Slamat disaster on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''Slamat'' disaster is a succession of three related shipwrecks during the

''Slamat'' was in the Mediterranean by 23 April, and on the 24th she was one of six merchant ships that left

''Slamat'' was in the Mediterranean by 23 April, and on the 24th she was one of six merchant ships that left  At 2340 hrs on 26 April the light cruisers and joined ''Khedive Ismail'', ''Slamat'', ''Calcutta'' and four destroyers in the Bay of Nauplia. The destroyer patrolled against the risk of submarines while the other ships took turns to embark troops. The only available tenders were landing craft ''A5'', local

At 2340 hrs on 26 April the light cruisers and joined ''Khedive Ismail'', ''Slamat'', ''Calcutta'' and four destroyers in the Bay of Nauplia. The destroyer patrolled against the risk of submarines while the other ships took turns to embark troops. The only available tenders were landing craft ''A5'', local

''Orion'', ''Isis'' and ''Khedive Ismail'' kept moving to reach

''Orion'', ''Isis'' and ''Khedive Ismail'' kept moving to reach

Pridham-Wippell sent the destroyer to the position in the Argolic Gulf where ''Slamat'' had been lost. ''Griffin'' found 14 survivors in two Carley floats. At 0240 hrs she reported the rescue, said both destroyers had been sunk about 1330 hrs and she was still looking for ''Wryneck''s whaler. In the morning she found more floats and another four survivors. She took the survivors to Crete.

The last living survivor from ''Slamat'',

Pridham-Wippell sent the destroyer to the position in the Argolic Gulf where ''Slamat'' had been lost. ''Griffin'' found 14 survivors in two Carley floats. At 0240 hrs she reported the rescue, said both destroyers had been sunk about 1330 hrs and she was still looking for ''Wryneck''s whaler. In the morning she found more floats and another four survivors. She took the survivors to Crete.

The last living survivor from ''Slamat'',

Vice Admiral Pridham-Wippell held ''Slamat'' chiefly responsible of the disaster, asserting that her failure to depart until 75 minutes after she was ordered "resulted in her being within range of the dive bombers well after dawn." In a volume of his history ''

Vice Admiral Pridham-Wippell held ''Slamat'' chiefly responsible of the disaster, asserting that her failure to depart until 75 minutes after she was ordered "resulted in her being within range of the dive bombers well after dawn." In a volume of his history ''

Battle of Greece

The German invasion of Greece, also known as the Battle of Greece or Operation Marita ( de , Unternehmen Marita, links = no), was the attack of Greece by Italy and Germany during World War II. The Italian invasion in October 1940, which is usu ...

on 27 April 1941. The Dutch troopship

A troopship (also troop ship or troop transport or trooper) is a ship used to carry soldiers, either in peacetime or wartime. Troopships were often drafted from commercial shipping fleets, and were unable land troops directly on shore, typicall ...

and the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

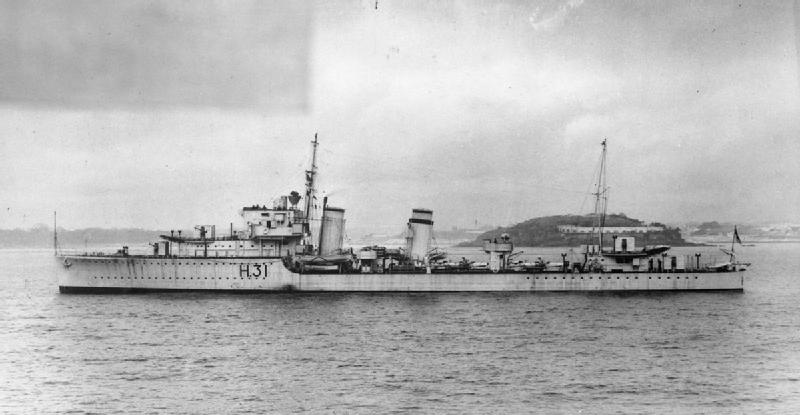

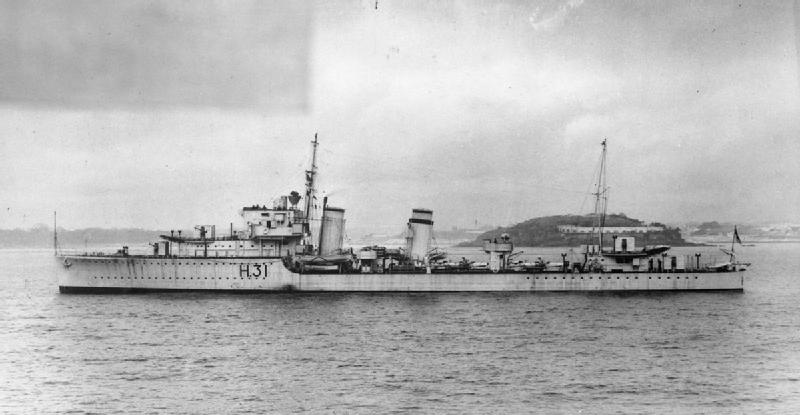

destroyers and sank as a result of air attacks by ''Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

'' Junkers Ju 87

The Junkers Ju 87 or Stuka (from ''Sturzkampfflugzeug'', "dive bomber") was a German dive bomber and ground-attack aircraft. Designed by Hermann Pohlmann, it first flew in 1935. The Ju 87 made its combat debut in 1937 with the Luftwaffe's Con ...

dive bomber

A dive bomber is a bomber aircraft that dives directly at its targets in order to provide greater accuracy for the bomb it drops. Diving towards the target simplifies the bomb's trajectory and allows the pilot to keep visual contact througho ...

s. The three ships sank off the east coast of the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic regions of Greece, geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmu ...

during Operation Demon, which was the evacuation of British, Australian and New Zealand troops from Greece after their defeat by invading German and Italian forces.

The loss of the three ships caused an estimated 983 deaths. Only 66 men survived.

Operation Demon

On 6 April 1941 Germany and Italy invaded Yugoslavia andGreece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

. An expeditionary force of British, Australian and New Zealand troops was already in Greece, but they and Greek defenders lost ground to the invaders and by 17 April the British Empire was starting to plan the evacuation of 60,000 troops.

''Slamat'' was a Dutch troop ship, converted from a Koninklijke Rotterdamsche Lloyd

The Royal Rotterdam Lloyd (Koninklijke Rotterdamsche Lloyd or KRL) was a Dutch shipping company that was established in Rotterdam between 1883 and 1970. Until 1947 the name was Rotterdamsche Lloyd (RL). In 1970 the KRL merged with sev ...

("Royal Dutch Lloyd") ocean liner

An ocean liner is a passenger ship primarily used as a form of transportation across seas or oceans. Ocean liners may also carry cargo or mail, and may sometimes be used for other purposes (such as for pleasure cruises or as hospital ships).

Ca ...

. Since October 1940 she had been operating in the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by th ...

, but in April 1941 she was ordered through the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popular ...

to the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ea ...

to join Operation Demon.

Convoy AG 14

''Slamat'' was in the Mediterranean by 23 April, and on the 24th she was one of six merchant ships that left

''Slamat'' was in the Mediterranean by 23 April, and on the 24th she was one of six merchant ships that left Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

with Convoy AG 14 for Greece. British, Australian and New Zealand forces were spread over much of Greece, so on 26 April when AG 14 reached Greek waters, it split to reach different embarkation points. ''Slamat'' and a smaller troop ship, the managed by British-India Line, were ordered with the cruiser and a number of destroyers to Nauplia

Nafplio ( ell, Ναύπλιο) is a coastal city located in the Peloponnese in Greece and it is the capital of the regional unit of Argolis and an important touristic destination. Founded in antiquity, the city became an important seaport in the ...

and Tolon on the Argolic Gulf The Argolic Gulf (), also known as the Gulf of Argolis, is a gulf of the Aegean Sea off the east coast of the Peloponnese, Greece. It is about 50 km long and 30 km wide. Its main port is Nafplio, at its northwestern end. At the entrance to ...

in the eastern Peloponnese

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic regions of Greece, geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmu ...

. The corvette swept Nauplia Bay for mines before the ships arrived.

''Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

'' air reconnaissance found AG 14 at noon on 26 April. The invaders had air superiority, and Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

capacity to resist was being reduced daily. On 24 April the Belfast Steamship Company

The Belfast Steamship Company provided shipping services between Belfast in Ireland (later Northern Ireland) and Liverpool in England from 1852 to 1975.''Sea breezes: the ship lovers' digest'', Volume 42. Pacific Steam Navigation Company. 1968. ...

troop ship had grounded in the fairway in Nauplia Bay, blocking ship access to the port. The next day an air attack turned the grounded ship into a total loss. Ships would now have to anchor in the bay and tenders would be needed to bring troops and equipment out to them from the shore, so the landing ship, infantry (a converted Glen Line

Glen Line was a UK shipping line that was founded in Glasgow in 1867. Its head office was later moved first to London and then to Liverpool.

History

The firm had its roots in the co-operation between the Gow and McGregor families in Glasgow ...

merchant ship) was sent to deliver several Landing Craft Assault

Landing Craft Assault (LCA) was a landing craft used extensively in World War II. Its primary purpose was to ferry troops from transport ships to attack enemy-held shores. The craft derived from a prototype designed by John I. Thornycroft Ltd. ...

to Nauplia. However, on 26 April a Junkers Ju 87

The Junkers Ju 87 or Stuka (from ''Sturzkampfflugzeug'', "dive bomber") was a German dive bomber and ground-attack aircraft. Designed by Hermann Pohlmann, it first flew in 1935. The Ju 87 made its combat debut in 1937 with the Luftwaffe's Con ...

''Stuka'' attack disabled ''Glenearn'', so she put her LCAs ashore for use at Monemvasia

Monemvasia ( el, Μονεμβασιά, Μονεμβασία, or ) is a town and municipality in Laconia, Greece. The town is located on a small island off the east coast of the Peloponnese, surrounded by the Myrtoan Sea. The island is connected t ...

and was towed to Souda Bay

Souda Bay is a bay and natural harbour near the town of Souda on the northwest coast of the Greece, Greek island of Crete. The bay is about 15 km long and only two to four km wide, and a deep natural harbour. It is formed between the Akr ...

. ''En route'' to Nauplia the convoy was attacked by aircraft and a number of bombs hit ''Slamat'', causing heavy damage on B and C decks, destroying two of her lifeboats and wounding one crewman. The Germans recognised that the ships would embark troops overnight and leave early the next morning (27 April), so ''General der Flieger

''General der Flieger'' ( en, General of the aviators) was a General of the branch rank of the Luftwaffe (air force) in Nazi Germany. Until the end of World War II in 1945, this particular general officer rank was on three-star level ( OF-8), e ...

'' Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen

Wolfram Karl Ludwig Moritz Hermann Freiherr von Richthofen (10 October 1895 – 12 July 1945) was a German World War I flying ace who rose to the rank of ''Generalfeldmarschall'' in the Luftwaffe during World War II.

Born in 1895 into a fa ...

, commander of the '' VIII. Fliegerkorps'', planned to attack the ships as they left their various embarkation points.

At 2340 hrs on 26 April the light cruisers and joined ''Khedive Ismail'', ''Slamat'', ''Calcutta'' and four destroyers in the Bay of Nauplia. The destroyer patrolled against the risk of submarines while the other ships took turns to embark troops. The only available tenders were landing craft ''A5'', local

At 2340 hrs on 26 April the light cruisers and joined ''Khedive Ismail'', ''Slamat'', ''Calcutta'' and four destroyers in the Bay of Nauplia. The destroyer patrolled against the risk of submarines while the other ships took turns to embark troops. The only available tenders were landing craft ''A5'', local caïque

A caïque ( el, καΐκι, ''kaiki'', from tr, kayık) is a traditional fishing boat usually found among the waters of the Ionian or Aegean Sea, and also a light skiff used on the Bosporus. It is traditionally a small wooden trading vessel, br ...

s and the ships' own boats. One caïque, ''Agios Giorgios'', was a large boat with capacity for 600 men. There was a swell and a light wind, and in the dark there were one or two accidents and one ship's whaler

A whaler or whaling ship is a specialized vessel, designed or adapted for whaling: the catching or processing of whales.

Terminology

The term ''whaler'' is mostly historic. A handful of nations continue with industrial whaling, and one, Japa ...

capsized. ''Calcutta'' and ''Orion'' embarked 960 and 600 troops respectively; the destroyers and 500 and 408. The slow rate of embarkation meant that ''Khedive Ismail'' did not get her turn and did not embark any troops.

At 0300 hrs ''Calcutta'' ordered all ships to sail, but ''Slamat'' disobeyed and continued embarking troops. ''Calcutta'' and ''Khedive Ismail'' sailed at 0400 hrs; ''Slamat'' followed at 0415 hrs, by which time she had embarked about 500 troops: about half her capacity. An estimated 700–2,000 men were left behind, but ''Hotspur'' remained at Nauplia to embark as many of them as possible.

Loss of ''Slamat''

The convoy steamed south down the Argolic Gulf; ''Calcutta'' and ''Khedive Ismail'' at and ''Slamat'' full ahead at to catch up. At 0645 or 0715 hrs ''Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

'' aircraft attacked the convoy off Leonidio

Leonidio ( el, Λεωνίδιο, Katharevousa: Λεωνίδιον, Tsakonian: Αγιελήδι) is a town and a former municipality in Arcadia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality South Kyn ...

n near the mouth of the gulf. Three Messerschmitt Bf 109

The Messerschmitt Bf 109 is a German World War II fighter aircraft that was, along with the Focke-Wulf Fw 190, the backbone of the Luftwaffe's fighter force. The Bf 109 first saw operational service in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War an ...

fighters attacked first, followed by a '' Staffel'' of nine Junkers Ju 87

The Junkers Ju 87 or Stuka (from ''Sturzkampfflugzeug'', "dive bomber") was a German dive bomber and ground-attack aircraft. Designed by Hermann Pohlmann, it first flew in 1935. The Ju 87 made its combat debut in 1937 with the Luftwaffe's Con ...

''Stuka'' dive bomber

A dive bomber is a bomber aircraft that dives directly at its targets in order to provide greater accuracy for the bomb it drops. Diving towards the target simplifies the bomb's trajectory and allows the pilot to keep visual contact througho ...

s from ''Sturzkampfgeschwader 77

''Sturzkampfgeschwader'' 77 (StG 77) was a Luftwaffe dive bomber wing during World War II. From the outbreak of war StG 77 distinguished itself in every Wehrmacht major operation until the Battle of Stalingrad in 1942. If the claims mad ...

'' at Almyros, Junkers Ju 88

The Junkers Ju 88 is a German World War II ''Luftwaffe'' twin-engined multirole combat aircraft. Junkers Aircraft and Motor Works (JFM) designed the plane in the mid-1930s as a so-called ''Schnellbomber'' ("fast bomber") that would be too fast ...

and Dornier Do 17

The Dornier Do 17 is a twin-engined light bomber produced by Dornier Flugzeugwerke for the German Luftwaffe during World War II. Designed in the early 1930s as a ''Schnellbomber'' ("fast bomber") intended to be fast enough to outrun opposing a ...

bombers and more Bf 109s. The attackers mainly targeted the troop ships, but anti-aircraft fire from ''Calcutta'' and ''Diamond'' at first prevented aircraft from hitting ''Slamat''. Then a SC250 bomb exploded between her bridge

A bridge is a structure built to span a physical obstacle (such as a body of water, valley, road, or rail) without blocking the way underneath. It is constructed for the purpose of providing passage over the obstacle, which is usually somethi ...

and forward funnel, setting the bridge, control room and Master's cabin afire. Her water system became disabled, hampering her crew's ability to fight the fire. Another bomb also hit the ship and she listed to starboard.

''Slamat''s Master

Master or masters may refer to:

Ranks or titles

* Ascended master, a term used in the Theosophical religious tradition to refer to spiritually enlightened beings who in past incarnations were ordinary humans

*Grandmaster (chess), National Master ...

, Tjalling Luidinga, gave the order to abandon ship. The bombing and fire had destroyed some of her lifeboats and life rafts, and her remaining boats and rafts were launched under a second ''Stuka'' attack. ''Hotspur'' reported seeing four bombs hit ''Slamat''. At least two lifeboats capsized; No. 10 from overloading and No. 4 when, in the midst of transferring survivors, ''Diamond'' had to speed away from her to evade an air attack. One ''Stuka'' pilot, Bertold Jung, saw "one or two" fellow-pilots machine-gunning survivors in the boats. Jung had served in the

German navy, and back at Almyros airfield he complained very strongly that people in lifeboats had suffered enough so in future they should be spared.

''Orion'', ''Isis'' and ''Khedive Ismail'' kept moving to reach

''Orion'', ''Isis'' and ''Khedive Ismail'' kept moving to reach Souda Bay

Souda Bay is a bay and natural harbour near the town of Souda on the northwest coast of the Greece, Greek island of Crete. The bay is about 15 km long and only two to four km wide, and a deep natural harbour. It is formed between the Akr ...

, while ''Calcutta'' rescued some survivors and ordered the destroyer ''Diamond'' to go alongside ''Slamat'' to rescue more. At 0815 hrs ''Diamond'' reported that she was still rescuing survivors and still under air attack. At 0916 hrs the destroyers , and arrived from Souda Bay

Souda Bay is a bay and natural harbour near the town of Souda on the northwest coast of the Greece, Greek island of Crete. The bay is about 15 km long and only two to four km wide, and a deep natural harbour. It is formed between the Akr ...

in Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, and ...

to reinforce the convoy, so ''Calcutta'' sent ''Wryneck'' to assist ''Diamond''. At 0925 hrs ''Diamond'' reported that she had rescued most of the survivors and was proceeding to Souda Bay. She left several people behind on life rafts, where aircraft machine-gunned them. ''Calcutta''s captain said the attack continued until about 1000 hrs. ''Wryneck'' reached ''Diamond'' about 1000 hrs and signalled a request for aircraft cover at 1025 hrs.

''Diamond'' accompanied by ''Wryneck'' returned to ''Slamat'', arriving about 1100 hrs. The destroyers found ''Slamat''s No. 10 and No. 4 lifeboats, both of which had been righted. They rescued 30 troops and two Dutch crew from No. 10 and ''Slamat''s Second Officer and several other survivors from No. 4. ''Slamat'' was afire from stem to stern, and ''Diamond'' fired a torpedo at her port side that sank her in a ''coup de grâce

A coup de grâce (; 'blow of mercy') is a death blow to end the suffering of a severely wounded person or animal. It may be a mercy killing of mortally wounded civilians or soldiers, friends or enemies, with or without the sufferer's consent.

...

''. By now ''Diamond'' carried about 600 of ''Slamat''s survivors, including Captain Luidinga.

Loss of ''Diamond'' and ''Wryneck''

About 1315 hrs a ''Staffel'' of between four and nine Ju 87 bombers came out of the sun in a surprise attack on the two destroyers. One bomb hit ''Diamond''sengine room

On a ship, the engine room (ER) is the compartment where the machinery for marine propulsion is located. To increase a vessel's safety and chances of surviving damage, the machinery necessary for the ship's operation may be segregated into vari ...

, stopping her engines and bringing down her funnel, mast and radio aerial. Another exploded in the sea off her port side, holing her hull below her foredeck. Her engine room petty officer

A petty officer (PO) is a non-commissioned officer in many navies and is given the NATO rank denotation OR-5 or OR-6. In many nations, they are typically equal to a sergeant in comparison to other military branches. Often they may be superior ...

, H.T. Davis, had been on deck, but rushed below and released the pressure from her No. 3 boiler to prevent the risk of a boiler explosion. She sank in eight minutes. Both of her lifeboats were destroyed, but her crew launched her three Carley float

The Carley float (sometimes Carley raft) was a form of invertible liferaft designed by American inventor Horace Carley (1838–1918). Supplied mainly to warships, it saw widespread use in a number of navies during peacetime and both World Wars ...

s.

Three bombs hit ''Wryneck''. The first exploded on her port side and damaged her hull; the second and third hit her engine room and bridge. Her Commissioned Engineer, Maurice Waldron, shut down her boilers and brought on deck a wounded Australian officer whom he had been looking after and put him in a Carley float. ''Wryneck'' capsized to port

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as Ham ...

but managed to launch her whaler

A whaler or whaling ship is a specialized vessel, designed or adapted for whaling: the catching or processing of whales.

Terminology

The term ''whaler'' is mostly historic. A handful of nations continue with industrial whaling, and one, Japa ...

and three Carley floats before she sank in 10–15 minutes.

Lt Cdr

Lieutenant commander (also hyphenated lieutenant-commander and abbreviated Lt Cdr, LtCdr. or LCDR) is a Officer (armed forces), commissioned officer military rank, rank in many navy, navies. The rank is superior (hierarchy), superior to a l ...

Philip Cartwright, who commanded ''Diamond'', was on a Carley float but gave his place to a sailor who was in the water. Cartwright was not seen again. Several men in the Carley floats died either from wounds or from drowning in the swell. They included Lt Cdr Robert Lane who commanded ''Wryneck'', and Dr G.H. Brand who was the civilian ship's doctor

A naval surgeon, or less commonly ship's doctor, is the person responsible for the health of the ship's company aboard a warship. The term appears often in reference to Royal Navy's medical personnel during the Age of Sail.

Ancient uses

Speciali ...

on ''Slamat''.

Rescues

''Wryneck''s whaler suffered two holes but was repaired. Her occupants were wet through, her compass was damaged and her drinking water contaminated. Her four oars were serviceable, so Commissioned Engineer Waldron took command and she set off east pastCape Maleas

Cape Maleas (also ''Cape Malea''; el, Ακρωτήριον Μαλέας, colloquially Καβομαλιάς, ''Cavomaliás''), anciently Malea ( grc, Μαλέα) and Maleae or Maleai (Μαλέαι), is a peninsula and cape in the southeast of the ...

, towing two Carley floats and their occupants. In the evening the wind increased, causing the floats to strike the boat, so Waldron reluctantly cast them adrift. Waldron was also nursing a Leading Seaman, George Fuller, who had bullet wounds in his belly and thigh.

At 1900 the cruiser and seven destroyers reached Souda Bay and disembarked evacuated troops. The Vice Admiral, Light Forces, Henry Pridham-Wippell

Admiral Sir Henry Daniel Pridham-Wippell, (12 August 1885 – 2 April 1952) was a Royal Navy officer who served in the First and Second World Wars.

Early life

Educated at The Limes, Greenwich, and at Royal Naval College, Dartmouth, Henry Daniel ...

, became concerned that ''Diamond'' was not among them. Between 1922 and 1955 hrs repeated attempts to radio ''Diamond'' drew no reply. ''Wryneck'' had been ordered to keep radio silence

In telecommunications, radio silence or Emissions Control (EMCON) is a status in which all fixed or mobile radio stations in an area are asked to stop transmitting for safety or security reasons.

The term "radio station" may include anything cap ...

so no attempt was made to radio her. Instead ''Phoebe'' and ''Calcutta'' were asked if they had seen her, but their replies at 2235 and 2245 hrs were indefinite.

Pridham-Wippell sent the destroyer to the position in the Argolic Gulf where ''Slamat'' had been lost. ''Griffin'' found 14 survivors in two Carley floats. At 0240 hrs she reported the rescue, said both destroyers had been sunk about 1330 hrs and she was still looking for ''Wryneck''s whaler. In the morning she found more floats and another four survivors. She took the survivors to Crete.

The last living survivor from ''Slamat'',

Pridham-Wippell sent the destroyer to the position in the Argolic Gulf where ''Slamat'' had been lost. ''Griffin'' found 14 survivors in two Carley floats. At 0240 hrs she reported the rescue, said both destroyers had been sunk about 1330 hrs and she was still looking for ''Wryneck''s whaler. In the morning she found more floats and another four survivors. She took the survivors to Crete.

The last living survivor from ''Slamat'', Royal Army Service Corps

The Royal Army Service Corps (RASC) was a corps of the British Army responsible for land, coastal and lake transport, air despatch, barracks administration, the Army Fire Service, staffing headquarters' units, supply of food, water, fuel and dom ...

veteran George Dexter, states that after ''Wryneck'' was sunk he and three other men were rescued by ''Orion''.

On the morning of 28 April the whaler was about off Milos

Milos or Melos (; el, label=Modern Greek, Μήλος, Mílos, ; grc, Μῆλος, Mêlos) is a volcanic Greek island in the Aegean Sea, just north of the Sea of Crete. Milos is the southwesternmost island in the Cyclades group.

The ''Venus d ...

in the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi (Greek language, Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish language, Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It ...

, so she set course for the island. At noon she sighted Ananes Rock, about southeast of Milos, so Waldron decided to land there as everyone was exhausted. The rock has a bay, where the whaler found a caïque full of Greek refugees and British soldiers who had set out from Piraeus

Piraeus ( ; el, Πειραιάς ; grc, Πειραιεύς ) is a port city within the Athens urban area ("Greater Athens"), in the Attica region of Greece. It is located southwest of Athens' city centre, along the east coast of the Saronic ...

, were headed for Crete, but were sailing only by night to avoid detection. In the evening the caïque left Ananes and headed south for Crete. As many as possible of the survivors transferred to the caïque, but she was very full so she towed the whaler with five men still in it. On the morning of 29 April the caïque sighted a small landing craft, ''A6'', which had set out from Porto Rafti near Athens. She took aboard everyone from the caïque and whaler, and the next day they reached Souda Bay. After a short stay the survivors from ''Slamat'', ''Diamond'' and ''Wryneck'' were taken on HMS ''Hotspur'' to Port Said

Port Said ( ar, بورسعيد, Būrsaʿīd, ; grc, Πηλούσιον, Pēlousion) is a city that lies in northeast Egypt extending about along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, north of the Suez Canal. With an approximate population of 6 ...

, Egypt.

Casualties

Nearly 1,000 people were killed in the loss of ''Slamat'', ''Diamond'' and ''Wryneck''. Of the 500 or so soldiers that ''Slamat'' embarked, eight survived. Of her complement of 193 crew and 21 Australian and New Zealand DEMS gunners, 11 survived. Of ''Diamond''s 166 complement, 20 survived. Of ''Wryneck''s 106 crew, 27 survived. ''Slamat'' had a mixed crew of 84Goans

Goans ( kok, गोंयकार, Romi Konkani: , pt, Goeses) is the demonym used to describe the people native to Goa, India, who form an ethno-linguistic group resulting from the assimilation of Indo-Aryan, Dravidian, Indo-Portuguese, and ...

, 74 Dutch, 24 Chinese, 10 Australians and a Norwegian. The 11 survivors were six Goans, four Dutch and one other.

The bodies of three of ''Slamat''s crew washed ashore far from the wreck: apprentice helmsman J Pille on the Greek island of Stamperia, Second Officer G van der Woude at Alexandria in Egypt, and lamp trimmer J van der Brugge at Gaza in Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

.

Controversy

Vice Admiral Pridham-Wippell held ''Slamat'' chiefly responsible of the disaster, asserting that her failure to depart until 75 minutes after she was ordered "resulted in her being within range of the dive bombers well after dawn." In a volume of his history ''

Vice Admiral Pridham-Wippell held ''Slamat'' chiefly responsible of the disaster, asserting that her failure to depart until 75 minutes after she was ordered "resulted in her being within range of the dive bombers well after dawn." In a volume of his history ''The Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

'', Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

wrote "At Navplion there was a disaster. The Slamat, in a gallant but misguided effort to embark the maximum number of men, stayed too long in the anchorage". The Dutch historian Karel Bezemer agreed that had ''Slamat'' obeyed orders and left on time, the convoy would not have been attacked.

Frans Luidinga, who in 1995 published a book about his father Tjalling Luidinga, points out that had ''Slamat'' left on time, the convoy would have been only further south at the time of the attack. This was still in range from Jg 77's base at Almyros and unlikely to have given enough advantage to the RAF's diminished fighter cover. The Germans knew the convoy would spend the night of 26–27 April evacuating troops from Nauplia and would not be far beyond the Argolic Gulf by daybreak. Frans Luidinga blames the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

for including troop ships in the evacuation, asserting that only warships had the speed, manoeuvrability and firepower to return from Nauplia under fire.

Against Luidinga's argument, the troop ship ''Khedive Ismail'' survived whereas the destroyers ''Diamond'' and ''Wryneck'' were sunk. And had the convoy been 20 nautical miles further south, ''Vendetta'', ''Waterhen'' and ''Wryneck'' could have met it at 0800 instead of 0915 hrs, increasing both its anti-aircraft fire and capacity to rescue survivors. The distance from Almyros allowed the same ''Stukas'' to make repeated attack runs, although on the flight back to base one stopped at Corinth

Corinth ( ; el, Κόρινθος, Kórinthos, ) is the successor to an ancient city, and is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform, it has been part o ...

to refuel. Increasing their round trip by 40 nautical miles might have marginally reduced the aircraft's ability to attack repeatedly.

The general situation was such that had ''Slamat'' left on time as ordered, it would have been more likely only to mitigate an attack rather than avert one. The Admiralty may have been as concerned at the general risk arising from Allied and civilian ships not following Royal Navy orders, as at any direct loss that Luidinga's delay may or may not have caused.

Awards and monuments

In November 1941 Philip Cartwright of HMS ''Diamond'' was posthumously made a Companion of theDistinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order (DSO) is a military decoration of the United Kingdom, as well as formerly of other parts of the Commonwealth, awarded for meritorious or distinguished service by officers of the armed forces during wartime, typ ...

. From HMS ''Wryneck'', Maurice Waldron received the Distinguished Service Cross The Distinguished Service Cross (D.S.C.) is a military decoration for courage. Different versions exist for different countries.

*Distinguished Service Cross (Australia)

The Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) is a military decoration awarded to ...

and George Fuller the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal

The Conspicuous Gallantry Medal (CGM) was, until 1993, a British military decoration for gallantry in action for petty officers and seamen of the Royal Navy, including Warrant Officers and other ranks of the Royal Marines. It was formerly awa ...

. The Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

took the unusual step of publishing in ''The London Gazette

''The London Gazette'' is one of the official journals of record or government gazettes of the Government of the United Kingdom, and the most important among such official journals in the United Kingdom, in which certain statutory notices are ...

'' its citation for Fuller: ''"who, though badly wounded, fought his gun till the last, and when his ship was sunk, heartened the survivors by his courage and cheerfulness"''.

In May 1945 the Netherlands were liberated and the Dutch government returned from exile. In August 1946 Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands

Wilhelmina (; Wilhelmina Helena Pauline Maria; 31 August 1880 – 28 November 1962) was Queen of the Netherlands from 1890 until her abdication in 1948. She reigned for nearly 58 years, longer than any other Dutch monarch. Her reign saw World War ...

wrote to Captain Luidinga's widow, expressing her sympathy for her husband's death, gratitude for his war service and commending him as ''een groot zoon van ons zeevarend volk'' ("a great son of our seafaring people").

British and Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

troops and naval personnel who were lost in the sinking of ''Slamat'', ''Diamond'' and ''Wryneck'' are named on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) is an intergovernmental organisation of six independent member states whose principal function is to mark, record and maintain the graves and places of commemoration of Commonwealth of Nations mil ...

's Athens Memorial in Phaleron Allied War Cemetery at Palaio Faliro

Palaio Faliro ( el, Παλαιό Φάληρο, ; Katharevousa: Palaion Faliron, Παλαιόν Φάληρον, meaning "Old Phalerum") is a coastal district and a municipality in the southern part of the Athens agglomeration, Greece. At the 2011 c ...

southeast of Athens. Royal Navy personnel are also commemorated in Britain on the Royal Navy monuments at Chatham

Chatham may refer to:

Places and jurisdictions Canada

* Chatham Islands (British Columbia)

* Chatham Sound, British Columbia

* Chatham, New Brunswick, a former town, now a neighbourhood of Miramichi

* Chatham (electoral district), New Brunswic ...

, Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth ...

and Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

. George Dexter commissioned a monument to all the service personnel lost when the three ships were sunk. It is in The Royal British Legion

The Royal British Legion (RBL), formerly the British Legion, is a British charity providing financial, social and emotional support to members and veterans of the British Armed Forces, their families and dependants, as well as all others in ne ...

Club, Shard End

Shard End is an area of Birmingham, England. It is also a ward within the formal district of Hodge Hill. Shard End borders Castle Bromwich to the north and Kingshurst to the east which are situated in the northern part of the neighbouring Metr ...

, Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the West ...

.

There was no Dutch monument to ''Slamat'' until 2011, when one commemorating victims from all three ships was made by the Dutch sculptor Nicolas van Ronkenstein. It was installed in the '' Sint-Laurenskerk'' ("St Lawrence Church"), Rotterdam and formally unveiled on the 70th anniversary of the disaster, 27 April.

On 27 June 2012 the current hosted a wreath-laying ceremony at the position where ''Slamat'' was sunk. Participants included ''Diamond''s commander, descendants of some of the dead from the Netherlands and New Zealand, and the Commander in Chief of the Hellenic Navy

The Hellenic Navy (HN; el, Πολεμικό Ναυτικό, Polemikó Naftikó, War Navy, abbreviated ΠΝ) is the naval force of Greece, part of the Hellenic Armed Forces. The modern Greek navy historically hails from the naval forces of vari ...

.

References

Sources and further reading

* * *{{cite book , last=Luidinga , first=Frans , year=1995 , title=Operation Demon. Het Scheepsjournal van Tjalling Luidinga 1890-1941. Gezagvoerder Bij de Rotterdamse Lloyd. , publisher=self-published , isbn=978-90-802461-2-6 , language=nl Battle of Greece Maritime incidents in April 1941 World War II shipwrecks in the Mediterranean Sea History of the Aegean Sea