Samuel Adams on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Samuel Adams ( – October 2, 1803) was an American statesman,

Adams was born in

Adams was born in

After Adams had lost his money, his father made him a partner in the family's

After Adams had lost his money, his father made him a partner in the family's

Officials such as Governor Francis Bernard believed that common people acted only under the direction of agitators and blamed the violence on Adams. This interpretation was revived by scholars in the early 20th century, who viewed Adams as a master of

Officials such as Governor Francis Bernard believed that common people acted only under the direction of agitators and blamed the violence on Adams. This interpretation was revived by scholars in the early 20th century, who viewed Adams as a master of

Learning that British troops were on the way, the Boston Town Meeting met on September 12, 1768, and requested that Governor Bernard convene the General Court. Bernard refused, so the town meeting called on the other Massachusetts towns to send representatives to meet at

Learning that British troops were on the way, the Boston Town Meeting met on September 12, 1768, and requested that Governor Bernard convene the General Court. Bernard refused, so the town meeting called on the other Massachusetts towns to send representatives to meet at

A struggle over the

A struggle over the

Adams and the correspondence committees promoted opposition to the Tea Act. In every colony except Massachusetts, protesters were able to force the tea consignees to resign or to return the tea to England. In Boston, however, Governor Hutchinson was determined to hold his ground. He convinced the tea consignees, two of whom were his sons, not to back down. The Boston Caucus and then the Town Meeting attempted to compel the consignees to resign, but they refused. With the tea ships about to arrive, Adams and the Boston Committee of Correspondence contacted nearby committees to rally support.

The tea ship ''Dartmouth'' arrived in the Boston Harbor in late November, and Adams wrote a circular letter calling for a mass meeting to be held at Faneuil Hall on November 29. Thousands of people arrived, so many that the meeting was moved to the larger

Adams and the correspondence committees promoted opposition to the Tea Act. In every colony except Massachusetts, protesters were able to force the tea consignees to resign or to return the tea to England. In Boston, however, Governor Hutchinson was determined to hold his ground. He convinced the tea consignees, two of whom were his sons, not to back down. The Boston Caucus and then the Town Meeting attempted to compel the consignees to resign, but they refused. With the tea ships about to arrive, Adams and the Boston Committee of Correspondence contacted nearby committees to rally support.

The tea ship ''Dartmouth'' arrived in the Boston Harbor in late November, and Adams wrote a circular letter calling for a mass meeting to be held at Faneuil Hall on November 29. Thousands of people arrived, so many that the meeting was moved to the larger

In Philadelphia, Adams promoted colonial unity while using his political skills to lobby other delegates. On September 16, messenger

In Philadelphia, Adams promoted colonial unity while using his political skills to lobby other delegates. On September 16, messenger

The Continental Congress worked under a secrecy rule, so Adams's precise role in congressional deliberations is not fully documented. He appears to have had a major influence, working behind the scenes as a sort of "

The Continental Congress worked under a secrecy rule, so Adams's precise role in congressional deliberations is not fully documented. He appears to have had a major influence, working behind the scenes as a sort of "

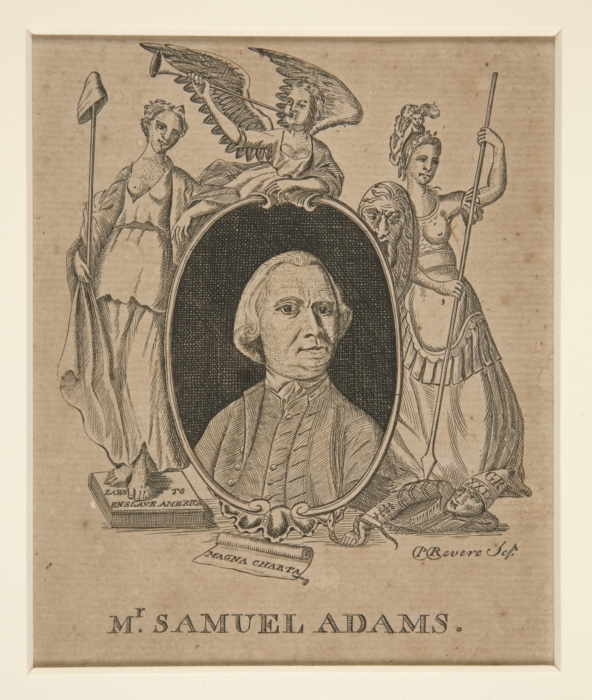

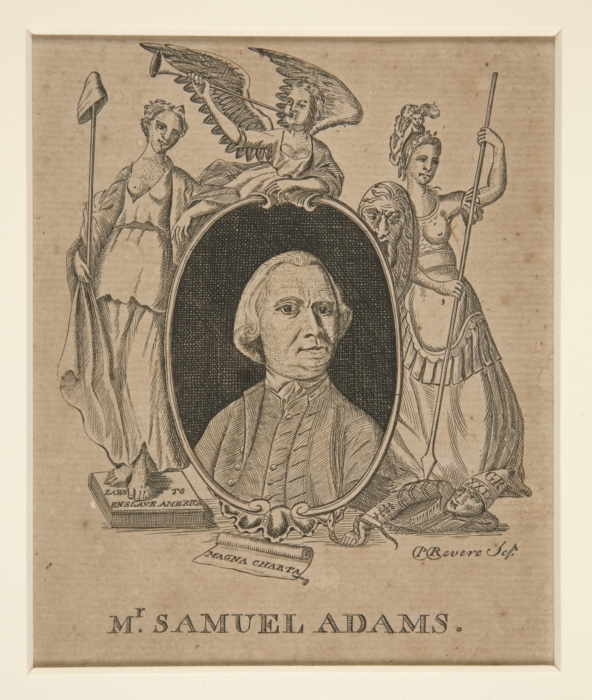

Samuel Adams is a controversial figure in American history. Disagreement about his significance and reputation began before his death and continues to the present.

Adams's contemporaries, both friends and foes, regarded him as one of the foremost leaders of the American Revolution. Thomas Jefferson, for example, characterized Adams as "truly the ''Man of the Revolution''." Leaders in other colonies were compared to him;

Samuel Adams is a controversial figure in American history. Disagreement about his significance and reputation began before his death and continues to the present.

Adams's contemporaries, both friends and foes, regarded him as one of the foremost leaders of the American Revolution. Thomas Jefferson, for example, characterized Adams as "truly the ''Man of the Revolution''." Leaders in other colonies were compared to him;

Samuel Adams Heritage Society

* * *

Samuel Adams quotes at Liberty-Tree.ca

{{DEFAULTSORT:Adams, Samuel 1722 births 1803 deaths Adams political family American Congregationalists American civil rights activists American people of English descent American political philosophers Boston Latin School alumni Burials at Granary Burying Ground Continental Congressmen from Massachusetts 18th-century American politicians Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Governors of Massachusetts Harvard College alumni Lieutenant Governors of Massachusetts Massachusetts state senators Members of the colonial Massachusetts House of Representatives Politicians from Boston Presidents of the Massachusetts Senate Signers of the Articles of Confederation Signers of the United States Declaration of Independence Candidates in the 1796 United States presidential election Signers of the Continental Association

political philosopher

Political philosophy or political theory is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships between them. Its topics include politics, l ...

, and a Founding Father of the United States

The Founding Fathers of the United States, known simply as the Founding Fathers or Founders, were a group of late-18th-century American revolutionary leaders who united the Thirteen Colonies, oversaw the war for independence from Great Britai ...

. He was a politician in colonial Massachusetts

Colonial or The Colonial may refer to:

* Colonial, of, relating to, or characteristic of a colony or colony (biology)

Architecture

* American colonial architecture

* French Colonial

* Spanish Colonial architecture

Automobiles

* Colonial (1920 ...

, a leader of the movement that became the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

, and one of the architects of the principles of American republicanism

The values, ideals and concept of republicanism have been discussed and celebrated throughout the history of the United States. As the United States has no formal hereditary ruling class, ''republicanism'' in this context does not refer to a ...

that shaped the political culture of the United States. He was a second cousin to his fellow Founding Father, President John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

.

Adams was born in Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, brought up in a religious and politically active family. A graduate of Harvard College

Harvard College is the undergraduate college of Harvard University, an Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636, Harvard College is the original school of Harvard University, the oldest institution of higher lea ...

, he was an unsuccessful businessman and tax collector before concentrating on politics. He was an influential official of the Massachusetts House of Representatives

The Massachusetts House of Representatives is the lower house of the Massachusetts General Court, the state legislature of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. It is composed of 160 members elected from 14 counties each divided into single-member ...

and the Boston Town Meeting

Town meeting is a form of local government in which most or all of the members of a community are eligible to legislate policy and budgets for local government. It is a town- or city-level meeting in which decisions are made, in contrast with ...

in the 1760s, and he became a part of a movement opposed to the British Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative supremacy ...

's efforts to tax the British America

British America comprised the colonial territories of the English Empire, which became the British Empire after the 1707 union of the Kingdom of England with the Kingdom of Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain, in the Americas from 16 ...

n colonies without their consent. His 1768 Massachusetts Circular Letter

The Massachusetts Circular Letter was a statement written by Samuel Adams and James Otis Jr., and passed by the Massachusetts House of Representatives (as constituted in the government of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, not the current constit ...

calling for colonial non-cooperation prompted the occupation of Boston by British soldiers, eventually resulting in the Boston Massacre

The Boston Massacre (known in Great Britain as the Incident on King Street) was a confrontation in Boston on March 5, 1770, in which a group of nine British soldiers shot five people out of a crowd of three or four hundred who were harassing t ...

of 1770. Adams and his colleagues devised a committee of correspondence

The committees of correspondence were, prior to the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, a collection of American political organizations that sought to coordinate opposition to British Parliament and, later, support for American independe ...

system in 1772 to help coordinate resistance to what he saw as the British government's attempts to violate the British Constitution

The constitution of the United Kingdom or British constitution comprises the written and unwritten arrangements that establish the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland as a political body. Unlike in most countries, no attempt ...

at the expense of the colonies, which linked like-minded Patriots throughout the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of Kingdom of Great Britain, British Colony, colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Fo ...

. Continued resistance to British policy resulted in the 1773 Boston Tea Party

The Boston Tea Party was an American political and mercantile protest by the Sons of Liberty in Boston, Massachusetts, on December 16, 1773. The target was the Tea Act of May 10, 1773, which allowed the British East India Company to sell t ...

and the coming of the American Revolution. Adams was actively involved with colonial newspapers publishing accounts of colonial sentiment over British colonial rule, which were fundamental in uniting the colonies.

Parliament passed the Coercive Acts

The Intolerable Acts were a series of punitive laws passed by the British Parliament in 1774 after the Boston Tea Party. The laws aimed to punish Massachusetts colonists for their defiance in the Tea Party protest of the Tea Act, a tax measure ...

in 1774, at which time Adams attended the Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislative bodies, with some executive function, for thirteen of Britain's colonies in North America, and the newly declared United States just before, during, and after the American Revolutionary War. ...

in Philadelphia which was convened to coordinate a colonial response. He helped guide Congress towards issuing the Continental Association

The Continental Association, also known as the Articles of Association or simply the Association, was an agreement among the American colonies adopted by the First Continental Congress on October 20, 1774. It called for a trade boycott against ...

in 1774 and the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of th ...

in 1776, and he helped draft the Articles of Confederation

The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union was an agreement among the 13 Colonies of the United States of America that served as its first frame of government. It was approved after much debate (between July 1776 and November 1777) by ...

and the Massachusetts Constitution

The Constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts is the fundamental governing document of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, one of the 50 individual state governments that make up the United States of America. As a member of the Massachuset ...

. Adams returned to Massachusetts after the American Revolution, where he served in the state senate

A state legislature in the United States is the legislative body of any of the 50 U.S. states. The formal name varies from state to state. In 27 states, the legislature is simply called the ''Legislature'' or the ''State Legislature'', whil ...

and was eventually elected governor.

Samuel Adams later became a controversial figure in American history. Accounts written in the 19th century praised him as someone who had been steering his fellow colonists towards independence long before the outbreak of the Revolutionary War. This view was challenged by negative assessments of Adams in the first half of the 20th century, mostly by British historians, in which he was portrayed as a master of propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

who provoked "mob violence

A riot is a form of civil disorder commonly characterized by a group lashing out in a violent public disturbance against authority, property, or people.

Riots typically involve destruction of property, public or private. The property target ...

" to achieve his goals. However, according to biographer Mark Puls, a different account emerges upon examination of Adams' many writings regarding the civil rights of the colonists, while the "mob" referred to were a highly reflective group of men inspired by Adams who made his case with reasoned arguments in pamphlets and newspapers, without the use of emotional rhetoric.

Early life

Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

in the British colony of Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

on September 16, 1722, an Old Style date that is sometimes converted to the New Style date of September 27. Adams was one of twelve children born to Samuel Adams, Sr. Samuel Adams Sr. (1689–1748) was an American brewer, father of American Founding Father Samuel Adams, and first cousin once removed of John Adams.

Biography

He was born in Boston, on May 16, 1689 to Captain John Adams and Hannah Adams (nee Webb). ...

, and Mary (Fifield) Adams in an age of high infant mortality; only three of these children lived past their third birthday. Adams's parents were devout Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

s and members of the Old South Congregational Church. The family lived on Purchase Street in Boston. Adams was proud of his Puritan heritage, and emphasized Puritan values in his political career, especially virtue

Virtue ( la, virtus) is moral excellence. A virtue is a trait or quality that is deemed to be morally good and thus is valued as a foundation of principle and good moral being. In other words, it is a behavior that shows high moral standard ...

.

Samuel Adams, Sr. (1689–1748) was a prosperous merchant and church deacon

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions. Major Christian churches, such as the Catholic Churc ...

. Deacon Adams became a leading figure in Boston politics through an organization that became known as the Boston Caucus

The Boston Caucus was an informal political organization that had considerable influence in Boston in the years before and after the American Revolution. This was perhaps the first use of the word ''caucus'' to mean a meeting of members of a movem ...

, which promoted candidates who supported popular causes. Members of the Caucus helped shape the agenda of the Boston Town Meeting

Town meeting is a form of local government in which most or all of the members of a community are eligible to legislate policy and budgets for local government. It is a town- or city-level meeting in which decisions are made, in contrast with ...

. A New England town meeting

Town meeting is a form of local government in which most or all of the members of a community are eligible to legislate policy and budgets for local government. It is a town- or city-level meeting in which decisions are made, in contrast with ...

is a form of local government

Local government is a generic term for the lowest tiers of public administration within a particular sovereign state. This particular usage of the word government refers specifically to a level of administration that is both geographically-loca ...

with elected officials, and not just a gathering of citizens; according to historian William Fowler, it was "the most democratic institution in the British empire". Deacon Adams rose through the political ranks, becoming a justice of the peace, a selectman, and a member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives

The Massachusetts House of Representatives is the lower house of the Massachusetts General Court, the state legislature of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. It is composed of 160 members elected from 14 counties each divided into single-member ...

. He worked closely with Elisha Cooke, Jr. (1678–1737), the leader of the "popular party", a faction that resisted any encroachment by royal officials on the colonial rights embodied in the Massachusetts Charter

The Massachusetts Charter of 1691 was a charter that formally established the Province of Massachusetts Bay. Issued by the government of William III and Mary II, the corulers of the Kingdom of England, the charter defined the government of the co ...

of 1691. In the coming years, members of the "popular party" became known as Whigs or Patriots.

The younger Samuel Adams attended Boston Latin School

The Boston Latin School is a public exam school in Boston, Massachusetts. It was established on April 23, 1635, making it both the oldest public school in the British America and the oldest existing school in the United States. Its curriculum f ...

and then entered Harvard College

Harvard College is the undergraduate college of Harvard University, an Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636, Harvard College is the original school of Harvard University, the oldest institution of higher lea ...

in 1736. His parents hoped that his schooling would prepare him for the ministry, but Adams gradually shifted his interest to politics. After graduating in 1740, Adams continued his studies, earning a master's degree

A master's degree (from Latin ) is an academic degree awarded by universities or colleges upon completion of a course of study demonstrating mastery or a high-order overview of a specific field of study or area of professional practice.

in 1743. In his thesis, he argued that it was "lawful to resist the Supreme Magistrate, if the Commonwealth cannot otherwise be preserved", which indicated that his political views, like his father's, were oriented towards colonial rights.

Adams's life was greatly affected by his father's involvement in a banking controversy. In 1739, Massachusetts was facing a serious currency shortage, and Deacon Adams and the Boston Caucus created a "land bank" which issued paper money to borrowers who mortgaged their land as security. The land bank was generally supported by the citizenry and the popular party, which dominated the House of Representatives, the lower branch of the General Court. Opposition to the land bank came from the more aristocratic "court party", who were supporters of the royal governor Jonathan Belcher

Jonathan Belcher (8 January 1681/8231 August 1757) was a merchant, politician, and slave trader from colonial Massachusetts who served as both governor of Massachusetts Bay and governor of New Hampshire from 1730 to 1741 and governor of New J ...

and controlled the Governor's Council The governments of the Thirteen Colonies of British America developed in the 17th and 18th centuries under the influence of the British constitution. After the Thirteen Colonies had become the United States, the experience under colonial rule would ...

, the upper chamber of the General Court. The court party used its influence to have the British Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative supremacy ...

dissolve the land bank in 1741. Directors of the land bank, including Deacon Adams, became personally liable for the currency still in circulation, payable in silver and gold. Lawsuits over the bank persisted for years, even after Deacon Adams's death, and the younger Samuel Adams often had to defend the family estate from seizure by the government. For Adams, these lawsuits "served as a constant personal reminder that Britain's power over the colonies could be exercised in arbitrary and destructive ways."

Early career

After leaving Harvard in 1743, Adams was unsure about his future. He considered becoming a lawyer but instead decided to go into business. He worked atThomas Cushing

Thomas Cushing III (March 24, 1725 – February 28, 1788) was an American lawyer, merchant, and statesman from Boston, Massachusetts. Active in Boston politics, he represented the city in the provincial assembly from 1761 to its dissolution ...

's counting house

A counting house, or counting room, was traditionally an office in which the financial books of a business were kept. It was also the place that the business received appointments and correspondence relating to demands for payment.

As the use of ...

, but the job only lasted a few months because Cushing felt that Adams was too preoccupied with politics to become a good merchant. Adams's father then lent him £1,000 to go into business for himself, a substantial amount for that time. Adams's lack of business instincts were confirmed; he lent half of this money to a friend who never repaid, and frittered away the other half. Adams always remained, in the words of historian Pauline Maier

Pauline Alice Maier (née Rubbelke; April 27, 1938 – August 12, 2013) was a revisionist historian of the American Revolution, whose work also addressed the late colonial period and the history of the United States after the end of the Revolut ...

, "a man utterly uninterested in either making or possessing money".Maier, ''American National Biography''.

After Adams had lost his money, his father made him a partner in the family's

After Adams had lost his money, his father made him a partner in the family's malthouse

A malt house, malt barn, or maltings, is a building where cereal grain is converted into malt by soaking it in water, allowing it to sprout and then drying it to stop further growth. The malt is used in brewing beer, whisky and in certain food ...

, which was next to the family home on Purchase Street. Several generations of Adamses were maltsters, who produced the malt

Malt is germinated cereal grain that has been dried in a process known as " malting". The grain is made to germinate by soaking in water and is then halted from germinating further by drying with hot air.

Malted grain is used to make beer, wh ...

necessary for brewing beer. Years later, a poet poked fun at Adams by calling him "Sam the maltster". Adams has often been described as a brewer, but the extant evidence suggests that he worked as a maltster and not a brewer.

In January 1748, Adams and some friends were inflamed by British impressment

Impressment, colloquially "the press" or the "press gang", is the taking of men into a military or naval force by compulsion, with or without notice. European navies of several nations used forced recruitment by various means. The large size of ...

and launched ''The Independent Advertiser

''The Independent Advertiser'' was an American patriot publication, founded in 1748 in Boston by the then 26-year-old Samuel Adams, advocating republicanism, liberty and independence from Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the No ...

'', a weekly newspaper that printed many political essays written by Adams. His essays drew heavily upon English political theorist John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism ...

's ''Second Treatise of Government

''Two Treatises of Government'' (or ''Two Treatises of Government: In the Former, The False Principles, and Foundation of Sir Robert Filmer, and His Followers, Are Detected and Overthrown. The Latter Is an Essay Concerning The True Original, ...

'', and they emphasized many of the themes that characterized his subsequent career. He argued that the people must resist any encroachment on their constitutional rights. He cited the decline of the Roman Empire

The fall of the Western Roman Empire (also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome) was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its vas ...

as an example of what could happen to New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

if it were to abandon its Puritan values.

When Deacon Adams died in 1748, Adams was given the responsibility of managing the family's affairs. In October 1749, he married Elizabeth Checkley, his pastor's daughter. Elizabeth gave birth to six children over the next seven years, but only two lived to adulthood: Samuel (born 1751) and Hannah (born 1756). In July 1757, Elizabeth died soon after giving birth to a stillborn son. Adams remarried in 1764 to Elizabeth Wells, but had no other children.

Like his father, Adams embarked on a political career with the support of the Boston Caucus. He was elected to his first political office in 1747, serving as one of the clerks of the Boston market. In 1756, the Boston Town Meeting elected him to the post of tax collector, which provided a small income. He often failed to collect taxes from his fellow citizens, which increased his popularity among those who did not pay, but left him liable for the shortage. By 1765, his account was more than £8,000 in arrears. The town meeting was on the verge of bankruptcy, and Adams was compelled to file suit against delinquent taxpayers, but many taxes went uncollected. In 1768, his political opponents used the situation to their advantage, obtaining a court judgment of £1,463 against him. Adams's friends paid off some of the deficit, and the town meeting wrote off the remainder. By then, he had emerged as a leader of the popular party, and the embarrassing situation did not lessen his influence.

Conflict with Great Britain

Samuel Adams emerged as an important public figure in Boston soon after theBritish Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

's victory in the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the ...

(1754–1763). The British Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative supremacy ...

found itself deep in debt and looking for new sources of revenue, and they sought to directly tax the colonies of British America

British America comprised the colonial territories of the English Empire, which became the British Empire after the 1707 union of the Kingdom of England with the Kingdom of Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain, in the Americas from 16 ...

for the first time. This tax dispute was part of a larger divergence between British and American interpretations of the British Constitution

The constitution of the United Kingdom or British constitution comprises the written and unwritten arrangements that establish the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland as a political body. Unlike in most countries, no attempt ...

and the extent of Parliament's authority in the colonies.

In the years leading up to and into the revolution Adams made frequent use of colonial newspapers and began openly criticizing British colonial policy and by 1775 was advocating independence from Britain. Adams was foremost in actively using newspapers like the ''Boston Gazette

The ''Boston Gazette'' (1719–1798) was a newspaper published in Boston, in the British North American colonies. It was a weekly newspaper established by William Brooker, who was just appointed Postmaster of Boston, with its first issue release ...

'' to promote the ideals of colonial rights by publishing his letters and other accounts which sharply criticized British colonial policy and especially the practice of colonial taxation without representation.The ''Boston Gazette'' had a circulation of two thousand, published weekly, which was considerable number for that time. Its publishers, Benjamin Edes

Benjamin Edes (October 15, 1732 – December 11, 1803) was an early American printer, publisher, newspaper journalist and a revolutionary advocate before and during the American Revolution. He is best known, along with John Gill, as the publishe ...

and John Gill John Gill may refer to:

Sports

*John Gill (cricketer) (1854–1888), New Zealand cricketer

*John Gill (coach) (1898–1997), American football coach

*John Gill (footballer, born 1903), English professional footballer

*John Gill (American football) ...

, both founding members of the Sons of Liberty, were on friendly and cooperative terms with Adams, James Otis and the Boston Caucus

The Boston Caucus was an informal political organization that had considerable influence in Boston in the years before and after the American Revolution. This was perhaps the first use of the word ''caucus'' to mean a meeting of members of a movem ...

. Historian Ralph Harlow maintains that there is no doubt of the influence these men had in arousing public feeling. In his writings in the ''Boston Gazette'', Adams often wrote under a variety of assumed names, including "Candidus", "Vindex", and others. In less common instances his letters were unsigned.

Adams earnestly endeavored to awaken his fellow citizens over the perceived attacks on their Constitutional rights, with emphasis aimed at Massachusetts Governor Thomas Hutchinson. Hutchinson stressed that no one matched Adams' efforts in promoting the radical Whig position and the revolutionary cause, which Adams accordingly demonstrated with his numerous published and pointedly written essays and letters. In each of its issues from early September through mid-October of 1771, the ''Gazette'' published Adams' inciteful essays, one of which criticized the Parliament for using colonial taxes to pay Hutchinson's annual salary of £2,000. In a letter of February 1770, published by the ''New York Journal'' Adams maintained that it became increasingly difficult to view King George III as one who was not passively involved in Parliamentary decisions. In it he asked if anyone of common sense could deny that the King had assumed a “personal and decisive” role against the Americans.

Sugar Act

The first step in the new program was the Sugar Act of 1764, which Adams saw as an infringement of longstanding colonial rights. Colonists were not represented in Parliament, he argued, and therefore they could not be taxed by that body; the colonists were represented by the colonial assemblies, and only they could levy taxes upon them. Adams expressed these views in May 1764, when the Boston Town Meeting elected its representatives to the Massachusetts House. As was customary, the town meeting provided the representatives with a set of written instructions, which Adams was selected to write. Adams highlighted what he perceived to be the dangers oftaxation without representation

"No taxation without representation" is a political slogan that originated in the American Revolution, and which expressed one of the primary grievances of the American colonists for Great Britain. In short, many colonists believed that as they ...

:

For if our Trade may be taxed, why not our Lands? Why not the Produce of our Lands & everything we possess or make use of? This we apprehend annihilates our Charter Right to govern & tax ourselves. It strikes at our British privileges, which as we have never forfeited them, we hold in common with our Fellow Subjects who are Natives of Britain. If Taxes are laid upon us in any shape without our having a legal Representation where they are laid, are we not reduced from the Character of free Subjects to the miserable State of tributary Slaves?"When the Boston Town Meeting approved the Adams instructions on May 24, 1764," writes historian John K. Alexander, "it became the first political body in America to go on record stating Parliament could not constitutionally tax the colonists. The directives also contained the first official recommendation that the colonies present a unified defense of their rights." Adams's instructions were published in newspapers and pamphlets, and he soon became closely associated with James Otis, Jr., a member of the Massachusetts House famous for his defense of colonial rights. Otis boldly challenged the constitutionality of certain acts of Parliament, but he would not go as far as Adams, who was moving towards the conclusion that Parliament did not have sovereignty over the colonies.

Stamp Act

In 1765, Parliament passed the Stamp Act which required colonists to pay a new tax on most printed materials. News of the passage of the Stamp Act produced an uproar in the colonies. The colonial response echoed Adams's 1764 instructions. In June 1765, Otis called for aStamp Act Congress

The Stamp Act Congress (October 7 – 25, 1765), also known as the Continental Congress of 1765, was a meeting held in New York, New York, consisting of representatives from some of the British colonies in North America. It was the first gat ...

to coordinate colonial resistance. The Virginia House of Burgesses

The House of Burgesses was the elected representative element of the Virginia General Assembly, the legislative body of the Colony of Virginia. With the creation of the House of Burgesses in 1642, the General Assembly, which had been established ...

passed a widely reprinted set of resolves against the Stamp Act that resembled Adams's arguments against the Sugar Act. Adams argued that the Stamp Act was unconstitutional; he also believed that it would hurt the economy of the British Empire. He supported calls for a boycott of British goods to put pressure on Parliament to repeal the tax.

In Boston, a group called the Loyal Nine

The Loyal Nine (also spelled Loyall Nine) were nine American patriots from Boston who met in secret to plan protests against the Stamp Act of 1765. Mostly middle-class businessmen, the Loyal Nine enlisted Ebenezer Mackintosh to rally large crowds ...

, a precursor to the Sons of Liberty

The Sons of Liberty was a loosely organized, clandestine, sometimes violent, political organization active in the Thirteen American Colonies founded to advance the rights of the colonists and to fight taxation by the British government. It pl ...

, organized protests of the Stamp Act. Adams was friendly with the Loyal Nine but was not a member. On August 14, stamp distributor Andrew Oliver was hanged in effigy from Boston's Liberty Tree; that night, his home was ransacked and his office demolished. On August 26, lieutenant governor Thomas Hutchinson's home was destroyed by an angry crowd.

Officials such as Governor Francis Bernard believed that common people acted only under the direction of agitators and blamed the violence on Adams. This interpretation was revived by scholars in the early 20th century, who viewed Adams as a master of

Officials such as Governor Francis Bernard believed that common people acted only under the direction of agitators and blamed the violence on Adams. This interpretation was revived by scholars in the early 20th century, who viewed Adams as a master of propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

who manipulated mobs into doing his bidding. For example, historian John C. Miller wrote in 1936 in what became the standard biography of Adams that Adams "controlled" Boston with his "trained mob". Some modern scholars have argued that this interpretation is a myth, and that there is no evidence that Adams had anything to do with the Stamp Act riots. After the fact, Adams did approve of the August 14 action because he saw no other legal options to resist what he viewed as an unconstitutional act by Parliament, but he condemned attacks on officials' homes as "mobbish". According to the modern scholarly interpretation of Adams, he supported legal methods of resisting parliamentary taxation, such as petitions, boycotts, and nonviolent demonstrations, but he opposed mob violence which he saw as illegal, dangerous, and counter-productive.

In September 1765, Adams was once again appointed by the Boston Town Meeting to write the instructions for Boston's delegation to the Massachusetts House of Representatives. As it turned out, he wrote his own instructions; on September 27, the town meeting selected him to replace the recently deceased Oxenbridge Thacher as one of Boston's four representatives in the assembly. James Otis was attending the Stamp Act Congress in New York City, so Adams was the primary author of a series of House resolutions against the Stamp Act, which were more radical than those passed by the Stamp Act Congress. Adams was one of the first colonial leaders to argue that mankind possessed certain natural rights that governments could not violate.

The Stamp Act was scheduled to go into effect on November 1, 1765, but it was not enforced because protestors throughout the colonies had compelled stamp distributors to resign. Eventually, British merchants were able to convince Parliament to repeal the tax. By May 16, 1766, news of the repeal had reached Boston. There was celebration throughout the city, and Adams made a public statement of thanks to British merchants for helping their cause.

The Massachusetts popular party gained ground in the May 1766 elections. Adams was re-elected to the House and selected as its clerk, in which position he was responsible for official House papers. In the coming years, Adams used his position as clerk to great effect in promoting his political message. Joining Adams in the House was John Hancock

John Hancock ( – October 8, 1793) was an American Founding Father, merchant, statesman, and prominent Patriot of the American Revolution. He served as president of the Second Continental Congress and was the first and third Governor of t ...

, a new representative from Boston. Hancock was a wealthy merchant—perhaps the richest man in Massachusetts—but a relative newcomer to politics. He was initially a protégé of Adams, and he used his wealth to promote the Whig cause.

Townshend Acts

After the repeal of the Stamp Act, Parliament took a different approach to raising revenue, passing theTownshend Acts

The Townshend Acts () or Townshend Duties, were a series of British acts of Parliament passed during 1767 and 1768 introducing a series of taxes and regulations to fund administration of the British colonies in America. They are named after the ...

in 1767 which established new duties

A duty (from "due" meaning "that which is owing"; fro, deu, did, past participle of ''devoir''; la, debere, debitum, whence "debt") is a commitment or expectation to perform some action in general or if certain circumstances arise. A duty may ...

on various goods imported into the colonies. These duties were relatively low because the British ministry wanted to establish the precedent that Parliament had the right to impose tariffs on the colonies before raising them. Revenues from these duties were to be used to pay for governors and judges who would be independent of colonial control. To enforce compliance with the new laws, the Townshend Acts created a customs

Customs is an authority or agency in a country responsible for collecting tariffs and for controlling the flow of goods, including animals, transports, personal effects, and hazardous items, into and out of a country. Traditionally, customs ...

agency known as the American Board of Custom Commissioners, which was headquartered in Boston.

Resistance to the Townshend Acts grew slowly. The General Court was not in session when news of the acts reached Boston in October 1767. Adams therefore used the Boston Town Meeting to organize an economic boycott, and called for other towns to do the same. By February 1768, towns in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut had joined the boycott. Opposition to the Townshend Acts was also encouraged by ''Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania

''Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania'' is a series of essays written by the Pennsylvania lawyer and legislator John Dickinson (1732–1808) and published under the pseudonym "A Farmer" from 1767 to 1768. The twelve letters were widely read and r ...

'', a series of popular essays by John Dickinson

John Dickinson (November 13 Julian_calendar">/nowiki>Julian_calendar_November_2.html" ;"title="Julian_calendar.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Julian calendar">/nowiki>Julian calendar November 2">Julian_calendar.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Julian calendar" ...

which started appearing in December 1767. Dickinson's argument that the new taxes were unconstitutional had been made before by Adams, but never to such a wide audience.

In January 1768, the Massachusetts House sent a petition to King George asking for his help. Adams and Otis requested that the House send the petition to the other colonies, along with what became known as the Massachusetts Circular Letter

The Massachusetts Circular Letter was a statement written by Samuel Adams and James Otis Jr., and passed by the Massachusetts House of Representatives (as constituted in the government of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, not the current constit ...

, which became "a significant milestone on the road to revolution". The letter written by Adams called on the colonies to join with Massachusetts in resisting the Townshend Acts. The House initially voted against sending the letter and petition to the other colonies but, after some politicking by Adams and Otis, it was approved on February 11.

British colonial secretary Lord Hillsborough

Wills Hill, 1st Marquess of Downshire, (30 May 1718 – 7 October 1793), known as The 2nd Viscount Hillsborough from 1742 to 1751 and as The 1st Earl of Hillsborough from 1751 to 1789, was a British politician of the Georgian era.

Best known ...

, hoping to prevent a repeat of the Stamp Act Congress, instructed the colonial governors in America to dissolve the assemblies if they responded to the Massachusetts Circular Letter. He also directed Massachusetts Governor Francis Bernard to have the Massachusetts House rescind the letter. On June 30, the House refused to rescind the letter by a vote of 92 to 17, with Adams citing their right to petition

The right to petition government for redress of grievances is the right to make a complaint to, or seek the assistance of, one's government, without fear of punishment or reprisals.

In Europe, Article 44 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of ...

as justification. Far from complying with the governor's order, Adams instead presented a new petition to the king asking that Governor Bernard be removed from office. Bernard responded by dissolving the legislature.

The commissioners of the Customs Board found that they were unable to enforce trade regulations in Boston, so they requested military assistance. Help came in the form of , a fifty-gun warship which arrived in Boston Harbor

Boston Harbor is a natural harbor and estuary of Massachusetts Bay, and is located adjacent to the city of Boston, Massachusetts. It is home to the Port of Boston, a major shipping facility in the northeastern United States.

History

...

in May 1768. Tensions escalated after the captain of ''Romney'' began to impress

The Independent Monitor for the Press (IMPRESS) is an independent press regulator in the UK. It was the first to be recognised by the Press Recognition Panel. Unlike the Independent Press Standards Organisation (IPSO), IMPRESS is fully compliant ...

local sailors. The situation exploded on June 10, when customs officials seized , a sloop owned by John Hancock—a leading critic of the Customs Board—for alleged customs violations. Sailors and marines came ashore from ''Romney'' to tow away ''Liberty'', and a riot broke out. Things calmed down in the following days, but fearful customs officials packed up their families and fled for protection to ''Romney'' and eventually to Castle William

Fort Independence is a granite bastion fort that provided harbor defenses for Boston, Massachusetts. Located on Castle Island (Massachusetts), Castle Island, Fort Independence is one of the oldest continuously fortified sites of England, English ...

, an island fort in the harbor.

Governor Bernard wrote to London in response to the ''Liberty'' incident and the struggle over the Circular Letter, informing his superiors that troops were needed in Boston to restore order. Lord Hillsborough ordered four regiments of the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

to Boston.

Boston under occupation

Learning that British troops were on the way, the Boston Town Meeting met on September 12, 1768, and requested that Governor Bernard convene the General Court. Bernard refused, so the town meeting called on the other Massachusetts towns to send representatives to meet at

Learning that British troops were on the way, the Boston Town Meeting met on September 12, 1768, and requested that Governor Bernard convene the General Court. Bernard refused, so the town meeting called on the other Massachusetts towns to send representatives to meet at Faneuil Hall

Faneuil Hall ( or ; previously ) is a marketplace and meeting hall located near the waterfront and today's Government Center, in Boston, Massachusetts. Opened in 1742, it was the site of several speeches by Samuel Adams, James Otis, and others ...

beginning on September 22. About 100 towns sent delegates to the convention, which was effectively an unofficial session of the Massachusetts House. The convention issued a letter which insisted that Boston was not a lawless town, using language more moderate than what Adams desired, and that the impending military occupation violated Bostonians' natural, constitutional, and charter rights. By the time that the convention adjourned, British troop transports had arrived in Boston Harbor. Two regiments disembarked in October 1768, followed by two more in November.

According to some accounts, the occupation of Boston was a turning point for Adams, after which he gave up hope of reconciliation and secretly began to work towards American independence. However, historian Carl Becker wrote in 1928 that "there is no clear evidence in his contemporary writings that such was the case. Nevertheless, the traditional, standard view of Adams is that he desired independence before most of his contemporaries and steadily worked towards this goal for years. There is much speculation among historians, with compelling arguments either way, over whether and when before the war Adams openly advocated independence from Britain. Historian Pauline Maier

Pauline Alice Maier (née Rubbelke; April 27, 1938 – August 12, 2013) was a revisionist historian of the American Revolution, whose work also addressed the late colonial period and the history of the United States after the end of the Revolut ...

challenged the idea that he had in 1980, arguing instead that Adams, like most of his peers, did not embrace independence until after the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

had begun in 1775. According to Maier, Adams at this time was a reformer rather than a revolutionary; he sought to have the British ministry change its policies, and warned Britain that independence would be the inevitable result of a failure to do so. Adams biographer Stewart Beach also questioned whether Adams sought independence before the mid-1770s, in that Hutchinson, who despised Adams, and had reason enough to, never once in his papers accused Adams of pushing the idea of independence from Britain, though he notes that Adams had publicly promised retaliation to any British troops sent over to quell the rebellion, moreover, that Adams was never accused of treason by the Parliament before the war.

Adams wrote numerous letters and essays in opposition to the occupation, which he considered a violation of the 1689 Bill of Rights. The occupation was publicized throughout the colonies in the ''Journal of Occurrences The ''Journal of Occurrences'', also known as ''Journal of the Times'' and ''Journal of Transactions in Boston'', was a series of newspaper articles published from 1768 to 1769 in the ''New York Journal and Packet'' and other newspapers, chronicling ...

'', an unsigned series of newspaper articles that may have been written by Adams in collaboration with others. The ''Journal'' presented what it claimed to be a factual daily account of events in Boston during the military occupation, an innovative approach in an era without professional newspaper reporters. It depicted a Boston besieged by unruly British soldiers who assaulted men and raped women with regularity and impunity, drawing upon the traditional Anglo-American distrust of standing armies garrisoned among civilians. The ''Journal'' ceased publication on August 1, 1769, which was a day of celebration in Boston: Governor Bernard had left Massachusetts, never to return.

Adams continued to work on getting the troops withdrawn and keeping the boycott going until the Townshend duties were repealed. Two regiments were removed from Boston in 1769, but the other two remained. Tensions between soldiers and civilians eventually resulted in the killing of five civilians in the Boston Massacre

The Boston Massacre (known in Great Britain as the Incident on King Street) was a confrontation in Boston on March 5, 1770, in which a group of nine British soldiers shot five people out of a crowd of three or four hundred who were harassing t ...

of March 1770. According to the "propagandist interpretation" of Adams popularized by historian John Miller, Adams deliberately provoked the incident to promote his secret agenda of American independence. According to Pauline Maier, however, "There is no evidence that he prompted the Boston Massacre riot".

After the Boston Massacre, Adams and other town leaders met with Bernard's successor Governor Thomas Hutchinson and with Colonel William Dalrymple William Dalrymple may refer to:

* William Dalrymple (1678–1744), Scottish Member of Parliament

* William Dalrymple (moderator) (1723–1814), Scottish minister and religious writer

* William Dalrymple (British Army officer) (1736–1807), Scott ...

, the army commander, to demand the withdrawal of the troops. The situation remained explosive, and so Dalrymple agreed to remove both regiments to Castle William. Adams wanted the soldiers to have a fair trial, because this would show that Boston was not controlled by a lawless mob, but was instead the victim of an unjust occupation. He convinced his cousins John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

and Josiah Quincy to defend the soldiers, knowing that those Whigs would not slander Boston to gain an acquittal. However, Adams wrote essays condemning the outcome of the trials; he thought that the soldiers should have been convicted of murder.

"Quiet period"

After the Boston Massacre, politics in Massachusetts entered what is sometimes known as the "quiet period". In April 1770, Parliament repealed the Townshend duties, except for the tax on tea. Adams urged colonists to keep up the boycott of British goods, arguing that paying even one small tax allowed Parliament to establish the precedent of taxing the colonies, but the boycott faltered. As economic conditions improved, support waned for Adams's causes. In 1770, New York City and Philadelphia abandoned the non-importation boycott of British goods and Boston merchants faced the risk of being economically ruined, so they also agreed to end the boycott, effectively defeating Adams's cause in Massachusetts. John Adams withdrew from politics, while John Hancock and James Otis appeared to become more moderate. In 1771, Samuel Adams ran for the position of Register of Deeds, but he was beaten byEzekiel Goldthwait

Ezekiel Goldthwait (July 19, 1710 – November 27, 1782) was an American merchant and landowner. Born in Boston, the capital of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, he rose to become on the city's leading citizens in the years leading to the Ameri ...

by more than two to one. He was re-elected to the Massachusetts House in April 1772, but he received far fewer votes than ever before.

A struggle over the

A struggle over the power of the purse

The power of the purse is the ability of one group to manipulate and control the actions of another group by withholding funding, or putting stipulations on the use of funds. The power of the purse can be used positively (e.g. awarding extra fun ...

brought Adams back into the political limelight. Traditionally, the Massachusetts House of Representatives paid the salaries of the governor, lieutenant governor, and superior court judges. From the Whig perspective, this arrangement was an important check on executive power, keeping royally appointed officials accountable to democratically elected representatives. In 1772, Massachusetts learned that those officials would henceforth be paid by the British government rather than by the province. To protest this, Adams and his colleagues devised a system of committees of correspondence

The committees of correspondence were, prior to the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, a collection of American political organizations that sought to coordinate opposition to British Parliament and, later, support for American independe ...

in November 1772; the towns of Massachusetts would consult with each other concerning political matters via messages sent through a network of committees that recorded British activities and protested imperial policies. Committees of correspondence soon formed in other colonies, as well.

Governor Hutchinson became concerned that the committees of correspondence were growing into an independence movement, so he convened the General Court in January 1773. Addressing the legislature, Hutchinson argued that denying the supremacy of Parliament, as some committees had done, came dangerously close to rebellion. "I know of no line that can be drawn", he said, "between the supreme authority of Parliament and the total independence of the colonies." Adams and the House responded that the Massachusetts Charter did not establish Parliament's supremacy over the province, and so Parliament could not claim that authority now. Hutchinson soon realized that he had made a major blunder by initiating a public debate about independence and the extent of Parliament's authority in the colonies. The Boston Committee of Correspondence published its statement of colonial rights, along with Hutchinson's exchange with the Massachusetts House, in the widely distributed " Boston Pamphlet".

The quiet period in Massachusetts was over. Adams was easily re-elected to the Massachusetts House in May 1773, and was also elected as moderator of the Boston Town Meeting. In June 1773, he introduced a set of private letters to the Massachusetts House, written by Hutchinson several years earlier. In one letter, Hutchinson recommended to London that there should be "an abridgement of what are called English liberties" in Massachusetts. Hutchinson denied that this is what he meant, but his career was effectively over in Massachusetts, and the House sent a petition asking the king to recall him.

Boston Tea Party

Adams took a leading role in the events that led up to the famousBoston Tea Party

The Boston Tea Party was an American political and mercantile protest by the Sons of Liberty in Boston, Massachusetts, on December 16, 1773. The target was the Tea Act of May 10, 1773, which allowed the British East India Company to sell t ...

of December 16, 1773, although the precise nature of his involvement has been disputed.

In May 1773, the British Parliament passed the Tea Act

The Tea Act 1773 (13 Geo 3 c 44) was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain. The principal objective was to reduce the massive amount of tea held by the financially troubled British East India Company in its London warehouses and to help th ...

, a tax law to help the struggling East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Southea ...

, one of Great Britain's most important commercial institutions. Britons could buy smuggled Dutch tea more cheaply than the East India Company's tea because of the heavy taxes imposed on tea imported into Great Britain, and so the company amassed a huge surplus of tea that it could not sell. The British government's solution to the problem was to sell the surplus in the colonies. The Tea Act permitted the East India Company to export tea directly to the colonies for the first time, bypassing most of the merchants who had previously acted as middlemen. This measure was a threat to the American colonial economy because it granted the Tea Company a significant cost advantage over local tea merchants and even local tea smugglers, driving them out of business. The act also reduced the taxes on tea paid by the company in Britain, but kept the controversial Townshend duty on tea imported in the colonies. A few merchants in New York, Philadelphia, Boston, and Charlestown were selected to receive the company's tea for resale. In late 1773, seven ships were sent to the colonies carrying East India Company tea, including four bound for Boston.

News of the Tea Act set off a firestorm of protest in the colonies. This was not a dispute about high taxes; the price of legally imported tea was actually reduced by the Tea Act. Protesters were instead concerned with a variety of other issues. The familiar "no taxation without representation

"No taxation without representation" is a political slogan that originated in the American Revolution, and which expressed one of the primary grievances of the American colonists for Great Britain. In short, many colonists believed that as they ...

" argument remained prominent, along with the question of the extent of Parliament's authority in the colonies. Some colonists worried that, by buying the cheaper tea, they would be conceding that Parliament had the right to tax them. The "power of the purse" conflict was still at issue. The tea tax revenues were to be used to pay the salaries of certain royal officials, making them independent of the people. Colonial smugglers played a significant role in the protests, since the Tea Act made legally imported tea cheaper, which threatened to put smugglers of Dutch tea out of business. Legitimate tea importers who had not been named as consignees by the East India Company were also threatened with financial ruin by the Tea Act and other merchants worried about the precedent of a government-created monopoly.

Adams and the correspondence committees promoted opposition to the Tea Act. In every colony except Massachusetts, protesters were able to force the tea consignees to resign or to return the tea to England. In Boston, however, Governor Hutchinson was determined to hold his ground. He convinced the tea consignees, two of whom were his sons, not to back down. The Boston Caucus and then the Town Meeting attempted to compel the consignees to resign, but they refused. With the tea ships about to arrive, Adams and the Boston Committee of Correspondence contacted nearby committees to rally support.

The tea ship ''Dartmouth'' arrived in the Boston Harbor in late November, and Adams wrote a circular letter calling for a mass meeting to be held at Faneuil Hall on November 29. Thousands of people arrived, so many that the meeting was moved to the larger

Adams and the correspondence committees promoted opposition to the Tea Act. In every colony except Massachusetts, protesters were able to force the tea consignees to resign or to return the tea to England. In Boston, however, Governor Hutchinson was determined to hold his ground. He convinced the tea consignees, two of whom were his sons, not to back down. The Boston Caucus and then the Town Meeting attempted to compel the consignees to resign, but they refused. With the tea ships about to arrive, Adams and the Boston Committee of Correspondence contacted nearby committees to rally support.

The tea ship ''Dartmouth'' arrived in the Boston Harbor in late November, and Adams wrote a circular letter calling for a mass meeting to be held at Faneuil Hall on November 29. Thousands of people arrived, so many that the meeting was moved to the larger Old South Meeting House

The Old South Meeting House is a historic Congregational church building located at the corner of Milk and Washington Streets in the Downtown Crossing area of Boston, Massachusetts, built in 1729. It gained fame as the organizing point for th ...

. British law required the ''Dartmouth'' to unload and pay the duties within twenty days or customs officials could confiscate the cargo. The mass meeting passed a resolution introduced by Adams urging the captain of the ''Dartmouth'' to send the ship back without paying the import duty. Meanwhile, the meeting assigned twenty-five men to watch the ship and prevent the tea from being unloaded.

Governor Hutchinson refused to grant permission for the ''Dartmouth'' to leave without paying the duty. Two more tea ships arrived in Boston Harbor, the ''Eleanor'' and the ''Beaver''. The fourth ship, the ''William'', was stranded near Cape Cod and never arrived to Boston. December 16 was the last day of the ''Dartmouth's'' deadline, and about 7,000 people gathered around the Old South Meeting House. Adams received a report that Governor Hutchinson had again refused to let the ships leave, and he announced, "This meeting can do nothing further to save the country." According to a popular story, Adams's statement was a prearranged signal for the "tea party" to begin. However, this claim did not appear in print until nearly a century after the event, in a biography of Adams written by his great-grandson, who apparently misinterpreted the evidence. According to eyewitness accounts, people did not leave the meeting until ten or fifteen minutes after Adams's alleged "signal", and Adams in fact tried to stop people from leaving because the meeting was not yet over.

While Adams tried to reassert control of the meeting, people poured out of the Old South Meeting House and headed to Boston Harbor. That evening, a group of 30 to 130 men boarded the three vessels, some of them thinly disguised as Mohawk Indians

The Mohawk people ( moh, Kanienʼkehá꞉ka) are the most easterly section of the Haudenosaunee, or Iroquois Confederacy. They are an Iroquoian-speaking Indigenous people of North America, with communities in southeastern Canada and northern Ne ...

, and dumped all 342 chests of tea into the water over the course of three hours. Adams never revealed whether he went to the wharf to witness the destruction of the tea. Whether or not he helped plan the event is unknown, but Adams immediately worked to publicize and defend it. He argued that the Tea Party was not the act of a lawless mob, but was instead a principled protest and the only remaining option that the people had to defend their constitutional rights.

Revolution

Great Britain responded to the Boston Tea Party in 1774 with theCoercive Acts

The Intolerable Acts were a series of punitive laws passed by the British Parliament in 1774 after the Boston Tea Party. The laws aimed to punish Massachusetts colonists for their defiance in the Tea Party protest of the Tea Act, a tax measure ...

. The first of these acts was the Boston Port Act, which closed Boston's commerce until the East India Company had been repaid for the destroyed tea. The Massachusetts Government Act

The Massachusetts Government Act (14 Geo. 3 c. 45) was passed by the Parliament of Great Britain, receiving royal assent on 20 May 1774. The act effectively abrogated the 1691 charter of the Province of Massachusetts Bay and gave its royally-appo ...

rewrote the Massachusetts Charter, making many officials royally appointed rather than elected, and severely restricting the activities of town meetings. The Administration of Justice Act

Administration of Justice Act (with its variations) is a stock short title used for legislation in the United Kingdom relating to the administration of justice.

The Bill for an Act with this short title may have been known as a Administration of J ...

allowed colonists charged with crimes to be transported to another colony or to Great Britain for trial. A new royal governor was appointed to enforce the acts: General Thomas Gage

General Thomas Gage (10 March 1718/192 April 1787) was a British Army general officer and colonial official best known for his many years of service in North America, including his role as British commander-in-chief in the early days of th ...

, who was also commander of British military forces in North America.

Adams worked to coordinate resistance to the Coercive Acts. In May 1774, the Boston Town Meeting (with Adams serving as moderator) organized an economic boycott of British goods. In June, Adams headed a committee in the Massachusetts House—with the doors locked to prevent Gage from dissolving the legislature—which proposed that an inter-colonial congress meet in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

in September. He was one of five delegates chosen to attend the First Continental Congress

The First Continental Congress was a meeting of delegates from 12 of the 13 British colonies that became the United States. It met from September 5 to October 26, 1774, at Carpenters' Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, after the British Navy ...

. Adams was never fashionably dressed and had little money, so friends bought him new clothes and paid his expenses for the journey to Philadelphia, his first trip outside of Massachusetts.

First Continental Congress

In Philadelphia, Adams promoted colonial unity while using his political skills to lobby other delegates. On September 16, messenger

In Philadelphia, Adams promoted colonial unity while using his political skills to lobby other delegates. On September 16, messenger Paul Revere

Paul Revere (; December 21, 1734 O.S. (January 1, 1735 N.S.)May 10, 1818) was an American silversmith, engraver, early industrialist, Sons of Liberty member, and Patriot and Founding Father. He is best known for his midnight ride to a ...

brought Congress the Suffolk Resolves, one of many resolutions passed in Massachusetts that promised strident resistance to the Coercive Acts. Congress endorsed the Suffolk Resolves, issued a Declaration of Rights that denied Parliament's right to legislate for the colonies, and organized a colonial boycott known as the Continental Association

The Continental Association, also known as the Articles of Association or simply the Association, was an agreement among the American colonies adopted by the First Continental Congress on October 20, 1774. It called for a trade boycott against ...

.

Adams returned to Massachusetts in November 1774, where he served in the Massachusetts Provincial Congress

The Massachusetts Provincial Congress (1774–1780) was a provisional government created in the Province of Massachusetts Bay early in the American Revolution. Based on the terms of the colonial charter, it exercised ''de facto'' control over the ...

, an extralegal legislative body independent of British control. The Provincial Congress created the first minutemen companies, consisting of militiamen who were to be ready for action on a moment's notice. Adams also served as moderator of the Boston Town Meeting, which convened despite the Massachusetts Government Act, and was appointed to the Committee of Inspection to enforce the Continental Association. He was also selected to attend the Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress was a late-18th-century meeting of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolutionary War. The Congress was creating a new country it first named "United Colonies" and in 1 ...

, scheduled to meet in Philadelphia in May 1775.

John Hancock had been added to the delegation, and he and Adams attended the Provincial Congress in Concord, Massachusetts

Concord () is a town in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, in the United States. At the 2020 census, the town population was 18,491. The United States Census Bureau considers Concord part of Greater Boston. The town center is near where the conflu ...

, before Adams's journey to the second Congress. The two men decided that it was not safe to return to Boston before leaving for Philadelphia, so they stayed at Hancock's childhood home in Lexington. On April 14, 1775, General Gage received a letter from Lord Dartmouth

Earl of Dartmouth is a title in the Peerage of Great Britain. It was created in 1711 for William Legge, 1st Earl of Dartmouth, William Legge, 2nd Baron Dartmouth.

History

The Legge family descended from Edward Legge, Vice-President of Munster. ...

advising him "to arrest the principal actors and abettors in the Provincial Congress whose proceedings appear in every light to be acts of treason and rebellion". On the night of April 18, Gage sent out a detachment of soldiers on the fateful mission that sparked the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. The purpose of the British expedition was to seize and destroy military supplies that the colonists had stored in Concord. According to many historical accounts, Gage also instructed his men to arrest Hancock and Adams, but the written orders issued by Gage made no mention of arresting the Patriot leaders. Gage had evidently decided against seizing Adams and Hancock, but Patriots initially believed otherwise, perhaps influenced by London newspapers that reached Boston with the news that the patriot leader would be hanged if he were caught. From Boston, Joseph Warren

Joseph Warren (June 11, 1741 – June 17, 1775), a Founding Father of the United States, was an American physician who was one of the most important figures in the Patriot movement in Boston during the early days of the American Revolution, ...

dispatched Paul Revere to warn the two that British troops were on the move and might attempt to arrest them. As Hancock and Adams made their escape, the first shots of the war began at Lexington and Concord

The Battles of Lexington and Concord were the first military engagements of the American Revolutionary War. The battles were fought on April 19, 1775, in Middlesex County, Province of Massachusetts Bay, within the towns of Lexington, Concord ...

. Soon after the battle, Gage issued a proclamation granting a general pardon to all who would "lay down their arms, and return to the duties of peaceable subjects"—with the exceptions of Hancock and Samuel Adams. Singling out Hancock and Adams in this manner only added to their renown among Patriots and, according to Patriot historian Mercy Otis Warren

Mercy Otis Warren (September 14, eptember 25, New Style1728 – October 19, 1814) was an American activist poet, playwright, and pamphleteer during the American Revolution. During the years before the Revolution, she had published poems and pla ...

, perhaps exaggerated the importance of the two men.

Second Continental Congress

The Continental Congress worked under a secrecy rule, so Adams's precise role in congressional deliberations is not fully documented. He appears to have had a major influence, working behind the scenes as a sort of "

The Continental Congress worked under a secrecy rule, so Adams's precise role in congressional deliberations is not fully documented. He appears to have had a major influence, working behind the scenes as a sort of "parliamentary whip

A whip is an official of a political party whose task is to ensure party discipline in a legislature. This means ensuring that members of the party vote according to the party platform, rather than according to their own individual ideology ...

" and Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

credits Samuel Adams—the lesser-remembered Adams—with steering the Congress toward independence, saying, "If there was any Palinurus

Palinurus (''Palinūrus''), in Roman mythology and especially Virgil's ''Aeneid'', is the coxswain of Aeneas' ship. Later authors used him as a general type of navigator or guide. Palinurus is an example of human sacrifice; his life is the price ...

to the Revolution, Samuel Adams was the man." He served on numerous committees, often dealing with military matters. Among his more noted acts, Adams nominated George Washington to be commander in chief over the Continental Army.