Robert Devereaux, Earl Of Essex on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, KG, PC (; 10 November 1565 – 25 February 1601) was an English nobleman and a favourite of Queen Elizabeth I. Politically ambitious, and a committed general, he was placed under

Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, KG, PC (; 10 November 1565 – 25 February 1601) was an English nobleman and a favourite of Queen Elizabeth I. Politically ambitious, and a committed general, he was placed under

Devereux first came to court in 1584, and by 1587 had become a favourite of the Queen, who relished his lively mind and eloquence, as well as his skills as a showman and in courtly love. In June 1587 he replaced the Earl of Leicester as Master of the Horse. After Leicester's death in 1588, the Queen transferred the late Earl's royal monopoly on sweet wines to Essex, providing him with revenue from taxes. In 1593, he was made a member of her

Devereux first came to court in 1584, and by 1587 had become a favourite of the Queen, who relished his lively mind and eloquence, as well as his skills as a showman and in courtly love. In June 1587 he replaced the Earl of Leicester as Master of the Horse. After Leicester's death in 1588, the Queen transferred the late Earl's royal monopoly on sweet wines to Essex, providing him with revenue from taxes. In 1593, he was made a member of her

Essex's greatest failure was as

Essex's greatest failure was as

''The Career of the Earl of Essex from the Islands Voyage in 1597 to His Execution in 1601''

Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1923. . * Dickinson, Janet, ''Court Politics and the Earl of Essex, 1589-1601'' (Routledge: Abingdon, 2016). * Ellis, Steven G.: ''Tudor Ireland'' (London, 1985). . * Falls, Cyril: ''Elizabeth's Irish Wars'' (1950; reprint London, 1996). . * * Lacey, Robert: ''Robert, Earl of Essex: An Elizabethan Icarus'' (Weidenfeld & Nicolson 1971) * * Shapiro, James: ''1599: A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare'' (London, 2005) . * Smith, Lacey Baldwin: ''Treason in Tudor England: Politics & Paranoia'' (Pimlico 2006) *

English Broadside Ballad Archive

, - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Essex, Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl Of 1565 births 1601 deaths 16th-century English nobility 17th-century English nobility Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge 09 12 British and English royal favourites Burials at the Church of St Peter ad Vincula Chancellors of the University of Cambridge Chancellors of the University of Dublin Robert Earls Marshal 3 English people of the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604) English politicians convicted of crimes English rebels Executions at the Tower of London Executed people from Herefordshire Knights of the Garter Lords Lieutenant of Ireland People executed by Tudor England by decapitation People executed under Elizabeth I People executed under the Tudors for treason against England People from Bromyard People of Elizabethan Ireland People of the Elizabethan era People of the Nine Years' War (Ireland) Treason trials

house arrest

In justice and law, house arrest (also called home confinement, home detention, or, in modern times, electronic monitoring) is a measure by which a person is confined by the authorities to their residence. Travel is usually restricted, if all ...

following a poor campaign in Ireland during the Nine Years' War

The Nine Years' War (1688–1697), often called the War of the Grand Alliance or the War of the League of Augsburg, was a conflict between France and a European coalition which mainly included the Holy Roman Empire (led by the Habsburg monarch ...

in 1599. In 1601, he led an abortive '' coup d'état'' against the government of Elizabeth I and was executed for treason.

Early life

Devereux was born on 10 November 1565 at Netherwood near Bromyard, in Herefordshire, the son of Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex, and Lettice Knollys. His maternal great-grandmotherMary Boleyn

Mary Boleyn, also known as Lady Mary, (c. 1499 – 19 July 1543) was the sister of English queen consort Anne Boleyn, whose family enjoyed considerable influence during the reign of King Henry VIII.

Mary was one of the mistresses of Henry VII ...

was a sister of Anne Boleyn, the mother of Queen Elizabeth I, making him a first-cousin-twice-removed of the Queen.

He was brought up on his father's estates at Chartley Castle

Chartley Castle lies in ruins to the north of the village of Stowe-by-Chartley in Staffordshire, between Stafford and Uttoxeter (). Mary, Queen of Scots, was imprisoned on the estate in 1585. The remains of the castle and associated earthworks a ...

, Staffordshire, and at Lamphey, Pembrokeshire

Pembrokeshire ( ; cy, Sir Benfro ) is a Local government in Wales#Principal areas, county in the South West Wales, south-west of Wales. It is bordered by Carmarthenshire to the east, Ceredigion to the northeast, and the rest by sea. The count ...

, in Wales. His father died in 1576, and the new Earl of Essex became a ward of Lord William Cecil of Burghley House

Burghley House () is a grand sixteenth-century English country house near Stamford, Lincolnshire. It is a leading example of the Elizabethan prodigy house, built and still lived in by the Cecil family. The exterior largely retains its Elizabet ...

. In 1577, he was admitted as a fellow-commoner at Trinity College, Cambridge; in 1579, he matriculated; and in 1581 he graduated as a Master of Arts.

On 21 September 1578, Essex's mother married Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, Elizabeth I's long-standing favourite and Robert Devereux's godfather.

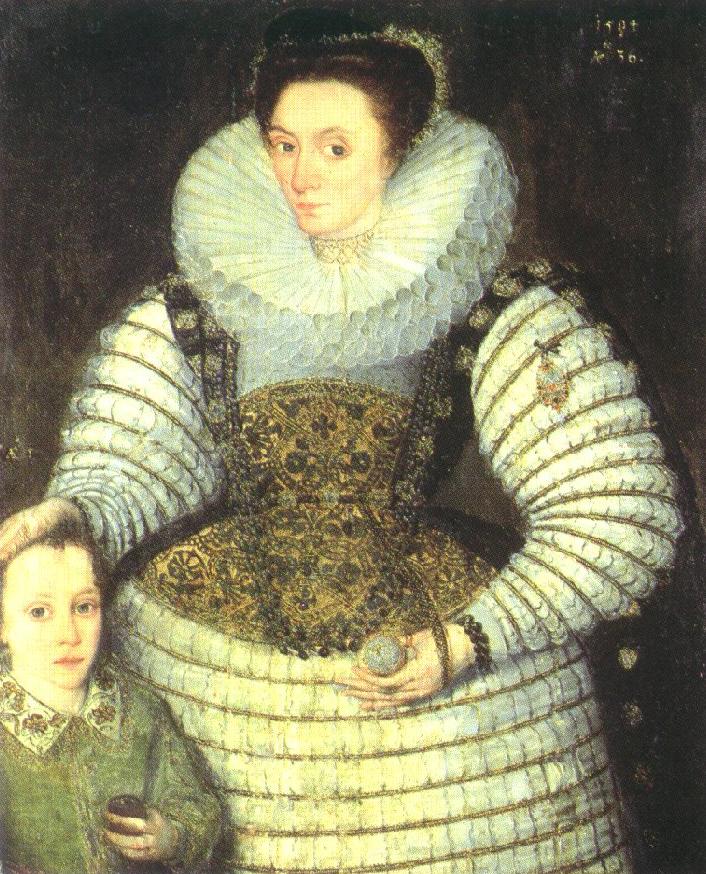

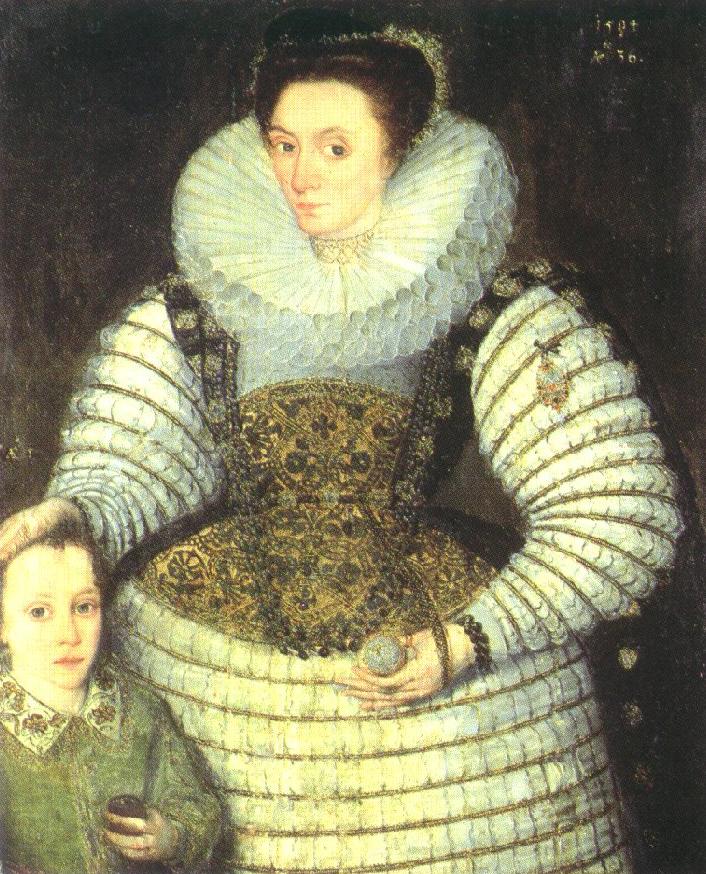

Essex performed military service under his stepfather in the Netherlands, before making an impact at court and winning the Queen's favour. In 1590, he married Frances Walsingham, daughter of Sir Francis Walsingham and widow of Sir Philip Sidney, by whom he had several children, three of whom survived into adulthood. Elizabeth was against the marriage. Sidney, who was Leicester's nephew, had died from an infected gun wound in 1586, 31 days after his participation in the Battle of Zutphen in which Essex had also distinguished himself. In October 1591, Essex's mistress, Elizabeth Southwell

Lady Elizabeth Southwell ( née Cromwell), called Lady Cromwell (1674–1709) was an English noblewoman, the only daughter of Vere Essex Cromwell, 4th Earl of Ardglass and wife Catherine Hamilton.

Title

When her father died in 1687, she claimed ...

, gave birth to their son Walter Devereux (died 1641).

Court and military career

Devereux first came to court in 1584, and by 1587 had become a favourite of the Queen, who relished his lively mind and eloquence, as well as his skills as a showman and in courtly love. In June 1587 he replaced the Earl of Leicester as Master of the Horse. After Leicester's death in 1588, the Queen transferred the late Earl's royal monopoly on sweet wines to Essex, providing him with revenue from taxes. In 1593, he was made a member of her

Devereux first came to court in 1584, and by 1587 had become a favourite of the Queen, who relished his lively mind and eloquence, as well as his skills as a showman and in courtly love. In June 1587 he replaced the Earl of Leicester as Master of the Horse. After Leicester's death in 1588, the Queen transferred the late Earl's royal monopoly on sweet wines to Essex, providing him with revenue from taxes. In 1593, he was made a member of her Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

.

It is reported that his friend and confidant Francis Bacon warned him to avoid offending the Queen by attempting to gain power and underestimating her ability to rule and wield power.

Essex underestimated the Queen, however, and his later behaviour towards her lacked due respect and showed disdain for the influence of her principal secretary, Robert Cecil Robert Cecil may refer to:

* Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury (1563–1612), English administrator and politician, MP for Westminster, and for Hertfordshire

* Robert Cecil (1670–1716), Member of Parliament for Castle Rising, and for Wootton Ba ...

. On one occasion during a heated Privy Council debate on the problems in Ireland, the Queen reportedly cuffed an insolent Essex round the ear, prompting him to half draw his sword on her.

In 1589, he took part in Francis Drake

Sir Francis Drake ( – 28 January 1596) was an English explorer, sea captain, privateer, slave trader, naval officer, and politician. Drake is best known for his circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition, from 1577 to 1580 (t ...

's English Armada, which sailed to Spain in an unsuccessful attempt to press home the English advantage following the defeat of the Spanish Armada

The Spanish Armada (a.k.a. the Enterprise of England, es, Grande y Felicísima Armada, links=no, lit=Great and Most Fortunate Navy) was a Spanish fleet that sailed from Lisbon in late May 1588, commanded by the Duke of Medina Sidonia, an aris ...

, although the Queen had ordered him not to take part. The English Armada was defeated with 40 ships sunk and 15,000 men lost. In 1591, he was given command of a force sent to the assistance of King Henry IV of France. In 1596, he distinguished himself by the capture of Cádiz. During the Islands Voyage expedition to the Azores in 1597, with Walter Raleigh as his second-in-command, he defied the Queen's orders, pursuing the Spanish treasure fleet without first defeating the Spanish battle fleet.

When the 3rd Spanish Armada

The 3rd Spanish Armada, also known as the Spanish Armada of 1597, was a major naval event that took place between October and November 1597 as part of the Anglo–Spanish War.Graham pp. 212–213 The armada, which was the third attempt by Spain ...

first appeared off the English coast in October 1597, the English fleet was far out to sea, with the coast almost undefended, and panic ensued. This further damaged the relationship between the Queen and Essex, even though he was initially given full command of the English fleet when he reached England a few days later. Fortunately, a storm dispersed the Spanish fleet. A number of ships were captured by the English and though there were a few landings, the Spanish withdrew.

Ireland

Essex's greatest failure was as

Essex's greatest failure was as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland

Lord Lieutenant of Ireland (), or more formally Lieutenant General and General Governor of Ireland, was the title of the chief governor of Ireland from the Williamite Wars of 1690 until the Partition of Ireland in 1922. This spanned the Kingdo ...

, a post which he talked himself into in 1599. The Nine Years' War

The Nine Years' War (1688–1697), often called the War of the Grand Alliance or the War of the League of Augsburg, was a conflict between France and a European coalition which mainly included the Holy Roman Empire (led by the Habsburg monarch ...

(1595–1603) was in its middle stages, and no English commander had been successful. More military force was required to defeat the Irish chieftains, led by Hugh O'Neill, the Earl of Tyrone, and supplied from Spain and Scotland.

Essex led the largest expeditionary force ever sent to Ireland—16,000 troops—with orders to put an end to the rebellion. He departed London to the cheers of the Queen's subjects, and it was expected the rebellion would be crushed instantly, but the limits of Crown resources and of the Irish campaigning season dictated otherwise.

Essex had declared to the Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

that he would confront O'Neill in Ulster. Instead, he led his army into southern Ireland, where he fought a series of inconclusive engagements, wasted his funds, and dispersed his army into garrisons, while the Irish won two important battles in other parts of the country. Rather than face O'Neill in battle, Essex entered a truce that some considered humiliating to the Crown and to the detriment of English authority. The Queen herself told Essex that if she had wished to abandon Ireland it would scarcely have been necessary to send him there.

In all of his campaigns, Essex secured the loyalty of his officers by conferring knighthoods, an honour the Queen herself dispensed sparingly, and by the end of his time in Ireland more than half the knights in England owed their rank to him. The rebels were said to have joked that, "he never drew sword but to make knights," but his practice of conferring knighthoods could in time enable Essex to challenge the powerful factions at Cecil's command.

He was the second Chancellor of the University of Dublin

The University of Dublin ( ga, Ollscoil Átha Cliath), corporately designated the Chancellor, Doctors and Masters of the University of Dublin, is a university located in Dublin, Ireland. It is the degree-awarding body for Trinity College Dubl ...

, serving from 1598 to 1601. He was educated at Trinity College Dublin.

First trial

Relying on his general warrant to return to England, given under the great seal, Essex sailed from Ireland on 24 September 1599 and reached London four days later. The Queen had expressly forbidden his return and was surprised when he presented himself in her bedchamber one morning at Nonsuch Palace, before she was properly wigged or gowned. On that day, the Privy Council met three times, and it seemed his disobedience might go unpunished, although the Queen did confine him to his rooms with the comment that "an unruly beast must be stopped of his provender." Essex appeared before the full Council on 29 September, when he was compelled to stand before the council during a five-hour interrogation. The Council—his uncle William Knollys, 1st Earl of Banbury included—took a quarter of an hour to compile a report, which declared that his truce with O'Neill was indefensible and his flight from Ireland tantamount to the desertion of duty. He was committed to the custody of Sir Richard Berkeley in his own York House on 1 October, and he blamed Cecil and Raleigh for the queen's hostility. Raleigh advised Cecil to see to it that Essex did not recover power, and Essex appeared to heed advice to retire from public life, despite his popularity with the public. During his confinement at York House, Essex probably communicated with KingJames VI of Scotland

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until hi ...

through Lord Mountjoy

The titles of Baron Mountjoy and Viscount Mountjoy have been created several times for members of various families, including the Blounts and their descendants and the Stewarts of Ramelton and their descendants.

The first creation was for Walter ...

, although any plans he may have had at that time to help the Scots king capture the English throne came to nothing. In October, Mountjoy was appointed to replace him in Ireland, and matters seemed to look up for the Earl. In November, the queen was reported to have said that the truce with O'Neill was "so seasonably made... as great good... has grown by it." Others in the council were willing to justify Essex's return from Ireland, on the grounds of the urgent necessity of a briefing by the commander-in-chief.

Cecil kept up the pressure and, on 5 June 1600, Essex was tried before a commission of 18 men. He had to hear the charges and evidence on his knees. Essex was convicted, deprived of public office, and returned to virtual confinement.

Essex's rebellion

In August, his freedom was granted, but the source of his basic income—the sweet wines monopoly—was not renewed. His situation had become desperate, and he shifted "from sorrow and repentance to rage and rebellion." In early 1601, he began to fortify Essex House, his town mansion on the Strand, and gathered his followers. On the morning of 8 February, he marched out of Essex House with a party of nobles and gentlemen (some later involved in the 1605 Gunpowder Plot) and entered the city of London in an attempt to force an audience with the Queen. Cecil immediately had him proclaimed a traitor. A force under Sir John Leveson placed a barrier across the street at Ludgate Hill. When Essex's men tried to force their way through, Essex's stepfather, Sir Christopher Blount, was injured in the resulting skirmish, and Essex withdrew with his men to Essex House. Essex surrendered after Crown forces besieged Essex House.Treason trial and death

On 19 February 1601, Essex was tried before his peers on charges of treason. Quoting from ''State Trials'' (compiled by T. B. Howell and T. J. Howell, 33 vols., London, 1809–26, vol. I, pp. 1334-1360), Laura Hanes Cadwallader summarised the indictment:The indictment charged Essex with "conspiring and imagining at London, . . . to depose and slay the Queen, and to subvert the Government." It also stated that Essex had "endeavoured to raise himself to the Crown of England, and usurp the royal dignity," and that in order to fulfill these intentions, he and others "rose and assembled themselves in open rebellion, and moved and persuaded many of the citizens of London to join them in their treason, and endeavoured to get the City of London into their possession and power, and wounded and killed many of the Queen's subjects then and there assembled for the purpose of quelling such rebellion." Essex was charged also with holding the Lord Keeper and the other Privy Councillors in custody "for four hours and more."Part of the evidence showed that he was in favour of toleration of religious dissent. In his own evidence, he countered the charge of dealing with Catholics, swearing that "papists have been hired and suborned to witness against me." Essex also asserted that Cecil had stated that none in the world but the

Infanta of Spain

Infante of Spain (f. Infanta; Spanish: ''Infante de España''; f. ''Infanta'') is a royal title normally granted at birth to sons and daughters of reigning and past Spanish monarchs, and to the sons and daughters of the heir to the Crown. Indiv ...

had right to the Crown of England, whereupon Cecil (who had been following the trial at a doorway concealed behind some tapestry) stepped out to make a dramatic denial, going down on his knees to give thanks to God for the opportunity. The witness whom Essex expected to confirm this allegation, his uncle William Knollys, was called and admitted there had once been read in Cecil's presence a book treating such matters. The book may have been either ''The book of succession'' supposedly by R. Doleman but probably by Robert Persons or Persons' '' A Conference about the Next Succession to the Crown of England'', works which favoured a Catholic successor friendly to Spain. Knollys denied hearing Cecil make the statement. Thanking God again, Cecil expressed his gratitude that Essex was exposed as a traitor while he himself was found an honest man.

Essex was found guilty and, on 25 February 1601, was beheaded on Tower Green, the last person to be beheaded in the Tower of London. It was reported to have taken three strokes by the executioner Thomas Derrick to complete the beheading. Previously Thomas Derrick had been convicted of rape but had been pardoned by the Earl of Essex himself (clearing him of the death penalty) on the condition that he become an executioner at Tyburn. At Sir Walter Raleigh's own execution on 29 October 1618, it was alleged that Raleigh had said to a co-conspirator, "Do not, as my Lord Essex did, take heed of a preacher. By his persuasion, he confessed, and made himself guilty." In that same trial, Raleigh also denied that he had stood at a window during the execution of Essex's sentence, disdainfully puffing out tobacco smoke in sight of the condemned man. Essex in the end shocked many by denouncing his sister Penelope, Lady Rich as his co-conspirator: the Queen, who was determined to show as much clemency as possible, ignored the charge.

Some days before the execution, Captain Thomas Lee was apprehended as he kept watch on the door to the Queen's chambers. His plan had been to confine her until she signed a warrant for the release of Essex. Captain Lee, who had served in Ireland with the Earl, and who acted as a go-between with the Ulster rebels, was tried and put to death the next day.

Essex's conviction for treason meant that the earldom was forfeit and his son did not inherit the title. However, after the Queen's death, King James I of England reinstated the earldom in favour of the disinherited son, Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex

Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex, KB, PC (; 11 January 1591 – 14 September 1646) was an English Parliamentarian and soldier during the first half of the 17th century. With the start of the Civil War in 1642, he became the first Captain ...

.

The Essex ring

There is a widely repeated romantic legend about a ring given by Elizabeth to Essex. There is a possible reference to the legend by John Webster in his 1623 play '' The Devil's Law Case'' suggesting that it was known at this time, but the first printed version of it is in the 1695 romantic novel ''The Secret History of the most renowned Queen Elizabeth and the Earl of Essex, by a Person of Quality''. The version given by David Hume in his ''History of England

England became inhabited more than 800,000 years ago, as the discovery of stone tools and footprints at Happisburgh in Norfolk have indicated.; "Earliest footprints outside Africa discovered in Norfolk" (2014). BBC News. Retrieved 7 February ...

'' says that Elizabeth had given Essex a ring after the expedition to Cadiz that he should send to her if he was in trouble. After his trial, he tried to send the ring to Elizabeth via the Countess of Nottingham, but the countess kept the ring as her husband was an enemy of Essex, as a result of which Essex was executed. On her deathbed, the countess is said to have confessed this to Elizabeth, who angrily replied: "May God forgive you, Madam, but I never can". The Queen's Diamond Jubilee Galleries in Westminster Abbey possess a gold ring which is claimed to be this one.

Some historians consider this story of the ring to be a myth, partly because there are no contemporaneous accounts of it. John Lingard in his history of England says the story appears to be fiction, Lytton Strachey states "Such a narrative is appropriate enough to the place where it was first fully elaborated — a sentimental novelette, but it does not belong to history", and Alison Weir calls it a fabrication.

Nevertheless, this version of the story forms the basis of the plot of Gaetano Donizetti

Domenico Gaetano Maria Donizetti (29 November 1797 – 8 April 1848) was an Italian composer, best known for his almost 70 operas. Along with Gioachino Rossini and Vincenzo Bellini, he was a leading composer of the '' bel canto'' opera style dur ...

's opera '' Roberto Devereux'', with a further twist added to the story, in that Essex is cheating on both the Queen and his best friend by having an affair with Lady Nottingham (who in the opera is given the wrong first name of Sarah rather than Catherine): and that this turns out to be (a) the reason why Lord Nottingham turns against his now former friend, when he discovers the ring in question and prevents her sending it, and (b) is the ultimate reason for Queen Elizabeth withdrawing her support for Essex at his trial. The actual question of Devereux's genuine guilt or innocence is sidelined (as is his actual failed rebellion), and the trial is presented as effectively a Parliamentary witch-hunt led by Cecil and Raleigh.

Poetry

Like many other Elizabethan aristocrats Essex was a competent lyric poet, who also participated in court entertainments. He engaged in literary as well as political feuds with his principal enemies, including Walter Raleigh. His poem " Muses no more but mazes" attacks Raleigh's influence over the queen.Steven W. May, "The poems of Edward de Vere, seventeenth Earl of Oxford and Robert Devereux, second Earl of Essex" in Studies in Philology, 77 (Winter 1980), Chapel Hill, p.86 ff. Other lyrics were written for masques, including the sonnet " Seated between the old world and the new" in praise of the queen as the moral power linking Europe and America, who supports "the world oppressed" like the mythical Atlas. During his disgrace, he also wrote several bitter and pessimistic verses. His longest poem, " The Passion of a Discontented Mind" (beginning "From silent night..."), is a penitential lament, probably written while imprisoned awaiting execution. Several of Essex's poems were set to music. English composer John Dowland set a poem called " Can she excuse my wrongs with virtue's cloak?" in his 1597 publication ''First Booke of Songs'': these lyrics have been attributed to Essex, largely on the basis of the dedication of "The Earl of Essex's Galliard", an instrumental version of the same song. Dowland also sets the opening verses of Essex's poem "The Passion of a Discontented Mind" ("From silent night") in his 1612 collection of songs. Orlando Gibbons set lines from the poem in the same year. Settings of Essex's poems " Change thy minde" (set by Richard Martin) and " To plead my faith" (set by Daniel Bacheler) are published in ''A Musicall Banquet'' (1610), a collection of songs edited by Robert Dowland.Portrayals

There have been many portrayals of Essex throughout the years;Opera

*Saverio Mercadante

Giuseppe Saverio Raffaele Mercadante (baptised 17 September 179517 December 1870) was an Italian composer, particularly of operas. While Mercadante may not have retained the international celebrity of Gaetano Donizetti or Gioachino Rossini beyond ...

's 1833 opera ''Il Conte d'Essex'' with libretto

A libretto (Italian for "booklet") is the text used in, or intended for, an extended musical work such as an opera, operetta, masque, oratorio, cantata or Musical theatre, musical. The term ''libretto'' is also sometimes used to refer to the t ...

by Felice Romani

* Gaetano Donizetti

Domenico Gaetano Maria Donizetti (29 November 1797 – 8 April 1848) was an Italian composer, best known for his almost 70 operas. Along with Gioachino Rossini and Vincenzo Bellini, he was a leading composer of the '' bel canto'' opera style dur ...

's 1837 opera '' Roberto Devereux'' with libretto by Salvadore Cammarano based mainly on François Ancelot

François () is a French masculine given name and surname, equivalent to the English name Francis.

People with the given name

* Francis I of France, King of France (), known as "the Father and Restorer of Letters"

* Francis II of France, Kin ...

's ''Elisabeth d'Angleterre''.

* Benjamin Britten's 1953 opera '' Gloriana'' is based on Lytton Strachey's ''Elizabeth and Essex''.

Stage

* In the 1956 essay ''Hamlet oder Hekuba: der Einbruch der Zeit in das Spiel'' (Hamlet or Hecuba: the Irruption of Time into the Play), the German legal theorist Carl Schmitt suggests that elements of the Earl's biography, in particular his final days and last words, were incorporated into William Shakespeare's '' Hamlet'' at both the level of dialogue and the level of characterisation. Schmitt's overall argument investigates the relationship between history and narrative generally. * Essex is briefly alluded to in Shakespeare's '' Henry V'' at 5.0.22–34. * Essex is said by editor David L. Stevenson to be alluded to in '' Much Ado About Nothing'' at 3.1.10–11. * Gautier Coste de La Calprenède, ''Le Comte d'Essex'' (1639). * Thomas Corneille, ''Le Comte d'Essex'' (1678). * Claude Boyer, ''Le Comte d'Essex, tragedie. Par Monsieur Boyer de l'Academie françoise'' (1678). *John Banks John Banks or Bankes may refer to:

Politics and law

*Sir John Banks, 1st Baronet (1627–1699), English merchant and Member of Parliament

* John Banks (American politician) (1793–1864), U.S. Representative from Pennsylvania

*John Gray Banks (188 ...

, '' The Unhappy Favourite; Or the Earl of Essex, a Tragedy'' (1682).

* The night of Essex's execution is dramatised in the Timothy Findley play ''Elizabeth Rex

''Elizabeth Rex'' is a play by Timothy Findley. It premiered in a 2000 production by the Stratford Festival. The play won the 2000 Governor General's Award for English language drama.

Plot

The plot involves a meeting between Queen Elizabet ...

''.

* Essex is the love interest in ''La Reine Elizabeth'', play by Émile Moreau, 1912, starring Sarah Bernhardt

Sarah Bernhardt (; born Henriette-Rosine Bernard; 22 or 23 October 1844 – 26 March 1923) was a French stage actress who starred in some of the most popular French plays of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including '' La Dame Aux Camel ...

.

Film

* The 1939 film '' The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex'', starring Bette Davis and Errol Flynn, dramatised the Queen's relationship with Devereux; it is based on Maxwell Anderson's 1930 play '' Elizabeth the Queen'' and Lytton Strachey's romantic account ''Elizabeth and Essex.'' * Their relationship also provided material during the silent era, as in the 1912 film '' Les Amours de la reine Élisabeth'' (''The Loves of Queen Elizabeth''), withSarah Bernhardt

Sarah Bernhardt (; born Henriette-Rosine Bernard; 22 or 23 October 1844 – 26 March 1923) was a French stage actress who starred in some of the most popular French plays of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including '' La Dame Aux Camel ...

as the queen and Lou Tellegen

Lou Tellegen (born Isidor Louis Bernard Edmon van Dommelen;"Lou Tellegen, Idol of Stage and Silent Screen, Stabs Himself Seven Times." Spartanburg (SC) Herald, October 30, 1934, pp. 1-2. November 26, 1881 or 1883 – October 29, 1934) was a ...

as Essex.

* Essex was played by Sam Reid in the 2011 film ''Anonymous

Anonymous may refer to:

* Anonymity, the state of an individual's identity, or personally identifiable information, being publicly unknown

** Anonymous work, a work of art or literature that has an unnamed or unknown creator or author

* Anonym ...

'', a fictional biopic that posits that Edward de Vere

Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford (; 12 April 155024 June 1604) was an English peer and courtier of the Elizabethan era. Oxford was heir to the second oldest earldom in the kingdom, a court favourite for a time, a sought-after patron o ...

, the 17th Earl of Oxford

Earl of Oxford is a dormant title in the Peerage of England, first created for Aubrey de Vere by the Empress Matilda in 1141. His family was to hold the title for more than five and a half centuries, until the death of the 20th Earl in 1703. ...

, was the true author of William Shakespeare's plays and where both Essex and the Earl of Southampton are the illegitimate sons of Queen Elizabeth (the latter also being de Vere's son who is also stated by Robert Cecil to have been Elizabeth's first bastard, making Southampton the product of incest)

TV

*Charlton Heston

Charlton Heston (born John Charles Carter; October 4, 1923April 5, 2008) was an American actor and political activist.

As a Hollywood star, he appeared in almost 100 films over the course of 60 years. He played Moses in the epic film ''The Ten C ...

portrayed the Earl of Essex opposite Judith Anderson's Elizabeth I in a 1968 television adaption of Maxwell Anderson's '' Elizabeth the Queen'', for the Hallmark Hall of Fame

''Hallmark Hall of Fame'', originally called ''Hallmark Television Playhouse'', is an anthology program on American television, sponsored by Hallmark Cards, a Kansas City-based greeting card company. The longest-running prime-time series in t ...

series.

* The Earl of Essex was portrayed by Robin Ellis in the fifth and sixth episodes of the BBC series ''Elizabeth R

''Elizabeth R'' is a BBC television drama serial of six 85-minute plays starring Glenda Jackson as Queen Elizabeth I of England. It was first broadcast on BBC2 from February to March 1971, through the ABC in Australia and broadcast in America ...

'' (1971) starring Glenda Jackson as Elizabeth I.

* The Queen's relationship with Essex (played by Hugh Dancy) and his stepfather Leicester (played by Jeremy Irons) was also covered by a 2005 Channel 4/HBO

Home Box Office (HBO) is an American premium television network, which is the flagship property of namesake parent subsidiary Home Box Office, Inc., itself a unit owned by Warner Bros. Discovery. The overall Home Box Office business unit is ba ...

co-production '' Elizabeth I'', starring Helen Mirren

Dame Helen Mirren (born Helen Lydia Mironoff; born 26 July 1945) is an English actor. The recipient of numerous accolades, she is the only performer to have achieved the Triple Crown of Acting in both the United States and the United Kingdom. ...

.

* In the 2005 '' The Virgin Queen'', Hans Matheson played the ill-fated Earl of Essex.

* In the 2017 BBC documentary mini-series ''Elizabeth I's Secret Agents'', the Earl of Essex was portrayed by Joe Wredden

Joe or JOE may refer to:

Arts

Film and television

* ''Joe'' (1970 film), starring Peter Boyle

* ''Joe'' (2013 film), starring Nicolas Cage

* ''Joe'' (TV series), a British TV series airing from 1966 to 1971

* ''Joe'', a 2002 Canadian animated ...

.

Essex in literature

At least two fencing treatises are dedicated to Robert, Earl of Essex. They are as follows: * Vincentio Saviolo – ''His Practice'' (1595) * George Silver – ''Paradoxes of Defence'' (1599) Robert Devereux's death and confession became the subject of two popular 17th-century broadside ballads, set to the Englishfolk tune

Folk music is a music genre that includes traditional folk music and the contemporary genre that evolved from the former during the 20th-century folk revival. Some types of folk music may be called world music. Traditional folk music has b ...

s ''Essex Last Goodnight'' and ''Welladay''. Numerous ballads lamenting his death and praising his military feats were also published throughout the 17th century.

Notes

References

* Bagwell, Richard: ''Ireland under the Tudors'' 3 vols. (London, 1885–1890). * Cadwallader, Laura Hanes''The Career of the Earl of Essex from the Islands Voyage in 1597 to His Execution in 1601''

Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1923. . * Dickinson, Janet, ''Court Politics and the Earl of Essex, 1589-1601'' (Routledge: Abingdon, 2016). * Ellis, Steven G.: ''Tudor Ireland'' (London, 1985). . * Falls, Cyril: ''Elizabeth's Irish Wars'' (1950; reprint London, 1996). . * * Lacey, Robert: ''Robert, Earl of Essex: An Elizabethan Icarus'' (Weidenfeld & Nicolson 1971) * * Shapiro, James: ''1599: A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare'' (London, 2005) . * Smith, Lacey Baldwin: ''Treason in Tudor England: Politics & Paranoia'' (Pimlico 2006) *

External links

*English Broadside Ballad Archive

, - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Essex, Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl Of 1565 births 1601 deaths 16th-century English nobility 17th-century English nobility Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge 09 12 British and English royal favourites Burials at the Church of St Peter ad Vincula Chancellors of the University of Cambridge Chancellors of the University of Dublin Robert Earls Marshal 3 English people of the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604) English politicians convicted of crimes English rebels Executions at the Tower of London Executed people from Herefordshire Knights of the Garter Lords Lieutenant of Ireland People executed by Tudor England by decapitation People executed under Elizabeth I People executed under the Tudors for treason against England People from Bromyard People of Elizabethan Ireland People of the Elizabethan era People of the Nine Years' War (Ireland) Treason trials