Slavery In Colombia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Slavery was practiced in

The enslavement of indigenous peoples in what is now Colombia began with the colonization of the country by the Spanish in the early 16th century, and with the creation of the Viceroyalty of New Granada in 1717. With the advance of the

The enslavement of indigenous peoples in what is now Colombia began with the colonization of the country by the Spanish in the early 16th century, and with the creation of the Viceroyalty of New Granada in 1717. With the advance of the

The Iberian slave trade in Africa began with the Portuguese, who transported prisoners to the Madeira Islands and the Azores. Through the Treaty of Alcáçovas, in 1479 the Kingdom of Castile recognized the Portuguese primacy in the African slave trade, which would make them the main providers of enslaved labor for centuries to come. This reached a new dimension with the colonization of the New World, since the subjugated native population was insufficient for the exploitation of natural resources and their number was reduced day by day either because of the spread of disease or death from abuse by Spaniards. Thus, the massive trafficking of African slaves to the provinces that would be the Viceroyalty of New Granada would begin only after the indigenous population was decimated, beginning in the second half of the 16th century. This trafficking occurred through ''licencias,'' a kind of contract with the state in which the crown authorized the slave trade to the colonies in exchange for a tax contribution.

The slave trade was morally justified under the idea that the slave received the "invaluable" evangelizing work of his master, and that the

The Iberian slave trade in Africa began with the Portuguese, who transported prisoners to the Madeira Islands and the Azores. Through the Treaty of Alcáçovas, in 1479 the Kingdom of Castile recognized the Portuguese primacy in the African slave trade, which would make them the main providers of enslaved labor for centuries to come. This reached a new dimension with the colonization of the New World, since the subjugated native population was insufficient for the exploitation of natural resources and their number was reduced day by day either because of the spread of disease or death from abuse by Spaniards. Thus, the massive trafficking of African slaves to the provinces that would be the Viceroyalty of New Granada would begin only after the indigenous population was decimated, beginning in the second half of the 16th century. This trafficking occurred through ''licencias,'' a kind of contract with the state in which the crown authorized the slave trade to the colonies in exchange for a tax contribution.

The slave trade was morally justified under the idea that the slave received the "invaluable" evangelizing work of his master, and that the

Abolition was a gradual process. Manumission of enslaved individuals occurred throughout the history of the colony, but the abolition of slavery as an institution was not seriously considered until the Napoleonic invasion of Spain, when, beginning in 1809, the question of freedom was raised in the Iberian courts to prevent "slaves from seeking and even achieving it by violent and coercive means".

Abolition was a gradual process. Manumission of enslaved individuals occurred throughout the history of the colony, but the abolition of slavery as an institution was not seriously considered until the Napoleonic invasion of Spain, when, beginning in 1809, the question of freedom was raised in the Iberian courts to prevent "slaves from seeking and even achieving it by violent and coercive means".

Colombia

Colombia (, ; ), officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country in South America with insular regions in North America—near Nicaragua's Caribbean coast—as well as in the Pacific Ocean. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Car ...

from the beginning of the 16th century until its definitive abolition in 1851. This process consisted of trafficking in people of African

African or Africans may refer to:

* Anything from or pertaining to the continent of Africa:

** People who are native to Africa, descendants of natives of Africa, or individuals who trace their ancestry to indigenous inhabitants of Africa

*** Ethn ...

and indigenous origin, first by the European colonizers from Spain and later by the commercial elites of the Republic of New Granada, the country that contained what is present-day Colombia.

Indigenous slavery

The enslavement of indigenous peoples in what is now Colombia began with the colonization of the country by the Spanish in the early 16th century, and with the creation of the Viceroyalty of New Granada in 1717. With the advance of the

The enslavement of indigenous peoples in what is now Colombia began with the colonization of the country by the Spanish in the early 16th century, and with the creation of the Viceroyalty of New Granada in 1717. With the advance of the Conquistador

Conquistadors (, ) or conquistadores (, ; meaning 'conquerors') were the explorer-soldiers of the Spanish and Portuguese Empires of the 15th and 16th centuries. During the Age of Discovery, conquistadors sailed beyond Europe to the Americas, O ...

s, the defeated indigenous peoples were subjected to slavery as prisoners of war, as was the Spanish custom. For example, Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada

Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada y Rivera, also spelled as Ximénez and De Quezada, (;1496 16 February 1579) was a Spanish explorer and conquistador in northern South America, territories currently known as Colombia. He explored the territory named ...

distributed some eighteen thousand conquered prisoners among his captains and soldiers. This process would continue without any state intervention or legal justification until the expedition of the Laws of Burgos by the Spanish crown, which abolished the slavery of indigenous peoples in 1512 ''de'' ''jure''. The legal status of the conquered American population would be improved again by the New Laws

The New Laws (Spanish: ''Leyes Nuevas''), also known as the New Laws of the Indies for the Good Treatment and Preservation of the Indians (Spanish: ''Leyes y ordenanzas nuevamente hechas por su Majestad para la gobernación de las Indias y buen t ...

of 1542, which would establish new protections for them.

These protections, however, should not be construed as a '' de facto'' abolition of Amerindians slavery. Among the Spanish colonizers of that time, an aphorism arose, "we obey, but do not comply", which comes from an administrative formula used in the Courts of Castile to pause the execution of a law or government mandate, pending revision by the monarch, because the disposition is considered unjust or contradictory of existing dispositions by the legislative body. The slavery of the native peoples would continue on the margin of the law, with the conquered being frequently subjected to the same treatment by the Spanish.

Beyond the informal practice of slavery, forced labor would continue even within the framework of the law, with institutions known as the mita Mita or MITA can refer to:

*Mita (name)

*''Mit'a'' or ''mita'', a form of public service in the Inca Empire and later in the Viceroyalty of Peru

* Mita, Meguro, Tokyo, a neighborhood in Tokyo, Japan

* Mita, Minato, Tokyo, a neighborhood in Tokyo, J ...

and the encomienda

The ''encomienda'' () was a Spanish labour system that rewarded conquerors with the labour of conquered non-Christian peoples. The labourers, in theory, were provided with benefits by the conquerors for whom they laboured, including military ...

. The new regulations, as well as the Laws of Burgos, still contemplated forced labor and, although this was not formally the very institution of slavery, it was not far from it. The mita established labor quotas that the native population had to fulfill as a tribute according to the assignment made by the corregidor. The encomienda was a form of clientelism

Clientelism or client politics is the exchange of goods and services for political support, often involving an implicit or explicit quid-pro-quo. It is closely related to patronage politics and vote buying. Clientelism involves an asymmetric rel ...

in which the indigenous people were forced to pay an encomendero the services supposedly provided by the same. The main service that the encomendero had to render as contemplated by colonial legislation was evangelization, but even in this there was negligence. For example, around the 16th century, there was only one encomendero mudbrick church in all Santa Fe de Bogotá

Santa Claus, also known as Father Christmas, Saint Nicholas, Saint Nick, Kris Kringle, or simply Santa, is a legendary figure originating in Western Christian culture who is said to bring children gifts during the late evening and overnight ...

. Meanwhile, in Tunja, the encomenderos not only neglected their duty to educate but actively sabotaged it, strongly opposing indigenous people learning to read and write.

The application of the New Laws

The New Laws (Spanish: ''Leyes Nuevas''), also known as the New Laws of the Indies for the Good Treatment and Preservation of the Indians (Spanish: ''Leyes y ordenanzas nuevamente hechas por su Majestad para la gobernación de las Indias y buen t ...

of 1542 was suspended and with it, the legislation's intention to strip power away from private encomenderos. By 1545, the New Laws repealed the inheritability of encomiendas, weakening encomenderos by dissolving their grant upon their deaths, again allowing the viceroys and governors to establish new encomiendas. This reached a new dimension with the colonization of the New World, since the subjugated native population was insufficient for the exploitation of natural resources and their number was reduced, either because of the spread of disease or death from abuse by Europeans. Thus the massive trafficking of African slaves to the provinces that would be the New Granada New Granada may refer to various former national denominations for the present-day country of Colombia.

*New Kingdom of Granada, from 1538 to 1717

*Viceroyalty of New Granada, from 1717 to 1810, re-established from 1816 to 1819

*United Provinces of ...

would begin only after the indigenous population was decimated, in the second half of the 16th century. This trafficking occurred through the so-called ''licenses,'' a kind of contract with the state in which the crown authorized the slave trade to the colonies in exchange for a tax contribution.

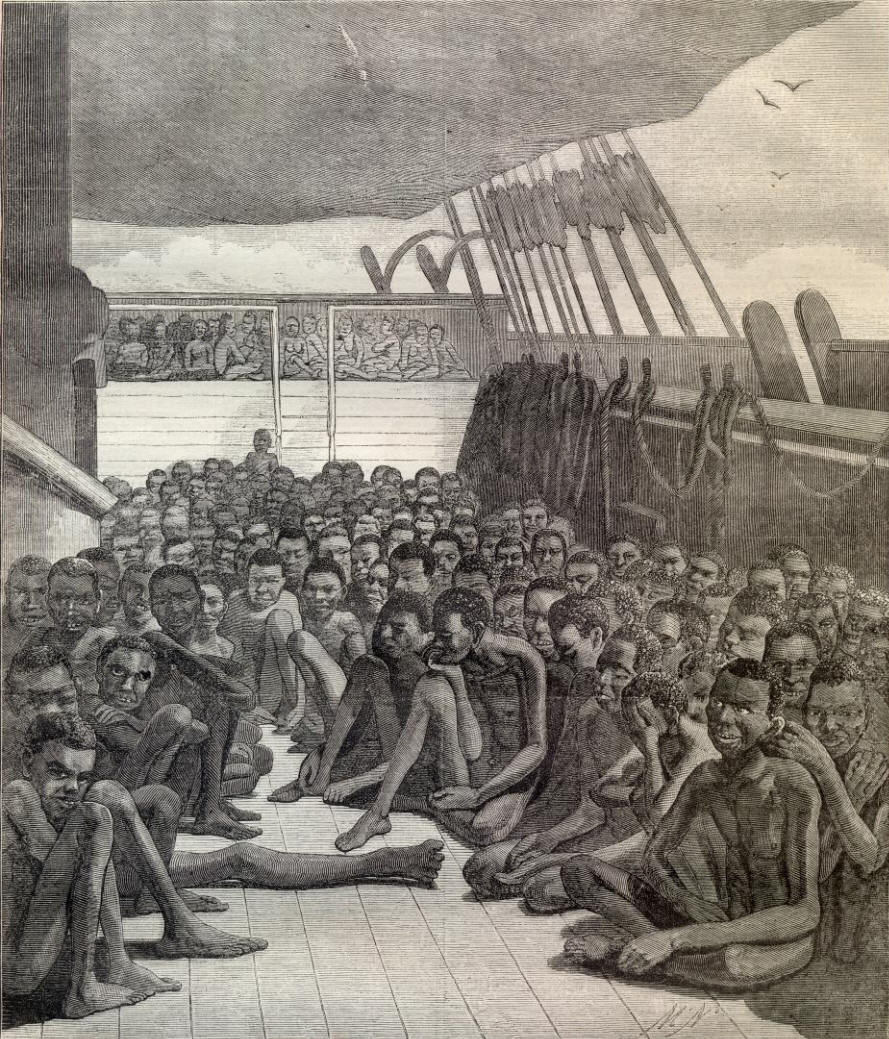

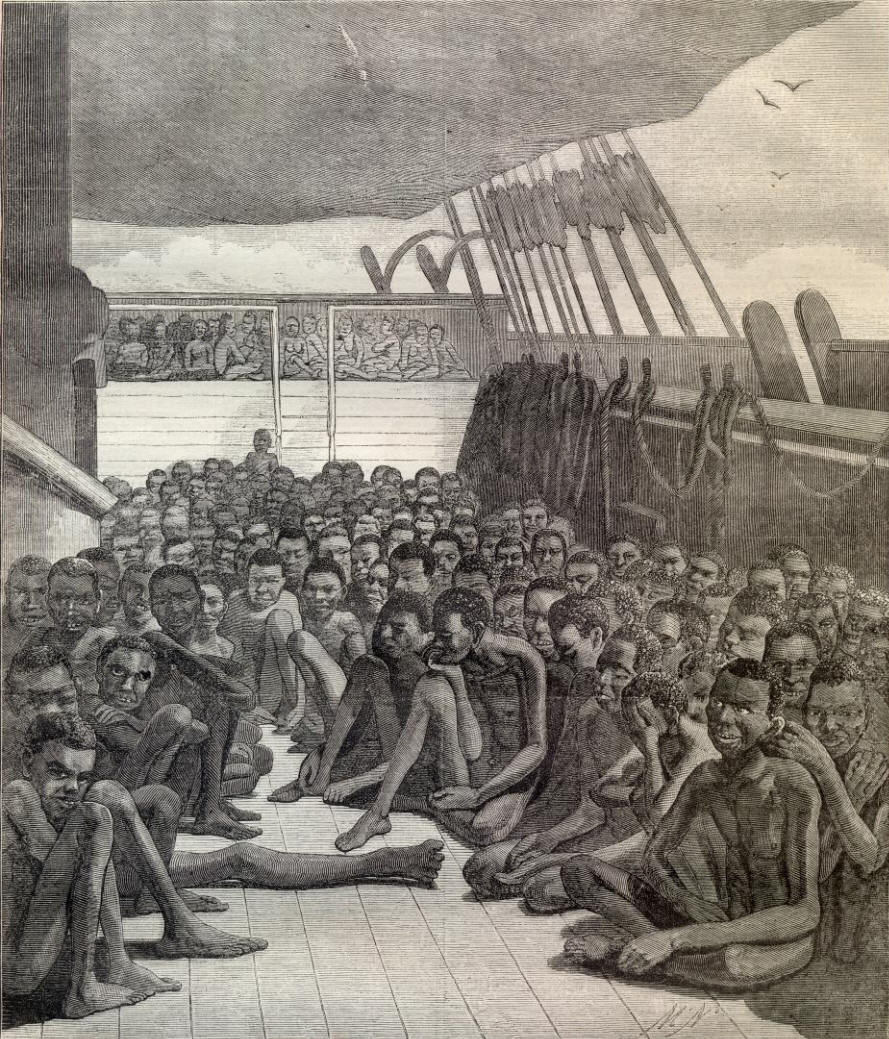

The slave trade was morally justified under the idea that the slave received the "invaluable" evangelizing work of his master, and that the Christian principle of equality referred to equality in the hereafter and the superiority of the white man in the present. This did not prevent slaves from being transported in subhuman conditions; the journey from Africa to America lasted about two months and was carried out on overcrowded, disease-ridden ships, with poor or no ventilation.

African slavery

The Iberian slave trade in Africa began with the Portuguese, who transported prisoners to the Madeira Islands and the Azores. Through the Treaty of Alcáçovas, in 1479 the Kingdom of Castile recognized the Portuguese primacy in the African slave trade, which would make them the main providers of enslaved labor for centuries to come. This reached a new dimension with the colonization of the New World, since the subjugated native population was insufficient for the exploitation of natural resources and their number was reduced day by day either because of the spread of disease or death from abuse by Spaniards. Thus, the massive trafficking of African slaves to the provinces that would be the Viceroyalty of New Granada would begin only after the indigenous population was decimated, beginning in the second half of the 16th century. This trafficking occurred through ''licencias,'' a kind of contract with the state in which the crown authorized the slave trade to the colonies in exchange for a tax contribution.

The slave trade was morally justified under the idea that the slave received the "invaluable" evangelizing work of his master, and that the

The Iberian slave trade in Africa began with the Portuguese, who transported prisoners to the Madeira Islands and the Azores. Through the Treaty of Alcáçovas, in 1479 the Kingdom of Castile recognized the Portuguese primacy in the African slave trade, which would make them the main providers of enslaved labor for centuries to come. This reached a new dimension with the colonization of the New World, since the subjugated native population was insufficient for the exploitation of natural resources and their number was reduced day by day either because of the spread of disease or death from abuse by Spaniards. Thus, the massive trafficking of African slaves to the provinces that would be the Viceroyalty of New Granada would begin only after the indigenous population was decimated, beginning in the second half of the 16th century. This trafficking occurred through ''licencias,'' a kind of contract with the state in which the crown authorized the slave trade to the colonies in exchange for a tax contribution.

The slave trade was morally justified under the idea that the slave received the "invaluable" evangelizing work of his master, and that the Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

principle of equality referred to equality in the hereafter and the superiority of the white man in the present. This did not prevent slaves from being transported in subhuman conditions; the journey from Africa to America lasted about two months and was carried out on disease-ridden ships, with poor or no ventilation, and in overcrowded conditions.

Ethnic origins

The first Portuguese conquerors to reach the African coasts had a fairly direct approach to enslaving the natives, relying on war expeditions in which they kidnapped the natives; however the process was cumbersome and difficult, so it was eventually replaced by trading posts, in which manufactured products were exchanged by local leaders in exchange for captured slaves. The bulk of African slaves arriving in the New World was taken from the West African coasts, understood as the space between the Senegal and Cuanza rivers. Determining the ethnic origin of slaves is complex, since the records of the time come from Europeans interested in identifying the port of origin and not in making any type of ethnographic assessment. Because of this, the various researchers who approach the question of the origins of Afro-Colombian slaves often have no choice but to group their origin into larger regions, often divided into three. Luz Adriana Maya identifies these as: Sudano-Sahelian, the tropical forest and the equatorial rainforest; John Thornton identifies the three regions as: Upper Guinea, Lower Guinea and the Angola region. These regions do not comprise single peoples, and include great diversity among them. The westernSahel

The Sahel (; ar, ساحل ' , "coast, shore") is a region in North Africa. It is defined as the ecoclimatic and biogeographic realm of transition between the Sahara to the north and the Sudanian savanna to the south. Having a hot semi-arid c ...

region is home to ethnic groups such as the Fulani, Mande Mande may refer to:

* Mandé peoples of western Africa

* Mande languages

* Manding, a term covering a subgroup of Mande peoples, and sometimes used for one of them, Mandinka

* Garo people of northeastern India and northern Bangladesh

* Mande River ...

and Songhai. The region was home to the largest empires in Sub-Saharan Africa, the Empire of Ghana, Empire of Mali

The Mali Empire ( Manding: ''Mandé''Ki-Zerbo, Joseph: ''UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol. IV, Abridged Edition: Africa from the Twelfth to the Sixteenth Century'', p. 57. University of California Press, 1997. or Manden; ar, مالي, Māl ...

and Songhai Empire

The Songhai Empire (also transliterated as Songhay) was a state that dominated the western Sahel/Sudan in the 15th and 16th century. At its peak, it was one of the largest states in African history. The state is known by its historiographical ...

. The latter two would become a direct part of the slave trade and collapse during it. The two later empires would be Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

, which would influence not only their dominant ethnic groups but other peoples who would arrive in chains at the ports of Cartagena de Indias

Cartagena ( , also ), known since the colonial era as Cartagena de Indias (), is a city and one of the major ports on the northern coast of Colombia in the Caribbean Coast Region, bordering the Caribbean sea. Cartagena's past role as a link ...

such as the Balanta Balanta may refer to:

Surname

* Ángelo Balanta, Colombian footballer

* Deivy Balanta, Colombian footballer

* Éder Álvarez Balanta, Colombian footballer

* Kevin Balanta, Colombian footballer

* Leyvin Balanta, Colombian footballer

Ethnic gro ...

, Bijagós, Diola, Nalu and Susu.

In the Gulf of Guinea region, peoples can be divided into two macro-groups, the Kwe peoples and the speakers of Volta-Niger languages. This region was dominated by smaller states like the Ashanti Kingdom

The Asante Empire (Asante Twi: ), today commonly called the Ashanti Empire, was an Akan state that lasted between 1701 to 1901, in what is now modern-day Ghana. It expanded from the Ashanti Region to include most of Ghana as well as parts of Iv ...

as well as the city states of Ife and Benin. It is the origin of peoples such as the Yoruba

The Yoruba people (, , ) are a West African ethnic group that mainly inhabit parts of Nigeria, Benin, and Togo. The areas of these countries primarily inhabited by Yoruba are often collectively referred to as Yorubaland. The Yoruba constitute ...

, Igbo and Ashanti people

The Asante, also known as Ashanti () are part of the Akan ethnic group and are native to the Ashanti Region of modern-day Ghana. Asantes are the last group to emerge out of the various Akan civilisations. Twi is spoken by over nine million Asante ...

. This region represents the origin of several Afro-Caribbean religions

Afro-Caribbean people or African Caribbean are Caribbean people who trace their full or partial ancestry to Sub-Saharan Africa. The majority of the modern African-Caribbeans descend from Africans taken as slaves to colonial Caribbean via the tr ...

still practiced in Colombia such as Santeria, which has its origin in the Yoruba religion.

In the southernmost region between the Congo river delta and present-day Angola, the great majority of the peoples were of Bantu

Bantu may refer to:

*Bantu languages, constitute the largest sub-branch of the Niger–Congo languages

*Bantu peoples, over 400 peoples of Africa speaking a Bantu language

* Bantu knots, a type of African hairstyle

*Black Association for National ...

origin, mainly Kikongo and Kimbundu

Kimbundu, a Bantu language which has sometimes been called Mbundu

or 'North Mbundu' (see Umbundu), is the second-most-widely-spoken Bantu language in Angola.

Its speakers are concentrated in the north-west of the country, notably in the Lua ...

speakers. The region included states such as the small Lunda Empire and the great Kingdom of Kongo

The Kingdom of Kongo ( kg, Kongo dya Ntotila or ''Wene wa Kongo;'' pt, Reino do Congo) was a kingdom located in central Africa in present-day northern Angola, the western portion of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the Republic of the ...

, whose king Afonso I unsuccessfully attempted to stop the slave trade from his domain by sending correspondence to John III of Portugal

John III ( pt, João III ; 7 June 1502 – 11 June 1557), nicknamed The Pious (Portuguese: ''o Piedoso''), was the King of Portugal and the Algarves from 1521 until his death in 1557. He was the son of King Manuel I and Maria of Aragon, the thi ...

speaking of the "corruption and depravity" of European slavers who depopulated their country. He also sent emissaries to deal with the Pope, but these were intersected by the Portuguese upon landing in Lisbon

Lisbon (; pt, Lisboa ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 544,851 within its administrative limits in an area of 100.05 km2. Grande Lisboa, Lisbon's urban area extends beyond the city's administr ...

.

On the Caribbean coast

Cartagena de Indias

Cartagena ( , also ), known since the colonial era as Cartagena de Indias (), is a city and one of the major ports on the northern coast of Colombia in the Caribbean Coast Region, bordering the Caribbean sea. Cartagena's past role as a link ...

was the main port of entry of slaves into the country during the colonial period and during its highest boom it turned out to be the most lucrative business in the city. By 1620 the city had 6,000 inhabitants, of whom 1,400 were slaves of African origin, by 1686 the number of slaves had increased to 2,000. In the census carried out between 1778 and 1780 it was determined that the slave population represented 10% of the population in the Santa Marta Province and 8% in the Cartagena Province

Cartagena Province ( es, Provincia de Cartagena), also called ''Gobierno de Cartagena'' (Government of Cartagena) during the Spanish imperial era, was an administrative and territorial division of New Granada in the Viceroyalty of Peru. It was or ...

.

The use of slave labor turned out to be essential for the economy of the Cartagena Province, both in urban and rural areas. With the death of the vast majority of the native population, the work of the Africans became highly relevant. Although during the seventeenth century slave labor was used in both agriculture and livestock, eventually it became concentrated around only the latter since agriculture is seasonal and therefore less profitable for the slave owner who wanted to minimize the hours in which the slave did not work.

Inside the cities, slavery gained a function not only of production but of status, all the houses of prosperous Spaniards in Cartagena and Mompós were endowed with black servitude, which served as a sign of opulence. These slaves were traded during the 17th century for a value between 200 and 400 silver pesos each.

The system of production with slave labor required a constant influx of new slaves, since the population of African origin had negative growth rates in the New World. This was due to various factors such as the number of men exceeding that of women by a factor of 5 to 1 because they were considered more productive, as well as the high death rate among workers. This required the constant influx of new "Bozales" slaves (born in Africa).

Slavery in the Cartagena province began to decline in the 18th century. During the republican era the institution entered into a true decline, mainly in rural areas where the current system of production ceased to be replaced by cheap mestizo labor. In urban areas slavery managed to maintain its relevance because it was more linked to the exhibition of status than to modes of production, so it continued to be a relevant system until its abolition in the 19th century.

On the Pacific coast

The first attempts at mining using slaves of African origin in the Pacific coast of New Granada occurred during the 17th century. However, these attempts were very limited and mostly unsuccessful due to the great difficulties that the Spanish had in subjugating the native populations. Large mining operations, and with them the massive trafficking of African slaves to the west coast, would not begin until the last two decades of the 17th century. The vast majority of the African slaves that would eventually reach the Pacific entered through the port ofCartagena de Indias

Cartagena ( , also ), known since the colonial era as Cartagena de Indias (), is a city and one of the major ports on the northern coast of Colombia in the Caribbean Coast Region, bordering the Caribbean sea. Cartagena's past role as a link ...

; in the Pacific they were marketed for a value of about 300 silver pesos if they were born in Africa, and between 400 and 500 if they were born in the New world. From analysis of documents of the time, it seems that more than half of the slaves who arrived in Chocó were of Kwa origin, mainly from the Akan and Ewe, there were also important minorities of Mandé, Gur speakers and Kru.

The Pacific coast was the colonial area with the highest percentage of slave population in New Granada New Granada may refer to various former national denominations for the present-day country of Colombia.

*New Kingdom of Granada, from 1538 to 1717

*Viceroyalty of New Granada, from 1717 to 1810, re-established from 1816 to 1819

*United Provinces of ...

territory. In the 1778–1780 census it was found that slaves in Chocó constituted 39% of the population, 38% in Iscuandé, 63% in Tumaco

Tumaco is a port city and municipality in the Nariño Department, Colombia, by the Pacific Ocean. It is located on the southwestern corner of Colombia, near the border with Ecuador, and experiences a hot tropical climate. Tumaco is inhabited mai ...

, and in Raposo (Modern day Buenaventura), an extraordinary 70%.

These slaves destined for mining production were a vital component in the Pacific Region. Between 1680 and 1700 Popayán was the source of 41% of the gold production in New Granada New Granada may refer to various former national denominations for the present-day country of Colombia.

*New Kingdom of Granada, from 1538 to 1717

*Viceroyalty of New Granada, from 1717 to 1810, re-established from 1816 to 1819

*United Provinces of ...

.

Rebellions

Indigenous rebellions

The first to oppose the imposition of forced labor by Europeans were indigenous peoples. During the 16th century there were rebellions of the Paeces, Muzos, and Yariguis. The Chinantos rebelled against the town of San Cristóbal, while the Tupes did the same inSanta Marta

Santa Marta (), officially Distrito Turístico, Cultural e Histórico de Santa Marta ("Touristic, Cultural and Historic District of Santa Marta"), is a city on the coast of the Caribbean Sea in northern Colombia. It is the capital of Magdalena ...

. However, the Pijaos

The Pijao (also Piajao, Pixao, Pinao) are an indigenous people from Colombia.

Ethnography

The Pijao or Pijaos formed a loose federation of Amerindians and were living in the present-day department of Tolima Department, Tolima, Colombia. In ...

were the most successful in this regard, managing to stop work in the mines of Cartago and Buga

Buga may refer to:

Places

* Mount Buga, an inactive volcano in Zamboanga del Sur province, the Philippines

* Buga (barangay), a barangay in San Miguel Municipality, Bulacan, Philippines

* Buga, Valle del Cauca, city and municipality in the Colom ...

, successfully interrupting communication with Popayán and Peru, and killing the Governor of Popayán Vasco de Quiroga. The war waged during the first decade of the 17th century would end with a victory for the Europeans, who would be rewarded for their service in the form of encomienda

The ''encomienda'' () was a Spanish labour system that rewarded conquerors with the labour of conquered non-Christian peoples. The labourers, in theory, were provided with benefits by the conquerors for whom they laboured, including military ...

s.

African rebellions

African slaves frequently rebelled against their masters, either through the practice of cimarronaje or through armed rebellion. InSanta Marta

Santa Marta (), officially Distrito Turístico, Cultural e Histórico de Santa Marta ("Touristic, Cultural and Historic District of Santa Marta"), is a city on the coast of the Caribbean Sea in northern Colombia. It is the capital of Magdalena ...

in 1530, just five years after the city was built, a slave rebellion destroyed the town. The city would be rebuilt only to suffer a new rebellion in the 1550s.

Although it was certainly possible for an individual slave to flee their masters and go unnoticed among the free black population of a large city, it was a precarious situation in which the fugitive was at constant risk of discovery; therefore it is natural that many acts of flight were organized and directed towards communities of Maroons in which they could find security with those of their own class.

Not all rebellion activities ended in flight, in several cases the threat of revolt was used as a method within collective bargaining. In 1768 in the province of Santa Marta a group of slaves wounded a foreman whom they accused of ill-treatment, when their master sent a couple of white men to subdue them, the slaves killed one of them. Far from being intimidated, the rebels gave their master an ultimatum, if he did not agree to their demands they would burn down the entire estate and escape to live with the "brave Indians." Without further remedy, the master accepted their demands, swearing to forgive them for the revolt, stopping the mistreatment and agreeing that if the slaves were ever sold this should be done collectively so as not to divide the families. The owner also agreed to provide the workers with a good quantity of tobacco and brandy as compensation for the abuses. Similar incidents occurred in Neiva in 1773 and Cúcuta

Cúcuta (), officially San José de Cúcuta, is a Colombian municipality, capital of the department of Norte de Santander and nucleus of the Metropolitan Area of Cúcuta. The city is located in the homonymous valley, at the foot of the Eastern ...

in 1780, in which the slaves had reached a sort of agreement with the Jesuit priests

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders = ...

in which their treatment was more similar to that of free peasants in a sharecropping, being granted with remuneration for their crops and with holidays. When a new master refused to uphold what the slaves considered their customary rights, they did not hesitate to go into open rebellion and demand that the colonial government authorities recognize their rights.

On the other hand, it is important to recognize that the resistance strategies of the black women enslaved during the colonial period were aimed at confronting colonial power by resorting to judicial demands.

However, the most famous slave rebellion in New Granada New Granada may refer to various former national denominations for the present-day country of Colombia.

*New Kingdom of Granada, from 1538 to 1717

*Viceroyalty of New Granada, from 1717 to 1810, re-established from 1816 to 1819

*United Provinces of ...

was undoubtedly that of the slaves of San Basilio de Palenque, led by Benkos Biohó. The rebellion was so successful that on August 23, 1691 the king of Spain was forced to issue a certificate ordering the general freedom of the Palenques and their right to land.

At the end of the 17th century, the colonial authorities tried again to start a great campaign against the Maroon Palenques, but despite succeeding in destroying some villages, the entire campaign turned out to be a failure, since the targeted black communities managed to preserve their freedom and simply moved south.

Cimarronaje would continue until the 19th century with the abolition of slavery, after which the former slaves would exercise new forms of resistance seeking to retaliate against their former masters: they would roam the fields, tearing down fences, raiding property, and punishing conservatives with their whips. This period was named by the President José Hilario López

José Hilario López Valdés (18 February 1798, Popayán, Cauca – 27 November 1869, Campoalegre, Huila) was a Colombian politician and military officer. He was the President of Colombia between 1849 and 1853.Arismendi Posada, Ignacio; ...

as "The democratic frolics."

Abolition

Abolition was a gradual process. Manumission of enslaved individuals occurred throughout the history of the colony, but the abolition of slavery as an institution was not seriously considered until the Napoleonic invasion of Spain, when, beginning in 1809, the question of freedom was raised in the Iberian courts to prevent "slaves from seeking and even achieving it by violent and coercive means".

Abolition was a gradual process. Manumission of enslaved individuals occurred throughout the history of the colony, but the abolition of slavery as an institution was not seriously considered until the Napoleonic invasion of Spain, when, beginning in 1809, the question of freedom was raised in the Iberian courts to prevent "slaves from seeking and even achieving it by violent and coercive means". Antonio Villavicencio

Antonio Villavicencio y Verástegui (January 9, 1775 – June 6, 1816) was a statesman and soldier of New Granada, born in Quito, and educated in Spain. He served in the Battle of Trafalgar as an officer in the Spanish Navy with the rank of Sec ...

was a proponent of freedom of wombs

Freedom of wombs ( es, Libertad de vientres, pt, Lei do Ventre Livre), also referred to as free birth or the law of wombs, was a 19th century judicial concept in several Latin American countries, that declared that all wombs bore free children. A ...

, but his views were not heeded by the Spanish crown.

During the war of independence of Colombia, Simón Bolívar

Simón José Antonio de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar y Palacios (24 July 1783 – 17 December 1830) was a Venezuelan military and political leader who led what are currently the countries of Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Panama and B ...

introduced in 1816 the idea of granting freedom to slaves who participated in the independence cause. This process was controversial, because the landowners who depended on slaves both for work and social status staunchly opposed the liberation process.

In order to compromise with the demands of the slavers who demanded that their property be respected, José Félix de Restrepo managed to decree in the Congress of Cúcuta the "freedom of wombs", which declared that children born of slaves as of July 21, 1821, would be free. The law also established for the masters the obligation to "Educate, clothe and feed the children ..but they as a reward will have to compensate the masters of their mothers for the expenses incurred in their upbringing, with their works and services, which they will provide until the age of 18.” The slave trade was definitively prohibited in 1825.

Although the freedom of young slaves should have started on July 21, 1839, the process was largely delayed by the War of the Supremes, which was fought from 1839 to 1842. After the war and under pressure of the masters, a new law of May 29, 1842, extended the dependence on slaves for another 7 years through what was called apprenticeship. In other words, the 18-year-old slaves would be presented to the mayors who should have them serve their former master or someone else who could "educate and instruct" them in a trade or profession. In this way slavery was extended, while those who refused to participate were recruited into the national army.

The inefficiency of the manumission, as well as the corruption of officials and landowners who continued with the slave trade ignoring the law caused great discontent among the so-called Democratic Societies (liberal associations of artisans). This great political upheaval, coming from both the artisans and the slaves themselves, led President José Hilario López

José Hilario López Valdés (18 February 1798, Popayán, Cauca – 27 November 1869, Campoalegre, Huila) was a Colombian politician and military officer. He was the President of Colombia between 1849 and 1853.Arismendi Posada, Ignacio; ...

to propose absolute freedom. Finally, the Colombian Congress

The Congress of the Republic of Colombia ( es, Congreso de la República de Colombia) is the name given to Colombia's bicameral national legislature.

The Congress of Colombia consists of the 108-seat Senate, and the 188-seat Chamber of Re ...

passed a law in May 21, 1851, by means of which the slaves would be free as of January 1, 1852, and the masters would be compensated with bonds.

Even so, in many places the masters refused to let the slaves go in a peaceful way. This led to the Civil War of 1851, which began with an insurrection in Cauca and Pasto headed by the Conservative leaders Manuel Ibáñez and Julio Arboleda

Julio Arboleda Pombo (9 June 1817, Barbacoas, Colombia – 1862) was a Colombian poet, journalist, and politician. He was also a prominent slave owner, and led a failed rebellion in 1851 with the aim of preventing the abolition of slavery i ...

with the support of the Ecuadorian government. In Antioquia Antioquia is the Spanish form of Antioch.

Antioquia may also refer to:

* Antioquia Department, Colombia

* Antioquia State, Colombia (defunct)

* Antioquia District, Peru

* Antioquia Railway

The Antioquia Railway ( es, Ferrocarril de Antioquia) i ...

the rebellion broke out at the hands of conservatives led by Eusebio Berrero. The war would end in four months with the liberal victory and the final liberation of the slaves.

The number of enslaved people declined throughout the republican period until the definitive abolition of the institution:

See also

* Afro-Colombians * Slavery in Brazil * Slavery in Canada * Slavery in Colonial America *Slavery in Latin America

Slavery in Latin America was an economic and social institution that existed in Latin America from before the colonial era until its legal abolition in the newly independent states during the 19th century. However, it continued illegally in some ...

* Slavery in New Spain

Slavery in New Spain was based mainly on the importation of slaves from West and Central Africa to work in the colony in the enormous plantations, ranches or mining areas of the viceroyalty, since their physical consistency made them suitable for ...

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * {{Americas topic, Slavery in Colonial Colombia Racism in Colombia Social history of Colombia