Sir Mordred on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Mordred or Modred (; Welsh: ''Medraut'' or ''Medrawt'') is a figure who is variously portrayed in the legend of

In Geoffrey's influential ''Historia Regum Britanniae'' (''The History of the Kings of Britain''), written around 1136, Modredus (Mordred) is portrayed as the nephew of and traitor to King Arthur. Geoffrey might have based his Modredus on the early 6th-century " high king" of

In Geoffrey's influential ''Historia Regum Britanniae'' (''The History of the Kings of Britain''), written around 1136, Modredus (Mordred) is portrayed as the nephew of and traitor to King Arthur. Geoffrey might have based his Modredus on the early 6th-century " high king" of

Traditions vary on Mordred's relationship to Arthur. Medraut is never considered Arthur's son in Welsh texts, only his nephew, though ''

Traditions vary on Mordred's relationship to Arthur. Medraut is never considered Arthur's son in Welsh texts, only his nephew, though '' Gawain is Mordred's brother already in the ''Historia'' as well as in

Gawain is Mordred's brother already in the ''Historia'' as well as in

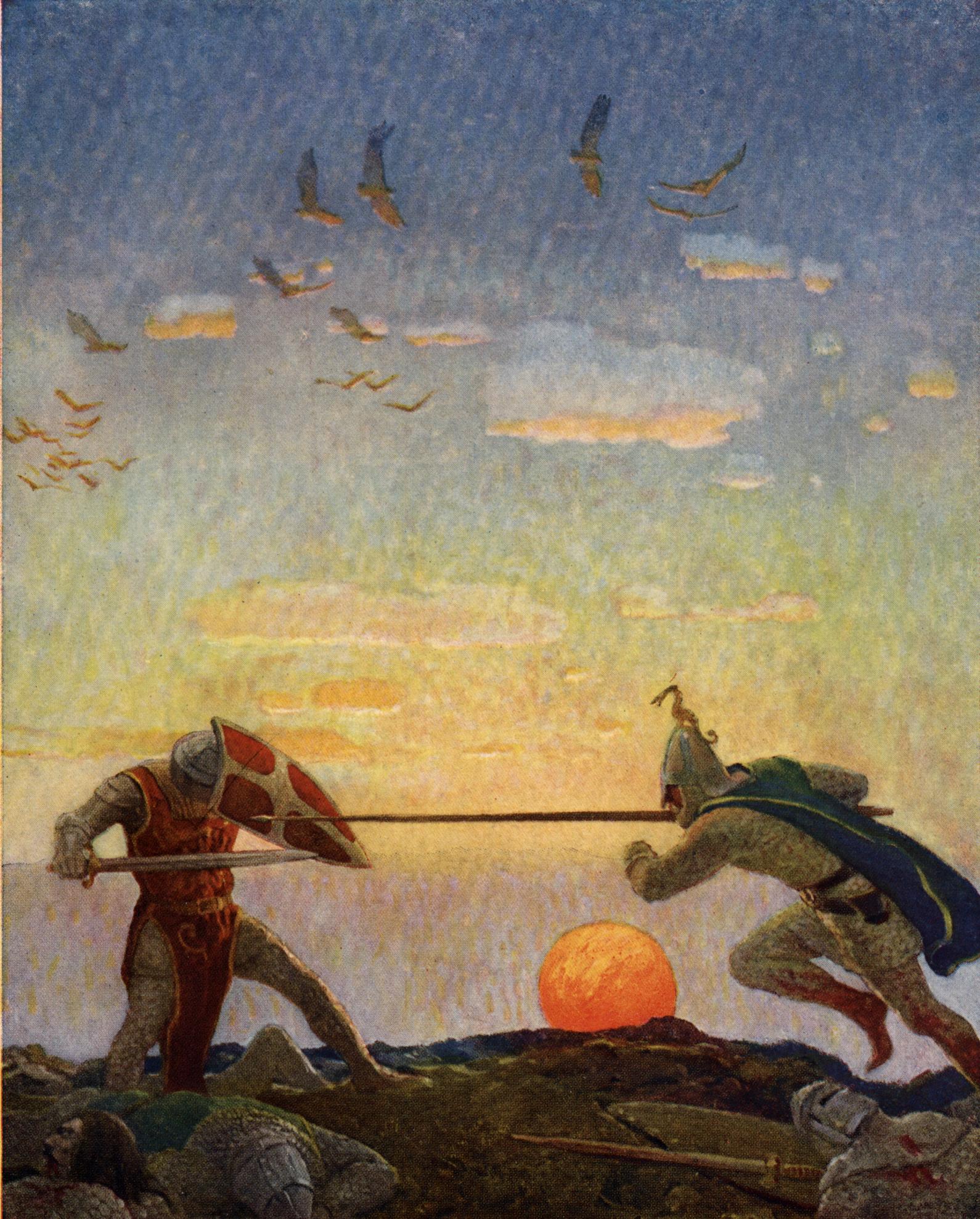

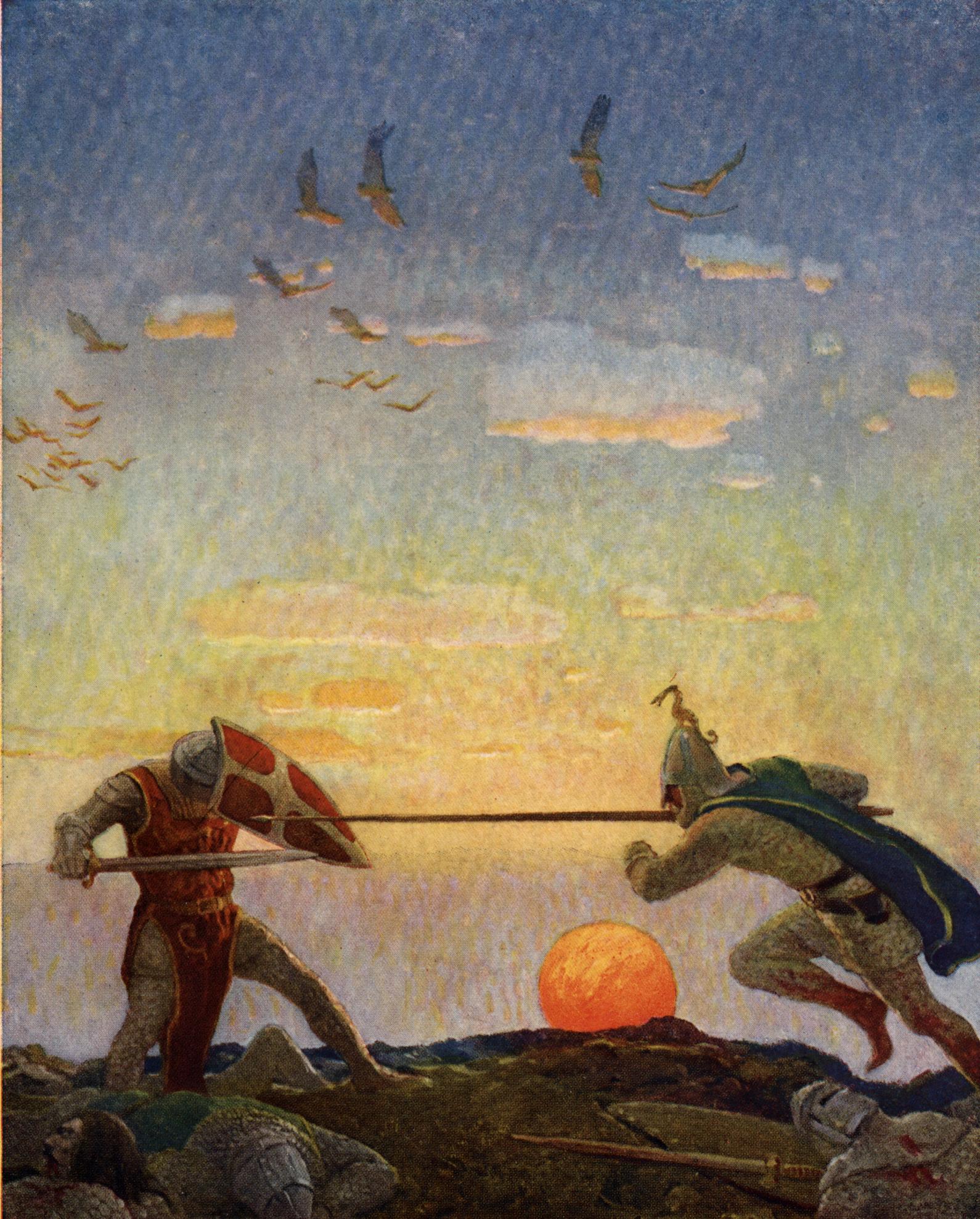

''Le Morte d'Arthur'' features the now iconic scene where the two meet on foot as Arthur charges Mordred and runs a spear through him. With the last of his strength, Mordred impales himself even further to be within striking distance, and lands a mortal blow with his sword to King Arthur's head. Malory's telling is a variant of the original account from the Vulgate ''Mort Artu'', in which Arthur and Mordred both charge at each other on horses three times until Arthur drives his lance through Mordred's body, but then fully withdraws it (a ray of sunlight even shines through the hole) before Mordred's sword powerfully strikes his head and they both fall from their saddles. The Alliterative ''Morte Arthure'' has Mordred grievously wound Arthur with the ceremonial sword Clarent, stolen for him from Arthur by his co-conspirator Guinevere, but then Arthur slashes off Mordred's sword arm and brutally skewers him up on the sword Caliburn (

''Le Morte d'Arthur'' features the now iconic scene where the two meet on foot as Arthur charges Mordred and runs a spear through him. With the last of his strength, Mordred impales himself even further to be within striking distance, and lands a mortal blow with his sword to King Arthur's head. Malory's telling is a variant of the original account from the Vulgate ''Mort Artu'', in which Arthur and Mordred both charge at each other on horses three times until Arthur drives his lance through Mordred's body, but then fully withdraws it (a ray of sunlight even shines through the hole) before Mordred's sword powerfully strikes his head and they both fall from their saddles. The Alliterative ''Morte Arthure'' has Mordred grievously wound Arthur with the ceremonial sword Clarent, stolen for him from Arthur by his co-conspirator Guinevere, but then Arthur slashes off Mordred's sword arm and brutally skewers him up on the sword Caliburn (

Virtually everywhere Mordred appears, his name is synonymous with

Virtually everywhere Mordred appears, his name is synonymous with

Mordred

at The Camelot Project

{{Authority control Arthurian characters Fictional cannibals Fictional characters who committed sedition or treason Fictional offspring of incestuous relationships Fictional patricides King Arthur's family Knights of the Round Table Male characters in literature Male characters in television Male literary villains Mythological kings Mythological princes Mythological swordfighters

King Arthur

King Arthur ( cy, Brenin Arthur, kw, Arthur Gernow, br, Roue Arzhur) is a legendary king of Britain, and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In the earliest traditions, Arthur appears as a ...

. The earliest known mention of a possibly historical Medraut is in the Welsh chronicle ''Annales Cambriae

The (Latin for ''Annals of Wales'') is the title given to a complex of Latin chronicles compiled or derived from diverse sources at St David's in Dyfed, Wales. The earliest is a 12th-century presumed copy of a mid-10th-century original; later ed ...

'', wherein he and Arthur are ambiguously associated with the Battle of Camlann

The Battle of Camlann ( cy, Gwaith Camlan or ''Brwydr Camlan'') is the legendary final battle of King Arthur, in which Arthur either died or was fatally wounded while fighting either with or against Mordred, who also perished. The original leg ...

in a brief entry for the year 537. Medraut's figure seemed to have been regarded positively in the early Welsh tradition and may have been related to that of Arthur's son.

As Modredus, Mordred was depicted as Arthur's traitorous nephew and a legitimate son of King Lot

King Lot , also spelled Loth or Lott (Lleu or Llew in Welsh), is a British monarch in Arthurian legend. He was introduced in Geoffrey of Monmouth's influential chronicle ''Historia Regum Britanniae'' that portrayed him as King Arthur's brother- ...

in Geoffrey of Monmouth

Geoffrey of Monmouth ( la, Galfridus Monemutensis, Galfridus Arturus, cy, Gruffudd ap Arthur, Sieffre o Fynwy; 1095 – 1155) was a British cleric from Monmouth, Wales and one of the major figures in the development of British historiograph ...

's pseudo-historical work ''Historia Regum Britanniae

''Historia regum Britanniae'' (''The History of the Kings of Britain''), originally called ''De gestis Britonum'' (''On the Deeds of the Britons''), is a pseudohistorical account of British history, written around 1136 by Geoffrey of Monmouth. I ...

'' which then served as the basis for the following evolution of the legend from the 12th century. Later variants most often characterised him as Arthur's villainous bastard son, born of an incestuous relationship with his half-sister, the queen of Lothian

Lothian (; sco, Lowden, Loudan, -en, -o(u)n; gd, Lodainn ) is a region of the Scottish Lowlands, lying between the southern shore of the Firth of Forth and the Lammermuir Hills and the Moorfoot Hills. The principal settlement is the Sco ...

or Orkney

Orkney (; sco, Orkney; on, Orkneyjar; nrn, Orknøjar), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated off the north coast of the island of Great Britain. Orkney is 10 miles (16 km) north ...

named either Anna, Orcades, or Morgause. The accounts presented in the ''Historia'' and most other versions include Mordred's death at Camlann, typically in a final duel, during which he manages to mortally wound his own slayer, Arthur.

Mordred is usually a brother or half-brother to Gawain

Gawain (), also known in many other forms and spellings, is a character in Arthurian legend, in which he is King Arthur's nephew and a Knight of the Round Table. The prototype of Gawain is mentioned under the name Gwalchmei in the earliest ...

; however, his other family relations, as well as his relationships with Arthur's wife Guinevere

Guinevere ( ; cy, Gwenhwyfar ; br, Gwenivar, kw, Gwynnever), also often written in Modern English as Guenevere or Guenever, was, according to Arthurian legend, an early-medieval queen of Great Britain and the wife of King Arthur. First ment ...

, vary greatly. In a popular telling originating from the French chivalric romances of the 13th century, and made prominent today through its inclusion in ''Le Morte d'Arthur

' (originally written as '; inaccurate Middle French for "The Death of Arthur") is a 15th-century Middle English prose reworking by Sir Thomas Malory of tales about the legendary King Arthur, Guinevere, Lancelot, Merlin and the Knights of the Rou ...

'', Mordred is knighted by Arthur and joins the fellowship of the Round Table

The Round Table ( cy, y Ford Gron; kw, an Moos Krenn; br, an Daol Grenn; la, Mensa Rotunda) is King Arthur's famed table in the Arthurian legend, around which he and his knights congregate. As its name suggests, it has no head, implying that e ...

. In this narrative, he eventually becomes the main actor in Arthur's downfall: he helps his half-brother Agravain

Sir Agravain () is a Knight of the Round Table in Arthurian legend, whose first known appearance is in the works of Chrétien de Troyes. He is the second eldest son of King Lot of Orkney with one of King Arthur's sisters known as Anna or Mor ...

to expose the affair between Guinevere and Lancelot

Lancelot du Lac (French for Lancelot of the Lake), also written as Launcelot and other variants (such as early German ''Lanzelet'', early French ''Lanselos'', early Welsh ''Lanslod Lak'', Italian ''Lancillotto'', Spanish ''Lanzarote del Lago' ...

, and then takes advantage of the resulting civil war to make himself the high king of Britain.

Name

The name ''Mordred'', found as the Latinised ''Modredus'' inGeoffrey of Monmouth

Geoffrey of Monmouth ( la, Galfridus Monemutensis, Galfridus Arturus, cy, Gruffudd ap Arthur, Sieffre o Fynwy; 1095 – 1155) was a British cleric from Monmouth, Wales and one of the major figures in the development of British historiograph ...

's ''Historia Regum Britanniae

''Historia regum Britanniae'' (''The History of the Kings of Britain''), originally called ''De gestis Britonum'' (''On the Deeds of the Britons''), is a pseudohistorical account of British history, written around 1136 by Geoffrey of Monmouth. I ...

'', comes from Old Welsh

Old Welsh ( cy, Hen Gymraeg) is the stage of the Welsh language from about 800 AD until the early 12th century when it developed into Middle Welsh.Koch, p. 1757. The preceding period, from the time Welsh became distinct from Common Brittonic ...

''Medraut'' (comparable to Old Cornish

Cornish (Standard Written Form: or ) , is a Southwestern Brittonic language of the Celtic language family. It is a revived language, having become extinct as a living community language in Cornwall at the end of the 18th century. However, k ...

''Modred'' and Old Breton

Breton (, ; or in Morbihan) is a Southwestern Brittonic language of the Celtic language family spoken in Brittany, part of modern-day France. It is the only Celtic language still widely in use on the European mainland, albeit as a member of t ...

''Modrot''). It may be ultimately derived from Latin ''Moderātus'', meaning "within bounds, observing moderation, moderate" with some influence from Latin ''mors'', death.

Early Welsh sources

The earliest surviving mention of Mordred (referred to as Medraut) is found in an entry for the year 537 in the chronicle ''Annales Cambriae

The (Latin for ''Annals of Wales'') is the title given to a complex of Latin chronicles compiled or derived from diverse sources at St David's in Dyfed, Wales. The earliest is a 12th-century presumed copy of a mid-10th-century original; later ed ...

'' (''The Annals of Wales''), which references his name in an association with the Battle of Camlann

The Battle of Camlann ( cy, Gwaith Camlan or ''Brwydr Camlan'') is the legendary final battle of King Arthur, in which Arthur either died or was fatally wounded while fighting either with or against Mordred, who also perished. The original leg ...

.

This brief entry gives no information as to whether Mordred killed or was killed by Arthur, or even if he was fighting against him. As noted by Leslie Alcock

Leslie Alcock (24 April 1925 – 6 June 2006) was Professor of Archaeology at the University of Glasgow, and one of the leading archaeologists of Early Medieval Britain. His major excavations included Dinas Powys hill fort in Wales, Cadbury Ca ...

, the reader assumes this in the light of later tradition. The ''Annales'' themselves were completed between 960 and 970, meaning that (although their authors likely drew from older material) they cannot be considered as a contemporary source having been compiled 400 years after the events they describe.

Meilyr Brydydd

Meilyr Brydydd ap Mabon ( fl. 1100–1137) is the earliest of the Welsh Poets of the Princes or ''Y Gogynfeirdd'' (The Less Early Poets) whose work has survived.

Meilyr was the court poet of Gruffudd ap Cynan (ca. 1055–1137), king of Gwynedd. ...

, writing at the same time as Geoffrey of Monmouth, mentions Mordred in his lament for the death of Gruffudd ap Cynan

Gruffudd ap Cynan ( 1137), sometimes written as Gruffydd ap Cynan, was King of Gwynedd from 1081 until his death in 1137. In the course of a long and eventful life, he became a key figure in Welsh resistance to Norman rule, and was remembe ...

(d. 1137). He describes Gruffudd as having ''eissor Medrawd'' ("the nature of Medrawd") as to have valour in battle. Similarly, Gwalchmai ap Meilyr

Gwalchmai ap Meilyr (fl. 1130 – 1180) was a Welsh-language court poet, connected with Trewalchmai in Anglesey. He was one of the earliest of the ''Gogynfeirdd'' ("less early poets") or ''Beirdd y Tywysogion'' ("Poets of the Princes"). He compose ...

praised Madog ap Maredudd

Madog ap Maredudd ( wlm, Madawg mab Maredud, ; died 1160) was the last prince of the entire Kingdom of Powys, Wales and for a time held the Fitzalan Lordship of Oswestry.

Madog was the son of King Maredudd ap Bleddyn and grandson of King Bleddy ...

, king of Powys

Powys (; ) is a Local government in Wales#Principal areas, county and Preserved counties of Wales, preserved county in Wales. It is named after the Kingdom of Powys which was a Welsh succession of states, successor state, petty kingdom and princi ...

(d. 1160) as having ''Arthur gerdernyd, menwyd Medrawd'' ("Arthur's strength, the good nature of Medrawd"). This would support the idea that early perceptions of Mordred were largely positive.

However, Mordred's later characterisation as the king's villainous son has a precedent in the figure of Amr or Amhar, a son of Arthur's known from only two references. The more important of these, found in an appendix to the 9th-century chronicle ''Historia Brittonum

''The History of the Britons'' ( la, Historia Brittonum) is a purported history of the indigenous British (Brittonic) people that was written around 828 and survives in numerous recensions that date from after the 11th century. The ''Historia Bri ...

'' (''The History of the Britons''), describes his marvelous grave beside the Herefordshire

Herefordshire () is a county in the West Midlands of England, governed by Herefordshire Council. It is bordered by Shropshire to the north, Worcestershire to the east, Gloucestershire to the south-east, and the Welsh counties of Monmouthshire ...

spring where he had been slain by his own father in some unchronicled tragedy. What connection exists between the stories of Amr and Mordred, if there is one, has never been satisfactorily explained.

Depictions in legend

In Geoffrey's influential ''Historia Regum Britanniae'' (''The History of the Kings of Britain''), written around 1136, Modredus (Mordred) is portrayed as the nephew of and traitor to King Arthur. Geoffrey might have based his Modredus on the early 6th-century " high king" of

In Geoffrey's influential ''Historia Regum Britanniae'' (''The History of the Kings of Britain''), written around 1136, Modredus (Mordred) is portrayed as the nephew of and traitor to King Arthur. Geoffrey might have based his Modredus on the early 6th-century " high king" of Gwynedd

Gwynedd (; ) is a county and preserved county (latter with differing boundaries; includes the Isle of Anglesey) in the north-west of Wales. It shares borders with Powys, Conwy County Borough, Denbighshire, Anglesey over the Menai Strait, and C ...

, Maglocunus ( Maelgwn), whom the 6th-century writer Gildas

Gildas ( Breton: ''Gweltaz''; c. 450/500 – c. 570) — also known as Gildas the Wise or ''Gildas Sapiens'' — was a 6th-century British monk best known for his scathing religious polemic ''De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae'', which recount ...

had described as an usurper

A usurper is an illegitimate or controversial claimant to power, often but not always in a monarchy. In other words, one who takes the power of a country, city, or established region for oneself, without any formal or legal right to claim it as ...

, or on Mandubracius

Mandubracius or Mandubratius was a king of the Trinovantes of south-eastern Prehistoric Britain, Britain in the 1st century BC.

History

Mandubracius was the son of a Trinovantian king, named Imanuentius in some manuscripts of Julius Caesar's '' ...

, a 1st-century BC king of the Trinovantes

The Trinovantēs (Common Brittonic: *''Trinowantī'') or Trinobantes were one of the Celtic tribes of Pre-Roman Britain. Their territory was on the north side of the Thames estuary in current Essex, Hertfordshire and Suffolk, and included lan ...

. The unhistorical account presented by Geoffrey narrates Arthur leaving Modredus in charge of his throne as he crossed the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

to wage war on Lucius Tiberius

Lucius ( el, Λούκιος ''Loukios''; ett, Luvcie) is a male given name derived from ''Lucius'' (abbreviated ''L.''), one of the small group of common Latin forenames (''praenomina'') found in the culture of ancient Rome. Lucius derives from L ...

of Rome. During Arthur's absence, Modredus crowns himself king and lives in an adulterous union with Arthur's wife, Ganhumara (Guinevere

Guinevere ( ; cy, Gwenhwyfar ; br, Gwenivar, kw, Gwynnever), also often written in Modern English as Guenevere or Guenever, was, according to Arthurian legend, an early-medieval queen of Great Britain and the wife of King Arthur. First ment ...

). Geoffrey does not make it clear how complicit Ganhumara is with his actions, simply stating that the Queen had "broken her vows" and "about this matter... eprefers to say nothing." This forces Arthur to return to Britain to fight at the Battle of Camlann, where Modredus is ultimately slain. Arthur, having been gravely wounded in battle, is sent off to be healed by Morgen ( Morgan) in Avalon

Avalon (; la, Insula Avallonis; cy, Ynys Afallon, Ynys Afallach; kw, Enys Avalow; literally meaning "the isle of fruit r appletrees"; also written ''Avallon'' or ''Avilion'' among various other spellings) is a mythical island featured in the ...

.

A number of Welsh sources also refer to Medraut, usually in relation to Camlann. One Welsh Triad, based on Geoffrey's ''Historia'', provides an account of his betrayal of Arthur; in another, he is described as the author of one of the "Three Unrestrained Ravagings of the Isle of Britain" – he came to Arthur's court at Kelliwic in Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic ...

, devoured all of the food and drink, and even dragged Gwenhwyfar (Guinevere) from her throne and beat her. In another Triad, however, he is described as one of "men of such gentle, kindly, and fair words that anyone would be sorry to refuse them anything." The ''Mabinogion

The ''Mabinogion'' () are the earliest Welsh prose stories, and belong to the Matter of Britain. The stories were compiled in Middle Welsh in the 12th–13th centuries from earlier oral traditions. There are two main source manuscripts, create ...

'' also describes him in the terms of courtliness, calmness and purity.

Life in romances

In the early 13th century, theOld French

Old French (, , ; Modern French: ) was the language spoken in most of the northern half of France from approximately the 8th to the 14th centuries. Rather than a unified language, Old French was a linkage of Romance dialects, mutually intelligib ...

cyclical literature of the chivalric romance

As a literary genre, the chivalric romance is a type of prose and verse narrative that was popular in the noble courts of High Medieval and Early Modern Europe. They were fantastic stories about marvel-filled adventures, often of a chivalric k ...

genre expanded on the history of Mordred prior to the war against Arthur. In the Prose ''Merlin'' part of the Vulgate Cycle

The ''Lancelot-Grail'', also known as the Vulgate Cycle or the Pseudo-Map Cycle, is an early 13th-century French Arthurian literary cycle consisting of interconnected prose episodes of chivalric romance in Old French. The cycle of unknown author ...

(in which his name is sometimes written as "Mordret"), Mordred's elder half-brother Gawain

Gawain (), also known in many other forms and spellings, is a character in Arthurian legend, in which he is King Arthur's nephew and a Knight of the Round Table. The prototype of Gawain is mentioned under the name Gwalchmei in the earliest ...

saves the infant Mordred and their mother Morgause

The Queen of Orkney, today best known as Morgause and also known as Morgawse and other spellings and names, is a character in later Arthurian traditions. In some versions of the legend, including the seminal text ''Le Morte d'Arthur'', she is ...

from being taken by the Saxon

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

king Taurus. In the revision known as the Post-Vulgate Cycle

The ''Post-Vulgate Cycle'', also known as the Post-Vulgate Arthuriad, the Post-Vulgate ''Roman du Graal'' (''Romance of the Grail'') or the Pseudo-Robert de Boron Cycle, is one of the major Old French prose cycles of Arthurian literature from th ...

, and consequently in Thomas Malory

Sir Thomas Malory was an English writer, the author of '' Le Morte d'Arthur'', the classic English-language chronicle of the Arthurian legend, compiled and in most cases translated from French sources. The most popular version of '' Le Morte d' ...

's English compilation ''Le Morte d'Arthur

' (originally written as '; inaccurate Middle French for "The Death of Arthur") is a 15th-century Middle English prose reworking by Sir Thomas Malory of tales about the legendary King Arthur, Guinevere, Lancelot, Merlin and the Knights of the Rou ...

'' (''The Death of Arthur''), Arthur is told a cryptic (and, apparently, self-fulfilling) prophecy by Merlin

Merlin ( cy, Myrddin, kw, Marzhin, br, Merzhin) is a mythical figure prominently featured in the legend of King Arthur and best known as a mage, with several other main roles. His usual depiction, based on an amalgamation of historic and le ...

about a just-born child that is to be his undoing, and so he tries to avert the fate by ordering to get rid of all the May Day

May Day is a European festival of ancient origins marking the beginning of summer, usually celebrated on 1 May, around halfway between the spring equinox and summer solstice. Festivities may also be held the night before, known as May Eve. T ...

newborns. Whether they were just supposed to be just sent off to a distant land, or was it actually the plan for them to die at the sea all along (the texts are vague about this), the ship on which they were placed does indeed sink and the children drown. This episode (reminiscent of the Biblical Massacre of the Innocents and sometimes dubbed the "May Day massacre") leads to a war between Arthur and the furious King Lot

King Lot , also spelled Loth or Lott (Lleu or Llew in Welsh), is a British monarch in Arthurian legend. He was introduced in Geoffrey of Monmouth's influential chronicle ''Historia Regum Britanniae'' that portrayed him as King Arthur's brother- ...

(acting on his belief that he was biological father of Mordred), in which the latter king dies in a battle at the hands of Arthur's vassal king Pellinore

King Pellinore (alternatively ''Pellinor'', ''Pellynore'' and other variants) is the king of Listenoise (possibly the Lake District) or of "the Isles" (possibly Anglesey, or perhaps the medieval kingdom of the same name) in Arthurian legend. In ...

, beginning a long and deadly blood feud between the two royal families (Lot's and Pellinore's). Yet, unknown to both Lot and Arthur, the baby Mordred has actually miraculously survived. He is accidentally found and rescued by a fisherman and his wife, who then raise him as their own son until he is 14. In this branch of the legend, following his early life as a commoner, the young Mordred is later reunited with his mother (this happens long after Merlin's downfall caused by the Lady of the Lake

The Lady of the Lake (french: Dame du Lac, Demoiselle du Lac, cy, Arglwyddes y Llyn, kw, Arloedhes an Lynn, br, Itron al Lenn, it, Dama del Lago) is a name or a title used by several either fairy or fairy-like but human enchantresses in the ...

).

Mordred becomes involved in the adventures of his brothers (having grown to become the tallest among them), first as a squire

In the Middle Ages, a squire was the shield- or armour-bearer of a knight.

Use of the term evolved over time. Initially, a squire served as a knight's apprentice. Later, a village leader or a lord of the manor might come to be known as a " ...

and then as a knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the Gr ...

, as well as others such as Brunor

Brunor, Breunor, Branor or Brunoro are various forms of a name given to several different characters in the works of the Tristan tradition of Arthurian legend. They include Knight of the Round Table known as ''Brunor/Breunor le Noir'' (the Black ...

. Eventually, Mordred joins King Arthur's elite fellowship of the Knights of the Round Table

The Knights of the Round Table ( cy, Marchogion y Ford Gron, kw, Marghekyon an Moos Krenn, br, Marc'hegien an Daol Grenn) are the knights of the fellowship of King Arthur in the literary cycle of the Matter of Britain. First appearing in lit ...

. Since the Post-Vulgate, however, he tends to be depicted as murderously violent and known for his lustful habits, including engaging in rape, as in an incident in the Post-Vulgate ''Queste'' when he brutally kills a maiden and is injured for this by King Bagdemagus

Bagdemagus (pronounced /ˈbægdɛˌmægəs/), also known as Bademagu(s/z), Bagdemagu, Bagomedés, Baldemagu(s), Bandemagu(s), Bangdemagew, Baudemagu(s), and other variants (such as the Italian ''Bando di Mago'' or the Hebrew ''Bano of Magoç''), ...

who is then in turn mortally wounded by Gawain (there is also an attempted rape in the standalone romance ''Claris et Laris''). Notably, it is Mordred who stabs in the back and kills Pellinore's son and one of the best Knights of the Round Table, Lamorak

Sir Lamorak (or Lamerak, Lamorac(k), Lamorat, Lamerocke, and other spellings) is a Knight of the Round Table in Arthurian legend. Introduced in the Prose ''Tristan'', Lamorak reappears in later works including the ''Post-Vulgate Cycle'' and T ...

, in an unfair fight involving most of his brothers ( one of whom had even murdered their own mother for being Lamorak's lover). Mordred displays better knightly values in the Vulgate Cycle (as does Gawain too in comparison to his later Post-Vulgate portrayal), where he is shown as also womanising and murderous but to a significantly lesser degree. In the Prose ''Lancelot'', he becomes a protege and companion of the eponymous greatest knight Lancelot

Lancelot du Lac (French for Lancelot of the Lake), also written as Launcelot and other variants (such as early German ''Lanzelet'', early French ''Lanselos'', early Welsh ''Lanslod Lak'', Italian ''Lancillotto'', Spanish ''Lanzarote del Lago' ...

. The older knight comes to the young Mordred's rescue on multiple occasions, such as helping to save his life at the Castle of the White Thorn (''Castel de la Blanche Espine''), and Mordred in turn treats the much older Lancelot as his personal hero. In this version, his turning point toward villainy happens after they meet an old hermit monk who tells his own prophecy for the two "most unfortunate knights", revealing Mordred's true parentage by Arthur and predicting Mordred's and Lancelot's respective roles in the coming ruin of Arthur's kingdom. However, the angry Mordred kills the priest before he can finish telling it. While Lancelot tells his secret lover Guinevere (but not Arthur), she refuses to believe in the story of the prophecy and does not banish Mordred. The young knight, on his part, tries to get himself killed before accepting his destiny. The Prose ''Lancelot'' indicates Mordred was about 22 years old at the time (two years into his knighthood).

Mordred eventually overthrows Arthur's rule when the latter is engaged in the war against Lancelot (or during the second Roman War that followed it, depending on the version). In the Vulgate ''Mort Artu'', Mordred achieves his coup with the help of a forged letter supposedly sent by Arthur. The text adds that "there was much good in Mordred, and as soon as he made himself elevated go the throne, he made himself well beloved by all," and so they were "ready to die to defend ishonor" once Arthur returned with his army. Mordred's few opponents during his brief rule included Kay, who was gravely wounded by Mordred's supporters and died after fleeing to Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo language, Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, Historical region, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known ...

. In the French-influenced English poem Stanzaic ''Morte Arthur'', a council of Britain's knights first elects Mordred for the position of regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

in Arthur's absence as the most worthy candidate. As in the chronicles, the returning Arthur will go to war against King Mordred. After Mordred's supporters and foreign allies ambush and nearly destroy Arthur's veteran army landing at Dover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maidstone ...

(where Gawain is mortally wounded, fighting as Arthur's loyalist), a series of inconclusive engagements follows, until both sides agree to all meet each other at the one final battle.

Family relations

The Dream of Rhonabwy

''The Dream of Rhonabwy'' ( cy, Breuddwyd Rhonabwy) is a Middle Welsh prose tale. Set during the reign of Madog ap Maredudd, prince of Powys (died 1160), its composition is typically dated to somewhere between the late 12th through the late 14th c ...

'' mentions that the king had been his foster father. In early literature derived from Geoffrey's ''Historia'', Mordred was considered the legitimate son of Arthur's sister or half-sister queen variably known as Anna or Morgause (Orcades / Morcades / Morgawse / Margawse) with her husband, Lot (Loth), the king of either Lothian

Lothian (; sco, Lowden, Loudan, -en, -o(u)n; gd, Lodainn ) is a region of the Scottish Lowlands, lying between the southern shore of the Firth of Forth and the Lammermuir Hills and the Moorfoot Hills. The principal settlement is the Sco ...

or Orkney

Orkney (; sco, Orkney; on, Orkneyjar; nrn, Orknøjar), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated off the north coast of the island of Great Britain. Orkney is 10 miles (16 km) north ...

. Today, however, he is best known as Arthur's own illegitimate son by Morgause in the motif introduced in the Vulgate Cycle, in which their union happens at the time when neither of them have yet known of their blood relation.

Gawain is Mordred's brother already in the ''Historia'' as well as in

Gawain is Mordred's brother already in the ''Historia'' as well as in Layamon

Layamon or Laghamon (, ; ) – spelled Laȝamon or Laȝamonn in his time, occasionally written Lawman – was an English poet of the late 12th/early 13th century and author of the ''Brut'', a notable work that was the first to present the legend ...

's ''Brut''. Besides him, Mordred's other brothers or half-brothers are Agravain

Sir Agravain () is a Knight of the Round Table in Arthurian legend, whose first known appearance is in the works of Chrétien de Troyes. He is the second eldest son of King Lot of Orkney with one of King Arthur's sisters known as Anna or Mor ...

, Gaheris

Gaheris (Old French: ''Gaheriet'', ''Gaheriés'', ''Guerrehes'') is a knight of the Round Table in the chivalric romance tradition of Arthurian legend. A nephew of King Arthur, Gaheris is the third son of Arthur's sister or half-sister Morgau ...

, and Gareth in the later tradition derived from the French romance cycles, beginning with the prose versions of Robert de Boron

Robert de Boron (also spelled in the manuscripts "Roberz", "Borron", "Bouron", "Beron") was a French poet of the late 12th and early 13th centuries, notable as the reputed author of the poems and ''Merlin''. Although little is known of him apart f ...

's poems ''Merlin

Merlin ( cy, Myrddin, kw, Marzhin, br, Merzhin) is a mythical figure prominently featured in the legend of King Arthur and best known as a mage, with several other main roles. His usual depiction, based on an amalgamation of historic and le ...

'' and ''Perceval''. In the Vulgate ''Lancelot'', Mordred is the youngest of the siblings who begins his knightly career as Agravain's own squire, and the two will later conspire together to reveal Lancelot's affair with Guinevere (which will result in Agravain's death by Lancelot and will lead to the civil war between Arthur's and Lancelot's faction). In stark contrast to many modern works, Mordred's only interaction with Morgan le Fay

Morgan le Fay (, meaning 'Morgan the Fairy'), alternatively known as Morgan , Morgain /e Morg e, Morgant Morge , and Morgue namong other names and spellings ( cy, Morgên y Dylwythen Deg, kw, Morgen an Spyrys), is a powerful ...

in any medieval text occurs when he and his brothers visit Morgan's castle in the Post-Vulgate ''Queste'', which is when they are informed about Guinevere's infidelity for Arthur (in the Vulgate version, Morgan tells her brother personally).

The 14th-century Scottish chronicler John of Fordun

John of Fordun (before 1360 – c. 1384) was a Scottish chronicler. It is generally stated that he was born at Fordoun, Mearns. It is certain that he was a secular priest, and that he composed his history in the latter part of the 14th cen ...

claimed that Mordred was the rightful heir to the throne of Britain, as Arthur was an illegitimate child (in his account, Mordred was the legitimate son of Lot and Anna, who here is Uther's sister). This sentiment was elaborated upon by Walter Bower

Walter Bower (or Bowmaker; 24 December 1449) was a Scottish canon regular and abbot of Inchcolm Abbey in the Firth of Forth, who is noted as a chronicler of his era. He was born about 1385 at Haddington, East Lothian, in the Kingdom of Scotlan ...

and by Hector Boece

Hector Boece (; also spelled Boyce or Boise; 1465–1536), known in Latin as Hector Boecius or Boethius, was a Scottish philosopher and historian, and the first Principal of King's College in Aberdeen, a predecessor of the University of Abe ...

, who in his ''Historia Gentis Scotorum'' goes so far as to say Arthur and Mordred's brother Gawain were traitors and villains and Arthur usurped the throne from Mordred. According to Boece, Arthur agreed to make Mordred his heir but then, on the advice of the Britons who did not want Mordred to rule, he made Constantine

Constantine most often refers to:

* Constantine the Great, Roman emperor from 306 to 337, also known as Constantine I

*Constantine, Algeria, a city in Algeria

Constantine may also refer to:

People

* Constantine (name), a masculine given name ...

his heir; this led to the war in which Arthur and Mordred die.

In the ''Historia'' and certain other texts, such as the Alliterative ''Morte Arthure'' reimagination of the ''Historia'' where Mordred is portrayed sympathetically, Mordred marries Guinevere consensually after he takes the throne. However, in later writings like the Lancelot-Grail

The ''Lancelot-Grail'', also known as the Vulgate Cycle or the Pseudo-Map Cycle, is an early 13th-century French Arthurian literary cycle consisting of interconnected prose episodes of chivalric romance in Old French. The cycle of unknown authors ...

Cycle and ''Le Morte d'Arthur'', Guinevere is not treated as a traitor and instead she flees Mordred's proposal and hides in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separa ...

. Adultery is still tied to her role in these later romances, but Mordred has been replaced in this role by Lancelot.

The 18th-century Welsh antiquarian Lewis Morris

Lewis Morris (April 8, 1726 – January 22, 1798) was an American Founding Father, landowner, and developer from Morrisania, New York, presently part of Bronx County. He signed the U.S. Declaration of Independence as a delegate to the Continen ...

, based on statements made by the Scottish chronicler Boece, suggested that Medrawd had a wife named Cwyllog Saint Cwyllog (or Cywyllog)Baring-Gould, p. 279. was a Christian holy woman who was active in Anglesey, Wales, in the early 6th century. The daughter, sister and niece of saints, she is said to have founded St Cwyllog's Church, Llangwyllog, in the ...

, daughter of Caw. Another late Welsh tradition was that Medrawd's wife was Gwenhwy(f)ach, sister of Guinevere.

Death

InHenry of Huntingdon

Henry of Huntingdon ( la, Henricus Huntindoniensis; 1088 – AD 1157), the son of a canon in the diocese of Lincoln, was a 12th-century English historian and the author of ''Historia Anglorum'' (Medieval Latin for "History of the English"), ...

's retelling of Geoffrey's ''Historia'', Mordred is beheaded at Camlann in a lone charge against him and his entire host by Arthur himself, who suffers many injuries in the process. In the Alliterative ''Morte Arthure'', Mordred first kills Gawain by his own hand in an early battle against Arthur's landing forces and then deeply grieves after him. In the Vulgate ''Mort Artu'' (and consequently in Malory's ''Le Morte d'Arthur''), the terrible final battle begins by an accident during a last-effort peace meeting between him and Arthur. In the ensuing fighting, Mordred personally slays his cousin Yvain

Sir Ywain , also known as Yvain and Owain among other spellings (''Ewaine'', ''Ivain'', ''Ivan'', ''Iwain'', ''Iwein'', ''Uwain'', ''Uwaine'', etc.), is a Knight of the Round Table in Arthurian legend, wherein he is often the son of King Urien ...

after the latter's rescue of the unhorsed Arthur and then he decapitates the already badly wounded Sagramore. He also kills Sagramore as well as six other Round Table knights loyal to Arthur in the Post-Vulgate version, which presents this as an incredible and unprecedented feat. These and many other versions of the legend feature the motif of Arthur and Mordred striking down each other in a duel after most of the others on both sides have died. Furthermore, the Post-Vulgate says it was only the death of Sagramore, here depicted as Mordred's own foster brother, that finally motivated Arthur to kill his son immediately afterwards.

''Le Morte d'Arthur'' features the now iconic scene where the two meet on foot as Arthur charges Mordred and runs a spear through him. With the last of his strength, Mordred impales himself even further to be within striking distance, and lands a mortal blow with his sword to King Arthur's head. Malory's telling is a variant of the original account from the Vulgate ''Mort Artu'', in which Arthur and Mordred both charge at each other on horses three times until Arthur drives his lance through Mordred's body, but then fully withdraws it (a ray of sunlight even shines through the hole) before Mordred's sword powerfully strikes his head and they both fall from their saddles. The Alliterative ''Morte Arthure'' has Mordred grievously wound Arthur with the ceremonial sword Clarent, stolen for him from Arthur by his co-conspirator Guinevere, but then Arthur slashes off Mordred's sword arm and brutally skewers him up on the sword Caliburn (

''Le Morte d'Arthur'' features the now iconic scene where the two meet on foot as Arthur charges Mordred and runs a spear through him. With the last of his strength, Mordred impales himself even further to be within striking distance, and lands a mortal blow with his sword to King Arthur's head. Malory's telling is a variant of the original account from the Vulgate ''Mort Artu'', in which Arthur and Mordred both charge at each other on horses three times until Arthur drives his lance through Mordred's body, but then fully withdraws it (a ray of sunlight even shines through the hole) before Mordred's sword powerfully strikes his head and they both fall from their saddles. The Alliterative ''Morte Arthure'' has Mordred grievously wound Arthur with the ceremonial sword Clarent, stolen for him from Arthur by his co-conspirator Guinevere, but then Arthur slashes off Mordred's sword arm and brutally skewers him up on the sword Caliburn (Excalibur

Excalibur () is the legendary sword of King Arthur, sometimes also attributed with magical powers or associated with the rightful sovereignty of Britain. It was associated with the Arthurian legend very early on. Excalibur and the Sword in th ...

). One copy of the Welsh text ''Ymddiddan Arthur a'r Eryr'' has the dying Arthur tell Guinevere that he struck Mordred nine times with Caledfwlch (another name variant of Excalibur).

The Post-Vulgate retelling of ''Mort Artu'' deals with the aftermath of Mordred's death in more detail than the earlier works. In it, Arthur says before being taken away: "Mordred, in an evil hour did I beget you. You have ruined me and the kingdom of Logres

Logres (among various other forms and spellings) is King Arthur's realm in the Matter of Britain. It derives from the medieval Welsh word ''Lloegyr'', a name of uncertain origin referring to South and Eastern England (''Lloegr'' in modern Welsh ...

, and you have died for it. Cursed be the hour in which you were born." One of the few survivors of Arthur's army, Bleoberis

The Knights of the Round Table ( cy, Marchogion y Ford Gron, kw, Marghekyon an Moos Krenn, br, Marc'hegien an Daol Grenn) are the knights of the fellowship of King Arthur in the literary cycle of the Matter of Britain. First appearing in lit ...

, then drags Mordred's corpse behind a horse around the battlefield of Salisbury Plain

Salisbury Plain is a chalk plateau in the south western part of central southern England covering . It is part of a system of chalk downlands throughout eastern and southern England formed by the rocks of the Chalk Group and largely lies wi ...

until it is torn to pieces. Later, as it had been commanded by the dying Arthur, the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Justi ...

constructs the Tower of the Dead tomb memorial, from which Bleoberis hangs Mordred's head as a warning against treason and there it then remains for centuries until it is removed by the visiting Ganelon

In the Matter of France, Ganelon (, ) is the knight who betrayed Charlemagne's army to the Saracens, leading to the Battle of Roncevaux Pass. His name is said to derive from the Italian word ''inganno'', meaning fraud or deception.Boiardo, ''Orl ...

. Conversely, Margam Abbey

Margam Abbey ( cy, Abaty Margam) was a Cistercian monastery, located in the village of Margam, a suburb of modern Port Talbot in Wales.

History

The abbey was founded in 1147 as a daughter house of Clairvaux by Robert, Earl of Gloucester ...

's chronicle ''Annales de Margan'' claims Arthur had been buried alongside Mordred, here described as his nephew, in another tomb purportedly exhumed in the "real Avalon" at Glastonbury Abbey

Glastonbury Abbey was a monastery in Glastonbury, Somerset, England. Its ruins, a grade I listed building and scheduled ancient monument, are open as a visitor attraction.

The abbey was founded in the 8th century and enlarged in the 10th. It wa ...

.

There have been also alternative stories of Mordred's demise. In the Italian ''La Tavola Ritonda ''La Tavola Ritonda'' (''The Round Table'') is a 15th-century Italian Arthurian romance written in the medieval Tuscan language. It is preserved in a 1446 manuscript at the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale in Florence (''Codex Palatinus 556''). It wa ...

'' (''The Round Table''), it is Lancelot who kills Mordred at Castle Urbano where Mordred has besieged Guinevere after Arthur's death. In ''Ly Myreur des Histors'' (''The Mirror of History'') by Belgian writer Jean d'Outremeuse

Jean d'Outremeuse or ''Jean des Preis'' (1338 in Liège – 1400) was a writer and historian who wrote two romanticised historical works and a lapidary (text), lapidary.

''La Geste de Liége'' is an account of the mythical history of his native ci ...

, Mordred survives the great battle and rules with the traitorous Guinevere until they are defeated and captured by Lancelot and King Carados in London. Guinevere is then executed by Lancelot and Mordred is entombed alive with her body, which he consumes before dying of starvation.

Offspring

Since Geoffrey, Mordred is often said to be succeeded by his sons. Stories always number them as two, though they are usually not named, nor is their mother. In Geoffrey's version, after the Battle of Camlann, Constantine is appointed Arthur's successor. However, Mordred's two sons and their Saxon allies later rise against him. After they are defeated, one of them flees to sanctuary in the Church of Amphibalus inWinchester

Winchester is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs Nation ...

while the other hides in a London friary. ''Historia Regum Britanniae'', Book 11, ch. 4. Constantine tracks them down, and kills them before the altars of their respective hiding places. This act invokes the vengeance of God, and three years later Constantine is killed by his nephew Aurelius Conanus

Aurelius Conanus or Aurelius Caninus was a Brittonic king in 6th-century sub-Roman Britain. The only certain historical record of him is in the writings of his contemporary Gildas, who excoriates him as a tyrant. However, he may be identified with ...

. Geoffrey's account of the episode may be based on Constantine's murder of two "royal youths" as mentioned by Gildas. ''De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae'', ch. 28–29. In the Alliterative ''Morte Arthure'', the dying Arthur personally orders Constantine to kill Mordred's infant children as Guinevere had been asked by Mordred to flee with them to Ireland. Guinevere instead returns to Caerleon

Caerleon (; cy, Caerllion) is a town and community in Newport, Wales. Situated on the River Usk, it lies northeast of Newport city centre, and southeast of Cwmbran. Caerleon is of archaeological importance, being the site of a notable Roman ...

without a concern for the children.

The elder of Mordred's sons is named Melehan (evolved from Melou in Layamon's ''Brut'') in the Lancelot-Grail and the Post-Vulgate. In a battle near Winchester

Winchester is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs Nation ...

, Melehan slays Lionel, brother to Bors

Bors (; french: link=no, Bohort) is the name of two knights in Arthurian legend, an elder and a younger. The two first appear in the 13th-century Lancelot-Grail romance prose cycle. Bors the Elder is the King of Gaunnes (Gannes/Gaunes/Ganis) du ...

the Younger; Bors kills Melehan, avenging his brother's death, while Lancelot kills the unnamed younger brother who tried to escape deep into a forest. In the 15th-century Spanish chivalric romance ''Florambel de Lucea'', the surviving Arthur is rescued by his sister Morgan in a battle against the sons of Mordred (Morderec).

In later works

treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

. He appears in Dante's ''Inferno'' in the lowest circle of Hell, set apart for traitors: "him who, at one blow, had chest and shadow / shattered by Arthur's hand" (Canto XXXII). Mordred is especially prominent in popular modern era Arthurian literature, as well as in film, television, and comics. He has been portrayed on screen by (among others) Leonard Penn

Leonard Penn (13 November 1907 – 20 May 1975) was an American film, television and theatre actor.

Early life and education

Penn was born in Springfield, Massachusetts, to parents Marcus Penn and Eva Monson. He majored in drama at Columbia U ...

(''The Adventures of Sir Galahad

''Adventures of Sir Galahad'' is the 41st serial released in 1949 by Columbia Pictures. Directed by Spencer Gordon Bennet, it stars George Reeves, Nelson Leigh, William Fawcett, Hugh Prosser, and Lois Hall. It was based on Arthurian legend, one o ...

'', 1949), Brian Worth (''The Adventures of Sir Lancelot

''The Adventures of Sir Lancelot'' is a British television series first broadcast in 1956, produced by Sapphire Films for ITC Entertainment and screened on the ITV network. The series starred William Russell as the eponymous Sir Lancelot, a Kn ...

'', 1956–1957), David Hemmings (''Camelot

Camelot is a castle and court associated with the legendary King Arthur. Absent in the early Arthurian material, Camelot first appeared in 12th-century French romances and, since the Lancelot-Grail cycle, eventually came to be described as the ...

'', 1967), Robert Addie

Robert Alastair Addie (10 February 1960 – 20 November 2003) was an English film and theatre actor, who came to prominence playing the role of Sir Guy of Gisbourne in the 1980s British television drama series ''Robin of Sherwood''.

Early life ...

(''Excalibur

Excalibur () is the legendary sword of King Arthur, sometimes also attributed with magical powers or associated with the rightful sovereignty of Britain. It was associated with the Arthurian legend very early on. Excalibur and the Sword in th ...

'', 1981), Nickolas Grace

Nickolas Andrew Halliwell Grace (born 21 November 1947) is an English actor known for his roles on television, including Anthony Blanche in the acclaimed ITV adaptation of ''Brideshead Revisited'', and the Sheriff of Nottingham in the 1980s seri ...

(''Morte d'Arthur'', 1984), Simon Templeman

Simon Templeman (born January 28, 1954) is an English actor. He is known for his video game roles as Kain (Legacy of Kain), Kain in ''Legacy of Kain'', Gabriel Roman in ''Uncharted: Drake's Fortune'', Loghain in ''Dragon Age'' and Admiral Han'G ...

(''The Legend of Prince Valiant

''The Legend of Prince Valiant'' is a 1991–1993 American animated television series based on the ''Prince Valiant'' comic strip created by Hal Foster. Set in the time of King Arthur, it is a family-oriented adventure show about an exiled prince ...

'', 1991–1993), Jason Done

Jason Done (born 5 April 1973) is an English actor who appeared as Mordred in the 1998 TV miniseries ''Merlin'', opposite Sam Neill. He is best known for his role as Stephen Snow in ITV drama '' Where The Heart Is'' from 1999 to 2001 and Tom ...

(''Merlin

Merlin ( cy, Myrddin, kw, Marzhin, br, Merzhin) is a mythical figure prominently featured in the legend of King Arthur and best known as a mage, with several other main roles. His usual depiction, based on an amalgamation of historic and le ...

'', 1998), Craig Sheffer

Craig Eric Sheffer (born April 23, 1960) is an American film and television actor. He is known for his leading roles as Norman Maclean in the film ''A River Runs Through It (film), A River Runs Through It, ''Aaron Boone in the film ''Nightbreed' ...

('' Merlin: The Return'', 2000), Hans Matheson

Hans Matheson (born 7 August 1975) is a Scottish actor and musician. In a wide-ranging film and television career he has taken lead roles in diverse films such as '' Doctor Zhivago'', '' Sherlock Holmes'', '' The Tudors'', '' Tess of the d'Urb ...

(''The Mists of Avalon

''The Mists of Avalon'' is a 1983 historical fantasy novel by American writer Marion Zimmer Bradley, in which the author relates the Arthurian legends from the perspective of the female characters. The book follows the trajectory of Morgaine (Mo ...

'', 2001), and Asa Butterfield

Asa Bopp Farr Butterfield (; born Asa Maxwell Thornton Farr Butterfield on 1 April 1997) is an English actor. He has received nominations for three British Independent Film Awards, two Critics' Choice Awards, two Saturn Awards, and three Young ...

and Alexander Vlahos (''Merlin

Merlin ( cy, Myrddin, kw, Marzhin, br, Merzhin) is a mythical figure prominently featured in the legend of King Arthur and best known as a mage, with several other main roles. His usual depiction, based on an amalgamation of historic and le ...

'', 2008–2012). In such modern adaptations, Morgause is often conflated with (and into) the character of Morgan le Fay, who may be Mordred's mother or alternatively his lover or wife. A few works of the Middle Ages and today, however, portray Mordred as less a traitor and more a conflicted opportunist, or even a victim of fate. Even Malory, who depicts Mordred as a villain, notes that the people rallied to him because, "with Arthur was none other life but war and strife, and with Sir Mordred was great joy and bliss."

See also

*Illegitimacy in fiction

This is a list of fictional stories in which illegitimacy features as an important plot element. Passing mentions are omitted from this article. Many of these stories explore the social pain and exclusion felt by illegitimate "natural children".

...

* King Arthur's family

References

Citations

Bibliography

* Bromwich, Rachel (2006). ''Trioedd Ynys Prydein: The Triads of the Island of Britain''. University of Wales Press. *Lacy, Norris J. Norris J. Lacy (born March 8, 1940 in Hopkinsville, Kentucky) is an American scholar focusing on France, French medieval literature. He was the Edwin Erle Sparks Professor Emeritus of French and Medieval Studies at the Pennsylvania State University ...

(Ed.), ''The New Arthurian Encyclopedia'', pp. 8–9. New York: Garland. .

*Lacy, Norris J.; Ashe, Geoffrey; and Mancroff, Debra N. (1997). ''The Arthurian Handbook''. New York: Garland. .

External links

Mordred

at The Camelot Project

{{Authority control Arthurian characters Fictional cannibals Fictional characters who committed sedition or treason Fictional offspring of incestuous relationships Fictional patricides King Arthur's family Knights of the Round Table Male characters in literature Male characters in television Male literary villains Mythological kings Mythological princes Mythological swordfighters