Russian Constitutional Crisis Of 1993 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The 1993 Russian constitutional crisis, also known as the 1993 October Coup, Black October, the Shooting of the White House or Ukaz 1400, was a political stand-off and a constitutional crisis between the

During its December session, the parliament clashed with Yeltsin on a number of issues, and the conflict came to a head on 9 December when the parliament refused to confirm

During its December session, the parliament clashed with Yeltsin on a number of issues, and the conflict came to a head on 9 December when the parliament refused to confirm

/ref> with a strong attack on the president by Khasbulatov, who accused Yeltsin of acting unconstitutionally. In mid-March, an emergency session of the Congress of People's Deputies voted to amend the constitution, strip Yeltsin of many of his powers, and cancel the scheduled April referendum, again opening the door to legislation that would shift the balance of power away from the president. The president stalked out of the congress.

The ninth congress, which opened on 26 March, began with an extraordinary session of the Congress of People's Deputies taking up discussions of emergency measures to defend the constitution, including

The ninth congress, which opened on 26 March, began with an extraordinary session of the Congress of People's Deputies taking up discussions of emergency measures to defend the constitution, including

, by A. Bratersky, for

Google Books excerpt

/ref>

By sunrise on 4 October, the Russian army encircled the parliament building, and a few hours later army tanks began to shell the White House, punching holes in the front of it. At 8:00 am Moscow time, Yeltsin's declaration was announced by his press service. Yeltsin declared:

By sunrise on 4 October, the Russian army encircled the parliament building, and a few hours later army tanks began to shell the White House, punching holes in the front of it. At 8:00 am Moscow time, Yeltsin's declaration was announced by his press service. Yeltsin declared:

Леонид Прошкин - "Правых в этой истории не было"

/ref> "Russia needs order," Yeltsin told the Russian people in a television broadcast in November in introducing his new draft of the constitution, which was to be put to a referendum on 12 December. The new basic law would concentrate sweeping powers in the hands of the president. The bicameral legislature, to sit for only two years, was restricted in crucial areas. The president could choose the prime minister even if the parliament objected and could appoint the military leadership without parliamentary approval. He would head and appoint the members of a new, more powerful security council. If a vote of no confidence in the government was passed, the president would be enabled to keep it in office for three months and could dissolve the parliament if it repeated the vote. The president could veto any bill passed by a simple majority in the lower house, after which a two-thirds majority would be required for the legislation to be passed. The president could not be impeached for contravening the constitution. The central bank would become independent, but the president would need the approval of the State Duma to appoint the bank's governor, who would thereafter be independent of the parliament. At the time, most political observers regarded the draft constitution as shaped by and for Yeltsin and perhaps unlikely to survive him.

Расстрел «Белого дома». Чёрный октябрь 1993. (The shooting of the "White House". Black October 1993.)

— М.: «Книжный мир», 2014. — 640 с. ISBN 978-5-8041-0637-0.

article by Ellen Barry in ''The New York Times'' October 11, 2008 (15th anniversary demonstration)

A collection of materials on the topic; pro-parliament

* Draft Constitution (Fundamental Law) of the Russian Federation (Constitutional Commission draft, text as of August 1993) * Draft Constitution (Fundamental Law) of the Russian Federation (presidential draft, text as of April 30, 1993) * Draft Constitution of the Russian Federation (Constitutional Convention draft, text as of July 12, 1993)

Constitution of the Russian Federation

as adopted on December 12, 1993 (withou

Getty Images the Constitutional Crisis of 1993

{{DEFAULTSORT:Russian Constitutional Crisis

Russian president

The president of the Russian Federation ( rus, Президент Российской Федерации, Prezident Rossiyskoy Federatsii) is the head of state of the Russian Federation. The president leads the executive branch of the federal ...

Boris Yeltsin

Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin ( rus, Борис Николаевич Ельцин, p=bɐˈrʲis nʲɪkɐˈla(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ ˈjelʲtsɨn, a=Ru-Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin.ogg; 1 February 1931 – 23 April 2007) was a Soviet and Russian politician wh ...

and the Supreme Soviet of the Russian Federation

The Supreme Soviet of the Russian SFSR (russian: Верховный Совет РСФСР, ''Verkhovny Sovet RSFSR''), later Supreme Soviet of the Russian Federation (russian: Верховный Совет Российской Федерации, ...

that was resolved by Yeltsin using military force.

The relations between the president and the parliament had been deteriorating for some time. The power struggle reached its crisis

A crisis ( : crises; : critical) is either any event or period that will (or might) lead to an unstable and dangerous situation affecting an individual, group, or all of society. Crises are negative changes in the human or environmental affair ...

on 21 September 1993, when President Yeltsin intended to dissolve the country's highest body ( Congress of People's Deputies) and parliament (Supreme Soviet

The Supreme Soviet (russian: Верховный Совет, Verkhovny Sovet, Supreme Council) was the common name for the legislative bodies (parliaments) of the Soviet socialist republics (SSR) in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) ...

), although the constitution did not give the president the power to do so. Yeltsin justified his orders by the results of the referendum of April 1993, although many in Russia both then and now claim that referendum was not won fairly.

In response, the parliament declared the president's decision null and void, impeached Yeltsin and proclaimed vice president Aleksandr Rutskoy

Alexander Vladimirovich Rutskoy (russian: Александр Владимирович Руцкой; born 16 September 1947) is a Russian politician and a former Soviet military officer, Major General of Aviation (1991). He served as the only vic ...

to be acting president. On 3 October, demonstrators removed militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

cordons around the parliament and, urged by their leaders, took over the Mayor's offices and tried to storm the Ostankino television centre. The army, which had initially declared its neutrality, stormed the Supreme Soviet building in the early morning hours of 4 October by Yeltsin's order, and arrested the leaders of the resistance. At the climax of the crisis, Russia was thought by some to be "on the brink" of civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

. The ten-day conflict became the deadliest single event of street fighting in Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

's history

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the History of writing#Inventions of writing, invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbr ...

since the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

.

According to the General Prosecutor's Office, 147 people were killed and 437 wounded.

Origins

Intensifying executive-legislative power struggle

TheSoviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

broke up on 26 December 1991. In Russia, Yeltsin's economic reform program took effect on 2 January 1992. Soon afterward, price

A price is the (usually not negative) quantity of payment or compensation given by one party to another in return for goods or services. In some situations, the price of production has a different name. If the product is a "good" in the c ...

s skyrocketed, government spending was slashed, and heavy new tax

A tax is a compulsory financial charge or some other type of levy imposed on a taxpayer (an individual or legal entity) by a governmental organization in order to fund government spending and various public expenditures (regional, local, or n ...

es went into effect. A deep credit

Credit (from Latin verb ''credit'', meaning "one believes") is the trust which allows one party to provide money or resources to another party wherein the second party does not reimburse the first party immediately (thereby generating a debt), ...

crunch shut down many industries and led to a protracted depression. As a result, unemployment reached record levels. The program began to lose support, and the ensuing political confrontation between Yeltsin on one side, and the opposition to radical economic reform on the other, became increasingly centered in the two branches of government.

Throughout 1992, opposition to Yeltsin's reform policies grew stronger and more intractable among bureaucrats concerned about the condition of Russian industry and among regional leaders who wanted more independence from Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

. Russia's vice president, Aleksandr Rutskoy

Alexander Vladimirovich Rutskoy (russian: Александр Владимирович Руцкой; born 16 September 1947) is a Russian politician and a former Soviet military officer, Major General of Aviation (1991). He served as the only vic ...

, denounced the Yeltsin program as "economic genocide". From 1991 to 1998 the first seven years of Yeltsin's incumbency, the Russian Gross Domestic Product

Gross domestic product (GDP) is a money, monetary Measurement in economics, measure of the market value of all the final goods and services produced and sold (not resold) in a specific time period by countries. Due to its complex and subjec ...

(measured by purchasing power parity

Purchasing power parity (PPP) is the measurement of prices in different countries that uses the prices of specific goods to compare the absolute purchasing power of the countries' currency, currencies. PPP is effectively the ratio of the price of ...

) went from over two trillion U.S. dollars annually to less than one and a quarter trillion U.S. per annum. The United States provided an estimated $2.58 billion of official aid to Russia during the eight years of Clinton's presidency, to build a new economic system, and he encouraged American businesses to invest. Leaders of oil

An oil is any nonpolar chemical substance that is composed primarily of hydrocarbons and is hydrophobic (does not mix with water) & lipophilic (mixes with other oils). Oils are usually flammable and surface active. Most oils are unsaturated ...

-rich republics such as Tatarstan

The Republic of Tatarstan (russian: Республика Татарстан, Respublika Tatarstan, p=rʲɪsˈpublʲɪkə tətɐrˈstan; tt-Cyrl, Татарстан Республикасы), or simply Tatarstan (russian: Татарстан, tt ...

and Bashkiria called for full independence from Russia.

Also throughout 1992, Yeltsin wrestled with the Supreme Soviet (the standing legislature) and the Russian Congress of People's Deputies (the country's highest legislative body, from which the Supreme Soviet members were drawn) for control over government and government policy. In 1992 the speaker of the Russian Supreme Soviet, Ruslan Khasbulatov

Ruslan Imranovich Khasbulatov (russian: link=no, Русла́н Имранович Хасбула́тов, ce, Хасбола́ти Имра́ни кIант Руслан) (born November 22, 1942) is a Russian economist and politician and the ...

, came out in opposition to the reforms, despite claiming to support Yeltsin's overall goals.

The president was concerned about the terms of the constitutional amendments passed in late 1991, which meant that his special powers of decree were set to expire by the end of 1992 (Yeltsin expanded the powers of the presidency beyond normal constitutional limits in carrying out the reform program). Yeltsin, awaiting implementation of his privatization

Privatization (also privatisation in British English) can mean several different things, most commonly referring to moving something from the public sector into the private sector. It is also sometimes used as a synonym for deregulation when ...

program, demanded that parliament reinstate his decree powers (only parliament had the authority to replace or amend the constitution). But in the Russian Congress of People's Deputies and in the Supreme Soviet, the deputies refused to adopt a new constitution that would enshrine the scope of presidential powers demanded by Yeltsin into law.

Another cause of conflict also called repeated refusal of the Congress of People's Deputies to ratify the Belavezh Accords on the termination of the existence of the USSR and to exclude from the text of the Constitution of the RSFSR of 1978 references to the Constitution and laws of the USSR.

Seventh Congress of People's Deputies

During its December session, the parliament clashed with Yeltsin on a number of issues, and the conflict came to a head on 9 December when the parliament refused to confirm

During its December session, the parliament clashed with Yeltsin on a number of issues, and the conflict came to a head on 9 December when the parliament refused to confirm Yegor Gaidar

Yegor Timurovich Gaidar (russian: link=no, Его́р Тиму́рович Гайда́р; ; 19 March 1956 – 16 December 2009) was a Soviet and Russian economist, politician, and author, and was the Acting Prime Minister of Russia from 15 Jun ...

, the widely unpopular architect of Russia's "shock therapy

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is a psychiatric treatment where a generalized seizure (without muscular convulsions) is electrically induced to manage refractory mental disorders.Rudorfer, MV, Henry, ME, Sackeim, HA (2003)"Electroconvulsive the ...

" market liberalisations, as prime minister. The parliament refused to nominate Gaidar, demanding modifications of the economic program and directed the Central Bank, which was under the parliament's control, to continue issuing credits to enterprises to keep them from shutting down.

In an angry speech the next day on 10 December, Yeltsin accused the Congress of blocking the government's reforms and suggested the people decide on a referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

, "which course do the citizens of Russia support? The course of the President, a course of transformations, or the course of the Congress, the Supreme Soviet and its Chairman, a course towards folding up reforms, and ultimately towards the deepening of the crisis." Parliament responded by voting to take control of the army.

On 12 December, Yeltsin and parliament speaker Khasbulatov agreed on a compromise that included the following provisions: (1) a national referendum on framing a new Russian constitution to be held in April 1993; (2) most of Yeltsin's emergency powers were extended until the referendum; (3) the parliament asserted its right to nominate and vote on its own choices for prime minister; and (4) the parliament asserted its right to reject the president's choices to head the Defense, Foreign Affairs, Interior, and Security ministries. Yeltsin nominated Viktor Chernomyrdin

Viktor Stepanovich Chernomyrdin (russian: Ви́ктор Степа́нович Черномы́рдин, ; 9 April 19383 November 2010) was a Soviet and Russian politician and businessman. He was the Minister of Gas Industry of the Soviet Unio ...

to be prime minister on 14 December, and the parliament confirmed him.

Yeltsin's December 1992 compromise with the seventh Congress of the People's Deputies temporarily backfired. Early 1993 saw increasing tension between Yeltsin and the parliament over the language of the referendum and power sharing. In a series of collisions over policy, the congress whittled away the president's extraordinary powers, which it had granted him in late 1991. The legislature, marshaled by Speaker Ruslan Khasbulatov

Ruslan Imranovich Khasbulatov (russian: link=no, Русла́н Имранович Хасбула́тов, ce, Хасбола́ти Имра́ни кIант Руслан) (born November 22, 1942) is a Russian economist and politician and the ...

, began to sense that it could block and even defeat the president. The tactic that it adopted was gradually to erode presidential control over the government. In response, the president called a referendum on a constitution for 11 April.

Eighth congress

The eighth Congress of People's Deputies opened on 10 March 1993Хроника Второй Российской республики (январь 1993 — сентябрь 1993 гг.)/ref> with a strong attack on the president by Khasbulatov, who accused Yeltsin of acting unconstitutionally. In mid-March, an emergency session of the Congress of People's Deputies voted to amend the constitution, strip Yeltsin of many of his powers, and cancel the scheduled April referendum, again opening the door to legislation that would shift the balance of power away from the president. The president stalked out of the congress.

Vladimir Shumeyko

Vladimir Filippovich Shumeyko (also spelled Shumeiko) (russian: link=no, Влади́мир Фили́ппович Шуме́йко) (born February 10, 1945) is a Russian political figure.

In November 1991, Vladimir Shumeyko was appointed deput ...

, first deputy prime minister, declared that the referendum would go ahead, but on 25 April.

The parliament was gradually expanding its influence over the government. On 16 March, the president signed a decree that conferred Cabinet rank on Viktor Gerashchenko

Viktor Vladimirovich Gerashchenko (russian: Ви́ктор Влади́мирович Гера́щенко; born 21 December 1937 Leningrad, Soviet Union), nicknamed ''Gerakl'' (the Russian version of Heracles, or sometimes of debacle), was the Gos ...

, chairman of the central bank, and three other officials; this was in accordance with the decision of the eighth congress that these officials should be members of the government. The congress' ruling, however, had made it clear that as ministers they would continue to be subordinate to parliament. In general, the parliament's lawmaking activity decreased in 1993, as its agenda increasingly became dominated by efforts to increase the parliamentarian powers and reduce those of the president.

"Special regime"

The president's response was dramatic. On 20 March, Yeltsin addressed the nation directly on television, declaring that he had signed a decree on a "special regime" ("Об особом порядке управления до преодоления кризиса власти"), under which he would assume extraordinary executive power pending the results of a referendum on the timing of new legislative elections, on a new constitution, and on public confidence in the president and vice-president. Yeltsin also bitterly attacked the parliament, accusing the deputies of trying to restore the Soviet-era order. Soon after Yeltsin's televised address,Valery Zorkin

Valery Dmitrievich Zorkin (russian: Вале́рий Дми́триевич Зо́рькин) is the first and the current Chairman of the Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation.

Zorkin was born on 18 February 1943 in Konstantinovka, ...

(Chairman of the Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these prin ...

), Yuri Voronin (first vice-chairman of the Supreme Soviet), Alexander Rutskoy

Alexander Vladimirovich Rutskoy (russian: Александр Владимирович Руцкой; born 16 September 1947) is a Russian politician and a former Soviet military officer, Major General of Aviation (1991). He served as the only vic ...

and Valentin Stepankov

Valentin Stepankov (born 1951) was the first prosecutor general of the Russian Federation.

He once condemned an action by Boris Yeltsin

Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin ( rus, Борис Николаевич Ельцин, p=bɐˈrʲis nʲɪkɐˈ ...

(Prosecutor General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

) made an address, publicly condemning Yeltsin's declaration as unconstitutional. On 23 March, though not yet possessing the signed document, the Constitutional Court

A constitutional court is a high court that deals primarily with constitutional law. Its main authority is to rule on whether laws that are challenged are in fact unconstitutional, i.e. whether they conflict with constitutionally established ...

ruled that some of the measures proposed in Yeltsin's TV address were unconstitutional. However, the decree itself, that was only published a few days later, did not contain unconstitutional steps.

Ninth congress

The ninth congress, which opened on 26 March, began with an extraordinary session of the Congress of People's Deputies taking up discussions of emergency measures to defend the constitution, including

The ninth congress, which opened on 26 March, began with an extraordinary session of the Congress of People's Deputies taking up discussions of emergency measures to defend the constitution, including impeachment

Impeachment is the process by which a legislative body or other legally constituted tribunal initiates charges against a public official for misconduct. It may be understood as a unique process involving both political and legal elements.

In ...

of President Yeltsin. Yeltsin conceded that he had made mistakes and reached out to swing voters in parliament. Yeltsin narrowly survived an impeachment vote on March 28, votes for impeachment falling 72 short of the 689 votes needed for a 2/3 majority. The similar proposal to dismiss Ruslan Khasbulatov, the chairman of the Supreme Soviet was defeated by a wider margin (339 in favour of the motion), though 614 deputies had initially been in favour of including the re-election of the chairman in the agenda, a tell-tale sign of the weakness of Khasbulatov's own positions (517 votes for would have sufficed to dismiss the speaker).

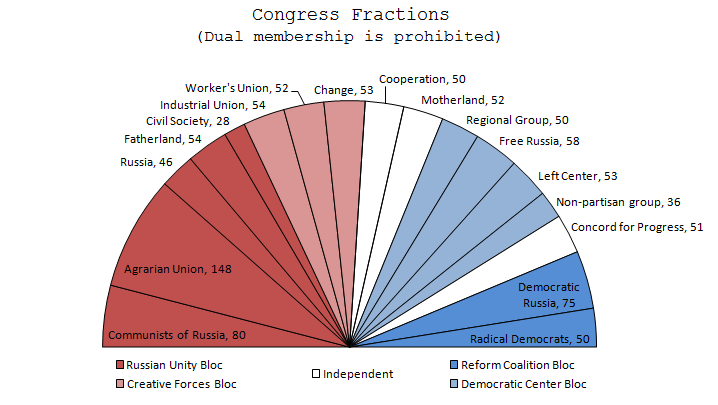

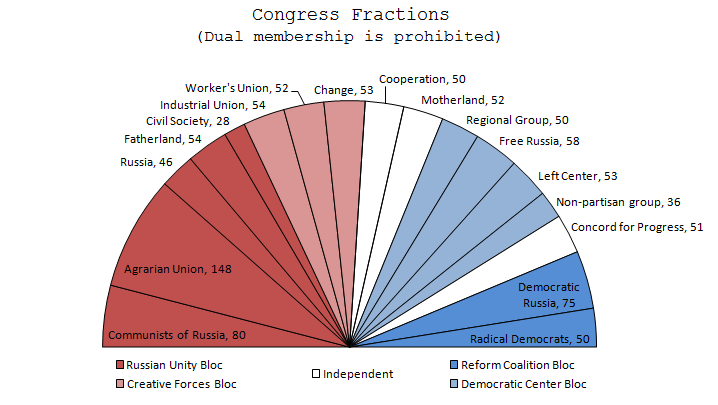

By the time of the ninth Congress, the legislative branch was dominated by the joint communist-nationalist Russian Unity bloc, which included representatives of the CPRF

, anthem =

, seats1_title = Seats in the State Duma

, seats1 =

, seats2_title = Seats in the Federation Council

, seats2 =

, seats3_title = Governors

, seats3 =

, seats4_title ...

and the Fatherland faction (communists, retired military personnel, and other deputies of a socialist orientation), Agrarian Union, and the faction "Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

" led by Sergey Baburin. These groups, together with more 'centrist' groups (e.g. 'Change' (''Смена'')), left the opposing bloc of Yeltsin supporters ('Democratic Russia', 'Radical democrats') in a clear minority.

National referendum

The referendum would go ahead, but since the impeachment vote failed, the Congress of People's Deputies sought to set new terms for a popular referendum. The legislature's version of the referendum asked whether citizens had confidence in Yeltsin, approved of his reforms, and supported early presidential and legislative elections. The parliament voted that in order to win, the president would need to obtain 50 percent of the whole electorate, rather than 50 percent of those actually voting, to avoid an early presidential election. This time, the Constitutional Court supported Yeltsin and ruled that the president required only a simple majority on two issues: confidence in him, and economic and social policy; he would need the support of half the electorate in order to call new parliamentary and presidential elections. On 25 April, a majority of voters expressed confidence in the president and called for new legislative elections. Yeltsin termed the results a mandate for him to continue in power. Before the referendum, Yeltsin had promised to resign, if the electorate failed to express confidence in his policies. Although this permitted the president to declare that the population supported him, not the parliament, Yeltsin lacked a constitutional mechanism to implement his victory. As before, the president had to appeal to the people over the heads of the legislature. On1 May

Events Pre-1600

* 305 – Diocletian and Maximian retire from the office of Roman emperor.

* 880 – The Nea Ekklesia is inaugurated in Constantinople, setting the model for all later cross-in-square Orthodox churches.

*1169 – N ...

, antigovernment protests organized by the hardline opposition turned violent. Numerous deputies of the Supreme Soviet took part in organizing the protest and in its course. One OMON

OMON (russian: ОМОН – Отряд Мобильный Особого Назначения , translit = Otryad Mobil'nyy Osobogo Naznacheniya , translation = Special Purpose Mobile Unit, , previously ru , Отряд Милиции Осо� ...

police officer suffered fatal injuries during the riot. As a reaction, a number of the representatives of Saint Petersburg intelligentia (e.g., Oleg Basilashvili

Oleg Valerianovich Basilashvili (russian: Оле́г Валериа́нович Басилашви́ли; ka, ოლეგ ბასილაშვილი, ; born 26 September 1934) is a Soviet and Russian stage and film actor. People's Artist ...

, Alexey German, Boris Strugatsky

The brothers Arkady Natanovich Strugatsky (russian: Аркадий Натанович Стругацкий; 28 August 1925 – 12 October 1991) and Boris Natanovich Strugatsky ( ru , Борис Натанович Стругацкий; 14 A ...

) sent a petition to president Yeltsin, urging "putting an end to the street criminality under political slogans".

Constitutional convention

On 29 April 1993,Boris Yeltsin

Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin ( rus, Борис Николаевич Ельцин, p=bɐˈrʲis nʲɪkɐˈla(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ ˈjelʲtsɨn, a=Ru-Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin.ogg; 1 February 1931 – 23 April 2007) was a Soviet and Russian politician wh ...

released the text of his proposed constitution to a meeting of government ministers and leaders of the republics and regions, according to ITAR-TASS

The Russian News Agency TASS (russian: Информацио́нное аге́нтство Росси́и ТАСС, translit=Informatsionnoye agentstvo Rossii, or Information agency of Russia), abbreviated TASS (russian: ТАСС, label=none) ...

. On 12 May Yeltsin called for a special assembly of the Federation Council, which had been formed 17 July 1990 within the office of the Chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the Russian SFSR, and other representatives, including political leaders from a wide range of government institutions, regions, public organizations, and political parties, to finalize a draft for a new constitution from 5–10 June, and was followed by a similar decree 21 May.

After much hesitation, the Constitutional Committee of the Congress of People's Deputies decided to participate and present its own draft constitution. Of course, the two main drafts contained contrary views of legislative-executive relations.

Some 700 representatives at the conference ultimately adopted a draft constitution on 12 July that envisaged a bicameral legislature and the dissolution of the congress. But because the convention's draft of the constitution would dissolve the congress, there was little likelihood that the congress would vote itself out of existence. The Supreme Soviet immediately rejected the draft and declared that the Congress of People's Deputies was the supreme lawmaking body and hence would decide on the new constitution.

July–September

The parliament was active in July–August, while the president was on vacation, and passed a number of decrees that revised economic policy in order to "end the division of society." It also launched investigations of key advisers of the president, accusing them of corruption. The president returned in August and declared that he would deploy all means, including circumventing the constitution, to achieve new parliamentary elections. In July, theConstitutional Court of the Russian Federation

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these prin ...

confirmed the election of Pyotr Sumin to head the administration of the Chelyabinsk oblast

Chelyabinsk Oblast (russian: Челя́бинская о́бласть, ''Chelyabinskaya oblast'') is a federal subject (an oblast) of Russia in the Ural Mountains region, on the border of Europe and Asia. Its administrative center is the city ...

, something that Yeltsin had refused to accept. As a result, a situation of dual power existed in that region from July to October in 1993, with two administrations claiming legitimacy simultaneously. Another conflict involved the decision of the Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation regarding the regional presidency in Mordovia

The Republic of Mordovia (russian: Респу́блика Мордо́вия, r=Respublika Mordoviya, p=rʲɪsˈpublʲɪkə mɐrˈdovʲɪjə; mdf, Мордовия Республиксь, ''Mordovija Respublikś''; myv, Мордовия Рес ...

. The court delegated the question of legality of abolishing the post of the region's president to the Constitutional Court of Mordovia. As a result, popularly elected President Vasily Guslyannikov

Vasily Dmitriyevich Guslyannikov (russian: Василий Дмитриевич Гуслянников; born 21 April 1949) is a Russian retired politician, who served as first and only President of Mordovia in 1991–1993.

Biography

Vasily Gusl ...

, member of the pro-Yeltsin Democratic Russia movement, lost his position. Thereafter, the state news agency (ITAR-TASS

The Russian News Agency TASS (russian: Информацио́нное аге́нтство Росси́и ТАСС, translit=Informatsionnoye agentstvo Rossii, or Information agency of Russia), abbreviated TASS (russian: ТАСС, label=none) ...

) ceased to report on a number of Constitutional Court decisions.

The Supreme Soviet also tried to further foreign policies that differed from Yeltsin's line. Thus, on 9 July 1993, it passed resolutions on Sevastopol

Sevastopol (; uk, Севасто́поль, Sevastópolʹ, ; gkm, Σεβαστούπολις, Sevastoúpolis, ; crh, Акъя́р, Aqyár, ), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea, and a major port on the Black Sea ...

, "confirming the Russian federal status" of the city. Ukraine saw its territorial integrity at stake and filed a complaint to the Security Council of the UN. Yeltsin condemned the resolution of the Supreme Soviet.

In August 1993, a commentator reflected on the situation as follows: "The President issues decrees as if there were no Supreme Soviet, and the Supreme Soviet suspends decrees as if there were no President." (Izvestiya

''Izvestia'' ( rus, Известия, p=ɪzˈvʲesʲtʲɪjə, "The News") is a daily broadsheet newspaper in Russia. Founded in 1917, it was a newspaper of record in the Soviet Union until the Soviet Union's dissolution in 1991, and describes i ...

, August 13, 1993).

The president launched his offensive on 1 September when he attempted to suspend Vice President Rutskoy, a key adversary. Rutskoy, elected on the same ticket as Yeltsin in 1991, was the president's automatic successor. A presidential spokesman said that he had been suspended because of "accusations of corruption", due to alleged corruption charges, which was not further confirmed. On 3 September, the Supreme Soviet rejected Yeltsin's suspension of Rutskoy and referred the question to the Constitutional Court.

Two weeks later Yeltsin declared that he would agree to call early presidential elections provided that the parliament also called elections. The parliament ignored him. On 18 September, Yeltsin then named Yegor Gaidar, who had been forced out of office by parliamentary opposition in 1992, a deputy prime minister and a deputy premier for economic affairs. This appointment was unacceptable to the Supreme Soviet.

Siege and assault

On 21 September, Yeltsin declared the Congress of People's Deputies and theSupreme Soviet

The Supreme Soviet (russian: Верховный Совет, Verkhovny Sovet, Supreme Council) was the common name for the legislative bodies (parliaments) of the Soviet socialist republics (SSR) in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) ...

dissolved; this act was in contradiction with a number of articles of the Constitution of 1978 (as amended 1989–1993), such as, Article 1216The Congress enabled this formerly-suspended amendment after it had failed to impeach Yeltsin after his declaration of a 'Special Rule' in March 1993 which stated:

In his television appearance to the citizens of Russia, President Yeltsin argued for the decree nr 1400 as follows:

Already more than a year attempts were made to reach a compromise with the corps of deputies, with the Supreme Soviet. Russians know well that how many steps were taken by my side during the last congresses and between them. ... The last days destroyed once and for all the hopes for a resurrection of at least some constructive cooperation. The majority of the Supreme Soviet goes directly against the will of the Russian people. A course is taken in favour of the weakening of the president and ultimately his removal from office, of the disorganization of the work of the government; during the last months, dozens of antipopular decisions have been prepared and passed. ... Lots of these are deliberately planned to worsen the situation in Russia. The more flagrant ones are the so-called economic policies of the Supreme Soviet, its decisions on the budget, privatization, there are many others that deepen the crisis, cause colossal damage to the country. All attempts of the government undertaken to at least somewhat alleviate the economic situation meet incomprehension. There is hardly a day when the cabinet of ministers is not harassed, its hands are not being tied. And this happens in a situation of a deepest economic crisis. The Supreme Soviet has stopped taking into account the decrees of the president, his amendments of the legislative projects, even his constitutional veto rights. Constitutional reform has practically been pared down. The process of creating rule of law in Russia has essentially been disorganized. To the contrary, what is going on is a deliberate reduction of the legal basis of the young Russian state that is even without this weak. The legislative work became a weapon of political struggle. Laws, that Russia urgently needs, are not being passed for years. ...At the same time, Yeltsin repeated his announcement of a constitutional referendum, and new legislative elections for December. He also repudiated the Constitution of 1978, declaring that it had been replaced with one that gave him extraordinary executive powers. According to the new plan, the lower house would have 450 deputies and be called the

For a long time already, most of the sessions of the Supreme Soviet take place with the infringements of the elementary procedures and order... A cleansing of committees and commissions is taking place. Everyone who does not show up personal loyalty to its leader is being mercilessly expelled from the Supreme Soviet, from its presidium. ... This is all a bitter evidence of the fact that the Supreme Soviet as a state institution is currently in a state of decay ... . The power in the Supreme Soviet has been captured by a group of persons who have turned it into an HQ of the intransigent opposition. ... The only way how to overcome the paralysis of the state authority in the Russian Federation is its fundamental renewal on the basis of the principles of popular power and constitutionality. The constitution currently in force does not allow to do this. The constitution in force also does not provide for a procedure of passing a new constitution, that would provide for a worthy exit from the crisis of state power. I as the guarantor of the security of our state have to propose an exit from this deadlock, have to break this vicious circle.

State Duma

The State Duma (russian: Госуда́рственная ду́ма, r=Gosudárstvennaja dúma), commonly abbreviated in Russian as Gosduma ( rus, Госду́ма), is the lower house of the Federal Assembly of Russia, while the upper house ...

, the name of the Russian legislature before the Bolshevik Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolsheviks, Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was ...

in 1917. The Federation Council

The Federation Council (russian: Сове́т Федера́ции – ''Soviet Federatsii'', common abbreviation: Совфед – ''Sovfed''), or Senate (officially, starting from July 1, 2020) ( ru , Сенат , translit = Senat), is th ...

, which would bring together representatives from the 89 subdivisions of the Russian Federation, would assume the role of an upper house. Yeltsin claimed that by dissolving the Russian parliament in September 1993 he was clearing the tracks for a rapid transition to a functioning market economy. With this pledge, he received strong backing from the leading powers of the West. Yeltsin enjoyed a strong relationship with the Western powers, particularly the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, but the relationship made him unpopular with many Russians. In Russia, the Yeltsin side had control over television, where hardly any pro-parliament views were expressed during the September–October crisis.

Parliament purports to impeach Yeltsin as president

Rutskoy called Yeltsin's move a step toward a ''coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

''. The next day, the Constitutional Court held that Yeltsin had violated the constitution and could be impeached. During an all-night session, chaired by Khasbulatov, parliament declared the president's decree null and void. Rutskoy was proclaimed acting president until new elections. He dismissed the key ministers Pavel Grachev

Pavel Sergeyevich Grachev (russian: Па́вел Серге́евич Грачё́в; 1 January 1948 – 23 September 2012), sometimes transliterated as Grachov or Grachyov, was a Russian Army General and the Defence Minister of the Russian Fed ...

(defense), Nikolay Golushko (security), and Viktor Yerin

Viktor Fyodorovich Yerin (russian: Виктор Фёдорович Ерин, 17 January 1944, Kazan, Russian SFSR – 19 March 2018) was a Russian politician and General of the Army who served as the country's first post-Soviet Minister of Intern ...

(interior). Russia now had two presidents and two ministers of defense, security, and interior. It was dual power in earnest. Although Gennady Zyuganov

Gennady Andreyevich Zyuganov (russian: Генна́дий Андре́евич Зюга́нов; born 26 June 1944) is a Russian politician, who has been the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation and served as ...

and other top leaders of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation

, anthem =

, seats1_title = Seats in the State Duma

, seats1 =

, seats2_title = Seats in the Federation Council

, seats2 =

, seats3_title = Governors

, seats3 =

, seats4_title ...

did not participate in the events, individual members of communist organizations actively supported the parliament.

On 23 September, with the observance of a quorum, the Congress of People's Deputies was convened (the quorum was 638). Congress purported to impeach Yeltsin. The same day, Yeltsin announced presidential elections for June 1994.

On 24 September, the Congress of People's Deputies voted to hold simultaneous parliamentary and presidential elections by March 1994. Yeltsin scoffed at the parliament-backed proposal for simultaneous elections, and responded the next day by cutting off electricity, phone service, and hot water in the parliament building.

Mass protests and the barricading of the parliament

Yeltsin also sparked popular unrest with his dissolution of a Congress and parliament increasingly opposed to hisneoliberal

Neoliberalism (also neo-liberalism) is a term used to signify the late 20th century political reappearance of 19th-century ideas associated with free-market capitalism after it fell into decline following the Second World War. A prominent fa ...

economic reforms. Tens of thousands of Russians marched in the streets of Moscow seeking to bolster the parliamentary cause. The demonstrators were protesting against the deteriorating living conditions. Since 1989, the GDP

Gross domestic product (GDP) is a monetary measure of the market value of all the final goods and services produced and sold (not resold) in a specific time period by countries. Due to its complex and subjective nature this measure is ofte ...

had been declining, corruption

Corruption is a form of dishonesty or a criminal offense which is undertaken by a person or an organization which is entrusted in a position of authority, in order to acquire illicit benefits or abuse power for one's personal gain. Corruption m ...

was rampant, violent crime

A violent crime, violent felony, crime of violence or crime of a violent nature is a crime in which an offender or perpetrator uses or threatens to use harmful force upon a victim. This entails both crimes in which the violence, violent act is t ...

was skyrocketing, medical services were collapsing and life expectancy

Life expectancy is a statistical measure of the average time an organism is expected to live, based on the year of its birth, current age, and other demographic factors like sex. The most commonly used measure is life expectancy at birth ...

falling. Yeltsin was also increasingly getting the blame.IBID It is still hotly debated among Western economists, social scientists, and policy-makers as to whether or not the IMF, World Bank, and U.S. Treasury Department-backed reform policies adopted in Russia, often called "shock therapy

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is a psychiatric treatment where a generalized seizure (without muscular convulsions) is electrically induced to manage refractory mental disorders.Rudorfer, MV, Henry, ME, Sackeim, HA (2003)"Electroconvulsive the ...

," were responsible for Russia's poor record of economic performance in the 1990's, or rather, that Yeltsin had not gone far enough.

Under the Western-backed economic program adopted by Yeltsin, the Russian government took several radical measures at once that were supposed to stabilize the economy by bringing state spending and revenues into balance and by letting market demand

In economics, demand is the quantity of a goods, good that consumers are willing and able to purchase at various prices during a given time. The relationship between price and quantity demand is also called the demand curve. Demand for a specifi ...

determine the prices and supply of goods.

Under the reforms, the government let most prices float, raised taxes, and cut back sharply on spending in industry and construction. These policies caused widespread hardship as many state enterprise

A state-owned enterprise (SOE) is a government entity which is established or nationalised by the ''national government'' or ''provincial government'' by an executive order or an act of legislation in order to earn profit for the governmen ...

s found themselves without orders or financing. The rationale of the program was to squeeze the built-in inflationary pressure out of the economy so that the newly privatized producers would begin making sensible decisions about production, pricing and investment instead of chronically overusing resources, as in the Soviet era

The history of Soviet Russia and the Soviet Union (USSR) reflects a period of change for both Russia and the world. Though the terms "Soviet Russia" and "Soviet Union" often are synonymous in everyday speech (either acknowledging the dominance ...

. By letting the market rather than central planners determine prices, product mixes, output levels, and the like, the reformers intended to create an incentive structure in the economy where efficiency and risk would be rewarded and waste and carelessness were punished. Removing the causes of chronic inflation

Chronic inflation is an economic phenomenon occurring when a country experiences high inflation for a prolonged period (several years or decades) due to continual increases in the money supply among other things. In countries with chronic infla ...

, the reform's architects argued, was a precondition for all other reforms. Hyperinflation

In economics, hyperinflation is a very high and typically accelerating inflation. It quickly erodes the real value of the local currency, as the prices of all goods increase. This causes people to minimize their holdings in that currency as t ...

would wreck both democracy and economic progress, they argued; only by stabilizing the state budget could the government proceed to restructure the economy. A similar reform program had been adopted in Poland in January 1990, with generally favorable results. However, Western critics of Yeltsin's reform, most notably Joseph Stiglitz

Joseph Eugene Stiglitz (; born February 9, 1943) is an American New Keynesian economist, a public policy analyst, and a full professor at Columbia University. He is a recipient of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences (2001) and the Joh ...

and Marshall Goldman

Marshall Irwin Goldman (July 26, 1930 – August 2, 2017) was an American economist and writer. He was an expert on the economy of the former Soviet Union. Goldman was a professor of economics at Wellesley College and associate director of the Ha ...

(who would have favored a more "gradual" transition to market capitalism) consider policies adopted in Poland ill-suited for Russia, given that the impact of communism on the Polish economy and political culture was far less indelible.

Outside Moscow, the Russian masses overall were confused and disorganized. Nonetheless, some of them also tried to voice their protest, and sporadic strikes took place across Russia. The protesters included supporters of various communist (Labour Russia

Labour Russia (LR or TR; russian: Трудовая Россия; ТР; ''Trudovaya Rossiya'', ''TR'') is a hard-line communist movement in Russia. It was founded in 1991 as a popular movement supporting the Russian Communist Workers Party (RKRP) ...

) and nationalist organizations, including those belonging to the National Salvation Front. A number of armed militants of Russian National Unity

Russian National Unity (RNU; transcribed Russkoe natsionalnoe edinstvo RNE) or All-Russian civic patriotic movement "Russian National Unity" (russian: Всероссийское общественное патриотическое движен� ...

took part in the defense of the Russian White House

The White House ( rus, Белый дом, r=Bely dom, p=ˈbʲɛlɨj ˈdom; officially The House of the Government of the Russian Federation, rus, Дом Правительства Российской Федерации, r=Dom pravitelstva Ross ...

, as reportedly did veterans of Tiraspol

Tiraspol or Tirișpolea ( ro, Tiraspol, Moldovan Cyrillic: Тираспол, ; russian: Тира́споль, ; uk, Тирасполь, Tyraspol') is the capital of Transnistria (''de facto''), a breakaway state of Moldova, where it is the th ...

and Riga

Riga (; lv, Rīga , liv, Rīgõ) is the capital and largest city of Latvia and is home to 605,802 inhabitants which is a third of Latvia's population. The city lies on the Gulf of Riga at the mouth of the Daugava river where it meets the Ba ...

OMON

OMON (russian: ОМОН – Отряд Мобильный Особого Назначения , translit = Otryad Mobil'nyy Osobogo Naznacheniya , translation = Special Purpose Mobile Unit, , previously ru , Отряд Милиции Осо� ...

. The presence of Transnistrian

Transnistria, officially the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (PMR), is an unrecognised breakaway state that is internationally recognised as a part of Moldova. Transnistria controls most of the narrow strip of land between the Dniester riv ...

forces, including the KGB

The KGB (russian: links=no, lit=Committee for State Security, Комитет государственной безопасности (КГБ), a=ru-KGB.ogg, p=kəmʲɪˈtʲet ɡəsʊˈdarstvʲɪn(ː)əj bʲɪzɐˈpasnəsʲtʲɪ, Komitet gosud ...

detachment ' Dnestr', stirred General Alexander Lebed

Lieutenant General Alexander Ivanovich Lebed (russian: Алекса́ндр Ива́нович Ле́бедь, link=no; 20 April 1950 – 28 April 2002) was a Soviet and Russian military officer and politician who held senior positions in the Ai ...

to protest against Transnistrian interference in Russia's internal affairs.

On 28 September, Moscow saw the first bloody clashes between the special police and anti-Yeltsin demonstrators. Also on the same day, the Russian Interior Ministry

The Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Russian Federation (MVD; russian: Министерство внутренних дел (МВД), ''Ministerstvo vnutrennikh del'') is the interior ministry of Russia.

The MVD is responsible for law enfor ...

moved to seal off the parliament building. Barricades and wire were put around the building. On 1 October, the Interior Ministry estimated that 600 fighting men with a large cache of arms had joined Yeltsin's political opponents in the parliament building.

Storming of the television premises

The Congress of People's Deputies still did not discount the prospect of a compromise with Yeltsin. The Russian Orthodox Church acted as a host to desultory discussions between representatives of the Congress and the president. The negotiations with theRussian Orthodox

Russian Orthodoxy (russian: Русское православие) is the body of several churches within the larger communion of Eastern Orthodox Christianity, whose liturgy is or was traditionally conducted in Church Slavonic language. Most ...

Patriarch Alexy II

Patriarch Alexy II (or Alexius II, russian: link=no, Патриарх Алексий II; secular name Aleksei Mikhailovich Ridiger russian: link=no, Алексе́й Миха́йлович Ри́дигер; 23 February 1929 – 5 December ...

as mediator

Mediator may refer to:

*A person who engages in mediation

*Business mediator, a mediator in business

* Vanishing mediator, a philosophical concept

* Mediator variable, in statistics

Chemistry and biology

*Mediator (coactivator), a multiprotein ...

continued until 2 October. On the afternoon of 3 October, the Moscow Municipal Militsiya failed to control a demonstration near the White House, and the political impasse developed into armed conflict.

On 2 October, supporters of parliament constructed barricades and blocked traffic on Moscow's main streets. Rutskoy signed a decree that had no practical consequences on the release of Viktor Chernomyrdin from the post of Prime Minister.

On the afternoon of 3 October, armed opponents of Yeltsin successfully stormed the police cordon around the White House territory, where the Russian parliament was barricaded. Paramilitaries from factions supporting the parliament, as well as a few units of the internal military (armed forces normally reporting to the Ministry of Interior), supported the Supreme Soviet.

Rutskoy greeted the crowds from the White House balcony, and urged them to form battalions and to go on to seize the mayor's office and the national television center at Ostankino. Khasbulatov also called for the storming of the Kremlin and imprisoning "the criminal and usurper Yeltsin" in Matrosskaya Tishina

Federal State Institution IZ-77/1 of the Office of the Federal Penitentiary Service of Russia in the City of Moscow is a prison located in the Sokolniki District of Moscow, Russia. The facility is commonly known as Matrosskaya Tishina (russian: ...

. At 16:00 Yeltsin signed a decree declaring a state of emergency in Moscow.

On the evening of 3 October, after taking the mayor's office located in the former Comecon

The Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (, ; English abbreviation COMECON, CMEA, CEMA, or CAME) was an economic organization from 1949 to 1991 under the leadership of the Soviet Union that comprised the countries of the Eastern Bloc along wi ...

HQ nearby, pro-parliament demonstrators and gunmen led by General Albert Makashov

Colonel General Albert Mikhailovich Makashov (russian: Альберт Михайлович Макашóв; born 12 June 1938) is a Russian officer and a nationalist- communist politician.

Biography

Makashov was born in Levaya Rossosh, Voronezh ...

moved toward Ostankino, the television center. But the pro-parliament crowds were met by Militsiya

''Militsiya'' ( rus, милиция, , mʲɪˈlʲitsɨjə) was the name of the police forces in the Soviet Union (until 1991) and in several Eastern Bloc countries (1945–1992), as well as in the non-aligned SFR Yugoslavia (1945–1992). The ...

and OMON

OMON (russian: ОМОН – Отряд Мобильный Особого Назначения , translit = Otryad Mobil'nyy Osobogo Naznacheniya , translation = Special Purpose Mobile Unit, , previously ru , Отряд Милиции Осо� ...

forces who took positions in and around the TV complex. A pitched battle followed. Part of the TV center was significantly damaged. Television stations went off the air and 46 people were killed, including Terry Michael Duncan, an American lawyer, who was in Moscow to establish a law firm and was killed while attempting to help the wounded.Quiet American, by A. Bratersky, for

Izvestia

''Izvestia'' ( rus, Известия, p=ɪzˈvʲesʲtʲɪjə, "The News") is a daily broadsheet newspaper in Russia. Founded in 1917, it was a newspaper of record in the Soviet Union until the Soviet Union's dissolution in 1991, and describes ...

, October 2005 (in Russian) Before midnight, the Interior Ministry's units had turned back the parliament loyalists.

When broadcasting resumed late in the evening, vice-premier Yegor Gaidar

Yegor Timurovich Gaidar (russian: link=no, Его́р Тиму́рович Гайда́р; ; 19 March 1956 – 16 December 2009) was a Soviet and Russian economist, politician, and author, and was the Acting Prime Minister of Russia from 15 Jun ...

called on television for a meeting in support of democracy and President Yeltsin "so that the country would not be turned yet again into a huge concentration camp". A number of people with different political convictions and interpretations over the causes of the crisis (such as Grigory Yavlinsky

Grigory Alekseyevich Yavlinsky ( Russian: Григо́рий Алексе́евич Явли́нский; born 10 April 1952) is a Russian economist and politician. He authored the 500 Days Program, a plan for the transition of the Soviet regim ...

, Alexander Yakovlev

Alexander Nikolayevich Yakovlev (russian: Алекса́ндр Никола́евич Я́ковлев; 2 December 1923 – 18 October 2005) was a Soviet and Russian politician, diplomat, and historian. A member of the Politburo and Secreta ...

, Yuri Luzhkov Yuri may refer to:

People and fictional characters

Given name

*Yuri (Slavic name), the Slavic masculine form of the given name George, including a list of people with the given name Yuri, Yury, etc.

* Yuri (Japanese name), also Yūri, feminine Ja ...

, Ales Adamovich

Aleksandr Mikhailovich Adamovich ( be, Аляксандр Міхайлавіч Адамовіч, translit=Aliaksandr Michailavič Adamovič, russian: Алекса́ндр Миха́йлович Адамо́вич; 3 September 1927 – 26 January ...

, and Bulat Okudzhava

Bulat Shalvovich Okudzhava (russian: link=no, Булат Шалвович Окуджава; ka, ბულატ ოკუჯავა; hy, Բուլատ Օկուջավա; May 9, 1924 – June 12, 1997) was a Soviet and Russian poet, writer, musici ...

) also appealed to support the President. Similarly, the Civic Union bloc of 'constructive opposition' issued a statement accusing the Supreme Soviet of having crossed the border separating political struggle from criminality. Several hundred of Yeltsin's supporters spent the night in the square in front of the Moscow City Hall preparing for further clashes, only to learn in the morning of 4 October that the army was on their side.

The Ostankino killings went unreported by Russian state television. The only independent Moscow radio station's studios were burnt. Two French, one British, and one American journalist were killed by sniper fire during the massacre. A fifth journalist died from a heart attack. The press and broadcast news were censored starting on 4 October, and by the middle of October, prior censorship was replaced by punitive measures.pp. 36 ff, ''Restoration in Russia: Why Capitalism Failed'', by Boris Kagarlitsky. Verso, 1995Google Books excerpt

/ref>

Storming of the White House

Between 2–4 October, the position of the army was the deciding factor. The military equivocated for several hours about how to respond to Yeltsin's call for action. By this time dozens of people had been killed and hundreds had been wounded. Rutskoy, as a former general, appealed to some of his ex-colleagues. After all, many officers and especially rank-and-file soldiers had little sympathy for Yeltsin. But the supporters of the parliament did not send any emissaries to the barracks to recruit lower-ranking officer corps, making the fatal mistake of attempting to deliberate only among high-ranking military officials who already had close ties to parliamentary leaders. In the end, a prevailing bulk of the generals did not want to take their chances with a Rutskoy-Khasbulatov regime. Some generals had stated their intention to back the parliament, but at the last moment moved over to Yeltsin's side. The plan of action was proposed by Captain Gennady Zakharov. Ten tanks were to fire at the upper floors of theWhite House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

, with the aim of minimizing casualties but creating confusion and panic amongst the defenders. Five tanks were deployed at Novy Arbat

New Arbat Avenue (russian: link=no, Новый Арбат) is a major street in Moscow running west from Arbatskaya Square on the Boulevard Ring to Novoarbatsky Bridge on the opposite bank of the Moskva River. The modern six-lane avenue (original ...

bridge and the other five at Pavlik Morozov playground, behind the building. Then, special troops of the Vympel

Directorate "V" of the FSB Special Purpose Center, often referred to as Spetsgruppa "V" Vympel ( pennant in Russian, originated from German , and having the same meaning), but also known as KGB Directorate "V", Vega Group, is an elite Russian ...

and Alpha

Alpha (uppercase , lowercase ; grc, ἄλφα, ''álpha'', or ell, άλφα, álfa) is the first letter of the Greek alphabet. In the system of Greek numerals, it has a value of one. Alpha is derived from the Phoenician letter aleph , whic ...

units would storm the parliament premises. According to Yeltsin's bodyguard Alexander Korzhakov

Alexander Vasilyevich Korzhakov (russian: Александр Васильевич Коржаков; born 31 January 1950) is a Russian former KGB general who served as Boris Yeltsin's bodyguard, confidant, and adviser for eleven years. He was ...

, firing on the upper floors was also necessary to scare off snipers.

Those, who went against the peaceful city and unleashed bloody slaughter, are criminals. But this is not only a crime of individualHe also assured the listeners that:bandit Banditry is a type of organized crime committed by outlaws typically involving the threat or use of violence. A person who engages in banditry is known as a bandit and primarily commits crimes such as extortion, robbery, and murder, either as an ...s andpogrom A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russia ...-makers. Everything that took place and is still taking place in Moscow is a pre-planned armed rebellion. It has been organized by Communistrevanchist Revanchism (french: revanchisme, from ''revanche'', " revenge") is the political manifestation of the will to reverse territorial losses incurred by a country, often following a war or social movement. As a term, revanchism originated in 1870s F ...s, Fascist leaders, a part of former deputies, and the representatives of theSoviet The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...s.

Under the cover of negotiations they gathered forces, recruited bandit troops of mercenaries, who were accustomed to murders and violence. A petty gang of politicians attempted by armed force to impose their will on the entire country. The means by which they wanted to govern Russia have been shown to the entire world. These are cynical lies and bribery. These arecobblestone Cobblestone is a natural building material based on cobble-sized stones, and is used for pavement roads, streets, and buildings. Setts, also called Belgian blocks, are often casually referred to as "cobbles", although a sett is distinct fro ...s, sharpened iron rods, automatic weapons and machine guns.

Those, who are waving red flags, again stained Russia with blood. They hoped for the unexpectedness, for the fact that their impudence and unprecedented cruelty will sow fear and confusion.

The fascist-communist armed rebellion in Moscow shall be suppressed within the shortest period. The Russian state has necessary forces for this.By noon, troops entered the White House and began to occupy it, floor by floor. Rutskoy's desperate appeal to Air Force pilots to bomb the Kremlin was broadcast by the

Echo of Moscow

Echo of Moscow (russian: links=no, Эхо Москвы, translit=Ekho Moskvy) was a 24/7 commercial Russian radio station based in Moscow. It broadcast in many Russian cities, some of the former Soviet republics (through partnerships with local ra ...

radio station but went unanswered. He also tried to have the Chairman of the Constitutional Court, Valery Zorkin

Valery Dmitrievich Zorkin (russian: Вале́рий Дми́триевич Зо́рькин) is the first and the current Chairman of the Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation.

Zorkin was born on 18 February 1943 in Konstantinovka, ...

, call the Western embassies to guarantee Rutskoy's and his associates' safety – to no avail. Hostilities were stopped several times to allow some in the White House to leave. By mid-afternoon, popular resistance in the streets was completely suppressed, barring occasional sniper fire.

The "second October Revolution", as mentioned, saw the deadliest street fighting in Moscow since 1917. The official list of the dead, presented on July 27, 1994 by the investigation team of the Prosecutor General's Office of the Russian Federation, includes 147 people: 45 civilians and 1 serviceman in Ostankino, and 77 civilians and 24 military personnel of the Ministry of Defense and the Ministry of Internal Affairs in the "White House area".

Some claim Yeltsin was backed by the military only grudgingly, and only at the eleventh hour. The instruments of coercion gained the most, and they would expect Yeltsin to reward them in the future. A paradigmatic example of this was General Pavel Grachev

Pavel Sergeyevich Grachev (russian: Па́вел Серге́евич Грачё́в; 1 January 1948 – 23 September 2012), sometimes transliterated as Grachov or Grachyov, was a Russian Army General and the Defence Minister of the Russian Fed ...

, who had demonstrated his loyalty during this crisis. Grachev became a key political figure, despite many years of charges that he was linked to corruption within the Russian military.

Public opinion on crisis

The Russian public opinion research instituteVCIOM

Russian Public Opinion Research Center (VTsIOM or VCIOM) ( rus, Всероссийский центр изучения общественного мнения – ВЦИОМ, Vserossiysky tsentr izucheniya obshchestvennogo mneniya) is a state-own ...

, a state-controlled agency, conducted a poll in the aftermath of October 1993 events and found out that 70% of the people polled thought that the use of military force by Yeltsin was justified and 30% thought it was not justified. This support for Yeltsin's actions declined in later years. When VCIOM-A asked the same question in 2010, only 41% agreed with the use of the military, with 59% opposed.

When asked about the main cause of the events of 3–4 October, 46% in the 1993 VCIOM poll blamed Rutskoy and Khasbulatov. However, nine years following the crisis, the most popular culprit was the legacy of Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet politician who served as the 8th and final leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

with 36%, closely followed by Yeltsin's policies with 32%.

Yeltsin's consolidation of power

Immediate aftermath

On 5 October 1993, the newspaper ''Izvestiya

''Izvestia'' ( rus, Известия, p=ɪzˈvʲesʲtʲɪjə, "The News") is a daily broadsheet newspaper in Russia. Founded in 1917, it was a newspaper of record in the Soviet Union until the Soviet Union's dissolution in 1991, and describes i ...

'' published the open letter

An open letter is a Letter (message), letter that is intended to be read by a wide audience, or a letter intended for an individual, but that is nonetheless widely distributed intentionally.

Open letters usually take the form of a letter (mess ...

"Writers demand decisive actions of the government" to the government and President signed by 42 well-known Russian literati and hence called the Letter of Forty-Two The Letter of Forty-Two (russian: Письмо́ сорока́ двух) was an open letter signed by forty-two Russian Intellectual, literati, aimed at Russian society, the president and government, in reaction to the 1993 Russian constitutional c ...

. It was written in reaction to the events and contained the following seven demands:

In the weeks following the storming of the White House, Yeltsin issued a barrage of presidential decrees intended to consolidate his position. On 5 October, Yeltsin banned political leftist and nationalist organizations and newspapers like ''Den, ''Sovetskaya Rossiya'' and ''Pravda'' that had supported the parliament (they would later resume publishing). In an address to the nation on 6 October, Yeltsin also called on those regional Soviets

Soviet people ( rus, сове́тский наро́д, r=sovyétsky naród), or citizens of the USSR ( rus, гра́ждане СССР, grázhdanye SSSR), was an umbrella demonym for the population of the Soviet Union.

Nationality policy in th ...

that had opposed him—by far the majority—to disband. Valery Zorkin

Valery Dmitrievich Zorkin (russian: Вале́рий Дми́триевич Зо́рькин) is the first and the current Chairman of the Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation.

Zorkin was born on 18 February 1943 in Konstantinovka, ...

, chairman of the Constitutional Court, was forced to resign. The chairman of the Federation of Independent Trade Unions was also sacked. The anti-Yeltsin TV broadcast 600 Seconds

''600 Seconds'' (russian: 600 секунд; 1987 to 1993) was an immensely popular TV news program that aired in the Soviet Union and briefly in post-Soviet Russia. It was a nightly broadcast from Leningrad TV with anchor Alexander Nevzorov.

of Alexander Nevzorov

Alexander Glebovich Nevzorov (russian: Алекса́ндр Гле́бович Невзо́ров; born on 3 August 1958) is a Russian (since 2022, also Ukrainian) television journalist, film director and a former member of the Russian State ...

was ultimately closed down.

Yeltsin decreed on 12 October that both houses of parliament would be elected in December. On 15 October, he ordered that a popular referendum be held in December on a new constitution. Rutskoy and Khasbulatov were charged on 15 October with "organizing mass disorders" and imprisoned. On 23 February 1994, the State Duma amnestied all individuals involved in the events of September–October 1993. They were later released in 1994 when Yeltsin's position was sufficiently secure. In early 1995, the criminal proceedings were discontinued and were eventually placed into the archives./ref> "Russia needs order," Yeltsin told the Russian people in a television broadcast in November in introducing his new draft of the constitution, which was to be put to a referendum on 12 December. The new basic law would concentrate sweeping powers in the hands of the president. The bicameral legislature, to sit for only two years, was restricted in crucial areas. The president could choose the prime minister even if the parliament objected and could appoint the military leadership without parliamentary approval. He would head and appoint the members of a new, more powerful security council. If a vote of no confidence in the government was passed, the president would be enabled to keep it in office for three months and could dissolve the parliament if it repeated the vote. The president could veto any bill passed by a simple majority in the lower house, after which a two-thirds majority would be required for the legislation to be passed. The president could not be impeached for contravening the constitution. The central bank would become independent, but the president would need the approval of the State Duma to appoint the bank's governor, who would thereafter be independent of the parliament. At the time, most political observers regarded the draft constitution as shaped by and for Yeltsin and perhaps unlikely to survive him.

End of the first constitutional period

On 12 December, Yeltsin managed to push through his new constitution, creating a strong presidency and giving the president sweeping powers to issue decrees. However, the parliament elected on the same day (with a turnout of about 53%) delivered a stunning rebuke to his neoliberal economic program. Candidates identified with Yeltsin's economic policies were overwhelmed by a huge protest vote, the bulk of which was divided between the Communists (who mostly drew their support from industrial workers, out-of-work bureaucrats, some professionals, and pensioners) and the ultra-nationalists (who drew their support from disaffected elements of the lowermiddle class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. Commo ...

es). Unexpectedly, the most surprising insurgent group proved to be the ultranationalist Liberal Democratic Party led by Vladimir Zhirinovsky

Vladimir Volfovich Zhirinovsky, ''né'' Eidelshtein (russian: link=false, Эйдельштейн) (25 April 1946 – 6 April 2022) was a Russian right-wing populist politician and the leader of the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (LDPR) f ...

. It gained 23% of the vote while the Gaidar led ' Russia's Choice' received 15.5% and the Communist Party of the Russian Federation, 12.4%. LDPR leader, Vladimir Zhirinovsky

Vladimir Volfovich Zhirinovsky, ''né'' Eidelshtein (russian: link=false, Эйдельштейн) (25 April 1946 – 6 April 2022) was a Russian right-wing populist politician and the leader of the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (LDPR) f ...

, alarmed many observers abroad with his neo-fascist

Fascism is a far-right, Authoritarianism, authoritarian, ultranationalism, ultra-nationalist political Political ideology, ideology and Political movement, movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and pol ...

and chauvinist

Chauvinism is the unreasonable belief in the superiority or dominance of one's own group or people, who are seen as strong and virtuous, while others are considered weak, unworthy, or inferior. It can be described as a form of extreme patriotis ...

declarations.

Nevertheless, the referendum marked the end of the constitutional period defined by the constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of Legal entity, entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When ...

adopted by the Russian SFSR

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

in 1978, which was amended many times while Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

was a part of Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet politician who served as the 8th and final leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

's Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

. Although Russia would emerge as a dual presidential-parliamentary system in theory, substantial power would rest in the president's hands. Russia now has a prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

who heads a cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filing ...

and directs the administration

Administration may refer to:

Management of organizations

* Management, the act of directing people towards accomplishing a goal

** Administrative assistant, Administrative Assistant, traditionally known as a Secretary, or also known as an admini ...

, but despite officially following a semi-presidential

A semi-presidential republic, is a republic in which a president exists alongside a prime minister and a cabinet, with the latter two being responsible to the legislature of the state. It differs from a parliamentary republic in that it has a ...

constitutional model, the system is effectively an example of president-parliamentary presidentialism, because the prime minister is appointed, and in effect freely dismissed, by the president.

See also

*History of post-Soviet Russia

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbrella term comprising past events as well ...

* Politics of post-Soviet Russia

*List of attacks on legislatures

The following is a list of attacks on state or national legislature

A legislature is an assembly with the authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country or city. They are often contrasted with the executive and judicial ...

Notes

References

Sources cited

* *Further reading

* * Lehrke, Jesse Paul (2013). "The Transition to National Armies in the Former Soviet Republics, 1988–2005." Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge. See especially p. 163–171 and 194–199. * Ostrovsky, Alexander (2014)Расстрел «Белого дома». Чёрный октябрь 1993. (The shooting of the "White House". Black October 1993.)

— М.: «Книжный мир», 2014. — 640 с. ISBN 978-5-8041-0637-0.

External links

article by Ellen Barry in ''The New York Times'' October 11, 2008 (15th anniversary demonstration)