Salim Ali on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sálim Moizuddin Abdul Ali (12 November 1896 – 20 June 1987) was an Indian

ornithologist

Ornithology is a branch of zoology that concerns the "methodological study and consequent knowledge of birds with all that relates to them." Several aspects of ornithology differ from related disciplines, due partly to the high visibility and th ...

and naturalist. Sometimes referred to as the "''Birdman of India''", Salim Ali was the first Indian to conduct systematic bird surveys across India and wrote several bird books that popularized ornithology

Ornithology is a branch of zoology that concerns the "methodological study and consequent knowledge of birds with all that relates to them." Several aspects of ornithology differ from related disciplines, due partly to the high visibility and t ...

in India. He became a key figure behind the Bombay Natural History Society

The Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS), founded on 15 September 1883, is one of the largest non-governmental organisations in India engaged in conservation and biodiversity research. It supports many research efforts through grants and publ ...

after 1947 and used his personal influence to garner government support for the organisation, create the Bharatpur bird sanctuary (Keoladeo National Park

Keoladeo National Park or Keoladeo Ghana National Park (formerly known as the Bharatpur Bird Sanctuary) is a famous avifauna sanctuary in Bharatpur, Rajasthan, India, that hosts thousands of birds, especially during the winter season. Over 350 ...

) and prevent the destruction of what is now the Silent Valley National Park.

Along with Sidney Dillon Ripley

Sidney Dillon Ripley II (September 20, 1913 – March 12, 2001) was an American ornithologist and wildlife conservationist. He served as secretary of the Smithsonian Institution for 20 years, from 1964 to 1984, leading the institution throu ...

he wrote the landmark ten volume '' Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan'', a second edition of which was completed after his death. He was awarded the Padma Bhushan

The Padma Bhushan is the third-highest civilian award in the Republic of India, preceded by the Bharat Ratna and the Padma Vibhushan and followed by the Padma Shri. Instituted on 2 January 1954, the award is given for "distinguished service ...

in 1958 and the Padma Vibhushan

The Padma Vibhushan ("Lotus Decoration") is the second-highest civilian award of the Republic of India, after the Bharat Ratna. Instituted on 2 January 1954, the award is given for "exceptional and distinguished service". All persons without ...

in 1976, India's third and second highest civilian honours respectively. Several species of birds, Salim Ali's fruit bat

Salim Ali's fruit bat (''Latidens salimalii'') is a rare megabat species in the monotypic genus ''Latidens''. It was first collected by Angus Hutton, a planter and naturalist in the High Wavy Mountains in the Western Ghats of Theni district, ...

, a couple of bird sanctuaries and institutions have been named after him.

Early life

Salim Ali was born into aSulaimani Bohra

The Sulaymani branch of Tayyibi Isma'ilism is an Islamic community, of which around 70,000 members reside in Yemen, while a few thousand Sulaymani Bohras can be found in India. The Sulaymanis are sometimes headed by a ''Da'i al-Mutlaq'' from th ...

family in Bombay, the ninth and youngest child of Moizuddin Tyabji. His father died when he was a year old and his mother Zeenat-un-nissa died when he was three. Along with his siblings, Ali was brought up by his maternal uncle, Amiruddin Tyabji, and childless aunt, Hamida Begum, in a middle-class household in Khetwadi, Mumbai. Another uncle was Abbas Tyabji

Abbas Tyabji (1 February 1854 – 9 June 1936) was an Indian freedom fighter from Gujarat, and an associate of Mahatma Gandhi. He also served as the Chief Justice of Baroda State. His grandson is historian Irfan Habib.

Family and background

Ab ...

, a well known Indian freedom fighter. Ali's early interest was in books on hunting in India and he became the most interested in sport-shooting

Shooting sports is a group of competitive and recreational sporting activities involving proficiency tests of accuracy, precision and speed in shooting — the art of using ranged weapons, mainly small arms (firearms and airguns, in forms such as ...

, encouraged by his foster-father Amiruddin. Shooting contests were often held in the neighbourhood in which he grew and his playmates included Iskandar Mirza, a distant cousin who was a particularly good marksman and went on in later life to become the first President of Pakistan

The president of Pakistan ( ur, , translit=s̤adr-i Pākiṣṭān), officially the President of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, is the ceremonial head of state of Pakistan and the commander-in-chief of the Pakistan Armed Forces.W. S. Millard, secretary of the

Salim Ali's early education was at

Salim Ali's early education was at  Ali failed to get an ornithologist's position which was open at the

Ali failed to get an ornithologist's position which was open at the

Ali was not very interested in the details of bird systematics and taxonomy and was more interested in studying birds in the field.

Ali was not very interested in the details of bird systematics and taxonomy and was more interested in studying birds in the field.

Salim Ali was very influential in ensuring the survival of the BNHS and managed to save the then 100-year-old institution by writing to the then Prime Minister Pandit Nehru for financial help. Salim also influenced other members of his family. A cousin,

Salim Ali was very influential in ensuring the survival of the BNHS and managed to save the then 100-year-old institution by writing to the then Prime Minister Pandit Nehru for financial help. Salim also influenced other members of his family. A cousin,

Although recognition came late, he received several honorary doctorates and numerous awards. The earliest was the "Joy Gobinda Law Gold Medal" in 1953, awarded by the

Although recognition came late, he received several honorary doctorates and numerous awards. The earliest was the "Joy Gobinda Law Gold Medal" in 1953, awarded by the  Dr. Salim Ali died in Bombay at the age of 90 on 20 June 1987, after a protracted battle with

Dr. Salim Ali died in Bombay at the age of 90 on 20 June 1987, after a protracted battle with

alternate scan

* * *

1974 Indian Government documentary – In the company of birds (1974)

Commentary with recordings from the All India Radio archives

Interview Part 1Part 2

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ali, Salim Indian ornithologists 1896 births 1987 deaths Deaths from prostate cancer Indian autobiographers Recipients of the Padma Bhushan in science & engineering Recipients of the Padma Vibhushan in science & engineering Nominated members of the Rajya Sabha Indian Ismailis Sulaymani Bohras Naturalists of British India Indian environmentalists 20th-century Indian zoologists Deaths from cancer in India Members of the Bombay Natural History Society Tyabji family

Bombay Natural History Society

The Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS), founded on 15 September 1883, is one of the largest non-governmental organisations in India engaged in conservation and biodiversity research. It supports many research efforts through grants and publ ...

(BNHS) where Amiruddin was a member, who identified an unusually coloured sparrow that young Salim had shot for sport with his toy air gun. Millard identified it as a yellow-throated sparrow, and showed Salim around the Society's collection of stuffed birds. Millard lent Salim a few books including Eha's ''Common birds of Bombay'', encouraged Salim to make a collection of birds and offered to train him in skinning and preservation. Millard later introduced young Salim to (later Sir) Norman Boyd Kinnear, the first paid curator at the BNHS, who later supported Ali from his position in the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

. In his autobiography, ''The Fall of a Sparrow'', Ali notes the yellow-throated sparrow event as a turning point in his life, one that led him into ornithology, an unusual career choice, especially for an Indian in those days. Even at around 10 years of age, he maintained a diary and among his earliest bird notes were observations on the replacement of males in paired sparrows after he had shot down the male.

Salim went to primary school at Zenana Bible and Medical Mission Girls High School at Girgaum along with two of his sisters and later to St. Xavier's College, Bombay

St. Xavier's College is a private, Catholic, autonomous higher education institution run by the

Bombay Province of the Society of Jesus in Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. It was founded by the Jesuits on January 2, 1869. The college is affili ...

. Around the age of 13 he suffered from chronic headaches, making him drop out of class frequently. He was sent to Sind

Sindh (; ; ur, , ; historically romanized as Sind) is one of the four provinces of Pakistan. Located in the southeastern region of the country, Sindh is the third-largest province of Pakistan by land area and the second-largest province ...

to stay with an uncle who had suggested that the dry air might help and on returning after such breaks in studies, he barely managed to pass the matriculation exam of the Bombay University

The University of Mumbai is a collegiate, state-owned, public research university in Mumbai.

The University of Mumbai is one of the largest universities in the world. , the university had 711 affiliated colleges. Ratan Tata is the appointed ...

in 1913.

Burma and Germany

Salim Ali's early education was at

Salim Ali's early education was at St. Xavier's College, Mumbai

St. Xavier's College is a private, Catholic, autonomous higher education institution run by the

Bombay Province of the Society of Jesus in Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. It was founded by the Jesuits on January 2, 1869. The college is aff ...

. Following a difficult first year in college, he dropped out and went to Tavoy

Dawei (, ; mnw, ဓဝဲါ, ; th, ทวาย, RTGS: ''Thawai'', ; formerly known as Tavoy) is a city in south-eastern Myanmar and is the capital of the Tanintharyi Region, formerly known as the Tenasserim Division, on the northern bank of ...

, Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

(Tenasserim) to look after the family's wolfram (tungsten) mining (tungsten was used in armour plating and was valuable during the war) and timber interests there. The forests surrounding this area provided an opportunity for Ali to hone his naturalist and hunting skills. He also made acquaintance with J C Hopwood and Berthold Ribbentrop

Berthold Ribbentrop was a pioneering forester from Germany who worked in India with Sir Dietrich Brandis and others. He is said to have inspired Rudyard Kipling's character of Muller in ''In the Rukh'' (1893), one of the earliest of his ''Jungle ...

who were with the Forest Service in Burma. On his return to India in 1917, he decided to continue formal studies. He went to study commercial law and accountancy at Davar's College of Commerce but his true interest was noticed by Father Ethelbert Blatter

Ethelbert Blatter Society of Jesus, SJ (15 December 1877 – 26 May 1934) was a Swiss people, Swiss Jesuit priest and pioneering botanist in British India. Author of five books and over sixty papers on the flora of the Indian subcontinent, he was ...

at St. Xavier's College who persuaded Ali to study zoology. After attending morning classes at Davar's College, he then began to attend zoology classes at St. Xavier's College and was able to complete the course in zoology. Around the same time, he married Tehmina, a distant relative, in December 1918.

Ali was fascinated by motorcycles from an early age and starting with a 3.5 HP NSU in Tavoy, he owned a Sunbeam, Harley-Davidson

Harley-Davidson, Inc. (H-D, or simply Harley) is an American motorcycle manufacturer headquartered in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, United States. Founded in 1903, it is one of two major American motorcycle manufacturers to survive the Great Depressi ...

s (three models), a Douglas

Douglas may refer to:

People

* Douglas (given name)

* Douglas (surname)

Animals

*Douglas (parrot), macaw that starred as the parrot ''Rosalinda'' in Pippi Longstocking

*Douglas the camel, a camel in the Confederate Army in the American Civil W ...

, a Scott, a New Hudson and a Zenith

The zenith (, ) is an imaginary point directly "above" a particular location, on the celestial sphere. "Above" means in the vertical direction (plumb line) opposite to the gravity direction at that location (nadir). The zenith is the "highest" ...

among others at various times. On invitation to the 1950 International Ornithological Congress

International is an adjective (also used as a noun) meaning "between nations".

International may also refer to:

Music Albums

* ''International'' (Kevin Michael album), 2011

* ''International'' (New Order album), 2002

* ''International'' (The T ...

at Uppsala

Uppsala (, or all ending in , ; archaically spelled ''Upsala'') is the county seat of Uppsala County and the List of urban areas in Sweden by population, fourth-largest city in Sweden, after Stockholm, Gothenburg, and Malmö. It had 177,074 inha ...

in Sweden he shipped his Sunbeam aboard the SS ''Stratheden'' from Bombay and biked around Europe, injuring himself in a minor mishap in France apart from having several falls on cobbled roads in Germany. When he arrived on a fully loaded bike, just in time for the first session at Uppsala, word went around that he had ridden all the way from India! He regretted not having owned a BMW.

Ali failed to get an ornithologist's position which was open at the

Ali failed to get an ornithologist's position which was open at the Zoological Survey of India

The Zoological Survey of India (ZSI), founded on 1 July 1916 by Government of India Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, as premier Indian organisation in zoological research and studies to promote the survey, exploration and r ...

due to the lack of a formal university degree and the post went instead to M. L. Roonwal. He was hired as guide lecturer in 1926 at the newly opened natural history section in the Prince of Wales Museum

Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya, (CSMVS) originally named Prince of Wales Museum of Western India, is a museum in Mumbai (Bombay) which documents the history of India from prehistoric to modern times.

It was founded during Briti ...

in Mumbai with a salary of Rs 350 per month. He however tired of the job after two years and took leave in 1928 to study in Germany, where he was to work under Professor Erwin Stresemann

Erwin Friedrich Theodor Stresemann (22 November 1889, in Dresden – 20 November 1972, in East Berlin) was a German naturalist and ornithologist. Stresemann was an ornithologist of extensive breadth who compiled one of the first and most compreh ...

at the Berlin's Natural History Museum. Part of the work involved studying the specimens collected by J. K. Stanford in Burma. Stanford being a BNHS member had communicated with Claud Ticehurst and had suggested that he could work on his own with assistance from the BNHS. Ticehurst did not appreciate the idea of an Indian being involved in the work and resented even more, the involvement of Stresemann, a German. Ticehurst wrote letters to the BNHS suggesting that the idea of collaborating with Stresemann was an insult to Stanford. This was however not heeded by Reginald Spence and Prater who encouraged Ali to conduct the studies at Berlin with the assistance of Stresemann. Ali found Stresemann warm and helpful right from his first letters sent before even meeting him. In his autobiography, Ali calls Stresemann his ''guru'', to whom all his later queries went. In Berlin, Ali made acquaintance with many of the major German ornithologists of the time including Bernhard Rensch

Bernhard Rensch (21 January 1900 – 4 April 1990) was a German evolutionary biologist and ornithologist who did field work in Indonesia and India. Starting his scientific career with pro-Lamarckian views, he shifted to selectionism and became ...

, Oskar Heinroth

Oskar Heinroth (1 March 1871 – 31 May 1945) was a German biologist who was one of the first to apply the methods of comparative morphology to animal behavior, and was thus one of the founders of ethology. He worked, largely isolated from mos ...

, Rudolf Drost Rudolf Karl Theodor Drost (19 August 1892, Oldenburg - 3 December 1971, Wilhelmshaven) was a German ornithologist best known for his studies on bird migration conducted at the Heligoland observatory.

Drost was the only child of Dr Karl Drost and Cl ...

and Ernst Mayr

Ernst Walter Mayr (; 5 July 1904 – 3 February 2005) was one of the 20th century's leading evolutionary biologists. He was also a renowned Taxonomy (biology), taxonomist, tropical explorer, ornithologist, Philosophy of biology, philosopher o ...

apart from meeting other Indians in Berlin including the revolutionary Chempakaraman Pillai

Chempakaraman Pillai, alias Venkidi, (15 September 1891 – 26 May 1934) was an Indian-born political activist and revolutionary. Born in Thiruvananthapuram, to Tamil Pillai parents, he left for Europe as a youth, where he spent the rest of hi ...

. Ali also gained experience in bird ringing

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweight ...

at the Heligoland Bird Observatory and in 1959 he received the assistance of Swiss ornithologist Alfred Schifferli in India.

Ornithology

On his return to India in 1930, he discovered that the guide lecturer position had been eliminated due to lack of funds. Unable to find a suitable job, Salim Ali and Tehmina moved toKihim

Kihim is a small village located to the north of Alibag. Commonly known to people in Mumbai as a weekend getaway, it is accessible via Road and Water. It forms part of the string of beach hamlets along the coast of Alibag taluka collectively ...

, a coastal village near Mumbai. Here he had the opportunity to study at close hand, the breeding of the baya weaver

The baya weaver (''Ploceus philippinus'') is a weaverbird found across the Indian Subcontinent and Southeast Asia. of these birds are found in grasslands, cultivated areas, scrub and secondary growth and they are best known for their hanging ret ...

and discovered their mating system

A mating system is a way in which a group is structured in relation to sexual behaviour. The precise meaning depends upon the context. With respect to animals, the term describes which males and females mating, mate under which circumstances. Reco ...

of sequential polygamy. Later commentators have suggested that this study was in the tradition of the Mughal naturalists that Salim Ali admired and wrote about in three-part series on the Moghul emperors as naturalists. A few months were then spent in Kotagiri where he had been invited by K.M. Anantan, a retired army doctor who had served in Mesopotamia during World War I. He also came in contact with Mrs Kinloch, widow of BNHS member Angus Kinloch who lived at Donnington near Longwood Shola, and later her son-in-law R C Morris, who lived in the Biligirirangan Hills. Around the same time he discovered an opportunity to conduct systematic bird surveys in the princely states

A princely state (also called native state or Indian state) was a nominally sovereign entity of the British Indian Empire that was not directly governed by the British, but rather by an Indian ruler under a form of indirect rule, subject to ...

of Hyderabad

Hyderabad ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Indian state of Telangana and the ''de jure'' capital of Andhra Pradesh. It occupies on the Deccan Plateau along the banks of the Musi River (India), Musi River, in the northern part ...

, Cochin

Kochi (), also known as Cochin ( ) ( the official name until 1996) is a major port city on the Malabar Coast of India bordering the Laccadive Sea, which is a part of the Arabian Sea. It is part of the district of Ernakulam in the state of K ...

, Travancore

The Kingdom of Travancore ( /ˈtrævənkɔːr/), also known as the Kingdom of Thiruvithamkoor, was an Indian kingdom from c. 1729 until 1949. It was ruled by the Travancore Royal Family from Padmanabhapuram, and later Thiruvananthapuram. At ...

, Gwalior

Gwalior() is a major city in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh; it lies in northern part of Madhya Pradesh and is one of the Counter-magnet cities. Located south of Delhi, the capital city of India, from Agra and from Bhopal, the s ...

, Indore

Indore () is the largest and most populous Cities in India, city in the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh. It serves as the headquarters of both Indore District and Indore Division. It is also considered as an education hub of the state and is t ...

and Bhopal

Bhopal (; ) is the capital city of the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh and the administrative headquarters of both Bhopal district and Bhopal division. It is known as the ''City of Lakes'' due to its various natural and artificial lakes. It i ...

with the sponsorship of their rulers. He was aided and supported in these surveys by Hugh Whistler

Hugh Whistler (28 September 1889 – 7 July 1943), F.Z.S., M.B.O.U. was an English police officer and ornithologist who worked in India. He wrote one of the first field guides to Indian birds and documented the distributions of birds in notes in ...

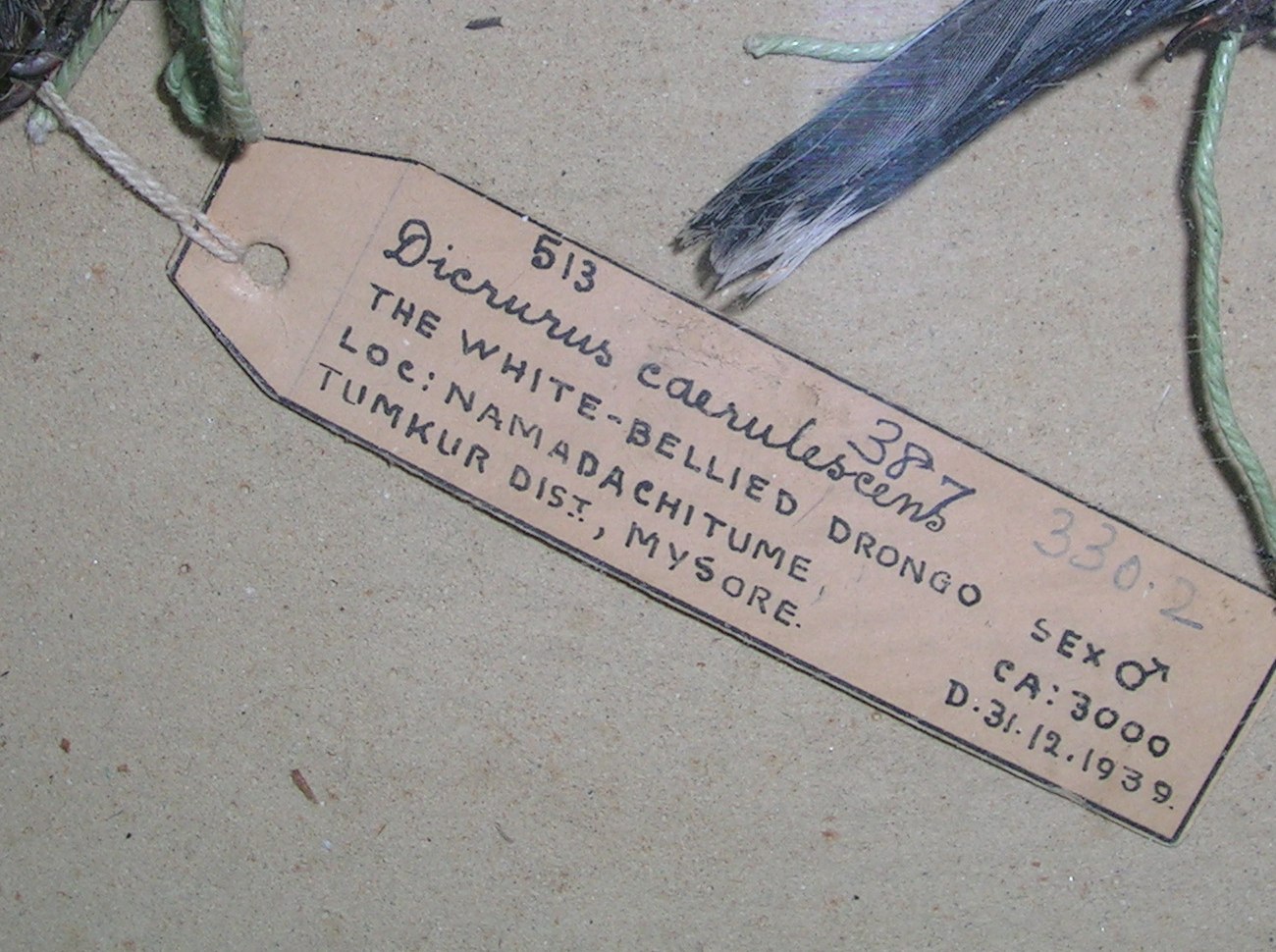

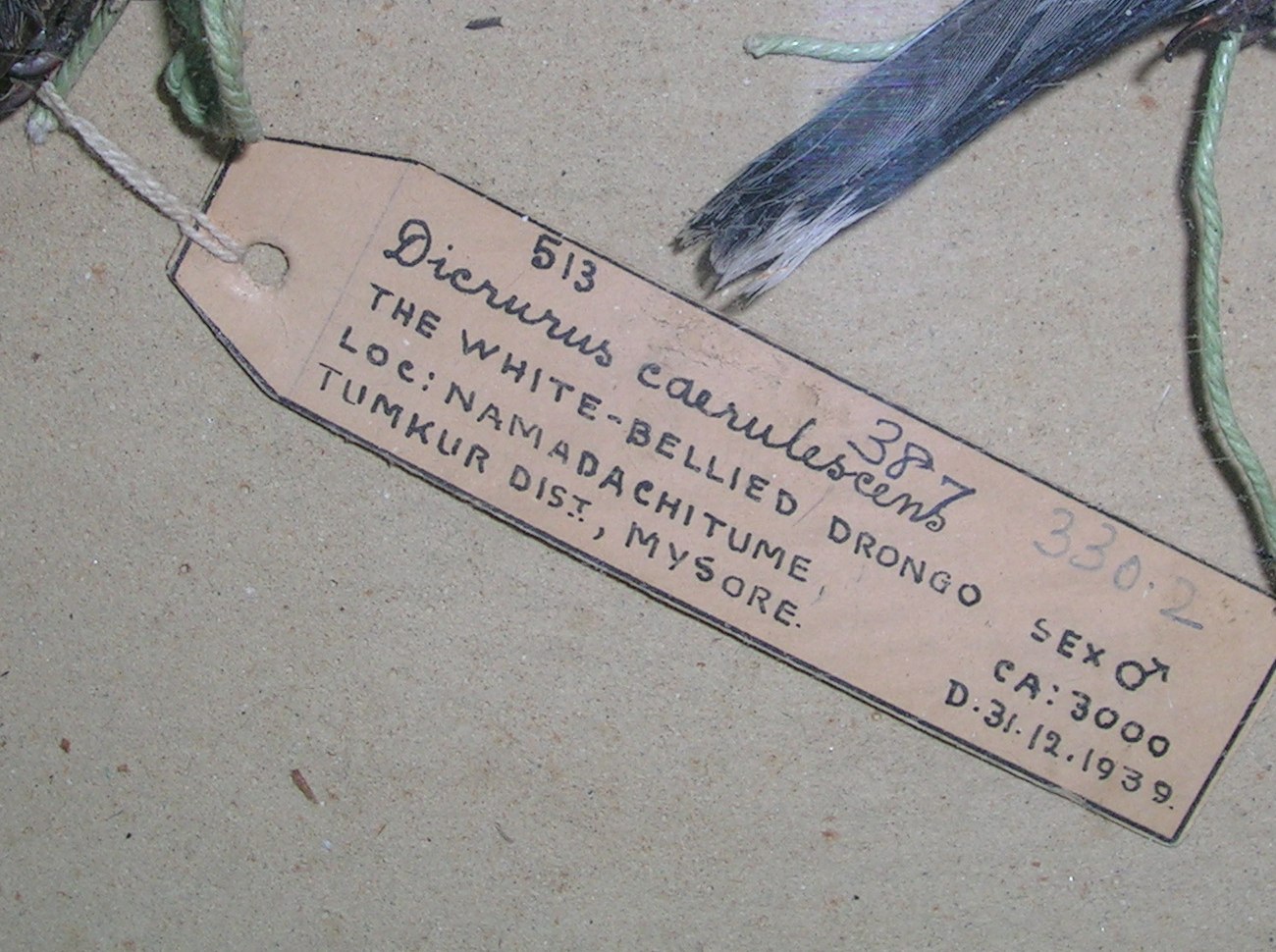

who had surveyed many parts of India and had kept very careful notes. Whistler published a note on ''The study of Indian birds'' in 1929 where he mentioned that the racquets at the end of the long tail feathers of the greater racket-tailed drongo

The greater racket-tailed drongo (''Dicrurus paradiseus'') is a medium-sized Asian bird which is distinctive in having elongated outer tail feathers with webbing restricted to the tips. They are placed along with other drongos in the family Dic ...

lacked webbing on the inner vane. Salim Ali wrote a response pointing out that this was in error and that such inaccuracies had been carried on from early literature and pointed out that it was incorrect observation that did not take into account a twist in the rachis. Whistler was initially resentful of an unknown Indian finding fault and wrote "snooty" letters to the editors of the journal S H Prater and Sir Reginald Spence. Subsequently, Whistler re-examined his specimens and not only admitted his error but became a close friend. Whistler wrote to Ali on 24 October 1938:

:''It has been a very great benefit to me that we drifted into collaboration largely in its beginning as an accident-when you pointed out my mistake over the webs of Drongo's tail feather-and the mistake has proved to me well worth while. And here and now I must thank you very warmly for making my collaboration a condition of your undertaking the Mysore and Sunderbans surveys.''

Whistler also introduced Salim to Richard Meinertzhagen

Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen, CBE, DSO (3 March 1878 – 17 June 1967) was a British soldier, intelligence officer, and ornithologist. He had a decorated military career spanning Africa and the Middle East. He was credited with creating and e ...

and the two made an expedition into Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

. Although Meinertzhagen had very critical views of him they became good friends. Salim Ali found nothing amiss in Meinertzhagen's bird works but later studies have shown many of his studies to be fraudulent. Meinertzhagen made his diary entries from their days in the field available and Salim Ali reproduces them in his autobiography:

He was accompanied and supported on his early surveys by his wife, Tehmina, and was shattered when she died in 1939 following a minor surgery. After Tehmina's death in 1939, Salim Ali stayed with his sister Kamoo and brother-in-law. In the course of his later travels, Ali rediscovered the Kumaon Kumaon or Kumaun may refer to:

* Kumaon division, a region in Uttarakhand, India

* Kumaon Kingdom, a former country in Uttarakhand, India

* Kumaon, Iran, a village in Isfahan Province, Iran

* , a ship of the Royal Indian Navy during WWII

See also

...

Terai

The Terai or Tarai is a lowland region in northern India and southern Nepal that lies south of the outer foothills of the Himalayas, the Sivalik Hills, and north of the Indo-Gangetic Plain. This lowland belt is characterised by tall grasslands, scr ...

population of the Finn's baya but was unsuccessful in his expedition to find the mountain quail

The mountain quail (''Oreortyx pictus'') is a small ground-dwelling bird in the New World quail family. This species is the only one in the genus ''Oreortyx'', which is sometimes included in ''Callipepla''. This is not appropriate, however, as t ...

(''Ophrysia superciliosa''), the status of which continues to remain unknown.

Ali was not very interested in the details of bird systematics and taxonomy and was more interested in studying birds in the field.

Ali was not very interested in the details of bird systematics and taxonomy and was more interested in studying birds in the field. Ernst Mayr

Ernst Walter Mayr (; 5 July 1904 – 3 February 2005) was one of the 20th century's leading evolutionary biologists. He was also a renowned Taxonomy (biology), taxonomist, tropical explorer, ornithologist, Philosophy of biology, philosopher o ...

wrote to Ripley complaining that Ali failed to collect sufficient specimens : "as far as collecting is concerned I don't think he ever understood the necessity for collecting series. Maybe you can convince him of that." Ali himself wrote to Ripley complaining about bird taxonomy:

Ali later wrote that his interest was in the "living bird in its natural environment."

Salim Ali's associations with Sidney Dillon Ripley

Sidney Dillon Ripley II (September 20, 1913 – March 12, 2001) was an American ornithologist and wildlife conservationist. He served as secretary of the Smithsonian Institution for 20 years, from 1964 to 1984, leading the institution throu ...

led to many bureaucratic problems. Ripley's past as an OSS agent led to allegations that the CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian intelligence agency, foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gat ...

had a hand in the bird-ringing operations in India.

Salim Ali took some interest in bird photography along with his friend Loke Wan Tho

Tan Sri Loke Wan Tho (; Pha̍k-fa-sṳ: ''Lu̍k Yun-thàu''; 14 June 1915 – 20 June 1964) was a Malaysian-Singaporean business magnate, ornithologist, and photographer. He was the founder of Cathay Organisation in Singapore and Malaysia, ...

. Loke had been introduced to Ali by J.T.M. Gibson, a BNHS member and Lieutenant Commander of the Royal Indian Navy

The Royal Indian Navy (RIN) was the naval force of British India and the Dominion of India. Along with the Presidency armies, later the Indian Army, and from 1932 the Royal Indian Air Force, it was one of the Armed Forces of British India.

Fr ...

, who had taught English to Loke at a school in Switzerland. A wealthy Singapore businessman with a keen interest in birds, Loke helped Ali and the BNHS with financial support. Ali was also interested in the historical aspects of ornithology in India. In a series of articles, among his first publications, he examined the contributions to natural-history of the Mughal emperors

The Mughal emperors ( fa, , Pādishāhān) were the supreme heads of state of the Mughal Empire on the Indian subcontinent, mainly corresponding to the modern countries of India, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh. The Mughal rulers styled t ...

. In the 1971 Sunder Lal Hora memorial lecture and the 1978 Azad Memorial Lecture he spoke of the history and importance of bird study in India. Towards the end of his life, he began to document the lives of people in the history of the Bombay Natural History Society but did not complete the series with only four parts published.

Other contributions

Salim Ali was very influential in ensuring the survival of the BNHS and managed to save the then 100-year-old institution by writing to the then Prime Minister Pandit Nehru for financial help. Salim also influenced other members of his family. A cousin,

Salim Ali was very influential in ensuring the survival of the BNHS and managed to save the then 100-year-old institution by writing to the then Prime Minister Pandit Nehru for financial help. Salim also influenced other members of his family. A cousin, Humayun Abdulali

Humayun Abdulali (19 May 1914, Kobe, Japan - 3 June 2001, Mumbai, India) was an Indian ornithologist and biologist who was also a cousin of the "birdman of India", Salim Ali (ornithologist), Salim Ali. Like other naturalists of his period, he to ...

became an ornithologist while his niece Laeeq took an interest in birds and was married to Zafar Futehally

Zafar Rashid Futehally (19 March 1920 – 11 August 2013) was an Indian naturalist and conservationist best known for his work as the secretary of the Bombay Natural History Society and for the ''Newsletter for Birdwatchers'' a periodical that ...

, a distant cousin of Ali, who went on to become the honorary Secretary of the BNHS and played a major role in the development of bird study through the networking of birdwatchers in India. A grand-nephew Shahid Ali also took an interest in ornithology. Ali also guided several MSc and PhD students, the first of whom was Vijaykumar Ambedkar, who further studied the breeding and ecology of the baya weaver, producing a thesis that was favourably reviewed by David Lack

David Lambert Lack FRS (16 July 1910 – 12 March 1973) was a British evolutionary biologist who made contributions to ornithology, ecology, and ethology. His 1947 book, ''Darwin's Finches'', on the finches of the Galapagos Islands was a landm ...

.

Ali was able to provide support for the development of ornithology in India by identifying important areas where funding could be obtained. He helped in the establishment of an economic ornithology unit within the Indian Council for Agricultural Research

The Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) is an autonomous body responsible for co-ordinating agricultural education and research in India. It reports to the Department of Agricultural Research and Education, Ministry of Agriculture. Th ...

in the mid-1960s although he failed to gain support for a similar proposal in 1935. He was also able to obtain funding for migration studies through a project to study the Kyasanur forest disease, an arthropod-borne virus that appeared to have similarities to a Siberian tick-borne disease. This project partly funded by the PL 480 grants of the USA however ran into political difficulties with allegations made on CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian intelligence agency, foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gat ...

involvement. The funding for the early bird migration studies actually came for the early studies from the US Army Medical Research Laboratory in Bangkok under the SEATO (South Atlantic Security Pact) and headed by H. Elliott McClure. An Indian science reporter wrote in a local newspaper that the collaboration was secretly exploring the use of migratory birds for spreading deadly viruses and microbes into enemy territories. India was then a non-aligned country and the news led to political upheaval and a committee was set up to examine the research and allegations. Once cleared of these allegations, the project however stopped routing the funds through Bangkok to avoid further suspicions and was directly funded by the Americans to India. In the late 1980s, Ali also headed a BNHS project to reduce bird hits

A bird strike—sometimes called birdstrike, bird ingestion (for an engine), bird hit, or bird aircraft strike hazard (BASH)—is a collision between an airborne animal (usually a bird or bat) and a moving vehicle, usually an aircraft. The term ...

at Indian airfields. He also attempted a citizen science

Citizen science (CS) (similar to community science, crowd science, crowd-sourced science, civic science, participatory monitoring, or volunteer monitoring) is scientific research conducted with participation from the public (who are sometimes re ...

project to study house sparrow

The house sparrow (''Passer domesticus'') is a bird of the sparrow family Passeridae, found in most parts of the world. It is a small bird that has a typical length of and a mass of . Females and young birds are coloured pale brown and grey, a ...

s in 1963 through Indian birdwatchers subscribed to the ''Newsletter for Birdwatchers

''Newsletter for Birdwatchers'' is an Indian periodical of ornithology and birdwatching founded in 1960 by Zafar Futehally, who edited it until 2003. It was initially mimeographed and distributed to a small number of subscribers each month. It is ...

''.

Ali had considerable influence in conservation related issues in post-independence India especially through Prime Ministers Jawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20t ...

and Indira Gandhi

Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi (; Given name, ''née'' Nehru; 19 November 1917 – 31 October 1984) was an Indian politician and a central figure of the Indian National Congress. She was elected as third prime minister of India in 1966 ...

. Indira Gandhi, herself a keen birdwatcher, was influenced by Ali's bird books (a copy of the ''Book of Indian Birds

''The Book of Indian Birds'' by Salim Ali is a landmark book on Indian ornithology, which helped spark popular interest in the birds of India.

First published in 1941, it is currently in its 13th edition. Most of the older books on Indian birds we ...

'' was gifted to her in 1942 by her father Nehru who was in Dehra Dun

Dehradun () is the capital and the most populous city of the Indian state of Uttarakhand. It is the administrative headquarters of the eponymous district and is governed by the Dehradun Municipal Corporation, with the Uttarakhand Legislativ ...

jail while she herself was imprisoned in Naini Jail) and by the Gandhian birdwatcher Horace Alexander. Ali influenced the designation of the Bharatpur Bird Sanctuary, the Ranganathittu Bird Sanctuary

Ranganathittu Bird Sanctuary (also known as ''Pakshi Kashi of Karnataka''), is a bird sanctuary in the Mandya District of the state of Karnataka in India. It is the largest bird sanctuary in the state, in area, and comprises six islets on the b ...

and in decisions that saved the Silent Valley National Park. One of Ali's later interventions at Bharatpur involved the exclusion of cattle and graziers from the sanctuary and this was to prove costly as it resulted in ecological changes that led to a decline in the waterbirds. Some historians have noted that the approach to conservation used by Salim Ali and the BNHS followed an undemocratic process.

Ali lived for some time with his brother Hamid Ali (1880-1965) who had retired in 1934 from the Indian Civil Service and settled at Southwood, ancestral home of his father in law, Abbas Tyabji

Abbas Tyabji (1 February 1854 – 9 June 1936) was an Indian freedom fighter from Gujarat, and an associate of Mahatma Gandhi. He also served as the Chief Justice of Baroda State. His grandson is historian Irfan Habib.

Family and background

Ab ...

, in Mussoorie. During this period Ali became a close friend of Arthur Foot

Arthur Edward Foot Order of the British Empire, CBE (more commonly A.E. Foot) (21 June 1901 – 26 September 1968), was an English schoolmaster, educationalist and academic. He was a science master at Eton College from 1923 to 1932. In 1935, h ...

, principal of The Doon School

The Doon School (informally Doon School or Doon) is a selective all-boys boarding school in Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India, which was established in 1935. It was envisioned by Satish Ranjan Das, a lawyer from Calcutta, who prevised a school mode ...

and his wife Sylvia (referred to jocularly by Ali as the "Feet"). He visited the school often and was an engaging and persuasive advocate of ornithology to successive generations of pupils. As a consequence, he was considered to be part of the Dosco fraternity and became one of the very few people to be made an honorary member of ''The Doon School Old Boys Society''.

Personal views

Salim Ali held many views that were contrary to the mainstream ideas of his time. A question he was asked frequently in later life was on the contradiction between the collection of bird specimens and his conservation related activism. Although once a fan of ''shikar'' (hunting) literature, Ali held strong views against sport hunting but upheld the collection of bird specimens for scientific study. He held the view that the practice of wildlife conservation needed to be practical and not grounded in philosophies like ''ahimsa

Ahimsa (, IAST: ''ahiṃsā'', ) is the ancient Indian principle of nonviolence which applies to all living beings. It is a key virtue in most Indian religions: Jainism, Buddhism, and Hinduism.Bajpai, Shiva (2011). The History of India � ...

''. Salim Ali suggested that this fundamental religious sentiment had hindered the growth of bird study in India.

In the early 1960s, the national bird

This is a list of national birds, including official birds of overseas territories and other states described as nations. Most species in the list are officially designated. Some species hold only an "unofficial" status.

National birds

See al ...

of India was under consideration and Salim Ali was intent that it should be the endangered Great Indian bustard

The great Indian bustard (''Ardeotis nigriceps'') or Indian bustard, is a bustard found on the Indian subcontinent. A large bird with a horizontal body and long bare legs, giving it an ostrich like appearance, this bird is among the heaviest of t ...

, however this proposal was over-ruled in favour of the Indian peacock

The Indian peafowl (''Pavo cristatus''), also known as the common peafowl, and blue peafowl, is a peafowl species native to the Indian subcontinent. It has been introduced to many other countries. Male peafowl are referred to as peacocks, and ...

.

Ali was known for his frugal lifestyle, with money saved at the end of many of his projects. Shoddy jobs by people around him could make him very angry. He discouraged smoking and drinking and detested people who snored in their sleep.

Honours and memorials

Although recognition came late, he received several honorary doctorates and numerous awards. The earliest was the "Joy Gobinda Law Gold Medal" in 1953, awarded by the

Although recognition came late, he received several honorary doctorates and numerous awards. The earliest was the "Joy Gobinda Law Gold Medal" in 1953, awarded by the Asiatic Society of Bengal

The Asiatic Society is a government of India organisation founded during the Company rule in India to enhance and further the cause of "Oriental research", in this case, research into India and the surrounding regions. It was founded by the p ...

based on an appraisal of his work by Sunder Lal Hora

Sunder Lal Hora (22 May 1896 – 8 December 1955) was an Indian ichthyologist known for his biogeographic theory on the affinities of Western Ghats and Indomalayan fish forms.

Life

Hora was born at Hafizabad in the Punjab (modern day Pa ...

(and in 1970 he received the Sunder Lal Hora memorial Medal of the Indian National Science Academy

The Indian National Science Academy (INSA) is a national academy in New Delhi for Indian scientists in all branches of science and technology.

In August 2019, Dr. Chandrima Shaha was appointed as the president of Indian National Science Academ ...

). He received honorary doctorates from the Aligarh Muslim University

Aligarh Muslim University (abbreviated as AMU) is a Public University, public Central University (India), central university in Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, India, which was originally established by Sir Syed Ahmad Khan as the Muhammadan Anglo-Orie ...

(1958), Delhi University

Delhi University (DU), formally the University of Delhi, is a collegiate university, collegiate Central university (India), central university located in New Delhi, India. It was founded in 1922 by an Act of the Central Legislative Assembly and ...

(1973) and Andhra University

Andhra University (IAST: ''Āndhra Vișvakalāpariṣhat'') is a public university located in Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh, India. It was established in 1926.

History

King Vikram Deo Verma, the Maharaja of Jeypore was one of the biggest do ...

(1978). In 1967 he became the first non-British citizen to receive the Gold Medal of the British Ornithologists' Union

The British Ornithologists' Union (BOU) aims to encourage the study of birds ("ornithology") and around the world, in order to understand their biology and to aid their conservation. The BOU was founded in 1858 by Professor Alfred Newton, Henry ...

. In the same year, he received the J. Paul Getty Wildlife Conservation Prize consisting of a sum of $100,000, which he used as a corpus for the Salim Ali Nature Conservation Fund. In 1969 he received the John C. Phillips memorial medal of the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN; officially International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natu ...

. The USSR Academy of Medical Sciences The USSR Academy of Medical Sciences (russian: Акаде́мия медици́нских нау́к СССР) was the highest scientific and medical organization founded in the Soviet Union founded in 1944.

Its successor is the Russian Academy of ...

awarded him the Pavlovsky Centenary Memorial Medal in 1973 and in the same year he was made Commander of the Netherlands Order of the Golden Ark

The Most Excellent Order of the Golden Ark ( nl, Orde van de Gouden Ark) is a Dutch order of merit established in 1971 by Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands. It is awarded to people for major contributions to nature conservation. Although not ...

by Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands

A prince is a male ruler (ranked below a king, grand prince, and grand duke) or a male member of a monarch's or former monarch's family. ''Prince'' is also a title of nobility (often highest), often hereditary, in some European states. ...

. The Indian government decorated him with a ''Padma Bhushan

The Padma Bhushan is the third-highest civilian award in the Republic of India, preceded by the Bharat Ratna and the Padma Vibhushan and followed by the Padma Shri. Instituted on 2 January 1954, the award is given for "distinguished service ...

'' in 1958 and the ''Padma Vibhushan

The Padma Vibhushan ("Lotus Decoration") is the second-highest civilian award of the Republic of India, after the Bharat Ratna. Instituted on 2 January 1954, the award is given for "exceptional and distinguished service". All persons without ...

'' in 1976. He was nominated to the Rajya Sabha

The Rajya Sabha, constitutionally the Council of States, is the upper house of the bicameral Parliament of India. , it has a maximum membership of 245, of which 233 are elected by the legislatures of the states and union territories using si ...

in 1985.

Dr. Salim Ali died in Bombay at the age of 90 on 20 June 1987, after a protracted battle with

Dr. Salim Ali died in Bombay at the age of 90 on 20 June 1987, after a protracted battle with prostate cancer

Prostate cancer is cancer of the prostate. Prostate cancer is the second most common cancerous tumor worldwide and is the fifth leading cause of cancer-related mortality among men. The prostate is a gland in the male reproductive system that sur ...

. In 1990, the Sálim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History (SACON) was established at Coimbatore

Coimbatore, also spelt as Koyamputhur (), sometimes shortened as Kovai (), is one of the major metropolitan cities in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. It is located on the banks of the Noyyal River and surrounded by the Western Ghats. Coimbato ...

by the Government of India

The Government of India (ISO: ; often abbreviated as GoI), known as the Union Government or Central Government but often simply as the Centre, is the national government of the Republic of India, a federal democracy located in South Asia, c ...

. Pondicherry University established the Salim Ali School of Ecology and Environmental Sciences. The government of Goa set up the Salim Ali Bird Sanctuary and the Thattakad bird sanctuary near Vembanad

Vembanad is the longest lake in India, as well as the largest lake in the state of Kerala. The lake has an area of 230 square kilometers and a maximum length of 96.5 km. Spanning several districts in the state of Kerala, it is known as Ve ...

in Kerala also goes by his name. The location of the BNHS headquarters in Mumbai was renamed as "Dr Salim Ali Chowk". In 1972, Kitti Thonglongya

Kitti Thonglongya (, October 6, 1928 - February 12, 1974) was an eminent Thailand, Thai ornithologist and mammalogy, mammalogist. He is probably best known for two discoveries of endangered species.

Life

Thonglongya was born in Bangkok and gradua ...

discovered a misidentified specimen in the collection of the BNHS and described a new species that he called ''Latidens salimalii

Salim Ali's fruit bat (''Latidens salimalii'') is a rare megabat species in the monotypic genus ''Latidens''. It was first collected by Angus Hutton, a planter and naturalist in the High Wavy Mountains in the Western Ghats of Theni district, ...

'', considered one of the world's rarest bat

Bats are mammals of the order Chiroptera.''cheir'', "hand" and πτερόν''pteron'', "wing". With their forelimbs adapted as wings, they are the only mammals capable of true and sustained flight. Bats are more agile in flight than most ...

s, and the only species in the genus ''Latidens

Salim Ali's fruit bat (''Latidens salimalii'') is a rare megabat species in the monotypic genus ''Latidens''. It was first collected by Angus Hutton, a planter and naturalist in the High Wavy Mountains in the Western Ghats of Theni district, ...

''. The subspecies of the rock bush quail

The rock bush quail (''Perdicula argoondah'') is a species of quail found in parts of peninsular India. It is a common species with a wide range and the IUCN has rated it as being of "least concern".

Taxonomy and systematics

There are three r ...

(''Perdicula argoondah salimalii'') and the eastern population of Finn's weaver

Finn's weaver (''Ploceus megarhynchus''), also known as Finn's baya and yellow weaver is a weaver bird species native to the Ganges and Brahmaputra valleys in India and Nepal. Two subspecies are known; the nominate subspecies occurs in the Kumao ...

(''Ploceus megarhynchus salimalii'') were named after him by Whistler and Abdulali respectively. A subspecies of the black-rumped flameback woodpecker ( ''Dinopium benghalense tehminae'') was named after his wife, Tehmina, by Whistler and Kinnear. Salim Ali's swift

Salim Ali's swift (''Apus salimalii'') is a small bird, superficially similar to a house martin. It is, however, completely unrelated to those passerine species, since swifts are in the order Apodiformes. The resemblances between the groups are ...

(''Apus salimalii'') originally described as a population of ''Apus pacificus'' was recognised as a full species in 2011 while '' Zoothera salimalii'', an undescribed population within the '' Zoothera mollissima'' complex, was named after him in 2016.

On his 100th birth Anniversary (12 November 1996) Postal Department of Government of India released a set of two postal stamps.

Writings

Salim Ali wrote numerous journal articles, chiefly in the ''Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society

The ''Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society'' (also ''JBNHS'') is a natural history journal published several times a year by the Bombay Natural History Society. First published in January 1886, and published with only a few interruptio ...

''. He also wrote a number of popular and academic books, many of which remain in print. Ali credited Tehmina, who had studied in England, for helping improve his English prose. Some of his literary pieces were used in a collection of English writing. A popular article that he wrote in 1930 ''Stopping by the woods on a Sunday morning'' was reprinted in ''The Indian Express

''The Indian Express'' is an English-language Indian daily newspaper founded in 1932. It is published in Mumbai by the Indian Express Group. In 1999, eight years after the group's founder Ramnath Goenka's death in 1991, the group was split betw ...

'' on his birthday in 1984. His most popular work was ''The Book of Indian Birds'', written in the style of Whistler's ''Popular Handbook of Birds'', first published in 1941 and subsequently translated into several languages with numerous later editions. The first ten editions sold more than forty-six thousand copies. The first edition was reviewed by Ernst Mayr

Ernst Walter Mayr (; 5 July 1904 – 3 February 2005) was one of the 20th century's leading evolutionary biologists. He was also a renowned Taxonomy (biology), taxonomist, tropical explorer, ornithologist, Philosophy of biology, philosopher o ...

in 1943, who commended it while noting that the illustrations were not to the standard of American bird-books. His ''magnum opus'' was however the 10 volume '' Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan'' written with Dillon Ripley and often referred to as "''the handbook''". This work began in 1964 and ended in 1974 with a second edition completed after his death by others, notably J. S. Serrao of the BNHS, Bruce Beehler

Bruce M. Beehler (born October 11, 1951, in Baltimore) is an ornithologist and research associate of the Bird Division of the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History. Prior to this appointment, Beehler worked for Conservation ...

, Michel Desfayes and Pamela Rasmussen

Pamela Cecile Rasmussen (born October 16, 1959) is an American ornithologist and expert on Asian birds. She was formerly a research associate at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., and is based at the Michigan State University. Sh ...

. A single volume ''compact edition'' of the ''Handbook'' was also produced and a supplementary illustrative work, the first to cover all the birds of India, ''A Pictorial Guide to the Birds of the Indian Subcontinent'', by John Henry Dick

John Henry Dick (May 12, 1919 – September 22, 1995) was an American naturalist and wildlife artist who specialized in birds.

Early life

Dick was born in at his parents' townhouse in Brooklyn, New York on May 12, 1919. His parents were William K ...

and Dillon Ripley was published in 1983. The plates from this work were incorporated in the second edition of the ''Handbook''. He also produced a number of regional field guides, including ''The Birds of Kerala

Kerala ( ; ) is a state on the Malabar Coast of India. It was formed on 1 November 1956, following the passage of the States Reorganisation Act, by combining Malayalam-speaking regions of the erstwhile regions of Cochin, Malabar, South ...

'' (the first edition in 1953 was titled ''The Birds of Travancore and Cochin''), ''The Birds of Sikkim

Sikkim (; ) is a state in Northeastern India. It borders the Tibet Autonomous Region of China in the north and northeast, Bhutan in the east, Province No. 1 of Nepal in the west and West Bengal in the south. Sikkim is also close to the Siligur ...

'', ''The Birds of Kutch'' (later as ''The Birds of Gujarat

Gujarat (, ) is a state along the western coast of India. Its coastline of about is the longest in the country, most of which lies on the Kathiawar peninsula. Gujarat is the fifth-largest Indian state by area, covering some ; and the ninth ...

''), ''Indian Hill Birds'' and ''Birds of the Eastern Himalayas

The Himalayas, or Himalaya (; ; ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the planet's highest peaks, including the very highest, Mount Everest. Over 100 ...

''. Several low-cost book were produced by the National Book Trust

National Book Trust (NBT) is an Indian publishing house, which was founded in 1957 as an autonomous body under the Ministry of Education of the Government of India. The activities of the Trust include publishing, promotion of books and reading, ...

including ''Common Birds'' (1967) coauthored with his niece Laeeq Futehally which was reprinted in several editions with translations into Hindi and other languages. In 1985 he wrote his autobiography ''The Fall of a Sparrow''. Ali provided his own vision for the Bombay Natural History Society

The Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS), founded on 15 September 1883, is one of the largest non-governmental organisations in India engaged in conservation and biodiversity research. It supports many research efforts through grants and publ ...

, noting the importance of conservation action. In the 1986 issue of the ''Journal'' ''of the BNHS'' he noted the role that the BNHS had played, the changing interests from hunting to conservation captured in 64 volumes that were preserved in microfiche copies, and the zenith that he claimed it had reached under the exceptional editorship of S H Prater.

A two-volume compilation of his shorter letters and writings was published in 2006, edited by Tara Gandhi, one of his last students. She also edited a collection of transcripts of radio talks given by Salim Ali, which was published in 2021.

References

;Autobiography * Ali, Salim (1985) ''The Fall of a Sparrow''.Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the university press of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world, and its printing history dates back to the 1480s. Having been officially granted the legal right to print books ...

.

External links

* * *alternate scan

* * *

1974 Indian Government documentary – In the company of birds (1974)

Commentary with recordings from the All India Radio archives

Interview Part 1

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ali, Salim Indian ornithologists 1896 births 1987 deaths Deaths from prostate cancer Indian autobiographers Recipients of the Padma Bhushan in science & engineering Recipients of the Padma Vibhushan in science & engineering Nominated members of the Rajya Sabha Indian Ismailis Sulaymani Bohras Naturalists of British India Indian environmentalists 20th-century Indian zoologists Deaths from cancer in India Members of the Bombay Natural History Society Tyabji family