Rupert Brooke on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Rupert Chawner Brooke (3 August 1887 – 23 April 1915)The date of Brooke's death and burial under the

Brooke was born at 5 Hillmorton Road,

Brooke was born at 5 Hillmorton Road,  Brooke attended preparatory (prep) school locally at

Brooke attended preparatory (prep) school locally at

Brooke made friends among the Bloomsbury group of writers, some of whom admired his talent while others were more impressed by his good looks. He also belonged to another literary group known as the

Brooke made friends among the Bloomsbury group of writers, some of whom admired his talent while others were more impressed by his good looks. He also belonged to another literary group known as the

Brooke sailed with the British Mediterranean Expeditionary Force on 28 February 1915 but developed a severe gastroenteritis whilst stationed in Egypt followed by streptococcal

Brooke sailed with the British Mediterranean Expeditionary Force on 28 February 1915 but developed a severe gastroenteritis whilst stationed in Egypt followed by streptococcal  However, in 1919,

However, in 1919,

Rupert Brooke Society

Rupert Brooke on Skyros

Schroder Collection (Rupert Brooke), Cambridge University Digital Library

digitised correspondence etc. between Brooke, Edward Marsh, and

Rupert Brooke profile and poems on Poets.org

Rupert Brooke on Poemist

* * *

Bartleby.com

– Collected Poems

Rupert Brooke at the Commonwealth War Graves Commission database

Rupert Brooke Correspondence and Writings

at Dartmouth College Library {{DEFAULTSORT:Brooke, Rupert 1887 births 1915 deaths 20th-century English male writers 20th-century English poets Alumni of King's College, Cambridge Bisexual men Burials in Greece Deaths from sepsis English male poets English World War I poets Fellows of King's College, Cambridge Infectious disease deaths in Greece English LGBT poets Bisexual writers Members of the Fabian Society People educated at Rugby School People from Grantchester People from Rugby, Warwickshire Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve personnel of World War I Royal Navy officers of World War I Skyros Sonneteers War writers Deaths due to insect bites and stings British military personnel killed in World War I Lost Generation writers Military personnel from Warwickshire

Julian calendar

The Julian calendar, proposed by Roman consul Julius Caesar in 46 BC, was a reform of the Roman calendar. It took effect on , by edict. It was designed with the aid of Greek mathematicians and astronomers such as Sosigenes of Alexandr ...

that applied in Greece at the time was 10 April. The Julian calendar was 13 days behind the Gregorian calendar

The Gregorian calendar is the calendar used in most parts of the world. It was introduced in October 1582 by Pope Gregory XIII as a modification of, and replacement for, the Julian calendar. The principal change was to space leap years dif ...

. was an English poet known for his idealistic

In philosophy, the term idealism identifies and describes metaphysical

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality ...

war sonnets written during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, especially " The Soldier". He was also known for his boyish good looks, which were said to have prompted the Irish poet W. B. Yeats

William Butler Yeats (13 June 186528 January 1939) was an Irish poet, dramatist, writer and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. He was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival and became a pillar of the Irish liter ...

to describe him as "the handsomest young man in England".

Early life

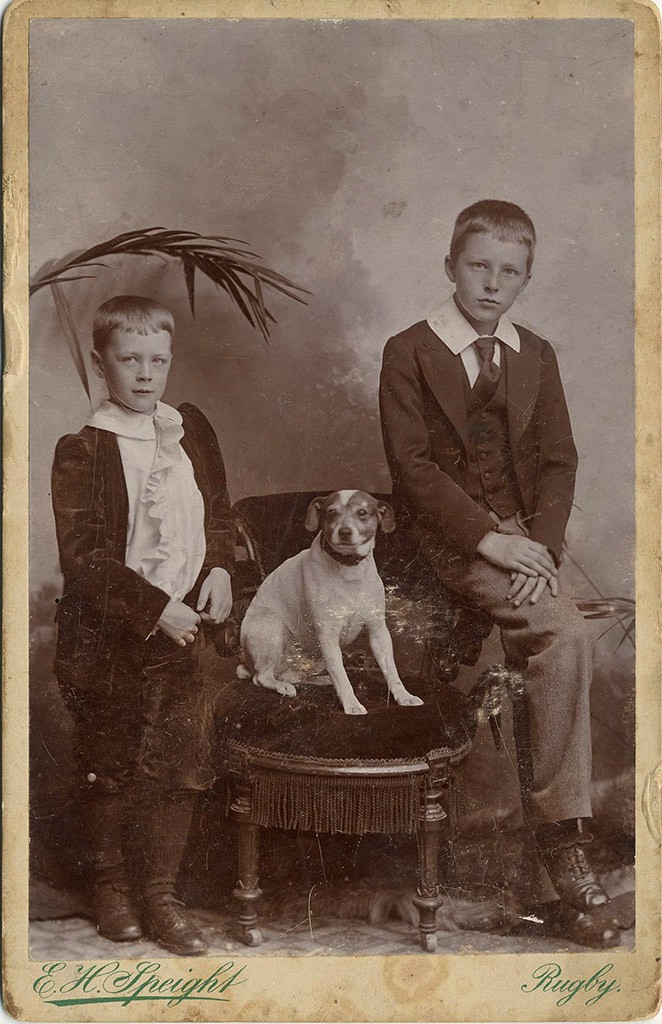

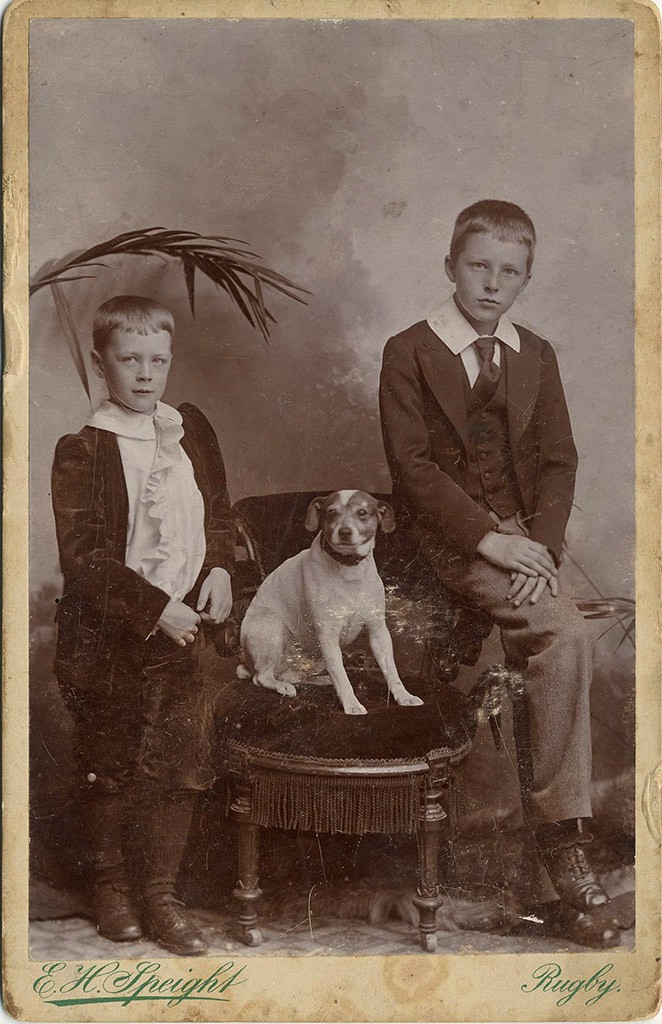

Brooke was born at 5 Hillmorton Road,

Brooke was born at 5 Hillmorton Road, Rugby, Warwickshire

Rugby is a market town in eastern Warwickshire, England, close to the River Avon. In the 2021 census its population was 78,125, making it the second-largest town in Warwickshire. It is the main settlement within the larger Borough of Rugby whi ...

, and named after a great-grandfather on his mother's side, Rupert Chawner (1750–1836), a distinguished doctor descended from the regicide Thomas Chaloner (the middle name has however sometimes been erroneously given as "Chaucer"). He was the third of four children of William Parker "Willie" Brooke, a schoolmaster (teacher), and Ruth Mary Brooke, née Cotterill, a school matron. Both parents were working at Fettes College

Fettes College () is a co-educational independent boarding and day school in Edinburgh, Scotland, with over two-thirds of its pupils in residence on campus. The school was originally a boarding school for boys only and became co-ed in 1983. In ...

in Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

when they met. They married on 18 December 1879. William Parker Brooke had to resign after the couple wed as there was no accommodation there for married masters. The couple then moved to Rugby in Warwickshire where Rupert's father became Master of School Field House at Rugby School

Rugby School is a public school (English independent boarding school for pupils aged 13–18) in Rugby, Warwickshire, England.

Founded in 1567 as a free grammar school for local boys, it is one of the oldest independent schools in Britain. ...

a month later. His eldest brother was Richard England "Dick" Brooke (1881–1907), his sister Edith Marjorie Brooke was born in 1885 and died the following year, and his youngest brother was William Alfred Cotterill "Podge" Brooke (1891–1915).

Brooke attended preparatory (prep) school locally at

Brooke attended preparatory (prep) school locally at Hillbrow

Hillbrow () is an inner city residential neighbourhood of Johannesburg, Gauteng Province, South Africa. It is known for its high levels of population density, unemployment, poverty, prostitution and crime.

In the 1970s it was an Apartheid-design ...

, and then went on to Rugby School. At Rugby he was romantically involved with fellow pupils Charles Lascelles, Denham Russell-Smith and Michael Sadleir

Michael Sadleir (25 December 1888 – 13 December 1957), born Michael Thomas Harvey Sadler, was a British publisher, novelist, book collector, and bibliographer.

Biography

Michael Sadleir was born in Oxford, England, the son of Sir Michael ...

. In 1905, he became friends with St. John Lucas, who thereafter became something of a mentor to him.

In October 1906 he went up to King's College, Cambridge

King's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Formally The King's College of Our Lady and Saint Nicholas in Cambridge, the college lies beside the River Cam and faces out onto King's Parade in the centre of the city ...

to study Classics. There he became a member of the Apostles, was elected as president of the university Fabian Society

The Fabian Society is a British socialist organisation whose purpose is to advance the principles of social democracy and democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist effort in democracies, rather than by revolutionary overthrow. The Fa ...

, helped found the Marlowe Society

The Marlowe Society is a Cambridge University theatre club for Cambridge students. It is dedicated to achieving a high standard of student drama at Cambridge. The society celebrated its centenary over three years (2007–2009) and in 2008 there wa ...

drama club and acted, including in the Cambridge Greek Play. The friendships he made at school and university set the course for his adult life, and many of the people he met—including George Mallory

George Herbert Leigh Mallory (18 June 1886 – 8 or 9 June 1924) was an English mountaineer who took part in the first three British expeditions to Mount Everest in the early 1920s.

Born in Cheshire, Mallory became a student at Winchest ...

—fell under his spell. Virginia Woolf

Adeline Virginia Woolf (; ; 25 January 1882 28 March 1941) was an English writer, considered one of the most important modernist 20th-century authors and a pioneer in the use of stream of consciousness as a narrative device.

Woolf was born i ...

told Vita Sackville-West

Victoria Mary, Lady Nicolson, CH (née Sackville-West; 9 March 1892 – 2 June 1962), usually known as Vita Sackville-West, was an English author and garden designer.

Sackville-West was a successful novelist, poet and journalist, as wel ...

that she had gone skinny-dipping

Nude swimming is the practice of swimming without clothing, whether in natural bodies of water or in swimming pools. A colloquial term for nude swimming is '' skinny-dipping''.

In both British and American English, to swim means "to move throu ...

with Brooke in a moonlit pool when they were in Cambridge together. In 1907, his older brother Dick died of pneumonia at age 26. Brooke planned to put his studies on hold to help his parents cope with the loss of his brother, but they insisted he return to university.

There is a blue plaque at The Orchard where he lived and wrote. The words read thus« Rupert Brooke Poet & Soldier 1887-1915 Lived and wrote at The Orchard 1909-1911, and at The Old Vicarage 1911-1912 »

Life and career

Georgian Poets

Georgian Poetry refers to a series of anthologies showcasing the work of a school of English poetry that established itself during the early years of the reign of King George V of the United Kingdom.

The Georgian poets were, by the strictest ...

and was one of the most important of the Dymock poets

The Dymock poets were a literary group of the early 20th century who made their homes near the village of Dymock in Gloucestershire, in England, near to the border with Herefordshire.

Significant figures and events

The 'Dymock Poets' are genera ...

, associated with the Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire ( abbreviated Glos) is a county in South West England. The county comprises part of the Cotswold Hills, part of the flat fertile valley of the River Severn and the entire Forest of Dean.

The county town is the city of Gl ...

village of Dymock

Dymock is a village and civil parish in the Forest of Dean district of Gloucestershire, England, about four miles south of Ledbury. In 2014 the parish had an estimated population of 1,205.

Dymock is the origin of the Dymock Red, a cider appl ...

where he spent some time before the war. This group included both Robert Frost

Robert Lee Frost (March26, 1874January29, 1963) was an American poet. His work was initially published in England before it was published in the United States. Known for his realistic depictions of rural life and his command of American colloq ...

and Edward Thomas. He also lived at the Old Vicarage

Old or OLD may refer to:

Places

*Old, Baranya, Hungary

*Old, Northamptonshire, England

* Old Street station, a railway and tube station in London (station code OLD)

*OLD, IATA code for Old Town Municipal Airport and Seaplane Base, Old Town, Ma ...

, Grantchester

Grantchester is a village and civil parish on the River Cam or Granta in South Cambridgeshire, England. It lies about south of Cambridge.

Name

The village of Grantchester is listed in the 1086 Domesday Book as ''Grantesete'' and ''Graunts ...

, which stimulated one of his best-known poems, named after the house, written with homesickness while in Berlin in 1912. While travelling in Europe he prepared a thesis, entitled "John Webster

John Webster (c. 1580 – c. 1632) was an English Jacobean dramatist best known for his tragedies '' The White Devil'' and '' The Duchess of Malfi'', which are often seen as masterpieces of the early 17th-century English stage. His life and c ...

and the Elizabethan Drama

English Renaissance theatre, also known as Renaissance English theatre and Elizabethan theatre, refers to the theatre of England between 1558 and 1642.

This is the style of the plays of William Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe and Ben Jonson ...

", which earned him a Fellowship at King's College, Cambridge

King's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Formally The King's College of Our Lady and Saint Nicholas in Cambridge, the college lies beside the River Cam and faces out onto King's Parade in the centre of the city ...

in March 1913.

Brooke had his first heterosexual relationship with Élisabeth van Rysselberghe

Élisabeth van Rysselberghe (15 October 1890 – 29 July 1980) was a Belgian translator. She was the daughter of Belgian painter Théo van Rysselberghe.

Biography

Élisabeth van Rysselberghe was born on 15 October 1890 in Brussels, Belgium. She w ...

, daughter of painter Théo van Rysselberghe

Théophile "Théo" van Rysselberghe (23 November 1862 – 13 December 1926) was a Belgian neo-impressionist painter, who played a pivotal role in the European art scene at the turn of the twentieth century.

Biography

Early years

Born ...

. They met in 1911 in Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the States of Germany, German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the List of cities in Germany by popu ...

. His affair with Elisabeth came closest to be consummated than any other he ever had so far. It is possible that the two became lovers in a "complete sense" in May 1913 in Swanley

Swanley is a town and civil parish in the Sevenoaks District of Kent, England, southeast of central London, adjacent to the Greater London boundary and within the M25 motorway periphery. The population at the 2011 census was 16,226.

History

...

. It was in Munich, where he had met Elisabeth, that a year later he finally succeeded in having intercourse with Ka Cox (Katherine Laird Cox

Katherine Laird "Ka" Cox (1887–23 May 1938), the daughter of a British socialist stockbroker and his wife, was a Fabian and graduate of Cambridge University. There, she met Rupert Brooke, becoming his lover, and was a member of his Neo-Pa ...

}.

Brooke suffered a severe emotional crisis in 1912, caused by sexual confusion (he was bisexual

Bisexuality is a romantic or sexual attraction or behavior toward both males and females, or to more than one gender. It may also be defined to include romantic or sexual attraction to people regardless of their sex or gender identity, whi ...

) and jealousy, resulting in the breakdown of his long relationship with Ka Cox. Brooke's paranoia that Lytton Strachey

Giles Lytton Strachey (; 1 March 1880 – 21 January 1932) was an English writer and critic. A founding member of the Bloomsbury Group and author of ''Eminent Victorians'', he established a new form of biography in which psychological insight ...

had schemed to destroy his relationship with Cox by encouraging her to see Henry Lamb

Henry Taylor Lamb (21 June 1883 – 8 October 1960) was an Australian-born British painter. A follower of Augustus John, Lamb was a founder member of the Camden Town Group in 1911 and of the London Group in 1913.

Early life

Henry Lamb was bo ...

precipitated his break with his Bloomsbury group friends and played a part in his nervous collapse and subsequent rehabilitation trips to Germany.

As part of his recuperation, Brooke toured the United States and Canada to write travel diaries for the ''Westminster Gazette

''The Westminster Gazette'' was an influential Liberal newspaper based in London. It was known for publishing sketches and short stories, including early works by Raymond Chandler, Anthony Hope, D. H. Lawrence, Katherine Mansfield, and Saki, ...

''. He took the long way home, sailing across the Pacific and staying some months in the South Seas

Today the term South Seas, or South Sea, is used in several contexts. Most commonly it refers to the portion of the Pacific Ocean south of the equator. In 1513, when Spanish conquistador Vasco Núñez de Balboa coined the term ''Mar del Sur'', ...

. Much later it was revealed that he may have fathered a daughter with a Tahitian woman named Taatamata with whom he seems to have enjoyed his most complete emotional relationship. Many more people were in love with him. Brooke was romantically involved with the artist Phyllis Gardner

Phyllis Gardner (6 October 1890 – 16 February 1939) was a writer, artist, and noted breeder of Irish Wolfhounds. She and Rupert Brooke had, on her side at least, a passionate relationship. She attended the Slade School of Fine Art and was a ...

and the actress Cathleen Nesbitt

Cathleen Nesbitt (born Kathleen Mary Nesbitt; 24 November 18882 August 1982) was an English actress.

Biography

Born in Birkenhead, Cheshire,Before 1 April 1974 Birkenhead was in Cheshire England to Thomas and Mary Catherine (née Parry) Nesb ...

, and was once engaged to Noël Olivier

Hon. Noël Olivier Richards (25 December 1892 – 11 April 1969) was an English medical doctor. She was born on Christmas Day 1892, hence her name, as the daughter of Sydney Olivier, 1st Baron Olivier and Margaret Cox. A cousin was the actor Si ...

, whom he met, when she was aged 15, at the progressive Bedales School

Bedales School is a co-educational, boarding and day independent school in the village of Steep, near the market town of Petersfield in Hampshire, England. It was founded in 1893 by John Haden Badley in reaction to the limitations of conven ...

.

Brooke enlisted at the outbreak of war in August 1914. He came to public attention as a war poet early the following year, when ''The Times Literary Supplement

''The Times Literary Supplement'' (''TLS'') is a weekly literary review published in London by News UK, a subsidiary of News Corp.

History

The ''TLS'' first appeared in 1902 as a supplement to ''The Times'' but became a separate publication i ...

'' published two sonnets ("IV: The Dead" and "V: The Soldier") on 11 March; the latter was then read from the pulpit of St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in London and is the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London. It is on Ludgate Hill at the highest point of the City of London and is a Grad ...

on Easter Sunday (4 April). Brooke's most famous collection of poetry, containing all five sonnets, ''1914 & Other Poems'', was first published in May 1915 and, in testament to his popularity, ran to 11 further impressions that year and by June 1918 had reached its 24th impression; a process undoubtedly fuelled through posthumous interest.

Brooke's accomplished poetry gained many enthusiasts and followers, and he was taken up by Edward Marsh, who brought him to the attention of Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, then First Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible for the di ...

. Brooke was commissioned into the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve as a temporary sub-lieutenant

Sub-lieutenant is usually a junior officer rank, used in armies, navies and air forces.

In most armies, sub-lieutenant is the lowest officer rank. However, in Brazil, it is the highest non-commissioned rank, and in Spain, it is the second high ...

shortly after his 27th birthday and took part in the Royal Naval Division's Antwerp expedition in October 1914.

Death

sepsis

Sepsis, formerly known as septicemia (septicaemia in British English) or blood poisoning, is a life-threatening condition that arises when the body's response to infection causes injury to its own tissues and organs. This initial stage is follo ...

from an infected mosquito bite. French surgeons carried out two operations to drain the abscess but he died of septicaemia at 4:46 pm on 23 April 1915, on the French hospital ship

A hospital ship is a ship designated for primary function as a floating medical treatment facility or hospital. Most are operated by the military forces (mostly navies) of various countries, as they are intended to be used in or near war zones. ...

'' Duguay-Trouin'', moored in a bay off the Greek island of Skyros

Skyros ( el, Σκύρος, ), in some historical contexts Latinized Scyros ( grc, Σκῦρος, ), is an island in Greece, the southernmost of the Sporades, an archipelago in the Aegean Sea. Around the 2nd millennium BC and slightly later, the ...

in the Aegean Sea, while on his way to the landings at Gallipoli. As the expeditionary force had orders to depart immediately, Brooke was buried at 11 pm in an olive grove on Skyros. The site was chosen by his close friend, William Denis Browne

William Charles Denis Browne (3 November 1888 – 4 June 1915), primarily known as Billy to family and as Denis to his friends, was a British composer, pianist, organist and music critic of the early 20th century. He and his close friend, poet Ru ...

, who wrote of Brooke's death:

Another friend and war poet, Patrick Shaw-Stewart

Patrick Houston Shaw-Stewart (17 August 1888 – 30 December 1917) was a British scholar and poet of the Edwardian era who died on active service as a battalion commander in the Royal Naval Division during the First World War. He is best remember ...

, assisted at his hurried funeral. His grave remains there still, with a monument erected by his friend Stanley Casson, poet and archaeologist, who in 1921 published ''Rupert Brooke and Skyros'', a "quiet essay", illustrated with woodcuts by Phyllis Gardner

Phyllis Gardner (6 October 1890 – 16 February 1939) was a writer, artist, and noted breeder of Irish Wolfhounds. She and Rupert Brooke had, on her side at least, a passionate relationship. She attended the Slade School of Fine Art and was a ...

.

On 11 November 1985, Brooke was among 16 First World War poets commemorated on a slate monument unveiled in Poets' Corner

Poets' Corner is the name traditionally given to a section of the South Transept of Westminster Abbey in the City of Westminster, London because of the high number of poets, playwrights, and writers buried and commemorated there.

The first poe ...

in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

. The inscription on the stone was written by a fellow war poet, Wilfred Owen

Wilfred Edward Salter Owen MC (18 March 1893 – 4 November 1918) was an English poet and soldier. He was one of the leading poets of the First World War. His war poetry on the horrors of trenches and gas warfare was much influenced b ...

. It reads: "My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity."

The wooden cross that marked Brooke's grave on Skyros, which was painted and carved with his name, was removed when a permanent memorial was made there. His mother, Mary Ruth Brooke, had the cross brought to Rugby, to the family plot at Clifton Road Cemetery. Because of erosion in the open air, it was removed from the cemetery in 2008 and replaced by a more permanent marker. The Skyros cross is now at Rugby School with the memorials of other Old Rugbeians.

Brooke's surviving brother, William Alfred Cotterill Brooke, fell in action on the Western Front on 14 June 1915 as a subaltern

Subaltern may refer to:

*Subaltern (postcolonialism), colonial populations who are outside the hierarchy of power

* Subaltern (military), a primarily British and Commonwealth military term for a junior officer

* Subalternation, going from a univer ...

with the 1/8th (City of London) of the London Regiment (Post Office Rifles

The Post Office Rifles was a unit of the British Army, first formed in 1868 from volunteers as part of the Volunteer Force, which later became the Territorial Force (and later the Territorial Army). The unit evolved several times until 1921, aft ...

), at the age of 24 years. He had been in France on active service for nineteen days before meeting his death. His body was buried in Fosse 7 Military Cemetery (Quality Street), Mazingarbe

Mazingarbe (; pcd, Mazingarpe) is a commune in the Pas-de-Calais department in the Hauts-de-France region of France.

History

The village was known as Masengarba in 1046, Masengarbe in 1232 and Mazengarbe in 1558.

Mazingarbe's first inhabitan ...

.

In July 1917 Field Marshal Edmund Allenby

Field Marshal Edmund Henry Hynman Allenby, 1st Viscount Allenby, (23 April 1861 – 14 May 1936) was a senior British Army officer and Imperial Governor. He fought in the Second Boer War and also in the First World War, in which he led th ...

was informed of the death in action of his son Michael Allenby, leading to Allenby's break down in tears in public while he recited a poem by Rupert Brooke.

The first stanza of " The Dead" is inscribed onto the base of the Royal Naval Division War Memorial

The Royal Naval Division Memorial is a First World War memorial located on Horse Guards Parade in central London, and dedicated to members of the 63rd (Royal Naval) Division (RND) killed in that conflict. Sir Edwin Lutyens designed the memorial ...

in London.

American adventurer Richard Halliburton

Richard Halliburton (January 9, 1900 – Declared death in absentia, presumed dead after March 24, 1939) was an American travel writing, travel writer and adventurer who swam the length of the Panama Canal and paid the lowest toll in its hi ...

made preparations for writing a biography of Brooke, meeting his mother and others who had known the poet, and corresponding widely and collecting copious notes, but he died before writing the manuscript. Halliburton's notes were used by Arthur Springer to write ''Red Wine of Youth: A Biography of Rupert Brooke''.

Lord Alfred Douglas

Lord Alfred Bruce Douglas (22 October 1870 – 20 March 1945), also known as Bosie Douglas, was an English poet and journalist, and a lover of Oscar Wilde. At Oxford he edited an undergraduate journal, ''The Spirit Lamp'', that carried a homoer ...

(in the afterword of his ''Collected Poems'') wrote: "... never before in the history of English literature has poetry sunk so low. When a nation which has produced Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

and Marlowe Marlowe may refer to:

Name

* Christopher Marlowe (1564–1593), English dramatist, poet and translator

* Philip Marlowe, fictional hardboiled detective created by author Raymond Chandler

* Marlowe (name), including list of people and characters w ...

and Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer (; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for '' The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He w ...

and Milton and Shelley and Wordsworth

William Wordsworth (7 April 177023 April 1850) was an English Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication ''Lyrical Ballads'' (1798).

Wordsworth's '' ...

and Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824), known simply as Lord Byron, was an English romantic poet and peer. He was one of the leading figures of the Romantic movement, and has been regarded as among the ...

and Keats

John Keats (31 October 1795 – 23 February 1821) was an English poet of the second generation of Romantic poets, with Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley. His poems had been in publication for less than four years when he died of tuberculos ...

and Tennyson

Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson (6 August 1809 – 6 October 1892) was an English poet. He was the Poet Laureate during much of Queen Victoria's reign. In 1829, Tennyson was awarded the Chancellor's Gold Medal at Cambridge for one of his ...

and Blake

Blake is a surname which originated from Old English. Its derivation is uncertain; it could come from "blac", a nickname for someone who had dark hair or skin, or from "blaac", a nickname for someone with pale hair or skin. Another theory, presuma ...

can seriously lash itself into enthusiasm over the puerile crudities (when they are nothing worse) of a Rupert Brooke, it simply means that poetry is despised and dishonoured and that sane criticism is dead or moribund."

In popular culture

*Frederick Septimus Kelly

Frederick Septimus Kelly (29 May 1881 – 13 November 1916) was an Australian and British musician and composer and a rower who competed in the 1908 Summer Olympics. After surviving the Gallipoli campaign He was killed in action in the Battle ...

wrote his "Elegy, In Memoriam Rupert Brooke for harp and strings" after attending Brooke's death and funeral. He also took Brooke's notebooks containing important late poems for safekeeping and later returned them to England.

*Brooke was an inspiration to John Gillespie Magee Jr., who attended Rugby a generation later and won the same poetry prize as his predecessor. Magee is best known for his poems "High Flight" and "Sonnet to Rupert Brooke".

*F. Scott Fitzgerald

Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald (September 24, 1896 – December 21, 1940) was an American novelist, essayist, and short story writer. He is best known for his novels depicting the flamboyance and excess of the Jazz Age—a term he popularize ...

's debut novel, ''This Side of Paradise

''This Side of Paradise'' is the debut novel by American writer F. Scott Fitzgerald, published in 1920. It examines the lives and morality of carefree American youth at the dawn of the Jazz Age. Its protagonist, Amory Blaine, is an attractive ...

'' (1920), opens with the quotation "Well this side of Paradise!… There's little comfort in the wise. — Rupert Brooke". Rupert Brooke is also referenced in other parts of the book.

*Dutch composer Marjo Tal Marjo Tal (15 January 1915 - 27 August 2006) was a Dutch composer and pianist who wrote the music for over 150 songs and often performed them while accompanying herself on the piano.

Life and career Early life

Tal was born in The Hague, the oldest ...

set several of Brooke’s poems to music.

* Charles Ives set to music a portion of Brooke's poem "The Old Vicarage, Grantchester" in his ''114 Songs'' published in 1921.

*A saying by Brooke was mentioned in Princess Elizabeth's Act of Dedication speech on her 21st birthday in 1947: "Let us say with Rupert Brooke, now God be thanked who has matched us with this hour."

* The opening two stanzas of his poem "Dust" were set to music by the pop group Fleetwood Mac

Fleetwood Mac are a British-American rock band, formed in London in 1967. Fleetwood Mac were founded by guitarist Peter Green, drummer Mick Fleetwood and guitarist Jeremy Spencer, before bassist John McVie joined the line-up for their epony ...

and appear on their 1972 album ''Bare Trees

''Bare Trees'' is the sixth studio album by British-American rock band Fleetwood Mac, released in March 1972. It was their last album to feature Danny Kirwan, who was fired during the album's supporting tour. In the wake of the band's success in ...

''.

*In a 1974 episode of the TV series ''M*A*S*H

''M*A*S*H'' (Mobile Army Surgical Hospital) is an American media franchise consisting of a series of novels, a film, several television series, plays, and other properties, and based on the semi-autobiographical fiction of Richard Hooker.

Th ...

'', "Springtime", Cpl. Klinger reads from a book of Brooke's poems, which he won in a poker game. Later, Radar uses the book to try to seduce a nurse, mispronouncing the author's name as "Ruptured Brook".

*" Is There Honey Still for Tea?" is the third episode of the eighth series of ''Dad's Army

''Dad's Army'' is a British television British sitcom, sitcom about the United Kingdom's Home Guard (United Kingdom), Home Guard during the World War II, Second World War. It was written by Jimmy Perry and David Croft (TV producer), David Crof ...

'', 1975

*In the fourth and final episode of the 2003 BBC series ''Cambridge Spies'', British-Soviet spy Kim Philby

Harold Adrian Russell "Kim" Philby (1 January 191211 May 1988) was a British intelligence officer and a double agent for the Soviet Union. In 1963 he was revealed to be a member of the Cambridge Five, a spy ring which had divulged British secr ...

recites the final line from Brooke's " The Old Vicarage, Grantchester" along with his then wife, Aileen Furse.

*The novel '' The Stranger's Child'' (2011) by Alan Hollinghurst

Alan James Hollinghurst (born 26 May 1954) is an English novelist, poet, short story writer and translator. He won the 1989 Somerset Maugham Award, the 1994 James Tait Black Memorial Prize and the 2004 Booker Prize.

Early life and education

H ...

features fictional war poet Cecil Valance, who shares characteristics of, though is not as talented as, Brooke.

*Brooke is a minor character in A. S. Byatt's novel ''The Children's Book

''The Children's Book'' is a 2009 novel by British writer A. S. Byatt. It follows the adventures of several inter-related families, adults and children, from 1895 through World War I. Loosely based upon the life of children's writer E. Nesbit th ...

'' (2009).

See also

*List of Bloomsbury Group people

This is a list of people associated with the Bloomsbury Group. Much about the group is controversial, including its membership: it has been said that "the three words 'the Bloomsbury group' have been so much used as to have become almost unusable" ...

References

Notes General references * *Brooke, Rupert, ''Letters From America'' with a Preface byHenry James

Henry James ( – ) was an American-British author. He is regarded as a key transitional figure between literary realism and literary modernism, and is considered by many to be among the greatest novelists in the English language. He was the ...

(London: Sidgwick & Jackson, Ltd, 1916; repr. 1947).

*Dawson, Jill, ''The Great Lover'' (London: Sceptre, 1990). A historical novel about Brooke and his relationship with a Tahitian woman, Taatamata, in 1913–14 and with Nell Golightly a maid where he was living.

*Delany, Paul. "Fatal Glamour: the Life of Rupert Brooke." (Montreal: McGillQueens UP, 2015).

*Halliburton, Richard, ''The Glorious Adventure'' (New York and Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1927). Traveller/travel writer Halliburton, in recreating Odysseus' adventures, visits the grave of Brooke on the Greek island of Skyros.

*Keith Hale, ed. ''Friends and Apostles: The Correspondence of Rupert Brooke-James Strachey, 1905–1914''.

*Gerry Max, ''Horizon Chasers – The Lives and Adventures of Richard Halliburton and Paul Mooney'' (McFarland, c2007). References are made to the poet throughout. Quoted, p. 11.

*Gerry Max, "'When Youth Kept Open House' – Richard Halliburton and Thomas Wolfe

Thomas Clayton Wolfe (October 3, 1900 – September 15, 1938) was an American novelist of the early 20th century.

Wolfe wrote four lengthy novels as well as many short stories, dramatic works, and novellas. He is known for mixing highly origin ...

", ''North Carolina Literary Review,'' 1996, Issue Number 5. Two early 20th century writers and their debt to the poet.

*Moran, Sean Farrell, "Patrick Pearse and the European Revolt Against Reason", ''The Journal of the History of Ideas'',50,4,423-66

*Morley, Christopher, "Rupert Brooke" in ''Shandygaff – A number of most agreeable ''Inquirendoes'' upon ''Life & Letters'', interspersed with ''Short Stories & Skits'', the Whole Most Diverting to the Reader'' (New York: Garden City Publishing Company, 1918), pp. 58–71. An important early reminiscence and appraisal by famed essayist and novelist Morley.

*Sellers Leonard. ''The Hood Battalion'' - Royal Naval Division. Leo Cooper, Pen & Sword Books Ltd. 1995, Select Edition 2003 - Rupert Brooke was an officer of Hood Battalion, 2nd Brigade, Royal Naval Division.

*Arthur Stringer. ''Red Wine of Youth—A Biography of Rupert Brooke'' (New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1952). Partly based on extensive correspondence between American travel writer Richard Halliburton

Richard Halliburton (January 9, 1900 – Declared death in absentia, presumed dead after March 24, 1939) was an American travel writing, travel writer and adventurer who swam the length of the Panama Canal and paid the lowest toll in its hi ...

and the literary and salon figures who had known Brooke.

*Christopher Hassall. "''Rupert Brooke: A Biography''" (Faber and Faber 1964)

*Sir Geoffrey Keynes, ed. "''The Letters of Rupert Brooke''" (Faber and Faber 1968)

*Colin Wilson. "''Poetry & Mysticism''" (City Lights Books 1969). Contains a chapter about Rupert Brooke.

*John Lehmann. "''Rupert Brooke: His Life and His Legend''" (George Weidenfeld & Nicolson Ltd 1980)

*Paul Delany. "''The Neo-Pagans: Friendship and Love in the Rupert Brooke Circle''" (Macmillan 1987)

*Mike Read. "''Forever England: The Life of Rupert Brooke''" (Mainstream Publishing Company Ltd 1997)

*Timothy Rogers. "''Rupert Brooke: A Reappraisal and Selection''" (Routledge, 1971)

*Robert Scoble. ''The Corvo Cult: The History of an Obsession'' (Strange Attractor, 2014)

*Christian Soleil. "''Rupert Brooke: Sous un ciel anglais''" (Edifree, France, 2009)

*Christian Soleil. "''Rupert Brooke: L'Ange foudroyé''" (Monpetitediteur, France, 2011)

External links

Rupert Brooke Society

Rupert Brooke on Skyros

Schroder Collection (Rupert Brooke), Cambridge University Digital Library

digitised correspondence etc. between Brooke, Edward Marsh, and

William Denis Browne

William Charles Denis Browne (3 November 1888 – 4 June 1915), primarily known as Billy to family and as Denis to his friends, was a British composer, pianist, organist and music critic of the early 20th century. He and his close friend, poet Ru ...

Rupert Brooke profile and poems on Poets.org

Rupert Brooke on Poemist

* * *

Bartleby.com

– Collected Poems

Rupert Brooke at the Commonwealth War Graves Commission database

Rupert Brooke Correspondence and Writings

at Dartmouth College Library {{DEFAULTSORT:Brooke, Rupert 1887 births 1915 deaths 20th-century English male writers 20th-century English poets Alumni of King's College, Cambridge Bisexual men Burials in Greece Deaths from sepsis English male poets English World War I poets Fellows of King's College, Cambridge Infectious disease deaths in Greece English LGBT poets Bisexual writers Members of the Fabian Society People educated at Rugby School People from Grantchester People from Rugby, Warwickshire Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve personnel of World War I Royal Navy officers of World War I Skyros Sonneteers War writers Deaths due to insect bites and stings British military personnel killed in World War I Lost Generation writers Military personnel from Warwickshire