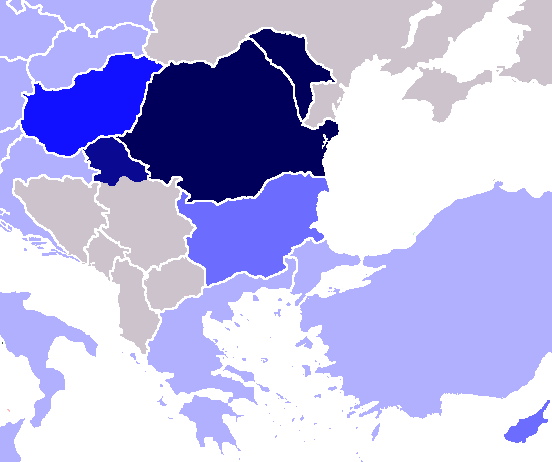

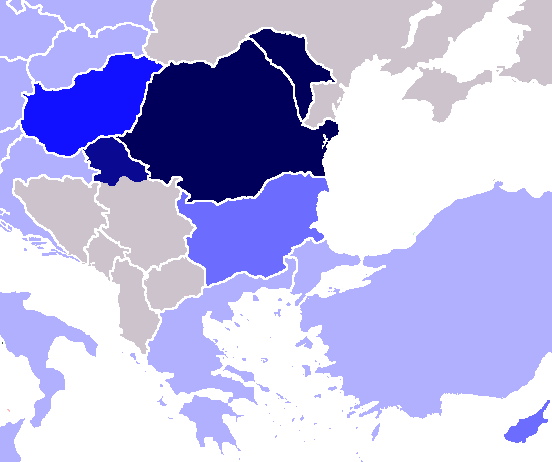

Romanian (obsolete spelling: Roumanian; , or , ) is the official and main language of

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

and

Moldova

Moldova, officially the Republic of Moldova, is a Landlocked country, landlocked country in Eastern Europe, with an area of and population of 2.42 million. Moldova is bordered by Romania to the west and Ukraine to the north, east, and south. ...

. Romanian is part of the

Eastern Romance sub-branch of

Romance languages

The Romance languages, also known as the Latin or Neo-Latin languages, are the languages that are Language family, directly descended from Vulgar Latin. They are the only extant subgroup of the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-E ...

, a linguistic group that evolved from several dialects of

Vulgar Latin

Vulgar Latin, also known as Colloquial, Popular, Spoken or Vernacular Latin, is the range of non-formal Register (sociolinguistics), registers of Latin spoken from the Crisis of the Roman Republic, Late Roman Republic onward. ''Vulgar Latin'' a ...

which separated from the

Western Romance languages in the course of the period from the 5th to the 8th centuries. To distinguish it within the Eastern Romance languages, in comparative linguistics it is called ''

Daco-Romanian'' as opposed to its closest relatives,

Aromanian,

Megleno-Romanian, and

Istro-Romanian. It is also spoken as a

minority language

A minority language is a language spoken by a minority of the population of a territory. Such people are termed linguistic minorities or language minorities. With a total number of 196 sovereign states recognized internationally (as of 2019) and ...

by stable communities in the countries surrounding Romania (

Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

,

Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

,

Serbia

, image_flag = Flag of Serbia.svg

, national_motto =

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Serbia.svg

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map =

, map_caption = Location of Serbia (gree ...

and

Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

), and by the large

Romanian diaspora

The Romanian diaspora is the Romanians, ethnically Romanian population outside Romania and Moldova. The concept does not usually include the ethnic Romanians who live as natives in nearby states, chiefly those Romanians who live in Ukraine, Hun ...

. In total, it is spoken by 25 million people as a

first language

A first language (L1), native language, native tongue, or mother tongue is the first language a person has been exposed to from birth or within the critical period hypothesis, critical period. In some countries, the term ''native language'' ...

.

[

Romanian was also known as '' Moldovan'' in Moldova, although the ]Constitutional Court of Moldova

The Constitutional Court of the Republic of Moldova () represents the sole body of constitutional jurisdiction in the Moldova, Republic of Moldova, autonomous and independent from the executive, the legislature and the judiciary.

The task of the ...

ruled in 2013 that "the official language of Moldova is Romanian". On 16 March 2023, the Moldovan Parliament

The parliament of the Republic of Moldova () is the supreme representative body of the Republic of Moldova, the only state legislative authority, being a unicameral structure composed of 101 elected MPs on lists, for a period or legislature of ...

approved a law on referring to the national language as Romanian in all legislative texts and the constitution. On 22 March, the president of Moldova, Maia Sandu, promulgated the law.

Overview

The history of the Romanian language started in the Roman province

The Roman provinces (, pl. ) were the administrative regions of Ancient Rome outside Roman Italy that were controlled by the Romans under the Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire. Each province was ruled by a Roman appointed as Roman g ...

s north of the Jireček Line in Classical antiquity

Classical antiquity, also known as the classical era, classical period, classical age, or simply antiquity, is the period of cultural History of Europe, European history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD comprising the inter ...

but there are 3 main hypotheses about its exact territory: the autochthony thesis (it developed in left-Danube Dacia only), the discontinuation thesis (it developed in right-Danube provinces only), and the "as-well-as" thesis that supports the language development on both sides of the Danube. Between the 6th and 8th century, following the accumulated tendencies inherited from the vernacular spoken in this large area and, to a much smaller degree, the influences from native dialects, and in the context of a lessened power of the Roman central authority the language evolved into Common Romanian

Common Romanian (), also known as Ancient Romanian (), or Proto-Romanian (), is a comparatively reconstructed Romance language evolved from Vulgar Latin and spoken by the ancestors of today's Romanians, Aromanians, Megleno-Romanians, Istro-Roma ...

. This proto-language

In the tree model of historical linguistics, a proto-language is a postulated ancestral language from which a number of attested languages are believed to have descended by evolution, forming a language family. Proto-languages are usually unatte ...

then came into close contact with the Slavic languages

The Slavic languages, also known as the Slavonic languages, are Indo-European languages spoken primarily by the Slavs, Slavic peoples and their descendants. They are thought to descend from a proto-language called Proto-Slavic language, Proto- ...

and subsequently divided into Aromanian, Megleno-Romanian, Istro-Romanian, and Daco-Romanian. Due to limited attestation between the 6th and 16th century, entire stages from its history are re-constructed by researchers, often with proposed relative chronologies and loose limits.

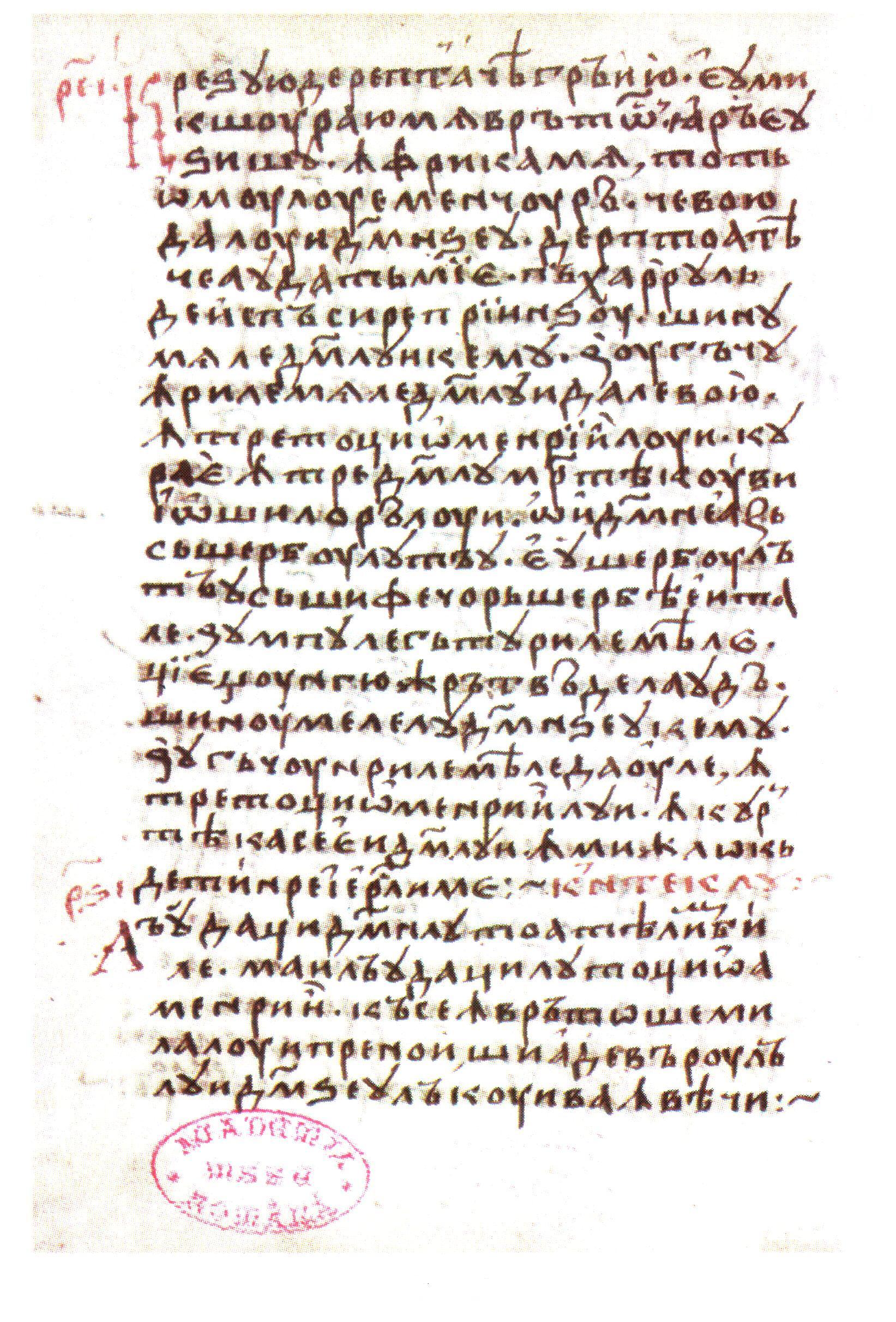

From the 12th or 13th century, official documents and religious texts were written in Old Church Slavonic

Old Church Slavonic or Old Slavonic ( ) is the first Slavic languages, Slavic literary language and the oldest extant written Slavonic language attested in literary sources. It belongs to the South Slavic languages, South Slavic subgroup of the ...

, a language that had a similar role to Medieval Latin

Medieval Latin was the form of Literary Latin used in Roman Catholic Church, Roman Catholic Western Europe during the Middle Ages. It was also the administrative language in the former Western Roman Empire, Roman Provinces of Mauretania, Numidi ...

in Western Europe. The oldest dated text in Romanian is a letter written in 1521 with Cyrillic letters

The Cyrillic script ( ) is a writing system used for various languages across Eurasia. It is the designated national script in various Slavic, Turkic, Mongolic, Uralic, Caucasian and Iranic-speaking countries in Southeastern Europe, Easte ...

, and until late 18th century, including during the development of printing, the same alphabet was used. The period after 1780, starting with the writing of its first grammar books, represents the modern age of the language, during which time the Latin alphabet

The Latin alphabet, also known as the Roman alphabet, is the collection of letters originally used by the Ancient Rome, ancient Romans to write the Latin language. Largely unaltered except several letters splitting—i.e. from , and from � ...

became official, the literary language was standardized, and a large number of words from Modern Latin and other Romance languages

The Romance languages, also known as the Latin or Neo-Latin languages, are the languages that are Language family, directly descended from Vulgar Latin. They are the only extant subgroup of the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-E ...

entered the lexis.

In the process of language evolution from fewer than 2500 attested words from Late Antiquity

Late antiquity marks the period that comes after the end of classical antiquity and stretches into the onset of the Early Middle Ages. Late antiquity as a period was popularized by Peter Brown (historian), Peter Brown in 1971, and this periodiza ...

to a lexicon

A lexicon (plural: lexicons, rarely lexica) is the vocabulary of a language or branch of knowledge (such as nautical or medical). In linguistics, a lexicon is a language's inventory of lexemes. The word ''lexicon'' derives from Greek word () ...

of over 150,000 words in its contemporary form, Romanian showed a high degree of lexical permeability, reflecting contact with Thraco-Dacian, Slavic languages

The Slavic languages, also known as the Slavonic languages, are Indo-European languages spoken primarily by the Slavs, Slavic peoples and their descendants. They are thought to descend from a proto-language called Proto-Slavic language, Proto- ...

(including Old Slavic, Serbian, Bulgarian, Ukrainian, and Russian), Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

, Hungarian, German, Turkish, and to languages that served as cultural models during and after the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a Europe, European Intellect, intellectual and Philosophy, philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained th ...

, in particular French. This lexical permeability is continuing today with the introduction of English words.[Pană Dindelegan, Gabriela]

''The Grammar of Romanian''

Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2013, ISBN 978-0-19-964492-6, page 5

Yet while the overall lexis was enriched with foreign words and internal constructs, in accordance with the history and development of the society and the diversification in semantic fields, the fundamental lexicon—the core vocabulary

A vocabulary (also known as a lexicon) is a set of words, typically the set in a language or the set known to an individual. The word ''vocabulary'' originated from the Latin , meaning "a word, name". It forms an essential component of languag ...

used in everyday conversation—remains governed by inherited elements from the Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

spoken in the Roman provinces bordering Danube

The Danube ( ; see also #Names and etymology, other names) is the List of rivers of Europe#Longest rivers, second-longest river in Europe, after the Volga in Russia. It flows through Central and Southeastern Europe, from the Black Forest sou ...

, without which no coherent sentence can be made.

History

Common Romanian

Romanian descended from the Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

spoken in the Roman province

The Roman provinces (, pl. ) were the administrative regions of Ancient Rome outside Roman Italy that were controlled by the Romans under the Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire. Each province was ruled by a Roman appointed as Roman g ...

s of Southeastern Europe

Southeast Europe or Southeastern Europe is a geographical sub-region of Europe, consisting primarily of the region of the Balkans, as well as adjacent regions and Archipelago, archipelagos. There are overlapping and conflicting definitions of t ...

north of the Jireček Line (a hypothetical boundary between the dominance of Latin and Greek influences).

Most scholars agree that two major dialects had developed from Common Romanian by the 10th century. Daco-Romanian (the official language of Romania and Moldova) and Istro-Romanian (a language spoken today by no more than 2,000 people in Istria

Istria ( ; Croatian language, Croatian and Slovene language, Slovene: ; Italian language, Italian and Venetian language, Venetian: ; ; Istro-Romanian language, Istro-Romanian: ; ; ) is the largest peninsula within the Adriatic Sea. Located at th ...

) descended from the northern dialect. Two other languages, Aromanian and Megleno-Romanian, developed from the southern version of Common Romanian. These two languages are now spoken in lands to the south of the Jireček Line.

Of the features that individualize Common Romanian, inherited from Latin or subsequently developed, of particular importance are:[Pană Dindelegan, Gabriela]

''The Grammar of Romanian''

Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2013, ISBN 978-0-19-964492-6, page 4

* appearance of schwa (written as ''ă'' in Romanian) vowel;

* growth of the plural inflectional ending -uri for the neuter gender;

* analytic present conditional (ex: Daco-Romanian );

* analytic future with an auxiliary derived from Latin volo (ex: Aromanian );

* enclisis of the definite article (ex. Istro-Romanian – );

* nominal declension with two case forms in the singular feminine.

Old Romanian

The use of the denomination ''Romanian'' () for the language and use of the demonym ''Romanians'' () for speakers of this language predate the foundation of the modern Romanian state. Romanians always used the general term / or regional terms such as (or ), or to designate themselves. Both the name of or for the Romanian language and the self-designation are attested as early as the 16th century, by various foreign travelers into the Carpathian Romance-speaking space, as well as in other historical documents written in Romanian at that time such as (''The Chronicles of the land of Moldova'') by Grigore Ureche

Grigore Ureche (; 1590–1647) was a Moldavian chronicler who wrote on Moldavian history in his ''Letopisețul Țării Moldovei'' ('' Chronicles of the Land of Moldavia''), covering the period from 1359 to 1594.

Biography

Grigore Ureche was th ...

.

The few allusions to the use of Romanian in writing as well as common words, anthroponyms and toponyms preserved in the Old Church Slavonic religious writings and chancellery documents, attested prior to the 16th century, along with the analysis of graphemes show that the writing of Romanian with the Cyrillic alphabet started in the second half of the 15th century.Romanian Cyrillic alphabet

The Romanian Cyrillic alphabet is the Cyrillic alphabet that was used to write the Romanian language and Church Slavonic until the 1830s, when it began to be gradually replaced by a Latin-based Romanian alphabet.Cyrillic remained in occasion ...

, which was used until the late 19th century. The letter is the oldest testimony of Romanian epistolary style and uses a prevalent lexis of Latin origin.Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, officially the Orthodox Catholic Church, and also called the Greek Orthodox Church or simply the Orthodox Church, is List of Christian denominations by number of members, one of the three major doctrinal and ...

: Psalter ( Hurmuzaki Psalter, Scheian Psalter, Psalter of Voroneț) and Apostolos lectionary (Bratu's Codex, Codex of Voroneț). Their origins go back to the 15th century. The fact that they are bilingual writings or descend from bilingual writings shows that the initiative to translate them was prompted by the need to facilitate access to the Church Slavonic liturgical text.Common Romanian

Common Romanian (), also known as Ancient Romanian (), or Proto-Romanian (), is a comparatively reconstructed Romance language evolved from Vulgar Latin and spoken by the ancestors of today's Romanians, Aromanians, Megleno-Romanians, Istro-Roma ...

, in the Wallachian and south-east Transylvanian varieties, the presence of palatal sonorants /ʎ/ and /ɲ/, nowadays preserved only regionally in Banat

Banat ( , ; ; ; ) is a geographical and Historical regions of Central Europe, historical region located in the Pannonian Basin that straddles Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe. It is divided among three countries: the eastern part lie ...

and Oltenia

Oltenia (), also called Lesser Wallachia in antiquated versions – with the alternative Latin names , , and between 1718 and 1739 – is a historical province and geographical region of Romania in western Wallachia. It is situated between the Da ...

, and the beginning of devoicing of asyllabic after consonants.

Modern Romanian

The modern age of Romanian starts in 1780 with the printing in Vienna of a very important grammar book

The modern age of Romanian starts in 1780 with the printing in Vienna of a very important grammar bookLatin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

as the language of the text and presented the phonetical and grammatical features of Romanian in comparison to its ancestor. The Modern age of Romanian language can be further divided into three phases: pre-modern or modernizing between 1780 and 1830, modern phase between 1831 and 1880, and contemporary from 1880 onwards.

Pre-modern period

Beginning with the printing in 1780 of ''Elementa linguae daco-romanae sive valachicae'', the pre-modern phase was characterized by the publishing of school textbooks, appearance of first normative works in Romanian, numerous translations, and the beginning of a conscious stage of re-latinization of the language.

Modern period

Starting from 1831 and lasting until 1880 the modern phase is characterized by the development of literary styles: scientific, administrative, and belletristic. It quickly reached a high point with the printing of Dacia Literară, a journal founded by Mihail Kogălniceanu

Mihail Kogălniceanu (; also known as Mihail Cogâlniceanu, Michel de Kogalnitchan; September 6, 1817 – July 1, 1891) was a Romanian Liberalism, liberal statesman, lawyer, historian and publicist; he became Prime Minister of Romania on Octo ...

and representing a literary society, which together with other publications like and spread the ideas of Romantic nationalism

Romantic nationalism (also national romanticism, organic nationalism, identity nationalism) is the form of nationalism in which the state claims its political legitimacy as an organic consequence of the unity of those it governs. This includes ...

and later contributed to the formation of other societies that took part in the Revolutions of 1848

The revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the springtime of the peoples or the springtime of nations, were a series of revolutions throughout Europe over the course of more than one year, from 1848 to 1849. It remains the most widespre ...

. Their members and those that shared their views are collectively known in Romania as "of '48"(), a name that was extended to the literature and writers around this time such as Vasile Alecsandri, Grigore Alexandrescu, Nicolae Bălcescu, Timotei Cipariu.

Between 1830 and 1860 "transitional alphabets" were used, adding Latin letters to the Romanian Cyrillic alphabet

The Romanian Cyrillic alphabet is the Cyrillic alphabet that was used to write the Romanian language and Church Slavonic until the 1830s, when it began to be gradually replaced by a Latin-based Romanian alphabet.Cyrillic remained in occasion ...

. The Latin alphabet became official at different dates in Wallachia and Transylvania - 1860, and Moldova -1862.

Following the unification of Moldavia and Wallachia

The unification of Moldavia and Wallachia (), also known as the unification of the Romanian Principalities () or as the Little Union (), happened in 1859 following the election of Alexandru Ioan Cuza as prince of both the Principality of Moldavi ...

further studies on the language were made, culminating with the founding of on 1 April 1866 on the initiative of C. A. Rosetti, an academic society that had the purpose of standardizing the orthography, formalizing the grammar and (via a dictionary) vocabulary of the language, and promoting literary and scientific publications. This institution later became the Romanian Academy

The Romanian Academy ( ) is a cultural forum founded in Bucharest, Romania, in 1866. It covers the scientific, artistic and literary domains. The academy has 181 active members who are elected for life.

According to its bylaws, the academy's ma ...

.

Contemporary period

The third phase of the modern age of Romanian language, starting from 1880 and continuing to this day, is characterized by the prevalence of the supradialectal form of the language, standardized with the express contribution of the school system and Romanian Academy, bringing a close to the process of literary language modernization and development of literary styles.Mihai Eminescu

Mihai Eminescu (; born Mihail Eminovici; 15 January 1850 – 15 June 1889) was a Romanians, Romanian Romanticism, Romantic poet, novelist, and journalist from Moldavia, generally regarded as the most famous and influential Romanian poet. Emin ...

, Ion Luca Caragiale, Ion Creangă, Ioan Slavici.

The current orthography, with minor reforms to this day and using Latin letters, was fully implemented in 1881, regulated by the Romanian Academy on a fundamentally phonological principle, with few morpho-syntactic exceptions.

Modern history of Romanian in Bessarabia

The first Romanian grammar

Standard Romanian (i.e. the '' Daco-Romanian'' language within Eastern Romance) shares largely the same grammar and most of the vocabulary and phonological processes with the other three surviving varieties of Eastern Romance, namely Aromanian, ...

was published in Vienna in 1780.

Historical grammar

Romanian has preserved a part of the Latin declension

In linguistics, declension (verb: ''to decline'') is the changing of the form of a word, generally to express its syntactic function in the sentence by way of an inflection. Declension may apply to nouns, pronouns, adjectives, adverbs, and det ...

. However, while Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

had six cases, from a morphological viewpoint, Romanian has only three: the nominative

In grammar, the nominative case ( abbreviated ), subjective case, straight case, or upright case is one of the grammatical cases of a noun or other part of speech, which generally marks the subject of a verb, or (in Latin and formal variants of E ...

/accusative

In grammar, the accusative case (abbreviated ) of a noun is the grammatical case used to receive the direct object of a transitive verb.

In the English language, the only words that occur in the accusative case are pronouns: "me", "him", "her", " ...

, genitive

In grammar, the genitive case ( abbreviated ) is the grammatical case that marks a word, usually a noun, as modifying another word, also usually a noun—thus indicating an attributive relationship of one noun to the other noun. A genitive can ...

/ dative, and marginally the vocative. Romanian nouns also preserve the neuter gender

Gender is the range of social, psychological, cultural, and behavioral aspects of being a man (or boy), woman (or girl), or third gender. Although gender often corresponds to sex, a transgender person may identify with a gender other tha ...

, although instead of functioning as a separate gender with its own forms in adjectives, the Romanian neuter became a mixture of masculine and feminine. The verb

A verb is a word that generally conveys an action (''bring'', ''read'', ''walk'', ''run'', ''learn''), an occurrence (''happen'', ''become''), or a state of being (''be'', ''exist'', ''stand''). In the usual description of English, the basic f ...

morphology of Romanian has shown the same move towards a compound perfect and future tense

In grammar, a future tense ( abbreviated ) is a verb form that generally marks the event described by the verb as not having happened yet, but expected to happen in the future. An example of a future tense form is the French ''achètera'', mea ...

as the other Romance languages. Compared with the other Romance languages

The Romance languages, also known as the Latin or Neo-Latin languages, are the languages that are Language family, directly descended from Vulgar Latin. They are the only extant subgroup of the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-E ...

, during its evolution, Romanian simplified the original Latin tense system.

Geographic distribution

Romanian is spoken mostly in Central, South-Eastern, and Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural and socio-economic connotations. Its eastern boundary is marked by the Ural Mountain ...

, although speakers of the language can be found all over the world, mostly due to emigration of Romanian nationals and the return of immigrants to Romania back to their original countries. Romanian speakers account for 0.5% of the world's population, and 4% of the Romance-speaking population of the world.

Romanian is the single official and national language in Romania and Moldova, although it shares the official status at regional level with other languages in the Moldovan autonomies of Gagauzia

Gagauzia () or Gagauz-Yeri, officially the Autonomous Territorial Unit of Gagauzia (ATUG), is an Administrative divisions of Moldova, autonomous territorial unit of Moldova. Its autonomy is intended for the local Gagauz people, a Turkic languages ...

and Transnistria

Transnistria, officially known as the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic and locally as Pridnestrovie, is a Landlocked country, landlocked Transnistria conflict#International recognition of Transnistria, breakaway state internationally recogn ...

. Romanian is also an official language of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina in Serbia along with five other languages. Romanian minorities are encountered in Serbia ( Timok Valley), Ukraine (Chernivtsi

Chernivtsi (, ; , ;, , see also #Names, other names) is a city in southwestern Ukraine on the upper course of the Prut River. Formerly the capital of the historic region of Bukovina, which is now divided between Romania and Ukraine, Chernivt ...

and Odesa

Odesa, also spelled Odessa, is the third most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city and List of hromadas of Ukraine, municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern ...

oblast

An oblast ( or ) is a type of administrative division in Bulgaria and several post-Soviet states, including Belarus, Russia and Ukraine. Historically, it was used in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union. The term ''oblast'' is often translated i ...

s), and Hungary ( Gyula). Large immigrant communities are found in Italy, Spain, France, and Portugal.

In 1995, the largest Romanian-speaking community in the Middle East was found in Israel, where Romanian was spoken by 5% of the population. Romanian is also spoken as a second language by people from Arabic-speaking countries who have studied in Romania. It is estimated that almost half a million Middle Eastern Arabs studied in Romania during the 1980s. Small Romanian-speaking communities are to be found in Kazakhstan and Russia. Romanian is also spoken within communities of Romanian and Moldovan immigrants in the United States, Canada and Australia, although they do not make up a large homogeneous community statewide.

Legal status

In Romania

According to the Constitution of Romania of 1991, as revised in 2003, Romanian is the official language of the Republic.

Romania mandates the use of Romanian in official government publications, public education and legal contracts. Advertisements as well as other public messages must bear a translation of foreign words, while trade signs and logos shall be written predominantly in Romanian.

The Romanian Language Institute (Institutul Limbii Române), established by the Ministry of Education of Romania, promotes Romanian and supports people willing to study the language, working together with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs' Department for Romanians Abroad.

Since 2013, the Romanian Language Day is celebrated on every 31 August.

In Moldova

Romanian is the official language of the Republic of Moldova. The 1991 Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the territory of another state or failed state, or are breaka ...

named the official language Romanian, and the Constitution of Moldova

The current Constitution was adopted on 29 July 1994 by the Moldovan Parliament and represents the supreme law of Moldova. It came into force on 27 August 1994 and has since been amended 10 times.

The Constitution established the Republic of ...

as originally adopted in 1994 named the state language of the country Moldovan. In December 2013, a decision of the Constitutional Court of Moldova

The Constitutional Court of the Republic of Moldova () represents the sole body of constitutional jurisdiction in the Moldova, Republic of Moldova, autonomous and independent from the executive, the legislature and the judiciary.

The task of the ...

ruled that the Declaration of Independence took precedence over the Constitution and the state language should be called Romanian. In 2023, the Moldovan parliament passed a law officially adopting the designation "Romanian" in all legal instruments, implementing the 2013 court decision.

Scholars agree that Moldovan and Romanian are the same language, with the glottonym "Moldovan" used in certain political contexts. It has been the sole official language since the adoption of the Law on State Language of the Moldavian SSR

The Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic or Moldavian SSR (, mo-Cyrl, Република Советикэ Сочиалистэ Молдовеняскэ), also known as the Moldovan Soviet Socialist Republic, Moldovan SSR, Soviet Moldavia, Sovie ...

in 1989. This law mandates the use of Moldovan in all the political, economic, cultural and social spheres, as well as asserting the existence of a "linguistic Moldo-Romanian identity". It is also used in schools, mass media, education and in the colloquial speech and writing. Outside the political arena the language is most often called "Romanian". In the breakaway territory of Transnistria, it is co-official with Ukrainian and Russian.

In the 2014 census, out of the 2,804,801 people living in Moldova, 24% (652,394) stated Romanian as their most common language, whereas 56% stated Moldovan. While in the urban centers speakers are split evenly between the two names (with the capital Chișinău

Chișinău ( , , ; formerly known as Kishinev) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Moldova, largest city of Moldova. The city is Moldova's main industrial and commercial centre, and is located in the middle of the coun ...

showing a strong preference for the name "Romanian", i.e. 3:2), in the countryside hardly a quarter of Romanian/Moldovan speakers indicated Romanian as their native language. Unofficial results of this census first showed a stronger preference for the name Romanian, however the initial reports were later dismissed by the Institute for Statistics, which led to speculations in the media regarding the forgery of the census results.

In Serbia

= Vojvodina

=

The Constitution of the Republic of Serbia determines that in the regions of the Republic of Serbia inhabited by national minorities, their own languages and scripts shall be officially used as well, in the manner established by law.

The Statute of the Autonomous Province of

The Constitution of the Republic of Serbia determines that in the regions of the Republic of Serbia inhabited by national minorities, their own languages and scripts shall be officially used as well, in the manner established by law.

The Statute of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina

Vojvodina ( ; sr-Cyrl, Војводина, ), officially the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina, is an Autonomous administrative division, autonomous province that occupies the northernmost part of Serbia, located in Central Europe. It lies withi ...

determines that, together with the Serbian language

Serbian (, ) is the standard language, standardized Variety (linguistics)#Standard varieties, variety of the Serbo-Croatian language mainly used by Serbs. It is the official and national language of Serbia, one of the three official languages of ...

and the Cyrillic script, and the Latin script as stipulated by the law, the Croat

The Croats (; , ) are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and other neighboring countries in Central Europe, Central and Southeastern Europe who share a common Croatian Cultural heritage, ancest ...

, Hungarian, Slovak, Romanian and Rusyn language

Rusyn ( ; ; )http://theses.gla.ac.uk/2781/1/2011BaptieMPhil-1.pdf , p. 8. is an East Slavic language spoken by Rusyns in parts of Central and Eastern Europe, and written in the Cyrillic script. The majority of speakers live in Carpathian Rut ...

s and their scripts, as well as languages and scripts of other nationalities, shall simultaneously be officially used in the work of the bodies of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina, in the manner established by the law. The bodies of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina are: the Assembly, the Executive Council and the provincial administrative bodies.

The Romanian language and script are officially used in eight municipalities: Alibunar

Alibunar (; German language, German: ''Alisbrunn''; ; ) is a town and municipality located in the South Banat District of the autonomous province of Vojvodina, Serbia. Alibunar town and Alibunar municipality have a population of 2,694 and 17,139 r ...

, Bela Crkva (''Biserica Albă''), Žitište

Žitište ( sr-Cyrl, Житиште, ; ; ) is a town and municipality located in the Central Banat District of the autonomous province of Vojvodina, Serbia. As of 2022 census, the town itself has a population of 2,550, while Žitište municipali ...

(''Sângeorgiu de Bega''), Zrenjanin

Zrenjanin ( sr-Cyrl, Зрењанин, ; ; ; ; ) is a List of cities in Serbia, city and the administrative center of the Central Banat District in the autonomous province of Vojvodina, Serbia. The city urban area has a population of 67,129 inh ...

(''Becicherecu Mare''), Kovačica (''Covăcița''), Kovin

Kovin (, ) is a town and municipality located in the South Banat District of the autonomous province of Vojvodina, Serbia. The town has a population of 11,623, while the municipality has 28,141 inhabitants (2022 census).

Other names

In Rom ...

(''Cuvin''), Plandište (''Plandiște'') and Sečanj

Sečanj (, ) is a town located in the Central Banat District of the autonomous province of Vojvodina, Serbia. As of 2022 census, the town itself had a population of 1,889, while the Sečanj municipality has 10,544 inhabitants.

Name

"Sečanj" is a ...

(''Seceani''). In the municipality of Vršac

Vršac ( sr-Cyrl, Вршац, ) is a city in the autonomous province of Vojvodina, Serbia. As of 2022, the city urban area had a population of 31,946, while the city administrative area had 45,462 inhabitants. It is located in the geographical ...

(''Vârșeț''), Romanian is official only in the villages of Vojvodinci (''Voivodinț''), Markovac (''Marcovăț''), Straža (''Straja''), Mali Žam (''Jamu Mic''), Malo Središte (''Srediștea Mică''), Mesić (''Mesici''), Jablanka (''Iablanca''), Sočica (''Sălcița''), Ritiševo (''Râtișor''), Orešac (''Oreșaț'') and Kuštilj (''Coștei'').

In the 2002 Census, the last carried out in Serbia, 1.5% of Vojvodinians stated Romanian as their native language.

= Timok Valley

=

The Vlachs of Serbia

The Vlachs (; / ) are a Romanian language, Romanian-speaking population group living in eastern Serbia, mainly within the Timok Valley. They are characterized by a culture that has preserved archaic and ancient elements in matters such as lang ...

are considered to speak Romanian as well.

Regional language status in Ukraine

In parts of Ukraine where Romanians

Romanians (, ; dated Endonym and exonym, exonym ''Vlachs'') are a Romance languages, Romance-speaking ethnic group and nation native to Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. Sharing a Culture of Romania, ...

constitute a significant share of the local population (districts in Chernivtsi

Chernivtsi (, ; , ;, , see also #Names, other names) is a city in southwestern Ukraine on the upper course of the Prut River. Formerly the capital of the historic region of Bukovina, which is now divided between Romania and Ukraine, Chernivt ...

, Odesa

Odesa, also spelled Odessa, is the third most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city and List of hromadas of Ukraine, municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern ...

and Zakarpattia oblast

An oblast ( or ) is a type of administrative division in Bulgaria and several post-Soviet states, including Belarus, Russia and Ukraine. Historically, it was used in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union. The term ''oblast'' is often translated i ...

s) Romanian is taught in schools as a primary language and there are Romanian-language newspapers, TV, and radio broadcasting.

The University of Chernivtsi in western Ukraine trains teachers for Romanian schools in the fields of Romanian philology, mathematics and physics.

In Hertsa Raion of Ukraine as well as in other villages of Chernivtsi Oblast

Chernivtsi Oblast (), also referred to as Chernivechchyna (), is an oblast (province) in western Ukraine, consisting of the northern parts of the historical regions of Bukovina and Bessarabia. It has an international border with Romania and Moldo ...

and Zakarpattia Oblast

Zakarpattia Oblast (Ukrainian language, Ukrainian: Закарпатська область), also referred to as simply Zakarpattia (Ukrainian language, Ukrainian: Закарпаття; Hungarian language, Hungarian: ''Kárpátalja'') or Transcar ...

, Romanian has been declared a "regional language" alongside Ukrainian as per the 2012 legislation on languages in Ukraine.

In other countries and organizations

Romanian is an official or administrative language in various communities and organisations, such as the Latin Union and the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are Geography of the European Union, located primarily in Europe. The u ...

. Romanian is also one of the five languages in which religious services are performed in the autonomous monastic state of Mount Athos

Mount Athos (; ) is a mountain on the Athos peninsula in northeastern Greece directly on the Aegean Sea. It is an important center of Eastern Orthodoxy, Eastern Orthodox monasticism.

The mountain and most of the Athos peninsula are governed ...

, spoken in the monastic communities of Prodromos and Lakkoskiti. In the unrecognised state of Transnistria

Transnistria, officially known as the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic and locally as Pridnestrovie, is a Landlocked country, landlocked Transnistria conflict#International recognition of Transnistria, breakaway state internationally recogn ...

, Moldovan is one of the official languages. However, unlike all other dialects of Romanian, this variety of Moldovan is written in Cyrillic script.

As a second and foreign language

Romanian is taught in some areas that have Romanian minority communities, such as Vojvodina

Vojvodina ( ; sr-Cyrl, Војводина, ), officially the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina, is an Autonomous administrative division, autonomous province that occupies the northernmost part of Serbia, located in Central Europe. It lies withi ...

in Serbia, Bulgaria, Ukraine and Hungary. The Romanian Cultural Institute (ICR) has since 1992 organised summer courses in Romanian for language teachers. There are also non-Romanians who study Romanian as a foreign language, for example the Nicolae Bălcescu High-school in Gyula, Hungary.

Romanian is taught as a foreign language

A foreign language is a language that is not an official language of, nor typically spoken in, a specific country. Native speakers from that country usually need to acquire it through conscious learning, such as through language lessons at schoo ...

in tertiary institutions, mostly in European countries such as Germany, France and Italy, and the Netherlands, as well as in the United States. Overall, it is taught as a foreign language in 43 countries around the world.

Popular culture

Romanian has become popular in other countries through movies and songs performed in the Romanian language. Examples of Romanian acts that had a great success in non-Romanophone countries are the bands O-Zone (with their No. 1 single Dragostea Din Tei, also known as '' Numa Numa,'' across the world in 2003–2004), Akcent (popular in the Netherlands, Poland and other European countries), Activ (successful in some Eastern European countries), DJ Project (popular as clubbing music) SunStroke Project (known by viral video " Epic Sax Guy") and Alexandra Stan (worldwide no.1 hit with " Mr. Saxobeat") and Inna as well as high-rated movies like '' 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days'', '' The Death of Mr. Lazarescu'', '' 12:08 East of Bucharest'' or '' California Dreamin''' (all of them with awards at the Cannes Film Festival

The Cannes Film Festival (; ), until 2003 called the International Film Festival ('), is the most prestigious film festival in the world.

Held in Cannes, France, it previews new films of all genres, including documentaries, from all around ...

).

Also some artists wrote songs dedicated to the Romanian language. The multi-platinum pop trio O-Zone (originally from Moldova) released a song called ("I won't forsake our language"). The final verse of this song, , is translated in English as "I won't forsake our language, our Romanian language". Also, the Moldovan musicians Doina and Ion Aldea Teodorovici performed a song called "The Romanian language".

Dialects

Romanian is also called Daco-Romanian in comparative linguistics to distinguish from the other dialects of Common Romanian

Common Romanian (), also known as Ancient Romanian (), or Proto-Romanian (), is a comparatively reconstructed Romance language evolved from Vulgar Latin and spoken by the ancestors of today's Romanians, Aromanians, Megleno-Romanians, Istro-Roma ...

: Aromanian, Megleno-Romanian, and Istro-Romanian. The origin of the term "Daco-Romanian" can be traced back to the first printed book of Romanian grammar in 1780,Danube

The Danube ( ; see also #Names and etymology, other names) is the List of rivers of Europe#Longest rivers, second-longest river in Europe, after the Volga in Russia. It flows through Central and Southeastern Europe, from the Black Forest sou ...

is called to emphasize its origin and its area of use, which includes the former Roman province of Dacia

Dacia (, ; ) was the land inhabited by the Dacians, its core in Transylvania, stretching to the Danube in the south, the Black Sea in the east, and the Tisza in the west. The Carpathian Mountains were located in the middle of Dacia. It thus ro ...

, although it is spoken also south of the Danube, in Dobruja

Dobruja or Dobrudja (; or ''Dobrudža''; , or ; ; Dobrujan Tatar: ''Tomrîğa''; Ukrainian language, Ukrainian and ) is a Geography, geographical and historical region in Southeastern Europe that has been divided since the 19th century betw ...

, the Timok Valley and northern Bulgaria.

This article deals with the Romanian (i.e. Daco-Romanian) language, and thus only its dialectal variations are discussed here. The differences between the regional varieties are small, limited to regular phonetic changes, few grammar aspects, and lexical particularities. There is a single written and spoken standard (literary) Romanian language used by all speakers, regardless of region. Like most natural languages, Romanian dialects are part of a dialect continuum

A dialect continuum or dialect chain is a series of Variety (linguistics), language varieties spoken across some geographical area such that neighboring varieties are Mutual intelligibility, mutually intelligible, but the differences accumulat ...

. The dialects of Romanian are also referred to as 'sub-dialects' and are distinguished primarily by phonetic differences. Romanians themselves speak of the differences as 'accents' or 'speeches' (in Romanian: or ).

Depending on the criteria used for classifying these dialects, fewer or more are found, ranging from 2 to 20, although the most widespread approaches give a number of five dialects. These are grouped into two main types, southern and northern, further divided as follows:

* The southern type has only one member:

** the Wallachian dialect

The Wallachian dialect (''/'/'') is one of the several dialects of the Romanian language (Daco-Romanian). Its geographic distribution covers approximately the historical region of Wallachia, occupying the southern part of Romania, roughly between ...

, spoken in the southern part of Romania, in the historical regions of Muntenia

Muntenia (, also known in English as Greater Wallachia) is a historical region of Romania, part of Wallachia (also, sometimes considered Wallachia proper, as ''Muntenia'', ''Țara Românească'', and the rarely used ''Valahia'' are synonyms in Ro ...

, Oltenia

Oltenia (), also called Lesser Wallachia in antiquated versions – with the alternative Latin names , , and between 1718 and 1739 – is a historical province and geographical region of Romania in western Wallachia. It is situated between the Da ...

and the southern part of Northern Dobruja

Northern Dobruja ( or simply ; , ''Severna Dobrudzha'') is the part of Dobruja within the borders of Romania. It lies between the lower Danube, Danube River and the Black Sea, bordered in the south by Southern Dobruja, which is a part of Bulgaria.

...

, but also extending in the southern parts of Transylvania

Transylvania ( or ; ; or ; Transylvanian Saxon dialect, Transylvanian Saxon: ''Siweberjen'') is a List of historical regions of Central Europe, historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and ...

.

* The northern type consists of several dialects:

** the Moldavian dialect

The Moldavian dialect is one of several dialects of the Romanian language (Daco-Romanian). It is spoken across the approximate area of the historical region of Moldavia, now split between the Republic of Moldova, Romania, and Ukraine.

The deli ...

, spoken in the historical region of Moldavia

Moldavia (, or ; in Romanian Cyrillic alphabet, Romanian Cyrillic: or ) is a historical region and former principality in Eastern Europe, corresponding to the territory between the Eastern Carpathians and the Dniester River. An initially in ...

, now split among Romania, the Republic of Moldova, and Ukraine (Bukovina

Bukovina or ; ; ; ; , ; see also other languages. is a historical region at the crossroads of Central and Eastern Europe. It is located on the northern slopes of the central Eastern Carpathians and the adjoining plains, today divided betwe ...

and Bessarabia), as well as northern part of Northern Dobruja

Northern Dobruja ( or simply ; , ''Severna Dobrudzha'') is the part of Dobruja within the borders of Romania. It lies between the lower Danube, Danube River and the Black Sea, bordered in the south by Southern Dobruja, which is a part of Bulgaria.

...

;

** the Banat dialect, spoken in the historical region of Banat

Banat ( , ; ; ; ) is a geographical and Historical regions of Central Europe, historical region located in the Pannonian Basin that straddles Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe. It is divided among three countries: the eastern part lie ...

, including parts of Serbia;

** a group of finely divided and transition-like Transylvanian varieties, among which two are most often distinguished, those of Crișana

Crișana (, , ) is a geographical and historical region of Romania named after the Criș (Körös) River and its three tributaries: the Crișul Alb, Crișul Negru, and Crișul Repede. In Romania, the term is sometimes extended to include areas ...

and Maramureș.

Over the last century, however, regional accents have been weakened due to mass communication and greater mobility.

Some argot

A cant is the jargon or language of a group, often employed to exclude or mislead people outside the group.McArthur, T. (ed.) ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (1992) Oxford University Press It may also be called a cryptolect, argo ...

s and speech forms have also arisen from the Romanian language. Examples are the Gumuțeasca

Gumuțeasca or Gomuțeasca (sometimes referred to as ''limba gumuțească'', "Gumutseascan language", or ''limba de sticlă'', "the glass language") is an argot (a speech form spoken by a group of people to prevent outsiders from understanding th ...

, spoken in Mărgău

Mărgău (; ) is a commune in Cluj County, Transylvania, Romania. It is composed of six villages: Bociu (''Bocs''), Buteni (''Kalotabökény''), Ciuleni (''Incsel''), Mărgău, Răchițele (''Havasrekettye''), and Scrind-Frăsinet (''Kőrizstető' ...

, and the Totoiana, an inverted "version" of Romanian spoken in Totoi.

Classification

Romance language

Romanian is a Romance language, belonging to the Italic branch of the

Romanian is a Romance language, belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European language family

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the northern Indian subcontinent, most of Europe, and the Iranian plateau with additional native branches found in regions such as Sri Lanka, the Maldives, parts of Central Asia (e. ...

, having much in common with languages such as Italian, Spanish, French and Portuguese.[ Romanian has had a greater share of foreign influence than some other Romance languages such as Italian in terms of vocabulary and other aspects. A 1949 study by the Italian-American linguist Mario Pei, analyzing the degree to which seven Romance languages diverged from Vulgar Latin with respect to their accent vocalization, yielded the following measurements of divergence (with higher percentages indicating greater divergence from the stressed vowels of Vulgar Latin):

* Sardinian: 8%

* Italian: 12%

* Spanish: 20%

* Romanian: 23.5%

* Occitan: 25%

* Portuguese: 31%

* French: 44%

The study emphasized, however, that it represented only "a very elementary, incomplete and tentative demonstration" of how statistical methods could measure linguistic change, assigned "frankly arbitrary" point values to various types of change, and did not compare languages in the sample with respect to any characteristics or forms of divergence other than stressed vowels, among other caveats.

The ]lexical similarity

In linguistics, lexical similarity is a measure of the degree to which the word sets of two given languages are similar. A lexical similarity of 1 (or 100%) would mean a total overlap between vocabularies, whereas 0 means there are no common words. ...

of Romanian with Italian has been estimated at 77%, followed by French at 75%, Sardinian 74%, Catalan 73%, Portuguese and Rhaeto-Romance 72%, Spanish 71%.

The Romanian vocabulary became predominantly influenced by French and, to a lesser extent, Italian in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Balkan language area

While most of Romanian grammar and morphology are based on Latin, there are some features that are shared only with other languages of the Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

and not found in other Romance languages. The shared features of Romanian and the other languages of the Balkan language area ( Bulgarian, Macedonian, Albanian, Greek, and Serbo-Croatian

Serbo-Croatian ( / ), also known as Bosnian-Croatian-Montenegrin-Serbian (BCMS), is a South Slavic language and the primary language of Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Montenegro. It is a pluricentric language with four mutually i ...

) include a suffixed definite article

In grammar, an article is any member of a class of dedicated words that are used with noun phrases to mark the identifiability of the referents of the noun phrases. The category of articles constitutes a part of speech.

In English, both "the" ...

, the syncretism

Syncretism () is the practice of combining different beliefs and various school of thought, schools of thought. Syncretism involves the merging or religious assimilation, assimilation of several originally discrete traditions, especially in the ...

of genitive and dative case and the formation of the future and the alternation of infinitive with subjunctive constructions. According to a well-established scholarly theory, most Balkanisms could be traced back to the development of the Balkan Romance languages; these features were adopted by other languages due to language shift

Language shift, also known as language transfer, language replacement or language assimilation, is the process whereby a speech community shifts to a different language, usually over an extended period of time. Often, languages that are perceived ...

.

Slavic influence

Slavic influence on Romanian is especially noticeable in its vocabulary, with words of Slavic origin constituting about 10–15% of modern Romanian lexicon,Old Church Slavonic

Old Church Slavonic or Old Slavonic ( ) is the first Slavic languages, Slavic literary language and the oldest extant written Slavonic language attested in literary sources. It belongs to the South Slavic languages, South Slavic subgroup of the ...

,Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia (; ; : , : ) is a historical and geographical region of modern-day Romania. It is situated north of the Lower Danube and south of the Southern Carpathians. Wallachia was traditionally divided into two sections, Munteni ...

and Moldavia

Moldavia (, or ; in Romanian Cyrillic alphabet, Romanian Cyrillic: or ) is a historical region and former principality in Eastern Europe, corresponding to the territory between the Eastern Carpathians and the Dniester River. An initially in ...

from the 14th to the 18th century (although not understood by most people), as well as the liturgical language of the Romanian Orthodox Church

The Romanian Orthodox Church (ROC; , ), or Romanian Patriarchate, is an autocephalous Eastern Orthodox church in full communion with other Eastern Orthodox Christian denomination, Christian churches, and one of the nine patriarchates in the East ...

.Origin of the Romanians

Several theories, in great extent mutually exclusive, address the issue of the origin of the Romanians. The Romanian language descends from the Vulgar Latin dialects spoken in the Roman provinces north of the "Jireček Line" (a proposed notion ...

).phoneme

A phoneme () is any set of similar Phone (phonetics), speech sounds that are perceptually regarded by the speakers of a language as a single basic sound—a smallest possible Phonetics, phonetic unit—that helps distinguish one word fr ...

.

Other influences

Even before the 19th century, Romanian came in contact with several other languages. Notable examples of lexical borrowings include:

* German: ''cartof'' < ''Kartoffel'' "potato", ''bere'' < ''Bier'' "beer", ''șurub'' < ''Schraube'' "screw", ''turn'' < ''Turm'' "tower", ''ramă'' < ''Rahmen'' "frame", ''muștiuc'' < ''Mundstück'' "mouth piece", ''bormașină'' < ''Bohrmaschine'' "drilling machine", ''cremșnit'' < ''Kremschnitte'' "cream slice", ''șvaițer'' < ''Schweizer'' "Swiss cheese", ''șlep'' < ''Schleppkahn'' "barge", ''șpriț'' < ''Spritzer'' "wine with soda water", ''abțibild'' < ''Abziehbild'' "decal picture", ''șnițel'' < ''(Wiener) Schnitzel'' "a battered cutlet", ''șmecher'' < ''Schmecker'' "taster (not interested in buying)",'' șuncă'' < dialectal ''Schunke'' (''Schinken'') "ham", ''punct'' < ''Punkt'' "point", ''maistru'' < ''Meister'' "master", ''rundă'' < ''Runde'' "round".

Furthermore, during the Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

and, later on, Austrian rule of Banat

Banat ( , ; ; ; ) is a geographical and Historical regions of Central Europe, historical region located in the Pannonian Basin that straddles Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe. It is divided among three countries: the eastern part lie ...

, Transylvania

Transylvania ( or ; ; or ; Transylvanian Saxon dialect, Transylvanian Saxon: ''Siweberjen'') is a List of historical regions of Central Europe, historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and ...

, and Bukovina

Bukovina or ; ; ; ; , ; see also other languages. is a historical region at the crossroads of Central and Eastern Europe. It is located on the northern slopes of the central Eastern Carpathians and the adjoining plains, today divided betwe ...

, a large number of words were borrowed from Austrian High German, in particular in fields such as the military, administration, social welfare, economy, etc.Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

: ''folos'' < ''ófelos'' "use", ''buzunar'' < ''buzunára'' "pocket", ''proaspăt'' < ''prósfatos'' "fresh", ''cutie'' < ''cution'' "box", ''portocale'' < ''portokalia'' "oranges". While Latin borrowed words of Greek origin, Romanian obtained Greek loanwords on its own. Greek entered Romanian through the '' apoikiai'' (colonies) and '' emporia'' (trade stations) founded in and around Dobruja

Dobruja or Dobrudja (; or ''Dobrudža''; , or ; ; Dobrujan Tatar: ''Tomrîğa''; Ukrainian language, Ukrainian and ) is a Geography, geographical and historical region in Southeastern Europe that has been divided since the 19th century betw ...

, through the presence of Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

in north of the Danube

The Danube ( ; see also #Names and etymology, other names) is the List of rivers of Europe#Longest rivers, second-longest river in Europe, after the Volga in Russia. It flows through Central and Southeastern Europe, from the Black Forest sou ...

, through Bulgarian during Bulgarian Empires that converted Romanians to Orthodox Christianity, and after the Greek Civil War, when thousands of Greeks fled Greece.

* Hungarian: ''a cheltui'' < ''költeni'' "to spend", ''a făgădui'' < ''fogadni'' "to promise", ''a mântui'' < ''menteni'' "to save", ''oraș'' < ''város'' "city";

* Turkish: ''papuc'' < ''pabuç'' "slipper", ''ciorbă'' < ''çorba'' "wholemeal soup, sour soup", ''bacșiș'' < ''bahşiş'' "tip" (ultimately from Persian '' baksheesh'');

* Additionally, the Romani language

Romani ( ; also Romanes , Romany, Roma; ) is an Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan macrolanguage of the Romani people. The largest of these are Vlax Romani language, Vlax Romani (about 500,000 speakers), Balkan Romani (600,000), and Sinte Roma ...

has provided a series of slang words to Romanian such as: ''mișto'' "good, beautiful, cool" < ''mišto'', ''gagică'' "girlie, girlfriend" < '' gadji'', ''a hali'' "to devour" < ''halo'', ''mandea'' "yours truly" < ''mande'', ''a mangli'' "to pilfer" < ''manglo''.

French, Italian, and English loanwords

Since the 19th century, many literary or learned words were borrowed from the other Romance languages, especially from French and Italian (for example: "desk, office", "airplane", "exploit"). It was estimated that about 38% of words in Romanian are of French and/or Italian origin (in many cases both languages); and adding this to Romanian's native stock, about 75%–85% of Romanian words can be traced to Latin. The use of these Romanianized French and Italian learned loans has tended to increase at the expense of previous loanwords, many of which have become rare or fallen out of use. As second or third languages, French and Italian themselves are better known in Romania than in Romania's neighbors. Along with the switch to the Latin alphabet in Moldova, the re-latinization of the vocabulary has tended to reinforce the Latin character of the language.

In the process of lexical modernization, much of the native Latin stock have acquired doublets from other Romance languages

The Romance languages, also known as the Latin or Neo-Latin languages, are the languages that are Language family, directly descended from Vulgar Latin. They are the only extant subgroup of the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-E ...

, thus forming a further and more modern and literary lexical layer. Typically, the native word is a noun and the learned loan is an adjective. Some examples of doublets:

In the 20th century, an increasing number of English words have been borrowed (such as: < jam; < interview; < match; < manager; < football; / < sandwich; < business; < cake; < WC; < tramway). These words are assigned grammatical gender in Romanian and handled according to Romanian rules; thus "the manager" is . Some borrowings, for example in the computer field, appear to have awkward (perhaps contrived and ludicrous) 'Romanisation,' such as which is the plural of the Internet term ''cookie''; normally, the hyphen isn't used for plural endings and definite articles.

In some cases, there are multiple variants of loanwords, such as / (masculine) and / (neuter).

Lexis

A 1988 statistic by Marius Sala is based on 2,581 words chosen on the criteria of frequency, semantic richness and productivity, which also contain words formed on the territory of the Romanian language. This statistic gives the percentages below:

A 1988 statistic by Marius Sala is based on 2,581 words chosen on the criteria of frequency, semantic richness and productivity, which also contain words formed on the territory of the Romanian language. This statistic gives the percentages below:Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

;

* 15.26% – academic loanwords from Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

;

* 22.12% – French loans;

* 9.18% – loans from Old Church Slavonic

Old Church Slavonic or Old Slavonic ( ) is the first Slavic languages, Slavic literary language and the oldest extant written Slavonic language attested in literary sources. It belongs to the South Slavic languages, South Slavic subgroup of the ...

;

* 3.95% – loans from Italian;

* 3.91% – words formed in Romanian;

* 2.71% – words of uncertain origin;

* 2.6% – loans from Bulgarian;

* 2.47% – loans from German (including Austrian High German);

* 1.7% – loans from Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

;

* 1.43% – loans from Hungarian;

* 1.12% – loans from Russian;

* 0.96% – words inherited from the Thraco-Dacian substratum;

* 0.85% – loans from Serbian;

* 0.73% – loans from Turkish

If the analysis is restricted to a core vocabulary of 2,500 frequent, semantically rich and productive words, then the Latin inheritance comes first, followed by Romance and classical Latin neologisms, whereas the Slavic borrowings come third.

Although they are rarely used nowadays, the Romanian calendar used to have the traditional Romanian month names, unique to the language.

The longest word in Romanian is , with 44 letters, but the longest one admitted by the '' Dicționarul explicativ al limbii române'' ("Explanatory Dictionary of the Romanian Language", DEX) is , with 25 letters.

Grammar

Romanian nouns are characterized by gender (feminine, masculine, and neuter), and declined by number (singular and plural) and case (nominative

In grammar, the nominative case ( abbreviated ), subjective case, straight case, or upright case is one of the grammatical cases of a noun or other part of speech, which generally marks the subject of a verb, or (in Latin and formal variants of E ...

/accusative

In grammar, the accusative case (abbreviated ) of a noun is the grammatical case used to receive the direct object of a transitive verb.

In the English language, the only words that occur in the accusative case are pronouns: "me", "him", "her", " ...

, dative/genitive

In grammar, the genitive case ( abbreviated ) is the grammatical case that marks a word, usually a noun, as modifying another word, also usually a noun—thus indicating an attributive relationship of one noun to the other noun. A genitive can ...

and vocative). The articles, as well as most adjectives and pronouns, agree in gender, number and case with the noun they modify.

Romanian is the only major Romance language where definite articles are enclitic: that is, attached to the end of the noun (as in the Scandinavian Languages

The North Germanic languages make up one of the three branches of the Germanic languages—a sub-family of the Indo-European languages—along with the West Germanic languages and the extinct East Germanic languages. The language group is al ...

, Bulgarian and Albanian), instead of in front ( proclitic). They were formed, as in other Romance languages, from the Latin demonstrative pronouns.

As in all Romance languages, Romanian verbs are highly inflected for person, number, tense, mood, and voice. The usual word order in sentences is subject–verb–object (SVO). Romanian has four verbal conjugations which further split into ten conjugation patterns. Romanian verbs are conjugated for five moods (indicative

A realis mood ( abbreviated ) is a grammatical mood which is used principally to indicate that something is a statement of fact; in other words, to express what the speaker considers to be a known state of affairs, as in declarative sentence

Dec ...

, conditional/ optative, imperative, subjunctive

The subjunctive (also known as the conjunctive in some languages) is a grammatical mood, a feature of an utterance that indicates the speaker's attitude toward it. Subjunctive forms of verbs are typically used to express various states of unrealit ...

, and presumptive) and four non-finite forms (infinitive

Infinitive ( abbreviated ) is a linguistics term for certain verb forms existing in many languages, most often used as non-finite verbs that do not show a tense. As with many linguistic concepts, there is not a single definition applicable to all ...

, gerund

In linguistics, a gerund ( abbreviated ger) is any of various nonfinite verb forms in various languages; most often, but not exclusively, it is one that functions as a noun. The name is derived from Late Latin ''gerundium,'' meaning "which is ...

, supine

In grammar, a supine is a form of verbal noun used in some languages. The term is most often used for Latin, where it is one of the four principal parts of a verb. The word refers to a position of lying on one's back (as opposed to ' prone', l ...

, and participle

In linguistics, a participle (; abbr. ) is a nonfinite verb form that has some of the characteristics and functions of both verbs and adjectives. More narrowly, ''participle'' has been defined as "a word derived from a verb and used as an adject ...

).

Phonology

Romanian has seven vowel

A vowel is a speech sound pronounced without any stricture in the vocal tract, forming the nucleus of a syllable. Vowels are one of the two principal classes of speech sounds, the other being the consonant. Vowels vary in quality, in loudness a ...

s: , , , , , and . Additionally, and may appear in some borrowed words. Arguably, the diphthongs and are also part of the phoneme set. There are twenty-two consonants. The two approximant

Approximants are speech sounds that involve the articulators approaching each other but not narrowly enough nor with enough articulatory precision to create turbulent airflow. Therefore, approximants fall between fricatives, which do prod ...

s and can appear before or after any vowel, creating a large number of glide-vowel sequences which are, strictly speaking, not diphthong

A diphthong ( ), also known as a gliding vowel or a vowel glide, is a combination of two adjacent vowel sounds within the same syllable. Technically, a diphthong is a vowel with two different targets: that is, the tongue (and/or other parts of ...

s.

In final positions after consonants, a short can be deleted, surfacing only as the palatalization of the preceding consonant (e.g., ). Similarly, a deleted may prompt labialization

Labialization is a secondary articulatory feature of sounds in some languages. Labialized sounds involve the lips while the remainder of the oral cavity produces another sound. The term is normally restricted to consonants. When vowels invol ...

of a preceding consonant, though this has ceased to carry any morphological meaning.

Phonetic changes

Owing to its isolation from the other Romance languages, the phonetic evolution of Romanian was quite different, but the language does share a few changes with Italian, such as → (Lat. clarus → Rom. chiàr, Ital. chiaro, Lat. clamare → Rom. chemare, Ital. chiamare) and → (Lat. *glacia (glacies) → Rom. ghéață, Ital. ghiaccia, ghiaccio, Lat. *ungla (ungula) → Rom. unghie, Ital. unghia), although this did not go as far as it did in Italian with other similar clusters (Rom. plàce, Ital. piace).

Another similarity with Italian is the change from or to or (Lat. pax, pacem → Rom. and Ital. pace, Lat. dulcem → Rom. dulce, Ital. dolce, Lat. circus → Rom. cerc, Ital. circo) and or to or (Lat. gelu → Rom. gèr, Ital. gelo, Lat. marginem → Rom. and Ital. margine, Lat. gemere → Rom. gèm (gemere), Ital. gemere).

There are also a few changes shared with Dalmatian, such as (probably phonetically ) → (Lat. cognatus → Rom. cumnat, Dalm. comnut) and → in some situations (Lat. coxa → Rom. cópsă, Dalm. copsa).

Among the notable phonetic changes are:

* diphthongization of e and o → ea and oa, before ă (or e as well, in the case of o) in the next syllable:

:* Lat. cera → Rom. céră (wax)

:* Lat. sole → Rom. sóre (sun)

* iotation → in the beginning of the word

:* Lat. herba → Rom. ĭarbă (grass, herb)

* velar → labial before alveolar consonants and (e.g. ngu → mb):

:* Lat. octo → Rom. opt (eight)

:* Lat. lingua → Rom. lìmbă (tongue, language)

:* Lat. signum → Rom. sèmn (sign)

:* Lat. coxa → Rom. cópsă (thigh)

:* Lat. aqua → Rom. apă (water)

* rhotacism → between vowels

:* Lat. caelum → Rom. cèr (sky)

* Alveolars assibilated to when before short or long

:* Lat. deus → Rom. ḑèŭ → zèŭ (god)

:* Lat. tenem → Rom. ține (hold)

Romanian has entirely lost Latin (qu), turning it either into (Lat. quattuor → Rom. ''pàtru'', "four"; cf. It. ''quattro'') or (Lat. quando → Rom. ''când'', "when"; Lat. quale → Rom. ''càre'', "which").

Writing system

The first written record about a

The first written record about a Romance language

The Romance languages, also known as the Latin or Neo-Latin languages, are the languages that are Language family, directly descended from Vulgar Latin. They are the only extant subgroup of the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-E ...

spoken in the Middle Ages in the Balkans is from 587. A Vlach muleteer accompanying the Byzantine army noticed that the load was falling from one of the animals and shouted to a companion ''Torna, torna, fratre!'' (meaning "Return, return, brother!"). Theophanes Confessor recorded it as part of a 6th-century military expedition by Comentiolus and Priscus against the Avars and Slovenes.

The oldest surviving written text in Romanian is a letter from late June 1521, in which Neacșu of Câmpulung wrote to the mayor of Brașov

Brașov (, , ; , also ''Brasau''; ; ; Transylvanian Saxon dialect, Transylvanian Saxon: ''Kruhnen'') is a city in Transylvania, Romania and the county seat (i.e. administrative centre) of Brașov County.

According to the 2021 Romanian census, ...

about an imminent attack of the Turks. It was written using the Cyrillic alphabet

The Cyrillic script ( ) is a writing system used for various languages across Eurasia. It is the designated national script in various Slavic, Turkic, Mongolic, Uralic, Caucasian and Iranic-speaking countries in Southeastern Europe, Easte ...

, like most early Romanian writings. The earliest surviving writing in Latin script was a late 16th-century Transylvania

Transylvania ( or ; ; or ; Transylvanian Saxon dialect, Transylvanian Saxon: ''Siweberjen'') is a List of historical regions of Central Europe, historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and ...

n text which was written with the Hungarian alphabet conventions.

In the 18th century, Transylvania

Transylvania ( or ; ; or ; Transylvanian Saxon dialect, Transylvanian Saxon: ''Siweberjen'') is a List of historical regions of Central Europe, historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and ...

n scholars noted the Latin origin of Romanian and adapted the Latin alphabet

The Latin alphabet, also known as the Roman alphabet, is the collection of letters originally used by the Ancient Rome, ancient Romans to write the Latin language. Largely unaltered except several letters splitting—i.e. from , and from � ...

to the Romanian language, using some orthographic rules from Italian, recognized as Romanian's closest relative. The Cyrillic alphabet remained in (gradually decreasing) use until 1860, when Romanian writing was first officially regulated.

In the Soviet Republic of Moldova, the Russian-derived Moldovan Cyrillic alphabet was used until 1989, when the Romanian Latin alphabet was introduced; in the breakaway territory of Transnistria the Cyrillic alphabet remains in use.

Romanian alphabet

The Romanian alphabet is as follows:

:

K, Q, W and Y, are not part of the native alphabet; they were officially introduced in the Romanian alphabet in 1982 and are mostly used to write loanwords like ''kilogram'', ''quasar'', ''watt'', and ''yoga''.

The Romanian alphabet is based on the Latin script

The Latin script, also known as the Roman script, is a writing system based on the letters of the classical Latin alphabet, derived from a form of the Greek alphabet which was in use in the ancient Greek city of Cumae in Magna Graecia. The Gree ...

with five additional letters , , , , . Formerly, there were as many as 12 additional letters, but some of them were abolished in subsequent reforms. Also, until the early 20th century, a breve marker was used, which survives only in ă.