Sir Francis Burnand on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

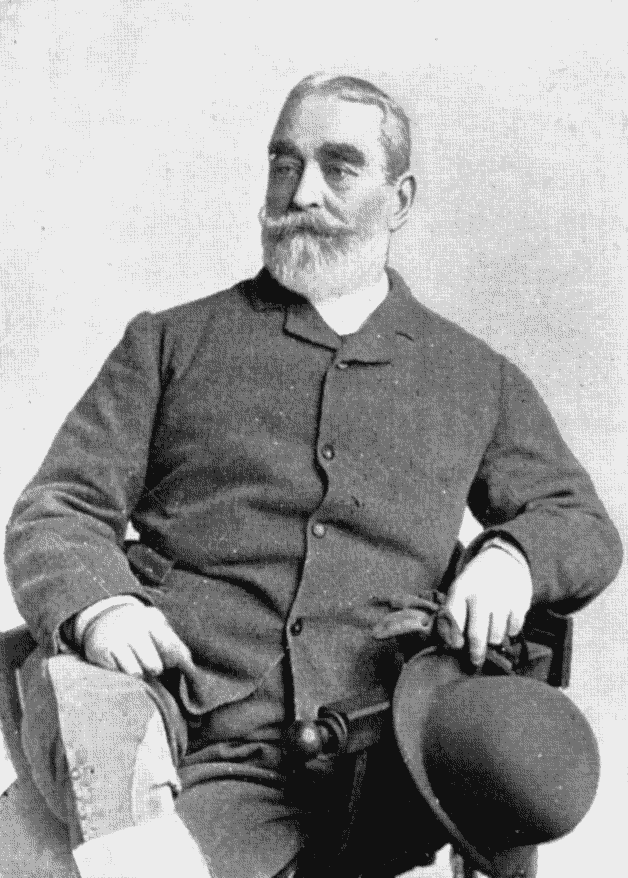

Sir Francis Cowley Burnand (29 November 1836 – 21 April 1917), usually known as F. C. Burnand, was an English comic writer and prolific playwright, best known today as the librettist of

Sir Francis Cowley Burnand (29 November 1836 – 21 April 1917), usually known as F. C. Burnand, was an English comic writer and prolific playwright, best known today as the librettist of

"Burnand, Sir Francis Cowley (1836–1917)"

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, September 2004, accessed 8 June 2014, Burnand senior, a stockbroker, was descended from an old

''Who Was Who'', online edition, Oxford University Press, 2014, accessed 7 July 2014 While at Eton, he submitted some illustrations to the comic weekly magazine, ''

"Burnand, Sir Francis Cowley (1836–1917)"

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' Archive, Oxford University Press, 1927, accessed 8 June 2014 He enrolled at

''Dido'' was followed by ''The Îles of St Tropez'' (1860), ''Fair Rosamond'' (1862) and ''The Deal Boatman'' (1863), among many others.Parker, p. 84 His most memorable early success was another musical burlesque, ''

''Dido'' was followed by ''The Îles of St Tropez'' (1860), ''Fair Rosamond'' (1862) and ''The Deal Boatman'' (1863), among many others.Parker, p. 84 His most memorable early success was another musical burlesque, ''

''Black-Eyed Susan; or, the Little Bill that Was Taken Up'', review in ''The Morning Post'', digitized by The British Library (2013), p. 51 the show ran for 400 nights at the

"Burnand, Sir Francis Cowley"

Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, accessed 8 July 2014 Its success encouraged its authors to write the two-act opera, ''

Burnand's wife Cecilia died in 1870 at age 28, leaving him with seven small children. In 1874 Burnand married her widowed sister, Rosina (d. 1924), who was also an actress. It was at that time illegal in England for a man to marry his dead wife's sister, although such marriages made outside British jurisdiction were recognised as valid; accordingly the wedding ceremony was performed in continental Europe. There were two sons and four daughters of this marriage.

Throughout the 1870s, Burnand maintained a prodigious output. For the stage he wrote 55 pieces, ranging from burlesques to

Burnand's wife Cecilia died in 1870 at age 28, leaving him with seven small children. In 1874 Burnand married her widowed sister, Rosina (d. 1924), who was also an actress. It was at that time illegal in England for a man to marry his dead wife's sister, although such marriages made outside British jurisdiction were recognised as valid; accordingly the wedding ceremony was performed in continental Europe. There were two sons and four daughters of this marriage.

Throughout the 1870s, Burnand maintained a prodigious output. For the stage he wrote 55 pieces, ranging from burlesques to

The third editor of ''Punch'', Tom Taylor, died in July 1880; the proprietors of the magazine appointed Burnand to succeed him. In Milne's view the magazine's reputation increased considerably under Burnand:

A later biographer, Jane Stedman, writes, "His predecessor, Tom Taylor, had allowed the paper to become heavy, but Burnand's rackety leadership brightened it." Burnand, who declared himself "hostile to no man's religion", banned ''Punchs previous anti-Catholicism, although he was unable to prevent some antisemitic jokes.

One of Burnand's biggest successes, both in ''Punch'' and on stage, was satire of the

The third editor of ''Punch'', Tom Taylor, died in July 1880; the proprietors of the magazine appointed Burnand to succeed him. In Milne's view the magazine's reputation increased considerably under Burnand:

A later biographer, Jane Stedman, writes, "His predecessor, Tom Taylor, had allowed the paper to become heavy, but Burnand's rackety leadership brightened it." Burnand, who declared himself "hostile to no man's religion", banned ''Punchs previous anti-Catholicism, although he was unable to prevent some antisemitic jokes.

One of Burnand's biggest successes, both in ''Punch'' and on stage, was satire of the

In 1890, Burnand wrote ''Captain Therèse,'' followed later that year by a very successful English version of Audran's operetta, ''

In 1890, Burnand wrote ''Captain Therèse,'' followed later that year by a very successful English version of Audran's operetta, ''""Burns & Oates"

''The Universe'', 8 January 1909, accessed 17 July 2017

Burnand lived for much of his life in

Profile of Burnand

F. C. Burnand letters and memoranda, 1873–1907

held by the Billy Rose Theatre Division,

Sir Francis Cowley Burnand (29 November 1836 – 21 April 1917), usually known as F. C. Burnand, was an English comic writer and prolific playwright, best known today as the librettist of

Sir Francis Cowley Burnand (29 November 1836 – 21 April 1917), usually known as F. C. Burnand, was an English comic writer and prolific playwright, best known today as the librettist of Arthur Sullivan

Sir Arthur Seymour Sullivan (13 May 1842 – 22 November 1900) was an English composer. He is best known for 14 comic opera, operatic Gilbert and Sullivan, collaborations with the dramatist W. S. Gilbert, including ''H.M.S. Pinaf ...

's opera ''Cox and Box

''Cox and Box; or, The Long-Lost Brothers'', is a one-act comic opera with a libretto by F. C. Burnand and music by Arthur Sullivan, based on the 1847 farce '' Box and Cox'' by John Maddison Morton. It was Sullivan's first successful comic o ...

''.

The son of a prosperous family, he was educated at Eton Eton most commonly refers to Eton College, a public school in Eton, Berkshire, England.

Eton may also refer to:

Places

*Eton, Berkshire, a town in Berkshire, England

* Eton, Georgia, a town in the United States

* Éton, a commune in the Meuse dep ...

and Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

and was expected to follow a conventional career in the law or in the church, but he concluded that his vocation was the theatre. From his schooldays he had written comic plays, and from 1860 until the end of the 19th century, he produced a series of more than 200 Victorian burlesque

Victorian burlesque, sometimes known as travesty or extravaganza, is a genre of theatrical entertainment that was popular in Victorian era, Victorian England and in the New York theatre of the mid-19th century. It is a form of parody music, parod ...

s, farces

Farce is a comedy that seeks to entertain an audience through situations that are highly exaggerated, extravagant, ridiculous, absurd, and improbable. Farce is also characterized by heavy use of physical humor; the use of deliberate absurdity or ...

, pantomime

Pantomime (; informally panto) is a type of musical comedy stage production designed for family entertainment. It was developed in England and is performed throughout the United Kingdom, Ireland and (to a lesser extent) in other English-speaking ...

s and other stage works. His early successes included the burlesques ''Ixion'', ''or the Man at the Wheel'' (1863) and ''The Latest Edition of Black-Eyed Susan''; ''or'', ''the Little Bill that Was Taken Up'' (1866). Also in 1866, he adapted the popular farce '' Box and Cox'' as a comic opera, ''Cox and Box'', with music by Sullivan. The piece became a popular favourite and was later frequently used by the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company

The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company is a professional British light opera company that, from the 1870s until 1982, staged Gilbert and Sullivan's Savoy operas nearly year-round in the UK and sometimes toured in Europe, North America and elsewhere. Th ...

as a curtain raiser; it remains regularly performed today.

By the 1870s, Burnand was generating a prodigious output of plays as well as comic pieces and illustrations for the humour magazine ''Punch

Punch commonly refers to:

* Punch (combat), a strike made using the hand closed into a fist

* Punch (drink), a wide assortment of drinks, non-alcoholic or alcoholic, generally containing fruit or fruit juice

Punch may also refer to:

Places

* Pun ...

''. Among his 55-stage works during the decade was another frequently revived hit, '' Betsy'' (1879). For ''Punch'', among other things, he wrote the popular column "Happy Thoughts", in which the narrator recorded the difficulties and distractions of everyday life. Also admired were his burlesques of other writers' works. Burnand was a contributor to ''Punch'' for 45 years and its editor from 1880 until 1906 and is credited with adding much to the popularity and prosperity of the magazine. His editorship of the original publication of ''The Diary of a Nobody

''The Diary of a Nobody'' is an English comic novel written by the brothers George and Weedon Grossmith, with illustrations by the latter. It originated as an intermittent serial in ''Punch'' magazine in 1888–89 and first appeared in book for ...

'' by the brothers George

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Washington, First President of the United States

* George W. Bush, 43rd Presiden ...

and Weedon Grossmith

Walter Weedon Grossmith (9 June 1854 – 14 June 1919), better known as Weedon Grossmith, was an English writer, painter, actor, and playwright best known as co-author of ''The Diary of a Nobody'' (1892) with his brother, music hall comedian ...

was a high point of his tenure in 1888–89. Many of his articles were collected and published in book form. His stage successes in the 1890s included his English-language versions of two Edmond Audran

Achille Edmond Audran (12 April 184017 August 1901) was a French composer best known for several internationally successful comic operas and operettas.

After beginning his career in Marseille as an organist, Audran composed religious music and ...

operettas, titled ''La Cigale

La Cigale (; English: ''The Cicada'') is a theatre located at 120, boulevard de Rochechouart near Place Pigalle, in the 18th arrondissement of Paris. The theatre is part of a complex connected to the Le Trabendo concert venue and the Boule Noir ...

'' and ''Miss Decima'' (both in 1891). His last works included collaborations on pantomimes of ''Cinderella

"Cinderella",; french: link=no, Cendrillon; german: link=no, Aschenputtel) or "The Little Glass Slipper", is a folk tale with thousands of variants throughout the world.Dundes, Alan. Cinderella, a Casebook. Madison, Wis: University of Wisconsi ...

'' (1905) and ''Aladdin'' (1909).

Known generally for his genial wit and good humour, Burnand was nevertheless intensely envious of his contemporary W. S. Gilbert

Sir William Schwenck Gilbert (18 November 1836 – 29 May 1911) was an English dramatist, librettist, poet and illustrator best known for his collaboration with composer Arthur Sullivan, which produced fourteen comic operas. The most f ...

but was unable to emulate his rival's success as a comic opera librettist. In other forms of theatre Burnand was outstandingly successful, with his works receiving London runs of up to 550 performances and extensive tours in the British provinces and the US. He published several humorous books and memoirs and was knighted in 1902 for his work on ''Punch''.

Life and career

Early years

Burnand was born in central London, the only child of Francis Burnand and his first wife Emma, ''née'' Cowley, who died when her son was eight days old.Stedman, Jane W"Burnand, Sir Francis Cowley (1836–1917)"

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, September 2004, accessed 8 June 2014, Burnand senior, a stockbroker, was descended from an old

Savoy

Savoy (; frp, Savouè ; french: Savoie ) is a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps.

Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphiné in the south.

Savo ...

ard family, prominent in the silk trade; his wife was a descendant of the poet and dramatist Hannah Cowley.

Burnand was educated at Eton Eton most commonly refers to Eton College, a public school in Eton, Berkshire, England.

Eton may also refer to:

Places

*Eton, Berkshire, a town in Berkshire, England

* Eton, Georgia, a town in the United States

* Éton, a commune in the Meuse dep ...

, where, aged fifteen, he wrote a farce

Farce is a comedy that seeks to entertain an audience through situations that are highly exaggerated, extravagant, ridiculous, absurd, and improbable. Farce is also characterized by heavy use of physical humor; the use of deliberate absurdity o ...

, ''Guy Fawkes Day'', played at Cookesley's house, and subsequently at the Theatre Royal, Worthing

Worthing () is a seaside town in West Sussex, England, at the foot of the South Downs, west of Brighton, and east of Chichester. With a population of 111,400 and an area of , the borough is the second largest component of the Brighton and Hov ...

."Burnand, Sir Francis Cowley"''Who Was Who'', online edition, Oxford University Press, 2014, accessed 7 July 2014 While at Eton, he submitted some illustrations to the comic weekly magazine, ''

Punch

Punch commonly refers to:

* Punch (combat), a strike made using the hand closed into a fist

* Punch (drink), a wide assortment of drinks, non-alcoholic or alcoholic, generally containing fruit or fruit juice

Punch may also refer to:

Places

* Pun ...

'', one or two of which were published. In 1854 he went to Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by Henry VIII, King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any college at either Cambridge ...

, where as an undergraduate he sought the approval of the Vice-Chancellor

A chancellor is a leader of a college or university, usually either the executive or ceremonial head of the university or of a university campus within a university system.

In most Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth and former Commonwealth n ...

, Edwin Guest

Edwin Guest LL.D. FRS (10 September 180023 November 1880) was an English antiquary.

He was educated at King Edward's School, Birmingham, and at Caius College, Cambridge, where he graduated as eleventh wrangler, subsequently becoming a fellow ...

, of the establishment of a Cambridge University Amateur Dramatic Club

Founded in 1855, the Amateur Dramatic Club (or ADC) is the oldest university dramatic society in England – and the largest dramatic society in Cambridge.

The club stages a diverse range of productions every term, many of them at the fully equi ...

, with a performance of '' Box and Cox''. Guest and his colleagues refused their consent, but Burnand went ahead without it. The members of the club performed a triple bill under stage names to avoid retribution from the university. The club prospered (and continues to the present day); Burnand acted and wrote plays under the name Tom Pierce.

Burnand graduated in 1858. His family had expected that he would study for the bar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

* Chocolate bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a layer of cloud

* Bar (u ...

, but the Burnands held the right to appoint the incumbent

The incumbent is the current holder of an official, office or position, usually in relation to an election. In an election for president, the incumbent is the person holding or acting in the office of president before the election, whether seek ...

of a Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

parish that became vacant, and it was agreed that he should train for the priesthood.Milne, A. A"Burnand, Sir Francis Cowley (1836–1917)"

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' Archive, Oxford University Press, 1927, accessed 8 June 2014 He enrolled at

Cuddesdon

Cuddesdon is a mainly rural village in South Oxfordshire centred ESE of Oxford. It has the largest Church of England clergy training centre, Ripon College Cuddesdon. Residents number approximately 430 in Cuddesdon's nucleated village centre a ...

theological college, where his studies of divinity led him to leave the Anglican church and become a Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

. This caused a breach between Burnand and his father, but the estrangement did not last long. To the disappointment of Cardinal Manning, leader of the English Catholics, Burnand announced that his vocation was not for the church but for the theatre. Father and son were reconciled, and Burnand returned to his original plan of reading for the bar at Lincoln's Inn

The Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn is one of the four Inns of Court in London to which barristers of England and Wales belong and where they are called to the Bar. (The other three are Middle Temple, Inner Temple and Gray's Inn.) Lincoln ...

."Death of Sir Francis Burnand", ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'', 23 April 1917, p. 11

1860s: start of writing career

In February 1860 Burnand had his first piece performed in the West End, ''Dido the Celebrated Widow'', a musical burlesque of ''Dido and Aeneas

''Dido and Aeneas'' (Z. 626) is an opera in a prologue and three acts, written by the English Baroque composer Henry Purcell with a libretto by Nahum Tate. The dates of the composition and first performance of the opera are uncertain. It was co ...

'', played at the St James's Theatre

The St James's Theatre was in King Street, St James's, London. It opened in 1835 and was demolished in 1957. The theatre was conceived by and built for a popular singer, John Braham; it lost money and after three seasons he retired. A succ ...

.Nicoll, p. 288 The following month he married an actress, Cecilia Victoria Ranoe (1841–1870), daughter of James Ranoe, a clerk; the couple had five sons and two daughters. He was called to the bar

The call to the bar is a legal term of art in most common law jurisdictions where persons must be qualified to be allowed to argue in court on behalf of another party and are then said to have been "called to the bar" or to have received "call to ...

in 1862, and practised for a short time, but his main interest was in writing. In the early 1860s he wrote several farces in partnership with Montagu Williams

Montagu Stephen Williams Q.C. (30 September 1835 – 23 December 1892) was an English teacher, British Army officer, actor, playwright, barrister and magistrate.

Williams was educated at Eton College and started his career as a schoolmaster at ...

, and edited the short-lived journal ''The Glow-Worm''. He then joined the staff of ''Fun

Fun is defined by the ''Oxford English Dictionary'' as "Light-hearted pleasure, enjoyment, or amusement; boisterous joviality or merrymaking; entertainment".

Etymology and usage

The word ''fun'' is associated with sports, entertaining medi ...

'', edited by H. J. Byron

Henry James Byron (8 January 1835 – 11 April 1884) was a prolific English dramatist, as well as an editor, journalist, director, theatre manager, novelist and actor.

After an abortive start at a medical career, Byron struggled as a provincial ...

. He parted company with Byron when the magazine rejected his proposed 1863 literary burlesque of a Reynolds Reynolds may refer to:

Places Australia

*Hundred of Reynolds, a cadastral unit in South Australia

*Hundred of Reynolds (Northern Territory), a cadastral unit in the Northern Territory of Australia

United States

* Reynolds, Mendocino County, Calif ...

serial, entitled ''Mokeanna, or the White Witness''. He showed his manuscript to Mark Lemon

Mark Lemon (30 November 1809, in London – 23 May 1870, in Crawley) was the founding editor of both ''Punch'' and '' The Field''. He was also a writer of plays and verses.

Biography

Lemon was born in Marylebone, Westminster, Middlesex, ...

, editor of ''Punch'', who accepted it for publication; Burnand remained a ''Punch'' writer for the rest of his career.

''Dido'' was followed by ''The Îles of St Tropez'' (1860), ''Fair Rosamond'' (1862) and ''The Deal Boatman'' (1863), among many others.Parker, p. 84 His most memorable early success was another musical burlesque, ''

''Dido'' was followed by ''The Îles of St Tropez'' (1860), ''Fair Rosamond'' (1862) and ''The Deal Boatman'' (1863), among many others.Parker, p. 84 His most memorable early success was another musical burlesque, ''Ixion

In Greek mythology, Ixion ( ; el, Ἰξίων, ''gen''.: Ἰξίονος means 'strong native') was king of the Lapiths, the most ancient tribe of Thessaly.

Family

Ixion was the son of Ares, or Leonteus, or Antion and Perimele, or the not ...

, or the Man at the Wheel'' (1863), starring Lydia Thompson

Lydia Thompson (born Eliza Thompson; 19 February 1838 – 17 November 1908), was an English dancer, comedian, actor and theatrical producer.

From 1852, as a teenager, she danced and performed in pantomimes, in the UK and then in Europe and soo ...

in the title role, which found audiences on both sides of the Atlantic. By this time Burnand was a skilled negotiator with theatre managements, and he was among the first authors to insist on profit-sharing instead of fixed royalties. For ''Ixion'' this brought him a total of around £3,000. Other notable early works included an opéra bouffe

Opéra bouffe (, plural: ''opéras bouffes'') is a genre of late 19th-century French operetta, closely associated with Jacques Offenbach, who produced many of them at the Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens, inspiring the genre's name.

Opéras bouf ...

, ''Windsor Castle'' (1865), with music by Frank Musgrave, and more pun-filled burlesques, including ''Helen

Helen may refer to:

People

* Helen of Troy, in Greek mythology, the most beautiful woman in the world

* Helen (actress) (born 1938), Indian actress

* Helen (given name), a given name (including a list of people with the name)

Places

* Helen, ...

, or, Taken from the Greek'', and ''Guy Fawkes

Guy Fawkes (; 13 April 1570 – 31 January 1606), also known as Guido Fawkes while fighting for the Spanish, was a member of a group of provincial English Catholics involved in the failed Gunpowder Plot of 1605. He was born and educated ...

, or The Ugly Mug and the Couple of Spoons'', both in 1866. Later in 1866 Burnand had a huge success with the burlesque ''The Latest Edition of Black-Eyed Susan; or, the Little Bill that Was Taken Up'', parodying the three-act melodrama by Douglas Jerrold

Douglas William Jerrold (London 3 January 18038 June 1857 London) was an English dramatist and writer.

Biography

Jerrold's father, Samuel Jerrold, was an actor and lessee of the little theatre of Wilsby near Cranbrook in Kent. In 1807 Dougla ...

, ''Black-Eyed Susan

''Black-Eyed Susan; or, All in the Downs'' is a comic play in three acts by Douglas Jerrold. The story concerns a heroic sailor, William, who has been away from England for three years fighting in the Napoleonic Wars. Meanwhile, his wife, Susa ...

'';"''The Morning Post''"''Black-Eyed Susan; or, the Little Bill that Was Taken Up'', review in ''The Morning Post'', digitized by The British Library (2013), p. 51 the show ran for 400 nights at the

Royalty Theatre

The Royalty Theatre was a small London theatre situated at 73 Dean Street, Soho. Established by the actress Frances Maria Kelly in 1840, it opened as Miss Kelly's Theatre and Dramatic School and finally closed to the public in 1938.

, was played for years provincially and in the US, and was twice revived in London.

In 1866, Burnand adapted the popular farce ''Box and Cox'' as a comic opera

Comic opera, sometimes known as light opera, is a sung dramatic work of a light or comic nature, usually with a happy ending and often including spoken dialogue.

Forms of comic opera first developed in late 17th-century Italy. By the 1730s, a ne ...

, ''Cox and Box

''Cox and Box; or, The Long-Lost Brothers'', is a one-act comic opera with a libretto by F. C. Burnand and music by Arthur Sullivan, based on the 1847 farce '' Box and Cox'' by John Maddison Morton. It was Sullivan's first successful comic o ...

'', with music by the young composer Arthur Sullivan

Sir Arthur Seymour Sullivan (13 May 1842 – 22 November 1900) was an English composer. He is best known for 14 comic opera, operatic Gilbert and Sullivan, collaborations with the dramatist W. S. Gilbert, including ''H.M.S. Pinaf ...

. The piece was written for a private performance but was repeated and given its first public performance at the Adelphi Theatre

The Adelphi Theatre is a West End theatre, located on the Strand in the City of Westminster, central London. The present building is the fourth on the site. The theatre has specialised in comedy and musical theatre, and today it is a receiv ...

in 1867. The reviewer for ''Fun'' was W. S. Gilbert

Sir William Schwenck Gilbert (18 November 1836 – 29 May 1911) was an English dramatist, librettist, poet and illustrator best known for his collaboration with composer Arthur Sullivan, which produced fourteen comic operas. The most f ...

, who wrote

''Cox and Box'' became a popular favourite and was frequently revived. It was the only work not by Gilbert in the regular repertory of the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company

The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company is a professional British light opera company that, from the 1870s until 1982, staged Gilbert and Sullivan's Savoy operas nearly year-round in the UK and sometimes toured in Europe, North America and elsewhere. Th ...

during the 20th century and is the only work of Burnand's still frequently staged.Fredric Woodbridge Wilson"Burnand, Sir Francis Cowley"

Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, accessed 8 July 2014 Its success encouraged its authors to write the two-act opera, ''

The Contrabandista

''The Contrabandista'', ''or The Law of the Ladrones'', is a two-act comic opera by Arthur Sullivan and F. C. Burnand. It premiered at St. George's Hall, in London, on 18 December 1867 under the management of Thomas German Reed, for a run of 72 ...

'' (1867), revised and expanded as ''The Chieftain

''The Chieftain'' is a two-act comic opera by Arthur Sullivan and F. C. Burnand based on their 1867 opera, ''The Contrabandista''. It consists of substantially the same first act as the 1867 work with a completely new second act. It premiered at ...

'' (1894), but it did not achieve much popularity in either version.

More burlesques followed in 1868, including ''Fowl Play, or, A Story of Chicken Hazard'' and ''The Rise and Fall of Richard III, or, A New Front to an Old Dicky''. In 1869, Burnand wrote ''The Turn of the Tide'', which was a success at the Queen's Theatre, and six other stage works during the course of the year.

1870s: prolific author

Burnand's wife Cecilia died in 1870 at age 28, leaving him with seven small children. In 1874 Burnand married her widowed sister, Rosina (d. 1924), who was also an actress. It was at that time illegal in England for a man to marry his dead wife's sister, although such marriages made outside British jurisdiction were recognised as valid; accordingly the wedding ceremony was performed in continental Europe. There were two sons and four daughters of this marriage.

Throughout the 1870s, Burnand maintained a prodigious output. For the stage he wrote 55 pieces, ranging from burlesques to

Burnand's wife Cecilia died in 1870 at age 28, leaving him with seven small children. In 1874 Burnand married her widowed sister, Rosina (d. 1924), who was also an actress. It was at that time illegal in England for a man to marry his dead wife's sister, although such marriages made outside British jurisdiction were recognised as valid; accordingly the wedding ceremony was performed in continental Europe. There were two sons and four daughters of this marriage.

Throughout the 1870s, Burnand maintained a prodigious output. For the stage he wrote 55 pieces, ranging from burlesques to pantomime

Pantomime (; informally panto) is a type of musical comedy stage production designed for family entertainment. It was developed in England and is performed throughout the United Kingdom, Ireland and (to a lesser extent) in other English-speaking ...

s, farces and extravaganza

An extravaganza is a literary or musical work (often musical theatre) usually containing elements of burlesque, pantomime, music hall and parody in a spectacular production and characterized by freedom of style and structure. It sometimes also ha ...

s.Nicoll, pp. 289–291 He was the sole author of most of them, but worked on a few with Thomas German Reed

Thomas German Reed (27 June 1817 – 21 March 1888), known after 1844 as simply German Reed was an English composer, musical director, actor, singer and theatrical manager of the Victorian era. He was best known for creating the German Ree ...

, J. L. Molloy, Henry Pottinger Stephens

Henry Pottinger Stephens, also known as Henry Beauchamp (1851 – 11 February 1903), was an English dramatist and journalist.

After beginning his career writing for newspapers, Stephens began writing Victorian burlesques in the 1870s in coll ...

and even with H. J. Byron. His stage pieces of the 1870s included ''Poll and Partner Joe'' (1871), ''Penelope Anne'' (1871; a sequel to ''Cox and Box''), ''The Miller and His Man'' (1873; "a Christmas drawing room extravaganza" with songs by Sullivan), ''Artful Cards'' (1877), ''Proof'' (1878), ''Dora and Diplunacy'' (1878, a burlesque of Clement Scott

Clement William Scott (6 October 1841 – 25 June 1904) was an influential English theatre critic for ''The Daily Telegraph'' and other journals, and a playwright, lyricist, translator and travel writer, in the final decades of the 19th century ...

's ''Diplomacy

Diplomacy comprises spoken or written communication by representatives of states (such as leaders and diplomats) intended to influence events in the international system.Ronald Peter Barston, ''Modern diplomacy'', Pearson Education, 2006, p. 1 ...

'', an adaptation of Sardou's ''Dora''), ''The Forty Thieves

''The Forty Thieves'' is a "Pantomime Burlesque" written by Robert Reece, W. S. Gilbert, F. C. Burnand and Henry J. Byron, created in 1878 as a charity benefit, produced by the Beefsteak Club of London. The Beefsteak Club still meets in Irving ...

'' (1878; a charity collaboration among four playwrights, including Byron and Gilbert), ''Our Club'' (1878) and another frequently revived hit, '' Betsy'' (1879). He provided a burlesque of ''Robbing Roy'' to the Gaiety Theatre in 1879. Burnand's prolific writing came at some cost in quality. A biographer wrote that he "was a facile and slapdash writer. False rhymes and awkward rhythms occur frequently in his verse, and his favourite devices included puns, topical references and slang."

Burnand also translated or adapted for the London stage several French operettas by Offenbach, Edmond Audran

Achille Edmond Audran (12 April 184017 August 1901) was a French composer best known for several internationally successful comic operas and operettas.

After beginning his career in Marseille as an organist, Audran composed religious music and ...

, Charles Lecocq

Alexandre Charles Lecocq (3 June 183224 October 1918) was a French composer, known for his opérettes and opéra comique, opéras comiques. He became the most prominent successor to Jacques Offenbach in this sphere, and enjoyed considerable succ ...

and Robert Planquette

Jean Robert Planquette (31 July 1848 – 28 January 1903) was a French composer of songs and operettas.

Several of Planquette's operettas were extraordinarily successful in Britain, especially ''Les cloches de Corneville'' (1878), the length of ...

. At the same time as his busy theatrical career, he was a member of the staff of ''Punch'' under Lemon and his successors, Shirley Brooks

Charles William Shirley Brooks (29 April 1816 – 23 February 1874) was an English journalist and novelist. Born in London, he began his career in a solicitor's office. Shortly afterwards he took to writing, and contributed to various per ...

and Tom Taylor

Tom Taylor (19 October 1817 – 12 July 1880) was an English dramatist, critic, biographer, public servant, and editor of ''Punch'' magazine. Taylor had a brief academic career, holding the professorship of English literature and language a ...

, writing a regular stream of genial articles. His best-known work for the magazine was the column "Happy Thoughts", in which the narrator recorded the difficulties and distractions of everyday life. A. A. Milne

Alan Alexander Milne (; 18 January 1882 – 31 January 1956) was an English writer best known for his books about the teddy bear Winnie-the-Pooh, as well as for children's poetry. Milne was primarily a playwright before the huge success of Winni ...

considered it "one of the most popular series which has ever appeared in ''Punch''"; alongside it, he rated as Burnand's best comic contributions his burlesques of other writers, such as "The New History of Sandford and Merton" (1872) and "Strapmore" by "Weeder" (1878).

1880s: editor of ''Punch''

The third editor of ''Punch'', Tom Taylor, died in July 1880; the proprietors of the magazine appointed Burnand to succeed him. In Milne's view the magazine's reputation increased considerably under Burnand:

A later biographer, Jane Stedman, writes, "His predecessor, Tom Taylor, had allowed the paper to become heavy, but Burnand's rackety leadership brightened it." Burnand, who declared himself "hostile to no man's religion", banned ''Punchs previous anti-Catholicism, although he was unable to prevent some antisemitic jokes.

One of Burnand's biggest successes, both in ''Punch'' and on stage, was satire of the

The third editor of ''Punch'', Tom Taylor, died in July 1880; the proprietors of the magazine appointed Burnand to succeed him. In Milne's view the magazine's reputation increased considerably under Burnand:

A later biographer, Jane Stedman, writes, "His predecessor, Tom Taylor, had allowed the paper to become heavy, but Burnand's rackety leadership brightened it." Burnand, who declared himself "hostile to no man's religion", banned ''Punchs previous anti-Catholicism, although he was unable to prevent some antisemitic jokes.

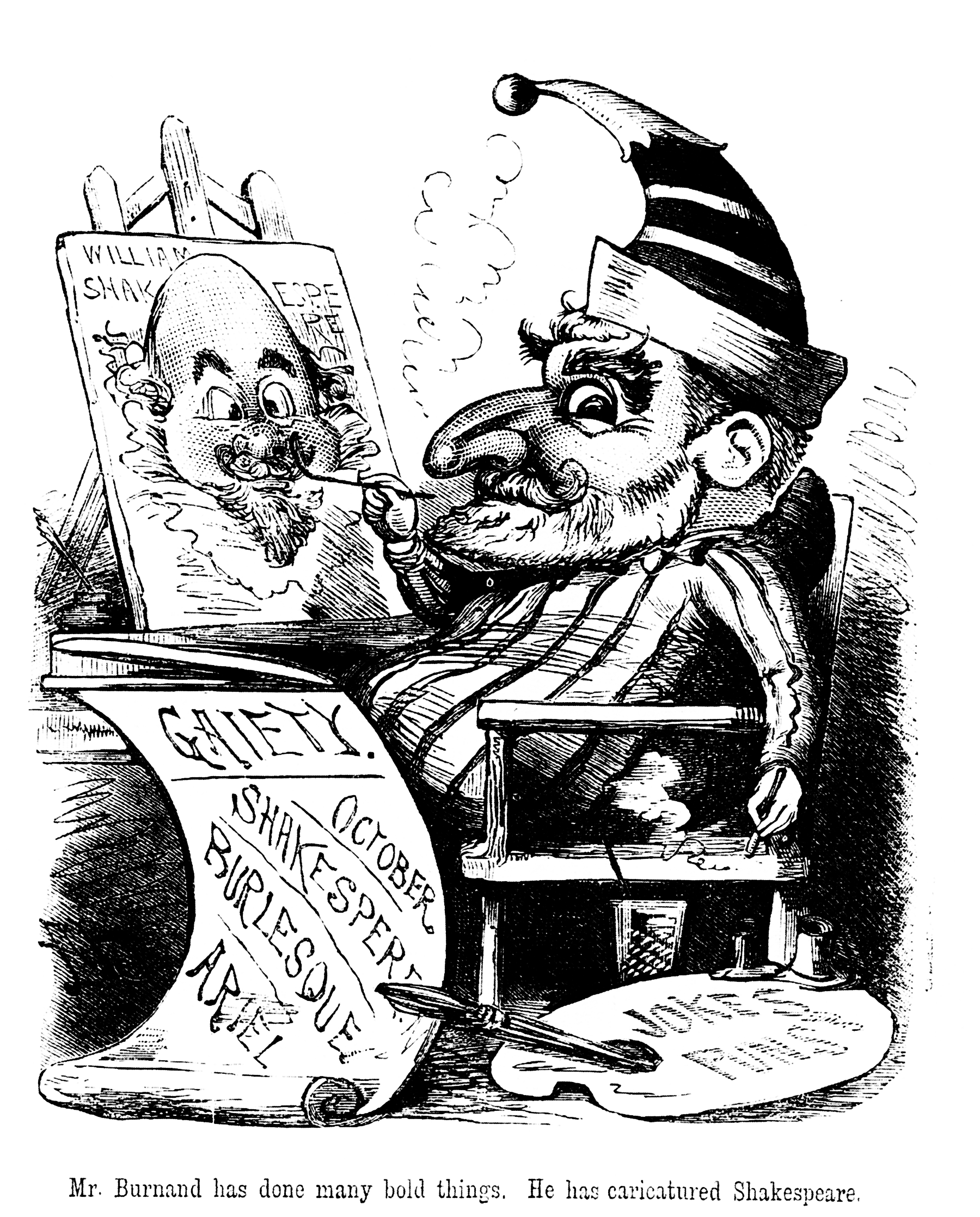

One of Burnand's biggest successes, both in ''Punch'' and on stage, was satire of the aesthetic movement

Aestheticism (also the Aesthetic movement) was an art movement in the late 19th century which privileged the aesthetic value of literature, music and the arts over their socio-political functions. According to Aestheticism, art should be prod ...

. His play '' The Colonel'' (1881), based on ''The Serious Family'', a play by Morris Barnett, ran for 550 performances and toured extensively. It made so much money for the actor-manager Edgar Bruce

Edgar Bruce (c. 1845–1901) was an English actor-manager, appearing in comedies and later producing plays. He built the Prince of Wales Theatre in 1884.

Life

Bruce's first stage appearance was in 1868 at the Prince of Wales's Theatre in Liverpoo ...

that he was able to build the Prince of Wales Theatre

The Prince of Wales Theatre is a West End theatre in Coventry Street, near Leicester Square in London. It was established in 1884 and rebuilt in 1937, and extensively refurbished in 2004 by Sir Cameron Mackintosh, its current owner. The theatre ...

. Burnand rushed ''The Colonel'' into production to make sure that it opened several months before Gilbert and Sullivan

Gilbert and Sullivan was a Victorian era, Victorian-era theatrical partnership of the dramatist W. S. Gilbert (1836–1911) and the composer Arthur Sullivan (1842–1900), who jointly created fourteen comic operas between 1871 and 1896, of which ...

's similarly themed comic opera, ''Patience

(or forbearance) is the ability to endure difficult circumstances. Patience may involve perseverance in the face of delay; tolerance of provocation without responding in disrespect/anger; or forbearance when under strain, especially when faced ...

'', but ''Patience'' ran even longer than ''The Colonel''. Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular playwrights in London in the early 1890s. He is ...

, no fan of Burnand's farces, wrote, in anticipation of seeing ''Patience'': "With Gilbert and Sullivan I am sure we will have something better than the dull farce of ''The Colonel''". For the Gaiety Theatre, Burnand wrote a burlesque of '' The Tempest'' entitled ''Ariel'' in October 1883, with music by Meyer Lutz

Wilhelm Meyer Lutz (19 May 1829 – 31 January 1903) was a German-born British composer and conductor who is best known for light music, musical theatre and burlesques of well-known works.

Emigrating to the UK at the age of 19, Lutz started as ...

, starring Nellie Farren

Ellen "Nellie" Farren (16 April 1848 – 29 April 1904) was an English actress and singer best known for her roles as the "principal boy" in musical burlesques at the Gaiety Theatre.

Born into a theatrical family, Farren began acting as a ch ...

and Arthur Williams. ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' complained of the "flatness and insipidity" of Burnand's text and of his vulgarising the original. ''The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. It is a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', whose parent company Guardian Media Group Limited acquired it in 1993. First published in 1791, it is the w ...

'' was less censorious, finding the piece moderately amusing, and correctly predicting that it would run successfully until it had to make way for the annual Gaiety pantomime at Christmas.

In 1884, Burnand wrote ''Paw Claudian'', a burlesque of the 1883 costume (Byzantine) drama ''Claudian'' by Henry Herman and W. G. Wills, presented at Toole's Theatre

Toole's Theatre, was a 19th-century West End theatre, West End building in William IV Street, near Charing Cross, in the City of Westminster. A succession of auditoria had occupied the site since 1832, serving a variety of functions, including ...

starring J. L. Toole

John Lawrence (J. L.) Toole (12 March 1830 – 30 July 1906) was an English comic actor, actor-manager and theatrical producer. He was famous for his roles in farce and in serio-comic melodramas, in a career that spanned more than four decades, ...

. The same year, he wrote a burlesque of ''Black-Eyed Susan

''Black-Eyed Susan; or, All in the Downs'' is a comic play in three acts by Douglas Jerrold. The story concerns a heroic sailor, William, who has been away from England for three years fighting in the Napoleonic Wars. Meanwhile, his wife, Susa ...

'', called ''Black Eyed See-Usan'', for the Alhambra Theatre

The Alhambra was a popular theatre and music hall located on the east side of Leicester Square, in the West End of London. It was built originally as the Royal Panopticon of Science and Arts opening on 18 March 1854. It was closed after two yea ...

. Burnand wrote several musical works around 1889 and 1890 with the composer Edward Solomon

Edward Solomon (25 July 1855 – 22 January 1895) was an English composer, conductor, orchestrator and pianist. He died at age 39 by which time he had written dozens of works produced for the stage, including several for the D'Oyly Carte Oper ...

, including '' Pickwick'', which was revived in 1894. ''Pickwick'' was recorded by Retrospect Opera in 2016, together with George Grossmith

George Grossmith (9 December 1847 – 1 March 1912) was an English comedian, writer, composer, actor, and singer. His performing career spanned more than four decades. As a writer and composer, he created 18 comic operas, nearly 100 musical ...

's ''Cups and Saucers

''Cups and Saucers'' is a one-act "satirical musical sketch" written and composed by George Grossmith. The piece pokes fun at the china collecting craze of the later Victorian era, which was part of the Aesthetic movement later satirised in ''Pati ...

''. Other stage pieces included adaptations for Augustin Daly

John Augustin Daly (July 20, 1838June 7, 1899) was one of the most influential men in American theatre during his lifetime. Drama critic, theatre manager, playwright, and adapter, he became the first recognized stage director in America. He exer ...

in New York.

Later years

In 1890, Burnand wrote ''Captain Therèse,'' followed later that year by a very successful English version of Audran's operetta, ''

In 1890, Burnand wrote ''Captain Therèse,'' followed later that year by a very successful English version of Audran's operetta, ''La cigale et la fourmi

''La cigale et la fourmi'' (The Grasshopper and the Ant) is a three-act opéra comique, with music by Edmond Audran and words by Henri Chivot and Alfred Duru. Loosely based on Jean de La Fontaine's version of Aesop's Fables, Aesop's fable ''The An ...

'' (the grasshopper and the ant) retitled ''La Cigale'', with additional music by Ivan Caryll

Félix Marie Henri Tilkin (12 May 1861 – 29 November 1921), better known by his pen name Ivan Caryll, was a Belgian-born composer of operettas and Edwardian musical comedies in the English language, who made his career in London and later N ...

. In 1891, he produced an English adaptation of Audran's '' Miss Helyett'', retitled as ''Miss Decima''. Burnand's ''The Saucy Sally'' premiered in 1892, and ''Mrs Ponderbury's Past'' played in 1895. He was knighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the Christian denomination, church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood ...

by King Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910.

The second child and eldest son of Queen Victoria an ...

at Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a London royal residence and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and royal hospitality. It ...

in 1902, for his work on ''Punch''.

Burnand's 1897 comic opera, '' His Majesty'', with music by Alexander Mackenzie, failed despite the contributions of the lyricist Adrian Ross

Arthur Reed Ropes (23 December 1859 – 11 September 1933), better known under the pseudonym Adrian Ross, was a prolific writer of lyrics, contributing songs to more than sixty British musical comedies in the late 19th and early 20th centuries ...

and a Savoy Theatre

The Savoy Theatre is a West End theatre in the Strand in the City of Westminster, London, England. The theatre was designed by C. J. Phipps for Richard D'Oyly Carte and opened on 10 October 1881 on a site previously occupied by the Savoy Pala ...

cast including Ilka Pálmay

Ilka Pálmay (often erroneously written Ilka von Pálmay; 21 September 1859 – 17 February 1945), born Ilona Petráss, was a Hungarian-born singer and actress. Pálmay began her stage career in Hungary by 1880, and by the early 1890s, she wa ...

, George Grossmith

George Grossmith (9 December 1847 – 1 March 1912) was an English comedian, writer, composer, actor, and singer. His performing career spanned more than four decades. As a writer and composer, he created 18 comic operas, nearly 100 musical ...

and Walter Passmore

Walter Henry Passmore (10 May 1867 – 29 August 1946) was an English singer and actor best known as the first successor to George Grossmith in the comic baritone roles in Gilbert and Sullivan operas with the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company.

Passmo ...

. The blame was generally held to be Burnand's. ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' commented, "Mr Burnand's experience as a librettist of comic opera, and Sir Alexander Mackenzie's inexperience in this class of composition might lead the public to expect a brilliant book weighed down by music of too serious and ambitious a type. The exact opposite is the case." Burnand's libretto was judged dull and confused, but Mackenzie's music was "marked by distinction as well as humour." Stedman comments that Burnand's conviction that he, not Gilbert, should have been Sullivan's main collaborator defied the facts: ''The Chieftain'', his rewrite of ''The Contrabandista'' with Sullivan, ran for only 97 performances in 1894, and ''His Majesty'' managed only 61 performances. Nevertheless, Burnand used his position as editor of ''Punch'' to print antagonistic reviews of the plays of Gilbert and refused to give the Gilbert and Sullivan

Gilbert and Sullivan was a Victorian era, Victorian-era theatrical partnership of the dramatist W. S. Gilbert (1836–1911) and the composer Arthur Sullivan (1842–1900), who jointly created fourteen comic operas between 1871 and 1896, of which ...

operas reviews in the magazine.

Burnand's last stage works were a collaboration with J. Hickory Wood, at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane

The Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, commonly known as Drury Lane, is a West End theatre and Grade I listed building in Covent Garden, London, England. The building faces Catherine Street (earlier named Bridges or Brydges Street) and backs onto Dr ...

in 1905, on a pantomime of ''Cinderella

"Cinderella",; french: link=no, Cendrillon; german: link=no, Aschenputtel) or "The Little Glass Slipper", is a folk tale with thousands of variants throughout the world.Dundes, Alan. Cinderella, a Casebook. Madison, Wis: University of Wisconsi ...

'', and he was partly responsible for a pantomime of ''Aladdin'' for the same theatre in 1909. His later contributions to ''Punch'' became increasingly wordy and anecdotal, relying on far-fetched puns, but he was a good judge of talent, and under him the paper prospered. Stedman rates as a high point of his editorship the publication of ''The Diary of a Nobody

''The Diary of a Nobody'' is an English comic novel written by the brothers George and Weedon Grossmith, with illustrations by the latter. It originated as an intermittent serial in ''Punch'' magazine in 1888–89 and first appeared in book for ...

'' by the brothers George and Weedon Grossmith

Walter Weedon Grossmith (9 June 1854 – 14 June 1919), better known as Weedon Grossmith, was an English writer, painter, actor, and playwright best known as co-author of ''The Diary of a Nobody'' (1892) with his brother, music hall comedian ...

, which was soon turned into book form and has never been out of print. He was reluctant to retire, but was persuaded to do so in 1906, and was succeeded by Owen Seaman

Sir Owen Seaman, 1st Baronet (18 September 1861 – 2 February 1936) was a British writer, journalist and poet. He is best known as editor of ''Punch'', from 1906 to 1932.

Biography

Born in Shrewsbury, he was the only son of William Mantle Sea ...

. In 1908, Burnand became the editor of ''The Catholic Who's Who'', published by Burns & Oates

Burns & Oates was a British Roman Catholic publishing house which most recently existed as an imprint of Continuum.

Company history

It was founded by James Burns in 1835, originally as a bookseller. Burns was of Presbyterian background and he g ...

.''The Universe'', 8 January 1909, accessed 17 July 2017

Ramsgate

Ramsgate is a seaside resort, seaside town in the district of Thanet District, Thanet in east Kent, England. It was one of the great English seaside towns of the 19th century. In 2001 it had a population of about 40,000. In 2011, according to t ...

, Kent, on the south coast of England and was a member of the Garrick Club

The Garrick Club is a gentlemen's club in the heart of London founded in 1831. It is one of the oldest members' clubs in the world and, since its inception, has catered to members such as Charles Kean, Henry Irving, Herbert Beerbohm Tree, A ...

in London. He had a very large circle of friends and colleagues who included William Makepeace Thackeray

William Makepeace Thackeray (; 18 July 1811 – 24 December 1863) was a British novelist, author and illustrator. He is known for his satirical works, particularly his 1848 novel '' Vanity Fair'', a panoramic portrait of British society, and t ...

, Mark Lemon and most writers, dramatists and actors of the day. George Grossmith wrote:

After a winter of bronchitis, Burnand died in 1917 at his home in Ramsgate, at the age of 80. He was buried in the cemetery at St Augustine's Abbey church in Ramsgate.

Books

Burnand's best-known book, ''Happy Thoughts'', was originally published in ''Punch'' in 1863–64 and frequently reprinted. This was followed by ''My Time and What I've Done with It'' (1874); ''Personal Reminiscences of the A.D.C., Cambridge,'' (1880); ''The Incomplete Angler'' (1887); ''Very Much Abroad'' (1890); ''Rather at Sea'' (1890); ''Quite at Home'' (1890); ''The Real Adventures of Robinson Crusoe'' (1893); ''Records and Reminiscences,'' (1904); and ''The Fox's Frolic: or, a day with the topsy turvy hunt'', illustrated byHarry B. Neilson

Henry Bingham Neilson (1861 – 13 October 1941), who signed his work and was usually credited as Harry B. Neilson, less often as H. B. Neilson, was a British illustrator, mostly of children’s books.

His first career was as an engineer and el ...

(1917).

Notes and references

;Notes ;ReferencesSources

* * * * * * * * *External links

* *Profile of Burnand

F. C. Burnand letters and memoranda, 1873–1907

held by the Billy Rose Theatre Division,

New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center, at 40 Lincoln Center Plaza, is located in Manhattan, New York City, at the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts on the Upper West Side, between the Metro ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Burnand, Francis

1836 births

1917 deaths

Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge

Converts to Roman Catholicism

English humorists

English magazine editors

English opera librettists

Knights Bachelor

People associated with Gilbert and Sullivan

People educated at Eton College

People from Ramsgate

English male dramatists and playwrights

Punch (magazine) people

English male non-fiction writers