Retirement Ceremony (16893212697) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Retirement is the withdrawal from one's position or occupation or from one's active working life. A person may also semi-retire by reducing work hours or workload.

Many people choose to retire when they are elderly or incapable of doing their job due to health reasons. People may also retire when they are eligible for private or public pension benefits, although some are forced to retire when bodily conditions no longer allow the person to work any longer (by illness or accident) or as a result of legislation concerning their positions. In most countries, the idea of retirement is of recent origin, being introduced during the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. Previously, low life expectancy, lack of social security and the absence of pension arrangements meant that most workers continued to work until their death. Germany was the first country to introduce retirement benefits in 1889.

Nowadays, most developed countries have systems to provide pensions on retirement in

(page 8) In consequence, only a small percentage of the population reached an age where physical impairments began to be obstacles to working. Countries began to adopt government policies on retirement during the late 19th century and the 20th century, beginning in Germany under

old age

Old age refers to ages nearing or surpassing the life expectancy of human beings, and is thus the end of the human life cycle. Terms and euphemisms for people at this age include old people, the elderly (worldwide usage), OAPs (British usage ...

, funded by employers or the state. In many poorer countries, there is no support for the elderly beyond that provided through the family. Today, retirement with a pension is considered a right of the worker in many societies; hard ideological, social, cultural and political battles have been fought over whether this is a right. In many Western countries, this is a right embodied in national constitutions.

An increasing number of individuals are choosing to put off this point of total retirement, by selecting to exist in the emerging state of pre-tirement

The neologism pre-tirement describes the emergence of a new working state, positioned between the traditional states of employment and retirement. The word is a portmanteau word, coming from the prefix "pre" and the word "retirement." The state ...

.

History

Retirement, or the practice of leaving one's job or ceasing to work after reaching a certain age, has been around since around the 18th century. Prior to the 18th century, humans had an average life expectancy between 26 and 40 years."Expectations of Life" by H.O. Lancaster(page 8) In consequence, only a small percentage of the population reached an age where physical impairments began to be obstacles to working. Countries began to adopt government policies on retirement during the late 19th century and the 20th century, beginning in Germany under

Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (, ; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of J ...

.

In specific countries

A person may retire at whatever age they please. However, a country's tax laws or state old-age pension rules usually mean that in a given country a certain age is thought of as the standard retirement age. As life expectancy increases and more and more people live to an advanced age, in many countries the age at which a pension is awarded has been increased in the 21st century, often progressively. The standard retirement age varies from country to country but it is generally between 50 and 70 (according to latest statistics, 2011). In some countries this age is different for men and women, although this has recently been challenged in some countries (e.g., Austria), and in some countries the ages are being brought into line. The table below shows the variation in eligibility ages for public old-age benefits in the United States and many European countries, according to the OECD. ''The retirement age in many countries is increasing, often starting in the 2010s and continuing until the late 2020s.'' Notes: Parentheses indicate eligibility age for women when different. Sources: Cols. 1–2: OECD Pensions at a Glance (2005), Cols. 3–6: Tabulations from HRS, ELSA and SHARE. Square brackets indicate early retirement for some public employees. 1 In Denmark, early retirement is called ''efterløn'' and there are some requirements to be met. Early and normal retirement ages vary according to the date of birth of the person filing for retirement. 2 In France, the retirement age was 60, with full pension entitlement at 65; in 2010 this was extended to 62 and 67 respectively, increasing progressively over the following eight years. 3 In Latvia, the retirement age depends on the date of birth of the person filing for retirement. 4 In Spain it was ruled that the retirement age was to increase from 65 to 67 progressively from 2013 to 2027. In the United States, while the normal retirement age for Social Security, or Old Age Survivors Insurance (OASI) was age 65 to receive unreduced benefits, it is gradually increasing to age 67 by 2027. Public servants are often not covered by Social Security but have their own pension programs. Police officers in the United States may typically retire at half pay after 20 years of service, or three-quarter pay after 30 years, allowing retirement from the early forties. Military members of the US Armed Forces may elect to retire after 20 years of active duty. Their retirement pay (not a pension since they can be recalled to active duty at any time) is calculated on number of years on active duty, final pay grade and the retirement system in place when they entered service. Members awarded the Medal of Honor qualify for a separate stipend. Retirement pay for military members in the reserve andUS National Guard

The National Guard is a state-based military force that becomes part of the reserve components of the United States Army and the United States Air Force when activated for federal missions.Health and Retirement Study (HRS), first fielded in 1992. The HRS is a nationally representative longitudinal survey of adults in the U.S. ages 51+, conducted every two years, and contains a wealth of information on such topics as labor force participation (e.g., current employment, job history, retirement plans, industry/occupation, pensions, disability), health (e.g., health status and history, health and

Many individuals use "retirement calculators" on the Internet to determine the proportion of their pay they should be saving in a tax advantaged-plan (e.g., IRA or 401-K in the US, RRSP in Canada, personal pension in the UK, superannuation in Australia).

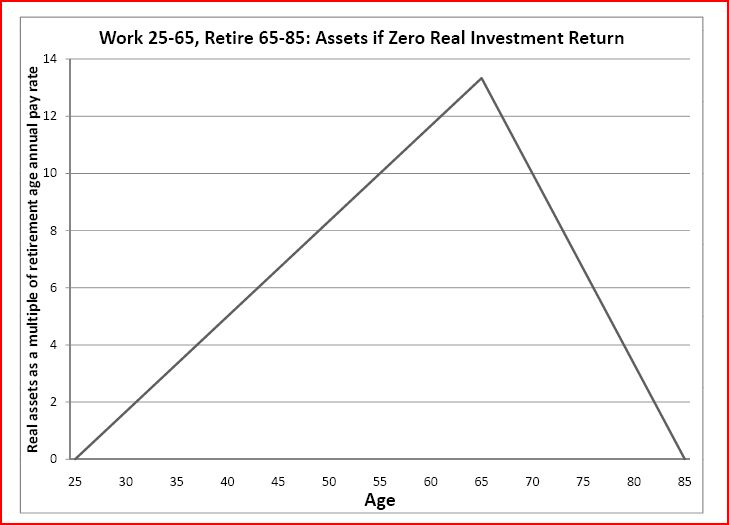

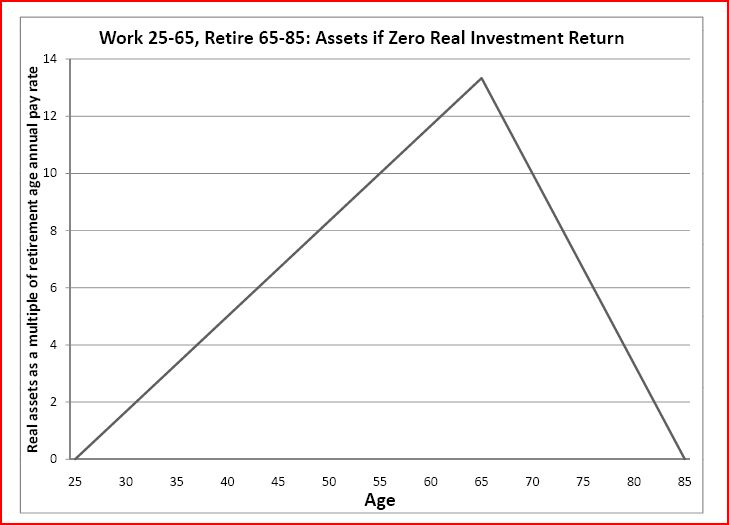

After expenses and any taxes, a reasonable (though arguably pessimistic) long-term assumption for a safe real rate of return is zero. So in real terms, interest does not help the savings grow. Each year of work must pay its share of a year of retirement. For someone planning to work for 40 years and be retired for 20 years, each year of work pays for itself and for half a year of retirement. Hence, 33.33% of pay must be saved, and 66.67% can be spent when earned. After 40 years of saving 33.33% of pay, we have accumulated assets of 13.33 years of pay, as in the graph. In the graph to the right, the lines are straight, which is appropriate given the assumption of a zero real investment return.

The graph above can be compared with those generated by many retirement calculators. However, most retirement calculators use nominal (not "real" dollars) and therefore require a projection of both the expected inflation rate and the expected nominal rate of return. One way to work around this limitation is to, for example, enter "0% return, 0% inflation" inputs into the calculator. The Bloomberg retirement calculator gives the flexibility to specify, for example, zero inflation and zero investment return and to reproduce the graph above. The MSN retirement calculator in 2011 has as the defaults a realistic 3% per annum inflation rate and optimistic 8% return assumptions; consistency with the December 2011 US nominal bond and inflation-protected bond market rates requires a change to about 3% inflation and 4% investment return before and after retirement.

Ignoring tax, someone wishing to work for a year and then relax for a year on the same living standard needs to save 50% of pay. Similarly, someone wishing to work from age 25 to 55 and be retired for 30 years till 85 needs to save 50% of pay if government and employment pensions are not a factor and if it is considered appropriate to assume a zero real investment return. The problem that the lifespan is not known in advance can be reduced in some countries by the purchase at retirement of an inflation-indexed

Many individuals use "retirement calculators" on the Internet to determine the proportion of their pay they should be saving in a tax advantaged-plan (e.g., IRA or 401-K in the US, RRSP in Canada, personal pension in the UK, superannuation in Australia).

After expenses and any taxes, a reasonable (though arguably pessimistic) long-term assumption for a safe real rate of return is zero. So in real terms, interest does not help the savings grow. Each year of work must pay its share of a year of retirement. For someone planning to work for 40 years and be retired for 20 years, each year of work pays for itself and for half a year of retirement. Hence, 33.33% of pay must be saved, and 66.67% can be spent when earned. After 40 years of saving 33.33% of pay, we have accumulated assets of 13.33 years of pay, as in the graph. In the graph to the right, the lines are straight, which is appropriate given the assumption of a zero real investment return.

The graph above can be compared with those generated by many retirement calculators. However, most retirement calculators use nominal (not "real" dollars) and therefore require a projection of both the expected inflation rate and the expected nominal rate of return. One way to work around this limitation is to, for example, enter "0% return, 0% inflation" inputs into the calculator. The Bloomberg retirement calculator gives the flexibility to specify, for example, zero inflation and zero investment return and to reproduce the graph above. The MSN retirement calculator in 2011 has as the defaults a realistic 3% per annum inflation rate and optimistic 8% return assumptions; consistency with the December 2011 US nominal bond and inflation-protected bond market rates requires a change to about 3% inflation and 4% investment return before and after retirement.

Ignoring tax, someone wishing to work for a year and then relax for a year on the same living standard needs to save 50% of pay. Similarly, someone wishing to work from age 25 to 55 and be retired for 30 years till 85 needs to save 50% of pay if government and employment pensions are not a factor and if it is considered appropriate to assume a zero real investment return. The problem that the lifespan is not known in advance can be reduced in some countries by the purchase at retirement of an inflation-indexed

The chart at the right shows the year-to-year portfolio balances after taking $35,000 (and adjusting for inflation) from a $750,000 portfolio every year for 30 years, starting in 1973 (red line), 1974 (blue line), or 1975 (green line). While the overall market conditions and inflation affected all three about the same (since all three experienced exactly the same conditions between 1975 and 2003), the chance of making the funds last for 30 years depended heavily on what happened to the

The chart at the right shows the year-to-year portfolio balances after taking $35,000 (and adjusting for inflation) from a $750,000 portfolio every year for 30 years, starting in 1973 (red line), 1974 (blue line), or 1975 (green line). While the overall market conditions and inflation affected all three about the same (since all three experienced exactly the same conditions between 1975 and 2003), the chance of making the funds last for 30 years depended heavily on what happened to the

''RETIREMENT HEIST: How Companies Plunder and Profit from the Nest Eggs of American Workers"

Penguin Publishing, 2011 * *

"Historical Development"

Social Security Administration * Short, Joanna

"Economic History of Retirement in the U.S."

2010-02-01,

life insurance

Life insurance (or life assurance, especially in the Commonwealth of Nations) is a contract between an insurance policy holder and an insurer or assurer, where the insurer promises to pay a designated beneficiary a sum of money upon the death ...

, cognition), financial variables (e.g., assets and income, housing, net worth, wills, consumption and savings), family characteristics (e.g., family structure, transfers, parent/child/grandchild/sibling information) and a host of other topics (e.g., expectations, expenses, internet use, risk taking, psychosocial, time use).

2002 and 2004 saw the introductions of the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) and the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), which includes respondents from 14 continental European countries plus Israel. These surveys were closely modeled after the HRS in the sample frame, design and content. A number of other countries (e.g., Japan, South Korea) also now field HRS-like surveys, and others (e.g., China, India) are currently fielding pilot studies. These data sets have expanded the ability of researchers to examine questions about retirement behavior by adding a cross-national perspective.

Notes: MHAS discontinued in 2003; ELSA numbers exclude institutionalized (nursing homes). Source: Borsch-Supan et al., eds. (November 2008). Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (2004–2007): Starting the Longitudinal Dimension.

Factors Affecting Retirement Decisions

Many factors affect people's retirement decisions. Retirement funding education is a big factor that affects the success of an individual's retirement experience. Social Security plays an important role because most individuals solely rely on Social Security as their only retirement option, when Social Security's trust funds are expected to be depleted by 2034. Knowledge affects an individual's retirement decisions by simply finding more reliable retirement options such as Individual Retirement Accounts or Employer-Sponsored Plans. In countries around the world, people are much more likely to retire at the early and normal retirement ages of the public pension system (e.g., ages 62 and 65 in the U.S.). This pattern cannot be explained by different financial incentives to retire at these ages since typically retirement benefits at these ages are approximately actuarially fair; that is, the present value of lifetime pension benefits (pension wealth) conditional on retiring at age ''a'' is approximately the same as pension wealth conditional on retiring one year later at age ''a''+1. Nevertheless, a large literature has found that individuals respond significantly to financial incentives relating to retirement (e.g., to discontinuities stemming from the Social Security earnings test or the tax system). Greater wealth tends to lead to earlier retirement since wealthier individuals can essentially "purchase" additional leisure. Generally, the effect of wealth on retirement is difficult to estimate empirically since observing greater wealth at older ages may be the result of increased saving over the working life in anticipation of earlier retirement. However, many economists have found creative ways to estimate wealth effects on retirement and typically find that they are small. For example, one paper exploits the receipt of an inheritance to measure the effect of wealth shocks on retirement using data from the HRS. The authors find that receiving an inheritance increases the probability of retiring earlier than expected by 4.4 percentage points, or 12 percent relative to the baseline retirement rate, over an eight-year period. A great deal of attention has surrounded how the Financial crisis of 2007–2008 and subsequent Great Recession are affecting retirement decisions, with the conventional wisdom saying that fewer people will retire since their savings have been depleted; however recent research suggests that the opposite may happen. Using data from the HRS, researchers examined trends in defined benefit (DB) vs. defined contribution (DC) pension plans and found that those nearing retirement had only limited exposure to the recent stock market decline and thus are not likely to substantially delay their retirement. At the same time, using data from the Current Population Survey (CPS), another study estimates that mass layoffs are likely to lead to an increase in retirement almost 50% larger than the decrease brought about by the stock market crash, so that on net retirements are likely to increase in response to the crisis. More information tells of how many who retire will continue to work, but not in the career they have had for the majority of their life. Job openings will increase in the next 5 years due to retirements of the baby boomer generation. The Over 50 population is actually the fastest growing labor groups in the US. A great deal of research has examined the effects of health status and health shocks on retirement. It is widely found that individuals in poor health generally retire earlier than those in better health. This does not necessarily imply that poor health status leads people to retire earlier, since in surveys retirees may be more likely to exaggerate their poor health status to justify their earlier decision to retire. This justification bias, however, is likely to be small. In general, declining health over time, as well as the onset of new health conditions, have been found to be positively related to earlier retirement. Health conditions that can cause someone to retire includehypertension

Hypertension (HTN or HT), also known as high blood pressure (HBP), is a long-term medical condition in which the blood pressure in the arteries is persistently elevated. High blood pressure usually does not cause symptoms. Long-term high bl ...

, diabetes mellitus, sleep apnea, joint diseases

An arthropathy is a disease of a joint. Types

Arthritis is a form of arthropathy that involves inflammation of one or more joints, while the term arthropathy may be used regardless of whether there is inflammation or not.

Joint diseases can be cla ...

, and hyperlipidemia.

Most people are married when they reach retirement age; thus, spouse's employment status may affect one's decision to retire. On average, husbands are three years older than their wives in the U.S., and spouses often coordinate their retirement decisions. Thus, men are more likely to retire if their wives are also retired than if they are still in the labor force, and vice versa.

EU member-states

Researchers analyzed factors affecting retirement decisions inEU Member States

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been des ...

:

* Alba-Ramirez (1997) uses micro data from the Active Population Survey of Spain

Active may refer to:

Music

* ''Active'' (album), a 1992 album by Casiopea

* Active Records, a record label

Ships

* ''Active'' (ship), several commercial ships by that name

* HMS ''Active'', the name of various ships of the British Royal ...

and logit model for analyzing determinants of retirement decision and finds that having more members in the household, and as well as children, has a negative effect on the probability of retirement among older males. This is an intuitive result as males in bigger household with children have to earn more and pension benefits will be less than needed for household.

* Antolin and Scarpetta (1998) using German Socio-Economic Panel

The ''German'' Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP [], for ''Sozio-oekonomisches Panel'') is a Longitudinal study, longitudinal panel dataset of the population in Germany. It is a household based study which started in 1984 and which reinterviews adul ...

and hazard model find that Socio-demographic factors such as health and gender have a strong impact on the retirement decision: women tend to retire earlier than men, and poor health makes people go into retirement, particularly in the case of disability retirement. The relationship between health status and retirement is significant for both self-assessed and objective indicators of health status.Antolín, P. and S. Scarpetta. 1998. "Microeconometric Analysis of the Retirement Decision: Germany”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 204, OECD Publishing This is similar finding to the previous research of Blau and Riphahn (1997); using individual data from the German Socio-Economic Panel as well, but controlling for different variables they found that if individual has chronic health condition, then he tends to retire. Antolin and Scarpetta (1998) use better measure for health status than Blau and Riphahn (1997), because self-assessed and objective indicators of health status are better measures than chronic health condition.

* Blöndal and Scarpetta (1999) find significant effect of socio-demographic factors on the retirement decision. Men tend to retire later than women as women try to benefit from special early retirement schemes in Germany and the Netherlands. Another reason is that they get access to pensions earlier than men as standard age of entitlement to pension is lower for women compared with men in Italy and the United Kingdom. The other interesting finding is that retirement depends on household size: heads of large households prefer not to retire. They think that this can be because of the significance of wages in large households compared with smaller ones and insufficiency of pension benefits. Another finding is that health status is significant factor in all early retirements; poor health conditions are especially significant if respondents join to disability benefit scheme. This result is true for both indicators used to express health status (self assessment and objective indicators). This research is similar to Antolin and Scarpetta (1998) and shows similar results extending sample and implications from Germany to OECD.

* Murray et al. (2016, 2019) have shown that in the United Kingdom local labour markets of where workers live effects later life work exit. In the first study, older workers aged 50 to 75 were more likely to exit the workforce over 10 years (years 2011-2011) if they had lived in a more deprived local authority in 2001. For respondents that identified as sick/disabled in 2011, effects of local area unemployment in 2001 were stronger for respondents who had better self-rated health in 2001. The second study used the 1946 Birth Cohort to show that it's not just area unemployment near retirement age that matters for the ages workers retire: higher area unemployment at age 26 was associated with poorer health and lower likelihood of employment at aged 53; and these two individual pathways were identified as the key mediators between area unemployment and retirement age.

* Rashad Mehbaliyev (2011) analyzed how different factors related with health, demographics, behavior, financial status, and macroeconomics can affect retirement status in European Union countries for data collected from the SHARE Wave 2 dataset ( Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe) and UN sources. He found that males are less likely to be retired compared with females in New Member States

The largest expansion of the European Union (EU), in terms of territory, number of states, and population took place on 1 May 2004.

The simultaneous accessions concerned the following countries (sometimes referred to as the "A10" countries): ...

, which is the opposite result than he found for Old Member States

Old or OLD may refer to:

Places

*Old, Baranya, Hungary

*Old, Northamptonshire, England

*Old Street station, a railway and tube station in London (station code OLD)

*OLD, IATA code for Old Town Municipal Airport and Seaplane Base, Old Town, Mai ...

. He explained that: "The reasons for these results can be the facts that significant gender wage gap exists in New Member States, household sizes are bigger in these countries than in Old Member States and males play important role in household income which make them retire less than females."

United States

* Quinn et al. (1998) find significant correlation between health status and retirement status. They transform answers for question about health status from five levels ("excellent", "very good", "good", "fair" and "poor") into three levels and report results for three groups of people. 85% of respondents who answered "excellent" or "very good" to the question about their health in 1992 were still working two years after this interview, compared to 82% of those who answered "good", and 70% of those answered "fair" or "poor". This fact is also true for year 1996: 73% of people from the first group were still on the job market, while this is 66% and 55% for other groups of people. However, Dhaval, Rashad and Spasojevic (2006) using data from six waves of Health and Retirement Survey (HRS) show that relationship between retirement and health status can imply the opposite effect in reality: physical and mental health decline after retirement. * Benitez-Silva (2000) analyzes determinants of labor force status and retirement process among elderly US citizens and possibility of decision returning to work using logit and probit models. He uses Health and Retirement Survey (HRS) for this purpose and finds that physical and mental health has significant effect on becoming employed. Male respondents are more likely to change their status from being not-employed to employed, but being insured has a negative effect on switching job status from “not-employed" to "employed" for people aged 60–62 and insignificant effect for 55–59 and aged over 63.Saving for Retirement

Overall, income after retirement can come from state pensions, occupational pensions, private savings and investments (private pension funds, owned housing), donations (e.g., by children), and social benefits. In some countries an additional lump sum is granted, according to the years of work and the average pay; this is usually provided by the employer. On a personal level, the rising cost of living during retirement is a serious concern to many older adults. Health care costs play an important role. Provision of state pensions is a significant drain on a government's budget. As life expectancy increases and the health of older people improves with medical advances, the age of entitlement to a pension has been increasing progressively since about 2010. Older people are more prone to sickness, and the cost of health care in retirement is large. Most countries provide universal health insurance coverage for seniors, although in the United States many people retire before they become eligible for Medicare health cover at 65 years of age.Calculators

A useful and straightforward calculation can be done if it is assumed that interest, after expenses, taxes, and inflation is zero. Assume that in real (after-inflation) terms, one's salary never changes over ''w'' years of working life. During ''p'' years of pension, one has a living standard that costs a replacement ratio ''R'' times as much as one's living standard in working life. The working life living standard is one's salary minus the proportion of salary Z that should be saved. Calculations are per unit salary (e.g., assume salary = 1). Then after ''w'' years work, retirement age accumulated savings = ''wZ''. To pay for pension for ''p'' years, necessary savings at retirement = ''Rp(1-Z)'' Equate these: ''wZ'' = ''Rp''(''1-Z'') and solve to give ''Z'' = ''Rp'' / (''w + Rp''). For example, if ''w'' = 35, ''p'' = 30 and ''R'' = 0.65, a proportion ''Z'' = 35.78% should be saved. Retirement calculators generally accumulate a proportion of salary up to retirement age. This shows a straightforward case, which nonetheless could be practically useful for optimistic people hoping to work for only as long as they are likely to be retired. For more complicated situations, there are several online retirement calculators on the Internet. Many retirement calculators project how much an investor needs to save, and for how long, to provide a certain level of retirement expenditures. Some retirement calculators, appropriate for safe investments, assume a constant, unvarying rate of return. Monte Carlo retirement calculators take volatility into account and project the probability that a particular plan of retirement savings, investments, and expenditures will outlast the retiree. Retirement calculators vary in the extent to which they take taxes, social security, pensions, and other sources of retirement income and expenditures into account. The assumptions keyed into a retirement calculator are critical. One of the most important assumptions is the assumed rate of real (after inflation) investment return. A conservative return estimate could be based on the real yield of Inflation-indexed bonds offered by some governments, including the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. The TIP$TER retirement calculator projects the retirement expenditures that a portfolio of inflation-linked bonds, coupled with other income sources like Social Security, would be able to sustain. Current real yields on United States Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS) are available at the US Treasury site. Current real yields on Canadian 'Real Return Bonds' are available at the Bank of Canada's site. As of December 2011, US Treasury inflation-linked bonds (TIPS) were yielding about 0.8% real per annum for the 30-year maturity and a noteworthy slightly negative real return for the 7-year maturity. Many individuals use "retirement calculators" on the Internet to determine the proportion of their pay they should be saving in a tax advantaged-plan (e.g., IRA or 401-K in the US, RRSP in Canada, personal pension in the UK, superannuation in Australia).

After expenses and any taxes, a reasonable (though arguably pessimistic) long-term assumption for a safe real rate of return is zero. So in real terms, interest does not help the savings grow. Each year of work must pay its share of a year of retirement. For someone planning to work for 40 years and be retired for 20 years, each year of work pays for itself and for half a year of retirement. Hence, 33.33% of pay must be saved, and 66.67% can be spent when earned. After 40 years of saving 33.33% of pay, we have accumulated assets of 13.33 years of pay, as in the graph. In the graph to the right, the lines are straight, which is appropriate given the assumption of a zero real investment return.

The graph above can be compared with those generated by many retirement calculators. However, most retirement calculators use nominal (not "real" dollars) and therefore require a projection of both the expected inflation rate and the expected nominal rate of return. One way to work around this limitation is to, for example, enter "0% return, 0% inflation" inputs into the calculator. The Bloomberg retirement calculator gives the flexibility to specify, for example, zero inflation and zero investment return and to reproduce the graph above. The MSN retirement calculator in 2011 has as the defaults a realistic 3% per annum inflation rate and optimistic 8% return assumptions; consistency with the December 2011 US nominal bond and inflation-protected bond market rates requires a change to about 3% inflation and 4% investment return before and after retirement.

Ignoring tax, someone wishing to work for a year and then relax for a year on the same living standard needs to save 50% of pay. Similarly, someone wishing to work from age 25 to 55 and be retired for 30 years till 85 needs to save 50% of pay if government and employment pensions are not a factor and if it is considered appropriate to assume a zero real investment return. The problem that the lifespan is not known in advance can be reduced in some countries by the purchase at retirement of an inflation-indexed

Many individuals use "retirement calculators" on the Internet to determine the proportion of their pay they should be saving in a tax advantaged-plan (e.g., IRA or 401-K in the US, RRSP in Canada, personal pension in the UK, superannuation in Australia).

After expenses and any taxes, a reasonable (though arguably pessimistic) long-term assumption for a safe real rate of return is zero. So in real terms, interest does not help the savings grow. Each year of work must pay its share of a year of retirement. For someone planning to work for 40 years and be retired for 20 years, each year of work pays for itself and for half a year of retirement. Hence, 33.33% of pay must be saved, and 66.67% can be spent when earned. After 40 years of saving 33.33% of pay, we have accumulated assets of 13.33 years of pay, as in the graph. In the graph to the right, the lines are straight, which is appropriate given the assumption of a zero real investment return.

The graph above can be compared with those generated by many retirement calculators. However, most retirement calculators use nominal (not "real" dollars) and therefore require a projection of both the expected inflation rate and the expected nominal rate of return. One way to work around this limitation is to, for example, enter "0% return, 0% inflation" inputs into the calculator. The Bloomberg retirement calculator gives the flexibility to specify, for example, zero inflation and zero investment return and to reproduce the graph above. The MSN retirement calculator in 2011 has as the defaults a realistic 3% per annum inflation rate and optimistic 8% return assumptions; consistency with the December 2011 US nominal bond and inflation-protected bond market rates requires a change to about 3% inflation and 4% investment return before and after retirement.

Ignoring tax, someone wishing to work for a year and then relax for a year on the same living standard needs to save 50% of pay. Similarly, someone wishing to work from age 25 to 55 and be retired for 30 years till 85 needs to save 50% of pay if government and employment pensions are not a factor and if it is considered appropriate to assume a zero real investment return. The problem that the lifespan is not known in advance can be reduced in some countries by the purchase at retirement of an inflation-indexed life annuity

A life annuity is an annuity, or series of payments at fixed intervals, paid while the purchaser (or annuitant) is alive. The majority of life annuities are insurance products sold or issued by life insurance companies however substantial case l ...

.

Size of Lump Sum Required

To pay for pension, assumed for simplicity to be received at the end of each year, and taking discounted values in the manner of a net present value calculation, the ideal lump sum available at retirement should be: :(1 – zprop ) R repl S = (1-zprop ) R repl S Above is the standard mathematical formula for the sum of a geometric series. (Or if ireal =0 then the series in braces sums to p since it then has p equal terms). As an example, assume that S=60,000 per year and that it is desired to replace Rrepl=0.80, or 80%, of pre-retirement living standard for p=30 years. Assume for current purposes that a proportion z prop=0.25 (25%) of pay was being saved. Using ireal=0.02, or 2% per year real return on investments, the necessary lump sum is given by the formula as (1-0.25)*0.80*60,000*annuity-series-sum(30)=36,000*22.396=806,272 in the nation's currency in 2008–2010 terms. To allow for inflation in a straightforward way, it is best to talk of the 806,272 as being '13.43 years of retirement age salary'. It may be appropriate to regard this as being the necessary lump sum to fund 36,000 of annual supplements to any employer or government pensions that are available. It is common to not include any house value in the calculation of this necessary lump sum, so for a homeowner the lump sum pays primarily for non-housing living costs.Size of Lump Sum Saved

At retirement, the following amount will have been accumulated: :zprop S : = zprop S ((1+i rel to pay)w- 1)/i rel to payEquate and Derive Necessary Saving Proportion

To make the accumulation match with the lump sum needed to pay pension: :zprop S (((1+i rel to pay )) w – 1)/i rel to pay = (1-zprop ) R repl S (1 – ((1+i real)) −p )/i real Bring zprop to the left hand side to give the answer, under this rough and unguaranteed method, for the proportion of pay that should be saved: :zprop = R repl (1 – ((1+i real )) −p )/i real / ((1+i rel to pay )) w – 1)/i rel to pay + R repl (1 – ((1+i real )) −p )/i real (Ret-03) Note that the special case i rel to pay =0 = i real means that the geometric series should be summed by noting that there are p or w identical terms and hence z prop = p/(w+p). This corresponds to the graph above with the straight line real-terms accumulation.Sample results

The result for the necessary zprop given by (Ret-03) depends critically on the assumptions made. As an example, one might assume that price inflation will be 3.5% per year forever and that one's pay will increase only at that same rate of 3.5%. If a 4.5% per year nominal rate of interest is assumed, then (using 1.045/1.035 in real terms) pre-retirement and post-retirement net interest rates will remain the same, irel to pay = 0.966 percent per year and ireal = 0.966 percent per year. These assumptions may be reasonable in view of the market returns available on inflation-indexed bonds, after expenses and any tax. Equation (Ret-03) is readily coded in Excel and with these assumptions gives the required savings rates in the accompanying picture.Monte Carlo: Better Allowance for Randomness

Finally, a newer method for determining the adequacy of a retirement plan isMonte Carlo simulation

Monte Carlo methods, or Monte Carlo experiments, are a broad class of computational algorithms that rely on repeated random sampling to obtain numerical results. The underlying concept is to use randomness to solve problems that might be determini ...

. This method has been gaining popularity and is now employed by many financial planners. Monte Carlo retirement calculators allow users to enter savings, income and expense information and run simulations of retirement scenarios. The simulation results show the probability that the retirement plan will be successful.

Early Retirement

Retirement is generally considered to be "early" if it occurs before the age (or tenure) needed for eligibility for support and funds from government or employer-provided sources. Early retirees typically rely on their own savings and investments to be self-supporting, either indefinitely or until they begin receiving external support. Early retirement can also be used as a euphemistic term for being terminated from employment before typical retirement age.Savings needed

While conventional wisdom has it that one can retire and take 7% or more out of a portfolio year after year, this strategy would not have worked very often in the past. The chart at the right shows the year-to-year portfolio balances after taking $35,000 (and adjusting for inflation) from a $750,000 portfolio every year for 30 years, starting in 1973 (red line), 1974 (blue line), or 1975 (green line). While the overall market conditions and inflation affected all three about the same (since all three experienced exactly the same conditions between 1975 and 2003), the chance of making the funds last for 30 years depended heavily on what happened to the

The chart at the right shows the year-to-year portfolio balances after taking $35,000 (and adjusting for inflation) from a $750,000 portfolio every year for 30 years, starting in 1973 (red line), 1974 (blue line), or 1975 (green line). While the overall market conditions and inflation affected all three about the same (since all three experienced exactly the same conditions between 1975 and 2003), the chance of making the funds last for 30 years depended heavily on what happened to the stock market

A stock market, equity market, or share market is the aggregation of buyers and sellers of stocks (also called shares), which represent ownership claims on businesses; these may include ''securities'' listed on a public stock exchange, as ...

in the first few years.

Those contemplating early retirement will want to know if they have enough to survive possible bear markets such as the one that would cause the hypothetical 1973 retiree's fund to be exhausted after only 20 years.

The history of the US stock market

A stock market, equity market, or share market is the aggregation of buyers and sellers of stocks (also called shares), which represent ownership claims on businesses; these may include ''securities'' listed on a public stock exchange, as ...

shows that one would need to live on about 4% of the initial portfolio per year to ensure that the portfolio is not depleted before the end of the retirement; this rule of thumb is a summary of one conclusion of the Trinity study, though the report is more nuanced and the conclusions and very approach have been heavily criticized (see Trinity study for details). This allows for increasing the withdrawals with inflation to maintain a consistent spending ability throughout the retirement, and to continue making withdrawals even in dramatic and prolonged bear markets. (The 4% figure does not assume any pension or change in spending levels throughout the retirement.)

When retiring prior to age , there is a 10% IRS penalty on withdrawals from a retirement plan such as a 401(k) plan or a Traditional IRA. Exceptions apply under certain circumstances. At age 59 and six months, the penalty-free status is achieved and the 10% IRS penalty no longer applies.

To avoid the 10% penalty prior to age , a person should consult a lawyer about the use of IRS rule 72 T. This rule must be applied for with the IRS. It allows the distribution of an IRA account prior to age in equal amounts of a period of either 5 years or until the age of , whichever is the longest time period, without a 10% penalty. Taxes still must be paid on the distributions.

Calculations using actual numbers

Although the 4% initial portfolio withdrawal rate described above can be used as a rough gauge, it is often desirable to use a retirement planning tool that accepts detailed input and can render a result that has more precision. Some of these tools model only the retirement phase of the plan while others can model both the savings or accumulation phase as well as the retirement phase of the plan. For example, an analysis by '' Forbes'' reckoned that in 90% of historical markets, a 4% rate would have lasted for at least 30 years, while in 50% of the historical markets, a 4% rate would have been sustained for more than 40 years. The effects of making inflation-adjusted withdrawals from a given starting portfolio can be modeled with a downloadable spreadsheet that uses historical stock market data to estimate likely portfolio returns. Another approach is to employ a retirement calculator that also uses historical stock market modeling, but adds provisions for incorporating pensions, other retirement income, and changes in spending that may occur during the course of the retirement.Life after Retirement

Retirement might coincide with important life changes; a retired worker might move to a new location, for example a retirement community, thereby having less frequent contact with their previous social context and adopting a new lifestyle. Often retirees volunteer for charities and other community organizations. Tourism is a common marker of retirement and for some becomes a way of life, such as for so-called grey nomads. Some retired people even choose to go and live in warmer climates in what is known as retirement migration. It has been found that Americans have six lifestyle choices as they age: continuing to work full-time, continuing to work part-time, retiring from work and becoming engaged in a variety of leisure activities, retiring from work and becoming involved in a variety of recreational and leisure activities, retiring from work and later returning to work part-time, and retiring from work and later returning to work full-time.Cox, H. (2012). Work/retirement choices and lifestyle patterns of older Americans. In L. Loeppke (Ed.), Annual editions: Aging (24th ed., pp. 74–83). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill An important note to make from these lifestyle definitions are that four of the six involve working. America is facing an important demographic change in that the Baby Boomer generation is now reaching retirement age. This poses two challenges: whether there will be a sufficient number of skilled workers in the work force, and whether the current pension programs will be sufficient to support the growing number of retired people. The reasons that some people choose to never retire, or to return to work after retiring include not only the difficulty of planning for retirement but also wages and fringe benefits, expenditure of physical and mental energy, production of goods and services, social interaction, and social status may interact to influence an individual's work force participation decision. Often retirees are called upon to care forgrandchildren

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Ideall ...

and occasionally aged parents. For many it gives them more time to devote to a hobby or sport such as golf or sailing. On the other hand, many retirees feel restless and suffer from depression as a result of their new situation. The newly retired are one of the most vulnerable social groups to become depressed most likely due to retirement coinciding with a deteriorating health status and increased care-giving responsibilities. Retirement coincides with deterioration of one's health that correlates with increasing age and this likely plays a major role in increased rates of depression in retirees. Longitudinal and cross-sectional studies have shown that healthy elderly and retired people are as happy or happier and have an equal quality of life as they age as compared to younger employed adults, therefore retirement in and of itself is not likely to contribute to development of depression. Research around what retirees would ideally like to have a fulfilling life after retiring, found the most important factors were "physical comfort, social integration, contribution, security, autonomy and enjoyment".

Many people in the later years of their lives, due to failing health, require assistance, sometimes in extremely expensive treatments – in some countries – being provided in a nursing home. Those who need care, but are not in need of constant assistance, may choose to live in a retirement home.

See also

*Simple living

Simple living refers to practices that promote simplicity in one's lifestyle. Common practices of simple living include reducing the number of possessions one owns, depending less on technology and services, and spending less money. Not only is ...

* Downshifting (lifestyle)

* Pension

A pension (, from Latin ''pensiō'', "payment") is a fund into which a sum of money is added during an employee's employment years and from which payments are drawn to support the person's retirement from work in the form of periodic payments ...

* Ageing

Ageing ( BE) or aging ( AE) is the process of becoming older. The term refers mainly to humans, many other animals, and fungi, whereas for example, bacteria, perennial plants and some simple animals are potentially biologically immortal. In ...

* Mandatory retirement

* Gerontology

Gerontology ( ) is the study of the social, cultural, psychological, cognitive, and biological aspects of aging. The word was coined by Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov in 1903, from the Greek , ''geron'', "old man" and , ''-logia'', "study of". The fie ...

* Social security

* Parental dividend

* Retirement spend down

At retirement, individuals stop working and no longer get employment earnings, and enter a phase of their lives, where they rely on the assets they have accumulated, to supply money for their spending needs for the rest of their lives. Retirement ...

* Asset/liability modeling Asset/liability modeling is the process used to manage the business and financial objectives of a financial institution or an individual through an assessment of the portfolio assets and liabilities in an integrated manner. The process is characte ...

* Issues in retirement security

Issues in retirement security refers to growing economic concerns and societal issues over the ability of individual workers and other individuals in society to have an economically secure retirement.

Main issues appear to arise from the general i ...

References

Further reading

* Schultz, Ellen E.''RETIREMENT HEIST: How Companies Plunder and Profit from the Nest Eggs of American Workers"

Penguin Publishing, 2011 * *

External links

"Historical Development"

Social Security Administration * Short, Joanna

"Economic History of Retirement in the U.S."

2010-02-01,

Augustana College Augustana College may refer to:

*Augustana College (Illinois)

*Augustana University Sioux Falls, South Dakota

*Augustana University College, Alberta

See also

*Augustana Divinity School (Neuendettelsau)

The Augustana-Hochschule Neuendettelsau is ...

, Rock Island, Illinois

{{Authority control

Termination of employment