Samuel Taylor Coleridge on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet,

It was at Sockburn that Coleridge wrote his ballad-poem ''Love'', addressed to Sara Hutchinson. The knight mentioned is the mailed figure on the Conyers tomb in ruined Sockburn church. The figure has a wyvern at his feet, a reference to the Sockburn Worm slain by Sir John Conyers (and a possible source for Lewis Carroll's '' Jabberwocky'').

The worm was supposedly buried under the rock in the nearby pasture; this was the 'greystone' of Coleridge's first draft, later transformed into a 'mount'. The poem was a direct inspiration for John Keats' famous poem ''La Belle Dame Sans Merci''.

Coleridge's early intellectual debts, besides German idealists like Kant and critics like Lessing, were first to William Godwin's ''Political Justice'', especially during his Pantisocratic period, and to David Hartley's ''Observations on Man'', which is the source of the psychology which is found in ''Frost at Midnight''. Hartley argued that one becomes aware of sensory events as impressions, and that "ideas" are derived by noticing similarities and differences between impressions and then by naming them. Connections resulting from the coincidence of impressions create linkages, so that the occurrence of one impression triggers those links and calls up the memory of those ideas with which it is associated (See Dorothy Emmet, "Coleridge and Philosophy").

Coleridge was critical of the literary taste of his contemporaries, and a literary conservative insofar as he was afraid that the lack of taste in the ever growing masses of literate people would mean a continued desecration of literature itself.

In 1800, he returned to England and shortly thereafter settled with his family and friends in Greta Hall at Keswick in the Lake District of Cumberland to be near Grasmere, where Wordsworth had moved. He was a houseguest of the Wordsworths' for eighteen months, but was a difficult houseguest, as his dependency on laudanum grew and his frequent nightmares would wake the children. He was also a fussy eater, to Dorothy Wordsworth's frustration, who had to cook. For example, not content with salt, Coleridge sprinkled cayenne pepper on his eggs, which he ate from a teacup. His marital problems, nightmares, illnesses, increased opium dependency, tensions with Wordsworth, and a lack of confidence in his poetic powers fuelled the composition of ''Dejection: An Ode'' and an intensification of his philosophical studies.

In 1802, Coleridge took a nine-day walking holiday in the fells of the Lake District. Coleridge is credited with the first recorded descent of Scafell to Mickledore via Broad Stand, although this was more due to his getting lost than a keenness for mountaineering.

It was at Sockburn that Coleridge wrote his ballad-poem ''Love'', addressed to Sara Hutchinson. The knight mentioned is the mailed figure on the Conyers tomb in ruined Sockburn church. The figure has a wyvern at his feet, a reference to the Sockburn Worm slain by Sir John Conyers (and a possible source for Lewis Carroll's '' Jabberwocky'').

The worm was supposedly buried under the rock in the nearby pasture; this was the 'greystone' of Coleridge's first draft, later transformed into a 'mount'. The poem was a direct inspiration for John Keats' famous poem ''La Belle Dame Sans Merci''.

Coleridge's early intellectual debts, besides German idealists like Kant and critics like Lessing, were first to William Godwin's ''Political Justice'', especially during his Pantisocratic period, and to David Hartley's ''Observations on Man'', which is the source of the psychology which is found in ''Frost at Midnight''. Hartley argued that one becomes aware of sensory events as impressions, and that "ideas" are derived by noticing similarities and differences between impressions and then by naming them. Connections resulting from the coincidence of impressions create linkages, so that the occurrence of one impression triggers those links and calls up the memory of those ideas with which it is associated (See Dorothy Emmet, "Coleridge and Philosophy").

Coleridge was critical of the literary taste of his contemporaries, and a literary conservative insofar as he was afraid that the lack of taste in the ever growing masses of literate people would mean a continued desecration of literature itself.

In 1800, he returned to England and shortly thereafter settled with his family and friends in Greta Hall at Keswick in the Lake District of Cumberland to be near Grasmere, where Wordsworth had moved. He was a houseguest of the Wordsworths' for eighteen months, but was a difficult houseguest, as his dependency on laudanum grew and his frequent nightmares would wake the children. He was also a fussy eater, to Dorothy Wordsworth's frustration, who had to cook. For example, not content with salt, Coleridge sprinkled cayenne pepper on his eggs, which he ate from a teacup. His marital problems, nightmares, illnesses, increased opium dependency, tensions with Wordsworth, and a lack of confidence in his poetic powers fuelled the composition of ''Dejection: An Ode'' and an intensification of his philosophical studies.

In 1802, Coleridge took a nine-day walking holiday in the fells of the Lake District. Coleridge is credited with the first recorded descent of Scafell to Mickledore via Broad Stand, although this was more due to his getting lost than a keenness for mountaineering.

Between 1810 and 1820, Coleridge gave a series of lectures in London and

Between 1810 and 1820, Coleridge gave a series of lectures in London and

Coleridge is buried in the aisle of St. Michael's Parish Church in Highgate, London. He was originally buried at Old Highgate Chapel, next to the main entrance of Highgate School, but was re-interred in St. Michael's in 1961. Coleridge could see the red door of the then new church from his last residence across the green, where he lived with a doctor he had hoped might cure him (in a house owned until 2022 by Kate Moss). When it was discovered Coleridge's vault had become derelict, the coffins – Coleridge's and those of his wife, daughter, son-in-law, and grandson – were moved to St. Michael's after an international fundraising appeal.

Drew Clode, a member of St. Michael's stewardship committee states, "they put the coffins in a convenient space which was dry and secure, and quite suitable, bricked them up and forgot about them". A recent excavation revealed the coffins were not in the location most believed, the far corner of the crypt, but actually below a memorial slab in the nave inscribed with: "Beneath this stone lies the body of Samuel Taylor Coleridge".

St. Michael's plans to restore the crypt and allow public access. Says vicar Kunle Ayodeji of the plans: "...we hope that the whole crypt can be cleared as a space for meetings and other uses, which would also allow access to Coleridge’s cellar."

Coleridge is buried in the aisle of St. Michael's Parish Church in Highgate, London. He was originally buried at Old Highgate Chapel, next to the main entrance of Highgate School, but was re-interred in St. Michael's in 1961. Coleridge could see the red door of the then new church from his last residence across the green, where he lived with a doctor he had hoped might cure him (in a house owned until 2022 by Kate Moss). When it was discovered Coleridge's vault had become derelict, the coffins – Coleridge's and those of his wife, daughter, son-in-law, and grandson – were moved to St. Michael's after an international fundraising appeal.

Drew Clode, a member of St. Michael's stewardship committee states, "they put the coffins in a convenient space which was dry and secure, and quite suitable, bricked them up and forgot about them". A recent excavation revealed the coffins were not in the location most believed, the far corner of the crypt, but actually below a memorial slab in the nave inscribed with: "Beneath this stone lies the body of Samuel Taylor Coleridge".

St. Michael's plans to restore the crypt and allow public access. Says vicar Kunle Ayodeji of the plans: "...we hope that the whole crypt can be cleared as a space for meetings and other uses, which would also allow access to Coleridge’s cellar."

Coleridge is arguably best known for his longer poems, particularly '' The Rime of the Ancient Mariner'' and '' Christabel''. Even those who have never read the ''Rime'' have come under its influence: its words have given the English language the

Coleridge is arguably best known for his longer poems, particularly '' The Rime of the Ancient Mariner'' and '' Christabel''. Even those who have never read the ''Rime'' have come under its influence: its words have given the English language the

The last ten lines of ''Frost at Midnight'' were chosen by Harper as the "best example of the peculiar kind of blank verse Coleridge had evolved, as natural-seeming as prose, but as exquisitely artistic as the most complicated sonnet." The speaker of the poem is addressing his infant son, asleep by his side:

The last ten lines of ''Frost at Midnight'' were chosen by Harper as the "best example of the peculiar kind of blank verse Coleridge had evolved, as natural-seeming as prose, but as exquisitely artistic as the most complicated sonnet." The speaker of the poem is addressing his infant son, asleep by his side:

Coleridge wrote reviews of Ann Radcliffe's books and ''The Mad Monk'', among others. He comments in his reviews: "Situations of torment, and images of naked horror, are easily conceived; and a writer in whose works they abound, deserves our gratitude almost equally with him who should drag us by way of sport through a military hospital, or force us to sit at the dissecting-table of a natural philosopher. To trace the nice boundaries, beyond which terror and sympathy are deserted by the pleasurable emotions, – to reach those limits, yet never to pass them, hic labor, hic opus est." and "The horrible and the preternatural have usually seized on the popular taste, at the rise and decline of literature. Most powerful stimulants, they can never be required except by the torpor of an unawakened, or the languor of an exhausted, appetite... We trust, however, that satiety will banish what good sense should have prevented; and that, wearied with fiends, incomprehensible characters, with shrieks, murders, and subterraneous dungeons, the public will learn, by the multitude of the manufacturers, with how little expense of thought or imagination this species of composition is manufactured."

However, Coleridge used these elements in poems such as ''The Rime of the Ancient Mariner'' (1798), ''Christabel'' and ''Kubla Khan'' (published in 1816, but known in manuscript form before then) and certainly influenced other poets and writers of the time. Poems like these both drew inspiration from and helped to inflame the craze for

Coleridge wrote reviews of Ann Radcliffe's books and ''The Mad Monk'', among others. He comments in his reviews: "Situations of torment, and images of naked horror, are easily conceived; and a writer in whose works they abound, deserves our gratitude almost equally with him who should drag us by way of sport through a military hospital, or force us to sit at the dissecting-table of a natural philosopher. To trace the nice boundaries, beyond which terror and sympathy are deserted by the pleasurable emotions, – to reach those limits, yet never to pass them, hic labor, hic opus est." and "The horrible and the preternatural have usually seized on the popular taste, at the rise and decline of literature. Most powerful stimulants, they can never be required except by the torpor of an unawakened, or the languor of an exhausted, appetite... We trust, however, that satiety will banish what good sense should have prevented; and that, wearied with fiends, incomprehensible characters, with shrieks, murders, and subterraneous dungeons, the public will learn, by the multitude of the manufacturers, with how little expense of thought or imagination this species of composition is manufactured."

However, Coleridge used these elements in poems such as ''The Rime of the Ancient Mariner'' (1798), ''Christabel'' and ''Kubla Khan'' (published in 1816, but known in manuscript form before then) and certainly influenced other poets and writers of the time. Poems like these both drew inspiration from and helped to inflame the craze for

On the Constitution of the Church and State

' (1976); # ''Shorter Works and Fragments'' (1995) in 2 vols; # ''Marginalia'' (1980 and following) in 6 vols; # ''Logic'' (1981); # ''Table Talk'' (1990) in 2 vols; # ''Opus Maximum'' (2002); # ''Poetical Works'' (2001) in 6 vols (part 1 – Reading Edition in 2 vols; part 2 – Variorum Text in 2 vols; part 3 – Plays in 2 vols). In addition, Coleridge's letters are available in: ''The Collected Letters of Samuel Taylor Coleridge'' (1956–71), ed. Earl Leslie Griggs, 6 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon Press).

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

ISBN 9781604138092. *Boulger, J.D. ''Twentieth Century Interpretations of The Rime of the Ancient Mariner'' (Englewood Cliffs NJ: Prentice Hall, 1969). (Contains twentieth century readings of the 'Rime', including Robert Penn Warren, Humphrey House.) *Cheyne, Peter. ''Coleridge's Contemplative Philosophy'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020). *Class, Monika. ''Coleridge and the Kantian Ideas in England, 1796–1817'' (London: Bloomsbury, 2012). * Cutsinger, James S. ''The Form of Transformed Vision'' (Macon GA: Mercer, 1987). (Argues that Coleridge wants to transform his reader's consciousness, to see nature as a living presence.) * *Engell, James. ''The Creative Imagination'' (Cambridge: Harvard, 1981). (Surveys the various German theories of imagination in the eighteenth century) *Fruman, Norman. ''Coleridge the Damaged Archangel'' (London: George Allen and Unwin). (Examines Coleridge's plagiarisms, taking a critical view) * * *Hough, Barry, and Davis, Howard. ''Coleridge's Laws: A Study of Coleridge in Malta'' (Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2010). . * * (Detailed, recent discussion of the Conversation Poems.) *Leadbetter, Gregory. ''Coleridge and the Daemonic Imagination'' (Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011). * Lowes, John Livingston. ''The Road to Xanadu'' (London: Constable, 1930). (Examines sources for Coleridge's poetry). * *Magnuson, Paul. ''Coleridge and Wordsworth: A Lyrical Dialogue'' (Princeton: Princeton UP, 1988). (A 'dialogical' reading of Coleridge and Wordsworth.) * McFarland, Thomas. ''Coleridge and the Pantheist Tradition'' (Oxford: OUP, 1969). (Examines the influence of German philosophy on Coleridge, with particular reference to pantheism) *Modiano, Raimonda. ''Coleridge and the Concept of Nature'' (London: Macmillan, 1985). (Examines the influence of German philosophy on Coleridge, with particular reference to nature) * * Muirhead, John H. ''Coleridge as Philosopher'' (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1930). (Examines Coleridge's philosophical texts) *Murray, Chris. ''Tragic Coleridge'' (Farnham: Ashgate, 2013

link

*Parker, Reeve, ''Romantic Tragedies'' (Cambridge: CUP, 2011). *Perkins, Mary Anne. ''Coleridge's Philosophy: The Logos as Unifying Principle'' (Oxford: OUP, 1994). (Draws the various strands of Coleridge's theology and philosophy together under the concept of the 'Logos'.) *Perry, Seamus. ''Coleridge and the Uses of Division'' (Oxford: OUP, 1999). (Brings out the play of language in Coleridge's Notebooks.) * *Riem, Natale Antonella. ''The One Life. Coleridge and Hinduism'' (Jaipur-New Delhi: Rawat, 2005). *Reid, Nicholas. ''Coleridge, Form and Symbol: Or the Ascertaining Vision'' (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006). (Argues for the importance of Schelling as a source for Coleridge's philosophical texts). * Richards, I. A. ''Coleridge on Imagination'' (London: Kegan Paul, 1934). (Examines Coleridge's concept of the imagination) *Richardson, Alan. ''British Romanticism and the Science of the Mind'' (Cambridge: CUP, 2001). (Examines the sources for Coleridge's interest in psychology.) * Shaffer, Elinor S. ''Kubla Khan and the Fall of Jerusalem'' (Cambridge: CUP, 1975). (A broadly structuralist reading of Coleridge's poetical sources.) *Stockitt, Robin. ''Imagination and the Playfulness of God: The Theological Implications of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Definition of the Human Imagination'' (Eugene, OR, 2011) (Distinguished Dissertations in Christian Theology). *Toor, Kiran. ''Coleridge's Chrysopoetics: Alchemy, Authorship and Imagination'' (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars, 2011). *Vallins, David. ''Coleridge and the Psychology of Romanticism: Feeling and Thought'' (London: Macmillan, 2000). (Examines Coleridge's psychology.) *Wheeler, K.M. ''Sources, Processes and Methods in Coleridge’s Biographia Literaria'' (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1980). (Examines the idea of the active reader in Coleridge.) *Woudenberg, Maximiliaan van. ''Coleridge and Cosmopolitan Intellectualism 1794–1804. The Legacy of Göttingen University'' (London: Routledge, 2018). *Wright, Luke S. H., ''Samuel Taylor Coleridge and the Anglican Church'' (Notre Dame: Notre Dame University Press, 2010). *

Poems by Coleridge

from the Poetry Foundation. Retrieved 19 October 2010

Works of Coleridge

at the University of Toronto. Retrieved 19 October 2010

Friends of Coleridge Society

Retrieved 19 October 2010

The re-opening of Coleridge Cottage near Exmoor

by Martin Hesp at Western Morning Press *

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

at the British Library

Coleridge archive at the Victoria University

Retrieved 19 October 2010 * Letters of Samuel Taylor Coleridge from the Internet Archive. Retrieved 19 October 2010 * Samuel Taylor Coleridge Collection. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. {{DEFAULTSORT:Coleridge, Samuel Taylor 1772 births 1834 deaths 18th-century English Christian theologians 18th-century English dramatists and playwrights 18th-century English non-fiction writers 18th-century English philosophers 18th-century English poets 18th-century philosophers 18th-century poets 18th-century theologians 19th-century English Christian theologians 19th-century English dramatists and playwrights 19th-century English non-fiction writers 19th-century English philosophers 19th-century English poets 19th-century philosophers 19th-century poets 19th-century theologians Alumni of Jesus College, Cambridge British cultural critics British social commentators Samuel Taylor English Anglican theologians English Anglicans English autobiographers English literary critics English male dramatists and playwrights English male non-fiction writers English male poets English social commentators English theologians Fellows of the Royal Society of Literature Irvingites Literacy and society theorists Literary critics of English Literary theorists Nontrinitarian Christians People educated at Christ's Hospital People from Keswick, Cumbria People from Ottery St Mary Philosophers of art Philosophers of culture Philosophers of language Philosophers of literature Philosophers of religion Philosophers of social science Political philosophers Romantic poets Social critics Social philosophers Spinozists Writers about activism and social change Writers of Gothic fiction

literary critic

Literary criticism (or literary studies) is the study, evaluation, and interpretation of literature. Modern literary criticism is often influenced by literary theory, which is the philosophical discussion of literature's goals and methods. Th ...

, philosopher, and theologian

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing th ...

who, with his friend William Wordsworth, was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lake Poets. He also shared volumes and collaborated with Charles Lamb, Robert Southey, and Charles Lloyd. He wrote the poems '' The Rime of the Ancient Mariner'' and '' Kubla Khan'', as well as the major prose work ''Biographia Literaria

The ''Biographia Literaria'' is a critical autobiography by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, published in 1817 in two volumes. Its working title was 'Autobiographia Literaria'. The formative influences on the work were Wordsworth's theory of poetry, th ...

''. His critical work, especially on William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

, was highly influential, and he helped introduce German idealist philosophy to English-speaking cultures. Coleridge coined many familiar words and phrases, including "suspension of disbelief

Suspension of disbelief, sometimes called willing suspension of disbelief, is the avoidance of critical thinking or logic in examining something unreal or impossible in reality, such as a work of speculative fiction, in order to believe it for ...

". He had a major influence on Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, abolitionist, and poet who led the transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a cham ...

and American transcendentalism

Transcendentalism is a philosophical movement that developed in the late 1820s and 1830s in New England. "Transcendentalism is an American literary, political, and philosophical movement of the early nineteenth century, centered around Ralph Wald ...

.

Throughout his adult life, Coleridge had crippling bouts of anxiety

Anxiety is an emotion which is characterized by an unpleasant state of inner turmoil

Turmoil may refer to:

* ''Turmoil'' (1984 video game), a 1984 video game released by Bug-Byte

* ''Turmoil'' (2016 video game), a 2016 indie oil tycoon video ...

and depression; it has been speculated that he had bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder, previously known as manic depression, is a mental disorder characterized by periods of depression and periods of abnormally elevated mood that last from days to weeks each. If the elevated mood is severe or associated with ...

, which had not been defined during his lifetime.Jamison, Kay Redfield. ''Touched with Fire: Manic-Depressive Illness and the Artistic Temperament''. Free Press (1994), 219–224. He was physically unhealthy, which may have stemmed from a bout of rheumatic fever

Rheumatic fever (RF) is an inflammation#Disorders, inflammatory disease that can involve the heart, joints, skin, and brain. The disease typically develops two to four weeks after a Streptococcal pharyngitis, streptococcal throat infection. Sign ...

and other childhood illnesses. He was treated for these conditions with laudanum, which fostered a lifelong opium

Opium (or poppy tears, scientific name: ''Lachryma papaveris'') is dried latex obtained from the seed capsules of the opium poppy '' Papaver somniferum''. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid morphine, which ...

addiction.

Early life and education

Coleridge was born on 21 October 1772 in the town of Ottery St Mary in Devon, England. Samuel's father was the Reverend John Coleridge (1718–1781), the well-respectedvicar

A vicar (; Latin: '' vicarius'') is a representative, deputy or substitute; anyone acting "in the person of" or agent for a superior (compare "vicarious" in the sense of "at second hand"). Linguistically, ''vicar'' is cognate with the English pr ...

of St Mary's Church, Ottery St Mary and was headmaster of the King's School, a free grammar school established by King Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disagr ...

(1509–1547) in the town. He had previously been master of Hugh Squier's School in South Molton, Devon, and lecturer of nearby Molland.

John Coleridge had three children by his first wife. Samuel was the youngest of ten by the Reverend Mr. Coleridge's second wife, Anne Bowden (1726–1809), probably the daughter of John Bowden, Mayor of South Molton

The Mayor of South Molton in Devon is an ancient historical office which survives at the present time. In the Middle Ages the town of South Molton was Corporation, incorporated by royal charter into a borough governed by a Mayor and Corporation. ...

, Devon, in 1726. Coleridge suggests that he "took no pleasure in boyish sports" but instead read "incessantly" and played by himself.Coleridge, Samuel Taylor, Joseph Noel Paton, Katharine Lee Bates.''Coleridge's Ancient Mariner'' Ed Katharine Lee Bates. Shewell, & Sanborn (1889) p. 2

After John Coleridge died in 1781, 8-year-old Samuel was sent to Christ's Hospital, a charity school which was founded in the 16th century in Greyfriars Greyfriars, Grayfriars or Gray Friars is a term for Franciscan Order of Friars Minor, in particular, the Conventual Franciscans. The term often refers to buildings or districts formerly associated with the order.

Former Friaries

* Greyfriars, Be ...

, London, where he remained throughout his childhood, studying and writing poetry. At that school Coleridge became friends with Charles Lamb, a schoolmate, and studied the works of Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: t ...

and William Lisle Bowles.Morley, Henry. ''Table Talk of Samuel Taylor Coleridge and The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, Christabel, &c.'' New York: Routledge (1884) pp. i-iv

In one of a series of autobiographical letters written to Thomas Poole, Coleridge wrote: "At six years old I remember to have read ''Belisarius'', ''Robinson Crusoe

''Robinson Crusoe'' () is a novel by Daniel Defoe, first published on 25 April 1719. The first edition credited the work's protagonist Robinson Crusoe as its author, leading many readers to believe he was a real person and the book a tr ...

'', and ''Philip Quarll'' – and then I found the ''Arabian Nights' Entertainments'' – one tale of which (the tale of a man who was compelled to seek for a pure virgin) made so deep an impression on me (I had read it in the evening while my mother was mending stockings) that I was haunted by spectres whenever I was in the dark – and I distinctly remember the anxious and fearful eagerness with which I used to watch the window in which the books lay – and whenever the sun lay upon them, I would seize it, carry it by the wall, and bask, and read."

Coleridge seems to have appreciated his teacher, as he wrote in recollections of his school days in ''Biographia Literaria'': I enjoyed the inestimable advantage of a very sensible, though at the same time, a very severe master ..At the same time that we were studying the Greek Tragic Poets, he made us readHe later wrote of his loneliness at school in the poem '' Frost at Midnight'': "With unclosed lids, already had I dreamt/Of my sweet birthplace." From 1791 until 1794, Coleridge attendedShakespeare William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...and Milton as lessons: and they were the lessons too, which required most time and trouble to bring up, so as to escape his censure. I learnt from him, that Poetry, even that of the loftiest, and, seemingly, that of the wildest odes, had a logic of its own, as severe as that of science; and more difficult, because more subtle, more complex, and dependent on more, and more fugitive causes. ..In our own English compositions (at least for the last three years of our school education) he showed no mercy to phrase, metaphor, or image, unsupported by a sound sense, or where the same sense might have been conveyed with equal force and dignity in plainer words... In fancy I can almost hear him now, exclaiming ''Harp? Harp? Lyre? Pen and ink, boy, you mean! Muse, boy, Muse? your Nurse's daughter, you mean! Pierian spring? Oh aye! the cloister-pump, I suppose!'' ..Be this as it may, there was one custom of our master's, which I cannot pass over in silence, because I think it ... worthy of imitation. He would often permit our theme exercises, ... to accumulate, till each lad had four or five to be looked over. Then placing the whole number abreast on his desk, he would ask the writer, why this or that sentence might not have found as appropriate a place under this or that other thesis: and if no satisfying answer could be returned, and two faults of the same kind were found in one exercise, the irrevocable verdict followed, the exercise was torn up, and another on the same subject to be produced, in addition to the tasks of the day.

Jesus College, Cambridge

Jesus College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college's full name is The College of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Saint John the Evangelist and the glorious Virgin Saint Radegund, near Cambridge. Its common name comes f ...

. In 1792, he won the Browne Gold Medal for an ode that he wrote attacking the slave trade.

In December 1793, he left the college and enlisted in the 15th (The King's) Light Dragoons using the false name "Silas Tomkyn Comberbache", perhaps because of debt or because the girl that he loved, Mary Evans

Mary Evans (1770–1843), later Mary Todd, is notable as the first love of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and although he failed to profess his feelings to Evans during their early relationship, he held her in affection until 1794 when Evans dissuaded ...

, had rejected him. His brothers arranged for his discharge a few months later under the reason of "insanity" and he was readmitted to Jesus College, though he would never receive a degree from the university.

Pantisocracy and marriage

Cambridge and Somerset

At Jesus College, Coleridge was introduced to political and theological ideas then considered radical, including those of the poet Robert Southey with whom he collaborated on the play '' The Fall of Robespierre''. Coleridge joined Southey in a plan, later abandoned, to found autopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imaginary community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book '' Utopia'', describing a fictional island socie ...

n commune-like society, called Pantisocracy, in the wilderness of Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; (Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, Ma ...

. In 1795, the two friends married sisters Sara and Edith Fricker, in St Mary Redcliffe, Bristol, but Coleridge's marriage with Sara proved unhappy. He grew to detest his wife, whom he married mainly because of social constraints. Following the birth of their fourth child, he eventually separated from her.

A third sister, Mary, had already married a third poet, Robert Lovell, and both became partners in Pantisocracy. Lovell also introduced Coleridge and Southey to their future patron Joseph Cottle

Joseph Cottle (1770–1853) was an English publisher and author.

Cottle started business in Bristol. He published the works of Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Robert Southey on generous terms. He then wrote in his ''Early Recollections'' an expos ...

, but died of a fever in April 1796. Coleridge was with him at his death.

In 1796 he released his first volume of poems entitled ''Poems on Various Subjects

''Poems on Various Subjects'' (1796) was the first collection by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, including also a few sonnets by Charles Lamb. A second edition in 1797 added many more poems by Lamb and by Charles Lloyd, and a third edition appeared i ...

'', which also included four poems by Charles Lamb as well as a collaboration with Robert Southey and a work suggested by his and Lamb's schoolfriend Robert Favell. Among the poems were ''Religious Musings

''Religious Musings'' was composed by Samuel Taylor Coleridge in 1794 and finished by 1796. It is one of his first poems of critical merit and contains many of his early feelings about religion and politics.

Background

While staying in London ove ...

'', ''Monody on the Death of Chatterton

"Monody on the Death of Chatterton" was composed by Samuel Taylor Coleridge in 1790 and was rewritten throughout his lifetime. The poem deals with the idea of Thomas Chatterton, a poet who committed suicide, as representing the poetic struggle.

B ...

'' and an early version of ''The Eolian Harp

''The Eolian Harp'' is a poem written by Samuel Taylor Coleridge in 1795 and published in his 1796 poetry collection. It is one of the early conversation poems and discusses Coleridge's anticipation of a marriage with Sara Fricker along with the ...

'' entitled ''Effusion 35''. A second edition was printed in 1797, this time including an appendix of works by Lamb and Charles Lloyd, a young poet to whom Coleridge had become a private tutor.

In 1796 he also privately printed ''Sonnets from Various Authors'', including sonnets by Lamb, Lloyd, Southey and himself as well as older poets such as William Lisle Bowles.

Coleridge made plans to establish a journal, ''The Watchman

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things that are already or about to be mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in En ...

'', to be printed every eight days to avoid a weekly newspaper tax. The first issue of the short-lived journal was published in March 1796. It had ceased publication by May of that year.

The years 1797 and 1798, during which he lived in what is now known as Coleridge Cottage, in Nether Stowey

Nether Stowey is a large village in the Sedgemoor district of Somerset, South West England. It sits in the foothills of the Quantock Hills (England's first Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty), just below Over Stowey. The parish of Nether Stowey c ...

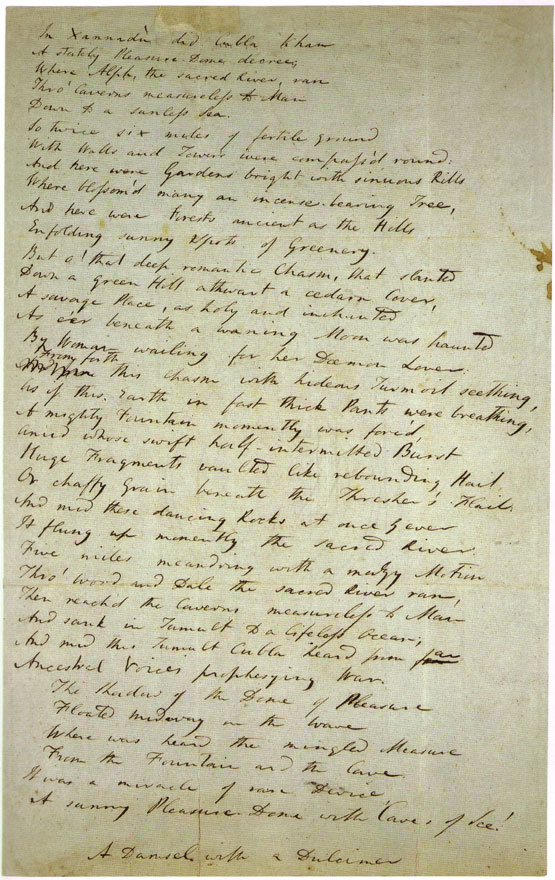

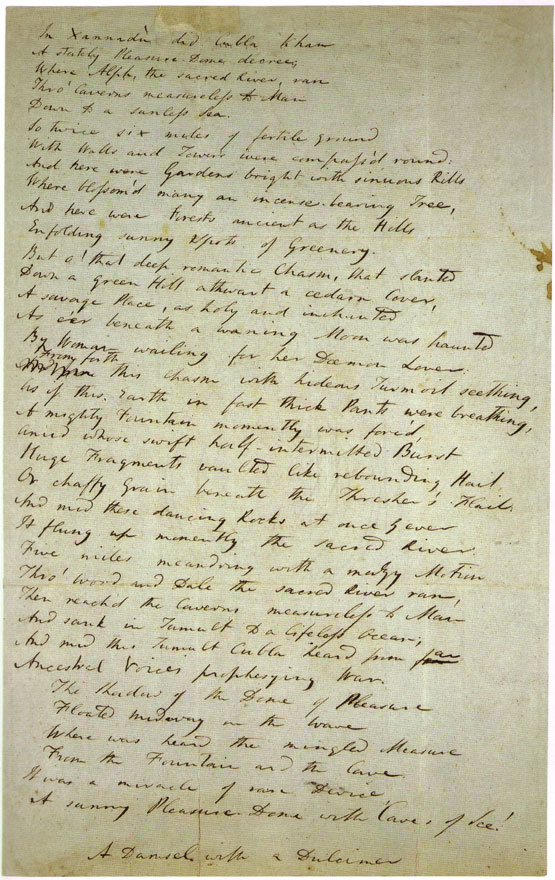

, Somerset, were among the most fruitful of Coleridge's life. In 1795, Coleridge met poet William Wordsworth and his sister Dorothy. (Wordsworth, having visited him and being enchanted by the surroundings, rented Alfoxton Park, a little over three miles kmaway.) Besides '' The Rime of the Ancient Mariner'', Coleridge composed the symbolic poem '' Kubla Khan'', written—Coleridge himself claimed—as a result of an opium dream, in "a kind of a reverie"; and the first part of the narrative poem ''Christabel''. The writing of ''Kubla Khan'', written about the Mongol

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal member ...

emperor Kublai Khan and his legendary palace at Xanadu

Xanadu may refer to:

* Shangdu, the ancient summer capital of Kublai Khan's empire in China

* a metaphor for opulence or an idyllic place, based upon Coleridge's description of Shangdu in his poem ''Kubla Khan''

Other places

* Xanadu (Titan), ...

, was said to have been interrupted by the arrival of a " Person from Porlock" – an event that has been embellished upon in such varied contexts as science fiction and Nabokov's ''Lolita

''Lolita'' is a 1955 novel written by Russian-American novelist Vladimir Nabokov. The novel is notable for its controversial subject: the protagonist and unreliable narrator, a middle-aged literature professor under the pseudonym Humbert Hum ...

''. During this period, he also produced his much-praised "conversation poems

The conversation poems are a group of at least eight poems composed by Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772–1834) between 1795 and 1807. Each details a particular life experience which led to the poet's examination of nature and the role of poetry. T ...

" ''This Lime-Tree Bower My Prison

"This Lime-Tree Bower My Prison" is a poem written by Samuel Taylor Coleridge during 1797. The poem discusses a time in which Coleridge was forced to stay beneath a lime tree while his friends were able to enjoy the countryside. Within the poem, C ...

'', '' Frost at Midnight'', and ''The Nightingale

The common nightingale is a songbird found in Eurasia.

Nightingale may also refer to:

Birds

* Thrush nightingale, a songbird found in Eurasia

* Red-billed leiothrix, a songbird of the Indian Subcontinent

Literature

* "Nightingale" (short sto ...

''.

In 1798, Coleridge and Wordsworth published a joint volume of poetry, ''Lyrical Ballads

''Lyrical Ballads, with a Few Other Poems'' is a collection of poems by William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, first published in 1798 and generally considered to have marked the beginning of the English Romantic movement in litera ...

'', which proved to be the starting point for the English romantic age. Wordsworth may have contributed more poems, but the real star of the collection was Coleridge's first version of ''The Rime of the Ancient Mariner''. It was the longest work and drew more praise and attention than anything else in the volume. In the spring Coleridge temporarily took over for Rev. Joshua Toulmin at Taunton's Mary Street Unitarian Chapel while Rev. Toulmin grieved over the drowning death of his daughter Jane. Poetically commenting on Toulmin's strength, Coleridge wrote in a 1798 letter to John Prior Estlin, "I walked into Taunton (eleven miles) and back again, and performed the divine services for Dr. Toulmin. I suppose you must have heard that his daughter, (Jane, on 15 April 1798) in a melancholy derangement, suffered herself to be swallowed up by the tide on the sea-coast between Sidmouth

Sidmouth () is a town on the English Channel in Devon, South West England, southeast of Exeter. With a population of 12,569 in 2011, it is a tourist resort and a gateway to the Jurassic Coast World Heritage Site. A large part of the town ...

and Bere (Beer

Beer is one of the oldest and the most widely consumed type of alcoholic drink in the world, and the third most popular drink overall after water and tea. It is produced by the brewing and fermentation of starches, mainly derived from cer ...

). These events cut cruelly into the hearts of old men: but the good Dr. Toulmin bears it like the true practical Christian, – there is indeed a tear in his eye, but that eye is lifted up to the Heavenly Father

God the Father is a title given to God in Christianity. In mainstream trinitarian Christianity, God the Father is regarded as the first person of the Trinity, followed by the second person, God the Son Jesus Christ, and the third person, God t ...

."

The West Midlands and the North

Coleridge also worked briefly inShropshire

Shropshire (; alternatively Salop; abbreviated in print only as Shrops; demonym Salopian ) is a landlocked historic county in the West Midlands region of England. It is bordered by Wales to the west and the English counties of Cheshire to ...

, where he came in December 1797 as locum to its local Unitarian minister, Dr Rowe, in their church in the High Street at Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury ( , also ) is a market town, civil parish, and the county town of Shropshire, England, on the River Severn, north-west of London; at the 2021 census, it had a population of 76,782. The town's name can be pronounced as either 'S ...

. He is said to have read his ''Rime of the Ancient Mariner'' at a literary evening in Mardol. He was then contemplating a career in the ministry, and gave a probationary sermon in High Street church on Sunday, 14 January 1798. William Hazlitt, a Unitarian minister's son, was in the congregation, having walked from Wem

Wem may refer to:

* HMS ''Wem'' (1919), a minesweeper of the Royal Navy during World War I

*Weem, a village in Perthshire, Scotland

* Wem, a small town in Shropshire, England

*Wem (musician), hip hop musician

WEM may stand for:

* County Westmeath, ...

to hear him. Coleridge later visited Hazlitt and his father

His or HIS may refer to:

Computing

* Hightech Information System, a Hong Kong graphics card company

* Honeywell Information Systems

* Hybrid intelligent system

* Microsoft Host Integration Server

Education

* Hangzhou International School, in ...

at Wem but within a day or two of preaching he received a letter from Josiah Wedgwood II

Josiah Wedgwood II (3 April 1769 – 12 July 1843), the son of the English potter Josiah Wedgwood, continued his father's firm and was a Member of Parliament (MP) for Stoke-upon-Trent from 1832 to 1835. He was an abolitionist, and detested ...

, who had offered to help him out of financial difficulties with an annuity of £150 (approximately £13,000 in today's money) per year on condition he give up his ministerial career. Coleridge accepted this, to the disappointment of Hazlitt who hoped to have him as a neighbour in Shropshire.

From 16 September 1798, Coleridge and the Wordsworths left for a stay in Germany; Coleridge soon went his own way and spent much of his time in university towns. In February 1799 he enrolled at the University of Göttingen

The University of Göttingen, officially the Georg August University of Göttingen, (german: Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, known informally as Georgia Augusta) is a public research university in the city of Göttingen, Germany. Founded i ...

, where he attended lectures by Johann Friedrich Blumenbach and Johann Gottfried Eichhorn. During this period, he became interested in German philosophy, especially the transcendental idealism and critical philosophy

The critical philosophy (german: kritische Philosophie) movement, attributed to Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), sees the primary task of philosophy as criticism rather than justification of knowledge. Criticism, for Kant, meant judging as to the p ...

of Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and aes ...

, and in the literary criticism of the 18th-century dramatist Gotthold Lessing. Coleridge studied German and, after his return to England, translated the dramatic trilogy ''Wallenstein'' by the German Classical poet Friedrich Schiller into English. He continued to pioneer these ideas through his own critical writings for the rest of his life (sometimes without attribution), although they were unfamiliar and difficult for a culture dominated by empiricism.

In 1799, Coleridge and the Wordsworths stayed at Thomas Hutchinson's farm on the River Tees

The River Tees (), in Northern England, rises on the eastern slope of Cross Fell in the North Pennines and flows eastwards for to reach the North Sea between Hartlepool and Redcar near Middlesbrough. The modern day history of the river has bee ...

at Sockburn, near Darlington

Darlington is a market town in the Borough of Darlington, County Durham, England. The River Skerne flows through the town; it is a tributary of the River Tees. The Tees itself flows south of the town.

In the 19th century, Darlington under ...

.

It was at Sockburn that Coleridge wrote his ballad-poem ''Love'', addressed to Sara Hutchinson. The knight mentioned is the mailed figure on the Conyers tomb in ruined Sockburn church. The figure has a wyvern at his feet, a reference to the Sockburn Worm slain by Sir John Conyers (and a possible source for Lewis Carroll's '' Jabberwocky'').

The worm was supposedly buried under the rock in the nearby pasture; this was the 'greystone' of Coleridge's first draft, later transformed into a 'mount'. The poem was a direct inspiration for John Keats' famous poem ''La Belle Dame Sans Merci''.

Coleridge's early intellectual debts, besides German idealists like Kant and critics like Lessing, were first to William Godwin's ''Political Justice'', especially during his Pantisocratic period, and to David Hartley's ''Observations on Man'', which is the source of the psychology which is found in ''Frost at Midnight''. Hartley argued that one becomes aware of sensory events as impressions, and that "ideas" are derived by noticing similarities and differences between impressions and then by naming them. Connections resulting from the coincidence of impressions create linkages, so that the occurrence of one impression triggers those links and calls up the memory of those ideas with which it is associated (See Dorothy Emmet, "Coleridge and Philosophy").

Coleridge was critical of the literary taste of his contemporaries, and a literary conservative insofar as he was afraid that the lack of taste in the ever growing masses of literate people would mean a continued desecration of literature itself.

In 1800, he returned to England and shortly thereafter settled with his family and friends in Greta Hall at Keswick in the Lake District of Cumberland to be near Grasmere, where Wordsworth had moved. He was a houseguest of the Wordsworths' for eighteen months, but was a difficult houseguest, as his dependency on laudanum grew and his frequent nightmares would wake the children. He was also a fussy eater, to Dorothy Wordsworth's frustration, who had to cook. For example, not content with salt, Coleridge sprinkled cayenne pepper on his eggs, which he ate from a teacup. His marital problems, nightmares, illnesses, increased opium dependency, tensions with Wordsworth, and a lack of confidence in his poetic powers fuelled the composition of ''Dejection: An Ode'' and an intensification of his philosophical studies.

In 1802, Coleridge took a nine-day walking holiday in the fells of the Lake District. Coleridge is credited with the first recorded descent of Scafell to Mickledore via Broad Stand, although this was more due to his getting lost than a keenness for mountaineering.

It was at Sockburn that Coleridge wrote his ballad-poem ''Love'', addressed to Sara Hutchinson. The knight mentioned is the mailed figure on the Conyers tomb in ruined Sockburn church. The figure has a wyvern at his feet, a reference to the Sockburn Worm slain by Sir John Conyers (and a possible source for Lewis Carroll's '' Jabberwocky'').

The worm was supposedly buried under the rock in the nearby pasture; this was the 'greystone' of Coleridge's first draft, later transformed into a 'mount'. The poem was a direct inspiration for John Keats' famous poem ''La Belle Dame Sans Merci''.

Coleridge's early intellectual debts, besides German idealists like Kant and critics like Lessing, were first to William Godwin's ''Political Justice'', especially during his Pantisocratic period, and to David Hartley's ''Observations on Man'', which is the source of the psychology which is found in ''Frost at Midnight''. Hartley argued that one becomes aware of sensory events as impressions, and that "ideas" are derived by noticing similarities and differences between impressions and then by naming them. Connections resulting from the coincidence of impressions create linkages, so that the occurrence of one impression triggers those links and calls up the memory of those ideas with which it is associated (See Dorothy Emmet, "Coleridge and Philosophy").

Coleridge was critical of the literary taste of his contemporaries, and a literary conservative insofar as he was afraid that the lack of taste in the ever growing masses of literate people would mean a continued desecration of literature itself.

In 1800, he returned to England and shortly thereafter settled with his family and friends in Greta Hall at Keswick in the Lake District of Cumberland to be near Grasmere, where Wordsworth had moved. He was a houseguest of the Wordsworths' for eighteen months, but was a difficult houseguest, as his dependency on laudanum grew and his frequent nightmares would wake the children. He was also a fussy eater, to Dorothy Wordsworth's frustration, who had to cook. For example, not content with salt, Coleridge sprinkled cayenne pepper on his eggs, which he ate from a teacup. His marital problems, nightmares, illnesses, increased opium dependency, tensions with Wordsworth, and a lack of confidence in his poetic powers fuelled the composition of ''Dejection: An Ode'' and an intensification of his philosophical studies.

In 1802, Coleridge took a nine-day walking holiday in the fells of the Lake District. Coleridge is credited with the first recorded descent of Scafell to Mickledore via Broad Stand, although this was more due to his getting lost than a keenness for mountaineering.

Later life and increasing drug use

Travel and ''The Friend''

In 1804, he travelled toSicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

and Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

, working for a time as Acting Public Secretary of Malta under the Civil Commissioner, Alexander Ball, a task he performed successfully. He lived in San Anton Palace

San Anton Palace ( mt, Il-Palazz Sant'Anton) is a palace in Attard, Malta that currently serves as the official residence of the President of Malta. It was originally built in the early 17th century as a country villa for Antoine de Paule, a knig ...

in the village of Attard. He gave this up and returned to England in 1806. Dorothy Wordsworth was shocked at his condition upon his return. From 1807 to 1808, Coleridge returned to Malta and then travelled in Sicily and Italy, in the hope that leaving Britain's damp climate would improve his health and thus enable him to reduce his consumption of opium. Thomas De Quincey

Thomas Penson De Quincey (; 15 August 17858 December 1859) was an English writer, essayist, and literary critic, best known for his '' Confessions of an English Opium-Eater'' (1821). Many scholars suggest that in publishing this work De Quinc ...

alleges in his ''Recollections of the Lakes and the Lake Poets'' that it was during this period that Coleridge became a full-blown opium addict, using the drug as a substitute for the lost vigour and creativity of his youth. It has been suggested that this reflects De Quincey's own experiences more than Coleridge's.

His opium addiction (he was using as much as two quarts of laudanum a week) now began to take over his life: he separated from his wife Sara in 1808, quarrelled with Wordsworth in 1810, lost part of his annuity in 1811, and put himself under the care of Dr. Daniel in 1814. His addiction caused severe constipation, which required regular and humiliating enemas.

In 1809, Coleridge made his second attempt to become a newspaper publisher with the publication of the journal entitled ''The Friend''. It was a weekly publication that, in Coleridge's typically ambitious style, was written, edited, and published almost entirely single-handedly. Given that Coleridge tended to be highly disorganised and had no head for business, the publication was probably doomed from the start. Coleridge financed the journal by selling over five hundred subscriptions, over two dozen of which were sold to members of Parliament, but in late 1809, publication was crippled by a financial crisis and Coleridge was obliged to approach "Conversation Sharp", Tom Poole and one or two other wealthy friends for an emergency loan to continue. ''The Friend'' was an eclectic publication that drew upon every corner of Coleridge's remarkably diverse knowledge of law, philosophy, morals, politics, history, and literary criticism. Although it was often turgid, rambling, and inaccessible to most readers, it ran for 25 issues and was republished in book form a number of times. Years after its initial publication, a revised and expanded edition of ''The Friend'', with added philosophical content including his 'Essays on the Principles of Method', became a highly influential work and its effect was felt on writers and philosophers from John Stuart Mill to Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, abolitionist, and poet who led the transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a cham ...

.

London: final years and death

Between 1810 and 1820, Coleridge gave a series of lectures in London and

Between 1810 and 1820, Coleridge gave a series of lectures in London and Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city i ...

– those on Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

renewed interest in the playwright as a model for contemporary writers. Much of Coleridge's reputation as a literary critic is founded on the lectures that he undertook in the winter of 1810–11, which were sponsored by the Philosophical Institution and given at Scot's Corporation Hall off Fetter Lane, Fleet Street. These lectures were heralded in the prospectus as "A Course of Lectures on Shakespeare and Milton, in Illustration of the Principles of Poetry." Coleridge's ill-health, opium-addiction problems, and somewhat unstable personality meant that all his lectures were plagued with problems of delays and a general irregularity of quality from one lecture to the next. As a result of these factors, Coleridge often failed to prepare anything but the loosest set of notes for his lectures and regularly entered into extremely long digressions which his audiences found difficult to follow. However, it was the lecture on ''Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depi ...

'' given on 2 January 1812 that was considered the best and has influenced ''Hamlet'' studies ever since. Before Coleridge, ''Hamlet'' was often denigrated and belittled by critics from Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his '' nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his criticism of Christianity—es ...

to Dr. Johnson. Coleridge rescued the play's reputation, and his thoughts on it are often still published as supplements to the text.

In 1812 he allowed Robert Southey to make use of extracts from his vast number of private notebooks in their collaboration ''Omniana; Or, Horae Otiosiores''.

In August 1814, Coleridge was approached by Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824), known simply as Lord Byron, was an English romantic poet and Peerage of the United Kingdom, peer. He was one of the leading figures of the Romantic movement, and h ...

's publisher, John Murray, about the possibility of translating Goethe's classic '' Faust'' (1808). Coleridge was regarded by many as the greatest living writer on the demonic and he accepted the commission, only to abandon work on it after six weeks. Until recently, scholars were in agreement that Coleridge never returned to the project, despite Goethe's own belief in the 1820s that he had in fact completed a long translation of the work. In September 2007, Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the university press of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world, and its printing history dates back to the 1480s. Having been officially granted the legal right to print book ...

sparked a heated scholarly controversy by publishing an English translation of Goethe's work that purported to be Coleridge's long-lost masterpiece (the text in question first appeared anonymously in 1821).

Between 1814 and 1816, Coleridge rented from a local surgeon, Mr Page, in Calne, Wiltshire. He seemed able to focus on his work and manage his addiction, drafting ''Biographia Literaria

The ''Biographia Literaria'' is a critical autobiography by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, published in 1817 in two volumes. Its working title was 'Autobiographia Literaria'. The formative influences on the work were Wordsworth's theory of poetry, th ...

''. A blue plaque

A blue plaque is a permanent sign installed in a public place in the United Kingdom and elsewhere to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person, event, or former building on the site, serving as a historical marker. The term i ...

marks the property today.

In April 1816, Coleridge, with his addiction worsening, his spirits depressed, and his family alienated, took residence in the Highgate homes, then just north of London, of the physician James Gillman, first at South Grove and later at the nearby 3, The Grove. It is unclear whether his growing use of opium (and the brandy in which it was dissolved) was a symptom or a cause of his growing depression. Gillman was partially successful in controlling the poet's addiction. Coleridge remained in Highgate for the rest of his life, and the house became a place of literary pilgrimage for writers including Carlyle

Carlyle may refer to:

Places

* Carlyle, Illinois, a US city

* Carlyle, Kansas, an unincorporated place in the US

* Carlyle, Montana, a ghost town in the US

* Carlyle, Saskatchewan, a Canadian town

** Carlyle Airport

** Carlyle station

* Carly ...

and Emerson.

In Gillman's home, Coleridge finished his major prose work, the ''Biographia Literaria'' (mostly drafted in 1815, and finished in 1817), a volume composed of 23 chapters of autobiographical notes and dissertations on various subjects, including some incisive literary theory and criticism. He composed a considerable amount of poetry, of variable quality. He published other writings while he was living at the Gillman homes, notably the ''Lay Sermons'' of 1816 and 1817, ''Sibylline Leaves'' (1817), ''Hush'' (1820), ''Aids to Reflection'' (1825), and ''On the Constitution of the Church and State'' (1830). He also produced essays published shortly after his death, such as ''Essay on Faith'' (1838) and ''Confessions of an Inquiring Spirit'' (1840). A number of his followers were central to the Oxford Movement, and his religious writings profoundly shaped Anglicanism in the mid-nineteenth century.

Coleridge also worked extensively on the various manuscripts which form his " Opus Maximum", a work which was in part intended as a post-Kantian work of philosophical synthesis. The work was never published in his lifetime, and has frequently been seen as evidence for his tendency to conceive grand projects which he then had difficulty in carrying through to completion. But while he frequently berated himself for his "indolence", the long list of his published works calls this myth into question. Critics are divided on whether the "Opus Maximum", first published in 2002, successfully resolved the philosophical issues he had been exploring for most of his adult life.

Coleridge died in Highgate, London on 25 July 1834 as a result of heart failure

Heart failure (HF), also known as congestive heart failure (CHF), is a syndrome, a group of signs and symptoms caused by an impairment of the heart's blood pumping function. Symptoms typically include shortness of breath, excessive fatigue, ...

compounded by an unknown lung disorder, possibly linked to his use of opium. Coleridge had spent 18 years under the roof of the Gillman family, who built an addition onto their home to accommodate the poet.Faith may be defined as fidelity to our own being, so far as such being is not and cannot become an object of the senses; and hence, by clear inference or implication to being generally, as far as the same is not the object of the senses; and again to whatever is affirmed or understood as the condition, or concomitant, or consequence of the same. This will be best explained by an instance or example. That I am conscious of something within me peremptorily commanding me to do unto others as I would they should do unto me; in other words a categorical (that is, primary and unconditional) imperative; that the maxim (''regula maxima'', or supreme rule) of my actions, both inward and outward, should be such as I could, without any contradiction arising therefrom, will to be the law of all moral and rational beings. ''Essay on Faith''Carlyle described him at Highgate: "Coleridge sat on the brow of Highgate Hill, in those years, looking down on London and its smoke-tumult, like a sage escaped from the inanity of life's battle ... The practical intellects of the world did not much heed him, or carelessly reckoned him a metaphysical dreamer: but to the rising spirits of the young generation he had this dusky sublime character; and sat there as a kind of ''Magus'', girt in mystery and enigma; his Dodona oak-grove (Mr. Gilman's house at Highgate) whispering strange things, uncertain whether oracles or jargon."

Remains

Coleridge is buried in the aisle of St. Michael's Parish Church in Highgate, London. He was originally buried at Old Highgate Chapel, next to the main entrance of Highgate School, but was re-interred in St. Michael's in 1961. Coleridge could see the red door of the then new church from his last residence across the green, where he lived with a doctor he had hoped might cure him (in a house owned until 2022 by Kate Moss). When it was discovered Coleridge's vault had become derelict, the coffins – Coleridge's and those of his wife, daughter, son-in-law, and grandson – were moved to St. Michael's after an international fundraising appeal.

Drew Clode, a member of St. Michael's stewardship committee states, "they put the coffins in a convenient space which was dry and secure, and quite suitable, bricked them up and forgot about them". A recent excavation revealed the coffins were not in the location most believed, the far corner of the crypt, but actually below a memorial slab in the nave inscribed with: "Beneath this stone lies the body of Samuel Taylor Coleridge".

St. Michael's plans to restore the crypt and allow public access. Says vicar Kunle Ayodeji of the plans: "...we hope that the whole crypt can be cleared as a space for meetings and other uses, which would also allow access to Coleridge’s cellar."

Coleridge is buried in the aisle of St. Michael's Parish Church in Highgate, London. He was originally buried at Old Highgate Chapel, next to the main entrance of Highgate School, but was re-interred in St. Michael's in 1961. Coleridge could see the red door of the then new church from his last residence across the green, where he lived with a doctor he had hoped might cure him (in a house owned until 2022 by Kate Moss). When it was discovered Coleridge's vault had become derelict, the coffins – Coleridge's and those of his wife, daughter, son-in-law, and grandson – were moved to St. Michael's after an international fundraising appeal.

Drew Clode, a member of St. Michael's stewardship committee states, "they put the coffins in a convenient space which was dry and secure, and quite suitable, bricked them up and forgot about them". A recent excavation revealed the coffins were not in the location most believed, the far corner of the crypt, but actually below a memorial slab in the nave inscribed with: "Beneath this stone lies the body of Samuel Taylor Coleridge".

St. Michael's plans to restore the crypt and allow public access. Says vicar Kunle Ayodeji of the plans: "...we hope that the whole crypt can be cleared as a space for meetings and other uses, which would also allow access to Coleridge’s cellar."

Poetry

Coleridge is one of the most important figures in English poetry. His poems directly and deeply influenced all the major poets of the age. He was known by his contemporaries as a meticulous craftsman who was more rigorous in his careful reworking of his poems than any other poet, and Southey and Wordsworth were dependent on his professional advice. His influence on Wordsworth is particularly important because many critics have credited Coleridge with the very idea of "Conversational Poetry". The idea of utilising common, everyday language to express profound poetic images and ideas for which Wordsworth became so famous may have originated almost entirely in Coleridge’s mind. It is difficult to imagine Wordsworth’s great poems, ''The Excursion'' or ''The Prelude'', ever having been written without the direct influence of Coleridge’s originality. As important as Coleridge was to poetry as a poet, he was equally important to poetry as a critic. His philosophy of poetry, which he developed over many years, has been deeply influential in the field of literary criticism. This influence can be seen in such critics asA. O. Lovejoy

Arthur Oncken Lovejoy (October 10, 1873 – December 30, 1962) was an American philosopher and intellectual historian, who founded the discipline known as the history of ideas with his book ''The Great Chain of Being'' (1936), on the topic o ...

and I. A. Richards

Ivor Armstrong Richards CH (26 February 1893 – 7 September 1979), known as I. A. Richards, was an English educator, literary critic, poet, and rhetorician. His work contributed to the foundations of the New Criticism, a formalist movement ...

.

''The Rime of the Ancient Mariner'', ''Christabel'', and ''Kubla Khan''

Coleridge is arguably best known for his longer poems, particularly '' The Rime of the Ancient Mariner'' and '' Christabel''. Even those who have never read the ''Rime'' have come under its influence: its words have given the English language the

Coleridge is arguably best known for his longer poems, particularly '' The Rime of the Ancient Mariner'' and '' Christabel''. Even those who have never read the ''Rime'' have come under its influence: its words have given the English language the metaphor

A metaphor is a figure of speech that, for rhetorical effect, directly refers to one thing by mentioning another. It may provide (or obscure) clarity or identify hidden similarities between two different ideas. Metaphors are often compared wit ...

of an albatross around one's neck, the quotation of "water, water everywhere, nor any drop to drink" (almost always rendered as "but not a drop to drink"), and the phrase "a sadder and a wiser man" (usually rendered as "a sadder but wiser man"). The phrase "All creatures great and small" may have been inspired by ''The Rime'': "He prayeth best, who loveth best;/ All things both great and small;/ For the dear God who loveth us;/ He made and loveth all." Millions more who have never read the poem nonetheless know its story thanks to the 1984 song "Rime of the Ancient Mariner" by the English heavy metal band Iron Maiden

Iron Maiden are an English heavy metal band formed in Leyton, East London, in 1975 by bassist and primary songwriter Steve Harris. While fluid in the early years of the band, the lineup for most of the band's history has consisted of Harri ...

. '' Christabel'' is known for its musical rhythm, language, and its Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

tale.

'' Kubla Khan'', or, ''A Vision in a Dream, A Fragment'', although shorter, is also widely known. Both ''Kubla Khan'' and ''Christabel'' have an additional "Romantic

Romantic may refer to:

Genres and eras

* The Romantic era, an artistic, literary, musical and intellectual movement of the 18th and 19th centuries

** Romantic music, of that era

** Romantic poetry, of that era

** Romanticism in science, of that e ...

" aura because they were never finished. Stopford Brooke characterised both poems as having no rival due to their "exquisite metrical movement" and "imaginative phrasing."

The Conversation poems

The eight of Coleridge's poems listed above are now often discussed as a group entitled "Conversation poems". The term itself was coined in 1928 by George McLean Harper, who borrowed the subtitle of ''The Nightingale: A Conversation Poem'' (1798) to describe the seven other poems as well.Magnuson (2002), p. 45. The poems are considered by many critics to be among Coleridge's finest verses; thus Harold Bloom has written, "With ''Dejection'', ''The Ancient Mariner'', and ''Kubla Khan'', ''Frost at Midnight'' shows Coleridge at his most impressive." They are also among his most influential poems, as discussed further below. Harper himself considered that the eight poems represented a form ofblank verse

Blank verse is poetry written with regular metrical but unrhymed lines, almost always in iambic pentameter. It has been described as "probably the most common and influential form that English poetry has taken since the 16th century", and ...

that is "...more fluent and easy than Milton's, or any that had been written since Milton". In 2006 Robert Koelzer wrote about another aspect of this apparent "easiness", noting that Conversation poems such as "... Coleridge's ''The Eolian Harp'' and ''The Nightingale'' maintain a middle register of speech, employing an idiomatic language that is capable of being construed as un-symbolic and un-musical: language that lets itself be taken as 'merely talk' rather than rapturous 'song'."

The last ten lines of ''Frost at Midnight'' were chosen by Harper as the "best example of the peculiar kind of blank verse Coleridge had evolved, as natural-seeming as prose, but as exquisitely artistic as the most complicated sonnet." The speaker of the poem is addressing his infant son, asleep by his side:

The last ten lines of ''Frost at Midnight'' were chosen by Harper as the "best example of the peculiar kind of blank verse Coleridge had evolved, as natural-seeming as prose, but as exquisitely artistic as the most complicated sonnet." The speaker of the poem is addressing his infant son, asleep by his side:

In 1965, M. H. Abrams wrote a broad description that applies to the Conversation poems: "The speaker begins with a description of the landscape; an aspect or change of aspect in the landscape evokes a varied by integral process of memory, thought, anticipation, and feeling which remains closely intervolved with the outer scene. In the course of this meditation the lyric speaker achieves an insight, faces up to a tragic loss, comes to a moral decision, or resolves an emotional problem. Often the poem rounds itself to end where it began, at the outer scene, but with an altered mood and deepened understanding which is the result of the intervening meditation." In fact, Abrams was describing both the Conversation poems and later poems influenced by them. Abrams' essay has been called a "touchstone of literary criticism". As Paul Magnuson described it in 2002, "Abrams credited Coleridge with originating what Abrams called the 'greater Romantic lyric', a genre that began with Coleridge's 'Conversation' poems, and included Wordsworth's ''Tintern Abbey'', Shelley's ''Stanzas Written in Dejection'' and Keats's ''Ode to a Nightingale'', and was a major influence on more modern lyrics by Matthew Arnold, Walt Whitman, Wallace Stevens, and W. H. Auden."Therefore all seasons shall be sweet to thee, Whether the summer clothe the general earth With greenness, or the redbreast sit and sing Betwixt the tufts of snow on the bare branch Of mossy apple-tree, while the nigh thatch Smokes in the sun-thaw; whether the eave-drops fall Heard only in the trances of the blast, Or if the secret ministry of frost Shall hang them up in silent icicles, Quietly shining to the quiet Moon.

Literary criticism

''Biographia Literaria''

In addition to his poetry, Coleridge also wrote influential pieces of literary criticism including ''Biographia Literaria

The ''Biographia Literaria'' is a critical autobiography by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, published in 1817 in two volumes. Its working title was 'Autobiographia Literaria'. The formative influences on the work were Wordsworth's theory of poetry, th ...

'', a collection of his thoughts and opinions on literature which he published in 1817. The work delivered both biographical explanations of the author's life as well as his impressions on literature. The collection also contained an analysis of a broad range of philosophical principles of literature ranging from Aristotle to Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and aes ...

and Schelling and applied them to the poetry of peers such as William Wordsworth.Beckson (1963), pp. 265–266. Coleridge's explanation of metaphysical principles were popular topics of discourse in academic communities throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, and T.S. Eliot stated that he believed that Coleridge was "perhaps the greatest of English critics, and in a sense the last." Eliot suggests that Coleridge displayed "natural abilities" far greater than his contemporaries, dissecting literature and applying philosophical principles of metaphysics in a way that brought the subject of his criticisms away from the text and into a world of logical analysis that mixed logical analysis and emotion. However, Eliot also criticises Coleridge for allowing his emotion to play a role in the metaphysical process, believing that critics should not have emotions that are not provoked by the work being studied.Eliot (1956), pp. 50–56. Hugh Kenner in ''Historical Fictions'', discusses Norman Fruman's ''Coleridge, the Damaged Archangel'' and suggests that the term "criticism" is too often applied to ''Biographia Literaria'', which both he and Fruman describe as having failed to explain or help the reader understand works of art. To Kenner, Coleridge's attempt to discuss complex philosophical concepts without describing the rational process behind them displays a lack of critical thinking that makes the volume more of a biography than a work of criticism.Kenner (1995), pp. 40–45.

In ''Biographia Literaria'' and his poetry, symbols are not merely "objective correlatives" to Coleridge, but instruments for making the universe and personal experience intelligible and spiritually covalent. To Coleridge, the "cinque spotted spider," making its way upstream "by fits and starts," iographia Literariais not merely a comment on the intermittent nature of creativity, imagination, or spiritual progress, but the journey and destination of his life. The spider's five legs represent the central problem that Coleridge lived to resolve, the conflict between Aristotelian logic and Christian philosophy. Two legs of the spider represent the "me-not me" of thesis and antithesis, the idea that a thing cannot be itself and its opposite simultaneously, the basis of the clockwork Newtonian world view that Coleridge rejected. The remaining three legs—exothesis, mesothesis and synthesis or the Holy trinity—represent the idea that things can diverge without being contradictory. Taken together, the five legs—with synthesis in the center, form the Holy Cross of Ramist logic. The cinque-spotted spider is Coleridge's emblem of holism, the quest and substance of Coleridge's thought and spiritual life.

Coleridge and the influence of the Gothic

Coleridge wrote reviews of Ann Radcliffe's books and ''The Mad Monk'', among others. He comments in his reviews: "Situations of torment, and images of naked horror, are easily conceived; and a writer in whose works they abound, deserves our gratitude almost equally with him who should drag us by way of sport through a military hospital, or force us to sit at the dissecting-table of a natural philosopher. To trace the nice boundaries, beyond which terror and sympathy are deserted by the pleasurable emotions, – to reach those limits, yet never to pass them, hic labor, hic opus est." and "The horrible and the preternatural have usually seized on the popular taste, at the rise and decline of literature. Most powerful stimulants, they can never be required except by the torpor of an unawakened, or the languor of an exhausted, appetite... We trust, however, that satiety will banish what good sense should have prevented; and that, wearied with fiends, incomprehensible characters, with shrieks, murders, and subterraneous dungeons, the public will learn, by the multitude of the manufacturers, with how little expense of thought or imagination this species of composition is manufactured."

However, Coleridge used these elements in poems such as ''The Rime of the Ancient Mariner'' (1798), ''Christabel'' and ''Kubla Khan'' (published in 1816, but known in manuscript form before then) and certainly influenced other poets and writers of the time. Poems like these both drew inspiration from and helped to inflame the craze for