Schottky Emission on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thermionic emission is the liberation of

Thermionic emission is the liberation of

In electron emission devices, especially

In electron emission devices, especially

How vacuum tubes really work with a section on thermionic emission, with equations

john-a-harper.com.

Thermionic Phenomena and the Laws which Govern Them

Owen Richardson's Nobel lecture on thermionics. nobelprize.org. December 12, 1929. (PDF)

Derivations of thermionic emission equations from an undergraduate lab

, csbsju.edu. {{Authority control Atomic physics Electricity Energy conversion Vacuum tubes Thomas Edison

Thermionic emission is the liberation of

Thermionic emission is the liberation of charged particles

In physics, a charged particle is a particle with an electric charge. For example, some elementary particles, like the electron or quarks are charged. Some composite particles like protons are charged particles. An ion, such as a molecule or atom ...

from a hot electrode

An electrode is an electrical conductor used to make contact with a nonmetallic part of a circuit (e.g. a semiconductor, an electrolyte, a vacuum or a gas). In electrochemical cells, electrodes are essential parts that can consist of a varie ...

whose thermal energy

The term "thermal energy" is often used ambiguously in physics and engineering. It can denote several different physical concepts, including:

* Internal energy: The energy contained within a body of matter or radiation, excluding the potential en ...

gives some particles enough kinetic energy

In physics, the kinetic energy of an object is the form of energy that it possesses due to its motion.

In classical mechanics, the kinetic energy of a non-rotating object of mass ''m'' traveling at a speed ''v'' is \fracmv^2.Resnick, Rober ...

to escape the material's surface. The particles, sometimes called ''thermions'' in early literature, are now known to be ions

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge. The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by convent ...

or electrons

The electron (, or in nuclear reactions) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary charge, elementary electric charge. It is a fundamental particle that comprises the ordinary matter that makes up the universe, along with up qua ...

. Thermal electron emission specifically refers to emission of electrons and occurs when thermal energy overcomes the material's work function

In solid-state physics, the work function (sometimes spelled workfunction) is the minimum thermodynamic work (i.e., energy) needed to remove an electron from a solid to a point in the vacuum immediately outside the solid surface. Here "immediately" ...

.

After emission, an opposite charge of equal magnitude to the emitted charge is initially left behind in the emitting region. But if the emitter is connected to a battery, that remaining charge is neutralized by charge supplied by the battery as particles are emitted, so the emitter will have the same charge it had before emission. This facilitates additional emission to sustain an electric current

An electric current is a flow of charged particles, such as electrons or ions, moving through an electrical conductor or space. It is defined as the net rate of flow of electric charge through a surface. The moving particles are called charge c ...

. Thomas Edison

Thomas Alva Edison (February11, 1847October18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices in fields such as electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and motion pictures. These inventions, ...

in 1880 while inventing his light bulb noticed this current, so subsequent scientists referred to the current as the Edison effect, though it wasn't until after the 1897 discovery of the electron that scientists understood that electrons were emitted and why.

Thermionic emission is crucial to the operation of a variety of electronic devices and can be used for electricity generation

Electricity generation is the process of generating electric power from sources of primary energy. For electric utility, utilities in the electric power industry, it is the stage prior to its Electricity delivery, delivery (Electric power transm ...

(such as thermionic converter

A thermionic converter consists of a hot electrode which thermionically emits electrons over a potential energy barrier to a cooler electrode, producing a useful electric power output. Caesium vapor is used to optimize the electrode work functi ...

s and electrodynamic tether

Electrodynamic tethers (EDTs) are long conducting wires, such as one deployed from a tether satellite, which can operate on electromagnetism, electromagnetic principles as electrical generator, generators, by converting their kinetic energy to ele ...

s) or cooling. Thermionic vacuum tubes

A vacuum tube, electron tube, thermionic valve (British usage), or tube (North America) is a device that controls electric current flow in a high vacuum between electrodes to which an electric voltage, potential difference has been applied. It ...

emit electrons from a hot cathode

In vacuum tubes and gas-filled tubes, a hot cathode or thermionic cathode is a cathode electrode which is heated to make it emit electrons due to thermionic emission. This is in contrast to a cold cathode, which does not have a heating element ...

into an enclosed vacuum

A vacuum (: vacuums or vacua) is space devoid of matter. The word is derived from the Latin adjective (neuter ) meaning "vacant" or "void". An approximation to such vacuum is a region with a gaseous pressure much less than atmospheric pressur ...

and may steer those emitted electrons with applied voltage

Voltage, also known as (electrical) potential difference, electric pressure, or electric tension, is the difference in electric potential between two points. In a Electrostatics, static electric field, it corresponds to the Work (electrical), ...

. The hot cathode can be a metal filament, a coated metal filament, or a separate structure of metal or carbides

In chemistry, a carbide usually describes a compound composed of carbon and a metal. In metallurgy, carbiding or carburizing is the process for producing carbide coatings on a metal piece.

Interstitial / Metallic carbides

The carbides of t ...

or borides

A boride is a compound between boron and a less electronegative element, for example silicon boride (SiB3 and SiB6). The borides are a very large group of compounds that are generally high melting and are covalent more than ionic in nature. Some b ...

of transition metals

In chemistry, a transition metal (or transition element) is a chemical element in the d-block of the periodic table (groups 3 to 12), though the elements of group 12 (and less often group 3) are sometimes excluded. The lanthanide and actinid ...

. Vacuum emission from metals

A metal () is a material that, when polished or fractured, shows a lustrous appearance, and conducts electricity and heat relatively well. These properties are all associated with having electrons available at the Fermi level, as against no ...

tends to become significant only for temperatures

Temperature is a physical quantity that quantitatively expresses the attribute of hotness or coldness. Temperature is measured with a thermometer. It reflects the average kinetic energy of the vibrating and colliding atoms making up a subst ...

over . Charge flow increases dramatically with temperature.

The term ''thermionic emission'' is now also used to refer to any thermally-excited charge emission process, even when the charge is emitted from one solid-state region into another.

History

Because theelectron

The electron (, or in nuclear reactions) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary charge, elementary electric charge. It is a fundamental particle that comprises the ordinary matter that makes up the universe, along with up qua ...

was not identified as a separate physical particle until the work of J. J. Thomson

Sir Joseph John Thomson (18 December 1856 – 30 August 1940) was an English physicist who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1906 "in recognition of the great merits of his theoretical and experimental investigations on the conduction of ...

in 1897, the word "electron" was not used when discussing experiments that took place before this date.

The phenomenon was initially reported in 1853 by Edmond Becquerel

Alexandre-Edmond Becquerel (; 24 March 1820 – 11 May 1891) was a French physicist who studied the solar spectrum, magnetism, electricity, and optics. In 1839, he discovered the photovoltaic effect, the operating principle of the solar cell, w ...

. It was observed again in 1873 by Frederick Guthrie Frederick Guthrie may refer to:

*Frederick Guthrie (scientist) (1833–1886), British physicist, chemist, and academic

* Frederick Guthrie (bass) (1924–2008), American operatic bass

*Frederick Bickell Guthrie

Frederick Bickell Guthrie (10 Decem ...

in Britain. While doing work on charged objects, Guthrie discovered that a red-hot iron sphere with a negative charge would lose its charge (by somehow discharging it into air). He also found that this did not happen if the sphere had a positive charge. Other early contributors included Johann Wilhelm Hittorf

Johann Wilhelm Hittorf (27 March 1824 – 28 November 1914) was a German physicist who was born in Bonn and died in Münster, Germany.

Hittorf was the first to compute the electricity-carrying capacity of charged atoms and molecules ( ions), ...

(1869–1883), Eugen Goldstein

Eugen Goldstein (; ; 5 September 1850 – 25 December 1930) was a German physicist. He was an early investigator of discharge tubes, and the discoverer of anode rays or canal rays, later identified as positive ions in the gas phase including th ...

(1885), and Julius Elster and Hans Friedrich Geitel (1882–1889).

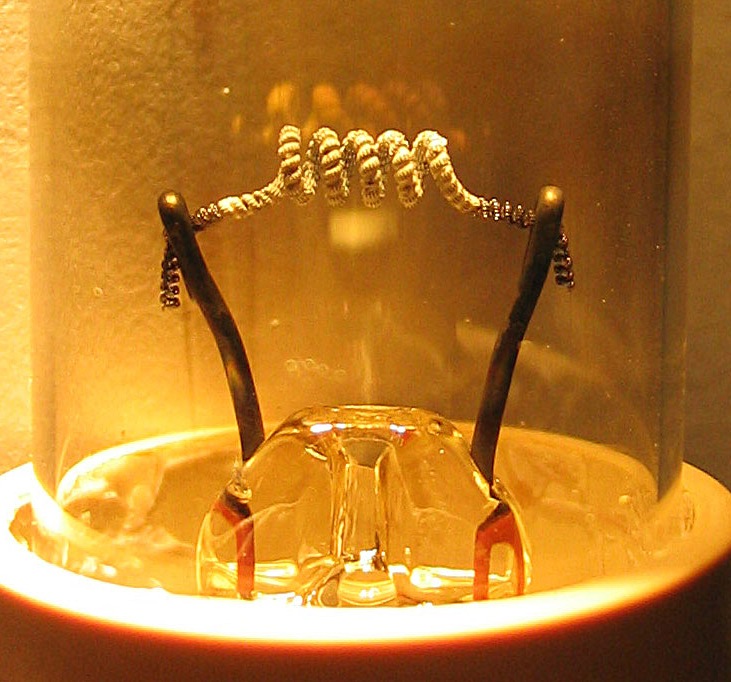

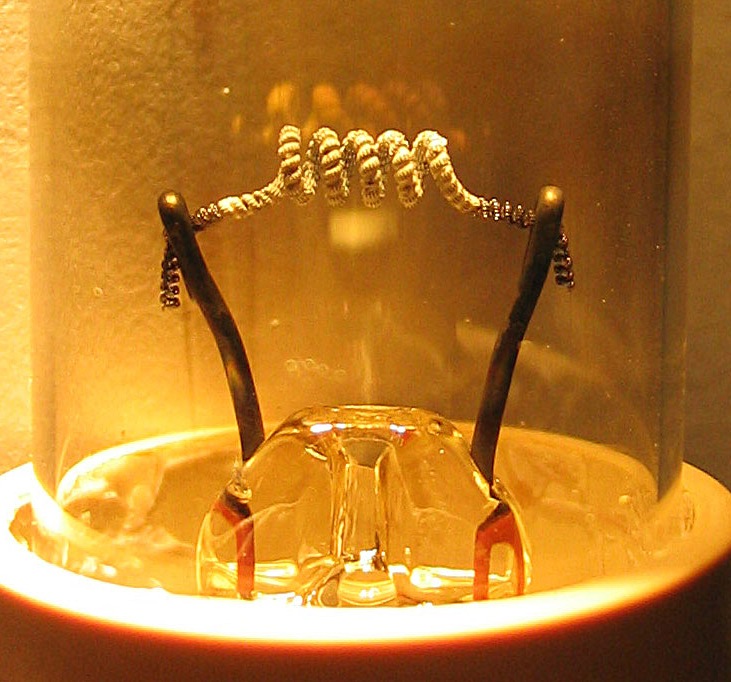

Edison effect

Thermionic emission was observed again byThomas Edison

Thomas Alva Edison (February11, 1847October18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices in fields such as electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and motion pictures. These inventions, ...

in 1880 while his team was trying to discover the reason for breakage of carbonized bamboo filaments and undesired blackening of the interior surface of the bulbs in his incandescent lamp

An incandescent light bulb, also known as an incandescent lamp or incandescent light globe, is an electric light that produces illumination by Joule heating a filament until it glows. The filament is enclosed in a glass bulb that is eith ...

s. This blackening was carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalence, tetravalent—meaning that its atoms are able to form up to four covalent bonds due to its valence shell exhibiting 4 ...

deposited from the filament and was darkest near the positive end of the filament loop, which ''apparently'' cast a light shadow on the glass, as if negatively-charged carbon emanated from the negative end and was attracted towards and sometimes absorbed by the positive end of the filament loop. This projected carbon was deemed "electrical carrying" and initially ascribed to an effect in Crookes tubes where negatively-charged cathode rays

Cathode rays are streams of electrons observed in vacuum tube, discharge tubes. If an evacuated glass tube is equipped with two electrodes and a voltage is applied, glass behind the positive electrode is observed to glow, due to electrons emitte ...

from ionized gas

Plasma () is a state of matter characterized by the presence of a significant portion of charged particles in any combination of ions or electrons. It is the most abundant form of ordinary matter in the universe, mostly in stars (including the ...

move from a negative to a positive electrode. To try to redirect the charged carbon particles to a separate electrode instead of the glass, Edison did a series of experiments (a first inconclusive one is in his notebook on 13 February 1880) such as the following successful one:

This effect had many applications. Edison found that the current emitted by the hot filament increased rapidly with voltage

Voltage, also known as (electrical) potential difference, electric pressure, or electric tension, is the difference in electric potential between two points. In a Electrostatics, static electric field, it corresponds to the Work (electrical), ...

, and filed a patent for a voltage-regulating device using the effect on 15 November 1883, notably the first US patent for an electronic device. He found that sufficient current would pass through the device to operate a telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

sounder, which was exhibited at the International Electrical Exhibition of 1884 in Philadelphia. Visiting British scientist William Preece

Sir William Henry Preece (15 February 1834 – 6 November 1913) was a Welsh electrical engineer and inventor. Preece relied on experiments and physical reasoning in his life's work. Upon his retirement from the Post Office in 1899, Preece was ...

received several bulbs from Edison to investigate. Preece's 1885 paper on them referred to the one-way current through the partial vacuum as the ''Edison effect,'' although that term is occasionally used to refer to thermionic emission itself. British physicist John Ambrose Fleming

Sir John Ambrose Fleming (29 November 1849 – 18 April 1945) was an English electrical engineer who invented the vacuum tube, designed the radio transmitter with which the first transatlantic radio transmission was made, and also established ...

, working for the British Wireless Telegraphy Company, discovered that the Edison effect could be used to detect radio waves

Radio waves (formerly called Hertzian waves) are a type of electromagnetic radiation with the lowest frequencies and the longest wavelengths in the electromagnetic spectrum, typically with frequencies below 300 gigahertz (GHz) and wavelengths ...

. Fleming went on to develop a two-element thermionic vacuum tube diode called the Fleming valve

The Fleming valve, also called the Fleming oscillation valve, was a thermionic valve or vacuum tube invented in 1904 by English physicist John Ambrose Fleming as a detector for early radio receivers used in electromagnetic wireless telegrap ...

(patented 16 November 1904). Thermionic diodes can also be configured to convert a heat difference to electric power directly without moving parts as a device called a thermionic converter

A thermionic converter consists of a hot electrode which thermionically emits electrons over a potential energy barrier to a cooler electrode, producing a useful electric power output. Caesium vapor is used to optimize the electrode work functi ...

, a type of heat engine

A heat engine is a system that transfers thermal energy to do mechanical or electrical work. While originally conceived in the context of mechanical energy, the concept of the heat engine has been applied to various other kinds of energy, pa ...

.

Richardson's law

Following J. J. Thomson's identification of the electron in 1897, the British physicistOwen Willans Richardson

Sir Owen Willans Richardson (26 April 1879 – 15 February 1959) was an English physicist who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1928 for his work on thermionic emission, which led to Richardson's law.

Biography

Richardson was born in Dew ...

began work on the topic that he later called "thermionic emission". He received a Nobel Prize in Physics

The Nobel Prize in Physics () is an annual award given by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences for those who have made the most outstanding contributions to mankind in the field of physics. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the ...

in 1928 "for his work on the thermionic phenomenon and especially for the discovery of the law named after him".

From band theory

In solid-state physics, the electronic band structure (or simply band structure) of a solid describes the range of energy levels that electrons may have within it, as well as the ranges of energy that they may not have (called ''band gaps'' or '' ...

, there are one or two electrons per atom

Atoms are the basic particles of the chemical elements. An atom consists of a atomic nucleus, nucleus of protons and generally neutrons, surrounded by an electromagnetically bound swarm of electrons. The chemical elements are distinguished fr ...

in a solid that are free to move from atom to atom. This is sometimes collectively referred to as a "sea of electrons". Their velocities follow a statistical distribution, rather than being uniform, and occasionally an electron will have enough velocity to exit the metal without being pulled back in. The minimum amount of energy needed for an electron to leave a surface is called the work function

In solid-state physics, the work function (sometimes spelled workfunction) is the minimum thermodynamic work (i.e., energy) needed to remove an electron from a solid to a point in the vacuum immediately outside the solid surface. Here "immediately" ...

. The work function is characteristic of the material and for most metals is on the order of several electronvolt

In physics, an electronvolt (symbol eV), also written electron-volt and electron volt, is the measure of an amount of kinetic energy gained by a single electron accelerating through an Voltage, electric potential difference of one volt in vacuum ...

s (eV). Thermionic currents can be increased by decreasing the work function. This often-desired goal can be achieved by applying various oxide coatings to the wire.

In 1901 Richardson published the results of his experiments: the current from a heated wire seemed to depend exponentially on the temperature of the wire with a mathematical form similar to the modified Arrhenius equation

In physical chemistry, the Arrhenius equation is a formula for the temperature dependence of reaction rates. The equation was proposed by Svante Arrhenius in 1889, based on the work of Dutch chemist Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff who had noted in 188 ...

, . Later, he proposed that the emission law should have the mathematical form

:

where ''J'' is the emission current density

In electromagnetism, current density is the amount of charge per unit time that flows through a unit area of a chosen cross section. The current density vector is defined as a vector whose magnitude is the electric current per cross-sectional ...

, ''T'' is the temperature of the metal, ''W'' is the work function

In solid-state physics, the work function (sometimes spelled workfunction) is the minimum thermodynamic work (i.e., energy) needed to remove an electron from a solid to a point in the vacuum immediately outside the solid surface. Here "immediately" ...

of the metal, ''k'' is the Boltzmann constant

The Boltzmann constant ( or ) is the proportionality factor that relates the average relative thermal energy of particles in a ideal gas, gas with the thermodynamic temperature of the gas. It occurs in the definitions of the kelvin (K) and the ...

, and ''A''G is a parameter discussed next.

In the period 1911 to 1930, as physical understanding of the behaviour of electrons in metals increased, various theoretical expressions (based on different physical assumptions) were put forward for ''A''G, by Richardson, Saul Dushman

Saul Dushman (July 12, 1883 – July 7, 1954) was a Russian-American physical chemist.

Dushman was born on July 12, 1883, in Rostov, Russia; he immigrated to the United States in 1891. He received a doctorate from the University of Toronto in ...

, Ralph H. Fowler

Sir Ralph Howard Fowler (17 January 1889 – 28 July 1944) was an English physicist, physical chemist, and astronomer.

Education

Ralph H. Fowler was born at Roydon, Essex, Roydon, Essex, on 17 January 1889 to Howard Fowler, from Burnham-on-Sea, ...

, Arnold Sommerfeld

Arnold Johannes Wilhelm Sommerfeld (; 5 December 1868 – 26 April 1951) was a German Theoretical physics, theoretical physicist who pioneered developments in Atomic physics, atomic and Quantum mechanics, quantum physics, and also educated and ...

and Lothar Wolfgang Nordheim

LotharHis name is sometimes misspelled as ''Lother''. Wolfgang Nordheim (November 7, 1899, Munich – October 5, 1985, La Jolla, California) was a German-born American theoretical physicist. He was a pioneer in the applications of quantum mech ...

. Over 60 years later, there is still no consensus among interested theoreticians as to the exact expression of ''A''G, but there is agreement that ''A''G must be written in the form:

:

where ''λ''R is a material-specific correction factor that is typically of order 0.5, and ''A''0 is a universal constant given by

:

where and are the mass and charge

Charge or charged may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''Charge, Zero Emissions/Maximum Speed'', a 2011 documentary

Music

* ''Charge'' (David Ford album)

* ''Charge'' (Machel Montano album)

* '' Charge!!'', an album by The Aqu ...

of an electron, respectively, and is the Planck constant

The Planck constant, or Planck's constant, denoted by h, is a fundamental physical constant of foundational importance in quantum mechanics: a photon's energy is equal to its frequency multiplied by the Planck constant, and the wavelength of a ...

.

In fact, by about 1930 there was agreement that, due to the wave-like nature of electrons, some proportion ''r''av of the outgoing electrons would be reflected as they reached the emitter surface, so the emission current density would be reduced, and ''λ''R would have the value . Thus, one sometimes sees the thermionic emission equation written in the form:

: .

However, a modern theoretical treatment by Modinos assumes that the band-structure of the emitting material must also be taken into account. This would introduce a second correction factor ''λ''B into ''λ''R, giving . Experimental values for the "generalized" coefficient ''A''G are generally of the order of magnitude of ''A''0, but do differ significantly as between different emitting materials, and can differ as between different crystallographic faces of the same material. At least qualitatively, these experimental differences can be explained as due to differences in the value of ''λ''R.

Considerable confusion exists in the literature of this area because: (1) many sources do not distinguish between ''A''G and ''A''0, but just use the symbol ''A'' (and sometimes the name "Richardson constant") indiscriminately; (2) equations with and without the correction factor here denoted by ''λ''R are both given the same name; and (3) a variety of names exist for these equations, including "Richardson equation", "Dushman's equation", "Richardson–Dushman equation" and "Richardson–Laue–Dushman equation". In the literature, the elementary equation is sometimes given in circumstances where the generalized equation would be more appropriate, and this in itself can cause confusion. To avoid misunderstandings, the meaning of any "A-like" symbol should always be explicitly defined in terms of the more fundamental quantities involved.

Because of the exponential function, the current increases rapidly with temperature when ''kT'' is less than ''W''. (For essentially every material, melting occurs well before .)

The thermionic emission law has been recently revised for 2D materials in various models.

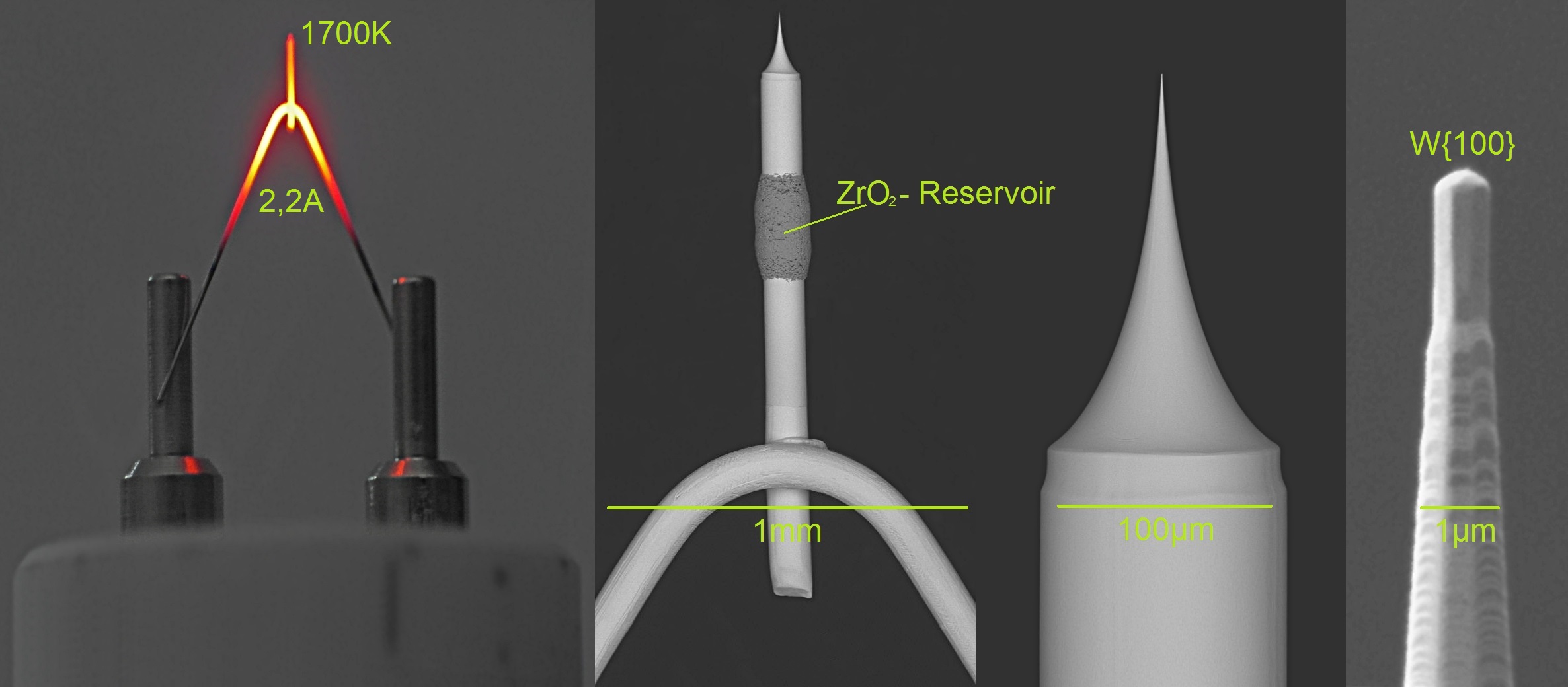

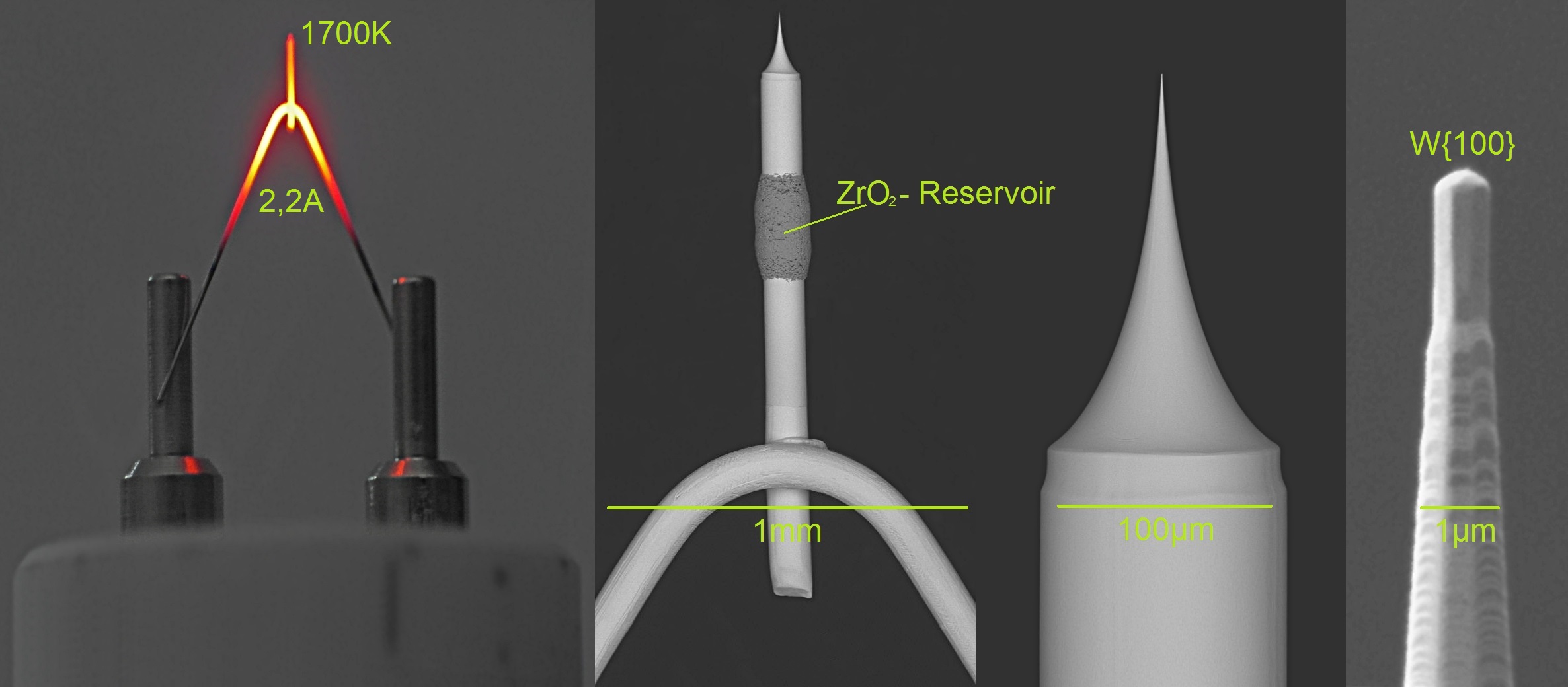

Schottky emission

In electron emission devices, especially

In electron emission devices, especially electron gun

file:Egun.jpg, Electron gun from a cathode-ray tube

file:Vidicon Electron Gun.jpg, The electron gun from an RCA Vidicon video camera tube

An electron gun (also called electron emitter) is an electrical component in some vacuum tubes that produc ...

s, the thermionic electron emitter will be biased negative relative to its surroundings. This creates an electric field of magnitude ''E'' at the emitter surface. Without the field, the surface barrier seen by an escaping Fermi-level electron has height ''W'' equal to the local work-function. The electric field lowers the surface barrier by an amount Δ''W'', and increases the emission current. This is known as the ''Schottky effect'' (named for Walter H. Schottky

Walter Hans Schottky ( ; ; 23 July 1886 – 4 March 1976) was a German solid-state physicist who played a major early role in developing the theory of electron and ion emission phenomena, invented the screen-grid vacuum tube in 1915 while wor ...

) or field enhanced thermionic emission. It can be modeled by a simple modification of the Richardson equation, by replacing ''W'' by (''W'' − Δ''W''). This gives the equation

:

:

where ''ε''0 is the electric constant (also called the vacuum permittivity

Vacuum permittivity, commonly denoted (pronounced "epsilon nought" or "epsilon zero"), is the value of the absolute dielectric permittivity of classical vacuum. It may also be referred to as the permittivity of free space, the electric const ...

).

Electron emission that takes place in the field-and-temperature-regime where this modified equation applies is often called Schottky emission. This equation is relatively accurate for electric field strengths lower than about . For electric field strengths higher than , so-called Fowler–Nordheim (FN) tunneling begins to contribute significant emission current. In this regime, the combined effects of field-enhanced thermionic and field emission can be modeled by the Murphy-Good equation for thermo-field (T-F) emission. At even higher fields, FN tunneling becomes the dominant electron emission mechanism, and the emitter operates in the so-called "cold field electron emission (CFE)" regime.

Thermionic emission can also be enhanced by interaction with other forms of excitation such as light. For example, excited Cesium

Caesium (IUPAC spelling; also spelled cesium in American English) is a chemical element; it has symbol Cs and atomic number 55. It is a soft, silvery-golden alkali metal with a melting point of , which makes it one of only five elemental metals ...

(Cs) vapors in thermionic converters form clusters of Cs- Rydberg matter which yield a decrease of collector emitting work function from 1.5 eV to 1.0–0.7 eV. Due to long-lived nature of Rydberg matter this low work function remains low which essentially increases the low-temperature converter's efficiency.

Photon-enhanced thermionic emission

Photon-enhanced thermionic emission (PETE) is a process developed by scientists atStanford University

Leland Stanford Junior University, commonly referred to as Stanford University, is a Private university, private research university in Stanford, California, United States. It was founded in 1885 by railroad magnate Leland Stanford (the eighth ...

that harnesses both the light and heat of the sun to generate electricity and increases the efficiency of solar power production by more than twice the current levels. The device developed for the process reaches peak efficiency above 200 °C, while most silicon solar cell

A solar cell, also known as a photovoltaic cell (PV cell), is an electronic device that converts the energy of light directly into electricity by means of the photovoltaic effect.

s become inert after reaching 100 °C. Such devices work best in parabolic dish

A parabolic (or paraboloid or paraboloidal) reflector (or dish or mirror) is a reflective surface used to collect or project energy such as light, sound, or radio waves. Its shape is part of a circular paraboloid, that is, the surface generated ...

collectors, which reach temperatures up to 800 °C. Although the team used a gallium nitride

Gallium nitride () is a binary III/ V direct bandgap semiconductor commonly used in blue light-emitting diodes since the 1990s. The compound is a very hard material that has a Wurtzite crystal structure. Its wide band gap of 3.4 eV af ...

semiconductor in its proof-of-concept device, it claims that the use of gallium arsenide

Gallium arsenide (GaAs) is a III-V direct band gap semiconductor with a Zincblende (crystal structure), zinc blende crystal structure.

Gallium arsenide is used in the manufacture of devices such as microwave frequency integrated circuits, monoli ...

can increase the device's efficiency to 55–60 percent, nearly triple that of existing systems, and 12–17 percent more than existing 43 percent multi-junction solar cells.

See also

*Space charge

Space charge is an interpretation of a collection of electric charges in which excess electric charge is treated as a continuum of charge distributed over a region of space (either a volume or an area) rather than distinct point-like charges. Thi ...

* Thermal ionization

Thermal ionization, also known as surface ionization or contact ionization, is a physical process whereby the atoms are desorption, desorbed from a hot surface, and in the process are ionized.

Thermal ionization is used to make simple ion sources ...

* Nottingham effect

References

External links

How vacuum tubes really work with a section on thermionic emission, with equations

john-a-harper.com.

Thermionic Phenomena and the Laws which Govern Them

Owen Richardson's Nobel lecture on thermionics. nobelprize.org. December 12, 1929. (PDF)

Derivations of thermionic emission equations from an undergraduate lab

, csbsju.edu. {{Authority control Atomic physics Electricity Energy conversion Vacuum tubes Thomas Edison