Sir Charles Sherrington on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

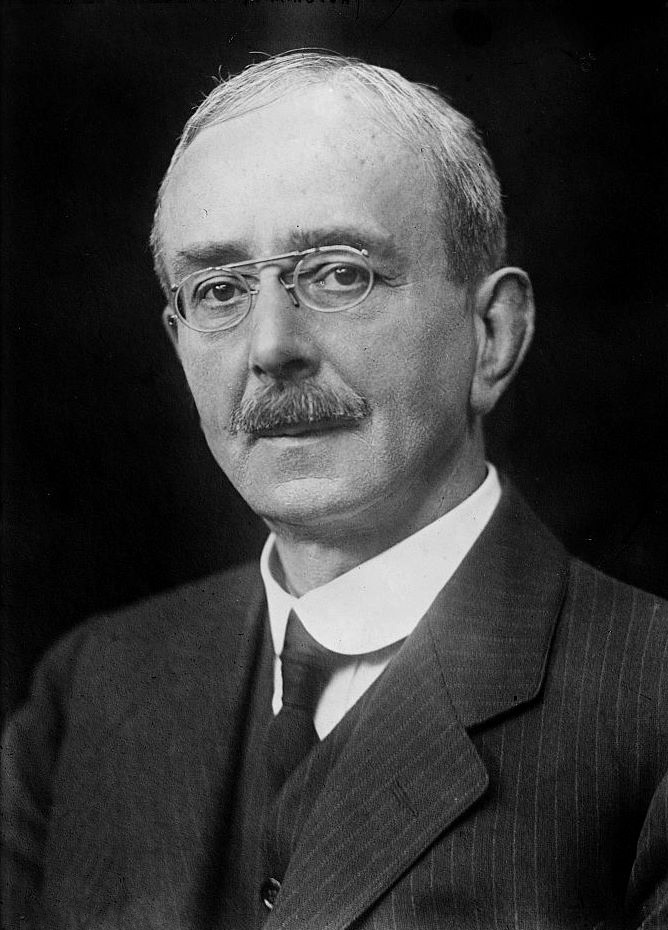

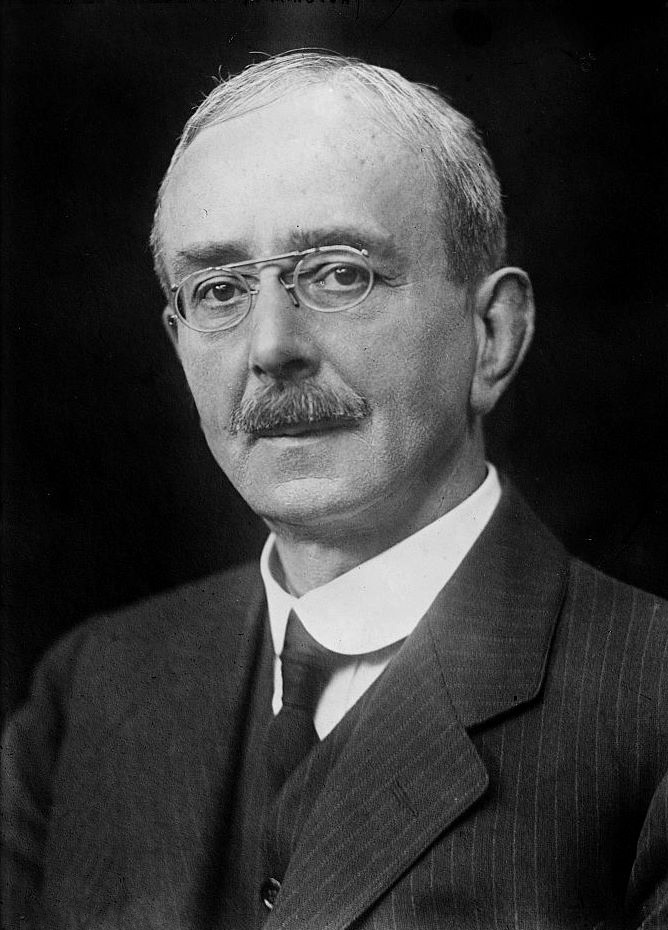

Sir Charles Scott Sherrington (27 November 1857 – 4 March 1952) was an eminent English neurophysiologist. His experimental research established many aspects of contemporary neuroscience, including the concept of the spinal reflex as a system involving connected neurons (the "

The 7th

The 7th

In 1891, Sherrington was appointed as superintendent of the Brown Institute for Advanced Physiological and Pathological Research of the University of London, a center for human and animal physiological and pathological research. Sherrington succeeded Sir Victor Alexander Haden Horsley. There, Sherrington worked on segmental distribution of the spinal dorsal and ventral roots, he mapped the sensory dermatomes, and in 1892 discovered that muscle spindles initiated the

In 1891, Sherrington was appointed as superintendent of the Brown Institute for Advanced Physiological and Pathological Research of the University of London, a center for human and animal physiological and pathological research. Sherrington succeeded Sir Victor Alexander Haden Horsley. There, Sherrington worked on segmental distribution of the spinal dorsal and ventral roots, he mapped the sensory dermatomes, and in 1892 discovered that muscle spindles initiated the

While at Oxford, Sherrington kept hundreds of microscope slides in a specially constructed box labelled "Sir Charles Sherrington's Histology Demonstration Slides". As well as histology demonstration slides, the box contains slides which may be related to original breakthroughs such as cortical localization in the brain; slides from contemporaries such as

While at Oxford, Sherrington kept hundreds of microscope slides in a specially constructed box labelled "Sir Charles Sherrington's Histology Demonstration Slides". As well as histology demonstration slides, the box contains slides which may be related to original breakthroughs such as cortical localization in the brain; slides from contemporaries such as

A reflection on Sherrington's philosophical thought. Sherrington had long studied the 16th century French physician

Sherrington was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1893.

* 1899 Baly Gold Medal of the

Sherrington was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1893.

* 1899 Baly Gold Medal of the Sherrington's Presidential Address to the British Association Meeting, held at Hull in 1922

/ref> * 1924

neuron doctrine

The neuron doctrine is the concept that the nervous system is made up of discrete individual cells, a discovery due to decisive neuro-anatomical work of Santiago Ramón y Cajal and later presented by, among others, H. Waldeyer-Hartz. The term '' ...

"), and the ways in which signal transmission between neurons can be potentiated or depotentiated. Sherrington himself coined the word "synapse

In the nervous system, a synapse is a structure that permits a neuron (or nerve cell) to pass an electrical or chemical signal to another neuron or to the target effector cell.

Synapses are essential to the transmission of nervous impulses from ...

" to define the connection between two neurons. His book ''The Integrative Action of the Nervous System'' (1906) is a synthesis of this work, in recognition of which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, accord ...

in 1932 (along with Edgar Adrian

Edgar Douglas Adrian, 1st Baron Adrian (30 November 1889 – 4 August 1977) was an English electrophysiologist and recipient of the 1932 Nobel Prize for Physiology, won jointly with Sir Charles Sherrington for work on the function of neurons. ...

).

In addition to his work in physiology, Sherrington did research in histology

Histology,

also known as microscopic anatomy or microanatomy, is the branch of biology which studies the microscopic anatomy of biological tissues. Histology is the microscopic counterpart to gross anatomy, which looks at larger structures vis ...

, bacteriology Bacteriology is the branch and specialty of biology that studies the morphology, ecology, genetics and biochemistry of bacteria as well as many other aspects related to them. This subdivision of microbiology involves the identification, classificat ...

, and pathology

Pathology is the study of the causes and effects of disease or injury. The word ''pathology'' also refers to the study of disease in general, incorporating a wide range of biology research fields and medical practices. However, when used in ...

. He was president of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

in the early 1920s.

Biography

Early years and education

Official biographies claim Charles Scott Sherrington was born inIslington

Islington () is a district in the north of Greater London, England, and part of the London Borough of Islington. It is a mainly residential district of Inner London, extending from Islington's High Street to Highbury Fields, encompassing the ar ...

, London, England, on 27 November 1857 and that he was the son of James Norton Sherrington, a country doctor, and his wife Anne Thurtell. However James Norton Sherrington was an ironmonger and artist's colourman in Great Yarmouth, not a doctor, and died in Yarmouth in 1848, nearly 9 years before Charles was born. In the 1861 census, Charles is recorded as Charles Scott (boarder, 4, born India) with Anne Sherrington (widow) as the head and Caleb Rose (visitor, married, surgeon). He was brought up in this household with Caleb recorded as head in 1871, although Anne and Caleb did not marry until after the death of his wife in 1880. The relationship between Charles and his childhood family is unknown. During the 1860s the whole family moved to Anglesea Road, Ipswich

Ipswich () is a port town and borough in Suffolk, England, of which it is the county town. The town is located in East Anglia about away from the mouth of the River Orwell and the North Sea. Ipswich is both on the Great Eastern Main Line r ...

, reputedly because London exacerbated Caleb Rose's tendency to asthma.

Sherrington's origins have been discussed in several published sources: Chris Moss and Susan Hunter, in the Journal of Medical Biography

The ''Journal of Medical Biography'' is a peer-reviewed academic journal established in 1993 covering the lives of people in or associated with medicine, including medical figures and well-known characters from history and their afflictions. The jo ...

of January 2018, presented an article discussing the potential origins of Charles Sherrington, i.e. whether he was born in India of unknown parents, or was the illegitimate child of Caleb Rose and Anne Sherrington. Erling Norrby, PhD, in ''Nobel Prizes and Notable Discoveries'' (2016) observed: "His family origin apparently is not properly given in his official biography. Considering that motherhood is a matter of fact and fatherhood a matter of opinion, it can be noted that his father was not James Norton Sherrington, from whom his family name was derived. Charles was born 9 years after the death of his presumed father. Instead Charles and his two brothers were the illegitimate sons of Caleb Rose, a highly regarded Ipswich surgeon." In ''Ipswich Town: A History'', Susan Gardiner writes: "George and William Sherrington, along with their older brother, Charles, were almost certainly the illegitimate sons of Anne Brookes, née Thurtell and Caleb Rose, a leading surgeon from Ipswich, with whom she was living in College Road, Islington at the time that all three boys were born. No father was named in the baptism register of St James' Church, Clerkenwell, and there is no official record of the registration of any of their births. It was claimed they were the sons of a country doctor, James Norton Sherrington. However, it was with Caleb Rose that Anne and the three Sherrington boys moved to Anglesea Road, Ipswich in 1860 and the couple were married in 1880 after Caleb's first wife had died." Of James Norton Sherrington, Judith Swazey, in ''Reflexes and Motor Integration: Sherrington's Concept of Integrative Action'' (1969), quotes Charles Scott Sherrington's son, Carr Sherrington: "James N. Sherrington was always called Mr. and I have no knowledge that he was a Dr. either in law or in medicine... ewas mainly interested in art and was a personal friend of J. B. Crone and other painters."

Caleb Rose was noteworthy as both a classical scholar and an archaeologist. At the family's Edgehill House in Ipswich one could find a fine selection of paintings, books, and geological specimens. Through Rose's interest in the Norwich School of Painters

The Norwich School of painters was the first provincial art movement established in Britain, active in the early 19th century. Artists of the school were inspired by the natural environment of the Norfolk landscape and owed some influence to the wo ...

, Sherrington gained a love of art. Intellectuals frequented the house regularly. It was this environment that fostered Sherrington's academic sense of wonder. Even before matriculation, the young Sherrington had read Johannes Müller's ''Elements of Physiology''. The book was given to him by Caleb Rose.

Sherrington entered Ipswich School

Ipswich School is a public school (English independent day and boarding school) for pupils aged 3 to 18 in Ipswich, Suffolk, England.

North of the town centre, Ipswich School has four parts on three adjacent sites. The Pre-Prep and Nursery ...

in 1871. Thomas Ashe

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the Ap ...

, a famous English poet, taught at the school. Ashe served as an inspiration to Sherrington, instilling a love of classics and the desire to travel.

Rose had pushed Sherrington towards medicine. Sherrington first began to study with the Royal College of Surgeons of England

The Royal College of Surgeons of England (RCS England) is an independent professional body and registered charity that promotes and advances standards of surgical care for patients, and regulates surgery and dentistry in England and Wales. The ...

. He also sought to study at Cambridge, but a bank failure had devastated the family's finances. Sherrington elected to enroll at St Thomas' Hospital

St Thomas' Hospital is a large NHS teaching hospital in Central London, England. It is one of the institutions that compose the King's Health Partners, an academic health science centre. Administratively part of the Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foun ...

in September 1876 as a "perpetual pupil". He did so in order to allow his two younger brothers to do so ahead of him. The two studied law there. Medical studies at St. Thomas's Hospital were intertwined with studies at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge

Gonville and Caius College, often referred to simply as Caius ( ), is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1348, it is the fourth-oldest of the University of Cambridge's 31 colleges and one of th ...

. Physiology was Sherrington's chosen major at Cambridge. There, he studied under the "father of British physiology," Sir Michael Foster.

Sherrington played football

Football is a family of team sports that involve, to varying degrees, kicking a ball to score a goal. Unqualified, the word ''football'' normally means the form of football that is the most popular where the word is used. Sports commonly c ...

for his grammar school, and for Ipswich Town Football Club

Ipswich Town Football Club is a professional association football club based in Ipswich, Suffolk, England. They play in League One, the third tier of the English football league system.

The club was founded in 1878 but did not turn profession ...

; he played rugby

Rugby may refer to:

Sport

* Rugby football in many forms:

** Rugby league: 13 players per side

*** Masters Rugby League

*** Mod league

*** Rugby league nines

*** Rugby league sevens

*** Touch (sport)

*** Wheelchair rugby league

** Rugby union: 1 ...

for St. Thomas's, was on the rowing team at Oxford. During June 1875, Sherrington passed his preliminary examination in general education at the Royal College of Surgeons of England

The Royal College of Surgeons of England (RCS England) is an independent professional body and registered charity that promotes and advances standards of surgical care for patients, and regulates surgery and dentistry in England and Wales. The ...

(RCS). This preliminary exam was required for Fellowship, and also exempted him from a similar exam for the Membership. In April 1878, he passed his Primary Examination for the Membership of the RCS, and twelve months later the Primary for Fellowship.

In October 1879, Sherrington entered Cambridge as a non-collegiate student. The following year he entered Gonville and Caius College

Gonville and Caius College, often referred to simply as Caius ( ), is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1348, it is the fourth-oldest of the University of Cambridge's 31 colleges and one of th ...

. Sherrington was a first-rate student. In June 1881, he took Part I in the Natural Sciences Tripos

The Natural Sciences Tripos (NST) is the framework within which most of the science at the University of Cambridge is taught. The tripos includes a wide range of Natural Sciences from physics, astronomy, and geoscience, to chemistry and biology, ...

(NST) and was awarded a '' Starred first'' in physiology

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemical ...

; there were nine candidates in all (eight men, one woman), of whom five gained First-class honours

The British undergraduate degree classification system is a grading structure for undergraduate degrees or bachelor's degrees and integrated master's degrees in the United Kingdom. The system has been applied (sometimes with significant variati ...

(''Firsts''); in June 1883, in Part II of the NST, he also gained a First, alongside William Bateson

William Bateson (8 August 1861 – 8 February 1926) was an English biologist who was the first person to use the term genetics to describe the study of heredity, and the chief populariser of the ideas of Gregor Mendel following their rediscove ...

. Walter Holbrook Gaskell, one of Sherrington's tutors, informed him in November 1881 that he had earned the highest marks for his year in botany, human anatomy, and physiology; second in zoology; and highest overall. John Newport Langley

John Newport Langley (2 November 1852 – 5 November 1925) was a British physiologist, who made substantive discoveries about the nervous system and secretion.

Life

He was born in Newbury, Berkshire the son of John Langley, the local schoolmast ...

was Sherrington's other tutor. The two were interested in how anatomical structure is expressed in physiological function.

Sherrington earned his Membership of the Royal College of Surgeons

Membership of the Royal Colleges of Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland (MRCS) is a postgraduate diploma for surgeons in the United Kingdom, UK and Ireland. Obtaining this qualification allows a doctor to become a member of one of the four sur ...

on 4 August 1884. In 1885, he obtained a First Class in the Natural Science Tripos with the mark of distinction. In the same year, Sherrington earned the degree of M.B., Bachelor of Medicine and Surgery from Cambridge. In 1886, Sherrington added the title of L.R.C.P., Licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians.

Seventh International Medical Congress

The 7th

The 7th International Medical Congress

The International Medical Congress (french: Congrès International de Médecine) was a series of international scientific conferences on medicine that took place, periodically, from 1867 until 1913.

The idea of such a congress came in 1865, dur ...

was held in London in 1881. It was at this conference that Sherrington began his work in neurological research. At the conference controversy broke out. Friedrich Goltz

Friedrich Leopold Goltz (14 August 1834 – 5 May 1902) was a German physiologist and nephew of the writer Bogumil Goltz.

Born in Posen (Poznań), Grand Duchy of Posen, he studied medicine at the University of Königsberg, and following two year ...

of Strasbourg

Strasbourg (, , ; german: Straßburg ; gsw, label=Bas Rhin Alsatian, Strossburi , gsw, label=Haut Rhin Alsatian, Strossburig ) is the prefecture and largest city of the Grand Est region of eastern France and the official seat of the Eu ...

argued that localized function in the cortex

Cortex or cortical may refer to:

Biology

* Cortex (anatomy), the outermost layer of an organ

** Cerebral cortex, the outer layer of the vertebrate cerebrum, part of which is the ''forebrain''

*** Motor cortex, the regions of the cerebral cortex i ...

did not exist. Goltz came to this conclusion after observing dogs who had parts of their brains removed. David Ferrier

Sir David Ferrier FRS (13 January 1843 – 19 March 1928) was a pioneering Scottish neurologist and psychologist. Ferrier conducted experiments on the brains of animals such as monkeys and in 1881 became the first scientist to be prosecuted ...

, who became a hero of Sherrington's, disagreed. Ferrier maintained that there was localization of function in the brain. Ferrier's strongest evidence was a monkey who suffered from hemiplegia

Hemiparesis, or unilateral paresis, is weakness of one entire side of the body ('' hemi-'' means "half"). Hemiplegia is, in its most severe form, complete paralysis of half of the body. Hemiparesis and hemiplegia can be caused by different medic ...

, paralysis affecting one side of the body only, after a cerebral lesion.

A committee, including Langley, was made up to investigate. Both the dog and the monkey were chloroformed. The right hemisphere of the dog was delivered to Cambridge for examination. Sherrington performed a histological examination of the hemisphere, acting as a junior colleague to Langley. In 1884, Langley and Sherrington reported on their findings in a paper. The paper was the first for Sherrington.

Travel

In the winter of 1884–1885, Sherrington left England for Strasbourg. There, he worked with Goltz. Goltz, like many others, positively influenced Sherrington. Sherrington later said of Goltz that: " taught one that in all things only the best is good enough." A case ofasiatic cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

had broken out in Spain in 1885. A Spanish doctor claimed to have produced a vaccine to fight the outbreak. Under the auspices of Cambridge University

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

, the Royal Society of London

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

, and the Association for Research in Medicine, a group was put together to travel to Spain to investigate. C.S. Roy, J. Graham Brown, and Sherrington formed the group. Roy was Sherrington's friend and the newly elected professor of pathology at Cambridge. As the three travelled to Toledo, Sherrington was skeptical of the Spanish doctor. Upon returning, the three presented a report to the Royal Society. The report discredited the Spaniard's claim.

Sherrington did ''not'' meet Santiago Ramón y Cajal

Santiago Ramón y Cajal (; 1 May 1852 – 17 October 1934) was a Spanish neuroscientist, pathologist, and histologist specializing in neuroanatomy and the central nervous system. He and Camillo Golgi received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Med ...

on this trip. While Sherrington and his group remained in Toledo, Cajal was hundreds of miles away in Zaragoza

Zaragoza, also known in English as Saragossa,''Encyclopædia Britannica'"Zaragoza (conventional Saragossa)" is the capital city of the Zaragoza Province and of the autonomous community of Aragon, Spain. It lies by the Ebro river and its tributari ...

.

Later that year Sherrington travelled to Rudolf Virchow

Rudolf Ludwig Carl Virchow (; or ; 13 October 18215 September 1902) was a German physician, anthropologist, pathologist, prehistorian, biologist, writer, editor, and politician. He is known as "the father of modern pathology" and as the founder ...

in Berlin to inspect the cholera specimens he procured in Spain. Virchow later on sent Sherrington to Robert Koch

Heinrich Hermann Robert Koch ( , ; 11 December 1843 – 27 May 1910) was a German physician and microbiologist. As the discoverer of the specific causative agents of deadly infectious diseases including tuberculosis, cholera (though the Vibrio ...

for a six weeks' course in technique. Sherrington ended up staying with Koch for a year to do research in bacteriology. Under these two, Sherrington parted with a good foundation in physiology, morphology

Morphology, from the Greek and meaning "study of shape", may refer to:

Disciplines

* Morphology (archaeology), study of the shapes or forms of artifacts

* Morphology (astronomy), study of the shape of astronomical objects such as nebulae, galaxies ...

, histology

Histology,

also known as microscopic anatomy or microanatomy, is the branch of biology which studies the microscopic anatomy of biological tissues. Histology is the microscopic counterpart to gross anatomy, which looks at larger structures vis ...

, and pathology

Pathology is the study of the causes and effects of disease or injury. The word ''pathology'' also refers to the study of disease in general, incorporating a wide range of biology research fields and medical practices. However, when used in ...

. During this period he may have also studied with Waldeyer and Zuntz.

In 1886, Sherrington went to Italy to again investigate a cholera outbreak. While in Italy, Sherrington spent much time in art galleries. It was in this country that Sherrington's love for rare books became an obsession.

Employment

In 1891, Sherrington was appointed as superintendent of the Brown Institute for Advanced Physiological and Pathological Research of the University of London, a center for human and animal physiological and pathological research. Sherrington succeeded Sir Victor Alexander Haden Horsley. There, Sherrington worked on segmental distribution of the spinal dorsal and ventral roots, he mapped the sensory dermatomes, and in 1892 discovered that muscle spindles initiated the

In 1891, Sherrington was appointed as superintendent of the Brown Institute for Advanced Physiological and Pathological Research of the University of London, a center for human and animal physiological and pathological research. Sherrington succeeded Sir Victor Alexander Haden Horsley. There, Sherrington worked on segmental distribution of the spinal dorsal and ventral roots, he mapped the sensory dermatomes, and in 1892 discovered that muscle spindles initiated the stretch reflex

The stretch reflex (myotatic reflex), or more accurately "muscle stretch reflex", is a muscle contraction in response to stretching within the muscle. The reflex functions to maintain the muscle at a constant length. The term deep tendon reflex is ...

. The institute allowed Sherrington to study many animals, both small and large. The Brown Institute had enough space to work with large primates such as apes.

Liverpool

Sherrington's first job of full-professorship came with his appointment as Holt Professor of Physiology atLiverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

in 1895, succeeding Francis Gotch. With his appointment to the Holt Chair, Sherrington ended his active work in pathology. Working on cats, dogs, monkeys, and apes that had been bereaved of their cerebral hemispheres, he found that reflexes must be considered integrated activities of the total organism, not just the result of activities of the so-called reflex-arcs, a concept then generally accepted. There he continued his work on reflexes and reciprocal innervation

René Descartes (1596–1650) was one of the first to conceive a model of reciprocal innervation (in 1626) as the principle that provides for the control of agonist and antagonist muscles. Reciprocal innervation describes skeletal muscles as ...

. His papers on the subject were synthesized into the Croonian

The Croonian Medal and Lecture is a prestigious award, a medal, and lecture given at the invitation of the Royal Society and the Royal College of Physicians.

Among the papers of William Croone at his death in 1684, was a plan to endow a single ...

lecture of 1897.

Sherrington showed that muscle excitation was inversely proportional to the inhibition of an opposing group of muscles. Speaking of the excitation-inhibition relationship, Sherrington said "desistence from action may be as truly active as is the taking of action." Sherrington continued his work on reciprocal innervation during his years at Liverpool. Come 1913, Sherrington was able to say that "the process of excitation and inhibition may be viewed as polar opposites ..the one is able to neutralize the other." Sherrington's work on reciprocal innervation was a notable contribution to the knowledge of the spinal cord.

Oxford

As early as 1895, Sherrington had tried to gain employment at Oxford University. By 1913, the wait was over. Oxford offered Sherrington the Waynflete Chair of Physiology atMagdalen College

Magdalen College (, ) is a constituent college of the University of Oxford. It was founded in 1458 by William of Waynflete. Today, it is the fourth wealthiest college, with a financial endowment of £332.1 million as of 2019 and one of the s ...

. The electors to that chair unanimously recommended Sherrington without considering any other candidates. Sherrington enjoyed the honor of teaching many bright students at Oxford, including Wilder Penfield

Wilder Graves Penfield (January 26, 1891April 5, 1976) was an American Canadians, American-Physicians in Canada, Canadian neurosurgeon. He expanded brain surgery's methods and techniques, including mapping the functions of various regions of th ...

, who he introduced to the study of the brain. Several of his students were Rhodes scholars, three of whom – Sir John Eccles

Sir John Carew Eccles (27 January 1903 – 2 May 1997) was an Australian neurophysiologist and philosopher who won the 1963 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work on the synapse. He shared the prize with Andrew Huxley and Alan Llo ...

, Ragnar Granit

Ragnar Arthur Granit (30 October 1900 – 12 March 1991) was a Finnish-Swedish scientist who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1967 along with Haldan Keffer Hartline and George Wald "for their discoveries concerning the ...

, and Howard Florey

Howard Walter Florey, Baron Florey (24 September 189821 February 1968) was an Australian pharmacologist and pathologist who shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1945 with Sir Ernst Chain and Sir Alexander Fleming for his role in ...

– went on to be Nobel laureates. Sherrington also influenced American pioneer brain surgeon Harvey Williams Cushing

Harvey Williams Cushing (April 8, 1869 – October 7, 1939) was an American neurosurgeon, pathologist, writer, and draftsman. A pioneer of brain surgery, he was the first exclusive neurosurgeon and the first person to describe Cushing's disease. ...

.

Sherrington's philosophy as a teacher can be seen in his response to the question of what was the real function of Oxford University in the world. Sherrington said:

"after some hundreds of years of experience we think that we have learned here in Oxford how to teach what is known. But now with the undeniable upsurge of scientific research, we cannot continue to rely on the mere fact that we have learned how to teach what is known. We must learn to teach the best attitude to what is not yet known. This also may take centuries to acquire but we cannot escape this new challenge, nor do we want to."

While at Oxford, Sherrington kept hundreds of microscope slides in a specially constructed box labelled "Sir Charles Sherrington's Histology Demonstration Slides". As well as histology demonstration slides, the box contains slides which may be related to original breakthroughs such as cortical localization in the brain; slides from contemporaries such as

While at Oxford, Sherrington kept hundreds of microscope slides in a specially constructed box labelled "Sir Charles Sherrington's Histology Demonstration Slides". As well as histology demonstration slides, the box contains slides which may be related to original breakthroughs such as cortical localization in the brain; slides from contemporaries such as Angelo Ruffini

Angelo Ruffini (Pretare of Arquata del Tronto; 1864–1929) was an Italian histologist and embryologist.

He studied medicine at the University of Bologna, where beginning in 1894 he taught classes in histology. In 1903 he attained the chair of e ...

and Gustav Fritsch

Gustav Theodor Fritsch (5 March 1838 – 12 June 1927) was a German anatomist, anthropologist, traveller and physiologist from Cottbus.

Fritsch studied natural science and medicine in Berlin, Breslau and Heidelberg. In 1874 he became an ass ...

; and slides from colleagues at Oxford such as John Burdon-Sanderson

Sir John Scott Burdon-Sanderson, 1st Baronet, FRS, HFRSE D.Sc. (21 December 182823 November 1905) was an English physiologist born near Newcastle upon Tyne, and a member of a well known Northumbrian family.

Biography

He was born at Jesmond ...

– the first Waynflete Chair of Physiology – and Derek Denny-Brown, who worked with Sherrington at Oxford (1924–1928)).

Sherrington's teachings at Oxford were interrupted by World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. When the war started, it left his classes with only nine students. During the war, he laboured at a shell factory to support the war and to study fatigue in general, but specifically industrial fatigue. His weekday work hours were from 7:30am to 8:30pm; and from 7:30am to 6:00pm on the weekends.

In March 1916, Sherrington fought for women to be admitted to the medical school at Oxford.

He lived at 9 Chadlington Road in north Oxford from 1916 to 1934, and on 28 April 2022 an Oxfordshire blue plaque in his honour was unveiled on this house.

Retirement

Charles Sherrington retired from Oxford in the year of 1936. He then moved to his boyhood town of Ipswich, where he built a house. There, he kept up a large correspondence with pupils and others from around the world. He also continued to work on his poetic, historical, and philosophical interests. From 1944 until his death he was President of theIpswich Museum

Ipswich Museum is a registered museum of culture, history and natural heritage located on High Street in Ipswich, the county town of Suffolk. It was historically the leading regional museum in Suffolk, housing collections drawn from both the fo ...

, on the committee he had previously served.

Sherrington's mental faculties were crystal clear up to the time of his sudden death, which was caused by a sudden heart failure at age 94. His bodily health, however, did suffer in old age. Arthritis was a major burden. Speaking of his condition, Sherrington said "old age isn't pleasant one can't do things for oneself." The arthritis put Sherrington in a nursing home in the year before his death, in 1951.

Family

On 27 August 1891, Sherrington married Ethel Mary Wright (d.1933), daughter of John Ely Wright of Preston Manor, Suffolk, England. They had one child, a son named Charles ("Carr") E.R. Sherrington, who was born in 1897. His wife was both loyal and lively. She was a great host. On weekends during the Oxford years the couple would frequently host a large group of friends and acquaintances at their house for an enjoyable afternoon.Publications

''The Integrative Action of the Nervous System''

Published in 1906, this was a compendium of ten of Sherrington'sSilliman lecture

The Silliman Memorial lectures series has been published by Yale University since 1901. The lectures were established by the university on the foundation of a bequest of $80,000, left in 1883 by Augustus Ely Silliman, in memory of his mother, Mrs. ...

s, delivered at Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wo ...

in 1904. The book discussed neuron theory, the "synapse

In the nervous system, a synapse is a structure that permits a neuron (or nerve cell) to pass an electrical or chemical signal to another neuron or to the target effector cell.

Synapses are essential to the transmission of nervous impulses from ...

" (a term he had introduced in 1897, the word itself suggested by classicist

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Classics ...

A. W. Verrall), communication between neurons, and a mechanism for the reflex-arc function. The work effectively resolved the debate between neuron and reticular theory Reticular theory is an obsolete scientific theory in neurobiology that stated that everything in the nervous system, such as brain, is a single continuous network. The concept was postulated by a German anatomist Joseph von Gerlach in 1871, and was ...

in mammals, thereby shaping our understanding of the central nervous system. He theorized that the nervous system coordinates various parts of the body and that the reflexes are the simplest expressions of the interactive action of the nervous system, enabling the entire body to function toward a definite purpose. Sherrington pointed out that reflexes must be goal-directive and purposive. Furthermore, he established the nature of postural reflexes and their dependence on the anti-gravity stretch reflex

The stretch reflex (myotatic reflex), or more accurately "muscle stretch reflex", is a muscle contraction in response to stretching within the muscle. The reflex functions to maintain the muscle at a constant length. The term deep tendon reflex is ...

and traced the afferent stimulus to the proprioceptive

Proprioception ( ), also referred to as kinaesthesia (or kinesthesia), is the sense of self-movement, force, and body position. It is sometimes described as the "sixth sense".

Proprioception is mediated by proprioceptors, mechanosensory neurons ...

end organs, which he had previously shown to be sensory in nature ("proprioceptive" was another term he had coined). The work was dedicated to Ferrier.

''Mammalian Physiology: a Course of Practical Exercises''

The textbook was published in 1919 at the first possible moment after Sherrington's arrival at Oxford and the end of the War.''The Assaying of Brabantius and other Verse''

This collection of previously published war-time poems was Sherrington's first major poetic release, published in 1925. Sherrington's poetic side was inspired byJohann Wolfgang von Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as trea ...

. Sherrington was fond of Goethe the poet, but not Goethe the scientist. Speaking of Goethe's scientific writings, Sherrington said "to appraise them is not a congenial task."

Jean Fernel

Jean François Fernel ( Latinized as Ioannes Fernelius; 1497 – 26 April 1558) was a French physician who introduced the term "physiology" to describe the study of the body's function. He was the first person to describe the spinal canal. The l ...

, and grew so familiar with him that he considered him a friend. During the academic year 1937-38, Sherrington delivered the Gifford lectures

The Gifford Lectures () are an annual series of lectures which were established in 1887 by the will of Adam Gifford, Lord Gifford. Their purpose is to "promote and diffuse the study of natural theology in the widest sense of the term – in o ...

at the University of Edinburgh. They focused on Fernel and his times, and formed the basis of ''Man on His Nature.'' The book was published in 1940, with a revised edition in 1951. It explores philosophical thoughts about the mind, human existence, and God, in accordance with natural theology

Natural theology, once also termed physico-theology, is a type of theology that seeks to provide arguments for theological topics (such as the existence of a deity) based on reason and the discoveries of science.

This distinguishes it from ...

. Chapters of the book align with the twelve zodiac signs

In Western astrology, astrological signs are the twelve 30-degree sectors that make up Earth's 360-degree orbit around the Sun. The signs enumerate from the first day of spring, known as the First Point of Aries, which is the vernal equinox. ...

. In his ideas on mind and cognition, Sherrington introduced the idea that neurons work as groups in a "million-fold democracy" to produce outcomes rather than with central control.

Honours and awards

Sherrington was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1893.

* 1899 Baly Gold Medal of the

Sherrington was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1893.

* 1899 Baly Gold Medal of the Royal College of Physicians

The Royal College of Physicians (RCP) is a British professional membership body dedicated to improving the practice of medicine, chiefly through the accreditation of physicians by examination. Founded by royal charter from King Henry VIII in 1 ...

of London

* 1905 Royal Medal

The Royal Medal, also known as The Queen's Medal and The King's Medal (depending on the gender of the monarch at the time of the award), is a silver-gilt medal, of which three are awarded each year by the Royal Society, two for "the most important ...

of the Royal Society of London

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

* 1922 Knight Grand Cross

Grand Cross is the highest class in many orders, and manifested in its insignia. Exceptionally, the highest class may be referred to as Grand Cordon or equivalent. In other cases, there may exist a rank even higher than Grand Cross, e.g. Grand ...

of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

* 1922 President of the British Association

The British Science Association (BSA) is a charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BA). The current Chie ...

for the year 1922–1923/ref> * 1924

Order of Merit

The Order of Merit (french: link=no, Ordre du Mérite) is an order of merit for the Commonwealth realms, recognising distinguished service in the armed forces, science, art, literature, or for the promotion of culture. Established in 1902 by K ...

* 1932 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, according ...

At the time of his death Sherrington received ''honoris causa'' Doctors from twenty-two universities: Oxford, Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

, Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

, Strasbourg

Strasbourg (, , ; german: Straßburg ; gsw, label=Bas Rhin Alsatian, Strossburi , gsw, label=Haut Rhin Alsatian, Strossburig ) is the prefecture and largest city of the Grand Est region of eastern France and the official seat of the Eu ...

, Louvain

Leuven (, ) or Louvain (, , ; german: link=no, Löwen ) is the capital and largest city of the province of Flemish Brabant in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is located about east of Brussels. The municipality itself comprises the historic c ...

, Uppsala

Uppsala (, or all ending in , ; archaically spelled ''Upsala'') is the county seat of Uppsala County and the List of urban areas in Sweden by population, fourth-largest city in Sweden, after Stockholm, Gothenburg, and Malmö. It had 177,074 inha ...

, Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the third-largest city and second-largest metropolitan area of France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of t ...

, Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population ...

, Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

, London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

, Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the ancho ...

, Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

, Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

, Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

, Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-most populous city in Canada and List of towns in Quebec, most populous city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian ...

, Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

, Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

, Sheffield

Sheffield is a city status in the United Kingdom, city in South Yorkshire, England, whose name derives from the River Sheaf which runs through it. The city serves as the administrative centre of the City of Sheffield. It is Historic counties o ...

, Bern

german: Berner(in)french: Bernois(e) it, bernese

, neighboring_municipalities = Bremgarten bei Bern, Frauenkappelen, Ittigen, Kirchlindach, Köniz, Mühleberg, Muri bei Bern, Neuenegg, Ostermundigen, Wohlen bei Bern, Zollikofen

, website ...

, Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the West ...

, Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

, and the University of Wales

The University of Wales (Welsh language, Welsh: ''Prifysgol Cymru'') is a confederal university based in Cardiff, Wales. Founded by royal charter in 1893 as a federal university with three constituent colleges – Aberystwyth, Bangor and Cardiff � ...

.

Eponyms

;Liddell-Sherrington reflex: Associated with Edward George Tandy Liddell and Charles Scott Sherrington, the Liddell-Sherrington reflex is the tonic contraction of muscle in response to its being stretched. When a muscle lengthens beyond a certain point, the myotatic reflex causes it to tighten and attempt to shorten. This can be felt as tension during stretching exercises. ;Schiff-Sherrington reflex: Associated with Moritz Schiff and Charles Scott Sherrington, describes a grave sign in animals: rigid extension of the forelimbs after damage to the spine. It may be accompanied by paradoxical respiration – the intercostal muscles are paralysed and the chest is drawn passively in and out by the diaphragm. ;Sherrington's First Law: Every posterior spinal nerve root supplies a particular area of the skin, with a certain overlap of adjacent dermatomes. ;Sherrington's Second Law: The law of reciprocal innervation. When contraction of a muscle is stimulated, there is a simultaneous inhibition of its antagonist. It is essential for coordinated movement. ;Vulpian-Heidenhain-Sherrington phenomenon: Associated with Rudolf Peter Heinrich Heidenhain, Edmé Félix Alfred Vulpian, and Charles Scott Sherrington. Describes the slow contraction of denervated skeletal muscle by stimulating autonomic cholinergic fibres innervating its blood vessels.References

External links

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Sherrington, Charles Scott 1857 births 1952 deaths Academics of King's College London Alumni of Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge Alumni of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge British neuroscientists British Nobel laureates Fellows of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge Fellows of Magdalen College, Oxford Fullerian Professors of Physiology Members of the Order of Merit Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire Nobel laureates in Physiology or Medicine People educated at Ipswich School English pathologists Fellows of the Royal Society Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences Presidents of the Royal Society Royal Medal winners Recipients of the Copley Medal Waynflete Professors of Physiology English Nobel laureates Ipswich Town F.C. players English footballers The Journal of Physiology editors Association footballers not categorized by position