Rudolph Rocker on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

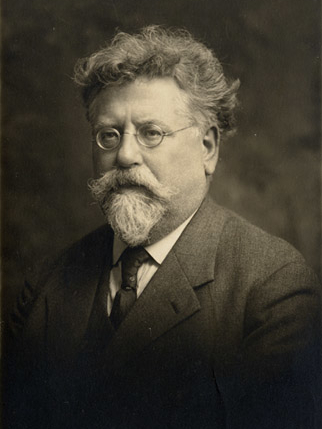

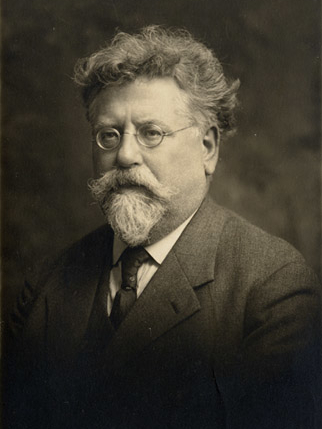

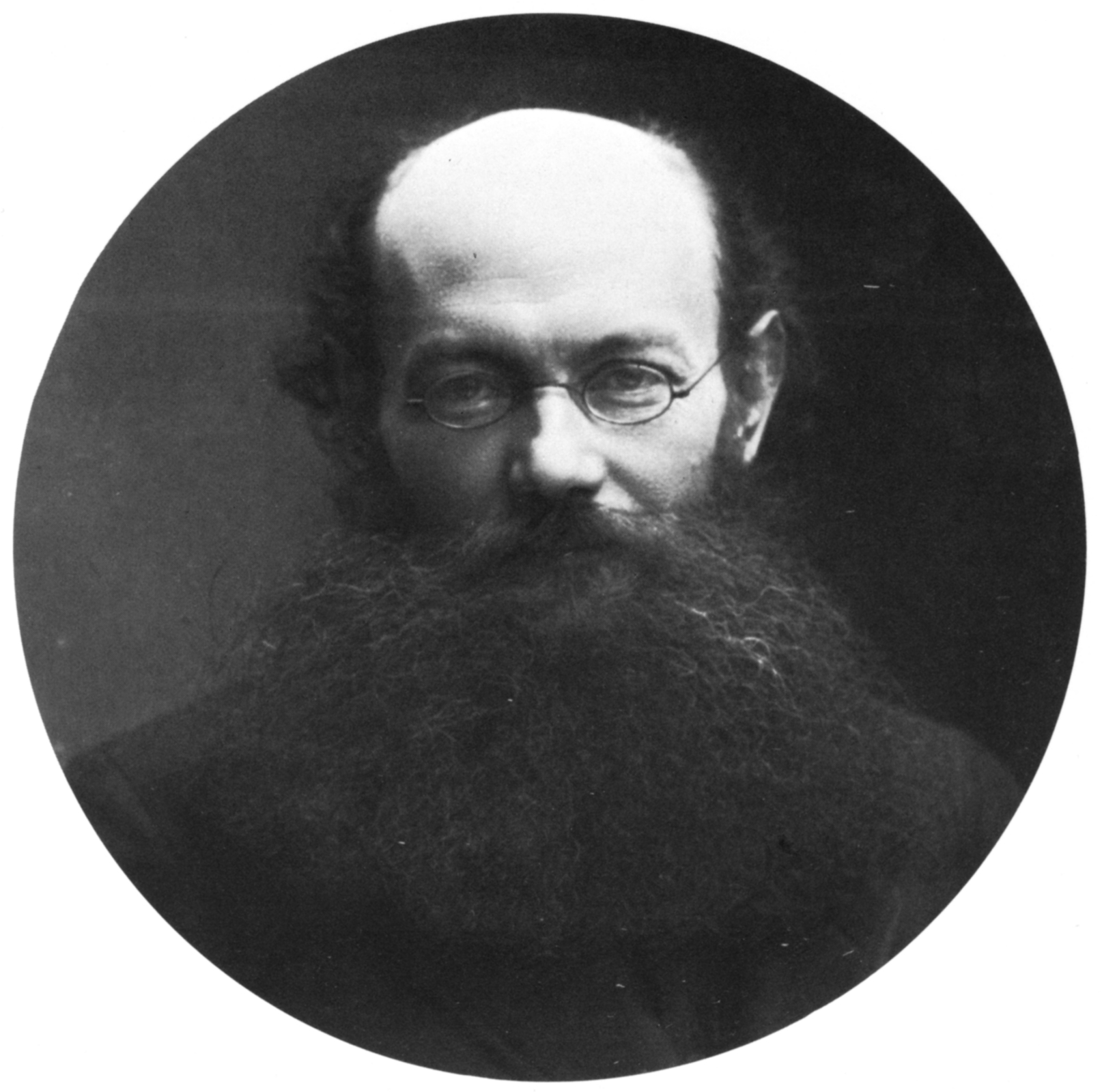

Johann Rudolf Rocker (March 25, 1873 – September 19, 1958) was a German anarchist writer and activist. He was born in

Rocker became convinced that the source of political institutions is an irrational belief in a higher authority, as Bakunin claimed in ''God and the State''. However, Rocker rejected the Russian's rejection of theoretical propaganda and his claim that only

Rocker became convinced that the source of political institutions is an irrational belief in a higher authority, as Bakunin claimed in ''God and the State''. However, Rocker rejected the Russian's rejection of theoretical propaganda and his claim that only

In Paris, he first came into contact with

In Paris, he first came into contact with

Although it received some funds from Jews in New York, the journal's financial survival was precarious from the start. However, many volunteers helped by selling the paper on street corners and in workshops. During this time, Rocker was especially concerned with combating the influence of

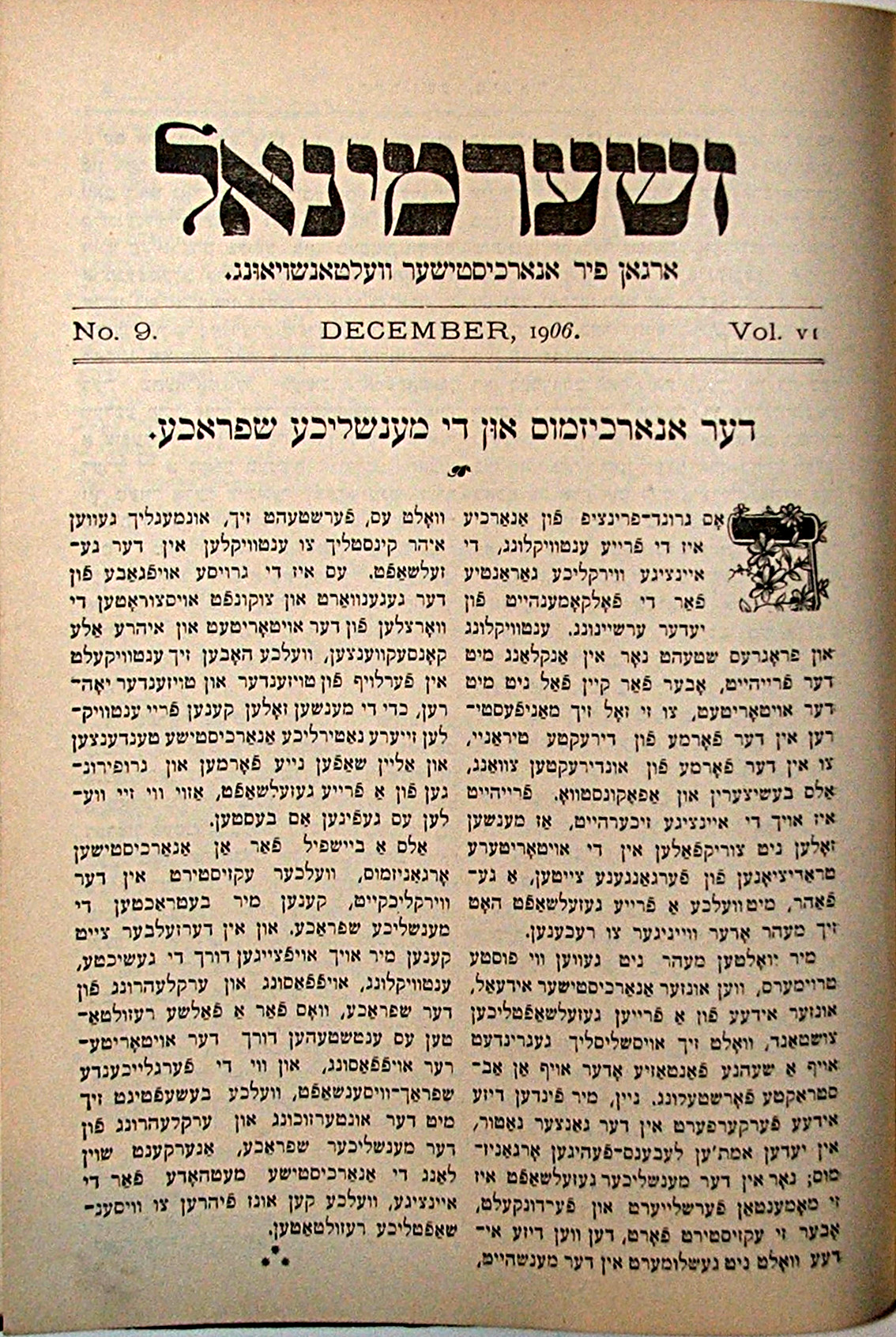

Although it received some funds from Jews in New York, the journal's financial survival was precarious from the start. However, many volunteers helped by selling the paper on street corners and in workshops. During this time, Rocker was especially concerned with combating the influence of  Not wanting to be left without any means of propaganda, Rocker founded the '' Germinal'' in March 1900. Compared to ''Arbeter Fraint'', it was more theoretical, applying anarchist thought to the analysis of literature and philosophy. It represented a maturation of Rocker's thinking towards

Not wanting to be left without any means of propaganda, Rocker founded the '' Germinal'' in March 1900. Compared to ''Arbeter Fraint'', it was more theoretical, applying anarchist thought to the analysis of literature and philosophy. It represented a maturation of Rocker's thinking towards

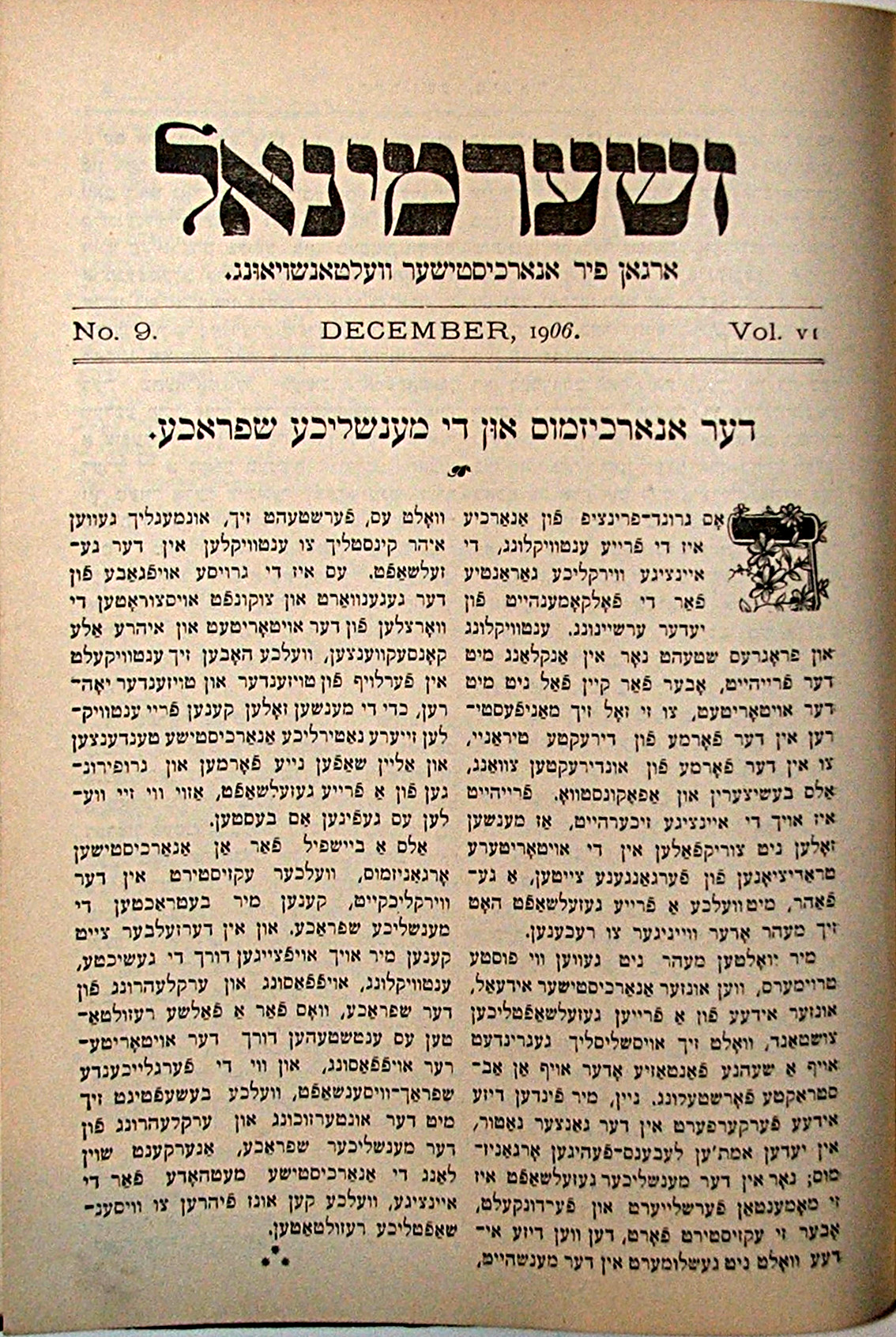

From 1904, the Jewish labor and anarchist movements in London reached their "golden years", according to William J. Fishman. In 1905, publication of ''Germinal'' resumed, it reached a circulation of 2,500 a year later, while ''Arbeter Fraint'' reached a demand of 5,000 copies. In 1906, the ''Arbeter Fraint'' group finally realized a long-time goal, the establishment of a club for both Jewish and gentile workers. The Workers' Friend Club was founded in a former Methodist church on Jubilee Street. Rocker, by now a very eloquent speaker, became a regular speaker. As a result of the popularity of both the club and ''Germinal'' beyond the anarchist scene, Rocker befriended many prominent non-anarchist Jews in London, among them the Zionist philosopher Ber Borochov.

From June 8, 1906, Rocker was involved in a garment workers' strike. Wages and working conditions in the East End were much lower than in the rest of London and tailoring was the most important industry. Rocker was asked by the union leading the strike to become part of the strike committee along with two other ''Arbeter Fraint'' members. He was a regular speaker at the strikers' gatherings. The strike failed, because the strike funds ran out. By July 1, all workers were back in their workshops.

From 1904, the Jewish labor and anarchist movements in London reached their "golden years", according to William J. Fishman. In 1905, publication of ''Germinal'' resumed, it reached a circulation of 2,500 a year later, while ''Arbeter Fraint'' reached a demand of 5,000 copies. In 1906, the ''Arbeter Fraint'' group finally realized a long-time goal, the establishment of a club for both Jewish and gentile workers. The Workers' Friend Club was founded in a former Methodist church on Jubilee Street. Rocker, by now a very eloquent speaker, became a regular speaker. As a result of the popularity of both the club and ''Germinal'' beyond the anarchist scene, Rocker befriended many prominent non-anarchist Jews in London, among them the Zionist philosopher Ber Borochov.

From June 8, 1906, Rocker was involved in a garment workers' strike. Wages and working conditions in the East End were much lower than in the rest of London and tailoring was the most important industry. Rocker was asked by the union leading the strike to become part of the strike committee along with two other ''Arbeter Fraint'' members. He was a regular speaker at the strikers' gatherings. The strike failed, because the strike funds ran out. By July 1, all workers were back in their workshops.

Rocker represented the federation at the International Anarchist Congress in Amsterdam in 1907. Errico Malatesta,

Rocker represented the federation at the International Anarchist Congress in Amsterdam in 1907. Errico Malatesta,

In March 1918, Rocker was taken to the

In March 1918, Rocker was taken to the

In 1931, Rocker attended the IWA congress in Madrid and then the unveiling of the Nieuwenhuis memorial in Amsterdam. In 1933, the Nazis came to power. After the Reichstag fire on February 27, Rocker and Witkop decided to leave Germany. As they left they received news of

In 1931, Rocker attended the IWA congress in Madrid and then the unveiling of the Nieuwenhuis memorial in Amsterdam. In 1933, the Nazis came to power. After the Reichstag fire on February 27, Rocker and Witkop decided to leave Germany. As they left they received news of

Thesis version

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Rudolf Rocker Papers

at the

Profile at the Rudolf Rocker Cultural Center Winnipeg Manitoba

Rudolf Rocker Archive at the Kate Sharpley Library

Rudolf Rocker Archive at libcom.org

Rudolf Rocker page at Anarcho-Syndicalism 101

Rudolf Rocker Texts at Anarchy is Order

* *

at the

Rudolf Rocker's son, Fermin, reminiscing about his father and growing up in London

{{DEFAULTSORT:Rocker, Rudolf 1873 births 1958 deaths American anarchists American male non-fiction writers American political writers Anarchist theorists Anarchist writers Anarchists without adjectives Anarcho-syndicalists British anarchists Emigrants from Nazi Germany to the United States German anarchists German emigrants to England German male non-fiction writers German political writers Jewish English history Libertarian socialists Members of the Free Workers' Union of Germany People from Rhenish Hesse People from Yorktown, New York Scholars of nationalism Writers from Mainz Yiddish-language writers

Mainz

Mainz () is the capital and largest city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Mainz is on the left bank of the Rhine, opposite to the place that the Main joins the Rhine. Downstream of the confluence, the Rhine flows to the north-west, with Ma ...

to a Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

artisan family.

His father died when he was a child, and his mother when he was in his teens, so he spent some time in an orphanage. As a youth he worked as a cabin boy on river boats and was then apprenticed as a typographer

Typography is the art and technique of arranging type to make written language legible, readable and appealing when displayed. The arrangement of type involves selecting typefaces, point sizes, line lengths, line-spacing ( leading), an ...

. He became involved in trade unionism and joined the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) before coming under the influence of anarchists such as Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin (; 1814–1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist, socialist and founder of collectivist anarchism. He is considered among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major founder of the revolutionary s ...

and Peter Kropotkin. With other libertarian youth, he was expelled from the SPD, and his anarchist activism led to him fleeing Germany for Paris, where he came into contact with syndicalist and Jewish anarchist

This is a list of Jewish anarchists.

Individuals

See also

* Jewish anarchism

Notes

References

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Further reading

*

*

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:List Of Jewish Anarchists

Jewish

*

Anarchists

Anarchism is a political ...

ideas and practices. In 1895, he moved to London. Apart from brief spells in Liverpool and elsewhere, he remained in East London for most of the next two decades, acting a key figure in the Yiddish

Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ve ...

-language anarchist scene there, including editing the ''Arbeter Fraynd

The Worker's Friend Group was a Jewish anarchist group active in London's East End in the early 1900s. Associated with the Yiddish-language anarchist newspaper ''Arbeter Fraint'' ("Worker's Friend") and centered around the German emigre anarchi ...

'' periodical, publishing the key thinkers of anarchism, and organising strikes in the garment industry

Clothing industry or garment industry summarizes the types of trade and industry along the production and value chain of clothing and garments, starting with the textile industry (producers of cotton, wool, fur, and synthetic fibre), embellishmen ...

. In London, he formed a life partnership with Milly Witkop

Milly Witkop(-Rocker) (March 3, 1877November 23, 1955) was a Ukrainian-born Jewish anarcho-syndicalist, feminist writer and activist. She was the common-law wife of the prominent anarcho-syndicalist leader Rudolf Rocker. The couple's son, Fermin ...

, a Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

-born anarchist from a Yiddish background. During World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, he was interned as an enemy alien

In customary international law, an enemy alien is any native, citizen, denizen or subject of any foreign nation or government with which a domestic nation or government is in conflict and who is liable to be apprehended, restrained, secured and ...

and at the end the war he was deported to the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

.

In the 1920s, he was mainly based in Germany, where he was one of the architects of the syndicalist Free Workers' Union of Germany

The Free Workers' Union of Germany (; FAUD) was an anarcho-syndicalist trade union in Germany. It stemmed from the Free Association of German Trade Unions (FDVG) which combined with the Ruhr region's Freie Arbeiter Union on September 15, 1919. ...

(FAUD) and its organ ''Der Syndikalist'' and a founder of the International Workers Association

International is an adjective (also used as a noun) meaning "between nations".

International may also refer to:

Music Albums

* ''International'' (Kevin Michael album), 2011

* ''International'' (New Order album), 2002

* ''International'' (The T ...

(IWA). He became increasingly concerned with the rise of nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

and fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy an ...

(he began work on his ''magnum opus

A masterpiece, ''magnum opus'' (), or ''chef-d’œuvre'' (; ; ) in modern use is a creation that has been given much critical praise, especially one that is considered the greatest work of a person's career or a work of outstanding creativity, ...

'' ''Nationalism and Culture

''Nationalism and Culture'' is a nonfiction book by German anarcho-syndicalist writer Rudolf Rocker. In this book, he criticizes religion, statism, nationalism, and centralism from an anarchist perspective.

Background

The ideas expressed in the ...

'' in this period) and left Germany in 1933 for the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

. In the US, he was active with the Yiddish ''Freie Arbeiter Stimme

''Freie Arbeiter Stimme'' ( yi, פֿרייע אַרבעטער שטימע, romanized: ''Fraye arbeṭer shṭime'', ''lit.'' 'Free Voice of Labor') was a Yiddish-language anarchist newspaper published from New York City's Lower East Side between ...

'' group, and was particularly involved in libertarian education and in solidarity with the Spanish Revolution and its fascist and Stalinist enemies. His classics ''Nationalism and Culture'' and ''Anarcho-Syndicalism'' were published in the 1930s. Having opposed both sides in First World War, as an anti-fascist he supported the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

in the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

. After the war, he published '' Pioneers of American Freedom'', a series of essays detailing the history of liberal and anarchist thought in the United States, seeking to debunk the idea that radical thought was foreign to American history and culture and had merely been imported by immigrants.

Early life

Rudolf Rocker was born to thelithographer

Lithography () is a planographic method of printing originally based on the immiscibility of oil and water. The printing is from a stone (lithographic limestone) or a metal plate with a smooth surface. It was invented in 1796 by the German a ...

Georg Philipp Rocker (1845-1877) and his wife Anna Margaretha née Naumann (1869-1887, daughter of Heinrich Naumann) as one of their four children, in Mainz

Mainz () is the capital and largest city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Mainz is on the left bank of the Rhine, opposite to the place that the Main joins the Rhine. Downstream of the confluence, the Rhine flows to the north-west, with Ma ...

, Hesse

Hesse (, , ) or Hessia (, ; german: Hessen ), officially the State of Hessen (german: links=no, Land Hessen), is a state in Germany. Its capital city is Wiesbaden, and the largest urban area is Frankfurt. Two other major historic cities are Dar ...

(now Rhineland-Palatinate

Rhineland-Palatinate ( , ; german: link=no, Rheinland-Pfalz ; lb, Rheinland-Pfalz ; pfl, Rhoilond-Palz) is a western state of Germany. It covers and has about 4.05 million residents. It is the ninth largest and sixth most populous of the ...

), Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, on March 25, 1873. (His siblings were Philipp, 1870–1873; Catharina Barbara, 20 March 1870 – 3 April 1870; and Friedrich, b. 1877). This Catholic, yet not particularly devout, family had a democratic and anti-Prussian

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

tradition dating back to Rocker's grandfather, who participated in the March Revolution of 1848. However, Georg Philipp died in 1877, just four years after Rocker's birth. After that, the family managed to evade poverty primarily through the massive support by his mother's family.

In October 1884, the Rocker household was joined by his mother's new husband Ludwig Baumgartner. This marriage presented Rudolf with a half brother, Ernest Ludwig Heinrich Baumgartner, with whom Rocker did not maintain close contact.

Rocker's mother died in February 1887. After his stepfather remarried soon thereafter, Rocker was put into an orphanage

An orphanage is a residential institution, total institution or group home, devoted to the care of orphans and children who, for various reasons, cannot be cared for by their biological families. The parents may be deceased, absent, or ab ...

.

Rudolf Rocker, disgusted by the unconditional obedience demanded by the Catholic orphanage and drawn by the prospect of adventure, ran away from the orphanage twice. The first time he just wandered around in the woods around Mainz with occasional visits to the city to forage for food and was retrieved after three nights. The second time, which was at the age of fourteen and a reaction to the orphanage wanting him to be apprenticed as a tinsmith

A tinsmith is a person who makes and repairs things made of tin or other light metals. The profession may sometimes also be known as a tinner, tinker, tinman, or tinplate worker; whitesmith may also refer to this profession, though the same w ...

, he worked as a cabin-boy for Köln-Düsseldorfer Dampfschiffahrtsgesellschaft. He enjoyed leaving his hometown and traveling to places like Rotterdam

Rotterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Rotte'') is the second largest city and municipality in the Netherlands. It is in the province of South Holland, part of the North Sea mouth of the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta, via the ''"Ne ...

. After he returned, he started an apprenticeship to become a typographer like his uncle Carl.

Early politics

Rocker's uncle, Carl Rudolf Naumann, had a substantial library consisting of socialist literature of all colors. Rocker was particularly impressed by the writings of Constantin Frantz, a federalist and opponent of Bismarck's centralized German Empire;Eugen Dühring

Eugen Karl Dühring (12 January 1833, Berlin21 September 1921, Nowawes in modern-day Potsdam-Babelsberg) was a German philosopher, positivist, economist, and socialist who was a strong critic of Marxism.

Life and works

Dühring was born in Be ...

, an anti- Marxist socialist, whose theories had some anarchist aspects; novels like Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romantic writer and politician. During a literary career that spanned more than sixty years, he wrote in a variety of genres and forms. He is considered to be one of the great ...

's ''Les Misérables

''Les Misérables'' ( , ) is a French historical novel by Victor Hugo, first published in 1862, that is considered one of the greatest novels of the 19th century.

In the English-speaking world, the novel is usually referred to by its origin ...

'' and Edward Bellamy

Edward Bellamy (March 26, 1850 – May 22, 1898) was an American author, journalist, and political activist most famous for his utopian novel ''Looking Backward''. Bellamy's vision of a harmonious future world inspired the formation of numerou ...

's ''Looking Backward

''Looking Backward: 2000–1887'' is a utopian science fiction novel by Edward Bellamy, a journalist and writer from Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts; it was first published in 1888.

The book was translated into several languages, and in short o ...

''; as well as the traditional socialist literature such as Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

's '' Capital'' and Ferdinand Lasalle and August Bebel's writings. Rocker became a socialist and regularly discussed his ideas with others. His employer became the first person he converted to socialism.

Under the influence of his uncle, he joined the SPD and became active in the typographers' labor union in Mainz. He volunteered in the 1890 electoral campaign, which had to be organized in semi-clandestinity because of continuing government repression, helping the SPD candidate retake the seat for the district Mainz-Oppenheim

Oppenheim () is a town in the Mainz-Bingen district of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. The town is a well-known wine center, being the home of the German Winegrowing Museum, and is particularly known for the wines from the Oppenheimer Krötenbru ...

in the '' Reichstag''. Because the seat was heavily contested, important SPD figures like August Bebel, Wilhelm Liebknecht

Wilhelm Martin Philipp Christian Ludwig Liebknecht (; 29 March 1826 – 7 August 1900) was a German socialist and one of the principal founders of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD).Georg von Vollmar

Georg Heinrich Ritter (Chevalier) von Vollmar auf Veldheim (March 7, 1850 – June 30, 1922) was a democratic socialist politician from Bavaria.

Biography

Vollmar was born in Munich, and educated in a school attached to a Benedictine monastery at ...

, and Paul Singer visited the town to help Jöst and Rocker had a chance to see them speak.

In 1890, there was a major debate in the SPD about the tactics it would choose after the lifting of the Anti-Socialist Laws

The Anti-Socialist Laws or Socialist Laws (german: Sozialistengesetze; officially , approximately "Law against the public danger of Social Democratic endeavours") were a series of acts of the parliament of the German Empire, the first of which was ...

. A radical oppositional wing known as ''Die Jungen'' (''The Young Ones'') developed. While the party leaders viewed the parliament as a means of social change, ''Die Jungen'' thought it could at best be used to spread the socialist message. Unwilling to wait for the collapse of capitalist society which Marxism

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialectical ...

predicted, they wanted to start a revolution as soon as possible. Although this wing was strongest in Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and List of cities in Germany by population, largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European Union by population within ci ...

, Magdeburg

Magdeburg (; nds, label=Low Saxon, Meideborg ) is the capital and second-largest city of the German state Saxony-Anhalt. The city is situated at the Elbe river.

Otto I, the first Holy Roman Emperor and founder of the Archdiocese of Magdebu ...

, and Dresden

Dresden (, ; Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; wen, label= Upper Sorbian, Drježdźany) is the capital city of the German state of Saxony and its second most populous city, after Leipzig. It is the 12th most populous city of Germany, the fourth ...

, it also had a few adherents in Mainz, among them Rudolf Rocker.

In May 1890, he started a reading circle, named ''Freiheit'' (''Freedom''), to study theoretical topics more intensively. After Rocker criticized Jöst and refused to retract his statements, he was expelled from the party. Nonetheless, he remained active and even gained influence in the socialist labor movement in Mainz. Although he had already encountered anarchist ideas as a result of his contacts to ''Die Jungen'' in Berlin, his conversion to anarchism did not take place until the International Socialist Congress in Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

in August 1891. He was heavily disappointed by the discussions at the congress, as it, especially the German delegates, refused to explicitly denounce militarism

Militarism is the belief or the desire of a government or a people that a state should maintain a strong military capability and to use it aggressively to expand national interests and/or values. It may also imply the glorification of the mili ...

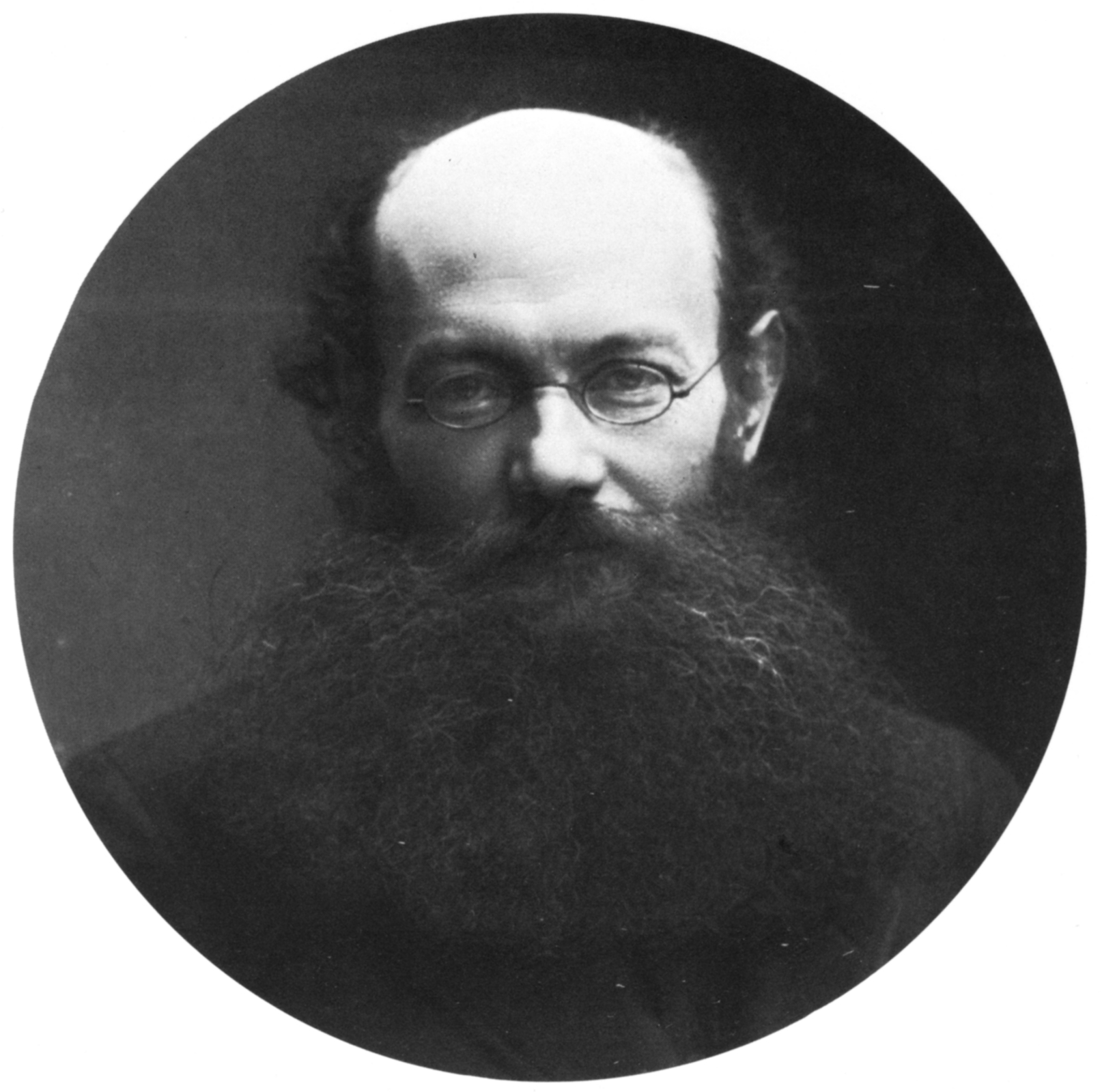

. He was rather impressed by the Dutch socialist and later anarchist Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis

Ferdinand Jacobus Domela Nieuwenhuis (31 December 1846 – 18 November 1919) was a Dutch socialist politician and later a social anarchist and anti-militarist. He was a Lutheran preacher who, after he lost his faith, started a political fight ...

, who attacked Liebknecht for his lack of militancy. Rocker got to know Karl Höfer, a German active in smuggling anarchist literature from Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

to Germany. Höfer gave him Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin (; 1814–1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist, socialist and founder of collectivist anarchism. He is considered among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major founder of the revolutionary s ...

's ''God and the State

''God and the State'' (called by its author ''The Historical Sophisms of the Doctrinaire School of Communism'') is an unfinished manuscript by the Russian anarchist philosopher Mikhail Bakunin, published posthumously in 1882. The work criticises ...

'' and Peter Kropotkin's ''Anarchist Morality'', two of the most influential anarchist works, as well as the newspaper ''Autonomie''.

Rocker maintained that political rights originated towards the individual, rather than government as the collective that maintained personal freedoms. This view would later influence him into becoming an anarchist. Rudolf wrote on political rights:

Rocker became convinced that the source of political institutions is an irrational belief in a higher authority, as Bakunin claimed in ''God and the State''. However, Rocker rejected the Russian's rejection of theoretical propaganda and his claim that only

Rocker became convinced that the source of political institutions is an irrational belief in a higher authority, as Bakunin claimed in ''God and the State''. However, Rocker rejected the Russian's rejection of theoretical propaganda and his claim that only revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

s can bring about change. Nevertheless, he was very much attracted by Bakunin's style, marked by pathos, emotion, and enthusiasm, designed to give the reader an impression of the heat of revolutionary moments. Rocker even attempted to emulate this style in his speeches, but was not very convincing. Kropotkin's anarcho-communist

Anarcho-communism, also known as anarchist communism, (or, colloquially, ''ancom'' or ''ancomm'') is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private property but retains resp ...

writings, on the other hand, were structured logically and contained an elaborate description of the future anarchist society. The work's basic premise, that an individual is entitled to receive the basic means of living from the community independently of his or her personal contributions, impressed Rocker.

In October 1891, all ''Die Jungen'' were either expelled from the SPD or left voluntarily. They then founded the Union of Independent Socialists (VUS). Rocker became a member and founded a local section in Mainz, mostly active in distributing anarchist literature smuggled in from Belgium or the Netherlands in the city. He was a regular speaker at labor union meetings. On December 18, 1892, he spoke at a meeting of unemployed workers. Impressed by Rocker's speech, the speaker that followed Rocker, who was not from Mainz and therefore did not know at what point the police would intervene, advised the unemployed to take from the rich, rather to starve. The meeting was then dissolved by the police. The speaker was arrested, while Rocker barely escaped. He decided to flee Germany to Paris via Frankfurt

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian: , " Frank ford on the Main"), is the most populous city in the German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located on it ...

. He had, however, already been toying with the idea of leaving the country, in order to learn new languages, get to know anarchist groups abroad, and, above all, to escape conscription.

Paris

In Paris, he first came into contact with

In Paris, he first came into contact with Jewish anarchism

Jewish anarchism encompasses various expressions of anarchism within the Jewish community.

Secular Jewish anarchism

Many people of Jewish origin, such as Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman, Paul Goodman, Murray Bookchin, Volin, Gustav Landauer ...

. In Spring 1893, he was invited to meeting of Jewish anarchists, which he attended and was impressed by. Though neither a Jew by birth nor by belief, he ended up frequenting the group's meeting, eventually holding lectures himself. Solomon Rappaport, later known as S. Ansky, allowed Rocker to live with him, as they were both typographers and could share Rappaport's tools. During this period, Rocker also first came into contact with the blending of anarchist and syndicalist ideas represented by the General Confederation of Labor (CGT), which would influence him in the long term. In 1895, as a result of the anti-anarchist sentiment in France, Rocker traveled to London to visit the German consulate and examine the possibility of his returning to Germany but was told he would be imprisoned upon return.

London

First years in London

Rocker decided to stay in London. He got a job as the librarian of the Communist Workers' Educational Union, where he got to knowLouise Michel

Louise Michel (; 29 May 1830 – 9 January 1905) was a teacher and important figure in the Paris Commune. Following her penal transportation to New Caledonia she embraced anarchism. When returning to France she emerged as an important French a ...

and Errico Malatesta, two influential anarchists. Inspired to visit the quarter after reading about "Darkest London" in the works of John Henry Mackay

John Henry Mackay, also known by the pseudonym Sagitta, (6 February 1864 – 16 May 1933) was an egoist anarchist, thinker and writer. Born in Scotland and raised in Germany, Mackay was the author of '' Die Anarchisten'' (The Anarchists, 1891) a ...

, he was appalled by the poverty he witnessed in the predominantly Jewish East End. He joined the Jewish anarchist '' Arbeter Fraint'' group he had obtained information about from his French comrades, quickly becoming a regular lecturer at its meetings. There, he met his lifelong companion Milly Witkop

Milly Witkop(-Rocker) (March 3, 1877November 23, 1955) was a Ukrainian-born Jewish anarcho-syndicalist, feminist writer and activist. She was the common-law wife of the prominent anarcho-syndicalist leader Rudolf Rocker. The couple's son, Fermin ...

, a Ukrainian-born Jew who had fled to London in 1894. In May 1897, having lost his job and with little chance of re-employment, Rocker was persuaded by a friend to move to New York. Witkop agreed to accompany him and they arrived on the 29th. They were, however, not admitted into the country, because they were not legally married. They refused to formalize their relationship. Rocker explained that their "bond is one of free agreement between my wife and myself. It is a purely private matter that only concerns ourselves, and it needs no confirmation from the law." Witkop added: "Love is always free. When love ceases to be free it is prostitution." The matter received front-page coverage in the national press. The Commissioner-General of Immigration, the former Knights of Labor

Knights of Labor (K of L), officially Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, was an American labor federation active in the late 19th century, especially the 1880s. It operated in the United States as well in Canada, and had chapters also ...

President Terence V. Powderly

Terence Vincent Powderly (January 22, 1849 – June 24, 1924) was an American labor union leader, politician and attorney, best known as head of the Knights of Labor in the late 1880s. Born in Carbondale, Pennsylvania, he was later elected mayor ...

, advised the couple to marry to settle the matter, but they refused and were deported back to England on the same ship they had arrived on.

Unable to find employment upon return, Rocker decided to move to Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a populat ...

. A former Whitechapel comrade of his persuaded him to become the editor of a recently founded Yiddish

Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ve ...

weekly newspaper called '' Dos Fraye Vort'' (''The Free Word''), even though he did not speak the language at the time. The newspaper only appeared for eight issues, but it led the ''Arbeter Fraint'' group to re-launch its eponymous newspaper and invite Rocker to return to the capital and take over as its editor.

Although it received some funds from Jews in New York, the journal's financial survival was precarious from the start. However, many volunteers helped by selling the paper on street corners and in workshops. During this time, Rocker was especially concerned with combating the influence of

Although it received some funds from Jews in New York, the journal's financial survival was precarious from the start. However, many volunteers helped by selling the paper on street corners and in workshops. During this time, Rocker was especially concerned with combating the influence of Marxism

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialectical ...

and historical materialism

Historical materialism is the term used to describe Karl Marx's theory of history. Marx locates historical change in the rise of class societies and the way humans labor together to make their livelihoods. For Marx and his lifetime collaborat ...

in London's Jewish labor movement. In all, the ''Arbeter Fraint'' published twenty-five essays by Rocker on the topic, the first ever critical examination of Marxism in Yiddish, according to William J. Fishman. ''Arbeter Fraint''s unsound financial footing also meant Rocker rarely received the small salary promised to him when he took over the journal and he depended financially on Witkop. Despite Rocker's sacrifices, however, the paper was forced to cease publication for lack of funds. In November 1899, the prominent American anarchist Emma Goldman visited London and Rocker met her for the first time. After hearing of the ''Arbeter Fraint''s situation she held three lectures to raise funds, but that was not enough.

Not wanting to be left without any means of propaganda, Rocker founded the '' Germinal'' in March 1900. Compared to ''Arbeter Fraint'', it was more theoretical, applying anarchist thought to the analysis of literature and philosophy. It represented a maturation of Rocker's thinking towards

Not wanting to be left without any means of propaganda, Rocker founded the '' Germinal'' in March 1900. Compared to ''Arbeter Fraint'', it was more theoretical, applying anarchist thought to the analysis of literature and philosophy. It represented a maturation of Rocker's thinking towards Kropotkin

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (; russian: link=no, Пётр Алексе́евич Кропо́ткин ; 9 December 1842 – 8 February 1921) was a Russian anarchist, socialist, revolutionary, historian, scientist, philosopher, and activist ...

-ite anarchism and would survive until March 1903. 1902 saw the London Jews being targeted by a wave of anti-alien sentiment, while Rocker was away for a year in Leeds

Leeds () is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds district in West Yorkshire, England. It is built around the River Aire and is in the eastern foothills of the Pennines. It is also the third-largest settlement (by popula ...

. Upon return in September, he was happy to see the Jewish anarchists had kept the ''Arbeter Fraint'' organization alive. A conference of all Jewish anarchists of the city on December 26 decided for a re-launch of the ''Arbeter Fraint'' newspaper as the organ of all Jewish anarchists in Great Britain and Paris and made Rocker the editor. The first issue appeared on March 20, 1903. Following the Kishinev pogrom

The Kishinev pogrom or Kishinev massacre was an anti-Jewish riot that took place in Kishinev (modern Chișinău, Moldova), then the capital of the Bessarabia Governorate in the Russian Empire, on . A second pogrom erupted in the city in Octob ...

in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

, Rocker led a demonstration in solidarity with the victims, the largest ever gathering of Jews in London. Afterwards he traveled to Leeds, Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

, and Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian on the southern shore of t ...

to lecture on the topic.

Jewish anarchism's golden years

From 1904, the Jewish labor and anarchist movements in London reached their "golden years", according to William J. Fishman. In 1905, publication of ''Germinal'' resumed, it reached a circulation of 2,500 a year later, while ''Arbeter Fraint'' reached a demand of 5,000 copies. In 1906, the ''Arbeter Fraint'' group finally realized a long-time goal, the establishment of a club for both Jewish and gentile workers. The Workers' Friend Club was founded in a former Methodist church on Jubilee Street. Rocker, by now a very eloquent speaker, became a regular speaker. As a result of the popularity of both the club and ''Germinal'' beyond the anarchist scene, Rocker befriended many prominent non-anarchist Jews in London, among them the Zionist philosopher Ber Borochov.

From June 8, 1906, Rocker was involved in a garment workers' strike. Wages and working conditions in the East End were much lower than in the rest of London and tailoring was the most important industry. Rocker was asked by the union leading the strike to become part of the strike committee along with two other ''Arbeter Fraint'' members. He was a regular speaker at the strikers' gatherings. The strike failed, because the strike funds ran out. By July 1, all workers were back in their workshops.

From 1904, the Jewish labor and anarchist movements in London reached their "golden years", according to William J. Fishman. In 1905, publication of ''Germinal'' resumed, it reached a circulation of 2,500 a year later, while ''Arbeter Fraint'' reached a demand of 5,000 copies. In 1906, the ''Arbeter Fraint'' group finally realized a long-time goal, the establishment of a club for both Jewish and gentile workers. The Workers' Friend Club was founded in a former Methodist church on Jubilee Street. Rocker, by now a very eloquent speaker, became a regular speaker. As a result of the popularity of both the club and ''Germinal'' beyond the anarchist scene, Rocker befriended many prominent non-anarchist Jews in London, among them the Zionist philosopher Ber Borochov.

From June 8, 1906, Rocker was involved in a garment workers' strike. Wages and working conditions in the East End were much lower than in the rest of London and tailoring was the most important industry. Rocker was asked by the union leading the strike to become part of the strike committee along with two other ''Arbeter Fraint'' members. He was a regular speaker at the strikers' gatherings. The strike failed, because the strike funds ran out. By July 1, all workers were back in their workshops.

Rocker represented the federation at the International Anarchist Congress in Amsterdam in 1907. Errico Malatesta,

Rocker represented the federation at the International Anarchist Congress in Amsterdam in 1907. Errico Malatesta, Alexander Schapiro

Alexander "Sanya" Moiseyevich Schapiro or Shapiro (in Russian: Александр "Саня" Моисеевич Шапиро; 1882 or 1883 – December 5, 1946) was a Russian anarcho-syndicalist activist. Born in southern Russia, Schapiro ...

, and he became the secretaries of the new Anarchist International, but it only lasted until 1911. Also in 1907, his son Fermin

Fermin (also Firmin, from Latin ''Firminus''; Spanish ''Fermín'') was a legendary holy man and martyr, traditionally venerated as the co-patron saint of Navarre, Spain. His death may be associated with either the Decian persecution (250) or Dio ...

was born. In 1909, while visiting France, Rocker denounced the execution of the anarchist pedagogue Francisco Ferrer

Francesc Ferrer i Guàrdia (; January 14, 1859 – October 13, 1909), widely known as Francisco Ferrer (), was a Spanish radical freethinker, anarchist, and educationist behind a network of secular, private, libertarian schools in and aroun ...

in Barcelona, leading him to be deported back to England.

In 1912, Rocker was once again an important figure in a strike by London's garment makers. In late April, 1,500 tailors from the West End, who were more highly skilled and better-paid than those in the East End, started striking. By May, the total number was between 7,000 and 8,000. Since much of the West Enders' work was now being performed in the East End, the tailors' union there, under the influence of the ''Arbeter Fraint'' group, decided to support the strike. Rudolf Rocker on the one hand saw this as a chance for the East End tailors to attack the sweatshop system, but on the other was afraid of an anti-Semitic backlash, should the Jewish workers remain idle. He called for a general strike. His call was not followed, since over seventy percent of the East End tailors were engaged in the ready-made trade, which was not linked with the West End workers' strike. Nonetheless, 13,000 immigrant garment workers from the East End went on strike following a May 8 assembly at which Rocker spoke. Not one worker voted against a strike. Rocker became a member of the strike committee and chairman of the finance sub-committee. He was responsible for collecting money and other necessities for the striking workers. On the side he published the ''Arbeter Fraint'' newspaper on a daily basis to disseminate news about the strike. He spoke at the workers' assemblies and demonstrations. On May 24 a mass meeting was held to discuss the question of whether to settle on a compromise proposed by the employers, which did not entail a closed union shop

In labor law, a union shop, also known as a post-entry closed shop, is a form of a union security clause. Under this, the employer agrees to either only hire labor union members or to require that any new employees who are not already union me ...

. A speech by Rocker convinced the workers to continue the strike. By the next morning, all of the workers' demands were met.

World War I

Rocker opposed both sides inWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

on internationalist

Internationalist may refer to:

* Internationalism (politics), a movement to increase cooperation across national borders

* Liberal internationalism, a doctrine in international relations

* Internationalist/Defencist Schism, socialists opposed to ...

grounds. Although most in the United Kingdom and continental Europe expected a short war, Rocker predicted on August 7, 1914 "a period of mass murder such as the world has never known before" and attacked the Second International

The Second International (1889–1916) was an organisation of socialist and labour parties, formed on 14 July 1889 at two simultaneous Paris meetings in which delegations from twenty countries participated. The Second International continued th ...

for not opposing the conflict. Rocker with some other ''Arbeter Fraint'' members opened up a soup kitchen without fixed prices to alleviate the further impoverishment that came with the Great War. There was a debate between Kropotkin, who supported the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

, and Rocker in ''Arbeter Fraint'' in October and November. He called the war "the contradiction of everything we had fought for".

Shortly after the publication of this statement, on December 2, Rocker was arrested and interned as an enemy alien

In customary international law, an enemy alien is any native, citizen, denizen or subject of any foreign nation or government with which a domestic nation or government is in conflict and who is liable to be apprehended, restrained, secured and ...

. This was also the result of the anti-German sentiment

Anti-German sentiment (also known as Anti-Germanism, Germanophobia or Teutophobia) is opposition to or fear of Germany, its inhabitants, its culture, or its language. Its opposite is Germanophilia.

Anti-German sentiment largely began wit ...

in the country. ''Arbeiter Fraynd'' was suppressed in 1915. The Jewish anarchist movement in Britain never fully recovered from these blows.

Return to Germany

FVdG

In March 1918, Rocker was taken to the

In March 1918, Rocker was taken to the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

under an agreement to exchange prisoners through the Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure respect for all human beings, and ...

. He stayed at the house of the socialist leader Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis

Ferdinand Jacobus Domela Nieuwenhuis (31 December 1846 – 18 November 1919) was a Dutch socialist politician and later a social anarchist and anti-militarist. He was a Lutheran preacher who, after he lost his faith, started a political fight ...

and he recovered from the health problems from which he suffered as a result of his internment in the UK and met up with his wife Milly Witkop

Milly Witkop(-Rocker) (March 3, 1877November 23, 1955) was a Ukrainian-born Jewish anarcho-syndicalist, feminist writer and activist. She was the common-law wife of the prominent anarcho-syndicalist leader Rudolf Rocker. The couple's son, Fermin ...

and his son Fermin

Fermin (also Firmin, from Latin ''Firminus''; Spanish ''Fermín'') was a legendary holy man and martyr, traditionally venerated as the co-patron saint of Navarre, Spain. His death may be associated with either the Decian persecution (250) or Dio ...

. He returned to Germany in November 1918 upon an invitation from Fritz Kater

Fritz Kater (12 December 1861 – 20 May 1945) was a German trade unionist active in the Free Association of German Trade Unions (FVdG) and its successor organization, the Free Workers' Union of Germany. He was the editor of the FVdG's organ ...

to join him in Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and List of cities in Germany by population, largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European Union by population within ci ...

to re-build the Free Association of German Trade Unions

The Free Association of German Trade Unions (; abbreviated FVdG; sometimes also translated as Free Association of German Unions or Free Alliance of German Trade Unions) was a trade union federation in Imperial and early Weimar Germany. It was fou ...

(FVdG). The FVdG was a radical labor federation that quit the SPD in 1908 and became increasingly syndicalist and anarchist. During World War I, it had been unable to continue its activities for fear of government repression, but remained in existence as an underground organization.

Rocker was opposed to the FVdG's alliance with the communists during and immediately after the November Revolution, as he rejected Marxism, especially the concept of the dictatorship of the proletariat

In Marxist philosophy, the dictatorship of the proletariat is a condition in which the proletariat holds state power. The dictatorship of the proletariat is the intermediate stage between a capitalist economy and a communist economy, whereby the ...

. Soon after arriving in Germany, however, he once again became seriously ill. He started giving public speeches in March 1919, including one at a congress of munitions workers in Erfurt

Erfurt () is the capital and largest city in the Central German state of Thuringia. It is located in the wide valley of the Gera river (progression: ), in the southern part of the Thuringian Basin, north of the Thuringian Forest. It sits i ...

, where he urged them to stop producing war material. During this period the FVdG grew rapidly and the coalition with the communists soon began to crumble. Eventually all syndicalist members of the Communist Party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of ''The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. ...

were expelled. From December 27 to December 30, 1919, the twelfth national congress of the FVdG was held in Berlin.

The organization decided to become the Free Workers' Union of Germany

The Free Workers' Union of Germany (; FAUD) was an anarcho-syndicalist trade union in Germany. It stemmed from the Free Association of German Trade Unions (FDVG) which combined with the Ruhr region's Freie Arbeiter Union on September 15, 1919. ...

(FAUD) under a new platform, which had been written by Rocker: the ''Prinzipienerklärung des Syndikalismus'' (''Declaration of Syndicalist Principles''). It rejected political parties and the dictatorship of the proletariat as bourgeois concepts. The program recognized only decentralized, purely economic, organizations. Although public ownership of land, means of production, and raw materials was advocated, nationalization and the idea of a communist state were rejected. Rocker decried nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

as the religion of the modern state and opposed violence, championing instead direct action and the education of the workers.

Heyday of syndicalism

OnGustav Landauer

Gustav Landauer (7 April 1870 – 2 May 1919) was one of the leading theorists on anarchism in Germany at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. He was an advocate of social anarchism and an avowed pacifist.

In 1919, he ...

's death during the Munich Soviet Republic

The Bavarian Soviet Republic, or Munich Soviet Republic (german: Räterepublik Baiern, Münchner Räterepublik),Hollander, Neil (2013) ''Elusive Dove: The Search for Peace During World War I''. McFarland. p.283, note 269. was a short-lived unre ...

uprising, Rocker took over the work of editing the German publications of Kropotkin's writings. In 1920, the social democratic Defense Minister

A defence minister or minister of defence is a cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from country to country; in s ...

Gustav Noske

Gustav Noske (9 July 1868 – 30 November 1946) was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party (SPD). He served as the first Minister of Defence (''Reichswehrminister'') of the Weimar Republic between 1919 and 1920. Noske has been a cont ...

started the suppression of the revolutionary left, which led to the imprisonment of Rocker and Fritz Kater. During their mutual detainment, Rocker convinced Kater, who had still held some social democratic ideals, completely of anarchism.

In the following years, Rocker became one of the most regular writers in the FAUD organ '' Der Syndikalist''. In 1920, the FAUD hosted an international syndicalist conference, which ultimately led to the founding of the International Workers Association

International is an adjective (also used as a noun) meaning "between nations".

International may also refer to:

Music Albums

* ''International'' (Kevin Michael album), 2011

* ''International'' (New Order album), 2002

* ''International'' (The T ...

(IWA) in December 1922. Augustin Souchy

Augustin Souchy Bauer (28 August 1892 – 1 January 1984) was a German anarchist, antimilitarist, labor union official and journalist. He traveled widely and wrote extensively about the Spanish Civil War and intentional communities. He was ...

, Alexander Schapiro

Alexander "Sanya" Moiseyevich Schapiro or Shapiro (in Russian: Александр "Саня" Моисеевич Шапиро; 1882 or 1883 – December 5, 1946) was a Russian anarcho-syndicalist activist. Born in southern Russia, Schapiro ...

, and Rocker became the organization's secretaries and Rocker wrote its platform. In 1921, he wrote the pamphlet ''Der Bankrott des russischen Staatskommunismus'' (''The Bankruptcy of Russian State Communism'') attacking the Soviet Union. He denounced what he considered a massive oppression of individual freedoms and the suppression of anarchists starting with the purge on April 12, 1918. He supported instead the workers who took part in the Kronstadt uprising and the peasant movement led by the anarchist Nestor Makhno

Nestor Ivanovych Makhno, The surname "Makhno" ( uk, Махно́) was itself a corruption of Nestor's father's surname "Mikhnenko" ( uk, Міхненко). ( 1888 – 25 July 1934), also known as Bat'ko Makhno ("Father Makhno"),; According to ...

, whom he would meet in Berlin in 1923. In 1924, Rocker published a biography of Johann Most

Johann Joseph "Hans" Most (February 5, 1846 – March 17, 1906) was a German-American Social Democratic and then anarchist politician, newspaper editor, and orator. He is credited with popularizing the concept of "propaganda of the deed". His g ...

called ''Das Leben eines Rebellen'' (''The Life of a Rebel''). There are great similarities between the men's vitas. It was Rocker who convinced the anarchist historian Max Nettlau to start publication of his anthology ''Geschichte der Anarchie'' (''History of Anarchy'') in 1925.

Decline of syndicalism

During the mid-1920s, the decline of Germany's syndicalist movement started. The FAUD had reached its peak of around 150,000 members in 1921, but then started losing members to both the Communist and theSocial Democratic Party

The name Social Democratic Party or Social Democrats has been used by many political parties in various countries around the world. Such parties are most commonly aligned to social democracy as their political ideology.

Active parties

Fo ...

. Rocker attributed this loss of membership to the mentality of German workers accustomed to military discipline, accusing the communists of using similar tactics to the Nazis and thus attracting such workers. At first only planning a short book on nationalism, he started work on ''Nationalism and Culture

''Nationalism and Culture'' is a nonfiction book by German anarcho-syndicalist writer Rudolf Rocker. In this book, he criticizes religion, statism, nationalism, and centralism from an anarchist perspective.

Background

The ideas expressed in the ...

'', which would be published in 1937 and become one of Rocker's best-known works, around 1925. 1925 also saw Rocker visit North America on a lecture tour with a total of 162 appearances. He was encouraged by the anarcho-syndicalist movement he found in the US and Canada.

Returning to Germany in May 1926, he became increasingly worried about the rise of nationalism and fascism. He wrote to Nettlau in 1927: "Every nationalism begins with a Mazzini

Giuseppe Mazzini (, , ; 22 June 1805 – 10 March 1872) was an Italian politician, journalist, and activist for the unification of Italy (Risorgimento) and spearhead of the Italian revolutionary movement. His efforts helped bring about the in ...

, but in its shadow there lurks a Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

". In 1929, Rocker was a co-founder of the ''Gilde freiheitlicher Bücherfreunde'' (Guild of Libertarian Bibliophiles), a publishing house which would release works by Alexander Berkman

Alexander Berkman (November 21, 1870June 28, 1936) was a Russian-American anarchist and author. He was a leading member of the anarchist movement in the early 20th century, famous for both his political activism and his writing.

Be ...

, William Godwin, Erich Mühsam

Erich Mühsam (6 April 1878 – 10 July 1934) was a German-Jewish antimilitarist anarchist essayist, poet and playwright. He emerged at the end of World War I as one of the leading agitators for a federated Bavarian Soviet Republic, for which h ...

, and John Henry Mackay

John Henry Mackay, also known by the pseudonym Sagitta, (6 February 1864 – 16 May 1933) was an egoist anarchist, thinker and writer. Born in Scotland and raised in Germany, Mackay was the author of '' Die Anarchisten'' (The Anarchists, 1891) a ...

. In the same year he went on a lecture tour in Scandinavia and was impressed by the anarcho-syndicalists there. Upon return, he wondered whether Germans were even capable of anarchist thought. In the 1930 elections

The following elections occurred in the year 1930.

Asia

* 1930 Persian legislative election

* 1930 Madras Presidency legislative council election

* 1930 Japanese general election

Europe

* 1930 Finnish parliamentary election

* 1930 Norwegian parl ...

, the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

received 18.3% of all votes, a total of 6 million. Rocker was worried: "Once the Nazis get to power, we'll all go the way of Landauer and Eisner" (who had been killed by reactionaries in the course of the Munich Soviet Republic uprising).

In 1931, Rocker attended the IWA congress in Madrid and then the unveiling of the Nieuwenhuis memorial in Amsterdam. In 1933, the Nazis came to power. After the Reichstag fire on February 27, Rocker and Witkop decided to leave Germany. As they left they received news of

In 1931, Rocker attended the IWA congress in Madrid and then the unveiling of the Nieuwenhuis memorial in Amsterdam. In 1933, the Nazis came to power. After the Reichstag fire on February 27, Rocker and Witkop decided to leave Germany. As they left they received news of Erich Mühsam

Erich Mühsam (6 April 1878 – 10 July 1934) was a German-Jewish antimilitarist anarchist essayist, poet and playwright. He emerged at the end of World War I as one of the leading agitators for a federated Bavarian Soviet Republic, for which h ...

's arrest. After his death in July 1934, Rocker would write a pamphlet called ''Der Leidensweg Erich Mühsams'' (''The Life and Suffering of Erich Mühsam'') about the anarchist's fate. Rocker reached Basel, Switzerland on March 8 by the last train to cross the border without being searched. Two weeks later, Rocker and his wife joined Emma Goldman in St. Tropez, France. There he wrote ''Der Weg ins Dritte Reich'' (''The Path to the Third Reich'') about the events in Germany, but it would only be published in Spanish.

In May, Rocker and Witkop moved back to London. Rocker was welcomed there by many of the Jewish anarchists he had lived and fought alongside for many years. He held lectures all over the city. In July, he attended an extraordinary IWA meeting in Paris, which decided to smuggle its organ ''Die Internationale

Die, as a verb, refers to death, the cessation of life.

Die may also refer to:

Games

* Die, singular of dice, small throwable objects used for producing random numbers

Manufacturing

* Die (integrated circuit), a rectangular piece of a semicondu ...

'' into Nazi Germany.

United States

First years

On August 26, 1933, Rocker with his wife emigrated to New York. There they were reunited with Fermin who had stayed there after accompanying his father on his 1929 lecture tour in the US. The Rocker family moved to live with a sister of Witkop's in Towanda,Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

where many families with progressive or libertarian socialist views lived. In October, Rocker toured the US and Canada speaking about racism, fascism, dictatorship, socialism in English, Yiddish, and German. He found many of his Jewish comrades from London, who had since emigrated to America, and became a regular writer for ''Freie Arbeiter Stimme

''Freie Arbeiter Stimme'' ( yi, פֿרייע אַרבעטער שטימע, romanized: ''Fraye arbeṭer shṭime'', ''lit.'' 'Free Voice of Labor') was a Yiddish-language anarchist newspaper published from New York City's Lower East Side between ...

'', a Jewish anarchist newspaper. Back in Towanda, in the summer of 1934, Rocker started work on an autobiography, but news of Erich Mühsam's death led him to halt his work. He was working on ''Nationalism and Culture'', when the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, link ...

broke out in July 1936 instilling great optimism in Rocker. He published a pamphlet ''The Truth about Spain'' and contributed to ''The Spanish Revolution'', a special fortnightly newspaper published by American anarchists to report on the events in Spain. In 1937, he wrote ''The Tragedy of Spain'', which analyzed the events in greater detail. In September 1937, Rocker and Witkop moved to the libertarian commune Mohegan

The Mohegan are an Algonquian Native American tribe historically based in present-day Connecticut. Today the majority of the people are associated with the Mohegan Indian Tribe, a federally recognized tribe living on a reservation in the east ...

Colony about from New York City.

''Nationalism and Culture'' and ''Anarcho-Syndicalism''

In 1937, ''Nationalism and Culture'', which he had started work on around 1925, was finally published with the help of anarchists from Chicago Rocker had met in 1933. A Spanish edition was released in three volumes inBarcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within ci ...

, the stronghold of the Spanish anarchists. It would be his best-known work. In the book, Rocker traces the origins of the state back to religion claiming "that all politics is in the last instance religion": both enslave their very creator, man; both claim to be the source of cultural progress. He aims to prove the claim that culture and power are essentially antagonistic concepts. He applies this model to human history, analyzing the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

, the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (800 BC to AD ...

, Enlightenment, and modern capitalist society, and to the history of the socialist movement. He concludes by advocating a "new humanitarian socialism".

In 1938, Rocker published a history of anarchist thought, which he traced all the way back to ancient times, under the name ''Anarcho-Syndicalism''. A modified version of the essay would be published in the Philosophical Library series ''European Ideologies'' under the name ''Anarchism and Anarcho-Syndicalism'' in 1949.

World War II, and publication of ''Pioneers of American Freedom''

In 1939, Rocker had to undergo a serious operation and was forced to give up lecture tours. However, in the same year, the Rocker Publications Committee was formed by anarchists in Los Angeles to translate and publish Rockers writings. Many of his friends died around this time: Alexander Berkman in 1936, Emma Goldman in 1940, Max Nettlau in 1944; many more were imprisoned in Nazi concentration camps. Although Rocker had opposed his teacher Kropotkin for his support of the Allies during World War I, Rocker argued that the Allied effort in World War II was just, as it would ultimately lead to preservation of libertarian values. Although he viewed every state as a coercive apparatus designed to secure the economic exploitation of the masses, he defended democratic freedoms, which he considered a result of a desire for freedom of the enlightened public. This position was criticized by many American anarchists, who did not support any war. and . After World War II, an appeal in the ''Freie Arbeiter Stimme

''Freie Arbeiter Stimme'' ( yi, פֿרייע אַרבעטער שטימע, romanized: ''Fraye arbeṭer shṭime'', ''lit.'' 'Free Voice of Labor') was a Yiddish-language anarchist newspaper published from New York City's Lower East Side between ...

'' detailing the plight of German anarchists and called for Americans to support them. By February 1946, the sending of aid parcels to anarchists in Germany was a large-scale operation. In 1947, Rocker published ''Zur Betrachtung der Lage in Deutschland'' (''Regarding the Portrayal of the Situation in Germany'') about the impossibility of another anarchist movement in Germany. It became the first post-World War II anarchist writing to be distributed in Germany. Rocker thought young Germans were all either totally cynical or inclined to fascism and awaited a new generation to grow up before anarchism could bloom once again in the country. Nevertheless, the Federation of Libertarian Socialists (FFS) was founded in 1947 by former FAUD members. Rocker wrote for its organ, '' Die Freie Gesellschaft'', which survived until 1953. In 1949, Rocker published another well-known work. In '' Pioneers of American Freedom'', a series of essays, he details the history of liberal and anarchist thought in the United States, seeking to debunk the idea that radical thought was foreign to American history and culture and had merely been imported by immigrants.

Final years and death

On his eightieth birthday in 1953, a dinner was held in London to honor Rocker. Words of tribute were read by the likes ofThomas Mann

Paul Thomas Mann ( , ; ; 6 June 1875 – 12 August 1955) was a German novelist, short story writer, social critic, philanthropist, essayist, and the 1929 Nobel Prize in Literature laureate. His highly symbolic and ironic epic novels and novell ...

, Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theory ...

, Herbert Read, and Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British mathematician, philosopher, logician, and public intellectual. He had a considerable influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, linguistics, ...

.

Political position

Rocker is often described as ananarcho-syndicalist

Anarcho-syndicalism is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that views revolutionary industrial unionism or syndicalism as a method for workers in capitalist society to gain control of an economy and thus control influence i ...

and wrote key introductory texts to that approach as well as the syndicalist platform of the FAUD. He was also close to anarchist-communists such as Kropotkin. Paul Avrich, however, notes that he was a self-professed anarchist without adjectives, believing that anarchist schools of thought

Anarchism is the political philosophy which holds ruling classes and the state to be undesirable, unnecessary and harmful, The following sources cite anarchism as a political philosophy: Slevin, Carl. "Anarchism." ''The Concise Oxford Dicti ...

represented "only different methods of economy" and that the first objective for anarchists was "to secure the personal

Personal may refer to:

Aspects of persons' respective individualities

* Privacy

* Personality

* Personal, personal advertisement, variety of classified advertisement used to find romance or friendship

Companies

* Personal, Inc., a Washington, ...

and social freedom of men".

Works

;Books * ''Nationalism and Culture

''Nationalism and Culture'' is a nonfiction book by German anarcho-syndicalist writer Rudolf Rocker. In this book, he criticizes religion, statism, nationalism, and centralism from an anarchist perspective.

Background

The ideas expressed in the ...

''

* ''Anarcho-Syndicalism: Theory and Practice''

* '' Pioneers of American Freedom''

* ''The Tragedy of Spain''

* ''Anarchism & Anarcho-Syndicalism''

;Articles

* ''Anarchism and Sovietism''

* ''Federalism''

* ''Marx and Anarchism''

Memoirs

Rocker wrote three volumes of memoirs, which have been published in Spanish and Yiddish translations from a German typescript: * ''La juventud de un rebelde'' (Spanish, 1947); ''Di yugnṭ fun a rebel'' (Yiddish, 1965) * ''En la borrasca: Años de destierro'' (Spanish, 1949); ''In shṭurem: Goleś-yorn'' (Yiddish, 1952) * ''Revolución y Regresión'' (Spanish, 1952); ''Reṿolutsye un regresye'' (Yiddish, 1963) The second volume is the only part of the memoirs to have appeared in English, in 1956 and re-edited in 2005, with the title of ''The London Years'', though this is an abridgement of the second volume.References

Notes CitationsBibliography

* * * * * * * * * * *Thesis version

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

External links

Rudolf Rocker Papers

at the

International Institute of Social History

The International Institute of Social History (IISH/IISG) is one of the largest archives of labor and social history in the world. Located in Amsterdam, its one million volumes and 2,300 archival collections include the papers of major figu ...

Profile at the Rudolf Rocker Cultural Center Winnipeg Manitoba

Rudolf Rocker Archive at the Kate Sharpley Library

Rudolf Rocker Archive at libcom.org

Rudolf Rocker page at Anarcho-Syndicalism 101

Rudolf Rocker Texts at Anarchy is Order

* *

at the

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The library ...

contains materials written by Rudolf Rocker.

Rudolf Rocker's son, Fermin, reminiscing about his father and growing up in London

{{DEFAULTSORT:Rocker, Rudolf 1873 births 1958 deaths American anarchists American male non-fiction writers American political writers Anarchist theorists Anarchist writers Anarchists without adjectives Anarcho-syndicalists British anarchists Emigrants from Nazi Germany to the United States German anarchists German emigrants to England German male non-fiction writers German political writers Jewish English history Libertarian socialists Members of the Free Workers' Union of Germany People from Rhenish Hesse People from Yorktown, New York Scholars of nationalism Writers from Mainz Yiddish-language writers