Sir Peter Parker, 1st Baronet on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Peter Parker, 1st Baronet (1721 – 21 December 1811) was a

Parker transferred to the

Parker transferred to the

Knighted in 1772, Parker was given command of the second-rate HMS ''Barfleur'' when he rejoined the service in 1773. Promoted to commodore, he was deployed to the North American Station, with his

Knighted in 1772, Parker was given command of the second-rate HMS ''Barfleur'' when he rejoined the service in 1773. Promoted to commodore, he was deployed to the North American Station, with his

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by Kingdom of England, English and Kingdom of Scotland, Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were foug ...

officer. As a junior officer, he was deployed with a squadron under Admiral Edward Vernon

Admiral Edward Vernon (12 November 1684 – 30 October 1757) was an English naval officer. He had a long and distinguished career, rising to the rank of admiral after 46 years service. As a vice admiral during the War of Jenkins' Ear, in 1 ...

to the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Great ...

at the start of the War of Jenkins' Ear

The War of Jenkins' Ear, or , was a conflict lasting from 1739 to 1748 between Britain and the Spanish Empire. The majority of the fighting took place in New Granada and the Caribbean Sea, with major operations largely ended by 1742. It is con ...

. He saw action again at the Battle of Toulon during the War of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession () was a European conflict that took place between 1740 and 1748. Fought primarily in Central Europe, the Austrian Netherlands, Italy, the Atlantic and Mediterranean, related conflicts included King George' ...

. As captain of the fourth-rate

In 1603 all English warships with a compliment of fewer than 160 men were known as 'small ships'. In 1625/26 to establish pay rates for officers a six tier naval ship rating system was introduced.Winfield 2009 These small ships were divided i ...

HMS ''Bristol'' he took part in the Invasion of Guadeloupe during the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754– ...

.

As a commodore, he was deployed to the North American Station, to provide naval support for an expedition led by General Sir Henry Clinton reinforcing loyalists in the Southern Colonies at an early stage of the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of ...

. He led a naval attack against the fortifications on Sullivan's Island (later called Fort Moultrie

Fort Moultrie is a series of fortifications on Sullivan's Island, South Carolina, built to protect the city of Charleston, South Carolina. The first fort, formerly named Fort Sullivan, built of palmetto logs, inspired the flag and ni ...

after their commander), protecting Charleston, South Carolina. However, after a long and hard-fought battle, Parker was forced to call off the attack, having sustained heavy casualties, including the loss of a ship. He subsequently served under Lord Howe in the invasion and capture of New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the U ...

and commanded the squadron that captured Long Island and Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the smallest U.S. state by area and the seventh-least populous, with slightly fewer than 1.1 million residents as of 2020, but i ...

.

Parker went on to be Commander-in-Chief, Jamaica, before being returned as Member of Parliament for Seaford and then as member for Maldon. He later became Commander-in-Chief, Portsmouth

The Commander-in-Chief, Portsmouth, was a senior commander of the Royal Navy for hundreds of years. The commanders-in-chief were based at premises in High Street, Portsmouth from the 1790s until the end of Sir Thomas Williams's tenure, his succes ...

.

Early career

Born the third son of Rear-Admiral Christopher Parker, Parker joined the Royal Navy at an early age. Promoted tocommander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain ...

on 17 March 1735, he was deployed with a squadron under Admiral Edward Vernon

Admiral Edward Vernon (12 November 1684 – 30 October 1757) was an English naval officer. He had a long and distinguished career, rising to the rank of admiral after 46 years service. As a vice admiral during the War of Jenkins' Ear, in 1 ...

to the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Great ...

in 1739 at the start of the War of Jenkins' Ear

The War of Jenkins' Ear, or , was a conflict lasting from 1739 to 1748 between Britain and the Spanish Empire. The majority of the fighting took place in New Granada and the Caribbean Sea, with major operations largely ended by 1742. It is con ...

.Heathcote, p. 205

Parker transferred to the

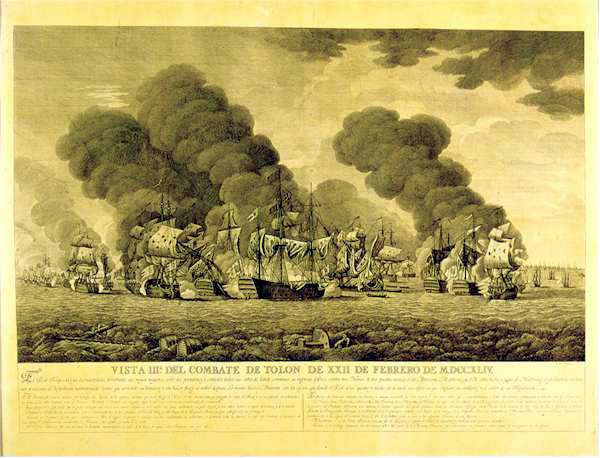

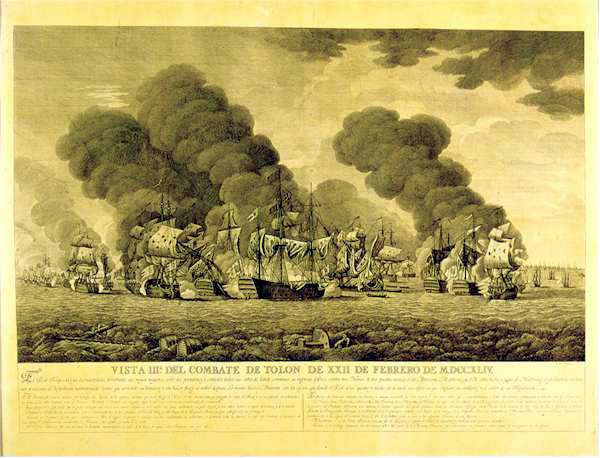

Parker transferred to the second-rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy used to categorise sailing warships, a second-rate was a ship of the line which by the start of the 18th century mounted 90 to 98 guns on three gun decks; earlier 17th-century second rates had fewer guns ...

HMS ''Russell'' and then to the bomb vessel

A bomb vessel, bomb ship, bomb ketch, or simply bomb was a type of wooden sailing naval ship. Its primary armament was not cannons (long guns or carronades) – although bomb vessels carried a few cannons for self-defence – but mortars moun ...

HMS ''Firedrake'' in the Mediterranean Fleet

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between t ...

and saw action again during the War of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession () was a European conflict that took place between 1740 and 1748. Fought primarily in Central Europe, the Austrian Netherlands, Italy, the Atlantic and Mediterranean, related conflicts included King George' ...

. He was moved to the second-rate HMS ''Barfleur'', flagship of Rear-Admiral William Rowley

William Rowley (c. 1585 – February 1626) was an English Jacobean dramatist, best known for works written in collaboration with more successful writers. His date of birth is estimated to have been c. 1585; he was buried on 11 February 1626 in ...

, in January 1744 and took part in the Battle of Toulon in February 1744, before transferring to the second-rate HMS ''Neptune'', flagship of Vice-Admiral Richard Lestock

Admiral Richard Lestock (22 February 1679 – 17 December 1746) was an officer in the Royal Navy, eventually rising to the rank of Admiral. He fought in a number of battles, and was a controversial figure, most remembered for his part in the de ...

, in March 1744 and returning to England. Promoted to captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

on 6 May 1747, he became commanding officer of the sixth-rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy used to categorise sailing warships, a sixth-rate was the designation for small warships mounting between 20 and 28 carriage-mounted guns on a single deck, sometimes with smaller guns on the upper works and ...

HMS ''Margate'' later that month and was deployed protecting commercial shipping, first in the Channel and then in the Mediterranean.

Parker became commanding officer of the fifth-rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy used to categorise sailing warships, a fifth rate was the second-smallest class of warships in a hierarchical system of six " ratings" based on size and firepower.

Rating

The rating system in the Royal ...

HMS ''Woolwich'' in 1757 and then transferred to the fourth-rate

In 1603 all English warships with a compliment of fewer than 160 men were known as 'small ships'. In 1625/26 to establish pay rates for officers a six tier naval ship rating system was introduced.Winfield 2009 These small ships were divided i ...

HMS ''Bristol'' in January 1759. In HMS ''Bristol'' he took part in the Invasion of Guadeloupe in May 1759 during the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754– ...

. He was given command of the third-rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy, a third rate was a ship of the line which from the 1720s mounted between 64 and 80 guns, typically built with two gun decks (thus the related term two-decker). Years of experience proved that the third ...

HMS ''Buckingham'' in 1760 and took part in the capture of Belle Île

The Capture of Belle Île was a British amphibious expedition to capture the French island of Belle Île off the Brittany coast in 1761, during the Seven Years' War. After an initial British attack was repulsed, a second attempt under General S ...

in Spring 1761. He transferred to the command of the third-rate HMS ''Terrible'' in 1762 and then retired from active service in 1763 at the end of the War.

American War of Independence

Knighted in 1772, Parker was given command of the second-rate HMS ''Barfleur'' when he rejoined the service in 1773. Promoted to commodore, he was deployed to the North American Station, with his

Knighted in 1772, Parker was given command of the second-rate HMS ''Barfleur'' when he rejoined the service in 1773. Promoted to commodore, he was deployed to the North American Station, with his broad pennant

A broad pennant is a triangular swallow-tailed naval pennant flown from the masthead of a warship afloat or a naval headquarters ashore to indicate the presence of either:

(a) a Royal Navy officer in the rank of Commodore, or

(b) a U.S. Nav ...

in the fourth-rate HMS ''Bristol'', in October 1775 to provide naval support for an expedition led by General Sir Henry Clinton reinforcing loyalists in the Southern Colonies at an early stage of the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of ...

.

In June 1776, Parker led a naval attack against the fortifications on Sullivan's Island (later called Fort Moultrie

Fort Moultrie is a series of fortifications on Sullivan's Island, South Carolina, built to protect the city of Charleston, South Carolina. The first fort, formerly named Fort Sullivan, built of palmetto logs, inspired the flag and ni ...

after their commander), protecting Charleston, South Carolina. At the fort, the American Colonel William Moultrie

William Moultrie (; November 23, 1730 – September 27, 1805) was an American planter and politician who became a general in the American Revolutionary War. As colonel leading a state militia, in 1776 he prevented the British from taking Charles ...

ordered his men to concentrate their fire on the two large man-of-war ships, HMS ''Bristol'' and HMS ''Experiment'', which took hit after hit from the fort's guns. Chain-shot fired at HMS ''Bristol'' eventually destroyed much of her rigging and severely damaged both the main- and mizzenmasts. After a long and hard-fought battle, Parker was forced to call off the attack, having sustained heavy casualties, including the loss of the sixth-rate HMS ''Actaeon'', grounded and abandoned. Lord William Campbell, the last British Governor of the Province of South Carolina

Province of South Carolina, originally known as Clarendon Province, was a province of Great Britain that existed in North America from 1712 to 1776. It was one of the five Southern colonies and one of the thirteen American colonies. The mona ...

, was mortally wounded aboard HMS ''Bristol''. Parker was himself wounded by a flying splinter which injured his leg and tore off his breeches, an incident that occasioned much mirth in the newspapers.

Parker subsequently served under Lord Howe in the invasion and capture of New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the U ...

and, with his broad pennant in the fourth-rate HMS ''Chatham'', he commanded the squadron that captured Long Island in August 1776 and Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the smallest U.S. state by area and the seventh-least populous, with slightly fewer than 1.1 million residents as of 2020, but i ...

in December 1776.

Senior command

Promoted torear admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star " admiral" rank. It is often rega ...

on 20 May 1777, Parker became Commander-in-Chief, Jamaica Station

Jamaica station is a major train station of the Long Island Rail Road located in Jamaica, Queens, New York City. With weekday ridership exceeding 200,000 passengers, it is the largest transit hub on Long Island, the fourth-busiest rail stati ...

, with his flag in HMS ''Bristol'', in December 1777. At this time, Parker acted as a patron and friend of Horatio Nelson

Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte (29 September 1758 – 21 October 1805) was a British flag officer in the Royal Navy. His inspirational leadership, grasp of strategy, and unconventional tactics brought ...

, then serving aboard the ''Bristol'', an attachment which would endure for the remainder of Nelson's life. Promoted to vice admiral on 29 March 1779, he returned to England in the second-rate HMS ''Sandwich'', accompanied by various prisoners including Admiral De Grasse captured at the Battle of the Saintes

The Battle of the Saintes (known to the French as the Bataille de la Dominique), also known as the Battle of Dominica, was an important naval battle in the Caribbean between the British and the French that took place 9–12 April 1782. The Brit ...

, in August 1782.Heathcote, p. 206

Created a baronet

A baronet ( or ; abbreviated Bart or Bt) or the female equivalent, a baronetess (, , or ; abbreviation Btss), is the holder of a baronetcy, a hereditary title awarded by the British Crown. The title of baronet is mentioned as early as the 14th ...

on 28 December 1782, Parker was, unwillingly, returned as Member of Parliament for Seaford in May 1784, and then as member for Maldon in 1786. Promoted to full admiral on 24 September 1787, he became Commander-in-Chief, Portsmouth

The Commander-in-Chief, Portsmouth, was a senior commander of the Royal Navy for hundreds of years. The commanders-in-chief were based at premises in High Street, Portsmouth from the 1790s until the end of Sir Thomas Williams's tenure, his succes ...

in 1793. He was promoted to Admiral of the Fleet on 16 September 1799 and was Chief Mourner at Nelson's funeral in January 1806. He died at his home at Weymouth Street

Weymouth Street lies in the Marylebone district of the City of Westminster and connects Marylebone High Street with Great Portland Street. The area was developed in the late 18th century by Henrietta Cavendish Holles and her husband Edward H ...

in London on 21 December 1811 and was buried at St Margaret's, Westminster

The Church of St Margaret, Westminster Abbey, is in the grounds of Westminster Abbey on Parliament Square, London, England. It is dedicated to Margaret of Antioch, and forms part of a single World Heritage Site with the Palace of Westminster ...

. Parker also owned the Manor of Bassingbourne at Takeley

__NOTOC__

Takeley is a village and civil parish in the Uttlesford district of Essex, England.

History

A number of theories have arisen over the origin of the village's name. One believes the village's name was a corruption from the "Teg-Ley" ...

in Essex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and G ...

: in accordance with his wishes the manor was demolished in 1813.

Family

In around 1761 Parker married Margaret Nugent; they had several children (including Vice-Admiral Christopher Parker). He was succeeded in the baronetcy by Christopher's son Peter Parker.Notes

References

* * * *External links

* * * , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Parker, Sir Peter Parker, 1st Baronet First Sea Lords and Chiefs of the Naval Staff Royal Navy admirals of the fleet Royal Navy personnel of the American Revolutionary War Members of the Parliament of Great Britain for English constituencies Parker, Sir Peter, 1st Baronet 1721 births 1811 deaths Royal Navy personnel of the Seven Years' War British MPs 1784–1790 Members of Parliament for Maldon