Rodman Wanamaker on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lewis Rodman Wanamaker (February 13, 1863 – March 9, 1928) was an American businessman and heir to the

The

The

Rodman Wanamaker was a pioneer in sponsoring record-breaking aviation projects and in particular and especially an important early backer of

Rodman Wanamaker was a pioneer in sponsoring record-breaking aviation projects and in particular and especially an important early backer of

Rodman Wanamaker was a patron of many important commissions in the field of

Rodman Wanamaker was a patron of many important commissions in the field of

The resulting large bromide prints were presentation photographs, such collections having been placed in several museums. Mostly, the subjects are

The resulting large bromide prints were presentation photographs, such collections having been placed in several museums. Mostly, the subjects are

On January 17, 1916, Wanamaker invited a group of 35 prominent golfers and other leading industry representatives, including the legendary

On January 17, 1916, Wanamaker invited a group of 35 prominent golfers and other leading industry representatives, including the legendary

He accepted an appointment during World War I as Special Deputy Police Commissioner in New York City, greeting distinguished guests from around the world and helping organize the victory parade for

He accepted an appointment during World War I as Special Deputy Police Commissioner in New York City, greeting distinguished guests from around the world and helping organize the victory parade for

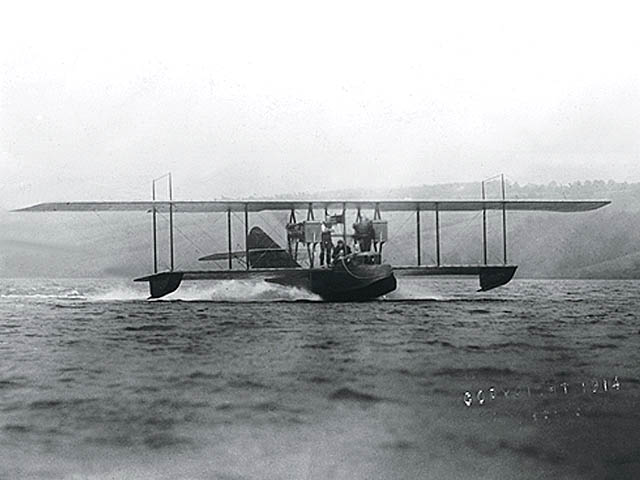

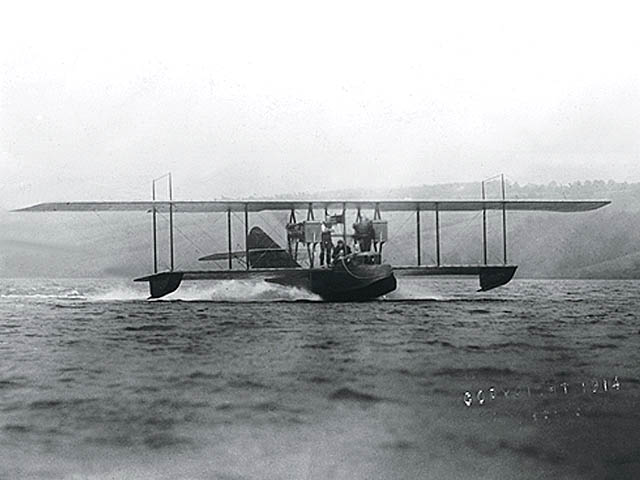

Wanamaker's transatlantic ''America'' flying boat

Film of the assembly and naming of ''America'', June 22, 1914 *

FindLaw , Cases and Codes

* ttp://www.lesliefield.com/personalities/john_wanamaker.htm Obituary in ''Motor Boating'', Jan. 1935at Lesliefield.com * {{DEFAULTSORT:Wanamaker, Rodman 1863 births 1928 deaths American businesspeople in retailing Businesspeople from Philadelphia 1916 United States presidential electors Chairpersons of the Mayor's Committee on Receptions to Distinguished Guests Greeters Burials at the Church of St. James the Less Princeton University alumni Golf administrators Pennsylvania Republicans Wanamaker family

Wanamaker's

John Wanamaker Department Store was one of the first department stores in the United States. Founded by John Wanamaker in Philadelphia, it was influential in the development of the retail industry including as the first store to use price tags. ...

department store fortune. In addition to operating stores in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

, New York City, and Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

, he was a patron of the arts

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, arts patronage refers to the support that kings, popes, and the wealthy have provided to artists su ...

, of education, of golf and athletics

Athletics may refer to:

Sports

* Sport of athletics, a collection of sporting events that involve competitive running, jumping, throwing, and walking

** Track and field, a sub-category of the above sport

* Athletics (physical culture), competi ...

, of Native American scholarship, and of early aviation. He served as a presidential elector

The United States Electoral College is the group of presidential electors required by the Constitution to form every four years for the sole purpose of appointing the president and vice president. Each state and the District of Columbia app ...

for Pennsylvania in 1916, and was appointed Special Deputy Police Commissioner of New York City

The New York City Police Commissioner is the head of the New York City Police Department and presiding member of the Board of Commissioners. The commissioner is appointed by and serves at the pleasure of the Mayor of New York City, mayor. The c ...

under Richard Enright

Richard Edward Enright (August 30, 1871 – September 4, 1953) was an American law enforcement officer, detective, and crime writer and served as NYPD Police Commissioner from 1918 until 1925. He was the first man to rise from the rank-and-fil ...

in February 1918. In this capacity, he founded the world's first police aviation unit and oversaw reorganization of the New York City Reserve Police Force

The New York City Police Department Auxiliary Police is a volunteer reserve police force which is a subdivision of the Patrol Services Bureau of the New York City Police Department. Auxiliary Police Officers assist the NYPD with uniformed patrol ...

. In 1916, Wanamaker originated the proposal for the Professional Golfers' Association of America.

Biography

Wanamaker was born on February 13, 1863, inPhiladelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

to John Wanamaker and Mary Erringer Brown.

Wanamaker entered Princeton University

Princeton University is a private university, private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the List of Colonial Colleges, fourth-oldest ins ...

in 1881, graduating in 1886. In college, he sang in the choir, and was a member and business manager of the Princeton Glee Club

The Princeton University Glee Club is the oldest and most prestigious choir at Princeton University, composed of approximately 100 mixed voices. They give multiple performances throughout the year featuring music from Renaissance to Modern, and ...

. He was a member of the Ivy Club

The Ivy Club, often simply Ivy, is the oldest eating club at Princeton University, and it is "still considered the most prestigious" by its members. It was founded in 1879 with Arthur Hawley Scribner as its first head. Ivy is one of the "Big Four ...

, the first eating club at Princeton University. He was a member of the 1885 Tiger football team that won the national championship when a dramatic last-minute punt return bested the Yale Bulldogs

The Yale Bulldogs are the intercollegiate athletic teams that represent Yale University, located in New Haven, Connecticut. The school sponsors 35 varsity sports. The school has won two NCAA national championships in women's fencing, four in ...

.

In 1886, he joined his father's business, and married Fernanda Henry of Philadelphia. He went to Paris as resident manager in 1889, and lived abroad for more than ten years. When his father purchased the former Alexander Turney Stewart business in New York in 1896, he helped revolutionize the department store with top quality items and is credited in particular with fueling an American demand for French luxury goods.

In 1911 he bought the ''Philadelphia Evening Telegraph

The Philadelphia ''Evening Telegraph'' was a newspaper published in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from 1864 to 1918.

The paper was started on January 4, 1864, by James Barclay Harding and Charles Edward Warburton. Warburton served as publisher unti ...

,'' along with 3rd cousin Samuel Martin Broadbent, who was also an alumnus of Princeton University

Princeton University is a private university, private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the List of Colonial Colleges, fourth-oldest ins ...

.

Wanamaker was content to live in his father's shadow and did not actively seek the limelight except for some official, largely ceremonial positions he held in the City of New York toward the end of his life. Before John Wanamaker died in 1922 he turned all his holdings of the two stores over to Rodman. John Wanamaker had been the sole owner of the business, with his death in 1922, complete control and management passed from father to son. No other retail merchandising business on so large a scale in the world was in the hands of a single man.

Rodman Wanamaker suffered from kidney disease

Kidney disease, or renal disease, technically referred to as nephropathy, is damage to or disease of a kidney. Nephritis is an inflammatory kidney disease and has several types according to the location of the inflammation. Inflammation can ...

in the last decade of his life and the toxins from this condition slowly took their toll on his health. Rodman Wanamaker had a son, Captain John Wanamaker, and two daughters. The son had health problems that made his choice as successor to the father increasingly problematic. After his death control of the stores passed to a board of trustees charged with serving the interests of the surviving Rodman Wanamaker family.

Wanamaker died on March 9, 1928, Atlantic City, New Jersey

Atlantic City, often known by its initials A.C., is a coastal resort city in Atlantic County, New Jersey, United States. The city is known for its casinos, boardwalk, and beaches. In 2020, the city had a population of 38,497.

. He was interred in the Wanamaker family tomb in the churchyard of the Church of St. James the Less in Philadelphia.

Music

The

The Wanamaker Organ

The Wanamaker Grand Court Organ, located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (United States of America) is the largest fully-functioning pipe organ in the world, based on the number of playing pipes, the number of ranks and its weight. (The Boardwalk ...

in Wanamaker's

John Wanamaker Department Store was one of the first department stores in the United States. Founded by John Wanamaker in Philadelphia, it was influential in the development of the retail industry including as the first store to use price tags. ...

(now Macy's

Macy's (originally R. H. Macy & Co.) is an American chain of high-end department stores founded in 1858 by Rowland Hussey Macy. It became a division of the Cincinnati-based Federated Department Stores in 1994, through which it is affiliated wi ...

) department store at 13th and Market Streets in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

, was substantially enlarged by Rodman Wanamaker in 1924. It is presently the world's largest fully functioning pipe organ (An organ with more pipes but fewer ranks is undergoing restoration at Boardwalk Hall

Jim Whelan Boardwalk Hall, formerly known as the Historic Atlantic City Convention Hall, is a multi-purpose arena in Atlantic City in Atlantic County, New Jersey. It was Atlantic City's primary convention center until the opening of the Atlant ...

, in Atlantic City

Atlantic City, often known by its initials A.C., is a coastal resort city in Atlantic County, New Jersey, United States. The city is known for its casinos, Boardwalk (entertainment district), boardwalk, and beaches. In 2020 United States censu ...

, New Jersey). Wanamaker sponsored elaborate recitals in the Grand Court of the Philadelphia store, often featuring Leopold Stokowski

Leopold Anthony Stokowski (18 April 1882 – 13 September 1977) was a British conductor. One of the leading conductors of the early and mid-20th century, he is best known for his long association with the Philadelphia Orchestra and his appear ...

and the Philadelphia Orchestra

The Philadelphia Orchestra is an American symphony orchestra, based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. One of the " Big Five" American orchestras, the orchestra is based at the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts, where it performs its subscription ...

. As many as 15,000 people attended these admission-free events, at which all display counters and fixtures were removed by an army of workers so that seating could be put in place. Under Wanamaker's guidance famous organists were brought to play the Wanamaker Organs in Philadelphia and New York, including Marcel Dupré

Marcel Jean-Jules Dupré () (3 May 1886 – 30 May 1971) was a French organist, composer, and pedagogue.

Biography

Born in Rouen into a wealthy musical family, Marcel Dupré was a child prodigy. His father Aimable Albert Dupré was titular o ...

, Louis Vierne

Louis Victor Jules Vierne (8 October 1870 – 2 June 1937) was a French organist and composer. As the organist of Notre-Dame de Paris from 1900 until his death, he focused on organ music, including six organ symphonies and a '' Messe solennelle ...

, Marco Enrico Bossi

Marco Enrico Bossi (25 April 1861 – 20 February 1925) was an Italian organist, composer, improviser and teacher.

Life

Bossi was born in Salò, a town in the province of Brescia, Lombardy, into a family of musicians. His father, Pietro, was ...

and Nadia Boulanger

Juliette Nadia Boulanger (; 16 September 188722 October 1979) was a French music teacher and conductor. She taught many of the leading composers and musicians of the 20th century, and also performed occasionally as a pianist and organist.

From a ...

. Wanamaker also sponsored a Concert Bureau to book European organists on trans-American concert tours.

In 1926 Wanamaker commissioned a 17-ton bell from founders Gillett & Johnston

Gillett & Johnston was a clockmaker and bell foundry based in Croydon, England from 1844 until 1957. Between 1844 and 1950, over 14,000 tower clocks were made at the works. The company's most successful and prominent period of activity as a bel ...

. It was eventually placed atop the Wanamaker Men's Store at Broad Street and Penn Square in the Lincoln-Liberty Building (one block from then-Wanamaker's main store). Named the "Founder's Bell" in honor of Rodman's father John, founder of the store, it was the largest tuned bell in the world when it was cast.

Toward the end of his life, Wanamaker gathered a huge collection of stringed instrument

String instruments, stringed instruments, or chordophones are musical instruments that produce sound from vibrating strings when a performer plays or sounds the strings in some manner.

Musicians play some string instruments by plucking the st ...

s, known as The Cappella, that featured violas and violins from such masters as Guarnerius

The Guarneri (, , ), often referred to in the Latinized form Guarnerius, is the family name of a group of distinguished luthiers from Cremona in Italy in the 17th and 18th centuries, whose standing is considered comparable to those of the Amati ...

and Stradivarius

A Stradivarius is one of the violins, violas, cellos and other string instruments built by members of the Italian family Stradivari, particularly Antonio Stradivari (Latin: Antonius Stradivarius), during the 17th and 18th centuries. They are co ...

. They were heard at the Wanamaker Philadelphia store and at the White House on December 15, 1927. The orchestra concerts ended with Wanamaker's death in 1928, and the stringed instruments were also sold at that time.

Florence Price

Florence Beatrice Price (née Smith; April 9, 1887 – June 3, 1953) was an American classical composer, pianist, organist and music teacher. Born in Little Rock, Arkansas, Price was educated at the New England Conservatory of Music, and was ac ...

rose to prominence after winning First Prize in the Rodman Wanamaker Symphony Competition of 1932.

Aviation

Rodman Wanamaker was a pioneer in sponsoring record-breaking aviation projects and in particular and especially an important early backer of

Rodman Wanamaker was a pioneer in sponsoring record-breaking aviation projects and in particular and especially an important early backer of transatlantic flight

A transatlantic flight is the flight of an aircraft across the Atlantic Ocean from Europe, Africa, South Asia, or the Middle East to North America, Central America, or South America, or ''vice versa''. Such flights have been made by fixed-wing air ...

development.

In 1913 he commissioned Glen Curtiss

Glenn Hammond Curtiss (May 21, 1878 – July 23, 1930) was an American aviation and motorcycling pioneer, and a founder of the U.S. aircraft industry. He began his career as a bicycle racer and builder before moving on to motorcycles. As early a ...

and his aircraft company to further develop his experimental flying boat designs into a scaled-up version capable of trans-Atlantic crossing in response to the 1913 challenge prize offered by the London newspaper ''The Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily middle-market tabloid newspaper and news websitePeter Wilb"Paul Dacre of the Daily Mail: The man who hates liberal Britain", ''New Statesman'', 19 December 2013 (online version: 2 January 2014) publishe ...

''. The resulting ''America'' flying boat designed under John Cyril Porte

Lieutenant Colonel John Cyril Porte, (26 February 1884 – 22 October 1919) was a British flying boat pioneer associated with the First World War Seaplane Experimental Station at Felixstowe.

Early life and career

Porte was born on 26 Feb ...

's supervision did not cross the Atlantic because of the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, but was sufficiently promising that the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

purchased the two prototypes and ordered an additional fifty aircraft of the model—which became the Curtiss Model H

The Curtiss Model H was a family of classes of early long-range flying boats, the first two of which were developed directly on commission in the United States in response to the £10,000 prize challenge issued in 1913 by the London newspaper, t ...

—for anti-submarine patrolling and air-sea rescue tasks. Shortly before the American entry into World War I

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, p ...

in 1917, Wanamaker donated a Model H to the US government for use in the defense of New York. The design, with some improvements from both British and Americans, rapidly matured during the war and spurred the explosive post-war growth of the flying boat era of International Commercial Aviation. In this sense, Wanamaker holds at least some status as a founding father of an entirely new industry.

Through the American Trans-Oceanic Company

American Trans-Oceanic Company was an airline based in the United States.

History

Rodman Wanamaker published a letter in 1916 stating the founding of the American Trans-Oceanic Company to capitalize on the 1914 effort to fly across the Atlan ...

he also funded efforts to increase aircraft range throughout the next decade so that Wanamaker's entry, the Fokker

Fokker was a Dutch aircraft manufacturer named after its founder, Anthony Fokker. The company operated under several different names. It was founded in 1912 in Berlin, Germany, and became famous for its fighter aircraft in World War I. In 1919 ...

trimotor ''America'', belatedly flown by Commander Richard E. Byrd

Richard Evelyn Byrd Jr. (October 25, 1888 – March 11, 1957) was an American naval officer and explorer. He was a recipient of the Medal of Honor, the highest honor for valor given by the United States, and was a pioneering American aviator, p ...

transited across the Atlantic only a few days after Lindbergh's historic solo crossing on May 21–22, 1927 that won the cash prize in the contest. In both cases, aviation and arguably the world benefited from the sponsorship of Wanamaker.

Liturgical arts

liturgical

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. ''Liturgy'' can also be used to refer specifically to public worship by Christians. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and partic ...

arts, and his legacy includes a sterling silver

Sterling silver is an alloy of silver containing 92.5% by weight of silver and 7.5% by weight of other metals, usually copper. The sterling silver standard has a minimum millesimal fineness of 925.

''Fine silver'', which is 99.9% pure silver, is r ...

altar and silver pulpit

A pulpit is a raised stand for preachers in a Christian church. The origin of the word is the Latin ''pulpitum'' (platform or staging). The traditional pulpit is raised well above the surrounding floor for audibility and visibility, access ...

at the church of the King's estate in Sandringham Sandringham can refer to:

Places

* Sandringham, New South Wales, Australia

* Sandringham, Queensland, Australia

* Sandringham, Victoria, Australia

**Sandringham railway line

**Sandringham railway station

**Electoral district of Sandringham

* Sand ...

, England, as well as a massive processional cross

A processional cross is a crucifix or cross which is carried in Christian processions. Such crosses have a long history: the Gregorian mission of Saint Augustine of Canterbury to England carried one before them "like a standard", according ...

for Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

, known as the Wanamaker Cross of Westminster. He made important additions to his Philadelphia parish of St. Mark's Church, notably the sumptuously-appointed Lady Chapel, which was a memorial to his first wife, Fernanda.

He commissioned architect John T. Windrim to design a free-standing bell tower for the Church of St. James the Less in the Philadelphia neighborhood of Allegheny West. It is also an extensive mausoleum for the Wanamaker family.

Wanamaker-Millrose Games

In 1908 Rodman Wanamaker initiated theMillrose Games The Millrose Games is an annual indoor athletics meet (track and field) held each February in New York City. They started taking place at the Armory in Washington Heights in 2012, after having taken place in Madison Square Garden from 1914 to 2011 ...

. They are now held at The Armory in New York City. (Millrose was Wanamaker's country estate near Jenkintown, Pennsylvania

Jenkintown is a borough in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. It is approximately 10 miles (16 km) north of Center City Philadelphia.

History

The community was named for William Jenkins, a Welsh pioneer settler.

Jenkintown is located just ...

.) He also inaugurated the Wanamaker Mile The Wanamaker Mile is an indoor mile run, mile race held annually at the Millrose Games in New York City. It was named in honour of department store owner Rodman Wanamaker. The event was first held in 1926 inside Madison Square Garden, which was the ...

, and reportedly began the tradition of playing''The Star-Spangled Banner

"The Star-Spangled Banner" is the national anthem of the United States. The lyrics come from the "Defence of Fort M'Henry", a poem written on September 14, 1814, by 35-year-old lawyer and amateur poet Francis Scott Key after witnessing the b ...

'' at sporting events. The games were moved from Madison Square Garden to the New Balance Track and Field Center at The Armory.

Native Americans

Between 1908 and 1913, Wanamaker sponsored three photographic expeditions to the American Indians intended to document a vanishing way of life and make the Indian "first-class citizens" to save them from extinction. At that time, Indians were viewed as a "vanishing race", and efforts were made to bring them increasingly into the mainstream of American life, often at the expense of their culture and traditions. Joseph K. Dixon was the photographer. On the first expedition, he made many portraits and captured scenes of Indian life. Dixon published them in a book, ''The Vanishing Race''. (Original copies of the book are becoming scarce as people break it up to sell the photographs individually.) The expedition climaxed on theCrow Indian Reservation

The Crow Indian Reservation is the homeland of the Crow Tribe. Established 1868, the reservation is located in parts of Big Horn, Yellowstone, and Treasure counties in southern Montana in the United States. The Crow Tribe has an enrolled member ...

with the filming of a motion picture about Hiawatha

Hiawatha ( , also : ), also known as Ayenwathaaa or Aiionwatha, was a precolonial Native American leader and co-founder of the Iroquois Confederacy. He was a leader of the Onondaga people, the Mohawk people, or both. According to some account ...

. The second expedition in 1909 involved a motion filming a reenactment of the Battle of the Little Big Horn

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, and also commonly referred to as Custer's Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Nor ...

. The third expedition, the "Expedition of Citizenship," took place in 1913. For it, the American flag was carried to many tribes, and their members were invited to sign a declaration of allegiance to the United States. In 2018, the film ''Dixon-Wanamaker Expedition To Crow Agency'' (1908) was selected to the National Film Registry

The National Film Registry (NFR) is the United States National Film Preservation Board's (NFPB) collection of films selected for preservation, each selected for its historical, cultural and aesthetic contributions since the NFPB’s inception i ...

as "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

The resulting large bromide prints were presentation photographs, such collections having been placed in several museums. Mostly, the subjects are

The resulting large bromide prints were presentation photographs, such collections having been placed in several museums. Mostly, the subjects are Blackfeet

The Blackfeet Nation ( bla, Aamsskáápipikani, script=Latn, ), officially named the Blackfeet Tribe of the Blackfeet Indian Reservation of Montana, is a federally recognized tribe of Siksikaitsitapi people with an Indian reservation in Mon ...

, Cheyennes

The Cheyenne ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Great Plains. Their Cheyenne language belongs to the Algonquian language family. Today, the Cheyenne people are split into two federally recognized nations: the Southern Cheyenne, who are enrol ...

, Crows

The Common Remotely Operated Weapon Station (CROWS) is a series of remote weapon stations used by the US military on its armored vehicles and ships. It allows weapon operators to engage targets without leaving the protection of their vehicle. T ...

, Dakotas, and other northern plains tribes. Both the glass prints and film negatives of the Wanamaker Collection photographed by Dr. J. Dixon were donated to Indiana University's Mathers Museum of World Cultures

Mathers Museum of World Cultures was a museum of ethnography and cultural history that features exhibitions of traditional and folk arts at Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana. It also offered practicum studies at the university for gradua ...

. They are currently stored at the museum. Many of his more popular pieces are displayed at the museum in both a traveling exhibit and as reprints from the original glass slides and negatives. For information on the exhibit or collections please contact the curator of collections. Thousands of original glass plate negatives are also held in the Research Library of the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

The Wanamaker photographic expeditions are fictionally treated in the novel ''Shadow Catcher'' by Charles Fergus.

In 1909, Wanamaker conceived the idea of a national monument to Native Americans. He developed the project for a Statue of Liberty

The Statue of Liberty (''Liberty Enlightening the World''; French: ''La Liberté éclairant le monde'') is a List of colossal sculpture in situ, colossal neoclassical sculpture on Liberty Island in New York Harbor in New York City, in the U ...

-like colossal statue, and sponsored the 1913 groundbreaking for a National Memorial to the First Americans on Staten Island, at the mouth of New York Harbor. The monument was never built, but photographs of the groundbreaking are represented in the American Museum of Natural History's Library's collection.

Professional Golfers Association

Walter Hagen

Walter Charles Hagen (December 21, 1892 – October 6, 1969) was an American professional golfer and a major figure in golf in the first half of the 20th century. His tally of 11 professional majors is third behind Jack Nicklaus (18) and Tig ...

, and the "Father of American Golf" Alexander A. Findlay to a luncheon at the Taplow Club in New York for an exploratory meeting, which resulted in the formation of the Professional Golfers' Association of America (PGA). During the meeting, Wanamaker hinted that the newly formed organization needed an annual all-professional tournament, and offered to put up $2,500 and various trophies and medals as part of the prize fund. Wanamaker's offer was accepted, and seven months later, the first PGA Championship was played at Siwanoy Country Club

Siwanoy Country Club is a country club located in Bronxville, New York. The club hosted the first PGA Championship in 1916, which was won by Jim Barnes.

History

The Club was incorporated on May 20, 1901 at the Westchester County Clerk's office. ...

in Bronxville, New York

Bronxville is a village in Westchester County, New York, United States, located approximately north of Midtown Manhattan. It is part of the town of Eastchester. The village comprises one square mile (2.5 km2) of land in its entirety, a ...

. Jim Barnes was the first winner of the event and Thomas Kerrigan, the Head Golf Professional at Siwanoy Country Club

Siwanoy Country Club is a country club located in Bronxville, New York. The club hosted the first PGA Championship in 1916, which was won by Jim Barnes.

History

The Club was incorporated on May 20, 1901 at the Westchester County Clerk's office. ...

at the time, was the first player ever to tee off.

First held in October 1916, the PGA Championship

The PGA Championship (often referred to as the US PGA Championship or USPGA outside the United States) is an annual golf tournament conducted by the Professional Golfers' Association of America. It is one of the four men's major championships ...

has evolved into one of the world's premier sporting events, one of golf's four major championships. Each year, now in early August (mid-May beginning in 2019), a top course in the United States hosts the world's best professionals, as they compete for the Wanamaker Trophy.

World War I

General John J. Pershing

General of the Armies John Joseph Pershing (September 13, 1860 – July 15, 1948), nicknamed "Black Jack", was a senior United States Army officer. He served most famously as the commander of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) on the We ...

and the returning doughboys

Doughboy was a popular nickname for the American Infantry, infantryman World War I#Entry of the United States, during World War I. Though the origins of the term are not certain, the nickname was still in use as of the early 1940s. Examples inclu ...

. He purchased more World War I bonds than anyone else in the United States, and generously allowed the use of his residences for the war effort, "virtually putting his enormous wealth at the disposal of the United States." After the war Wanamaker acted as something of an official greeter for the City of New York, often lending his Landaulette

A landaulet, also known as a landaulette, is a car body style where the rear passengers are covered by a convertible top. Often the driver is separated from the rear passengers by a division, as with a limousine.

During the first half of the 20 ...

Rolls-Royce

Rolls-Royce (always hyphenated) may refer to:

* Rolls-Royce Limited, a British manufacturer of cars and later aero engines, founded in 1906, now defunct

Automobiles

* Rolls-Royce Motor Cars, the current car manufacturing company incorporated in ...

for ticker-tape parades.

After the war, he financed the rebuilding of a school in Sarcus

Sarcus is a commune in the Oise department in northern France.

See also

* Communes of the Oise department

The following is a list of the 679 communes of the Oise department of France.

The communes cooperate in the following intercommunali ...

, France. A town fountain was dedicated in his memory.

Real estate

Wanamaker's winter home inPalm Beach, Florida

Palm Beach is an incorporated town in Palm Beach County, Florida. Located on a barrier island in east-central Palm Beach County, the town is separated from several nearby cities including West Palm Beach and Lake Worth Beach by the Intracoas ...

, La Guerida (or "bounty of war"), was built in 1923 by Addison Mizner

Addison Cairns Mizner (December 12, 1872 – February 5, 1933) was an American architect whose Mediterranean Revival and Spanish Colonial Revival style interpretations left an indelible stamp on South Florida, where it continues to inspire archi ...

. In 1933, the compound was purchased by Joe Kennedy for $120,000 (), and eventually gained notoriety as the "Winter White House" of President John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until assassination of Joh ...

. Decades later, the compound was featured at the center of the 1991 William Kennedy Smith rape trial. In 1995 it was purchased by John K. Castle of Castle Harlan for $4.92 million (), and later sold in 2020 to undisclosed trustees for a reported $70 million ().

Wanamaker also owned a townhouse on Spruce Street in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

, a New York residence on Washington Square, a house in Atlantic City

Atlantic City, often known by its initials A.C., is a coastal resort city in Atlantic County, New Jersey, United States. The city is known for its casinos, Boardwalk (entertainment district), boardwalk, and beaches. In 2020 United States censu ...

(where he died), and a country home near his father's estate in Jenkintown, Pennsylvania

Jenkintown is a borough in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. It is approximately 10 miles (16 km) north of Center City Philadelphia.

History

The community was named for William Jenkins, a Welsh pioneer settler.

Jenkintown is located just ...

.

See also

* Albert Leo Stevens * Wanamaker TriplaneReferences

External links

Wanamaker's transatlantic ''America'' flying boat

Film of the assembly and naming of ''America'', June 22, 1914 *

FindLaw , Cases and Codes

* ttp://www.lesliefield.com/personalities/john_wanamaker.htm Obituary in ''Motor Boating'', Jan. 1935at Lesliefield.com * {{DEFAULTSORT:Wanamaker, Rodman 1863 births 1928 deaths American businesspeople in retailing Businesspeople from Philadelphia 1916 United States presidential electors Chairpersons of the Mayor's Committee on Receptions to Distinguished Guests Greeters Burials at the Church of St. James the Less Princeton University alumni Golf administrators Pennsylvania Republicans Wanamaker family