Robert Ley on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Robert Ley (; 15 February 1890 – 25 October 1945) was a German politician and

By April, 1933 Hitler decided to have the Nazi Party take over the

By April, 1933 Hitler decided to have the Nazi Party take over the  Hitler had no sympathy with the

Hitler had no sympathy with the

Hitler and Ley were aware that the suppression of the trade unions and the prevention of wage increases by the Trustees of Labour system, when coupled with their relentless demands for increased productivity to hasten

Hitler and Ley were aware that the suppression of the trade unions and the prevention of wage increases by the Trustees of Labour system, when coupled with their relentless demands for increased productivity to hasten

As Nazi Germany collapsed in early 1945, Ley was among the government figures who remained fanatically loyal to Hitler. He last saw Hitler on 20 April 1945, Hitler's birthday, in the ''

As Nazi Germany collapsed in early 1945, Ley was among the government figures who remained fanatically loyal to Hitler. He last saw Hitler on 20 April 1945, Hitler's birthday, in the ''

Ley's 1936 speech to Nazi Party factory activists

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Ley, Robert 1890 births 1945 deaths 1945 suicides Gauleiters German Army personnel of World War I German people who died in prison custody German prisoners of war in World War I Members of the Academy for German Law Members of the Landtag of Prussia Members of the Reichstag of Nazi Germany Members of the Reichstag of the Weimar Republic National Socialist Working Association members Nazi Party officials Nazi Party politicians Nazis who committed suicide in Germany Nazis who committed suicide in prison custody Officials of Nazi Germany People from Oberbergischer Kreis People from the Rhine Province Prisoners who died in United States military detention Recipients of the Iron Cross (1914), 2nd class Reichsleiters Suicides by hanging in Germany University of Bonn alumni University of Jena alumni University of Münster alumni

labour union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ( ...

leader during the Nazi era

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

; Ley headed the German Labour Front

The German Labour Front (german: Deutsche Arbeitsfront, ; DAF) was the labour organisation under the Nazi Party which replaced the various independent trade unions in Germany during Adolf Hitler's rise to power.

History

As early as March 1933, ...

from 1933 to 1945. He also held many other high positions in the Party, including ''Gauleiter

A ''Gauleiter'' () was a regional leader of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) who served as the head of a ''Administrative divisions of Nazi Germany, Gau'' or ''Reichsgau''. ''Gauleiter'' was the third-highest Ranks and insignia of the Nazi Party, rank in ...

'', ''Reichsleiter

' (national leader or Reich leader) was the second-highest political rank of the Nazi Party (NSDAP), next only to the office of ''Führer''. ''Reichsleiter'' also served as a paramilitary rank within the NSDAP and was the highest position attaina ...

'' and ''Reichsorganisationsleiter''. He committed suicide while awaiting trial at Nuremberg for crimes against humanity

Crimes against humanity are widespread or systemic acts committed by or on behalf of a ''de facto'' authority, usually a state, that grossly violate human rights. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity do not have to take place within the ...

and war crimes.

Early life

Ley was born in Niederbreidenbach (now a part ofNümbrecht

Nümbrecht is a municipality in the Oberbergischer Kreis, in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is a health resort, known for its good climate.

Geography

Nümbrecht is located about 40 km east of Cologne.

Neighbouring places

Division of ...

) in the Rhine Province

The Rhine Province (german: Rheinprovinz), also known as Rhenish Prussia () or synonymous with the Rhineland (), was the westernmost province of the Kingdom of Prussia and the Free State of Prussia, within the German Reich, from 1822 to 1946. It ...

, the seventh of 11 children of a farmer, Friedrich Ley, and his wife Emilie (née

A birth name is the name of a person given upon birth. The term may be applied to the surname, the given name, or the entire name. Where births are required to be officially registered, the entire name entered onto a birth certificate or birth re ...

Wald). He studied chemistry

Chemistry is the science, scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a natural science that covers the Chemical element, elements that make up matter to the chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules and ions ...

at the universities of Jena

Jena () is a German city and the second largest city in Thuringia. Together with the nearby cities of Erfurt and Weimar, it forms the central metropolitan area of Thuringia with approximately 500,000 inhabitants, while the city itself has a popu ...

, Bonn

The federal city of Bonn ( lat, Bonna) is a city on the banks of the Rhine in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, with a population of over 300,000. About south-southeast of Cologne, Bonn is in the southernmost part of the Rhine-Ruhr r ...

, and Münster

Münster (; nds, Mönster) is an independent city (''Kreisfreie Stadt'') in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is in the northern part of the state and is considered to be the cultural centre of the Westphalia region. It is also a state distr ...

. He volunteered for the army on the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in 1914 and spent two years in the 10th Foot Artillery Regiment and saw action on both the eastern

Eastern may refer to:

Transportation

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

*Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 1926 to 1991

*Eastern Air Li ...

and western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

fronts. In 1916 he was promoted to ''Leutnant

() is the lowest Junior officer rank in the armed forces the German (language), German-speaking of Germany (Bundeswehr), Austrian Armed Forces, and military of Switzerland.

History

The German noun (with the meaning "" (in English "deputy") fro ...

'' and trained as an aerial artillery spotter with Artillery Flier Detachment 202. In July 1917 his aircraft was shot down over France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and he was taken prisoner of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of wa ...

. It has been suggested that he suffered a traumatic brain injury in the crash; for the rest of his life he spoke with a stammer

Stuttering, also known as stammering, is a speech disorder in which the flow of speech is disrupted by involuntary repetitions and prolongations of sounds, syllables, words, or phrases as well as involuntary silent pauses or blocks in which the ...

and suffered bouts of erratic behaviour, aggravated by heavy drinking. He earned the Iron Cross

The Iron Cross (german: link=no, Eisernes Kreuz, , abbreviated EK) was a military decoration in the Kingdom of Prussia, and later in the German Empire (1871–1918) and Nazi Germany (1933–1945). King Frederick William III of Prussia est ...

, 2nd class and the Wound Badge

The Wound Badge (german: Verwundetenabzeichen) was a German military decoration first promulgated by Wilhelm II, German Emperor on 3 March 1918, which was first awarded to soldiers of the German Army who were wounded during World War I. Between th ...

, in silver.

After the war Ley was released from captivity in January 1920 and returned to university, gaining a doctorate later that year. He was employed as a food chemist by a branch of the giant IG Farben

Interessengemeinschaft Farbenindustrie AG (), commonly known as IG Farben (German for 'IG Dyestuffs'), was a German chemical and pharmaceutical conglomerate (company), conglomerate. Formed in 1925 from a merger of six chemical companies—BASF, ...

company, based in Leverkusen

Leverkusen () is a city in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, on the eastern bank of the Rhine. To the south, Leverkusen borders the city of Cologne, and to the north the state capital, Düsseldorf.

With about 161,000 inhabitants, Leverkusen is on ...

in the Ruhr

The Ruhr ( ; german: Ruhrgebiet , also ''Ruhrpott'' ), also referred to as the Ruhr area, sometimes Ruhr district, Ruhr region, or Ruhr valley, is a polycentric urban area in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. With a population density of 2,800/km ...

. Enraged by the French occupation of the Ruhr in 1924, Ley became an ultra-nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

and joined the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

soon after reading Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

's speech at his trial following the Beer Hall Putsch

The Beer Hall Putsch, also known as the Munich Putsch,Dan Moorhouse, ed schoolshistory.org.uk, accessed 2008-05-31.Known in German as the or was a failed coup d'état by Nazi Party ( or NSDAP) leader Adolf Hitler, Erich Ludendorff and othe ...

in Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the States of Germany, German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the List of cities in Germany by popu ...

. Ley proved unswervingly loyal to Hitler, which led Hitler to ignore complaints about his arrogance, incompetence and drunkenness.

Ley's impoverished upbringing and his experience as head of the largely working-class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colou ...

Rhineland party region meant that he was sympathetic to those elements in the party who were open to socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

, but he always sided with Hitler in inner party disputes. This helped him survive the hostility of other party officials such as the party treasurer, Franz Xaver Schwarz

Franz Xaver Schwarz (27 November 1875 – 2 December 1947) was a high ranking German Nazi Party official who served as ''Reichsschatzmeister'' (National Treasurer) of the Party throughout most of its existence. He was also one of the highes ...

, who regarded him as an incompetent drunk.

Rise in the Nazi Party

Ley rejoined the re-founded Nazi Party in March 1925, shortly after the ban on the Party was lifted (membership number 18,441). He was named Deputy ''Gauleiter

A ''Gauleiter'' () was a regional leader of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) who served as the head of a ''Administrative divisions of Nazi Germany, Gau'' or ''Reichsgau''. ''Gauleiter'' was the third-highest Ranks and insignia of the Nazi Party, rank in ...

'' of the Southern Rhineland (later, Rhineland

The Rhineland (german: Rheinland; french: Rhénanie; nl, Rijnland; ksh, Rhingland; Latinised name: ''Rhenania'') is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly its middle section.

Term

Historically, the Rhinelands ...

) that month, and was promoted to ''Gauleiter'' on 17 July. In September 1925, he became a member of the National Socialist Working Association

The National Socialist Working Association, sometimes translated as the National Socialist Working Community (German: ''Nazionale Sozialiste Arbeitsgemeinschaft'') was a short-lived group of about a dozen Nazi Party ''Gauleiter'' brought together ...

, a short-lived group of northern and western German ''Gauleiters'', organized and led by Gregor Strasser

Gregor Strasser (also german: Straßer, see ß; 31 May 1892 – 30 June 1934) was an early prominent German Nazi Party, Nazi official and politician who was murdered during the Night of the Long Knives in 1934. Born in 1892 in Bavaria, Strasse ...

, which supported the "socialist" wing of the Party and unsuccessfully sought to amend the Party program

A political party platform (US English), party program, or party manifesto (preferential term in British & often Commonwealth English) is a formal set of principle goals which are supported by a political party or individual candidate, in order ...

. At a meeting on 24 January 1926, however, Ley joined with others in raising objections to Strasser's proposed new draft program and it was shelved. Shortly thereafter, the Working Association was dissolved following the Bamberg Conference The Bamberg Conference (german: Bamberger Führertagung) included some sixty members of the leadership of the Nazi Party, and was specially convened by Adolf Hitler in Bamberg, in Upper Franconia, Germany on Sunday 14 February 1926 during the "wilde ...

.

In March 1928, Ley became the editor and publisher of a virulently anti-Semitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

Nazi newspaper, the ''Westdeutscher Beobachter'' (West German Observer) in Cologne

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western States of Germany, state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 m ...

. On 20 May 1928, he was elected to the Prussian Landtag

The Landtag of Prussia (german: Preußischer Landtag) was the representative assembly of the Kingdom of Prussia implemented in 1849, a bicameral legislature consisting of the upper House of Lords (''Herrenhaus'') and the lower House of Representat ...

, and also was appointed to the Rhenish provincial legislature. He was first elected to the '' Reichstag'' in September 1930 from electoral constituency 20, Cologne-Aachen. He remained as the ''Gauleiter'' of Rhineland until 1 June 1931 when his ''Gau'' was divided into two and new leaders named.

On 21 October 1931, Ley was brought to Munich party headquarters as the Deputy to Strasser, then the head of party organization. Ley was styled ''Reichsorganisationsinspekteur'' and conducted inspection visits to the various ''Gaue''. On 10 June 1932, following a further organizational restructuring by Strasser, Ley was named one of two '' Reichsinspecteurs'' with oversight of approximately half the ''Gaue

''Gau'' (German , nl, gouw , fy, gea or ''goa'' ) is a Germanic term for a region within a country, often a former or current province. It was used in the Middle Ages, when it can be seen as roughly corresponding to an English shire. The adm ...

''. Furthermore, he was made the Acting Landesinspekteur for Bavaria with direct responsibility for the six Bavarian ''Gaue''. This was a short-lived initiative by Strasser to centralize control over the ''Gaue''. However, it was unpopular with the ''Gauleiters'' and was repealed on Strasser's fall from power. Strasser resigned on 8 December 1932 in a break with Hitler over the future direction of the Party. Hitler himself took over as ''Reichsorganisationsleiter'' and installed Ley as his ''Stabschef'' (Chief of Staff). The positions of ''Reichsinspecteur'' and ''Landesinspekteur'' were abolished. When Hitler became Reich Chancellor

The chancellor of Germany, officially the federal chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany,; often shortened to ''Bundeskanzler''/''Bundeskanzlerin'', / is the head of the federal government of Germany and the commander in chief of the Ge ...

in January 1933, Ley accompanied him to Berlin. On 2 June 1933, Ley was among those raised to ''Reichsleiter

' (national leader or Reich leader) was the second-highest political rank of the Nazi Party (NSDAP), next only to the office of ''Führer''. ''Reichsleiter'' also served as a paramilitary rank within the NSDAP and was the highest position attaina ...

'', the second highest political rank in the Nazi Party. On 3 October 1933, Ley was named to Hans Frank

Hans Michael Frank (23 May 1900 – 16 October 1946) was a German politician and lawyer who served as head of the General Government in Nazi-occupied Poland during the Second World War.

Frank was an early member of the German Workers' Party ...

's Academy for German Law

The Academy for German Law (german: Akademie für deutsches Recht) was an institute for legal research and reform founded on 26 June 1933 in Nazi Germany. After suspending its operations during the Second World War in August 1944, it was abolished ...

and, on 10 November 1934, Hitler finally formally promoted Ley to the position of ''Reichsorganisationsleiter''.

Labour Front head

By April, 1933 Hitler decided to have the Nazi Party take over the

By April, 1933 Hitler decided to have the Nazi Party take over the trade union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ( ...

movement. On 10 May 1933, Hitler appointed Ley head of the newly founded German Labour Front

The German Labour Front (german: Deutsche Arbeitsfront, ; DAF) was the labour organisation under the Nazi Party which replaced the various independent trade unions in Germany during Adolf Hitler's rise to power.

History

As early as March 1933, ...

(''Deutsche Arbeitsfront'', DAF). The DAF took over the existing Nazi trade union formation, the National Socialist Factory Cell Organisation (''Nationalsozialistische Betriebszellenorganisation'', NSBO) as well as the main trade union federation. But Ley's lack of administrative ability meant that the NSBO leader, Reinhold Muchow, a member of the socialist wing of the Nazi Party, soon became the dominant figure in the DAF, overshadowing Ley. Muchow began a purge of the DAF administration, rooting out ex-Social Democrat

Social democracy is a Political philosophy, political, Social philosophy, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocati ...

s and ex-Communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

s and placing his own militants in their place.

The NSBO cells continued to agitate in the factories on issues of wages and conditions, annoying the employers, who soon complained to Hitler and other Nazi leaders that the DAF was as bad as the Communists had been.

Hitler had no sympathy with the

Hitler had no sympathy with the syndicalist

Syndicalism is a revolutionary current within the left-wing of the labor movement that seeks to unionize workers according to industry and advance their demands through strikes with the eventual goal of gaining control over the means of pr ...

tendencies of the NSBO, and in January 1934 a new Law for the Ordering of National Labour effectively suppressed independent working-class factory organisations, even Nazi ones, and put questions of wages and conditions in the hands of the Trustees of Labour ('), dominated by the employers. At the same time Muchow was purged and Ley's control over the DAF re-established. The NSBO was completely suppressed and the DAF became little more than an arm of the state for the more efficient deployment and disciplining of labour to serve the needs of the regime, particularly its massive expansion of the arms industry.

As head of the Labour Front, Ley invited Edward, Duke of Windsor, and Wallis, Duchess of Windsor

Wallis, Duchess of Windsor (born Bessie Wallis Warfield, later Simpson; June 19, 1896 – April 24, 1986), was an American socialite and wife of the former King Edward VIII. Their intention to marry and her status as a divorcée caused ...

, to conduct a tour of Germany in 1937, months after Edward had abdicated

Abdication is the act of formally relinquishing monarchical authority. Abdications have played various roles in the succession procedures of monarchies. While some cultures have viewed abdication as an extreme abandonment of duty, in other societ ...

the British throne. Ley served as their host and their personal chaperone. During the visit, Ley's alcoholism was noticed, and at one point he crashed the Windsors' car into a gate.

Once his power was established, Ley began to abuse it in a way that was conspicuous even by the standards of the Nazi regime. On top of his generous salaries as DAF head, ''Reichsorganisationsleiter'', and Reichstag deputy, he pocketed the large profits of the ''Westdeutscher Beobachter'', and freely embezzled DAF funds for his personal use. By 1938 he owned a luxurious estate near Cologne

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western States of Germany, state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 m ...

, a string of villas in other cities, a fleet of cars, a private railway carriage and a large art collection. He increasingly devoted his time to "womanising and heavy drinking, both of which often led to embarrassing scenes in public."

On 29 December 1942 his second wife Inge Ursula née Spilcker (1916–1942) shot herself after a drunken brawl Ley's subordinates took their lead from him, and the DAF became a notorious centre of corruption

Corruption is a form of dishonesty or a criminal offense which is undertaken by a person or an organization which is entrusted in a position of authority, in order to acquire illicit benefits or abuse power for one's personal gain. Corruption m ...

, all paid for with the compulsory dues paid by German workers. One historian says: "The DAF quickly began to gain a reputation as perhaps the most corrupt of all the major institutions of the Third Reich

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

. For this, Ley himself had to shoulder a large part of the blame."

Strength Through Joy

Hitler and Ley were aware that the suppression of the trade unions and the prevention of wage increases by the Trustees of Labour system, when coupled with their relentless demands for increased productivity to hasten

Hitler and Ley were aware that the suppression of the trade unions and the prevention of wage increases by the Trustees of Labour system, when coupled with their relentless demands for increased productivity to hasten German rearmament

German rearmament (''Aufrüstung'', ) was a policy and practice of rearmament carried out in Germany during the interwar period (1918–1939), in violation of the Treaty of Versailles which required German disarmament after WWI to prevent Germa ...

, created a real risk of working-class discontent. In November 1933, as a means of preventing labour disaffection, the DAF established Strength Through Joy

NC Gemeinschaft (KdF; ) was a German state-operated leisure organization in Nazi Germany.Richard Grunberger, ''The 12-Year Reich'', p. 197, It was part of the German Labour Front (german: link=no, Deutsche Arbeitsfront), the national labour org ...

(''Kraft durch Freude'', KdF), to provide a range of benefits and amenities to the German working class and their families. These included subsidised holidays both at resorts across Germany and in "safe" countries abroad (particularly Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

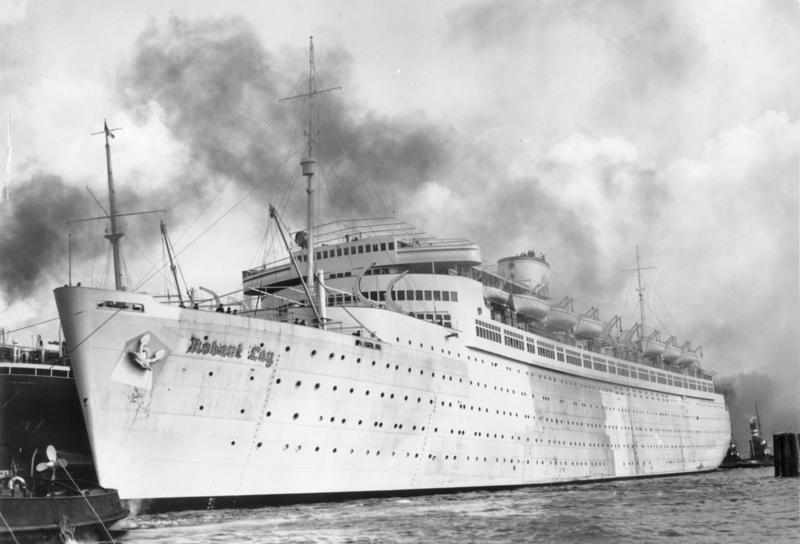

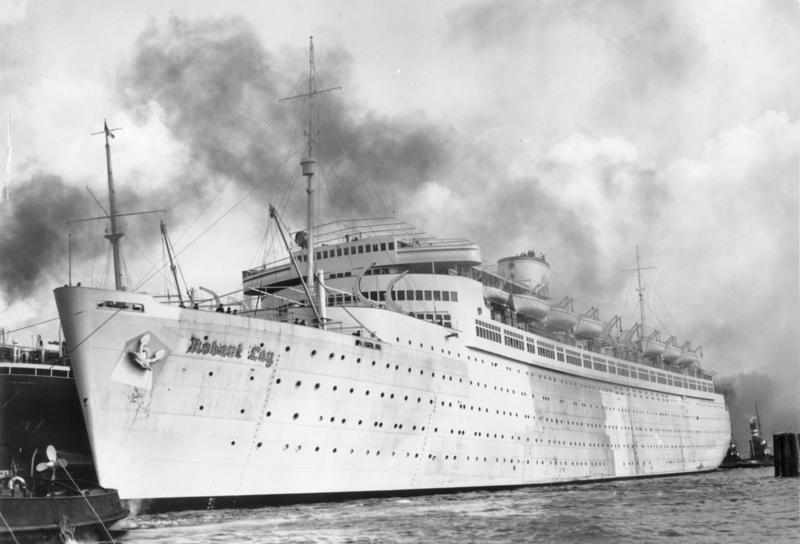

). Two of the world's first purpose-built cruise-liners, the ''Wilhelm Gustloff

Wilhelm Gustloff (30 January 1895 – 4 February 1936) was the founder of the Swiss NSDAP/AO (the Nazi Party organisation for German citizens living outside Germany) at Davos. He remained its leader from 1932 until he was assassinated in 193 ...

'' and the ''Robert Ley

Robert Ley (; 15 February 1890 – 25 October 1945) was a German politician and Labour Union, labour union leader during the Nazi era; Ley headed the German Labour Front from 1933 to 1945. He also held many other high positions in the Party, inc ...

'', were built to take KdF members on Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

cruises.

Other KdF programs included concerts, opera

Opera is a form of theatre in which music is a fundamental component and dramatic roles are taken by singers. Such a "work" (the literal translation of the Italian word "opera") is typically a collaboration between a composer and a librett ...

and other forms of entertainment in factories and other workplaces, free physical education and gymnastics

Gymnastics is a type of sport that includes physical exercises requiring balance, strength, flexibility, agility, coordination, dedication and endurance. The movements involved in gymnastics contribute to the development of the arms, legs, shou ...

training and coaching in sports such as football, tennis and sailing. All this was paid for by the DAF, at a cost of a year by 1937, and ultimately by the workers themselves through their dues, although the employers also contributed. KdF was one of the Nazi regime's most popular programs, and played a large part in reconciling the working class to the regime, at least before 1939.

The DAF and KdF's most ambitious program was the "people's car," the Volkswagen

Volkswagen (),English: , . abbreviated as VW (), is a German Automotive industry, motor vehicle manufacturer headquartered in Wolfsburg, Lower Saxony, Germany. Founded in 1937 by the German Labour Front under the Nazi Party and revived into a ...

, originally a project undertaken at Hitler's request by the car-maker Ferdinand Porsche

Ferdinand Porsche (3 September 1875 – 30 January 1951) was an Austrian-German automotive engineer and founder of the Porsche AG. He is best known for creating the first gasoline–electric hybrid vehicle (Lohner–Porsche), the Volkswag ...

. When the German car industry was unable to meet Hitler's demand that the Volkswagen be sold at or less, the project was taken over by the DAF. This brought Ley's old socialist tendencies back into prominence. The party, he said, had taken over where private industry had failed, because of the "short-sightedness, malevolence, profiteering and stupidity" of the business class. Now working for the DAF, Porsche built a new Volkswagen factory at Fallersleben

Fallersleben is a part (''Ortsteil'') of the City of Wolfsburg, Lower Saxony, Germany, with a population of 11,269 (as of 2010). The village of Fallersleben was first mentioned in 942 under the name of ''Valareslebo''. Fallersleben became a city ...

, at a huge cost which was partly met by raiding the DAF's accumulated assets and misappropriating the dues paid by DAF members. The Volkswagen was sold to German workers on an installment plan, and the first models appeared in February 1939. The outbreak of war, however, meant that none of the 340,000 workers who paid for a car ever received one.

Wartime role

Ley said in a speech in 1939: "We National Socialists have monopolized all resources and all our energies during the past seven years so as to be able to be equipped for the supreme effort of battle." (→German rearmament

German rearmament (''Aufrüstung'', ) was a policy and practice of rearmament carried out in Germany during the interwar period (1918–1939), in violation of the Treaty of Versailles which required German disarmament after WWI to prevent Germa ...

) After the beginning of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

in September 1939, Ley's importance declined. The militarisation of the workforce and the diversion of resources to the war greatly reduced the role of the DAF, and the KdF was largely curtailed. Ley's drunkenness and erratic behaviour were less tolerated in wartime, and he was supplanted by Armaments Minister Fritz Todt

Fritz Todt (; 4 September 1891 – 8 February 1942) was a German construction engineer and senior Nazi who rose from the position of Inspector General for German Roadways, in which he directed the construction of the German autobahns (''Reichsa ...

and his successor Albert Speer

Berthold Konrad Hermann Albert Speer (; ; 19 March 1905 – 1 September 1981) was a German architect who served as the Minister of Armaments and War Production in Nazi Germany during most of World War II. A close ally of Adolf Hitler, he ...

as the czar of the German workforce (the head of the ''Organisation Todt

Organisation Todt (OT; ) was a civil and military engineering organisation in Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945, named for its founder, Fritz Todt, an engineer and senior Nazi. The organisation was responsible for a huge range of engineering projec ...

'' (OT)). As German workers were increasingly conscripted, foreign workers, first "guest workers" from France and later slave labourers from Poland, Ukraine and other eastern countries, were brought in to replace them. Ley played some role in this program, but was overshadowed by Fritz Sauckel

Ernst Friedrich Christoph "Fritz" Sauckel (27 October 1894 – 16 October 1946) was a German Nazi politician, ''Gauleiter'' of Gau Thuringia from 1927 and the General Plenipotentiary for Labour Deployment (''Arbeitseinsatz'') from March 1942 unti ...

, General Plenipotentiary for the Distribution of Labour (''Generalbevollmächtigter für den Arbeitseinsatz'') since March 1942.

Nevertheless, Ley was deeply implicated in the mistreatment of foreign slave workers. In October 1942 he attended a meeting in Essen

Essen (; Latin: ''Assindia'') is the central and, after Dortmund, second-largest city of the Ruhr, the largest urban area in Germany. Its population of makes it the fourth-largest city of North Rhine-Westphalia after Cologne, Düsseldorf and D ...

with Paul Plieger

Paul may refer to:

*Paul (given name), a given name (includes a list of people with that name)

*Paul (surname), a list of people

People

Christianity

* Paul the Apostle (AD c.5–c.64/65), also known as Saul of Tarsus or Saint Paul, early Chri ...

(head of the giant Hermann Göring Works industrial combine) and leaders of the German coal industry. A verbatim account of the meeting was kept by one of the managers. A recent historian writes:

Despite his failings, Ley retained Hitler's favour; until the last months of the war he was part of Hitler's inner circle along with Martin Bormann

Martin Ludwig Bormann (17 June 1900 – 2 May 1945) was a German Nazi Party official and head of the Nazi Party Chancellery. He gained immense power by using his position as Adolf Hitler's private secretary to control the flow of information ...

and Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the ''Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to 19 ...

. In November 1940 he was given a new role, as Reich Commissioner for Social Housing Construction (''Reichskommissar für den sozialen Wohnungsbau''), later shortened to Reich Housing Commissioner (''Reichswohnungskommissar''). Here his job was to prepare for the effects on German housing of the expected Allied air attacks on German cities, which began to increase in intensity from 1941 onwards. In this role he became a key ally of Armaments Minister Albert Speer, who recognised that German workers must be adequately housed if productivity was to be maintained. As the air war against Germany increased from 1943, "dehousing

Frederick Lindemann, 1st Viscount Cherwell, Professor Frederick Lindemann, Baron Cherwell, the British government's chief scientific adviser, sent on 30 March 1942 to British Prime Minister Winston Churchill a memorandum which, after it was accep ...

" German workers became an objective of the Allied area bombing

In military aviation, area bombardment (or area bombing) is a type of aerial bombardment in which bombs are dropped over the general area of a target. The term "area bombing" came into prominence during World War II.

Area bombing is a form of str ...

campaign, and Ley's organisation was increasingly unable to cope with the resulting housing crisis.

He was aware in general terms of the Nazi regime's programme of extermination of the Jews of Europe. Ley encouraged it through the virulent anti-Semitism of his publications and speeches. In February 1941 he was present at a meeting along with Speer, Bormann and Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel

Wilhelm Bodewin Johann Gustav Keitel (; 22 September 188216 October 1946) was a German field marshal and war criminal who held office as chief of the '' Oberkommando der Wehrmacht'' (OKW), the high command of Nazi Germany's Armed Forces, duri ...

at which Hitler had set out his views on the " Jewish question" at some length, making it clear that he intended the "disappearance" of the Jews one way or another. According to American historian Jeffrey Herf

Jeffrey C. Herf (born April 24, 1947) is an American historian of Modern European, in particular, modern German history. He is Distinguished University Professor of modern European at the University of Maryland, College Park.

Biography

He was born ...

, Ley issued some of the most overt propaganda accusing Jews of plotting the extermination of Germans and threatening to do the reverse. In December 1939, he said that in the event of a British victory:

In April 1945, Ley became enamored with the idea of creating a "death ray

The death ray or death beam was a theoretical particle beam or electromagnetic weapon first theorized around the 1920s and 1930s. Around that time, notable inventors such as Guglielmo Marconi, Nikola Tesla, Harry Grindell Matthews, Edwin R. Scot ...

" after receiving a letter from an unnamed inventor: "I've studied the documentation; there's no doubt about it. This will be the decisive weapon!" Once Ley gave Speer a list of materials, including a particular model circuit breaker, Speer found that the circuit breaker had not been manufactured in 40 years.

Postwar; arrest and suicide

As Nazi Germany collapsed in early 1945, Ley was among the government figures who remained fanatically loyal to Hitler. He last saw Hitler on 20 April 1945, Hitler's birthday, in the ''

As Nazi Germany collapsed in early 1945, Ley was among the government figures who remained fanatically loyal to Hitler. He last saw Hitler on 20 April 1945, Hitler's birthday, in the ''Führerbunker

The ''Führerbunker'' () was an air raid shelter located near the Reich Chancellery in Berlin, Germany. It was part of a subterranean bunker complex constructed in two phases in 1936 and 1944. It was the last of the Führer Headquarters ( ...

'' in central Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

. The next day he left for southern Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

, in the expectation that Hitler would make his last stand in the " National Redoubt" in the alpine areas. When Hitler refused to leave Berlin, Ley was effectively unemployed.

On 16 May he was captured by American paratroopers of the 101st Airborne Division

The 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) ("Screaming Eagles") is a light infantry division of the United States Army that specializes in air assault operations. It can plan, coordinate, and execute multiple battalion-size air assault operati ...

in a shoemaker's house in the village of Schleching

Schleching is a municipality and a village in Traunstein district in Bavaria, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Rus ...

. Ley told them he was "Dr Ernst Distelmeyer," but he was identified by Franz Xaver Schwarz

Franz Xaver Schwarz (27 November 1875 – 2 December 1947) was a high ranking German Nazi Party official who served as ''Reichsschatzmeister'' (National Treasurer) of the Party throughout most of its existence. He was also one of the highes ...

, the treasurer of the Nazi Party and a long-time enemy. After his arrest, he declared "You can torture or beat me or impale me on a stake. But I will never doubt the greater deeds of Hitler."

At the Nuremberg Trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies of World War II, Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945 ...

, Ley was indicted under Count One ("The Common Plan or Conspiracy to wage an aggressive war in violation of international law or treaties"), Count Three (War Crimes, including among other things "mistreatment of prisoners of war or civilian populations") and Count Four ("Crimes Against Humanity

Crimes against humanity are widespread or systemic acts committed by or on behalf of a ''de facto'' authority, usually a state, that grossly violate human rights. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity do not have to take place within the ...

– murder, extermination, enslavement of civilian populations; persecution on the basis of racial, religious or political grounds"). Ley was apparently indignant at being regarded as a war criminal, telling the American psychiatrist Douglas Kelley

Lt. Colonel Douglas McGlashan Kelley (11 August 1912 – January 1, 1958) was a United States Army Military Intelligence Corps officer who served as chief psychiatrist at Nuremberg Prison during the Nuremberg War Trials. He worked to asce ...

Jack El-Hai : ''The Nazi and the Psychiatrist: Hermann Göring, Dr Douglas M. Kelley, and a Fatal Meeting of Minds at the End of WWII'', Publisher: PublicAffairs, 2013, and psychologist Gustave Gilbert who had seen and tested him in prison: "Stand us against a wall and shoot us, well and good, you are victors. But why should I be brought before a Tribunal like a c-c-c- ... I can't even get the word out!".

On 24 October, three days after receiving the indictment, Ley strangled himself to death in his prison cell using a noose made by tearing a towel into strips, fastened to the toilet pipe in his cell.

See also

*Glossary of Nazi Germany

This is a list of words, terms, concepts and slogans of Nazi Germany used in the historiography covering the Nazi regime.

Some words were coined by Adolf Hitler and other Nazi Party members. Other words and concepts were borrowed and appropriated, ...

* List of Nazi Party leaders and officials

This is a list of Nazi Party (NSDAP) leaders and officials. It is not meant to be an all inclusive list.

A

* Gunter d'Alquen – Chief Editor of the SS official newspaper, ''Das Schwarze Korps'' ("The Black Corps"), and commander of the S ...

* List of people who died by suicide by hanging

Notes

References

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Ley's 1936 speech to Nazi Party factory activists

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Ley, Robert 1890 births 1945 deaths 1945 suicides Gauleiters German Army personnel of World War I German people who died in prison custody German prisoners of war in World War I Members of the Academy for German Law Members of the Landtag of Prussia Members of the Reichstag of Nazi Germany Members of the Reichstag of the Weimar Republic National Socialist Working Association members Nazi Party officials Nazi Party politicians Nazis who committed suicide in Germany Nazis who committed suicide in prison custody Officials of Nazi Germany People from Oberbergischer Kreis People from the Rhine Province Prisoners who died in United States military detention Recipients of the Iron Cross (1914), 2nd class Reichsleiters Suicides by hanging in Germany University of Bonn alumni University of Jena alumni University of Münster alumni