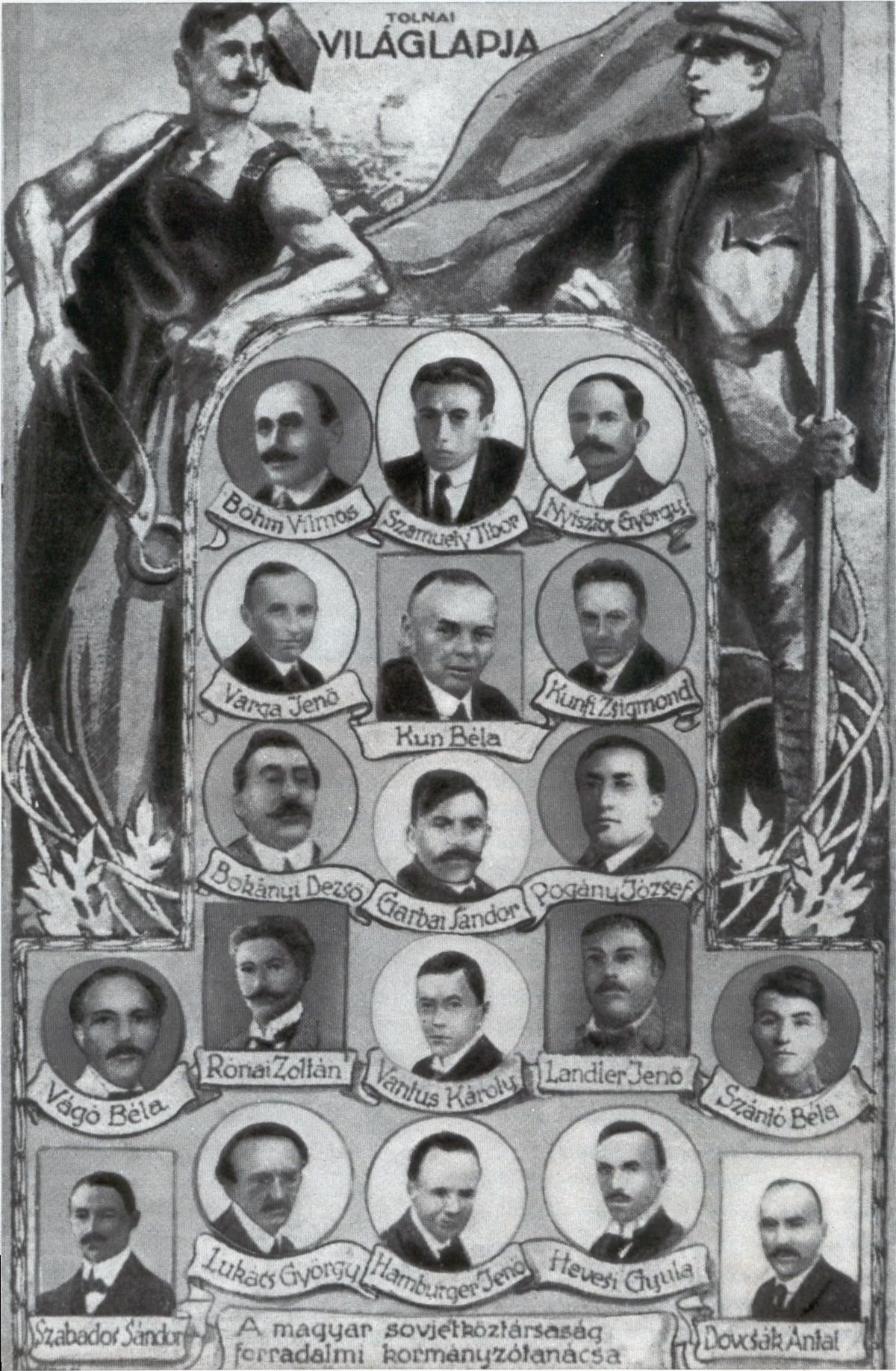

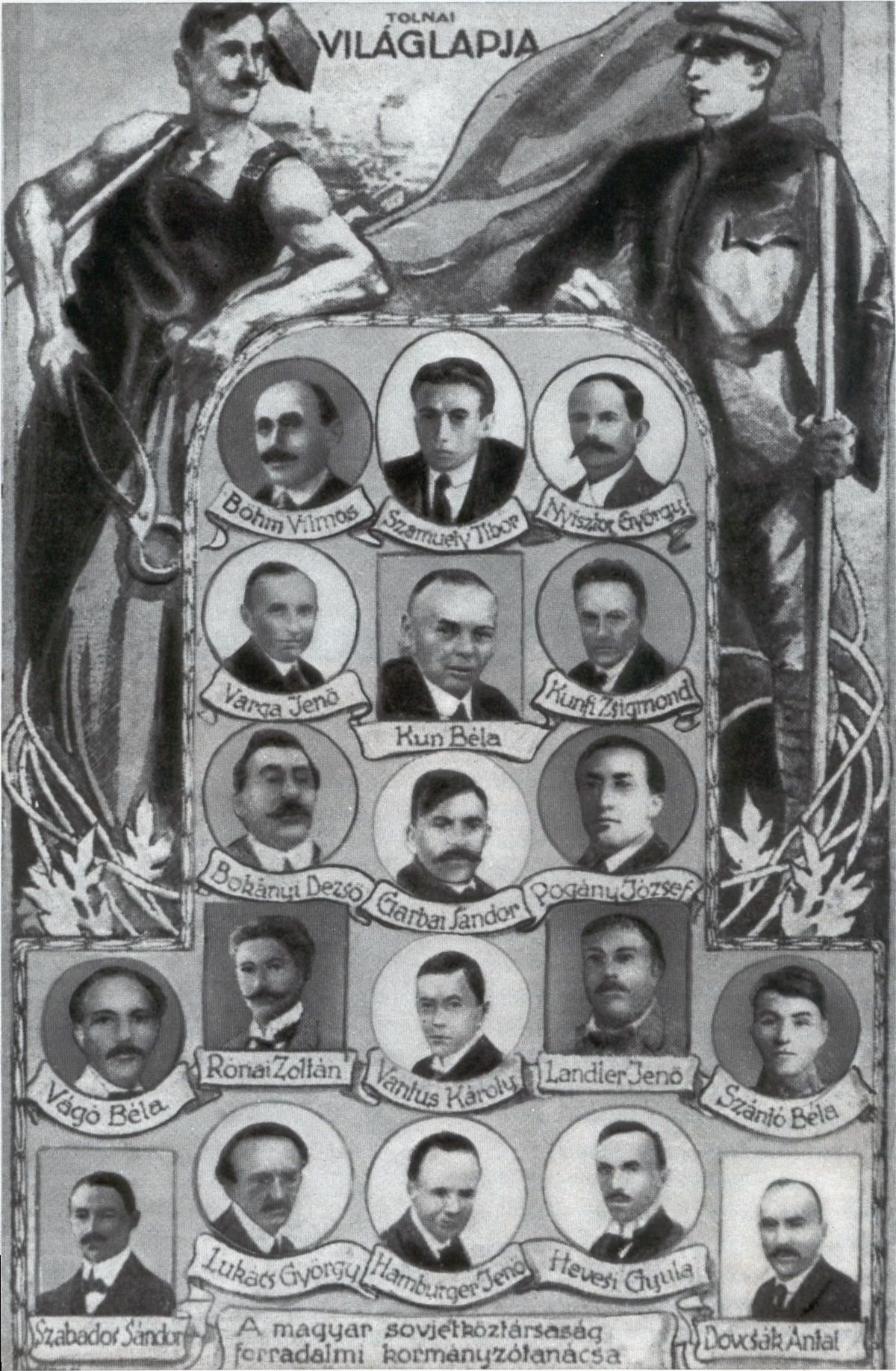

Revolutionary Governing Council on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Socialist Federative Republic of Councils in Hungary ( hu, Magyarországi Szocialista Szövetséges Tanácsköztársaság) (due to an early mistranslation, it became widely known as the Hungarian Soviet Republic in English-language sources ( hu, Magyar Szovjet-köztársaság)), literally the Republic of Councils in Hungary ( hu, Magyarországi Tanácsköztársaság) was a short-lived Communist state that existed from 21 March 1919 to 1 August 1919 (133 days), succeeding the

''Defeat and Disarmament, Allied Diplomacy and Politics of Military Affairs in Austria, 1918–1922''

Associated University Presses. p. 34.Sharp, Alan (2008)

''The Versailles Settlement: Peacemaking after the First World War, 1919–1923''

Palgrave Macmillan. p. 156. . Due to the unilateral disarmament of its army, Hungary was to remain without a national defence at a time of particular vulnerability. The Hungarian self-disarmament made the occupation of Hungary directly possible for the relatively small armies of Romania, the Franco-Serbian army and the armed forces of the newly established Czechoslovakia. On the request of the Austro-Hungarian government, an armistice was granted to Austria-Hungary on 3 November by the Allies. Military and political events changed rapidly and drastically thereafter. On 5 November, the

On 20 March, Károlyi announced that the government of Prime Minister

On 20 March, Károlyi announced that the government of Prime Minister

The government was formally led by Sándor Garbai, but Kun, as the Commissar of Foreign Affairs, held the real power because only Kun had the acquaintance and friendship with Lenin. He was the only person in the government who met and talked to the Bolshevik leader during the Russian Revolution, and Kun kept the contact with the

The government was formally led by Sándor Garbai, but Kun, as the Commissar of Foreign Affairs, held the real power because only Kun had the acquaintance and friendship with Lenin. He was the only person in the government who met and talked to the Bolshevik leader during the Russian Revolution, and Kun kept the contact with the

First Hungarian Republic

The First Hungarian Republic ( hu, Első Magyar Köztársaság), until 21 March 1919 the Hungarian People's Republic (), was a short-lived unrecognized country, which quickly transformed into a small rump state due to the foreign and military p ...

. The Hungarian Soviet Republic was a small communist rump state

A rump state is the remnant of a once much larger state, left with a reduced territory in the wake of secession, annexation, occupation, decolonization, or a successful coup d'état or revolution on part of its former territory. In the last case, ...

. When the Republic of Councils in Hungary was established, it controlled only approximately 23% of the Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

's historic territory. The head of government

The head of government is the highest or the second-highest official in the executive branch of a sovereign state, a federated state, or a self-governing colony, autonomous region, or other government who often presides over a cabinet, a gro ...

was Sándor Garbai

Sándor Garbai (27 March 1879 – 7 November 1947) was a Hungarian socialist politician who served as both head of state and prime minister of the Hungarian Soviet Republic.

Life and political career

Garbai was born in to the family of a Pro ...

, but the influence of the foreign minister

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between cou ...

Béla Kun

Béla Kun (born Béla Kohn; 20 February 1886 – 29 August 1938) was a Hungarian communist revolutionary and politician who governed the Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919. After attending Franz Joseph University at Kolozsvár (today Cluj-Napoc ...

from the Hungarian Communist Party

The Hungarian Communist Party ( hu, Magyar Kommunista Párt, abbr. MKP), known earlier as the Party of Communists in Hungary ( hu, Kommunisták Magyarországi Pártja, abbr. KMP), was a communist party in Hungary that existed during the interwar ...

was much stronger. Unable to reach an agreement with the Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French '' entente'' meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as well a ...

, which maintained an economic blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are le ...

in Hungary, tormented by neighboring countries for territorial disputes, and invested by profound internal social changes, the soviet republic failed in its objectives and was abolished a few months after its existence. Its main figure was the Communist Béla Kun, despite the fact that in the first days the majority of the new government was Socialist. The new system effectively concentrated power in the governing councils

A council is a group of people who come together to consult, deliberate, or make decisions. A council may function as a legislature, especially at a town, city or county/ shire level, but most legislative bodies at the state/provincial or nati ...

, which exercised it in the name of the working class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colou ...

.

The new regime

In politics, a regime (also "régime") is the form of government or the set of rules, cultural or social norms, etc. that regulate the operation of a government or institution and its interactions with society. According to Yale professor Juan Jo ...

failed to reach an agreement with the Triple Entente that would lead to the lifting of the economic blockade, the improvement of the new borders or the recognition of the new government by the victorious powers of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. A small volunteer army was organized mostly from Budapest factory workers and attempts were made to recover the lost territories at the hands of neighboring countries, an objective that aroused widespread support from worker class people in some larger cities, not only those more favorable to the newborn regime. Initially, thanks to patriotic support from conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

officers, the republican forces advanced against the Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

ns in Slovakia, after suffering a defeat in the east at the hands of the Romanian Army

The Romanian Land Forces ( ro, Forțele Terestre Române) is the army of Romania, and the main component of the Romanian Armed Forces. In recent years, full professionalisation and a major equipment overhaul have transformed the nature of the Lan ...

in late April, which led to a retreat on the banks of the Tisza

The Tisza, Tysa or Tisa, is one of the major rivers of Central and Eastern Europe. Once, it was called "the most Hungarian river" because it flowed entirely within the Kingdom of Hungary. Today, it crosses several national borders.

The Tisza be ...

. In mid-June, the birth of the Slovak Soviet Republic

The Slovak Soviet Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika rád, hu, Szlovák Tanácsköztársaság, uk, Словацька Радянська Республіка, literally: 'Slovak Republic of Councils') was a short-lived Communist state in sout ...

was proclaimed, which lasted two weeks until the Hungarian withdrawal at the request of the Triple Entente. On 20 July, the soviet republic launched a new attack on the Romanian posts. After a few days in advance, the Romanians managed to stop the offensive, to break through the front and reach Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population ...

, the Hungarian capital, a few days after the end of the soviet republic, which was abolished on 2 August.

The Hungarian heads of government applied controversial doctrinal measures in both foreign (internationalism instead of national interests during wartime) and domestic policy (planned economy and heightened class struggle) that made them lose the favor of the majority of the population. The attempt of the new executive to profoundly change the lifestyle and the system of values of the population proved to be a resounding failure; the effort to convert Hungary, which still had the aftermath of the Habsburg period, into a socialist society was unsuccessful due to a number of elements, namely lack of time, experienced administrative and organizational staff, as well as inexperience, both political and economic, in some of the maneuvering activities. The attempt to win the sympathies of the peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasants ...

s met with general indifference, since encouraging agricultural production and supplying the cities at the same time was not a process that could be completed in a short period of time. After the withdrawal from Slovakia, the application of some measures aimed at regaining popular support was ordered, without great success; in particular, the ban on the sale of alcoholic beverages was repealed, the delivery of some plots to peasants was planned without land, and attempts were made to improve the monetary situation and food supply. Unable to apply them, the soviet republic had already lost the support of the majority of the population between June and July, which led, together with military defeats, to its inexorable ruin. The failure of internal reform was joined by that of foreign policy; the political and economic isolation of the Triple Entente, the military failure in the face of neighboring countries and the impossibility of joining forces with the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

units contributed to the collapse of the soviet republic. The Socialist–Communist government was succeeded by an exclusively Socialist one on 1 August; the Communists left Budapest and went abroad.

Overview

When the Republic of Councils in Hungary was established in 1919, it controlled about 23% of the territory ofHungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

's previous pre-World War I territories (325 411 km2). It was the successor of the First Hungarian Republic

The First Hungarian Republic ( hu, Első Magyar Köztársaság), until 21 March 1919 the Hungarian People's Republic (), was a short-lived unrecognized country, which quickly transformed into a small rump state due to the foreign and military p ...

and lasted from 21 March to 1 August of the same year. Though the ''de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' ( ; , "by law") describes practices that are legally recognized, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. In contrast, ("in fact") describes situations that exist in reality, even if not legally ...

'' leader of the Hungarian Soviet Republic was president Sándor Garbai

Sándor Garbai (27 March 1879 – 7 November 1947) was a Hungarian socialist politician who served as both head of state and prime minister of the Hungarian Soviet Republic.

Life and political career

Garbai was born in to the family of a Pro ...

, the ''de facto

''De facto'' ( ; , "in fact") describes practices that exist in reality, whether or not they are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms. It is commonly used to refer to what happens in practice, in contrast with ''de jure'' ("by la ...

'' power was in the hands of foreign minister Béla Kun

Béla Kun (born Béla Kohn; 20 February 1886 – 29 August 1938) was a Hungarian communist revolutionary and politician who governed the Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919. After attending Franz Joseph University at Kolozsvár (today Cluj-Napoc ...

, who maintained direct contact with Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

via radiotelegraph. It was Lenin who gave the direct orders and advice to Béla Kun via constant radio communication with the Kremlin

The Kremlin ( rus, Московский Кремль, r=Moskovskiy Kreml', p=ˈmɐˈskofskʲɪj krʲemlʲ, t=Moscow Kremlin) is a fortified complex in the center of Moscow founded by the Rurik dynasty, Rurik dynasty. It is the best known of th ...

.

It was the second socialist state

A socialist state, socialist republic, or socialist country, sometimes referred to as a workers' state or workers' republic, is a Sovereign state, sovereign State (polity), state constitutionally dedicated to the establishment of socialism. The ...

in the world to be formed, preceded only by Soviet Russia

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

after the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

in Imperial Russia

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the List of Russian monarchs, Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended th ...

which brought the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

to power. The Hungarian Republic of Councils had military conflicts with the Kingdom of Romania

The Kingdom of Romania ( ro, Regatul României) was a constitutional monarchy that existed in Romania from 13 March ( O.S.) / 25 March 1881 with the crowning of prince Karl of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen as King Carol I (thus beginning the Romanian ...

, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes

Kingdom commonly refers to:

* A monarchy ruled by a king or queen

* Kingdom (biology), a category in biological taxonomy

Kingdom may also refer to:

Arts and media Television

* ''Kingdom'' (British TV series), a 2007 British television drama s ...

, and the evolving Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

. It ended on 1 August when Hungarians sent representatives to negotiate their surrender to the Romanian

Romanian may refer to:

*anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Romania

**Romanians, an ethnic group

**Romanian language, a Romance language

***Romanian dialects, variants of the Romanian language

**Romanian cuisine, traditional ...

forces. It is often referred to as the Hungarian Soviet Republic in English sources, but this is a mistranslation: the literal translation is "Republic of Councils in Hungary"; this was chosen to avoid any strong Hungarian ethnic connotation, and to express the proletarian internationalist doctrine of the new Communist regime

A communist state, also known as a Marxist–Leninist state, is a one-party state that is administered and governed by a communist party guided by Marxism–Leninism. Marxism–Leninism was the state ideology of the Soviet Union, the Cominte ...

.

World War I and the First Hungarian Republic

Political and military situation

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

's Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

monarchy collapsed in 1918, and the independent First Hungarian Republic

The First Hungarian Republic ( hu, Első Magyar Köztársaság), until 21 March 1919 the Hungarian People's Republic (), was a short-lived unrecognized country, which quickly transformed into a small rump state due to the foreign and military p ...

was formed after the Aster Revolution

The Aster Revolution or Chrysanthemum Revolution ( hu, Őszirózsás forradalom) was a revolution in Hungary led by Count Mihály Károlyi in the aftermath of World War I which resulted in the foundation of the short-lived First Hungarian Peopl ...

. The official proclamation of the republic was on 16 November and the liberal Count Mihály Károlyi

Count Mihály Ádám György Miklós Károlyi de Nagykároly ( hu, gróf nagykárolyi Károlyi Mihály Ádám György Miklós; archaically English: Michael Adam George Nicholas Károlyi, or in short simple form: Michael Károlyi; 4 March 1875 � ...

became its president. Károlyi struggled to establish the government's authority and to control the country. The Hungarian Royal Honvéd army still had more than 1,400,000 soldiers when Mihály Károlyi was announced as prime minister of Hungary. Károlyi yielded to United States president Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

's demand for pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaign ...

by ordering the unilateral

__NOTOC__

Unilateralism is any doctrine or agenda that supports one-sided action. Such action may be in disregard for other parties, or as an expression of a commitment toward a direction which other parties may find disagreeable. As a word, ''un ...

self-disarmament of the Hungarian Army

The Hungarian Ground Forces ( hu, Magyar Szárazföldi Haderő) is the land branch of the Hungarian Defence Forces, and is responsible for ground activities and troops including artillery, tanks, APCs, IFVs and ground support. Hungary's ground f ...

. This happened under the direction of Minister of War Béla Linder

Béla Linder ( Majs, 10 February 1876 – Belgrade, 15 April 1962), Hungarian colonel of artillery, Secretary of War of Mihály Károlyi government, minister without portfolio of Dénes Berinkey government, military attaché of Hungarian So ...

, on 2 November 1918.Dixon, John C. (1986)''Defeat and Disarmament, Allied Diplomacy and Politics of Military Affairs in Austria, 1918–1922''

Associated University Presses. p. 34.Sharp, Alan (2008)

''The Versailles Settlement: Peacemaking after the First World War, 1919–1923''

Palgrave Macmillan. p. 156. . Due to the unilateral disarmament of its army, Hungary was to remain without a national defence at a time of particular vulnerability. The Hungarian self-disarmament made the occupation of Hungary directly possible for the relatively small armies of Romania, the Franco-Serbian army and the armed forces of the newly established Czechoslovakia. On the request of the Austro-Hungarian government, an armistice was granted to Austria-Hungary on 3 November by the Allies. Military and political events changed rapidly and drastically thereafter. On 5 November, the

Serbian Army

The Serbian Army ( sr-cyr, Копнена војска Србије, Kopnena vojska Srbije, lit=Serbian Land Army) is the land-based and the largest component of the Serbian Armed Forces.

History

Originally established in 1830 as the Army of Pr ...

, with the help of the French Army

The French Army, officially known as the Land Army (french: Armée de Terre, ), is the land-based and largest component of the French Armed Forces. It is responsible to the Government of France, along with the other components of the Armed For ...

, crossed southern borders. On 8 November, the Czechoslovak Army

The Czechoslovak Army (Czech and Slovak: Československá armáda) was the name of the armed forces of Czechoslovakia. It was established in 1918 following Czechoslovakia's declaration of independence from Austria-Hungary.

History

In the fi ...

crossed the northern borders. On 13 November, the Romanian Army

The Romanian Land Forces ( ro, Forțele Terestre Române) is the army of Romania, and the main component of the Romanian Armed Forces. In recent years, full professionalisation and a major equipment overhaul have transformed the nature of the Lan ...

crossed the eastern borders of the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the coronation of the first king Stephen ...

. During the rule of Károlyi's pacifist cabinet, Hungary lost control over approximately 75% of its former pre-World War I territories (325 411 km²) without armed resistance and was subject to foreign occupation. For their part, the neighboring countries used the so-called "struggle against communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

", first against the capitalist and liberal government of Count Mihály Károlyi and later against the soviet republic of communist Bela Kun, as a justification for their expansionist

Expansionism refers to states obtaining greater territory through military empire-building or colonialism.

In the classical age of conquest moral justification for territorial expansion at the direct expense of another established polity (who of ...

ambitions.

Formation of the Communist party

An initial nucleus of aHungarian Communist Party

The Hungarian Communist Party ( hu, Magyar Kommunista Párt, abbr. MKP), known earlier as the Party of Communists in Hungary ( hu, Kommunisták Magyarországi Pártja, abbr. KMP), was a communist party in Hungary that existed during the interwar ...

had been organized in a hotel on 4 November 1918, when a group of Hungarian prisoners of war and other communist proponents formed a Central Committee in Moscow. Led by Béla Kun

Béla Kun (born Béla Kohn; 20 February 1886 – 29 August 1938) was a Hungarian communist revolutionary and politician who governed the Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919. After attending Franz Joseph University at Kolozsvár (today Cluj-Napoc ...

, the inner circle of the freshly established party returned to Budapest from Moscow on 16 November. On 24 November, they created the Party of Communists from Hungary (Hungarian: ''Kommunisták Magyarországi Pártja'', KMP). The name was chosen instead of the Hungarian Communist Party because the vast majority of supporters were from the urban industrial working class in Hungary which at the time was largely made up of people from non-Hungarian ethnic backgrounds, with ethnic Hungarians a minority in the new party itself. The party recruited members while propagating its ideas, radicalising many members of the Social Democratic Party of Hungary

The Social Democratic Party of Hungary ( hu, Magyarországi Szociáldemokrata Párt, MSZDP) is a social democratic political party in Hungary. Historically, the party was dissolved during the occupation of Hungary by Nazi Germany (1944–1945) ...

in the process. By February 1919, the party numbered 30,000 to 40,000 members, including many unemployed ex-soldiers, young intellectuals and ethnic minorities.

Kun founded a newspaper, called ''Vörös Újság'' (''Red News'') and concentrated on attacking Károlyi's liberal government. The party became popular among the Budapest proletariat, it also promised that Hungary would be able to defend its territory even without conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

. Kun promised military help and intervention of the Soviet Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

, which never came, against non-communist Romanian, Czechoslovak, French and Yugoslav forces. During the following months, the Communist party's power-base rapidly expanded. Its supporters began to stage aggressive demonstrations against the media and against the Social Democratic Party. The Communists considered the Social Democrats as their main rivals, because the Social Democrats recruited their political supporters from the same social class: the industrial working class of the cities. In one crucial incident, a demonstration turned violent on 20 February and the protesters attacked the editorial office of the Social Democratic Party of Hungary's official newspaper called ''Népszava

''Népszava'' (meaning "People's Word" in English) is a social-democratic Hungarian language newspaper published in Hungary.

History and profile

''Népszava'' is Hungary's eldest continuous print publication and as of October 2019 the last and ...

'' (''People's Word''). In the ensuing chaos, seven people, some policemen, were killed. The government arrested the leaders of the Communist party, banned its daily newspaper ''Vörös Újság'', and closed down the party's buildings. The arrests were particularly violent, with police officers openly beating the communists. This resulted in a wave of public sympathy for the party among the masses of Budapester proletariat. On 1 March, ''Vörös Újság'' was given permission to publish again, and the Communist party's premises were re-opened. The leaders were permitted to receive guests in prison, which allowed them to keep up with political affairs.

Communist rule

Coup d'état

On 20 March, Károlyi announced that the government of Prime Minister

On 20 March, Károlyi announced that the government of Prime Minister Dénes Berinkey

Dénes Berinkey (17 October 1871 – 25 June 1944) was a Hungarian jurist and politician who served as 21st Prime Minister of Hungary in the regime of Mihály Károlyi for two months in 1919.

On 20 March 1919 the French presented the Vix Note ...

would resign. The presentation of the Vix Note

The Vix Note or Vyx Note ( hu, Vix-jegyzék or ) was a communication note sent by (or Vyx), a French lieutenant colonel and delegate of the Entente, to the government of Mihály Károlyi of the First Hungarian Republic of the alliance's intention ...

led to the fall of the liberal Count Mihály Károlyi

Count Mihály Ádám György Miklós Károlyi de Nagykároly ( hu, gróf nagykárolyi Károlyi Mihály Ádám György Miklós; archaically English: Michael Adam George Nicholas Károlyi, or in short simple form: Michael Károlyi; 4 March 1875 � ...

's government, which was by then devoid of significant support. Károlyi and Berinkey had been placed in an untenable situation when they received a note from Paris ordering Hungarian troops to further withdraw their lines. It was widely assumed that the new military lines would be the postwar boundaries. Károlyi and Berinkey concluded that they were not in a position to reject the note although they believed that accepting it would endanger Hungary's territorial integrity. On 21 March, Károlyi informed the Council of Ministers that only Social Democrats could form a new government, as they were the party with the highest public support in the largest cities and especially in Budapest. To form a governing coalition, the Social Democrats started secret negotiations with the Communist leaders, who were still imprisoned, and decided to merge their two parties under the name of the Hungarian Socialist Party. President Károlyi, who was an outspoken anticommunist, was not informed about the merger. Thus, he swore in what he believed to be a Social Democratic government, only to find himself faced with one dominated by Communists. Károlyi resigned on 21 March. Béla Kun and his fellow communists were released from the Margit Ring prison on the night of 20 March. The liberal president Károlyi was arrested by the new Communist government on the first day; in July, he managed to make his escape and flee to Paris.

For the Social Democrats, an alliance with the KMP not only increased their standing with the industrial working class but also gave them a potential link to the increasingly powerful Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks)

"Hymn of the Bolshevik Party"

, headquarters = 4 Staraya Square, Moscow

, general_secretary = Vladimir Lenin (first) Mikhail Gorbachev (last)

, founded =

, banned =

, founder = Vladimir Lenin

, newspaper ...

, as Kun had strong ties with prominent Russian Bolsheviks. Following Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

's model but without the direct participation of the workers' council

A workers' council or labor council is a form of political and economic organization in which a workplace or municipality is governed by a council made up of workers or their elected delegates. The workers within each council decide on what thei ...

s (soviets) from which it took its name, the newly united Socialist Party created a government called the Revolutionary Governing Council, which proclaimed the Hungarian Soviet Republic and dismissed President Károlyi on 21 March. In a radio dispatch to the Russian SFSR

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

, Kun informed Lenin that a dictatorship of the proletariat

In Marxist philosophy, the dictatorship of the proletariat is a condition in which the proletariat holds state power. The dictatorship of the proletariat is the intermediate stage between a capitalist economy and a communist economy, whereby the ...

had been established in Hungary and asked for a treaty of alliance with the Russian SFSR. The Russian SFSR refused because it was itself tied down in the Russian Civil War

, date = October Revolution, 7 November 1917 – Yakut revolt, 16 June 1923{{Efn, The main phase ended on 25 October 1922. Revolt against the Bolsheviks continued Basmachi movement, in Central Asia and Tungus Republic, the Far East th ...

. On 23 March, Lenin gave an order to Béla Kun that Social Democrats must be removed from power, so that Hungary could be transformed into a socialist state ruled by a "dictatorship of the proletariat". Accordingly, the Communists started to purge the Social Democrats from the government on the next day.

Garbai government

The government was formally led by Sándor Garbai, but Kun, as the Commissar of Foreign Affairs, held the real power because only Kun had the acquaintance and friendship with Lenin. He was the only person in the government who met and talked to the Bolshevik leader during the Russian Revolution, and Kun kept the contact with the

The government was formally led by Sándor Garbai, but Kun, as the Commissar of Foreign Affairs, held the real power because only Kun had the acquaintance and friendship with Lenin. He was the only person in the government who met and talked to the Bolshevik leader during the Russian Revolution, and Kun kept the contact with the Kremlin

The Kremlin ( rus, Московский Кремль, r=Moskovskiy Kreml', p=ˈmɐˈskofskʲɪj krʲemlʲ, t=Moscow Kremlin) is a fortified complex in the center of Moscow founded by the Rurik dynasty, Rurik dynasty. It is the best known of th ...

via radio communication. The ministries, often rotated among the various members of the government, were:

* Sándor Garbai

Sándor Garbai (27 March 1879 – 7 November 1947) was a Hungarian socialist politician who served as both head of state and prime minister of the Hungarian Soviet Republic.

Life and political career

Garbai was born in to the family of a Pro ...

president and prime minister of the Hungarian Soviet Republic

* Jenő Landler commissar of the interior

* Sándor Csizmadia, Károly Vántus

Károly Vántus (20 February 1879 – 16 June 1927) was a Hungarians, Hungarian politician and carpenter, who served as Minister of Agriculture, People's Commissar of Agriculture during the Hungarian Soviet Republic. He was a founding member of ...

, Jenő Hamburger, and György Nyisztor – commissars of agriculture

* József Pogány

John Pepper, also known as József Pogány and Joseph Pogany (born József Schwartz; November 8, 1886 – February 8, 1938), was a Hungarian Communist politician. He later served as a functionary in the Communist International (Comintern) in Mos ...

, later also Rezső Fiedler, József Haubrich and Béla Szántó – commissars of Defense

* Zoltán Rónai, later also István Láday – commissars of Justice

* Jenő Landler – commissar of trade

* Mór Erdélyi

Mór (german: Moor) is a town in Fejér County, Hungary. Among the smaller towns in the Central Transdanubia Region of Hungary, it lies between the Vértes and Bakony Hills, in the northwestern corner of Fejér County. The historic roots of th ...

, later also Bernát Kondor – commissars of food

* Zsigmond Kunfi

Zsigmond Kunfi (born as Zsigmond Kohn; 28 April 1879 – 18 November 1929) was a Hungarian politician, literary historian, journalist and translator, who served as Minister without portfolio of Croatian Affairs and as Minister of Labour and We ...

, later also György Lukács

György Lukács (born György Bernát Löwinger; hu, szegedi Lukács György Bernát; german: Georg Bernard Baron Lukács von Szegedin; 13 April 1885 – 4 June 1971) was a Hungarian Marxist philosopher, literary historian, critic, and ae ...

, Tibor Szamuely

Tibor Szamuely (December 27, 1890 – August 2, 1919) was a Hungarian politician and journalist who was Deputy People's Commissar of War and People's Commissar of Public Education during the Hungarian Soviet Republic.

Early life

Born in N ...

, and Sándor Szabados – commissars of education

* Béla Kun – commissar of foreign affairs

* Dezső Bokányi – commissar of labor

* Henrik Kalmár

Henrik Kalmár (born Elkán Kohn; 25 March 1870 – 23 June 1931) was a Hungarian politician, printer, and Social Democrat party secretary.

Biography

Kalmár was born into a Jewish family in Pozsony (now Bratislava) on 25 March 1870, his father w ...

– commissar of German affairs

* Jenő Varga

Eugen Samuilovich "Jenő" Varga (born as Eugen Weisz, November 6, 1879 in Budapest – October 7, 1964 in Moscow) was a Soviet economist of Hungarian origin.

Biography Early years

He was born as Jenő Weiß (Hungarian orthography: Weisz) in a p ...

, later also Gyula Lengyel

Gyula Lengyel (born Gyula Goldstein;The number and year of the Ministry of Interior Decree containing the license are: 82212/1903. MNL-OL 30799. Microfilm Image 1006. 1. Carton, Name Change Statements in 1903, p. 14 Row 18 8 October 1888 – 8 ...

– commissars of Finance

* Vilmos Böhm

Vilmos Böhm or Wilhelm Böhm ( hu, Böhm (improperly Bőhm) Vilmos; 6 January 1880, Budapest – 28 October 1949) was a Hungarian Social Democrat and Hungary's ambassador to Sweden after World War II.

He was born in a middle class Jewis ...

– commissar for socialism, later also Antal Dovcsák

Antal Dovcsák (March 11, 1879 – 1962) was a Hungarians, Hungarian Communism, Communist politician and trade union leader.

Biography

Dovcsák was born in Budapest and was a lathe worker. From 1911 he was the president of the Central Associat ...

After the declaration of the constitution changes took place in the commissariat. The new ministries were:

* Jenő Varga, Mátyás Rákosi

Mátyás Rákosi (; born Mátyás Rosenfeld; 9 March 1892

– 5 February 1971) was a Hungarian , Gyula Hevesi,

The Hungarian government was left on its own, and a Red Guard was established under the command of

The Hungarian government was left on its own, and a Red Guard was established under the command of

– 5 February 1971) was a Hungarian , Gyula Hevesi,

József Kelen József Kelen (Born: József Klein Nagybocskó; January 12, 1892 – March 19, 1938 in Moscow) was a Hungarian mechanical engineer, deputy commissar of the Soviet republic of Hungary, then commissar of the Soviet republic of Hungary, brother of co ...

, Ferenc Bajáki – commissars of economic production

* Jenő Landler, Béla Vágó

Béla Vágó (born ''Béla Weiss''; 9 August 1881 in Kecskemét – 10 March 1939) was a Hungarian communist politician, who served as ''de facto'' Interior Minister with Jenő Landler during the Hungarian Soviet Republic. After the fall ...

– commissars of internal affairs, railways and navigation

* Béla Kun, Péter Ágoston and József Pogány

John Pepper, also known as József Pogány and Joseph Pogany (born József Schwartz; November 8, 1886 – February 8, 1938), was a Hungarian Communist politician. He later served as a functionary in the Communist International (Comintern) in Mos ...

– commissars of Foreign Affairs

Policies

This government consisted of a coalition of socialists and communists, but with the exception of Kun, all commissars were former social democrats. Under the rule of Kun, the new government, which had adopted in full the program of the Communists, decreed the abolition of aristocratic titles and privileges, theseparation of church and state

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the state. Conceptually, the term refers to the creation of a secular sta ...

, codified freedom of assembly

Freedom of peaceful assembly, sometimes used interchangeably with the freedom of association, is the individual right or ability of people to come together and collectively express, promote, pursue, and defend their collective or shared ide ...

and freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The right to freedom of expression has been recogni ...

, and implemented free education and language and cultural rights to minorities.

The Communist government also nationalized industrial and commercial enterprises and socialized housing, transport, banking, medicine, cultural institutions, and all landholdings of more than 40 hectare

The hectare (; SI symbol: ha) is a non-SI metric unit of area equal to a square with 100-metre sides (1 hm2), or 10,000 m2, and is primarily used in the measurement of land. There are 100 hectares in one square kilometre. An acre is a ...

s. Public support for the Communists was also heavily dependent on their promise of restoring Hungary's former borders. The government took steps toward normalizing foreign relations with the Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French '' entente'' meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as well a ...

powers in an effort to gain back some of the lands that Hungary was set to lose in the post-war negotiations. The Communists remained bitterly unpopular in the Hungarian countryside, where the authority of that government was often nonexistent. The Communist party and their policies had real popular support among only the proletarian masses of large industrial centers, especially in Budapest, where the working class represented a high proportion of the inhabitants.

The Hungarian government was left on its own, and a Red Guard was established under the command of

The Hungarian government was left on its own, and a Red Guard was established under the command of Mátyás Rákosi

Mátyás Rákosi (; born Mátyás Rosenfeld; 9 March 1892

– 5 February 1971) was a Hungarian . In addition, a group of 200 armed men known as the Lenin Boys formed a mobile detachment under the leadership of

Béla Kun, together with other high-ranking Communists, fled to Vienna on 1 August with only a minority, including

Béla Kun, together with other high-ranking Communists, fled to Vienna on 1 August with only a minority, including "2000 – Bűn És Bűnhődés"

Kun himself, along with an unknown number of other Hungarian communists, was executed during

– 5 February 1971) was a Hungarian . In addition, a group of 200 armed men known as the Lenin Boys formed a mobile detachment under the leadership of

József Cserny

__NOTOC__

The Lenin Boys ( hu, Lenin-fiúk) were the paramilitary of the Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919. The group consisted of about 800.000 soldiers, it was a formed subdivision of the Soviet Army. Their unit commander was . The Lenin Boys ...

. This detachment was deployed at various locations around the country where counter-revolutionary

A counter-revolutionary or an anti-revolutionary is anyone who opposes or resists a revolution, particularly one who acts after a revolution in order to try to overturn it or reverse its course, in full or in part. The adjective "counter-revoluti ...

movements were suspected to operate. The Lenin Boys as well as other similar groups and agitators killed and terrorised many people (e.g. armed with hand grenades and using their rifles' butts they disbanded religious ceremonies). They executed victims without trial, and this caused a number of conflicts with the local population, some of which turned violent. The situation of the Hungarian Communists began to deteriorate in the capital city Budapest after a failed coup by the Social Democrats on 24 June; the newly composed Communist government of Sándor Garbai resorted to large-scale reprisals. Revolutionary tribunals ordered executions of people who were suspected of having been involved in the attempted coup. This became known as the Red Terror

The Red Terror (russian: Красный террор, krasnyj terror) in Soviet Russia was a campaign of political repression and executions carried out by the Bolsheviks, chiefly through the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police. It started in lat ...

, and greatly reduced domestic support for the government even among the working classes of the highly industrialized suburb districts and metropolitan area of Budapest.

Foreign policy scandal and downfall

In late May, after the Entente military representative demanded more territorial concessions from Hungary, Kun attempted to fulfill his promise to adhere to Hungary's historical borders. The men of the Hungarian Red Army were recruited from the volunteers of the Budapest proletariat. In June, the Hungarian Red Army invaded the eastern part of the newly forming Czechoslovak state (today'sSlovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the s ...

), the former so-called Upper Hungary

Upper Hungary is the usual English translation of ''Felvidék'' (literally: "Upland"), the Hungarian term for the area that was historically the northern part of the Kingdom of Hungary, now mostly present-day Slovakia. The region has also been ...

. The Hungarian Red Army achieved some military success early on: under the leadership of Colonel Aurél Stromfeld

Aurél Stromfeld (September 19, 1878, Budapest – October 10, 1927, Budapest) was a Hungarian general, commander-in-chief of the Hungarian Red Army during the Hungarian Soviet Republic. He had a major role in temporarily pressing back the Czech ...

, it ousted Czech troops from the north, and planned to march against the Romanian Army

The Romanian Land Forces ( ro, Forțele Terestre Române) is the army of Romania, and the main component of the Romanian Armed Forces. In recent years, full professionalisation and a major equipment overhaul have transformed the nature of the Lan ...

in the east. Despite promises for the restoration of the former borders of Hungary, the Communists declared the establishment of the Slovak Soviet Republic

The Slovak Soviet Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika rád, hu, Szlovák Tanácsköztársaság, uk, Словацька Радянська Республіка, literally: 'Slovak Republic of Councils') was a short-lived Communist state in sout ...

in Prešov

Prešov (, hu, Eperjes, Rusyn language, Rusyn and Ukrainian language, Ukrainian: Пряшів) is a city in Eastern Slovakia. It is the seat of administrative Prešov Region ( sk, Prešovský kraj) and Šariš, as well as the historic Sáros Cou ...

on 16 June.

After the proclamation of the Slovak Soviet Republic, the Hungarian nationalists and patriots soon realized that the new communist government had no intention of recapturing the lost territories, only in spreading communist ideology and the establishment of other communist states in Europe, thus sacrificing Hungarian national interests. The Hungarian patriots in the Red Army and the professional military officers saw this as a betrayal, and their support for the government began to erode (the communists and their government supported the establishment of the Slovak Communist state, while the Hungarian patriots wanted to keep the reoccupied territories for Hungary). Despite a series of military victories against the Czechoslovak army, the Hungarian Red Army started to disintegrate due to tension between nationalists and communists during the establishment of the Slovak Soviet Republic. The concession eroded support of the communist government among professional military officers and nationalists in the Hungarian Red Army; even the chief of the general staff The Chief of the General Staff (CGS) is a post in many armed forces (militaries), the head of the military staff.

List

* Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (United States)

* Chief of the General Staff (Abkhazia)

* Chief of General Staff (Afg ...

Aurél Stromfeld, resigned his post in protest.

When the French promised the Hungarian government that Romanian forces would withdraw from the Tiszántúl

Tiszántúl or Transtisza (literal meaning: "beyond Tisza") is a geographical region of which lies between the Tisza river, Hungary and the Apuseni Mountains, Romania, bordered by the Maros (Mureș) river. Alongside Kiskunság, it is a part of Gre ...

, Kun withdrew his remaining military units who had remained loyal after the political fiasco in Upper Hungary; however, following the Red Army's retreat from the north, the Romanian forces were not pulled back. Kun then unsuccessfully tried to turn the remaining units of the demoralized Hungarian Red Army on the Romanians with Hungarian-Romanian War of 1919. The Hungarian Soviet found it increasingly difficult to fight Romania with its small force of communist volunteers from Budapest, and support for both the war and the Communist party was waning at home. After the demoralizing retreat from northern Hungary (later part of Czechoslovakia), only the most dedicated Hungarian Communists volunteered for combat, and the Romanian Army broke through the weak lines of the Hungarian Red Army on 30 July.

Béla Kun, together with other high-ranking Communists, fled to Vienna on 1 August with only a minority, including

Béla Kun, together with other high-ranking Communists, fled to Vienna on 1 August with only a minority, including György Lukács

György Lukács (born György Bernát Löwinger; hu, szegedi Lukács György Bernát; german: Georg Bernard Baron Lukács von Szegedin; 13 April 1885 – 4 June 1971) was a Hungarian Marxist philosopher, literary historian, critic, and ae ...

, the former Commissar for Culture and noted Marxist philosopher, remaining to organise an underground Communist party. Before they fled to Vienna, Kun and his followers took along numerous art treasures and the gold stocks of the National Bank. The Budapest Workers' Soviet elected a new government, headed by Gyula Peidl

Gyula Peidl (4 April 1873 – 22 January 1943) was a Hungarian trade union leader and social democrat politician who served as prime minister and acting head of state of Hungary for 6 days in August 1919. His tenure coincided with a period ...

, which lasted only a few days before Romanian forces entered Budapest on 6 August.

In the power vacuum created by the fall of the soviet republic and the presence of the Romanian Army, semi-regular detachments (technically under Horthy's command, but mostly independent in practice) initiated a campaign of violence against communists, leftists

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

, and Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""Th ...

s, known as the White Terror

White Terror is the name of several episodes of mass violence in history, carried out against anarchists, communists, socialists, liberals, revolutionaries, or other opponents by conservative or nationalist groups. It is sometimes contrasted wit ...

. Many supporters of the Hungarian Soviet Republic were executed without trial; others, including Péter Ágoston, Ferenc Bajáki, Dezső Bokányi, Antal Dovcsák

Antal Dovcsák (March 11, 1879 – 1962) was a Hungarians, Hungarian Communism, Communist politician and trade union leader.

Biography

Dovcsák was born in Budapest and was a lathe worker. From 1911 he was the president of the Central Associat ...

, József Haubrich, Kalmár Henrik Kalmar or Kalmár is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Bert Kalmar (1884-1947), American songwriter

* Carlos Kalmar (born 1958), Uruguayan conductor

* Ferenc Kalmár (born 1955), Hungarian physicist and politician

* Henrik Kal ...

, Kelen József

Kelen may refer to:

* Kēlen, a constructed language

* Kelen, a surname; notable people include:

** Christopher Kelen (born 1958), Australian academic, writer and artist

** István Kelen (1912–2003),Hungarian table tennis player, journalist an ...

, György Nyisztor, Sándor Szabados, and Károly Vántus

Károly Vántus (20 February 1879 – 16 June 1927) was a Hungarians, Hungarian politician and carpenter, who served as Minister of Agriculture, People's Commissar of Agriculture during the Hungarian Soviet Republic. He was a founding member of ...

, were imprisoned by trial ("comissar suits"). Actor Bela Lugosi

Béla Ferenc Dezső Blaskó (; October 20, 1882 – August 16, 1956), known professionally as Bela Lugosi (; ), was a Hungarian and American actor best remembered for portraying Count Dracula in the 1931 horror classic ''Dracula'', Ygor in ''S ...

, the founder of the country's National Trade Union of Actors (the world's first film actor's union), managed to escape. Most were later released to the Soviet Union by amnesty during the reign of Horthy, after a prisoner exchange agreement between Hungary and the Russian Soviet government in 1921. In all, about 415 prisoners were released as a result of this agreement.Kun himself, along with an unknown number of other Hungarian communists, was executed during

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

's Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Nikolay Yezhov, Yezhov'), was General ...

of the late 1930s in the Soviet Union, to which they had fled in the 1920s. Rákosi, one of the survivors of the soviet republic, would go on to be the first leader of the second and longer-lasting attempt at a Communist state

A communist state, also known as a Marxist–Leninist state, is a one-party state that is administered and governed by a communist party guided by Marxism–Leninism. Marxism–Leninism was the state ideology of the Soviet Union, the Comint ...

in Hungary, the People's Republic of Hungary

The Hungarian People's Republic ( hu, Magyar Népköztársaság) was a one-party socialist state from 20 August 1949

to 23 October 1989.

It was governed by the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party, which was under the influence of the Soviet Uni ...

, from 1949 to 1956.

See also

*Aftermath of World War I

The aftermath of World War I saw drastic political, cultural, economic, and social change across Eurasia, Africa, and even in areas outside those that were directly involved. Four empires collapsed due to the war, old countries were abolished, ne ...

* Hungarian Revolution of 1956

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 (23 October – 10 November 1956; hu, 1956-os forradalom), also known as the Hungarian Uprising, was a countrywide revolution against the government of the Hungarian People's Republic (1949–1989) and the Hunga ...

* Red Terror

The Red Terror (russian: Красный террор, krasnyj terror) in Soviet Russia was a campaign of political repression and executions carried out by the Bolsheviks, chiefly through the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police. It started in lat ...

*Hungarian Red Terror

The Red Terror in Hungary ( hu, vörösterror) was a period of repressive violence and suppression in 1919 during the four-month period of the Hungarian Soviet Republic, primarily towards anti-communists, anti-communist forces, and others deem ...

* Revolutions of 1917–1923

The Revolutions of 1917–1923 was a revolutionary wave that included political unrest and armed revolts around the world inspired by the success of the Russian Revolution and the disorder created by the aftermath of World War I. The uprisings ...

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* György Borsányi, ''The life of a Communist revolutionary, Bela Kun'' translated by Mario Fenyo, Boulder, Colorado: Social Science Monographs, 1993. * Andrew C. Janos and William Slottman (editors), ''Revolution in Perspective: Essays on the Hungarian Soviet Republic of 1919.'' Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1971. * Bennet Kovrig, ''Communism in Hungary: From Kun to Kádár.'' Stanford University: Hoover Institution Press, 1979. * Bela Menczer, "Bela Kun and the Hungarian Revolution of 1919," ''History Today,'' vol. 19, no. 5 (May 1969), pp. 299–309. * Peter Pastor, ''Hungary between Wilson and Lenin: The Hungarian Revolution of 1918–1919 and the Big Three.'' Boulder, CO: East European Quarterly, 1976. * Thomas L. Sakmyster, ''A Communist Odyssey: The Life of József Pogány.'' Budapest: Central European University Press, 2012. * Rudolf Tokes, ''Béla Kun and the Hungarian Soviet Republic: The Origins and Role of the Communist Party of Hungary in the Revolutions of 1918–1919.'' New York: F.A. Praeger, 1967. * Bob Dent, ''Painting the Town Red: Politics and the Arts During the 1919 Hungarian Soviet Republic''. Pluto Press, 2018External links

* * ** {{authority control 20th century rump states 1919 establishments in Hungary 1919 disestablishments in Hungary 1919 in Hungary Aftermath of World War I in Hungary Communism in Hungary Early Soviet republics Former countries in Europe Former countries of the interwar periodHungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

Hungary–Soviet Union relations

States and territories established in 1919

States and territories disestablished in 1919

Territorial evolution of Hungary