Sei whale on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The sei whale ( , ; ''Balaenoptera borealis'') is a

The sei whale is the third-largest balaenopterid, after the blue whale (up to 180 tonnes, 200 tons) and the fin whale (up to 70 tonnes, 77 tons) but close to the humpback whale. In the North Pacific, adult males average and adult females average , weighing 15 and 18.5 tonnes (16.5 and 20.5 tons), while in the North Atlantic adult males average and adult females , weighing 15.5 and 17 tonnes (17 and 18.5 tons) In the Southern Hemisphere, they average 14.5 (47.5 ft) and , respectively, weighing 17 and 18.5 tonnes (18.5 and 20.5 tons). (Evans, Peter G. H. (1987). ''The Natural History of Whales and Dolphins''. Facts on File. In the Northern Hemisphere, males reach up to and females up to , while in the Southern Hemisphere males reach and females —the authenticity of an alleged female caught 50 miles northwest of St. Kilda in July 1911 is doubted.Skinner, J.D. and Christian T. Chimimba. (2006). ''The Mammals of the Southern African Sub-region''. Cambridge University Press, Third Edition.Thompson, D'Arcy Wentworth. "On whales landed at the Scottish whaling stations, especially during the years 1908–1914—Part VII. The sei-whale". ''The Scottish Naturalist'', nos. 85-96 (1919), pp. 37–46. The largest specimens taken off

The sei whale is the third-largest balaenopterid, after the blue whale (up to 180 tonnes, 200 tons) and the fin whale (up to 70 tonnes, 77 tons) but close to the humpback whale. In the North Pacific, adult males average and adult females average , weighing 15 and 18.5 tonnes (16.5 and 20.5 tons), while in the North Atlantic adult males average and adult females , weighing 15.5 and 17 tonnes (17 and 18.5 tons) In the Southern Hemisphere, they average 14.5 (47.5 ft) and , respectively, weighing 17 and 18.5 tonnes (18.5 and 20.5 tons). (Evans, Peter G. H. (1987). ''The Natural History of Whales and Dolphins''. Facts on File. In the Northern Hemisphere, males reach up to and females up to , while in the Southern Hemisphere males reach and females —the authenticity of an alleged female caught 50 miles northwest of St. Kilda in July 1911 is doubted.Skinner, J.D. and Christian T. Chimimba. (2006). ''The Mammals of the Southern African Sub-region''. Cambridge University Press, Third Edition.Thompson, D'Arcy Wentworth. "On whales landed at the Scottish whaling stations, especially during the years 1908–1914—Part VII. The sei-whale". ''The Scottish Naturalist'', nos. 85-96 (1919), pp. 37–46. The largest specimens taken off

The whale's body is typically a dark steel grey with irregular light grey to white markings on the ventral surface, or towards the front of the lower body. The whale has a relatively short series of 32–60 pleats or grooves along its ventral surface that extend halfway between the pectoral fins and umbilicus (in other species it usually extends to or past the umbilicus), restricting the expansion of the buccal cavity during feeding compared to other species. The rostrum is pointed and the

The whale's body is typically a dark steel grey with irregular light grey to white markings on the ventral surface, or towards the front of the lower body. The whale has a relatively short series of 32–60 pleats or grooves along its ventral surface that extend halfway between the pectoral fins and umbilicus (in other species it usually extends to or past the umbilicus), restricting the expansion of the buccal cavity during feeding compared to other species. The rostrum is pointed and the  Adults have 300–380 ashy-black baleen plates on each side of the mouth, up to long. Each plate is made of fingernail-like

Adults have 300–380 ashy-black baleen plates on each side of the mouth, up to long. Each plate is made of fingernail-like

This rorqual is a

This rorqual is a

Sei whales live in all oceans, although rarely in polar or tropical waters. The difficulty of distinguishing them at sea from their close relatives, Bryde's whales and in some cases from fin whales, creates confusion about their range and population, especially in warmer waters where Bryde's whales are most common.

In the North Atlantic, its range extends from

Sei whales live in all oceans, although rarely in polar or tropical waters. The difficulty of distinguishing them at sea from their close relatives, Bryde's whales and in some cases from fin whales, creates confusion about their range and population, especially in warmer waters where Bryde's whales are most common.

In the North Atlantic, its range extends from

In the North Atlantic between 1885 and 1984, 14,295 sei whales were taken. They were hunted in large numbers off the coasts of Norway and Scotland beginning in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and in 1885 alone, more than 700 were caught off

In the North Atlantic between 1885 and 1984, 14,295 sei whales were taken. They were hunted in large numbers off the coasts of Norway and Scotland beginning in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and in 1885 alone, more than 700 were caught off

The sei whale did not have meaningful international protection until 1970, when the

The sei whale did not have meaningful international protection until 1970, when the

" of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). As amended by the Conference of the Parties in 1985, 1988, 1991, 1994, 1997, 1999, 2002, 2005 and 2008. Effective: 5 March 2009. and Appendix II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals ( CMS). It is listed on Appendix I as this species has been categorized as being in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant proportion of their range and CMS parties strive towards strictly protecting these animals, conserving or restoring the places where they live, mitigating obstacles to migration and controlling other factors that might endanger them and also on Appendix II as it has an unfavourable conservation status or would benefit significantly from international co-operation organised by tailored agreements. Sei whale is covered by the Memorandum of Understanding for the Conservation of Cetaceans and Their Habitats in the Pacific Islands Region ( Pacific Cetaceans MOU) and the Agreement on the Conservation of Small Cetaceans of the Baltic, North East Atlantic, Irish and North Seas ( ASCOBAMS). The species is listed as endangered by the U.S. government

''Sei whale''. Encyclopedia of Earth, National Council for Science and Environment; content partner Encyclopedia of Life

*''Whales & Dolphins Guide to the Biology and Behaviour of Cetaceans'', Maurizio Wurtz and Nadia Repetto. *''Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals'', editors Perrin, Wursig and Thewissen, *''Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises'', Carwardine (1995, reprinted 2000), *

*ARKive �

images and movies of the sei whale ''(Balaenoptera borealis)''World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) – species profile for the Sei WhaleOfficial website of the Agreement on the Conservation of Cetaceans in the Black Sea, Mediterranean Sea and Contiguous Atlantic Area

{{Authority control Cetaceans of the Arctic Ocean Baleen whales Mammals of Japan Cetaceans of the Indian Ocean Cetaceans of the Atlantic Ocean Cetaceans of the Pacific Ocean Mammals described in 1828 ESA endangered species

baleen whale

Baleen whales ( systematic name Mysticeti), also known as whalebone whales, are a parvorder of carnivorous marine mammals of the infraorder Cetacea ( whales, dolphins and porpoises) which use keratinaceous baleen plates (or "whalebone") in th ...

, the third-largest rorqual after the blue whale

The blue whale (''Balaenoptera musculus'') is a marine mammal and a baleen whale. Reaching a maximum confirmed length of and weighing up to , it is the largest animal known to have ever existed. The blue whale's long and slender body can b ...

and the fin whale

The fin whale (''Balaenoptera physalus''), also known as finback whale or common rorqual and formerly known as herring whale or razorback whale, is a cetacean belonging to the parvorder of baleen whales. It is the second-longest species of c ...

. It inhabits most oceans and adjoining seas, and prefers deep offshore waters. It avoids polar and tropical

The tropics are the regions of Earth surrounding the Equator. They are defined in latitude by the Tropic of Cancer in the Northern Hemisphere at N and the Tropic of Capricorn in

the Southern Hemisphere at S. The tropics are also referred to ...

waters and semi-enclosed bodies of water. The sei whale migrates annually from cool, subpolar waters in summer to temperate

In geography, the temperate climates of Earth occur in the middle latitudes (23.5° to 66.5° N/S of Equator), which span between the tropics and the polar regions of Earth. These zones generally have wider temperature ranges throughout t ...

, subtropical waters in winter with a lifespan of 70 years.

Reaching in length and weighing as much as , the sei whale consumes an average of of food every day; its diet consists primarily of copepod

Copepods (; meaning "oar-feet") are a group of small crustaceans found in nearly every freshwater and saltwater habitat. Some species are planktonic (inhabiting sea waters), some are benthic (living on the ocean floor), a number of species have p ...

s, krill, and other zooplankton

Zooplankton are the animal component of the planktonic community ("zoo" comes from the Greek word for ''animal''). Plankton are aquatic organisms that are unable to swim effectively against currents, and consequently drift or are carried along by ...

. It is among the fastest of all cetaceans, and can reach speeds of up to (27 knots) over short distances. The whale's name comes from the Norwegian word for pollock

Pollock or pollack (pronounced ) is the common name used for either of the two species of North Atlantic marine fish in the genus ''Pollachius''. '' Pollachius pollachius'' is referred to as pollock in North America, Ireland and the United Ki ...

, a fish that appears off the coast of Norway at the same time of the year as the sei whale.

Following large-scale commercial whaling during the late 19th and 20th centuries, when over 255,000 whales were killed, the sei whale is now internationally protected. , its worldwide population was about 80,000, less than a third of its prewhaling population.

Etymology

''Sei'' is the Norwegian word forpollock

Pollock or pollack (pronounced ) is the common name used for either of the two species of North Atlantic marine fish in the genus ''Pollachius''. '' Pollachius pollachius'' is referred to as pollock in North America, Ireland and the United Ki ...

, also referred to as coalfish, a close relative of codfish. Sei whales appeared off the coast of Norway at the same time as the pollock, both coming to feed on the abundant plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms found in water (or air) that are unable to propel themselves against a current (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are called plankters. In the ocean, they provide a cr ...

. The specific name is the Latin word ''borealis'', meaning northern. In the Pacific, the whale has been called the Japan finner; "finner" was a common term used to refer to rorquals. In Japanese, the whale was called ''iwashi kujira'', or sardine whale, a name originally applied to Bryde's whales by early Japanese whalers. Later, as modern whaling shifted to Sanriku—where both species occur—it was confused for the sei whale. Now the term only applies to the latter species. It has also been referred to as the lesser fin whale because it somewhat resembles the fin whale. The American naturalist Roy Chapman Andrews

Roy Chapman Andrews (January 26, 1884 – March 11, 1960) was an American explorer, adventurer and naturalist who became the director of the American Museum of Natural History. He led a series of expeditions through the politically disturbed ...

compared the sei whale to the cheetah

The cheetah (''Acinonyx jubatus'') is a large cat native to Africa and central Iran. It is the fastest land animal, estimated to be capable of running at with the fastest reliably recorded speeds being , and as such has evolved specialized ...

, because it can swim at great speeds "for a few hundred yards", but it "soon tires if the chase is long" and "does not have the strength and staying power of its larger relatives".

Taxonomy

On 21 February 1819, a 32-ft whale stranded near Grömitz, inSchleswig-Holstein

Schleswig-Holstein (; da, Slesvig-Holsten; nds, Sleswig-Holsteen; frr, Slaswik-Holstiinj) is the northernmost of the 16 states of Germany, comprising most of the historical duchy of Holstein and the southern part of the former Duchy of Sc ...

. The Swedish-born German naturalist Karl Rudolphi initially identified it as ''Balaena rostrata'' (=''Balaenoptera acutorostrata''). In 1823, the French naturalist Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, Baron Cuvier (; 23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier, was a French naturalist and zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuvier was a major figure in na ...

described and figured Rudolphi's specimen under the name "rorqual du Nord". In 1828, Rene Lesson translated this term into ''Balaenoptera borealis'', basing his designation partly on Cuvier's description of Rudolphi's specimen and partly on a 54-ft female that had stranded on the coast of France the previous year (this was later identified as a juvenile fin whale, ''Balaenoptera physalus''). In 1846, the English zoologist John Edward Gray

John Edward Gray, Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (12 February 1800 – 7 March 1875) was a British zoology, zoologist. He was the elder brother of zoologist George Robert Gray and son of the pharmacologist and botanist Samuel Frederick Gray ...

, ignoring Lesson's designation, named Rudolphi's specimen ''Balaenoptera laticeps'', which others followed. In 1865, the British zoologist William Henry Flower named a 45-ft specimen that had been obtained from Pekalongan, on the north coast of Java

Java (; id, Jawa, ; jv, ꦗꦮ; su, ) is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea to the north. With a population of 151.6 million people, Java is the world's mo ...

, ''Sibbaldius'' (=''Balaenoptera'') ''schlegelii''—in 1946 the Russian scientist A.G. Tomilin synonymized ''S. schlegelii'' and ''B. borealis'', creating the subspecies ''B. b. schlegelii'' and ''B. b. borealis''.Perrin, William F., James G. Mead, and Robert L. Brownell, Jr. "Review of the evidence used in the description of currently recognized cetacean subspecies". ''NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS'' (December 2009), pp. 1–35. In 1884–85, the Norwegian scientist G. A. Guldberg first identified the "sejhval" of Finnmark

Finnmark (; se, Finnmárku ; fkv, Finmarku; fi, Ruija ; russian: Финнмарк) was a county in the northern part of Norway, and it is scheduled to become a county again in 2024.

On 1 January 2020, Finnmark was merged with the neighbouri ...

with ''B. borealis''.

Sei whales are rorquals (family Balaenopteridae), baleen whales that include the humpback whale

The humpback whale (''Megaptera novaeangliae'') is a species of baleen whale. It is a rorqual (a member of the family Balaenopteridae) and is the only species in the genus ''Megaptera''. Adults range in length from and weigh up to . The hum ...

, the blue whale

The blue whale (''Balaenoptera musculus'') is a marine mammal and a baleen whale. Reaching a maximum confirmed length of and weighing up to , it is the largest animal known to have ever existed. The blue whale's long and slender body can b ...

, Bryde's whale, the fin whale

The fin whale (''Balaenoptera physalus''), also known as finback whale or common rorqual and formerly known as herring whale or razorback whale, is a cetacean belonging to the parvorder of baleen whales. It is the second-longest species of c ...

, and the minke whale. Rorquals take their name from the Norwegian word ''røyrkval'', meaning "furrow whale", because family members have a series of longitudinal pleats or grooves on the anterior half of their ventral surface. Balaenopterids diverged from the other families of suborder Mysticeti, also called the whalebone whales, as long ago as the middle Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and means "less recent" ...

. Little is known about when members of the various families in the Mysticeti, including the Balaenopteridae, diverged from each other.

Two subspecies have been identified—the northern sei whale (''B. b. borealis'') and southern sei whale (''B. b. schlegelii'').

Description

The sei whale is the third-largest balaenopterid, after the blue whale (up to 180 tonnes, 200 tons) and the fin whale (up to 70 tonnes, 77 tons) but close to the humpback whale. In the North Pacific, adult males average and adult females average , weighing 15 and 18.5 tonnes (16.5 and 20.5 tons), while in the North Atlantic adult males average and adult females , weighing 15.5 and 17 tonnes (17 and 18.5 tons) In the Southern Hemisphere, they average 14.5 (47.5 ft) and , respectively, weighing 17 and 18.5 tonnes (18.5 and 20.5 tons). (Evans, Peter G. H. (1987). ''The Natural History of Whales and Dolphins''. Facts on File. In the Northern Hemisphere, males reach up to and females up to , while in the Southern Hemisphere males reach and females —the authenticity of an alleged female caught 50 miles northwest of St. Kilda in July 1911 is doubted.Skinner, J.D. and Christian T. Chimimba. (2006). ''The Mammals of the Southern African Sub-region''. Cambridge University Press, Third Edition.Thompson, D'Arcy Wentworth. "On whales landed at the Scottish whaling stations, especially during the years 1908–1914—Part VII. The sei-whale". ''The Scottish Naturalist'', nos. 85-96 (1919), pp. 37–46. The largest specimens taken off

The sei whale is the third-largest balaenopterid, after the blue whale (up to 180 tonnes, 200 tons) and the fin whale (up to 70 tonnes, 77 tons) but close to the humpback whale. In the North Pacific, adult males average and adult females average , weighing 15 and 18.5 tonnes (16.5 and 20.5 tons), while in the North Atlantic adult males average and adult females , weighing 15.5 and 17 tonnes (17 and 18.5 tons) In the Southern Hemisphere, they average 14.5 (47.5 ft) and , respectively, weighing 17 and 18.5 tonnes (18.5 and 20.5 tons). (Evans, Peter G. H. (1987). ''The Natural History of Whales and Dolphins''. Facts on File. In the Northern Hemisphere, males reach up to and females up to , while in the Southern Hemisphere males reach and females —the authenticity of an alleged female caught 50 miles northwest of St. Kilda in July 1911 is doubted.Skinner, J.D. and Christian T. Chimimba. (2006). ''The Mammals of the Southern African Sub-region''. Cambridge University Press, Third Edition.Thompson, D'Arcy Wentworth. "On whales landed at the Scottish whaling stations, especially during the years 1908–1914—Part VII. The sei-whale". ''The Scottish Naturalist'', nos. 85-96 (1919), pp. 37–46. The largest specimens taken off Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its ...

were a female and a male, while the longest off Nova Scotia were two females and a male. The longest measured during JARPN II cruises in the North Pacific were a female and a male. The longest measured by Discovery Committee staff were an adult male of and an adult female of , both caught off South Georgia. Adults usually weigh between 15 and 20 metric tons—a pregnant female caught off Natal in 1966 weighed 37.75 tonnes (41.6 tons), not including 6% for loss of fluids during flensing. Females are considerably larger than males. At birth, a calf typically measures in length.

Anatomy

The whale's body is typically a dark steel grey with irregular light grey to white markings on the ventral surface, or towards the front of the lower body. The whale has a relatively short series of 32–60 pleats or grooves along its ventral surface that extend halfway between the pectoral fins and umbilicus (in other species it usually extends to or past the umbilicus), restricting the expansion of the buccal cavity during feeding compared to other species. The rostrum is pointed and the

The whale's body is typically a dark steel grey with irregular light grey to white markings on the ventral surface, or towards the front of the lower body. The whale has a relatively short series of 32–60 pleats or grooves along its ventral surface that extend halfway between the pectoral fins and umbilicus (in other species it usually extends to or past the umbilicus), restricting the expansion of the buccal cavity during feeding compared to other species. The rostrum is pointed and the pectoral fins

Fins are distinctive anatomical features composed of bony spines or rays protruding from the body of a fish. They are covered with skin and joined together either in a webbed fashion, as seen in most bony fish, or similar to a flipper, as s ...

are relatively short, only 9%–10% of body length, and pointed at the tips. It has a single ridge extending from the tip of the rostrum to the paired blowholes that are a distinctive characteristic of baleen whales.

The whale's skin is often marked by pits or wounds, which after healing become white scars. These are now known to be caused by "cookie-cutter" sharks (''Isistius brasiliensis''). It has a tall, sickle

A sickle, bagging hook, reaping-hook or grasshook is a single-handed agricultural tool designed with variously curved blades and typically used for harvesting, or reaping, grain crops or cutting succulent forage chiefly for feeding livestock, ...

-shaped dorsal fin

A dorsal fin is a fin located on the back of most marine and freshwater vertebrates within various taxa of the animal kingdom. Many species of animals possessing dorsal fins are not particularly closely related to each other, though through c ...

that ranges in height from and averages , about two-thirds of the way back from the tip of the rostrum. Dorsal fin shape, pigment

A pigment is a colored material that is completely or nearly insoluble in water. In contrast, dyes are typically soluble, at least at some stage in their use. Generally dyes are often organic compounds whereas pigments are often inorganic comp ...

ation pattern, and scarring have been used to a limited extent in photo-identification studies. The tail is thick and the fluke, or lobe, is relatively small in relation to the size of the whale's body.

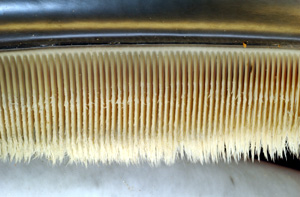

Adults have 300–380 ashy-black baleen plates on each side of the mouth, up to long. Each plate is made of fingernail-like

Adults have 300–380 ashy-black baleen plates on each side of the mouth, up to long. Each plate is made of fingernail-like keratin

Keratin () is one of a family of structural fibrous proteins also known as ''scleroproteins''. Alpha-keratin (α-keratin) is a type of keratin found in vertebrates. It is the key structural material making up scales, hair, nails, feathers, ...

, which is bordered by a fringe of very fine, short, curly, wool-like white bristles. The sei's very fine baleen bristles, about are the most reliable characteristic that distinguishes it from other rorquals.

The sei whale looks very similar to other large rorquals, especially its smaller relative the Bryde's whale. The best way to distinguish between it and Bryde's whale, apart from differences in baleen plates, is by the presence of lateral ridges on the dorsal surface of the Bryde's whale's rostrum. Large individuals can be confused with fin whales, unless the fin whale's asymmetrical head coloration is clearly seen. The fin whale's lower jaw's right side is white, and the left side is grey. When viewed from the side, the rostrum appears slightly arched (accentuated at the tip), while fin and Bryde's whales have relatively flat rostrums.

Life history

Surface behaviors

Sei whales usually travel alone or in pods of up to six individuals. Larger groups may assemble at particularly abundant feeding grounds. Very little is known about theirsocial structure

In the social sciences, social structure is the aggregate of patterned social arrangements in society that are both emergent from and determinant of the actions of individuals. Likewise, society is believed to be grouped into structurally rela ...

. During the southern Gulf of Maine influx in mid-1986, groups of at least three sei whales were observed "milling" on four occasions – i.e. moving in random directions, rolling, and remaining at the surface for over 10 minutes. One whale would always leave the group during or immediately after such socializing bouts.

The sei whale is among the fastest cetaceans. It can reach speeds of up to over short distances. However, it is not a remarkable diver, reaching relatively shallow depths for 5 to 15 minutes. Between dives, the whale surfaces for a few minutes, remaining visible in clear, calm waters, with blows occurring at intervals of about 60 seconds (range: 45–90 sec.). Unlike the fin whale, the sei whale tends not to rise high out of the water as it dives, usually just sinking below the surface. The blowholes and dorsal fin are often exposed above the water surface almost simultaneously. The whale almost never lifts its flukes above the surface, and are generally less active on water surfaces than closely related Bryde's whales; it rarely breaches.

Feeding

This rorqual is a

This rorqual is a filter feeder

Filter feeders are a sub-group of suspension feeding animals that feed by straining suspended matter and food particles from water, typically by passing the water over a specialized filtering structure. Some animals that use this method of feedin ...

, using its baleen plates to obtain its food by opening its mouth, engulfing or skimming large amounts of the water containing the food, then straining the water out through the baleen, trapping any food items inside its mouth.

The sei whale feeds near the surface of the ocean, swimming on its side through swarms of prey

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill the ...

to obtain its average of about of food each day. For an animal of its size, for the most part, its preferred foods lie unusually relatively low in the food chain

A food chain is a linear network of links in a food web starting from producer organisms (such as grass or algae which produce their own food via photosynthesis) and ending at an apex predator species (like grizzly bears or killer whales), d ...

, including zooplankton

Zooplankton are the animal component of the planktonic community ("zoo" comes from the Greek word for ''animal''). Plankton are aquatic organisms that are unable to swim effectively against currents, and consequently drift or are carried along by ...

and small fish. The whale's diet preferences has been determined from stomach analyses, direct observation of feeding behavior, and analyzing fecal matter collected near them, which appears as a dilute brown cloud. The feces are collected in nets and DNA is separated, individually identified, and matched with known species. The whale competes for food against clupeid fish (herring

Herring are forage fish, mostly belonging to the family of Clupeidae.

Herring often move in large schools around fishing banks and near the coast, found particularly in shallow, temperate waters of the North Pacific and North Atlantic Ocea ...

and its relatives), basking sharks, and right whale

Right whales are three species of large baleen whales of the genus ''Eubalaena'': the North Atlantic right whale (''E. glacialis''), the North Pacific right whale (''E. japonica'') and the Southern right whale (''E. australis''). They are clas ...

s.

In the North Atlantic, it feeds primarily on calanoid copepods, specifically '' Calanus finmarchicus'', with a secondary preference for euphausiids, in particular '' Meganyctiphanes norvegica'' and '' Thysanoessa inermis''. In the North Pacific, it feeds on similar zooplankton, including the copepod species ''Neocalanus cristatus'', ''N. plumchrus'', and ''Calanus pacificus'', and euphausiid species ''Euphausia pacifica'', ''E. similis'', ''Thysanoessa inermis'', ''T. longipes'', ''T. gregaria'' and ''T. spinifera''. In addition, it eats larger organisms, such as the Japanese flying squid, ''Todarodes pacificus pacificus'', and small fish, including anchovies

An anchovy is a small, common forage fish of the family Engraulidae. Most species are found in marine waters, but several will enter brackish water, and some in South America are restricted to fresh water.

More than 140 species are placed in 1 ...

(''Engraulis japonicus'' and ''E. mordax''), sardines

"Sardine" and "pilchard" are common names for various species of small, oily forage fish in the herring family Clupeidae. The term "sardine" was first used in English during the early 15th century, a folk etymology says it comes from the I ...

(''Sardinops sagax''), Pacific saury (''Cololabis saira''), mackerel

Mackerel is a common name applied to a number of different species of pelagic fish, mostly from the family Scombridae. They are found in both temperate and tropical seas, mostly living along the coast or offshore in the oceanic environment.

...

(''Scomber japonicus'' and ''S. australasicus''), jack mackerel

Jack mackerels or saurels are marine fish in the genus ''Trachurus'' of the family Carangidae. The name of the genus derives from the Greek words ''trachys'' ("rough") and ''oura'' ("tail"). Some species, such as ''T. murphyi'', are harvested in ...

(''Trachurus symmetricus'') and juvenile rockfish

Rockfish is a common term for several species of fish, referring to their tendency to hide among rocks.

The name rockfish is used for many kinds of fish used for food. This common name belongs to several groups that are not closely related, and ca ...

(''Sebastes jordani''). Some of these fish are commercially important. Off central California, they mainly feed on anchovies between June and August, and on krill (''Euphausia pacifica'') during September and October. In the Southern Hemisphere, prey species include the copepods ''Neocalanus tonsus'', ''Calanus simillimus'', and ''Drepanopus pectinatus'', as well as the euphausiids ''Euphausia superba'' and ''Euphausia vallentini'' and the pelagic amphipod '' Themisto gaudichaudii''.

Parasites and epibiotics

Ectoparasites and epibiotics are rare on sei whales. Species of the parasiticcopepod

Copepods (; meaning "oar-feet") are a group of small crustaceans found in nearly every freshwater and saltwater habitat. Some species are planktonic (inhabiting sea waters), some are benthic (living on the ocean floor), a number of species have p ...

''Pennella

''Pennella'' is a genus of large copepods which are common parasites of large pelagic fishes. They begin their life cycle as a series of free-swimming planktonic larvae. The females metamorphose into a parasitic stage when they attach to a host a ...

'' were only found on 8% of sei whales caught off California and 4% of those taken off South Georgia and South Africa. The pseudo-stalked barnacle ''Xenobalanus globicipitis'' was found on 9% of individuals caught off California; it was also found on a sei whale taken off South Africa. The acorn barnacle '' Coronula reginae'' and the stalked barnacle ''Conchoderma virgatum

''Conchoderma virgatum'' is a species of goose barnacle in the family Lepadidae. It is a pelagic species found in open water in most of the world's oceans attached to drifting objects or marine organisms.

Description

''Conchoderma virgatum'' has ...

'' were each only found on 0.4% of whales caught off California. '' Remora australis'' were rarely found on sei whales off California (only 0.8%). They often bear scars from the bites of cookiecutter sharks, with 100% of individuals sampled off California, South Africa, and South Georgia having them; these scars have also been found on sei whales captured off Finnmark. Diatom ('' Cocconeis ceticola'') films on sei whales are rare, having been found on sei whales taken off California and South Georgia.Collect, R. (1886). "On the external characters of Rudolphi's rorqual (Balaenoptera borealis)". ''Proc. Zool. Soc. London'', XVIII: 243-265.

Due to their diverse diet, endoparasites are frequent and abundant in sei whales. The harpacticoid

Harpacticoida is an order of copepods, in the subphylum Crustacea. This order comprises 463 genera and about 3,000 species; its members are benthic copepods found throughout the world in the marine environment (most families) and in fresh water ...

copepod ''Balaenophilus unisetus'' infests the baleen of sei whales caught off California, South Georgia, South Africa, and Finnmark. The ciliate

The ciliates are a group of alveolates characterized by the presence of hair-like organelles called cilia, which are identical in structure to eukaryotic flagella, but are in general shorter and present in much larger numbers, with a differen ...

protozoa

Protozoa (singular: protozoan or protozoon; alternative plural: protozoans) are a group of single-celled eukaryotes, either free-living or parasitic, that feed on organic matter such as other microorganisms or organic tissues and debris. Histor ...

n ''Haematophagus'' was commonly found in the baleen of sei whales taken off South Georgia (nearly 85%). They often carry heavy infestations of acanthocephala

Acanthocephala (Greek , ', thorn + , ', head) is a phylum of parasitic worms known as acanthocephalans, thorny-headed worms, or spiny-headed worms, characterized by the presence of an eversible proboscis, armed with spines, which it uses to p ...

ns (e.g. '' Bolbosoma turbinella'', which was found in 40% of sei whales sampled off California; it was also found in individuals off South Georgia and Finnmark) and cestodes (e.g. ''Tetrabothrius affinis

''Tetrabothrius'' is a genus of flatworms belonging to the family Tetrabothriidae.

The genus has cosmopolitan distribution.

Species:

*'' Tetrabothrius affinis''

*'' Tetrabothrius argentinum''

*''Tetrabothrius arsenyevi''

*'' Tetrabothrius ba ...

'', found in sei whales off California and South Georgia) in the intestine, nematodes in the kidneys (''Crassicauda'' sp., California) and stomach ('' Anisakis simplex'', nearly 60% of whales taken off California), and flukes (''Lecithodesmus spinosus'', found in 38% of individuals caught off California) in the liver.

Reproduction

Mating

In biology, mating is the pairing of either opposite- sex or hermaphroditic organisms for the purposes of sexual reproduction. ''Fertilization'' is the fusion of two gametes. '' Copulation'' is the union of the sex organs of two sexually rep ...

occurs in temperate

In geography, the temperate climates of Earth occur in the middle latitudes (23.5° to 66.5° N/S of Equator), which span between the tropics and the polar regions of Earth. These zones generally have wider temperature ranges throughout t ...

, subtropical seas during the winter. Gestation

Gestation is the period of development during the carrying of an embryo, and later fetus, inside viviparous animals (the embryo develops within the parent). It is typical for mammals, but also occurs for some non-mammals. Mammals during preg ...

is estimated to vary around 10 months, 11 months, or one year, depending which model of foetal growth is used. The different estimates result from scientists' inability to observe an entire pregnancy; most reproductive data for baleen whales were obtained from animals caught by commercial whalers, which offer only single snapshots of fetal growth. Researchers attempt to extrapolate conception dates by comparing fetus size and characteristics with newborns.

A newborn is weaned from its mother at 6–9 months of age, when it is long, so weaning takes place at the summer or autumn feeding grounds. Females reproduce every 2–3 years, usually to a single calf. In the Northern Hemisphere, males are usually and females at sexual maturity, while in the Southern Hemisphere, males average and females . The average age of sexual maturity of both sexes is 8–10 years. The whales can reach ages up to 65 years.

Vocalizations

The sei whale makes long, loud, low-frequency sounds. Relatively little is known about specific calls, but in 2003, observers noted sei whale calls in addition to sounds that could be described as "growls" or "whooshes" off the coast of theAntarctic Peninsula

The Antarctic Peninsula, known as O'Higgins Land in Chile and Tierra de San Martín in Argentina, and originally as Graham Land in the United Kingdom and the Palmer Peninsula in the United States, is the northernmost part of mainland Antarctic ...

. Many calls consisted of multiple parts at different frequencies. This combination distinguishes their calls from those of other whales. Most calls lasted about a half second, and occurred in the 240–625 hertz

The hertz (symbol: Hz) is the unit of frequency in the International System of Units (SI), equivalent to one event (or cycle) per second. The hertz is an SI derived unit whose expression in terms of SI base units is s−1, meaning that one her ...

range, well within the range of human hearing. The maximum volume of the vocal sequences is reported as 156 decibels relative to 1 micropascal (μPa) at a reference distance of one metre. An observer situated one metre from a vocalizing whale would perceive a volume roughly equivalent to the volume of a jackhammer operating two metres away.

In November 2002, scientists recorded calls in the presence of sei whales off Maui. All the calls were downswept tonal calls, all but two ranging from a mean high frequency of 39.1 Hz down to 21 Hz of 1.3 second duration – the two higher frequency downswept calls ranged from an average of 100.3 Hz to 44.6 Hz over 1 second of duration. These calls closely resembled and coincided with a peak in "20- to 35-Hz irregular repetition interval" downswept pulses described from seafloor recordings off Oahu

Oahu () ( Hawaiian: ''Oʻahu'' ()), also known as "The Gathering Place", is the third-largest of the Hawaiian Islands. It is home to roughly one million people—over two-thirds of the population of the U.S. state of Hawaii. The island of O� ...

, which had previously been attributed to fin whales. Between 2005 and 2007, low frequency downswept vocalizations were recorded in the Great South Channel, east of Cape Cod

Cape Cod is a peninsula extending into the Atlantic Ocean from the southeastern corner of mainland Massachusetts, in the northeastern United States. Its historic, maritime character and ample beaches attract heavy tourism during the summer mon ...

, Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

, which were only significantly associated with the presence of sei whales. These calls averaged 82.3 Hz down to 34 Hz over about 1.4 seconds in duration. This call has also been reported from recordings in the Gulf of Maine, New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian province ...

shelf waters, the mid-Atlantic Bight, and in Davis Strait. It likely functions as a contact call.

BBC News quoted Roddy Morrison, a former whaler active in South Georgia, as saying, "When we killed the sei whales, they used to make a noise, like a crying noise. They seemed so friendly, and they'd come round and they'd make a noise, and when you hit them, they cried really. I didn't think it was really nice to do that. Everybody talked about it at the time I suppose, but it was money. At the end of the day that's what counted at the time. That's what we were there for."

Range and migration

Sei whales live in all oceans, although rarely in polar or tropical waters. The difficulty of distinguishing them at sea from their close relatives, Bryde's whales and in some cases from fin whales, creates confusion about their range and population, especially in warmer waters where Bryde's whales are most common.

In the North Atlantic, its range extends from

Sei whales live in all oceans, although rarely in polar or tropical waters. The difficulty of distinguishing them at sea from their close relatives, Bryde's whales and in some cases from fin whales, creates confusion about their range and population, especially in warmer waters where Bryde's whales are most common.

In the North Atlantic, its range extends from southern Europe

Southern Europe is the southern region of Europe. It is also known as Mediterranean Europe, as its geography is essentially marked by the Mediterranean Sea. Definitions of Southern Europe include some or all of these countries and regions: Alba ...

or northwestern Africa

The Maghreb (; ar, الْمَغْرِب, al-Maghrib, lit=the west), also known as the Arab Maghreb ( ar, المغرب العربي) and Northwest Africa, is the western part of North Africa and the Arab world. The region includes Algeria, ...

to Norway, and from the southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

to Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland is ...

. The southernmost confirmed records are strandings along the northern Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United S ...

and in the Greater Antilles

The Greater Antilles ( es, Grandes Antillas or Antillas Mayores; french: Grandes Antilles; ht, Gwo Zantiy; jam, Grieta hAntiliiz) is a grouping of the larger islands in the Caribbean Sea, including Cuba, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, ...

. Throughout its range, the whale tends not to frequent semienclosed bodies of water, such as the Gulf of Mexico, the Gulf of Saint Lawrence

, image = Baie de la Tour.jpg

, alt =

, caption = Gulf of St. Lawrence from Anticosti National Park, Quebec

, image_bathymetry = Golfe Saint-Laurent Depths fr.svg

, alt_bathymetry = Bathymetry ...

, Hudson Bay

Hudson Bay ( crj, text=ᐐᓂᐯᒄ, translit=Wînipekw; crl, text=ᐐᓂᐹᒄ, translit=Wînipâkw; iu, text=ᑲᖏᖅᓱᐊᓗᒃ ᐃᓗᐊ, translit=Kangiqsualuk ilua or iu, text=ᑕᓯᐅᔭᕐᔪᐊᖅ, translit=Tasiujarjuaq; french: b ...

, the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

, and the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

. It occurs predominantly in deep water, occurring most commonly over the continental slope

A continental margin is the outer edge of continental crust abutting oceanic crust under coastal waters. It is one of the three major zones of the ocean floor, the other two being deep-ocean basins and mid-ocean ridges. The continental marg ...

, in basins situated between banks, or submarine canyon

A submarine canyon is a steep-sided valley cut into the seabed of the continental slope, sometimes extending well onto the continental shelf, having nearly vertical walls, and occasionally having canyon wall heights of up to 5 km, from ...

areas.

In the North Pacific, it ranges from 20°N to 23°N latitude

In geography, latitude is a coordinate that specifies the north– south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from –90° at the south pole to 90° at the north po ...

in the winter, and from 35°N to 50°N latitude in the summer. Approximately 75% of the North Pacific population lives east of the International Date Line

The International Date Line (IDL) is an internationally accepted demarcation on the surface of Earth, running between the South and North Poles and serving as the boundary between one calendar day and the next. It passes through the Pacific ...

, but there is little information regarding the North Pacific distribution. , the U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service

The National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), informally known as NOAA Fisheries, is a United States federal agency within the U.S. Department of Commerce's National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) that is responsible for the ste ...

estimated that the eastern North Pacific population stood at 374 whales. Two whales tagged in deep waters off California were later recaptured off Washington and British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include ...

, revealing a possible link between these areas, but the lack of other tag recovery data makes these two cases inconclusive. Occurrences within the Gulf of California

The Gulf of California ( es, Golfo de California), also known as the Sea of Cortés (''Mar de Cortés'') or Sea of Cortez, or less commonly as the Vermilion Sea (''Mar Bermejo''), is a marginal sea of the Pacific Ocean that separates the Baja C ...

have been fewer. In Sea of Japan

The Sea of Japan is the marginal sea between the Japanese archipelago, Sakhalin, the Korean Peninsula, and the mainland of the Russian Far East. The Japanese archipelago separates the sea from the Pacific Ocean. Like the Mediterranean Sea, it h ...

and Sea of Okhotsk

The Sea of Okhotsk ( rus, Охо́тское мо́ре, Ohótskoye móre ; ja, オホーツク海, Ohōtsuku-kai) is a marginal sea of the western Pacific Ocean. It is located between Russia's Kamchatka Peninsula on the east, the Kuril Islands ...

, whales are not common, although whales were more commonly seen than today in southern part of Sea of Japan from Korean Peninsula to the southern Primorsky Krai

Primorsky Krai (russian: Приморский край, r=Primorsky kray, p=prʲɪˈmorskʲɪj kraj), informally known as Primorye (, ), is a federal subject (a krai) of Russia, located in the Far East region of the country and is a part of t ...

in the past, and there had been a sighting in Golden Horn Bay

Zolotoy Rog (russian: Золотой Рог) or the Golden Horn Bay, is a sheltered horn-shaped bay of the Sea of Japan, located in coastal Primorsky Krai within the Russian Far East. Vladivostok, that lies on the hills at the head of the bay, ...

, and whales were much more abundant in the triangle area around Kunashir Island in whaling days, making the area well known as sei – ground, and there had been a sighting of a cow calf pair off the Sea of Japan

The Sea of Japan is the marginal sea between the Japanese archipelago, Sakhalin, the Korean Peninsula, and the mainland of the Russian Far East. The Japanese archipelago separates the sea from the Pacific Ocean. Like the Mediterranean Sea, it h ...

coast of mid-Honshu

, historically called , is the largest and most populous island of Japan. It is located south of Hokkaidō across the Tsugaru Strait, north of Shikoku across the Inland Sea, and northeast of Kyūshū across the Kanmon Straits. The island ...

during cetacean survey.

Sei whales have been recorded from northern Indian Ocean as well such as around Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

and India

India, officially the Republic of India ( Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the ...

n coasts.

In the Southern Hemisphere, summer distribution based upon historic catch data is between 40°S and 50°S latitude in the South Atlantic and southern Indian Oceans and 45°S and 60°S in the South Pacific, while winter distribution is poorly known, with former winter whaling grounds being located off northeastern Brazil ( 7°S) and Peru ( 6°S). The majority of the "sei" whales caught off Angola and Congo, as well as other nearby areas in equatorial West Africa, are thought to have been predominantly misidentified Bryde's whales. For example, Ruud (1952) found that 42 of the "sei whale" catch off Gabon

Gabon (; ; snq, Ngabu), officially the Gabonese Republic (french: République gabonaise), is a country on the west coast of Central Africa. Located on the equator, it is bordered by Equatorial Guinea to the northwest, Cameroon to the north ...

in 1952 were actually Bryde's whales, based on examination of their baleen plates. The only confirmed historical record is the capture of a female, which was brought to the Cap Lopez whaling station in Gabon in September 1950. During cetacean sighting surveys off Angola between 2003 and 2006, only a single confirmed sighting of two individuals was made in August 2004, compared to 19 sightings of Bryde's whales. Sei whales are commonly distributed along west to southern Latin America including along entire Chilean coasts, within Beagle Channel

Beagle Channel (; Yahgan: ''Onašaga'') is a strait in the Tierra del Fuego Archipelago, on the extreme southern tip of South America between Chile and Argentina. The channel separates the larger main island of Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego ...

and possibly feed in the Aysen region. The Falkland Islands appears to be a regionally important area for the Sei Whale, as a small population exists in coastal waters off the eastern Falkland archipelago. For reasons unknown, the whales prefer to stay inland here, even venturing into large bays. This provides scientists with a rare opportunity to study this normally pelagic species without having to travel far out into the ocean.

Migration

In general, the sei whale migrates annually from cool and subpolar waters in summer to temperate and subtropical waters for winter, where food is more abundant. In the northwest Atlantic, sightings and catch records suggest the whales move north along the shelf edge to arrive in the areas of Georges Bank,Northeast Channel

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A compass rose is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—each sep ...

, and Browns Bank by mid- to late June. They are present off the south coast of Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

in August and September, and a southbound migration begins moving west and south along the Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native En ...

n shelf from mid-September to mid-November. Whales in the Labrador Sea

The Labrador Sea (French: ''mer du Labrador'', Danish: ''Labradorhavet'') is an arm of the North Atlantic Ocean between the Labrador Peninsula and Greenland. The sea is flanked by continental shelves to the southwest, northwest, and northeast. I ...

as early as the first week of June may move farther northward to waters southwest of Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland is ...

later in the summer. In the northeast Atlantic, the sei whale winters as far south as West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, Mau ...

such as off Bay of Arguin, off coastal Western Sahara and follows the continental slope northward in spring. Large females lead the northward migration and reach the Denmark Strait earlier and more reliably than other sexes and classes, arriving in mid-July and remaining through mid-September. In some years, males and younger females remain at lower latitudes during the summer.

Despite knowing some general migration patterns, exact routes are incompletely known and scientists cannot readily predict exactly where groups will appear from one year to the next. F.O. Kapel noted a correlation between appearances west of Greenland and the incursion of relatively warm waters from the Irminger Current into that area. Some evidence from tagging data indicates individuals return off the coast of Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its ...

on an annual basis. An individual satellite-tagged off Faial, in the Azores

)

, motto=

( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem=( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

, traveled more than to the Labrador Sea via the Charlie-Gibbs Fracture Zone (CGFZ) between April and June 2005. It appeared to "hitch a ride" on prevailing currents, with erratic movements indicative of feeding behavior in five areas, in particular the CGFZ, an area of known high sei whale abundance as well as high copepod concentrations. Seven whales tagged off Faial and Pico from May to June in 2008 and 2009 made their way to the Labrador Sea, while an eighth individual tagged in September 2009 headed southeast – its signal was lost between Madeira

)

, anthem = ( en, "Anthem of the Autonomous Region of Madeira")

, song_type = Regional anthem

, image_map=EU-Portugal_with_Madeira_circled.svg

, map_alt=Location of Madeira

, map_caption=Location of Madeira

, subdivision_type=Sovereign st ...

and the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; es, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to the African mainland, they are west of Mo ...

.

Whaling

The development of explosiveharpoon

A harpoon is a long spear-like instrument and tool used in fishing, whaling, sealing, and other marine hunting to catch and injure large fish or marine mammals such as seals and whales. It accomplishes this task by impaling the target animal ...

s and steam-powered whaling ships in the late nineteenth century brought previously unobtainable large whales within reach of commercial whalers. Initially their speed and elusiveness, and later the comparatively small yield of oil and meat partially protected them. Once stocks of more profitable right whale

Right whales are three species of large baleen whales of the genus ''Eubalaena'': the North Atlantic right whale (''E. glacialis''), the North Pacific right whale (''E. japonica'') and the Southern right whale (''E. australis''). They are clas ...

s, blue whales, fin whales, and humpback whales became depleted, sei whales were hunted in earnest, particularly from 1950 to 1980.

North Atlantic

In the North Atlantic between 1885 and 1984, 14,295 sei whales were taken. They were hunted in large numbers off the coasts of Norway and Scotland beginning in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and in 1885 alone, more than 700 were caught off

In the North Atlantic between 1885 and 1984, 14,295 sei whales were taken. They were hunted in large numbers off the coasts of Norway and Scotland beginning in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and in 1885 alone, more than 700 were caught off Finnmark

Finnmark (; se, Finnmárku ; fkv, Finmarku; fi, Ruija ; russian: Финнмарк) was a county in the northern part of Norway, and it is scheduled to become a county again in 2024.

On 1 January 2020, Finnmark was merged with the neighbouri ...

. Their meat was a popular Norwegian food. The meat's value made the hunting of this difficult-to-catch species profitable in the early twentieth century.

In Iceland, a total of 2,574 whales were taken from the Hvalfjörður

Hvalfjörður (, "whale fjord") is situated in the west of Iceland between Mosfellsbær and Akranes. The fjord is approximately 30 km long and 5 km wide.

The origin of the name Hvalfjörður is uncertain. Certainly today there is no ...

whaling station between 1948 and 1985. Since the late 1960s to early 1970s, the sei whale has been second only to the fin whale as the preferred target of Icelandic whalers, with meat in greater demand than whale oil

Whale oil is oil obtained from the blubber of whales. Whale oil from the bowhead whale was sometimes known as train oil, which comes from the Dutch word ''traan'' (" tear" or "drop").

Sperm oil, a special kind of oil obtained from the hea ...

, the prior target.

Small numbers were taken off the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

, beginning in the 1920s by Spanish whalers, off the Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native En ...

n shelf in the late 1960s and early 1970s by Canadian whalers, and off the coast of West Greenland from the 1920s to the 1950s by Norwegian and Danish whalers.

North Pacific

In the North Pacific, the total reported catch by commercial whalers was 72,215 between 1910 and 1975; the majority were taken after 1947. Shore stations in Japan andKorea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republi ...

processed 300–600 each year between 1911 and 1955. In 1959, the Japanese catch peaked at 1,340. Heavy exploitation in the North Pacific began in the early 1960s, with catches averaging 3,643 per year from 1963 to 1974 (total 43,719; annual range 1,280–6,053). In 1971, after a decade of high catches, it became scarce in Japanese waters, ending commercial whaling in 1975.

Off the coast of North America, sei whales were hunted off British Columbia from the late 1950s to the mid-1960s, when the number of whales captured dropped to around 14 per year. More than 2,000 were caught in British Columbian waters between 1962 and 1967. Between 1957 and 1971, California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the ...

shore stations processed 386 whales. Commercial Sei whaling ended in the eastern North Pacific in 1971.

Southern Hemisphere

A total of 152,233 were taken in the Southern Hemisphere between 1910 and 1979. Whaling in southern oceans originally targeted humpback whales. By 1913, this species became rare, and the catch of fin and blue whales began to increase. As these species likewise became scarce, sei whale catches increased rapidly in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The catch peaked in 1964–65 at over 20,000 sei whales, but by 1976, this number had dropped to below 2,000 and commercial whaling for the species ended in 1977.Post-protection whaling

Since the moratorium on commercial whaling, some sei whales have been taken by Icelandic and Japanese whalers under the IWC's scientific research programme. Iceland carried out four years of scientific whaling between 1986 and 1989, killing up to 40 sei whales a year. The research is conducted by the Institute of Cetacean Research (ICR) inTokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and List of cities in Japan, largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, ...

, a privately funded, nonprofit institution. The main focus of the research is to examine what they eat and to assess the competition between whales and fisheries. Dr. Seiji Ohsumi, Director General of the ICR, said,

:"It is estimated that whales consume 3 to 5 times the amount of marine resources as are caught for human consumption, so our whale research is providing valuable information required for improving the management of all our marine resources."

He later added,

:"Sei whales are the second-most abundant species of whale in the western North Pacific, with an estimated population of over 28,000 animals. t isclearly not endangered."

Conservation groups, such as the World Wildlife Fund

The World Wide Fund for Nature Inc. (WWF) is an international non-governmental organization founded in 1961 that works in the field of wilderness preservation and the reduction of human impact on the environment. It was formerly named the Wor ...

, dispute the value of this research, claiming that sei whales feed primarily on squid

True squid are molluscs with an elongated soft body, large eyes, eight arms, and two tentacles in the superorder Decapodiformes, though many other molluscs within the broader Neocoleoidea are also called squid despite not strictly fitting ...

and plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms found in water (or air) that are unable to propel themselves against a current (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are called plankters. In the ocean, they provide a cr ...

which are not hunted by humans, and only rarely on fish

Fish are aquatic, craniate, gill-bearing animals that lack limbs with digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and cartilaginous and bony fish as well as various extinct related groups. Approximately 95% ...

. They say that the program is

:"nothing more than a plan designed to keep the whaling fleet in business, and the need to use whales as the scapegoat for overfishing by humans."

At the 2001 meeting of the IWC Scientific Committee, 32 scientists submitted a document expressing their belief that the Japanese program lacked scientific rigor and would not meet minimum standards of academic review.

In 2010, a Los Angeles exclusive Sushi restaurant confirmed to be serving sei whale meat was closed by its owners after a covert investigation and protests lead to prosecution by authorities for handling an endangered/protected species.

Conservation status

International Whaling Commission

The International Whaling Commission (IWC) is a specialised regional fishery management organisation, established under the terms of the 1946 International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (ICRW) to "provide for the proper conservation ...

first set catch quotas for the North Pacific for individual species. Before quotas, there were no legal limits. Complete protection from commercial whaling in the North Pacific came in 1976.

Quotas on sei whales in the North Atlantic began in 1977. Southern Hemisphere stocks were protected in 1979. Facing mounting evidence that several whale species were threatened with extinction, the IWC established a complete moratorium on commercial whaling beginning in 1986.

In the late 1970s, some "pirate" whaling took place in the eastern North Atlantic. There is no direct evidence of illegal whaling in the North Pacific, although the acknowledged misreporting of whaling data by the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

means that catch data are not entirely reliable.

The species remained listed on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, also known as the IUCN Red List or Red Data Book, founded in 1964, is the world's most comprehensive inventory of the global conservation status of biolog ...

in 2000, categorized as "endangered". Northern Hemisphere populations are listed as CITES

CITES (shorter name for the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, also known as the Washington Convention) is a multilateral treaty to protect endangered plants and animals from the threats of interna ...

Appendix II, indicating they are not immediately threatened with extinction, but may become so if they are not listed. Populations in the Southern Hemisphere are listed as CITES

CITES (shorter name for the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, also known as the Washington Convention) is a multilateral treaty to protect endangered plants and animals from the threats of interna ...

Appendix I, indicating they are threatened with extinction if trade is not halted.

The sei whale is listed on both Appendix IAppendix I and Appendix II" of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). As amended by the Conference of the Parties in 1985, 1988, 1991, 1994, 1997, 1999, 2002, 2005 and 2008. Effective: 5 March 2009. and Appendix II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals ( CMS). It is listed on Appendix I as this species has been categorized as being in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant proportion of their range and CMS parties strive towards strictly protecting these animals, conserving or restoring the places where they live, mitigating obstacles to migration and controlling other factors that might endanger them and also on Appendix II as it has an unfavourable conservation status or would benefit significantly from international co-operation organised by tailored agreements. Sei whale is covered by the Memorandum of Understanding for the Conservation of Cetaceans and Their Habitats in the Pacific Islands Region ( Pacific Cetaceans MOU) and the Agreement on the Conservation of Small Cetaceans of the Baltic, North East Atlantic, Irish and North Seas ( ASCOBAMS). The species is listed as endangered by the U.S. government

National Marine Fisheries Service

The National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), informally known as NOAA Fisheries, is a United States federal agency within the U.S. Department of Commerce's National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) that is responsible for the ste ...

under the U.S. Endangered Species Act.

Population estimates

The current population is estimated at 80,000, nearly a third of the prewhaling population. A 1991 study in the North Atlantic estimated only 4,000. Sei whales were said to have been scarce in the 1960s and early 1970s off northern Norway. One possible explanation for this disappearance is that the whales were overexploited. The drastic reduction in northeastern Atlanticcopepod

Copepods (; meaning "oar-feet") are a group of small crustaceans found in nearly every freshwater and saltwater habitat. Some species are planktonic (inhabiting sea waters), some are benthic (living on the ocean floor), a number of species have p ...

stocks during the late 1960s may be another culprit. Surveys in the Denmark Strait found 1,290 whales in 1987, and 1,590 whales in 1989. Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native En ...

's population estimates are between 1,393 and 2,248, with a minimum of 870.

A 1977 study estimated Pacific Ocean totals of 9,110, based upon catch and CPUE In fishery, fisheries and conservation biology, the catch per unit effort (CPUE) is an Proxy (statistics), indirect measure of the Abundance (ecology), abundance of a target species. Changes in the catch per unit effort are inferred to signify chang ...

data. Japanese interests claim this figure is outdated, and in 2002 claimed the western North Pacific population was over 28,000, a figure not accepted by the scientific community. In western Canadian waters, researchers with Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO; french: Pêches et Océans Canada, MPO), is a Ministry (government department), department of the Government of Canada that is responsible for developing and implementing policies and programs in support of Can ...

observed five Seis together in the summer of 2017, the first such sighting in over 50 years. In California waters, there was only one confirmed and five possible sightings by 1991 to 1993 aerial and ship surveys, and there were no confirmed sightings off Oregon coasts such as Maumee Bay and Washington. Prior to commercial whaling, the North Pacific hosted an estimated 42,000. By the end of whaling, the population was down to between 7,260 and 12,620.

In the Southern Hemisphere, population estimates range between 9,800 and 12,000, based upon catch history and CPUE. The IWC estimated 9,718 whales based upon survey data between 1978 and 1988. Prior to commercial whaling, there were an estimated 65,000.

Mass deaths

Mass death events for sei whales have been recorded for many years and evidence suggests endemic poisoning (red tide

A harmful algal bloom (HAB) (or excessive algae growth) is an algal bloom that causes negative impacts to other organisms by production of natural phycotoxin, algae-produced toxins, mechanical damage to other organisms, or by other means. HABs are ...

) causes may have caused mass deaths in prehistoric times. In June 2015, scientists flying over southern Chile counted 337 dead sei whales, in what is regarded as the largest mass beaching ever documented. The cause is not yet known; however, toxic algae blooms caused by unprecedented warming in the Pacific Ocean, known as the Blob, may be implicated.

See also

* List of cetaceans *Marine biology

Marine biology is the scientific study of the biology of marine life, organisms in the sea. Given that in biology many phyla, families and genera have some species that live in the sea and others that live on land, marine biology classifie ...

* Pacific Islands Cetaceans Memorandum of Understanding

* ''HMS Daedalus'' (1826)

References

Further reading

*''National Audubon Society Guide to Marine Mammals of the World'', Reeves, Stewart, Clapham and Powell, 2002, * Eds. C. Michael Hogan and C.J.Cleveland''Sei whale''. Encyclopedia of Earth, National Council for Science and Environment; content partner Encyclopedia of Life

*''Whales & Dolphins Guide to the Biology and Behaviour of Cetaceans'', Maurizio Wurtz and Nadia Repetto. *''Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals'', editors Perrin, Wursig and Thewissen, *''Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises'', Carwardine (1995, reprinted 2000), *

External links

*ARKive �

images and movies of the sei whale ''(Balaenoptera borealis)''

{{Authority control Cetaceans of the Arctic Ocean Baleen whales Mammals of Japan Cetaceans of the Indian Ocean Cetaceans of the Atlantic Ocean Cetaceans of the Pacific Ocean Mammals described in 1828 ESA endangered species