published in 1853, provided definitions and accounts of wraiths, doppelgängers, apparitions and haunted houses.

Mainstream newspapers treated stories of ghosts and haunting as they would any other news story. An account in the ''Chicago Daily Tribune'' in 1891, "sufficiently bloody to suit the most fastidious taste", tells of a house believed to be haunted by the ghosts of three murder victims seeking revenge against their killer's son, who was eventually driven insane.

Many families, "having no faith in ghosts", thereafter moved into the house, but all soon moved out again.

In the 1920s many "psychic" books were published of varied quality. Such books were often based on excursions initiated by the use of Ouija boards

The ouija ( , ), also known as a spirit board or talking board, is a flat board marked with the letters of the Latin alphabet, the numbers 0–9, the words "yes", "no", occasionally "hello" and "goodbye", along with various symbols and grap ...

. A few of these popular books displayed unorganized Spiritualism, though most were less insightful.

The movement was extremely individualistic, with each person relying on his or her own experiences and reading to discern the nature of the afterlife. Organisation was therefore slow to appear, and when it did it was resisted by mediums and trance lecturers. Most members were content to attend Christian churches, and particularly universalist churches harboured many Spiritualists.

As the Spiritualism movement began to fade, partly through the publicity of fraud accusations and partly through the appeal of religious movements such as Christian science

Christian Science is a set of beliefs and practices associated with members of the Church of Christ, Scientist. Adherents are commonly known as Christian Scientists or students of Christian Science, and the church is sometimes informally know ...

, the Spiritualist Church

A spiritualist church is a church affiliated with the informal spiritualist movement which began in the United States in the 1840s. Spiritualist churches are now found around the world, but are most common in English-speaking countries, while in L ...

was organised. This church can claim to be the main vestige of the movement left today in the United States.

Other mediums

London-born

London-born Emma Hardinge Britten

Emma Hardinge Britten (2 May 1823 – 2 October 1899) was an English advocate for the early Modern Spiritualist Movement. Much of her life and work was recorded and published in her speeches and writing and an incomplete autobiography edite ...

(1823–99) moved to the United States in 1855 and was active in Spiritualist circles as a trance lecturer and organiser. She is best known as a chronicler of the movement's spread, especially in her 1884 ''Nineteenth Century Miracles: Spirits and Their Work in Every Country of the Earth'', and her 1870 ''Modern American Spiritualism'', a detailed account of claims and investigations of mediumship beginning with the earliest days of the movement.

William Stainton Moses

William Stainton Moses (1839 – 5 September 1892) was an English cleric and spiritualist medium. He promoted spirit photography and automatic writing, and co-founded what became the College of Psychic Studies. He resisted scientific examination ...

(1839–92) was an Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

clergyman who, in the period from 1872 to 1883, filled 24 notebooks with automatic writing, much of which was said to describe conditions in the spirit world. However, Frank Podmore

Frank Podmore (5 February 1856 – 14 August 1910) was an English author, and founding member of the Fabian Society. He is best known as an influential member of the Society for Psychical Research and for his sceptical writings on spiritualism.

...

was skeptical of his alleged ability to communicate with spirits and Joseph McCabe

Joseph Martin McCabe (12 November 1867 – 10 January 1955) was an English writer and speaker on freethought, after having been a Roman Catholic priest earlier in his life. He was "one of the great mouthpieces of freethought in England". Becomi ...

described Moses as a "deliberate impostor", suggesting his apports and all of his feats were the result of trickery.

Adelma Vay

Baroness Adelma Vay or von Vay, also Vay de Vaya (born Countess Adelaide von Wurmbrand-Stuppach; October 21, 1840 – May 24, 1925), was a medium and pioneer of spiritualism in Slovenia and Hungary.

Life and work

Vay was the elder daughter o ...

(1840–1925), Hungarian (by origin) spiritistic medium, homeopath

Homeopathy or homoeopathy is a pseudoscientific system of alternative medicine. It was conceived in 1796 by the German physician Samuel Hahnemann. Its practitioners, called homeopaths, believe that a substance that causes symptoms of a dise ...

and clairvoyant

Clairvoyance (; ) is the magical ability to gain information about an object, person, location, or physical event through extrasensory perception. Any person who is claimed to have such ability is said to be a clairvoyant () ("one who sees cl ...

, authored many books about spiritism, written in German and translated into English.

Eusapia Palladino

Eusapia Palladino (alternative spelling: ''Paladino''; 21 January 1854 – 16 May 1918) was an Italian Spiritualist physical medium. She claimed extraordinary powers such as the ability to levitate tables, communicate with the dead through he ...

(1854–1918) was an Italian Spiritualist medium from the slums of Naples who made a career touring Italy, France, Germany, Britain, the United States, Russia and Poland. Palladino was said by believers to perform spiritualist phenomena in the dark: levitating tables, producing apports, and materializing spirits. On investigation, all these things were found to be products of trickery.

The British medium William Eglinton

William Eglinton (1857–1933), also known as William Eglington was a British spiritualist medium who was exposed as a fraud.Hereward Carrington. (1907). ''The Physical Phenomena of Spiritualism''. Herbert B. Turner & Co. pp. 84–90 Massimo Pol ...

(1857–1933) claimed to perform spiritualist phenomena such as movement of objects and materializations. All of his feats were exposed as tricks.

The Bangs Sisters

The Bangs Sisters, Mary "May" E. Bangs (1862–1917) and Elizabeth "Lizzie" Snow Bangs (1859–1920), were two fraudulent spiritualist mediums from Chicago, who made a career out of painting the dead or "Spirit Portraits".

Career

Elizabeth was ...

, Mary "May" E. Bangs (1862–1917) and Elizabeth "Lizzie" Snow Bangs (1859–1920), were two Spiritualist mediums based in Chicago, who made a career out of painting the dead or "Spirit Portraits".

Mina Crandon

Mina "Margery" Crandon (1888–November 1, 1941) was a psychical medium who claimed that she channeled her dead brother, Walter Stinson. Investigators who studied Crandon concluded that she had no such paranormal ability, and others detected her ...

(1888–1941), a spiritualist medium in the 1920s, was known for producing an ectoplasm hand during her séances. The hand was later exposed as a trick when biologists found it to be made from a piece of carved animal liver. In 1934, the psychical researcher Walter Franklin Prince

Walter Franklin Prince (22 April 1863 – 7 August 1934) was an American parapsychologist and founder of the Boston Society for Psychical Research in Boston.Berger, Arthur S. (1988). ''Walter Franklin Prince: A Portrait''. In ''Lives and Letters ...

described the Crandon case as "the most ingenious, persistent, and fantastic complex of fraud in the history of psychic research."

The American voice medium

The American voice medium Etta Wriedt

Etta Wriedt (1859-1942) was an American direct voice medium.

Wriedt was born in Detroit and was well known in the field of spiritualism, she employed a trumpet in the darkness of the séance room which she claimed spirits would use to make noises ...

(1859–1942) was exposed as a fraud by the physicist Kristian Birkeland

Kristian Olaf Bernhard Birkeland (13 December 1867 – 15 June 1917) was a Norwegian scientist. He is best remembered for his theories of atmospheric electric currents that elucidated the nature of the aurora borealis. In order to fund his resea ...

when he discovered that the noises produced by her trumpet were caused by chemical explosions induced by potassium and water and in other cases by lycopodium powder.

Another well-known medium was the Scottish materialization medium Helen Duncan

Victoria Helen McCrae Duncan (née MacFarlane, 25 November 1897 – 6 December 1956) was a Scottish medium best known as the last person to be imprisoned under the Witchcraft Act 1735 for fraudulent claims. She was famous for producing ectopla ...

(1897–1956). In 1928 photographer Harvey Metcalfe attended a series of séances at Duncan's house and took flash photographs of Duncan and her alleged "materialization" spirits, including her spirit guide "Peggy". The photographs revealed the "spirits" to have been fraudulently produced, using dolls made from painted papier-mâché masks, draped in old sheets. Duncan was later tested by Harry Price

Harry Price (17 January 1881 – 29 March 1948) was a British psychic researcher and author, who gained public prominence for his investigations into psychical phenomena and exposing fraudulent spiritualist mediums. He is best known for ...

at the National Laboratory of Psychical Research

The National Laboratory of Psychical Research was established in 1926 by Harry Price, at 16 Queensberry Place, London. Its aim was "to investigate in a dispassionate manner and by purely scientific means every phase of psychic or alleged psychic ...

; photographs revealed Duncan's ectoplasm to be made from cheesecloth

Cheesecloth is a loose-woven gauze-like carded cotton cloth used primarily in cheesemaking and cooking.

Grades

Cheesecloth is available in at least seven different grades, from open to extra-fine weave. Grades are distinguished by the numbe ...

, rubber gloves, and cut-out heads from magazine covers.

Evolution

Spiritualists reacted with an uncertainty to the theories ofevolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

in the late 19th and early 20th century. Broadly speaking the concept of evolution fitted the spiritualist thought of the progressive development of humanity. At the same time, however, the belief in the animal origins of humanity threatened the foundation of the immortality of the spirit

Spirit or spirits may refer to:

Liquor and other volatile liquids

* Spirits, a.k.a. liquor, distilled alcoholic drinks

* Spirit or tincture, an extract of plant or animal material dissolved in ethanol

* Volatile (especially flammable) liquids, ...

, for if humans had not been created by God, it was scarcely plausible that they would be specially endowed with spirits. This led to Spiritualists embracing spiritual evolution

Spiritual evolution, also called higher evolution, is the idea that the mind or spirit, in analogy to biological evolution, collectively evolves from a simple form dominated by nature, to a higher form dominated by the Spiritual or Divine. It is di ...

.

The Spiritualists' view of evolution did not stop at death. Spiritualism taught that after death spirits progressed to spiritual states in new spheres of existence. According to Spiritualists evolution occurred in the spirit world "at a rate more rapid and under conditions more favourable to growth" than encountered on earth.Janet Oppenheim, The Other World: Spiritualism and Psychical Research in England, 1850–1914, 1988, p. 270

In a talk at the London Spiritualist Alliance, John Page Hopps

John Page Hopps (6 November 1834 – 6 April 1911) was a Unitarianism, Unitarian minister and Spiritualism, spiritualist.Watts, Michael R. (2015). ''The Dissenters: Volume III: The Crisis and Conscience of Nonconformity''. Oxford University Press. ...

(1834–1911) supported both evolution and Spiritualism. Hopps claimed humanity had started off imperfect "out of the animal's darkness" but would rise into the "angel's marvellous light". Hopps claimed humans were not fallen but rising creatures and that after death they would evolve on a number of spheres of existence to perfection.

Theosophy

Theosophy is a religion established in the United States during the late 19th century. It was founded primarily by the Russian Helena Blavatsky and draws its teachings predominantly from Blavatsky's writings. Categorized by scholars of religion a ...

is in opposition to the spiritualist interpretation of evolution. Theosophy teaches a metaphysical theory of evolution mixed with human devolution

Devolution, de-evolution, or backward evolution (not to be confused with dysgenics) is the notion that species can revert to supposedly more primitive forms over time. The concept relates to the idea that evolution has a purpose (teleology) and ...

. Spiritualists do not accept the devolution of the theosophists. To theosophy humanity starts in a state of perfection (see Golden age

The term Golden Age comes from Greek mythology, particularly the ''Works and Days'' of Hesiod, and is part of the description of temporal decline of the state of peoples through five Ages of Man, Ages, Gold being the first and the one during ...

) and falls into a process of progressive materialization (devolution), developing the mind and losing the spiritual consciousness. After the gathering of experience and growth through repeated reincarnations

Reincarnation, also known as rebirth or transmigration, is the philosophical or religious concept that the non-physical essence of a living being begins a new life in a different physical form or body after biological death. Resurrection is a ...

humanity will regain the original spiritual state, which is now one of self-conscious perfection.

Theosophy and Spiritualism were both very popular metaphysical schools of thought especially in the early 20th century and thus were always clashing in their different beliefs. Madame Blavatsky

Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, uk, Олена Петрівна Блаватська, Olena Petrivna Blavatska (; – 8 May 1891), often known as Madame Blavatsky, was a Russian mystic and author who co-founded the Theosophical Society in 1875 ...

was critical of Spiritualism; she distanced theosophy from Spiritualism as far as she could and allied herself with eastern occultism.

The Spiritualist

The Spiritualist Gerald Massey

Gerald Massey (; 29 May 1828 – 29 October 1907) was an English poet and writer on Spiritualism and Ancient Egypt.

Early life

Massey was born near Tring, Hertfordshire in England to poor parents. When little more than a child, he was made to ...

claimed that Darwin's theory of evolution was incomplete: