The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by

other names) was a

civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

in the

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

between the

Union ("the North") and the

Confederacy ("the South"), which was formed in 1861 by

states

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

that had

seceded

Secession is the formal withdrawal of a group from a political entity. The process begins once a group proclaims an act of secession (such as a declaration of independence). A secession attempt might be violent or peaceful, but the goal is the c ...

from the Union. The

central conflict leading to war was a dispute over whether

slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

should be permitted to expand into the western territories, leading to more

slave states

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were prohibited. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave s ...

, or be prohibited from doing so, which many believed would place slavery on a course of ultimate extinction.

over slavery came to a head when

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

, who opposed slavery's expansion, won the

1860 presidential election

United States presidential election, Presidential elections were held in the United States on November 6, 1860. The History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party ticket of Abraham Lincoln and Hannibal Hamlin emerged victoriou ...

. Seven Southern slave states responded to Lincoln's victory by seceding from the United States and forming the Confederacy. The Confederacy seized U.S. forts and other federal assets within their borders. The war began on April 12, 1861, when the Confederacy bombarded

Fort Sumter

Fort Sumter is a historical Coastal defense and fortification#Sea forts, sea fort located near Charleston, South Carolina. Constructed on an artificial island at the entrance of Charleston Harbor in 1829, the fort was built in response to the W ...

in

South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

. A wave of enthusiasm for war swept over the North and South, as military recruitment soared. Four more Southern states seceded after the war began and, led by its president,

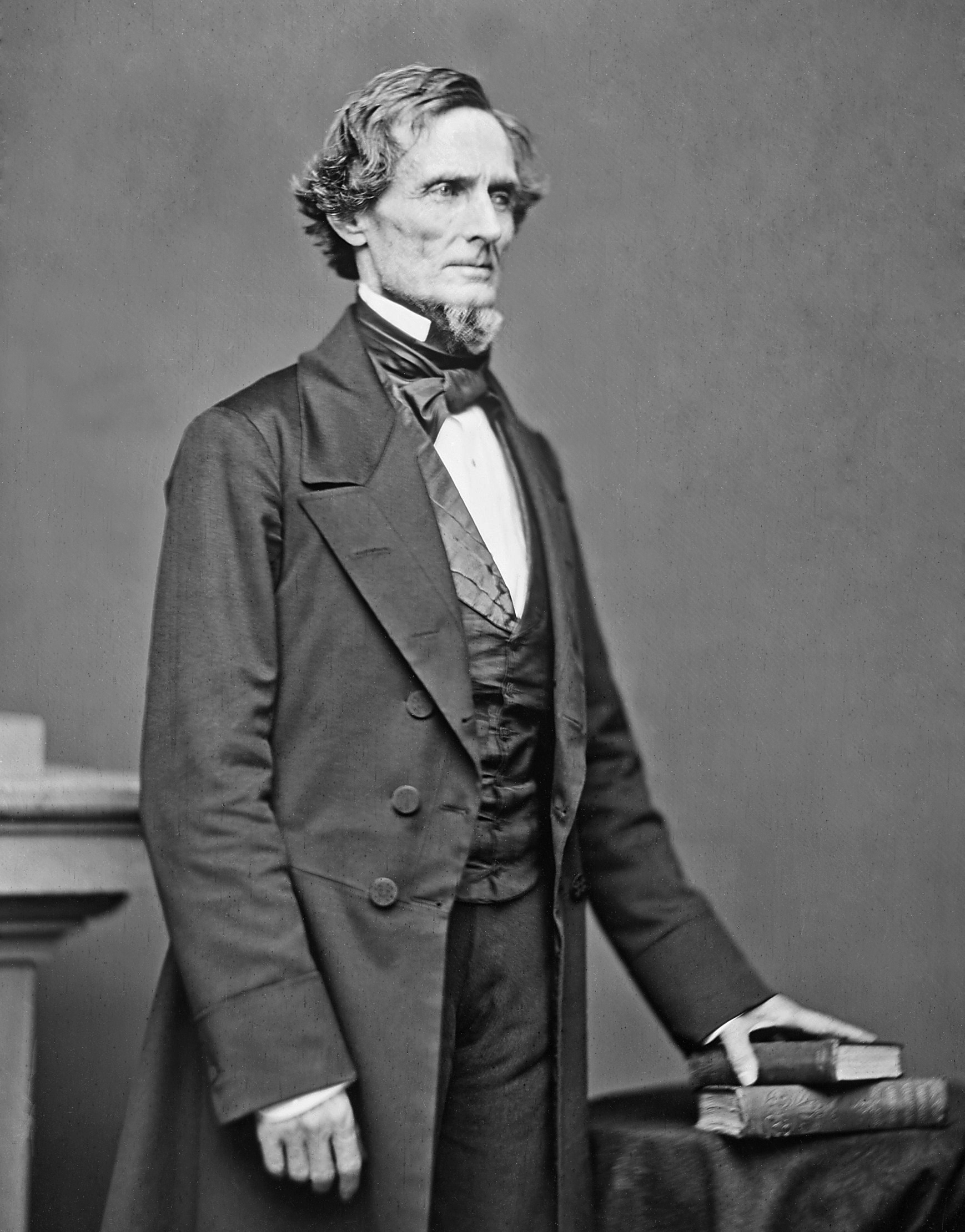

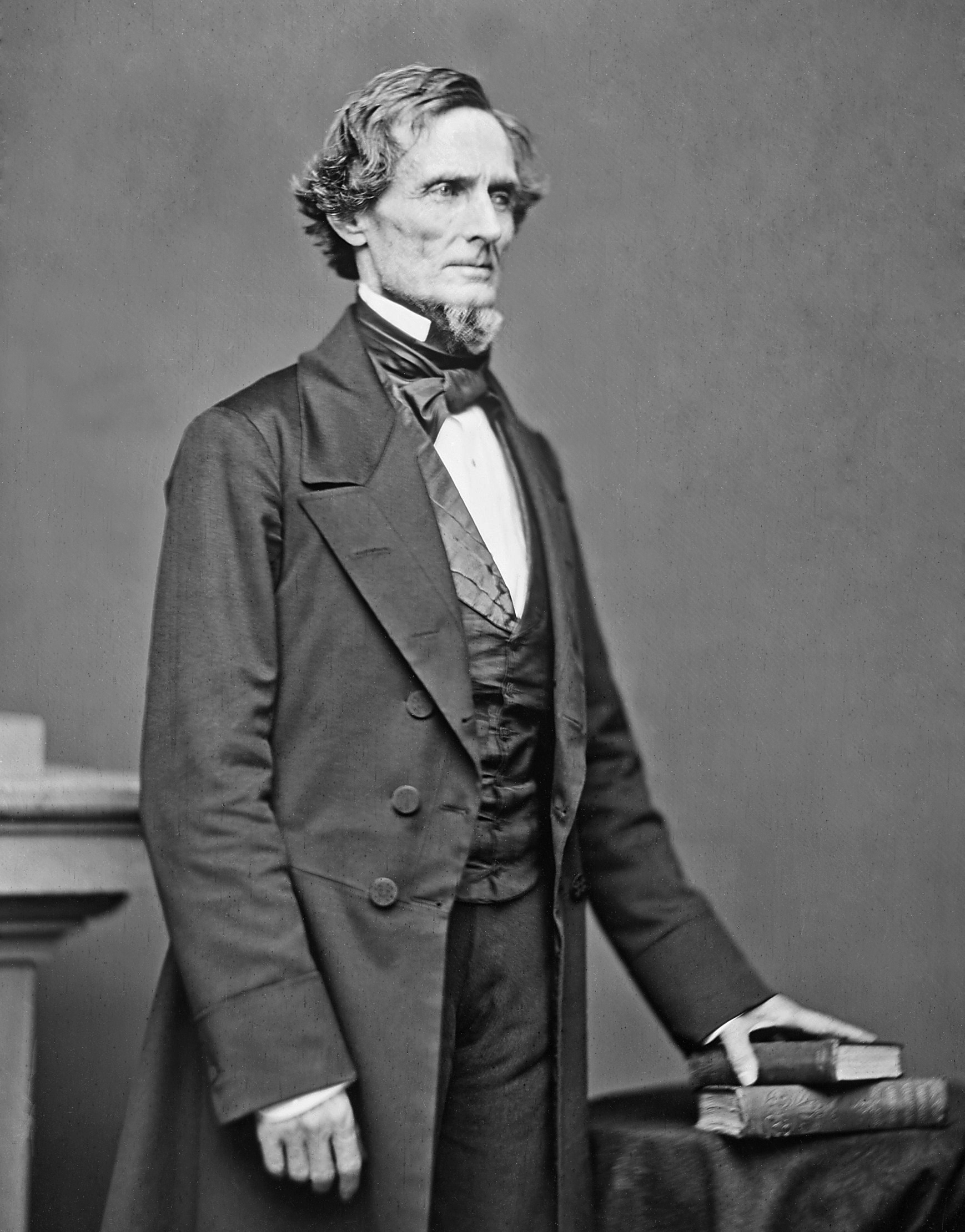

Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the only President of the Confederate States of America, president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the Unite ...

, the Confederacy asserted control over a third of the U.S. population in eleven states. Four years of intense combat, mostly in the South, ensued.

During 1861–1862 in the

Western theater, the Union made permanent gains—though in the

Eastern theater the conflict was inconclusive. The abolition of slavery became a Union war goal on January 1, 1863, when Lincoln issued the

Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War. The Proclamation had the eff ...

, which declared all slaves in rebel states to be free, applying to more than 3.5 million of the 4 million enslaved people in the country. To the west, the Union first destroyed the Confederacy's river navy by the summer of 1862, then much of its western armies, and

seized New Orleans. The successful 1863 Union

siege of Vicksburg

The siege of Vicksburg (May 18 – July 4, 1863) was the final major military action in the Vicksburg campaign of the American Civil War. In a series of maneuvers, Union Major General Ulysses S. Grant and his Army of the Tennessee crossed th ...

split the Confederacy in two at the

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

, while Confederate general

Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a general officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate general during the American Civil War, who was appointed the General in Chief of the Armies of the Confederate ...

's incursion north failed at the

Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was a three-day battle in the American Civil War, which was fought between the Union and Confederate armies between July 1 and July 3, 1863, in and around Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The battle, won by the Union, ...

. Western successes led to General

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

's command of all Union armies in 1864. Inflicting an ever-tightening

naval blockade

A navy, naval force, military maritime fleet, war navy, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations ...

of Confederate ports, the Union marshaled resources and manpower to attack the Confederacy from all directions. This led to the

fall of Atlanta

Autumn, also known as fall (especially in US & Canada), is one of the four temperate seasons on Earth. Outside the tropics, autumn marks the transition from summer to winter, in September (Northern Hemisphere) or March ( Southern Hemispher ...

in 1864 to Union general

William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman ( ; February 8, 1820February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a General officer, general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), earning recognit ...

, followed by his

March to the Sea, which culminated in his taking

Savannah

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) biome and ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to reach th ...

. The last significant battles raged around the ten-month

Siege of Petersburg

The Richmond–Petersburg campaign was a series of battles around Petersburg, Virginia, fought from June 9, 1864, to March 25, 1865, during the American Civil War. Although it is more popularly known as the siege of Petersburg, it was not a c ...

, gateway to the Confederate capital of

Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, a city in the United States

* Richmond, London, a town in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, England

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town ...

. The Confederates abandoned Richmond, and on April 9, 1865, Lee surrendered to Grant following the

Battle of Appomattox Court House

The Battle of Appomattox Court House, fought in Appomattox County, Virginia, on the morning of April 9, 1865, was one of the last, and ultimately one of the most consequential, battles of the American Civil War (1861–1865). It was the final e ...

, setting in motion the

end of the war. Lincoln lived to see this victory but

was shot by an assassin on April 14, dying the next day.

By the end of the war, much of the South's infrastructure was destroyed. The Confederacy collapsed, slavery was abolished, and four million enslaved black people were freed. The war-torn nation then entered the

Reconstruction era

The Reconstruction era was a period in History of the United States, US history that followed the American Civil War (1861-65) and was dominated by the legal, social, and political challenges of the Abolitionism in the United States, abol ...

in an attempt to rebuild the country, bring the former Confederate states back into the United States, and grant

civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' political freedom, freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and ...

to freed slaves. The war is one of the most extensively studied and

written about episodes in the

history of the United States

The history of the present-day United States began in roughly 15,000 BC with the arrival of Peopling of the Americas, the first people in the Americas. In the late 15th century, European colonization of the Americas, European colonization beg ...

. It remains the subject of cultural and

historiographical debate. Of continuing interest is the myth of the

Lost Cause of the Confederacy

The Lost Cause of the Confederacy, known simply as the Lost Cause, is an American pseudohistory, pseudohistorical and historical negationist myth that argues the cause of the Confederate States of America, Confederate States during the America ...

. The war was among the first to use

industrial warfare

Industrial warfare is a period in the history of warfare ranging roughly from the early 19th century and the start of the Industrial Revolution to the beginning of the Atomic Age, which saw the rise of nation-states, capable of creating and e ...

. Railroads, the

electrical telegraph

Electrical telegraphy is point-to-point distance communicating via sending electric signals over wire, a system primarily used from the 1840s until the late 20th century. It was the first electrical telecommunications system and the most wid ...

, steamships, the

ironclad warship

An ironclad was a steam-propelled warship protected by steel or iron armor constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships to explosive or incendiary shells. The firs ...

, and mass-produced weapons were widely used. The war left an estimated 698,000 soldiers dead, along with an undetermined number of civilian casualties, making the Civil War the deadliest military conflict in American history. The technology and brutality of the Civil War foreshadowed the coming

world war

A world war is an international War, conflict that involves most or all of the world's major powers. Conventionally, the term is reserved for two major international conflicts that occurred during the first half of the 20th century, World War I ...

s.

Origins

The origins of the war were rooted in the desire of the

Southern states to preserve the

institution of slavery. Historians in the 21st century overwhelmingly agree on the centrality of slavery in the conflict—at least for the Southern states. They disagree on which aspects (ideological, economic, political, or social) were most important, and on the

North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating Direction (geometry), direction or geography.

Etymology

T ...

's reasons for refusing to allow the Southern states to secede. The pseudo-historical

Lost Cause

The Lost Cause of the Confederacy, known simply as the Lost Cause, is an American pseudohistorical and historical negationist myth that argues the cause of the Confederate States during the American Civil War was just, heroic, and not cente ...

ideology denies that slavery was the principal cause of the secession, a view disproven by historical evidence, notably some of the seceding states' own

secession documents. After leaving the Union, Mississippi issued a declaration stating, "Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery—the greatest material interest of the world."

The principal political battle leading to Southern secession was over whether slavery would expand into the Western territories destined to become states. Initially

Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

had admitted new states into the Union in pairs,

one slave and one free. This had kept a sectional balance in the

Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

but not in the

House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entities. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often ...

, as free states outstripped slave states in numbers of eligible voters.

Thus, at mid-19th century, the free-versus-slave status of the new territories was a critical issue, both for the North, where anti-slavery sentiment had grown, and for the South, where the fear of slavery's

abolition

Abolition refers to the act of putting an end to something by law, and may refer to:

*Abolitionism, abolition of slavery

*Capital punishment#Abolition of capital punishment, Abolition of the death penalty, also called capital punishment

*Abolitio ...

had grown. Another factor leading to secession and the formation of the

Confederacy was the development of

white Southern nationalism in the preceding decades. The primary reason for the North to reject secession was to preserve the Union, a cause based on

American nationalism

American nationalism is a form of civic, ethnic, cultural or economic influences

*

*

*

*

*

*

* found in the United States. Essentially, it indicates the aspects that characterize and distinguish the United States as an autonomous political com ...

.

Background factors in the run up to the Civil War were

partisan politics

A partisan is a committed member or supporter of a political party or political movement. In multi-party systems, the term is used for persons who strongly support their party's policies and are reluctant to compromise with political opponents ...

,

abolitionism

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was France in 1315, but it was later used in its colonies. ...

,

nullification

Nullification may refer to:

* Nullification (U.S. Constitution), a legal theory that a state has the right to nullify any federal law deemed unconstitutional with respect to the United States Constitution

** Nullification crisis, the 1832 confron ...

versus

secession

Secession is the formal withdrawal of a group from a Polity, political entity. The process begins once a group proclaims an act of secession (such as a declaration of independence). A secession attempt might be violent or peaceful, but the goal i ...

, Southern and Northern nationalism,

expansionism

Expansionism refers to states obtaining greater territory through military Imperialism, empire-building or colonialism.

In the classical age of conquest moral justification for territorial expansion at the direct expense of another established p ...

,

economics

Economics () is a behavioral science that studies the Production (economics), production, distribution (economics), distribution, and Consumption (economics), consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interac ...

, and modernization in the

antebellum period

The ''Antebellum'' South era (from ) was a period in the history of the Southern United States that extended from the conclusion of the War of 1812 to the start of the American Civil War in 1861. This era was marked by the prevalent practi ...

. As a panel of historians emphasized in 2011, "while slavery and its various and multifaceted discontents were the primary cause of disunion, it was disunion itself that sparked the war."

Lincoln's election

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

won the

1860 presidential election

United States presidential election, Presidential elections were held in the United States on November 6, 1860. The History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party ticket of Abraham Lincoln and Hannibal Hamlin emerged victoriou ...

. Southern leaders feared Lincoln would stop slavery's expansion and put it on a course toward extinction. His victory triggered declarations of

secession

Secession is the formal withdrawal of a group from a Polity, political entity. The process begins once a group proclaims an act of secession (such as a declaration of independence). A secession attempt might be violent or peaceful, but the goal i ...

by seven slave states of the

Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion of the Southern United States. The term is used to describe the states which were most economically dependent on Plantation complexes in the Southern United States, plant ...

, all of whose riverfront or coastal economies were based on cotton that was cultivated by slave labor.

Lincoln was not inaugurated until March 4, 1861, four months after his 1860 election, which afforded the South time to prepare for war.

Nationalists in the North and "Unionists" in the South refused to accept the declarations of secession, and no foreign government ever recognized the

Confederacy. The

U.S. government

The Federal Government of the United States of America (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States.

The U.S. federal government is composed of three distinct branches: legislative, executi ...

, under President

James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was the 15th president of the United States, serving from 1857 to 1861. He also served as the United States Secretary of State, secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and represented Pennsylvan ...

, refused to relinquish the nation's forts, which the Confederacy claimed were located in their territory.

According to Lincoln, the American people had demonstrated, beginning with their victory in the

American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

and

Revolutionary War and subsequent establishment of a sovereign nation, that they could successfully establish and administer a republic. Yet, Lincoln believed, a question remained unanswered: Could the nation be maintained as a republic, where its government was selected based on the people's vote, given ongoing internal attempts to destroy or separate from such a system.

Outbreak of the war

Secession crisis

Lincoln's election provoked

South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

's legislature to call a state convention to consider secession. South Carolina had done more than any other state to advance the notion that a state had the right to

nullify federal laws and even secede. On December 20, 1860, the convention unanimously voted to secede and adopted

a secession declaration. It argued for states' rights for slave owners but complained about states' rights in the North in the form of resistance to the federal Fugitive Slave Act, claiming that Northern states were not fulfilling their obligations to assist in the return of fugitive slaves. The "cotton states" of

Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

,

Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

,

Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

,

Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

,

Louisiana

Louisiana ( ; ; ) is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It borders Texas to the west, Arkansas to the north, and Mississippi to the east. Of the 50 U.S. states, it ranks 31st in area and 25 ...

, and

Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

followed suit, seceding in January and February 1861.

Among the ordinances of secession, those of Texas, Alabama, and Virginia mentioned the plight of the "slaveholding states" at the hands of Northern abolitionists. The rest made no mention of slavery but were brief announcements by the legislatures of the dissolution of ties to the Union. However, at least four—South Carolina, Mississippi, Georgia, and Texas—provided detailed reasons for their secession, all blaming the movement to abolish slavery and its influence over the North. Southern states believed that the

Fugitive Slave Clause

The Fugitive Slave Clause in the United States Constitution, also known as either the Slave Clause or the Fugitives From Labor Clause, is Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3, which requires a "Person held to Service or Labour" (usually a slave, appr ...

made slaveholding a constitutional right. These states agreed to form a new federal government, the

Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), also known as the Confederate States (C.S.), the Confederacy, or Dixieland, was an List of historical unrecognized states and dependencies, unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United State ...

, on February 4, 1861. They took control of federal forts and other properties within their boundaries, with little resistance from outgoing president

James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was the 15th president of the United States, serving from 1857 to 1861. He also served as the United States Secretary of State, secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and represented Pennsylvan ...

, whose term ended on March 4. Buchanan said the

Dred Scott decision

''Dred Scott v. Sandford'', 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1857), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that held the U.S. Constitution did not extend American citizenship to people of black African descent, and therefore they ...

was proof the Southern states had no reason to secede and that the Union "was intended to be perpetual". He added, however, that "The power by force of arms to compel a State to remain in the Union" was not among the "enumerated powers granted to Congress".

A quarter of the U.S. army—the Texas garrison—was surrendered in February to state forces by its general,

David E. Twiggs, who joined the Confederacy.

As Southerners resigned their Senate and House seats, Republicans could pass projects that had been blocked. These included the

Morrill Tariff

The Morrill Tariff was an increased import tariff in the United States that was adopted on March 2, 1861, during the last two days of the Presidency of James Buchanan, a Democrat. It was the twelfth of the seventeen planks in the platform of the ...

, land grant colleges, a

Homestead Act

The Homestead Acts were several laws in the United States by which an applicant could acquire ownership of Federal lands, government land or the American frontier, public domain, typically called a Homestead (buildings), homestead. In all, mo ...

, a transcontinental railroad, the

National Bank Act

The National Banking Acts of 1863 and 1864 were two United States federal banking acts that established a system of national banks chartered at the federal level, and created the United States National Banking System. They encouraged developmen ...

, authorization of

United States Note

A United States Note, also known as a Legal Tender Note, is a type of Banknote, paper money that was issued from 1862 to 1971 in the United States. Having been current for 109 years, they were issued for longer than any other form of U.S. paper ...

s by the

Legal Tender Act of 1862

The ''Legal Tender Cases'' were two 1871 United States Supreme Court cases that affirmed the constitutionality of paper money. The two cases were '' Knox v. Lee'' and '' Parker v. Davis''.

The U.S. federal government had issued paper money known ...

, the end of

slavery in the District of Columbia

In the District of Columbia, the slave trade was legal from its creation until it was outlawed as part of the Compromise of 1850. That restrictions on slavery in the District were probably coming was a major factor in the retrocession of the Vir ...

, and a ban on slavery in the territories. The

Revenue Act of 1861

The Revenue Act of 1861, formally cited as Act of August 5, 1861, Chap. XLV, 12 Stat. 292', included the first U.S. Federal income tax statute (seSec. 49. The Act, motivated by the need to fund the Civil War, imposed an income tax to be "levied, c ...

introduced

income tax

An income tax is a tax imposed on individuals or entities (taxpayers) in respect of the income or profits earned by them (commonly called taxable income). Income tax generally is computed as the product of a tax rate times the taxable income. Tax ...

to help finance the war.

In December 1860, the

Crittenden Compromise

The Crittenden Compromise was an unsuccessful proposal to permanently enshrine slavery in the United States Constitution, and thereby make it unconstitutional for future congresses to end slavery. It was introduced by United States Senator Jo ...

was proposed to re-establish the

Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise (also known as the Compromise of 1820) was federal legislation of the United States that balanced the desires of northern states to prevent the expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand ...

line, by constitutionally banning slavery in territories to the north of it, while permitting it to the south. The Compromise would likely have prevented secession, but Lincoln and the Republicans rejected it. Lincoln stated that any compromise that would extend slavery would bring down the Union. A

February peace conference met in Washington, proposing a solution similar to the Compromise; it was rejected by Congress. The Republicans proposed the

Corwin Amendment

The Corwin Amendment is a proposed amendment to the United States Constitution that has never been adopted, but owing to the absence of a ratification deadline, could theoretically still be adopted by the state legislatures. It would have shiel ...

, an alternative, not to interfere with slavery where it existed, but the South regarded it as insufficient. The remaining eight slave states rejected pleas to join the Confederacy, following a no-vote in Virginia's First Secessionist Convention on April 4.

On March 4, Lincoln was sworn in as president. In his

inaugural address

In government and politics, inauguration is the process of swearing a person into office and thus making that person the incumbent. Such an inauguration commonly occurs through a formal ceremony or special event, which may also include an inau ...

, he argued that the Constitution was a ''

more perfect union'' than the earlier

Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union

The Articles of Confederation, officially the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, was an agreement and early body of law in the Thirteen Colonies, which served as the nation's first frame of government during the American Revolutio ...

, was a binding contract, and called secession "legally void".

He did not intend to invade Southern states, nor to end slavery where it existed, but he said he would use force to maintain possession of federal property,

including forts, arsenals, mints, and customhouses that had been seized. The government would not try to recover post offices, and if resisted, mail delivery would end at state lines. Where conditions did not allow peaceful enforcement of federal law, U.S. marshals and judges would be withdrawn. No mention was made of bullion lost from mints. He stated that it would be U.S. policy "to collect the duties and imposts"; "there will be no invasion, no using of force against or among the people anywhere" that would justify an armed revolution. His speech closed with a plea for restoration of the bonds of union, famously calling on "the mystic chords of memory" binding the two regions.

The Davis government of the new Confederacy sent delegates to Washington to negotiate a peace treaty. Lincoln rejected negotiations, because he claimed that the Confederacy was not a legitimate government and to make a treaty with it would recognize it as such. Lincoln instead attempted to negotiate directly with the governors of seceded states, whose administrations he continued to recognize.

Complicating Lincoln's attempts to defuse the crisis was Secretary of State

William H. Seward

William Henry Seward (; May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States senator. A determined opp ...

, who had been Lincoln's rival for the Republican

nomination

Nomination is part of the process of selecting a candidate for either election to a public office, or the bestowing of an honor or award. A collection of nominees narrowed from the full list of candidates is a short list.

Political office

In ...

. Embittered by his defeat, Seward agreed to support Lincoln's candidacy only after he was guaranteed the executive office then considered the second most powerful. In the early stages of Lincoln's presidency Seward held little regard for him, due to his perceived inexperience. Seward viewed himself as the de facto head of government, the "

prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

" behind the throne. Seward attempted to engage in unauthorized and indirect negotiations that failed. Lincoln was determined to hold all remaining Union-occupied forts in the Confederacy:

Fort Monroe

Fort Monroe is a former military installation in Hampton, Virginia, at Old Point Comfort, the southern tip of the Virginia Peninsula, United States. It is currently managed by partnership between the Fort Monroe Authority for the Commonwealth o ...

in Virginia,

Fort Pickens

Fort Pickens is a historic pentagonal United States military fort on Santa Rosa Island in the Pensacola, Florida, area. It is named after American Revolutionary War hero Andrew Pickens. It is the largest of four forts built to defend Pensacol ...

,

Fort Jefferson, and

Fort Taylor

The Fort Zachary Taylor Historic State Park, also known simply as Fort Taylor, is a Florida State Park and National Historic Landmark centered on a Civil War-era fort located near the southern tip of Key West, Florida.

History

1845–1900

Co ...

in Florida, and

Fort Sumter

Fort Sumter is a historical Coastal defense and fortification#Sea forts, sea fort located near Charleston, South Carolina. Constructed on an artificial island at the entrance of Charleston Harbor in 1829, the fort was built in response to the W ...

in South Carolina.

Battle of Fort Sumter

The American Civil War began on April 12, 1861, when Confederate forces opened fire on the Union-held Fort Sumter. Fort Sumter is located in the harbor of

Charleston, South Carolina. Its status had been contentious for months. Outgoing president Buchanan had dithered in reinforcing its garrison, commanded by Major

Robert Anderson. Anderson took matters into his own hands and on December 26, 1860, under the cover of darkness, sailed the garrison from the poorly placed

Fort Moultrie

Fort Moultrie is a series of fortifications on Sullivan's Island, South Carolina, built to protect the city of Charleston, South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina. The first fort, formerly named Fort Sullivan, built of Cabbage Pal ...

to the stalwart island Fort Sumter. Anderson's actions catapulted him to hero status in the North. An attempt to resupply the fort on January 9, 1861, failed and nearly started the war then, but an informal truce held. On March 5, Lincoln was informed the fort was low on supplies.

Fort Sumter proved a key challenge to Lincoln's administration. Back-channel dealing by Seward with the Confederates undermined Lincoln's decision-making; Seward wanted to pull out. But a firm hand by Lincoln tamed Seward, who was a staunch Lincoln ally. Lincoln decided holding the fort, which would require reinforcing it, was the only workable option. On April 6, Lincoln informed the Governor of South Carolina that a ship with food but no ammunition would attempt to supply the fort. Historian McPherson describes this win-win approach as "the first sign of the mastery that would mark Lincoln's presidency"; the Union would win if it could resupply and hold the fort, and the South would be the aggressor if it opened fire on an unarmed ship supplying starving men. An April 9 Confederate cabinet meeting resulted in Davis ordering General

P. G. T. Beauregard

Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard (May 28, 1818 – February 20, 1893) was an American military officer known as being the Confederate general who started the American Civil War at the battle of Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861. Today, he is comm ...

to take the fort before supplies reached it.

At 4:30 a.m. on April 12, Confederate forces fired the first of 4,000 shells at the fort; it fell the next day. The loss of Fort Sumter lit a patriotic fire under the North. On April 15,

Lincoln called on the states to field 75,000 militiamen for 90 days; impassioned Union states met the quotas quickly. On May 3, 1861, Lincoln called for an additional 42,000 volunteers for three years.

Shortly after this,

Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

,

Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

,

Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the West South Central region of the Southern United States. It borders Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, Texas to the southwest, and Oklahoma ...

, and

North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

seceded and joined the Confederacy. To reward Virginia, the Confederate capital was moved to

Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, a city in the United States

* Richmond, London, a town in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, England

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town ...

.

Attitude of the border states

Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

,

Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic and South Atlantic states, South Atlantic regions of the United States. It borders Maryland to its south and west, Pennsylvania to its north, New Jersey ...

,

Missouri

Missouri (''see #Etymology and pronunciation, pronunciation'') is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it border ...

,

West Virginia

West Virginia is a mountainous U.S. state, state in the Southern United States, Southern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States.The United States Census Bureau, Census Bureau and the Association of American ...

and

Kentucky

Kentucky (, ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north, West Virginia to the ...

were slave states whose people had divided loyalties to Northern and Southern businesses and family members. Some men enlisted in the

Union Army and others in the Confederate Army.

West Virginia

West Virginia is a mountainous U.S. state, state in the Southern United States, Southern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States.The United States Census Bureau, Census Bureau and the Association of American ...

separated from

Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

and was admitted to the

Union on June 20, 1863, though half its counties were secessionist.

Maryland's territory surrounded

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, and could cut it off from the North. It had anti-Lincoln officials who tolerated anti-army

rioting in Baltimore and the burning of bridges, both aimed at hindering the passage of troops to the South. Maryland's legislature voted overwhelmingly to stay in the Union, but rejected hostilities with its southern neighbors, voting to close Maryland's rail lines to prevent their use for war.

Lincoln responded by establishing

martial law

Martial law is the replacement of civilian government by military rule and the suspension of civilian legal processes for military powers. Martial law can continue for a specified amount of time, or indefinitely, and standard civil liberties ...

and unilaterally suspending

habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a legal procedure invoking the jurisdiction of a court to review the unlawful detention or imprisonment of an individual, and request the individual's custodian (usually a prison official) to ...

in Maryland, along with sending in militia units. Lincoln took control of Maryland and the District of Columbia by seizing prominent figures, including arresting one-third of the members of the

Maryland General Assembly

The Maryland General Assembly is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Maryland that convenes within the State House in Annapolis. It is a bicameral body: the upper chamber, the Maryland Senate, has 47 representatives, and the lower ...

on the day it reconvened.

All were held without trial, with Lincoln ignoring a ruling on June 1, 1861, by Supreme Court Chief Justice

Roger Taney

Roger Brooke Taney ( ; March 17, 1777 – October 12, 1864) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the fifth chief justice of the United States, holding that office from 1836 until his death in 1864. Taney delivered the majority opin ...

, not speaking for the Court, that only Congress could suspend habeas corpus (''

Ex parte Merryman

''Ex parte Merryman'', 17 F. Cas. 144 (C.C.D. Md. 1861) (No. 9487), was a controversial U.S. federal court case during the American Civil War. It was a test of the authority of the President to suspend "the privilege of the wri ...

''). Federal troops imprisoned a Baltimore newspaper editor,

Frank Key Howard

Frank Key Howard (October 25, 1826 – May 29, 1872) (also cited as Francis Key Howard) was an American newspaper editor and journalist. The grandson of Francis Scott Key and Revolutionary War colonel John Eager Howard, Howard was the edit ...

, after he criticized Lincoln in an editorial for ignoring Taney's ruling.

In Missouri, an

elected convention on secession voted to remain in the Union. When pro-Confederate Governor

Claiborne Fox Jackson

Claiborne Fox Jackson (April 4, 1806 – December 6, 1862) was an American politician of the Democratic Party in Missouri. He was elected as the 15th Governor of Missouri, serving from January 3, 1861, until July 31, 1861, when he was for ...

called out the state militia, it was attacked by federal forces under General

Nathaniel Lyon

Nathaniel Lyon (July 14, 1818 – August 10, 1861) was a United States Army officer who was the first Union Army, Union General officer, general to be killed in the American Civil War. He is noted for his actions in Missouri in 1861, at the beginn ...

, who chased the governor and rest of the State Guard to the southwestern corner of Missouri (see

Missouri secession

During the lead-up to the American Civil War, the proposed secession of Missouri from the Union was controversial because of the state's disputed status. The Missouri state convention voted in March 1861, by 98-1, against secession, and was a borde ...

). Early in the war the Confederacy controlled southern Missouri through the

Confederate government of Missouri

The Confederate government of Missouri was a continuation in exile of the government of pro- Confederate Governor Claiborne F. Jackson. It existed until General E. Kirby Smith surrendered all Confederate troops west of the Mississippi River ...

but was driven out after 1862. In the resulting vacuum, the convention on secession reconvened and took power as the Unionist provisional government of Missouri.

Kentucky did not secede, it declared itself neutral. When Confederate forces entered in September 1861, neutrality ended and the state reaffirmed its Union status while maintaining slavery. During an invasion by Confederate forces in 1861, Confederate sympathizers and delegates from 68 Kentucky counties organized the secession Russellville Convention, formed the shadow

Confederate Government of Kentucky

The Confederate government of Kentucky was a government-in-exile, shadow government established for the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Kentucky by a self-constituted group of Confederate States of America, Confederate sympathizer ...

, inaugurated a governor, and Kentucky was admitted into the Confederacy on December 10, 1861. Its jurisdiction extended only as far as Confederate battle lines in the Commonwealth, which at its greatest extent was over half the state, and it went into exile after October 1862.

After Virginia's secession, a

Unionist government in

Wheeling asked 48 counties to vote on an ordinance to create a new state in October 1861. A voter turnout of 34% approved the statehood bill (96% approving). Twenty-four secessionist counties were included in the new state,

and the ensuing guerrilla war engaged about 40,000 federal troops for much of the war. Congress admitted West Virginia to the Union on June 20, 1863. West Virginians provided about 20,000 soldiers to each side in the war.

A Unionist secession attempt occurred in

East Tennessee

East Tennessee is one of the three Grand Divisions of Tennessee defined in state law. Geographically and socioculturally distinct, it comprises approximately the eastern third of the U.S. state of Tennessee. East Tennessee consists of 33 coun ...

, but was suppressed by the Confederacy, which arrested over 3,000 men suspected of loyalty to the Union; they were held without trial.

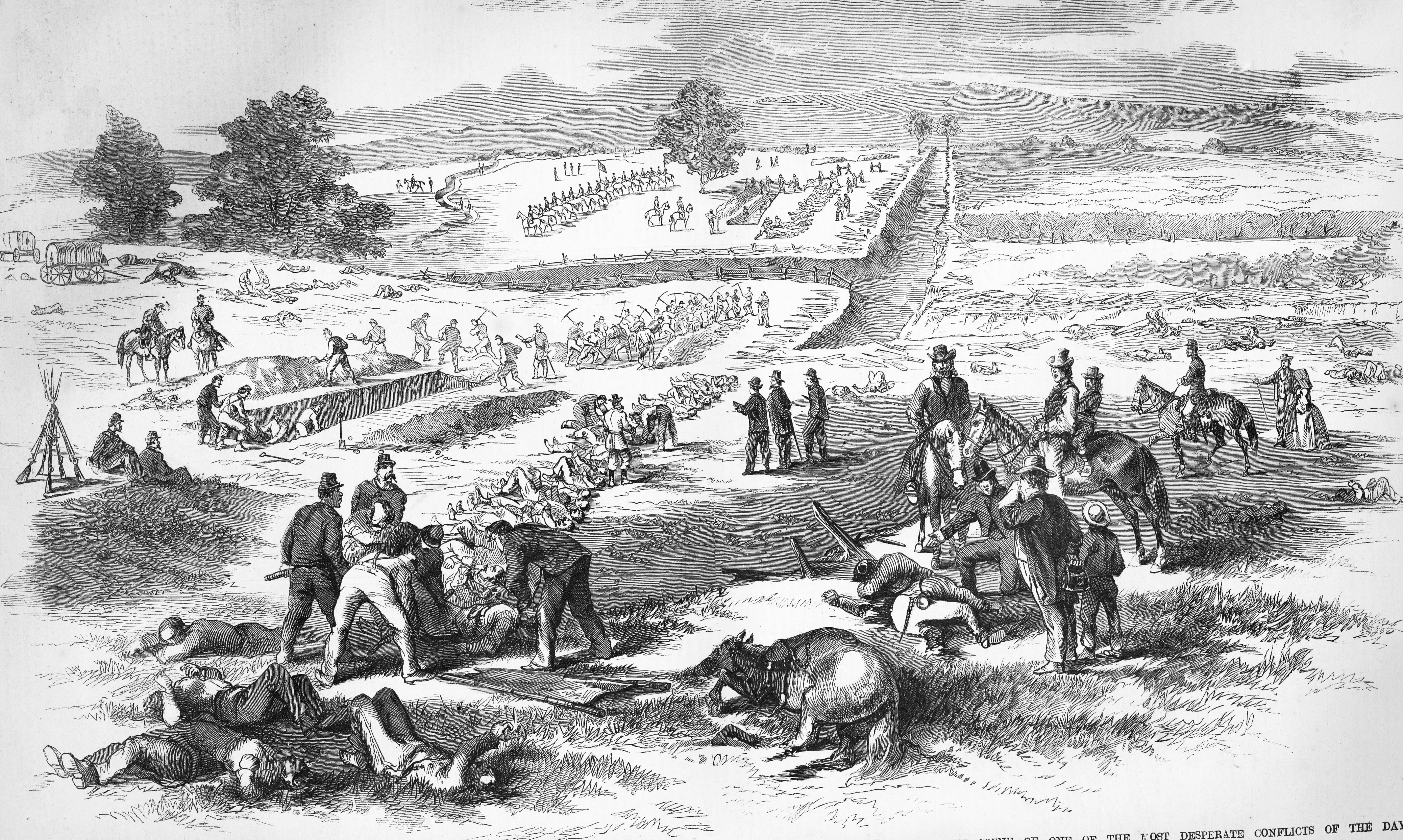

War

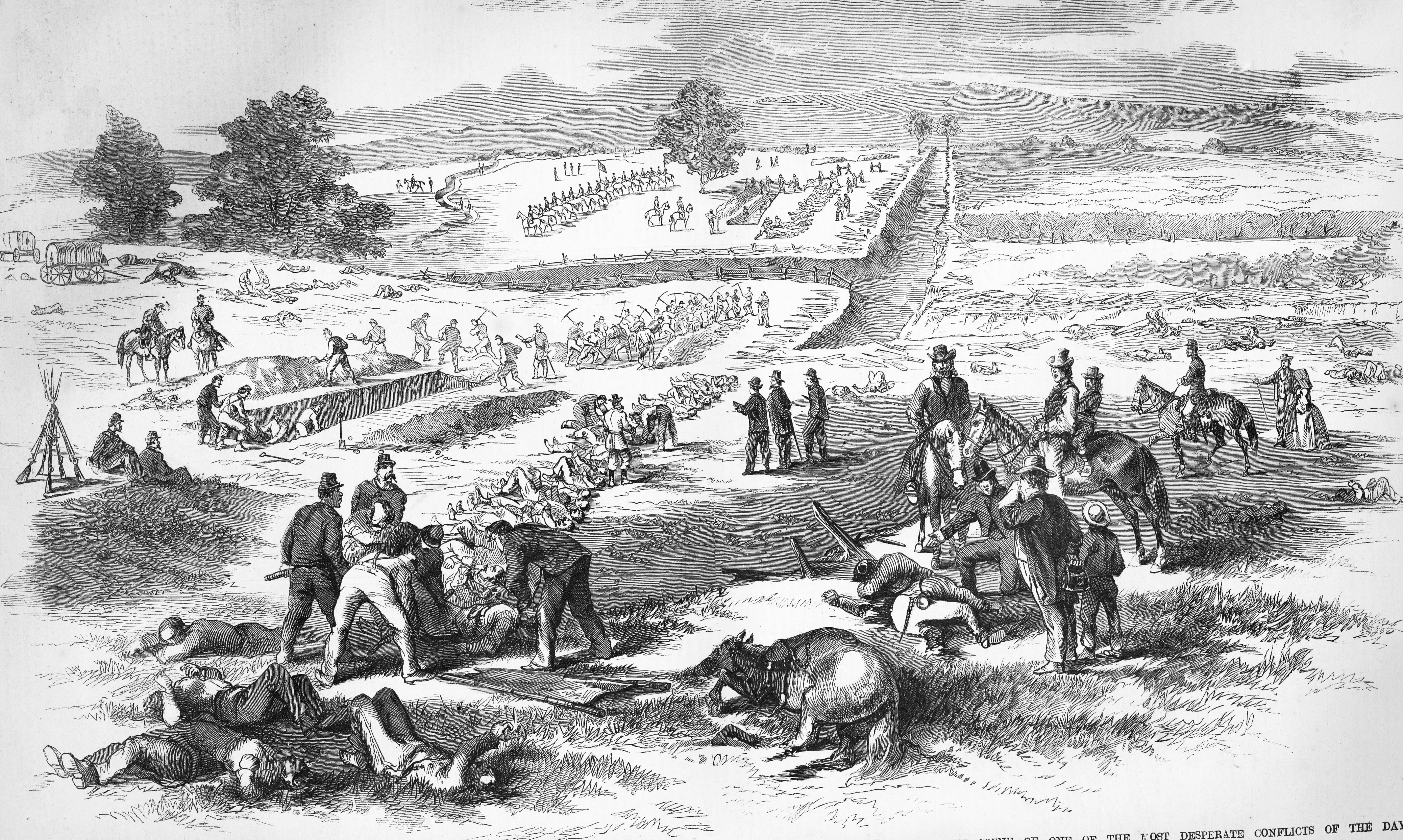

The Civil War was marked by intense and frequent battles. Over four years, 237 named battles were fought, along with many smaller actions, often characterized by their bitter intensity and high casualties. Historian

John Keegan

Sir John Desmond Patrick Keegan (15 May 1934 – 2 August 2012) was an English military historian, lecturer, author and journalist. He wrote many published works on the nature of combat between prehistory and the 21st century, covering land, ...

described it as "one of the most ferocious wars ever fought", where in many cases the only target was the enemy's soldiers.

Mobilization

As the Confederate states organized, the U.S. Army numbered 16,000, while Northern governors began mobilizing their militias. The Confederate Congress authorized up to 100,000 troops in February. By May, Jefferson Davis was pushing for another 100,000 soldiers for one year or the duration, and the U.S. Congress responded in kind.

In the first year of the war, both sides had more volunteers than they could effectively train and equip. After the initial enthusiasm faded, relying on young men who came of age each year was not enough. Both sides enacted draft laws (conscription) to encourage or force volunteering, though relatively few were drafted. The Confederacy passed a draft law in April 1862 for men aged 18–35, with exemptions for overseers, government officials, and clergymen. The U.S. Congress followed in July, authorizing a militia draft within states that could not meet their quota with volunteers. European

immigrants

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not usual residents or where they do not possess nationality in order to settle as permanent residents. Commuters, tourists, and other short- ...

joined the Union Army in large numbers, including 177,000 born in Germany and 144,000 in Ireland. About 50,000 Canadians served, around 2,500 of whom were black.

When the

Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War. The Proclamation had the eff ...

went into effect in January 1863, ex-slaves were energetically recruited to meet state quotas. States and local communities offered higher cash bonuses for white volunteers. Congress tightened the draft law in March 1863. Men selected in the draft could provide substitutes or, until mid-1864, pay commutation money. Many eligibles pooled their money to cover the cost of anyone drafted. Families used the substitute provision to select which man should go into the army and which should stay home. There was much evasion and resistance to the draft, especially in Catholic areas. The

New York City draft riots in July 1863 involved Irish immigrants who had been signed up as citizens to swell the vote of the

city's Democratic political machine, not realizing it made them liable for the draft. Of the 168,649 men procured for the Union through the draft, 117,986 were substitutes, leaving only 50,663 who were conscripted.

In the North and South, draft laws were highly unpopular. In the North, some 120,000 men evaded conscription, many fleeing to Canada, and another 280,000 soldiers deserted during the war. At least 100,000 Southerners deserted, about 10 percent of the total. Southern desertion was high because many soldiers were more concerned about the fate of their local area than the Southern cause. In the North, "

bounty jumper

Bounty jumpers were men who enlisted in the Union or Confederate army during the American Civil War only to collect a bounty and then leave. The Enrollment Act of 1863 instituted conscription but allowed individuals to pay a bounty to someone el ...

s" enlisted to collect the generous bonus, deserted, then re-enlisted under a different name for a second bonus; 141 were caught and executed.

From a tiny frontier force in 1860, the Union and Confederate armies grew into the "largest and most efficient armies in the world" within a few years. Some European observers at the time dismissed them as amateur and unprofessional, but historian John Keegan concluded that each outmatched the French, Prussian, and Russian armies, and without the Atlantic, could have threatened any of them with defeat.

Southern Unionists

Unionism was strong in certain areas within the Confederacy. As many as 100,000 men living in states under Confederate control served in the Union Army or pro-Union guerrilla groups. Although they came from all classes, most Southern Unionists differed socially, culturally, and economically from their region's dominant prewar, slave-owning planter class.

Prisoners

At the war's start, a parole system operated, under which captives agreed not to fight until exchanged. They were held in camps run by their army, paid, but not allowed to perform any military duties. The system of exchanges collapsed in 1863 when the Confederacy refused to exchange black prisoners. After that, about 56,000 of the 409,000 POWs died in prisons, accounting for 10 percent of the conflict's fatalities.

Women

Historian

Elizabeth D. Leonard

Elizabeth D. Leonard is an American historian and the John J. and Cornelia V. Gibson Professor of History at Colby College in Waterville, Maine. Her areas of specialty include American women and the Civil War era.

Education

Leonard earned an ...

writes that between 500 and 1,000 women enlisted as soldiers on both sides, disguised as men. Women also served as spies, resistance activists, nurses, and hospital personnel. Women served on the Union hospital ship ''

Red Rover

Red Rover (also known as the king's run and forcing the city gates) is a team game played primarily by children on playgrounds, requiring 10+ players.

The game has changed over several decades, evolving from a regular "running across" game, wit ...

'' and nursed Union and Confederate troops at field hospitals.

Mary Edwards Walker

Mary Edwards Walker (November 26, 1832 – February 21, 1919), commonly referred to as Dr. Mary Walker, was an American abolitionist, prohibitionist, prisoner of war in the American Civil War, and surgeon. She is the only woman to receive the ...

, the only woman ever to receive the

Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest Awards and decorations of the United States Armed Forces, military decoration and is awarded to recognize American United States Army, soldiers, United States Navy, sailors, Un ...

, served in the Union Army and was given the medal for treating the wounded during the war. One woman, Jennie Hodgers, fought for the Union under the name Albert D. J. Cashier. After she returned to civilian life, she continued to live as a man until she died in 1915 at the age of 71.

Union Navy

The

Union Navy in 1861 was relatively small but, by 1865, expanded rapidly to 6,000 officers, 45,000 sailors, and 671 vessels totaling 510,396 tons. Its mission was to blockade Confederate ports, control the river system, defend against Confederate raiders on the high seas, and be ready for a possible war with the British

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

. The main riverine war was fought in the West, where major rivers gave access to the Confederate heartland. The U.S. Navy eventually controlled the Red, Tennessee, Cumberland, Mississippi, and Ohio rivers. In the East, the Navy shelled Confederate forts and supported coastal army operations.

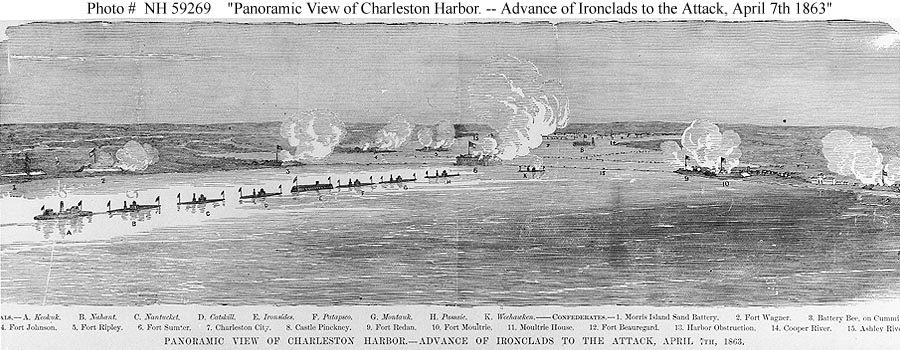

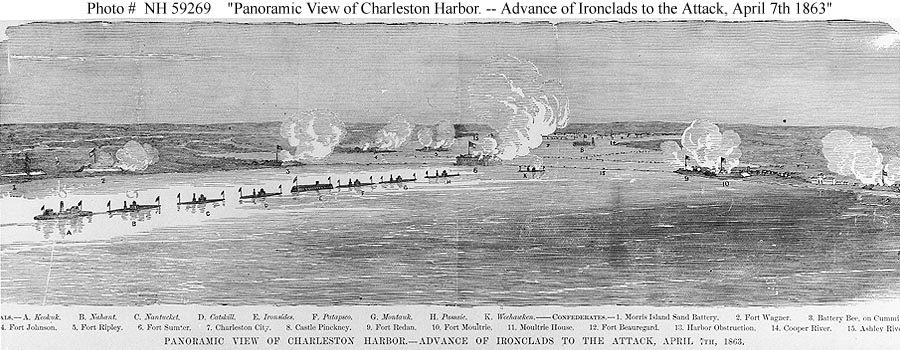

The Civil War occurred during the early stages of the

industrial revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

, leading to naval innovations, including the

ironclad warship

An ironclad was a steam-propelled warship protected by steel or iron armor constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships to explosive or incendiary shells. The firs ...

. The Confederacy, recognizing the need to counter the Union's naval superiority, built or converted over 130 vessels, including 26 ironclads. Despite these efforts, Confederate ships were largely unsuccessful against Union ironclads. The Union Navy used timberclads, tinclads, and armored gunboats. Shipyards in

Cairo, Illinois

Cairo ( , sometimes ) is the southernmost city in the U.S. state of Illinois and the county seat of Alexander County, Illinois, Alexander County. A river city, Cairo has the lowest elevation of any location in Illinois and is the only Illinoi ...

, and

St. Louis

St. Louis ( , sometimes referred to as St. Louis City, Saint Louis or STL) is an independent city in the U.S. state of Missouri. It lies near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a populatio ...

built or modified

steamboat

A steamboat is a boat that is marine propulsion, propelled primarily by marine steam engine, steam power, typically driving propellers or Paddle steamer, paddlewheels. The term ''steamboat'' is used to refer to small steam-powered vessels worki ...

s.

The Confederacy experimented with the submarine , which proved unsuccessful, and with the ironclad , rebuilt from the sunken Union ship . On March 8, 1862, ''Virginia'' inflicted significant damage on the Union's wooden fleet, but the next day, the first Union ironclad, , arrived to challenge it in the

Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula, including parts of the Ea ...

. The resulting three-hour

Battle of Hampton Roads

The Battle of Hampton Roads, also referred to as the Battle of the ''Monitor'' and ''Merrimack'' or the Battle of Ironclads, was a naval battle during the American Civil War.

The battle was fought over two days, March 8 and 9, 1862, in Hampton ...

was a draw, proving ironclads were effective warships. The Confederacy scuttled the ''Virginia'' to prevent its capture, while the Union built many copies of the ''Monitor''. The Confederacy's efforts to obtain warships from

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

failed, as Britain had no interest in selling warships to a nation at war with a stronger enemy and feared souring relations with the U.S.

Union blockade

By early 1861, General

Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as Commanding General of the United States Army from 1841 to 1861, and was a veteran of the War of 1812, American Indian Wars, Mexica ...

had devised the

Anaconda Plan

The Anaconda Plan was a strategy outlined by the Union Army for suppressing the Confederacy at the beginning of the American Civil War. Proposed by Union General-in-Chief Winfield Scott, the plan emphasized a Union blockade of the Southern port ...

to win the war with minimal bloodshed, calling for a blockade of the Confederacy to suffocate the South into surrender. Lincoln adopted parts of the plan but opted for a more active war strategy. In April 1861, Lincoln announced a blockade of all Southern ports; commercial ships could not get insurance, ending regular traffic. The South blundered by embargoing cotton exports before the blockade was fully effective; by the time they reversed this decision, it was too late. "

King Cotton

"King Cotton" is a slogan that summarized the strategy used before the American Civil War (of 1861–1865) by secessionists in the southern states (the future Confederate States of America) to claim the feasibility of secession and to prove ther ...

" was dead, as the South could export less than 10% of its cotton. The blockade shut down the ten Confederate seaports with railheads that moved almost all the cotton. By June 1861, warships were stationed off the principal Southern ports, and a year later nearly 300 ships were in service.

Blockade runners

The Confederates began the war short on military supplies, which the agrarian South could not produce. Northern arms manufacturers were restricted by an embargo, ending existing and future contracts with the South. The Confederacy turned to foreign sources, connecting with financiers and companies like

S. Isaac, Campbell & Company and the

London Armoury Company

The London Armoury Company was a London arms manufactory that existed from 1856 until 1866. It was the major arms supplier to the Confederate States of America, Confederacy during the U.S. Civil War. The same company name was used during World ...

in Britain, becoming the Confederacy's main source of arms.

To transport arms safely to the Confederacy, British investors built small, fast, steam-driven

blockade runners

A blockade runner is a merchant vessel used for evading a naval blockade of a port or strait. It is usually light and fast, using stealth and speed rather than confronting the blockaders in order to break the blockade. Blockade runners usual ...

that traded arms and supplies from Britain, through Bermuda, Cuba, and the Bahamas in exchange for high-priced cotton. Many were lightweight and designed for speed, only carrying small amounts of cotton back to England. When the Union Navy seized a blockade runner, the ship and cargo were condemned as a

prize of war

A prize of war (also called spoils of war, bounty or booty) is a piece of enemy property or land seized by a belligerent party during or after a war or battle. This term was used nearly exclusively in terms of captured ships during the 18th and 1 ...

and sold, with proceeds given to the Navy sailors; the captured crewmen, mostly British, were released.

Economic impact

The Southern economy nearly collapsed during the war due to multiple factors, the most notable being severe food shortages, failing railroads, loss of control over key rivers, foraging by Northern armies, and the seizure of animals and crops by Confederate forces. Historians agree the blockade was a major factor in ruining the

Confederate

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a political union of sovereign states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

economy; however, Wise argues blockade runners provided enough of a lifeline to allow

Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a general officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate general during the American Civil War, who was appointed the General in Chief of the Armies of the Confederate ...

, a Confederate general, to continue fighting for additional months, as a result of supplies that included 400,000 rifles, lead, blankets, and boots that Confederate economy could no longer supply.

The Confederate cotton crop became nearly useless, which cut off the Confederacy's primary income source. Critical imports were scarce, and coastal trade also largely ended. The blockade's success was not measured by the few ships, which slipped through, but by the thousands that never tried. European merchant ships could not obtain insurance for their ships and transport, and were too slow to evade the blockade, leading them to cease docking in Confederate ports.

To fight an offensive war, the Confederacy purchased arms in Britain and converted British-built ships into

commerce raider

Commerce raiding is a form of naval warfare used to destroy or disrupt logistics of the enemy on the open sea by attacking its merchant shipping, rather than engaging its combatants or enforcing a blockade against them. Privateering is a fo ...

s, which targeted

United States Merchant Marine

The United States Merchant Marine is an organization composed of United States civilian sailor, mariners and U.S. civilian and federally owned merchant vessels. Both the civilian mariners and the merchant vessels are managed by a combination of ...

ships in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The Confederacy smuggled 600,000 arms, enabling it to continue fighting for two more years. As insurance rates soared, American-flagged ships largely ceased traveling in international waters, though some were reflagged with European flags, which allowed them to continue operating. After the conclusion of the Civil War, the U.S. government demanded Britain reimburse it for the damage caused by blockade runners and raiders outfitted in British ports. Britain paid the U.S. $15 million in 1871, which covered costs associated with commerce raiding but nothing more.

Diplomacy

Although the Confederacy hoped Britain and France would join them against the Union, this was never likely, so they sought to bring them in as mediators. The Union worked to block this and threatened war against any country that recognized the Confederacy. In 1861, Southerners voluntarily embargoed cotton shipments, hoping to start an economic depression in Europe that would force Britain to enter the war, but this failed. Worse, Europe turned to Egypt and India for cotton, which they found superior, hindering the South's postwar recovery.

proved a failure, because Europe had a surplus of cotton, while the 1860–62 crop failures in Europe made the North's grain exports critically important. It also helped turn European opinion against the Confederacy. It was said that "King Corn was more powerful than King Cotton", as U.S. grain increased from a quarter to almost half of British imports. Meanwhile, the war created jobs for arms makers, ironworkers, and ships to transport weapons.

Lincoln's administration initially struggled to appeal to European public opinion. At first, diplomats explained that the U.S. was not committed to ending slavery and emphasized legal arguments about the unconstitutionality of secession. Confederate representatives, however, focused on their struggle for liberty, commitment to free trade, and the essential role of cotton in the European economy. The European aristocracy was "absolutely gleeful in pronouncing the American debacle as proof that the entire experiment in popular government had failed. European government leaders welcomed the fragmentation of the ascendant American Republic." However, a European public with liberal sensibilities remained, which the U.S. sought to appeal to by building connections with the international press. By 1861, Union diplomats like

Carl Schurz

Carl Christian Schurz (; March 2, 1829 – May 14, 1906) was a German-American revolutionary and an American statesman, journalist, and reformer. He migrated to the United States after the German revolutions of 1848–1849 and became a prominent ...

realized emphasizing the war against slavery was the Union's most effective moral asset in swaying European public opinion. Seward was concerned an overly radical case for reunification would distress European merchants with cotton interests; even so, he supported a widespread campaign of public diplomacy.

U.S.

minister to Britain

Charles Francis Adams proved adept and convinced Britain not to challenge the Union blockade. The Confederacy purchased warships from commercial shipbuilders in Britain, with the most famous being the , which caused considerable damage and led to serious

postwar disputes. However, public opinion against slavery in Britain created a political liability for politicians, where the

anti-slavery movement

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was France in 1315, but it was later used in its colonies. T ...

was powerful.

War loomed in late 1861 between the U.S. and Britain over the

''Trent'' Affair, which began when U.S. Navy personnel boarded the British ship and seized two Confederate diplomats. However, London and Washington smoothed this over after Lincoln released the two men.

Prince Albert

Prince Albert most commonly refers to:

*Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (1819–1861), consort of Queen Victoria

*Albert II, Prince of Monaco (born 1958), present head of state of Monaco

Prince Albert may also refer to:

Royalty

* Alb ...

left his deathbed to

issue diplomatic instructions to

Lord Lyons during the ''Trent'' Affair. His request was honored, and, as a result, the British response to the U.S. was toned down, helping avert war. In 1862, the British government considered mediating between the Union and Confederacy, though such an offer would have risked war with the U.S. British prime minister

Lord Palmerston

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston (20 October 1784 – 18 October 1865), known as Lord Palmerston, was a British statesman and politician who served as prime minister of the United Kingdom from 1855 to 1858 and from 1859 to 1865. A m ...

reportedly read ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' three times when deciding what his decision would be.

The Union victory at the

Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam ( ), also called the Battle of Sharpsburg, particularly in the Southern United States, took place during the American Civil War on September 17, 1862, between Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virgi ...

caused the British to delay this decision. The Emancipation Proclamation increased the political liability of supporting the Confederacy. Realizing that Washington could not intervene in

Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

as long as the Confederacy controlled Texas,

France invaded Mexico in 1861 and installed the

Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

Austrian archduke

Maximilian I as emperor. Washington repeatedly protested France's violation of the

Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine is a foreign policy of the United States, United States foreign policy position that opposes European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It holds that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign ...

. Despite sympathy for the Confederacy, France's seizure of Mexico ultimately deterred it from war with the Union. Confederate offers late in the war to end slavery in return for diplomatic recognition were not seriously considered by London or Paris. After 1863, the

Polish revolt against Russia further distracted the European powers and ensured they remained neutral.

Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

supported the Union, largely because it believed the U.S. counterbalanced its geopolitical rival, the UK. In 1863, the

Imperial Russian Navy

The Imperial Russian Navy () operated as the navy of the Russian Tsardom and later the Russian Empire from 1696 to 1917. Formally established in 1696, it lasted until being dissolved in the wake of the February Revolution and the declaration of ...

's Baltic and Pacific fleets wintered in the American ports of New York and San Francisco, respectively.

Eastern theater

The Eastern theater refers to the military operations east of the

Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, are a mountain range in eastern to northeastern North America. The term "Appalachian" refers to several different regions associated with the mountain range, and its surrounding terrain ...

, including Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland, and

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

, the

District of Columbia

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and Federal district of the United States, federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from ...

, and the coastal fortifications and seaports of

North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

.

Background

Army of the Potomac

Maj. Gen.

George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey and as Commanding General of the United States Army from November 1861 to March 186 ...

took command of the Union

Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the primary field army of the Union army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the Battle of ...

on July 26, 1861, and the war began in earnest in 1862. The 1862 Union strategy called for simultaneous advances along four axes:

# McClellan would lead the main thrust in Virginia towards Richmond.

# Ohio forces would advance through Kentucky into Tennessee.

# The Missouri Department would drive south along the Mississippi River.

# The westernmost attack would originate from Kansas.

Army of Northern Virginia

The primary Confederate force in the Eastern theater was the

Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was a field army of the Confederate States Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most often arrayed agains ...

. The Army originated as the

(Confederate) Army of the Potomac, which was organized on June 20, 1861, from all operational forces in Northern Virginia. On July 20 and 21, the

Army of the Shenandoah and forces from the District of Harpers Ferry were added. Units from the

Army of the Northwest were merged into the Army of the Potomac between March 14 and May 17, 1862. The Army of the Potomac was renamed ''Army of Northern Virginia'' on March 14. The

Army of the Peninsula

The Army of the Peninsula or Magruder's ArmyBoatner, Mark Mayo, III. ''The Civil War Dictionary.'' page 501 was a Confederate army early in the American Civil War.

In May 1861, Colonel John B. Magruder was assigned to command operations on the ...

was merged into it on April 12, 1862.

When Virginia declared its secession in April 1861,

Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a general officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate general during the American Civil War, who was appointed the General in Chief of the Armies of the Confederate ...

chose to follow his home state, despite his desire for the country to remain intact and an offer of a senior Union command. In his four-volume biography of Lee published in 1934 and 1935, historian

Douglas S. Freeman

Douglas Southall Freeman (May 16, 1886 – June 13, 1953) was an American historian, biographer, newspaper editor, radio commentator, and author. He is best known for his multi-volume biographies of Robert E. Lee and George Washington, for both ...

wrote that the army received its final name from Lee when he issued orders assuming command on June 1, 1862. However, Freeman wrote, Lee corresponded with Brigadier General

Joseph E. Johnston

Joseph Eggleston Johnston (February 3, 1807 – March 21, 1891) was an American military officer who served in the United States Army during the Mexican–American War (1846–1848) and the Seminole Wars. After Virginia declared secession from ...

, his predecessor in army command, before that date and referred to Johnston's command as the Army of Northern Virginia. Part of the confusion results from the fact that Johnston commanded the Department of Northern Virginia as of October 22, 1861, and the name Army of Northern Virginia was seen as an informal consequence of its parent department's name. Jefferson Davis and Johnston did not adopt the name, but the organization of units as of March 14 was clearly the same organization that Lee received on June 1, and is generally referred to as the Army of Northern Virginia, even if that is correct only in retrospect.

On July 4 at Harper's Ferry, Colonel

Thomas J. Jackson

Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson (January 21, 1824 – May 10, 1863) was a Confederate general and military officer who served during the American Civil War. He played a prominent role in nearly all military engagements in the eastern thea ...

assigned

Jeb Stuart

James Ewell Brown "Jeb" Stuart (February 6, 1833May 12, 1864) was a Confederate cavalry general during the American Civil War. He was known to his friends as "Jeb,” from the initials of his given names. Stuart was a cavalry commander known f ...