Richard T. Greener on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

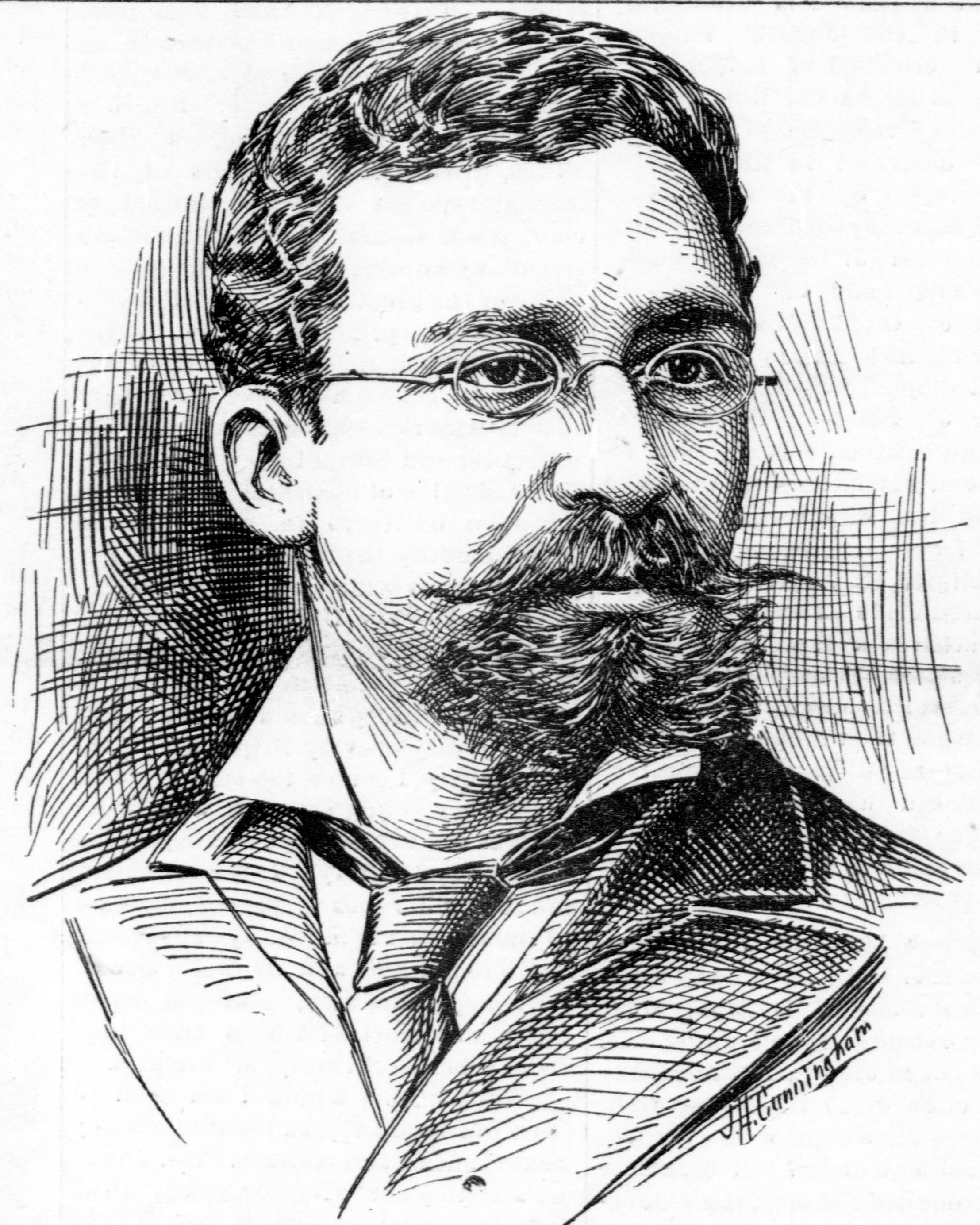

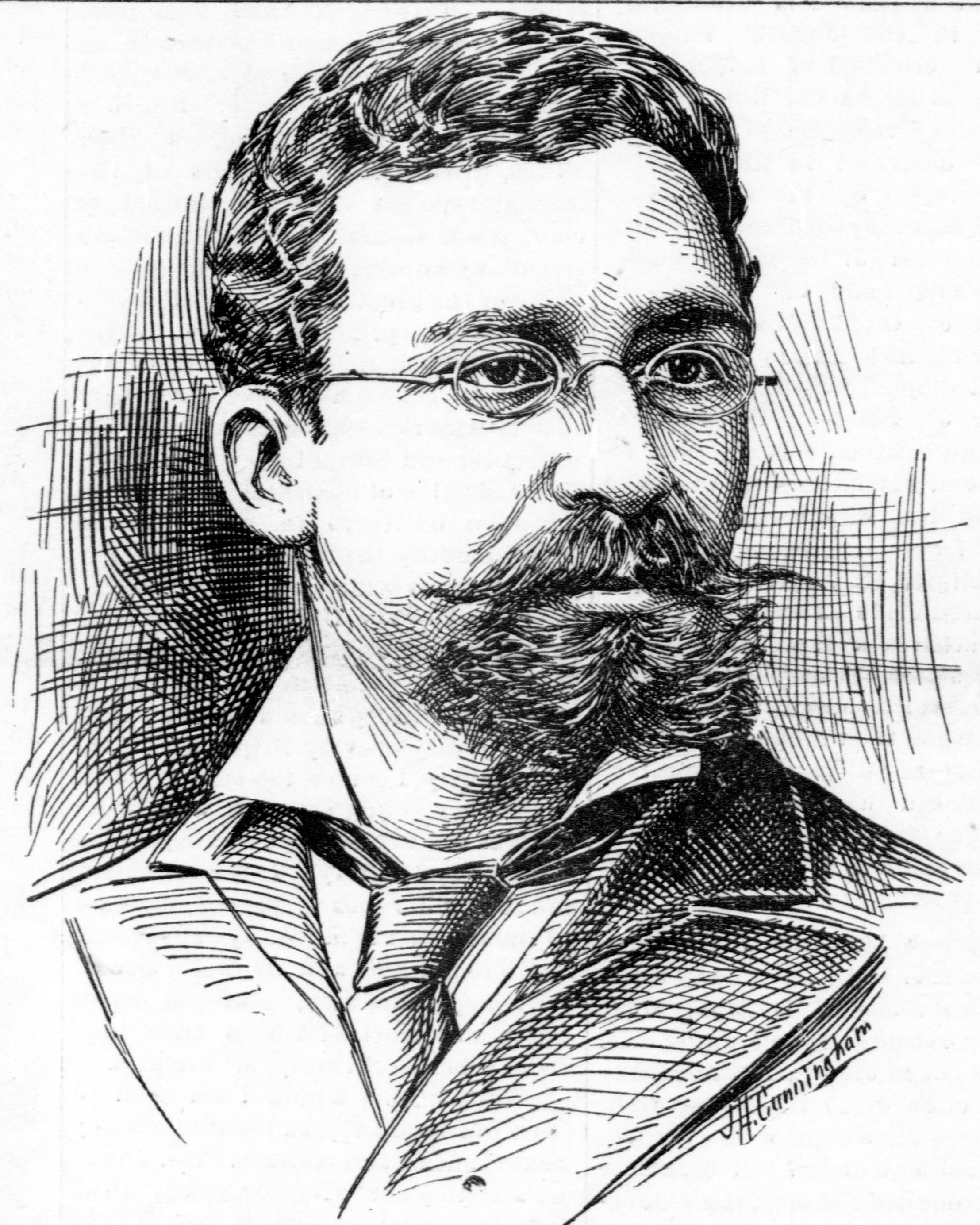

Richard Theodore Greener (1844–1922) was a pioneering

In 1898, Greener was appointed by President

In 1898, Greener was appointed by President

Greener settled in

Greener settled in

Along with having accomplished many African-American firsts, Greener earned several awards in his lifetime.

In 1902, the Chinese government decorated him with the

Along with having accomplished many African-American firsts, Greener earned several awards in his lifetime.

In 1902, the Chinese government decorated him with the

Richard T. Greener Website

Phillips Academy quad to be named for Greener

{{DEFAULTSORT:Greener, Richard Theodore South Carolina lawyers Lawyers from Washington, D.C. African-American lawyers African-American legal scholars American legal scholars American librarians African-American librarians American diplomats Howard University faculty Harvard College alumni Oberlin College alumni Phillips Academy alumni South Carolina Republicans New York (state) Republicans Illinois Republicans 19th-century African-American people 20th-century African-American people 1844 births 1922 deaths Burials at Graceland Cemetery (Chicago)

African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ensl ...

scholar, excelling in elocution, philosophy, law and classics in the Reconstruction era. He broke ground as Harvard College's first Black graduate in 1870. Within three years, he had also graduated from law school at the University of South Carolina, only to also be hired as its first Black professor, after briefly serving as associate editor for the ''New National Era

''New National Era'' (1870–1874) was an African American newspaper, published in Washington D.C. during the Reconstruction Era in the decade after the American Civil War and the Emancipation Proclamation. Originally known as the ''New Era'', t ...

'', a newspaper owned and edited by Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

.

In 1875, Greener became the first African American elected to the American Philological Association, the primary academic society for classical studies in North America. In 1876, he was admitted to practice in the Supreme Court of South Carolina, and the following year he was also admitted to the Bar of the District of Columbia. He went on to serve as dean

Dean may refer to:

People

* Dean (given name)

* Dean (surname), a surname of Anglo-Saxon English origin

* Dean (South Korean singer), a stage name for singer Kwon Hyuk

* Dean Delannoit, a Belgian singer most known by the mononym Dean

Titles

* ...

of the Howard University School of Law.

In 1898, he became America's first Black diplomat to a white country, serving in Vladivostok

Vladivostok ( rus, Владивосто́к, a=Владивосток.ogg, p=vɫədʲɪvɐˈstok) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai, Russia. The city is located around the Golden Horn Bay on the Sea of Japan, c ...

, Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

. He went on to serve as an American representative during the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

, but left the diplomatic service in 1905.

In 1902, the Chinese government honored him for his service to the Boxer War

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, the Boxer Insurrection, or the Yihetuan Movement, was an anti-foreign, anti-colonial, and anti-Christian uprising in China between 1899 and 1901, towards the end of the Qing dynasty, by ...

, and his assistance to Shansi

Shanxi (; ; formerly romanised as Shansi) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China and is part of the North China region. The capital and largest city of the province is Taiyuan, while its next most populated prefecture-lev ...

famine sufferers. Liberia's Monrovia College awarded him an honorary Doctorate of Law in 1882, as did Howard University in 1907. Phillips Academy and the University of South Carolina both grant annual scholarships in Greener's name. Phillips Academy also named a central quadrangle after Greener in 2018, the same year the University of South Carolina honored him with a statue.

Early life and education

Richard Greener was born inPhiladelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, largest city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the List of United States cities by population, sixth-largest city i ...

, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, in 1844. He moved with his family to Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

in 1853, where he was unable to attend public school due to the colour of his skin. He was enrolled at a private school but dropped out within a few years to support his family after his father left for the California Gold Rush, and never returned to earn money to support his family. One of his employers, Franklin B. Sanborn, helped him to enroll in preparatory school (Oberlin Academy

Oberlin Academy Preparatory School, originally Oberlin Institute and then Preparatory Department of Oberlin College, was a private preparatory school in Oberlin, Ohio which operated from 1833 until 1916. It opened as Oberlin Institute which beca ...

) at Oberlin College.

He then enrolled at Phillips Academy and graduated in 1865. He studied at Oberlin College for three years before transferring to Harvard College

Harvard College is the undergraduate college of Harvard University, an Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636, Harvard College is the original school of Harvard University, the oldest institution of higher lea ...

where he earned a bachelor's degree in 1870. His admission to Harvard was "an experiment" by the administration and paved the way for many more Black Harvard graduates.

While at Harvard, he earned the Bowdoin Prize The Bowdoin Prizes are prestigious awards given annually to Harvard University undergraduate and graduate students. From the income of the bequest of Governor James Bowdoin, AB 1745, prizes are offered to students at the University in graduate and ...

for elocution twice, which the '' Rochester Daily Democrat'' mentioned in an article on August 16, 1869:

Richard Theodore Greener, a young colored man and a member of the senior class of Harvard College, is giving public readings in Philadelphia. Mr. Greener's history is that of a persevering young man who has succeeded in living down the prejudices against his race and color, and attaining by industry, ability, and good character, a position of which he may well feel proud. He was awarded last year, at Harvard College, the prize for reading, and this year he has drilled two young white men who have likewise obtained prizes in the same branch. His course at Harvard has throughout been honorable. He is the first colored youth who has ever passed through that college.

Academic career

After graduating from Harvard, Greener served as a principal at theInstitute for Colored Youth

The Institute for Colored Youth was founded in 1837 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. It became the first high school for African-Americans in the United States, although there were schools that admitted African Americans preceding it ...

in Philadelphia from September 1870 until December 1872. He succeeded Octavius V. Catto, who was shot in a riot. From January 1 to July 1, 1873, he was principal of the Sumner High School, a colored preparatory school in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

Simmons, William J., and Henry McNeal Turner, ''Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising'', GM Rewell & Company, 1887, pp. 327–335.

After leaving the Sumner School, Greener briefly took a job as associate editor of '' The New National Era'' in April 1873, working under editor Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

. He was also an associate editor for the ''National Encyclopedia for American Biography''.

University of South Carolina

In October 1873, Greener accepted the professorship of mental and moral philosophy at the University of South Carolina, where he was the university's first African-American faculty member. He also served as a librarian there helping to "reorganize and catalog the library's holdings which were in disarray after the Civil War" and wrote a monograph on the rare books of the library. His responsibilities included assisting in the departments of Latin and Greek and teaching classes in International Law and the Constitution of the United States. In 1875, Greener became the first African American to be elected a member of the American Philological Association, the primary academic society for classical studies in North America.Howard Law School

Greener graduated from the law school at the University of South Carolina and was admitted to practice in the Supreme Court of South Carolina on December 20, 1876. In June 1877, following the end of Reconstruction in South Carolina, the university was closed byWade Hampton III

Wade Hampton III (March 28, 1818April 11, 1902) was an American military officer who served the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War and later a politician from South Carolina. He came from a wealthy planter family, and ...

. Greener moved to Washington and was admitted to the Bar of the District of Columbia on April 14, 1877. He took a position as a professor at Howard University Law School

Howard University School of Law (Howard Law or HUSL) is the law school of Howard University, a private, federally chartered historically black research university in Washington, D.C. It is one of the oldest law schools in the country and the old ...

and served as dean from 1878 to 1880, succeeding John H. Cooke.

He also worked on a number of famous legal cases. He was associate counsel of Jeremiah M. Wilson in the defense of Samuel L. Perry and of Martin I. Townsend in the defense of Johnson Chesnut Whittaker in a court of inquiry in April and May 1880 where Towsend and Greener successfully gained Whittaker release and the granting of a court-martial. Greener assisted Daniel Henry Chamberlain

Daniel Henry Chamberlain (June 23, 1835April 13, 1907) was an American planter, lawyer, author and the 76th Governor of South Carolina from 1874 until 1876 or 1877. The federal government withdrew troops from the state and ended Reconstruction ...

in Whittaker's defense during the court-martial.

Public service and activism

From 1876 to 1879, Greener represented South Carolina in theUnion League

The Union Leagues were quasi-secretive men’s clubs established separately, starting in 1862, and continuing throughout the Civil War (1861–1865). The oldest Union League of America council member, an organization originally called "The Leag ...

of America and was president of the South Carolina Republican Association in 1887 and was active in freemasonry

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

. In 1875, Greener was appointed by the South Carolina Assembly to a commission to revise the South Carolina school system.

From 1880 until February 28, 1882, Greener served as a law clerk of the Comptroller of the United States Treasury.

In 1883, Greener and Frederick Douglass conducted a heated debate. Greener and the rising generation of Black leaders advocated moving away from political parties and white allies, while Douglass denounced them as "croakers." Greener, who nonetheless still respected Douglass's achievements, helped organize a major convention to present Black grievances to the nation. Decades had passed since the Civil War, the Emancipation Proclamation, and years since the passage of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, but these advances had been rolled back or left unenforced, while Jim Crow laws spread in the South. Greener joined younger Black leaders in questioning Douglass, who remained loyal to the Republican Party that had first fought for Black freedom then abandoned them. Douglass accused Greener of writing anonymous attacks motivated by “ambition and jealousy” that charged the older leader with “trading off the colored vote of the country for office.” Greener wrote that there were two Douglasses, “the one velvety, deprecatory, apologetic – the other insinuating, suggestive damning with shrug, a raised eyebrow, or a look of caution.”

From 1885 to 1892, Greener served as secretary of the Grant Monument Association, where he is credited with having led the initial fundraising effort that eventually brought in donations from 90,000 people worldwide to construct Grant's Tomb. From 1885 to 1890, he was chief examiner of the civil service board for New York City and County. In the 1896 election, he served as the head of the Colored Bureau of the Republican Party in Chicago.

Just as Greener opposed Douglass, he was on the Washington side of the growing split in the African American world. On the one side was accommodationist, and therefore politically powerful and adequately funded, Booker T. Washington

Booker Taliaferro Washington (April 5, 1856November 14, 1915) was an American educator, author, orator, and adviser to several presidents of the United States. Between 1890 and 1915, Washington was the dominant leader in the African-American c ...

. On the other were Monroe Trotter, W.E.B. DuBois, and their followers, who insisted that under the Constitution they had rights and that those rights should be respected. From it were born the Niagara Conferences, and from them the NAACP. Greener was so closely allied with Washington that Washington sent him to the Second Niagara Conference with the explicit charge of spying and reporting.

Diplomat

In 1898, Greener was appointed by President

In 1898, Greener was appointed by President William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in ...

as General Consul at Bombay

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay — the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' financial centre of India. According to the United Nations, as of 2018, Mumbai is the second-m ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

. Soon he accepted a post as United States Commercial Agent in Vladivostok

Vladivostok ( rus, Владивосто́к, a=Владивосток.ogg, p=vɫədʲɪvɐˈstok) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai, Russia. The city is located around the Golden Horn Bay on the Sea of Japan, c ...

, Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

. He successfully served as an American representative during the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

but left the diplomatic service in 1905.

Personal life

On September 24, 1874, Greener married Genevieve Ida Fleet, and they had six children. Greener separated from his wife upon his posting to Vladivostok and took a Japanese common-law wife, Mishi Kawashima, with whom he had three children. Though they never divorced, Fleet and her daughters changed their name to "Greene" to disassociate themselves from him. One of his daughters,Belle da Costa Greene

Belle da Costa Greene (November 26, 1879 – May 10, 1950) was an American librarian best known for managing and developing the personal library of J. P. Morgan. After Morgan's death in 1913, Greene continued as librarian for his son, Jack ...

, became the personal librarian to J. P. Morgan

John Pierpont Morgan Sr. (April 17, 1837 – March 31, 1913) was an American financier and investment banker who dominated corporate finance on Wall Street throughout the Gilded Age. As the head of the banking firm that ultimately became known ...

and passed for white.

Later life and death

Greener settled in

Greener settled in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

with relatives. He held a job as an agent for an insurance company, practiced law, and occasionally lectured on his life and times. He died of natural causes in Chicago on May 2, 1922, aged 78. He was buried at Graceland Cemetery

Graceland Cemetery is a large historic garden cemetery located in the north side community area of Uptown, in the city of Chicago, Illinois, United States. Established in 1860, its main entrance is at the intersection of Clark Street and Ir ...

.

His Harvard diploma and other personal papers were rediscovered in an attic in the South Side of Chicago in the early 21st century. A great deal of discussion surrounds where the papers should be archived.

Legacy

Along with having accomplished many African-American firsts, Greener earned several awards in his lifetime.

In 1902, the Chinese government decorated him with the

Along with having accomplished many African-American firsts, Greener earned several awards in his lifetime.

In 1902, the Chinese government decorated him with the Order of the Double Dragon

The Imperial Order of the Double Dragon () was an order awarded in the late Qing dynasty.

The Order was founded by the Guangxu Emperor on 7 February 1882 as an award for outstanding services to the throne and the Qing court. Originally it was aw ...

for his service to the Boxer War

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, the Boxer Insurrection, or the Yihetuan Movement, was an anti-foreign, anti-colonial, and anti-Christian uprising in China between 1899 and 1901, towards the end of the Qing dynasty, by ...

and assistance to Shansi

Shanxi (; ; formerly romanised as Shansi) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China and is part of the North China region. The capital and largest city of the province is Taiyuan, while its next most populated prefecture-lev ...

famine sufferers.

He received two honorary Doctorates of Laws, from Monrovia College in Liberia in 1882 and Howard University in 1907. Phillips Academy and University of South Carolina both grant annual scholarships in Greener's name.

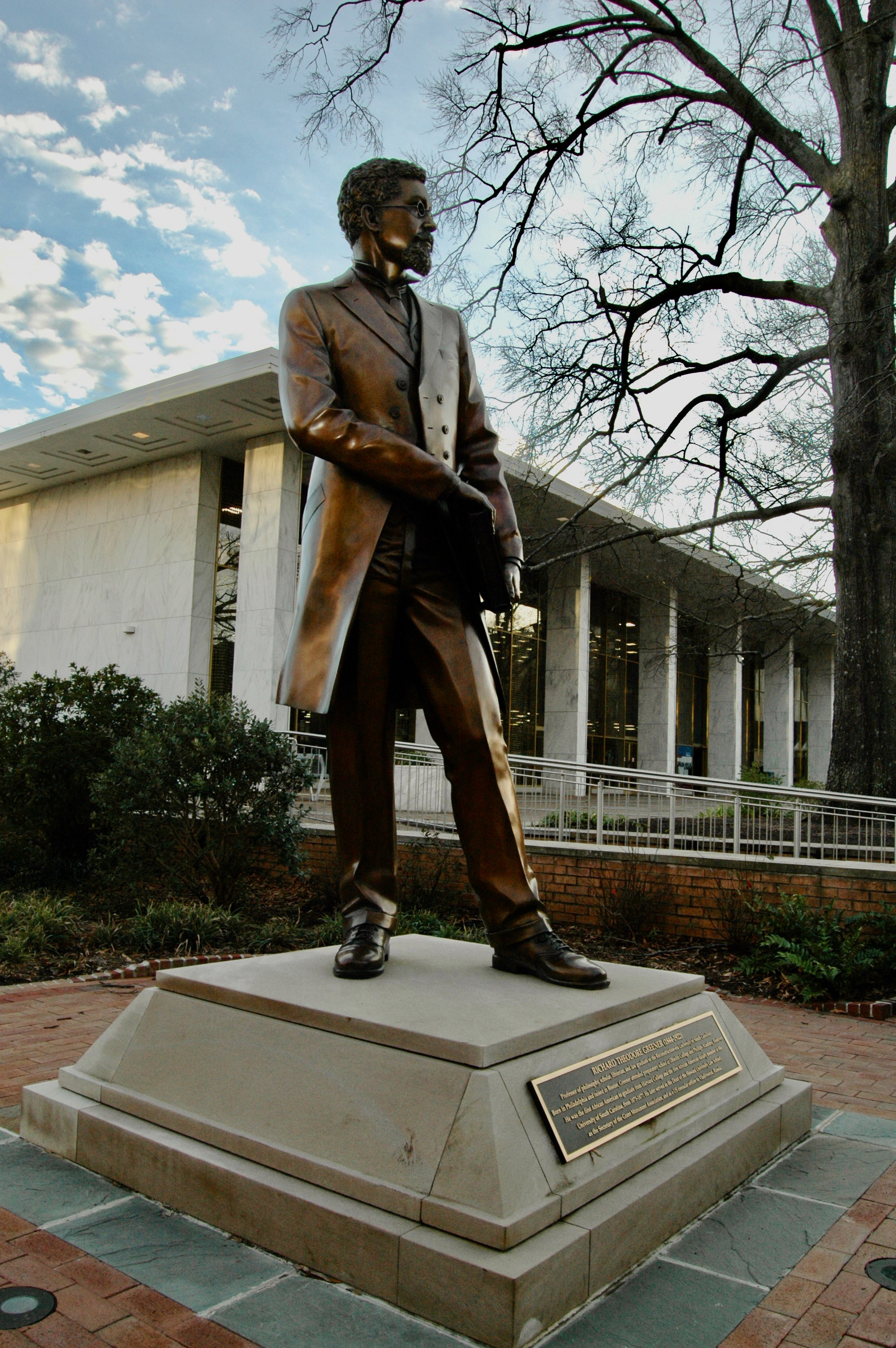

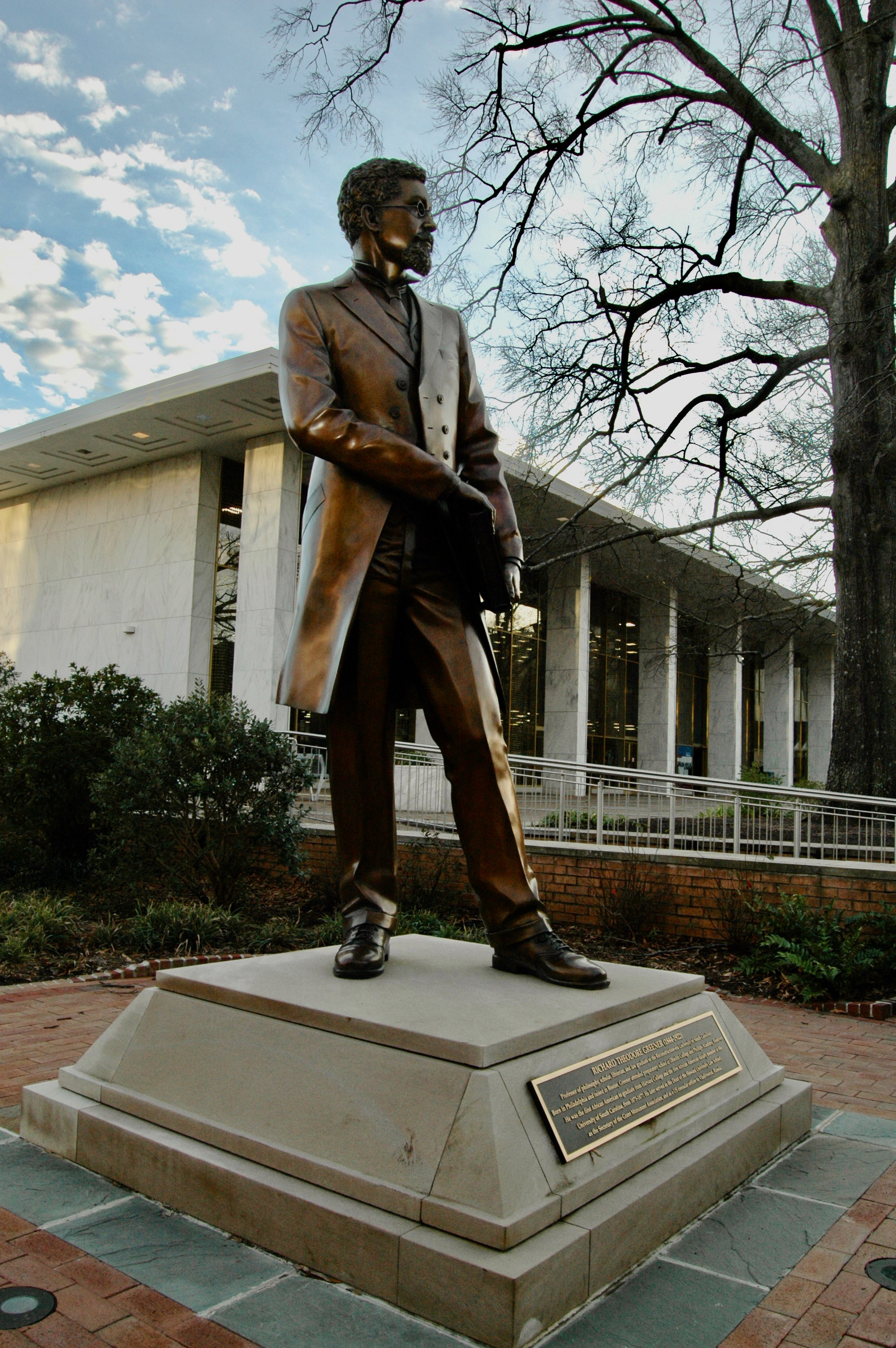

The central quadrangle at Phillips Academy was named in honor of Greener in 2018. The University of South Carolina erected a statue of Greener.

In 2009, some of his personal papers were discovered in the attic of an abandoned home on the south side of Chicago by a member of a demolition crew.

On February 21, 2018, a nine-foot statue of Greener was unveiled at the University of South Carolina. It stands in front of the Thomas Cooper Library.

References

Further reading

*Anderson, Christian K. and Jason C. Darby (2021). “Richard T. Greener at the Reconstruction-era University: Professor, Librarian, and Student.” In Robert Greene II and Tyler D. Parry (Eds.), ''Invisible No More: The African American Experience at the University of South Carolina'' (pp. 51–72). Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press. * * * * * * * for electronic book.External links

Richard T. Greener Website

Phillips Academy quad to be named for Greener

{{DEFAULTSORT:Greener, Richard Theodore South Carolina lawyers Lawyers from Washington, D.C. African-American lawyers African-American legal scholars American legal scholars American librarians African-American librarians American diplomats Howard University faculty Harvard College alumni Oberlin College alumni Phillips Academy alumni South Carolina Republicans New York (state) Republicans Illinois Republicans 19th-century African-American people 20th-century African-American people 1844 births 1922 deaths Burials at Graceland Cemetery (Chicago)