SS President Arthur on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

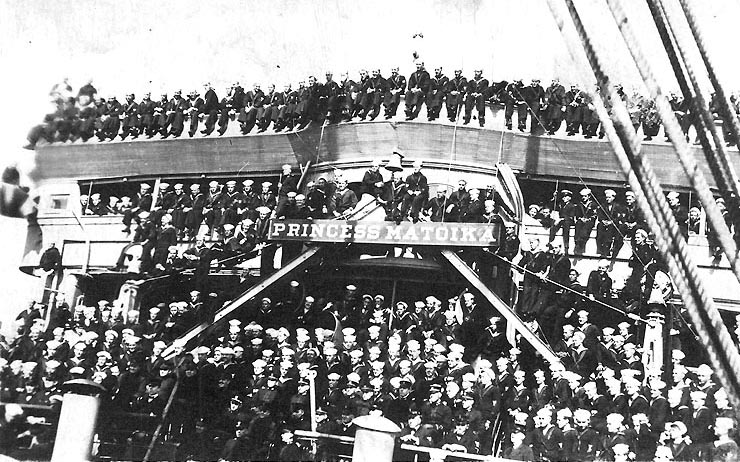

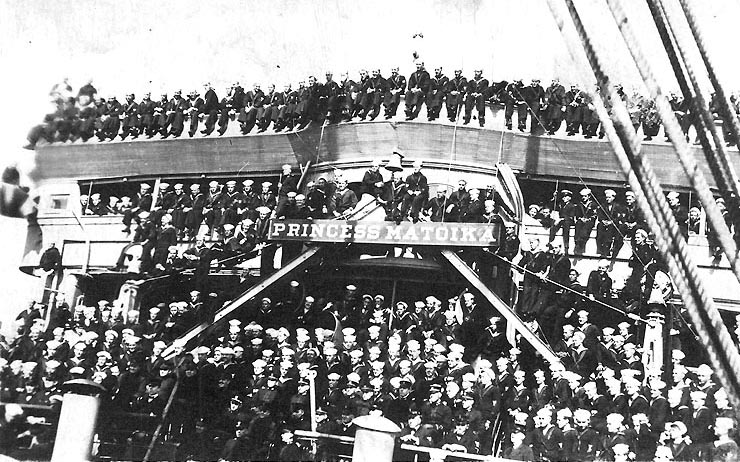

USS ''Princess Matoika'' (ID-2290) was a transport ship for the

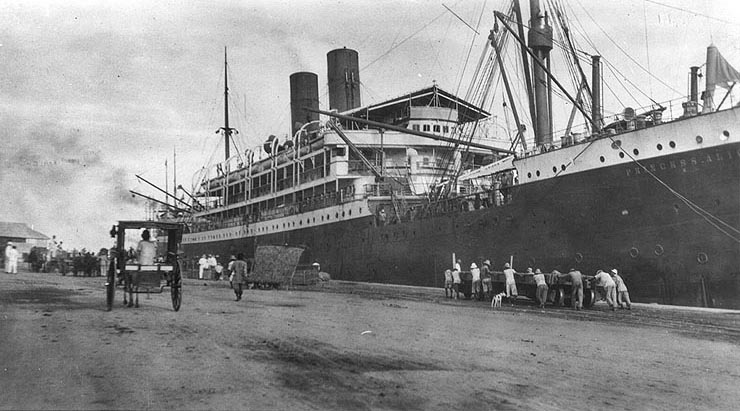

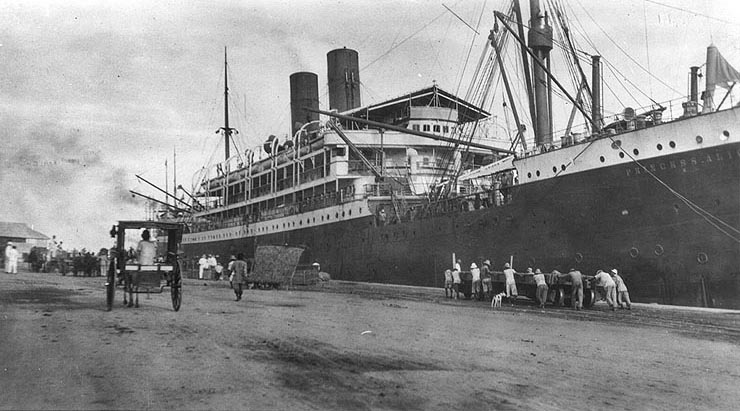

''Princess Alice'' departed her new homeport of

''Princess Alice'' departed her new homeport of  In May 1910, ''Princess Alice'' sailed her last North Atlantic passage for her German owners. Put permanently on the Far East route, she plied Pacific waters for North German Lloyd until the outbreak of World War I. In late July 1914, as war spread across Europe, ''Princess Alice'' neared her destination of Hong Kong with £850,000 of gold from

In May 1910, ''Princess Alice'' sailed her last North Atlantic passage for her German owners. Put permanently on the Far East route, she plied Pacific waters for North German Lloyd until the outbreak of World War I. In late July 1914, as war spread across Europe, ''Princess Alice'' neared her destination of Hong Kong with £850,000 of gold from

After loading officers and men from the 29th Infantry Division on 13 June, ''Princess Matoika'' set sail from Newport News the next day with ''Wilhelmina'', ''Pastores'', ''Lenape'', and British troopship . On the morning of 16 June, lookouts on ''Princess Matoika'' spotted a submarine and, soon after, a torpedo heading directly for the ship. The torpedo missed her by a few yards and gunners manning the ship's guns claimed a hit on the sub with their second shot.Cutchins and Stewart, p. 66. Later that morning, the Newport News ships met up with the New York portion of the convoy—which included , , , , ''Covington'', ''Rijndam'', ''Dante Alighieri'', and British steamer ''Vauben''—and set out for France.Cutchins and Stewart, p. 67.Crowell and Wilson, p. 610–11. The convoy was escorted by cruisers and ''Frederick'', and

After loading officers and men from the 29th Infantry Division on 13 June, ''Princess Matoika'' set sail from Newport News the next day with ''Wilhelmina'', ''Pastores'', ''Lenape'', and British troopship . On the morning of 16 June, lookouts on ''Princess Matoika'' spotted a submarine and, soon after, a torpedo heading directly for the ship. The torpedo missed her by a few yards and gunners manning the ship's guns claimed a hit on the sub with their second shot.Cutchins and Stewart, p. 66. Later that morning, the Newport News ships met up with the New York portion of the convoy—which included , , , , ''Covington'', ''Rijndam'', ''Dante Alighieri'', and British steamer ''Vauben''—and set out for France.Cutchins and Stewart, p. 67.Crowell and Wilson, p. 610–11. The convoy was escorted by cruisers and ''Frederick'', and  Around this time, Commander Leahy left ''Princess Matoika'' to serve as Director of Gunnery Exercises and Engineering Performance in Washington. For his service on ''Princess Matoika'', though, Leahy was awarded the

Around this time, Commander Leahy left ''Princess Matoika'' to serve as Director of Gunnery Exercises and Engineering Performance in Washington. For his service on ''Princess Matoika'', though, Leahy was awarded the

In May 1920 ''Princess Matoika'' took on board the bodies of ten female nurses and over 400 soldiers who died while on duty in France during the war. The ship then transited the

In May 1920 ''Princess Matoika'' took on board the bodies of ten female nurses and over 400 soldiers who died while on duty in France during the war. The ship then transited the

After four Bremen roundtrips for United States Lines, ''Princess Matoika'' had sailed her last voyage under that name. When newly built Type 535 vessels named for American presidents came into service for the company in May 1922, the ''Princess'' was renamed SS ''President Arthur'' in honor of the 21st

After four Bremen roundtrips for United States Lines, ''Princess Matoika'' had sailed her last voyage under that name. When newly built Type 535 vessels named for American presidents came into service for the company in May 1922, the ''Princess'' was renamed SS ''President Arthur'' in honor of the 21st

On 9 October 1924, the newly formed American Palestine Line announced that it had purchased ''President Arthur'' from the USSB, with plans to inaugurate service between New York and

On 9 October 1924, the newly formed American Palestine Line announced that it had purchased ''President Arthur'' from the USSB, with plans to inaugurate service between New York and

Maritime Timetable Images

) Throughout her career, ''City of Honolulu'' transported many notable passengers to Hawaii. In July 1927, for example, ''City of Honolulu'' also carried notable visitors to the

''City of Honolulu'' also carried notable visitors to the

Photo of the water tank

used by 1920 Olympians on the deck of USAT ''Princess Matoika'' * SS ''President Arthur'' *

Sheet music cover

of "President Arthur's Zion Ship" {{DEFAULTSORT:Princess Matoika Barbarossa-class ocean liners Ships of Norddeutscher Lloyd Ships of the Hamburg America Line Ships of the United States Lines Transport ships of the United States Army Transports of the United States Navy World War I auxiliary ships of the United States Maritime incidents in 1920 Maritime incidents in 1930 1900 ships Ships built in Stettin

United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

during World War I. Before the war, she was a that sailed as SS ''Kiautschou'' for the Hamburg America Line

The Hamburg-Amerikanische Packetfahrt-Aktien-Gesellschaft (HAPAG), known in English as the Hamburg America Line, was a transatlantic shipping enterprise established in Hamburg, in 1847. Among those involved in its development were prominent citi ...

and as SS ''Princess Alice'' (sometimes spelled ''Prinzess Alice'') for North German Lloyd

Norddeutscher Lloyd (NDL; North German Lloyd) was a German shipping company. It was founded by Hermann Henrich Meier and Eduard Crüsemann in Bremen on 20 February 1857. It developed into one of the most important German shipping companies of t ...

. After her World War I Navy service ended, she served as the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

transport ship USAT ''Princess Matoika''. In post-war civilian service she was SS ''Princess Matoika'' until 1922, SS ''President Arthur'' until 1927, and SS ''City of Honolulu'' until she was scrapped in 1933.

Built in 1900 for the German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

Far East mail routes, SS ''Kiautschou'' traveled between Hamburg and Far East ports for most of her Hamburg America Line career. In 1904, she was traded to competitor North German Lloyd for five freighters, and renamed SS ''Princess Alice''. She sailed both transatlantic and Far East mail routes until the outbreak of World War I, when she was interned in the neutral port of Cebu

Cebu (; ceb, Sugbo), officially the Province of Cebu ( ceb, Lalawigan sa Sugbo; tl, Lalawigan ng Cebu; hil, Kapuroan sang Sugbo), is a province of the Philippines located in the Central Visayas region, and consists of a main island and 167 ...

in the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

. Seized by the U.S. in 1917, the newly renamed USS ''Princess Matoika'' carried over 50,000 U.S. troops to and from France in U.S. Navy service from 1918 to 1919. As an Army transport after that, she continued to return troops and repatriated the remains of Americans killed overseas in the war. In July 1920, she was a last-minute substitute to carry a large portion of the United States team to the 1920 Summer Olympics

The 1920 Summer Olympics (french: Jeux olympiques d'été de 1920; nl, Olympische Zomerspelen van 1920; german: Olympische Sommerspiele 1920), officially known as the Games of the VII Olympiad (french: Jeux de la VIIe olympiade; nl, Spelen van ...

in Antwerp. From the perspective of the Olympic team, the trip was disastrous and a majority of the team members published a list of grievances and demands of the American Olympic Committee

The United States Olympic & Paralympic Committee (USOPC) is the National Olympic Committee and the National Paralympic Committee for the United States. It was founded in 1895 as the United States Olympic Committee, and is headquartered in C ...

in an action known today as the Mutiny of the ''Matoika''.

After her Army career ended, ''Princess Matoika'' was transferred to the United States Mail Steamship Line for European passenger service in early 1921. After that company's financial troubles resulted in her seizure, ''Princess Matoika'' was assigned to the newly formed United States Lines

United States Lines was the trade name of an organization of the United States Shipping Board (USSB), Emergency Fleet Corporation (EFC) created to operate German liners seized by the United States in 1917. The ships were owned by the USSB and all ...

and resumed passenger service. In 1922, the ship was renamed SS ''President Arthur'', in honor of the 21st U.S. President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

, Chester A. Arthur

Chester Alan Arthur (October 5, 1829 – November 18, 1886) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 21st president of the United States from 1881 to 1885. He previously served as the 20th vice president under President James A ...

. When changes in U.S. laws severely curtailed the number of immigrants that could enter the country in the early 1920s, the ship was laid up in Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

in late 1923.

''President Arthur'' was purchased in October 1924 by the Jewish-owned American Palestine Line to begin regular service between New York, Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

, and Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

. On her maiden voyage to Palestine, she reportedly became the first ocean liner to fly the Zionist flag at sea and the first ocean liner ever to have female officers. Financial difficulties for American Palestine ended the service after three roundtrips, and the liner was sold to the Los Angeles Steamship Company

The Los Angeles Steamship Company or LASSCO was a passenger and freight shipping company based in Los Angeles, California.

Description

The company, formed in 1920, initially provided fast passenger service between Los Angeles and San Francisco. I ...

for Los Angeles–Honolulu

Honolulu (; ) is the capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, which is in the Pacific Ocean. It is an unincorporated county seat of the consolidated City and County of Honolulu, situated along the southeast coast of the island ...

service. Following three years of carrying tourists and freight, the liner burned in Honolulu Harbor

Honolulu Harbor, also called ''Kulolia'' and ''Ke Awa O Kou'' and the Port of Honolulu , is the principal seaport of Honolulu and the State of Hawaii in the United States. From the harbor, the City & County of Honolulu was developed and urbanized ...

in 1930. She was deemed too expensive to repair and was eventually scrapped in Japan in 1933.

Hamburg America Line

In March 1900 theHamburg America Line

The Hamburg-Amerikanische Packetfahrt-Aktien-Gesellschaft (HAPAG), known in English as the Hamburg America Line, was a transatlantic shipping enterprise established in Hamburg, in 1847. Among those involved in its development were prominent citi ...

(German: Hamburg-Amerikanische Packetfahrt-Aktien-Gesellschaft or HAPAG) announced the plans for 22 new ships totaling at a cost of $11,000,000. One of the two largest ships announced was SS ''Kiautschou'' at an announced . The ship was laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

at AG Vulcan Stettin

Aktien-Gesellschaft Vulcan Stettin (short AG Vulcan Stettin) was a German shipbuilding and locomotive building company. Founded in 1851, it was located near the former eastern German city of Stettin, today Polish Szczecin. Because of the limited ...

in Stettin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin language, Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital city, capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the Po ...

, Germany (present-day Szczecin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the German border, it is a major s ...

, Poland). During her construction, HAPAG renamed the ship twice before finally settling on Kiautschou

The Jiaozhou Bay (; german: Kiautschou Bucht, ) is a bay located in the prefecture-level city of Qingdao (Tsingtau), China.

The bay has historically been romanized as Kiaochow, Kiauchau or Kiao-Chau in English language, English and Kiautschou ...

, the German colony in China, as her namesake. Built, along with sister ship , for HAPAG's entry into the Deutsche Reichspost's Far East routes, ''Kiautschou'' was launched on 14 September 1900, and sailed on her maiden voyage from Hamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

to the Far East on 22 December 1900.Bonsor, Vol. 1, p. 408.

The ship was long and featured twin screws powered by two quadruple expansion steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be trans ...

s that generated . The liner also featured bilge keel

A bilge keel is a nautical device used to reduce a ship's tendency to roll. Bilge keels are employed in pairs (one for each side of the ship). A ship may have more than one bilge keel per side, but this is rare. Bilge keels increase hydrodynamic re ...

s that helped stabilize her ride. On the interior, ''Kiautschou''s first-class staterooms were described as "light and large" and located in the center of the ship. She had two large promenade deck

The promenade deck is a deck found on several types of passenger ships and riverboats. It usually extends from bow to stern, on both sides, and includes areas open to the outside, resulting in a continuous outside walkway suitable for ''promena ...

s, a music room, and a library. Her smoking room

A smoking room (or smoking lounge) is a room which is specifically provided and furnished for smoking, generally in buildings where smoking is otherwise prohibited.

Locations and facilities

Smoking rooms can be found in public buildings such ...

was at the rear of the upper promenade deck, and her large dining room featured a balcony where the ship's orchestra could serenade diners.

''Kiautschou'' sailed on the Hamburg–Far East route until May 1902. For one round trip that month, ''Kiautschou'' replaced fellow HAPAG steamer on Hamburg–New York service, calling at Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

and Cherbourg

Cherbourg (; , , ), nrf, Chèrbourg, ) is a former commune and subprefecture located at the northern end of the Cotentin peninsula in the northwestern French department of Manche. It was merged into the commune of Cherbourg-Octeville on 28 Feb ...

on her eastbound trip, and at Cherbourg and Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth ...

on her westbound return. After this one transatlantic excursion, ''Kiautschou'' was returned to Hamburg–Far East service. On 20 February 1904, in exchange for abandoning the mail routes shared with North German Lloyd

Norddeutscher Lloyd (NDL; North German Lloyd) was a German shipping company. It was founded by Hermann Henrich Meier and Eduard Crüsemann in Bremen on 20 February 1857. It developed into one of the most important German shipping companies of t ...

, HAPAG traded ''Kiautschou'' for Lloyd freighters ''Bamberg'', ''Königsberg'', ''Nürnberg'', ''Stolberg'', and ''Strassburg''.

North German Lloyd

North German Lloyd renamed the newly acquired ship ''Princess Alice'', though the German spelling ''Prinzess Alice'' was widely used in contemporary press coverage and, often, by the Lloyd themselves. There is some confusion as to who exactly was the namesake of the ship. Edwin Drechsel, in his two-volume work ''Norddeutscher Lloyd, Bremen, 1857–1970'', reports that the ship was named equally forPrincess Alice of Albany

Princess Alice, Countess of Athlone (Alice Mary Victoria Augusta Pauline; 25 February 1883 – 3 January 1981) was a member of the British royal family. She is the longest-lived British princess of royal blood, and was the last surviving grand ...

and Alice Roosevelt

Alice Lee Roosevelt Longworth (February 12, 1884 – February 20, 1980) was an American writer and socialite. She was the eldest child of U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt and his only child with his first wife, Alice Hathaway Lee Roosevelt. Lo ...

. Princess Alice of Albany was a granddaughter of Victoria, Queen of the United Kingdom

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previo ...

, and the new bride of Prince Alexander of Teck Teck may refer to:

* Teck Castle (Burg Teck) in Württemberg, Germany

* Teckberg, mountain on which it is located

* Duke of Teck, a title of nobility, associated with Teck Castle

* Teck Railway, Germany

* Teck Resources, a Canadian mining company ...

in Württemberg

Württemberg ( ; ) is a historical German territory roughly corresponding to the cultural and linguistic region of Swabia. The main town of the region is Stuttgart.

Together with Baden and Hohenzollern, two other historical territories, Würt ...

.Eilers, p. 215. Alice Roosevelt, daughter of the then-current U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

, was nicknamed "Princess Alice" by the press, and had launched the racing yacht of Kaiser Wilhelm II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor (german: Kaiser) and List of monarchs of Prussia, King of Prussia, reigning from 15 June 1888 until Abdication of Wilhelm II, his abdication on 9 ...

, ''Meteor'', at Staten Island

Staten Island ( ) is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Richmond County, in the U.S. state of New York. Located in the city's southwest portion, the borough is separated from New Jersey by the Arthur Kill and the Kill Van Kull an ...

two years before. William Lowell Putnam

William Lowell Putnam II (November 22, 1861 – June 1923) (more commonly known as William Putnam, Sr.) was an American lawyer and banker.

Putnam was the son of George and Harriet (Lowell) Putnam. He graduated from Harvard in 1882, and proc ...

gives the namesake as Princess Alice of the United Kingdom

Princess Alice (Alice Maud Mary; 25 April 1843 – 14 December 1878) was Grand Duchess of Hesse and by Rhine from 13 June 1877 until her death in 1878 as the wife of Grand Duke Louis IV. She was the third child and second daughter of Queen ...

, the daughter of Queen Victoria.

''Princess Alice'' departed her new homeport of

''Princess Alice'' departed her new homeport of Bremen

Bremen (Low German also: ''Breem'' or ''Bräm''), officially the City Municipality of Bremen (german: Stadtgemeinde Bremen, ), is the capital of the German state Free Hanseatic City of Bremen (''Freie Hansestadt Bremen''), a two-city-state consis ...

on 22 March 1904 for her maiden voyage under her new owners. After arriving in New York draped in flags and bunting, her dining room was the site of a press luncheon thrown by Lloyd staff celebrating her first arrival in that city. ''Princess Alice'' made four more roundtrips through early August, then shifted to Bremen–Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popular ...

–Far East service, making her first Lloyd voyage on that route 31 August. ''Princess Alice'' would continue this pattern—sailing the North Atlantic during the heaviest-trafficked season and shifting to the Far East runs for the balance of the year—through 1910.

Throughout the rest of her Lloyd North Atlantic career she carried some notable passengers to and from Europe. In May 1905, for example, noted Baltimore gynecologist

Gynaecology or gynecology (see spelling differences) is the area of medicine that involves the treatment of women's diseases, especially those of the reproductive organs. It is often paired with the field of obstetrics, forming the combined area ...

Howard Atwood Kelly

Howard Atwood Kelly (February 20, 1858 – January 12, 1943) was an American gynecologist. He obtained his B.A. degree and M.D. degree from the University of Pennsylvania. He, William Osler, William Halsted, and William Welch together are known ...

, one of the co-founders of Johns Hopkins Hospital

The Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH) is the teaching hospital and biomedical research facility of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, located in Baltimore, Maryland, U.S. It was founded in 1889 using money from a bequest of over $7 million (1873 mo ...

, sailed from New York; author Hamilton Wright Mabie

Hamilton Wright Mabie, A.M., L.H.D., LL.D. (December 13, 1846 – December 31, 1916) was an American essayist, editor, critic, and lecturer.

Biography

Hamilton Wright Mabie was born at Cold Spring, New York on December 13, 1846. He was the young ...

and his wife sailed from New York the following month. American botanist Charles Frederick Millspaugh

Charles Frederick Millspaugh (June 20, 1854– September 15, 1923) was an American botanist and physician, born at Ithaca, N.Y., and educated at Cornell and the New York Homeopathic Medical College. He received his medical degree in 1881 and ...

returned to New York aboard the German liner in June 1906, and retired U.S. Navy Rear admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star "admiral" rank. It is often regarde ...

Alfred Thayer Mahan

Alfred Thayer Mahan (; September 27, 1840 – December 1, 1914) was a United States naval officer and historian, whom John Keegan called "the most important American strategist of the nineteenth century." His book '' The Influence of Sea Power ...

did the same in June 1907. Senator Augustus O. Bacon

Augustus Octavius Bacon (October 20, 1839February 14, 1914) was a Confederate soldier, segregationist, and U.S. politician. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as a U.S. Senator from Georgia, becoming the first Senator to be directly ele ...

( D- GA), sailed for Europe on 1 August 1908.

Prompted by the successful use of wireless

Wireless communication (or just wireless, when the context allows) is the transfer of information between two or more points without the use of an electrical conductor, optical fiber or other continuous guided medium for the transfer. The most ...

in saving lives during the sinking of in January 1909, and by proposed U.S. legislation (later passed as the Wireless Ship Act of 1910

The Wireless Ship Act of 1910, formally titled "An Act to require apparatus and operators for radio-communication on certain ocean steamers" (36 Public Law 262) and also known as the "Radio Ship Act of 1910" and the "Radio Act of 1910", was the f ...

) requiring wireless for ships calling at U.S. ports, ''Princess Alice'' received her first wireless set in February 1909. Operating with call letters "DKZ" on the 300 m band, her radio had a range.

At 10:00 on 27 May 1909, loaded with over 1,000 passengers headed for Europe, ''Princess Alice'' departed the Lloyd pier in Hoboken

Hoboken ( ; Unami: ') is a city in Hudson County in the U.S. state of New Jersey. As of the 2020 U.S. census, the city's population was 60,417. The Census Bureau's Population Estimates Program calculated that the city's population was 58,69 ...

, New Jersey. As she neared The Narrows

__NOTOC__

The Narrows is the tidal strait separating the boroughs of Staten Island and Brooklyn in New York City, United States. It connects the Upper New York Bay and Lower New York Bay and forms the principal channel by which the Hudson Riv ...

in a heavy fog, she steamed to stay clear of outbound French Line

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with France ...

steamer and ran hard aground on a submerged rocky ledge near the seawall

A seawall (or sea wall) is a form of coastal defense constructed where the sea, and associated coastal processes, impact directly upon the landforms of the coast. The purpose of a seawall is to protect areas of human habitation, conservation ...

of Fort Wadsworth

Fort Wadsworth is a former Military of the United States, United States military installation on Staten Island in New York City, situated on The Narrows which divide New York Bay into Upper New York Bay, Upper and Lower New York Bay, Lower halv ...

a few minutes after 11:00. After the fog lifted, it was revealed that the bow of ''Princess Alice'' had stopped some from the outer walls of the Staten Island fort. Lighthouse tender

A lighthouse tender is a ship specifically designed to maintain, support, or tend to lighthouses or lightvessels, providing supplies, fuel, mail, and transportation.

In the United States, these ships originally served as part of the Lighthous ...

''Larkspur'' was the first ship to come to the aid of the ''Princess'', followed by U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cl ...

Quartermaster's ship ''General Meigs'' and revenue cutter

A cutter is a type of watercraft. The term has several meanings. It can apply to the rig (or sailplan) of a sailing vessel (but with regional differences in definition), to a governmental enforcement agency vessel (such as a coast guard or bor ...

''Seneca''. No passengers were hurt in the incident and it was determined there was no damage to the hull of the liner. But, despite the effort of attending ships, she remained stuck on the ledge. Eventually, after offloading of cargo from her front hold

Hold may refer to:

Physical spaces

* Hold (ship), interior cargo space

* Baggage hold, cargo space on an airplane

* Stronghold, a castle or other fortified place

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Hold (musical term), a pause, also called a Fermat ...

onto lighters

A lighter is a portable device which creates a flame, and can be used to ignite a variety of items, such as cigarettes, gas lighter, fireworks, candles or campfires. It consists of a metal or plastic container filled with a flammable liquid or ...

called to the scene, ten steam tugs and power from ''Princess Alice''s own engines freed the ship at 01:47 on 28 May, almost 15 hours after running aground. The force required to free the liner was great enough that she was then propelled into SS ''Marken'', at anchor some distance away, damaging one of that ship's fenders. After then making her way to the nearby New York City Quarantine Station, ''Princess Alice'' anchored to reload her cargo, and by 09:05, she was underway again. However, she ran aground again in soft mud in Ambrose Channel

Ambrose Channel is the only shipping channel in and out of the Port of New York and New Jersey. The channel is considered to be part of Lower New York Bay and is located several miles off the coasts of Sandy Hook, New Jersey, and Breezy Point, ...

at 10:15. This time she was able to free herself and proceeded on to Bremen, a little more than 24 hours late. This voyage was further marred by the apparent suicide of a despondent New York attorney on 30 May. The man, headed to the spa town of Bad Nauheim

Bad Nauheim is a town in the Wetteraukreis district of Hesse state of Germany.

As of 2020, Bad Nauheim has a population of 32,493. The town is approximately north of Frankfurt am Main, on the east edge of the Taunus mountain range. It is a worl ...

in Hesse, had previously suffered a nervous breakdown

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness or psychiatric disorder, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. Such features may be persistent, relapsing and remitti ...

and was under the care of a doctor on board the ship at the time he jumped overboard.

In May 1910, ''Princess Alice'' sailed her last North Atlantic passage for her German owners. Put permanently on the Far East route, she plied Pacific waters for North German Lloyd until the outbreak of World War I. In late July 1914, as war spread across Europe, ''Princess Alice'' neared her destination of Hong Kong with £850,000 of gold from

In May 1910, ''Princess Alice'' sailed her last North Atlantic passage for her German owners. Put permanently on the Far East route, she plied Pacific waters for North German Lloyd until the outbreak of World War I. In late July 1914, as war spread across Europe, ''Princess Alice'' neared her destination of Hong Kong with £850,000 of gold from India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

. Rather than face seizure of the ship and her cargo by British authorities there, ''Princess Alice'' instead sped to the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

and deposited the gold with the German Consul at Manila

Manila ( , ; fil, Maynila, ), officially the City of Manila ( fil, Lungsod ng Maynila, ), is the capital of the Philippines, and its second-most populous city. It is highly urbanized and, as of 2019, was the world's most densely populate ...

. Leaving the neutral port in under 24 hours, the ship then rendezvoused with German cruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. Modern cruisers are generally the largest ships in a fleet after aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships, and can usually perform several roles.

The term "cruiser", which has been in use for several hu ...

at Angaur

, or in Palauan, is an island and state in the island nation of Palau.

History

Angaur was traditionally divided among some eight clans. Traditional features within clan areas represent important symbols giving identity to families, clans and ...

before returning to the Philippines in early August and putting in at Cebu

Cebu (; ceb, Sugbo), officially the Province of Cebu ( ceb, Lalawigan sa Sugbo; tl, Lalawigan ng Cebu; hil, Kapuroan sang Sugbo), is a province of the Philippines located in the Central Visayas region, and consists of a main island and 167 ...

where she was interned.

USS ''Princess Matoika''

On 6 April 1917 the United States declared war and immediately seized interned German ships at U.S. and territorial ports, but unlike most other German ships interned by the United States, ''Princess Alice'' had not been sabotaged by her German crew before her seizure. Assigned the Identification Number of 2290, she was soon renamed ''Princess Matoika''. Sources disagree about the identity of the ship's namesake, who is often reported as either a member of the Philippine Royal Family, or a Japanese princess.Cutchins and Stewart, p. 64. Cutchins and Stewart are quoting Ernest R. Kinkle and John J. Pullam, historians of the 113th Infantry Regiment. Putnam, however, provides another answer: one of the given names ofPocahontas

Pocahontas (, ; born Amonute, known as Matoaka, 1596 – March 1617) was a Native American woman, belonging to the Powhatan people, notable for her association with the colonial settlement at Jamestown, Virginia. She was the daughter of ...

was ''Matoaka'', which was sometimes spelled ''Matoika''.Putnam, p. 145, note 32. Given that two other ex-German liners were renamed and —after Pocahontas

Pocahontas (, ; born Amonute, known as Matoaka, 1596 – March 1617) was a Native American woman, belonging to the Powhatan people, notable for her association with the colonial settlement at Jamestown, Virginia. She was the daughter of ...

and Powhatan

The Powhatan people (; also spelled Powatan) may refer to any of the indigenous Algonquian people that are traditionally from eastern Virginia. All of the Powhatan groups descend from the Powhatan Confederacy. In some instances, The Powhatan ...

(her father)—this seems the most likely. The newly renamed ship was taken to Olongapo City

Olongapo, officially the City of Olongapo ( fil, Lungsod ng Olongapo; ilo, Siudad ti Olongapo; xsb, Siyodad nin Olongapo), is a 1st class highly urbanized city in the Central Luzon region of the Philippines. Located in the province of Zambales ...

, north of Manila

Manila ( , ; fil, Maynila, ), officially the City of Manila ( fil, Lungsod ng Maynila, ), is the capital of the Philippines, and its second-most populous city. It is highly urbanized and, as of 2019, was the world's most densely populate ...

and placed in the drydock

A dry dock (sometimes drydock or dry-dock) is a narrow basin or vessel that can be flooded to allow a load to be floated in, then drained to allow that load to come to rest on a dry platform. Dry docks are used for the construction, maintenance, ...

'' Dewey'' at Subic Bay

Subic Bay is a bay on the west coast of the island of Luzon in the Philippines, about northwest of Manila Bay. An extension of the South China Sea, its shores were formerly the site of a major United States Navy facility, U.S. Naval Base Subi ...

where temporary repairs were made. She then made her way to San Francisco, and eventually to the east coast

East Coast may refer to:

Entertainment

* East Coast hip hop, a subgenre of hip hop

* East Coast (ASAP Ferg song), "East Coast" (ASAP Ferg song), 2017

* East Coast (Saves the Day song), "East Coast" (Saves the Day song), 2004

* East Coast FM, a ra ...

. ''Princess Matoika'' was the last ex-German ship to be commissioned.Crowell and Wilson, p. 417.

Transporting troops to France

Placed under the command ofWilliam D. Leahy

William Daniel Leahy () (May 6, 1875 – July 20, 1959) was an American naval officer who served as the most senior United States military officer on active duty during World War II. He held multiple titles and was at the center of all major ...

in April 1918, the ship was readied for her first transatlantic troop run. At Newport News

Newport News () is an independent city in the U.S. state of Virginia. At the 2020 census, the population was 186,247. Located in the Hampton Roads region, it is the 5th most populous city in Virginia and 140th most populous city in the Uni ...

, Virginia, elements of the 4th Infantry Division boarded on 9 May.Pollard, p. 26. Sailing at 18:30 the next day, ''Princess Matoika'' was accompanied by American transports , , , , and , the British steamer ''Kursk'', and the Italian . The group rendezvoused with a similar group that left New York the same day, consisting of , , , British troopship , and Italian steamers and .Crowell and Wilson, p. 609.Gleaves, p. 202. American cruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. Modern cruisers are generally the largest ships in a fleet after aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships, and can usually perform several roles.

The term "cruiser", which has been in use for several hu ...

served as escort for the assembled ships, which were the 35th U.S. convoy of the war. During the voyage—because of the inability to finish serving three meals for all the men during daylight hours—mess service was curtailed to two daily meals, a practice continued on later voyages.Cutchins and Stewart, p. 65. On 20 May, the convoy sighted and fired on a "submarine" that turned out to be a bucket; the next day escort ''Frederick'' left the convoy after being relieved by nine destroyers. Three days later the convoy sighted land at 06:30 and anchored at Brest

Brest may refer to:

Places

*Brest, Belarus

**Brest Region

**Brest Airport

**Brest Fortress

*Brest, Kyustendil Province, Bulgaria

*Břest, Czech Republic

*Brest, France

**Arrondissement of Brest

**Brest Bretagne Airport

** Château de Brest

*Brest, ...

that afternoon.Pollard, p. 27. ''Princess Matoika'' sailed for Newport News and arrived there safely on 6 June with ''Pastores'' and ''Lenape''. Fate, however, was not as kind to former convoy mates ''President Lincoln'' and ''Dwinsk''. On their return journeys they were sunk by German submarines ''U-90'' and ''U-151'', respectively.''German submarine activities'', p. 48.

After loading officers and men from the 29th Infantry Division on 13 June, ''Princess Matoika'' set sail from Newport News the next day with ''Wilhelmina'', ''Pastores'', ''Lenape'', and British troopship . On the morning of 16 June, lookouts on ''Princess Matoika'' spotted a submarine and, soon after, a torpedo heading directly for the ship. The torpedo missed her by a few yards and gunners manning the ship's guns claimed a hit on the sub with their second shot.Cutchins and Stewart, p. 66. Later that morning, the Newport News ships met up with the New York portion of the convoy—which included , , , , ''Covington'', ''Rijndam'', ''Dante Alighieri'', and British steamer ''Vauben''—and set out for France.Cutchins and Stewart, p. 67.Crowell and Wilson, p. 610–11. The convoy was escorted by cruisers and ''Frederick'', and

After loading officers and men from the 29th Infantry Division on 13 June, ''Princess Matoika'' set sail from Newport News the next day with ''Wilhelmina'', ''Pastores'', ''Lenape'', and British troopship . On the morning of 16 June, lookouts on ''Princess Matoika'' spotted a submarine and, soon after, a torpedo heading directly for the ship. The torpedo missed her by a few yards and gunners manning the ship's guns claimed a hit on the sub with their second shot.Cutchins and Stewart, p. 66. Later that morning, the Newport News ships met up with the New York portion of the convoy—which included , , , , ''Covington'', ''Rijndam'', ''Dante Alighieri'', and British steamer ''Vauben''—and set out for France.Cutchins and Stewart, p. 67.Crowell and Wilson, p. 610–11. The convoy was escorted by cruisers and ''Frederick'', and destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

s and ; battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1880s to describe a type of ...

and several other destroyers joined in escort duties for the group for a time. The convoy had a false alarm when a floating barrel was mistaken for submarine, but otherwise uneventfully arrived at Brest on the afternoon of 27 June.Cutchins and Stewart, p. 68. ''Princess Matoika'', ''Covington'', ''Lenape'', ''Rijndam'', ''George Washington'', ''DeKalb'', ''Wilhelmina'', and ''Dante Alighieri'' left Brest as a group on 30 June.Feuer, p. 63. The following evening at 21:15, ''Covington'' was torpedoed by ''U-86'' and sank the next afternoon. ''Princess Matoika'' and ''Wilhelmina'' arrived back at Newport News on 13 July.

Around this time, Commander Leahy left ''Princess Matoika'' to serve as Director of Gunnery Exercises and Engineering Performance in Washington. For his service on ''Princess Matoika'', though, Leahy was awarded the

Around this time, Commander Leahy left ''Princess Matoika'' to serve as Director of Gunnery Exercises and Engineering Performance in Washington. For his service on ''Princess Matoika'', though, Leahy was awarded the Navy Cross

The Navy Cross is the United States Navy and United States Marine Corps' second-highest military decoration awarded for sailors and marines who distinguish themselves for extraordinary heroism in combat with an armed enemy force. The medal is eq ...

. He was cited for distinguished service as commander of the ship while "engaged in the important, exacting and hazardous duty of transporting and escorting troops and supplies through waters infested with enemy submarines and mines".Stringer, p. 95.

In the next months, ''Princess Matoika'' successfully completed two additional roundtrips from Newport News. On the first trip, she left Newport News with ''DeKalb'', ''Dante Alighiere'', ''Wilhelmina'', ''Pastores'', and British troopship on 18 July.Crowell and Wilson, p. 613. The group joined a New York contingent and arrived in France on 30 July. Departing soon after, the ''Princess'' returned to Newport News on 13 August. Nine days later she departed in the company of the same ships from her last convoy—with French steamer ''Lutetia'' replacing ''DeKalb''—and arrived in France on 3 September.Crowell and Wilson, p. 615. ''Princess Matoika'' returned stateside two weeks later.

On 23 September, ''Princess Matoika'' departed New York with 3,661 officers and men accompanied by transports , , ''Rijndam'', ''Wilhelmina'', British steamer ''Ascanius'', and was escorted by battleship , cruisers and ''North Carolina'', and destroyer .Crowell and Wilson, p. 559, 617. As with other Navy ships throughout 1918, ''Princess Matoika'' was not immune to the worldwide Spanish flu

The 1918–1920 influenza pandemic, commonly known by the misnomer Spanish flu or as the Great Influenza epidemic, was an exceptionally deadly global influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 influenza A virus. The earliest documented case was ...

pandemic. On this particular crossing, two of her crewmen were felled by the disease as her convoy reached Saint-Nazaire

Saint-Nazaire (; ; Gallo: ''Saint-Nazère/Saint-Nazaer'') is a commune in the Loire-Atlantique department in western France, in traditional Brittany.

The town has a major harbour on the right bank of the Loire estuary, near the Atlantic Ocean ...

on 6 October.Bureau of Naval Personnel, ''Officers and Enlisted Men...'', p. 729, 797. The source did not provide information on whether there were any deaths among Army personnel aboard. After her return to the U.S. on 21 October, she departed New York once again on 28 October, arriving in France on 9 November, two days before the Armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the La ...

.Crowell and Wilson, p. 619. In all, she carried 21,216 troops to France on her six trips overseas.Gleaves, p. 248–49.

Returning troops home

With the fighting at an end, the task of bringing home American soldiers began almost immediately.Gleaves, p. 31. ''Princess Matoika'' did her part by carrying home 30,110 healthy and wounded men in eight roundtrips. On 20 December, 3,000 troops boarded her and departed France for Newport News, arriving there on 1 January 1919. Among those carried wereMajor General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Charles T. Menoher, the newly appointed chief of the air service, and elements of the 39th Infantry Division. The ''Matoika'' arrived with another 2,000 troops on 11 February.

In March 1919, ''Princess Matoika'' and ''Rijndam'' raced each other from Saint-Nazaire to Newport News in a friendly competition that received national press coverage in the United States. ''Rijndam'', the slower ship, was just able to edge out the ''Princess''—and cut two days from her previous fastest crossing time—by appealing to the honor of the soldiers of the 133rd Field Artillery (returning home aboard the former Holland America

Holland America Line is an American-owned cruise line, a subsidiary of Carnival Corporation & plc headquartered in Seattle, Washington, United States.

Holland America Line was founded in Rotterdam, Netherlands, and from 1873 to 1989, it operated ...

liner) and employing them as extra stokers for her boilers.Harlow, p. 195, quoting Kent Watson from ''History of the 133d Regiment''.

On her next trip, the veteran transport loaded troops at Saint-Nazaire

Saint-Nazaire (; ; Gallo: ''Saint-Nazère/Saint-Nazaer'') is a commune in the Loire-Atlantique department in western France, in traditional Brittany.

The town has a major harbour on the right bank of the Loire estuary, near the Atlantic Ocean ...

that included nine complete hospital units. After two days delay because of storms in the Bay of Biscay

The Bay of Biscay (), known in Spain as the Gulf of Biscay ( es, Golfo de Vizcaya, eu, Bizkaiko Golkoa), and in France and some border regions as the Gulf of Gascony (french: Golfe de Gascogne, oc, Golf de Gasconha, br, Pleg-mor Gwaskogn), ...

, ''Princess Matoika'' departed on 16 April, and arrived at Newport News on 27 April with 3,500 troops.Brown, p. 145–46. Shifting south to Charleston

Charleston most commonly refers to:

* Charleston, South Carolina

* Charleston, West Virginia, the state capital

* Charleston (dance)

Charleston may also refer to:

Places Australia

* Charleston, South Australia

Canada

* Charleston, Newfoundlan ...

, South Carolina, the ''Matoika'' embarked 2,200 former German prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held Captivity, captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold priso ...

(POWs) and hauled them to Rotterdam

Rotterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Rotte'') is the second largest city and municipality in the Netherlands. It is in the province of South Holland, part of the North Sea mouth of the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta, via the ''"N ...

.Hagedorn, p. 163. This trip was followed up in May with the return of portions of the 79th Infantry Division from Saint-Nazaire to New York.

In mid-July, ''Princess Matoika'' delivered another load of 1,900 former German POWs from Charleston to Rotterdam; most of these prisoners were officers and men from interned German passenger liners and included Captain Heinler the former commander of . One former POW, shortly after debarking in Europe, presciently commented that "this asno peace; only a temporary truce". After loading American crews of returned Dutch ships, ''Princess Matoika'' called at Antwerp

Antwerp (; nl, Antwerpen ; french: Anvers ; es, Amberes) is the largest city in Belgium by area at and the capital of Antwerp Province in the Flemish Region. With a population of 520,504,

and Brest before returning to New York on 1 August.

The ship departed New York on 8 August for her final roundtrip as a Navy transport. She departed Brest 23 August and returned to New York on 10 September. She was decommissioned there on 19 September, and handed over to the War Department War Department may refer to:

* War Department (United Kingdom)

* United States Department of War (1789–1947)

See also

* War Office, a former department of the British Government

* Ministry of defence

* Ministry of War

* Ministry of Defence

* Dep ...

for use as a United States Army transport.

USAT ''Princess Matoika''

As her career as an Army transport began, ''Princess Matoika'' picked up where her Navy career had ended and continued the return of American troops from Europe. After returning to France she loaded 2,965 troops at Brest—includingBrigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

W. P. Richardson and members of the Polar Bear Expedition

The American Expeditionary Force, North Russia (AEF in North Russia) (also known as the Polar Bear Expedition) was a contingent of about 5,000 United States Army troops that landed in Arkhangelsk, Russia as part of the Allied intervention in th ...

, part of the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War

Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War or Allied Powers intervention in the Russian Civil War consisted of a series of multi-national military expeditions which began in 1918. The Allies first had the goal of helping the Czechoslovak Leg ...

—for a return to New York on 15 October. In December, Congressman Charles H. Randall (Prohibitionist

Prohibitionism is a legal philosophy and political theory often used in lobbying which holds that citizens will abstain from actions if the actions are typed as unlawful (i.e. prohibited) and the prohibitions are enforced by law enforcement.C Canty ...

- CA) and his wife sailed on the ''Matoika'' to Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and Unincorporated ...

and the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a conduit ...

.

On 5 April, ''Princess Matoika'' carried a group of 18 men and three officers of the U.S. Navy who were to attempt a transatlantic flight in the rigid airship ''R38

The ''R.38'' class (also known as the ''A'' class) of rigid airships was designed for Britain's Royal Navy during the final months of the First World War, intended for long-range patrol duties over the North Sea. Four similar airships were ...

'', being built in England for the Navy. Several of the group that traveled on the ''Matoika'' were among the 45 men killed when the airship crashed on 24 August 1921.

In May 1920 ''Princess Matoika'' took on board the bodies of ten female nurses and over 400 soldiers who died while on duty in France during the war. The ship then transited the

In May 1920 ''Princess Matoika'' took on board the bodies of ten female nurses and over 400 soldiers who died while on duty in France during the war. The ship then transited the Kiel Canal

The Kiel Canal (german: Nord-Ostsee-Kanal, literally "North- oEast alticSea canal", formerly known as the ) is a long freshwater canal in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein. The canal was finished in 1895, but later widened, and links the N ...

and picked up 1,600 U.S. residents of Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles, people from Poland or of Polish descent

* Polish chicken

*Polish brothers (Mark Polish and Michael Polish, born 1970), American twin screenwr ...

descent at Danzig, all of whom had enlisted in the Polish Army

The Land Forces () are the land forces of the Polish Armed Forces. They currently contain some 62,000 active personnel and form many components of the European Union and NATO deployments around the world. Poland's recorded military history stret ...

at the outset of the war. Also included among the passengers were 500 U.S. soldiers who had been released from occupation duty at Koblenz

Koblenz (; Moselle Franconian language, Moselle Franconian: ''Kowelenz''), spelled Coblenz before 1926, is a German city on the banks of the Rhine and the Moselle, a multi-nation tributary.

Koblenz was established as a Roman Empire, Roman mili ...

. The ship arrived at New York on 23 May with little fanfare and no ceremony; bodies returned but not claimed by families were buried at Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is one of two national cemeteries run by the United States Army. Nearly 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington, Virginia. There are about 30 funerals conducted on weekdays and 7 held on Sa ...

. On 21 July, ''Princess Matoika'' arrived in New York after a similar voyage with 25 war bride

War brides are women who married military personnel from other countries in times of war or during military occupations, a practice that occurred in great frequency during World War I and World War II.

Among the largest and best documented examp ...

s, many repatriated Polish troops among its 2,094 steerage

Steerage is a term for the lowest category of passenger accommodation in a ship. In the nineteenth and early twentieth century considerable numbers of persons travelled from their homeland to seek a new life elsewhere, in many cases North America ...

passengers, and the remains of 881 soldiers. In between these two trips, the Belgian

Belgian may refer to:

* Something of, or related to, Belgium

* Belgians, people from Belgium or of Belgian descent

* Languages of Belgium, languages spoken in Belgium, such as Dutch, French, and German

*Ancient Belgian language, an extinct languag ...

Ambassador to the United States, Baron

Baron is a rank of nobility or title of honour, often hereditary, in various European countries, either current or historical. The female equivalent is baroness. Typically, the title denotes an aristocrat who ranks higher than a lord or knig ...

Emile de Cartier de Marchienne

Baron Emile-Ernest de Cartier de Marchienne (30 November 1871 in Schaerbeek, Belgium – 10 May 1946 in London, United Kingdom) was a Belgian diplomat. Emile de Cartier de Marchienne was Belgian Minister in the United States, China, the United Kin ...

, sailed from New York to Belgium on board the ''Matoika''. It was, however, ''Princess Matoika''s next trip to Belgium that was the most infamous.

"Mutiny of the ''Matoika'' "

Beginning 26 July 1920, a majority of the U.S. Olympic contingent destined for the1920 Summer Olympics

The 1920 Summer Olympics (french: Jeux olympiques d'été de 1920; nl, Olympische Zomerspelen van 1920; german: Olympische Sommerspiele 1920), officially known as the Games of the VII Olympiad (french: Jeux de la VIIe olympiade; nl, Spelen van ...

in Antwerp, Belgium, endured a troubled transatlantic journey aboard ''Princess Matoika''. The voyage and the events onboard—later called the "Mutiny of the ''Matoika'' "—were still being discussed in the popular press years later. The ''Matoika'' was a last-minute substitute for another ship and, according to the athletes, did not have adequate accommodations or training facilities on board.Findling and Pelle, p. 56. Near the end of the voyage, the athletes published a list of grievances and demands and distributed copies of the document to the United States Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the President of the United States, U.S. president's United States Cabinet, Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's Presidency of George Washington, administration. A similar position, called either "Se ...

, the American Olympic Committee

The United States Olympic & Paralympic Committee (USOPC) is the National Olympic Committee and the National Paralympic Committee for the United States. It was founded in 1895 as the United States Olympic Committee, and is headquartered in C ...

members, and the press. The incident received wide coverage in American newspapers at the time.

After the contingent of athletes debarked at Antwerp on 8 August, ''Princess Matoika'' made one more voyage of note while under U.S. Army control. The ''Matoika'' sailed for New York on 24 August and arrived on 4 September carrying a portion of the returning Olympic team, American Boy Scouts

Boy Scouts may refer to:

* Boy Scout, a participant in the Boy Scout Movement.

* Scouting, also known as the Boy Scout Movement.

* An organisation in the Scouting Movement, although many of these organizations also have female members. There are ...

returning from the International Boy Scout Jamboree in London, and the remains of 1,284 American soldiers for repatriation.

U.S. Mail Line

At the conclusion of her Army service, ''Princess Matoika'' was handed over to the United States Shipping Board (USSB), who chartered the vessel to theUnited States Mail Steamship Company

The United States Mail Steamship Company – also called the United States Mail Line, or the U.S. Mail Line – was a passenger steamship line formed in 1920 by the United States Shipping Board (USSB) to run the USSB's fleet of ex-German ocean l ...

for service from New York to Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

. This solution of how to use the ''Princess'' for civilian service was the culmination of efforts by the USSB to find a suitable civilian use for her. In 1919, she was one of the ships suggested for a proposed service from New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

, Louisiana, to Valparaiso, Chile,McIntosh, p. 20. and in November 1919, tentative plans were announced for her service with the Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Munson Line

The Munson Steamship Line, frequently shortened to the Munson Line, was an American steamship company that operated in the Atlantic Ocean primarily between U.S. ports and ports in the Caribbean and South America. The line was founded in 1899 as a ...

between New York and Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

beginning in mid-1920, but both of these proposals fell through.

''Princess Matoika''—outfitted for 350 cabin-class and 500 third-class passengers and at —kicked off her U.S. Mail Line service on 20 January 1921 when she sailed from New York to Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

and Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the List of cities in Italy, sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian ce ...

on her first of three roundtrips between these ports. After a storm damaged the ''Matoika''s steering gear, she had to be towed back in to New York on 28 January.

After repairs and a successful eastbound crossing, ''Princess Matoika'' had an encounter with an iceberg

An iceberg is a piece of freshwater ice more than 15 m long that has broken off a glacier or an ice shelf and is floating freely in open (salt) water. Smaller chunks of floating glacially-derived ice are called "growlers" or "bergy bits". The ...

off Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

while carrying some 2,000 Italian immigrants on her first return trip from Italy. On the night of 24 February, the fully laden ship struck what was reported in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' as either "an iceberg or a submerged wreck" off Cape Race

Cape Race is a point of land located at the southeastern tip of the Avalon Peninsula on the island of Newfoundland, in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. Its name is thought to come from the original Portuguese name for this cape, "Raso", mea ...

. The ship's steering gear was damaged in the collision, leaving the ship adrift for over seven hours before repairs were effected. The ''Matoika''s captain indicated that no passengers were hurt in the collision. According to the story of one third-class passenger, she, suspecting there was something seriously amiss, made inquiry after the commotion. A crew member told her that the ''Matoika'' had only stopped to greet a ship passing in the night. When she went on deck, insistent on seeing the other ship herself, she saw the iceberg and observed the first-class passengers queued up to board the already-lowered lifeboats

Lifeboat may refer to:

Rescue vessels

* Lifeboat (shipboard), a small craft aboard a ship to allow for emergency escape

* Lifeboat (rescue), a boat designed for sea rescues

* Airborne lifeboat, an air-dropped boat used to save downed airmen

A ...

. She took her daughter with her to join one of the queues, and, though initially rebuffed, was allowed to remain. The lifeboats were never deployed, however, and the ''Matoika'' arrived in Boston, where she had been diverted due to a typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure.

...

scare, on 28 February without further incident.

On the ''Matoika''s third and final return voyage from Italy, begun on 17 May, U.S. Customs Service

The United States Customs Service was the very first federal law enforcement agency of the Federal government of the United States, U.S. federal government. Established on July 31, 1789, it collected import tariffs, performed other selected borde ...

agents at New York seized $150,000 worth of cocaine

Cocaine (from , from , ultimately from Quechuan languages, Quechua: ''kúka'') is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant mainly recreational drug use, used recreationally for its euphoria, euphoric effects. It is primarily obtained from t ...

—along with valuable silks and jewels—being smuggled into the United States. Officials speculated that because of a maritime strike, members of a smuggling ring were able to infiltrate the crew of the ship.

After her withdrawal from the Italian route, ''Princess Matoika'' was transferred to New York–Bremen service, sailing on her first commercial trip to Germany since before World War I on 14 June. In July, during her second roundtrip on the Bremen route, late rental payments to the USSB resulted in action to seize the nine ships chartered by the U.S. Mail Line, including the ''Matoika'', after its return from Bremen. The ships were turned over to United American Lines United American Lines, the common name of the American Shipping and Commercial Corporation, was a shipping company founded by W. Averell Harriman in 1920. Intended as a way for Harriman to make his mark in the business world outside of his father, r ...

— W. Averell Harriman's steamship company—for temporary operation. After some legal wrangling by both the USSB and the U.S. Mail Line—and in light of financial irregularities by the U.S. Mail Line that were uncovered—the ships were permanently retained by the USSB in August.

United States Lines

Upon the formation of the United States Lines in August 1921, ''Princess Matoika'' and the eight other ex-German liners formerly operated by the U.S. Mail Line were transferred to the new company for operation. The ''Princess'', still on New York–Bremen service, sailed on her first voyage for the new steamship line on 15 September. In October, ''Matoika'' crewmen were reported as taking advantage of the German inflation by consuming champagne available for $1.00 per quart and mugs of "the best beer" for an American penny. In November, United States Lines announced that ''Princess Matoika'' would be replaced on the Bremen route in order to better compete withNorth German Lloyd

Norddeutscher Lloyd (NDL; North German Lloyd) was a German shipping company. It was founded by Hermann Henrich Meier and Eduard Crüsemann in Bremen on 20 February 1857. It developed into one of the most important German shipping companies of t ...

, the liner's former owner, but that never came about. The ''Princess'' continued on runs to Bremen, calling at the additional ports of Queenstown, Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

, and Danzig, as her schedule shifted from time to time.

On 28 January 1922, the ''Matoika'' departed with 400 passengers, among them, 312 Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles, people from Poland or of Polish descent

* Polish chicken

*Polish brothers (Mark Polish and Michael Polish, born 1970), American twin screenwr ...

orphans headed for repatriation in their homeland. Two days and out of New York, the liner experienced a heavy gale

A gale is a strong wind; the word is typically used as a descriptor in nautical contexts. The U.S. National Weather Service defines a gale as sustained surface winds moving at a speed of between 34 and 47 knots (, or ).Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

forces, the orphans had been taken across Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

, evacuated to Japan, transported to Seattle

Seattle ( ) is a seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in both the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest regio ...

, Washington, and taken by rail to Chicago, Illinois, where they were enrolled in school while searches for relatives in Poland were conducted.

After four Bremen roundtrips for United States Lines, ''Princess Matoika'' had sailed her last voyage under that name. When newly built Type 535 vessels named for American presidents came into service for the company in May 1922, the ''Princess'' was renamed SS ''President Arthur'' in honor of the 21st

After four Bremen roundtrips for United States Lines, ''Princess Matoika'' had sailed her last voyage under that name. When newly built Type 535 vessels named for American presidents came into service for the company in May 1922, the ''Princess'' was renamed SS ''President Arthur'' in honor of the 21st U.S. President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

, Chester A. Arthur

Chester Alan Arthur (October 5, 1829 – November 18, 1886) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 21st president of the United States from 1881 to 1885. He previously served as the 20th vice president under President James A ...

, matching the naming style of the new ships.Drechsel, Vol. 1, p. 339

After her rename, she continued plying the North Atlantic between New York and Bremen, and was involved in a few episodes of note during this time. In June 1922, two years into Prohibition in the United States

In the United States from 1920 to 1933, a Constitution of the United States, nationwide constitutional law prohibition, prohibited the production, importation, transportation, and sale of alcoholic beverages. The alcohol industry was curtai ...

, ''President Arthur'' was raided while at her dock in Hoboken, New Jersey, which netted 150 cases of smuggled spirits. Officials involved denied reports that the raid was conducted as a legal test case

In software engineering, a test case is a specification of the inputs, execution conditions, testing procedure, and expected results that define a single test to be executed to achieve a particular software testing objective, such as to exercise ...

intended to test the determination of USSB chair Albert Lasker

Albert Davis Lasker (May 1, 1880 – May 30, 1952) was an American businessman who played a major role in shaping modern advertising. He was raised in Galveston, Texas, where his father was the president of several banks. Moving to Chicago, he be ...

that United States-flagged ships could carry and sell alcohol outside the three-mile territorial limit of the United States. Congressman James A. Gallivan

James Ambrose Gallivan (October 22, 1866 – April 3, 1928) was a United States representative from Massachusetts.

Biography

Gallivan was born in Boston on October 22, 1866. He attended the public schools, graduated from the Boston Latin School ...

( D- MA), an anti-prohibition leader, publicly demanded to know why the ship had not been seized for violating U.S. laws.

In September, ''President Arthur'' carried Irish republicans

Irish republicanism ( ga, poblachtánachas Éireannach) is the political movement for the unity and independence of Ireland under a republic. Irish republicans view British rule in any part of Ireland as inherently illegitimate.

The developm ...

Muriel MacSwiney

Muriel MacSwiney (, 8 June 1892 – 26 October 1982) was an Irish republican and left-wing activist, and the first woman to be given the Freedom of New York City. She was the wife of Terence MacSwiney, mother of Máire MacSwiney Brugha and si ...

, widow of the recently deceased Lord Mayor of Cork

The Lord Mayor of Cork ( ga, Ard-Mhéara Chathair Chorcaí) is the honorific title of the Chairperson ( ga, Cathaoirleach) of Cork City Council which is the local government body for the city of Cork (city), Cork in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. ...

Terence MacSwiney

Terence James MacSwiney (; ga, Toirdhealbhach Mac Suibhne; 28 March 1879 – 25 October 1920) was an Irish playwright, author and politician. He was elected as Sinn Féin Lord Mayor of Cork during the Irish War of Independence in 1920. He ...

, and Linda Mary Kearns, who had been jailed for murder under the Black and Tans

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white have ...

, to New York. Wearing buttons with pictures of Harry Boland

Harry Boland (27 April 1887 – 1 August 1922) was an Irish republican politician who served as President of the Irish Republican Brotherhood from 1919 to 1920. He served as a Teachta Dála (TD) from 1918 to 1922.

He was elected at the 1918 ...

, an anti-treaty

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations

An international organization or international o ...

Irish nationalist who had been killed the previous month, the two women were there to raise funds for orphans of Anti-Treaty IRA

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty ( ga , An Conradh Angla-Éireannach), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the ...

forces, who were then fighting in southern Ireland. In October, a Hoboken man, after securing a last-minute court order

A court order is an official proclamation by a judge (or panel of judges) that defines the legal relationships between the parties to a hearing, a trial, an appeal or other court proceedings. Such ruling requires or authorizes the carrying out o ...

, was able to halt the deportation of his German niece on ''President Arthur''; she was retrieved from the ship ten minutes before sailing time.

In November 1922, U.S. Customs Service agents, seized a cache of Colt

Colt(s) or COLT may refer to:

*Colt (horse), an intact (uncastrated) male horse under four years of age

People

* Colt (given name)

*Colt (surname)

Places

*Colt, Arkansas, United States

*Colt, Louisiana, an unincorporated community, United States ...

magazine

A magazine is a periodical publication, generally published on a regular schedule (often weekly or monthly), containing a variety of content. They are generally financed by advertising, purchase price, prepaid subscriptions, or by a combinatio ...

guns aboard ''President Arthur''. The entire crew was questioned but all denied any knowledge of the eight weapons found stowed behind a bulkhead. In August the following year, ''President Arthur'' took on board a seaman suffering from pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severity ...

from the Norwegian

Norwegian, Norwayan, or Norsk may refer to:

*Something of, from, or related to Norway, a country in northwestern Europe

*Norwegians, both a nation and an ethnic group native to Norway

*Demographics of Norway

*The Norwegian language, including the ...

freighter ''Eastern Star'' in a mid-ocean transfer. The ship's doctor and nurse attended to the sailor but were unable to save him.

''President Arthur'' sailed on her last transatlantic voyage from Bremen on 18 October 1923, carrying 656 passengers to New York. Anchoring off Gravesend Bay