Sergey Sazonov (general) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

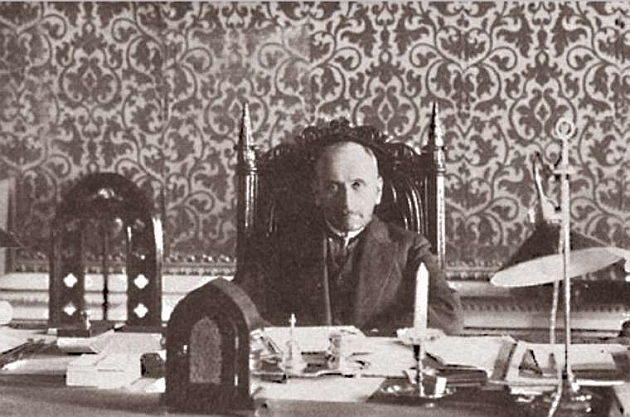

Sergei Dmitryevich Sazonov GCB (Russian: Сергей Дмитриевич Сазонов; 10 August 1860 in Ryazan Governorate 11 December 1927) was a Russian statesman and diplomat who served as

In the run-up to a major military conflict in Europe, another concern of the Russian minister was to isolate

In the run-up to a major military conflict in Europe, another concern of the Russian minister was to isolate FAZ 25.11.1916 Russlands Ministerpräsident zurückgetreten

/ref> and only after the minister had aired a proposal to grant autonomy to Poland.

online

vol 2 pp 289–370.

Foreign Minister

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between cou ...

from November 1910 to July 1916. The degree of his involvement in the events leading up to the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

is a matter of keen debate, with some historians putting the blame for an early and provocative mobilization

Mobilization is the act of assembling and readying military troops and supplies for war. The word ''mobilization'' was first used in a military context in the 1850s to describe the preparation of the Prussian Army. Mobilization theories and ...

squarely on Sazonov's shoulders, and others maintaining that his chief preoccupation was "to reduce the temperature of international relations, especially in the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

".John M. Bourne. ''Who's Who in World War One''. Routledge, 2001. . Page 259.

Early career

Of lesser noble background, Sazonov was the brother-in-law of Prime MinisterPyotr Stolypin

Pyotr Arkadyevich Stolypin ( rus, Пётр Арка́дьевич Столы́пин, p=pʲɵtr ɐrˈkadʲjɪvʲɪtɕ stɐˈlɨpʲɪn; – ) was a Russian politician and statesman. He served as the third prime minister and the interior minist ...

, who did his best to further Sazonov's career. Sazonov was born into family of Dmitry Sazonov and Yermioniya Frederiks (Freedericksz). Having graduated from the Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum

The Imperial Lyceum (Императорский Царскосельский лицей, ''Imperatorskiy Tsarskosel'skiy litsey'') in Tsarskoye Selo near Saint Petersburg, also known historically as the Imperial Alexander Lyceum after its founde ...

, Sazonov served in the London embassy, and the diplomatic mission to the Vatican, of which he became the chief in March 1906. On 26 June 1909 Sazonov was recalled to St. Petersburg and appointed Assistant Foreign Minister. Before long he replaced Alexander Izvolsky

Count Alexander Petrovich Izvolsky or Iswolsky (russian: Алекса́ндр Петро́вич Изво́льский, , Moscow – 16 August 1919, Paris) was a Russian diplomat remembered as a major architect of Russia's alliance with Grea ...

as Foreign Minister and followed a policy along the lines laid down by Stolypin.

Foreign Minister

Potsdam Agreement

Just before he was officially appointed foreign minister, Sazonov attended a meeting between Nicholas II of Russia and Wilhelm II of Germany inPotsdam

Potsdam () is the capital and, with around 183,000 inhabitants, largest city of the German state of Brandenburg. It is part of the Berlin/Brandenburg Metropolitan Region. Potsdam sits on the River Havel, a tributary of the Elbe, downstream of B ...

on 4–6 November 1910. This move was intended to chastise the British for their perceived betrayal of Russia's interests during the Bosnian Crisis. Indeed, Britain's Foreign Secretary

The secretary of state for foreign, Commonwealth and development affairs, known as the foreign secretary, is a minister of the Crown of the Government of the United Kingdom and head of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. Seen as ...

Edward Grey, 1st Viscount Grey of Fallodon

Edward Grey, 1st Viscount Grey of Fallodon, (25 April 1862 – 7 September 1933), better known as Sir Edward Grey, was a British Liberal statesman and the main force behind British foreign policy in the era of the First World War.

An adher ...

was seriously alarmed by this token of a "German-Russian Détente

Détente (, French: "relaxation") is the relaxation of strained relations, especially political ones, through verbal communication. The term, in diplomacy, originates from around 1912, when France and Germany tried unsuccessfully to reduc ...

".Siegel, Jennifer. ''Endgame: Britain, Russia and the Final Struggle for Central Asia''. I.B. Tauris, 2002. . Pages 90-92.

The two monarchs discussed the ambitious German project of the Baghdad Railway, widely expected to give Berlin considerable geopolitical clout in the Fertile Crescent

The Fertile Crescent ( ar, الهلال الخصيب) is a crescent-shaped region in the Middle East, spanning modern-day Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine and Jordan, together with the northern region of Kuwait, southeastern region of ...

. Against the background of the Persian Constitutional Revolution

The Persian Constitutional Revolution ( fa, مشروطیت, Mashrūtiyyat, or ''Enghelāb-e Mashrūteh''), also known as the Constitutional Revolution of Iran, took place between 1905 and 1911. The revolution led to the establishment of a par ...

, Russia was anxious to control the prospective railway branch from Tehran

Tehran (; fa, تهران ) is the largest city in Tehran Province and the capital of Iran. With a population of around 9 million in the city and around 16 million in the larger metropolitan area of Greater Tehran, Tehran is the most popul ...

to Khanaqin

Khanaqin ( ar, خانقين; ku, خانەقین, translit=Xaneqîn) is the central city of Khanaqin District in Diyala Governorate, Iraq, near the Iranian border (8 km) on the Alwand tributary of the Diyala River. The town is populated b ...

, on the Turco-Persian frontier, financed by Russian and German capital; and Germany to link this branch to the Baghdad Railway. The two powers settled their differences in the Potsdam Agreement

The Potsdam Agreement (german: Potsdamer Abkommen) was the agreement between three of the Allies of World War II: the United Kingdom, the United States, and the Soviet Union on 1 August 1945. A product of the Potsdam Conference, it concerned th ...

, signed on 19 August 1911, Germany giving Russia a free hand in Northern Iran and Russia in turn recognizing Germany's rights on the Baghdad Railway. Sazonov was sick during that time, his office was led by Anatoly Neratov during his absence. However, as Sazonov hoped, the first railway connecting Persia to Europe would provide Russia with a lever of influence over its southern neighbour.

Notwithstanding the promising beginning, the Russian-German relations disintegrated in 1913, when the Kaiser sent one of his generals to reorganize the Turkish army and to supervise the garrison in Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

on request of the Ottomans, remarking that "the German flag will soon fly over the fortifications of the Bosphorus

The Bosporus Strait (; grc, Βόσπορος ; tr, İstanbul Boğazı 'Istanbul strait', colloquially ''Boğaz'') or Bosphorus Strait is a natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in Istanbul in northwestern Tu ...

", a vital trade artery which accounted for two fifths of Russia's exports.

Alliance with Japan

Despite his fixation on Russian-German affairs, Sazonov was also mindful of Russian interests in theFar East

The ''Far East'' was a European term to refer to the geographical regions that includes East and Southeast Asia as well as the Russian Far East to a lesser extent. South Asia is sometimes also included for economic and cultural reasons.

The ter ...

. In the wake of the disastrous Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

, he steadily made friendly overtures toward Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

. As a result, a secret convention was signed in St. Petersburg on 8 July 1912 concerning the delimitation

Boundary delimitation (or simply delimitation) is the drawing of boundaries, particularly of electoral precincts, states, counties or other municipalities.

of spheres of interest in Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia, officially the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China. Its border includes most of the length of China's border with the country of Mongolia. Inner Mongolia also accounts for a ...

. Both powers determined to keep Inner Mongolia politically separate from Outer Mongolia

Outer Mongolia was the name of a territory in the Manchu-led Qing dynasty of China from 1691 to 1911. It corresponds to the modern-day independent state of Mongolia and the Russian republic of Tuva. The historical region gained ''de facto' ...

. Four years later, Sazonov congratulated himself on concluding a Russian-Japanese defensive alliance (3 July 1916) aimed at securing the interests of both powers in China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

.

World War I

In the run-up to a major military conflict in Europe, another concern of the Russian minister was to isolate

In the run-up to a major military conflict in Europe, another concern of the Russian minister was to isolate Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, mainly by playing the Balkan card against the dwindling power of the Habsburgs

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

. Since Sazonov was moderate in his Balkan politics, his ministry "came under frequent nationalist fire for failing to conform to a rigid pan-Slav

Pan-Slavism, a movement which crystallized in the mid-19th century, is the political ideology concerned with the advancement of integrity and unity for the Slavic people. Its main impact occurred in the Balkans, where non-Slavic empires had ruled ...

line".

While the extremist agents like Nicholas Hartwig

Baron Nicholas Genrikhovich Hartwig (, ; December 16, 1857 – July 10, 1914) was an Imperial Russian diplomat and Tsarist official who served as ambassador to Persia (1906–1908) and Serbia (1909–1914). An ardent Pan-Slavist, he was said to ...

aspired to solidify the conflicting South Slavic states into a confederacy under the aegis of the Tsar, there is no indication that Sazonov personally shared or encouraged these views. Regardless, both Austria-Hungary and Germany were persuaded that Russia fomented Pan-Slavism in Belgrade

Belgrade ( , ;, ; Names of European cities in different languages: B, names in other languages) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city in Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers a ...

and other Slavic capitals, a belligerent attitude in some measure responsible for the Assassination in Sarajevo

Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, heir presumptive to the Austria-Hungary, Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife, Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, were Assassination, assassinated on 28 June 1914 by Serbs of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bosnian Se ...

and the outbreak of the Great War.

Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe, Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Bas ...

was largely viewed as being within Russia's sphere of influence and there was significant support from the political class and the broader population for the Serbian cause. That caused Russia to defend Serbia against Austria-Hungary after the assassination of the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand. Sazonov warned Austria-Hungary in 1914 that Russia, "would respond militarily to any action against the client state."

As World War I unwound, Sazonov worked to prevent Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

from joining the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

and wrested in March 1915 an acquiescence from Russia's allies to the post-war occupation of the Bosphorus, Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

, and the European side of the Dardanelles. On 1 October 1914 Sazonov gave a written guarantee to Romania that, if the country sided with the Entente, it would be enlarged at the expense of the Austro-Hungarian dominions in Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the Ap ...

, Bukovina

Bukovinagerman: Bukowina or ; hu, Bukovina; pl, Bukowina; ro, Bucovina; uk, Буковина, ; see also other languages. is a historical region, variously described as part of either Central or Eastern Europe (or both).Klaus Peter BergerT ...

, and the Banat

Banat (, ; hu, Bánság; sr, Банат, Banat) is a geographical and historical region that straddles Central and Eastern Europe and which is currently divided among three countries: the eastern part lies in western Romania (the counties of T ...

. In general, "his calm and courteous manner did much to maintain fruitful Allied relations".

He accepted a request from the professor Tomáš Masaryk

Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk (7 March 185014 September 1937) was a Czechoslovak politician, statesman, sociologist, and philosopher. Until 1914, he advocated restructuring the Austro-Hungarian Empire into a federal state. With the help of t ...

for Russian army soldiers to not shoot on Czech refugees in October 1914.

Sazonov was viewed favourably in London, but the Germanophile faction of Tsarina Alexandra

Alexandra () is the feminine form of the given name Alexander (, ). Etymologically, the name is a compound of the Greek verb (; meaning 'to defend') and (; GEN , ; meaning 'man'). Thus it may be roughly translated as "defender of man" or "prot ...

fiercely urged his dismissal, which did materialize on 10 July 1916/ref> and only after the minister had aired a proposal to grant autonomy to Poland.

Later life

Early in 1917, Sazonov was appointed ambassador to Great Britain, but found it necessary to remain in Russia, where he witnessed theFebruary Revolution

The February Revolution ( rus, Февра́льская револю́ция, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=fʲɪvˈralʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and somet ...

.

He was opposed to Bolshevism, advised Anton Denikin

Anton Ivanovich Denikin (russian: Анто́н Ива́нович Дени́кин, link= ; 16 December Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_December.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New St ...

on international affairs, and was foreign minister in the anti-Bolshevik government of Admiral Kolchak. In 1919 he represented the Provisional All-Russian Government, the Allied recognized government of Russia, at the Paris Peace Conference. Sazonov spent his last years in France writing a book of memoirs. He died in Nice

Nice ( , ; Niçard: , classical norm, or , nonstandard, ; it, Nizza ; lij, Nissa; grc, Νίκαια; la, Nicaea) is the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes department in France. The Nice agglomeration extends far beyond the administrative c ...

where he is buried.

See also

*Russian entry into World War I

The Russian Empire gradually entered World War I during the three days prior to 28th July 1914. This began with Austria-Hungary's declaration of war against Serbia, which was a Russian ally. The Russian Empire sent an ultimatum, via Saint Petersb ...

References

Further reading

* Gooch, G.P. ''Before the war: studies in diplomacy'' (2 vol 1936, 1938online

vol 2 pp 289–370.

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Sazonov, Sergei Dmitrievich 1860 births 1927 deaths People from Ryazan Governorate Nobility from the Russian Empire Foreign ministers of the Russian Empire Ambassadors of the Russian Empire to the United Kingdom Russian anti-communists Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum alumni Russian people of World War I Honorary Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Emigrants from the Russian Empire to France