Sea Battle on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Naval warfare is combat in and on the sea, the ocean, or any other

Naval warfare is combat in and on the sea, the ocean, or any other

The first recorded sea battle was The Battle of the Delta, the Ancient Egyptians defeated the

The first recorded sea battle was The Battle of the Delta, the Ancient Egyptians defeated the  The

The  The third Persian campaign in 480 BC, under

The third Persian campaign in 480 BC, under  Navies next played a major role in the complicated wars of the successors of

Navies next played a major role in the complicated wars of the successors of

The Vikings also fought several sea battles among themselves. This was normally done by binding the ships on each side together, thus essentially fighting a land battle on the sea. However the fact that the losing side could not easily escape meant that battles tended to be hard and bloody. The

The Vikings also fought several sea battles among themselves. This was normally done by binding the ships on each side together, thus essentially fighting a land battle on the sea. However the fact that the losing side could not easily escape meant that battles tended to be hard and bloody. The

The Sui (581–618) and

The Sui (581–618) and  In the Nusantara archipelago, large ocean going ships of more than 50 m in length and 5.2–7.8 meters

In the Nusantara archipelago, large ocean going ships of more than 50 m in length and 5.2–7.8 meters

Nusa Jawa: Silang Budaya, Bagian 2: Jaringan Asia

'. Jakarta: Gramedia Pustaka Utama. An Indonesian translation of Lombard, Denys (1990). ''Le carrefour javanais. Essai d'histoire globale (The Javanese Crossroads: Towards a Global History) vol. 2''. Paris: Éditions de l'École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales. in 945–946 CE. They arrived at the coast of Tanganyika and The Ming imperial navy defeated a Portuguese navy led by

The Ming imperial navy defeated a Portuguese navy led by  In Korea, the greater range of

In Korea, the greater range of

In ancient China, the first known naval battles took place during the

In ancient China, the first known naval battles took place during the

The late Middle Ages saw the development of the cogs,

The late Middle Ages saw the development of the cogs,  In the 16th century, the Barbary states of North Africa rose to power, becoming a dominant naval power in the Mediterranean Sea due to the

In the 16th century, the Barbary states of North Africa rose to power, becoming a dominant naval power in the Mediterranean Sea due to the  From the middle of the 17th century competition between the expanding English and Dutch commercial fleets came to a head in the

From the middle of the 17th century competition between the expanding English and Dutch commercial fleets came to a head in the

The 18th century developed into a period of seemingly continuous international wars, each larger than the last. At sea, the British and French were bitter rivals; the French aided the fledgling United States in the

The 18th century developed into a period of seemingly continuous international wars, each larger than the last. At sea, the British and French were bitter rivals; the French aided the fledgling United States in the

Trafalgar ushered in the ''

Trafalgar ushered in the ''

In the early 20th century, the modern battleship emerged: a steel-armored ship, entirely dependent on steam propulsion, with a main battery of uniform caliber guns mounted in turrets on the main deck. This type was pioneered in 1906 with which mounted a main battery of ten guns instead of the mixed caliber main battery of previous designs. Along with her main battery, ''Dreadnought'' and her successors retained a secondary battery for use against smaller ships like destroyers and torpedo boats and, later, aircraft.

Dreadnought style battleships dominated fleets in the early 20th century. They would play major parts in both the

In the early 20th century, the modern battleship emerged: a steel-armored ship, entirely dependent on steam propulsion, with a main battery of uniform caliber guns mounted in turrets on the main deck. This type was pioneered in 1906 with which mounted a main battery of ten guns instead of the mixed caliber main battery of previous designs. Along with her main battery, ''Dreadnought'' and her successors retained a secondary battery for use against smaller ships like destroyers and torpedo boats and, later, aircraft.

Dreadnought style battleships dominated fleets in the early 20th century. They would play major parts in both the

online

excerpt

also see

detailed review and summary of world's navie before and during the war

* Sondhaus, Lawrence ''The Great War at Sea: A Naval History of the First World War'' (2014)

online review

excerpt

* Messenger, Charles. ''Reader's Guide to Military History'' (Routledge, 2013) comprehensive guide to historical books on global military & naval history. * Zurndorfer, Harriet. "Oceans of history, seas of change: recent revisionist writing in western languages about China and East Asian maritime history during the period 1500–1630." ''International Journal of Asian Studies'' 13.1 (2016): 61–94. {{Authority control Naval history

Naval warfare is combat in and on the sea, the ocean, or any other

Naval warfare is combat in and on the sea, the ocean, or any other battlespace

Battlespace or battle-space is a term used to signify a unified military strategy to integrate and combine armed forces for the military theatre of operations, including air, information, land, sea, cyber and outer space to achieve milit ...

involving a major body of water such as a large lake or wide river. Mankind has fought battles on the sea for more than 3,000 years. Even in the interior of large landmasses, transportation before the advent of extensive railroads was largely dependent upon rivers, canals, and other navigable waterways.

The latter were crucial in the development of the modern world in Britain, the Low Countries and northern Germany, for they enabled the bulk movement of goods and raw materials without which the Industrial Revolution would not have occurred. Before 1800, war materials were largely moved by river barges or sea vessels and needed a naval defence against enemies.

History

Mankind has fought battles on the sea for more than 3,000 years. Even in the interior of large landmasses, transportation before the advent of extensiverailway

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a pre ...

s was largely dependent upon river

A river is a natural flowing watercourse, usually freshwater, flowing towards an ocean, sea, lake or another river. In some cases, a river flows into the ground and becomes dry at the end of its course without reaching another body of w ...

s, canal

Canals or artificial waterways are waterways or engineered channels built for drainage management (e.g. flood control and irrigation) or for conveyancing water transport vehicles (e.g. water taxi). They carry free, calm surface flo ...

s, and other navigable waterway

A waterway is any navigable body of water. Broad distinctions are useful to avoid ambiguity, and disambiguation will be of varying importance depending on the nuance of the equivalent word in other languages. A first distinction is necessary b ...

s.

The latter were crucial in the development of the modern world in the United Kingdom, America, the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

and northern Germany, because they enabled the bulk movement of goods and raw material, which supported the nascent Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

. Prior to 1750, materials largely moved by river barge or sea vessels. Thus armies, with their exorbitant needs for food, ammunition and fodder, were tied to the river valleys throughout the ages.

Pre-recorded history (Homeric Legends, e.g. Troy

Troy ( el, Τροία and Latin: Troia, Hittite: 𒋫𒊒𒄿𒊭 ''Truwiša'') or Ilion ( el, Ίλιον and Latin: Ilium, Hittite: 𒃾𒇻𒊭 ''Wiluša'') was an ancient city located at Hisarlik in present-day Turkey, south-west of Ç ...

), and classical works such as The ''Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; grc, Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia, ) is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Iliad'', th ...

'' emphasize the sea. The Persian Empire – united and strong – could not prevail against the might of the Athenian

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

fleet combined with that of lesser city states in several attempts to conquer the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

city states. Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their histor ...

's and Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

's power, Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the cla ...

's and even Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

's largely depended upon control of the seas.

So too did the Venetian Republic

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia ...

dominate Italy's city states, thwart the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, and dominate commerce on the Silk Road and the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western Europe, Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa ...

in general for centuries. For three centuries, Vikings

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and ...

raided and pillaged far into central Russia and Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

, and even to distant Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya ( Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

(both via the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

tributaries, Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, and through the Strait of Gibraltar).

Gaining control of the sea has largely depended on a fleet's ability to wage sea battles. Throughout most of naval history, naval warfare revolved around two overarching concerns, namely boarding and anti-boarding. It was only in the late 16th century, when gunpowder technology had developed to a considerable extent, that the tactical focus at sea shifted to heavy ordnance.

Many sea battles through history also provide a reliable source of shipwrecks for underwater archaeology

Underwater archaeology is archaeology practiced underwater. As with all other branches of archaeology, it evolved from its roots in pre-history and in the classical era to include sites from the historical and industrial eras. Its acceptance has ...

. A major example is the exploration

Exploration refers to the historical practice of discovering remote lands. It is studied by geographers and historians.

Two major eras of exploration occurred in human history: one of convergence, and one of divergence. The first, covering most ...

of the wrecks of various warships in the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contin ...

.

Mediterranean Sea

The first recorded sea battle was The Battle of the Delta, the Ancient Egyptians defeated the

The first recorded sea battle was The Battle of the Delta, the Ancient Egyptians defeated the Sea Peoples

The Sea Peoples are a hypothesized seafaring confederation that attacked ancient Egypt and other regions in the East Mediterranean prior to and during the Late Bronze Age collapse (1200–900 BCE).. Quote: "First coined in 1881 by the Fren ...

in a sea battle circa 1175 BC.

As recorded on the temple walls of the mortuary temple of pharaoh Ramesses III

Usermaatre Meryamun Ramesses III (also written Ramses and Rameses) was the second Pharaoh of the Twentieth Dynasty in Ancient Egypt. He is thought to have reigned from 26 March 1186 to 15 April 1155 BC and is considered to be the last great monar ...

at Medinet Habu, this repulsed a major sea invasion near the shores of the eastern Nile Delta using a naval ambush and archers firing from both ships and shore.

Assyria

Assyria ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the ...

n reliefs from the 8th century BC show Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their histor ...

n fighting ships, with two levels of oars, fighting men on a sort of bridge or deck above the oarsmen, and some sort of ram protruding from the bow. No written mention of strategy or tactics seems to have survived.

Josephus Flavius (Antiquities IX 283–287) reports a naval battle between Tyre and the king of Assyria who was aided by the other cities in Phoenicia. The battle took place off the shores of Tyre. Although the Tyrian fleet was much smaller, the Tyrians defeated their enemies.

The

The Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, oth ...

of Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

just used their ships as transport for land armies, but in 664 BC there is a mention of a battle at sea between Corinth

Corinth ( ; el, Κόρινθος, Kórinthos, ) is the successor to an ancient city, and is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Since the 2011 local government refor ...

and its colony city Corcyra

Corfu (, ) or Kerkyra ( el, Κέρκυρα, Kérkyra, , ; ; la, Corcyra.) is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands, and, including its small satellite islands, forms the margin of the northwestern frontier of Greece. The isl ...

.

Ancient descriptions of the Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars (also often called the Persian Wars) were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire and Greek city-states that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world of the ...

were the first to feature large-scale naval operations, not just sophisticated fleet engagements with dozens of trireme

A trireme( ; derived from Latin: ''trirēmis'' "with three banks of oars"; cf. Greek ''triērēs'', literally "three-rower") was an ancient vessel and a type of galley that was used by the ancient maritime civilizations of the Mediterranean S ...

s on each side, but combined land-sea operations. It seems unlikely that all this was the product of a single mind or even of a generation; most likely the period of evolution and experimentation was simply not recorded by history.

After some initial battles while subjugating the Greeks of the Ionian coast, the Persians determined to invade Greece proper. Themistocles

Themistocles (; grc-gre, Θεμιστοκλῆς; c. 524–459 BC) was an Athenian politician and general. He was one of a new breed of non-aristocratic politicians who rose to prominence in the early years of the Athenian democracy. As ...

of Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

estimated that the Greeks would be outnumbered by the Persians on land, but that Athens could protect itself by building a fleet (the famous "wooden walls"), using the profits of the silver

Silver is a chemical element with the symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical ...

mines at Laurium

Laurium or Lavrio ( ell, Λαύριο; grc, Λαύρειον (later ); before early 11th century BC: Θορικός '' Thorikos''; from Middle Ages until 1908: Εργαστήρια ''Ergastiria'') is a town in southeastern part of Attica, Gree ...

to finance them.

The first Persian campaign, in 492 BC, was aborted because the fleet was lost in a storm, but the second, in 490 BC, captured islands in the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi (Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans ...

before landing on the mainland near Marathon. Attacks by the Greek armies repulsed these.

The third Persian campaign in 480 BC, under

The third Persian campaign in 480 BC, under Xerxes I of Persia

Xerxes I ( peo, 𐎧𐏁𐎹𐎠𐎼𐏁𐎠 ; grc-gre, Ξέρξης ; – August 465 BC), commonly known as Xerxes the Great, was the fourth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, ruling from 486 to 465 BC. He was the son and successor of D ...

, followed the pattern of the second in marching the army via the Hellespont while the fleet paralleled them offshore. Near Artemisium

Artemisium or Artemision (Greek: Ἀρτεμίσιον) is a cape in northern Euboea, Greece. The legendary hollow cast bronze statue of Zeus, or possibly Poseidon, known as the '' Artemision Bronze'', was found off this cape in a sunken ship,W ...

, in the narrow channel between the mainland and Euboea

Evia (, ; el, Εύβοια ; grc, Εὔβοια ) or Euboia (, ) is the second-largest Greek island in area and population, after Crete. It is separated from Boeotia in mainland Greece by the narrow Euripus Strait (only at its narrowest poin ...

, the Greek fleet held off multiple assaults by the Persians, the Persians breaking through a first line, but then being flanked by the second line of ships. But the defeat on land at Thermopylae

Thermopylae (; Ancient Greek and Katharevousa: (''Thermopylai'') , Demotic Greek (Greek): , (''Thermopyles'') ; "hot gates") is a place in Greece where a narrow coastal passage existed in antiquity. It derives its name from its hot sulphur ...

forced a Greek withdrawal, and Athens evacuated its population to nearby Salamis Island.

The ensuing Battle of Salamis was one of the decisive engagements of history. Themistocles trapped the Persians in a channel too narrow for them to bring their greater numbers to bear, and attacked them vigorously, in the end causing the loss of 200 Persian ships vs 40 Greek. Aeschylus

Aeschylus (, ; grc-gre, Αἰσχύλος ; c. 525/524 – c. 456/455 BC) was an ancient Greek tragedian, and is often described as the father of tragedy. Academic knowledge of the genre begins with his work, and understanding of earlier Greek ...

wrote a play about the defeat, ''The Persians

''The Persians'' ( grc, Πέρσαι, ''Persai'', Latinised as ''Persae'') is an Greek tragedy, ancient Greek tragedy written during the Classical Greece, Classical period of Ancient Greece by the Greek tragedian Aeschylus. It is the second and on ...

'', which was performed in a Greek theatre competition a few years after the battle. It is the oldest known surviving play. At the end, Xerxes still had a fleet stronger than the Greeks, but withdrew anyway, and after losing at Plataea in the following year, returned to Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

, leaving the Greeks their freedom. Nevertheless, the Athenians and Spartans attacked and burned the laid-up Persian fleet at Mycale

Mycale (). also Mykale and Mykali ( grc, Μυκάλη, ''Mykálē''), called Samsun Dağı and Dilek Dağı (Dilek Peninsula) in modern Turkey, is a mountain on the west coast of central Anatolia in Turkey, north of the mouth of the Maeander an ...

, and freed many of the Ionian towns. These battles involved triremes or biremes as the standard fighting platform, and the focus of the battle was to ram the opponent's vessel using the boat's reinforced prow. The opponent would try to maneuver and avoid contact, or alternately rush all the marines to the side about to be hit, thus tilting the boat. When the ram had withdrawn and the marines dispersed, the hole would then be above the waterline and not a critical injury to the ship.

During the next fifty years, the Greeks commanded the Aegean, but not harmoniously. After several minor wars, tensions exploded into the Peloponnesian War (431 BC) between Athens' Delian League and the Spartan Peloponnese. Naval strategy was critical; Athens walled itself off from the rest of Greece, leaving only the port at Piraeus

Piraeus ( ; el, Πειραιάς ; grc, Πειραιεύς ) is a port city within the Athens urban area ("Greater Athens"), in the Attica region of Greece. It is located southwest of Athens' city centre, along the east coast of the Saron ...

open, and trusting in its navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It in ...

to keep supplies flowing while the Spartan army besieged it. This strategy worked, although the close quarters likely contributed to the plague that killed many Athenians in 429 BC.

There were a number of sea battles between galleys; at Rhium

Rio ( el, Ρίο, ''Río'', formerly , ''Rhíon''; Latin: ''Rhium'') is a town in the suburbs of Patras and a former municipality in Achaea, West Greece, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Patras, of ...

, Naupactus

Nafpaktos ( el, Ναύπακτος) is a town and a former municipality in Aetolia-Acarnania, West Greece, situated on a bay on the north coast of the Gulf of Corinth, west of the mouth of the river Mornos.

It is named for Naupaktos (, Latini ...

, Pylos, Syracuse, Cynossema, Cyzicus

Cyzicus (; grc, Κύζικος ''Kúzikos''; ota, آیدینجق, ''Aydıncıḳ'') was an ancient Greek town in Mysia in Anatolia in the current Balıkesir Province of Turkey. It was located on the shoreward side of the present Kapıdağ Peni ...

, Notium

Notion or Notium (Ancient Greek , 'southern') was a Greek city-state on the west coast of Anatolia; it is about south of Izmir in modern Turkey, on the Gulf of Kuşadası. Notion was located on a hill from which the sea was visible; it served ...

. But the end came for Athens in 405 BC at Aegospotami

Aegospotami ( grc, Αἰγὸς Ποταμοί, ''Aigos Potamoi'') or AegospotamosMish, Frederick C., Editor in Chief. “Aegospotami.” '' Webster’s Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary''. 9th ed. Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster Inc., 1985. , (in ...

in the Hellespont, where the Athenians had drawn up their fleet on the beach, and were surprised by the Spartan fleet, who landed and burned all the ships. Athens surrendered to Sparta in the following year.

Navies next played a major role in the complicated wars of the successors of

Navies next played a major role in the complicated wars of the successors of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

.

The Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

had never been much of a seafaring nation, but it had to learn. In the Punic Wars with Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the cla ...

, Romans developed the technique of grappling and boarding enemy ships with soldiers. The Roman Navy grew gradually as Rome became more involved in Mediterranean politics; by the time of the Roman Civil War

This is a list of civil wars and organized civil disorder, revolts and rebellions in ancient Rome (Roman Kingdom, Roman Republic, and Roman Empire) until the fall of the Western Roman Empire (753 BCE – 476 CE). For the Eastern Roman Empire or B ...

and the Battle of Actium

The Battle of Actium was a naval battle fought between a maritime fleet of Octavian led by Marcus Agrippa and the combined fleets of both Mark Antony and Cleopatra VII Philopator. The battle took place on 2 September 31 BC in the Ionian Sea, ...

(31 BC), hundreds of ships were involved, many of them quinqueremes mounting catapults and fighting towers. Following the Emperor Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

transforming the Republic into the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediter ...

, Rome gained control of most of the Mediterranean. Without any significant maritime enemies, the Roman navy was reduced mostly to patrolling for pirate

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

s and transportation duties. It was only on the fringes of the Empire, in newly gained provinces or defensive missions against barbarian invasion, that the navy still engaged in actual warfare.

Europe, Western Asia, and Northern Africa

While the barbarian invasions of the 4th century and later mostly occurred by land, some notable examples of naval conflicts are known. In the late 3rd century, in the reign of EmperorGallienus

Publius Licinius Egnatius Gallienus (; c. 218 – September 268) was Roman emperor with his father Valerian from 253 to 260 and alone from 260 to 268. He ruled during the Crisis of the Third Century that nearly caused the collapse of the empi ...

, a large raiding party composed by Goths, Gepids and Heruli, launched itself in the Black Sea, raiding the coasts of Anatolia and Thrace, and crossing into the Aegean Sea, plundering mainland Greece (including Athens and Sparta) and going as far as Crete and Rhodes. In the twilight of the Roman Empire in the late 4th century, examples include that of Emperor Majorian, who, with the help of Constantinople, mustered a large fleet in a failed effort to expel the Germanic invaders from their recently conquered African territories, and a defeat of an Ostrogothic

The Ostrogoths ( la, Ostrogothi, Austrogothi) were a Roman-era Germanic people. In the 5th century, they followed the Visigoths in creating one of the two great Gothic kingdoms within the Roman Empire, based upon the large Gothic populations who ...

fleet at Sena Gallica

Sena may refer to:

Places

* Sanandaj or Sena, city in northwestern Iran

* Sena (state constituency), represented in the Perlis State Legislative Assembly

* Sena, Dashtestan, village in Bushehr Province, Iran

* Sena, Huesca, municipality in Hues ...

in the Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to t ...

.

During the Muslim conquests

The early Muslim conquests or early Islamic conquests ( ar, الْفُتُوحَاتُ الإسْلَامِيَّة, ), also referred to as the Arab conquests, were initiated in the 7th century by Muhammad, the main Islamic prophet. He estab ...

of the 7th century, Muslim fleets first appeared, raiding Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

in 652 (see History of Islam in southern Italy

The history of Islam in Sicily and Southern Italy began with the first Arab settlement in Sicily, at Mazara, which was captured in 827. The subsequent rule of Sicily and Malta started in the 10th century. The Emirate of Sicily lasted from 831 ...

and Emirate of Sicily), and defeating the Byzantine Navy in 655. Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya ( Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

was saved from a prolonged Arab siege in 678 by the invention of Greek fire, an early form of flamethrower that was devastating to the ships in the besieging fleet. These were the first of many encounters during the Byzantine-Arab Wars.

The Caliphate

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

, or , became the dominant naval power in the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

from the 7th to 13th centuries, during what is known as the Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

. One of the most significant inventions in medieval naval warfare was the torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, and with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, s ...

, invented in Syria by the Arab inventor Hasan al-Rammah in 1275. His torpedo ran on water with a rocket

A rocket (from it, rocchetto, , bobbin/spool) is a vehicle that uses jet propulsion to accelerate without using the surrounding air. A rocket engine produces thrust by reaction to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entirely fr ...

system filled with explosive gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). Th ...

materials and had three firing points. It was an effective weapon against ship

A ship is a large watercraft that travels the world's oceans and other sufficiently deep waterways, carrying cargo or passengers, or in support of specialized missions, such as defense, research, and fishing. Ships are generally distinguished ...

s.

In the 8th century the Vikings

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and ...

appeared, although their usual style was to appear quickly, plunder, and disappear, preferably attacking undefended locations. The Vikings raided places along the coastline of England and France, with the greatest threats being in England. They would raid monasteries for their wealth and lack of formidable defenders. They also utilized rivers and other auxiliary waterways to work their way inland in the eventual invasion of Britain. They wreaked havoc in Northumbria and Mercia and the rest of Anglia before being halted by Wessex. King Alfred the Great of England was able to stay the Viking invasions with a pivotal victory at the Battle of Edington. Alfred defeated Guthrum, establishing the boundaries of Danelaw

The Danelaw (, also known as the Danelagh; ang, Dena lagu; da, Danelagen) was the part of England in which the laws of the Danes held sway and dominated those of the Anglo-Saxons. The Danelaw contrasts with the West Saxon law and the Mercian ...

in an 884 treaty. The effectiveness of Alfred's 'fleet' has been debated; Dr. Kenneth Harl has pointed out that as few as eleven ships were sent to combat the Vikings, only two of which were not beaten back or captured. (Link?)

The Vikings also fought several sea battles among themselves. This was normally done by binding the ships on each side together, thus essentially fighting a land battle on the sea. However the fact that the losing side could not easily escape meant that battles tended to be hard and bloody. The

The Vikings also fought several sea battles among themselves. This was normally done by binding the ships on each side together, thus essentially fighting a land battle on the sea. However the fact that the losing side could not easily escape meant that battles tended to be hard and bloody. The Battle of Svolder

The Battle of Svolder (''Svold'' or ''Swold'') was a large naval battle during the Viking age, fought in September 999 or 1000 in the western Baltic Sea between Olaf Tryggvason, King Olaf of Norway and an alliance of the Kings of Denmark and Swe ...

is perhaps the most famous of these battles.

As Muslim power in the Mediterranean began to wane, the Italian trading towns of Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

, Pisa, and Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 bridges. The isla ...

stepped in to seize the opportunity, setting up commercial networks and building navies to protect them. At first the navies fought with the Arabs (off Bari in 1004, at Messina in 1005), but then they found themselves contending with Normans

The Normans ( Norman: ''Normaunds''; french: Normands; la, Nortmanni/Normanni) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norse Viking settlers and indigenous West Franks and Gallo-Romans. ...

moving into Sicily, and finally with each other. The Genoese and Venetians fought four naval wars, in 1253–1284, 1293–1299,

1350–1355, and 1378–1381. The last ended with a decisive Venetian victory, giving it almost a century to enjoy Mediterranean trade domination before other European countries began expanding into the south and west.

In the north of Europe, the near-continuous conflict between England and France was characterised by raids on coastal towns and ports along the coastlines and the securing of sea lanes to protect troop–carrying transports. The Battle of Dover in 1217, between a French fleet of 80 ships under Eustace the Monk

Eustace the Monk ( fro, Eustache le Moine; c. 1170 – 24 August 1217), born Eustace Busket,Knight 1997,. was a mercenary and pirate, in the tradition of medieval outlaws. The birthplace of Eustace was not far from Boulogne. A 1243 document m ...

and an English fleet of 40 under Hubert de Burgh

Hubert de Burgh, Earl of Kent (; ; ; c.1170 – before 5 May 1243) was an English nobleman who served as Chief Justiciar of England and Ireland during the reigns of King John and of his son and successor King Henry III and, as a consequenc ...

, is notable as the first recorded battle using sailing ship tactics. The battle of Arnemuiden

The Battle of Arnemuiden was a naval battle fought on 23 September 1338 at the start of the Hundred Years' War between England and France. It was the first naval battle of the Hundred Years' War and the first recorded European naval battle usi ...

(23 September 1338), which resulted in a French victory, marked the opening of the Hundred Years War and was the first battle involving artillery. However the battle of Sluys

The Battle of Sluys (; ), also called the Battle of l'Écluse, was a naval battle fought on 24 June 1340 between England and France. It took place in the roadstead of the port of Sluys (French ''Écluse''), on a since silted-up inlet between ...

, fought two years later, saw the destruction of the French fleet in a decisive action which allowed the English effective control of the sea lanes and the strategic initiative for much of the war.

Eastern, Southern, and Southeast Asia

The Sui (581–618) and

The Sui (581–618) and Tang

Tang or TANG most often refers to:

* Tang dynasty

* Tang (drink mix)

Tang or TANG may also refer to:

Chinese states and dynasties

* Jin (Chinese state) (11th century – 376 BC), a state during the Spring and Autumn period, called Tang (唐) b ...

(618–907) dynasties of China were involved in several naval affairs over the triple set of polities ruling medieval Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

(Three Kingdoms of Korea

Samhan or the Three Kingdoms of Korea () refers to the three kingdoms of Goguryeo (고구려, 高句麗), Baekje (백제, 百濟), and Silla (신라, 新羅). Goguryeo was later known as Goryeo (고려, 高麗), from which the modern name ''Kor ...

), along with engaging naval bombardments on the peninsula from Asuka period

The was a period in the history of Japan lasting from 538 to 710 (or 592 to 645), although its beginning could be said to overlap with the preceding Kofun period. The Yamato polity evolved greatly during the Asuka period, which is named after ...

Yamato Kingdom (Japan).

The Tang dynasty aided the Korean kingdom of Silla

Silla or Shilla (57 BCE – 935 CE) ( , Old Korean: Syera, Old Japanese: Siraki2) was a Korean kingdom located on the southern and central parts of the Korean Peninsula. Silla, along with Baekje and Goguryeo, formed the Three Kingdoms ...

(see also Unified Silla

Unified Silla, or Late Silla (, ), is the name often applied to the Korean kingdom of Silla, one of the Three Kingdoms of Korea, after 668 CE. In the 7th century, a Silla–Tang alliance conquered Baekje and the southern part of Goguryeo in the ...

) and expelled the Korean kingdom of Baekje

Baekje or Paekche (, ) was a Korean kingdom located in southwestern Korea from 18 BC to 660 AD. It was one of the Three Kingdoms of Korea, together with Goguryeo and Silla.

Baekje was founded by Onjo, the third son of Goguryeo's founder Jum ...

with the aid of Japanese naval forces from the Korean peninsula (see Battle of Baekgang) and conquered Silla's Korean rivals, Baekje

Baekje or Paekche (, ) was a Korean kingdom located in southwestern Korea from 18 BC to 660 AD. It was one of the Three Kingdoms of Korea, together with Goguryeo and Silla.

Baekje was founded by Onjo, the third son of Goguryeo's founder Jum ...

and Goguryeo

Goguryeo (37 BC–668 AD) ( ) also called Goryeo (), was a Korean kingdom located in the northern and central parts of the Korean Peninsula and the southern and central parts of Northeast China. At its peak of power, Goguryeo controlled mos ...

by 668. In addition, the Tang had maritime trading, tributary, and diplomatic ties as far as modern Sri Lanka, India, Islamic Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

and Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plat ...

, as well as Somalia

Somalia, , Osmanya script: 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒕𐒖; ar, الصومال, aṣ-Ṣūmāl officially the Federal Republic of SomaliaThe ''Federal Republic of Somalia'' is the country's name per Article 1 of thProvisional Constituti ...

in East Africa.

From the Axumite

The Kingdom of Aksum ( gez, መንግሥተ አክሱም, ), also known as the Kingdom of Axum or the Aksumite Empire, was a kingdom centered in Northeast Africa and South Arabia from Classical antiquity to the Middle Ages. Based primarily in wha ...

Kingdom in modern-day Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

, the Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

traveller Sa'd ibn Abi-Waqqas sailed from there to Tang China during the reign of Emperor Gaozong. Two decades later, he returned with a copy of the Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , s ...

, establishing the first Islamic mosque

A mosque (; from ar, مَسْجِد, masjid, ; literally "place of ritual prostration"), also called masjid, is a place of prayer for Muslims. Mosques are usually covered buildings, but can be any place where prayers ( sujud) are performed, ...

in China, the Mosque of Remembrance in Guangzhou

Guangzhou (, ; ; or ; ), also known as Canton () and alternatively romanized as Kwongchow or Kwangchow, is the capital and largest city of Guangdong province in southern China. Located on the Pearl River about north-northwest of Hong Kon ...

. A rising rivalry followed between the Arabs and Chinese for control of trade in the Indian Ocean. In his book ''Cultural Flow Between China and the Outside World'', Shen Fuwei notes that maritime Chinese merchants in the 9th century were landing regularly at Sufala in East Africa to cut out Arab middle-men traders.Shen, 155

The Chola dynasty

The Chola dynasty was a Tamil thalassocratic empire of southern India and one of the longest-ruling dynasties in the history of the world. The earliest datable references to the Chola are from inscriptions dated to the 3rd century BCE ...

of medieval India was a dominant seapower in the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by t ...

, an avid maritime trader and diplomatic entity with Song China. Rajaraja Chola I (reigned 985 to 1014) and his son Rajendra Chola I (reigned 1014–42), sent a great naval expedition that occupied parts of Myanmar

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

, Malaya, and Sumatra. In the Nusantara archipelago, large ocean going ships of more than 50 m in length and 5.2–7.8 meters

In the Nusantara archipelago, large ocean going ships of more than 50 m in length and 5.2–7.8 meters freeboard

In sailing and boating, a vessel's freeboard

is the distance from the waterline to the upper deck level, measured at the lowest point of sheer where water can enter the boat or ship. In commercial vessels, the latter criterion measured relativ ...

are already used at least since the 2nd century AD, contacting India to China. Srivijaya empire since the 7th century AD controlled the sea of the western part of the archipelago. The Kedukan Bukit inscription

The Kedukan Bukit inscription is an inscription discovered by the Dutchman C.J. Batenburg on 29 November 1920 at Kedukan Bukit, South Sumatra, Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), on the banks of Tatang River, a tributary of Musi River. It is the ...

is the oldest record of Indonesian military history, and noted a 7th-century Srivijayan sacred ''siddhayatra'' journey led by Dapunta Hyang Sri Jayanasa

Dapunta Hyang Sri Jayanasa () was the first Maharaja (Emperor) of Srivijaya and thought to be the dynastic founder of Kadatuan Srivijaya. His name was mentioned in the series of Srivijayan inscriptions dated from late 7th century CE dubbed as the ...

. He was said to have brought 20,000 troops, including 312 people in boats and 1,312 foot soldiers. The 10th century Arab text ''Ajayeb al-Hind'' (Marvels of India) gives an account of an invasion in Africa by people called Wakwak or Waqwaq

Al-Wakwak ( ar, ٱلْوَاق وَاق '), also spelled al-Waq Waq, Wak al-Wak or just Wak Wak, is the name of an island, or possibly more than one island, in medieval Arabic geographical and imaginative literature.

Identification with civi ...

,Kumar, Ann (2012). 'Dominion Over Palm and Pine: Early Indonesia’s Maritime Reach', in Geoff Wade (ed.), ''Anthony Reid and the Study of the Southeast Asian Past'' (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies), 101–122. probably the Malay people of Srivijaya or Javanese people of Mataram kingdom

The Mataram Kingdom (, jv, ꦩꦠꦫꦩ꧀, ) was a Javanese Hindu–Buddhist kingdom that flourished between the 8th and 11th centuries. It was based in Central Java, and later in East Java. Established by King Sanjaya, the kingdom was rule ...

,Lombard, Denys (2005)''Nusa Jawa: Silang Budaya, Bagian 2: Jaringan Asia

'. Jakarta: Gramedia Pustaka Utama. An Indonesian translation of Lombard, Denys (1990). ''Le carrefour javanais. Essai d'histoire globale (The Javanese Crossroads: Towards a Global History) vol. 2''. Paris: Éditions de l'École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales. in 945–946 CE. They arrived at the coast of Tanganyika and

Mozambique

Mozambique (), officially the Republic of Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique or , ; ny, Mozambiki; sw, Msumbiji; ts, Muzambhiki), is a country located in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi ...

with 1000 boats and attempted to take the citadel of Qanbaloh, though eventually failed. The reason of the attack is because that place had goods suitable for their country and for China, such as ivory, tortoise shells, panther skins, and ambergris

Ambergris ( or , la, ambra grisea, fro, ambre gris), ''ambergrease'', or grey amber is a solid, waxy, flammable substance of a dull grey or blackish colour produced in the digestive system of sperm whales. Freshly produced ambergris has a mari ...

, and also because they wanted black slaves from Bantu people (called ''Zeng'' or '' Zenj'' by Arabs, ''Jenggi'' by Javanese) who were strong and make good slaves. Before the 12th century, Srivijaya is primarily land-based polity rather than maritime power, fleets are available but acted as logistical support to facilitate the projection of land power. Later, the naval strategy degenerated to raiding fleet. Their naval strategy was to coerce merchant ships to dock in their ports, which if ignored, they will send ships to destroy the ship and kill the occupants.

In 1293, the Mongol Yuan Dynasty

The Yuan dynasty (), officially the Great Yuan (; xng, , , literally "Great Yuan State"), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after its division. It was established by Kublai, the fift ...

launched an invasion to Java

Java (; id, Jawa, ; jv, ꦗꦮ; su, ) is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea to the north. With a population of 151.6 million people, Java is the world's mos ...

. The Yuan sent 500–1000 ships and 20,000–30,000 soldiers, but was ultimately defeated on land by surprise attack, forcing the army to fall back to the beach. In the coastal waters, Javanese junks had already attacked the Mongol ships. After all of the troops had boarded the ships on the coast, the Yuan army battled the Javanese fleet. After repelling it, they sailed back to Quanzhou. Javanese naval commander Aria Adikara intercepted a further Mongol invasion. Although with only scarce information, travellers passing the region, such as Ibn Battuta and Odoric of Pordenone

Odoric of Pordenone, OFM (1286–1331), also known as Odorico Mattiussi/Mattiuzzi, Odoricus of Friuli or Orderic of Pordenone, was an Italian late-medieval Franciscan friar and missionary explorer. He traveled through India, the Greater Sunda Is ...

noted that Java had been attacked by the Mongols several times, always ending in failure. After those failed invasions, Majapahit empire

Majapahit ( jv, ꦩꦗꦥꦲꦶꦠ꧀; ), also known as Wilwatikta ( jv, ꦮꦶꦭ꧀ꦮꦠꦶꦏ꧀ꦠ; ), was a Javanese Hindu-Buddhist thalassocratic empire in Southeast Asia that was based on the island of Java (in modern-day Indonesia) ...

quickly grew and became the dominant naval power in the 14–15th century. The usage of cannons in the Mongol invasion of Java

The Yuan dynasty under Kublai Khan attempted in 1292 to invade Java, an island in modern Indonesia, with 20,000 to 30,000 soldiers. This was intended as a punitive expedition against Kertanegara of Singhasari, who had refused to pay tribute to ...

, led to deployment of cetbang

Cetbang (also known as bedil, warastra, or meriam coak) were cannons produced and used by the Majapahit Empire (1293–1527) and other kingdoms in the Indonesian archipelago. There are 2 main types of cetbang: the eastern-style cetbang which lo ...

cannons by Majapahit fleet in 1300s.Averoes, Muhammad (2020). Antara Cerita dan Sejarah: Meriam Cetbang Majapahit. ''Jurnal Sejarah'', 3(2), 89 - 100. The main warship of Majapahit navy was the jong Jong may refer to:

Surname

*Chung (Korean surname), spelled Jong in North Korea

*Zhong (surname), spelled Jong in the Gwoyeu Romatzyh system

*Common Dutch surname "de Jong"; see

** De Jong

** De Jonge

** De Jongh

*Erica Jong (born 1942), American ...

. The jongs were large transport ships which could carry 100–2000 tons of cargo and 50–1000 people, 28.99–88.56 meter in length. The exact number of jong fielded by Majapahit is unknown, but the largest number of jong deployed in an expedition is about 400 jongs, when Majapahit attacked Pasai, in 1350.Hill (June 1960). " Hikayat Raja-Raja Pasai". ''Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society''. 33: p. 98 and 157: "Then he directed them to make ready all the equipment and munitions of war needed for an attack on the land of Pasai – about four hundred of the largest junks, and also many barges (malangbang) and galleys." See also Nugroho (2011). p. 270 and 286, quoting ''Hikayat Raja-Raja Pasai'', 3: 98: "''Sa-telah itu, maka di-suroh baginda musta'idkan segala kelengkapan dan segala alat senjata peperangan akan mendatangi negeri Pasai itu, sa-kira-kira empat ratus jong yang besar-besar dan lain daripada itu banyak lagi daripada malangbang dan kelulus''." (After that, he is tasked by His Majesty to ready all the equipment and all weapons of war to come to that country of Pasai, about four hundred large jongs and other than that much more of malangbang and kelulus.) In this era, even to the 17th century, the Nusantaran naval soldiers fought on a platform on their ships called ''balai'' and performed boarding actions. Scattershots fired from cetbang are used to counter this type of fighting, fired at personnel.

In the 12th century, China's first permanent standing navy was established by the Southern Song dynasty, the headquarters of the Admiralty stationed at Dinghai

() is a district of Zhoushan City made of 128 islands in Zhejiang province, China.The total area is 1,444 square kilometres.The land area is 568.8 square kilometers, the sea area is 875.2 square kilometers, and the coastline is more than 400 kil ...

. This came about after the conquest of northern China by the Jurchen people

Jurchen (Manchu: ''Jušen'', ; zh, 女真, ''Nǚzhēn'', ) is a term used to collectively describe a number of East Asian Tungusic-speaking peoples, descended from the Donghu people. They lived in the northeast of China, later known as Manchu ...

(see Jin dynasty) in 1127, while the Song imperial court fled south from Kaifeng

Kaifeng () is a prefecture-level city in east-central Henan province, China. It is one of the Eight Ancient Capitals of China, having been the capital eight times in history, and is best known for having been the Chinese capital during the No ...

to Hangzhou

Hangzhou ( or , ; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ), also romanized as Hangchow, is the capital and most populous city of Zhejiang, China. It is located in the northwestern part of the province, sitting at the head of Hangzhou Bay, whic ...

. Equipped with the magnetic compass

A compass is a device that shows the cardinal directions used for navigation and geographic orientation. It commonly consists of a magnetized needle or other element, such as a compass card or compass rose, which can pivot to align itself wit ...

and knowledge of Shen Kuo's famous treatise (on the concept of true north

True north (also called geodetic north or geographic north) is the direction along Earth's surface towards the geographic North Pole or True North Pole.

Geodetic north differs from ''magnetic'' north (the direction a compass points toward t ...

), the Chinese became proficient experts of navigation in their day. They raised their naval strength from a mere 11 squadrons of 3,000 marines to 20 squadrons of 52,000 marines in a century's time.

Employing paddle wheel

A paddle wheel is a form of waterwheel or impeller in which a number of paddles are set around the periphery of the wheel. It has several uses, of which some are:

* Very low-lift water pumping, such as flooding paddy fields at no more than abo ...

crafts and trebuchet

A trebuchet (french: trébuchet) is a type of catapult that uses a long arm to throw a projectile. It was a common powerful siege engine until the advent of gunpowder. The design of a trebuchet allows it to launch projectiles of greater weight ...

s throwing gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). Th ...

bombs from the decks of their ships, the Southern Song dynasty became a formidable foe to the Jin dynasty during the 12th–13th centuries during the Jin–Song Wars

The Jin–Song Wars were a series of conflicts between the Jurchen-led Jin dynasty (1115–1234) and the Han-led Song dynasty (960–1279). In 1115, Jurchen tribes rebelled against their overlords, the Khitan-led Liao dynasty (916–1125), ...

. There were naval engagements at the Battle of Caishi

The Battle of Caishi (, approximately ) was a major naval engagement of the Jin–Song Wars of China that took place on November 26–27, 1161. It ended with a decisive Song victory, aided by their use of gunpowder weapons.

Soldiers under the ...

and Battle of Tangdao

The Battle of Tangdao (唐岛之战) was a naval engagement that took place in 1161 between the Jurchen Jin and the Southern Song Dynasty of China on the East China Sea. The conflict was part of the Jin-Song wars, and was fought near Tangdao I ...

. With a powerful navy, China dominated maritime trade throughout South East Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical south-eastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of mainland ...

as well. Until 1279, the Song were able to use their naval power to defend against the Jin to the north, until the Mongols

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal membe ...

finally conquered all of China. After the Song dynasty, the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty (), officially the Great Yuan (; xng, , , literally "Great Yuan State"), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after its division. It was established by Kublai, the fift ...

of China was a powerful maritime force in the Indian Ocean.

The Yuan emperor Kublai Khan attempted to invade Japan twice with large fleets (of both Mongols and Chinese), in 1274 and again in 1281, both attempts being unsuccessful (see Mongol invasions of Japan

Major military efforts were taken by Kublai Khan of the Yuan dynasty in 1274 and 1281 to conquer the Japanese archipelago after the submission of the Korean kingdom of Goryeo to vassaldom. Ultimately a failure, the invasion attempts are of m ...

). Building upon the technological achievements of the earlier Song dynasty, the Mongols also employed early cannon

A cannon is a large- caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder ...

s upon the decks of their ships.

While Song China built its naval strength, the Japanese also had considerable naval prowess. The strength of Japanese naval forces could be seen in the Genpei War, in the large-scale Battle of Dan-no-ura on 25 April 1185. The forces of Minamoto no Yoshitsune

was a military commander of the Minamoto clan of Japan in the late Heian and early Kamakura periods. During the Genpei War, he led a series of battles which toppled the Ise-Heishi branch of the Taira clan, helping his half-brother Yoritomo conso ...

were 850 ships strong, while Taira no Munemori

was heir to Taira no Kiyomori, and one of the Taira clan's chief commanders in the Genpei War.

As his father Taira no Kasemori uch a name does not existlay on his deathbed, Kiyomori declared, among his last wishes, that all affairs of the cla ...

had 500 ships.

In the mid-14th century, the rebel leader Zhu Yuanzhang

The Hongwu Emperor (21 October 1328 – 24 June 1398), personal name Zhu Yuanzhang (), courtesy name Guorui (), was the founding emperor of the Ming dynasty of China, reigning from 1368 to 1398.

As famine, plagues and peasant revolts i ...

(1328–1398) seized power in the south amongst many other rebel groups. His early success was due to capable officials such as Liu Bowen

Liu Ji (1 July 1311 – 16 May 1375),Jiang, Yonglin. Jiang Yonglin. 005(2005). The Great Ming Code: 大明律. University of Washington Press. , 9780295984490. Page xxxv. The source is used to cover the year only. courtesy name Bowen, better kn ...

and Jiao Yu

Jiao Yu () was a Chinese military general, philosopher, and writer of the Yuan dynasty and early Ming dynasty under Zhu Yuanzhang, who founded the dynasty and became known as the Hongwu Emperor. He was entrusted by Zhu as a leading artillery o ...

, and their gunpowder weapons (see ''Huolongjing

The ''Huolongjing'' (; Wade-Giles: ''Huo Lung Ching''; rendered in English as ''Fire Drake Manual'' or ''Fire Dragon Manual''), also known as ''Huoqitu'' (“Firearm Illustrations”), is a Chinese military treatise compiled and edited by Jiao ...

''). Yet the decisive battle that cemented his success and his founding of the Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last orthodox dynasty of China ruled by the Han peo ...

(1368–1644) was the Battle of Lake Poyang

The Battle of Lake Poyang () was a naval conflict which took place (30 August – 4 October 1363) between the rebel forces of Zhu Yuanzhang and Chen Youliang during the Red Turban Rebellion which led to the fall of the Yuan dynasty. Chen Youlia ...

, considered one of the largest naval battles in history.

In the 15th century, the Chinese admiral Zheng He

Zheng He (; 1371–1433 or 1435) was a Chinese mariner, explorer, diplomat, fleet admiral, and court eunuch during China's early Ming dynasty. He was originally born as Ma He in a Muslim family and later adopted the surname Zheng conferr ...

was assigned to assemble a massive fleet for several diplomatic missions abroad, sailing throughout the waters of the South East Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contine ...

and the Indian Ocean. During his missions, on several occasions Zheng's fleet came into conflict with pirate

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

s. Zheng's fleet also became involved in a conflict in Sri Lanka, where the King of Ceylon traveled back to Ming China afterwards to make a formal apology to the Yongle Emperor

The Yongle Emperor (; pronounced ; 2 May 1360 – 12 August 1424), personal name Zhu Di (), was the third Emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigning from 1402 to 1424.

Zhu Di was the fourth son of the Hongwu Emperor, the founder of the Ming dyn ...

.

The Ming imperial navy defeated a Portuguese navy led by

The Ming imperial navy defeated a Portuguese navy led by Martim Afonso de Sousa

Martim Afonso de Sousa ( – 21 July 1564) was a Portuguese '' fidalgo'', explorer and colonial administrator.

Life

Born in Vila Viçosa, he was commander of the first official Portuguese expedition into mainland of the colony of Brazil. Threate ...

in 1522. The Chinese destroyed one vessel by targeting its gunpowder magazine, and captured another Portuguese ship. A Ming army and navy led by Koxinga

Zheng Chenggong, Prince of Yanping (; 27 August 1624 – 23 June 1662), better known internationally as Koxinga (), was a Ming loyalist general who resisted the Qing conquest of China in the 17th century, fighting them on China's southeastern ...

defeated a western power, the Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock ...

, at the Siege of Fort Zeelandia

The siege of Fort Zeelandia () of 1661–1662 ended the Dutch East India Company's rule over Taiwan and began the Kingdom of Tungning's rule over the island.

Prelude

From 1623 to 1624 the Dutch had been at war with Ming China over the Pescador ...

, the first time China had defeated a western power. The Chinese used cannons and ships to bombard the Dutch into surrendering.

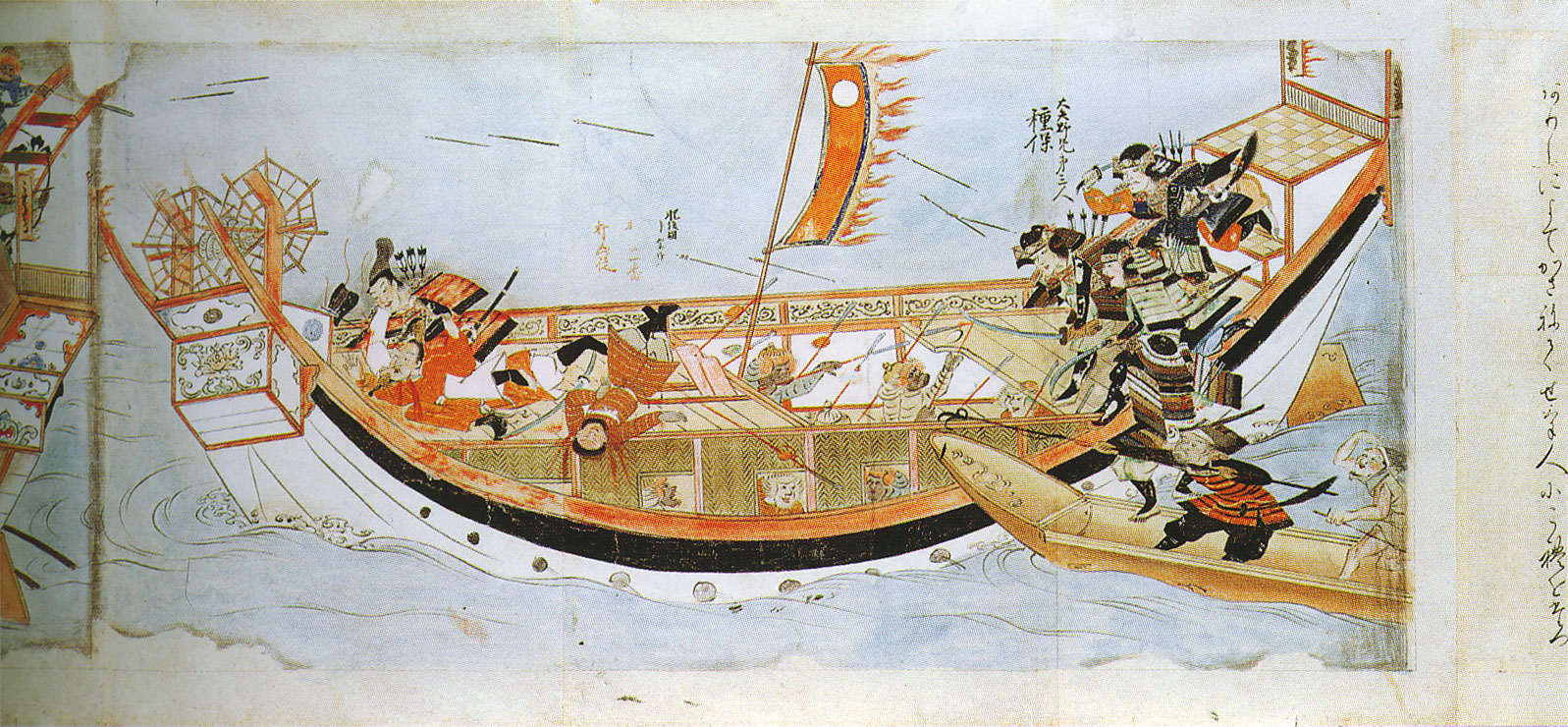

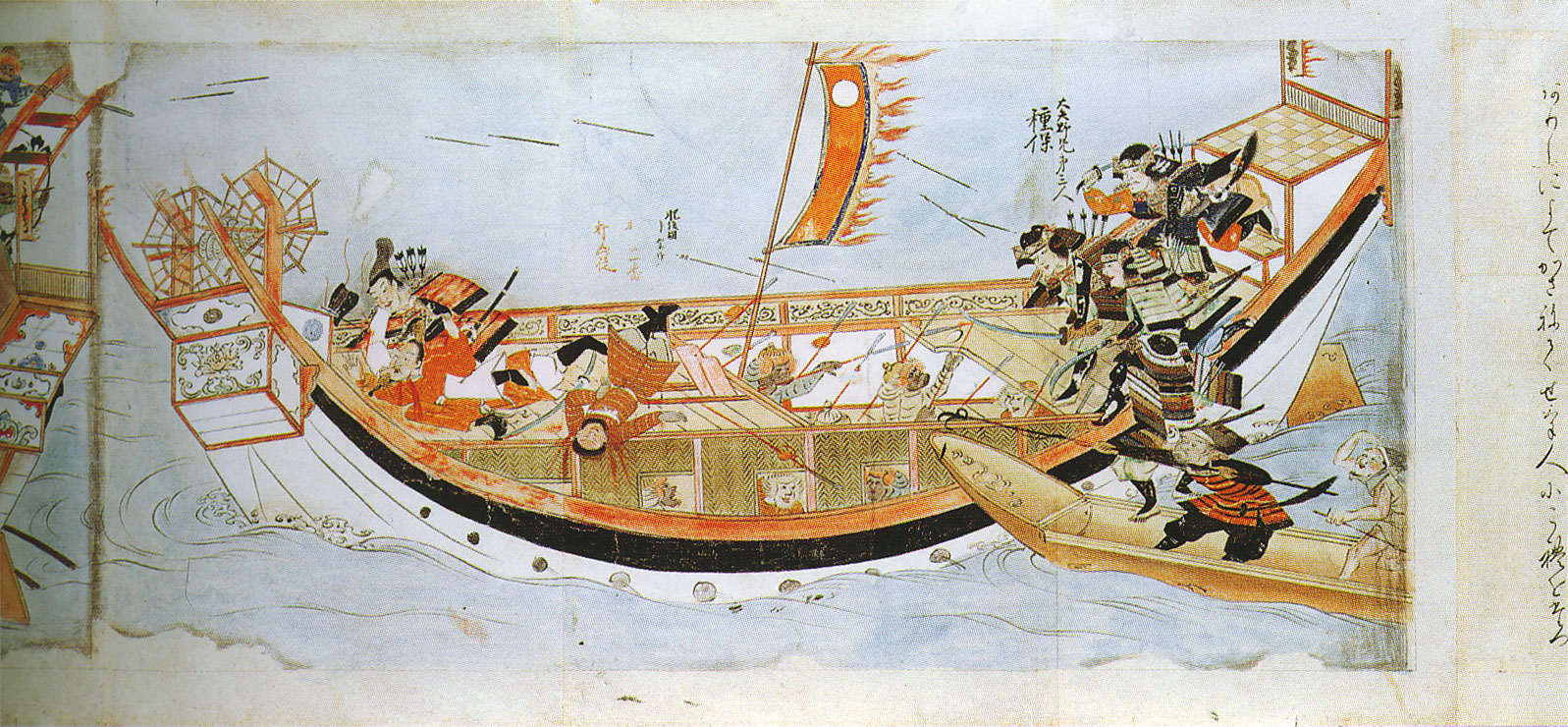

In the Sengoku period

The was a period in History of Japan, Japanese history of near-constant civil war and social upheaval from 1467 to 1615.

The Sengoku period was initiated by the Ōnin War in 1467 which collapsed the Feudalism, feudal system of Japan under the ...

of Japan, Oda Nobunaga unified the country by military power. However, he was defeated by the Mōri clan

The Mōri clan (毛利氏 ''Mōri-shi'') was a Japanese samurai clan descended from Ōe no Hiromoto. Ōe no Hiromoto was descended from the Fujiwara clan. The family's most illustrious member, Mōri Motonari, greatly expanded the clan's pow ...

's navy. Nobunaga invented the Tekkosen (large Atakebune

or were large Japanese warships of the 16th and 17th century used during the internecine Japanese wars for political control and unity of all Japan.

History

Japan undertook major naval building efforts in the mid to late 16th century, during t ...

equipped with iron plates) and defeated 600 ships of the Mōri navy with six armored warships (Battle of Kizugawaguchi The two were fought during Oda Nobunaga, Oda Nobunaga's attempted Siege of Ishiyama Hongan-ji, sieges of the Ishiyama Hongan-ji in Osaka. The Ishiyama Hongan-ji, Hongan-ji was the primary fortress of the Ikkō-ikki, mobs of warrior monks, priests, ...

). The navy of Nobunaga and his successor Toyotomi Hideyoshi

, otherwise known as and , was a Japanese samurai and ''daimyō'' (feudal lord) of the late Sengoku period regarded as the second "Great Unifier" of Japan.Richard Holmes, The World Atlas of Warfare: Military Innovations that Changed the Cour ...

employed clever close-range tactics on land with arquebus

An arquebus ( ) is a form of long gun that appeared in Europe and the Ottoman Empire during the 15th century. An infantryman armed with an arquebus is called an arquebusier.

Although the term ''arquebus'', derived from the Dutch word ''Haakbus ...

rifles, but also relied upon close-range firing of muskets in grapple-and-board style naval engagements. When Nobunaga died in the Honnō-ji incident, Hideyoshi succeeded him and completed the unification of the whole country. In 1592, Hideyoshi ordered the ''daimyō

were powerful Japanese magnates, feudal lords who, from the 10th century to the early Meiji period in the middle 19th century, ruled most of Japan from their vast, hereditary land holdings. They were subordinate to the shogun and nominal ...

s'' to dispatch troops to Joseon Korea to conquer Ming China. The Japanese army which landed at Pusan on 12 April 1502 occupied Seoul within a month. The Korean king escaped to the northern region of the Korean peninsula and Japan completed occupation of Pyongyang

Pyongyang (, , ) is the capital and largest city of North Korea, where it is known as the "Capital of the Revolution". Pyongyang is located on the Taedong River about upstream from its mouth on the Yellow Sea. According to the 2008 populat ...

in June. The Korean navy then led by Admiral Yi Sun-sin defeated the Japanese navy in consecutive naval battles, namely Okpo, Sacheon, Tangpo and Tanghangpo. The Battle of Hansando on 14 August 1592 resulted in a decisive victory for Korea over the Japanese navy. In this battle, 47 Japanese warships were sunk and 12 other ships were captured whilst no Korean warship was lost. The defeats in the sea prevented the Japanese navy from providing their army with appropriate supply.

Yi Sun-sin was later replaced with Admiral Won Gyun

Won Gyun (; 12 February 1540 – 27 August 1597) was a Korean general and admiral during the Joseon Dynasty. He is best known for his campaigns against the Japanese during Hideyoshi's invasions of Korea. Won was a member of Wonju Won family, ...

, whose fleets faced a defeat. The Japanese army, based near Busan

Busan (), officially known as is South Korea's most populous city after Seoul, with a population of over 3.4 million inhabitants. Formerly romanized as Pusan, it is the economic, cultural and educational center of southeastern South Korea, ...

, overwhelmed the Korean navy in the Battle of Chilcheollyang

The naval Battle of Chilcheollyang took place on the night of 28 August 1597. It resulted in the destruction of nearly the entire Korean fleet.

Background

Prior to the battle, the previous naval commander Yi Sun-sin, had been removed from his ...

on 28 August 1597 and began advancing toward China. This attempt was stopped when the reappointed Admiral Yi, won the battle of Myeongnyang

In the Battle of Myeongnyang, on October 26, 1597, the Korean Joseon Kingdom's navy, led by Admiral Yi Sun-sin, fought the Japanese navy in the Myeongnyang Strait, near Jindo Island, off the southwest corner of the Korean peninsula.

Wit ...

.

The Wanli Emperor

The Wanli Emperor (; 4 September 1563 – 18 August 1620), personal name Zhu Yijun (), was the 14th Emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigned from 1572 to 1620. "Wanli", the era name of his reign, literally means "ten thousand calendars". He was th ...

of Ming China sent military forces to the Korean peninsula. Yi Sun-sin and Chen Lin continued to successfully engage the Japanese navy with 500 Chinese warships and the strengthened Korean fleet. In 1598, the planned conquest in China was canceled by the death of Toyotomi Hideyoshi

, otherwise known as and , was a Japanese samurai and ''daimyō'' (feudal lord) of the late Sengoku period regarded as the second "Great Unifier" of Japan.Richard Holmes, The World Atlas of Warfare: Military Innovations that Changed the Cour ...

, and the Japanese military retreated from the Korean Peninsula. On their way back to Japan, Yi Sun-sin and Chen Lin attacked the Japanese navy at the Battle of Noryang inflicting heavy damages, but the Chinese top official Deng Zilong

Vice-Admiral, Deng Zilong (鄧子龍 in traditional Chinese, 1531–1598) was a military commander for the Ming dynasty China. His courtesy name was "Wuqiao" (武橋) and his nickname was the "Tiger Crown Taoist" (虎冠道士). He was born in the ...

and the Korean commander Yi Sun-sin

Admiral Yi Sun-sin (April 28, 1545 – December 16, 1598) was a Korean admiral and military general famed for his victories against the Japanese navy during the Imjin war in the Joseon Dynasty. Over the course of his career, Admiral Yi foug ...

were killed in a Japanese army counterattack. The rest of the Japanese army returned to Japan by the end of December. In 1609, the Tokugawa shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate (, Japanese 徳川幕府 ''Tokugawa bakufu''), also known as the , was the military government of Japan during the Edo period from 1603 to 1868. Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005)"''Tokugawa-jidai''"in ''Japan Encyclopedia ...

ordered the abandonment of warships to the feudal lord

An overlord in the English feudal system was a lord of a manor who had subinfeudated a particular manor, estate or fee, to a tenant. The tenant thenceforth owed to the overlord one of a variety of services, usually military service or se ...

. The Japanese navy stagnated until the Meiji period

The is an era of Japanese history that extended from October 23, 1868 to July 30, 1912.

The Meiji era was the first half of the Empire of Japan, when the Japanese people moved from being an isolated feudal society at risk of colonization ...

.

In Korea, the greater range of

In Korea, the greater range of Korean cannon

Cannons appeared in Korea by the mid 14th century during the Goryeo dynasty and quickly proliferated as naval and fortress-defense weapons. Major developments occurred throughout the 15th century, including the introduction of large siege mortars a ...

s, along with the brilliant naval strategies of the Korean admiral Yi Sun-sin

Admiral Yi Sun-sin (April 28, 1545 – December 16, 1598) was a Korean admiral and military general famed for his victories against the Japanese navy during the Imjin war in the Joseon Dynasty. Over the course of his career, Admiral Yi foug ...

, were the main factors in the ultimate Japanese defeat. Yi Sun-sin is credited for improving the Geobukseon (turtle ship), which were used mostly to spearhead attacks. They were best used in tight areas and around islands rather than on the open sea. Yi Sun-sin effectively cut off the possible Japanese supply line that would have run through the Yellow Sea

The Yellow Sea is a marginal sea of the Western Pacific Ocean located between mainland China and the Korean Peninsula, and can be considered the northwestern part of the East China Sea. It is one of four seas named after common colour ter ...

to China, and severely weakened the Japanese strength and fighting morale in several heated engagements (many regard the critical Japanese defeat to be the Battle of Hansan Island

The Battle of Hansan Island and following engagement at Angolpo took place from 8 July 1592. In two naval encounters, Korean Admiral Yi Sun-sin's fleet managed to destroy roughly 100 Japanese ships and halted Japanese naval operations along th ...

). The Japanese faced diminishing hopes of further supplies due to repeated losses in naval battles in the hands of Yi Sun-sin. As the Japanese army was about to return to Japan, Yi Sun-sin decisively defeated a Japanese navy at the Battle of Noryang.

Ancient and Medieval China

Warring States period

The Warring States period () was an era in ancient Chinese history characterized by warfare, as well as bureaucratic and military reforms and consolidation. It followed the Spring and Autumn period and concluded with the Qin wars of conquest ...

(481–221 BC) when vassal

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerain ...

lords battled one another. Chinese naval warfare in this period featured grapple-and-hook, as well as ramming tactics with ships called "stomach strikers" and "colliding swoopers".Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, p. 678 It was written in the Han dynasty

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–207 BC) and a warr ...

that the people of the Warring States era had employed ''chuan ge'' ships (dagger-axe ships, or halberd