Scythian Sculptures From The Tovsta Mohyla Kurhan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Central Asia and Eastern Turkestan to distinguish them from the related Massagetae of the Aral region and the Scythians of the Pontic steppes. These tribes spoke Iranian languages, and their chief occupation was nomadic pastoralism."

* : "Near the end of the 19th century V.F. Miller (1886, 1887) theorized that the Scythians and their kindred, the Sauromatians, were Iranian-speaking peoples. This has been a popular point of view and continues to be accepted in linguistics and historical science ..

* : "From the end of the 7th century B.C. to the 4th century B.C. the Central- Eurasian steppes were inhabited by two large groups of kin Iranian-speaking tribes – the Scythians and Sarmatians ..

* : "All contemporary historians, archeologists and linguists are agreed that since the Scythian and Sarmatian tribes were of the Iranian linguistic group ..

* : "During the first half of the first millennium B.C., c. 3,000 to 2,500 years ago, the southern part of Eastern Europe was occupied mainly by peoples of Iranian stock ..The main Iranian-speaking peoples of the region at that period were the Scyths and the Sarmatians ..

* : "When we speak of Scythians, we refer to those Scytho-Siberians who inhabited the Kuban Valley, the Taman and Kerch peninsulas, Crimea, the northern and northeastern littoral of the Black Sea, and the steppe and lower forest steppe regions now shared between Ukraine and Russia, from the seventh century down to the first century B.C ..They almost certainly spoke an Iranian language ..

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Central Asia and Eastern Turkestan to distinguish them from the related Massagetae of the Aral region and the Scythians of the Pontic steppes. These tribes spoke Iranian languages, and their chief occupation was nomadic pastoralism."

* : "Near the end of the 19th century V.F. Miller (1886, 1887) theorized that the Scythians and their kindred, the Sauromatians, were Iranian-speaking peoples. This has been a popular point of view and continues to be accepted in linguistics and historical science ..

* : "From the end of the 7th century B.C. to the 4th century B.C. the Central- Eurasian steppes were inhabited by two large groups of kin Iranian-speaking tribes – the Scythians and Sarmatians ..

* : "All contemporary historians, archeologists and linguists are agreed that since the Scythian and Sarmatian tribes were of the Iranian linguistic group ..

* : "During the first half of the first millennium B.C., c. 3,000 to 2,500 years ago, the southern part of Eastern Europe was occupied mainly by peoples of Iranian stock ..The main Iranian-speaking peoples of the region at that period were the Scyths and the Sarmatians ..

* : "When we speak of Scythians, we refer to those Scytho-Siberians who inhabited the Kuban Valley, the Taman and Kerch peninsulas, Crimea, the northern and northeastern littoral of the Black Sea, and the steppe and lower forest steppe regions now shared between Ukraine and Russia, from the seventh century down to the first century B.C ..They almost certainly spoke an Iranian language ..

The Scythians were part of the wider

The Scythians were part of the wider

The Scythians originated in the region of the Volga-Ural steppes of

The Scythians originated in the region of the Volga-Ural steppes of

During the earliest phase of their presence in West Asia, the Scythians under their king

During the earliest phase of their presence in West Asia, the Scythians under their king

After their expulsion from West Asia, and beginning in the later 7th and lasting throughout much of the 6th century BC, the majority of the Scythians, including the Royal Scythians, migrated into the Kuban Steppe around 600 BC, and from Ciscaucasia into the Pontic Steppe, which became the centre of Scythian power, and in the western Ciscaucasia, from where the Scythians, not large in number enough to spread throughout Ciscaucasia, instead took over the steppe to the south of the Kuban river's middle course; the northwards migration of the Scythians continued throughout the 6th century BC. Using the Pontic Steppe as their base, the Scythians often raided into the adjacent regions, with Central Europe being a frequent target of their raids. In many parts of their north Pontic kingdom, the Scythians established themselves as a ruling class over already present sedentary populations, including

After their expulsion from West Asia, and beginning in the later 7th and lasting throughout much of the 6th century BC, the majority of the Scythians, including the Royal Scythians, migrated into the Kuban Steppe around 600 BC, and from Ciscaucasia into the Pontic Steppe, which became the centre of Scythian power, and in the western Ciscaucasia, from where the Scythians, not large in number enough to spread throughout Ciscaucasia, instead took over the steppe to the south of the Kuban river's middle course; the northwards migration of the Scythians continued throughout the 6th century BC. Using the Pontic Steppe as their base, the Scythians often raided into the adjacent regions, with Central Europe being a frequent target of their raids. In many parts of their north Pontic kingdom, the Scythians established themselves as a ruling class over already present sedentary populations, including

By 50 to 150 AD, most of the Scythians had been assimilated by the Sarmatians. The remaining Scythians of Crimea, who had mixed with the

By 50 to 150 AD, most of the Scythians had been assimilated by the Sarmatians. The remaining Scythians of Crimea, who had mixed with the

The Scythians were a warlike people. When engaged at war, almost the entire adult population, including a large number of women, participated in battle. The Athenian historian

The Scythians were a warlike people. When engaged at war, almost the entire adult population, including a large number of women, participated in battle. The Athenian historian

The art of the Scythians and related peoples of the Scythian cultures is known as Scythian art. It is particularly characterized by its use of the

The art of the Scythians and related peoples of the Scythian cultures is known as Scythian art. It is particularly characterized by its use of the

In ''

In ''

20

"The Scythians are a ruddy race because of the cold, not through any fierceness in the sun's heat. It is the cold that burns their white skin and turns it ruddy." as well as having a particularly high rate of hypermobility, to a point of affecting warfare. In the 3rd century BC, the Greek poet

Hymn IV. To Delos. 291

"The first to bring thee these offerings fro the fair-haired Arimaspi .. The 2nd-century BC

Book VI, Chap. 24

". These people, they said, exceeded the ordinary human height, had flaxen hair, and blue eyes .. In the late 2nd century AD, the Christian theologian

Scythian archaeology can be divided into three stages:

* Early Scythian – from the mid-8th or the late 7th century BC to about 500 BC

* Classical Scythian or Mid-Scythian – from about 500 BC to about 300 BC

* Late Scythian – from about 200 BC to the mid-3rd century AD, in the

Scythian archaeology can be divided into three stages:

* Early Scythian – from the mid-8th or the late 7th century BC to about 500 BC

* Classical Scythian or Mid-Scythian – from about 500 BC to about 300 BC

* Late Scythian – from about 200 BC to the mid-3rd century AD, in the

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Central Asia and Eastern Turkestan to distinguish them from the related Massagetae of the Aral region and the Scythians of the Pontic steppes. These tribes spoke Iranian languages, and their chief occupation was nomadic pastoralism."

* : "Near the end of the 19th century V.F. Miller (1886, 1887) theorized that the Scythians and their kindred, the Sauromatians, were Iranian-speaking peoples. This has been a popular point of view and continues to be accepted in linguistics and historical science ..

* : "From the end of the 7th century B.C. to the 4th century B.C. the Central- Eurasian steppes were inhabited by two large groups of kin Iranian-speaking tribes – the Scythians and Sarmatians ..

* : "All contemporary historians, archeologists and linguists are agreed that since the Scythian and Sarmatian tribes were of the Iranian linguistic group ..

* : "During the first half of the first millennium B.C., c. 3,000 to 2,500 years ago, the southern part of Eastern Europe was occupied mainly by peoples of Iranian stock ..The main Iranian-speaking peoples of the region at that period were the Scyths and the Sarmatians ..

* : "When we speak of Scythians, we refer to those Scytho-Siberians who inhabited the Kuban Valley, the Taman and Kerch peninsulas, Crimea, the northern and northeastern littoral of the Black Sea, and the steppe and lower forest steppe regions now shared between Ukraine and Russia, from the seventh century down to the first century B.C ..They almost certainly spoke an Iranian language ..

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Central Asia and Eastern Turkestan to distinguish them from the related Massagetae of the Aral region and the Scythians of the Pontic steppes. These tribes spoke Iranian languages, and their chief occupation was nomadic pastoralism."

* : "Near the end of the 19th century V.F. Miller (1886, 1887) theorized that the Scythians and their kindred, the Sauromatians, were Iranian-speaking peoples. This has been a popular point of view and continues to be accepted in linguistics and historical science ..

* : "From the end of the 7th century B.C. to the 4th century B.C. the Central- Eurasian steppes were inhabited by two large groups of kin Iranian-speaking tribes – the Scythians and Sarmatians ..

* : "All contemporary historians, archeologists and linguists are agreed that since the Scythian and Sarmatian tribes were of the Iranian linguistic group ..

* : "During the first half of the first millennium B.C., c. 3,000 to 2,500 years ago, the southern part of Eastern Europe was occupied mainly by peoples of Iranian stock ..The main Iranian-speaking peoples of the region at that period were the Scyths and the Sarmatians ..

* : "When we speak of Scythians, we refer to those Scytho-Siberians who inhabited the Kuban Valley, the Taman and Kerch peninsulas, Crimea, the northern and northeastern littoral of the Black Sea, and the steppe and lower forest steppe regions now shared between Ukraine and Russia, from the seventh century down to the first century B.C ..They almost certainly spoke an Iranian language .. Iranian

Iranian may refer to:

* Iran, a sovereign state

* Iranian peoples, the speakers of the Iranian languages. The term Iranic peoples is also used for this term to distinguish the pan ethnic term from Iranian, used for the people of Iran

* Iranian lan ...

* : "Scythians, a nomadic people of Iranian origin ..

* : " th Cimmerians and Scythians were Iranian peoples."

* : "During the first half of the first millennium B.C., c. 3,000 to 2,500 years ago, the southern part of Eastern Europe was occupied mainly by peoples of Iranian stock .. e population of ancient Scythia was far from being homogeneous, nor were the Scyths themselves a homogeneous people. The country called after them was ruled by their principal tribe, the "Royal Scyths" (Her. iv. 20), who were of Iranian stock and called themselves "Skolotoi" ..

* : " ue Scyths seems to be those whom erodotuscalls Royal Scyths, that is, the group who claimed hegemony ..apparently warrior-pastoralists. It is generally agreed, from what we know of their names, that these were people of Iranian stock ..

* : "The physical characteristics of the Scythians correspond to their cultural affiliation: their origins place them within the group of Iranian peoples."

* : "The Scythian kingdom ..was succeeded in the Russian steppes by an ascendancy of various Sarmatian tribes — Iranians, like the Scythians themselves."

* : "The general view is that both agricultural and nomad Scythians were Iranian." equestrian

The word equestrian is a reference to equestrianism, or horseback riding, derived from Latin ' and ', "horse".

Horseback riding (or Riding in British English)

Examples of this are:

*Equestrian sports

*Equestrian order, one of the upper classes in ...

nomad

A nomad is a member of a community without fixed habitation who regularly moves to and from the same areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the popu ...

ic people who had migrated from Central Asia to the Pontic Steppe

Pontic, from the Greek ''pontos'' (, ), or "sea", may refer to:

The Black Sea Places

* The Pontic colonies, on its northern shores

* Pontus (region), a region on its southern shores

* The Pontic–Caspian steppe, steppelands stretching from nor ...

in modern-day Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

and Southern Russia

Southern Russia or the South of Russia (russian: Юг России, ''Yug Rossii'') is a colloquial term for the southernmost geographic portion of European Russia generally covering the Southern Federal District and the North Caucasian Federal ...

from approximately the 7th century BC until the 3rd century BC.

Skilled in mounted warfare, the Scythians replaced the Cimmerians as the dominant power on the Pontic Steppe in the 8th century BC. In the 7th century BC, the Scythians crossed the Caucasus Mountains

The Caucasus Mountains,

: pronounced

* hy, Կովկասյան լեռներ,

: pronounced

* az, Qafqaz dağları, pronounced

* rus, Кавка́зские го́ры, Kavkázskiye góry, kɐfˈkasːkʲɪje ˈɡorɨ

* tr, Kafkas Dağla ...

and frequently raided West Asia

Western Asia, West Asia, or Southwest Asia, is the westernmost subregion of the larger geographical region of Asia, as defined by some academics, UN bodies and other institutions. It is almost entirely a part of the Middle East, and includes Ana ...

along with the Cimmerians. After being expelled from West Asia by the Medes

The Medes (Old Persian: ; Akkadian: , ; Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ) were an ancient Iranian people who spoke the Median language and who inhabited an area known as Media between western and northern Iran. Around the 11th century BC, the ...

, the Scythians retreated back into the Pontic Steppe and were gradually conquered by the Sarmatians. In the late 2nd century BC, the capital of the largely Hellenized

Hellenization (other British spelling Hellenisation) or Hellenism is the adoption of Greek culture, religion, language and identity by non-Greeks. In the ancient period, colonization often led to the Hellenization of indigenous peoples; in the ...

Scythians at Scythian Neapolis in the Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a pop ...

was captured by Mithridates VI and their territories incorporated into the Bosporan Kingdom

The Bosporan Kingdom, also known as the Kingdom of the Cimmerian Bosporus (, ''Vasíleio toú Kimmerikoú Vospórou''), was an ancient Greco-Scythian state located in eastern Crimea and the Taman Peninsula on the shores of the Cimmerian Bosporus, ...

. By the 3rd century AD, the Sarmatians and last remnants of the Scythians were overwhelmed by the Goths

The Goths ( got, 𐌲𐌿𐍄𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰, translit=''Gutþiuda''; la, Gothi, grc-gre, Γότθοι, Gótthoi) were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Europe ...

, and by the early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

, the Scythians and the Sarmatians had been largely assimilated and absorbed by early Slavs

The early Slavs were a diverse group of tribal societies who lived during the Migration Period and the Early Middle Ages (approximately the 5th to the 10th centuries AD) in Central and Eastern Europe and established the foundations for the S ...

.: "Indeed, it is now accepted that the Sarmatians merged in with pre-Slavic populations.": "In their Ukrainian and Polish homeland the Slavs were intermixed and at times overlain by Germanic speakers (the Goths) and by Iranian speakers (Scythians, Sarmatians, Alans) in a shifting array of tribal and national configurations." The Scythians were instrumental in the ethnogenesis

Ethnogenesis (; ) is "the formation and development of an ethnic group".

This can originate by group self-identification or by outside identification.

The term ''ethnogenesis'' was originally a mid-19th century neologism that was later introdu ...

of the Ossetians

The Ossetians or Ossetes (, ; os, ир, ирæттæ / дигорӕ, дигорӕнттӕ, translit= ir, irættæ / digoræ, digorænttæ, label=Ossetic) are an Iranian ethnic group who are indigenous to Ossetia, a region situated across the no ...

, who are believed to be descended from the Alans.

After the Scythians' disappearance, authors of the ancient, mediaeval, and early modern periods used the name "Scythian" to refer to various populations of the steppes unrelated to them.

The Scythians played an important part in the Silk Road

The Silk Road () was a network of Eurasian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over 6,400 kilometers (4,000 miles), it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and reli ...

, a vast trade network connecting Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

, Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

and China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, perhaps contributing to the prosperity of those civilisations. Settled metalworkers made portable decorative objects for the Scythians, forming a history of Scythian metalworking. These objects survive mainly in metal, forming a distinctive Scythian art.

Names

Etymology

The English name or is derived from theAncient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

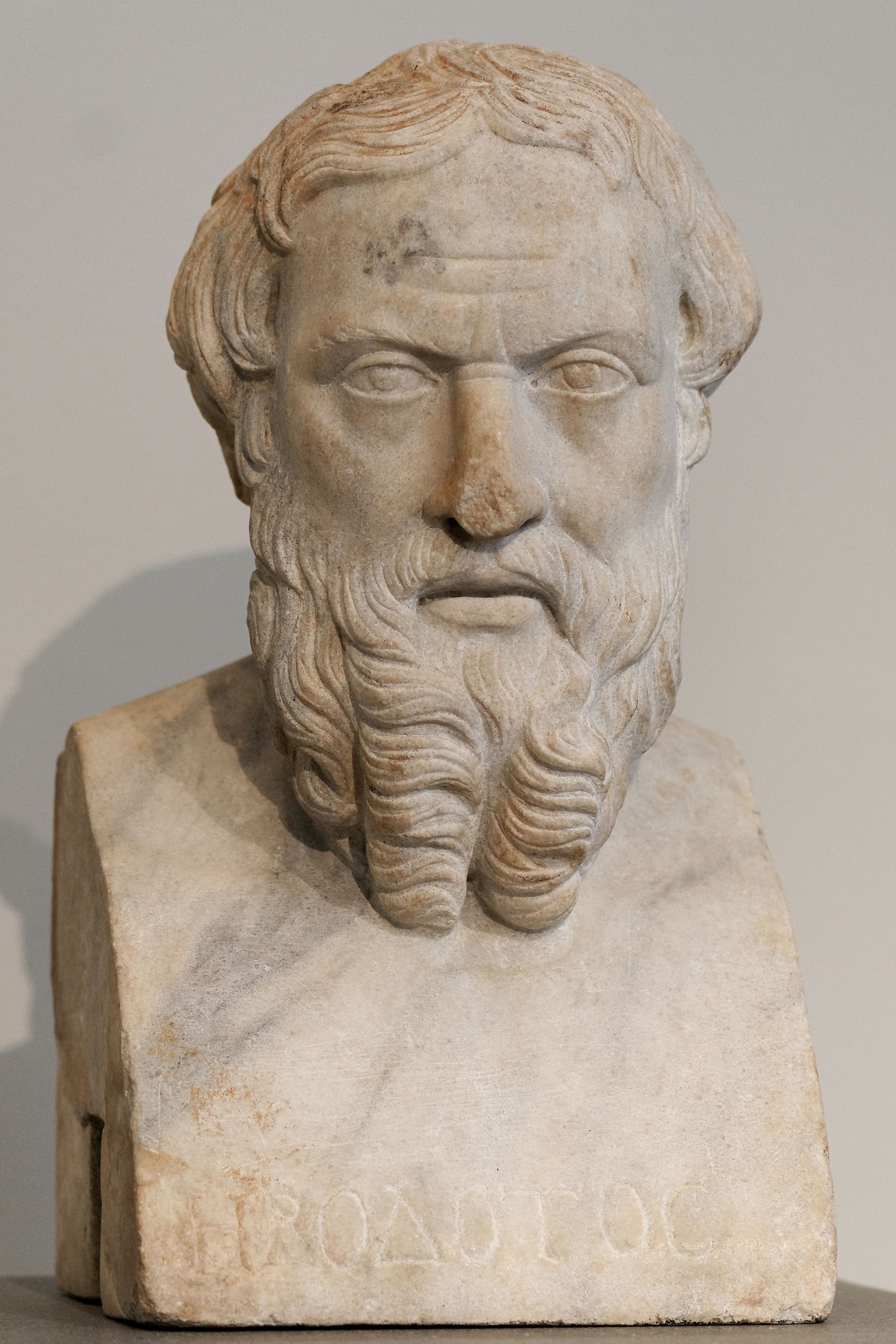

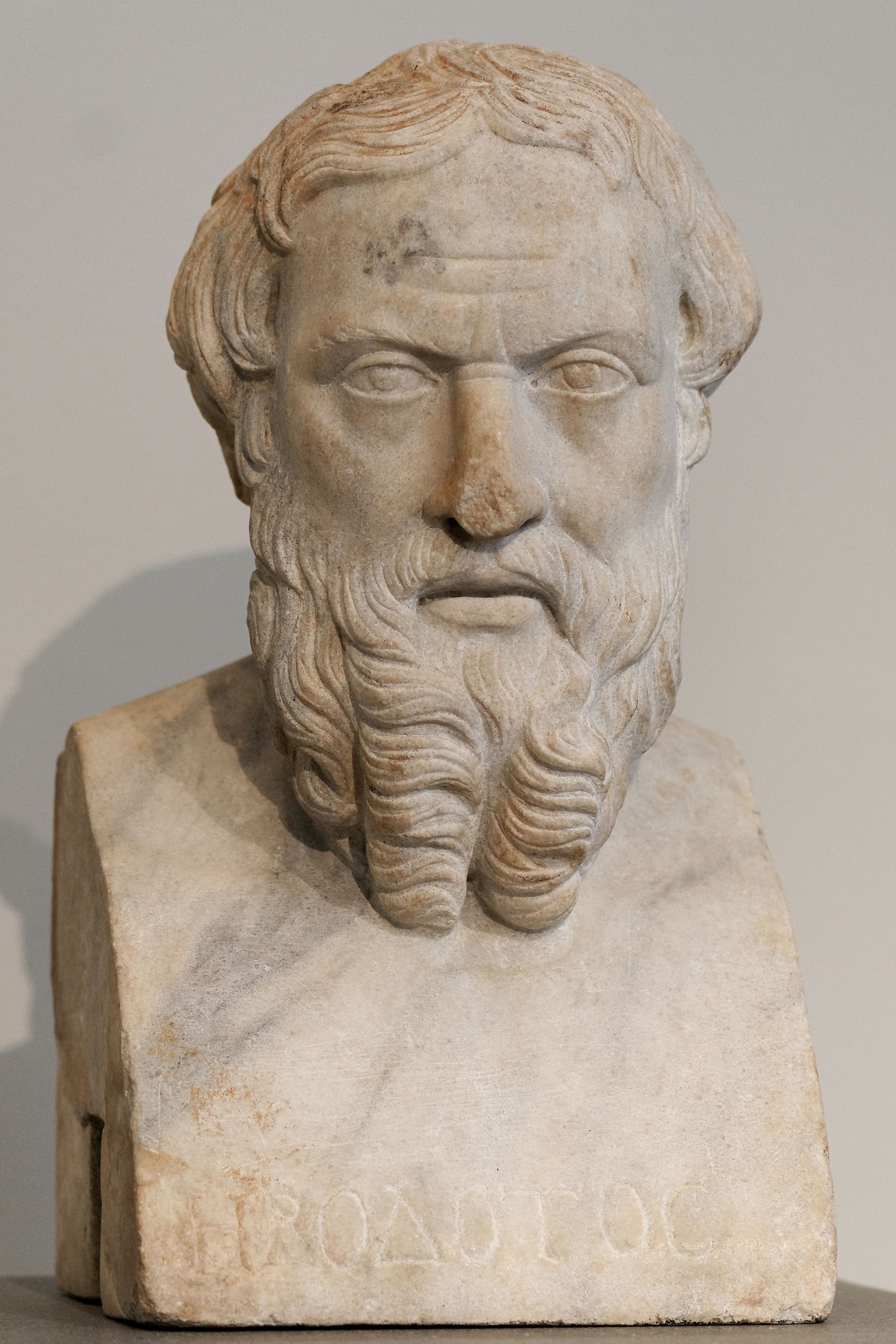

name () and (), derived from the Scythian endonym , which, due to a sound change from /δ/ to /l/ in the Scythian, evolved into the form . This designation was recorded in Greek as (), which, according to Herodotus of Halicarnassus, was the self-designation of the tribe of the Royal Scythians.

The Assyrians

Assyrian may refer to:

* Assyrian people, the indigenous ethnic group of Mesopotamia.

* Assyria, a major Mesopotamian kingdom and empire.

** Early Assyrian Period

** Old Assyrian Period

** Middle Assyrian Empire

** Neo-Assyrian Empire

* Assyrian ...

rendered the name of the Scythians as (Akkadian Akkadian or Accadian may refer to:

* Akkadians, inhabitants of the Akkadian Empire

* Akkadian language, an extinct Eastern Semitic language

* Akkadian literature, literature in this language

* Akkadian cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo- syllabi ...

: , romanized: ) or (Akkadian Akkadian or Accadian may refer to:

* Akkadians, inhabitants of the Akkadian Empire

* Akkadian language, an extinct Eastern Semitic language

* Akkadian literature, literature in this language

* Akkadian cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo- syllabi ...

: , romanized: , , romanized: , , romanized: ).

The ancient Persians meanwhile called the Scythians " who live beyond the Sea

The sea, connected as the world ocean or simply the ocean, is the body of salty water that covers approximately 71% of the Earth's surface. The word sea is also used to denote second-order sections of the sea, such as the Mediterranean Sea, ...

" (, romanized: ) in Old Persian

Old Persian is one of the two directly attested Old Iranian languages (the other being Avestan language, Avestan) and is the ancestor of Middle Persian (the language of Sasanian Empire). Like other Old Iranian languages, it was known to its native ...

and simply (, romanized: ; , romanized: ) in Ancient Egyptian, from which was derived the Graeco-Roman name ( grc, Σακαι, Sakai; Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

: ).

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Central Asia and Eastern Turkestan to distinguish them from the related Massagetae of the Aral region and the Scythians of the Pontic steppes. These tribes spoke Iranian languages, and their chief occupation was nomadic pastoralism."

* : "The Scythians lived in the Early Iron Age, and inhabited the northern areas of the Black Sea (Pontic) steppes. Though the 'Scythian period' in the history of Eastern Europe lasted little more than 400 years, from the 7th to the 3rd centuries BC, the impression these horsemen made upon the history of their times was such that a thousand years after they had ceased to exist as a sovereign people, their heartland and the territories which they dominated far beyond it continued to be known as 'greater Scythia'."

* : "From the end of the 7th century B.C. to the 4th century B.C. the Central- Eurasian steppes were inhabited by two large groups of kin Iranian-speaking tribes – the Scythians and Sarmatians .." may be confidently stated that from the end of the 7th century to the 3rd century B.C. the Scythians occupied the steppe expanses of the north Black Sea area, from the Don in the east to the Danube in the West."

* : "Scythians, a nomadic people of Iranian origin who flourished in the steppe lands north of the Black Sea during the 7th–4th centuries BC (Figure 1). For related groups in Central Asia and India, see ..

* : "During the first half of the first millennium B.C., c. 3,000 to 2,500 years ago, the southern part of Eastern Europe was occupied mainly by peoples of Iranian stock ..The main Iranian-speaking peoples of the region at that period were the Scyths and the Sarmatians .. e population of ancient Scythia was far from being homogeneous, nor were the Scyths themselves a homogeneous people. The country called after them was ruled by their principal tribe, the "Royal Scyths" (Her. iv. 20), who were of Iranian stock and called themselves "Skolotoi" (iv. 6); they were nomads who lived in the steppe east of the Dnieper up to the Don, and in the Crimean steppe ..The eastern neighbours of the "Royal Scyths," the Sauromatians, were also Iranian; their country extended over the steppe east of the Don and the Volga."

* : "The name 'Scythian' is met in the classical authors and has been taken to refer to an ethnic group or people, also mentioned in Near Eastern texts, who inhabited the northern Black Sea region."

* : "Ordinary Greek (and later Latin) usage could designate as Scythian any northern barbarian from the general area of the Eurasian steppe, the virtually treeless corridor of drought-resistant perennial grassland extending from the Danube to Manchuria. Herodotus seeks greater precision, and this essay is focussed on his Scythians, who belong to the North Pontic steppe ..These true Scyths seems to be those whom he calls Royal Scyths, that is, the group who claimed hegemony ..apparently warrior-pastoralists. It is generally agreed, from what we know of their names, that these were people of Iranian stock ..

* : "When we speak of Scythians, we refer to those Scytho-Siberians who inhabited the Kuban Valley, the Taman and Kerch peninsulas, Crimea, the northern and northeastern littoral of the Black Sea, and the steppe and lower forest steppe regions now shared between Ukraine and Russia, from the seventh century down to the first century B.C ..They almost certainly spoke an Iranian language ..

* : "The first historical steppe nomads, the Scythians, inhabited the steppe north of the Black Sea from about the eight century B.C."

*

Modern terminology

The Scythians were part of the wider

The Scythians were part of the wider Scytho-Siberian world

The Scytho-Siberian world was an archaeological horizon which flourished across the entire Eurasian Steppe during the Iron Age from approximately the 9th century BC to the 2nd century AD. It included the Scythian, Sauromatian ...

, stretching across the Eurasian Steppe

The Eurasian Steppe, also simply called the Great Steppe or the steppes, is the vast steppe ecoregion of Eurasia in the temperate grasslands, savannas and shrublands biome. It stretches through Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania, Moldova and Transnistri ...

s of Kazakhstan, the Russian steppes of the Siberian, Ural, Volga and Southern regions, and eastern Ukraine. In a broader sense, Scythians has also been used to designate all early Eurasian nomads, although the validity of such terminology is controversial, and other terms such as "Early nomadic" have been deemed preferable.

Although the Scythians, Saka and Cimmerians were closely related nomadic Iranian

Iranian may refer to:

* Iran, a sovereign state

* Iranian peoples, the speakers of the Iranian languages. The term Iranic peoples is also used for this term to distinguish the pan ethnic term from Iranian, used for the people of Iran

* Iranian lan ...

peoples, and the ancient Babylonians, ancient Persians and ancient Greeks respectively used the names " Cimmerian," "Saka," and "Scythian" for all the steppe nomads, and early modern historians such as Edward Gibbon

Edward Gibbon (; 8 May 173716 January 1794) was an English historian, writer, and member of parliament. His most important work, ''The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire'', published in six volumes between 1776 and 1788, is k ...

used the term Scythian to refer to a variety of nomadic and semi-nomadic peoples across the Eurasian Steppe, the name "Scythian" in contemporary modern scholarship generally refers to the nomadic Iranian people

Iranians or Iranian people may refer to:

* Iranian peoples, Indo-European ethno-linguistic group living predominantly in Iran and other parts of the Middle East and the Caucasus, as well as parts of Central Asia and South Asia

** Persians, Irania ...

who dominated the Pontic Steppe

Pontic, from the Greek ''pontos'' (, ), or "sea", may refer to:

The Black Sea Places

* The Pontic colonies, on its northern shores

* Pontus (region), a region on its southern shores

* The Pontic–Caspian steppe, steppelands stretching from nor ...

from the 7th century BC to the 3rd century BC, while the name "Saka

The Saka ( Old Persian: ; Kharoṣṭhī: ; Ancient Egyptian: , ; , old , mod. , ), Shaka (Sanskrit ( Brāhmī): , , ; Sanskrit (Devanāgarī): , ), or Sacae (Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ) were a group of nomadic Iranian peoples who hist ...

" is used specifically for their eastern members who inhabited the northern and eastern Eurasian Steppe

The Eurasian Steppe, also simply called the Great Steppe or the steppes, is the vast steppe ecoregion of Eurasia in the temperate grasslands, savannas and shrublands biome. It stretches through Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania, Moldova and Transnistri ...

and the Tarim Basin

The Tarim Basin is an endorheic basin in Northwest China occupying an area of about and one of the largest basins in Northwest China.Chen, Yaning, et al. "Regional climate change and its effects on river runoff in the Tarim Basin, China." Hydr ...

; and while the Cimmerians were often described by contemporaries as culturally Scythian, they formed a different tribe from the Scythians proper, to whom the Cimmerians were related, and who also displaced and replaced the Cimmerians in the Pontic Steppe.

The Scythians share several cultural similarities with other populations living to their east, in particular similar weapons, horse gear and Scythian art, which has been referred to as the ''Scythian triad''.: "Even though there were fundamental ways in which nomadic groups over such a vast territory differed, the terms "Scythian" and "Scythic" have been widely adopted to describe a special phase that followed the widespread diffusion of mounted nomadism, characterized by the presence of special weapons, horse gear, and animal art in the form of metal plaques. Archaeologists have used the term "Scythic continuum" in a broad cultural sense to indicate the early nomadic cultures of the Eurasian Steppe. The term "Scythic" draws attention to the fact that there are elements – shapes of weapons, vessels, and ornaments, as well as lifestyle – common to both the eastern and western ends of the Eurasian Steppe region. However, the extension and variety of sites across Asia makes Scythian and Scythic terms too broad to be viable, and the more neutral "early nomadic" is preferable, since the cultures of the Northern Zone cannot be directly associated with either the historical Scythians or any specific archaeological culture defined as Saka or Scytho-Siberian." Cultures sharing these characteristics have often been referred to as Scythian cultures, and its peoples called ''Scythians''. Peoples associated with Scythian cultures include not only the Scythians themselves, who were a distinct ethnic group,: "Horse-riding nomadism has been referred to as the culture of 'Early Nomads'. This term encompasses different ethnic groups (such as Scythians, Saka, Massagetae, and Yuezhi) .. but also Cimmerians, Massagetae, Saka

The Saka ( Old Persian: ; Kharoṣṭhī: ; Ancient Egyptian: , ; , old , mod. , ), Shaka (Sanskrit ( Brāhmī): , , ; Sanskrit (Devanāgarī): , ), or Sacae (Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ) were a group of nomadic Iranian peoples who hist ...

, Sarmatians and various obscure peoples of the East European Forest Steppe, such as early Slavs

The early Slavs were a diverse group of tribal societies who lived during the Migration Period and the Early Middle Ages (approximately the 5th to the 10th centuries AD) in Central and Eastern Europe and established the foundations for the S ...

, Balts and Finnic peoples. Within this broad definition of the term ''Scythian'', the actual Scythians have often been distinguished from other groups through the terms ''Classical Scythians'', ''Western Scythians'', ''European Scythians'' or ''Pontic Scythians''.

Scythologist Askold Ivantchik

Askold Igorevich Ivantchik (russian: Аско́льд И́горевич Ива́нчик; born 2 May 1965) is a Russian historian. Receiving his Ph.D. in history in 1996, Ivantchik was made a Corresponding Member of the Russian Academy of Sciences ...

notes with dismay that the term "Scythian" has been used within both a broad and a narrow context, leading to a good deal of confusion. He reserves the term "Scythian" for the Iranian people dominating the Pontic Steppe from the 7th century BC to the 3rd century BC. Nicola Di Cosmo

Nicola Di Cosmo (; born 1957, Bari, Apulia, Italy) is the Luce Foundation Professor in East Asian Studies at the Institute for Advanced Study. His main field of research is the history of the relations between China and Inner Asia from prehistory ...

writes that the broad concept of "Scythian" to describe the early nomadic populations of the Eurasian Steppe is "too broad to be viable," and that the term "early nomadic" is preferable.

History

Early history

The Scythians originated in the region of the Volga-Ural steppes of

The Scythians originated in the region of the Volga-Ural steppes of Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a subregion, region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes t ...

, possibly around the 9th century BC, as a section of the population of the Srubnaya culture, to which the Scythians themselves belonged, and continuity between the Scythians and the Srubnaya culture is suggested by both archaeological, genetic and anthropological evidence.

During the 9th to 8th centuries BC, some Scythian tribes had migrated westwards into the steppe adjacent to the northern shore of the Black Sea, which they occupied along with the Cimmerians, who were also a nomadic Iranian people closely related to the Scythians; and over the course of the 8th and 7th centuries BC, the Scythians migrated in several waves became the dominant population of the Caucasian Steppe as part of a significant movement of the nomadic peoples of the Eurasian Steppe

The Eurasian Steppe, also simply called the Great Steppe or the steppes, is the vast steppe ecoregion of Eurasia in the temperate grasslands, savannas and shrublands biome. It stretches through Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania, Moldova and Transnistri ...

which started when another nomadic Iranian tribe closely related to the Scythians from eastern Central Asia, either the Massagetae or the Issedones, migrated westwards, forcing the early Scythians of the to the west across the Araxes

, az, Araz, fa, ارس, tr, Aras

The Aras (also known as the Araks, Arax, Araxes, or Araz) is a river in the Caucasus. It rises in eastern Turkey and flows along the borders between Turkey and Armenia, between Turkey and the Nakhchivan excl ...

river, following which the Scythians moved into the Caspian Steppe, where they conquered the territory of the Cimmerians and assimilated most of this latter people and displaced the rest, before settling in the area between the Araxes, the Caucasus and the Lake Maeotis

The Sea of Azov ( Crimean Tatar: ''Azaq deñizi''; russian: Азовское море, Azovskoye more; uk, Азовське море, Azovs'ke more) is a sea in Eastern Europe connected to the Black Sea by the narrow (about ) Strait of Kerch, ...

.

The Scythian migration destroyed earlier cultures, with the settlements of the in the Dnipro

Dnipro, previously called Dnipropetrovsk from 1926 until May 2016, is Ukraine's fourth-largest city, with about one million inhabitants. It is located in the eastern part of Ukraine, southeast of the Ukrainian capital Kyiv on the Dnieper Rive ...

valley being largely destroyed and the centre of Cimmerian bronze production stopping existing at the time, and the Chernogorovka-Novocherkassk being disturbed during the 8th to 7th centuries BC. The migration of the Scythians also displaced other populations, including some North Caucasian groups who retreated to the west and settled in Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the Ap ...

and the Hungarian Plain

The Great Hungarian Plain (also known as Alföld or Great Alföld, hu, Alföld or ) is a plain occupying the majority of the modern territory of Hungary. It is the largest part of the wider Pannonian Plain. (However, the Great Hungarian plain ...

where they introduced Novocherkassk culture

The Chernogorivka and Novocherkassk cultures (c. 900 to 650 BC) are Iron Age steppe cultures in Ukraine and Russia, centered between the Prut and the lower Don. They are pre-Scythian cultures, associated with the Cimmerians.

In 1971 the ''Vysokaj ...

type swords, daggers, horse harnesses, and other objects: among these displaced populations from the Caucasus were the Sigynnae, who were displaced westward into the eastern part of the Pannonian Basin

The Pannonian Basin, or Carpathian Basin, is a large Sedimentary basin, basin situated in south-east Central Europe. The Geomorphology, geomorphological term Pannonian Plain is more widely used for roughly the same region though with a somewh ...

.

During this early migratory period, some groups of Scythians settled in Ciscaucasia

The North Caucasus, ( ady, Темыр Къафкъас, Temır Qafqas; kbd, Ишхъэрэ Къаукъаз, İṩxhərə Qauqaz; ce, Къилбаседа Кавказ, Q̇ilbaseda Kavkaz; , os, Цӕгат Кавказ, Cægat Kavkaz, inh, ...

and the Caucasus Mountains

The Caucasus Mountains,

: pronounced

* hy, Կովկասյան լեռներ,

: pronounced

* az, Qafqaz dağları, pronounced

* rus, Кавка́зские го́ры, Kavkázskiye góry, kɐfˈkasːkʲɪje ˈɡorɨ

* tr, Kafkas Dağla ...

' foothills to the east of the Kuban river, where they settled among the native populations of this region, and did not migrate to the south into West Asia.

Under Scythian pressure, the Cimmerians migrated to the south along the coast of the Black Sea and reached Anatolia, and the Scythians in turn later expanded to the south, following the coast of the Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, often described as the world's largest lake or a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia; east of the Caucasus, west of the broad steppe of Central Asia ...

and arrived in the Ciscaucasian steppes, from where they expanded into the region of present-day Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan (, ; az, Azərbaycan ), officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, , also sometimes officially called the Azerbaijan Republic is a transcontinental country located at the boundary of Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is a part of th ...

, where they settled and turned eastern Transcaucasia

The South Caucasus, also known as Transcaucasia or the Transcaucasus, is a geographical region on the border of Eastern Europe and Western Asia, straddling the southern Caucasus Mountains. The South Caucasus roughly corresponds to modern Arme ...

into their centre of operations in West Asia until the early 6th century BC, with this presence in West Asia being an extension of the Scythian kingdom of the steppes. During this period, the Scythian kings' headquarters were located in the Ciscaucasian steppes, and contact with the civilisation of West Asia would have an important influence on the formation of Scythian culture. This presence in Transcaucasia influenced Scythian culture: the sword and socketed bronze arrowheads with three edges, which are considered as typically "Scythian weapons," were of Transcaucasian origin and had been adopted by the Scythians during their stay in the Caucasus.

From their base in the Caucasian Steppe, during the period of the 8th to 7th centuries BC itself, the Scythians conquered the Pontic Steppe to the north of the Black Sea up to the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

river, which formed the western boundary of Scythian territory onwards, although the Scythians may also have had access to the Wallachian and Moldavian plains. This expansion displaced another nomadic Iranian people related to the Scythians, the Agathyrsi, who were the oldest Iranian population to have dominated the Pontic Steppe

Pontic, from the Greek ''pontos'' (, ), or "sea", may refer to:

The Black Sea Places

* The Pontic colonies, on its northern shores

* Pontus (region), a region on its southern shores

* The Pontic–Caspian steppe, steppelands stretching from nor ...

, and who were pushed westwards by the Scythians, away from the steppes and from their original home around Lake Maeotis

The Sea of Azov ( Crimean Tatar: ''Azaq deñizi''; russian: Азовское море, Azovskoye more; uk, Азовське море, Azovs'ke more) is a sea in Eastern Europe connected to the Black Sea by the narrow (about ) Strait of Kerch, ...

, after which the relations between the two populations remained hostile. In the Pontic Steppe, the Scythians spread throughout the territory of the Early Iranian populations of the Catacomb culture and intermarried with them.

The westward migration of the Scythians was accompanied by the introduction into the north Pontic region of articles originating in the Siberian Karasuk culture

The Karasuk culture (russian: Карасукская культура, Karasukskaya kul'tura) describes a group of late Bronze Age societies who ranged from the Aral Sea to the upper Yenisei in the east and south to the Altai Mountains and the T ...

and which were characteristic of Early Scythian archaeological culture, consisting of cast bronze cauldrons, daggers, swords, and horse harnesses. Several smaller groups were likely also displaced by the Scythian expansion.

Beginning in this period, remains associated with the early Scythians started appearing within interior Europe, especially in the Thracian

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied t ...

and Hungarian plains, although it is yet unclear whether these represent any actual Scythian migration into these regions or whether these arrived there through trade or raids.

West Asia

During the earliest phase of their presence in West Asia, the Scythians under their king

During the earliest phase of their presence in West Asia, the Scythians under their king Išpakaia

Ishpakaia (Scythian ; Akkadian: ) was a Scythian king who ruled during the period of the Scythian presence in Western Asia in the 7th century BCE.

Name

is the Akkadian form of the Scythian name , which was a hypocorostic derivation of the word ...

were allied with the Cimmerians, and the two groups, in alliance with the Medes

The Medes (Old Persian: ; Akkadian: , ; Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ) were an ancient Iranian people who spoke the Median language and who inhabited an area known as Media between western and northern Iran. Around the 11th century BC, the ...

, who were an Iranian people of West Asia to whom the Scythians and Cimmerians were distantly related, as well as the Mannaeans

Mannaea (, sometimes written as Mannea; Akkadian language, Akkadian: ''Mannai'', Biblical Hebrew: ''Minni'', (מנּי)) was an ancient kingdom located in northwestern Iran, south of Lake Urmia, around the 10th to 7th centuries BC. It neighbored ...

, were threatening the eastern frontier of the kingdom of Urartu

Urartu (; Assyrian: ',Eberhard Schrader, ''The Cuneiform inscriptions and the Old Testament'' (1885), p. 65. Babylonian: ''Urashtu'', he, אֲרָרָט ''Ararat'') is a geographical region and Iron Age kingdom also known as the Kingdom of Va ...

and the then superpower of West Asia, the Neo-Assyrian Empire

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history and the final and greatest phase of Assyria as an independent state. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew t ...

. These allied forces were defeated by the Assyrian king Esarhaddon

Esarhaddon, also spelled Essarhaddon, Assarhaddon and Ashurhaddon (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , also , meaning " Ashur has given me a brother"; Biblical Hebrew: ''ʾĒsar-Ḥaddōn'') was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his ...

, and Išpakaia was later killed in a retaliatory military campaign by Esarhaddon.

Išpakaia was succeeded by Bartatua

Bartatua (Scythian: ; Akkadian: or : "Though Madyes himself is not mentioned in Akkadian texts, his father, the Scythian king , whose identification with of Herodotus is certain.) or Protothyes (Ancient Greek: , romanized: ; Latin: ) was a Scyth ...

, who sought a rapprochement with the Assyrians and married Esarhaddon's daughter Serua-eterat

Serua-eterat or Serua-etirat (Akkadian: or , meaning "Šerua is the one who saves"), called Saritrah (Demotic arc, , ) in later Aramaic texts, was an ancient Assyrian princess of the Sargonid dynasty, the eldest daughter of Esarhaddon and the ...

. Bartatua's marriage to Serua-eterat required that he would pledge allegiance to Assyria as a vassal, with the territories ruled by him would be his fief granted by the Assyrian king, thus making the Scythian presence in West Asia an extension of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, and henceforth, the Scythians remained allies of the Assyrian Empire, with Bartatua helping the Assyrians by defeating the state of Mannai and imposing Scythian hegemony over it.

The marital alliance between the Scythian king and the Assyrian ruling dynasty, as well as the proximity of the Scythians with the Assyrian-influenced Mannai and Urartu, placed the Scythians under the strong influence of Assyrian culture.

Bartatua was succeeded by his son with Serua-eterat, Madyes

Madyes (Median: ; Ancient Greek: , romanized: ;: " “intoxicating drink” (in )" Latin: ) was a Scythian king who ruled during the period of the Scythian presence in West Asia in the 7th century BCE. Madyes was the son of the Scythian king Barta ...

, who in 653 BC invaded the Medes

The Medes (Old Persian: ; Akkadian: , ; Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ) were an ancient Iranian people who spoke the Median language and who inhabited an area known as Media between western and northern Iran. Around the 11th century BC, the ...

who were engaged in a war against Assyria, thus starting a period which Herodotus of Halicarnassus called the "Scythian rule over Asia." Madyes soon expanded the Scythian hegemony to the state of Urartu, and, soon after 635 BC, with Assyrian approval and in alliance with the Lydia

Lydia (Lydian language, Lydian: 𐤮𐤱𐤠𐤭𐤣𐤠, ''Śfarda''; Aramaic: ''Lydia''; el, Λυδία, ''Lȳdíā''; tr, Lidya) was an Iron Age Monarchy, kingdom of western Asia Minor located generally east of ancient Ionia in the mod ...

ns, the Scythians under Madyes entered Anatolia and defeated the Cimmerians. Scythian power in West Asia thus reached its peak under Madyes, with the territories ruled by the Scythians extending from the Halys river in Anatolia in the west to the Caspian Sea and the eastern borders of Media in the east, and from Transcaucasia in the north to the northern borders of the Neo-Assyrian Empire

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history and the final and greatest phase of Assyria as an independent state. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew t ...

in the south.

By the 620s BC, the Assyrian Empire began unravelling after the death of Esarhaddon's son and successor, Ashurbanipal

Ashurbanipal (Neo-Assyrian language, Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning "Ashur (god), Ashur is the creator of the heir") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 669 BCE to his death in 631. He is generally remembered as the last great king o ...

: in addition to internal instability within Assyria itself, Babylon revolted against the Assyrians in 626 BC under the leadership of Nabopolassar

Nabopolassar (Babylonian cuneiform: , meaning "Nabu, protect the son") was the founder and first king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling from his coronation as king of Babylon in 626 BC to his death in 605 BC. Though initially only aimed at res ...

, and in 625 BC the Median king Cyaxares

Cyaxares (Median: ; Old Persian: ; Akkadian: ; Old Phrygian: ; grc, Κυαξαρης, Kuaxarēs; Latin: ; reigned 625–585 BCE) was the third king of the Medes.

Cyaxares collaborated with the Babylonians to destroy the Assyrian Empire, and ...

overthrew the Scythian yoke over the Medes by assassinating the Scythian leaders, including Madyes. The Scythians soon took advantage of the power vacuum created by the crumbling of the power of their former Assyrian allies to overrun the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

and Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

until the borders of Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, from where they turned back after their advance was stopped by the marshes of the Nile Delta

The Nile Delta ( ar, دلتا النيل, or simply , is the delta formed in Lower Egypt where the Nile River spreads out and drains into the Mediterranean Sea. It is one of the world's largest river deltas—from Alexandria in the west to Po ...

and the pharaoh Psamtik I met them and convinced them to turn back by offering them gifts; they retreated through Askalōn largely without any incident, although some stragglers looted the temple of Astarte in the city; the perpetrators of this sacrilege and their descendants were allegedly afflicted by the goddess with a "female disease," due to which they became a class of transvestite diviners called the (meaning "unmanly" in Scythian). Starting around 615 BC, the Scythians were operating as allies of Cyaxares and the Medes in their war against Assyria.

The Scythians were finally expelled from West Asia by the Medes in the 600s BC, after which they retreated to the Pontic Steppe

Pontic, from the Greek ''pontos'' (, ), or "sea", may refer to:

The Black Sea Places

* The Pontic colonies, on its northern shores

* Pontus (region), a region on its southern shores

* The Pontic–Caspian steppe, steppelands stretching from nor ...

. Some splinter Scythian groups nevertheless remained in West Asia and settled in Transcaucasia, and one group formed a kingdom in the area corresponding to modern-day Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan (, ; az, Azərbaycan ), officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, , also sometimes officially called the Azerbaijan Republic is a transcontinental country located at the boundary of Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is a part of th ...

in eastern Transcaucasia. By the middle of the 6th century BC, the Scythians who had remained in West Asia had completely assimilated culturally and politically into Median society and no longer existed as a distinct group.

The Pontic Steppe

After their expulsion from West Asia, and beginning in the later 7th and lasting throughout much of the 6th century BC, the majority of the Scythians, including the Royal Scythians, migrated into the Kuban Steppe around 600 BC, and from Ciscaucasia into the Pontic Steppe, which became the centre of Scythian power, and in the western Ciscaucasia, from where the Scythians, not large in number enough to spread throughout Ciscaucasia, instead took over the steppe to the south of the Kuban river's middle course; the northwards migration of the Scythians continued throughout the 6th century BC. Using the Pontic Steppe as their base, the Scythians often raided into the adjacent regions, with Central Europe being a frequent target of their raids. In many parts of their north Pontic kingdom, the Scythians established themselves as a ruling class over already present sedentary populations, including

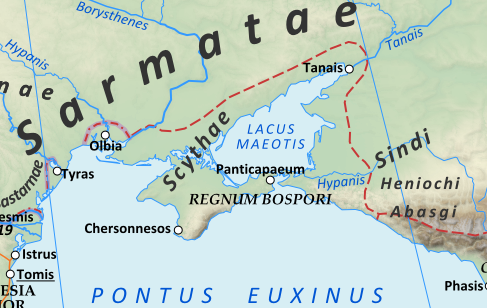

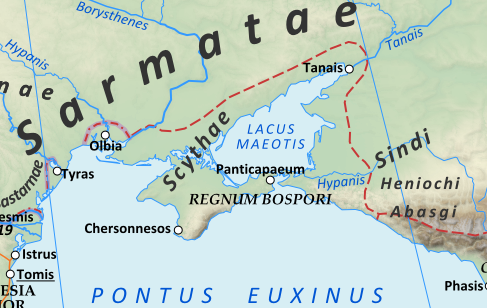

After their expulsion from West Asia, and beginning in the later 7th and lasting throughout much of the 6th century BC, the majority of the Scythians, including the Royal Scythians, migrated into the Kuban Steppe around 600 BC, and from Ciscaucasia into the Pontic Steppe, which became the centre of Scythian power, and in the western Ciscaucasia, from where the Scythians, not large in number enough to spread throughout Ciscaucasia, instead took over the steppe to the south of the Kuban river's middle course; the northwards migration of the Scythians continued throughout the 6th century BC. Using the Pontic Steppe as their base, the Scythians often raided into the adjacent regions, with Central Europe being a frequent target of their raids. In many parts of their north Pontic kingdom, the Scythians established themselves as a ruling class over already present sedentary populations, including Thracians

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European languages, Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. ...

in the western regions, Maeotians on the eastern shore of Lake Maeotis

The Sea of Azov ( Crimean Tatar: ''Azaq deñizi''; russian: Азовское море, Azovskoye more; uk, Азовське море, Azovs'ke more) is a sea in Eastern Europe connected to the Black Sea by the narrow (about ) Strait of Kerch, ...

, and later the Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, oth ...

on the north coast of the Black Sea.

Outside of the Pontic Scythian kingdom itself, some splinter Scythian groups formed the Vorskla and Sula-Donets groups of the Scythian Culture in the East European Forest Steppe.

Between 650 and 625 BC, the Scythians of the northern Pontic region came into contact with the Greeks, who were starting to create colonies in the areas under Scythian rule; the Greeks carried out thriving commercial ties with the sedentary peoples of the East European Forest Steppe who lived to the north of the Scythians, with the large rivers of eastern Europe which flowed into the Black Sea forming the main access routes to these northern markets. This process put the Scythians into permanent contact with the Greeks, and the relations between the latter and the Greek colonies remained peaceful.

In 513 BC, the king Darius I

Darius I ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was a Persian ruler who served as the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his ...

of the Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

, which had succeeded the Median, Lydian, Egyptian, and Neo-Babylonian empires which the Scythians had once interacted with, carried out a campaign against the Pontic Scythians, with the reasons for this campaign being unclear. Darius's invasion was resisted by the Scythian king Idanthyrsus, and the results of this campaign were also unclear, with the Persian inscriptions themselves referring to the Pontic Scythians as having been conquered by Darius, while Greek authors instead claimed that Darius's campaign failed and from then onwards developed a tradition of idealising the Scythians as being invincible thanks to their nomadic lifestyle.

In the 5th century BC, the Scythians embarked on expansionist ventures, including in the west, where they raided south of the Danube into Thrace until the formation of the Thracian

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied t ...

Odrysian kingdom blocked their advances, after which the Scythians formed an alliance with the Odrysians; as well as in the north, where they imposed their rule on the peoples of the forest steppe; and in the south, where they brought the Greek colonies on the northern shores of the Black Sea under their power.

The peak of the Scythian kingdom of the Pontic Steppe happened in the 4th century BC, at the same time when the Greek cities of the coast were prospering, and the relations between the two were mostly peaceful; the rule of the Spartocid dynasty

The Spartocids () or Spartocidae was the name of a Hellenized Thracian dynasty that ruled the Hellenistic Kingdom of Bosporus between the years 438–108 BC. They had usurped the former dynasty, the Archaeanactids, a Greek dynasty of the Bospor ...

in the Bosporan Kingdom

The Bosporan Kingdom, also known as the Kingdom of the Cimmerian Bosporus (, ''Vasíleio toú Kimmerikoú Vospórou''), was an ancient Greco-Scythian state located in eastern Crimea and the Taman Peninsula on the shores of the Cimmerian Bosporus, ...

was also favourable for the Scythians, and the Bosporan aristocracy had contacts with the Scythians. This period saw Scythian culture not only thriving, with most known Scythian monuments date from then, but also rapidly undergoing significant Hellenisation.

The most famous Scythian king of the 4th century BC was Ateas, whose rule started around the 360s BC, and under whom the Greek cities to the south of the Danube were brought under Scythian hegemony; Ateas's main activities in Thrace and south-west Scythia, such as his wars against the Triballi

The Triballi ( grc, Τριβαλλοί, Triballoí, lat, Triballi) were an ancient people who lived in northern Bulgaria in the region of Roman Oescus up to southeastern Serbia, possibly near the territory of the Morava Valley in the late Iron A ...

and the Histriani

Histria or Istros ( grc, Ἰστρίη, Thracian river god, Danube), was a Greek colony or ''polis'' (πόλις, city) near the mouths of the Danube (known as Ister in Ancient Greek), on the western coast of the Black Sea. It was the first urba ...

, attest of the power that the Scythians held to the south of the Danube in his time. Ateas initially allied with Philip II Philip II may refer to:

* Philip II of Macedon (382–336 BC)

* Philip II (emperor) (238–249), Roman emperor

* Philip II, Prince of Taranto (1329–1374)

* Philip II, Duke of Burgundy (1342–1404)

* Philip II, Duke of Savoy (1438-1497)

* Philip ...

of Macedonia

Macedonia most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a traditional geographic reg ...

, but eventually this alliance fell apart and Ateas was killed during a war with the Macedonians in 339 BC.

In the 3rd century BC, the expansion in the northern Pontic region of the Sarmatians, who were another nomadic Iranian people related to the Scythians, as well as of the Thracian

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied t ...

Getae

The Getae ( ) or Gets ( ; grc, Γέται, singular ) were a Thracian-related tribe that once inhabited the regions to either side of the Lower Danube, in what is today northern Bulgaria and southern Romania. Both the singular form ''Get'' an ...

, the Germanic Bastarnae and Sciri

The Sciri, or Scirians, were a Germanic people. They are believed to have spoken an East Germanic language. Their name probably means "the pure ones".

The Sciri were mentioned already in the late 3rd century BC as participants in a raid on the ...

, and of the Celts

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancien ...

, the Scythian kingdom disappeared from the Pontic Steppe and the Sarmatians replaced the Scythians as the dominant power of the Pontic Steppe, due to which the appellation of "Scythia" for the region became replaced by that of "" (European Sarmatia).

Scythia Minor

The Scythians fled to the inCrimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a pop ...

, where they were able to securely establish themselves against the Sarmatian invasion despite tensions with the Greeks, and to the in Dobrugea, as well as in nearby regions, where they became limited in enclaves. The remnants of the Scythians on the Pontic Steppe settled down in a series of fortified settlements located along the main rivers of the region. By then, these Scythians were no longer nomadic: they had become sedentary farmers and were Hellenised, and the only places where the Scythians could still be found by the 2nd century BC were in the s of Crimea and Dobrugea, as well as in the lower reaches of the Dnipro river.

By 50 to 150 AD, most of the Scythians had been assimilated by the Sarmatians. The remaining Scythians of Crimea, who had mixed with the

By 50 to 150 AD, most of the Scythians had been assimilated by the Sarmatians. The remaining Scythians of Crimea, who had mixed with the Tauri

The Tauri (; in Ancient Greek), or Taurians, also Scythotauri, Tauri Scythae, Tauroscythae (Pliny, ''H. N.'' 4.85) were an ancient people settled on the southern coast of the Crimea peninsula, inhabiting the Crimean Mountains in the 1st millenni ...

and the Sarmatians, were conquered in the 3rd century AD by the Goths

The Goths ( got, 𐌲𐌿𐍄𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰, translit=''Gutþiuda''; la, Gothi, grc-gre, Γότθοι, Gótthoi) were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Europe ...

and other Germanic tribes who were then migrating from the north into the Pontic Steppe.

Legacy

In subsequent centuries, remaining Scythians and Sarmatians were largely assimilated byearly Slavs

The early Slavs were a diverse group of tribal societies who lived during the Migration Period and the Early Middle Ages (approximately the 5th to the 10th centuries AD) in Central and Eastern Europe and established the foundations for the S ...

. The Scythians and Sarmatians played an instrumental role in the ethnogenesis

Ethnogenesis (; ) is "the formation and development of an ethnic group".

This can originate by group self-identification or by outside identification.

The term ''ethnogenesis'' was originally a mid-19th century neologism that was later introdu ...

of the Ossetians

The Ossetians or Ossetes (, ; os, ир, ирæттæ / дигорӕ, дигорӕнттӕ, translit= ir, irættæ / digoræ, digorænttæ, label=Ossetic) are an Iranian ethnic group who are indigenous to Ossetia, a region situated across the no ...

, who are considered direct descendants of the Alans.: "Iranian-speaking nomadic tribes, specifically the Scythians and Sarmatians, are special among the North Caucasian peoples. The Scytho-Sarmatians were instrumental in the ethnogenesis of some of the modern peoples living today in the Caucasus. Of importance in this group are the Ossetians, an Iranian-speaking group of people who are believed to have descended from the North Caucasian Alans."

In Late Antiquity

Late antiquity is the time of transition from classical antiquity to the Middle Ages, generally spanning the 3rd–7th century in Europe and adjacent areas bordering the Mediterranean Basin. The popularization of this periodization in English ha ...

and the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

, the name "Scythians" was used in Greco-Roman

The Greco-Roman civilization (; also Greco-Roman culture; spelled Graeco-Roman in the Commonwealth), as understood by modern scholars and writers, includes the geographical regions and countries that culturally—and so historically—were di ...

and Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

literature for various groups of nomadic "barbarian

A barbarian (or savage) is someone who is perceived to be either Civilization, uncivilized or primitive. The designation is usually applied as a generalization based on a popular stereotype; barbarians can be members of any nation judged by som ...

s" living on the Pontic-Caspian Steppe who were not related to the actual Scythians, such as the Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part ...

, Goths

The Goths ( got, 𐌲𐌿𐍄𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰, translit=''Gutþiuda''; la, Gothi, grc-gre, Γότθοι, Gótthoi) were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Europe ...

, Ostrogoths

The Ostrogoths ( la, Ostrogothi, Austrogothi) were a Roman-era Germanic peoples, Germanic people. In the 5th century, they followed the Visigoths in creating one of the two great Goths, Gothic kingdoms within the Roman Empire, based upon the larg ...

, Turkic peoples

The Turkic peoples are a collection of diverse ethnic groups of West, Central, East, and North Asia as well as parts of Europe, who speak Turkic languages.. "Turkic peoples, any of various peoples whose members speak languages belonging t ...

, Pannonian Avars

The Pannonian Avars () were an alliance of several groups of Eurasian nomads of various origins. The peoples were also known as the Obri in chronicles of Rus, the Abaroi or Varchonitai ( el, Βαρχονίτες, Varchonítes), or Pseudo-Avars ...

, Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

, and Khazars

The Khazars ; he, כּוּזָרִים, Kūzārīm; la, Gazari, or ; zh, 突厥曷薩 ; 突厥可薩 ''Tūjué Kěsà'', () were a semi-nomadic Turkic people that in the late 6th-century CE established a major commercial empire coverin ...

.: "Greek authors ..frequently applied the name Scythians to later nomadic groups who had no relation whatever to the original Scythians" For example, Byzantine sources referred to the Rus' raiders who attacked Constantinople in 860 AD in contemporary accounts as "Tauroscythians

The Tauri (; in Ancient Greek), or Taurians, also Scythotauri, Tauri Scythae, Tauroscythae (Pliny, ''H. N.'' 4.85) were an ancient people settled on the southern coast of the Crimea peninsula, inhabiting the Crimean Mountains in the 1st millenni ...

" because of their geographical origin, and despite their lack of any ethnic relation to Scythians. Scythian descent claims

Scythian descent claims refers to claims of descent from the Scythians, an Iranian people best known for dominating the Pontic steppe from about 700 BC to 400 BC. Claims of descent from the Scythians have been frequent throughout history.

Claims ...

have been frequent throughout history.

The New Testament includes a single reference to Scythians in Colossians 3:11.

Culture and society

Since the Scythians did not have a written language, their non-material culture can only be pieced together through writings by non-Scythian authors, parallels found among other Iranian peoples, and archaeological evidence. In a fragment from the comic writer Euphron quoted in ''Deipnosophistae

The ''Deipnosophistae'' is an early 3rd-century AD Greek work ( grc, Δειπνοσοφισταί, ''Deipnosophistaí'', lit. "The Dinner Sophists/Philosophers/Experts") by the Greek author Athenaeus of Naucratis. It is a long work of liter ...

'' poppy seeds are mentioned as a "food which the Scythians love."

Language

The Scythians spoke a language belonging to theScythian languages

The Scythian languages ( or or ) are a group of Eastern Iranian languages of the classical antiquity, classical and late antiquity, late antique period (the Middle Iranian languages, Middle Iranian period), spoken in a vast region of Eurasia b ...

, most probably a branch of the Eastern Iranian languages

The Eastern Iranian languages are a subgroup of the Iranian languages emerging in Middle Iranian times (from c. the 4th century BC). The Avestan language is often classified as early Eastern Iranian. As opposed to the Middle Western Iranian diale ...

. Whether all the peoples included in the "Scytho-Siberian" archaeological culture spoke languages from this family is uncertain.

The Scythian languages may have formed a dialect continuum

A dialect continuum or dialect chain is a series of Variety (linguistics), language varieties spoken across some geographical area such that neighboring varieties are Mutual intelligibility, mutually intelligible, but the differences accumulat ...

: "Scytho-Sarmatian" in the west and "Scytho-Khotanese" or Saka

The Saka ( Old Persian: ; Kharoṣṭhī: ; Ancient Egyptian: , ; , old , mod. , ), Shaka (Sanskrit ( Brāhmī): , , ; Sanskrit (Devanāgarī): , ), or Sacae (Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ) were a group of nomadic Iranian peoples who hist ...

in the east. The Scythian languages were mostly marginalised and assimilated as a consequence of the late antiquity and early Middle Ages Slavic and Turkic expansion. The western (Sarmatian) group of ancient Scythian survived as the medieval language of the Alans and eventually gave rise to the modern Ossetian language.

Lifestyle

The early Scythians tribes were nomadic pastoralists, and their lifestyle and customs were inextricably linked to their nomadic way of life; the Scythians were able to raise large herds ofhorse

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million y ...

s, cattle

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, cloven-hooved, herbivores. They are a prominent modern member of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus ''Bos''. Adult females are referred to as cows and adult mal ...

and sheep

Sheep or domestic sheep (''Ovis aries'') are domesticated, ruminant mammals typically kept as livestock. Although the term ''sheep'' can apply to other species in the genus ''Ovis'', in everyday usage it almost always refers to domesticated s ...

thanks to the abundance of grass growing in the steppe, while hunting was primarily done for sport and entertainment; among the more nomadic Scythian tribes, the women and children spent their time in wagons where they lived, while the men spent their lives on horseback and were trained as fighters and in archery since an early age. But by the time the Scythians were living in the Pontic Steppe, beginning in the 7th century BC, they had become semi-nomadic and practised both nomadism and farming, although the Scythian tribes living in the steppe zone remained primarily nomadic.

The Scythians did not use saddle

The saddle is a supportive structure for a rider of an animal, fastened to an animal's back by a girth. The most common type is equestrian. However, specialized saddles have been created for oxen, camels and other animals. It is not kno ...

s or stirrup

A stirrup is a light frame or ring that holds the foot of a rider, attached to the saddle by a strap, often called a ''stirrup leather''. Stirrups are usually paired and are used to aid in mounting and as a support while using a riding animal ( ...

s, which were a later Sarmatian invention, and they rode their horses sitting only on a piece of cloth.

Unlike the other Scythic peoples such as the Sarmatians, where women were allowed to go hunting, ride horses, learn archery and fight with spears just like the men, the society of the Scythians proper was patriarchal and Scythian women possessed little freedom. Due to the Scythians' nomadic pastoralist lifestyle, Scythian women nevertheless learnt to use weapons because they were in charge of the herds and the home when the men were away fighting in wars.

The tribe of the , who were a population of either Scythian or mixed Thracian and Scythian origin, were sedentary farmers who cultivated wheat

Wheat is a grass widely cultivated for its seed, a cereal grain that is a worldwide staple food. The many species of wheat together make up the genus ''Triticum'' ; the most widely grown is common wheat (''T. aestivum''). The archaeologi ...

, onion

An onion (''Allium cepa'' L., from Latin ''cepa'' meaning "onion"), also known as the bulb onion or common onion, is a vegetable that is the most widely cultivated species of the genus ''Allium''. The shallot is a botanical variety of the onion ...

s, garlic

Garlic (''Allium sativum'') is a species of bulbous flowering plant in the genus ''Allium''. Its close relatives include the onion, shallot, leek, chive, Allium fistulosum, Welsh onion and Allium chinense, Chinese onion. It is native to South A ...

, lentil

The lentil (''Lens culinaris'' or ''Lens esculenta'') is an edible legume. It is an annual plant known for its lens-shaped seeds. It is about tall, and the seeds grow in pods, usually with two seeds in each. As a food crop, the largest pro ...

s and millet

Millets () are a highly varied group of small-seeded grasses, widely grown around the world as cereal crops or grains for fodder and human food. Most species generally referred to as millets belong to the tribe Paniceae, but some millets al ...

.

Wine was primarily consumed by the Scythian aristocracy during the earlier phase of their kingdom in the Pontic Steppe, and its consumption became more prevalent among the wealthier members of the populace in the Late Scythian period.

Clothing

The Scythians wore clothing typical of the steppe nomads: the clothing of Scythian men included trousers and belts, they wore pointed caps during earlier periods, but they went bareheaded in later times; Scythian women wore long dresses and mantles decorated with triangular or round metallic plates, which were made of gold for wealthier women and of bronze for poorer women, and women belonging to the upper classes wore cloaks over their dresses and aveil

A veil is an article of clothing or hanging cloth that is intended to cover some part of the head or face, or an object of some significance. Veiling has a long history in European, Asian, and African societies. The practice has been prominent ...

over their head.

Scythian men and women both wore golden and brazen jewellery: both wore bracelets made of silver or bronze wire and neckrings and torcs made of gold and whose terminals were shaped like animal figures or animal heads; necklaces worn by the Scythians were made of gold and semi-precious stone beads; men wore only one earring. Scythian men also grew their hair long and their beards to significant sizes.

Costume has been regarded as one of the main identifying criteria for Scythians. Women wore a variety of different headdresses, some conical in shape others more like flattened cylinders, also adorned with metal (golden) plaques.

Men and women wore long trousers, often adorned with metal plaques and often embroidered or adorned with felt appliqués; trousers could have been wider or tight fitting depending on the area. Materials used depended on the wealth, climate and necessity.