Women's rights are the

rights

Rights are legal, social, or ethical principles of freedom or entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal system, social convention, or ethical theory ...

and

entitlement

An entitlement is a provision made in accordance with a legal framework of a society. Typically, entitlements are based on concepts of principle ("rights") which are themselves based in concepts of social equality or enfranchisement.

In psycholo ...

s claimed for

women

A woman is an adult female human. Prior to adulthood, a female human is referred to as a girl (a female child or Adolescence, adolescent). The plural ''women'' is sometimes used in certain phrases such as "women's rights" to denote female hum ...

and

girl

A girl is a young female human, usually a child or an adolescent. When a girl becomes an adult, she is accurately described as a ''woman''. However, the term ''girl'' is also used for other meanings, including ''young woman'',Dictionary.c ...

s worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the

feminist movement

The feminist movement (also known as the women's movement, or feminism) refers to a series of social movements and political campaigns for radical and liberal reforms on women's issues created by the inequality between men and women. Such ...

s during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countries, these rights are institutionalized or supported by law, local custom, and behavior, whereas in others, they are ignored and suppressed. They differ from broader notions of

human rights

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hu ...

through claims of an inherent historical and traditional bias against the exercise of rights by women and girls, in favor of men and boys.

[Hosken, Fran P., 'Towards a Definition of Women's Rights' in ''Human Rights Quarterly'', Vol. 3, No. 2. (May 1981), pp. 1–10.]

Issues commonly associated with notions of women's rights include the right to

bodily integrity

Bodily integrity is the inviolability of the physical body and emphasizes the importance of personal autonomy, self-ownership, and self-determination of human beings over their own bodies. In the field of human rights, violation of the bodily int ...

and

autonomy

In developmental psychology and moral, political, and bioethical philosophy, autonomy, from , ''autonomos'', from αὐτο- ''auto-'' "self" and νόμος ''nomos'', "law", hence when combined understood to mean "one who gives oneself one' ...

, to be free from

sexual violence

Sexual violence is any sexual act or attempt to obtain a sexual act by violence or coercion, act to traffic a person, or act directed against a person's sexuality, regardless of the relationship to the victim.World Health Organization., World re ...

, to

vote

Voting is a method by which a group, such as a meeting or an electorate, can engage for the purpose of making a collective decision or expressing an opinion usually following discussions, debates or election campaigns. Democracies elect holde ...

, to hold public office, to enter into legal contracts, to have equal rights in

family law

Family law (also called matrimonial law or the law of domestic relations) is an area of the law that deals with family matters and domestic relations.

Overview

Subjects that commonly fall under a nation's body of family law include:

* Marriage ...

,

to work, to fair wages or

equal pay

Equal pay for equal work is the concept of labour rights that individuals in the same workplace be given equal pay. It is most commonly used in the context of sexual discrimination, in relation to the gender pay gap. Equal pay relates to the full ...

, to have

reproductive rights

Reproductive rights are legal rights and freedoms relating to reproduction and reproductive health that vary amongst countries around the world. The World Health Organization defines reproductive rights as follows:

Reproductive rights rest o ...

, to

own property, and

to education.

[Lockwood, Bert B. (ed.), ''Women's Rights: A "Human Rights Quarterly" Reader'' (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006), .]

History

Ancient history

Mesopotamia

Women in ancient

Sumer

Sumer () is the earliest known civilization in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia (south-central Iraq), emerging during the Chalcolithic and early Bronze Ages between the sixth and fifth millennium BC. It is one of the cradles of ...

could buy, own, sell, and inherit property.

They could engage in commerce,

[ and testify in court as witnesses.][ Nonetheless, their husbands could ]divorce

Divorce (also known as dissolution of marriage) is the process of terminating a marriage or marital union. Divorce usually entails the canceling or reorganizing of the legal duties and responsibilities of marriage, thus dissolving th ...

them for mild infractions,[ and a divorced husband could easily remarry another woman, provided that his first wife had borne him no offspring.][ Female deities, such as ]Inanna

Inanna, also sux, 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒀭𒈾, nin-an-na, label=none is an ancient Mesopotamian goddess of love, war, and fertility. She is also associated with beauty, sex, divine justice, and political power. She was originally worshiped in Su ...

, were widely worshipped.Akkadian Akkadian or Accadian may refer to:

* Akkadians, inhabitants of the Akkadian Empire

* Akkadian language, an extinct Eastern Semitic language

* Akkadian literature, literature in this language

* Akkadian cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo-syllabic ...

poet Enheduanna

Enheduanna ( sux, , also transliterated as , , or variants) was the priestess of the moon god Nanna (Sīn) in the Sumerian city-state of Ur in the reign of her father, Sargon of Akkad. She was likely appointed by her father as the leader of t ...

, the priestess of Inanna and daughter of Sargon, is the earliest known poet whose name has been recorded. Old Babylonian law codes permitted a husband to divorce his wife under any circumstances,[ but doing so required him to return all of her property and sometimes pay her a fine.][ Most law codes forbade a woman to request her husband for a divorce and enforced the same penalties on a woman asking for divorce as on a woman caught in the act of ]adultery

Adultery (from Latin ''adulterium'') is extramarital sex that is considered objectionable on social, religious, moral, or legal grounds. Although the sexual activities that constitute adultery vary, as well as the social, religious, and legal ...

.[ Some Babylonian and ]Assyria

Assyria ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the A ...

n laws, however, afforded women the same right to divorce as men, requiring them to pay exactly the same fine.[ The majority of ]East Semitic

The East Semitic languages are one of three divisions of the Semitic languages. The East Semitic group is attested by three distinct languages, Akkadian, Eblaite and possibly Kishite, all of which have been long extinct. They were influenced b ...

deities were male.[

]

Egypt

In ancient Egypt, women enjoyed the same rights under the law as a man, however rightful entitlements depended upon

In ancient Egypt, women enjoyed the same rights under the law as a man, however rightful entitlements depended upon social class

A social class is a grouping of people into a set of hierarchical social categories, the most common being the upper, middle and lower classes. Membership in a social class can for example be dependent on education, wealth, occupation, inc ...

. Landed property descended in the female line from mother to daughter, and women were entitled to administer their own property. Women in ancient Egypt could buy, sell, be a partner in legal contract

A contract is a legally enforceable agreement between two or more parties that creates, defines, and governs mutual rights and obligations between them. A contract typically involves the transfer of goods, services, money, or a promise to t ...

s, be executors in wills and witnesses to legal documents, bring court action, and adopt children.

India

Women during the early Vedic period

The Vedic period, or the Vedic age (), is the period in the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age of the history of India when the Vedic literature, including the Vedas (ca. 1300–900 BCE), was composed in the northern Indian subcontinent, betwe ...

[Details.]

/ref> Works by ancient Indian grammarians such as Patanjali

Patanjali ( sa, पतञ्जलि, Patañjali), also called Gonardiya or Gonikaputra, was a Hindu author, mystic and philosopher. Very little is known about him, and while no one knows exactly when he lived; from analysis of his works it i ...

and Katyayana suggest that women were educated in the early Vedic period. Rigvedic verses suggest that women married at a mature age and were probably free to select their own husbands in a practice called swayamvar

Svayamvara ( sa, स्वयंवर, svayaṃvara, translit-std=IAST), in ancient India, was a method of marriage in which a woman chose a man as her husband from a group of suitors. In this context, in Sanskrit means 'self' and means 'g ...

or live-in relationship called Gandharva marriage

A Gandharva marriage (Sanskrit: गान्धर्व विवाह, ''pronounced gənd̪ʱərvə vɪvaːhə'') (also known as love marriage) is one of the eight classical types of Hindu marriage. This ancient marriage tradition from the Indi ...

.

Greece

Although most women lacked political and equal rights in the city states

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world since the dawn of history, including cities such as ...

of ancient Greece, they enjoyed a certain freedom of movement until the Archaic age.Delphi

Delphi (; ), in legend previously called Pytho (Πυθώ), in ancient times was a sacred precinct that served as the seat of Pythia, the major oracle who was consulted about important decisions throughout the ancient classical world. The orac ...

, Gortyn

Gortyn, Gortys or Gortyna ( el, Γόρτυν, , or , ) is a municipality, and an archaeological site, on the Mediterranean island of Crete away from the island's capital, Heraklion. The seat of the municipality is the village Agioi Deka. Gorty ...

, Thessaly

Thessaly ( el, Θεσσαλία, translit=Thessalía, ; ancient Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic and modern administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, Thes ...

, Megara

Megara (; el, Μέγαρα, ) is a historic town and a municipality in West Attica, Greece. It lies in the northern section of the Isthmus of Corinth opposite the island of Salamis, which belonged to Megara in archaic times, before being take ...

, and Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referr ...

owning land, the most prestigious form of private property

Private property is a legal designation for the ownership of property by non-governmental legal entities. Private property is distinguishable from public property and personal property, which is owned by a state entity, and from collective or ...

at the time. However, after the Archaic age, legislators began to enact laws enforcing gender segregation, resulting in decreased rights for women.Women in Classical Athens

The study of the lives of women in classical Athens has been a significant part of classical scholarship since the 1970s. The knowledge of Athenian women's lives comes from a variety of ancient sources. Much of it is literary evidence, primaril ...

had no legal personhood and were assumed to be part of the ''oikos

The ancient Greek word ''oikos'' (ancient Greek: , plural: ; English prefix: eco- for ecology and economics) refers to three related but distinct concepts: the family, the family's property, and the house. Its meaning shifts even within texts.

The ...

'' headed by the male ''kyrios

''Kyrios'' or ''kurios'' ( grc, κύριος, kū́rios) is a Greek word which is usually translated as "lord" or "master". It is used in the Septuagint translation of the Hebrew scriptures about 7000 times, in particular translating the nam ...

''. Until marriage, women were under the guardianship of their father or another male relative. Once married, the husband became a woman's ''kyrios''. As women were barred from conducting legal proceedings, the ''kyrios'' would do so on their behalf.property

Property is a system of rights that gives people legal control of valuable things, and also refers to the valuable things themselves. Depending on the nature of the property, an owner of property may have the right to consume, alter, share, r ...

through gifts, dowry, and inheritance, though her ''kyrios'' had the right to dispose of a woman's property. Athenian women could only enter into a contract worth less than the value of a "''medimno A medimnos ( el, μέδιμνος, ''médimnos'', plural μέδιμνοι, ''médimnoi'') was an Ancient Greek unit of volume, which was generally used to measure dry food grain.In ancient Greece, measures of capacity varied depending on whether th ...

s'' of barley" (a measure of grain), allowing women to engage in petty trading.Athenian democracy

Athenian democracy developed around the 6th century BC in the Greek city-state (known as a polis) of Athens, comprising the city of Athens and the surrounding territory of Attica. Although Athens is the most famous ancient Greek democratic ci ...

, both in principle and in practice. Slaves could become Athenian citizens after being freed, but no woman ever acquired citizenship in ancient Athens.

In classical Athens

The city of Athens ( grc, Ἀθῆναι, ''Athênai'' .tʰɛ̂ː.nai̯ Modern Greek: Αθήναι, ''Athine'' or, more commonly and in singular, Αθήνα, ''Athina'' .'θi.na during the classical period of ancient Greece (480–323 BC) wa ...

women were also barred from becoming poets, scholars, politicians, or artists.Hellenistic period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

in Athens, the philosopher Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

thought that women would bring disorder and evil, therefore it was best to keep women separate from the rest of the society. This separation would entail living in a room called a '' gynaikeion'', while looking after the duties in the home and having very little exposure to the male world. This was also to ensure that wives only had legitimate children from their husbands. Athenian women received little education, except home tutorship for basic skills such as spinning, weaving, cooking, and some knowledge of money.Spartan

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta refe ...

women were formally excluded from military and political life, they enjoyed considerable status as mothers of Spartan warriors. As men engaged in military activity, women took responsibility for running estates. Following protracted warfare in the 4th century BC, Spartan women owned approximately between 35% and 40% of all Spartan land and property.[Pomeroy, Sarah B. ''Goddess, Whores, Wives, and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity''. New York: Schocken Books, 1975. pp. 60–62.] Girls, as well as boys, received an education.freedom of movement

Freedom of movement, mobility rights, or the right to travel is a human rights concept encompassing the right of individuals to travel from place to place within the territory of a country,Jérémiee Gilbert, ''Nomadic Peoples and Human Rights ...

for Spartan women, their role in politics was the same as Athenian women.Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

acknowledged that extending civil and political rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life ...

to women would substantively alter the nature of the household and the state. Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

, who had been taught by Plato, denied that women were slaves or subject to property, arguing that "nature has distinguished between the female and the slave", but he considered wives to be "bought". He argued that women's main economic activity is that of safeguarding the household property created by men. According to Aristotle, the labour of women added no value because "the art of household management is not identical with the art of getting wealth, for the one uses the material which the other provides".

Contrary to Plato's views, the Stoic philosophers argued for equality of the sexes, sexual inequality being in their view contrary to the laws of nature.

Rome

Roman law, similar to Athenian law, was created by men in favor of men.

Roman law, similar to Athenian law, was created by men in favor of men.[ A. N. Sherwin-White, ''Roman Citizenship'' (Oxford University Press, 1979), pp. 211, 268; Bruce W. Frier and Thomas A.J. McGinn, ''A Casebook on Roman Family Law'' (Oxford University Press, 2004), pp. 31–32, 457, ''et passim''.] Freeborn women of ancient Rome

In modern historiography, ancient Rome refers to Roman people, Roman civilisation from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom ...

were citizens

Citizenship is a "relationship between an individual and a state to which the individual owes allegiance and in turn is entitled to its protection".

Each state determines the conditions under which it will recognize persons as its citizens, and ...

who enjoyed legal privileges and protections that did not extend to non-citizens

In law, an alien is any person (including an organization) who is not a citizen or a national of a specific country, although definitions and terminology differ to some degree depending upon the continent or region. More generally, however, ...

or slaves

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

. Roman society

The culture of ancient Rome existed throughout the almost 1200-year history of the civilization of Ancient Rome. The term refers to the culture of the Roman Republic, later the Roman Empire, which at its peak covered an area from present-day Lo ...

, however, was patriarchal

Patriarchy is a social system in which positions of dominance and privilege are primarily held by men. It is used, both as a technical anthropological term for families or clans controlled by the father or eldest male or group of males ...

, and women could not vote, hold public office

Public Administration (a form of governance) or Public Policy and Administration (an academic discipline) is the implementation of public policy, administration of government establishment ( public governance), management of non-profit estab ...

, or serve in the military. Women of the upper classes exercised political influence through marriage and motherhood. During the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

, the mothers of the Gracchus brothers and of Julius Caesar were noted as exemplary women who advanced the careers of their sons. During the Imperial period, women of the emperor's family could acquire considerable political power and were regularly depicted in official art and on coinage.

The central core of Roman society was the ''pater familias

The ''pater familias'', also written as ''paterfamilias'' (plural ''patres familias''), was the head of a Roman family. The ''pater familias'' was the oldest living male in a household, and could legally exercise autocratic authority over his ext ...

'' or the male head of the household who exercised his authority over all his children, servants, and wife.[David Johnston, ''Roman Law in Context'' (Cambridge University Press, 1999), chapter 3.3; Frier and McGinn, '' A Casebook on Roman Family Law'', Chapter IV; Yan Thomas, "The Division of the Sexes in Roman Law", in ''A History of Women from Ancient Goddesses to Christian Saints'' (Harvard University Press, 1991), p. 134.] Similar to Athenian women, Roman women had a guardian or as it was called "tutor" who managed and oversaw all her activity.ius tritium liberorum

__NOTOC__

''Ius'' or ''Jus'' (Latin, plural ''iura'') in ancient Rome was a right to which a citizen (''civis'') was entitled by virtue of his citizenship (''civitas''). The ''iura'' were specified by laws, so ''ius'' sometimes meant law. As on ...

'' ("legal right of three children") granted symbolic honors and legal privileges to a woman who had given birth to three children and freed her from any male guardianship.

In the earliest period of the Roman Republic, a bride passed from her father's control into the "hand" ''(manus)'' of her husband. She then became subject to her husband's ''potestas'', though to a lesser degree than their children. This archaic form of ''manus'' marriage was largely abandoned by the time of Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

, when a woman remained under her father's authority by law even when she moved into her husband's home. This arrangement was one of the factors in the independence Roman women enjoyed.

Although women had to answer to their fathers in legal matters, they were free of his direct scrutiny in their daily lives, and their husbands had no legal power over them. When a woman's father died, she became legally emancipated ''(sui iuris

''Sui iuris'' ( or ) also spelled ''sui juris'', is a Latin phrase that literally means "of one's own right". It is used in both secular law and the Catholic Church's canon law. The term church ''sui iuris'' is used in the Catholic '' Code of Ca ...

)''. A married woman retained ownership of any property

Property is a system of rights that gives people legal control of valuable things, and also refers to the valuable things themselves. Depending on the nature of the property, an owner of property may have the right to consume, alter, share, r ...

she brought into the marriage.[Frier and McGinn, ''A Casebook on Roman Family Law'', pp. 19–20.] Girls had equal inheritance rights with boys if their father died without leaving a will.Roman law

Roman law is the legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (c. 449 BC), to the '' Corpus Juris Civilis'' (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor J ...

, a husband had no right to abuse his wife physically or compel her to have sex. Wife beating was sufficient grounds for divorce or other legal action against the husband.

Because of their legal status as citizens and the degree to which they could become emancipated, women in ancient Rome could own property, enter contracts, and engage in business. Some acquired and disposed of sizable fortunes, and are recorded in inscriptions as benefactors in funding major public works. Roman women could appear in court and argue cases, though it was customary for them to be represented by a man. They were simultaneously disparaged as too ignorant and weak-minded to practice law, and as too active and influential in legal matters—resulting in an edict that limited women to conducting cases on their own behalf instead of others'. But even after this restriction was put in place, there are numerous examples of women taking informed actions in legal matters, including dictating legal strategy to their male advocates.

Roman law recognized rape

Rape is a type of sexual assault usually involving sexual intercourse or other forms of sexual penetration carried out against a person without their consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, coercion, abuse of authority, or ...

as a crime in which the victim bore no guilt and a capital crime. The rape of a woman was considered an attack on her family and father's honour, and rape victims were shamed for allowing the bad name in her father's honour. The first Roman emperor,

The first Roman emperor, Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

, framed his ascent to sole power as a return to traditional morality, and attempted to regulate the conduct of women through moral legislation. Adultery

Adultery (from Latin ''adulterium'') is extramarital sex that is considered objectionable on social, religious, moral, or legal grounds. Although the sexual activities that constitute adultery vary, as well as the social, religious, and legal ...

, which had been a private family matter under the Republic, was criminalized, and defined broadly as an illicit sex act ''( stuprum)'' that occurred between a male citizen and a married woman, or between a married woman and any man other than her husband. Therefore, a married woman could have sex only with her husband, but a married man did not commit adultery when he had sex with a prostitute, slave

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, or person of marginalized status ''( infamis)''. Most prostitutes in ancient Rome were slaves, though some slaves were protected from forced prostitution by a clause in their sales contract. A free woman who worked as a prostitute or entertainer lost her social standing and became '' infamis'', "disreputable"; by making her body publicly available, she had in effect surrendered her right to be protected from sexual abuse or physical violence.

Stoic philosophies influenced the development of Roman law. Stoics of the Imperial era such as Seneca and Musonius Rufus

Gaius Musonius Rufus (; grc-gre, Μουσώνιος Ῥοῦφος) was a Roman Stoic philosopher of the 1st century AD. He taught philosophy in Rome during the reign of Nero and so was sent into exile in 65 AD, returning to Rome only under Galb ...

developed theories of just relationships. While not advocating equality in society or under the law, they held that nature gives men and women equal capacity for virtue and equal obligations to act virtuously, and that therefore men and women had an equal need for philosophical education.Hypatia of Alexandria

Hypatia, Koine pronunciation (born 350–370; died 415 AD) was a neoplatonist philosopher, astronomer, and mathematician, who lived in Alexandria, Egypt, then part of the Eastern Roman Empire. She was a prominent thinker in Alexandria wher ...

, who taught advanced courses to young men and advised the Roman prefect of Egypt

During the Roman Empire, the governor of Roman Egypt ''(praefectus Aegypti)'' was a prefect who administered the Egypt (Roman province), Roman province of Egypt with the delegated authority ''(imperium)'' of the Roman emperor, emperor.

Egypt was ...

on politics. Her influence put her into conflict with the bishop of Alexandria, Cyril

Cyril (also Cyrillus or Cyryl) is a masculine given name. It is derived from the Greek name Κύριλλος (''Kýrillos''), meaning 'lordly, masterful', which in turn derives from Greek κυριος (''kýrios'') 'lord'. There are various varian ...

, who may have been implicated in her violent death in the year 415 at the hands of a Christian mob.

Byzantine Empire

Since Byzantine law was essentially based on Roman law, the legal status of women did not change significantly from the practices of the 6th century. But the traditional restriction of women in public life as well as the hostility against independent women still continued.Justinian

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized '' renova ...

. Second marriages were discouraged, especially by making it legal to impose a condition that a widow's right to property should cease on remarriage, and the Leonine Constitutions

Leonine may refer to:

Lions

* Leonine facies, a face that resembles that of a lion

Popes Leo

* Leonine City, a part of the city of Rome

* Leonine College, a college for priests in training, in Rome, Italy

* Leonine Prayers, a set of prayers tha ...

at the end of the 9th century made third marriages punishable. The same constitutions made the benediction of a priest a necessary part of the ceremony of marriage.

China

Women throughout historical and ancient China were considered inferior and had subordinate legal status based on Confucian law.

Women throughout historical and ancient China were considered inferior and had subordinate legal status based on Confucian law.foot binding

Foot binding, or footbinding, was the Chinese custom of breaking and tightly binding the feet of young girls in order to change their shape and size. Feet altered by footbinding were known as lotus feet, and the shoes made for these feet were kno ...

. About 45% of Chinese women had bound feet in the 19th century. For the upper classes, it was almost 100%. In 1912, the Chinese government ordered the cessation of foot-binding. Foot-binding involved the alteration of the bone structure so that the feet were only about four inches long. The bound feet caused difficulty in movement, thus greatly limiting the activities of women.

Due to the social custom that men and women should not be near each other, the women of China were reluctant to be treated by male doctors of Western Medicine. This resulted in a tremendous need for female doctors of Western Medicine in China. Thus, female medical missionary Dr. Mary H. Fulton (1854–1927) was sent by the Foreign Missions Board of the Presbyterian Church (USA) to found the first medical college for women in China. Known as the Hackett Medical College for Women (夏葛女子醫學院), the college was enabled in Guangzhou, China, by a large donation from Edward A.K. Hackett (1851–1916) of Indiana, US. The college was aimed at the spreading of Christianity and modern medicine and the elevation of Chinese women's social status.[Rebecca Chan Chung, Deborah Chung and Cecilia Ng Wong, "Piloted to Serve", 2012.]

During the Republic of China (1912–49)

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northea ...

and earlier Chinese governments, women were legally bought and sold into slavery under the guise of domestic servants. These women were known as Mui Tsai. The lives of Mui Tsai were recorded by American feminist Agnes Smedley

Agnes Smedley (February 23, 1892 – May 6, 1950) was an American journalist, writer, and activist who supported the Indian Independence Movement and the Chinese Communist Revolution. Raised in a poverty-stricken miner's family in Missouri and Co ...

in her book ''Portraits of Chinese Women in Revolution''.

However, in 1949 the Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeas ...

was overthrown by communist guerillas led by Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also Romanization of Chinese, romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the List of national founde ...

, and the People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

was founded in the same year. In May 1950 the People's Republic of China enacted the New Marriage Law to tackle the sale of women into slavery. This outlawed marriage by proxy and made marriage legal so long as both partners consent. The New Marriage Law raised the legal age of marriage to 20 for men and 18 for women. This was an essential part of countryside land reform as women could no longer legally be sold to landlords. The official slogan was "Men and women are equal; everyone is worth his (or her) salt".

Post-classical history

Religious scriptures

= Bible

=

Both before and during biblical times, the roles of women in society were severely restricted. Nonetheless, in the Bible, women are depicted as having the right to represent themselves in court,[ Breach of these Old Testament rights by a polygamous man gave the woman grounds for divorce:][ "If he marries another woman, he must not deprive the first one of her food, clothing and marital rights. If he does not provide her with these three things, she is to go free, without any payment of money" ().

]

= Qur'an

=

The Qur'an

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , si ...

, which Muslims believe was revealed

Reveal or Revealed may refer to:

People

* Reveal (rapper) (born 1983), member of the British hip hop group Poisonous Poets

* James L. Reveal (1941–2015), American botanist

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''Revealed'', a 2013 novel ...

to Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mon ...

over the course of 23 years, provided guidance to the Islamic community and modified existing customs in Arab society. The Qur'an prescribes limited rights for women in marriage

Marriage, also called matrimony or wedlock, is a culturally and often legally recognized union between people called spouses. It establishes rights and obligations between them, as well as between them and their children, and between ...

, divorce

Divorce (also known as dissolution of marriage) is the process of terminating a marriage or marital union. Divorce usually entails the canceling or reorganizing of the legal duties and responsibilities of marriage, thus dissolving th ...

, and inheritance

Inheritance is the practice of receiving private property, titles, debts, entitlements, privileges, rights, and obligations upon the death of an individual. The rules of inheritance differ among societies and have changed over time. Of ...

. By providing that the wife, not her family, would receive a dowry from the husband, which she could administer as her personal property, the Qur'an made women a legal party to the marriage contract

''Marriage Contract'' () is a 2016 South Korean television series starring Lee Seo-jin and Uee. It aired on MBC from March 5 to April 24, 2016 on Saturdays and Sundays at 22:00 for 16 episodes.

Plot

Kang Hye-soo (Uee) is a single mother who ...

.

While in customary law, inheritance was often limited to male descendants, the Qur'an included rules on inheritance with certain fixed shares being distributed to designated heirs, first to the nearest female relatives and then the nearest male relatives. According to Annemarie Schimmel

Annemarie Schimmel (7 April 1922 – 26 January 2003) was an influential German Orientalist and scholar who wrote extensively on Islam, especially Sufism. She was a professor at Harvard University from 1967 to 1992.

Early life and education

...

"compared to the pre-Islamic position of women, Islamic legislation meant an enormous progress; the woman has the right, at least according to the letter of the law

The letter of the law and the spirit of the law are two possible ways to regard rules, or laws. To obey the letter of the law is to follow the literal reading of the words of the law, whereas following the spirit of the law means enacting the ...

, to administer the wealth she has brought into the family or has earned by her own work."

For Arab women, Islam included the prohibition of female infanticide

Female infanticide is the deliberate killing of newborn female children. In countries with a history of female infanticide, the modern practice of gender-selective abortion is often discussed as a closely related issue. Female infanticide is a m ...

and recognizing women's full personhood.[Esposito (2004), p. 339.] Women generally gained greater rights than women in pre-Islamic Arabia

Pre-Islamic Arabia ( ar, شبه الجزيرة العربية قبل الإسلام) refers to the Arabian Peninsula before the emergence of Islam in 610 CE.

Some of the settled communities developed into distinctive civilizations. Informatio ...

John Esposito

John Louis Esposito (born May 19, 1940) is an Italian-American academic, professor of Middle Eastern and religious studies, and scholar of Islamic studies, who serves as Professor of Religion, International Affairs, and Islamic Studies at Ge ...

, ''Islam: The Straight Path'' p. 79.Majid Khadduri

Majid Khadduri (Arabic: مجيد خدوري) (September 27, 1909 – January 25, 2007) was an Iraqi–born academic. He was founder of the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies Middle East Studies program, a division of John ...

, ''Marriage in Islamic Law: The Modernist Viewpoints'', American Journal of Comparative law

Comparative law is the study of differences and similarities between the law (legal systems) of different countries. More specifically, it involves the study of the different legal "systems" (or "families") in existence in the world, including the ...

, Vol. 26, No. 2, pp. 213–18.medieval Europe

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

. Women were not accorded such legal status in other cultures until centuries later. According to Professor William Montgomery Watt

William Montgomery Watt (14 March 1909 – 24 October 2006) was a Scottish Orientalist, historian, academic and Anglican priest. From 1964 to 1979, he was Professor of Arabic and Islamic studies at the University of Edinburgh.

Watt was one ...

, when seen in such a historical context, Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mon ...

"can be seen as a figure who testified on behalf of women's rights."

Western Europe

Women's rights were protected already by the early Medieval Christian Church: one of the first formal legal provisions for the right of wives was promulgated by council of Adge in 506, which in Canon XVI stipulated that if a young married man wished to be ordained, he required the consent of his wife.

The English Church and culture in the Middle Ages regarded women as weak, irrational, vulnerable to temptation, and constantly needing to be kept in check.

Women's rights were protected already by the early Medieval Christian Church: one of the first formal legal provisions for the right of wives was promulgated by council of Adge in 506, which in Canon XVI stipulated that if a young married man wished to be ordained, he required the consent of his wife.

The English Church and culture in the Middle Ages regarded women as weak, irrational, vulnerable to temptation, and constantly needing to be kept in check.Adam and Eve

Adam and Eve, according to the creation myth of the Abrahamic religions, were the first man and woman. They are central to the belief that humanity is in essence a single family, with everyone descended from a single pair of original ancestors. ...

where Eve fell to Satan's temptations and led Adam to eat the apple. This belief was based on St. Paul, that the pain of childbirth was a punishment for this deed that led mankind to be banished from the Garden of Eden.Jacques de Vitry

Jacques de Vitry (''Jacobus de Vitriaco'', c. 1160/70 – 1 May 1240) was a French canon regular who was a noted theologian and chronicler of his era.

He was elected bishop of Acre in 1214 and made cardinal in 1229.

His ''Historia Orientali ...

(who was rather sympathetic to women over others) emphasized female obedience towards their men and described women as slippery, weak, untrustworthy, devious, deceitful and stubborn.Virgin Mary

Mary; arc, ܡܪܝܡ, translit=Mariam; ar, مريم, translit=Maryam; grc, Μαρία, translit=María; la, Maria; cop, Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ, translit=Maria was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Joseph and the mother of ...

as a role model for women to emulate by being innocent in her sexuality, being married to a husband and eventually becoming a mother. That was the core purpose set out both culturally and religiously across Medieval Europe. In overall Europe during the Middle Ages, women were inferior to men in legal status.

In overall Europe during the Middle Ages, women were inferior to men in legal status.The Laws of Hywel Dda

''The'' () is a grammatical Article (grammar), article in English language, English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite ...

, also reflected accountability for men to pay child maintenance for children born out of wedlock, which empowered women to claim rightful payment. In France, women's testimony had to corroborate with other accounts or it would not be accepted.

Northern Europe

The rate of Wergild suggested that women in these societies were valued mostly for their breeding purposes. The Wergild of woman was double that of a man with the same status in the Aleman and Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total l ...

n legal codes.Visigothic

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is ...

inheritance laws until the 7th century were favorable to women while all other laws were not.Harald Bluetooth

Harald "Bluetooth" Gormsson ( non, Haraldr Blátǫnn Gormsson; da, Harald Blåtand Gormsen, died c. 985/86) was a king of Denmark and Norway.

He was the son of King Gorm the Old and of Thyra Dannebod. Harald ruled as king of Denmark from c. 958 ...

of Denmark in the year 950 AD.Norwegian

Norwegian, Norwayan, or Norsk may refer to:

*Something of, from, or related to Norway, a country in northwestern Europe

* Norwegians, both a nation and an ethnic group native to Norway

* Demographics of Norway

*The Norwegian language, including ...

and Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its ...

ic laws used marriages to forge alliances or create peace, usually without the women's say or consent.Viking Age

The Viking Age () was the period during the Middle Ages when Norsemen known as Vikings undertook large-scale raiding, colonizing, conquest, and trading throughout Europe and reached North America. It followed the Migration Period and the Germ ...

, women had a relatively free status in the Nordic countries of Sweden, Denmark and Norway, illustrated in the Icelandic Grágás

The Gray (Grey) Goose Laws ( is, Grágás {{IPA-is, ˈkrauːˌkauːs}) are a collection of laws from the Icelandic Commonwealth period. The term ''Grágás'' was originally used in a medieval source to refer to a collection of Norwegian laws an ...

and the Norwegian Frostating

The Frostating was an early Norwegian court. It was one of the four major Thing (assembly), Things in medieval Norway. The Frostating had its seat at Tinghaugen in what is now the municipality of Frosta in Trøndelag county, Norway. The name ...

laws and Gulating

Gulating ( non, Gulaþing) was one of the first Norwegian legislative assemblies, or '' things,'' and also the name of a present-day law court of western Norway. The practice of periodic regional assemblies predates recorded history, and was ...

laws.[Borgström Eva : Makalösa kvinnor: könsöverskridare i myt och verklighet (Marvelous women : gender benders in myth and reality) Alfabeta/Anamma, Stockholm 2002. (inb.). Libris 8707902.]

The paternal aunt, paternal niece and paternal granddaughter, referred to as ''odalkvinna'', all had the right to inherit property from a deceased man.ringkvinna Baugrygr or Ringkvinna was the term referred to an unmarried woman who had inherited the position of head of the family, usually from her father or brother, with all the tasks and rights associated with the position. The position existed in Scandi ...

'', and she exercised all the rights afforded to the head of a family clan, such as the right to demand and receive fines for the slaughter of a family member, unless she married, by which her rights were transferred to her husband.[Ingelman-Sundberg, Catharina, ''Forntida kvinnor: jägare, vikingahustru, prästinna'' ncient women: hunters, viking wife, priestess Prisma, Stockholm, 2004] within art as poets (''skalder'')rune master

A runemaster or runecarver is a specialist in making runestones.

Description

More than 100 names of runemasters are known from Viking Age Sweden with most of them from 11th-century eastern Svealand.The article ''Runristare'' in ''Nationalencyklo ...

s; and as merchants and medicine women.shieldmaiden

A shield-maiden ( non, skjaldmær ) was a female warrior from Scandinavian folklore and mythology.

Shield-maidens are often mentioned in sagas such as ''Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks'' and in ''Gesta Danorum''. They also appear in stories of other ...

s are unconfirmed, but some archaeological finds such as the Birka female Viking warrior

The Birka female Viking warrior was a woman buried with the accoutrements of an elite professional Viking warrior in a 10th century chamber-grave in Birka, Sweden. Although the remains were thought to be of a male warrior since the grave's excav ...

may indicate that at least some women in military authority existed. A married woman could divorce her husband and remarry.[Ohlander, Ann-Sofie & Strömberg, Ulla-Britt, Tusen svenska kvinnoår: svensk kvinnohistoria från vikingatid till nutid, 3. (A Thousand Swedish Women's Years: Swedish Women's History from the Viking Age until now), marb. och utök.uppl., Norstedts akademiska förlag, Stockholm, 2008]

It was also socially acceptable for a free woman to cohabit with a man and have children with him without marrying him, even if that man was married; a woman in such a position was called ''frilla''.[Borgström Eva : ''Makalösa kvinnor: könsöverskridare i myt och verklighet'' (''Marvelous women : genderbenders in myth and reality'') Alfabeta/Anamma, Stockholm 2002. (inb.). Libris 8707902.] During the Christian Middle Ages, the Medieval Scandinavian law

Medieval Scandinavian law, also called North Germanic law, was a subset of Germanic law practiced by North Germanic peoples. It was originally memorized by lawspeakers, but after the end of the Viking Age they were committed to writing, mostly by ...

applied different laws depending on the local county law, signifying that the status of women could vary depending on which county she was living in.

Modern history

Europe

= 16th and 17th century Europe

=

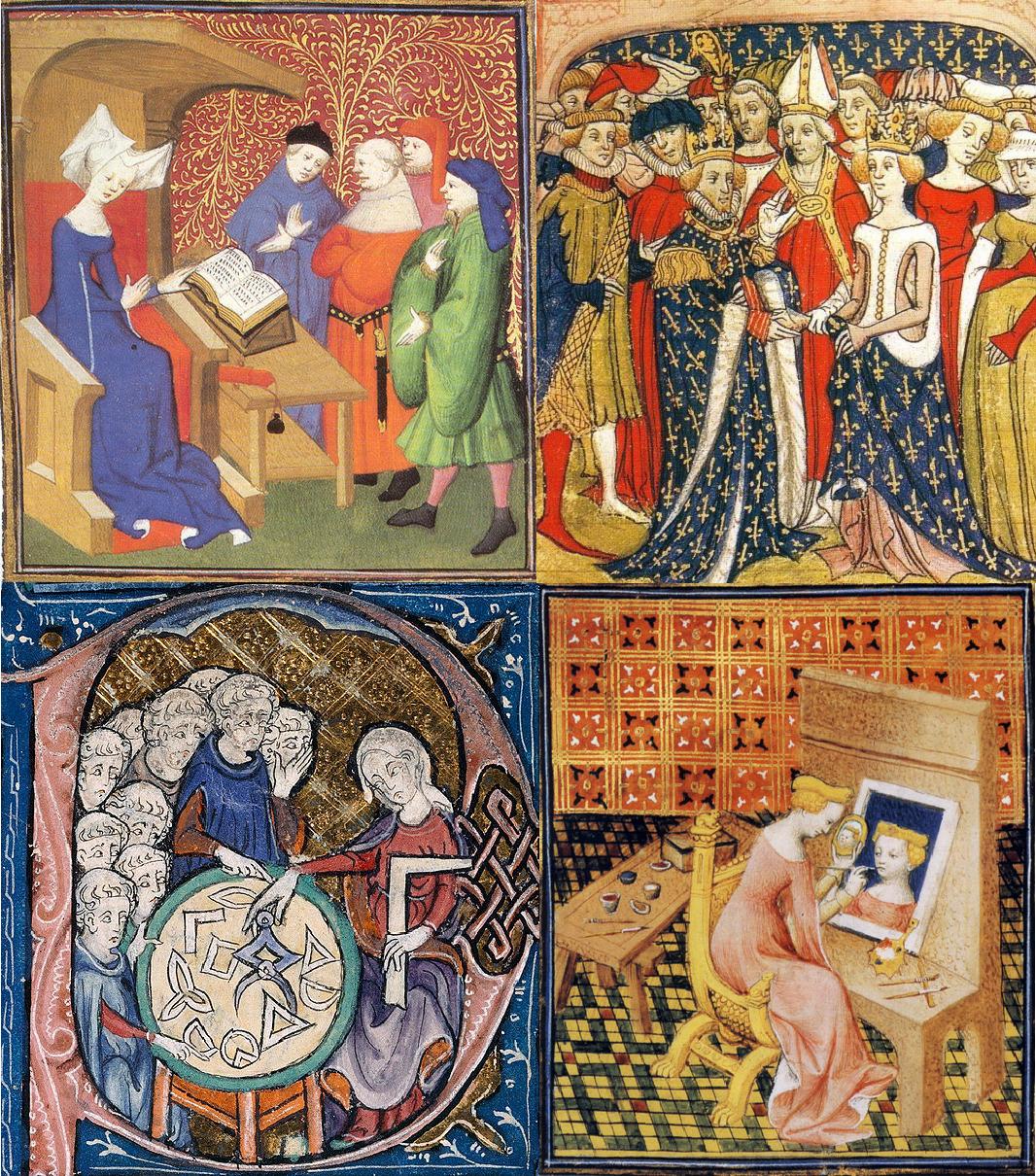

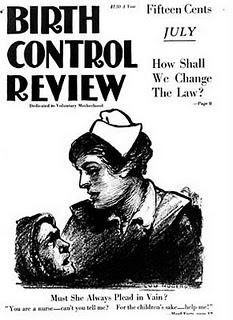

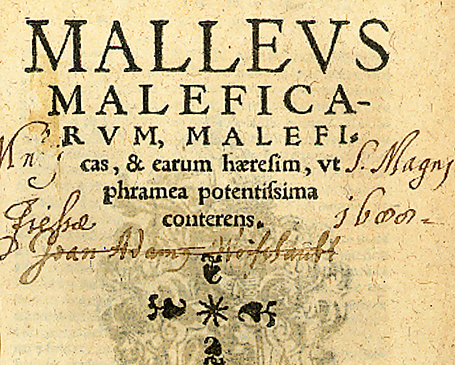

The 16th and 17th centuries saw numerous

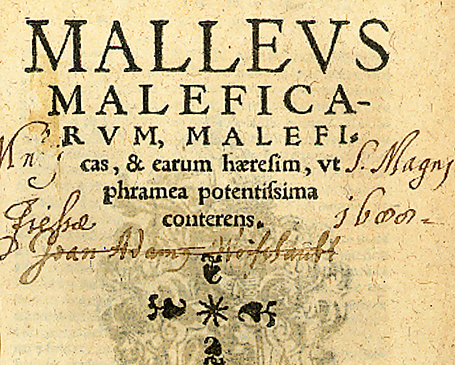

The 16th and 17th centuries saw numerous witch trial

A witch-hunt, or a witch purge, is a search for people who have been labeled witches or a search for evidence of witchcraft. The classical period of witch-hunts in Early Modern Europe and Colonial America took place in the Early Modern perio ...

s, which resulted in thousands of people across Europe being executed, of whom 75–95% were women (depending on time and place).Malleus Maleficarum

The ''Malleus Maleficarum'', usually translated as the ''Hammer of Witches'', is the best known treatise on witchcraft. It was written by the German Catholic clergyman Heinrich Kramer (under his Latinized name ''Henricus Institor'') and first ...

'' and '' Summis Desiderantes'' depicted witches as diabolical conspirators who worshipped Satan and were primarily women. Culture and art at the time depicted these witches as seductive and evil, further fuelling moral panic in fusion with rhetoric from the Church.Heinrich Kramer

Heinrich Kramer ( 1430 – 1505, aged 74-75), also known under the Latinized name Henricus Institor, was a German churchman and inquisitor. With his widely distributed book ''Malleus Maleficarum'' (1487), which describes witchcraft and endors ...

and Jacob Sprengerh justified these beliefs by claiming women had greater credulity, impressionability, feeble minds, feeble bodies, impulsivity and carnal natures which were flaws susceptible to "evil" behavior and witchcraft.English Common Law

English law is the common law legal system of England and Wales, comprising mainly criminal law and civil law, each branch having its own courts and procedures.

Principal elements of English law

Although the common law has, historically, be ...

, which developed from the 12th century onward, all property which a wife held at the time of marriage became a possession of her husband. Eventually, English courts forbade a husband's transferring property without the consent of his wife, but he still retained the right to manage it and to receive the money which it produced. French married women suffered from restrictions on their legal capacity which were removed only in 1965.Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

in Europe allowed more women to add their voices, including the English writers Jane Anger, Aemilia Lanyer, and the prophetess Anna Trapnell. English and American Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abili ...

believed that men and women were equal. Many Quaker women were preachers. Despite relatively greater freedom for Anglo-Saxon women, until the mid-19th century, writers largely assumed that a patriarchal order was a natural order that had always existed.[Maine, Henry Sumner. Ancient Law 1861.] This perception was not seriously challenged until the 18th century when Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

missionaries found matrilineality

Matrilineality is the tracing of kinship through the female line. It may also correlate with a social system in which each person is identified with their matriline – their mother's lineage – and which can involve the inheritance ...

in native North American peoples.

The philosopher John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism". Considered one of ...

opposed marital inequality and the mistreatment of women during this time.Married Women's Property Act 1870

The Married Women's Property Act 1870 (33 & 34 Vict c 93) was an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom that allowed married women to be the legal owners of the money they earned and to inherit property.

Background

Before 1870, any money made ...

and Married Women's Property Act 1882

The Married Women's Property Act 1882 (45 & 46 Vict. c.75) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that significantly altered English law regarding the property rights of married women, which besides other matters allowed married women ...

Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In th ...

wrote in ''An Occasional Letter on the Female Sex 1775'' where he states (as quote) :

= 18th and 19th century Europe

=

Starting in the late 18th century, and throughout the 19th century, rights, as a concept and claim, gained increasing political, social, and philosophical importance in Europe. Movements emerged which demanded

Starting in the late 18th century, and throughout the 19th century, rights, as a concept and claim, gained increasing political, social, and philosophical importance in Europe. Movements emerged which demanded freedom of religion

Freedom of religion or religious liberty is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance. It also includes the freedo ...

, the abolition of slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, rights for women, rights for those who did not own property, and universal suffrage

Universal suffrage (also called universal franchise, general suffrage, and common suffrage of the common man) gives the right to vote to all adult citizens, regardless of wealth, income, gender, social status, race, ethnicity, or political sta ...

. In the late 18th century the question of women's rights became central to political debates in both France and Britain. At the time some of the greatest thinkers of the Enlightenment, who defended democratic principles of equality and challenged notions that a privileged few should rule over the vast majority of the population, believed that these principles should be applied only to their own gender and their own race. The philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

, for example, thought that it was the order of nature for women to obey men. He wrote "Women do wrong to complain of the inequality of man-made laws" and claimed that "when she tries to usurp our rights, she is our inferior".

In 1754, Dorothea Erxleben

Dorothea Christiane Erxleben (13 November 1715 – 13 June 1762) was a German doctor who became the first female doctor of medicinal science in Germany.

Early life

Dorothea was born on 13 November 1715 in the small town of Quedlinburg, German ...

became the first German woman receiving a M.D. (University of Halle

Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg (german: Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg), also referred to as MLU, is a public, research-oriented university in the cities of Halle and Wittenberg and the largest and oldest university in ...

)[Offen, K. (2000): ''European Feminisms, 1700-1950: A Political History'' (Stanford University Press), pg. 43]

In 1791 the French playwright and political

In 1791 the French playwright and political activist

Activism (or Advocacy) consists of efforts to promote, impede, direct or intervene in social, political, economic or environmental reform with the desire to make changes in society toward a perceived greater good. Forms of activism range fro ...

Olympe de Gouges

Olympe de Gouges (; born Marie Gouze; 7 May 17483 November 1793) was a French playwright and political activist whose writings on women's rights and abolitionism reached a large audience in various countries. She began her career as a playwright ...

published the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen

The Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen (french: Déclaration des droits de la femme et de la citoyenne), also known as the Declaration of the Rights of Woman, was written on 14 September 1791 by French activist, femini ...

,[Macdonald and Scherf, "Introduction", pp. 11–12.] modelled on the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (french: Déclaration des droits de l'homme et du citoyen de 1789, links=no), set by France's National Constituent Assembly in 1789, is a human civil rights document from the French Revol ...

of 1789. The Declaration is ironic in formulation and exposes the failure of the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

, which had been devoted to equality. It states that: "This revolution will only take effect when all women become fully aware of their deplorable condition, and of the rights they have lost in society". The Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen follows the seventeen articles of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (french: Déclaration des droits de l'homme et du citoyen de 1789, links=no), set by France's National Constituent Assembly in 1789, is a human civil rights document from the French Revol ...

point for point and has been described by Camille Naish as "almost a parody... of the original document". The first article of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen proclaims that "Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be based only on common utility." The first article of the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen replied: "Woman is born free and remains equal to man in rights. Social distinctions may only be based on common utility". De Gouges expands the sixth article of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, which declared the rights of citizens to take part in the formation of law, to:

All citizens including women are equally admissible to all public dignities, offices and employments, according to their capacity, and with no other distinction than that of their virtues and talents.

De Gouges also draws attention to the fact that under French law women were fully punishable, yet denied equal rights.

She was subsequently sent to the guillotine.

Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft (, ; 27 April 1759 – 10 September 1797) was a British writer, philosopher, and advocate of women's rights. Until the late 20th century, Wollstonecraft's life, which encompassed several unconventional personal relationsh ...

, a British writer and philosopher, published ''A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

''A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects'' (1792), written by British philosopher and women's rights advocate Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797), is one of the earliest works of feminist philosop ...

'' in 1792, arguing that it was the education and upbringing of women that created limited expectations.[Walters, Margaret, ''Feminism: A very short introduction'' (Oxford, 2005), .] Wollstonecraft attacked gender oppression, pressing for equal educational opportunities, and demanded "justice!" and "rights to humanity" for all. Wollstonecraft, along with her British contemporaries Damaris Cudworth and Catharine Macaulay

Catharine Macaulay (née Sawbridge, later Graham; 23 March 1731 – 22 June 1791), was an English Whig republican historian.

Early life

Catharine Macaulay was a daughter of John Sawbridge (1699–1762) and his wife Elizabeth Wanley (died 1733 ...

, started to use the language of rights in relation to women, arguing that women should have greater opportunity because like men, they were moral and rational beings.

Mary Robinson

Mary Therese Winifred Robinson ( ga, Máire Mhic Róibín; ; born 21 May 1944) is an Irish politician who was the 7th president of Ireland, serving from December 1990 to September 1997, the first woman to hold this office. Prior to her electi ...

wrote in a similar vein in "A Letter to the Women of England, on the Injustice of Mental Subordination.", 1799.

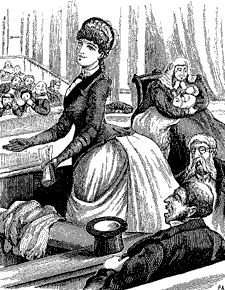

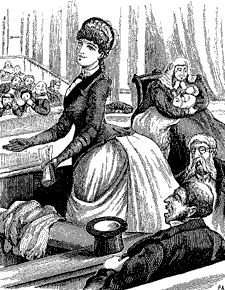

In his 1869 essay "The Subjection of Women

''The Subjection of Women'' is an essay by English philosopher, political economist and civil servant John Stuart Mill published in 1869, with ideas he developed jointly with his wife Harriet Taylor Mill. Mill submitted the finished manuscript ...

" the English philosopher and political theorist John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, Member of Parliament (MP) and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of classical liberalism, he contributed widely to ...

described the situation for women in Britain as follows:

We are continually told that civilization and Christianity have restored to the woman her just rights. Meanwhile, the wife is the actual bondservant of her husband; no less so, as far as the legal obligation goes, than slaves commonly so called.

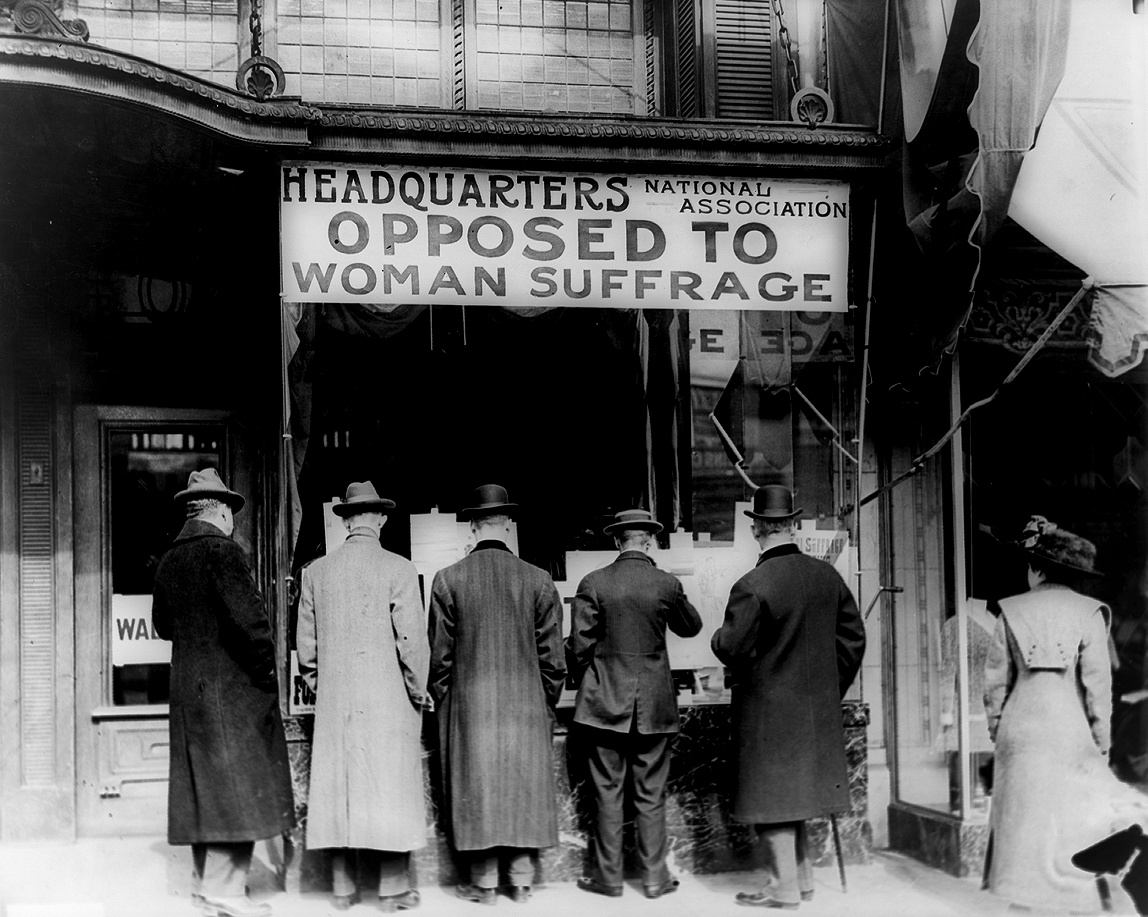

Then a member of parliament, Mill argued that women deserve the right to vote

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

, though his proposal to replace the term "man" with "person" in the second Reform Bill of 1867 was greeted with laughter in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

and defeated by 76 to 196 votes. His arguments won little support amongst contemporaries[ Initially only one of several women's rights campaigns, suffrage became the primary cause of the British women's movement at the beginning of the 20th century. At the time, the ability to vote was restricted to wealthy property owners within British jurisdictions. This arrangement implicitly excluded women as ]property law

Property law is the area of law that governs the various forms of ownership in real property (land) and personal property. Property refers to legally protected claims to resources, such as land and personal property, including intellectual pro ...

and marriage law

Marriage law refers to the legal requirements that determine the validity of a marriage, and which vary considerably among countries. See also Marriage Act.

Summary table

Rights and obligations

A marriage, by definition, bestows ...

gave men ownership rights at marriage or inheritance until the 19th century. Although male suffrage broadened during the century, women were explicitly prohibited from voting nationally and locally in the 1830s by the Reform Act 1832

The Representation of the People Act 1832 (also known as the 1832 Reform Act, Great Reform Act or First Reform Act) was an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom (indexed as 2 & 3 Will. IV c. 45) that introduced major changes to the electo ...

and the Municipal Corporations Act 1835

The Municipal Corporations Act 1835 (5 & 6 Will 4 c 76), sometimes known as the Municipal Reform Act, was an Act of Parliament, Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that reformed local government in the incorporated boroughs of England and ...

.[Phillips, Melanie, ''The Ascent of Woman: A History of the Suffragette Movement'' (Abacus, 2004)] Millicent Fawcett and Emmeline Pankhurst

Emmeline Pankhurst (''née'' Goulden; 15 July 1858 – 14 June 1928) was an English political activist who organised the UK suffragette movement and helped women win the right to vote. In 1999, ''Time'' named her as one of the 100 Most Import ...

led the public campaign on women's suffrage and in 1918 a bill was passed allowing women over the age of 30 to vote.consumer

A consumer is a person or a group who intends to order, or uses purchased goods, products, or services primarily for personal, social, family, household and similar needs, who is not directly related to entrepreneurial or business activities. ...

culture, including the emergence of the department store

A department store is a retail establishment offering a wide range of consumer goods in different areas of the store, each area ("department") specializing in a product category. In modern major cities, the department store made a dramatic appe ...

, and Separate spheres

Terms such as separate spheres and domestic–public dichotomy refer to a social phenomenon within modern societies that feature, to some degree, an empirical separation between a domestic or private sphere and a public or social sphere. This o ...

.

In ''Come Buy, Come Buy: Shopping and the Culture of Consumption in Victorian Women's Writing'', Krista Lysack's literary analysis of 19th-century contemporary literature claims through her resources' reflection of common contemporary norms, "Victorian femininity as characterized by self-renunciation and the regulation of appetite."[Lysack, Krista. Come buy, come buy: shopping and the culture of consumption in Victorian women's writing. n.p.: Athens : Ohio University Press, c2008., 2008.]

While women, particularly those in the middle class, obtained modest control of daily household expenses and had the ability to leave the house, attend social events, and shop for personal and household items in the various department stores developing in late 19th century Europe, Europe's socioeconomic climate pervaded the ideology that women were not in complete control over their urges to spend (assuming) their husband or father's wages. As a result, many advertisements for socially 'feminine' goods revolved around upward social progression, exoticism

Exoticism (from "exotic") is a trend in European art and design, whereby artists became fascinated with ideas and styles from distant regions and drew inspiration from them. This often involved surrounding foreign cultures with mystique and fanta ...

s from the Orient

The Orient is a term for the East in relation to Europe, traditionally comprising anything belonging to the Eastern world. It is the antonym of '' Occident'', the Western World. In English, it is largely a metonym for, and coterminous with, the ...

, and added efficiency for household roles women were deemed responsible for, such as cleaning, childcare, and cooking.

= Russia

=

By law and custom, Muscovite Russia was a patriarchal society that subordinated women to men, and the young to their elders. Peter the Great

Peter I ( – ), most commonly known as Peter the Great,) or Pyotr Alekséyevich ( rus, Пётр Алексе́евич, p=ˈpʲɵtr ɐlʲɪˈksʲejɪvʲɪtɕ, , group=pron was a Russian monarch who ruled the Tsardom of Russia from t ...

relaxed the second custom, but not the subordination of women.World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, caring for children was increasingly difficult for women, many of whom could not support themselves, and whose husbands had died or were fighting in the war. Many women had to give up their children to children's homes infamous for abuse and neglect. These children's homes were unofficially dubbed as "angel factories". After the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mom ...

, the Bolsheviks shut down an infamous angel factory known as the 'Nikolaev Institute' situated near the Moika Canal. The Bolsheviks then replaced the Nikolaev Institute with a modern maternity home called the 'Palace for Mothers and Babies'. This maternity home was used by the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

as a model for future maternity hospitals. The countess who ran the old Institute was moved to a side wing, however she spread rumours that the Bolsheviks had removed sacred pictures, and that the nurses were promiscuous with sailors. The maternity hospital was burnt down hours before it was scheduled to open, and the countess was suspected of being responsible.

Russian women had restrictions in owning property until the mid 18th century.Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

under the Bolsheviks.

North America

= Canada

=

Women's rights activism in Canada during the 19th and early 20th centuries focused on increasing women's role in public life, with goals including women's suffrage, increased property rights, increased access to education, and recognition of women as "persons" under the law.

Women's rights activism in Canada during the 19th and early 20th centuries focused on increasing women's role in public life, with goals including women's suffrage, increased property rights, increased access to education, and recognition of women as "persons" under the law.Emily Murphy

Emily Murphy (born Emily Gowan Ferguson; 14 March 186827 October 1933) was a Canadian women's rights activist and author. In 1916, she became the first female magistrate in Canada and in the British Empire. She is best known for her contributio ...

, Irene Marryat Parlby, Nellie Mooney McClung, Louise Crummy McKinney and Henrietta Muir Edwards – who, in 1927, asked the Supreme Court of Canada

The Supreme Court of Canada (SCC; french: Cour suprême du Canada, CSC) is the Supreme court, highest court in the Court system of Canada, judicial system of Canada. It comprises List of Justices of the Supreme Court of Canada, nine justices, wh ...

to answer the question, "Does the word 'Persons' in Section 24 of the British North America Act, 1867

The ''Constitution Act, 1867'' (french: Loi constitutionnelle de 1867),''The Constitution Act, 1867'', 30 & 31 Victoria (U.K.), c. 3, http://canlii.ca/t/ldsw retrieved on 2019-03-14. originally enacted as the ''British North America Act, 186 ...

, include female persons?" in the case '' Edwards v. Canada (Attorney General).''court of last resort

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

for Canada within the British Empire and Commonwealth.

= United States

=

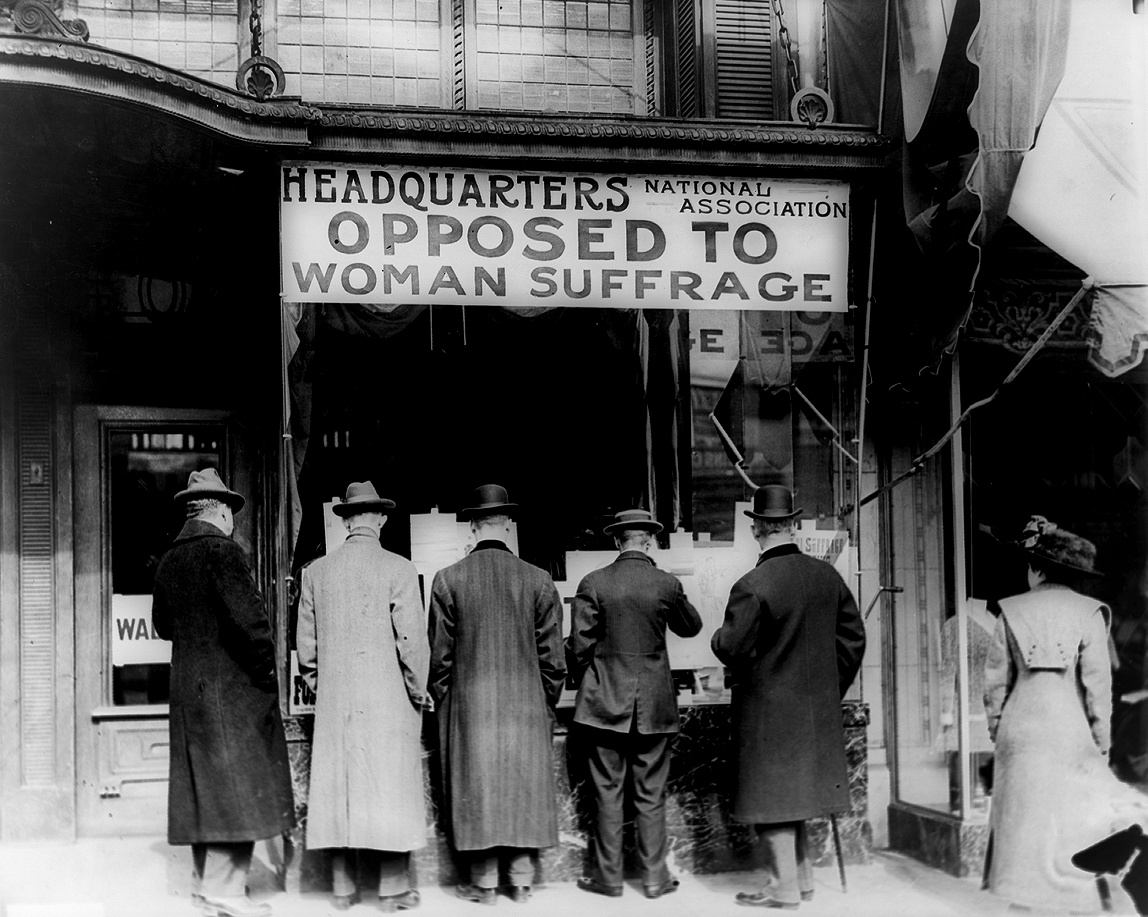

The Women's Christian Temperance Union

The Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) is an international temperance organization, originating among women in the United States Prohibition movement. It was among the first organizations of women devoted to social reform with a program th ...

(WCTU) was established in 1873 and championed women's rights, including advocating for prostitutes and for women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

.

Asia

= East Asia

=

Japan

The extent to which women could participate in Japanese society

The culture of Japan has changed greatly over the millennia, from the country's prehistoric Jōmon period, to its contemporary modern culture, which absorbs influences from Asia and other regions of the world.

Historical overview

The ances ...

has varied over time and social classes. In the 8th century, Japan had women emperors, and in the 12th century (Heian period

The is the last division of classical Japanese history, running from 794 to 1185. It followed the Nara period, beginning when the 50th emperor, Emperor Kanmu, moved the capital of Japan to Heian-kyō (modern Kyoto). means "peace" in Japan ...

) women in Japan occupied a relatively high status, although still subordinated to men.

From the late Edo period

The or is the period between 1603 and 1867 in the history of Japan, when Japan was under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate and the country's 300 regional '' daimyo''. Emerging from the chaos of the Sengoku period, the Edo period was character ...

, the status of women declined. In the 17th century, the "Onna Daigaku

The ''Onna Daigaku'' ( or "The Great Learning for Women") is an 18th-century Japanese educational text advocating for neo-Confucian values in education, with the oldest existing version dating to 1729. It is frequently attributed to Japanese botan ...

", or "Learning for Women", by Confucianist

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China. Variously described as tradition, a philosophy, a religion, a humanistic or rationalistic religion, a way of governing, or ...

author Kaibara Ekken

__NOTOC__

or Ekiken, also known as Atsunobu (篤信), was a Japanese Neo-Confucianist philosopher and botanist.

Kaibara was born into a family of advisors to the ''daimyō'' of Fukuoka Domain in Chikuzen Province (modern-day Fukuoka Prefecture ...

, spelled out expectations for Japanese women, lowering significantly their status.Meiji period

The is an era of Japanese history that extended from October 23, 1868 to July 30, 1912.

The Meiji era was the first half of the Empire of Japan, when the Japanese people moved from being an isolated feudal society at risk of colonization ...

, industrialization and urbanization reduced the authority of fathers and husbands, but at the same time the Meiji Civil Code of 1898 denied women legal rights and subjugated them to the will of household heads.Constitution of Japan