Second Italo-Ethiopian War on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Second Italo-Ethiopian War, also referred to as the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, was a

''Between bombs and good intentions: the Red Cross and the Italo-Ethiopian War, 1935–1936''

Berghahn Books. 2006 pp. 239, 131–132 By all estimates, hundreds of thousands of Ethiopian civilians died as a result of the Italian invasion, which have been described by some historians as constituting

The

The

File:Haile Selassie in full dress (cropped).jpg,

There were 400,000 Italian soldiers in Eritrea and 285,000 in Italian Somaliland with 3,300 machine guns, 275 artillery pieces, 200

There were 400,000 Italian soldiers in Eritrea and 285,000 in Italian Somaliland with 3,300 machine guns, 275 artillery pieces, 200

File:Benito Mussolini Portrait.jpg,

At 5:00 am on 3 October 1935, De Bono crossed the Mareb River and advanced into Ethiopia from Eritrea without a declaration of war. Aircraft of the ''Regia Aeronautica'' scattered leaflets asking the population to rebel against Haile Selassie and support the "true Emperor

At 5:00 am on 3 October 1935, De Bono crossed the Mareb River and advanced into Ethiopia from Eritrea without a declaration of war. Aircraft of the ''Regia Aeronautica'' scattered leaflets asking the population to rebel against Haile Selassie and support the "true Emperor

The Christmas Offensive was intended to split the Italian forces in the north with the Ethiopian centre, crushing the Italian left with the Ethiopian right and to invade Eritrea with the Ethiopian left. ''Ras'' Seyum Mangasha held the area around

The Christmas Offensive was intended to split the Italian forces in the north with the Ethiopian centre, crushing the Italian left with the Ethiopian right and to invade Eritrea with the Ethiopian left. ''Ras'' Seyum Mangasha held the area around

On 31 March 1936 at the

On 31 March 1936 at the

On 3 October 1935, Graziani implemented the Milan Plan to remove Ethiopian forces from various frontier posts and to test the reaction to a series of probes all along the southern front. While incessant rains worked to hinder the plan, within three weeks the Somali villages of

On 3 October 1935, Graziani implemented the Milan Plan to remove Ethiopian forces from various frontier posts and to test the reaction to a series of probes all along the southern front. While incessant rains worked to hinder the plan, within three weeks the Somali villages of

On 26 April 1936, Badoglio began the "March of the Iron Will" from Dessie to Addis Ababa, an advance with a mechanised column against slight Ethiopian resistance. The column experienced a more serious attack on 4 May when Ethiopian forces under Haile Mariam Mammo ambushed the formation in Chacha, near

On 26 April 1936, Badoglio began the "March of the Iron Will" from Dessie to Addis Ababa, an advance with a mechanised column against slight Ethiopian resistance. The column experienced a more serious attack on 4 May when Ethiopian forces under Haile Mariam Mammo ambushed the formation in Chacha, near

After the occupation of Addis Ababa, nearly half of Ethiopia was still unoccupied and the fighting continued for another three years until nearly 90% was "pacified" just before

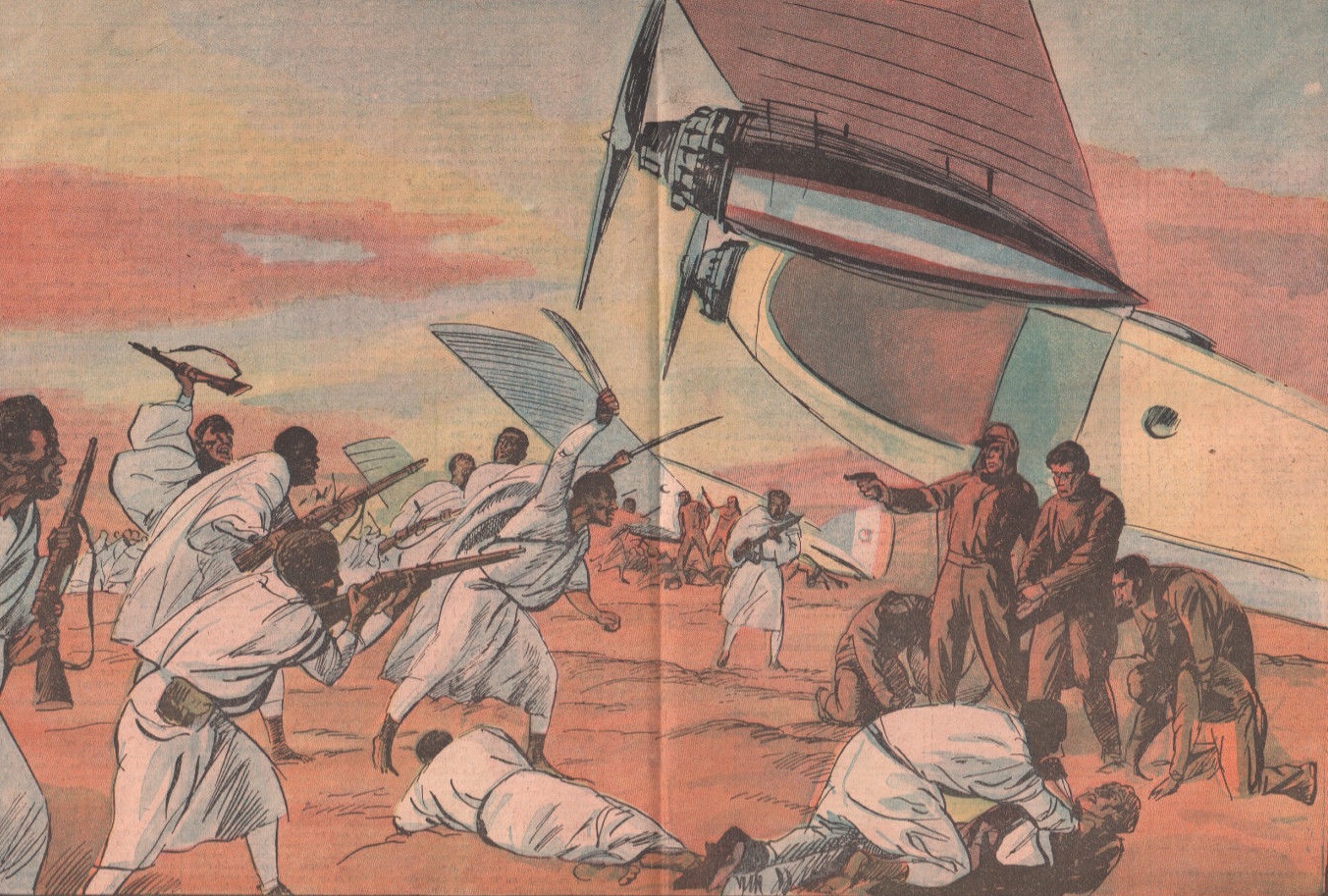

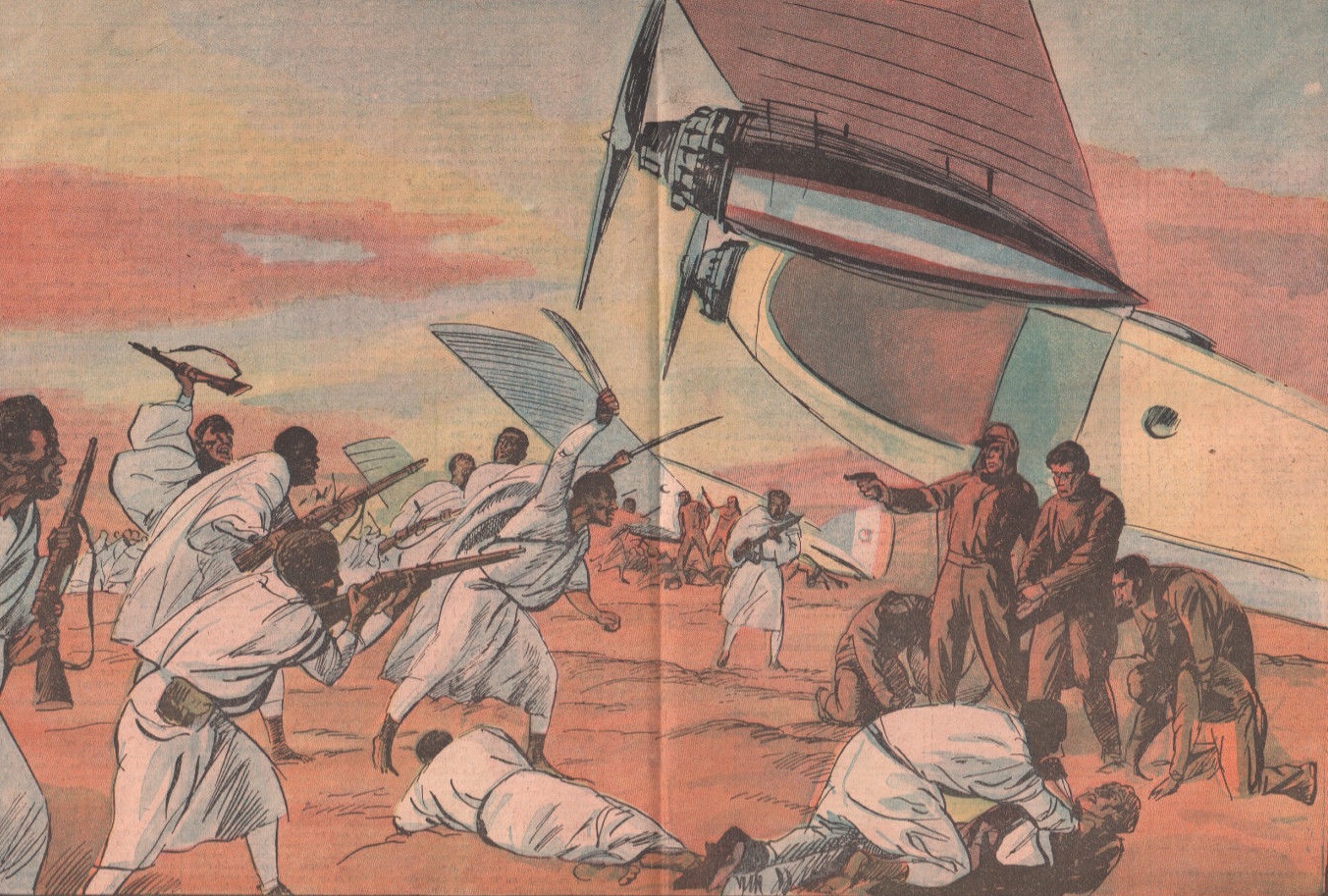

After the occupation of Addis Ababa, nearly half of Ethiopia was still unoccupied and the fighting continued for another three years until nearly 90% was "pacified" just before  On the night 26 June, members of the Black Lions organization destroyed three Italian aircraft in Nekemte and killed twelve Italian officials, including Air Marshal Vincenzo Magliocco after the Italians had sent the party to parley with the local populace. Graziani ordered the town to be bombed in retaliation for the killings (Magliocco was his deputy). Local hostility forced out the Patriots and Desta Damtew, commander of the southern Patriots, withdrew his troops to Arbegona. Surrounded by Italian forces, they retreated to

On the night 26 June, members of the Black Lions organization destroyed three Italian aircraft in Nekemte and killed twelve Italian officials, including Air Marshal Vincenzo Magliocco after the Italians had sent the party to parley with the local populace. Graziani ordered the town to be bombed in retaliation for the killings (Magliocco was his deputy). Local hostility forced out the Patriots and Desta Damtew, commander of the southern Patriots, withdrew his troops to Arbegona. Surrounded by Italian forces, they retreated to

''Haile Selassie's War''

pp. 163 – 169 Hours later, Cortese gave the fatal order:

Italy's military victory overshadowed concerns about the economy. Mussolini was at the height of his popularity in May 1936 with the proclamation of the Italian empire. His biographer,

Italy's military victory overshadowed concerns about the economy. Mussolini was at the height of his popularity in May 1936 with the proclamation of the Italian empire. His biographer,  Haile Selassie sailed from Djibouti in the British cruiser . From

Haile Selassie sailed from Djibouti in the British cruiser . From

On 10 May 1936, Italian troops from the northern front and from the southern front met at Dire Dawa. The Italians found the recently released Ethiopian Ras, Hailu Tekle Haymanot, who boarded a train back to Addis Ababa and approached the Italian invaders in submission. On 21 December 1937, Rome appointed

On 10 May 1936, Italian troops from the northern front and from the southern front met at Dire Dawa. The Italians found the recently released Ethiopian Ras, Hailu Tekle Haymanot, who boarded a train back to Addis Ababa and approached the Italian invaders in submission. On 21 December 1937, Rome appointed  The army of occupation had 150,000 men but was spread thinly; by 1941 the garrison had been increased to 250,000 soldiers, including 75,000 Italian civilians. The former police chief of Addis Ababa, Abebe Aregai, was the most successful leader of the Ethiopian guerrilla movement after 1937, using units of fifty men. On 11 December, the

The army of occupation had 150,000 men but was spread thinly; by 1941 the garrison had been increased to 250,000 soldiers, including 75,000 Italian civilians. The former police chief of Addis Ababa, Abebe Aregai, was the most successful leader of the Ethiopian guerrilla movement after 1937, using units of fifty men. On 11 December, the

While in exile in United Kingdom, Haile Selassie had sought the support of the Western democracies for his cause but had little success until the Second World War began. On 10 June 1940, Mussolini declared war on France and Britain and attacked British and

While in exile in United Kingdom, Haile Selassie had sought the support of the Western democracies for his cause but had little success until the Second World War began. On 10 June 1940, Mussolini declared war on France and Britain and attacked British and

Speech to the League of Nations, June 1936

(full text)

British newsreel footage of Haile Selassie's address to the League of Nations

Ethiopia 1935–36: mustard gas and attacks on the Red CrossFull version in French

– Bernard Bridel, ''

The use of chemical weapons in the 1935–36 Italo-Ethiopian War

– SIPRI Arms Control and Non-proliferation Programme, October 2009

* The Emperor Leaves Ethiopia

Ascari: I Leoni di Eritrea/Ascari: The Lions of Eritrea.

Second Italo-Abyssinian war. Eritrea colonial history, Eritrean ascari pictures/photos galleries and videos, historical atlas...

Ross, F. 1937. The Strategical Conduct of the Campaign and supply and Evacuation Programmes

*

Songs of 2nd Italo-Abyssinian War

{{Authority control 1935 in Ethiopia 1935 in Italy 1936 in Ethiopia 1936 in Italy Conflicts in 1935 Conflicts in 1936 Italo-Ethiopian War, Second Haile Selassie Italo-Ethiopian War, Second Italo-Ethiopian War, Second Italo-Ethiopian War, Second Italo-Ethiopian War, Second Italo-Ethiopian War, Second African resistance to colonialism Interwar period

war of aggression

A war of aggression, sometimes also war of conquest, is a military conflict waged without the justification of self-defense, usually for territorial gain and subjugation.

Wars without international legality (i.e. not out of self-defense nor san ...

which was fought between Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

and Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the Er ...

from October 1935 to February 1937. In Ethiopia it is often referred to simply as the Italian Invasion ( am, ጣልያን ወረራ), and in Italy as the Ethiopian War ( it, Guerra d'Etiopia). It is seen as an example of the expansionist policy that characterized the Axis powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

and the ineffectiveness of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide Intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by ...

before the outbreak of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

.

On 3 October 1935, two hundred thousand soldiers of the Italian Army commanded by Marshal Emilio De Bono attacked from Eritrea

Eritrea ( ; ti, ኤርትራ, Ertra, ; ar, إرتريا, ʾIritriyā), officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the Horn of Africa region of Eastern Africa, with its capital and largest city at Asmara. It is bordered by Ethiopia ...

(then an Italian colonial possession) without prior declaration of war. At the same time a minor force under General Rodolfo Graziani

Rodolfo Graziani, 1st Marquis of Neghelli (; 11 August 1882 – 11 January 1955), was a prominent Italian military officer in the Kingdom of Italy's ''Regio Esercito'' ("Royal Army"), primarily noted for his campaigns in Africa before and during ...

attacked from Italian Somalia

Italian Somalia ( it, Somalia Italiana; ar, الصومال الإيطالي, Al-Sumal Al-Italiy; so, Dhulka Talyaaniga ee Soomaalida), was a protectorate and later colony of the Kingdom of Italy in present-day Somalia. Ruled in the 19th centur ...

. On 6 October, Adwa

Adwa ( ti, ዓድዋ; amh, ዐድዋ; also spelled Aduwa) is a town and separate woreda in Tigray Region, Ethiopia. It is best known as the community closest to the site of the 1896 Battle of Adwa, in which Ethiopian soldiers defeated Ital ...

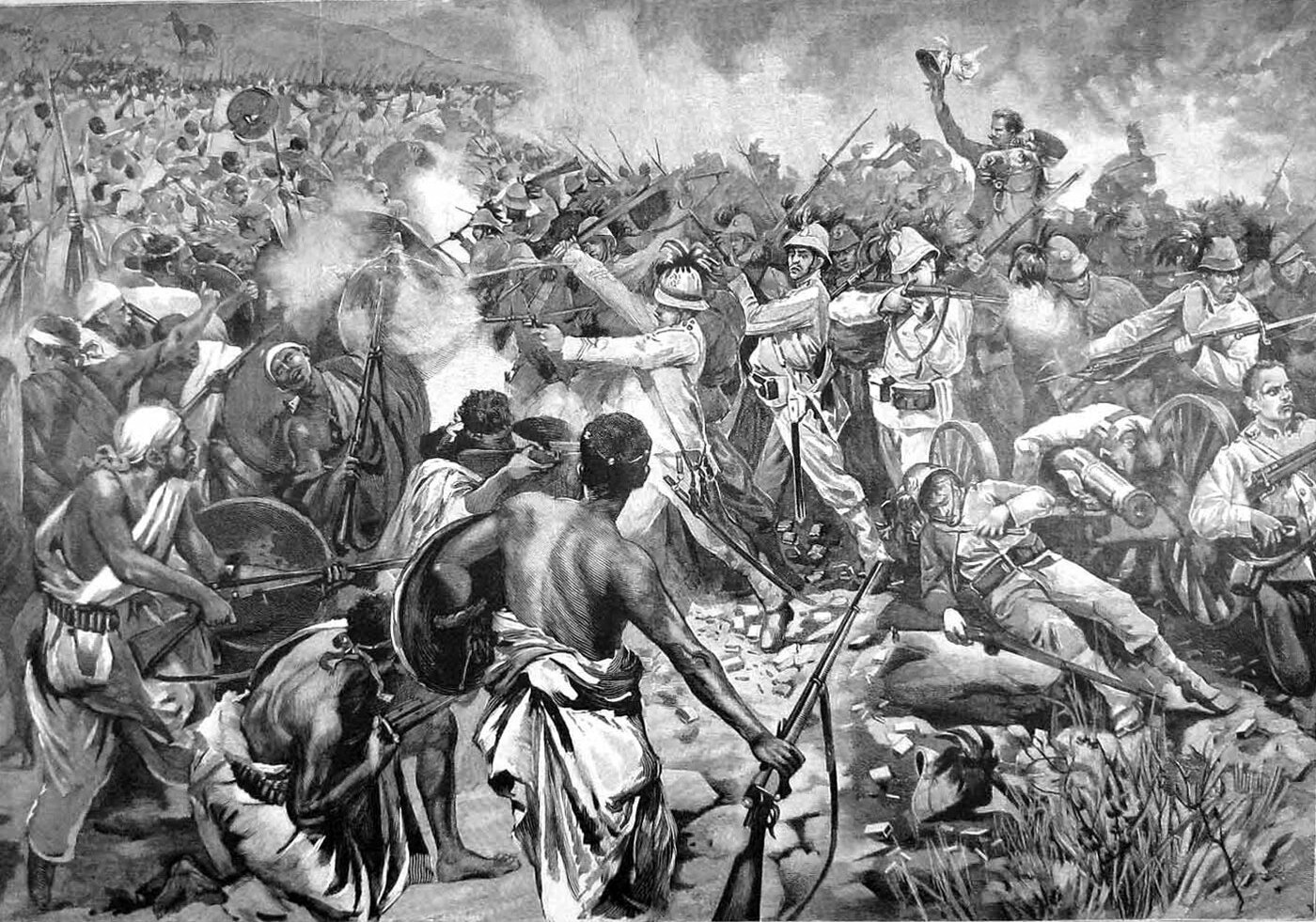

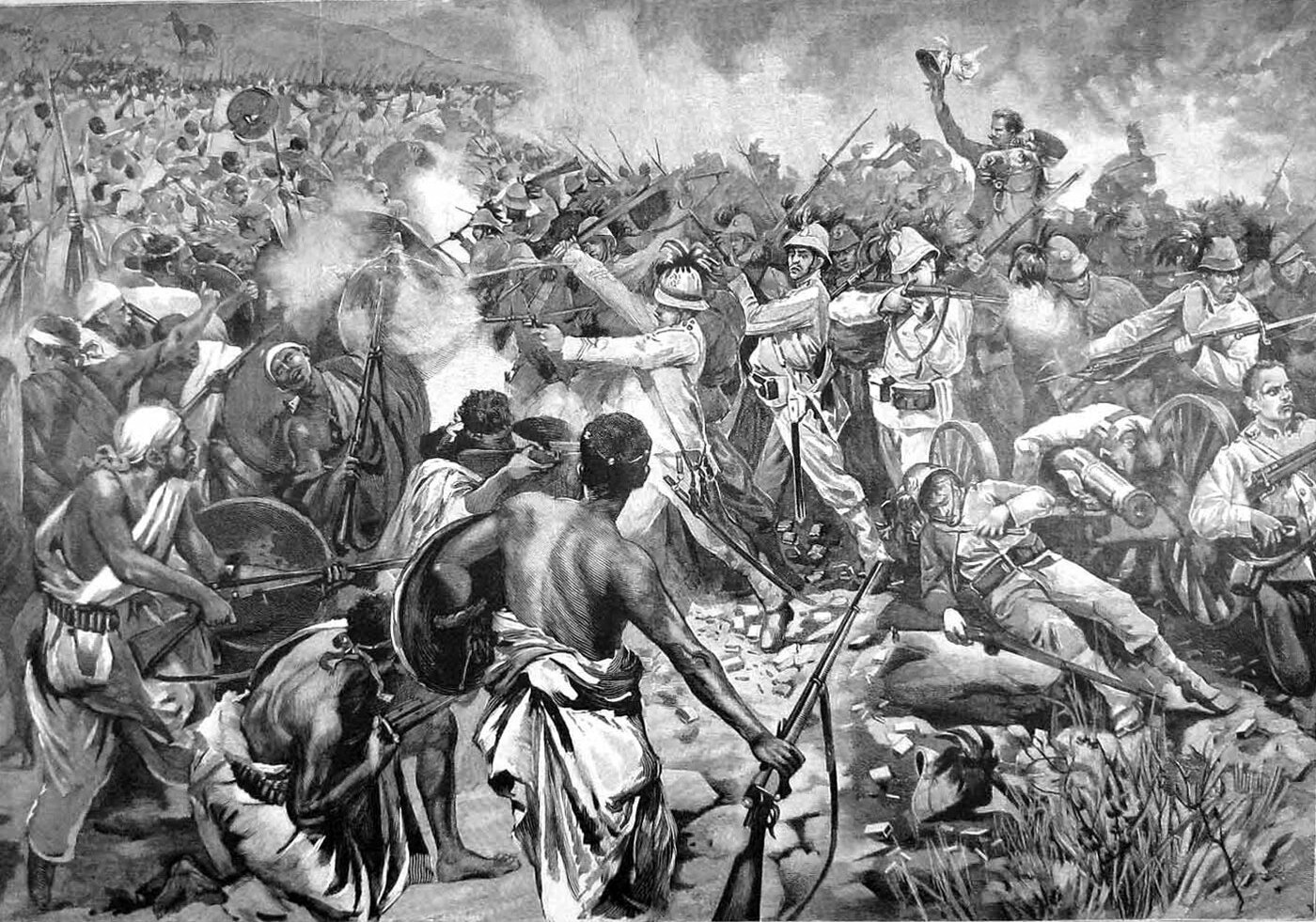

was conquered, a symbolic place for the Italian army because of the defeat at the Battle of Adwa

The Battle of Adwa (; ti, ውግእ ዓድዋ; , also spelled ''Adowa'') was the climactic battle of the First Italo-Ethiopian War. The Ethiopian forces defeated the Italian invading force on Sunday 1 March 1896, near the town of Adwa. The d ...

by the Ethiopian army during the First Italo-Ethiopian War

The First Italo-Ethiopian War, lit. ''Abyssinian War'' was fought between Italy and Ethiopia from 1895 to 1896. It originated from the disputed Treaty of Wuchale, which the Italians claimed turned Ethiopia into an Italian protectorate. Full-s ...

. On 15 October, Italian troops seized Aksum

Axum, or Aksum (pronounced: ), is a town in the Tigray Region of Ethiopia with a population of 66,900 residents (as of 2015).

It is the site of the historic capital of the Aksumite Empire, a naval and trading power that ruled the whole region ...

, and an obelisk

An obelisk (; from grc, ὀβελίσκος ; diminutive of ''obelos'', " spit, nail, pointed pillar") is a tall, four-sided, narrow tapering monument which ends in a pyramid-like shape or pyramidion at the top. Originally constructed by An ...

adorning the city was torn from its site and sent to Rome to be placed symbolically in front of the building of the Ministry of Colonies created by the Fascist regime

Fascism is a far-right, Authoritarianism, authoritarian, ultranationalism, ultra-nationalist political Political ideology, ideology and Political movement, movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and pol ...

.

Exasperated by De Bono's slow and cautious progress, Italian Prime Minister Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

replaced him with General Pietro Badoglio

Pietro Badoglio, 1st Duke of Addis Abeba, 1st Marquess of Sabotino (, ; 28 September 1871 – 1 November 1956), was an Italian general during both World Wars and the first viceroy of Italian East Africa. With the fall of the Fascist regime ...

. Ethiopian forces attacked the newly arrived invading army and launched a counterattack

A counterattack is a tactic employed in response to an attack, with the term originating in " war games". The general objective is to negate or thwart the advantage gained by the enemy during attack, while the specific objectives typically see ...

in December 1935, but their poorly armed forces could not resist for long against the modern weapons of the Italians. Even the communications service of the Ethiopian forces depended on foot messengers, as they did not have radio. This was enough for the Italians to impose a narrow fence on Ethiopian detachments to leave them unaware of the movements of their own army. Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

sent arms and munitions to Ethiopia because it was frustrated over Italian objections to its attempts to integrate Austria. This prolonged the war and sapped Italian resources. It would soon lead to Italy's greater economic dependence on Germany and less interventionist policy on Austria, clearing the path for Hitler's ''Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, en, Annexation of Austria), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into the Nazi Germany, German Reich on 13 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a "Ger ...

''.

The Ethiopian counteroffensive managed to stop the Italian advance for a few weeks, but the superiority of the Italians' weapons (particularly heavy artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during sieg ...

and airstrikes with bombs and chemical weapons

A chemical weapon (CW) is a specialized munition that uses chemicals formulated to inflict death or harm on humans. According to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), this can be any chemical compound intended as ...

) prevented the Ethiopians from taking advantage of their initial successes. The Italians resumed the offensive in early March. On 29 March 1936, Graziani bombed the city of Harar

Harar ( amh, ሐረር; Harari: ሀረር; om, Adare Biyyo; so, Herer; ar, هرر) known historically by the indigenous as Gey (Harari: ጌይ ''Gēy'', ) is a walled city in eastern Ethiopia. It is also known in Arabic as the City of Sain ...

and two days later the Italians won a decisive victory in the Battle of Maychew

The Battle of Maychew ( it, Mai Ceu) was the last major battle fought on the northern front during the Second Italo-Abyssinian War. The battle consisted of a failed counterattack by the Ethiopian forces under Emperor Haile Selassie making fro ...

, which nullified any possible organized resistance of the Ethiopians. Emperor Haile Selassie

Haile Selassie I ( gez, ቀዳማዊ ኀይለ ሥላሴ, Qädamawi Häylä Səllasé, ; born Tafari Makonnen; 23 July 189227 August 1975) was Emperor of Ethiopia from 1930 to 1974. He rose to power as Regent Plenipotentiary of Ethiopia (' ...

was forced to escape into exile on 2 May, and Badoglio's forces arrived in the capital Addis Ababa

Addis Ababa (; am, አዲስ አበባ, , new flower ; also known as , lit. "natural spring" in Oromo), is the capital and largest city of Ethiopia. It is also served as major administrative center of the Oromia Region. In the 2007 census, ...

on 5 May. Italy announced the annexation of the territory of Ethiopia on 7 May and Italian King Victor Emmanuel III

The name Victor or Viktor may refer to:

* Victor (name), including a list of people with the given name, mononym, or surname

Arts and entertainment

Film

* ''Victor'' (1951 film), a French drama film

* ''Victor'' (1993 film), a French shor ...

was proclaimed emperor. The provinces of Eritrea, Italian Somaliland and Abyssinia (Ethiopia) were united to form the Italian province of East Africa. Fighting between Italian and Ethiopian troops persisted until 19 February 1937. On the same day, an attempted assassination of Graziani led to the reprisal Yekatit 12

Yekatit 12 () is a date in the Ge'ez calendar which refers to the massacre and imprisonment of Ethiopians by the Kingdom of Italy, Italian occupation forces following an attempted assassination of Marshal Rodolfo Graziani, Rodolfo Graziani, Marqu ...

massacre in Addis Ababa, in which between 1,400 and 30,000 civilians were killed. Italian forces continued to suppress rebel activity until 1939.

Italian troops used mustard gas

Mustard gas or sulfur mustard is a chemical compound belonging to a family of cytotoxic and blister agents known as mustard agents. The name ''mustard gas'' is technically incorrect: the substance, when dispersed, is often not actually a gas, b ...

in aerial bombardments (in violation of the Geneva Protocol

The Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use in War of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare, usually called the Geneva Protocol, is a treaty prohibiting the use of chemical and biological weapons in ...

and Geneva Conventions

upright=1.15, Original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are four treaties, and three additional protocols, that establish international legal standards for humanitarian treatment in war. The singular term ''Geneva Conv ...

) against combatants and civilians in an attempt to discourage the Ethiopian people from supporting the resistance. Deliberate Italian attacks against ambulances and hospitals of the Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million Volunteering, volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure re ...

were reported.Rainer Baudendistel''Between bombs and good intentions: the Red Cross and the Italo-Ethiopian War, 1935–1936''

Berghahn Books. 2006 pp. 239, 131–132 By all estimates, hundreds of thousands of Ethiopian civilians died as a result of the Italian invasion, which have been described by some historians as constituting

genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the L ...

. Crimes by Ethiopian troops included the use of dumdum bullets

Expanding bullets, also known colloquially as dumdum bullets, are projectiles designed to expand on impact. This causes the bullet to increase in diameter, to combat over-penetration and produce a larger wound, thus dealing more damage to a liv ...

(in violation of the Hague Conventions), the killing of civilian workmen (including during the Gondrand massacre

The Gondrand massacre was a 1936 Ethiopian attack on Italian workers of the Gondrand company. It was publicized by Fascist Italy in an attempt to justify its ongoing conquest of Ethiopia.

History

The Gondrand massacre occurred on February 13, ...

) and the mutilation of captured Eritrean Ascari and Italians (often with castration), beginning in the first weeks of war.

Background

State of East Africa

The

The Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia was proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to an institutional referendum to abandon the monarchy and ...

began its attempts to establish colonies in the Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa (HoA), also known as the Somali Peninsula, is a large peninsula and geopolitical region in East Africa.Robert Stock, ''Africa South of the Sahara, Second Edition: A Geographical Interpretation'', (The Guilford Press; 2004), ...

in the 1880s. The first phase of the colonial expansion concluded with the disastrous First Italo-Ethiopian War

The First Italo-Ethiopian War, lit. ''Abyssinian War'' was fought between Italy and Ethiopia from 1895 to 1896. It originated from the disputed Treaty of Wuchale, which the Italians claimed turned Ethiopia into an Italian protectorate. Full-s ...

and the defeat of the Italian forces in the Battle of Adwa

The Battle of Adwa (; ti, ውግእ ዓድዋ; , also spelled ''Adowa'') was the climactic battle of the First Italo-Ethiopian War. The Ethiopian forces defeated the Italian invading force on Sunday 1 March 1896, near the town of Adwa. The d ...

, on 1 March 1896, inflicted by the Ethiopian Army of Negus

Negus (Negeuce, Negoose) ( gez, ንጉሥ, ' ; cf. ti, ነጋሲ ' ) is a title in the Ethiopian Semitic languages. It denotes a monarch,

Menelik II

, spoken = ; ''djānhoi'', lit. ''"O steemedroyal"''

, alternative = ; ''getochu'', lit. ''"Our master"'' (pl.)

Menelik II ( gez, ዳግማዊ ምኒልክ ; horse name Abba Dagnew ( Amharic: አባ ዳኘው ''abba daññäw''); 17 ...

, aided by Russia and France. In the following years, Italy abandoned its expansionist plans in the area and limited itself to administering the small possessions that it retained in there: the colony of Italian Eritrea

Italian Eritrea ( it, Colonia Eritrea, "Colony of Eritrea") was a colony of the Kingdom of Italy in the territory of present-day Eritrea. The first Italian establishment in the area was the purchase of Assab by the Rubattino Shipping Company in 1 ...

and the protectorate (later colony) of Italian Somalia

Italian Somalia ( it, Somalia Italiana; ar, الصومال الإيطالي, Al-Sumal Al-Italiy; so, Dhulka Talyaaniga ee Soomaalida), was a protectorate and later colony of the Kingdom of Italy in present-day Somalia. Ruled in the 19th centur ...

. For the next few decades, Italian-Ethiopian economic and diplomatic relations remained relatively stable.

On 14 December 1925, Italy's fascist government signed a secret pact with Britain aimed at reinforcing Italian dominance in the region. London recognised that the area was of Italian interest and agreed to the Italian request to build a railway connecting Somalia and Eritrea. Although the signatories had wished to maintain the secrecy of the agreement, the plan soon leaked and caused indignation by the French and Ethiopian governments. The latter denounced it as a betrayal of a country that had been for all intents and purposes a member of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide Intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by ...

.

As fascist rule in Italy continued to radicalise, its colonial governors in the Horn of Africa began pushing outward the margins of their imperial foothold. The governor of Italian Eritrea, Jacopo Gasparini Jacopo (also Iacopo) is a masculine Italian given name, derivant from Latin ''Iacōbus''. It is an Italian variant of Giacomo.

* Jacopo Aconcio (), Italian religious reformer

* Jacopo Bassano (1592), Italian painter

* Iacopo Barsotti (1921–19 ...

, focused on the exploitation of Teseney and an attempt to win over the leaders of the Tigre people

The Tigre people ( tig, ትግረ ''tigre'' or ''tigrē'') are an ethnic group indigenous to Eritrea. They mainly inhabit the lowlands and northern highlands of Eritrea.

History

The Tigre are a nomadic agro-pastoralist community living in ...

against Ethiopia. The governor of Italian Somaliland, Cesare Maria de Vecchi, began a policy of repression that led to the occupation of the fertile Jubaland

Jubaland ( so, Jubbaland, ar, , it, Oltregiuba), the Juba Valley ( so, Dooxada Jubba) or Azania ( so, Asaaniya, ar, ), is a Federal Member State in southern Somalia. Its eastern border lies east of the Jubba River, stretching from Gedo ...

, and the cessation in 1928 of collaboration between the settlers and the traditional Somali chiefs.

Welwel Incident

The Italo-Ethiopian Treaty of 1928 stated that the border betweenItalian Somaliland

Italian Somalia ( it, Somalia Italiana; ar, الصومال الإيطالي, Al-Sumal Al-Italiy; so, Dhulka Talyaaniga ee Soomaalida), was a protectorate and later colony of the Kingdom of Italy in present-day Somalia. Ruled in the 19th cent ...

and Ethiopia was 21 leagues parallel to the Benadir coast (approximately ). In 1930, Italy built a fort at the Welwel oasis (also ''Walwal'', Italian: ''Ual-Ual'') in the Ogaden

Ogaden (pronounced and often spelled ''Ogadēn''; so, Ogaadeen, am, ውጋዴ/ውጋዴን) is one of the historical names given to the modern Somali Region, the territory comprising the eastern portion of Ethiopia formerly part of the Harar ...

and garrisoned it with Somali dubats (irregular frontier troops commanded by Italian officers). The fort at Welwel was well beyond the 21-league limit and inside Ethiopian territory. On 23 November 1934, an Anglo–Ethiopian boundary commission studying grazing grounds to find a definitive border between British Somaliland and Ethiopia arrived at Welwel. The party contained Ethiopian and British technicians and an escort of around 600 Ethiopian soldiers. Both sides knew that the Italians had installed a military post at Welwel and were not surprised to see an Italian flag at the wells. The Ethiopian government had notified the Italian authorities in Italian Somaliland that the commission was active in the Ogaden and requested the Italians to co-operate. When the British commissioner Lieutenant-Colonel Esmond Clifford, asked the Italians for permission to camp nearby, the Italian commander, Captain Roberto Cimmaruta, rebuffed the request.

Fitorari Shiferra, the commander of the Ethiopian escort, took no notice of the and Somali troops and made camp. To avoid being caught in an Italian–Ethiopian incident, Clifford withdrew the British contingent to Ado, about to the north-east, and Italian aircraft began to fly over Welwel. The Ethiopian commissioners retired with the British, but the escort remained. For ten days both sides exchanged menaces, sometimes no more than 2 m apart. Reinforcements increased the Ethiopian contingent to about 1,500 men and the Italians to about 500, and on 5 December 1934, shots were fired. The Italians were supported by an armoured car and bomber aircraft. The bombs missed, but machine gunfire from the car caused about 110 Ethiopian casualties. Also, 30 to 50 Italians and Somalis were also killed and the incident led to the Abyssinia Crisis

The Abyssinia Crisis (; ) was an international crisis in 1935 that originated in what was called the Walwal incident during the ongoing conflict between the Kingdom of Italy and the Empire of Ethiopia (then commonly known as "Abyssinia"). The Le ...

at the League of Nations. On 4 September 1935, the League of Nations exonerated both parties for the incident.

Ethiopian isolation

Britain and France, preferring Italy as an ally against Germany, did not take strong steps to discourage an Italian military buildup on the borders ofItalian Eritrea

Italian Eritrea ( it, Colonia Eritrea, "Colony of Eritrea") was a colony of the Kingdom of Italy in the territory of present-day Eritrea. The first Italian establishment in the area was the purchase of Assab by the Rubattino Shipping Company in 1 ...

and Italian Somaliland

Italian Somalia ( it, Somalia Italiana; ar, الصومال الإيطالي, Al-Sumal Al-Italiy; so, Dhulka Talyaaniga ee Soomaalida), was a protectorate and later colony of the Kingdom of Italy in present-day Somalia. Ruled in the 19th cent ...

. Because of the German Question

The "German question" was a debate in the 19th century, especially during the Revolutions of 1848, over the best way to achieve a unification of all or most lands inhabited by Germans. From 1815 to 1866, about 37 independent German-speaking st ...

, Mussolini needed to deter Hitler from annexing Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

while much of the Italian Army was being deployed to the Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa (HoA), also known as the Somali Peninsula, is a large peninsula and geopolitical region in East Africa.Robert Stock, ''Africa South of the Sahara, Second Edition: A Geographical Interpretation'', (The Guilford Press; 2004), ...

, which led him to draw closer to France to provide the necessary deterrent. King Victor Emmanuel III

The name Victor or Viktor may refer to:

* Victor (name), including a list of people with the given name, mononym, or surname

Arts and entertainment

Film

* ''Victor'' (1951 film), a French drama film

* ''Victor'' (1993 film), a French shor ...

shared the traditional Italian respect for British sea power and insisted to Mussolini that Italy must not antagonise Britain before he assented to the war. In that regard, British diplomacy in the first half of 1935 greatly assisted Mussolini's efforts to win Victor Emmanuel's support for the invasion.

On 7 January 1935, a Franco-Italian Agreement was made that gave Italy essentially a free hand in Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

in return for Italian co-operation in Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located enti ...

. Pierre Laval

Pierre Jean Marie Laval (; 28 June 1883 – 15 October 1945) was a French politician. During the Third Republic, he served as Prime Minister of France from 27 January 1931 to 20 February 1932 and 7 June 1935 to 24 January 1936. He again occu ...

told Mussolini that he wanted a Franco-Italian alliance against Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and that Italy had a "free hand" in Ethiopia. In April, Italy was further emboldened by participation in the Stresa Front, an agreement to curb further German violations of the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1 ...

. The first draft of the communique at Stresa Summit spoke of upholding stability all over the world, but British Foreign Secretary, Sir John Simon

John Allsebrook Simon, 1st Viscount Simon, (28 February 1873 – 11 January 1954), was a British politician who held senior Cabinet posts from the beginning of the First World War to the end of the Second World War. He is one of only three peop ...

, insisted for the final draft to declare that Britain, France and Italy were committed to upholding stability "in Europe", which Mussolini took for British acceptance of an invasion of Ethiopia. In June, non-interference was further assured by a political rift, which had developed between the United Kingdom and France, because of the Anglo-German Naval Agreement

The Anglo-German Naval Agreement (AGNA) of 18 June 1935 was a naval agreement between the United Kingdom and Germany regulating the size of the ''Kriegsmarine'' in relation to the Royal Navy.

The Anglo-German Naval Agreement fixed a ratio whe ...

. As 300,000 Italian soldiers were transferred to Eritrea and Italian Somaliland over the spring and the summer of 1935, the world's media was abuzz with speculation that Italy would soon be invading Ethiopia. In June 1935, Anthony Eden

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon, (12 June 1897 – 14 January 1977) was a British Conservative Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1955 until his resignation in 1957.

Achieving rapid pro ...

arrived in Rome with the message that Britain opposed an invasion and had a compromise plan for Italy to be given a corridor in Ethiopia to link the two Italian colonies in the Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa (HoA), also known as the Somali Peninsula, is a large peninsula and geopolitical region in East Africa.Robert Stock, ''Africa South of the Sahara, Second Edition: A Geographical Interpretation'', (The Guilford Press; 2004), ...

, which Mussolini rejected outright. As the Italians had broken the British naval codes, Mussolini knew of the problems in the British Mediterranean Fleet, which led him to believe that the British opposition to the invasion, which had come as an unwelcome surprise to him, was not serious and that Britain would never go to war over Ethiopia.

The prospect that an Italian invasion of Ethiopia would cause a crisis in Anglo-Italian relations was seen as an opportunity in Berlin

Berlin is Capital of Germany, the capital and largest city of Germany, both by area and List of cities in Germany by population, by population. Its more than 3.85 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European U ...

. Germany provided some weapons to Ethiopia although Hitler did not want to see Haile Selassie

Haile Selassie I ( gez, ቀዳማዊ ኀይለ ሥላሴ, Qädamawi Häylä Səllasé, ; born Tafari Makonnen; 23 July 189227 August 1975) was Emperor of Ethiopia from 1930 to 1974. He rose to power as Regent Plenipotentiary of Ethiopia (' ...

win out of fear of quick victory for Italy. The German perspective was that if Italy was bogged down in a long war in Ethiopia, that would probably lead to Britain pushing the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide Intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by ...

to impose sanctions on Italy, which the French would almost certainly not veto out of fear of destroying relations with Britain; that would cause a crisis in Anglo-Italian relations and allow Germany to offer its "good services" to Italy. In that way, Hitler hoped to win Mussolini as an ally and to destroy the Stresa Front.

A final possible foreign ally of Ethiopia was Japan, which had served as a model to some Ethiopian intellectuals. After the Welwel incident, several right-wing Japanese groups, including the Great Asianism Association and the Black Dragon Society

The , or the Amur River Society, was a prominent paramilitary, ultranationalist group in Japan.

History

The ''Kokuryūkai'' was founded in 1901 by martial artist Uchida Ryohei as a successor to his mentor Mitsuru Tōyama's '' Gen'yōsha' ...

, attempted to raise money for the Ethiopian cause. The Japanese ambassador to Italy, Dr. Sugimura Yotaro, on 16 July assured Mussolini that Japan held no political interests in Ethiopia and would stay neutral in the coming war. His comments stirred up a furor inside Japan, where there had been popular affinity for the fellow nonwhite empire in Africa, which was reciprocated with similar anger in Italy towards Japan combined with praise for Mussolini and his firm stance against the "gialli di Tokyo" ("Tokyo Yellows"). Despite popular opinion, when the Ethiopians approached Japan for help on 2 August, they were refused, and even a modest request for the Japanese government for an official statement of its support for Ethiopia during the coming conflict was denied.

Armies

Ethiopian forces

With war appearing inevitable, the Ethiopian EmperorHaile Selassie

Haile Selassie I ( gez, ቀዳማዊ ኀይለ ሥላሴ, Qädamawi Häylä Səllasé, ; born Tafari Makonnen; 23 July 189227 August 1975) was Emperor of Ethiopia from 1930 to 1974. He rose to power as Regent Plenipotentiary of Ethiopia (' ...

ordered a general mobilisation of the Army of the Ethiopian Empire:

Selassie's army consisted of around 500,000 men, some of whom were armed with spears and bows. Other soldiers carried more modern weapons including rifles, but many of them were equipment from before 1900 and so were obsolete. According to Italian estimates, on the eve of hostilities, the Ethiopians had an army of 350,000–760,000 men. Only about 25% of the army had any military training, and the men were armed with a motley of 400,000 rifles of every type and in every condition. The Ethiopian Army had about 234 antiquated pieces of artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during sieg ...

mounted on rigid gun carriages as well as a dozen 3.7 cm PaK 35/36 anti-tank guns. The army had about 800 light Colt

Colt(s) or COLT may refer to:

* Colt (horse), an intact (uncastrated) male horse under four years of age

People

*Colt (given name)

*Colt (surname)

Places

* Colt, Arkansas, United States

*Colt, Louisiana, an unincorporated community, United State ...

and Hotchkiss

Hotchkiss may refer to:

Places Canada

* Hotchkiss, Alberta

* Hotchkiss, Calgary

United States

* Hotchkiss, Colorado

* Hotchkiss, Virginia

* Hotchkiss, West Virginia

Business and industry

* Hotchkiss (car), a French automobile manufactu ...

machine-guns and 250 heavy Vickers

Vickers was a British engineering company that existed from 1828 until 1999. It was formed in Sheffield as a steel foundry by Edward Vickers and his father-in-law, and soon became famous for casting church bells. The company went public in ...

and Hotchkiss

Hotchkiss may refer to:

Places Canada

* Hotchkiss, Alberta

* Hotchkiss, Calgary

United States

* Hotchkiss, Colorado

* Hotchkiss, Virginia

* Hotchkiss, West Virginia

Business and industry

* Hotchkiss (car), a French automobile manufactu ...

machine guns, about 100 .303-inch Vickers guns on AA mounts, 48 20 mm Oerlikon S anti-aircraft guns and some recently purchased Canon de 75 CA modèle 1917 Schneider field guns. The arms embargo imposed on the belligerents by France and Britain disproportionately affected Ethiopia, which lacked the manufacturing industry to produce its own weapons. The Ethiopian army had some 300 truck

A truck or lorry is a motor vehicle designed to transport cargo, carry specialized payloads, or perform other utilitarian work. Trucks vary greatly in size, power, and configuration, but the vast majority feature body-on-frame constructi ...

s, seven Ford A-based armoured cars and four World War I era Fiat 3000

The Fiat 3000 was the first tank to be produced in series in Italy. It became the standard tank of the emerging Italian armored units after World War I. The 3000 was based on the French Renault FT.

History

Although 1,400 units were ordered, w ...

tanks.

The best Ethiopian units were the emperor's " Kebur Zabagna" (Imperial Guard), which were well-trained and better equipped than the other Ethiopian troops. The Imperial Guard wore a distinctive greenish-khaki uniform of the Belgian Army

The Land Component ( nl, Landcomponent, french: Composante terre) is the land branch of the Belgian Armed Forces. The King of the Belgians is the commander in chief. The current chief of staff of the Land Component is Major-General Pierre Gérard ...

, which stood out from the white cotton cloak (''shamma''), which was worn by most Ethiopian fighters and proved to be an excellent target. The skills of the '' Rases'', the Ethiopian generals armies, were reported to rate from relatively good to incompetent. After Italian objections to the Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, en, Annexation of Austria), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into the Nazi Germany, German Reich on 13 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a "Ger ...

, the German annexation of Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG),, is a country in Central Europe. It is the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany lies between the Baltic and North Sea to the north and the Alps to the sou ...

sent three aeroplanes, 10,000 Mauser rifles and 10 million rounds of ammunition to the Ethiopians.

The serviceable portion of the Ethiopian Air Force

The Ethiopian Air Force (ETAF) () is the air service branch of the Ethiopian National Defence Force. The ETAF is tasked with protecting the national air space, providing support to ground forces, as well as assisting civil operations during na ...

was commanded by a Frenchman, André Maillet, and included three obsolete Potez 25

Potez 25 (also written as Potez XXV) was a French twin-seat, single-engine biplane designed during the 1920s. A multi-purpose fighter-bomber, it was designed as a line aircraft and used in a variety of roles, including fighter and escort mission ...

biplanes. A few transport aircraft had been acquired between 1934 and 1935 for ambulance work, but the Air Force had 13 aircraft and four pilots at the outbreak of the war. Airspeed

In aviation, airspeed is the speed of an aircraft relative to the air. Among the common conventions for qualifying airspeed are:

* Indicated airspeed ("IAS"), what is read on an airspeed gauge connected to a Pitot-static system;

* Calib ...

in England had a surplus Viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory. The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the French word ''roy'', meaning "k ...

racing plane, and its director, Neville Shute

Nevil Shute Norway (17 January 189912 January 1960) was an English novelist and aeronautical engineer who spent his later years in Australia. He used his full name in his engineering career and Nevil Shute as his pen name, in order to protect ...

, was delighted with a good offer for the "white elephant

A white elephant is a possession that its owner cannot dispose of, and whose cost, particularly that of maintenance, is out of proportion to its usefulness. In modern usage, it is a metaphor used to describe an object, construction project, sch ...

" in August 1935. The agent said that it was to fly cinema films around Europe. When the client wanted bomb racks to carry the (flammable) films, Shute agreed to fit lugs under the wings to which they could attach "anything they liked". He was told that the plane was to be used to bomb the Italian oil storage tanks at Massawa, and when the CID enquired about the alien (ex-German) pilot practices in it Shute got the impression that the Foreign Office did not object. However, fuel, bombs and bomb racks from Finland could not be got to Ethiopia in time, and the paid-for Viceroy stayed at its works. The emperor of Ethiopia had £16,000 to spend on modern aircraft to resist the Italians and planned to spend £5000 on the Viceroy and the rest on three Gloster Gladiator

The Gloster Gladiator is a British biplane fighter. It was used by the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) (as the Sea Gladiator variant) and was exported to a number of other air forces during the late 1930s.

Developed priva ...

fighters.

There were 50 foreign mercenaries who joined the Ethiopian forces, including French pilots like Pierre Corriger, the Trinidadian pilot Hubert Julian

Hubert Fauntleroy Julian (21 September 1897 – 19 February 1983) was a Trinidad-born aviation pioneer. He was nicknamed " The Black Eagle".

Early years

Hubert Fauntleroy Julian was born in Port of Spain, Trinidad, in 1897. His father, Henry, ...

, an official Swedish military mission under Captain Viking Tamm, the White Russian Feodor Konovalov and the Czechoslovak writer Adolf Parlesak. Several Austrian Nazis, a team of Belgian fascists and the Cuban mercenary Alejandro del Valle also fought for Haile Selassie. Many of the individuals were military advisers, pilots, doctors or supporters of the Ethiopian cause; 50 mercenaries fought in the Ethiopian army and another 50 people were active in the Ethiopian Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million Volunteering, volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure re ...

or nonmilitary activities. The Italians later attributed most of the relative success achieved by the Ethiopians to foreigners, or ''ferenghi''. (The Italian propaganda machine magnified the number to thousands to explain away the Ethiopian Christmas Offensive in late 1935.)

Haile Selassie

Haile Selassie I ( gez, ቀዳማዊ ኀይለ ሥላሴ, Qädamawi Häylä Səllasé, ; born Tafari Makonnen; 23 July 189227 August 1975) was Emperor of Ethiopia from 1930 to 1974. He rose to power as Regent Plenipotentiary of Ethiopia (' ...

File:Ras Kassa.png, Ras Kassa Haile Darge

'' Leul Ras'' Kassa Hailu KS, GCVO, GBE, ( Amharic: ካሣ ኀይሉ ዳርጌ; 7 August 1881 – 16 November 1956) was a Shewan Amhara nobleman, the son of Dejazmach Haile Wolde Kiros of Lasta, the ruling heir of Lasta's throne and yo ...

File:Damtou, Desta.jpg, Ras Desta Damtew

File:Ras Immiru.jpg, Imru Haile Selassie

Leul Ras Imru Haile Selassie, CBE ( Amharic: ዕምሩ ኀይለ ሥላሴ; 23 November 1892 – 15 August 1980) was an Ethiopian noble, soldier, and diplomat. He served as acting Prime Minister for three days in 1960 during a coup d'éta ...

Italian forces

There were 400,000 Italian soldiers in Eritrea and 285,000 in Italian Somaliland with 3,300 machine guns, 275 artillery pieces, 200

There were 400,000 Italian soldiers in Eritrea and 285,000 in Italian Somaliland with 3,300 machine guns, 275 artillery pieces, 200 tankette

A tankette is a tracked armoured fighting vehicle that resembles a small tank, roughly the size of a car. It is mainly intended for light infantry support and scouting.

s and 205 aircraft. In April 1935, the reinforcement of the Royal Italian Army

The Royal Italian Army ( it, Regio Esercito, , Royal Army) was the land force of the Kingdom of Italy, established with the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy. During the 19th century Italy started to unify into one country, and in 1861 Manf ...

(''Regio Esercito'') and the ''Regia Aeronautica

The Italian Royal Air Force (''Regia Aeronautica Italiana'') was the name of the air force of the Kingdom of Italy. It was established as a service independent of the Regio Esercito, Royal Italian Army from 1923 until 1946. In 1946, the mon ...

'' (Royal Air Force) in East Africa (''Africa Orientale'') accelerated. Eight regular, mountain and blackshirt militia infantry divisions arrived in Eritrea, and four regular infantry divisions arrived in Italian Somaliland, about 685,000 soldiers and a great number of logistical and support units; the Italians included 200 journalists. The Italians had 6,000 machine guns, 2,000 pieces of artillery, 599 tanks and 390 aircraft. The ''Regia Marina

The ''Regia Marina'' (; ) was the navy of the Kingdom of Italy (''Regno d'Italia'') from 1861 to 1946. In 1946, with the birth of the Italian Republic (''Repubblica Italiana''), the ''Regia Marina'' changed its name to ''Marina Militare'' (" ...

'' (Royal Navy) carried tons of ammunition, food and other supplies, with the motor vehicles to move them, but the Ethiopians had only horse-drawn carts.

The Italians placed considerable reliance on their Corps of Colonial Troops (''Regio Corpo Truppe Coloniali'', RCTC) of indigenous regiments recruited from the Italian colonies of Eritrea, Somalia and Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Su ...

. The most effective of the Italian commanded units were the Eritrean native infantry ('' Ascari''), which was often used as advanced troops. The Eritreans also provided cavalry and artillery units; the "Falcon Feathers" (''Penne di Falco'') was one prestigious and colourful Eritrean cavalry unit. Other RCTC units during the invasion of Ethiopia were irregular Somali frontier troops (''dubats''), regular Arab-Somali infantry and artillery and infantry from Libya. The Italians had a variety of local semi-independent "allies" in the north, and the Azebu Galla were among several groups induced to fight for the Italians. In the south, the Somali Sultan Olol Dinle commanded a personal army, which advanced into the northern Ogaden with the forces of Colonel Luigi Frusci

Luigi Frusci (16 January 1879 – 1949) was an officer in the Italian Royal Army (''Regio Esercito'') during the Italian conquest of Ethiopia and World War II. He was the last Italian Governor of Eritrea and Amhara.

Biography

Ordine militare d ...

. The Sultan was motivated by his desire to take back lands that the Ethiopians had taken from him. The Italian colonial forces even included men from Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the north and Oman to the northeast an ...

, across the Gulf of Aden

The Gulf of Aden ( ar, خليج عدن, so, Gacanka Cadmeed 𐒅𐒖𐒐𐒕𐒌 𐒋𐒖𐒆𐒗𐒒) is a deepwater gulf of the Indian Ocean between Yemen to the north, the Arabian Sea to the east, Djibouti to the west, and the Guardafui Chan ...

.

The Italians were reinforced by volunteers from the so-called ''Italiani all'estero'', members of the Italian diaspora

, image = Map of the Italian Diaspora in the World.svg

, image_caption = Map of the Italian diaspora in the world

, population = worldwide

, popplace = Brazil, Argentina, United States, France, Colombia, Canada, ...

from Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, t ...

, Uruguay

Uruguay (; ), officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay ( es, República Oriental del Uruguay), is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast; while bordering ...

and Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

; they formed the 221st Legion in the ''Divisione Tevere'', which a special ''Legione Parini'' fought under Frusci near Dire Dawa. On 28 March 1935, General Emilio De Bono was named the commander-in-chief of all Italian armed forces in East Africa. De Bono was also the commander-in-chief of the forces invading from Eritrea on the northern front. De Bono commanded nine divisions in the Italian I Corps, the Italian II Corps and the Eritrean Corps. General Rodolfo Graziani

Rodolfo Graziani, 1st Marquis of Neghelli (; 11 August 1882 – 11 January 1955), was a prominent Italian military officer in the Kingdom of Italy's ''Regio Esercito'' ("Royal Army"), primarily noted for his campaigns in Africa before and during ...

was commander-in-chief of forces invading from Italian Somaliland on the southern front. Initially, he had two divisions and a variety of smaller units under his command: a mixture of Italians, Somalis, Eritreans, Libyans and others. De Bono regarded Italian Somaliland as a secondary theatre, whose primary need was to defend itself, but it could aid the main front with offensive thrusts if the enemy forces were not too large there. Most foreigners accompanied the Ethiopians, but Herbert Matthews

Herbert Lionel Matthews (January 10, 1900 – July 30, 1977) was a reporter and editorialist for '' The New York Times'' who, at the age of 57, won widespread attention after revealing that the 30-year-old Fidel Castro was still alive and living i ...

, a reporter and historian who wrote ''Eyewitness in Abyssinia: With Marshal Bodoglio's forces to Addis Ababa'' (1937), and Pedro del Valle, an observer for US Marine Corps

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines, is the maritime land force service branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for conducting expeditionary and amphibious operations through co ...

, accompanied the Italian forces.

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

File:E. De Bono 04.jpg, Emilio De Bono

File:Pietro Badoglio 3.jpg, Pietro Badoglio

Pietro Badoglio, 1st Duke of Addis Abeba, 1st Marquess of Sabotino (, ; 28 September 1871 – 1 November 1956), was an Italian general during both World Wars and the first viceroy of Italian East Africa. With the fall of the Fascist regime ...

Hostilities

Italian invasion

At 5:00 am on 3 October 1935, De Bono crossed the Mareb River and advanced into Ethiopia from Eritrea without a declaration of war. Aircraft of the ''Regia Aeronautica'' scattered leaflets asking the population to rebel against Haile Selassie and support the "true Emperor

At 5:00 am on 3 October 1935, De Bono crossed the Mareb River and advanced into Ethiopia from Eritrea without a declaration of war. Aircraft of the ''Regia Aeronautica'' scattered leaflets asking the population to rebel against Haile Selassie and support the "true Emperor Iyasu V

''Lij'' Iyasu ( gez, ልጅ ኢያሱ; 4 February 1895 – 25 November 1935) was the designated Emperor of Ethiopia from 1913 to 1916. His baptismal name was Kifle Yaqob (ክፍለ ያዕቆብ ''kəflä y’aqob''). Ethiopian emperors tradition ...

". Forty-year-old Iyasu had been deposed many years earlier but was still in custody. In response to the Italian invasion, Ethiopia declared war on Italy. At this point in the campaign, the lack of roads represented a serious hindrance for the Italians as they crossed into Ethiopia. On the Eritrean side, roads had been constructed right up to the border. On the Ethiopian side, these roads often transitioned into vaguely defined paths, and the Italian army used aerial photography

Aerial photography (or airborne imagery) is the taking of photographs from an aircraft or other airborne platforms. When taking motion pictures, it is also known as aerial videography.

Platforms for aerial photography include fixed-wing aircr ...

to plan its advance, as well as mustard gas attacks. On 5 October the Italian I Corps took Adigrat

Adigrat (, ''ʿaddigrat'', also called ʿAddi Grat) is a city and separate woreda in Tigray Region of Ethiopia. It is located in the Misraqawi Zone at longitude and latitude , with an elevation of above sea level and below a high ridge to the we ...

, and by 6 October, Adwa

Adwa ( ti, ዓድዋ; amh, ዐድዋ; also spelled Aduwa) is a town and separate woreda in Tigray Region, Ethiopia. It is best known as the community closest to the site of the 1896 Battle of Adwa, in which Ethiopian soldiers defeated Ital ...

(Adowa) was captured by the Italian II Corps. Haile Selassie had ordered Duke

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of Royal family, royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, t ...

(''Ras'') Seyoum Mangasha, the Commander of the Ethiopian Army of Tigre, to withdraw a day's march away from the Mareb River. Later, the Emperor ordered his son-in-law and Commander of the Gate (''Dejazmach

Until the end of the Ethiopian monarchy in 1974, there were two categories of nobility in Ethiopia and Eritrea. The Mesafint ( gez, መሳፍንት , modern , singular መስፍን , modern , "prince"), the hereditary nobility, formed the upper ...

'') Haile Selassie Gugsa, also in the area, to move back from the border.

On 11 October, Gugsa surrendered with 1,200 followers at the Italian outpost at Adagamos; Italian propagandists lavishly publicised the surrender but fewer than a tenth of Gugsa's men defected with him. On 14 October, De Bono proclaimed the end of slavery in Ethiopia but this liberated the former slave owners from the obligation to feed their former slaves, in the unsettled conditions caused by the war. Much of the livestock in the area had been moved to the south to feed the Ethiopian army and many of the emancipated people had no choice but to appeal to the Italian authorities for food. By 15 October, De Bono's forces had advanced from Adwa and occupied the holy capital of Axum

Axum, or Aksum (pronounced: ), is a town in the Tigray Region of Ethiopia with a population of 66,900 residents (as of 2015).

It is the site of the historic capital of the Aksumite Empire, a naval and trading power that ruled the whole region ...

. De Bono entered the city riding on a white horse and then looted the Obelisk of Axum. To Mussolini's dismay, the advance was methodical and on 8 November, the I Corps and the Eritrean Corps captured Makale. The Italian advance had added to the line of supply and De Bono wanted to build a road from Adigrat before continuing. On 16 November, De Bono was promoted to the rank of Marshal of Italy

Marshal of Italy ( it, Maresciallo d'Italia) was a rank in the Royal Italian Army (''Regio Esercito''). Originally created in 1924 by Italian dictator Benito Mussolini for the purpose of honoring Generals Luigi Cadorna and Armando Diaz, the ...

(''Maresciallo d'Italia'') and in December was replaced by Badoglio to speed up the invasion.

Hoare–Laval Pact

On 14 November 1935, the National government in Britain, led by Prime MinisterStanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, (3 August 186714 December 1947) was a British Conservative Party politician who dominated the government of the United Kingdom between the world wars, serving as Prime Minister of the United Kingd ...

, won a general election on a platform of upholding collective security and support for the League of Nations, which at least implied that Britain would support Ethiopia. However, the British service chiefs, led by the First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Earle Chatfield, all advised against going to war with Italy for the sake of Ethiopia, which carried much weight with the cabinet. During the 1935 election, Baldwin and the rest of the cabinet had repeatedly promised that Britain was committed to upholding collective security in the belief of that being the best way to neutralise the Labour Party, which also ran on a platform emphasising collective security and support for the League of Nations. To square the circle caused by its election promises and its desire to avoid offending Mussolini too much, the cabinet decided upon a plan to give most of Ethiopia to Italy, with the rest in the Italian sphere of influence

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence (SOI) is a spatial region or concept division over which a state or organization has a level of cultural, economic, military or political exclusivity.

While there may be a formal al ...

, as the best way of ending the war.

In early December 1935, the Hoare–Laval Pact

The Hoare–Laval Pact was an initially secret December 1935 proposal by British Foreign Secretary Samuel Hoare and French Prime Minister Pierre Laval for ending the Second Italo-Ethiopian War. Italy had wanted to seize the independent nation of ...

was proposed by Britain and France. Italy would gain the best parts of Ogaden and Tigray and economic influence over all the south. Abyssinia would have a guaranteed corridor to the sea at the port of Assab

Assab or Aseb (, ) is a port city in the Southern Red Sea Region of Eritrea. It is situated on the west coast of the Red Sea.

Languages spoken in Assab are predominantly Afar, Tigrinya, and Arabic. Assab is known for its large market, beaches ...

; the corridor was a poor one and known as a "corridor for camels". Mussolini was ready to play along with considering the Hoare-Laval Pact, rather than rejecting it outright, to avoid a complete break with Britain and France, but he kept demanding changes to the plan before he would accept it as a way to stall for more time to allow his army to conquer Ethiopia. Mussolini was not prepared to abandon the goal of conquering Ethiopia, but the imposition of League of Nations sanctions on Italy caused much alarm in Rome. The war was wildly popular with the Italian people, who relished Mussolini's defiance of the League as an example of Italian greatness. Even if Mussolini had been willing to stop the war, the move would have been very unpopular in Italy. Kallis wrote, "Especially after the imposition of sanctions in November 1935, the popularity of the Fascist regime reached unprecedented heights". On 13 December, details of the pact were leaked by a French newspaper and denounced as a sellout of the Ethiopians. The British government disassociated itself from the pact and British Foreign Secretary Sir Samuel Hoare was forced to resign in disgrace.

Ethiopian Christmas Offensive

The Christmas Offensive was intended to split the Italian forces in the north with the Ethiopian centre, crushing the Italian left with the Ethiopian right and to invade Eritrea with the Ethiopian left. ''Ras'' Seyum Mangasha held the area around

The Christmas Offensive was intended to split the Italian forces in the north with the Ethiopian centre, crushing the Italian left with the Ethiopian right and to invade Eritrea with the Ethiopian left. ''Ras'' Seyum Mangasha held the area around Abiy Addi

Abiy Addi (also spelled Abi Addi; Tigrigna ዓብዪ ዓዲ "Big town") is a town in central Tigray Region, Tigray, Ethiopia. Abiy Addi is at the southeastern edge of the Kola Tembien woreda, of which it is the capital.

Overview

The town is di ...

with about 30,000 men. Selassie with about 40,000 men advanced from Gojjam

Gojjam ( ''gōjjām'', originally ጐዛም ''gʷazzam'', later ጐዣም ''gʷažžām'', ጎዣም ''gōžžām'') is a historical province in northwestern Ethiopia, with its capital city at Debre Marqos.

Gojjam's earliest western boundary e ...

toward Mai Timket to the left of ''Ras'' Seyoum. ''Ras'' Kassa Haile Darge with around 40,000 men advanced from Dessie

Dessiè City which is politically oppressed by the past Ethiopian government systems due to the fact that most of the population follow Islamic religion.

Dessie ( am, ደሴ, Däse; also spelled Dese or Dessye) is a town in north-central Ethiopia ...

to support ''Ras'' Seyoum in the centre in a push towards Warieu Pass. ''Ras'' Mulugeta Yeggazu, the Minister of War, advanced from Dessie with approximately 80,000 men to take positions on and around Amba Aradam

Amba Aradam is a table mountain in northern Ethiopia. Located in the Debub Misraqawi (Southeastern) Zone of the Tigray Region, between Mek'ele and Addis Abeba, it has a latitude and longitude of and an elevation of .

The name in Tigrinya is ...

to the right of ''Ras'' Seyoum. Amba Aradam was a steep sided, flat topped mountain directly in the way of an Italian advance on Addis Ababa. The four commanders had approximately 190,000 men facing the Italians. ''Ras'' Imru and his Army of Shire were on the Ethiopian left. ''Ras'' Seyoum and his Army of Tigre and ''Ras'' Kassa and his Army of Beghemder

Begemder ( amh, በጌምድር; also known as Gondar or Gonder, alternative name borrowed from its 20th century capital Gondar) was a province in northwest Ethiopia.

Etymology

A plausible source for the name ''Bega'' is that the word means " ...

were the Ethiopian centre. ''Ras'' Mulugeta and his "Army of the Center" (''Mahel Sefari'') were on the Ethiopian right.

A force of 1,000 Ethiopians crossed the Tekeze river and advanced toward the Dembeguina Pass (Inda Aba Guna or Indabaguna pass). The Italian commander, Major Criniti, commanded a force of 1,000 Eritrean infantry supported by L3 tanks. When the Ethiopians attacked, the Italian force fell back to the pass, only to discover that 2,000 Ethiopian soldiers were already there and Criniti's force was encircled. In the first Ethiopian attack, two Italian officers were killed and Criniti was wounded. The Italians tried to break out using their L3 tanks but the rough terrain immobilised the vehicles. The Ethiopians killed the infantry, then rushed the tanks and killed their two-man crews. Italian forces organised a relief column made up of tanks and infantry to relieve Critini but it was ambushed en route. Ethiopians on the high ground rolled boulders in front of and behind several of the tanks, to immobilise them, picked off the Eritrean infantry and swarmed the tanks. The other tanks were immobilised by the terrain, unable to advance further and two were set on fire. Critini managed to break-out in a bayonet charge and half escaped; Italian casualties were 31 Italians and 370 Askari killed and five Italians taken prisoner; Ethiopian casualties were estimated by the Italians to be 500, which was probably greatly exaggerated.

The news from the "northern front" was generally bad for Italy. However, foreign correspondents in Addis Ababa publicly took up knitting to mock their lack of access to the front. There was no way for them to verify reports that 4,700 Italians had been captured. The correspondents were told by the Ethiopians that Italian tanks had been stranded and abandoned and that Italian native troops were mutinying. Later, a report was issued that Ethiopian warriors had captured eighteen tanks, thirty-three field guns, 175 machine guns, and 2,605 rifles. In addition, this report indicated that the Ethiopians had wiped out an entire legion of the 2nd CC.NN. Division "28 Ottobre" and that the Italians had lost at least 3,000 men. Rome denied these figures.

The ambitious Ethiopian plan called for ''Ras'' Kassa and ''Ras'' Seyoum to split the Italian army in two and isolate the Italian I Corps and III Corps in Mekele. ''Ras'' Mulugeta would then descend from Amba Aradam and crush both corps. According to this plan, after ''Ras'' Imru retook Adwa, he was to invade Eritrea. In November, the League of Nations condemned Italy's aggression and imposed economic sanctions. This excluded oil, however, an indispensable raw material for the conduct of any modern military campaign, and this favoured Italy.

The Ethiopian counteroffensive managed to stop the Italian advance for a few weeks, but the superiority of the Italian's weaponry (artillery and machine guns) as well as aerial bombardment with chemical weapon

A chemical weapon (CW) is a specialized munition that uses chemicals formulated to inflict death or harm on humans. According to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), this can be any chemical compound intended as ...

s, at first with mustard gas

Mustard gas or sulfur mustard is a chemical compound belonging to a family of cytotoxic and blister agents known as mustard agents. The name ''mustard gas'' is technically incorrect: the substance, when dispersed, is often not actually a gas, b ...

prevented the Ethiopians from taking advantage of their initial successes. The Ethiopians in general were very poorly armed, with few machine guns, their troops mainly armed with swords and spears. Having spent a decade accumulating poison gas in East Africa, Mussolini gave Badoglio authority to resort to '' Schrecklichkeit'' (frightfulness), which included destroying villages and using gas (OC 23/06, 28 December 1935); Mussolini was even prepared to resort to bacteriological warfare as long as these methods could be kept quiet. Some Italians objected when they found out but the practices were kept secret, the government issuing denials or spurious stories blaming the Ethiopians.

Second Italian advance

As the progress of the Christmas Offensive slowed, Italian plans to renew the advance on the northern front began as Mussolini had given permission to usepoison gas

Many gases have toxic properties, which are often assessed using the LC50 (median lethal dose) measure. In the United States, many of these gases have been assigned an NFPA 704 health rating of 4 (may be fatal) or 3 (may cause serious or perm ...

(but not mustard gas

Mustard gas or sulfur mustard is a chemical compound belonging to a family of cytotoxic and blister agents known as mustard agents. The name ''mustard gas'' is technically incorrect: the substance, when dispersed, is often not actually a gas, b ...

) and Badoglio received the Italian III Corps and the Italian IV Corps in Eritrea during early 1936. On 20 January, the Italians resumed their northern offensive at the First Battle of Tembien (20 to 24 January) in the broken terrain between the Warieu Pass and Makale. The forces of Ras Kassa were defeated, the Italians using phosgene gas and suffering 1,082 casualties against 8,000 Ethiopian casualties according to an Ethiopian wireless message intercepted by the Italians.

From 10 to 19 February, the Italians captured Amba Aradam and destroyed ''Ras'' Mulugeta's army in the Battle of Amba Aradam (Battle of Enderta). The Ethiopians suffered massive losses and poison gas destroyed a small part of ''Ras'' Mulugeta's army, according to the Ethiopians. During the slaughter following the attempted withdrawal of his army, both ''Ras'' Mulugeta and his son were killed. The Italians lost 800 killed and wounded while the Ethiopians lost 6,000 killed and 12,000 wounded. From 27 to 29 February, the armies of ''Ras'' Kassa and ''Ras'' Seyoum were destroyed at the Second Battle of Tembien. Ethiopians again argued that poison gas played a role in the destruction of the withdrawing armies. In early March, the army of ''Ras'' Imru was attacked, bombed and defeated in what was known as the Battle of Shire. In the battles of Amba Aradam, Tembien and Shire, the Italians suffered about 2,600 casualties and the Ethiopians about 15,000; Italian casualties at the Battle of Shire being 969 men. The Italian victories stripped the Ethiopian defences on the northern front, Tigré province had fallen most of the Ethiopian survivors returned home or took refuge in the countryside and only the army guarding Addis Ababa stood between the Italians and the rest of the country.

On 31 March 1936 at the

On 31 March 1936 at the Battle of Maychew

The Battle of Maychew ( it, Mai Ceu) was the last major battle fought on the northern front during the Second Italo-Abyssinian War. The battle consisted of a failed counterattack by the Ethiopian forces under Emperor Haile Selassie making fro ...

, the Italians defeated an Ethiopian counter-offensive

In the study of military tactics, a counter-offensive is a large-scale strategic offensive military operation, usually by forces that had successfully halted the enemy's offensive, while occupying defensive positions.

The counter-offensive is ...

by the main Ethiopian army commanded by Selassie. The Ethiopians launched near non-stop attacks on the Italian and Eritrean defenders but could not overcome the well-prepared Italian defences. When the exhausted Ethiopians withdrew, the Italians counter-attacked. The ''Regia Aeronautica'' attacked the survivors at Lake Ashangi with mustard gas. The Italian troops had 400 casualties, the Eritreans 874 and the Ethiopians suffered 8,900 casualties from 31,000 men present according to an Italian estimate. On 4 April, Selassie looked with despair upon the horrific sight of the dead bodies of his army ringing the poisoned lake. Following the battle, Ethiopian soldiers began to employ guerrilla tactics against the Italians, initiating a trend of resistance that would transform into the Patriot/''Arbegnoch'' movement. They were joined by local residents who operated independently near their own homes. Early activities included capturing war materials, rolling boulders off cliffs at passing convoys, kidnapping messengers, cutting telephone lines, setting fire to administrative offices and fuel and ammunition dump

An ammunition dump, ammunition supply point (ASP), ammunition handling area (AHA) or ammunition depot is a military storage facility for live ammunition and explosives.

The storage of live ammunition and explosives is inherently hazardous. Th ...

s, and killing collaborators. As disruption increased, the Italians were forced to redeploy more troops to Tigre, away from the campaign further south.

Southern front

On 3 October 1935, Graziani implemented the Milan Plan to remove Ethiopian forces from various frontier posts and to test the reaction to a series of probes all along the southern front. While incessant rains worked to hinder the plan, within three weeks the Somali villages of

On 3 October 1935, Graziani implemented the Milan Plan to remove Ethiopian forces from various frontier posts and to test the reaction to a series of probes all along the southern front. While incessant rains worked to hinder the plan, within three weeks the Somali villages of Kelafo

Kelafo ( so, Qalaafe, am, ቀላፎ, translit=Qällafo) is a town in eastern Ethiopia. Located in the Gode Zone of the Somali Region, this town has a latitude and longitude of and an elevation of 233 meters above sea level.

The UN-OCHA-Eth ...

, Dagnerai, Gerlogubi and Gorahai in Ogaden were in Italian hands. Late in the year, ''Ras'' Desta Damtu assembled up his army in the area around Negele Borana, to advance on Dolo

Dolo is a town and ''comune'' in the Metropolitan City of Venice, Veneto, Italy. It is connected by the SP26 provincial road and is one of the towns of the Riviera del Brenta.

The growth of the town of Dolo is due to the gradual downsizing of t ...

and invade Italian Somaliland. Between 12 and 16 January 1936, the Italians defeated the Ethiopians at the Battle of Genale Doria. The ''Regia Aeronautica'' destroyed the army of ''Ras'' Desta, Ethiopians claiming that poison gas was used.

After a lull in February 1936, the Italians in the south prepared an advance towards the city of Harar

Harar ( amh, ሐረር; Harari: ሀረር; om, Adare Biyyo; so, Herer; ar, هرر) known historically by the indigenous as Gey (Harari: ጌይ ''Gēy'', ) is a walled city in eastern Ethiopia. It is also known in Arabic as the City of Sain ...

. On 22 March, the ''Regia Aeronautica'' bombed Harar and Jijiga

Jijiga (, am, ጅጅጋ, ''Jijiga'') is the capital city of Somali Region, Ethiopia. It became the capital of the Somali Region in 1995 after it was moved from Gode. Located in the Fafan Zone with 70 km (37 mi) west of the bor ...

, reducing them to ruins even though Harar had been declared an "open city

In war, an open city is a settlement which has announced it has abandoned all defensive efforts, generally in the event of the imminent capture of the city to avoid destruction. Once a city has declared itself open the opposing military will be ...

". On 14 April, Graziani launched his attack against ''Ras'' Nasibu Emmanual

Nasibu Zeamanuel, also Nasibu Zamanuael or ''Nasibu Emmanual'' in some texts ( Amharic: ነሲቡ ዘአማኑኤል; 1893 – 16 October 1936), was an army commander of the Ethiopian Empire. Along with his brother Wasane, historian Bahru Zew ...

to defeat the last Ethiopian army in the field at the Battle of the Ogaden. The Ethiopians were drawn up behind a defensive line that was termed the "Hindenburg Wall", designed by the chief of staff of Ras Nasibu, and Wehib Pasha

Wehib Pasha also known as Vehip Pasha, Mehmed Wehib Pasha, Mehmet Vehip Pasha (modern Turkish: ''Kaçı Vehip Paşa'' or ''Mehmet Vehip (Kaçı)'', 1877–1940), was a general in the Ottoman Army. He fought in the Balkan Wars and in several the ...