Sir Henry Morgan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Henry Morgan ( cy, Harri Morgan; – 25 August 1688) was a

It is probable that in the early 1660s Morgan was active with a group of privateers led by Sir

It is probable that in the early 1660s Morgan was active with a group of privateers led by Sir

After the action, one of the English privateers quarrelled with one of his French shipmates and stabbed him in the back, killing him. Before a riot between the French and English sailors could begin, Morgan arrested the English sailor, and promised the French sailors that the man would be hanged on his return to Port Royal. Morgan kept his word and the sailor was hanged. After dividing the spoils of the conquest of Puerto Principe, Morgan announced a plan to attack Porto Bello (now in modern-day Panama). The city was the third largest and strongest on the

After the action, one of the English privateers quarrelled with one of his French shipmates and stabbed him in the back, killing him. Before a riot between the French and English sailors could begin, Morgan arrested the English sailor, and promised the French sailors that the man would be hanged on his return to Port Royal. Morgan kept his word and the sailor was hanged. After dividing the spoils of the conquest of Puerto Principe, Morgan announced a plan to attack Porto Bello (now in modern-day Panama). The city was the third largest and strongest on the  Morgan and his men remained in Porto Bello for a month. He wrote to Don Agustín, the acting president of Panama, to demand a ransom for the city of 350,000

Morgan and his men remained in Porto Bello for a month. He wrote to Don Agustín, the acting president of Panama, to demand a ransom for the city of 350,000

Morgan did not stay long in Port Royal and in October 1668 sailed with ten ships and 800 men for

Morgan did not stay long in Port Royal and in October 1668 sailed with ten ships and 800 men for  Morgan arrived at Maracaibo to find the city largely deserted, its residents having been forewarned of his approach by the fortress's troops. He spent three weeks sacking the city. Privateers searched the surrounding jungle to find the escapees; they, and some of the remaining occupants, were tortured to find where money or treasure had been hidden. Satisfied he had stolen all he could, he sailed south across Lake Maracaibo, to Gibraltar. The town's occupants refused to surrender, and the fort fired enough of a barrage to ensure Morgan kept his distance. He anchored a short distance away and his men landed by canoe and assaulted the town from the landward approach. He met scant resistance, as many of the occupants had fled into the surrounding jungle. He spent five weeks in Gibraltar, and there was again evidence that torture was used to force residents to reveal hidden money and valuables.

Four days after he left Maracaibo, Morgan returned. He was told that a Spanish defence squadron, the Armada de Barlovento, was waiting for him at the narrow passage between the Caribbean and Lake Maracaibo, where the San Carlos de la Barra Fortress was sited. The forces, under the command of Don Alonso del Campo y Espinosa, had 126 cannon with which to attack Morgan, and had re-armed San Carlos de la Barra Fortress. The Spaniards had orders to end piracy in the Caribbean, and negotiations between Morgan and Espinosa continued for a week. The final offer put by the Spanish commander was for Morgan to leave all their spoils and slaves and to return to Jamaica unmolested, but no agreement was reached that would allow Morgan and his men to pass the fleet with their spoils but without attack. Morgan put the Spaniards' offers to his men, who voted instead to fight their way out. As they were heavily outgunned, one privateer suggested that a

Morgan arrived at Maracaibo to find the city largely deserted, its residents having been forewarned of his approach by the fortress's troops. He spent three weeks sacking the city. Privateers searched the surrounding jungle to find the escapees; they, and some of the remaining occupants, were tortured to find where money or treasure had been hidden. Satisfied he had stolen all he could, he sailed south across Lake Maracaibo, to Gibraltar. The town's occupants refused to surrender, and the fort fired enough of a barrage to ensure Morgan kept his distance. He anchored a short distance away and his men landed by canoe and assaulted the town from the landward approach. He met scant resistance, as many of the occupants had fled into the surrounding jungle. He spent five weeks in Gibraltar, and there was again evidence that torture was used to force residents to reveal hidden money and valuables.

Four days after he left Maracaibo, Morgan returned. He was told that a Spanish defence squadron, the Armada de Barlovento, was waiting for him at the narrow passage between the Caribbean and Lake Maracaibo, where the San Carlos de la Barra Fortress was sited. The forces, under the command of Don Alonso del Campo y Espinosa, had 126 cannon with which to attack Morgan, and had re-armed San Carlos de la Barra Fortress. The Spaniards had orders to end piracy in the Caribbean, and negotiations between Morgan and Espinosa continued for a week. The final offer put by the Spanish commander was for Morgan to leave all their spoils and slaves and to return to Jamaica unmolested, but no agreement was reached that would allow Morgan and his men to pass the fleet with their spoils but without attack. Morgan put the Spaniards' offers to his men, who voted instead to fight their way out. As they were heavily outgunned, one privateer suggested that a  On 1 May 1669 Morgan and his flotilla attacked the Spanish squadron. The fire ship plan worked, and ''Magdalen'' was shortly aflame; Espinosa abandoned his flagship and made his way to the fort, where he continued to direct events. The second-largest Spanish ship, ''Soledad'', tried to move away from the burning vessel, but a problem with the rigging meant they drifted aimlessly; privateers boarded the ship, fixed the rigging and claimed the craft as plunder. The third Spanish vessel was also sunk by the privateers. Morgan still needed to pass the San Carlos de la Barra Fortress, but was still out-gunned by the stronghold, which had the ability to destroy the privateer fleet if it tried to pass. The privateer decided to negotiate, and threatened to sack and burn Maracaibo if he was not allowed to pass. Although Espinosa refused to negotiate, the citizens of Maracaibo entered into talks with Morgan, and agreed to pay him 20,000 pesos and 500 head of cattle if he agreed to leave the city intact. During the course of the negotiations with the Maracaibos, Morgan had undertaken salvage operations on ''Magdalen'', and secured 15,000 pesos from the wreck. Before taking any action, Morgan tallied his takings and divided it equally between his ships, to ensure that it was not all lost if one ship was sunk; it totalled 250,000 pesos, and a huge quantity of merchandise and a number of local slaves.

Morgan observed that Espinosa had set his cannon for a landward attack from the privateers – as they had done previously. The privateers faked a landing of their forces. The fort and its battlements were stripped of men as the Spanish prepared for a night assault from the English forces. That evening, with Spanish forces deployed to repel a landing, Morgan's fleet raised anchor without unfurling their sails; the fleet moved on the tide, raising sail only when it had moved level with the fortress, and Morgan and his men made their way back to Port Royal unscathed. Zahedieh considers the escape showed Morgan's "characteristic cunning and audacity".

During his absence from Port Royal, a pro-Spanish faction had gained the ear of King Charles II, and English foreign policy had changed accordingly. Modyford admonished Morgan for his action, which had gone beyond his commission, and revoked the letters of marque; no official action was taken against any of the privateers. Morgan invested a share of his

On 1 May 1669 Morgan and his flotilla attacked the Spanish squadron. The fire ship plan worked, and ''Magdalen'' was shortly aflame; Espinosa abandoned his flagship and made his way to the fort, where he continued to direct events. The second-largest Spanish ship, ''Soledad'', tried to move away from the burning vessel, but a problem with the rigging meant they drifted aimlessly; privateers boarded the ship, fixed the rigging and claimed the craft as plunder. The third Spanish vessel was also sunk by the privateers. Morgan still needed to pass the San Carlos de la Barra Fortress, but was still out-gunned by the stronghold, which had the ability to destroy the privateer fleet if it tried to pass. The privateer decided to negotiate, and threatened to sack and burn Maracaibo if he was not allowed to pass. Although Espinosa refused to negotiate, the citizens of Maracaibo entered into talks with Morgan, and agreed to pay him 20,000 pesos and 500 head of cattle if he agreed to leave the city intact. During the course of the negotiations with the Maracaibos, Morgan had undertaken salvage operations on ''Magdalen'', and secured 15,000 pesos from the wreck. Before taking any action, Morgan tallied his takings and divided it equally between his ships, to ensure that it was not all lost if one ship was sunk; it totalled 250,000 pesos, and a huge quantity of merchandise and a number of local slaves.

Morgan observed that Espinosa had set his cannon for a landward attack from the privateers – as they had done previously. The privateers faked a landing of their forces. The fort and its battlements were stripped of men as the Spanish prepared for a night assault from the English forces. That evening, with Spanish forces deployed to repel a landing, Morgan's fleet raised anchor without unfurling their sails; the fleet moved on the tide, raising sail only when it had moved level with the fortress, and Morgan and his men made their way back to Port Royal unscathed. Zahedieh considers the escape showed Morgan's "characteristic cunning and audacity".

During his absence from Port Royal, a pro-Spanish faction had gained the ear of King Charles II, and English foreign policy had changed accordingly. Modyford admonished Morgan for his action, which had gone beyond his commission, and revoked the letters of marque; no official action was taken against any of the privateers. Morgan invested a share of his

In 1669 Mariana, the Queen Regent of Spain, ordered attacks on English shipping in the Caribbean. The first action took place in March 1670 when Spanish privateers attacked English trade ships. In response Modyford commissioned Morgan "to do and perform all manner of exploits, which may tend to the preservation and quiet of this island". By December Morgan was sailing toward the Spanish Main with a fleet of over 30 English and French ships carrying a large number of privateers. Zahedieh observes that the army of privateers was the largest that had gathered in the Caribbean at the time, which was "a mark of Morgan's renown".

Morgan's first action was to take the connected islands of Old Providence and Santa Catalina in December 1670. From there his fleet sailed to

In 1669 Mariana, the Queen Regent of Spain, ordered attacks on English shipping in the Caribbean. The first action took place in March 1670 when Spanish privateers attacked English trade ships. In response Modyford commissioned Morgan "to do and perform all manner of exploits, which may tend to the preservation and quiet of this island". By December Morgan was sailing toward the Spanish Main with a fleet of over 30 English and French ships carrying a large number of privateers. Zahedieh observes that the army of privateers was the largest that had gathered in the Caribbean at the time, which was "a mark of Morgan's renown".

Morgan's first action was to take the connected islands of Old Providence and Santa Catalina in December 1670. From there his fleet sailed to  Panama's governor had sworn to burn down the city if his troops lost to the privateers, and he had placed barrels of gunpowder around the largely wooden buildings. These were detonated by the captain of artillery after Morgan's victory; the resultant fires lasted until the following day. Only a few stone buildings remained standing afterwards. Much of Panama's wealth was destroyed in the conflagration, although some had been removed by ships, before the privateers arrived. The privateers spent three weeks in Panama and plundered what they could from the ruins. Morgan's second-in-command, Captain Edward Collier, supervised the torture of some of the city's residents; Morgan's fleet surgeon, Richard Browne, later wrote that at Panama, Morgan "was noble enough to the vanquished enemy".

The value of treasure Morgan collected during his expedition is disputed. Talty writes that the figures range from 140,000 to 400,000 pesos, and that owing to the large army Morgan assembled, the prize-per-man was relatively low, causing discontent. There were accusations, particularly in Exquemelin's memoirs, that Morgan left with the majority of the plunder. He arrived back in Port Royal on 12 March to a positive welcome from the town's inhabitants. The following month he made his official report to the governing Council of Jamaica, and received their formal thanks and congratulations.

Panama's governor had sworn to burn down the city if his troops lost to the privateers, and he had placed barrels of gunpowder around the largely wooden buildings. These were detonated by the captain of artillery after Morgan's victory; the resultant fires lasted until the following day. Only a few stone buildings remained standing afterwards. Much of Panama's wealth was destroyed in the conflagration, although some had been removed by ships, before the privateers arrived. The privateers spent three weeks in Panama and plundered what they could from the ruins. Morgan's second-in-command, Captain Edward Collier, supervised the torture of some of the city's residents; Morgan's fleet surgeon, Richard Browne, later wrote that at Panama, Morgan "was noble enough to the vanquished enemy".

The value of treasure Morgan collected during his expedition is disputed. Talty writes that the figures range from 140,000 to 400,000 pesos, and that owing to the large army Morgan assembled, the prize-per-man was relatively low, causing discontent. There were accusations, particularly in Exquemelin's memoirs, that Morgan left with the majority of the plunder. He arrived back in Port Royal on 12 March to a positive welcome from the town's inhabitants. The following month he made his official report to the governing Council of Jamaica, and received their formal thanks and congratulations.

During Morgan's absence from Jamaica, news reached the island that England and Spain had signed the Treaty of Madrid. The pact aimed to establish peace in the Caribbean between the two countries; it included an agreement to revoke all letters of marque and similar commissions. The historian

During Morgan's absence from Jamaica, news reached the island that England and Spain had signed the Treaty of Madrid. The pact aimed to establish peace in the Caribbean between the two countries; it included an agreement to revoke all letters of marque and similar commissions. The historian

On his arrival in Jamaica, the 12-man Assembly of Jamaica voted Morgan an annual salary of £600 "for his good services to the country"; the move angered Carbery, who did not get on with Morgan. Carbery later complained of his deputy that he was "every day more convinced of ... organ'simprudence and unfitness to have anything to do with civil government". Carbery also wrote to the Secretary of State to bemoan Morgan's "drinking and gaming at the taverns" of Port Royal.

Although Morgan had been ordered to eradicate piracy from Jamaican waters, he continued his friendly relations with many privateer captains, and invested in some of their ships. Zahedieh estimates that there were 1,200 privateers operating in the Caribbean at the time, and Port Royal was their preferred destination. These had a welcome in the city if Morgan received the dues owed to him. As Morgan was no longer able to issue letters of marque to privateer captains, his brother-in-law, Robert Byndloss, directed them to the French governor of Tortuga to have a letter issued; Byndloss and Morgan received a commission for each one signed.

In July 1676 Carbery called for a hearing against Morgan in front of the Assembly of Jamaica, accusing him of collaborating with the French to attack Spanish interests. Morgan admitted he had met the French officials, but indicated that this was diplomatic relations, rather than anything duplicitous. In the summer of 1677 the Lords of Trade said they had yet to come to a decision on the matter and in early 1678 the king and the

On his arrival in Jamaica, the 12-man Assembly of Jamaica voted Morgan an annual salary of £600 "for his good services to the country"; the move angered Carbery, who did not get on with Morgan. Carbery later complained of his deputy that he was "every day more convinced of ... organ'simprudence and unfitness to have anything to do with civil government". Carbery also wrote to the Secretary of State to bemoan Morgan's "drinking and gaming at the taverns" of Port Royal.

Although Morgan had been ordered to eradicate piracy from Jamaican waters, he continued his friendly relations with many privateer captains, and invested in some of their ships. Zahedieh estimates that there were 1,200 privateers operating in the Caribbean at the time, and Port Royal was their preferred destination. These had a welcome in the city if Morgan received the dues owed to him. As Morgan was no longer able to issue letters of marque to privateer captains, his brother-in-law, Robert Byndloss, directed them to the French governor of Tortuga to have a letter issued; Byndloss and Morgan received a commission for each one signed.

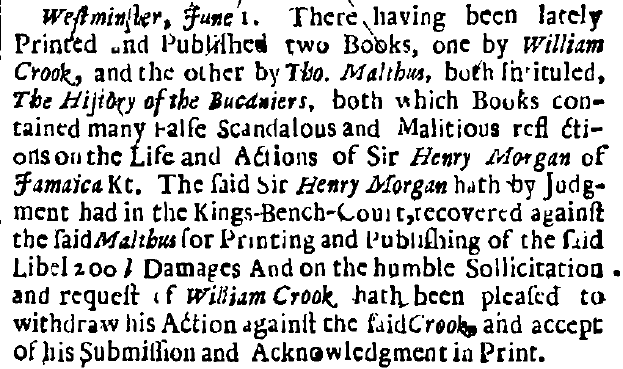

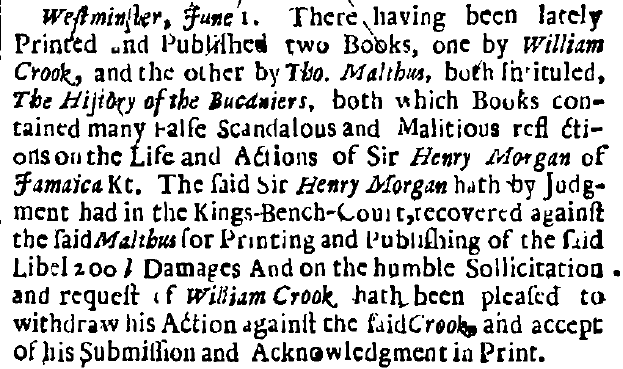

In July 1676 Carbery called for a hearing against Morgan in front of the Assembly of Jamaica, accusing him of collaborating with the French to attack Spanish interests. Morgan admitted he had met the French officials, but indicated that this was diplomatic relations, rather than anything duplicitous. In the summer of 1677 the Lords of Trade said they had yet to come to a decision on the matter and in early 1678 the king and the  In 1684 an account of Morgan's exploits was published by Exquemelin, in a Dutch volume entitled ''De Americaensche Zee-Roovers'' (trans: ''About the Buccaneers of America''). Morgan took steps to discredit the book and successfully brought a libel suit against the book's publishers William Crooke and Thomas Malthus. In his

In 1684 an account of Morgan's exploits was published by Exquemelin, in a Dutch volume entitled ''De Americaensche Zee-Roovers'' (trans: ''About the Buccaneers of America''). Morgan took steps to discredit the book and successfully brought a libel suit against the book's publishers William Crooke and Thomas Malthus. In his

Rogoziński observes that Morgan is probably the "best-known pirate" because of Exquemelin's book, although, Cordingly writes that Exquemelin bore a grudge over what he saw was Morgan's theft of the bounty from Panama. His experience explains "why he painted such a black picture of Morgan and portrayed him as a cruel and unscrupulous villain", which subsequently affected historians' view of Morgan. Allen observes that, partly because of Exquemelin, Morgan has not been well-served by historians. He cites the examples of the historians whose biographies were so flawed they wrote that Morgan had died in either London, prison or the Tower of London. These included Charles Leslie, ''A New History of Jamaica'' (1739), Alan Gardner, ''History of Jamaica'' (1873), Hubert Bancroft, ''History of Central America'' (1883) and

Rogoziński observes that Morgan is probably the "best-known pirate" because of Exquemelin's book, although, Cordingly writes that Exquemelin bore a grudge over what he saw was Morgan's theft of the bounty from Panama. His experience explains "why he painted such a black picture of Morgan and portrayed him as a cruel and unscrupulous villain", which subsequently affected historians' view of Morgan. Allen observes that, partly because of Exquemelin, Morgan has not been well-served by historians. He cites the examples of the historians whose biographies were so flawed they wrote that Morgan had died in either London, prison or the Tower of London. These included Charles Leslie, ''A New History of Jamaica'' (1739), Alan Gardner, ''History of Jamaica'' (1873), Hubert Bancroft, ''History of Central America'' (1883) and  Rogoziński observes that Morgan does not appear in later fictional works as much as other pirates because of his "ambiguous mixture of charismatic leadership and selfish treachery", although his name and persona have featured in literature, including

Rogoziński observes that Morgan does not appear in later fictional works as much as other pirates because of his "ambiguous mixture of charismatic leadership and selfish treachery", although his name and persona have featured in literature, including

"Henry Morgan"

Data Wales

"Henry Morgan"

100 Welsh Heroes {{DEFAULTSORT:Morgan, Henry 1630s births 1688 deaths Knights Bachelor Privateers People from Abergavenny People from Cardiff Welsh pirates Governors of Jamaica 17th-century pirates 17th-century Welsh people Planters of Jamaica 17th-century Jamaican people Jamaican people of British descent Port Royal Jamaican people of Welsh descent British slave traders

privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

, plantation owner, and, later, Lieutenant Governor of Jamaica

This is a list of viceroys in Jamaica from its initial occupation by Spain in 1509, to its independence from the United Kingdom in 1962. For a list of viceroys after independence, see Governor-General of Jamaica. For context, see History of Jamai ...

. From his base in Port Royal, Jamaica

Port Royal is a village located at the end of the Palisadoes, at the mouth of Kingston Harbour, in southeastern Jamaica. Founded in 1494 by the Spanish, it was once the largest city in the Caribbean, functioning as the centre of shipping and c ...

, he raided settlements and shipping on the Spanish Main

During the Spanish colonization of America, the Spanish Main was the collective term for the parts of the Spanish Empire that were on the mainland of the Americas and had coastlines on the Caribbean Sea or Gulf of Mexico. The term was used to di ...

, becoming wealthy as he did so. With the prize money

Prize money refers in particular to naval prize money, usually arising in naval warfare, but also in other circumstances. It was a monetary reward paid in accordance with the prize law of a belligerent state to the crew of a ship belonging to t ...

from the raids, he purchased three large sugar plantations

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. The ...

on the island.

Much of Morgan's early life is unknown. He was born in an area of Monmouthshire

Monmouthshire ( cy, Sir Fynwy) is a county in the south-east of Wales. The name derives from the historic county of the same name; the modern county covers the eastern three-fifths of the historic county. The largest town is Abergavenny, with ...

that is now part of the city of Cardiff

Cardiff (; cy, Caerdydd ) is the capital and largest city of Wales. It forms a principal area, officially known as the City and County of Cardiff ( cy, Dinas a Sir Caerdydd, links=no), and the city is the eleventh-largest in the United Kingd ...

. It is not known how he made his way to the West Indies, or how he began his career as a privateer. He was probably a member of a group of raiders led by Sir Christopher Myngs

Vice Admiral Sir Christopher Myngs (sometimes spelled ''Mings'', 1625–1666) was an English naval officer and privateer. He came of a Norfolk family and was a relative of Admiral Sir Cloudesley Shovell. Samuel Pepys' story of Myngs' humble bi ...

in the early 1660s during the Anglo-Spanish War. Morgan became a close friend of Sir Thomas Modyford

Colonel Sir Thomas Modyford, 1st Baronet (c. 1620 – 1 September 1679) was a planter of Barbados and Governor of Jamaica from 1664 to 1671.

Early life

Modyford was the son of a mayor of Exeter with family connections to the Duke of Albemar ...

, the Governor of Jamaica

This is a list of viceroys in Jamaica from its initial occupation by Spain in 1509, to its independence from the United Kingdom in 1962. For a list of viceroys after independence, see Governor-General of Jamaica. For context, see History of Jamai ...

. When diplomatic relations between the Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England (, ) was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from 12 July 927, when it emerged from various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain.

On 1 ...

and Spain worsened in 1667, Modyford gave Morgan a letter of marque, a licence to attack and seize Spanish vessels. Morgan subsequently conducted successful and highly lucrative raids on Puerto Principe

Port-au-Prince ( , ; ht, Pòtoprens ) is the capital and most populous city of Haiti. The city's population was estimated at 987,311 in 2015 with the metropolitan area estimated at a population of 2,618,894. The metropolitan area is defin ...

(now Camagüey in modern Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

) and Porto Bello (now Portobelo in modern Panama). In 1668, he sailed for Maracaibo

)

, motto = "''Muy noble y leal''"(English: "Very noble and loyal")

, anthem =

, image_map =

, mapsize =

, map_alt = ...

and Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

, both on Lake Maracaibo

Lake Maracaibo (Spanish: Lago de Maracaibo; Anu: Coquivacoa) is a lagoon in northwestern Venezuela, the largest lake in South America and one of the oldest on Earth, formed 36 million years ago in the Andes Mountains. The fault in the northern se ...

in modern-day Venezuela; he raided both cities and stripped them of their wealth before destroying a large Spanish squadron as he escaped. In 1671, Morgan attacked Panama City

Panama City ( es, Ciudad de Panamá, links=no; ), also known as Panama (or Panamá in Spanish), is the capital and largest city of Panama. It has an urban population of 880,691, with over 1.5 million in its metropolitan area. The city is locat ...

, landing on the Caribbean coast and traversing the isthmus

An isthmus (; ; ) is a narrow piece of land connecting two larger areas across an expanse of water by which they are otherwise separated. A tombolo is an isthmus that consists of a spit or bar, and a strait is the sea counterpart of an isthmu ...

before he attacked the city, which was on the Pacific coast. To appease the Spanish, with whom the English had signed a peace treaty, Morgan was arrested and summoned to London in 1672, but was treated as a hero by the general populace and the leading figures of government and royalty including Charles II.

Morgan was appointed a Knight Bachelor

The title of Knight Bachelor is the basic rank granted to a man who has been knighted by the monarch but not inducted as a member of one of the organised orders of chivalry; it is a part of the British honours system. Knights Bachelor are the ...

in November 1674 and returned to the Colony of Jamaica

The Crown Colony of Jamaica and Dependencies was a British colony from 1655, when it was captured by the English Protectorate from the Spanish Empire. Jamaica became a British colony from 1707 and a Crown colony in 1866. The Colony was pri ...

shortly afterward to serve as the territory's Lieutenant Governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a "second-in-comm ...

. He served on the Assembly of Jamaica until 1683 and on three occasions he acted as Governor of Jamaica in the absence of the current post-holder. A memoir published by Alexandre Exquemelin

Alexandre Olivier Exquemelin (also spelled ''Esquemeling'', ''Exquemeling'', or ''Oexmelin'') (c. 1645–1707) was a French, Dutch or Flemish writer best known as the author of one of the most important sourcebooks of 17th-century piracy, first p ...

, a former shipmate of Morgan's, accused him of widespread torture and other offences; Morgan won a libel

Defamation is the act of communicating to a third party false statements about a person, place or thing that results in damage to its reputation. It can be spoken (slander) or written (libel). It constitutes a tort or a crime. The legal defini ...

suit against the book's English publishers, but Exquemelin's portrayal has affected history's view of Morgan. His life was romanticised after his 1688 death and he became the inspiration for pirate

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

-themed works of fiction across a range of genres.

Early life

Born Harri Morgan around 1635 in Wales, either inLlanrumney

Llanrumney ( cy, Llanrhymni) is a suburb, community and electoral ward in east Cardiff, Wales.

Llanrumney was in Monmouthshire until it was incorporated into Cardiff in 1938.

History

The land where modern Llanrumney stands was left to Keynsham ...

or Pencarn (both in Monmouthshire

Monmouthshire ( cy, Sir Fynwy) is a county in the south-east of Wales. The name derives from the historic county of the same name; the modern county covers the eastern three-fifths of the historic county. The largest town is Abergavenny, with ...

, between Cardiff and Newport). The historian David Williams, writing in the Dictionary of Welsh Biography

The ''Dictionary of Welsh Biography'' (DWB) (also ''The Dictionary of Welsh Biography Down to 1940'' and ''The Dictionary of Welsh Biography, 1941 to 1970'') is a biographical dictionary of Welsh people who have made a significant contribution to ...

, observes that attempts to identify his parents and antecedents "have all proved unsatisfactory", although his will referred to distant relations. Several sources state Morgan's father was Robert Morgan, a farmer. Nuala Zahedieh, writing for the ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

'', states that details of Morgan's early life and career are uncertain, although in later life he stated that he had left school early and was "much more used to the pike

Pike, Pikes or The Pike may refer to:

Fish

* Blue pike or blue walleye, an extinct color morph of the yellow walleye ''Sander vitreus''

* Ctenoluciidae, the "pike characins", some species of which are commonly known as pikes

* ''Esox'', genus of ...

than the book".

It is unknown how Morgan made his way to the Caribbean. He may have travelled to the Caribbean as part of the army of Robert Venables

Robert Venables (ca. 1613–1687), was an English soldier from Cheshire, who fought for Parliament in the 1638 to 1651 Wars of the Three Kingdoms, and captured Jamaica in 1655.

When the Anglo-Spanish War began in 1654, he was made joint comm ...

, sent by Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

as part of the Caribbean expedition against the Spanish in the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

in 1654, or he may have served as an apprentice

Apprenticeship is a system for training a new generation of practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study (classroom work and reading). Apprenticeships can also enable practitioners to gain a ...

to a maker of cutlery for three years in exchange for the cost of his emigration. Richard Browne, who served as surgeon under Morgan in 1670 stated that Morgan had travelled either as a "private gentleman" soon after the 1655 capture of Jamaica by the English, or he may have been abducted in Bristol and transported to Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the Caribbean region of the Americas, and the most easterly of the Caribbean Islands. It occupies an area of and has a population of about 287,000 (2019 estimate). ...

, where he was sold as a servant. In the 17th century the Caribbean offered an opportunity for young men to become rich quickly, although significant investment was needed to obtain high returns from the sugar export economy. Other opportunities for financial gain were through trade or plunder of the Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

. Much of the plunder was from privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

ing, whereby individuals and ships were commissioned by government to attack the country's enemies.

Career as a privateer

It is probable that in the early 1660s Morgan was active with a group of privateers led by Sir

It is probable that in the early 1660s Morgan was active with a group of privateers led by Sir Christopher Myngs

Vice Admiral Sir Christopher Myngs (sometimes spelled ''Mings'', 1625–1666) was an English naval officer and privateer. He came of a Norfolk family and was a relative of Admiral Sir Cloudesley Shovell. Samuel Pepys' story of Myngs' humble bi ...

attacking Spanish cities and settlements in the Caribbean and Central America when England was at war with Spain. It is likely that in 1663 Morgan captained one of the ships in Myngs' fleet, and took part in the attack on Santiago de Cuba

Santiago de Cuba is the second-largest city in Cuba and the capital city of Santiago de Cuba Province. It lies in the southeastern area of the island, some southeast of the Cuban capital of Havana.

The municipality extends over , and contains t ...

and the Sack of Campeche on the Yucatán Peninsula

The Yucatán Peninsula (, also , ; es, Península de Yucatán ) is a large peninsula in southeastern Mexico and adjacent portions of Belize and Guatemala. The peninsula extends towards the northeast, separating the Gulf of Mexico to the north ...

.

Sir Thomas Modyford

Colonel Sir Thomas Modyford, 1st Baronet (c. 1620 – 1 September 1679) was a planter of Barbados and Governor of Jamaica from 1664 to 1671.

Early life

Modyford was the son of a mayor of Exeter with family connections to the Duke of Albemar ...

had been appointed the Governor of Jamaica

This is a list of viceroys in Jamaica from its initial occupation by Spain in 1509, to its independence from the United Kingdom in 1962. For a list of viceroys after independence, see Governor-General of Jamaica. For context, see History of Jamai ...

in February 1664 with instructions to limit the activities of the privateers; he made a proclamation against their activities on 11 June 1664, but economic practicalities led to his reversing the policy by the end of the month. About 1,500 privateers used Jamaica as a base for their activity and brought much revenue to the island. As the planting community of 5,000 was still new and developing, the revenue from the privateers was needed to avoid economic collapse. A privateer was granted a letter of marque which gave him a licence to attack and seize vessels, normally of a specified country, or with conditions attached. A portion of all spoils obtained by the privateers was given to the sovereign or the issuing ambassador.

In August 1665 Morgan, along with fellow captains John Morris and Jacob Fackman, returned to Port Royal

Port Royal is a village located at the end of the Palisadoes, at the mouth of Kingston Harbour, in southeastern Jamaica. Founded in 1494 by the Spanish, it was once the largest city in the Caribbean, functioning as the centre of shipping and co ...

with a large cargo of valuables. Modyford was impressed enough with the spoils to report back to the government that "Central America was the properest place for an attack on the Spanish Indies". Morgan's activities over the following two years are not documented, but in early 1666 he was married in Port Royal to his cousin, Mary Morgan, the daughter of Edward

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sa ...

, the island's Deputy Governor; the marriage gave Henry access to the upper levels of Jamaican society. The couple had no children.

Hostilities between the English and Dutch in 1664 led to a change in government policy: colonial governors were now authorised to issue letters of marque against the Dutch. Many of the privateers, including Morgan, did not take up the letters, although an expedition to conquer the Dutch island of Sint Eustatius

Sint Eustatius (, ), also known locally as Statia (), is an island in the Caribbean. It is a special municipality (officially " public body") of the Netherlands.

The island lies in the northern Leeward Islands portion of the West Indies, so ...

led to the death of Morgan's father-in-law, who was leading a 600-man force.

Sources differ about Morgan's activities in 1666. H. R. Allen, in his biography of Morgan, considers the privateer was the second-in-command to Captain Edward Mansvelt

Edward Mansvelt or Mansfield (fl. 1659-1666) was a 17th-century Dutch corsair and buccaneer who, at one time, was acknowledged as an informal chieftain of the "Brethren of the Coast". He was the first to organise large scale raids against Spanis ...

. Mansvelt had been issued a letter of marque for the invasion of Curaçao

Curaçao ( ; ; pap, Kòrsou, ), officially the Country of Curaçao ( nl, Land Curaçao; pap, Pais Kòrsou), is a Lesser Antilles island country in the southern Caribbean Sea and the Dutch Caribbean region, about north of the Venezuela coast ...

, although he did not attack Willemstad

Willemstad ( , ; ; en, William I of the Netherlands, William Town, italic=yes) is the capital city of Curaçao, an island in the southern Caribbean Sea that forms a Countries of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, constituent country of the Kingdo ...

, the main city, either after he decided that it was too well defended or that there was insufficient plunder. Alternatively, Jan Rogoziński and Stephan Talty, in their histories of Morgan and piracy, record that during the year, Morgan oversaw the Port Royal militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

and the defence of Jamaica; Fort Charles at Port Royal was partly constructed under his leadership. It was around this time that Morgan purchased his first plantation on Jamaica.

Attacks on Puerto Principe and Porto Bello (1667–1668)

In 1667 diplomatic relations between the kingdoms ofEngland

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

and Spain were worsening, and rumours began to circulate in Jamaica about a possible Spanish invasion. Modyford authorised privateers to take action against the Spanish, and issued a letter of marque to Morgan "to draw together the English privateers and take prisoners of the Spanish nation, whereby he might inform of the intention of that enemy to attack Jamaica, of which I have frequent and strong advice". He was given the rank of admiral and, in January 1668, assembled 10 ships and 500 men for the task; he was subsequently joined by 2 more ships and 200 men from Tortuga (now part of Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

).

Morgan's letter of marque gave him permission to attack Spanish ships at sea; there was no permission for attacks on land. Any plunder obtained from the attacks would be split between the government and the owners of the ships rented by the privateers. If the privateers stepped outside their official remit and raided a city, any resultant plunder would be retained by the privateers. Rogoziński observes that "attacks on cities were illegal piracy—but extremely profitable", although Zahedieh records that if Morgan was able to provide evidence of a potential Spanish attack, the attacks on cities were justifiable under the terms of his commission. Morgan's initial plan was to attack Havana, but, on discovering it was heavily defended, changed the target to Puerto Principe

Port-au-Prince ( , ; ht, Pòtoprens ) is the capital and most populous city of Haiti. The city's population was estimated at 987,311 in 2015 with the metropolitan area estimated at a population of 2,618,894. The metropolitan area is defin ...

(now Camagüey), a town inland. Morgan and his men took the town, but the treasure obtained was less than hoped for. According to Alexandre Exquemelin

Alexandre Olivier Exquemelin (also spelled ''Esquemeling'', ''Exquemeling'', or ''Oexmelin'') (c. 1645–1707) was a French, Dutch or Flemish writer best known as the author of one of the most important sourcebooks of 17th-century piracy, first p ...

, who sailed with Morgan, "It caused a general resentment and grief, to see such a small booty". When Morgan reported the taking of Puerto Principe to Modyford, he informed the governor that they had evidence that the Spanish were planning an attack on British territory: "we found seventy men had been pressed to go against Jamaica ... and considerable forces were expected from Vera Cruz and Campeachy ... and from Porto Bello and Cartagena to rendezvous at St Jago of Cuba antiago.

After the action, one of the English privateers quarrelled with one of his French shipmates and stabbed him in the back, killing him. Before a riot between the French and English sailors could begin, Morgan arrested the English sailor, and promised the French sailors that the man would be hanged on his return to Port Royal. Morgan kept his word and the sailor was hanged. After dividing the spoils of the conquest of Puerto Principe, Morgan announced a plan to attack Porto Bello (now in modern-day Panama). The city was the third largest and strongest on the

After the action, one of the English privateers quarrelled with one of his French shipmates and stabbed him in the back, killing him. Before a riot between the French and English sailors could begin, Morgan arrested the English sailor, and promised the French sailors that the man would be hanged on his return to Port Royal. Morgan kept his word and the sailor was hanged. After dividing the spoils of the conquest of Puerto Principe, Morgan announced a plan to attack Porto Bello (now in modern-day Panama). The city was the third largest and strongest on the Spanish Main

During the Spanish colonization of America, the Spanish Main was the collective term for the parts of the Spanish Empire that were on the mainland of the Americas and had coastlines on the Caribbean Sea or Gulf of Mexico. The term was used to di ...

, and on one of the main routes of trade between the Spanish territories and Spain. Because of the value of the goods passing through its port, Porto Bello was protected by two castles in the harbour and another in the town. The 200 French privateers, unhappy with the division of the treasure and the murder of their countryman, left Morgan's service and returned to Tortuga. Morgan and his ships briefly landed at Port Royal before leaving for Porto Bello.

On 11 July 1668 Morgan anchored short of Porto Bello and transferred his men to 23 canoes, which they paddled to within of the target. They landed and approached the first castle from the landward side, where they arrived half an hour before dawn. They took the three castles and the town quickly. The privateers lost 18 men, with a further 32 wounded; Zahedieh considers the action at Porto Bello displayed a "clever cunning and expert timing which marked ... organ'sbrilliance as a military commander".

Exquemelin wrote that in order to take the third castle, Morgan ordered the construction of ladders wide enough for three men to climb abreast; when they were completed he "commanded all the religious men and women whom he had taken prisoners to fix them against the walls of the castle ... these were forced, at the head of the companies to raise and apply them to the walls ... Thus many of the religious men and nuns were killed". Terry Breverton, in his biography of Morgan, writes that when a translation of Exquemelin's book was published in England, Morgan sued for libel

Defamation is the act of communicating to a third party false statements about a person, place or thing that results in damage to its reputation. It can be spoken (slander) or written (libel). It constitutes a tort or a crime. The legal defini ...

and won. The passage about the use of nuns and monks as a human shield

A human shield is a non-combatant (or a group of non-combatants) who either volunteers or is forced to shield a legitimate military target in order to deter the enemy from attacking it. The use of human shields as a resistance measure was popula ...

was retracted from subsequent publications in England.

Morgan and his men remained in Porto Bello for a month. He wrote to Don Agustín, the acting president of Panama, to demand a ransom for the city of 350,000

Morgan and his men remained in Porto Bello for a month. He wrote to Don Agustín, the acting president of Panama, to demand a ransom for the city of 350,000 peso

The peso is the monetary unit of several countries in the Americas, and the Philippines. Originating in the Spanish Empire, the word translates to "weight". In most countries the peso uses the Dollar sign, same sign, "$", as many currencies na ...

s. As they stripped the city of its wealth it is probable that torture was used on the residents to uncover hidden caches of money and jewels. Zahedieh records that there were no first-hand reports from witnesses that confirmed Exquemelin's claim of widespread rape and debauchery. After an attempt by Don Agustín to recapture the city by force – his army of 800 soldiers was repelled by the privateers – he negotiated a ransom of 100,000 pesos. Following the ransom and the plunder of the city, Morgan returned to Port Royal, with between £70,000 and £100,000 of money and valuables; Zahedieh reports that the figures were more than the agricultural output of Jamaica, and nearly half Barbados's sugar exports. Each privateer received £120 – equivalent to five or six times the average annual earnings of a sailor of the time. Morgan received a five per cent share for his work; Modyford received a ten per cent share, which was the price of Morgan's letter of marque. As Morgan had overstepped the limits of his commission, Modyford reported back to London that he had "reproved" him for his actions although, Zahedieh observes, in Britain "Morgan was widely viewed as a national hero and neither he nor Modyford were rebuked for their actions".

Raids on Maracaibo and Gibraltar (1668–1669)

Morgan did not stay long in Port Royal and in October 1668 sailed with ten ships and 800 men for

Morgan did not stay long in Port Royal and in October 1668 sailed with ten ships and 800 men for Île-à-Vache

Île-à-Vache, ( French, also expressed Île-à-Vaches, former Spanish name Isla Vaca; all translate to Cow Island) is a Caribbean island, one of Haiti's satellite islands. It lies in the Baie de Cayes about off the coast of the country's south ...

, a small island he used as a rendezvous point. His plan was to attack the Spanish settlement of Cartagena de Indias

Cartagena ( , also ), known since the colonial era as Cartagena de Indias (), is a city and one of the major ports on the northern coast of Colombia in the Caribbean Coast Region, bordering the Caribbean sea. Cartagena's past role as a link ...

, the richest and most important city on the Spanish Main. In December he was joined by a former Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and ...

, ''Oxford'', which had been sent to Port Royal to aid in any defence of Jamaica. Modyford sent the vessel to Morgan, who made it his flagship. On 2 January 1669 Morgan called a council of war for all his captains, which took place on ''Oxford''. A spark in the ship's powder magazine destroyed the ship and over 200 of its crew. Morgan and the captains seated on one side of the table were blown into the water and survived; the four captains on the other side of the table were all killed.

The loss of ''Oxford'' meant Morgan's flotilla was too small to attempt an attack on Cartagena. Instead he was persuaded by a French captain under his command to repeat the actions of the pirate François l'Olonnais

Jean-David Nau () (c. 1630 – c. 1669), better known as François l'Olonnais () (also l'Olonnois, Lolonois and Lolona), was a French pirate active in the Caribbean during the 1660s.

Early life

In his 1684 account ''The History of the Buccaneer ...

two years previously: an attack on Maracaibo

)

, motto = "''Muy noble y leal''"(English: "Very noble and loyal")

, anthem =

, image_map =

, mapsize =

, map_alt = ...

and Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

, both on Lake Maracaibo

Lake Maracaibo (Spanish: Lago de Maracaibo; Anu: Coquivacoa) is a lagoon in northwestern Venezuela, the largest lake in South America and one of the oldest on Earth, formed 36 million years ago in the Andes Mountains. The fault in the northern se ...

in modern-day Venezuela. The French captain knew the approaches to the lagoon, through a narrow and shallow channel. Since l'Olonnais and the French captain had visited Maracaibo, the Spanish had built the San Carlos de la Barra Fortress

San Carlos de la Barra Fortress is a 17th-century star fort protecting Lake Maracaibo in Venezuela.

The San Carlos de la Barra fort is one of a number of coastal fortifications which the Spanish built in Venezuela in colonial times. It is locate ...

, outside the city, on the approach. Talty states that the fortress was placed in an excellent position to defend the town, but that the Spanish had undermanned it, leaving only nine men to load and fire the fortress's 11 guns. Under covering cannon fire from the privateer's flagship, ''Lilly'', Morgan and his men landed on the beach and stormed the fortification; they found it empty when they eventually breached its defences. A search soon found that the Spanish had left a slow-burning fuse

Fuse or FUSE may refer to:

Devices

* Fuse (electrical), a device used in electrical systems to protect against excessive current

** Fuse (automotive), a class of fuses for vehicles

* Fuse (hydraulic), a device used in hydraulic systems to protect ...

leading to the fort's powder keg

A powder keg is a barrel of gunpowder. The powder keg was the primary method for storing and transporting large quantities of black powder until the 1870s and the adoption of the modern cased cartridge. The barrels had to be handled with care, si ...

s as a trap for the buccaneers, which Morgan extinguished. The fort's guns were spiked and then buried so they could not be used against the privateers when they returned from the rest of their mission.

Morgan arrived at Maracaibo to find the city largely deserted, its residents having been forewarned of his approach by the fortress's troops. He spent three weeks sacking the city. Privateers searched the surrounding jungle to find the escapees; they, and some of the remaining occupants, were tortured to find where money or treasure had been hidden. Satisfied he had stolen all he could, he sailed south across Lake Maracaibo, to Gibraltar. The town's occupants refused to surrender, and the fort fired enough of a barrage to ensure Morgan kept his distance. He anchored a short distance away and his men landed by canoe and assaulted the town from the landward approach. He met scant resistance, as many of the occupants had fled into the surrounding jungle. He spent five weeks in Gibraltar, and there was again evidence that torture was used to force residents to reveal hidden money and valuables.

Four days after he left Maracaibo, Morgan returned. He was told that a Spanish defence squadron, the Armada de Barlovento, was waiting for him at the narrow passage between the Caribbean and Lake Maracaibo, where the San Carlos de la Barra Fortress was sited. The forces, under the command of Don Alonso del Campo y Espinosa, had 126 cannon with which to attack Morgan, and had re-armed San Carlos de la Barra Fortress. The Spaniards had orders to end piracy in the Caribbean, and negotiations between Morgan and Espinosa continued for a week. The final offer put by the Spanish commander was for Morgan to leave all their spoils and slaves and to return to Jamaica unmolested, but no agreement was reached that would allow Morgan and his men to pass the fleet with their spoils but without attack. Morgan put the Spaniards' offers to his men, who voted instead to fight their way out. As they were heavily outgunned, one privateer suggested that a

Morgan arrived at Maracaibo to find the city largely deserted, its residents having been forewarned of his approach by the fortress's troops. He spent three weeks sacking the city. Privateers searched the surrounding jungle to find the escapees; they, and some of the remaining occupants, were tortured to find where money or treasure had been hidden. Satisfied he had stolen all he could, he sailed south across Lake Maracaibo, to Gibraltar. The town's occupants refused to surrender, and the fort fired enough of a barrage to ensure Morgan kept his distance. He anchored a short distance away and his men landed by canoe and assaulted the town from the landward approach. He met scant resistance, as many of the occupants had fled into the surrounding jungle. He spent five weeks in Gibraltar, and there was again evidence that torture was used to force residents to reveal hidden money and valuables.

Four days after he left Maracaibo, Morgan returned. He was told that a Spanish defence squadron, the Armada de Barlovento, was waiting for him at the narrow passage between the Caribbean and Lake Maracaibo, where the San Carlos de la Barra Fortress was sited. The forces, under the command of Don Alonso del Campo y Espinosa, had 126 cannon with which to attack Morgan, and had re-armed San Carlos de la Barra Fortress. The Spaniards had orders to end piracy in the Caribbean, and negotiations between Morgan and Espinosa continued for a week. The final offer put by the Spanish commander was for Morgan to leave all their spoils and slaves and to return to Jamaica unmolested, but no agreement was reached that would allow Morgan and his men to pass the fleet with their spoils but without attack. Morgan put the Spaniards' offers to his men, who voted instead to fight their way out. As they were heavily outgunned, one privateer suggested that a fire ship

A fire ship or fireship, used in the days of wooden rowed or sailing ships, was a ship filled with combustibles, or gunpowder deliberately set on fire and steered (or, when possible, allowed to drift) into an enemy fleet, in order to destroy sh ...

aimed at Espinosa's flagship, ''Magdalen'' would work.

To this end, a crew of 12 prepared a ship that had been seized in Gibraltar. They disguised vertical logs of wood with headwear, to make the Spaniards believe that the vessel was fully crewed. To make it look more heavily armed, additional portholes were cut in the hull and logs placed to resemble cannons. Barrels of powder were placed in the ship and grappling irons laced into the ships rigging, to catch the ropes and sails of ''Magdalen'' and ensure the vessels would become entangled.

On 1 May 1669 Morgan and his flotilla attacked the Spanish squadron. The fire ship plan worked, and ''Magdalen'' was shortly aflame; Espinosa abandoned his flagship and made his way to the fort, where he continued to direct events. The second-largest Spanish ship, ''Soledad'', tried to move away from the burning vessel, but a problem with the rigging meant they drifted aimlessly; privateers boarded the ship, fixed the rigging and claimed the craft as plunder. The third Spanish vessel was also sunk by the privateers. Morgan still needed to pass the San Carlos de la Barra Fortress, but was still out-gunned by the stronghold, which had the ability to destroy the privateer fleet if it tried to pass. The privateer decided to negotiate, and threatened to sack and burn Maracaibo if he was not allowed to pass. Although Espinosa refused to negotiate, the citizens of Maracaibo entered into talks with Morgan, and agreed to pay him 20,000 pesos and 500 head of cattle if he agreed to leave the city intact. During the course of the negotiations with the Maracaibos, Morgan had undertaken salvage operations on ''Magdalen'', and secured 15,000 pesos from the wreck. Before taking any action, Morgan tallied his takings and divided it equally between his ships, to ensure that it was not all lost if one ship was sunk; it totalled 250,000 pesos, and a huge quantity of merchandise and a number of local slaves.

Morgan observed that Espinosa had set his cannon for a landward attack from the privateers – as they had done previously. The privateers faked a landing of their forces. The fort and its battlements were stripped of men as the Spanish prepared for a night assault from the English forces. That evening, with Spanish forces deployed to repel a landing, Morgan's fleet raised anchor without unfurling their sails; the fleet moved on the tide, raising sail only when it had moved level with the fortress, and Morgan and his men made their way back to Port Royal unscathed. Zahedieh considers the escape showed Morgan's "characteristic cunning and audacity".

During his absence from Port Royal, a pro-Spanish faction had gained the ear of King Charles II, and English foreign policy had changed accordingly. Modyford admonished Morgan for his action, which had gone beyond his commission, and revoked the letters of marque; no official action was taken against any of the privateers. Morgan invested a share of his

On 1 May 1669 Morgan and his flotilla attacked the Spanish squadron. The fire ship plan worked, and ''Magdalen'' was shortly aflame; Espinosa abandoned his flagship and made his way to the fort, where he continued to direct events. The second-largest Spanish ship, ''Soledad'', tried to move away from the burning vessel, but a problem with the rigging meant they drifted aimlessly; privateers boarded the ship, fixed the rigging and claimed the craft as plunder. The third Spanish vessel was also sunk by the privateers. Morgan still needed to pass the San Carlos de la Barra Fortress, but was still out-gunned by the stronghold, which had the ability to destroy the privateer fleet if it tried to pass. The privateer decided to negotiate, and threatened to sack and burn Maracaibo if he was not allowed to pass. Although Espinosa refused to negotiate, the citizens of Maracaibo entered into talks with Morgan, and agreed to pay him 20,000 pesos and 500 head of cattle if he agreed to leave the city intact. During the course of the negotiations with the Maracaibos, Morgan had undertaken salvage operations on ''Magdalen'', and secured 15,000 pesos from the wreck. Before taking any action, Morgan tallied his takings and divided it equally between his ships, to ensure that it was not all lost if one ship was sunk; it totalled 250,000 pesos, and a huge quantity of merchandise and a number of local slaves.

Morgan observed that Espinosa had set his cannon for a landward attack from the privateers – as they had done previously. The privateers faked a landing of their forces. The fort and its battlements were stripped of men as the Spanish prepared for a night assault from the English forces. That evening, with Spanish forces deployed to repel a landing, Morgan's fleet raised anchor without unfurling their sails; the fleet moved on the tide, raising sail only when it had moved level with the fortress, and Morgan and his men made their way back to Port Royal unscathed. Zahedieh considers the escape showed Morgan's "characteristic cunning and audacity".

During his absence from Port Royal, a pro-Spanish faction had gained the ear of King Charles II, and English foreign policy had changed accordingly. Modyford admonished Morgan for his action, which had gone beyond his commission, and revoked the letters of marque; no official action was taken against any of the privateers. Morgan invested a share of his prize money

Prize money refers in particular to naval prize money, usually arising in naval warfare, but also in other circumstances. It was a monetary reward paid in accordance with the prize law of a belligerent state to the crew of a ship belonging to t ...

in an plantation – his second such investment.

Attack on Panama (1669–1672)

In 1669 Mariana, the Queen Regent of Spain, ordered attacks on English shipping in the Caribbean. The first action took place in March 1670 when Spanish privateers attacked English trade ships. In response Modyford commissioned Morgan "to do and perform all manner of exploits, which may tend to the preservation and quiet of this island". By December Morgan was sailing toward the Spanish Main with a fleet of over 30 English and French ships carrying a large number of privateers. Zahedieh observes that the army of privateers was the largest that had gathered in the Caribbean at the time, which was "a mark of Morgan's renown".

Morgan's first action was to take the connected islands of Old Providence and Santa Catalina in December 1670. From there his fleet sailed to

In 1669 Mariana, the Queen Regent of Spain, ordered attacks on English shipping in the Caribbean. The first action took place in March 1670 when Spanish privateers attacked English trade ships. In response Modyford commissioned Morgan "to do and perform all manner of exploits, which may tend to the preservation and quiet of this island". By December Morgan was sailing toward the Spanish Main with a fleet of over 30 English and French ships carrying a large number of privateers. Zahedieh observes that the army of privateers was the largest that had gathered in the Caribbean at the time, which was "a mark of Morgan's renown".

Morgan's first action was to take the connected islands of Old Providence and Santa Catalina in December 1670. From there his fleet sailed to Chagres

Chagres (), once the chief Atlantic port on the isthmus of Panama, is now an abandoned village at the historical site of Fort San Lorenzo ( es, Fuerte de San Lorenzo). The fort's ruins and the village site are located about west of Colón, on ...

, the port from which ships were loaded with goods to transport back to Spain. Morgan took the town and occupied Fort San Lorenzo

Chagres (), once the chief Atlantic port on the isthmus of Panama, is now an abandoned village at the historical site of Fort San Lorenzo ( es, Fuerte de San Lorenzo). The fort's ruins and the village site are located about west of Colón, Pana ...

, which he garrisoned to protect his line of retreat. On 9 January 1671, with his remaining men, he ascended the Chagres River and headed for Panama City

Panama City ( es, Ciudad de Panamá, links=no; ), also known as Panama (or Panamá in Spanish), is the capital and largest city of Panama. It has an urban population of 880,691, with over 1.5 million in its metropolitan area. The city is locat ...

, on the Pacific coast. Much of the journey was on foot, through dense rainforests and swamps. The governor of Panama had been forewarned of a potential attack, and had sent Spanish troops to attack Morgan and his men along the route. The privateers transferred to canoes to complete part of the journey, but were still able to beat off the ambushes with ease. After three days, with the river difficult to navigate in places, and with the jungle thinning out, Morgan landed his men and travelled overland across the remaining part of the isthmus

An isthmus (; ; ) is a narrow piece of land connecting two larger areas across an expanse of water by which they are otherwise separated. A tombolo is an isthmus that consists of a spit or bar, and a strait is the sea counterpart of an isthmu ...

.

The privateers, including Captain Robert Searle

Robert Searle (alias John Davis) was one of the earliest and most active of the England, English buccaneers on Jamaica.

Early life

Nothing, to date, is known of his early life. The famous buccaneer chronicler, Esquemeling, states that Searle ...

, arrived at Old Panama City on 27 January 1671; they camped overnight before attacking the following day. They were opposed by approximately 1,200 Spanish infantry and 400 cavalry; most were inexperienced. Morgan sent a 300-strong party of men down a ravine that led to the foot of a small hill on the Spanish right flank. As they disappeared from view, the Spanish front line thought the privateers were retreating, and the left wing broke rank and chased, followed by the remainder of the defending infantry. They were met with well-organised firing from Morgan's main force of troops. When the party came into view at the end of the ravine, they were charged by the Spanish cavalry, but organised fire destroyed the cavalry and the party attacked the flank of the main Spanish force. In an effort to disorganise Morgan's forces, the governor of Panama released two herds of oxen and bulls onto the battlefield; scared by the noise of the gunfire, they turned and stampeded over their keepers and some of the remaining Spanish troops. The battle was a rout: the Spanish lost between 400 and 500 men, against 15 privateers killed.

Panama's governor had sworn to burn down the city if his troops lost to the privateers, and he had placed barrels of gunpowder around the largely wooden buildings. These were detonated by the captain of artillery after Morgan's victory; the resultant fires lasted until the following day. Only a few stone buildings remained standing afterwards. Much of Panama's wealth was destroyed in the conflagration, although some had been removed by ships, before the privateers arrived. The privateers spent three weeks in Panama and plundered what they could from the ruins. Morgan's second-in-command, Captain Edward Collier, supervised the torture of some of the city's residents; Morgan's fleet surgeon, Richard Browne, later wrote that at Panama, Morgan "was noble enough to the vanquished enemy".

The value of treasure Morgan collected during his expedition is disputed. Talty writes that the figures range from 140,000 to 400,000 pesos, and that owing to the large army Morgan assembled, the prize-per-man was relatively low, causing discontent. There were accusations, particularly in Exquemelin's memoirs, that Morgan left with the majority of the plunder. He arrived back in Port Royal on 12 March to a positive welcome from the town's inhabitants. The following month he made his official report to the governing Council of Jamaica, and received their formal thanks and congratulations.

Panama's governor had sworn to burn down the city if his troops lost to the privateers, and he had placed barrels of gunpowder around the largely wooden buildings. These were detonated by the captain of artillery after Morgan's victory; the resultant fires lasted until the following day. Only a few stone buildings remained standing afterwards. Much of Panama's wealth was destroyed in the conflagration, although some had been removed by ships, before the privateers arrived. The privateers spent three weeks in Panama and plundered what they could from the ruins. Morgan's second-in-command, Captain Edward Collier, supervised the torture of some of the city's residents; Morgan's fleet surgeon, Richard Browne, later wrote that at Panama, Morgan "was noble enough to the vanquished enemy".

The value of treasure Morgan collected during his expedition is disputed. Talty writes that the figures range from 140,000 to 400,000 pesos, and that owing to the large army Morgan assembled, the prize-per-man was relatively low, causing discontent. There were accusations, particularly in Exquemelin's memoirs, that Morgan left with the majority of the plunder. He arrived back in Port Royal on 12 March to a positive welcome from the town's inhabitants. The following month he made his official report to the governing Council of Jamaica, and received their formal thanks and congratulations.

Arrest and release; knighthood and governorship (1672–1675)

During Morgan's absence from Jamaica, news reached the island that England and Spain had signed the Treaty of Madrid. The pact aimed to establish peace in the Caribbean between the two countries; it included an agreement to revoke all letters of marque and similar commissions. The historian

During Morgan's absence from Jamaica, news reached the island that England and Spain had signed the Treaty of Madrid. The pact aimed to establish peace in the Caribbean between the two countries; it included an agreement to revoke all letters of marque and similar commissions. The historian Violet Barbour

Violet Barbour (July 5, 1884 Cincinnati, Ohio - August 31, 1968) was an American historian.

Education

She graduated from Cornell University with a B.A., M.A., and Ph.D.

Career

Beginning in 1914, she taught at Vassar College as a professor of En ...

considers it probable that one of the Spanish conditions was the removal of Modyford from the Governorship. Modyford was arrested and sent to England by Sir Thomas Lynch, his recent replacement.

The destruction of Panama so soon after the signing of the treaty led to what Allen describes as "a crisis in international affairs" between England and Spain. The English government heard rumours from their ambassadors in Europe that the Spanish were considering war. In an attempt to appease them, Charles II and his Secretary of State, the Earl of Arlington

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. The title originates in the Old English word ''eorl'', meaning "a man of noble birth or rank". The word is cognate with the Scandinavian form '' jarl'', and meant "chieftain", particula ...

, ordered Morgan's arrest. In April 1672 the privateer admiral was returned to London where, Barbour writes, he was "handsomely lionized ... as the hero on whom Drake's mantle had fallen". Although some sources state that Morgan was also incarcerated in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separa ...

, Pope writes that Tower records make no mention of his presence there.

Morgan probably remained at liberty throughout his time in London, and the political mood changed in his favour. Arlington asked him to write a memorandum for the King on how to improve Jamaica's defences. Although there was no court case – Morgan was never charged with an offence – he gave informal evidence to the Lords of Trade and Plantations

The Lords of Trade and Plantations was a permanent administrative body formed by Charles II in 1675 to provide consistent advice to the Privy Council regarding the management of the growing number of English colonies. It replaced a series of temp ...

and proved he had no knowledge of the Treaty of Madrid prior to his attack on Panama. Unhappy with Lynch's conduct in Jamaica, the King and his advisers decided in January 1674 to replace him with John Vaughan, 3rd Earl of Carbery

John Vaughan, 3rd Earl of Carbery KB, PRS (baptised 8 July 1639 – 12 January 1713), styled Lord Vaughan from 1643 to 1686, was a Welsh nobleman and colonial administrator who served as the governor of Jamaica between 1675 and 1678.

Life

He ...

. Morgan would act as his deputy. Charles appointed Morgan a Knight Bachelor

The title of Knight Bachelor is the basic rank granted to a man who has been knighted by the monarch but not inducted as a member of one of the organised orders of chivalry; it is a part of the British honours system. Knights Bachelor are the ...

in November 1674, and two months later, Morgan and Carbery left for Jamaica. They were accompanied by Modyford, released from the Tower of London without charge and made the Chief Justice of Jamaica. They travelled on board the ''Jamaica Merchant'', which held cannon and shot meant to boost Port Royal's defences. The ship foundered on the rocks of Île-à-Vache and Morgan and the crew were temporarily stranded on the island until picked up by a passing merchant ship.

In Jamaican politics (1675–1688)

On his arrival in Jamaica, the 12-man Assembly of Jamaica voted Morgan an annual salary of £600 "for his good services to the country"; the move angered Carbery, who did not get on with Morgan. Carbery later complained of his deputy that he was "every day more convinced of ... organ'simprudence and unfitness to have anything to do with civil government". Carbery also wrote to the Secretary of State to bemoan Morgan's "drinking and gaming at the taverns" of Port Royal.

Although Morgan had been ordered to eradicate piracy from Jamaican waters, he continued his friendly relations with many privateer captains, and invested in some of their ships. Zahedieh estimates that there were 1,200 privateers operating in the Caribbean at the time, and Port Royal was their preferred destination. These had a welcome in the city if Morgan received the dues owed to him. As Morgan was no longer able to issue letters of marque to privateer captains, his brother-in-law, Robert Byndloss, directed them to the French governor of Tortuga to have a letter issued; Byndloss and Morgan received a commission for each one signed.

In July 1676 Carbery called for a hearing against Morgan in front of the Assembly of Jamaica, accusing him of collaborating with the French to attack Spanish interests. Morgan admitted he had met the French officials, but indicated that this was diplomatic relations, rather than anything duplicitous. In the summer of 1677 the Lords of Trade said they had yet to come to a decision on the matter and in early 1678 the king and the

On his arrival in Jamaica, the 12-man Assembly of Jamaica voted Morgan an annual salary of £600 "for his good services to the country"; the move angered Carbery, who did not get on with Morgan. Carbery later complained of his deputy that he was "every day more convinced of ... organ'simprudence and unfitness to have anything to do with civil government". Carbery also wrote to the Secretary of State to bemoan Morgan's "drinking and gaming at the taverns" of Port Royal.