Socialist Afghanistan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Democratic Republic of Afghanistan (DRA),, renamed the Republic of Afghanistan, in 1987, was the

While Amin and Taraki had a very close relationship at the beginning, the relationship soon deteriorated. Amin, who had helped to create a

While Amin and Taraki had a very close relationship at the beginning, the relationship soon deteriorated. Amin, who had helped to create a

While Najibullah may have been the ''

While Najibullah may have been the ''

The PDPA constitution was written during the party's First Congress in 1965. The constitution regulated all party activities and modelled itself after the

The PDPA constitution was written during the party's First Congress in 1965. The constitution regulated all party activities and modelled itself after the

* The Parcham faction was the more moderate of the two and was steadfastly pro-Soviet. This position would hurt its popularity when it came to power following the Soviet intervention. Before the Saur Revolution, the Parcham faction had been the Soviets' favored faction. Following the Parchamites' seizure of power with Soviet assistance, party discipline was breaking down because of the Khalq–Parcham feud. After the PDPA government had ordered the replacement of seven Khalqist officers with Parchamites, the seven officers sent the intended replacements back. While the Parchamite government gave up trying to take over the armed forces, it did announce the execution of 13 officials who had worked for Amin. These executions led to three failed Khalqist coups in June, July and October 1980. The Western press, during the anti-Parchamite purge of 1979, referred to the Parcham faction as "moderate socialist intellectuals".

Throughout PDPA history there were also other factions, such as the Kar faction led by Dastagir Panjsheri, who later became a Khalqist, and Settam-e-Melli formed and led by Tahir Badakhshi. The Settam-e-Melli was a part of the insurgency against the PDPA government. In 1979, a Settam-e-Melli group killed

* The Parcham faction was the more moderate of the two and was steadfastly pro-Soviet. This position would hurt its popularity when it came to power following the Soviet intervention. Before the Saur Revolution, the Parcham faction had been the Soviets' favored faction. Following the Parchamites' seizure of power with Soviet assistance, party discipline was breaking down because of the Khalq–Parcham feud. After the PDPA government had ordered the replacement of seven Khalqist officers with Parchamites, the seven officers sent the intended replacements back. While the Parchamite government gave up trying to take over the armed forces, it did announce the execution of 13 officials who had worked for Amin. These executions led to three failed Khalqist coups in June, July and October 1980. The Western press, during the anti-Parchamite purge of 1979, referred to the Parcham faction as "moderate socialist intellectuals".

Throughout PDPA history there were also other factions, such as the Kar faction led by Dastagir Panjsheri, who later became a Khalqist, and Settam-e-Melli formed and led by Tahir Badakhshi. The Settam-e-Melli was a part of the insurgency against the PDPA government. In 1979, a Settam-e-Melli group killed

The strength of the army was greatly weakened during the early stages of PDPA rule. One of the main reasons for the small size was that the Soviet military were afraid the Afghan army would defect ''

The strength of the army was greatly weakened during the early stages of PDPA rule. One of the main reasons for the small size was that the Soviet military were afraid the Afghan army would defect ''

During communist rule, the PDPA government reformed the education system; education was stressed for both sexes, and widespread literacy programmes were set up. By 1988, women made up 40 percent of the doctors and 60 percent of the teachers at Kabul University; 440,000 female students were enrolled in different educational institutions and 80,000 more in literacy programs. In addition to introducing mass literacy campaigns for women and men, the PDPA agenda included: massive land reform program; the abolition of bride price; and raising the marriage age to 16 for girls and to 18 for boys.

However, the mullahs and tribal chiefs in the interiors viewed compulsory education, especially for women, as going against the grain of tradition, as anti-religious, and as a challenge to male authority. This resulted in an increase in shootings of women in

During communist rule, the PDPA government reformed the education system; education was stressed for both sexes, and widespread literacy programmes were set up. By 1988, women made up 40 percent of the doctors and 60 percent of the teachers at Kabul University; 440,000 female students were enrolled in different educational institutions and 80,000 more in literacy programs. In addition to introducing mass literacy campaigns for women and men, the PDPA agenda included: massive land reform program; the abolition of bride price; and raising the marriage age to 16 for girls and to 18 for boys.

However, the mullahs and tribal chiefs in the interiors viewed compulsory education, especially for women, as going against the grain of tradition, as anti-religious, and as a challenge to male authority. This resulted in an increase in shootings of women in

Soviet Air Power: Tactics and Weapons Used in Afghanistan

by Lieutenant Colonel Denny R. Nelson

Video on Afghan-Soviet War

from th

Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

Soviet Documents

Online Afghan Calendar with Historical dates

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Democratic Republic Of Afghanistan Former political entities in Afghanistan Modern history of Afghanistan

Afghan

Afghan may refer to:

*Something of or related to Afghanistan, a country in Southern-Central Asia

*Afghans, people or citizens of Afghanistan, typically of any ethnicity

** Afghan (ethnonym), the historic term applied strictly to people of the Pas ...

state during the one-party rule

A one-party state, single-party state, one-party system, or single-party system is a type of sovereign state in which only one political party has the right to form the government, usually based on the existing constitution. All other parties ...

of the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) from 1978 to 1992.

The PDPA came to power through the Saur Revolution, which ousted the regime of the unelected autocrat Mohammed Daoud Khan

Mohammed Daoud Khan ( ps, ), also romanized as Daud Khan or Dawood Khan (18 July 1909 – 28 April 1978), was an Afghan politician and general who served as prime minister of Afghanistan from 1953 to 1963 and, as leader of the 1973 Afghan coup ...

; he was succeeded by Nur Muhammad Taraki as the head of state and government on 30 April 1978. Taraki and Hafizullah Amin

Hafizullah Amin (Pashto/ prs, حفيظ الله امين; 1 August 192927 December 1979) was an Afghan communist revolutionary, politician and teacher. He organized the Saur Revolution of 1978 and co-founded the Democratic Republic of Afghan ...

, the organizer of the Saur Revolution, introduced several contentious reforms during their rule, such as land and marriage reforms and an enforced policy of de-Islamization

Islamization, Islamicization, or Islamification ( ar, أسلمة, translit=aslamāh), refers to the process through which a society shifts towards the religion of Islam and becomes largely Muslim. Societal Islamization has historically occur ...

alongside the promotion of socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

. Amin also added on the reforms introduced by Khan, such as universal education

Universal access to education is the ability of all people to have equal opportunity in education, regardless of their social class, race, gender, sexuality, ethnic background or physical and mental disabilities. The term is used both in col ...

and equal rights for women

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countries, ...

. Soon after taking power, a power struggle began between the hardline ''Khalq

Khalq ( ps, خلق, ) was a faction of the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA). Its historical ''de facto'' leaders were Nur Muhammad Taraki (1967–1979), Hafizullah Amin (1979) and Sayed Mohammad Gulabzoy (1979–1990). It was als ...

'' faction led by Taraki and Amin, and the moderate ''Parcham

Parcham (Pashto and prs, پرچم, ) was the name of one of the factions of the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan, formed in 1967 following its split and led for most of its history by Babrak Karmal and Mohammed Najibullah. The basic id ...

'' faction led by Babrak Karmal

Babrak Karmal (Farsi/ Pashto: , born Sultan Hussein; 6 January 1929 – 1 or 3 December 1996) was an Afghan revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Afghanistan, serving in the post of General Secretary of the People's Democratic Pa ...

. The Khalqists emerged victorious and the bulk of the Parchamites were subsequently purged from the PDPA, while the most prominent Parcham leaders were exiled to the Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

.

After the Khalq–Parcham struggle, another power struggle arose between Taraki and Amin within the Khalq faction, in which Amin gained the upper hand and later had Taraki killed on his orders. Due to earlier reforms, Amin's rule proved unpopular within both Afghanistan and the Soviet Union. A Soviet intervention supported by the Afghan government had begun in December 1979, and on 27 December, Amin was assassinated by Soviet military forces; Karmal became the leader of Afghanistan in his place. The Karmal era, which lasted from 1979 to 1986, was marked by the height of the Soviet–Afghan War

The Soviet–Afghan War was a protracted armed conflict fought in the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan from 1979 to 1989. It saw extensive fighting between the Soviet Union and the Afghan mujahideen (alongside smaller groups of anti-Soviet ...

, in which Soviet and Afghan government forces fought against the Afghan mujahideen in order to consolidate control over Afghanistan. The war resulted in a large number of civilian casualties as well as the creation of millions of refugees who fled into Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

and Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

. The Fundamental Principles, a constitution, was introduced by the government in April 1980, and several non-PDPA members were allowed into government as part of its policy of broadening its support base. However, Karmal's policies failed to bring peace to the war-ravaged country, and in 1986, he was succeeded as PDPA General Secretary by Mohammad Najibullah

Mohammad Najibullah Ahmadzai (Pashto/ prs, محمد نجیبالله احمدزی, ; 6 August 1947 – 27 September 1996), commonly known as Dr. Najib, was an Afghan politician who served as the General Secretary of the People's Democratic Par ...

.

Najibullah pursued a policy of National Reconciliation

National Reconciliation is the term used for establishment of so-called 'national unity' in countries beset with political problems. In Afghanistan the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan government under Babrak Karmal issued a ten-point rec ...

with the opposition: a new Afghan constitution was introduced in 1987 and democratic elections were held in 1988 (which were boycotted by the mujahideen). After the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan

The final and complete withdrawal of Soviet combatant forces from Afghanistan began on 15 May 1988 and ended on 15 February 1989 under the leadership of Colonel-General Boris Gromov.

Planning for the withdrawal of the Soviet Union (USSR) from t ...

in 1988–1989, the government faced increasing resistance. 1990 proved to be a year of change in Afghan politics as another constitution was introduced that stated Afghanistan's nature as an Islamic republic, and the PDPA was transformed into the Watan Party

Watan (Arabic: وطن) or Al-Watan with the definite article al- (Arabic: الوطن), meaning homeland, heimat, country, or nation, may refer to:

Politics

Al-Watan means 'national' in Arabic and in Persian (وطن), the articles titles on Wikipe ...

, which continues to exist. On the military front, the government proved capable of defeating the armed opposition in open battle, as demonstrated in the Battle of Jalalabad. However, with an aggressive armed opposition and internal difficulties such as a failed coup attempt by the Khalq faction in 1990 coupled with the dissolution of the Soviet Union

The dissolution of the Soviet Union, also negatively connoted as rus, Разва́л Сове́тского Сою́за, r=Razvál Sovétskogo Soyúza, ''Ruining of the Soviet Union''. was the process of internal disintegration within the Sov ...

in 1991, the Najibullah government collapsed in April 1992. The collapse of Najibullah's government triggered another civil war that led to the rise of the Taliban

The Taliban (; ps, طالبان, ṭālibān, lit=students or 'seekers'), which also refers to itself by its state name, the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a Deobandi Islamic fundamentalist, militant Islamist, jihadist, and Pasht ...

and their eventual takeover of most of Afghanistan by 1996.

History

Geographically, the DRA was bordered by Pakistan in the south and east; Iran in the west; the Soviet Union (via the Turkmen, Uzbek, and Tajik SSRs) in the north; and China in the far northeast covering of its territory.Saur Revolution and Taraki: 1978–1979

Mohammad Daoud Khan

Mohammed Daoud Khan ( ps, ), also romanized as Daud Khan or Dawood Khan (18 July 1909 – 28 April 1978), was an Afghan politician and general who served as prime minister of Afghanistan from 1953 to 1963 and, as leader of the 1973 Afghan coup ...

, the President of the Republic of Afghanistan

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

from 1973 to 1978, was ousted during the Saur Revolution (April Revolution) following the death of Mir Akbar Khyber

Mir Akbar Khyber (January 11, 1925 – April 17, 1978) was an Afghan left-wing intellectual and a leader of the Parcham faction of People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA). His assassination by an unidentified person or people led to the o ...

, a Parcham

Parcham (Pashto and prs, پرچم, ) was the name of one of the factions of the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan, formed in 1967 following its split and led for most of its history by Babrak Karmal and Mohammed Najibullah. The basic id ...

ite politician from the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA), who died under mysterious circumstances. Hafizullah Amin

Hafizullah Amin (Pashto/ prs, حفيظ الله امين; 1 August 192927 December 1979) was an Afghan communist revolutionary, politician and teacher. He organized the Saur Revolution of 1978 and co-founded the Democratic Republic of Afghan ...

, a Khalq

Khalq ( ps, خلق, ) was a faction of the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA). Its historical ''de facto'' leaders were Nur Muhammad Taraki (1967–1979), Hafizullah Amin (1979) and Sayed Mohammad Gulabzoy (1979–1990). It was als ...

ist, was the coup's chief architect. Nur Muhammad Taraki, the leader of the Khalqists, was elected Chairman

The chairperson, also chairman, chairwoman or chair, is the presiding officer of an organized group such as a board, committee, or deliberative assembly. The person holding the office, who is typically elected or appointed by members of the grou ...

of the Presidium of the Revolutionary Council

A workers' council or labor council is a form of political and economic organization in which a workplace or municipality is governed by a council made up of workers or their elected delegates. The workers within each council decide on what thei ...

, Chairman

The chairperson, also chairman, chairwoman or chair, is the presiding officer of an organized group such as a board, committee, or deliberative assembly. The person holding the office, who is typically elected or appointed by members of the grou ...

of the Council of Ministers

A council is a group of people who come together to consult, deliberate, or make decisions. A council may function as a legislature, especially at a town, city or county/ shire level, but most legislative bodies at the state/provincial or nati ...

and retained his post as General Secretary of the PDPA Central Committee. Under him was Babrak Karmal

Babrak Karmal (Farsi/ Pashto: , born Sultan Hussein; 6 January 1929 – 1 or 3 December 1996) was an Afghan revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Afghanistan, serving in the post of General Secretary of the People's Democratic Pa ...

, the leader of the Parcham faction, as Deputy Chairman of the Revolutionary Council and Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers, Amin as Council of Ministers deputy chairman and Minister of Foreign Affairs

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between cou ...

, and Mohammad Aslam Watanjar

Mohammad Aslam Watanjar ( ps, محمداسلم وطنجار, 1946 – November 2000) was an Afghanistan, Afghan general and politician. He played a significant role in the coup in 1978 that killed the Afghan president Mohammad Daud Khan and started ...

as Council of Ministers deputy chairman. The appointment of Karmal, Amin and Watanjar as Council of Ministers deputy chairmen proved unstable, and it led to three different governments being established within the government; the Khalq faction was answerable to Amin, the Parchamites were answerable to Karmal and the military officers (who were Parchamites) were answerable to Watanjar.

The first conflict between the Khalqists and Parchamites arose when the Khalqists wanted to give PDPA Central Committee membership to military officers who participated in the Saur Revolution. Amin, who previously opposed the appointment of military officers to the PDPA leadership, altered his position; he now supported their elevation. The PDPA Politburo voted in favour of giving membership to the military officers; the victors (the Khalqists) portrayed the Parchamites as opportunists (they implied that the Parchamites had ridden the revolutionary wave, but not actually participated in the revolution). To make matters worse for the Parchamites, the term Parcham was, according to Taraki, a word synonymous with factionalism. On 27 June, three months after the revolution, Amin managed to outmaneuver the Parchamites at a Central Committee meeting. The meeting decided that the Khalqists had the exclusive right to formulate and decide policy, which left the Parchamites impotent. Karmal was exiled. Later, a coup planned by the Parchamites and led by Karmal was discovered by the Khalqist leadership, prompting a swift reaction; a purge of Parchamites began. Parchamite ambassadors were recalled, but few returned; for instance, Karmal and Mohammad Najibullah

Mohammad Najibullah Ahmadzai (Pashto/ prs, محمد نجیبالله احمدزی, ; 6 August 1947 – 27 September 1996), commonly known as Dr. Najib, was an Afghan politician who served as the General Secretary of the People's Democratic Par ...

stayed in their respective countries.

During Taraki's rule, an unpopular land reform

Land reform is a form of agrarian reform involving the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution, generally of agricultural ...

was introduced, leading to the requisitioning of land by the government without compensation; it disrupted lines of credit and led to some crop buyers boycotting beneficiaries of the reform, causing agricultural harvests to plummet and rising discontent amongst Afghans. When Taraki realized the degree of popular dissatisfaction with the reform he began to curtail the policy. Afghanistan's long history of resistance to any type of strong centralized governmental control further undermined his authority. Consequently, much of the land reform did not get implemented nationwide. In the months following the coup, Taraki and other party leaders initiated other policies that challenged both traditional Afghan values and well-established traditional power structures in rural areas. Taraki introduced women to political life and legislated an end to forced marriage. The strength of the anti-reform backlash would ultimately lead to the Afghan Civil War.

Amin and the Soviet intervention: 1979

While Amin and Taraki had a very close relationship at the beginning, the relationship soon deteriorated. Amin, who had helped to create a

While Amin and Taraki had a very close relationship at the beginning, the relationship soon deteriorated. Amin, who had helped to create a personality cult

A cult of personality, or a cult of the leader, Mudde, Cas and Kaltwasser, Cristóbal Rovira (2017) ''Populism: A Very Short Introduction''. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 63. is the result of an effort which is made to create an id ...

centered on Taraki, soon became disgusted with the shape it took and with Taraki, who had begun to believe in his own brilliance. Taraki began dismissing Amin's suggestions, fostering in Amin a deep sense of resentment. As their relationship turned increasingly sour, a power struggle developed between them for control of the Afghan Army

The Army of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (), also referred to as the Islamic Emirate Army and the Afghan Army, is the land force branch of the Armed Forces of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. The roots of an army in Afghanistan can be tr ...

. Following the 1979 Herat uprising, the Revolutionary Council and the PDPA Politburo established the Homeland Higher Defence Council. Taraki was elected its chairman, while Amin became its deputy. Amin's appointment, and the acquisition of the premiership (as Chairman of the Council of Ministers), was not a step further up the ladder as one might assume; due to constitutional reforms, Amin's new offices were more or less powerless. There was a failed assassination attempt led by the Gang of Four, which consisted of Watanjar, Sayed Mohammad Gulabzoy

Major General Sayed Muhammad Gulabzoi (born 1951) is an Afghan politician. An ethnic Pashtun from the Zadran tribe, Gulabzoi was born in Paktia Province. An Air Force mechanic by training, he studied at the Air Force college. As an air force offi ...

, Sherjan Mazdoryar and Assadullah Sarwari. This assassination attempt prompted Amin to conspire against Taraki, and when Taraki returned from a trip to Havana

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.

, he was ousted, and later suffocated on Amin's orders.

During his 104 days in power, Amin became committed to establishing a collective leadership

A collective is a group of entities that share or are motivated by at least one common issue or interest, or work together to achieve a common objective. Collectives can differ from cooperatives in that they are not necessarily focused upon an ...

. When Taraki was ousted, Amin promised "from now on there will be no one-man government...". Prior to the Soviet intervention, the PDPA executed between 1,000 and 27,000 people, mostly at Pul-e-Charkhi prison

Pul-e-Charkhi Prison (Pashto/Dari: زندان پل چرخی), also known as the Afghan National Detention Facility, is the largest prison in Afghanistan, located in the outskirts east of Kabul. As of 2018, it holds up to 5,000 inmates. The prison ...

. Between 17,000 and 25,000 people were arrested during Taraki's and Amin's rules combined. Amin was not liked by the Afghan people. During his rule, opposition to the communist regime

A communist state, also known as a Marxist–Leninist state, is a one-party state that is administered and governed by a communist party guided by Marxism–Leninism. Marxism–Leninism was the state ideology of the Soviet Union, the Cominte ...

increased, and the government lost control of the countryside. The state of the Afghan military

("The land belongs to Allah, the rule belongs to Allah")

, founded = 1997

, current_form =

, branches =

* Afghan Army

* Afghan Air Force

, headquarters = Kabul

, website =

, commander-in-chief ...

deteriorated under Amin; due to desertions the number of military personnel in the Afghan army decreased from 100,000, in the immediate aftermath of the Saur Revolution, to somewhere between 50,000 and 70,000. Another problem was that the KGB had penetrated the PDPA, the military and the government bureaucracy. While his position in Afghanistan was becoming more perilous by the day, his enemies who were exiled in the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

were agitating for his removal. Babrak Karmal

Babrak Karmal (Farsi/ Pashto: , born Sultan Hussein; 6 January 1929 – 1 or 3 December 1996) was an Afghan revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Afghanistan, serving in the post of General Secretary of the People's Democratic Pa ...

, the Parchamite leader, met several leading Eastern Bloc figures during this period, and Mohammad Aslam Watanjar

Mohammad Aslam Watanjar ( ps, محمداسلم وطنجار, 1946 – November 2000) was an Afghanistan, Afghan general and politician. He played a significant role in the coup in 1978 that killed the Afghan president Mohammad Daud Khan and started ...

, Sayed Mohammad Gulabzoy

Major General Sayed Muhammad Gulabzoi (born 1951) is an Afghan politician. An ethnic Pashtun from the Zadran tribe, Gulabzoi was born in Paktia Province. An Air Force mechanic by training, he studied at the Air Force college. As an air force offi ...

and Assadullah Sarwari wanted to exact revenge on Amin.

Meantime in the Soviet Union, the Special Commission of the Politburo on Afghanistan, which consisted of Yuri Andropov

Yuri Vladimirovich Andropov (– 9 February 1984) was the sixth paramount leader of the Soviet Union and the fourth General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. After Leonid Brezhnev's 18-year rule, Andropov served in the p ...

, Andrei Gromyko

Andrei Andreyevich Gromyko (russian: Андрей Андреевич Громыко; be, Андрэй Андрэевіч Грамыка; – 2 July 1989) was a Soviet communist politician and diplomat during the Cold War. He served as ...

, Dmitriy Ustinov

Dmitriy Fyodorovich Ustinov (russian: Дмитрий Фёдорович Устинов; 30 October 1908 – 20 December 1984) was a Marshal of the Soviet Union and Soviet politician during the Cold War. He served as a Central Committee se ...

and Boris Ponomarev

Boris Nikolayevich Ponomarev (russian: Бори́с Никола́евич Пономарёв) (17 January 1905 – 21 December 1995) was a Soviet politician, ideologist, historian and member of the Secretariat of the Communist Party of the Sovie ...

, wanted to end the impression that the Soviet government supported Amin's leadership and policies. Andropov fought hard for Soviet intervention, telling Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev; uk, links= no, Леонід Ілліч Брежнєв, . (19 December 1906– 10 November 1982) was a Soviet Union, Soviet politician who served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Gener ...

that Amin's policies had destroyed the military and the government's capability to handle the crisis by use of mass repression. The plan, according to Andropov, was to assemble a small force to intervene and remove Amin from power and replace him with Karmal. The Soviet Union declared its plan to intervene in Afghanistan on 12 December 1979, and the Soviet leadership initiated Operation Storm-333

Operation Storm-333 (russian: Шторм-333, ), also known as the Tajbeg Palace Assault, was executed by the Soviet Union in Afghanistan on 27 December 1979. It saw Spetsnaz storm the heavily fortified Tajbeg Palace in Kabul and subsequently as ...

(the first phase of the intervention) on 27 December 1979.

Amin remained trustful of the Soviet Union until the very end, despite the deterioration of official relations with the Soviet Union. When the Afghan intelligence service handed Amin a report that the Soviet Union would invade the country and topple him, Amin claimed the report was a product of imperialism

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic and ...

. His view can be explained by the fact that the Soviet Union, after several months, decided to send troops into Afghanistan. Contrary to normal Western beliefs, Amin was informed of the Soviet decision to send troops into Afghanistan. Amin was killed by Soviet forces on 27 December 1979.

Karmal era: 1979–1986

Karmal ascended to power following Amin's assassination. On 27 DecemberRadio Kabul

Radio Afghanistan, also known as Radio Kabul or Voice of Sharia, is the Public broadcasting, public radio station of Afghanistan, owned by Radio Television Afghanistan. The frequencies are 1107 kHz (AM) and 105.2 MHz (FM) for the Kabul area. The ...

broadcast Karmal's pre-recorded speech, which stated "Today the torture machine of Amin has been smashed, his accomplices – the primitive executioners, usurpers and murderers of tens of thousand of our fellow countrymen – fathers, mothers, sisters, brothers, sons and daughters, children and old people...". On 1 January Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev; uk, links= no, Леонід Ілліч Брежнєв, . (19 December 1906– 10 November 1982) was a Soviet Union, Soviet politician who served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Gener ...

, the General Secretary

Secretary is a title often used in organizations to indicate a person having a certain amount of authority, power, or importance in the organization. Secretaries announce important events and communicate to the organization. The term is derived ...

of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, and Alexei Kosygin

Alexei Nikolayevich Kosygin ( rus, Алексе́й Никола́евич Косы́гин, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsʲej nʲɪkɐˈla(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ kɐˈsɨɡʲɪn; – 18 December 1980) was a Soviet statesman during the Cold War. He served as the Premi ...

, the Soviet Chairman

The chairperson, also chairman, chairwoman or chair, is the presiding officer of an organized group such as a board, committee, or deliberative assembly. The person holding the office, who is typically elected or appointed by members of the grou ...

of the Council of Ministers

A council is a group of people who come together to consult, deliberate, or make decisions. A council may function as a legislature, especially at a town, city or county/ shire level, but most legislative bodies at the state/provincial or nati ...

, congratulated Karmal on his "election" as leader, before any Afghan state or party organ had elected him to anything.

When he came to power, Karmal promised an end to executions, the establishment of democratic institutions and free elections, the creation of a constitution, the legalisation of parties other than the PDPA, and respect for individual and personal property. Prisoners incarcerated under the two previous governments would be freed in a general amnesty. He even promised that a coalition government was going to be established that was not going to espouse socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

. At the same time, he told the Afghan people that he had negotiated with the Soviet Union to give economic, military and political assistance. Even if Karmal indeed wanted all this, it would be impossible to put it into practice in the presence of the Soviet Union. Most Afghans mistrusted the government at this time. Many still remembered that Karmal had said he would protect private capital in 1978, a promise later proven to be a lie.

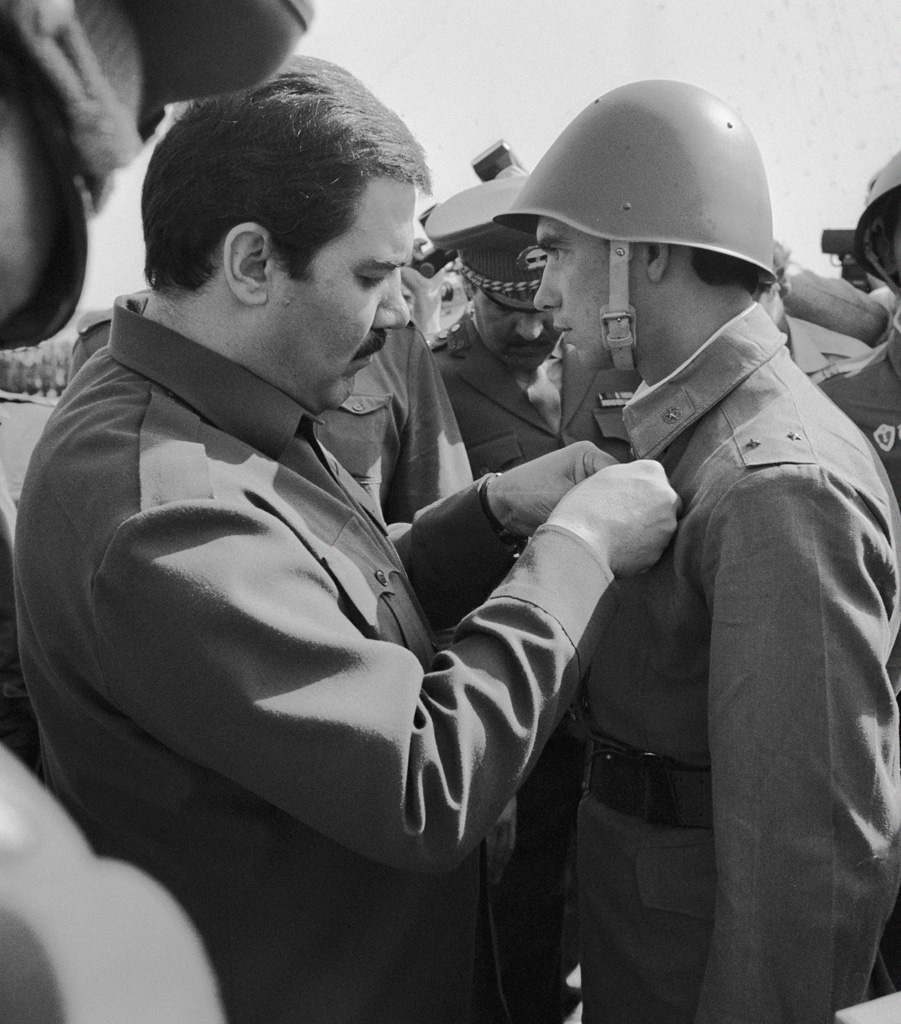

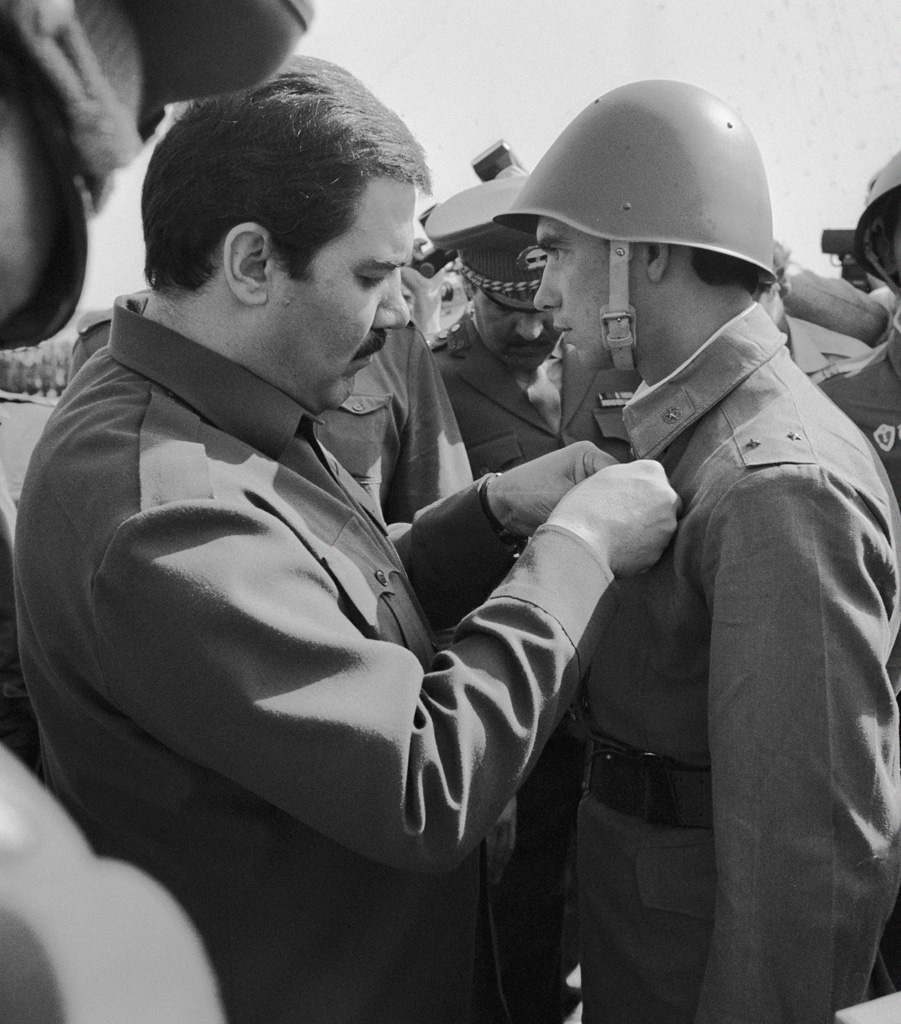

When a political solution failed, the Afghan government and the Soviet military decided to solve the conflict militarily. The change from a political to a military solution came gradually. It began in January 1981: Karmal doubled wages for military personnel, issued several promotions, and one general and thirteen colonels were decorated. The draft age was lowered, the obligatory length of military duty was extended, and the age for reservists was increased to thirty-five years of age. In June, Assadullah Sarwari lost his seat in the PDPA Politburo, and in his place were appointed Mohammad Aslam Watanjar

Mohammad Aslam Watanjar ( ps, محمداسلم وطنجار, 1946 – November 2000) was an Afghanistan, Afghan general and politician. He played a significant role in the coup in 1978 that killed the Afghan president Mohammad Daud Khan and started ...

, a former tank commander and the then Minister of Communications, Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Mohammad Rafi

Mohammed Rafi (24 December 1924 – 31 July 1980) was an Indian playback singer and musician. He is considered to have been one of the greatest and most influential singers of the Indian subcontinent. Rafi was notable for his versatility and ...

, the Minister of Defence

A defence minister or minister of defence is a cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from country to country; in som ...

and KHAD

''Khadamat-e Aetla'at-e Dawlati'' (Pashto/ prs, خدمات اطلاعات دولتی literally "State Intelligence Agency", also known as "State Information Services"https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/482947db2.pdf or "Committee of State Security". U ...

Chairman Mohammad Najibullah

Mohammad Najibullah Ahmadzai (Pashto/ prs, محمد نجیبالله احمدزی, ; 6 August 1947 – 27 September 1996), commonly known as Dr. Najib, was an Afghan politician who served as the General Secretary of the People's Democratic Par ...

. These measures were introduced due to the collapse of the army; before the invasion the army could field 100,000 troops, after the invasion only 25,000. Desertion was pandemic, and the recruitment campaigns for young people often led them to flee to the opposition. To better organise the military, seven military zones were established, each with its own Defence Council. The Defence Council was established at the national, provincial and district level to devolve powers to the local PDPA. It is estimated that the Afghan government spent as much as 40 percent of government revenue on defence.

Karmal was forced to resign from his post as PDPA General Secretary in May 1985, due to increasing pressure from the Soviet leadership, and was succeeded by Najibullah, the former Minister of State Security. He continued to have influence in the upper echelons of the party and state until he was forced to resign from his post of Revolutionary Council Chairman in November 1986, being succeeded by Haji Mohammad Chamkani

Haji Mohammad Tsamkani ( ps, حاجي محمد څمکنی; prs, حاجی محمد چمکنی; 1920–2012 ) was an Afghan politician who held the post of interim President of Afghanistan during the period of the Soviet-backed Democratic Republic ...

, who was not a PDPA member.

Najibullah and Soviet withdrawal: 1986–1989

In September 1986 the National Compromise Commission (NCC) was established on the orders of Najibullah. The NCC's goal was to contactcounter-revolutionaries

A counter-revolutionary or an anti-revolutionary is anyone who opposes or resists a revolution, particularly one who acts after a revolution in order to try to overturn it or reverse its course, in full or in part. The adjective "counter-revoluti ...

"in order to complete the Saur Revolution in its new phase." An estimated 40,000 rebels were contacted by the government. At the end of 1986, Najibullah called for a six-month ceasefire and talks between the various opposition forces, as part of his policy of National Reconciliation

National Reconciliation is the term used for establishment of so-called 'national unity' in countries beset with political problems. In Afghanistan the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan government under Babrak Karmal issued a ten-point rec ...

. The discussions, if fruitful, would have led to the establishment of a coalition government and be the end of the PDPA's monopoly on power. The programme failed, but the government was able to recruit disillusioned mujahideen fighters as government militias. The National Reconciliation did lead an increasing number of urban dwellers to support his rule, and to the stabilisation of the Afghan defence forces.

While Najibullah may have been the ''

While Najibullah may have been the ''de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' ( ; , "by law") describes practices that are legally recognized, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. In contrast, ("in fact") describes situations that exist in reality, even if not legally ...

'' leader of Afghanistan, Soviet advisers still did most of the work after Najibullah took power. As Gorbachev remarked "We're still doing everything ourselves... That's all our people know how to do. They've tied Najibullah hand and foot." Fikryat Tabeev, the Soviet ambassador to Afghanistan, was accused of acting like a Governor General by Gorbachev, and he was recalled from Afghanistan in July 1986. But while Gorbachev called for the end of Soviet management of Afghanistan, he could not resist doing some managing himself. At a Soviet Politburo meeting, Gorbachev said, "It's difficult to build a new building out of old material... I hope to God that we haven't made a mistake with Najibullah." As time would prove, Najibullah's aims were the opposite of the Soviet Union's; Najibullah was opposed to a Soviet withdrawal, the Soviet Union wanted a withdrawal. This was understandable, since the Afghan military was on the brink of dissolution. Najibullah thought his only means of survival was to retain the Soviet presence. In July 1986 six Soviet regiments, up to 15,000 troops, were withdrawn from Afghanistan. The aim of this early withdrawal was, according to Gorbachev, to show the world that the Soviet leadership was serious about leaving Afghanistan. The Soviets told the United States Government that they were planning to withdraw, but the United States Government didn't believe it. When Gorbachev met with Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

during his visit the United States, Reagan called, bizarrely, for the dissolution of the Afghan army.

On 14 April the Afghan and Pakistani governments signed the 1988 Geneva Accords, and the Soviet Union and the United States signed as guarantors; the treaty specifically stated that the Soviet military had to withdraw from Afghanistan by 15 February 1989. During a Politburo meeting Eduard Shevardnadze

Eduard Ambrosis dze Shevardnadze ( ka, ედუარდ ამბროსის ძე შევარდნაძე}, romanized: ; 25 January 1928 – 7 July 2014) was a Soviet and Georgian politician and diplomat who governed Georgia fo ...

said "We will leave the country in a deplorable situation", and talked further about economic collapse, and the need to keep at least 10,000 to 15,000 troops in Afghanistan. Vladimir Kryuchkov

Vladimir Alexandrovich Kryuchkov (russian: Влади́мир Алекса́ндрович Крючко́в, link=no; 29 February 1924 – 23 November 2007) was a Soviet lawyer, diplomat, and head of the KGB, member of the Politburo of the ...

, the KGB Chairman, supported this position. This stance, if implemented, would be a betrayal of the Geneva Accords just signed. Najibullah was against any type of Soviet withdrawal. A few Soviet troops remained after the Soviet withdrawal; for instance, parachutists who protected the Soviet embassy staff, military advisors and special forces and reconnaissance troops still operated in the "outlying provinces", especially along the Afghan–Soviet border.

Fall: 1989–1992

Pakistan, underZia ul-Haq

General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq HI, GCSJ, ร.ม.ภ, (Urdu: ; 12 August 1924 – 17 August 1988) was a Pakistani four-star general and politician who became the sixth President of Pakistan following a coup and declaration of martial law i ...

, continued to support the Afghan mujahideen even though it was a contravention of the Geneva Accords. At the beginning most observers expected the Najibullah government to collapse immediately, and to be replaced with an Islamic fundamentalist government. The Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

stated in a report, that the new government would be ambivalent, or even worse hostile, towards the United States. Almost immediately after the Soviet withdrawal, the Battle of Jalalabad was fought between Afghan government forces and the mujahideen; the government forces, to the surprise of many, repulsed the attack and won the battle. This trend would not continue, and by the summer of 1990, the Afghan government forces were on the defensive again. By the beginning of 1991, the government controlled only 10 percent of Afghanistan, the eleven-year Siege of Khost had ended in a mujahideen victory and the morale of the Afghan military finally collapsed. The Soviet Union was falling apart itself; and thus hundreds of millions of dollars of yearly economic aid to Najibullah's government from Moscow dried up.

In March 1992, Najibullah offered his government's immediate resignation, and following an agreement with the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

(UN), his government was replaced by an interim government. In mid-April Najibullah accepted a UN plan to hand power to a seven-man council. A few days later, on 14 April, Najibullah was forced to resign on the orders of the Watan Party, because of the loss of Bagram airbase and the town of Charikar

Imam Abu Hanifa ( fa, امام ابو حنیفه), historically known as Charikar (Persian: چاریکار) but renamed by Talibans recently to Imam Abu Hanifa, is the main town of the Koh Daman Valley and the capital of Parwan Province in northe ...

. Abdul Rahim Hatef

Abdul Rahim Hatif ( ps, عبدالرحیم هاتف; 20 May 1926 – 19 August 2013) was a politician in Afghanistan. He served as one of the vice presidents during the last years of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan. He was born in Kandah ...

became acting head of state following Najibullah's resignation. Najibullah, not long before Kabul's fall, appealed to the UN for amnesty, which he was granted. But Najibullah was hindered by Abdul Rashid Dostum

Abdul Rashid Dostum ( ; prs, عبدالرشید دوستم; Uzbek Latin: , Uzbek Cyrillic: , ; born 25 March 1954) is an Afghan exiled politician, former Marshal in the Afghan National Army, founder and leader of the political party Junbish- ...

from escaping; instead, Najibullah sought haven in the local UN headquarters in Kabul. The war in Afghanistan

War in Afghanistan, Afghan war, or Afghan civil war may refer to:

*Conquest of Afghanistan by Alexander the Great (330 BC – 327 BC)

* Muslim conquests of Afghanistan (637–709)

*Conquest of Afghanistan by the Mongol Empire (13th century), see al ...

did not end with Najibullah's ouster, and continued until the final fall of Kabul to the Taliban

The Taliban (; ps, طالبان, ṭālibān, lit=students or 'seekers'), which also refers to itself by its state name, the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a Deobandi Islamic fundamentalist, militant Islamist, jihadist, and Pasht ...

in August 2021.

Politics

Political system

The People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan described the Saur Revolution as a democratic revolution signifying "a victory of the honourable working people of Afghanistan" and the "manifestation of the real will and interests of workers, peasants and toilers." While the idea of moving Afghanistan toward socialism was proclaimed, completing the task was seen as an arduous road. Thus, Afghanistan's foreign minister commented that Afghanistan was a democratic but not yet socialist republic, while a member of thePolitburo of the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan

The Politburo of the Central Committee of the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) or Afghan Politburo was the policy-making organ and institution within the Afghanistan's political structure when the PDPA Central Committee and the PDP ...

predicted that "Afghanistan will not see socialism in my lifetime" in an interview with a British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

journalist in 1981.

Afghanistan was considered by the Soviet Union as a state with a socialist orientation. The Soviets, in mid-1979, initially proclaimed Afghanistan as not merely a progressive ally, but a fully fledged member of the socialist community of nations. In contrast, later Soviet rhetoric invariably referred to the Saur Revolution as a democratic turn, but stopped short of recognizing a socialist society.

Under Hafizullah Amin

Hafizullah Amin (Pashto/ prs, حفيظ الله امين; 1 August 192927 December 1979) was an Afghan communist revolutionary, politician and teacher. He organized the Saur Revolution of 1978 and co-founded the Democratic Republic of Afghan ...

, a commission working on a new constitution was established. There were 65 members of this commission, and they came from all walks of life. Due to his death, his constitution was never finished. In April 1980, under Babrak Karmal

Babrak Karmal (Farsi/ Pashto: , born Sultan Hussein; 6 January 1929 – 1 or 3 December 1996) was an Afghan revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Afghanistan, serving in the post of General Secretary of the People's Democratic Pa ...

, the Fundamental Principles of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan were made law. The constitution was devoid of any references to socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

or communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

, and instead laid emphasis on independence, Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

and liberal democracy

Liberal democracy is the combination of a liberal political ideology that operates under an indirect democratic form of government. It is characterized by elections between multiple distinct political parties, a separation of powers into ...

. Religion was to be respected, the exception being when religion threatened the security of society. The Fundamental Principles were, in many ways, similar to Mohammad Daoud Khan

Mohammed Daoud Khan ( ps, ), also romanized as Daud Khan or Dawood Khan (18 July 1909 – 28 April 1978), was an Afghan politician and general who served as prime minister of Afghanistan from 1953 to 1963 and, as leader of the 1973 Afghan coup ...

's 1977 constitution. While official ideology was de-emphasized, the PDPA did not lose its monopoly on power, and the Revolutionary Council

A workers' council or labor council is a form of political and economic organization in which a workplace or municipality is governed by a council made up of workers or their elected delegates. The workers within each council decide on what thei ...

continued to be ruled through its Presidium, the majority of Presidium members were from the PDPA Politburo. The Karmal government was "a new evolutionary phase of the great Saur Revolution." The Fundamental Principles was not implemented in practice, and it was replaced by the 1987 constitution in a ''loya jirga

A jirga ( ps, جرګه, ''jərga'') is an assembly of leaders that makes decisions by consensus according to Pashtunwali, the Pashtun social code. It is conducted in order to settle disputes among the Pashtuns, but also by members of other ethnic ...

'' under Muhammad Najibullah

Mohammad Najibullah Ahmadzai (Pashto/ prs, محمد نجیبالله احمدزی, ; 6 August 1947 – 27 September 1996), commonly known as Dr. Najib, was an Afghan politician who served as the General Secretary of the People's Democratic P ...

but did not have support of opposition parties. Islamic principles were embedded in the 1987 constitution. For instance, Article 2 of the constitution stated that Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

was the state religion, and Article 73 stated that the head of state had to be born into a Muslim Afghan family. In 1990, the 1987 constitution was amended to state that Afghanistan was an Islamic republic, and the last references to communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

were removed. Article 1 of the amended constitution said that Afghanistan was an "independent, unitary and Islamic state."

The 1987 constitution liberalized the political landscape in areas under government control. Political parties could be established as long as they opposed colonialism

Colonialism is a practice or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, often by establishing colony, colonies and generally with the aim of economic dominance. In the process of colonisation, colonisers may impose the ...

, imperialism

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic and ...

, neo-colonialism

Neocolonialism is the continuation or reimposition of imperialist rule by a state (usually, a former colonial power) over another nominally independent state (usually, a former colony). Neocolonialism takes the form of economic imperialism, g ...

, Zionism

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after '' Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in Je ...

, racial discrimination

Racial discrimination is any discrimination against any individual on the basis of their skin color, race or ethnic origin.Individuals can discriminate by refusing to do business with, socialize with, or share resources with people of a certain g ...

, apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

and fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy an ...

. The Revolutionary Council was abolished, and replaced by the National Assembly of Afghanistan

The National Assembly ( ps, , Mili Shura, prs, , Shura-e Milli), also known as the Parliament of Afghanistan or simply as the Afghan Parliament, was the legislature of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. It was effectively dissolved when the ...

, a democratically elected parliament. The government announced its willingness to share power, and form a coalition government. The new parliament was bicameral, and consisted of a Senate (Sena) and a House of Representatives (Wolesi Jirga

The House of Representatives of the People, or Da Afghanistan Wolesi Jirga ( ps, دَ افغانستان ولسي جرګه), was the lower house of the bicameral National Assembly of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, alongside the upper ...

). The president was to be indirectly elected to a 7-year term. A parliamentary election was held in 1988. The PDPA won 46 seats in the House of Representatives and controlled the government with support from the National Front, which won 45 seats, and from various newly recognized left-wing parties, which had won a total of 24 seats. Although the election was boycotted by the Mujahideen, the government left 50 of the 234 seats in the House of Representatives, as well as a small number of seats in the Senate, vacant in the hope that the guerillas would end their armed struggle and participate in the government. The only armed opposition party to make peace with the government was Hizbollah, a small Shi'a

Shīʿa Islam or Shīʿīsm is the second-largest Islamic schools and branches, branch of Islam. It holds that the Prophets and messengers in Islam, Islamic prophet Muhammad in Islam, Muhammad designated Ali, ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib as his S ...

party not to be confused with the bigger party in Iran.

The Council of Ministers

A council is a group of people who come together to consult, deliberate, or make decisions. A council may function as a legislature, especially at a town, city or county/ shire level, but most legislative bodies at the state/provincial or nati ...

was the Afghan cabinet, and its chairman was the head of government. It was the most important government body in PDPA Afghanistan, and it ran the governmental ministries. The Council of Ministers was responsible to the Presidium of the Revolutionary Council, and after the adoption of the 1987 constitution, to the President and House of Representatives. There seems to have been a deliberate power-sharing between the two bodies; few Presidium members were ministers. It was the PDPA (perhaps with the involvement of the Soviets) which appointed and decided the membership of the Council of Ministers. An Afghan dissident who had previously worked in the office of the Chairman of the Council of Ministers reported that all topics up for discussion in the Council of Ministers had to be approved by the Soviets. Under Karmal, the Khalqist's were purged and replaced by the Parcham majority in the Council of Ministers. Of the 24 members of the Council of Ministers under Karmal's chairmanship, only four were Khalqists.

People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan

Leninist

Leninism is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary vanguard party as the political prelude to the establishm ...

party model; the party was based on the principles of democratic centralism and Marxism–Leninism

Marxism–Leninism is a communist ideology which was the main communist movement throughout the 20th century. Developed by the Bolsheviks, it was the state ideology of the Soviet Union, its satellite states in the Eastern Bloc, and various co ...

was the party's official ideology. In theory, the Central Committee of the PDPA ruled Afghanistan by electing the members to the Revolutionary Council

A workers' council or labor council is a form of political and economic organization in which a workplace or municipality is governed by a council made up of workers or their elected delegates. The workers within each council decide on what thei ...

, Secretariat, and the Politburo of the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan

The Politburo of the Central Committee of the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) or Afghan Politburo was the policy-making organ and institution within the Afghanistan's political structure when the PDPA Central Committee and the PDP ...

, the key decision-making bodies of state and party. After the Soviet intervention, the powers of the PDPA decreased because of the government's increased unpopularity amongst the masses. Soviet advisers took over nearly all aspects of Afghan administration; according to critics, the Afghans became the advisors and the Soviet became the advised. The Soviet intervention had forced Karmal upon the party and state. While trying to portray the new government as a Khalq

Khalq ( ps, خلق, ) was a faction of the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA). Its historical ''de facto'' leaders were Nur Muhammad Taraki (1967–1979), Hafizullah Amin (1979) and Sayed Mohammad Gulabzoy (1979–1990). It was als ...

–Parcham

Parcham (Pashto and prs, پرچم, ) was the name of one of the factions of the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan, formed in 1967 following its split and led for most of its history by Babrak Karmal and Mohammed Najibullah. The basic id ...

coalition, most members (the majority of whom were Khalqists), saw through the lies. At the time of the Parchamite takeover of the state and party, an estimated 80 percent of military officers were Khalqists.

In the party's history, only two congresses were held; the founding congress in 1965 and the Second Congress in June 1990, which transformed the PDPA into the Watan Party, which has survived to this today in the shape of the Democratic Watan Party

The Watan Party of Afghanistan ( prs, حزب وطن افغانستان, ''Hezeb-e Vâtân-e Afqanustan'') is a Social democracy, social democratic List of political parties in Afghanistan, political party in Afghanistan. The party describes itse ...

. The Second Congress renamed the party and tried to revitalise it by admitting to past mistakes and evolving ideologically. The policy of national reconciliation

National Reconciliation is the term used for establishment of so-called 'national unity' in countries beset with political problems. In Afghanistan the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan government under Babrak Karmal issued a ten-point rec ...

was given a major ideologically role, since the party now looked for a peaceful solution to the conflict; class struggle was still emphasised. The party also decided to support and further develop the market economy in Afghanistan.

=Factions

= * The Khalq faction was the more militant of the two. It was more revolutionary and believed in a purer form of Marxism–Leninism than did the Parcham. Following the Soviet intervention, the Khalqi leadership of Taraki and Amin had been all but driven out. Several low and middle level functionaries were still present in the PDPA, and they still formed a majority within the armed forces; the Khalq faction still managed to create a sense of cohesion. While still believing in Marxism–Leninism, many of them were infuriated at the Soviet intervention, and the Soviets' pro-Parchamite policies. Taraki, in a speech, said "We will defend our non-aligned policy and independence with all valour. We will not give even an inch of soil to anyone and we will not be dictated in our foreign policy orwill we accept anybody's orders in this regard." While it was not clear, who Taraki was pointing at, the Soviet Union was the only country which Afghanistan neighbored which had the strength to occupy the country.Adolph Dubs

Adolph Dubs (August 4, 1920 – February 14, 1979), also known as Spike Dubs, was an American diplomat who served as the United States Ambassador to Afghanistan from May 13, 1978, until his death in 1979. He was killed during a rescue attem ...

, the United States Ambassador to Afghanistan

The United States ambassador to Afghanistan is the official diplomatic representative of the United States to Afghanistan. In the wake of the 2021 fall of Kabul to the Taliban, the U.S. Embassy in Kabul transferred operations to Doha, Qatar. S ...

. Ideologically Settam-e-Melli was very close to the Khalqist faction, but Settam-e-Melli opposed what they saw as the Khalq faction's "Pashtun chauvinism." Settam-e-Melli followed the ideology of Maoism

Maoism, officially called Mao Zedong Thought by the Chinese Communist Party, is a variety of Marxism–Leninism that Mao Zedong developed to realise a socialist revolution in the agricultural, pre-industrial society of the Republic of Ch ...

. When Karmal ascended to power, the Settamites relationship with the government improved, mostly due to Karmal's former good relationship with Badakhshi, who was killed by government forces in 1979. In 1983, Bashir Baghlani, a Settam-e-Melli member, was appointed Minister of Justice

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a ...

.

National Front

Karmal had first mentioned the possibility of establishing a "broad national front" in March 1980, but given the situation the country was in, the campaign for the establishment of such an organisation began only in January 1981. A "spontaneous" demonstration in support of establishing such an organisation was held that month. The first pre-front institution to be established was a tribal jirga in May 1981 by the Ministry of Tribal Affairs. This jirga later became a member of the front. The National Fatherland Front (NFF) held its founding congress in June 1981, after being postponed on several occasions. The founding congress, which was planned to last four days, lasted only one. Within one month of its founding, 27 senior members had been assassinated by the mujahideen. Due to this, the organisation took time to establish itself; its first Provincial Committee was established in November, and its first jirga in December. It was not until 1983 that the NFF became an active, and important organisation. The aim of the NFF was to establish a pro-PDPA organisation for those who did not support the PDPA ideologically. Its first leader was Salah Mohammad Zeary, a prominent politician within the PDPA. Zeary's selection had wider implications: the PDPA dominated all NFF activities. Officially, the NFF had amassed 700,000 members after its founding, which later increased to one million. The majority of its members were already members of affiliated organisations, such as the Women's Council, the Democratic Youth Organisation and the trade unions, all of which were controlled by the PDPA. The membership numbers were in any case inflated: actually in 1984 the NFF had 67,000 members, and in 1986 its membership peaked at 112,209. In 1985 Zeary stepped down as NFF leader, and was succeeded byAbdul Rahim Hatef

Abdul Rahim Hatif ( ps, عبدالرحیم هاتف; 20 May 1926 – 19 August 2013) was a politician in Afghanistan. He served as one of the vice presidents during the last years of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan. He was born in Kandah ...

, who was not a member of the PDPA. The ascension of Hatef proved more successful, and in 1985–86 the NFF succeeded in recruiting several "good Muslims". The NFF was renamed the National Front in 1987.

Symbols: flag and emblem

On 19 October 1978 the PDPA government introduced a new flag, a red flag with a yellow seal, and it was similar to the flags of theSoviet Central Asia

Soviet Central Asia (russian: link=no, Советская Средняя Азия, Sovetskaya Srednyaya Aziya) was the part of Central Asia administered by the Soviet Union between 1918 and 1991, when the Central Asian republics declared ind ...

n republics. The new flag stirred popular resentment, as many Afghans saw it as proof of the PDPA government's attempt to introduce state atheism

State atheism is the incorporation of positive atheism or non-theism into political regimes. It may also refer to large-scale secularization attempts by governments. It is a form of religion-state relationship that is usually ideologically li ...

. It was shown to the public for the first time in an official rally in Kabul. The red flag introduced under Taraki was replaced in 1980, shortly after the Soviet intervention, to the more traditional colours black, red and green. The PDPA flag, which was red with a yellow seal, was retained to emphasise the difference between the party and state to the Afghan people. The red star, the book and communist symbols in general, were removed from the flag in 1987 under Najibullah.

The new emblem, which replaced Daoud's eagle emblem, was introduced together with the flag in 1978. When Karmal introduced a new emblem in 1980, he said "it is from the pulpit that thousands of the faithful are led to the right path." The book depicted in the emblem (and the flag) was generally considered to be ''Das Kapital

''Das Kapital'', also known as ''Capital: A Critique of Political Economy'' or sometimes simply ''Capital'' (german: Das Kapital. Kritik der politischen Ökonomie, link=no, ; 1867–1883), is a foundational theoretical text in materialist phi ...

'', a work by Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

, and not the ''Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Classical Arabic, Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation in Islam, revelation from God in Islam, ...

'', the central Islamic text. The last emblem was introduced in 1987 by the Najibullah government. This emblem was, in contrast to the previous ones, influenced by Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

. The Red Star and ''Das Kapital'' were removed from the emblem (and the flag). The emblem depicted the mihrab, the minbar and the shahada

The ''Shahada'' (Arabic: ٱلشَّهَادَةُ , "the testimony"), also transliterated as ''Shahadah'', is an Islamic oath and creed, and one of the Five Pillars of Islam and part of the Adhan. It reads: "I bear witness that there is n ...

, an Islamic creed.

Economy

Taraki's Government initiated aland reform

Land reform is a form of agrarian reform involving the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution, generally of agricultural ...

on 1 January 1979, which attempted to limit the amount of land a family could own. Those whose landholdings exceeded the limit saw their property requisitioned by the government without compensation. The Afghan leadership believed the reform would meet with popular approval among the rural population while weakening the power of the bourgeoisie. The reform was declared complete in mid-1979 and the government proclaimed that 665,000 hectares (approximately 1,632,500 acres) had been redistributed. The government also declared that only 40,000 families, or 4 percent of the population, had been negatively affected by the land reform.

Contrary to government expectations the reform was neither popular nor productive. Agricultural harvests plummeted and the reform itself led to rising discontent amongst Afghans. When Taraki realized the degree of popular dissatisfaction with the reform he quickly abandoned the policy. However, the land reform was gradually implemented under the later Karmal administration, although the proportion of land area affected by the reform is unclear.

During the civil war, and the ensuing Soviet–Afghan War

The Soviet–Afghan War was a protracted armed conflict fought in the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan from 1979 to 1989. It saw extensive fighting between the Soviet Union and the Afghan mujahideen (alongside smaller groups of anti-Soviet ...

, most of the country's infrastructure was destroyed, and normal patterns of economic activity were disrupted. The gross national product

The gross national income (GNI), previously known as gross national product (GNP), is the total domestic and foreign output claimed by residents of a country, consisting of gross domestic product (GDP), plus factor incomes earned by foreign ...

(GNP) fell substantially during Karmal's rule because of the conflict; trade and transport were disrupted along with the loss of labor and capital. In 1981 the Afghan GDP stood at 154.3 billion Afghan afghani

The afghani ( sign: or Af (plural: Afs) code: AFN; Pashto: ; Persian : ) is the currency of Afghanistan, which traditionally is issued by the nation's central bank called Da Afghanistan Bank. It is nominally subdivided into 100 '' puls'' (پ� ...

s, a drop from 159,7 billion in 1978. GNP per capita

A variety of measures of national income and output are used in economics to estimate total economic activity in a country or region, including gross domestic product (GDP), gross national product (GNP), net national income (NNI), and adjusted na ...

decreased from 7,370 in 1978 to 6,852 in 1981. The most dominant form of economic activity was the agricultural sector. Agriculture accounted for 63 percent of gross domestic product

Gross domestic product (GDP) is a money, monetary Measurement in economics, measure of the market value of all the final goods and services produced and sold (not resold) in a specific time period by countries. Due to its complex and subjec ...

(GDP) in 1981; 56 percent of the labour force worked in agriculture in 1982. Industry accounted for 21 percent of GDP in 1982, and employed 10 percent of the labour force. All industrial enterprises were government-owned

State ownership, also called government ownership and public ownership, is the ownership of an industry, asset, or enterprise by the state or a public body representing a community, as opposed to an individual or private party. Public ownersh ...

. The service sector, the smallest of the three, accounted for 10 percent of GDP in 1981, and employed an estimated one-third of the labour force. The balance of payments, which had improved in the pre-communist administration of Muhammad Daoud Khan; the surplus decreased and became a deficit by 1982, which reached minus $US70.3 million. The only economic activity that grew substantially during Karmal's rule was export

An export in international trade is a good produced in one country that is sold into another country or a service provided in one country for a national or resident of another country. The seller of such goods or the service provider is an ...

and import.

Najibullah continued Karmal's economic policies. The augmenting of links with the Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

and the Soviet Union continued, as did bilateral trade. He also encouraged the development of the private sector in industry. The Five-Year Economic and Social Development Plan, which was introduced in January 1986, continued until March 1991, one month before the government's fall. According to the plan, the economy, which had grown less than 2 percent annually until 1985, would grow 25 percent under the plan. Industry would grow 28 percent, agriculture 14–16 percent, domestic trade by 150 percent and foreign trade by 15 percent. None of these predictions were successful, and economic growth continued at 2%. The 1990 constitution gave attention to the private sector

The private sector is the part of the economy, sometimes referred to as the citizen sector, which is owned by private groups, usually as a means of establishment for profit or non profit, rather than being owned by the government.

Employment

The ...

. Article 20 covered the establishment of private firms, and Article 25 encouraged foreign investment in the private sector.

Military

Command and officer corps

The army's chain of command began with the Supreme Commander, who also held the posts of PDPA General Secretary and head of state. Theorder of precedence

An order of precedence is a sequential hierarchy of nominal importance and can be applied to individuals, groups, or organizations. Most often it is used in the context of people by many organizations and governments, for very formal and state o ...

continued with the Minister of National Defense

A defence minister or minister of defence is a cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from country to country; in som ...

, the Deputy Minister of National Defence, Chief of the General Staff, Chief of Army Operations, Air and Air Defence Commander and ended with the Chief of Intelligence.

Of the 8,000 strong officer corps in 1978, between 600 and 800 were communists. An estimated 40 to 45 percent of these officers were educated in the Soviet Union, and of them, between 5 and 10 percent were members of the PDPA or communists. By the time of the Soviet intervention, the officer corps had decreased to 1,100 members. This decrease can be explained by the number of purges centered on the armed forces. The purge of the military began immediately after the PDPA took power. According to Mohammad Ayub Osmani, an officer who defected to the enemy, of the 282 Afghan officers who attended the Malinovsky Military Armored Forces Academy

The Malinovsky Military Armored Forces Academy (Военная академия бронетанковых войск имени Маршала Советского Союза Р. Я. Малиновского) was one of the Soviet military academ ...

in Moscow, an estimated 126 were executed by the authorities. Most of the officer corps, during the Soviet war and the ensuing civil war, were new recruits. The majority of officers were Khalqists, but after the Parchamites' ascension to power, Khalqists held no position of significance. The Parchamites, who were the minority, held the positions of power. Of the 1,100 large officer corps, only an estimated 200 were party members. According to Abdul Qadir, one-fifth of military personnel were party members, which meant that, if the military stood at 47,000, 9,000 were members of the PDPA. This number was, according to J. Bruce Amtstutz, an exaggeration.

Branches

Army

The strength of the army was greatly weakened during the early stages of PDPA rule. One of the main reasons for the small size was that the Soviet military were afraid the Afghan army would defect ''

The strength of the army was greatly weakened during the early stages of PDPA rule. One of the main reasons for the small size was that the Soviet military were afraid the Afghan army would defect ''en masse