Shukri al-Quwatli on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Shukri al-Quwatli ( ar, شكري القوّتلي, Shukrī al-Quwwatlī; 6 May 189130 June 1967) was the first

The Quwatlis were a

The Quwatlis were a

On 1 October 1918, an

On 1 October 1918, an

As president, Quwatli continued to press for Syrian independence from France. In a bid to garner American and British support for his government, he declared war against the

As president, Quwatli continued to press for Syrian independence from France. In a bid to garner American and British support for his government, he declared war against the

Quwatli returned to Syria in 1955, following the ouster of President

Quwatli returned to Syria in 1955, following the ouster of President

Under Quwatli's leadership, Syria increasingly moved towards a neutralist policy amid the Cold War, despite the conservative views held by Quwatli. However, on 10 September, Quwatli first opted to make an official request for arms from the

Under Quwatli's leadership, Syria increasingly moved towards a neutralist policy amid the Cold War, despite the conservative views held by Quwatli. However, on 10 September, Quwatli first opted to make an official request for arms from the

Amid the euphoria generated by Egypt's military intervention, serious unity discussions commenced between Syria and Egypt. Towards the end of October, Anwar al-Sadat, the Egyptian speaker of parliament, visited the Syrian parliament in Damascus in a gesture of solidarity, only for the visit to end with the Syrian parliament voting unanimously to enter into a union with Egypt without delay. A Syrian delegation then headed for Cairo to persuade Nasser to accept unity with Syria, but Nasser expressed his reservations regarding unity to the delegates and Quwatli, who was in Damascus. Nasser was wary of the Syrian military's habitual interference in the country's political affairs and the stark difference in the countries' economies and political systems. The Syrian political and military leadership continued to press Nasser out of both sincere commitment to Arab nationalism and a realization that only unification with Egypt could prevent impending strife in the country due to increasing communist influence.

In December, the Ba'ath Party composed a proposal entailing federal unity with Egypt, prompting their communist rivals to propose a total union. While the communists were less eager to merge with Egypt, they sought to appear before the Syrian public as the group most dedicated to unity, privately believing Nasser would reject the offer as he had the first time. According to historian Adeed Dawisha, "the communists ended up outmaneuvering themselves ... unprepared for the unfolding events spearheaded by a public driven to frenzy by all talk and promises of union." On 11 January 1958, the communist chief-of-staff, Bizri, led an officers delegation to press for unity with Cairo without consulting Quwatli beforehand. Instead, the Egyptian ambassador,

Amid the euphoria generated by Egypt's military intervention, serious unity discussions commenced between Syria and Egypt. Towards the end of October, Anwar al-Sadat, the Egyptian speaker of parliament, visited the Syrian parliament in Damascus in a gesture of solidarity, only for the visit to end with the Syrian parliament voting unanimously to enter into a union with Egypt without delay. A Syrian delegation then headed for Cairo to persuade Nasser to accept unity with Syria, but Nasser expressed his reservations regarding unity to the delegates and Quwatli, who was in Damascus. Nasser was wary of the Syrian military's habitual interference in the country's political affairs and the stark difference in the countries' economies and political systems. The Syrian political and military leadership continued to press Nasser out of both sincere commitment to Arab nationalism and a realization that only unification with Egypt could prevent impending strife in the country due to increasing communist influence.

In December, the Ba'ath Party composed a proposal entailing federal unity with Egypt, prompting their communist rivals to propose a total union. While the communists were less eager to merge with Egypt, they sought to appear before the Syrian public as the group most dedicated to unity, privately believing Nasser would reject the offer as he had the first time. According to historian Adeed Dawisha, "the communists ended up outmaneuvering themselves ... unprepared for the unfolding events spearheaded by a public driven to frenzy by all talk and promises of union." On 11 January 1958, the communist chief-of-staff, Bizri, led an officers delegation to press for unity with Cairo without consulting Quwatli beforehand. Instead, the Egyptian ambassador,  To assert his influence over the unity talks, Quwatli sent Foreign Minister al-Bitar to Cairo on 16 January to join the discussions. Nasser, while still hesitant at the Syrian proposal and discouraged by members of his inner circle, became increasingly concerned with the communists' power in Syria as testified by Bizri's leadership and autonomy from Quwatli. He was further pressured by the Arab nationalist members of the delegation, including al-Bitar, who alluded to an impending communist takeover and urgently appealed to him not to "abandon" Syria.

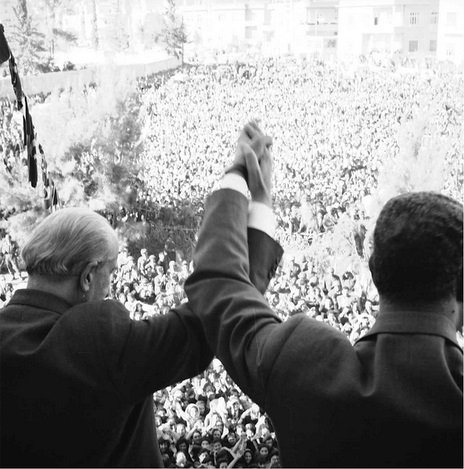

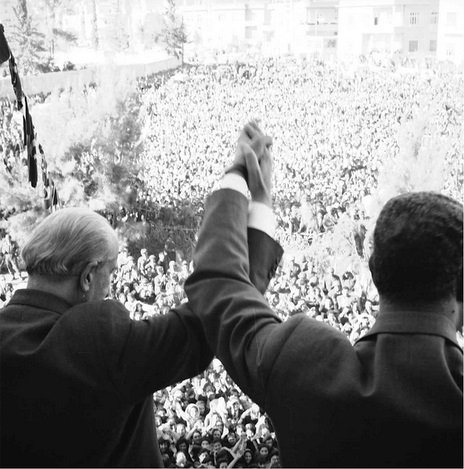

Nasser ultimately agreed to the union, but insisted that it be formed strictly on his terms, stipulating a one-party system, a merged economy, and Syria's adoption of Egyptian social institutions; in effect a full-blown union. Syria's political leaders, particularly the communists, the Ba'athists and the conservatives, viewed Nasser's terms unfavorably, but nonetheless accepted them in response to mounting popular pressure. Quwatli left for Cairo in mid-February to conclude the agreement with Nasser and on 22 February the

To assert his influence over the unity talks, Quwatli sent Foreign Minister al-Bitar to Cairo on 16 January to join the discussions. Nasser, while still hesitant at the Syrian proposal and discouraged by members of his inner circle, became increasingly concerned with the communists' power in Syria as testified by Bizri's leadership and autonomy from Quwatli. He was further pressured by the Arab nationalist members of the delegation, including al-Bitar, who alluded to an impending communist takeover and urgently appealed to him not to "abandon" Syria.

Nasser ultimately agreed to the union, but insisted that it be formed strictly on his terms, stipulating a one-party system, a merged economy, and Syria's adoption of Egyptian social institutions; in effect a full-blown union. Syria's political leaders, particularly the communists, the Ba'athists and the conservatives, viewed Nasser's terms unfavorably, but nonetheless accepted them in response to mounting popular pressure. Quwatli left for Cairo in mid-February to conclude the agreement with Nasser and on 22 February the

Quwatli had a heart attack shortly after the

Quwatli had a heart attack shortly after the

19. ''Arab News Agency''. 1967. According to Syrian historian Sami Moubayed, Quwatli died after learning of the defeat of the Syrian and Arab armies. The Ba'athist-dominated government refused to allow Quwatli's body to be buried in Damascus and only relented after diplomatic pressure from King

president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese f ...

of post-independence Syria. He began his career as a dissident

A dissident is a person who actively challenges an established political or religious system, doctrine, belief, policy, or institution. In a religious context, the word has been used since the 18th century, and in the political sense since the 20th ...

working towards the independence and unity of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

's Arab territories and was consequently imprisoned and tortured for his activism. When the Kingdom of Syria was established, Quwatli became a government official, though he was disillusioned with monarchism

Monarchism is the advocacy of the system of monarchy or monarchical rule. A monarchist is an individual who supports this form of government independently of any specific monarch, whereas one who supports a particular monarch is a royalist ...

and co-founded the republican Independence Party. Quwatli was immediately sentenced to death by the French who took control over Syria in 1920. Afterward, he based himself in Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo met ...

where he served as the chief ambassador of the Syrian-Palestinian Congress, cultivating particularly strong ties with Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in Western Asia. It covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries by area, fifth-largest country in Asia ...

. He used these connections to help finance the Great Syrian Revolt

The Great Syrian Revolt ( ar, الثورة السورية الكبرى) or Revolt of 1925 was a general uprising across the State of Syria and Greater Lebanon during the period of 1925 to 1927. The leading rebel forces comprised fighters of th ...

(1925–1927). In 1930, the French authorities pardoned Quwatli and thereafter, he returned to Syria, where he gradually became a principal leader of the National Bloc. He was elected president of Syria in 1943 and oversaw the country's independence three years later.

Quwatli was reelected in 1948, but was toppled in a military coup in 1949 by Husni al-Za'im. He subsequently went into exile in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Med ...

, returning to Syria in 1955 to participate in the presidential election, which he won. A conservative presiding over an increasingly leftist-dominated government, Quwatli officially adopted neutralism amid the Cold War. After his request for aid from the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

was denied, he drew closer to the Eastern bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

. He also entered Syria into a defense arrangement with Egypt and Saudi Arabia to confront the influence of the Baghdad Pact. In 1957, Quwatli, who the US and the Pact countries attempted but failed to oust, sought to stem the leftist tide in Syria, but to no avail. By then, his political authority had receded as the military bypassed Quwatli's jurisdiction by independently coordinating with Quwatli's erstwhile ally, Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein, . (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian politician who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 and introduced far-r ...

.

Following months of unity talks, in 1958, Quwatli merged Syria with Egypt to form the United Arab Republic

The United Arab Republic (UAR; ar, الجمهورية العربية المتحدة, al-Jumhūrīyah al-'Arabīyah al-Muttaḥidah) was a sovereign state in the Middle East from 1958 until 1971. It was initially a political union between Eg ...

and stepped down for Nasser to serve as president. In gratitude, Nasser awarded Quwatli the honorary title of "First Arab Citizen". However, Quwatli grew disenchanted with the union, believing it had reduced Syria to a police state

A police state describes a state where its government institutions exercise an extreme level of control over civil society and liberties. There is typically little or no distinction between the law and the exercise of political power by the ...

subordinate to Egypt. He backed Syria's secession in 1961, but plans for him to complete his presidential term afterward did not materialize. Quwatli left Syria following the 1963 Ba'athist coup, and he died of a heart attack in Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to Lebanon–Syria border, the north and east and Israel to Blue ...

weeks after Syria's defeat in the 1967 Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states (primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, S ...

. He was buried in Damascus on 1 July.

Personal life

Family

The Quwatlis were a

The Quwatlis were a Sunni Muslim

Sunni Islam () is the largest branch of Islam, followed by 85–90% of the world's Muslims. Its name comes from the word ''Sunnah'', referring to the tradition of Muhammad. The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a disagr ...

mercantile family from Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesipho ...

which moved to Damascus in the 18th century, establishing itself in the district of al-Shaghour. Their initial wealth in Damascus stemmed from trade with Baghdad and Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plate. ...

. After 1860 the family invested part of its wealth in large land tracts in the Ghouta

Ghouta ( ar, غُوطَةُ دِمَشْقَ / ALA-LC: ''Ḡūṭat Dimašq'') is a countryside and suburban area in southwestern Syria that surrounds the city of Damascus along its eastern and southern rim.

Name

Ghouta is the Arabic term (' ...

farms surrounding Damascus. The first member of the family to own extensive tracts was Shukri's granduncle Murad (d. 1908). The family's notable status was owed to their wealth, rather than an aristocratic or religious lineage, and their traditional spheres of activity were commerce and the Ottoman civil service.

Shukri's grandfather Abd al-Ghani was involved in finance, as was his granduncle Ahmad, who was appointed the president of the Agricultural Bank of Damascus in 1894, and another granduncle, Hasan, president of the Chamber of Agriculture and Commerce, while Murad had become a member of the Administrative Council of the city in 1871 and was re-elected in the early 1890s. Shukri's father's wealth rested on the highly fertile lands he owned and later bequeathed to Shukri and his siblings in the Ghouta. His elder brother Hasan was elected President of the Damascus Chamber of Commerce and Agriculture. Despite the substantial wealth accrued toward the end of the 19th century, the family remained in the working class al-Shaghur and developed networks there which contributed to its future political ambitions.

In 1928, Shukri married Bahira al-Dalati, the 19-year-old daughter of nationalist Said al-Dalati, whom Quwatli met while in jail in 1916. Shukri and Bahira had five children; Hassan (the oldest, born in 1935), Mahmud, Huda, Hana and Hala. Bahira al-Dalati died in 1989.

Childhood and education

Shukri Quwatli was born in Damascus in 1891. He received his elementary education at a Jesuit school in the city, then studied at the preparatory high school of Maktab Anbar in the Jewish quarter of Damascus. He obtained hisbaccalauréat

The ''baccalauréat'' (; ), often known in France colloquially as the ''bac'', is a French national academic qualification that students can obtain at the completion of their secondary education (at the end of the ''lycée'') by meeting certain ...

in 1908. He then moved to Istanbul

Istanbul ( , ; tr, İstanbul ), formerly known as Constantinople ( grc-gre, Κωνσταντινούπολις; la, Constantinopolis), is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, serving as the country's economic, ...

where he studied political science and public administration. Quwatli graduated from the Mekteb-i Mülkiye

The Faculty of Political Science of the University of Ankara ( tr, Ankara Üniversitesi Siyasal Bilgiler Fakültesi, more simply known as "''SBF''") is the oldest faculty of social science in Turkey, being the successor of the "Mekteb-i Mülkiye" ( ...

in 1913. He returned to Damascus in 1913 after receiving his diploma, and started working for the Ottoman civil service.

Early influences

Quwatli was initially brought up in a pro-Ottoman environment, owing to his family's connections in Istanbul. The restrictions of theAbdul Hamid II

Abdülhamid or Abdul Hamid II ( ota, عبد الحميد ثانی, Abd ül-Hamid-i Sani; tr, II. Abdülhamid; 21 September 1842 10 February 1918) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 31 August 1876 to 27 April 1909, and the last sultan to ...

era, however, started to be felt around the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, and discontent was brewing even among the empire's elite. Following the Young Turk Revolution

The Young Turk Revolution (July 1908) was a constitutionalist revolution in the Ottoman Empire. The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), an organization of the Young Turks movement, forced Sultan Abdul Hamid II to restore the Ottoman Constit ...

against Abdul Hamid II in 1908, parliamentary elections

A general election is a political voting election where generally all or most members of a given political body are chosen. These are usually held for a nation, state, or territory's primary legislative body, and are different from by-elections ...

were called in all provinces, and liberal Arab intellectuals like Shukri al-Asali

Shukri al-Asali ( ar, شكري العسلي, Shukrī al-ʿAsalī; 1868 – May 6, 1916) was a prominent Syrian politician, nationalist leader, and senior inspector in the Ottoman government, in addition to being a ranking member of the Council of ...

, Shafiq Muayyad al-Azm, and Rushdi al-Shama'a secured seats as deputies (members of the legislature) representing Damascus. The liberal current that established itself through these figures, and the political dailies they established including ''al-Qabas'' ("The Firebrand") and ''al-Ikha' al-Arabi'' ("Arab Brotherhood"), greatly influenced Quwatli and other Arab youths.

During the 31 March Incident, Quwatli strongly supported the Committee of Union and Progress

The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) ( ota, اتحاد و ترقى جمعيتی, translit=İttihad ve Terakki Cemiyeti, script=Arab), later the Union and Progress Party ( ota, اتحاد و ترقى فرقهسی, translit=İttihad ve Tera ...

(CUP) against Abdul Hamid II. Nevertheless, after the failed countercoup, the CUP accused Arab provinces of supporting Abdul Hamid II and initiated a policy of Turkification, whereby all local officials were substituted by Turkish ones. Soon after, the parliament was dissolved, and the liberal Arab politicians were forced out in the following elections.

Early nationalist activities

Quwatli's early involvement in the Arab nationalist movement came through the Arab Congress of 1913. Shortly after starting his career at the Ottoman civil service in Damascus, he received an invitation to attend the conference inParis

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. ...

. However, the conference was strongly condemned by the Ottoman authorities, and Arab notables were forbidden from attending. Nevertheless, the congress had succeeded in rousing nationalist feelings in Arab provinces. Quwatli's first confrontation with the Ottoman authorities came in February 1914 during a visit by Jamal Pasha

Ahmed Djemal ( ota, احمد جمال پاشا, Ahmet Cemâl Paşa; 6 May 1872 – 21 July 1922), also known as Cemal Pasha, was an Ottoman military leader and one of the Three Pashas that ruled the Ottoman Empire during World War I.

Djemal w ...

, the governor of Syria at the time, to the offices of the Governorate of Damascus, where Quwatli worked. During the visit, Quwatli refused to follow the normal protocol—bending over and kissing Jamal Pasha's right hand—and was promptly thrown in prison at the Citadel of Damascus

The Citadel of Damascus ( ar, قلعة دمشق, Qalʿat Dimašq) is a large medieval fortified palace and citadel in Damascus, Syria. It is part of the Ancient City of Damascus, which was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1979.

The ...

. He was bailed out of prison a few days later through his family's connections, but he lost his job at the civil service.

Al-Fatat

The growing hardships in the country during the early years ofWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

pushed Quwatli to join the secret society of al-Fatat, which was facilitated by his childhood friend and co-founder, Nasib al-Bakri

Nasib al-Bakri ( ar, نسيب البكري; 1888–1966) was a Syrian politician and nationalist leader in the first half of the 20th century. He played a major role in establishing al-Fatat, an underground organization which sought the indepen ...

. Al-Fatat was an underground organization established in Paris in 1911 by Arab nationalists with the aim of gaining independence and unity of the various Arab territories in the Ottoman Empire. In 1913, the society established its main branch in Damascus, and was successful in attracting the Syrian elite into its ranks.

In 1915, Sharif Hussein, trying to garner support for his planned uprising against the Ottomans, sent his son Faisal

Faisal, Faisel, Fayçal or Faysal ( ar, فيصل) is an Arabic given name.

Faisal, Fayçal or Faysal may also refer to:

People

* King Faisal (disambiguation)

** Faisal I of Iraq and Syria (1885–1933), leader during the Arab Revolt

** Faisal ...

to Damascus to lobby the Syrian notables on his behalf. Faisal, a member of al-Fatat himself, met secretly with other members of the society, including Quwatli, in the house of Nasib al-Bakri. When the Ottoman authorities learned of the meeting, they ordered the arrest of al-Bakri and his two brothers, Fawzi and Sami, accusing them of treason. Quwatli was charged by the al-Fatat leadership with the task of facilitating their escape, in which he succeeded. In retaliation, Ottoman authorities placed him under arrest, in which he was subjected to torture and humiliation. Nevertheless, Quwatli refused to confess to anything, and his captors failed to implicate him in the operation so they released him a month later. The tremendous pressure of that experience, however, took its toll on the young Quwatli, and upon his release he retired to his country house in Saidnaya

Saidnaya (also transliterated Saydnaya, Seidnaya or Sednaya, from the syr, ܣܝܕܢܝܐ, ar, صيدنايا, Ṣaydnāyā) is a city located in the mountains, above sea level, north of the city of Damascus in Syria. It is the home of a Gree ...

and stopped all contacts with members of al-Fatat and the opposition.

In late 1916 he was approached by Fasih al-Ayyubi in hope that Quwatli could help him secure an escape route for his ailing father, Shukri al-Ayyubi, who was arrested by the Ottomans, like he did for Nasib al-Bakri. However, despite Quwatli's refusal to help, Ottoman authorities tracked down the contact and arrested both men. Quwatli was subjected to further torture to coerce him to reveal the names of his al-Fatat colleagues. In an attempt to prevent himself from surrendering the names, Quwatli tried to commit suicide. After cutting his wrists, Quwatli's life was saved at the last minute by fellow inmate, al-Fatat member and practicing doctor, Ahmad Qadri

Ahmad ( ar, أحمد, ʾAḥmad) is an Arabic male given name common in most parts of the Muslim world. Other spellings of the name include Ahmed and Ahmet.

Etymology

The word derives from the root (ḥ-m-d), from the Arabic (), from the ve ...

. He spent four more months in jail, before being released on bail by his relative, Shafiq al-Quwatli, who served as a deputy at the Ottoman Parliament, on 28 January 1917. His experience in jail and the story about his attempted suicide turned Quwatli into a nationalist hero in Syria.

Kingdom of Syria

On 1 October 1918, an

On 1 October 1918, an Arab army

The Sharifian Army ( ar, الجيش الشريفي, links=yes), also known as the Arab Army ( ar, الجيش العربي, links=yes), or the Hejazi Army ( ar, الجيش الحجازي, links=yes) was the military force behind the Arab Revolt w ...

under the leadership of Emir Faisal and British general T. E. Lawrence entered Damascus, and by the end of October the rest of Ottoman Syria fell to the Allied Forces. Emir Faisal became in charge of administering the liberated territory. He appointed Rida al-Rikabi as prime minister, and Quwatli's friend, Nasib al-Bakri became a personal adviser to the Emir. Quwatli, at the age of twenty-six, was appointed assistant to the governor of Damascus, Alaa al-Din al-Durubi Ala, ALA, Alaa or Alae may refer to:

Places

* Ala, Hiiu County, Estonia, a village

* Ala, Valga County, Estonia, a village

* Ala, Alappuzha, Kerala, India, a village

* Ala, Iran, a village in Semnan Province

* Ala, Gotland, Sweden

* Alad, Seydu ...

.

However, many of Quwatli's generation were unimpressed with Faisal's leadership skills, and were drawn to a republican, rather than monarchist, view of governance. Furthermore, they were suspicious of Faisal, and his brother Abdullah's ties with the British. On 15 April 1919 they founded a loose coalition under the name of al-Istiqlal Party ("Independence Party"). The party had a pan-Arab, secular, anti-British and anti-Hashemite outlook and attracted mostly youth activists from the elite classes. Well-known members, other than Quwatli, included Adil Arslan, Nabih al-Azmeh, Riad al-Sulh, Saadallah al-Jabiri

Saadallah Al Jabiri ( ar, سعد الله الجابري; 1893–1947) was a Syrian Arab politician, a two-time prime minister and a two-time Minister of Foreign Affairs and Expatriates of Syria.

Jabiri was exiled by the French authorities to ...

, Ahmad Qadri, Izzat Darwaza and Awni Abd al-Hadi. Although ostensibly working for the government, Quwatli devoted his efforts to nationalist activities outside the government's auspices. In addition to al-Istiqlal, he was also a member of the Palestinian-led Arab Club's Damascus branch.

In a meeting with the 1919 King–Crane Commission

The King–Crane Commission, officially called the 1919 Inter-Allied Commission on Mandates in Turkey, was a commission of inquiry concerning the disposition of areas within the former Ottoman Empire.

The Commission began as an outgrowth of the ...

, sent by the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

(US) to gauge national sentiment in greater Syria

Syria ( Hieroglyphic Luwian: 𔒂𔒠 ''Sura/i''; gr, Συρία) or Sham ( ar, ٱلشَّام, ash-Shām) is the name of a historical region located east of the Mediterranean Sea in Western Asia, broadly synonymous with the Levant. Other ...

, Quwatli rejected the notion of an American military presence in Syria, telling Crane that "Reduction of sovereignty is non-negotiable" and instead suggesting that the US help Syrians to "build their state and live in peace on their land." Nevertheless, French forces had already started landing on the Syrian coast in 1919 to enforce the Sykes–Picot Agreement

The Sykes–Picot Agreement () was a 1916 secret treaty between the United Kingdom and France, with assent from the Russian Empire and the Kingdom of Italy, to define their mutually agreed Sphere of influence, spheres of influence and control in a ...

whereby France and the UK would divide up the former Arab territories of the Ottoman Empire between themselves. In March 1920, the League of Nations granted France a mandate over Syria and Lebanon, and in response Emir Faisal declared himself king of Syria on 8 March 1920. When King Faisal refused to accept the mandate, the French marched on Damascus. Yusuf al-'Azma, minister of defense at the time, led a small force and met the French at the Battle of Maysalun on 23 July 1920. The battle ended in a decisive victory for the French, and the next day French forces occupied Damascus. King Faisal was deported to Europe, and the French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon was officially declared.

Leader in Syrian independence movement

Emissary of the Syrian-Palestinian Congress

The French started their rule by sentencing 21 nationalist leaders, including Quwatli, to death on 1 August 1920. Quwatli managed to flee only hours before a warrant for his arrest was issued. From Damascus he fled by car toHaifa

Haifa ( he, חֵיפָה ' ; ar, حَيْفَا ') is the third-largest city in Israel—after Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—with a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropoli ...

in British-mandated Palestine, and soon after to Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo met ...

in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Med ...

. From there, Quwatli spent the bulk of his time traveling throughout the Arab world

The Arab world ( ar, اَلْعَالَمُ الْعَرَبِيُّ '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, refers to a vast group of countries, mainly located in Western A ...

and Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located enti ...

serving as the virtual ambassador of the Syrian-Palestinian Congress. He became the chief link between Arab nationalist activists in Europe and in the Arab world.

In Europe, he particularly frequented Berlin

Berlin is Capital of Germany, the capital and largest city of Germany, both by area and List of cities in Germany by population, by population. Its more than 3.85 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European U ...

where he worked with the prominent Arab nationalist intellectual Shakib Arslan to proliferate anti-French sentiment, leading the French Mandatory authorities to label Quwatli one of the "most dangerous" Syrian exiles. He developed close ties with Ibn Saud

Abdulaziz bin Abdul Rahman Al Saud ( ar, عبد العزيز بن عبد الرحمن آل سعود, ʿAbd al ʿAzīz bin ʿAbd ar Raḥman Āl Suʿūd; 15 January 1875Ibn Saud's birth year has been a source of debate. It is generally accepted ...

, who by 1925 ruled much of Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plate. ...

, having overrun the Hashemites in the Hejaz. Quwatli had a prior relationship with the House of Saud

The House of Saud ( ar, آل سُعُود, ʾĀl Suʿūd ) is the ruling royal family of Saudi Arabia. It is composed of the descendants of Muhammad bin Saud, founder of the Emirate of Diriyah, known as the First Saudi state (1727–1818), ...

, stemming from his own family's commercial links with the Saudis and Quwatli's friendship with Sheikh Yusuf Yasin, a Syrian adviser to Ibn Saud, who Quwatli had dispatched to Arabia during Faisal's rule. Quwatli, strongly distrustful of the Hashemites, was impressed by Ibn Saud's relatively quick conquest over much of Arabia and saw in the Saudis a strong potential ally against British and French colonial rule in the Middle East. By 1925, Quwatli had solidified his position as the intermediary between Ibn Saud and the Syrian-Palestinian Congress. His acquisition of Saudi funding put him at odds with the Congress's chief financier Michel Lutfallah, however.

Financing the Great Syrian Revolt

In the summer of 1925 tensions between theDruze

The Druze (; ar, دَرْزِيٌّ, ' or ', , ') are an Arabic-speaking esoteric ethnoreligious group from Western Asia who adhere to the Druze faith, an Abrahamic, monotheistic, syncretic, and ethnic religion based on the teachings o ...

chiefs of the Hauran

The Hauran ( ar, حَوْرَان, ''Ḥawrān''; also spelled ''Hawran'' or ''Houran'') is a region that spans parts of southern Syria and northern Jordan. It is bound in the north by the Ghouta oasis, eastwards by the al-Safa field, to the ...

led by Sultan Pasha al-Atrash and the French authorities culminated with the Great Syrian Revolt

The Great Syrian Revolt ( ar, الثورة السورية الكبرى) or Revolt of 1925 was a general uprising across the State of Syria and Greater Lebanon during the period of 1925 to 1927. The leading rebel forces comprised fighters of th ...

, which spread throughout Syria within months. While Quwatli's Istiqlal Party lobbied the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Amin al-Husseini

Mohammed Amin al-Husseini ( ar, محمد أمين الحسيني 1897

– 4 July 1974) was a Palestinian Arab nationalist and Muslim leader in Mandatory Palestine.

Al-Husseini was the scion of the al-Husayni family of Jerusalemite Arab nota ...

to set up a financial support network for the rebellion, Quwatli had already secured the funneling of funds and arms from the Hejaz and also diverted some of the military aid to the Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

-based committee. As the revolt's initial momentum began to recede in mid-1926, bickering between opposition leaders, inside and outside of Syria, increased significantly. Quwatli was accused by his rivals in Cairo of pocketing some money he raised and paying off rebels to prevent rebel raids against his family's extensive apricot orchards in the Ghouta

Ghouta ( ar, غُوطَةُ دِمَشْقَ / ALA-LC: ''Ḡūṭat Dimašq'') is a countryside and suburban area in southwestern Syria that surrounds the city of Damascus along its eastern and southern rim.

Name

Ghouta is the Arabic term (' ...

. Tensions between Istiqlalists like Quwatli and Arslan and other Syrian nationalist leaders like al-Bakri and Shahbandar, were particularly sharp, with the latter accusing Quwatli of being out of touch from the realities of the revolt, and Quwatli accusing Shahbandar of treason for attempting to stop the insurrection.

Role in the National Bloc

In late 1927, Quwatli headed the Istiqlal-dominated Executive Committee of the Syrian-Palestinian Congress, although Lutfallah headed a separate rival committee that also called itself the Congress's Executive Committee. Both were based in Cairo. Locally known then as the "apricot king", Quwatli used revenues from his agricultural lands to build up a network of support in the Old City of Damascus. In 1930, Quwatli was allowed to return to Syria under a generalamnesty

Amnesty (from the Ancient Greek ἀμνηστία, ''amnestia'', "forgetfulness, passing over") is defined as "A pardon extended by the government to a group or class of people, usually for a political offense; the act of a sovereign power offic ...

. Thereafter, he joined the National Bloc, the preeminent opposition movement in Syria—though tolerated by the French. Although he opposed the moderate stances of the Bloc's Damascene leaders, he determined he could only remain a major political player by joining the group. He sought to steer it towards a more determined nationalist course and worked to expand his support base, relying on his relationships with residents in some of Damascus' traditionally nationalist neighborhoods ( al-Midan and al-Shaghour) and among the city's merchant and emerging industrialist classes. He also worked to draw support from the staunch pan-Arabists of the League of National Action (LNA) beginning in 1933. He managed to co-opt much of the LNA's members by 1935–36 by financing its land development company (which aimed to prevent land sales to Zionist

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after '' Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in J ...

organizations in Palestine) and assigning some of its leaders to the director boards of companies affiliated with the Bloc.

In 1936, as a general strike

A general strike refers to a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large coa ...

was underway in the country to demand a renegotiation of the French role in Syria, Quwatli was appointed the Bloc's vice president of internal affairs, but was not part of the treaty negotiation committee which led talks with the French in Paris in March. A new treaty was established by the end of the month, although the French did not ratify it. Between then and fall, Quwatli spearheaded efforts to unify nationalists ranks in Syria, convincing LNA leader Sabri al-Asali

Sabri al-Asali ( ar, صبري العسلي; 1903 – 13 April 1976) was a Syrian politician and a three-time prime minister of Syria. He also served as vice-president of the United Arab Republic in 1958.

Early life

Al-Asali was born into a weal ...

to join the Bloc's highest governing body. By enlisting the support of many prominent pan-Arabists like himself, Quwatli strengthened his position within the Bloc, particularly in regards to his chief nationalist rival Jamil Mardam Bey. He was Minister of Finance from 1936 to 1938.

On 20 March 1941, during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, when the Vichy French

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its t ...

were in control of Syria, Quwatli called for immediate Syrian independence amid a period of food shortages, high unemployment and widespread nationalist rioting in the country. Vichy troops in the country were defeated by the Allied forces in July and Quwatli left Syria during the campaign. He returned in 1942. France officially recognized Syria's independence on 27 September. However, French troops were not withdrawn and national elections were postponed by the French Mandatory authorities.

First presidential term

Election of 1943

Prior to the 1943 national elections in French Mandatory Syria, the French authorities attempted to negotiate with Quwatli as head of the National Bloc to issue a treaty that guaranteed an independent Syria's alignment and close military cooperation with France, in return for French help in securing Quwatli's election to the presidency. Quwatli refused, believing the Syrian people would view such negotiations negatively. He was also confident that the National Bloc would win the elections regardless of French support. Quwatli did win the vote, becoming Syria's president on 17 August 1943.Syrian independence

As president, Quwatli continued to press for Syrian independence from France. In a bid to garner American and British support for his government, he declared war against the

As president, Quwatli continued to press for Syrian independence from France. In a bid to garner American and British support for his government, he declared war against the Axis Powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

, aligning Syria with the Allies. Growing countrywide unrest in response to French Mandatory rule led to French military assaults against Damascus and other Syrian cities in May 1945. More French troops were scheduled to land in Syria to aid the authorities, but at Quwatli's request for intervention, British troops invaded Syria from Transjordan, entering Damascus on 1 June. The French military campaign came to an immediate halt as a consequence; the UK and the US had viewed the French military action in Syria as a potential catalyst for further unrest throughout the Middle East and a detriment to British and American lines of communication in the region.

As French troops began a partial withdrawal from the country, Quwatli instructed Fares al-Khoury

Faris al-Khoury ( ar, فارس الخوري, Fāris al-Khūrī) (November 20, 1877 – January 2, 1962) was a Syrian statesman, minister, prime minister, speaker of parliament, and father of modern Syrian politics. Faris Khoury went on to become p ...

, his envoy to the US and head of the Syrian mission to the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmonizi ...

, to bring the issue of Syria's independence to the United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the Organs of the United Nations, six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international security, international peace and security, recommending the admi ...

(UNSC), cabling Khoury to "Go to S President Harry

S, or s, is the nineteenth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''ess'' (pronounced ), plural ''esses''.

History ...

Truman and tell him the French have ploughed the land in Syria, over our heads!" Khoury proceeded to petition the UNSC to force France's withdrawal from Syria. The US and UK backed Syria's request and informed Quwatli that British troops were in control of Syria, requesting Quwatli's cooperation in enforcing an evening curfew in the country. Quwatli complied and expressed his gratitude to the British government. At a summit between France, the UK, the US, Russia and China, France agreed to withdraw from both Syria and Lebanon in return for British promises to withdraw its military from the Levant

The Levant () is an approximation, approximate historical geography, historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology an ...

region as well. Quwatli was angered that Syria was left out of the conference and requested a summit with Truman and Winston Churchill, which was rebuffed.

The transfer of administrative powers to the Syrian government began on 1 August, the day in which Quwatli announced the establishment of the Syrian Army

" (''Guardians of the Homeland'')

, colors = * Service uniform: Khaki, Olive

* Combat uniform: Green, Black, Khaki

, anniversaries = August 1st

, equipment =

, equipment_label =

, battles = 1948 Arab–Israeli War

Six ...

and his position as the commander in chief. Quwatli also asked Khoury to form a cabinet, which was established on 24 August. The French completed their withdrawal from Syria on 15 April 1946 and Quwatli declared Syria's independence day on 17 April.

Post-independence politics

Following Syria's independence, the National Bloc was dissolved and replaced by the National Party. Quwatli's leadership, while supported by older politicians like Asali, Jabiri and Haffar, became increasingly challenged by emerging leaders such as Nazim al-Qudsi of the People's Party andAkram al-Hawrani

Akram Al-Hourani ( ar, أَكْرَم الْحَوْرَانِي, ʾAkram al-Ḥawrānī, also transcribed El-Hourani, Howrani or Hurani) (November 1911 – 24 February 1996), was a Syrian politician who played a prominent role during the democrat ...

of the Arab Socialist Party as well as the Baath Party, the Syrian Socialist Nationalist Party (SSNP), the Muslim Brotherhood

The Society of the Muslim Brothers ( ar, جماعة الإخوان المسلمين'' ''), better known as the Muslim Brotherhood ( ', is a transnational Sunni Islamist organization founded in Egypt by Islamic scholar and schoolteacher Hassa ...

and the Syrian Communist Party

The Syrian Communist Party ( ar, الحزب الشيوعي السوري, translit=al-Ḥizb aš-Šuyūʿī as-Sūrī) was a political party in Syria founded in 1924. It became a member of the National Progressive Front in 1972. The party spli ...

(SCP). Antagonistic relations between Quwatli and the Hashemite kings of Iraq and Jordan, Abdullah I and Faisal II, respectively, increased with the latter two seeking to unite Syria, Iraq and Jordan under Hashemite monarchical rule, and Quwatli countering that Iraq and Jordan join a republican Syria under his leadership instead. The Hashemites found support in the People's Party, which became an influential force in Aleppo, a major city and economic hub of Syria, particularly after the 1947 death of Jabiri, Quwatli's Aleppo-based ally.

In early 1947, Quwatli and the National Party, the largest party in parliament, made an amendment to the constitution to enable Quwatli to seek re-election. The move was met by strong disapproval from rival Syrian parties and opposition politicians, and a campaign to unseat Quwatli in the next presidential election was commenced. Quwatli's allies won 24 out of 127 seats during the 1947 parliamentary election, the first in post-independence Syria, while the opposition won 53 seats and independents unaffiliated with any political party won 50. A number of Quwatli's allies defected from the National Party and former president Atassi retired from politics because of his frustration at Quwatli's handling of Syrian internal affairs. Quwatli tasked Jamil Mardam Bey to form a new cabinet in October, which included mostly pro-Western politicians.

Despite the heavy presence of pro-American figures in the cabinet and Quwatli's initially warm ties with the US, relations between the two countries began to unravel amid the nascent Cold War and the view that Quwatli was becoming a detriment to US interests in the region. Quwatli developed close relations with the SCP and its head Khalid Bakdash, which was a contributing factor to the US Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washi ...

's rejection of Quwatli's arms request for the Syrian Army in late 1947. Quwatli also rejected the construction of the Trans-Arabian Pipeline in Syria (to connect the oilfields of Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in Western Asia. It covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries by area, fifth-largest country in Asia ...

to Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to Lebanon–Syria border, the north and east and Israel to Blue ...

). Quwatli feared construction of the pipeline would threaten the mostly British-owned Iraq Petroleum Company and upset the UK, as well as the Syrian public, who he believed would view the project "as a new form of indirect foreign economic control", according to Moubayed. US support for Israel, particularly under Truman, and Quwatli's adamant opposition to Zionism was a further source of tension.

Second presidential term

Election of 1948

With the constitution amended to allow for a president to seek more than one term, Quwatli ran againstKhalid al-Azm

Khalid al-Azm ( ar, خالد العظم, Khālid al-Aẓim; 11 June 1903 – 18 November 1965) was a Syrian national leader and five-time interim Prime Minister, as well as Acting President from 4 April to 16 September 1941. He was a member of ...

for another five-year term and won by a slim majority on 18 April 1948.

1948 Arab-Israeli War

Quwatli opposed the proposed partition of the British Mandate of Palestine into separate Jewish and Arab states, arguing that the plan, which would allocate 56% of Palestine to the Jewish state, violated the rights of the Palestinian Arab majority. The proposal passed the UN vote and Syria made war preparations soon afterward, including co-founding theArab Liberation Army

The Arab Liberation Army (ALA; ar, جيش الإنقاذ العربي ''Jaysh al-Inqadh al-Arabi''), also translated as Arab Salvation Army, was an army of volunteers from Arab countries led by Fawzi al-Qawuqji. It fought on the Arab side in th ...

(ALA). Quwatli had proposed the creation of the ALA as a volunteer force to attract fighters from throughout the Arab world and to take the place of Arab regular armies. The ALA's establishment was sponsored by the Arab League following the UN partition vote and Fawzi al-Qawuqji

Fawzi al-Qawuqji ( ar, فوزي القاوقجي; 19 January 1890 – 5 June 1977) was a leading Arab nationalist military figure in the interwar period.The Arabs and the Holocaust: The Arab-Israeli War of Narratives, by Gilbert Achcar, (NY: Hen ...

, a Syrian commander who played leading roles in the Great Syrian Revolt and the 1936 revolt in Palestine, was appointed its commander. Quwatli did not believe the armies of Syria and the Arab world were ready to successfully confront Jewish forces and as war drew near in early 1948, he petitioned Abdel Rahman Azzam, head of the Arab League, to not enter Arab armies into Palestine. Instead, Quwatli offered to provide local Palestinian Arab fighters arms and funding. Azzam was not swayed and continued his effort of rallying Arab governments to dispatch their armies. On 15 May, after the establishment of Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

was announced, Quwatli ordered the Syrian Army to enter Palestine immediately.

The Syrian Army, which consisted of 4,500 soldiers, had been mostly repelled in their offensive during the first few days of the war, gaining control over a small area along the Syrian border. As a result of the army's poor showing, Quwatli pressed defense minister Ahmad al-Sharabati Ahmad al-Sharabati ( ar, أحمد الشرباتي; 1909 – 1975) was a Syrian politician and the defense minister of Syria between 1946 and 1948, serving in the post as Syria gained its independence from France and during the early days of the 194 ...

to resign his post, which Sharabati did on 24 May. He then replaced chief of staff Abdullah Atfeh

Abdullah Atfeh ( ar, عبدالله عطفة; 1897–1976) was a Syrian career military officer who served as the first chief of staff of the Syrian Army after the country's independence.

Career

Early career

Abdullah Atfeh began his military c ...

with Husni al-Zaim during that same period of the war. Following the war, Quwatli accused Zaim of military incompetence and his officers of profiteering. In turn, Zaim accused Quwatli of mismanagement during the conflict. The Syrian public did not spare Quwatli blame for the army's poor performance, causing his popularity, built on his nationalist reputation, to erode further. The Syrian press was also sharply critical of Quwatli and Prime Minister Mardam Bey, urging them to leave their positions. Mardam Bey resigned on 22 August 1948 and was replaced by Khalid al-Azm.

Mass demonstrations took place in Syria condemning US President Harry Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Frankli ...

for recognizing Israel. Synagogues were attacked in Damascus as were the offices of General Motors. US officials were frustrated at Quwatli for not attempting to stop the demonstrations. When Egypt, Jordan and Lebanon signed armistice agreements with Israel between February and April 1949, Syria under Quwatli did not do so and refused to send a delegation to attend truce negotiations in Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

in March.

Coup d'état of 1949

On 29 March 1949, Zaim launched acoup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, ...

, overthrowing Quwatli. Zaim's troops entered Damascus and raided Quwatli's home. They disarmed his guard and confronted Quwatli in his night clothes before army officer Ibrahim al-Husseini arrested him. After being allowed to change his clothes, Quwatli was taken by the authorities to the city's Mezzeh Prison. Prime Minister al-Azm was also arrested. The coup had been backed and allegedly co-planned with the US Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian intelligence agency, foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gat ...

. The US was the first country to recognize Zaim's government, followed by the UK, France, and the Hashemite kingdoms of Iraq and Jordan. Quwatli's mother died of a heart attack about a week after his overthrow.

Exile in Egypt

As a result of pressure from the Egyptian and Saudi governments to spare the life of their ally Quwatli, al-Zaim agreed to release Quwatli from prison in mid-April 1949. After officially resigning as President, Quwatli was exiled toAlexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandr ...

, Egypt. In Egypt he was respected as a guest of honor by King Farouk and after the July 1952 revolution, by the Free Officers who gained power. Despite his positive relationship with the ousted King Farouk, Quwatli developed a close friendship with the founder of the Free Officers, Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein, . (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian politician who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 and introduced far-r ...

, who became Egypt's leader in 1954.

Third presidential term

Elections of 1955

Quwatli returned to Syria in 1955, following the ouster of President

Quwatli returned to Syria in 1955, following the ouster of President Adib al-Shishakli

Adib al-Shishakli (1909 – 27 September 1964 ar, أديب الشيشكلي, ʾAdīb aš-Šīšaklī) was a Syrian military leader and President of Syria from 1953 to 1954.

Early life

Adib Shishakli was born (1909) in the Hama Sanjak of Ott ...

and during the presidency of Hashim al-Atassi. Quwatli entered his candidacy in the August 1955 presidential elections, at the age of 63. Required to secure a two-thirds majority in the 142-member Syrian Parliament

The People's Assembly ( ar, مَجْلِس الشَّعْب, ) is Syria's legislative authority. It has 250 members elected for a four-year term in 15 multi-seat constituencies. There are two main political fronts; the National Progressive Fro ...

in order to win, Quwatli defeated his main opponent Khalid al-Azm 89 to 42 (a further six votes were cast as invalid) in the first round. This prompted a second round of voting, in which Quwatli won the presidency with 91 votes against Azm's 41 (a further five votes were blank and two invalid.) Quwatli's bid for the presidency was supported by the governments of Egypt and Saudi Arabia, both of which were allied in their opposition to the Baghdad Pact as was Quwatli.

Prime Minister Sabri al-Asali

Sabri al-Asali ( ar, صبري العسلي; 1903 – 13 April 1976) was a Syrian politician and a three-time prime minister of Syria. He also served as vice-president of the United Arab Republic in 1958.

Early life

Al-Asali was born into a weal ...

resigned from his post on 6 September following the Ba'ath Party

The Arab Socialist Baʿath Party ( ar, حزب البعث العربي الاشتراكي ' ) was a political party founded in Syria by Mishel ʿAflaq, Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn al-Bītār, and associates of Zaki al-ʾArsūzī. The party espoused ...

's withdrawal from the cabinet. As a result, Quwatli attempted to nominate Lutfi al-Haffar

Lutfi al-Haffar ( ar, لطفي الحفار) (18 February 1885 – 4 February 1968) was a Syrian businessman and politician. He was a founding member of the National Bloc and served as 11th Prime Minister of Syria in 1939.

Early career

Al-Haffar ...

as Prime Minister, but reneged after opposition from the Ba'athists. Afterward, Quwatli asked Rushdi al-Kikhiya

Rushdi ( ar, رشدي, ) is a masculine Arabic given name, it may refer to:

Given name

*Rushdy Abaza, Egyptian actor

* Rushdi Said, Egyptian geologist

*Rushdi al-Shawa, Palestinian politician

* Ruzhdi Kerimov, Bulgarian footballer

Surname and fa ...

to form a cabinet, but the latter refused, citing that influence from the Syrian Army

" (''Guardians of the Homeland'')

, colors = * Service uniform: Khaki, Olive

* Combat uniform: Green, Black, Khaki

, anniversaries = August 1st

, equipment =

, equipment_label =

, battles = 1948 Arab–Israeli War

Six ...

would deprive his government of real power. President Nasser of Egypt recommended the reappointment of Asali, but Quwatli refused, instead opting for Said al-Ghazzi

Said Al-Ghazzi ( ar, سعيد الغزي; 11 June 1893 – 18 September 1967) was a Syrian lawyer, politician and two time prime minister of Syria. He was born in Damascus.

Early life

Said belonged to the prominent al-Ghazzi family, wh ...

, an independent. Ghazzi agreed and subsequently presided over a national unity government.

Adoption of neutralism

Under Quwatli's leadership, Syria increasingly moved towards a neutralist policy amid the Cold War, despite the conservative views held by Quwatli. However, on 10 September, Quwatli first opted to make an official request for arms from the

Under Quwatli's leadership, Syria increasingly moved towards a neutralist policy amid the Cold War, despite the conservative views held by Quwatli. However, on 10 September, Quwatli first opted to make an official request for arms from the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

, but was eventually rebuffed despite support from US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles

John Foster Dulles (, ; February 25, 1888 – May 24, 1959) was an American diplomat, lawyer, and Republican Party politician. He served as United States Secretary of State under President Dwight D. Eisenhower from 1953 to 1959 and was briefly ...

. Starting in 1956, Quwatli began to look towards the Eastern bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

for economic and military assistance. During the tenure of his administration, Quwatli furthered Syria's relations with other neutralist countries such as Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label= Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavij ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India ( Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the ...

and Egypt, but also with the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

(USSR) and the Eastern bloc. The pursuit of this policy was partially due to the support afforded to the leftist movements in Syria by the Saudi and Egyptian governments who viewed them as strong opponents of the Baghdad Pact, and the highly influential leftist factions of the Syrian Army. Quwatli and Nasser initiated the Egyptian-Syrian Agreement, a defense arrangement that would serve as a counterweight to the Baghdad Pact, in March 1955. The agreement stipulated that each country would assist the other in case of an attack, the establishment of numerous committees to coordinate joint military activities and the creation of a joint military command headed by Egyptian officer Abdel Hakim Amer

Mohamed Abdel Hakim Amer ( arz, محمد عبد الحكيم عامر, ; 11 December 1919 – 13 September 1967) was an Egyptian military officer and politician. Amer served in the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, and played a leading role in the m ...

. The agreement was concluded 20 October.

Increasingly concerned at the growing leftist trend in the country, Quwatli called for a national unity government that would include parties from across the political spectrum on 15 February 1956. Despite opposition from the Ba'athists, Quwatli managed to preside over a "national covenant" which entailed a foreign policy of opposition to Zionism

Anti-Zionism is opposition to Zionism. Although anti-Zionism is a heterogeneous phenomenon, all its proponents agree that the creation of the modern State of Israel, and the movement to create a sovereign Jewish state in the region of Palestine ...

and imperialism

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power ( economic and ...

as well as the adoption of neutralism amid the Cold War. Nonetheless, and against Quwatli's advice, Ghazzi resigned from his post in June 1956 as a result of pressure from the Ba'athists and the communists

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a ...

who had been leading protests against Ghazzi's decision to lift the ban on wheat sales to Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

. Faced with few options, Quwatli reappointed Asali as Prime Minister. Asali moved to further strengthen ties with Egypt, including a pledge to start unity talks, and appointed Ba'athists to the ministerial positions of economy and foreign affairs.

Following the tripartite invasion of the Sinai Peninsula

The Sinai Peninsula, or simply Sinai (now usually ) (, , cop, Ⲥⲓⲛⲁ), is a peninsula in Egypt, and the only part of the country located in Asia. It is between the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Red Sea to the south, and is a ...

and the Suez Canal by British, French and Israeli forces in October 1956, Quwatli severed ties with Britain. Quwatli sent hundreds of army recruits to aid the Egyptian defense and made an emergency visit to Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

to request Soviet backing for Nasser from Premier Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev ...

, telling the latter that the tripartite forces "want to destroy Egypt!" In response to public pressure, in late December Prime Minister Asali reshuffled his cabinet, removing several fellow conservatives and strengthening leftist influence in the government.

Confronting leftist influence

In July 1957, relations between Quwatli's ally Saudi Arabia and the governments ofIraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

and Jordan, rivals of Syria, warmed considerably to the protestations of the leftist current in Syria, which viewed the growing ties between the region's conservative monarchies with distress. After a series of public criticisms of King Saud by an array of Syrian political figures, including al-Azm, Michel Aflaq

Michel Aflaq ( ar, ميشيل عفلق, Mīšīl ʿAflaq, , 9 January 1910 – 23 June 1989) was a Syrian philosopher, sociology, sociologist and Arab nationalism, Arab nationalist. His ideas played a significant role in the development o ...

and Akram al-Hawrani

Akram Al-Hourani ( ar, أَكْرَم الْحَوْرَانِي, ʾAkram al-Ḥawrānī, also transcribed El-Hourani, Howrani or Hurani) (November 1911 – 24 February 1996), was a Syrian politician who played a prominent role during the democrat ...

, Saud froze Syrian assets in Saudi Arabia and withdrew his ambassador from Syria in protest. In response to the crisis between the two countries, an alarmed Quwatli ordered Asali to publicly distance his government from the anti-Saudi views of some in the Syrian Parliament and press, and to publicly apologize to Saud. In addition, Quwatli personally issued a government order to shut down the communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a ...

newspaper ''Al Sarkha''.

On 6 August, Quwatli established a long-term agreement with the USSR, entailing a long-term Soviet loan to fund development works in Syria and the Soviet purchase of a large portion of Syrian agricultural and textile surpluses. US fears that Syria was approaching a communist takeover had prompted an attempted CIA-sponsored coup to replace the Quwatli government with former president Shishakli. However, the coup plot was foiled by the head of Syrian intelligence, Abdel Hamid al-Sarraj, on 12 August and Syria consequently expelled the US military attaché from Damascus. The US, which denied the coup plot, responded by expelling the Syrian ambassador from Washington and recalling its ambassador from Syria.

Leftist influence in Syria grew further in the immediate wake of the crisis; on 15 August, a high-ranking officer from Sidon

Sidon ( ; he, צִידוֹן, ''Ṣīḏōn'') known locally as Sayda or Saida ( ar, صيدا ''Ṣaydā''), is the third-largest city in Lebanon. It is located in the South Governorate, of which it is the capital, on the Mediterranean coast ...

, Lebanon with Marxist leanings, Afif Bizri

Afif al-Bizri ( ar, عفيف البزري) (1914 – 28 January 1994) was a Syrian career military officer who served as the chief of staff of the Syrian Army between 1957–1959. He was known for his communist sympathies, and for spearheading the ...

, was appointed army chief of staff, and several mid-level officers were replaced with communist officers. Quwatli flew to Egypt amid apparent plans to resign from the presidency in favor of the Soviet-leaning Azm. However, he returned to Syria on 26 August. Tensions had been rising as rumors swept the region regarding a US-backed Turkish or joint Iraqi-Jordanian invasion of Syria to prevent a potential communist takeover. Quwatli's earlier success in repairing ties between Syria and Saudi Arabia proved particularly useful during this period. Saud immediately lent his full support to Quwatli, whom he viewed as a significant counterweight to the leftist movement, by rebuffing President Dwight D. Eisenhower's appeal to endorse the Eisenhower Doctrine, a policy aimed at containing communist and Arab nationalist influence in the Middle East. He also accepted an invitation to Damascus by Quwatli on 25 August, publicly stating that Saudi Arabia would support Syria in any aggression against it. Iraqi Prime Minister Ali Jawdat also proclaimed support for Syria when he visited on 26 August, in spite of support for an attack by the Iraqi monarchy. Both Saud and Jawdat privately criticized Syria's leadership for increasing dependence on the Eastern bloc.

Nonetheless, the US and its allies in the Baghdad Pact genuinely feared that Syria was becoming a satellite of the Soviets and decided in a September meeting that Quwatli's government had to be removed. That same month Turkish troops massed along the border with Syria. On 13 October, Nasser, who had launched a radio campaign denouncing the Baghdad Pact countries, dispatched 1,500 Egyptian troops, a mostly symbolic force, to the port of Latakia

, coordinates =

, elevation_footnotes =

, elevation_m = 11

, elevation_ft =

, postal_code_type =

, postal_code =

, area_code = Country code: 963 City code: 41

, geocode ...

in northern Syria in a show of Arab strength against Turkey, to the acclaim of the Syrian and pan-Arab public. The leaders of Jordan and Iraq promptly reassured Quwatli that they had no intention to interfere in Syria's internal affairs. Nasser had apparently bypassed his ally Quwatli, coordinating the deployment with officers Sarraj and Bizri instead. Quwatli related this fact to Saud, who had complained of not being consulted of the Egyptian move beforehand, an "admission ... of Quwatli's political irrelevance," according to contemporary historian Salim Yaqub.

Sarraj and Bizri wielded substantial influence in Syrian politics, checking the power of the political factions and purging Nasser's opponents from the officer corps. This was a source of concern for Quwatli, but he kept both men in their posts, partially due to pressure from Nasser. Quwatli further solidified his ties with the latter by appointing Akram al-Hawrani

Akram Al-Hourani ( ar, أَكْرَم الْحَوْرَانِي, ʾAkram al-Ḥawrānī, also transcribed El-Hourani, Howrani or Hurani) (November 1911 – 24 February 1996), was a Syrian politician who played a prominent role during the democrat ...

, the prominent Arab socialist leader, as speaker of parliament, and Salah al-Din Bitar

Salah al-Din al-Bitar ( ar, صلاح الدين البيطار, Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn al-Biṭār; 1 January 1912 – 21 July 1980) was a Syrian politician who co-founded the Arab Ba'ath Party with Michel Aflaq in the early 1940s. As studen ...

, the co-founder of the pan-Arabist Ba'ath Party

The Arab Socialist Baʿath Party ( ar, حزب البعث العربي الاشتراكي ' ) was a political party founded in Syria by Mishel ʿAflaq, Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn al-Bītār, and associates of Zaki al-ʾArsūzī. The party espoused ...

, as foreign affairs minister.

Unity with Egypt

Amid the euphoria generated by Egypt's military intervention, serious unity discussions commenced between Syria and Egypt. Towards the end of October, Anwar al-Sadat, the Egyptian speaker of parliament, visited the Syrian parliament in Damascus in a gesture of solidarity, only for the visit to end with the Syrian parliament voting unanimously to enter into a union with Egypt without delay. A Syrian delegation then headed for Cairo to persuade Nasser to accept unity with Syria, but Nasser expressed his reservations regarding unity to the delegates and Quwatli, who was in Damascus. Nasser was wary of the Syrian military's habitual interference in the country's political affairs and the stark difference in the countries' economies and political systems. The Syrian political and military leadership continued to press Nasser out of both sincere commitment to Arab nationalism and a realization that only unification with Egypt could prevent impending strife in the country due to increasing communist influence.

In December, the Ba'ath Party composed a proposal entailing federal unity with Egypt, prompting their communist rivals to propose a total union. While the communists were less eager to merge with Egypt, they sought to appear before the Syrian public as the group most dedicated to unity, privately believing Nasser would reject the offer as he had the first time. According to historian Adeed Dawisha, "the communists ended up outmaneuvering themselves ... unprepared for the unfolding events spearheaded by a public driven to frenzy by all talk and promises of union." On 11 January 1958, the communist chief-of-staff, Bizri, led an officers delegation to press for unity with Cairo without consulting Quwatli beforehand. Instead, the Egyptian ambassador,

Amid the euphoria generated by Egypt's military intervention, serious unity discussions commenced between Syria and Egypt. Towards the end of October, Anwar al-Sadat, the Egyptian speaker of parliament, visited the Syrian parliament in Damascus in a gesture of solidarity, only for the visit to end with the Syrian parliament voting unanimously to enter into a union with Egypt without delay. A Syrian delegation then headed for Cairo to persuade Nasser to accept unity with Syria, but Nasser expressed his reservations regarding unity to the delegates and Quwatli, who was in Damascus. Nasser was wary of the Syrian military's habitual interference in the country's political affairs and the stark difference in the countries' economies and political systems. The Syrian political and military leadership continued to press Nasser out of both sincere commitment to Arab nationalism and a realization that only unification with Egypt could prevent impending strife in the country due to increasing communist influence.

In December, the Ba'ath Party composed a proposal entailing federal unity with Egypt, prompting their communist rivals to propose a total union. While the communists were less eager to merge with Egypt, they sought to appear before the Syrian public as the group most dedicated to unity, privately believing Nasser would reject the offer as he had the first time. According to historian Adeed Dawisha, "the communists ended up outmaneuvering themselves ... unprepared for the unfolding events spearheaded by a public driven to frenzy by all talk and promises of union." On 11 January 1958, the communist chief-of-staff, Bizri, led an officers delegation to press for unity with Cairo without consulting Quwatli beforehand. Instead, the Egyptian ambassador, Mahmud Riad

Mahmoud Riad ( ar, محمود رياض) (January 8, 1917 – January 25, 1992) was an Egyptian diplomat. He was Egyptian ambassador to United Nations from 1962 to 1964, Egyptian Minister of Foreign Affairs from 1964 to 1972, and Secretary-Gener ...

, met and notified Quwatli of Bizri's move. Quwatli was angered at the military's move, telling Riad that it amounted to a coup and Egypt was complicit.