Racism in the United States comprises negative attitudes and views on

race or ethnicity which are related to each other, are held by various people and groups in the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, and have been reflected in discriminatory laws, practices and actions (including violence) at various times in the

history of the United States

The history of the lands that became the United States began with the arrival of Settlement of the Americas, the first people in the Americas around 15,000 BC. Native American cultures in the United States, Numerous indigenous cultures formed ...

against racial or ethnic groups. Throughout American history,

white Americans

White Americans are Americans who identify as and are perceived to be white people. This group constitutes the majority of the people in the United States. As of the 2020 Census, 61.6%, or 204,277,273 people, were white alone. This represented ...

have generally enjoyed legally or socially sanctioned privileges and rights, which have been denied to members of various ethnic or minority groups at various times.

European Americans

European Americans (also referred to as Euro-Americans) are Americans of European ancestry. This term includes people who are descended from the first European settlers in the United States as well as people who are descended from more recent Eu ...

, particularly affluent

white Anglo-Saxon Protestants

In the United States, White Anglo-Saxon Protestants or WASPs are an ethnoreligious group who are the White Americans, white, American upper class, upper-class, Protestantism in the United States, American Protestant historical elite, typically ...

, are said to have enjoyed advantages in matters of education, immigration, voting rights, citizenship, land acquisition, and criminal procedure.

Racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism ...

against various ethnic or minority groups has existed in the United States since the early

colonial era. Before 1865, most

African Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

were

enslaved and even afterwards, they have faced severe restrictions on their political, social, and economic freedoms.

Native Americans have suffered

genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the Latin ...

,

forced removals, and

massacres

A massacre is the killing of a large number of people or animals, especially those who are not involved in any fighting or have no way of defending themselves. A massacre is generally considered to be morally unacceptable, especially when per ...

, and they continue to face

discrimination

Discrimination is the act of making unjustified distinctions between people based on the groups, classes, or other categories to which they belong or are perceived to belong. People may be discriminated on the basis of race, gender, age, relig ...

.

Hispanics

The term ''Hispanic'' ( es, hispano) refers to people, cultures, or countries related to Spain, the Spanish language, or Hispanidad.

The term commonly applies to countries with a cultural and historical link to Spain and to viceroyalties former ...

,

Middle Eastern and

Asian Americans

Asian Americans are Americans of Asian ancestry (including naturalized Americans who are immigrants from specific regions in Asia and descendants of such immigrants). Although this term had historically been used for all the indigenous people ...

along with

Pacific Islanders

Pacific Islanders, Pasifika, Pasefika, or rarely Pacificers are the peoples of the Pacific Islands. As an ethnic/ racial term, it is used to describe the original peoples—inhabitants and diasporas—of any of the three major subregions of Oce ...

have also been the victims of discrimination. In addition, non-

Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

immigrants from Europe, particularly

Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

,

Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland in Ce ...

,

Italians

, flag =

, flag_caption = The national flag of Italy

, population =

, regions = Italy 55,551,000

, region1 = Brazil

, pop1 = 25–33 million

, ref1 =

, region2 ...

, and the

Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

were often subjected to

xenophobic

Xenophobia () is the fear or dislike of anything which is perceived as being foreign or strange. It is an expression of perceived conflict between an in-group and out-group and may manifest in suspicion by the one of the other's activities, a ...

exclusion and other forms of ethnicity-based discrimination.

Racism has manifested itself in a variety of ways, including genocide, slavery,

lynchings,

segregation Segregation may refer to:

Separation of people

* Geographical segregation, rates of two or more populations which are not homogenous throughout a defined space

* School segregation

* Housing segregation

* Racial segregation, separation of humans ...

,

Native American reservations

An Indian reservation is an area of land held and governed by a federally recognized Native American tribal nation whose government is accountable to the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs and not to the state government in which it ...

and

boarding schools

A boarding school is a school where pupils live within premises while being given formal instruction. The word "boarding" is used in the sense of "room and board", i.e. lodging and meals. As they have existed for many centuries, and now exten ...

, racist immigration and

naturalization

Naturalization (or naturalisation) is the legal act or process by which a non-citizen of a country may acquire citizenship or nationality of that country. It may be done automatically by a statute, i.e., without any effort on the part of the in ...

laws, and

internment camps

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without Criminal charge, charges or Indictment, intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects ...

. Formal racial discrimination was largely banned by the mid-20th century and over time, coming to be perceived as socially and morally unacceptable. Racial politics remains a major phenomenon, and racism continues to be

reflected in socioeconomic inequality. Into the 21st century, research has uncovered extensive evidence of racial discrimination in various sectors of modern U.S. society, including the

criminal justice

Criminal justice is the delivery of justice to those who have been accused of committing crimes. The criminal justice system is a series of government agencies and institutions. Goals include the Rehabilitation (penology), rehabilitation of o ...

system,

business

Business is the practice of making one's living or making money by producing or Trade, buying and selling Product (business), products (such as goods and Service (economics), services). It is also "any activity or enterprise entered into for pr ...

, the

economy

An economy is an area of the production, distribution and trade, as well as consumption of goods and services. In general, it is defined as a social domain that emphasize the practices, discourses, and material expressions associated with the ...

,

housing

Housing, or more generally, living spaces, refers to the construction and assigned usage of houses or buildings individually or collectively, for the purpose of shelter. Housing ensures that members of society have a place to live, whether it ...

,

health care

Health care or healthcare is the improvement of health via the prevention, diagnosis, treatment, amelioration or cure of disease, illness, injury, and other physical and mental impairments in people. Health care is delivered by health profe ...

, the

media

Media may refer to:

Communication

* Media (communication), tools used to deliver information or data

** Advertising media, various media, content, buying and placement for advertising

** Broadcast media, communications delivered over mass el ...

, and

politics

Politics (from , ) is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The branch of social science that studies ...

. In the view of the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

and the

U.S. Human Rights Network, "

discrimination in the United States

Discrimination comprises "base or the basis of class or category without regard to individual merit, especially to show prejudice on the basis of ethnicity, gender, or a similar social factor". This term is used to highlight the difference in ...

permeates all aspects of life and extends to all

communities of color."

Aspects of American life

Citizenship and immigration

The

Naturalization Act of 1790

The Naturalization Act of 1790 (, enacted March 26, 1790) was a law of the United States Congress that set the first uniform rules for the granting of United States citizenship by naturalization. The law limited naturalization to "free White ...

set the first uniform rules for the granting of

United States citizenship

Citizenship of the United States is a legal status that entails Americans with specific rights, duties, protections, and benefits in the United States. It serves as a foundation of fundamental rights derived from and protected by the Cons ...

by

naturalization

Naturalization (or naturalisation) is the legal act or process by which a non-citizen of a country may acquire citizenship or nationality of that country. It may be done automatically by a statute, i.e., without any effort on the part of the in ...

, which limited naturalization to "free white person

, thus excluding Native Americans,

indentured servants

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repayment, ...

,

slaves

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

,

free Blacks and later Asians from citizenship. Citizenship and the lack of it profoundly impacted various legal and political rights, the most notable of which were

suffrage rights at both the federal and state level, the right to hold certain government offices,

jury duty

Jury duty or jury service is service as a juror in a legal proceeding.

Juror selection process

The prosecutor and defense can dismiss potential jurors for various reasons, which can vary from one state to another, and they can have a specifi ...

, military service in the

United States Armed Forces

The United States Armed Forces are the military forces of the United States. The armed forces consists of six service branches: the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, Space Force, and Coast Guard. The president of the United States is the ...

, as well as many other activities, besides access to

government assistance and services. The second

Militia Act of 1792

Two Militia Acts were enacted by the 2nd United States Congress in 1792 that provided for the organization of militias and empowered the President of the United States to take command of the state militias in times of imminent invasion or insurr ...

also provided for the

conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

of every "free able-bodied white male citizen". Tennessee's 1834 Constitution included a provision: “the free white men of this State have a right to Keep and bear arms for their common defense.”

The

Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek

The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek was a treaty which was signed on September 27, 1830, and proclaimed on February 24, 1831, between the Choctaw American Indian tribe and the United States Government. This treaty was the first removal treaty wh ...

, made under the

Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States President Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for ...

of 1830, allowed those

Choctaw

The Choctaw (in the Choctaw language, Chahta) are a Native American people originally based in the Southeastern Woodlands, in what is now Alabama and Mississippi. Their Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choctaw people are ...

Indians who chose to remain in

Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

to gain recognition as US citizens, the first major non-European ethnic group to become entitled to US citizenship.

Racial discrimination in naturalization and immigration continued despite the

Equal Protection Clause

The Equal Protection Clause is part of the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The clause, which took effect in 1868, provides "''nor shall any State ... deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal ...

in the

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fourteenth Amendment (Amendment XIV) to the United States Constitution was adopted on July 9, 1868, as one of the Reconstruction Amendments. Often considered as one of the most consequential amendments, it addresses citizenship rights and ...

(ratified in 1868). The Fourteenth Amendment overruled previous court decisions and gave U.S.-born African Americans citizenship through

birthright citizenship

''Jus soli'' ( , , ; meaning "right of soil"), commonly referred to as birthright citizenship, is the right of anyone born in the territory of a state to nationality or citizenship.

''Jus soli'' was part of the English common law, in contras ...

.

The

Naturalization Act of 1870

The Naturalization Act of 1870 () was a United States federal law that created a system of controls for the naturalization process and penalties for fraudulent practices. It is also noted for extending the naturalization process to "aliens of A ...

extended naturalization to Black persons, but not to other non-white persons, but revoked the citizenship of naturalized Chinese Americans. The law relied on coded language to exclude "aliens ineligible for citizenship" which primarily applied to

Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of ...

and

Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

immigrants.

Native Americans were granted citizenship in a piece-meal manner until the

Indian Citizenship Act of 1924

The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, (, enacted June 2, 1924) was an Act of the United States Congress that granted US citizenship to the indigenous peoples of the United States. While the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution ...

, which unilaterally bestowed blanket citizenship status on them, whether they belonged to a

federally recognized tribe

This is a list of federally recognized tribes in the contiguous United States of America. There are also federally recognized Alaska Native tribes. , 574 Indian tribes were legally recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) of the United ...

or not, though by that date, two-thirds of Native Americans had already become US citizens by various means. The Act was not retroactive, so citizenship was not extended to Native Americans who were born before the effective date of the 1924 Act, nor was it extended to indigenous persons who were born outside the United States.

Further changes to racial eligibility for citizenship by naturalization were made after 1940, when eligibility was extended to "descendants of races indigenous to the

Western Hemisphere

The Western Hemisphere is the half of the planet Earth that lies west of the prime meridian (which crosses Greenwich, London, United Kingdom) and east of the antimeridian. The other half is called the Eastern Hemisphere. Politically, the term We ...

," "Filipino persons or persons of Filipino descent," "Chinese persons or persons of Chinese descent," and "persons of races indigenous to India." The

Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (), also known as the McCarran–Walter Act, codified under Title 8 of the United States Code (), governs immigration to and citizenship in the United States. It came into effect on June 27, 1952. Before ...

now prohibits racial and gender discrimination in naturalization.

During the period when only "white" people could be naturalized, many court decisions were required to define which ethnic groups were included in this term. These are known as the "

racial prerequisite cases", and they also informed subsequent legislation.

Voting

The

Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fifteenth Amendment (Amendment XV) to the United States Constitution prohibits the federal government and each state from denying or abridging a citizen's right to vote "on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude." It was ...

(ratified in 1870), explicitly prohibited denying the right to vote based on race, but delegated to Congress the responsibility for enforcement.

During the

Reconstruction era

The Reconstruction era was a period in American history following the American Civil War (1861–1865) and lasting until approximately the Compromise of 1877. During Reconstruction, attempts were made to rebuild the country after the bloo ...

, African Americans began to run for office and vote, but the

Compromise of 1877

The Compromise of 1877, also known as the Wormley Agreement or the Bargain of 1877, was an unwritten deal, informally arranged among members of the United States Congress, to settle the intensely disputed 1876 presidential election between Ruth ...

ended the era of strong federal enforcement of equal rights in the Southern states. White Southerners were prevented by the Fifteenth Amendment from explicitly denying the vote to Blacks by law, but found other ways to

disenfranchise

Disfranchisement, also called disenfranchisement, or voter disqualification is the restriction of suffrage (the right to vote) of a person or group of people, or a practice that has the effect of preventing a person exercising the right to vote. ...

.

Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

that targeted African Americans without mentioning race included

poll taxes

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources.

Head taxes were important sources of revenue for many governments fr ...

,

literacy

Literacy in its broadest sense describes "particular ways of thinking about and doing reading and writing" with the purpose of understanding or expressing thoughts or ideas in written form in some specific context of use. In other words, huma ...

and comprehension tests for voters, residency and record-keeping requirements, and

grandfather clause

A grandfather clause, also known as grandfather policy, grandfathering, or grandfathered in, is a provision in which an old rule continues to apply to some existing situations while a new rule will apply to all future cases. Those exempt from t ...

s allowing White people to vote.

Black Codes criminalized minor offenses like unemployment (styled "vagrancy"), providing a pretext to deny voting rights. Extralegal violence was also used to terrorize and sometimes kill African Americans who attempted to register or to vote, often in the form of

lynching

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged transgressor, punish a convicted transgressor, or intimidate people. It can also be an ex ...

and

cross burning

In modern times, cross burning or cross lighting is a practice which is associated with the Ku Klux Klan. However, it was practiced long before the Klan's inception. Since the early 20th century, the Klan burned crosses on hillsides as a way to i ...

. These efforts to enforce white supremacy were very successful. For example, after 1890, less than 9,000 of Mississippi's 147,000 eligible African-American voters were registered to vote, or about 6%. Louisiana went from 130,000 registered African-American voters in 1896 to 1,342 in 1904 (about a 99% decrease).

Even Native Americans who gained citizenship under the 1924 Act were not guaranteed

voting rights

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

until 1948. According to a survey by the

Department of Interior, seven states still refused to grant Indians voting rights in 1938. Discrepancies between federal and state control provided loopholes in the Act's enforcement. States justified discrimination based on state statutes and constitutions. Three main arguments for Indian voting exclusion were Indian exemption from real estate taxes, maintenance of tribal affiliation and the notion that Indians were under guardianship, or lived on lands controlled by federal trusteeship.

By 1947, all states with large Indian populations, except

Arizona

Arizona ( ; nv, Hoozdo Hahoodzo ; ood, Alĭ ṣonak ) is a state in the Southwestern United States. It is the 6th largest and the 14th most populous of the 50 states. Its capital and largest city is Phoenix. Arizona is part of the Fou ...

and

New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ker ...

, had extended voting rights to Native Americans who qualified under the 1924 Act. Finally, in 1948, a judicial decision forced the remaining states to withdraw their prohibition on Indian voting.

The

civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

resulted in strong Congressional enforcement of the right to vote regardless of race, starting with the

Voting Rights Act of 1965

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of federal legislation in the United States that prohibits racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson during the height of the civil rights movement ...

. Though this greatly enhanced the ability of racial minorities to vote and run for office in all areas of the country, concerns over racially discriminatory voting laws and administration persist.

Gerrymandering

In representative democracies, gerrymandering (, originally ) is the political manipulation of electoral district boundaries with the intent to create undue advantage for a party, group, or socioeconomic class within the constituency. The m ...

and

voter suppression

Voter suppression is a strategy used to influence the outcome of an election by discouraging or preventing specific groups of people from voting. It is distinguished from political campaigning in that campaigning attempts to change likely voting ...

efforts around the country, though mainly motivated by political considerations, often effectively disproportionately affect African Americans and other minorities. These include targeted

voter ID

A voter identification law is a law that requires a person to show some form of identification in order to vote. In some jurisdictions requiring photo IDs, voters who do not have photo ID often must have their identity verified by someone els ...

requirements, registration hurdles, restricting vote-by-mail, and making voting facilities physically inconvenient to access due to long distances, long lines, or short hours. The 2013 U.S. Supreme court decision ''

Shelby County v. Holder'' struck down the pre-clearance provisions of the 1965 Act, making anti-discrimination enforcement more difficult.

In 2016, one in 13 African-Americans of voting age was disenfranchised, more than four times greater than that of non-African-Americans. Over 7.4% of adult African-Americans were disenfranchised compared to 1.8% of non-African-Americans.

Felony disenfranchisement in Florida disqualifies over 10% of its citizens for life and over 23% of its African-American citizens.

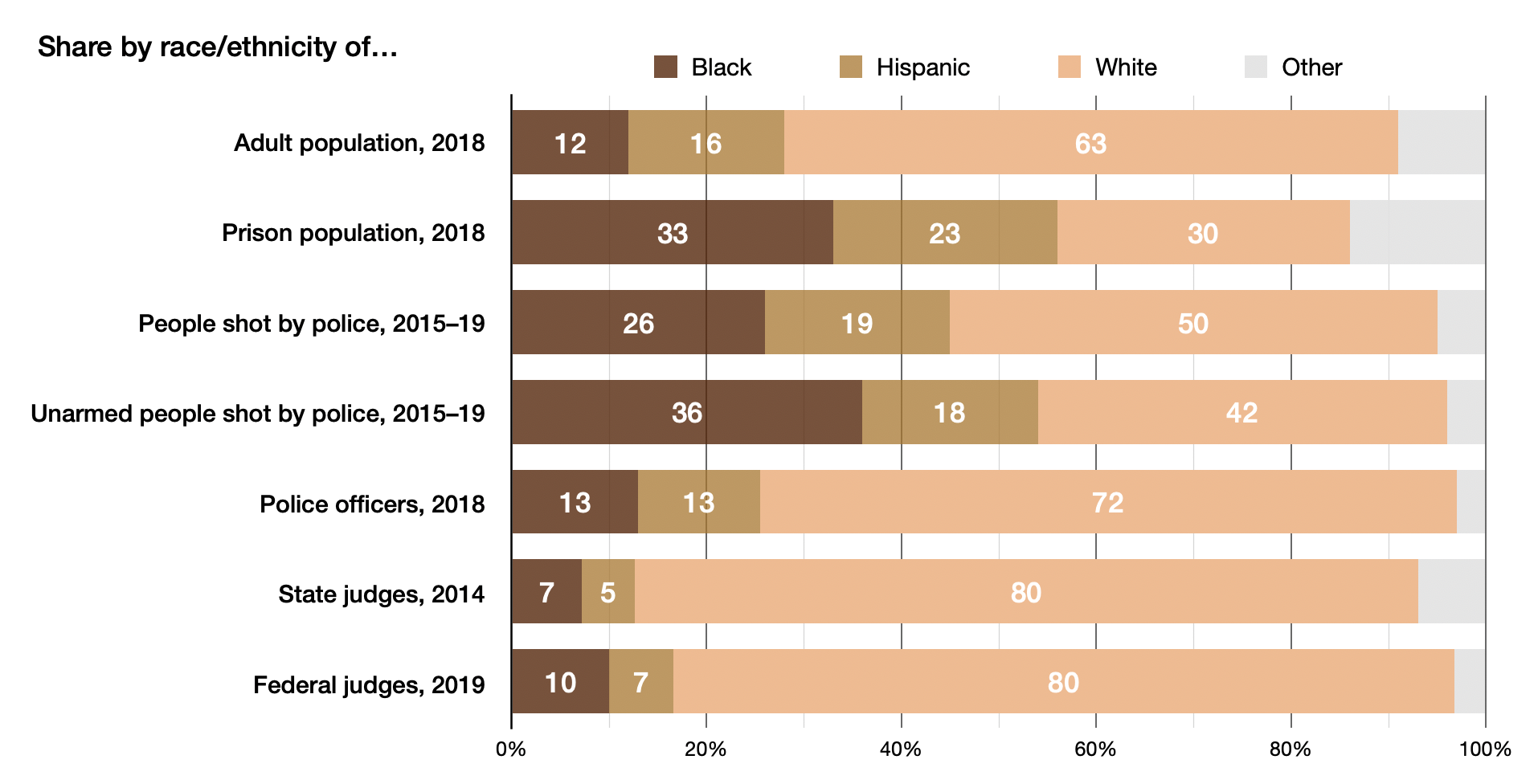

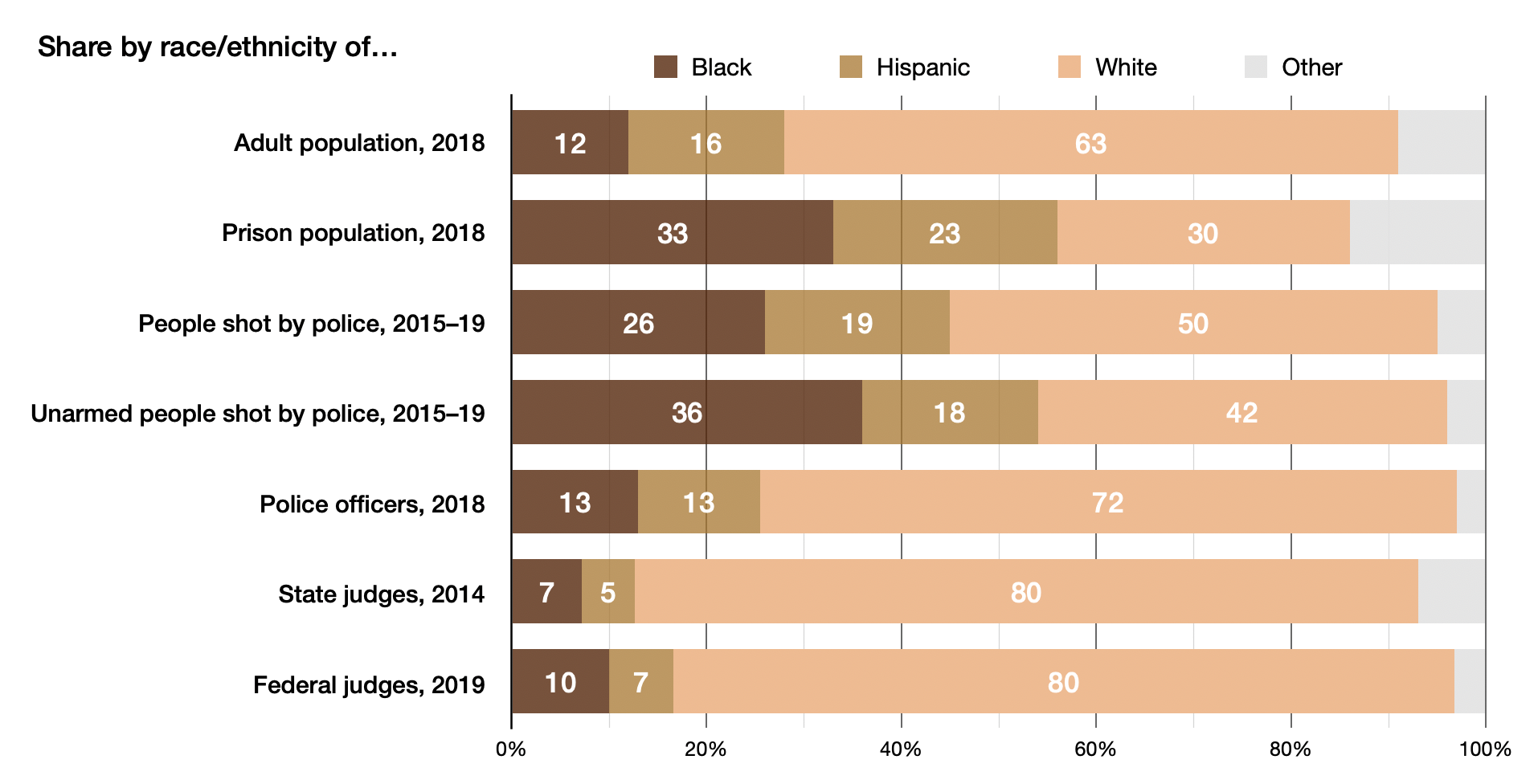

Criminal justice system

There are unique experiences and disparities in the United States in regard to the policing and prosecuting of various races and ethnicities. There have been different outcomes for different racial groups in convicting and sentencing felons in the

United States criminal justice system

Incarceration in the United States is a primary form of punishment and rehabilitation for the commission of felony and other offenses. The United States has the largest prison population in the world, and the highest per-capita incarceratio ...

.

[United States. Dept. of Justice. 2008. Bureau of Justice Statistics: Prison Statistics. Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Justice.] Experts and analysts have debated the relative importance of different factors that have led to these disparities.

Academic research indicates that the over-representation of some racial minorities in the criminal justice system can in part be explained by socioeconomic factors, such as poverty, exposure to poor neighborhoods, poor access to public education, poor access to early childhood education, and exposure to harmful chemicals (such as

lead

Lead is a chemical element with the symbol Pb (from the Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a heavy metal that is denser than most common materials. Lead is soft and malleable, and also has a relatively low melting point. When freshly cu ...

) and pollution.

Racial

housing segregation

Housing segregation in the United States is the practice of denying African Americans and other minority groups equal access to housing through the process of misinformation, denial of realty and financing services, and racial steering. Housing ...

has also been linked to racial disparities in crime rates, as Blacks have historically and to the present been prevented from moving into prosperous low-crime areas through actions of the government (such as

redlining

In the United States, redlining is a discriminatory practice in which services (financial and otherwise) are withheld from potential customers who reside in neighborhoods classified as "hazardous" to investment; these neighborhoods have signif ...

) and private actors. Various explanations within

criminology

Criminology (from Latin , "accusation", and Ancient Greek , ''-logia'', from λόγος ''logos'' meaning: "word, reason") is the study of crime and deviant behaviour. Criminology is an interdisciplinary field in both the behavioural and so ...

have been proposed for racial disparities in crime rates, including

conflict theory

Conflict may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

Films

* ''Conflict'' (1921 film), an American silent film directed by Stuart Paton

* ''Conflict'' (1936 film), an American boxing film starring John Wayne

* ''Conflict'' (1937 film) ...

,

strain theory,

general strain theory General strain theory (GST) is a theory of criminology developed by Robert Agnew. General strain theory has gained a significant amount of academic attention since being developed in 1992.

Robert Agnew's general strain theory is considered to be ...

,

social disorganization theory

In sociology, the social disorganization theory is a theory developed by the Chicago School, related to ecological theories. The theory directly links crime rates to neighbourhood ecological characteristics; a core principle of social disorgani ...

, macrostructural opportunity theory,

social control theory

In criminology, social control theory proposes that exploiting the process of socialization and social learning builds self-control and reduces the inclination to indulge in behavior recognized as antisocial. It derived from functionalist theor ...

, and

subcultural theory

In criminology, subcultural theory emerged from the work of the Chicago School on gangs and developed through the symbolic interactionism school into a set of theories arguing that certain groups or subcultures in society have values and attit ...

.

Research also indicates that there is extensive racial and ethnic discrimination by police and the judicial system.

A substantial academic literature has compared police searches (showing that contraband is found at higher rates in whites who are stopped), bail decisions (showing that whites with the same bail decision as Blacks commit more pre-trial violations), and sentencing (showing that Blacks are more harshly sentenced by juries and judges than whites when the underlying facts and circumstances of the cases are similar), providing valid causal inferences of racial discrimination.

Studies have documented patterns of racial discrimination, as well as patterns of police brutality and disregard for the constitutional rights of African-Americans, by police departments in various American cities, including

Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world' ...

,

New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

,

Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

and

Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

.

Education

In 1954, ''

Brown vs. the Board of Education'' ruled that

integrated, equal schools be accessible to all children unbiased to skin color. Currently in the United States, not all state funded schools are equally funded. Schools are funded by the "federal, state, and local governments" while "states play a large and increasing role in education funding."

"

Property tax

A property tax or millage rate is an ad valorem tax on the value of a property.In the OECD classification scheme, tax on property includes "taxes on immovable property or net wealth, taxes on the change of ownership of property through inheri ...

es support most of the funding that local government provides for education."

Schools located in lower income areas receive a lower level of funding and schools located in higher income areas receiving greater funding for education all based on property taxes. The

U.S. Department of Education

The United States Department of Education is a Cabinet-level department of the United States government. It began operating on May 4, 1980, having been created after the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare was split into the Department ...

reports that "many high-poverty schools receive less than their fair share of state and local funding, leaving students in high-poverty schools with fewer resources than schools attended by their wealthier peers."

The U.S. Department of Education also reports this fact affects "more than 40% of low-income schools."

Children of color are much more likely to suffer from poverty than white children.

The phrase "brown paper bag test," also known as a

paper bag party

"The Brown Paper Bag Test" is a term in African-American oral history used to describe a Discrimination based on skin color, colorist discriminatory practice within the African Americans, African-American community in the 20th century, in which ...

, along with the "ruler test" refers to a ritual once practiced by certain African-American sororities and fraternities who would not let anyone into the group whose skin tone was darker than a paper bag.

[Kerr, A. E. (2006). The paper bag principle: Class, colorism, and rumor in the case of black Washington, DC. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press.] Spike Lee

Shelton Jackson "Spike" Lee (born March 20, 1957) is an American film director, producer, screenwriter, and actor. His production company, 40 Acres and a Mule Filmworks, has produced more than 35 films since 1983. He made his directorial debut ...

's film ''

School Daze

''School Daze'' is a 1988 American musical comedy-drama film, written and directed by Spike Lee, and starring Laurence Fishburne (credited as Larry Fishburne), Giancarlo Esposito, and Tisha Campbell. Based in part on Spike Lee's experiences a ...

'' satirized this practice at historically Black colleges and universities. Along with the "paper bag test," guidelines for acceptance among the lighter ranks included the "comb test" and "pencil test," which tested the coarseness of one's hair, and the "flashlight test," which tested a person's profile to make sure their features measured up or were close enough to those of the Caucasian race.

Curriculum

The curriculum in U.S. schools has also contained racism against non-white Americans, including Native Americans,

Black Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American ...

,

Mexican Americans

Mexican Americans ( es, mexicano-estadounidenses, , or ) are Americans of full or partial Mexican heritage. In 2019, Mexican Americans comprised 11.3% of the US population and 61.5% of all Hispanic and Latino Americans. In 2019, 71% of Mexica ...

, and Asian Americans.

Particularly during the 19th and early 20th centuries, school textbooks and other teaching materials emphasized the biological and social inferiority of Black Americans, consistently portraying Black people as simple, irresponsible, and oftentimes, in situations of suffering that were implied to be their fault (and not the effects of slavery and other oppression).

[Elson, Ruth Miller (1964). ''Guardians of Tradition: American Schoolbooks of the Nineteenth Century''. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press.][Au, Wayne, 1972–. Reclaiming the multicultural roots of U.S. curriculum : communities of color and official knowledge in education. Brown, Anthony Lamar, Aramoni Calderón, Dolores,, Banks, James A. New York. . .] Black Americans were also depicted as expendable and their suffering as commonplace, as evidenced by a poem about "Ten Little Nigger Boys" dying off one by one that was circulated as a children's counting exercise from 1875 to the mid-1900s.

Historian

Carter G. Woodson

Carter Godwin Woodson (December 19, 1875April 3, 1950) was an American historian, author, journalist, and the founder of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH). He was one of the first scholars to study the h ...

analyzed American curriculum as completely lacking any mention of Black Americans' merits in the early 20th century. Based on his observations of the time, he wrote that American students, including Black students, who went through U.S. schooling would come out believing that Black people had no significant history and had contributed nothing to human civilization.

School curriculum often implicitly and explicitly upheld white people as the superior race and marginalized the contributions and perspectives of non-white peoples as if they were (or are) not as important.

[Mills, Charles W. (1994). "REVISIONIST ONTOLOGIES: THEORIZING WHITE SUPREMACY". Social and Economic Studies. 43 (3): 105–134. ISSN 0037-7651.] In the 19th century, a significant number of students were taught that

Adam and Eve

Adam and Eve, according to the creation myth of the Abrahamic religions, were the first man and woman. They are central to the belief that humanity is in essence a single family, with everyone descended from a single pair of original ancestors. ...

were white, and the other races evolved from their various descendants, growing further and further away from the original white standard.

In addition, whites were also fashioned as the capable caretakers of other races, namely Black and Native people, who could not take care of themselves.

This concept was at odds with the violence white Americans had committed against indigenous and Black peoples, but it was coupled with soft language that, for example, defended these acts. Mills (1994) cites the narrative about Europeans' "discovery" of a "

New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 3 ...

," despite the people who already inhabited it, and its subsequent "colonization" instead of conquest, as examples. He maintains that these word choices constitute a cooptation of history by white people, who have used it to their advantage.

Health

A 2019 review of the literature in the ''

Annual Review of Public health

The ''Annual Review of Public Health'' is a peer-reviewed academic journal that publishes review articles about public health, including epidemiology, biostatistics, occupational safety and health, environmental health, and health policy. In its 4 ...

'' found that

structural racism

A structure is an arrangement and organization of interrelated elements in a material object or system, or the object or system so organized. Material structures include man-made objects such as buildings and machines and natural objects such as ...

,

cultural racism

Cultural racism, sometimes called neo-racism, new racism, postmodern racism, or differentialist racism, is a concept that has been applied to prejudices and discrimination based on cultural differences between ethnic or racial groups. This inclu ...

, and individual-level discrimination are "a fundamental cause of adverse health outcomes for racial/ethnic minorities and racial/ethnic inequities in health."

Studies have argued that there are racial disparities in how the media and politicians act when they are faced with cases of drug addiction in which the victims are primarily Black rather than white, citing the examples of how society responded differently to the

crack epidemic

The crack epidemic was a surge of crack cocaine use in major cities across the United States throughout the entirety of the 1980s and the early 1990s. This resulted in a number of social consequences, such as increasing crime and violence in Ameri ...

than the

opioid epidemic

The opioid epidemic, also referred to as the opioid crisis, is the rapid increase in the overuse, misuse/abuse, and overdose deaths attributed either in part or in whole to the class of drugs opiates/opioids since the 1990s. It includes the sign ...

.

There are major

racial differences in access to health care as well as major racial differences in the quality of the health care which is provided to people. A study published in the ''American Journal of Public Health'' estimated that: "over 886,000 deaths could have been prevented from 1991 to 2000 if African Americans had received the same quality of care as whites". The key differences which they cited were lack of insurance, inadequate

insurance

Insurance is a means of protection from financial loss in which, in exchange for a fee, a party agrees to compensate another party in the event of a certain loss, damage, or injury. It is a form of risk management, primarily used to hedge ...

, poor service, and reluctance to seek care. A history of government-sponsored experimentation, such as the notorious

Tuskegee Syphilis Study

The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male (informally referred to as the Tuskegee Experiment or Tuskegee Syphilis Study) was a study conducted between 1932 and 1972 by the United States Public Health Service (PHS) and the Cente ...

has left a legacy of African American distrust of the medical system.

Inequalities in health care may also reflect a

systemic bias

Systemic bias, also called institutional bias, and related to structural bias, is the inherent tendency of a process to support particular outcomes. The term generally refers to human systems such as institutions. Institutional bias and structur ...

in the way in which medical procedures and treatments are prescribed to members of different ethnic groups. A

University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

Professor of Public Health, Raj Bhopal, writes that the history of

racism in science and medicine shows that people and institutions behave according to the ethos of their times and he also warns of dangers that need to be avoided in the future. A

Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

Professor of Social Epidemiology contended that much modern research supported the assumptions which were needed to justify racism. She writes that racism underlies unexplained inequities in health care, including treatments for

heart disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a class of diseases that involve the heart or blood vessels. CVD includes coronary artery diseases (CAD) such as angina and myocardial infarction (commonly known as a heart attack). Other CVDs include stroke, hea ...

,

renal failure

Kidney failure, also known as end-stage kidney disease, is a medical condition in which the kidneys can no longer adequately filter waste products from the blood, functioning at less than 15% of normal levels. Kidney failure is classified as eit ...

,

bladder cancer

Bladder cancer is any of several types of cancer arising from the tissues of the urinary bladder. Symptoms include blood in the urine, pain with urination, and low back pain. It is caused when epithelial cells that line the bladder become mali ...

, and

pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severity ...

. Bhopal writes that these inequalities have been documented in various studies and there are consistent findings that Black Americans receive less health care than white Americans—particularly where this involves expensive new technology. The University of Michigan Health study found in 2010 that black patients in pain clinics received 50% of the amount of drugs that other patients who were white received. Black pain in medicine links to the racial disparities between pain management and racial bias on behalf of the health professional. In 2011, Vermont organizers took a proactive stand against racism in their communities to defeat the biopolitical struggles faced on a daily basis. The first and only universal health care law was passed in the state.

Two local governments in the US have issued declarations stating that racism constitutes a

public health emergency

In public relations and communication science, publics are groups of individual people, and the public (a.k.a. the general public) is the totality of such groupings. This is a different concept to the sociological concept of the ''Öffentlichkei ...

: the

Milwaukee County, Wisconsin

Milwaukee County is located in the U.S. state of Wisconsin. At the 2020 census, the population was 939,489, down from 947,735 in 2010. It is both the most populous and most densely populated county in Wisconsin, and the 45th most populous coun ...

executive in May 2019, and the

Cleveland City Council

Cleveland City Council is the legislative branch of government for the City of Cleveland, Ohio. Its chambers are located at Cleveland City Hall at 601 Lakeside Avenue, across the street from Public Auditorium in Downtown Cleveland. Cleveland Ci ...

, in June 2020.

Housing and land

A 2014 meta-analysis found extensive evidence of racial discrimination in the American housing market.

Minority applicants for housing needed to make many more inquiries to view properties.

Geographical steering of African Americans in US housing remains significant.

A 2003 study found "evidence that agents interpret an initial housing request as an indication of a customer's preferences, but also are more likely to withhold a house from all customers when it is in an integrated suburban neighborhood (

redlining

In the United States, redlining is a discriminatory practice in which services (financial and otherwise) are withheld from potential customers who reside in neighborhoods classified as "hazardous" to investment; these neighborhoods have signif ...

). Moreover, agents' marketing efforts increase with asking price for white, but not for black, customers; blacks are more likely than whites to see houses in suburban, integrated areas (

steering

Steering is a system of components, linkages, and other parts that allows a driver to control the direction of the vehicle.

Introduction

The most conventional steering arrangement allows a driver to turn the front wheels of a vehicle using ...

); and the houses agents show are more likely to deviate from the initial request when the customer is black than when the customer is white. These three findings are consistent with the possibility that agents act upon the belief that some types of transactions are relatively unlikely for black customers (statistical discrimination)." Historically, there was extensive and long-lasting racial discrimination against African Americans in the housing and mortgage markets in the United States, as well as discrimination against Black farmers whose numbers massively declined in post-WWII America due to anti-Black local and federal policies. According to a 2019 analysis by University of Pittsburgh economists, Blacks faced a two-fold penalty due to the racially segregated housing market: rental prices increased in blocks when they underwent racial transition whereas home values declined in neighborhoods that Blacks moved into.

A 2017 paper by Troesken and Walsh found that pre-20th century cities "created and sustained residential segregation through private norms and vigilante activity." However, "when these private arrangements began to break down during the early 1900s" whites started "lobbying municipal governments for segregation ordinances." As a result, cities passed ordinances which "prohibited members of the majority racial group on a given city block from selling or renting property to members of another racial group" between 1909 and 1917.

A 2017 study by Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago economists found that the practice of

redlining

In the United States, redlining is a discriminatory practice in which services (financial and otherwise) are withheld from potential customers who reside in neighborhoods classified as "hazardous" to investment; these neighborhoods have signif ...

—the practice whereby banks discriminated against the inhabitants of certain neighborhoods—had a persistent adverse impact on the neighborhoods, with redlining affecting homeownership rates, home values and credit scores in 2010.

Since many African Americans could not access conventional home loans, they had to turn to predatory lenders (who charged high interest rates).

Due to lower homeownership rates, slumlords were able to rent out apartments that would otherwise be owned.

A 2019 analysis estimated that predatory housing contracts targeting African Americans in Chicago in the 1950s and 1960s cost Black families between $3 billion and $4 billion in wealth.

Labor market

Several meta-analyses find extensive evidence of ethnic and racial discrimination in hiring in the American labor market.

A 2017 meta-analysis found "no change in the levels of discrimination against African Americans since 1989, although we do find some indication of declining discrimination against Latinos." A 2016 meta-analysis of 738 correspondence tests – tests where identical CVs for stereotypically Black and white names were sent to employers – in 43 separate studies conducted in OECD countries between 1990 and 2015 finds that there is extensive racial discrimination in hiring decisions in Europe and North America.

These correspondence tests showed that equivalent minority candidates need to send around 50% more applications to be invited for an interview than majority candidates.

A study which examined the job applications of actual people who were provided with identical résumés and similar interview training showed that African-American applicants with no criminal record were offered jobs at a rate as low as white applicants who had criminal records. A 2018 National Bureau of Economic Research paper found evidence of racial bias in how CVs were evaluated. A 2020 study revealed that discrimination not only exists against minorities in callback rates in audit studies, it also increases in severity after the callbacks in terms of job offers.

Research suggests that light-skinned African American women have higher salaries and greater job satisfaction than dark-skinned women.

Being "too black" has recently been acknowledged by the U.S. Federal courts in an employment discrimination case under Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and United States labor law, labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on Race (human categorization), race, Person of color, color, religion, sex, and nationa ...

. In ''Etienne v. Spanish Lake Truck & Casino Plaza, LLC'' the

United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

The United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit (in case citations, 5th Cir.) is a federal court with appellate jurisdiction over the district courts in the following federal judicial districts:

* Eastern District of Louisiana

* M ...

, determined that an employee who was told on several occasions that her manager thought she was "too black" to do various tasks, found that the issue of the employee's skin color rather than race itself, played a key role in an employer's decision to keep the employee from advancing. A 2018 study uncovered evidence which suggests that immigrants with darker skin colors are discriminated against.

Media

A 2017 report by Travis L. Dixon (of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign) found that major media outlets tended to portray Black families as dysfunctional and dependent while white families were portrayed as stable. These portrayals may suggest that poverty and welfare are primarily Black issues. According to Dixon, this can reduce public support for social safety programs and lead to stricter welfare requirements.

African Americans who possess a lighter skin complexion and "European features," such as lighter eyes, and smaller noses and lips have more opportunities in the media industry. For example, film producers hire lighter-skinned African Americans more often, television producers choose lighter-skinned cast members, and magazine editors choose African American models that resemble European features. A content analysis conducted by Scott and Neptune (1997) shows that less than one percent of advertisements in major magazines featured African American models. When African Americans did appear in advertisements they were mainly portrayed as athletes, entertainers, or unskilled laborers. In addition, seventy percent of the advertisements that feature animal print included African American women. Animal print reinforces the stereotypes that African Americans are animalistic in nature, sexually active, less educated, have lower income, and extremely concerned with personal appearances.

Concerning African American males in the media, darker-skinned men are more likely to be portrayed as violent or more threatening, influencing the public perception of African American men. Since dark-skinned males are more likely to be linked to crime and misconduct, many people develop preconceived notions about the characteristics of Black men.

During and after slavery, minstrel shows were a very popular form of theater that involved white and Black people in

Blackface

Blackface is a form of theatrical makeup used predominantly by non-Black people to portray a caricature of a Black person.

In the United States, the practice became common during the 19th century and contributed to the spread of racial stereo ...

portraying Black people while doing demeaning things. The actors painted their faces with Black paint and overlined their lips with bright red lipstick to exaggerate and make fun of Black people. When minstrel shows died out and television became popular, Black actors were rarely hired and when they were, they had very specific roles. These roles included being servants, slaves, idiots, and criminals.

Politics

Politically, the "

winner-takes-all" structure of the

electoral college benefits white representation.

This has been described as structural bias and often leads voters of color to feel

politically alienated, and therefore not to vote. The lack of representation in Congress has also led to lower voter turnout.

As of 2016, African Americans only made up 8.7% of Congress, and Latinos 7%.

Voter ID laws

A voter identification law is a law that requires a person to show some form of identification in order to vote. In some jurisdictions requiring photo IDs, voters who do not have photo ID often must have their identity verified by someone els ...

have brought on accusations of racial discrimination. In a 2014 review by the

Government Accountability Office

The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) is a legislative branch government agency that provides auditing, evaluative, and investigative services for the United States Congress. It is the supreme audit institution of the federal govern ...

of the academic literature, three studies out of five found that voter ID laws reduced minority turnout whereas two studies found no significant impact.

Disparate impact may also be reflected in access to information about voter ID laws. A 2015 experimental study found that election officials queried about voter ID laws are more likely to respond to emails from a non-Latino white name (70.5% response rate) than a Latino name (64.8% response rate), though response accuracy was similar across groups. Studies have also analyzed racial differences in ID requests rates. A 2012 study in the city of Boston found that Black and Hispanic voters were more likely to be asked for ID during the 2008 election. According to exit polls, 23% of whites, 33% of Blacks, and 38% of Hispanics were asked for ID, though this effect is partially attributed to Black and Hispanics preferring non-peak voting hours when election officials inspected a greater portion of IDs. Precinct differences also confound the data as Black and Hispanic voters tended to vote at Black and Hispanic-majority precincts. A 2015 study found that turnout among Blacks in Georgia was generally higher since the state began enforcing its strict voter ID law. A 2016 study by

University of California, San Diego

The University of California, San Diego (UC San Diego or colloquially, UCSD) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in San Diego, California. Established in 1960 near the pre-existing Scripps Insti ...

researchers found that voter ID laws "have a differentially negative impact on the turnout of Hispanics, Blacks, and mixed-race Americans in primaries and general elections."

Research by University of Oxford economist Evan Soltas and Stanford political scientist David Broockman suggests that voters act upon racially discriminatory tastes. A 2018 study in ''

Public Opinion Quarterly

''Public Opinion Quarterly'' is an academic journal published by Oxford University Press for the American Association for Public Opinion Research, covering communication studies and political science. It was established in 1937 and according to t ...

'' found that whites, in particular those who had racial resentment, largely attributed Obama's success among African-Americans to his race, and not his characteristics as a candidate and the political preferences of African-Americans. A 2018 study in the journal ''

American Politics Research

''American Politics Research'' is a peer-reviewed academic journal that covers the subfield of American politics in the discipline of political science. The journal's editor-in-chief is Costas Panagopolous ( Northeastern University). It was est ...

'' found that white voters tended to misperceive political candidates from racial minorities as being more ideologically extreme than objective indicators would suggest; this adversely affected the electoral chances for those candidates. A 2018 study in the ''

Journal of Politics

''The Journal of Politics'' is a peer-reviewed academic journal of political science established in 1939 and published quarterly (February, May, August and November) by University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Southern Political Science Assoc ...

'' found that "when a white candidate makes vague statements, many

onblackvoters project their own policy positions onto the candidate, increasing support for the candidate. But they are less likely to extend black candidates the same courtesy... In fact, black male candidates who make ambiguous statements are actually punished for doing so by racially prejudiced voters."

It is argued that the racial coding of concepts like crime and welfare has been used to strategically influence public political views. Racial coding is implicit; it incorporates racially primed language or imagery to allude to racial attitudes and thinking. For example, in the context of domestic policy, it is argued that

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

implied that linkages existed between concepts like "special interests" and "

big government" and ill-perceived minority groups in the 1980s, using the conditioned negativity which existed toward the minority groups to discredit certain policies and programs during campaigns. In a study which analyzes how political ads prime attitudes, Valentino compares the voting responses of participants after they are exposed to the narration of a George W. Bush advertisement which is paired with three different types of visuals which contain different embedded racial cues to create three conditions: neutral, race comparison, and undeserving Blacks. For example, as the narrator states "Democrats want to spend your tax dollars on wasteful government programs", the video shows an image of a Black woman and her child in an office setting. Valentino found that the undeserving Blacks condition produced the largest primed effect in racialized policies, like opposition to

affirmative action and welfare spending.

Ian Haney López

Ian F. Haney López (born 1964) is the Chief Justice Earl Warren Professor of Public Law at the University of California, Berkeley. He works in the area of racism and racial justice in American law.

Life and career

Haney López born on July 6, ...

, Professor of Law at the

University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of California, it is the state's first land-grant u ...

, refers to the phenomenon of racial coding as

dog-whistle politics

In politics, a dog whistle is the use of coded or suggestive language in political messaging to garner support from a particular group without provoking opposition. The concept is named after ultrasonic dog whistles, which are audible to dogs bu ...

, which, he argues, has pushed middle class white Americans to vote against their economic self-interest to punish "undeserving minorities" which, they believe, are receiving too much public assistance at their expense. According to López, conservative middle-class whites, convinced that minorities are the enemy by powerful economic interests, supported politicians who promised to curb illegal immigration and crack down on crime, but inadvertently they also voted for policies that favor the extremely rich, such as slashing taxes for top income brackets, giving corporations more regulatory control over industry and financial markets,

busting unions, cutting pensions for future public employees, reducing funding for public schools, and retrenching the social welfare state. He argues that these same voters cannot link rising inequality which has impacted their lives to the policy agendas which they support, which resulted in a massive transfer of wealth to the top 1% of the population since the 1980s.

A book released by the former attorney of

Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Trump graduated from the Wharton School of the University of Pe ...

,

Michael Cohen, in September 2020, ''

Disloyal: A Memoir'' described Trump as routinely referring to Black leaders of foreign nations with racial insults, and that he was consumed with hatred for

Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, Obama was the first African-American president of the U ...

. Cohen in the book explained that "as a rule, Trump expressed low opinions of all Black folks, from music to culture and politics".

Religion

Wealth

Large racial differentials in wealth remain in the United States: between whites and African Americans, the gap is a factor of twenty. An analyst of the phenomenon, Thomas Shapiro, professor of law and social policy at Brandeis University argues, "The

wealth gap

There are wide varieties of economic inequality, most notably income inequality measured using the distribution of income (the amount of money people are paid) and wealth inequality measured using the distribution of wealth (the amount of we ...

is not just a story of merit and achievement, it's also a story of the historical legacy of race in the United States." Differentials applied to the

Social Security Act

The Social Security Act of 1935 is a law enacted by the 74th United States Congress and signed into law by US President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The law created the Social Security program as well as insurance against unemployment. The law was pa ...

(which excluded agricultural workers, a sector which then included most black workers), rewards to military officers, and the educational benefits offered returning soldiers after

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. Pre-existing disparities in wealth are exacerbated by tax policies that reward investment over waged income, subsidize mortgages, and subsidize private sector developers.

A 2014 meta-analysis of racial discrimination in product markets found extensive evidence of minority applicants being quoted higher prices for products.

Historically, African-Americans have faced discrimination in terms of getting access to credit.

African Americans

Antebellum period

Between 1626 and 1860, the

Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and i ...

brought more than 470,000 enslaved Africans to what is now the United States. White European Americans who participated in the slave industry tried to justify their economic exploitation of

Black people

Black is a racialized classification of people, usually a political and skin color-based category for specific populations with a mid to dark brown complexion. Not all people considered "black" have dark skin; in certain countries, often in s ...

by creating a

"scientific" theory of white superiority and Black inferiority.

One such slave owner was

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

, and it was his call for science to determine the obvious "inferiority" of Blacks that is regarded as "an extremely important stage in the evolution of scientific racism." He concluded that Blacks were "inferior to the whites in the endowments of body and mind."

After the importation of

slaves into the United States was outlawed by federal law from 1808, the

domestic slave trade

The domestic slave trade, also known as the Second Middle Passage and the interregional slave trade, was the term for the domestic trade of enslaved people within the United States that reallocated slaves across states during the Antebellum perio ...

expanded to replace it.

Maryland and Virginia, for example, would "export" their surplus slaves to the South. These sales of slaves broke up many families, with historian

Ira Berlin

Ira Berlin (May 27, 1941 – June 5, 2018) was an American historian, professor of history at the University of Maryland, and former president of Organization of American Historians.

Berlin is the author of such books as ''Many Thousands Gone: T ...

writing that whether slaves were directly uprooted or lived in fear that they or their families would be involuntarily moved, "the massive deportation traumatized black people".

During the 1820s and 1830s, the

American Colonization Society

The American Colonization Society (ACS), initially the Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America until 1837, was an American organization founded in 1816 by Robert Finley to encourage and support the migration of freebor ...

established the colony of

Liberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to its north, Ivory Coast to its east, and the Atlantic Ocean ...

and persuaded thousands of free Black Americans to move there because many members of the white elite both in the North and the South saw them as a problem to be got rid of.

Even figures, such as

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

, who opposed slavery showed ingrained racist attitudes. Lincoln said during the Fourth

Lincoln-Douglas debate held in Charleston, Illinois, on September 18, 1858: "I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races,

pplausethat I am not nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people; and I will say in addition to this that there is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will forever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality. And inasmuch as they cannot so live, while they do remain together there must be the position of superior and inferior, and I as much as any other man am in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race."

During and immediately after the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, about four million enslaved African Americans were set free, major legal actions being

President Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

’s

Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the Civil War. The Proclamation changed the legal sta ...

which came into effect on January 1, 1863, and the

Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Thirteenth Amendment (Amendment XIII) to the United States Constitution abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime. The amendment was passed by the Senate on April 8, 1864, by the House of Representative ...

which finally abolished slavery in December 1865.

Reconstruction Era to World War II

After the

Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

, the

Reconstruction Era

The Reconstruction era was a period in American history following the American Civil War (1861–1865) and lasting until approximately the Compromise of 1877. During Reconstruction, attempts were made to rebuild the country after the bloo ...

was characterized by the passage of federal legislation which was designed to protect the rights of the formerly enslaved people, including the

Civil Rights Act of 1866

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 (, enacted April 9, 1866, reenacted 1870) was the first United States federal law to define citizenship and affirm that all citizens are equally protected by the law. It was mainly intended, in the wake of the Amer ...

and the

Civil Rights Act of 1875. The

Fourteenth amendment granted full citizenship to African Americans and the

Fifteenth amendment guaranteed the

voting rights

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

of African-American men (see

Reconstruction Amendments

The , or the , are the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth amendments to the United States Constitution, adopted between 1865 and 1870. The amendments were a part of the implementation of the Reconstruction of the American South which occ ...

).

Despite this,

white supremacists

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White su ...

came to power in all Southern states, by intimidating Black voters with the assistance of terrorist groups like the

Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

, the

Red Shirts and the

White League

The White League, also known as the White Man's League, was a white paramilitary terrorist organization started in the Southern United States in 1874 to intimidate freedmen into not voting and prevent Republican Party political organizing. Its f ...

. "

Black Codes" and

Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

deprived African Americans of voting rights and other civil liberties by instituting systemic and discriminatory policies of unequal

racial segregation