Screw propeller on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a

The origin of the screw propeller starts at least as early as

The origin of the screw propeller starts at least as early as

In 1835, two inventors in Britain,

In 1835, two inventors in Britain,  Apparently aware of the Royal Navy's view that screw propellers would prove unsuitable for seagoing service, Smith determined to prove this assumption wrong. In September 1837, he took his small vessel (now fitted with an iron propeller of a single turn) to sea, steaming from

Apparently aware of the Royal Navy's view that screw propellers would prove unsuitable for seagoing service, Smith determined to prove this assumption wrong. In September 1837, he took his small vessel (now fitted with an iron propeller of a single turn) to sea, steaming from  was built in 1838 by Henry Wimshurst of London, as the world's first steamship to be driven by a

was built in 1838 by Henry Wimshurst of London, as the world's first steamship to be driven by a

The twisted

The twisted

video

demonstrates tip vortex cavitation. Tip vortex cavitation typically occurs before suction side surface cavitation and is less damaging to the blade, since this type of cavitation doesn't collapse on the blade, but some distance downstream.

For smaller engines, such as outboards, where the propeller is exposed to the risk of collision with heavy objects, the propeller often includes a device that is designed to fail when overloaded; the device or the whole propeller is sacrificed so that the more expensive transmission and engine are not damaged.

Typically in smaller (less than ) and older engines, a narrow

For smaller engines, such as outboards, where the propeller is exposed to the risk of collision with heavy objects, the propeller often includes a device that is designed to fail when overloaded; the device or the whole propeller is sacrificed so that the more expensive transmission and engine are not damaged.

Typically in smaller (less than ) and older engines, a narrow  Whereas the propeller on a large ship will be immersed in deep water and free of obstacles and

Whereas the propeller on a large ship will be immersed in deep water and free of obstacles and

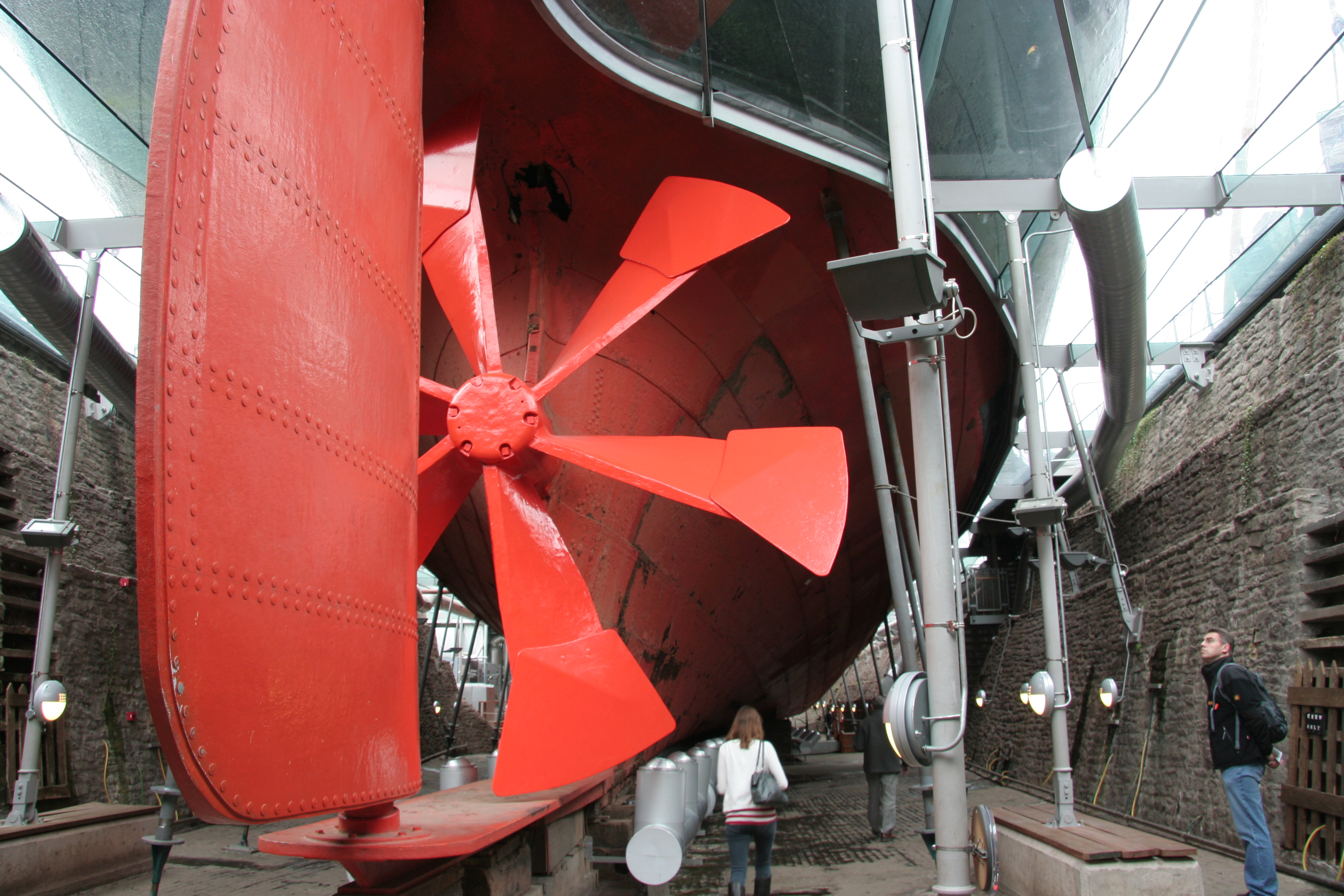

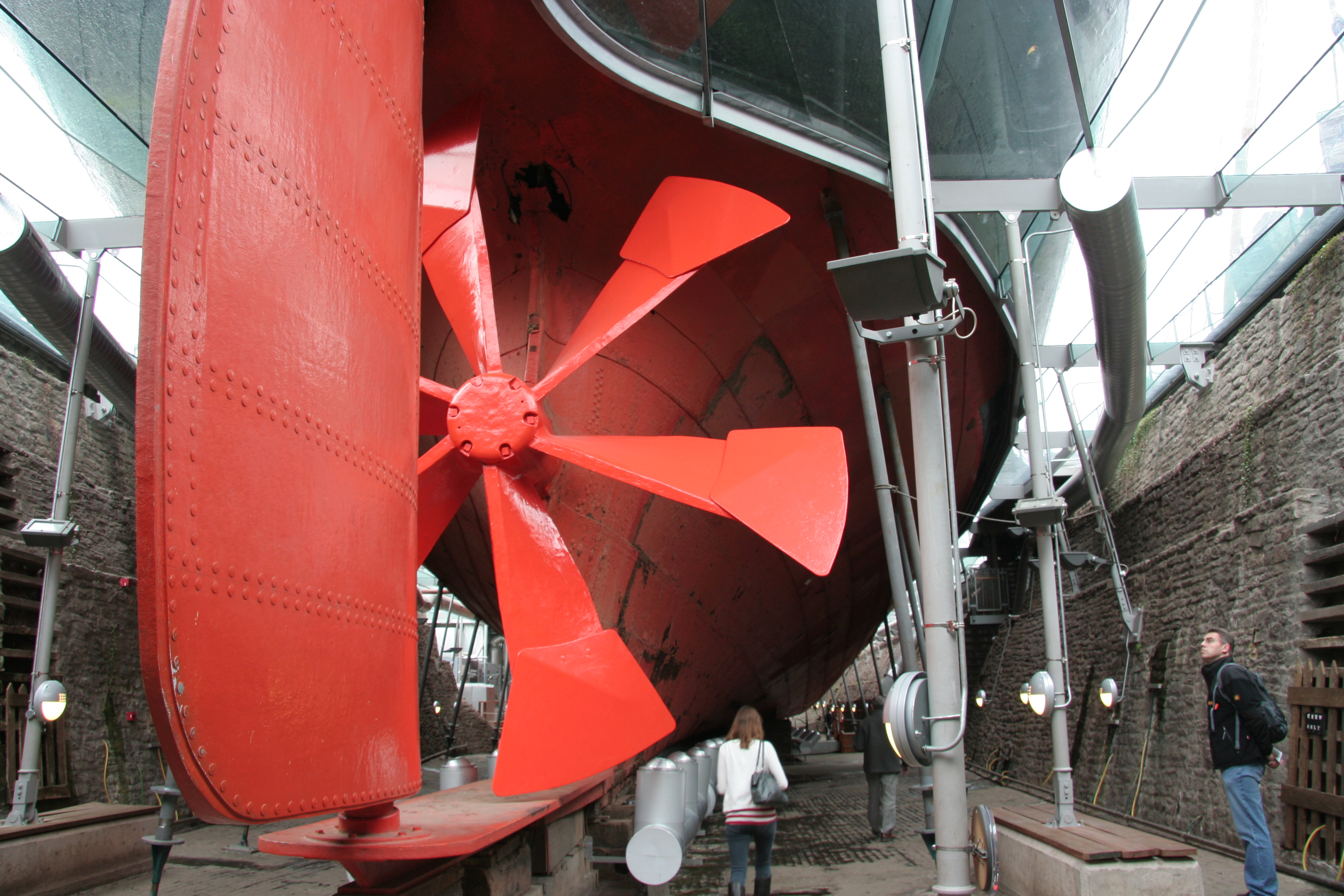

Titanic's Propellers

detailed article with blade element theory software application

"What You Should Know About Propellers For Our Fighting Planes", November 1943, ''Popular Science''

extremely detailed article with numerous drawings and cutaway illustrations

The story of marine propulsion

The story of propellers

Propulsors and gears

Wartsila Marine Propellers

Propeller Drop

Measured by

"History of the Screw Propeller"

1881, pp. 232 {{Authority control Watercraft components Swedish inventions

ship

A ship is a large watercraft that travels the world's oceans and other sufficiently deep waterways, carrying cargo or passengers, or in support of specialized missions, such as defense, research, and fishing. Ships are generally distinguished ...

or an airscrew if on an aircraft

An aircraft is a vehicle that is able to fly by gaining support from the air. It counters the force of gravity by using either static lift or by using the dynamic lift of an airfoil, or in a few cases the downward thrust from jet engines ...

) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust

Thrust is a reaction force described quantitatively by Newton's third law. When a system expels or accelerates mass in one direction, the accelerated mass will cause a force of equal magnitude but opposite direction to be applied to that syst ...

upon a working fluid such as water or air. Propellers are used to pump fluid through a pipe or duct, or to create thrust to propel a boat

A boat is a watercraft of a large range of types and sizes, but generally smaller than a ship, which is distinguished by its larger size, shape, cargo or passenger capacity, or its ability to carry boats.

Small boats are typically found on inl ...

through water or an aircraft

An aircraft is a vehicle that is able to fly by gaining support from the air. It counters the force of gravity by using either static lift or by using the dynamic lift of an airfoil, or in a few cases the downward thrust from jet engines ...

through air. The blades are specially shaped so that their rotational

Rotation, or spin, is the circular movement of an object around a '' central axis''. A two-dimensional rotating object has only one possible central axis and can rotate in either a clockwise or counterclockwise direction. A three-dimensional ...

motion through the fluid causes a pressure difference between the two surfaces of the blade by Bernoulli's principle

In fluid dynamics, Bernoulli's principle states that an increase in the speed of a fluid occurs simultaneously with a decrease in static pressure or a decrease in the fluid's potential energy. The principle is named after the Swiss mathematici ...

which exerts force on the fluid. Most marine propellers are screw propellers with helical blades rotating on a propeller shaft

A drive shaft, driveshaft, driving shaft, tailshaft (Australian English), propeller shaft (prop shaft), or Cardan shaft (after Girolamo Cardano) is a component for transmitting mechanical power and torque and rotation, usually used to connect ...

with an approximately horizontal axis.

History

Early developments

The principle employed in using a screw propeller is derived fromsculling

Sculling is the use of oars to propel a boat by moving them through the water on both sides of the craft, or moving one oar over the stern. A long, narrow boat with sliding seats, rigged with two oars per rower may be referred to as a scull, it ...

. In sculling, a single blade is moved through an arc, from side to side taking care to keep presenting the blade to the water at the effective angle. The innovation introduced with the screw propeller was the extension of that arc through more than 360° by attaching the blade to a rotating shaft. Propellers can have a single blade, but in practice there are nearly always more than one so as to balance the forces involved.

Archimedes

Archimedes of Syracuse (;; ) was a Greek mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor from the ancient city of Syracuse in Sicily. Although few details of his life are known, he is regarded as one of the leading scientists ...

(c. 287 – c. 212 BC), who used a screw to lift water for irrigation

Irrigation (also referred to as watering) is the practice of applying controlled amounts of water to land to help grow Crop, crops, Landscape plant, landscape plants, and Lawn, lawns. Irrigation has been a key aspect of agriculture for over 5,00 ...

and bailing boats, so famously that it became known as Archimedes' screw

The Archimedes screw, also known as the Archimedean screw, hydrodynamic screw, water screw or Egyptian screw, is one of the earliest hydraulic machines. Using Archimedes screws as water pumps (Archimedes screw pump (ASP) or screw pump) dates back ...

. It was probably an application of spiral movement in space (spirals were a special study of Archimedes) to a hollow segmented water-wheel used for irrigation by Egyptians

Egyptians ( arz, المَصرِيُون, translit=al-Maṣriyyūn, ; arz, المَصرِيِين, translit=al-Maṣriyyīn, ; cop, ⲣⲉⲙⲛ̀ⲭⲏⲙⲓ, remenkhēmi) are an ethnic group native to the Nile, Nile Valley in Egypt. Egyptian ...

for centuries. A flying toy, the bamboo-copter

The bamboo-copter, also known as the bamboo dragonfly or Chinese top (Chinese ''zhuqingting'' (竹蜻蜓), Japanese ''taketonbo'' ), is a toy helicopter rotor that flies up when its shaft is rapidly spun. This helicopter-like top originated in ...

, was enjoyed in China beginning around 320 AD. Later, Leonardo da Vinci adopted the screw principle to drive his theoretical helicopter, sketches of which involved a large canvas screw overhead.

In 1661, Toogood and Hays proposed using screws for waterjet propulsion, though not as a propeller. Robert Hooke

Robert Hooke FRS (; 18 July 16353 March 1703) was an English polymath active as a scientist, natural philosopher and architect, who is credited to be one of two scientists to discover microorganisms in 1665 using a compound microscope that ...

in 1681 designed a horizontal watermill which was remarkably similar to the Kirsten-Boeing vertical axis propeller designed almost two and a half centuries later in 1928; two years later Hooke modified the design to provide motive power for ships through water.Carlton, p. 1 In 1693 a Frenchman by the name of Du Quet invented a screw propeller which was tried in 1693 but later abandoned. In 1752, the ''Academie des Sciences'' in Paris granted Burnelli a prize for a design of a propeller-wheel. At about the same time, the French mathematician Alexis-Jean-Pierre Paucton suggested a water propulsion system based on the Archimedean screw. In 1771, steam-engine inventor James Watt

James Watt (; 30 January 1736 (19 January 1736 OS) – 25 August 1819) was a Scottish inventor, mechanical engineer, and chemist who improved on Thomas Newcomen's 1712 Newcomen steam engine with his Watt steam engine in 1776, which was fun ...

in a private letter suggested using "spiral oars" to propel boats, although he did not use them with his steam engines, or ever implement the idea.

One of the first practical and applied uses of a propeller was on a submarine dubbed which was designed in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1775 by Yale student and inventor David Bushnell

David Bushnell (August 30, 1740 – 1824 or 1826), of Westbrook, Connecticut, was an American inventor, a patriot, one of the first American combat engineers, a teacher, and a medical doctor.

Bushnell invented the first submarine to be used in ...

, with the help of the clock maker, engraver, and brass foundryman Isaac Doolittle

Isaac Doolittle (August 3, 1721 – February 13, 1800) was an early American clockmaker, inventor, engineer, manufacturer, militia officer, entrepreneur, printer, politician, and brass, iron, and silver artisan. Doolittle was a watchmaker and clo ...

, and with Bushnell's brother Ezra Bushnell and ship's carpenter and clock maker Phineas Pratt constructing the hull in Saybrook, Connecticut. On the night of September 6, 1776, Sergeant Ezra Lee piloted ''Turtle'' in an attack on HMS ''Eagle'' in New York Harbor. ''Turtle'' also has the distinction of being the first submarine used in battle. Bushnell later described the propeller in an October 1787 letter to Thomas Jefferson: "An oar formed upon the principle of the screw was fixed in the forepart of the vessel its axis entered the vessel and being turned one way rowed the vessel forward but being turned the other way rowed it backward. It was made to be turned by the hand or foot." The brass propeller, like all the brass and moving parts on ''Turtle'', was crafted by the "ingenious mechanic" Issac Doolittle of New Haven.

In 1785, Joseph Bramah of England proposed a propeller solution of a rod going through the underwater aft of a boat attached to a bladed propeller, though he never built it.

In February 1800, Edward Shorter

Edward Shorter (1767-1836) was an English engineer and inventor of several useful inventions including an early screw propeller.

Early life

Edward was born in London on 3 December 1767 in the parish of St Sepulchre, Newgate to Robert and Ann ...

of London proposed using a similar propeller attached to a rod angled down temporarily deployed from the deck above the waterline and thus requiring no water seal, and intended only to assist becalmed sailing vessels. He tested it on the transport ship at Gibraltar and Malta, achieving a speed of .Carlton, p. 2

In 1802, the American lawyer and inventor John Stevens built a boat with a rotary steam engine coupled to a four-bladed propeller. The craft achieved a speed of , but Stevens abandoned propellers due to the inherent danger in using the high-pressure steam engines. His subsequent vessels were paddle-wheeled boats.

By 1827, Czech-Austrian inventor Josef Ressel

Joseph Ludwig Franz Ressel ( cs, Josef Ludvík František Ressel; June 29, 1793 – October 9, 1857) was a forester and inventor of Czech-Austrian descent, who designed one of the first working ship's propellers.

Ressel was born in Chrudim, B ...

had invented a screw propeller which had multiple blades fastened around a conical base. He had tested his propeller in February 1826 on a small ship that was manually driven. He was successful in using his bronze screw propeller on an adapted steamboat (1829). His ship, ''Civetta'' of 48 gross register tons, reached a speed of about . This was the first ship successfully driven by an Archimedes screw-type propeller. After a new steam engine had an accident (cracked pipe weld) his experiments were banned by the Austro-Hungarian police as dangerous. Josef Ressel was at the time a forestry inspector for the Austrian Empire. But before this he received an Austro-Hungarian patent (license) for his propeller (1827). He died in 1857. This new method of propulsion was an improvement over the paddlewheel

A paddle wheel is a form of waterwheel or impeller in which a number of paddles are set around the periphery of the wheel. It has several uses, of which some are:

* Very low-lift water pumping, such as flooding paddy fields at no more than about ...

as it was not so affected by either ship motions or changes in draft as the vessel burned coal.

John Patch

John Patch (1781 – August 27, 1861) was a Nova Scotian fisherman who invented one of the first versions of the screw propeller.

Early life

Patch was born in Yarmouth, Nova Scotia in 1781. His father Nehemiah was a Yarmouth sea captain who died i ...

, a mariner in Yarmouth, Nova Scotia

Yarmouth is a town in southwestern Nova Scotia, Canada. A port town, industries include fishing, and tourism. It is the terminus of a ferry service to Bar Harbor, Maine, run by Bay Ferries.

History

Originally inhabited by the Mi'kmaq, the regi ...

developed a two-bladed, fan-shaped propeller in 1832 and publicly demonstrated it in 1833, propelling a row boat across Yarmouth Harbour and a small coastal schooner at Saint John, New Brunswick

Saint John is a seaport city of the Atlantic Ocean located on the Bay of Fundy in the province of New Brunswick, Canada. Saint John is the oldest incorporated city in Canada, established by royal charter on May 18, 1785, during the reign of Ki ...

, but his patent application in the United States was rejected until 1849 because he was not an American citizen. His efficient design drew praise in American scientific circles but by this time there were multiple competing versions of the marine propeller.

Screw propellers

Although there was much experimentation with screw propulsion before the 1830s, few of these inventions were pursued to the testing stage, and those that were proved unsatisfactory for one reason or another. In 1835, two inventors in Britain,

In 1835, two inventors in Britain, John Ericsson

John Ericsson (born Johan Ericsson; July 31, 1803 – March 8, 1889) was a Swedish-American inventor. He was active in England and the United States.

Ericsson collaborated on the design of the railroad steam locomotive ''Novelty'', which com ...

and Francis Pettit Smith

Sir Francis Pettit Smith (9 February 1808 – 12 February 1874) was an English inventor and, along with John Ericsson, one of the inventors of the screw propeller. He was also the driving force behind the construction of the world's first scr ...

, began working separately on the problem. Smith was first to take out a screw propeller patent on 31 May, while Ericsson, a gifted Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

engineer then working in Britain, filed his patent six weeks later.Bourne, p. 84. Smith quickly built a small model boat to test his invention, which was demonstrated first on a pond at his Hendon

Hendon is an urban area in the Borough of Barnet, North-West London northwest of Charing Cross. Hendon was an ancient manor and parish in the county of Middlesex and a former borough, the Municipal Borough of Hendon; it has been part of Great ...

farm, and later at the Royal Adelaide Gallery of Practical Science in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

, where it was seen by the Secretary of the Navy, Sir William Barrow. Having secured the patronage of a London banker named Wright, Smith then built a , canal boat of six tons burthen

Builder's Old Measurement (BOM, bm, OM, and o.m.) is the method used in England from approximately 1650 to 1849 for calculating the cargo capacity of a ship. It is a volumetric measurement of cubic capacity. It estimated the tonnage of a ship bas ...

called ''Francis Smith'', which was fitted with a wooden propeller of his own design and demonstrated on the Paddington Canal

The Grand Junction Canal is a canal in England from Braunston in Northamptonshire to the River Thames at Brentford, with a number of branches. The mainline was built between 1793 and 1805, to improve the route from the Midlands to London, by-p ...

from November 1836 to September 1837. By a fortuitous accident, the wooden propeller of two turns was damaged during a voyage in February 1837, and to Smith's surprise the broken propeller, which now consisted of only a single turn, doubled the boat's previous speed, from about four miles an hour to eight. Smith would subsequently file a revised patent in keeping with this accidental discovery.

In the meantime, Ericsson built a screw-propelled steamboat, ''Francis B. Ogden'' in 1837, and demonstrated his boat on the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

to senior members of the British Admiralty

The Admiralty was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom responsible for the command of the Royal Navy until 1964, historically under its titular head, the Lord High Admiral – one of the Great Officers of State. For much of it ...

, including Surveyor of the Navy

The Surveyor of the Navy also known as Department of the Surveyor of the Navy and originally known as Surveyor and Rigger of the Navy was a former principal commissioner and member of both the Navy Board from the inauguration of that body in 15 ...

Sir William Symonds. In spite of the boat achieving a speed of 10 miles an hour, comparable with that of existing paddle steamer

A paddle steamer is a steamship or steamboat powered by a steam engine that drives paddle wheels to propel the craft through the water. In antiquity, paddle wheelers followed the development of poles, oars and sails, where the first uses wer ...

s, Symonds and his entourage were unimpressed. The Admiralty maintained the view that screw propulsion would be ineffective in ocean-going service, while Symonds himself believed that screw propelled ships could not be steered efficiently.In the case of ''Francis B. Ogden'', Symonds was correct. Ericsson had made the mistake of placing the rudder forward of the propellers, which made the rudder ineffective. Symonds believed that Ericsson tried to disguise the problem by towing a barge during the test. Following this rejection, Ericsson built a second, larger screw-propelled boat, ''Robert F. Stockton'', and had her sailed in 1839 to the United States, where he was soon to gain fame as the designer of the U.S. Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage o ...

's first screw-propelled warship, .Bourne, pp. 87–89.

Blackwall, London

Blackwall is an area of Poplar, in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, East London. The neighbourhood includes Leamouth and the Coldharbour conservation area.

The area takes its name from a historic stretch of riverside wall built along ...

to Hythe, Kent

Hythe () is a coastal market town on the edge of Romney Marsh, in the district of Folkestone and Hythe on the south coast of Kent. The word ''Hythe'' or ''Hithe'' is an Old English word meaning haven or landing place.

History

The town has m ...

, with stops at Ramsgate

Ramsgate is a seaside resort, seaside town in the district of Thanet District, Thanet in east Kent, England. It was one of the great English seaside towns of the 19th century. In 2001 it had a population of about 40,000. In 2011, according to t ...

, Dover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maidstone ...

and Folkestone

Folkestone ( ) is a port town on the English Channel, in Kent, south-east England. The town lies on the southern edge of the North Downs at a valley between two cliffs. It was an important harbour and shipping port for most of the 19th and 20t ...

. On the way back to London on the 25th, Smith's craft was observed making headway in stormy seas by officers of the Royal Navy. The Admiralty's interest in the technology was revived, and Smith was encouraged to build a full size ship to more conclusively demonstrate the technology's effectiveness.Bourne, p. 85.

was built in 1838 by Henry Wimshurst of London, as the world's first steamship to be driven by a

was built in 1838 by Henry Wimshurst of London, as the world's first steamship to be driven by a screw propeller

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon ...

.

The ''Archimedes'' had considerable influence on ship development, encouraging the adoption of screw propulsion by the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

, in addition to her influence on commercial vessels. Trials with Smith's ''Archimedes'' led to the tug-of-war

Tug of war (also known as tug o' war, tug war, rope war, rope pulling, or tugging war) is a sport that pits two teams against each other in a test of strength: teams pull on opposite ends of a rope, with the goal being to bring the rope a certa ...

competition in 1845 between and with the screw-driven ''Rattler'' pulling the paddle steamer ''Alecto'' backward at .

The ''Archimedes'' also influenced the design of Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel (; 9 April 1806 – 15 September 1859) was a British civil engineer who is considered "one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history," "one of the 19th-century engineering giants," and "one ...

's in 1843, then the world's largest ship and the first screw-propelled steamship to cross the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

in August 1845.

and were both heavily modified to become the first Royal Navy ships to have steam-powered engines and screw propellers. Both participated in Franklin's lost expedition

Franklin's lost expedition was a failed British voyage of Arctic exploration led by Captain Sir John Franklin that departed England in 1845 aboard two ships, and , and was assigned to traverse the last unnavigated sections of the Northwest ...

, last seen in July 1845 near Baffin Bay

Baffin Bay ( Inuktitut: ''Saknirutiak Imanga''; kl, Avannaata Imaa; french: Baie de Baffin), located between Baffin Island and the west coast of Greenland, is defined by the International Hydrographic Organization as a marginal sea of the Arct ...

.

Screw propeller design stabilized in the 1880s.

Shaftless propellers

Propellers without a central shaft consist of propeller blades attached to a ring which is part of a circle-shaped electric motor. This design is known as arim-driven thruster

The rim-driven thruster, also known as rim-driven propulsor/propeller (or RDP) is a novel type of electric propulsion unit for ships. The concept was proposed by Kort around 1940, but only became commercially practical in the early 21st century ...

and is used by some self-guided robotic ships. Rim driven propulsion systems are increasingly being considered for use.

Aircraft propellers

The twisted

The twisted aerofoil

An airfoil (American English) or aerofoil (British English) is the cross-sectional shape of an object whose motion through a gas is capable of generating significant lift, such as a wing, a sail, or the blades of propeller, rotor, or turbine.

...

shape of modern aircraft propellers was pioneered by the Wright brothers. While some earlier engineers had attempted to model air propellers on marine propellers, the Wrights realized that an air propeller (also known as an airscrew) is essentially the same as a wing

A wing is a type of fin that produces lift while moving through air or some other fluid. Accordingly, wings have streamlined cross-sections that are subject to aerodynamic forces and act as airfoils. A wing's aerodynamic efficiency is expres ...

, and were able to use data from their earlier wind tunnel experiments on wings. They also introduced a twist along the length of the blades. This was necessary to ensure the angle of attack

In fluid dynamics, angle of attack (AOA, α, or \alpha) is the angle between a reference line on a body (often the chord line of an airfoil) and the vector representing the relative motion between the body and the fluid through which it is m ...

of the blades was kept relatively constant along their length. Their original propeller blades were only about 5% less efficient than the modern equivalent, some 100 years later. The understanding of low speed propeller aerodynamics was fairly complete by the 1920s, but later requirements to handle more power in smaller diameter have made the problem more complex.

Alberto Santos Dumont

Alberto Santos-Dumont ( Palmira, 20 July 1873 — Guarujá, 23 July 1932) was a Brazilian aeronaut, sportsman, inventor, and one of the few people to have contributed significantly to the early development of both lighter-than-air and heavier- ...

, another early pioneer, applied the knowledge he gained from experiences with airships to make a propeller with a steel shaft and aluminium blades for his 14 bis biplane. Some of his designs used a bent aluminium sheet for blades, thus creating an airfoil shape. They were heavily undercambered, and this plus the absence of lengthwise twist made them less efficient than the Wright propellers. Even so, this was perhaps the first use of aluminium in the construction of an airscrew.

Propeller theory

In the nineteenth century, several theories concerning propellers were proposed. Themomentum theory

In fluid dynamics, momentum theory or disk actuator theory is a theory describing a mathematical model of an ideal actuator disk, such as a propeller or helicopter rotor, by W.J.M. Rankine (1865), Alfred George Greenhill (1888) and (1889).

The ...

or disk actuator theory – a theory describing a mathematical model

A mathematical model is a description of a system using mathematical concepts and language. The process of developing a mathematical model is termed mathematical modeling. Mathematical models are used in the natural sciences (such as physics, ...

of an ideal propeller – was developed by W.J.M. Rankine (1865), A.G. Greenhill (1888) and R.E. Froude (1889). The propeller is modelled as an infinitely thin disc, inducing a constant velocity along the axis of rotation and creating a flow around the propeller.

A screw turning through a solid will have zero "slip"; but as a propeller screw operates in a fluid (either air or water), there will be some losses. The most efficient propellers are large-diameter, slow-turning screws, such as on large ships; the least efficient are small-diameter and fast-turning (such as on an outboard motor). Using Newton's laws of motion, one may usefully think of a propeller's forward thrust as being a reaction proportionate to the mass of fluid sent backward per time and the speed the propeller adds to that mass, and in practice there is more loss associated with producing a fast jet than with creating a heavier, slower jet. (The same applies in aircraft, in which larger-diameter turbofan

The turbofan or fanjet is a type of airbreathing jet engine that is widely used in aircraft engine, aircraft propulsion. The word "turbofan" is a portmanteau of "turbine" and "fan": the ''turbo'' portion refers to a gas turbine engine which ac ...

engines tend to be more efficient than earlier, smaller-diameter turbofans, and even smaller turbojet

The turbojet is an airbreathing jet engine which is typically used in aircraft. It consists of a gas turbine with a propelling nozzle. The gas turbine has an air inlet which includes inlet guide vanes, a compressor, a combustion chamber, and ...

s, which eject less mass at greater speeds.)

Propeller geometry

The geometry of a marine screw propeller is based on ahelicoid

The helicoid, also known as helical surface, after the plane and the catenoid, is the third minimal surface to be known.

Description

It was described by Euler in 1774 and by Jean Baptiste Meusnier in 1776. Its name derives from its similarit ...

al surface. This may form the face of the blade, or the faces of the blades may be described by offsets from this surface. The back of the blade is described by offsets from the helicoid surface in the same way that an aerofoil

An airfoil (American English) or aerofoil (British English) is the cross-sectional shape of an object whose motion through a gas is capable of generating significant lift, such as a wing, a sail, or the blades of propeller, rotor, or turbine.

...

may be described by offsets from the chord line. The pitch surface may be a true helicoid or one having a warp to provide a better match of angle of attack to the wake velocity over the blades. A warped helicoid is described by specifying the shape of the radial reference line and the pitch angle in terms of radial distance. The traditional propeller drawing includes four parts: a side elevation, which defines the rake, the variation of blade thickness from root to tip, a longitudinal section through the hub, and a projected outline of a blade onto a longitudinal centreline plane. The expanded blade view shows the section shapes at their various radii, with their pitch faces drawn parallel to the base line, and thickness parallel to the axis. The outline indicated by a line connecting the leading and trailing tips of the sections depicts the expanded blade outline. The pitch diagram shows variation of pitch with radius from root to tip. The transverse view shows the transverse projection of a blade and the developed outline of the blade.

The ''blades'' are the foil section plates that develop thrust when the propeller is rotated

The ''hub'' is the central part of the propeller, which connects the blades together and fixes the propeller to the shaft.

''Rake'' is the angle of the blade to a radius perpendicular to the shaft.

''Skew'' is the tangential offset of the line of maximum thickness to a radius

The propeller characteristics are commonly expressed as dimensionless ratios:

* Pitch ratio ''PR'' = propeller pitch/propeller diameter, or P/D

* Disk area A0 = πD2/4

* Expanded area ratio = AE/A0, where expanded area AE = Expanded area of all blades outside of the hub.

* Developed area ratio = AD/A0, where developed area AD = Developed area of all blades outside of the hub

* Projected area ratio = AP/A0, where projected area AP = Projected area of all blades outside of the hub

* Mean width ratio = (Area of one blade outside the hub/length of the blade outside the hub)/Diameter

* Blade width ratio = Maximum width of a blade/Diameter

* Blade thickness fraction = Thickness of a blade produced to shaft axis/Diameter

Cavitation

Cavitation

Cavitation is a phenomenon in which the static pressure of a liquid reduces to below the liquid's vapour pressure, leading to the formation of small vapor-filled cavities in the liquid. When subjected to higher pressure, these cavities, cal ...

is the formation of vapor bubbles in water near a moving propeller blade in regions of very low pressure. It can occur if an attempt is made to transmit too much power through the screw, or if the propeller is operating at a very high speed. Cavitation can waste power, create vibration and wear, and cause damage to the propeller. It can occur in many ways on a propeller. The two most common types of propeller cavitation are suction side surface cavitation and tip vortex cavitation.

Suction side surface cavitation forms when the propeller is operating at high rotational speeds or under heavy load (high blade lift coefficient

In fluid dynamics, the lift coefficient () is a dimensionless quantity that relates the lift generated by a lifting body to the fluid density around the body, the fluid velocity and an associated reference area. A lifting body is a foil or a com ...

). The pressure on the upstream surface of the blade (the "suction side") can drop below the vapor pressure

Vapor pressure (or vapour pressure in English-speaking countries other than the US; see spelling differences) or equilibrium vapor pressure is defined as the pressure exerted by a vapor in thermodynamic equilibrium with its condensed phases ...

of the water, resulting in the formation of a vapor pocket. Under such conditions, the change in pressure between the downstream surface of the blade (the "pressure side") and the suction side is limited, and eventually reduced as the extent of cavitation is increased. When most of the blade surface is covered by cavitation, the pressure difference between the pressure side and suction side of the blade drops considerably, as does the thrust produced by the propeller. This condition is called "thrust breakdown". Operating the propeller under these conditions wastes energy, generates considerable noise, and as the vapor bubbles collapse it rapidly erodes the screw's surface due to localized shock wave

In physics, a shock wave (also spelled shockwave), or shock, is a type of propagating disturbance that moves faster than the local speed of sound in the medium. Like an ordinary wave, a shock wave carries energy and can propagate through a med ...

s against the blade surface.

Tip vortex cavitation is caused by the extremely low pressures formed at the core of the tip vortex. The tip vortex is caused by fluid wrapping around the tip of the propeller; from the pressure side to the suction side. Thivideo

demonstrates tip vortex cavitation. Tip vortex cavitation typically occurs before suction side surface cavitation and is less damaging to the blade, since this type of cavitation doesn't collapse on the blade, but some distance downstream.

Types of marine propellers

Controllable-pitch propeller

Variable-pitch propellers (also known as controllable-pitch propellers) have significant advantages over the fixed-pitch variety. Advantages include: * the ability to select the most effective blade angle for any given speed * when motorsailing, the ability to coarsen the blade angle to attain the optimum drive from wind and engines * the ability to move astern (in reverse) much more efficiently (fixed props perform very poorly in astern) * the ability to "feather" the blades to give the least resistance when not in use (for example, when sailing)Skewback propeller

An advanced type of propeller used on GermanType 212 submarine

The German Type 212 class (German: U-Boot-Klasse 212 A), also Italian ''Todaro'' class, is a diesel-electric submarine developed by Howaldtswerke-Deutsche Werft AG (HDW) for the German and Italian navies. It features diesel propulsion and an a ...

s is called a skewback propeller. As in the scimitar blades used on some aircraft, the blade tips of a skewback propeller are swept back against the direction of rotation. In addition, the blades are tilted rearward along the longitudinal axis, giving the propeller an overall cup-shaped appearance. This design preserves thrust efficiency while reducing cavitation, and thus makes for a quiet, stealthy design.

A small number of ships use propellers with winglet

Wingtip devices are intended to improve the efficiency of fixed-wing aircraft by reducing drag. Although there are several types of wing tip devices which function in different manners, their intended effect is always to reduce an aircraft' ...

s similar to those on some airplane wings, reducing tip vortices and improving efficiency.

Modular propeller

Amodular propeller Unlike a standard one-piece boat or aircraft propeller, a modular propeller is made up of using a number of replaceable parts, typically:

* a set of matched blades;

* a propeller hub; and

* an end cap to retain the blades and to secure the propell ...

provides more control over the boat's performance. There is no need to change an entire propeller when there is an opportunity to only change the pitch or the damaged blades. Being able to adjust pitch will allow for boaters to have better performance while in different altitudes, water sports, or cruising.

Voith Schneider propeller

Voith Schneider propeller

The Voith Schneider Propeller (VSP) is a specialized marine propulsion system (MPS) manufactured by the Voith Group based on a cyclorotor design. It is highly maneuverable, being able to change the direction of its thrust almost instantaneously ...

s use four untwisted straight blades turning around a vertical axis instead of helical blades and can provide thrust in any direction at any time, at the cost of higher mechanical complexity.

Damage protection

Shaft protection For smaller engines, such as outboards, where the propeller is exposed to the risk of collision with heavy objects, the propeller often includes a device that is designed to fail when overloaded; the device or the whole propeller is sacrificed so that the more expensive transmission and engine are not damaged.

Typically in smaller (less than ) and older engines, a narrow

For smaller engines, such as outboards, where the propeller is exposed to the risk of collision with heavy objects, the propeller often includes a device that is designed to fail when overloaded; the device or the whole propeller is sacrificed so that the more expensive transmission and engine are not damaged.

Typically in smaller (less than ) and older engines, a narrow shear pin {{unreferenced, date=September 2018

A shear pin is a mechanical detail designed to allow a specific outcome to occur once a predetermined force is applied. It can either function as a safeguard designed to break to protect other parts, or as a con ...

through the drive shaft and propeller hub transmits the power of the engine at normal loads. The pin is designed to shear

Shear may refer to:

Textile production

*Animal shearing, the collection of wool from various species

**Sheep shearing

*The removal of nap during wool cloth production

Science and technology Engineering

*Shear strength (soil), the shear strength ...

when the propeller is put under a load that could damage the engine. After the pin is sheared the engine is unable to provide propulsive power to the boat until a new shear pin is fitted.

In larger and more modern engines, a rubber bushing transmits the torque

In physics and mechanics, torque is the rotational equivalent of linear force. It is also referred to as the moment of force (also abbreviated to moment). It represents the capability of a force to produce change in the rotational motion of th ...

of the drive shaft to the propeller's hub. Under a damaging load the friction

Friction is the force resisting the relative motion of solid surfaces, fluid layers, and material elements sliding against each other. There are several types of friction:

*Dry friction is a force that opposes the relative lateral motion of t ...

of the bushing in the hub is overcome and the rotating propeller slips on the shaft, preventing overloading of the engine's components. After such an event the rubber bushing may be damaged. If so, it may continue to transmit reduced power at low revolutions, but may provide no power, due to reduced friction, at high revolutions. Also, the rubber bushing may perish over time leading to its failure under loads below its designed failure load.

Whether a rubber bushing can be replaced or repaired depends upon the propeller; some cannot. Some can, but need special equipment to insert the oversized bushing for an interference fit

An interference fit, also known as a pressed fit or friction fit is a form of fastening between two ''tight'' fitting mating parts that produces a joint which is held together by friction after the parts are pushed together.

Depending on the am ...

. Others can be replaced easily. The "special equipment" usually consists of a funnel, a press and rubber lubricant (soap). If one does not have access to a lathe, an improvised funnel can be made from steel tube and car body filler; as the filler is only subject to compressive forces it is able to do a good job. Often, the bushing can be drawn into place with nothing more complex than a couple of nuts, washers and a threaded rod. A more serious problem with this type of propeller is a "frozen-on" spline bushing, which makes propeller removal impossible. In such cases the propeller must be heated in order to deliberately destroy the rubber insert. Once the propeller is removed, the splined tube can be cut away with a grinder and a new spline bushing is then required. To prevent a recurrence of the problem, the splines can be coated with anti-seize anti-corrosion compound.

In some modern propellers, a hard polymer insert called a ''drive sleeve'' replaces the rubber bushing. The splined or other non-circular cross section of the sleeve inserted between the shaft and propeller hub transmits the engine torque to the propeller, rather than friction. The polymer is weaker than the components of the propeller and engine so it fails before they do when the propeller is overloaded. This fails completely under excessive load, but can easily be replaced.

Weed hatches and rope cutters

Whereas the propeller on a large ship will be immersed in deep water and free of obstacles and

Whereas the propeller on a large ship will be immersed in deep water and free of obstacles and flotsam

In maritime law, flotsam'','' jetsam'','' lagan'','' and derelict are specific kinds of shipwreck. The words have specific nautical meanings, with legal consequences in the law of admiralty and marine salvage. A shipwreck is defined as the rema ...

, yacht

A yacht is a sailing or power vessel used for pleasure, cruising, or racing. There is no standard definition, though the term generally applies to vessels with a cabin intended for overnight use. To be termed a , as opposed to a , such a pleasu ...

s, barge

Barge nowadays generally refers to a flat-bottomed inland waterway vessel which does not have its own means of mechanical propulsion. The first modern barges were pulled by tugs, but nowadays most are pushed by pusher boats, or other vessels ...

s and river boats often suffer propeller fouling by debris such as weed, ropes, cables, nets and plastics. British narrowboat

A narrowboat is a particular type of canal boat, built to fit the narrow locks of the United Kingdom. The UK's canal system provided a nationwide transport network during the Industrial Revolution, but with the advent of the railways, commerc ...

s invariably have a weed hatch over the propeller, and once the narrowboat is stationary, the hatch may be opened to give access to the propeller, enabling debris to be cleared. Yachts and river boats rarely have weed hatches; instead they may fit a rope cutter that fits around the prop shaft and rotates with the propeller. These cutters clear the debris and obviate the need for divers to attend manually to the fouling. Several forms of rope cutters are available:

#A simple sharp edged disc that cuts like a razor;

#A rotor with two or more projecting blades that slice against a fixed blade, cutting with a scissor action;

#A serrated rotor with a complex cutting edge made up of sharp edges and projections.Images of rope cutters. https://www.bing.com/images/search?q=yacht+rope+cutter&id=9A2642834983B967EF5261F4A95842DA499E0528&form=IQFRBA&first=1&scenario=ImageBasicHover

Propeller variations

A cleaver is a type of propeller design especially used for boat racing. Its leading edge is formed round, while thetrailing edge

The trailing edge of an aerodynamic surface such as a wing is its rear edge, where the airflow separated by the leading edge meets.Crane, Dale: ''Dictionary of Aeronautical Terms, third edition'', page 521. Aviation Supplies & Academics, 1997. ...

is cut straight. It provides little bow lift, so that it can be used on boats that do not need much bow lift, for instance hydroplanes

Hydroplaning and hydroplane may refer to:

* Aquaplaning or hydroplaning, a loss of steering or braking due to water on the road

* Hydroplane (boat), a fast motor boat used in racing

** Hydroplane racing, a sport involving racing hydroplanes on lak ...

, that naturally have enough hydrodynamic bow lift. To compensate for the lack of bow lift, a hydrofoil

A hydrofoil is a lifting surface, or foil, that operates in water. They are similar in appearance and purpose to aerofoils used by aeroplanes. Boats that use hydrofoil technology are also simply termed hydrofoils. As a hydrofoil craft gains sp ...

may be installed on the lower unit. Hydrofoils reduce bow lift and help to get a boat out of the hole and onto plane.

See also

*Propeller characteristics

* *Propeller phenomena

* *Other

* ** * * ** * * * * * * * * * * * *Materials and manufacture

* *Notes

External links

Titanic's Propellers

detailed article with blade element theory software application

"What You Should Know About Propellers For Our Fighting Planes", November 1943, ''Popular Science''

extremely detailed article with numerous drawings and cutaway illustrations

The story of marine propulsion

The story of propellers

Propulsors and gears

Wartsila Marine Propellers

Propeller Drop

Measured by

feeler gauge

A feeler gauge is a tool used to measure gap widths. Feeler gauges are mostly used in engineering to measure the clearance between two parts.

Description

They consist of a number of small lengths of steel of different thicknesses with measureme ...

* ''Scientific American

''Scientific American'', informally abbreviated ''SciAm'' or sometimes ''SA'', is an American popular science magazine. Many famous scientists, including Albert Einstein and Nikola Tesla, have contributed articles to it. In print since 1845, it i ...

''"History of the Screw Propeller"

1881, pp. 232 {{Authority control Watercraft components Swedish inventions