''www.unhcr.org'', accessed 22 June 2021 Such a person may be called an asylum seeker until granted refugee status by the contracting state or the

Etymology and usage

Similar terms in other languages have described an event marking migration of a specific population from a place of origin, such as theDefinitions

The first modern definition of international refugee status came about under the

The first modern definition of international refugee status came about under the owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.In 1967, the definition was basically confirmed by the UN Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees. The Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa expanded the 1951 definition, which the Organization of African Unity adopted in 1969:

Every person who, owing to external aggression, occupation, foreign domination or events seriously disturbing public order in either part or the whole of his country of origin or nationality, is compelled to leave his place of habitual residence in order to seek refuge in another place outside his country of origin or nationality.The 1984 regional, non-binding Latin-American

persons who have fled their country because their lives, safety or freedom have been threatened by generalized violence, foreign aggression, internal conflicts, massive violation of human rights or other circumstances which have seriously disturbed public order., the UNHCR itself, in addition to the 1951 definition, recognizes persons as refugees:

who are outside their country of nationality or habitual residence and unable to return there owing to serious and indiscriminate threats to life, physical integrity or freedom resulting from generalized violence or events seriously disturbing public order.European Union's minimum standards definition of refugee, underlined by Art. 2 (c) of Directive No. 2004/83/EC, essentially reproduces the narrow definition of refugee offered by the UN 1951 Convention; nevertheless, by virtue of articles 2 (e) and 15 of the same Directive, persons who have fled a war-caused generalized violence are, at certain conditions, eligible for a complementary form of protection, called

Related terms

Refugee resettlement is defined as "an organized process of selection, transfer and arrival of individuals to another country. This definition is restrictive, as it does not account for the increasing prevalence of unmanaged migration processes." The term refugee relocation refers to "a non‐organized process of individual transfer to another country." Refugee settlement refers to "the process of basic adjustment to life ‒ often in the early stages of transition to the new country ‒ including securing access to housing, education, healthcare, documentation and legal rights ndemployment is sometimes included in this process, but the focus is generally on short‐term survival needs rather than long‐term career planning." Refugee integration means "a dynamic, long‐term process in which a newcomer becomes a full and equal participant in the receiving society... Compared to the general construct of settlement, refugee integration has a greater focus on social, cultural and structural dimensions. This process includes the acquisition of legal rights, mastering the language and culture, reaching safety and stability, developing social connections and establishing the means and markers of integration, such as employment, housing and health." Refugee workforce integration is understood to be "a process in which refugees engage in economic activities (employment or self‐employment) which are commensurate with individuals' professional goals and previous qualifications and experience, and provide adequate economic security and prospects for career advancement."History

The idea that a person who sought sanctuary in a holy place could not be harmed without inviting divine retribution was familiar to the

The idea that a person who sought sanctuary in a holy place could not be harmed without inviting divine retribution was familiar to the

The term "refugee" sometimes applies to people who might fit the definition outlined by the 1951 Convention, were it applied retroactively. There are many candidates. For example, after the

The term "refugee" sometimes applies to people who might fit the definition outlined by the 1951 Convention, were it applied retroactively. There are many candidates. For example, after the League of Nations

The first international co-ordination of refugee affairs came with the creation by the

The first international co-ordination of refugee affairs came with the creation by the 1933 (rise of Nazism) to 1944

The rise of

The rise of

On 31 December 1938, both the Nansen Office and High Commission were dissolved and replaced by the Office of the High Commissioner for Refugees under the Protection of the League. This coincided with the flight of several hundred thousand Spanish Republicans to France after their defeat by the Nationalists in 1939 in the

On 31 December 1938, both the Nansen Office and High Commission were dissolved and replaced by the Office of the High Commissioner for Refugees under the Protection of the League. This coincided with the flight of several hundred thousand Spanish Republicans to France after their defeat by the Nationalists in 1939 in the Post-World War II population transfers

After the Soviet armed forces captured eastern Poland from the Germans in 1944, the Soviets unilaterally declared a new frontier between the Soviet Union and Poland approximately at theAgreements of the Berlin (Potsdam) Conference

placing one fourth of Germany's territory under the Provisional Polish administration. Article XII ordered that the remaining German populations in Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary be transferred west in an "orderly and humane" manner

Agreements of the Berlin (Potsdam) Conference

(See

Although not approved by Allies at Potsdam, hundreds of thousands of ethnic Germans living in Yugoslavia and Romania were deported to slave labour in the Soviet Union, to

Although not approved by Allies at Potsdam, hundreds of thousands of ethnic Germans living in Yugoslavia and Romania were deported to slave labour in the Soviet Union, to  At the end of World War II, there were more than 5 million "displaced persons" from the Soviet Union in Western Europe. About 3 million had been Forced labor in Germany during World War II, forced laborers (Ostarbeiters) in Germany and occupied territories. The Soviet POWs and the Andrey Vlasov, Vlasov men were put under the jurisdiction of SMERSH (Death to Spies). Of the 5.7 million Nazi crimes against Soviet POWs, Soviet prisoners of war captured by the Germans, 3.5 million had died while in German captivity by the end of the war. The survivors on their return to the USSR were treated as traitors (see Order No. 270). Over 1.5 million surviving Red Army soldiers imprisoned by the Nazis were sent to the Gulag.

Poland and Soviet Ukraine conducted population exchanges following the imposition of a new Poland-Soviet border at the

At the end of World War II, there were more than 5 million "displaced persons" from the Soviet Union in Western Europe. About 3 million had been Forced labor in Germany during World War II, forced laborers (Ostarbeiters) in Germany and occupied territories. The Soviet POWs and the Andrey Vlasov, Vlasov men were put under the jurisdiction of SMERSH (Death to Spies). Of the 5.7 million Nazi crimes against Soviet POWs, Soviet prisoners of war captured by the Germans, 3.5 million had died while in German captivity by the end of the war. The survivors on their return to the USSR were treated as traitors (see Order No. 270). Over 1.5 million surviving Red Army soldiers imprisoned by the Nazis were sent to the Gulag.

Poland and Soviet Ukraine conducted population exchanges following the imposition of a new Poland-Soviet border at the Refugee studies

With the occurrence of major instances of diaspora and forced migration, the study of their causes and implications has emerged as a legitimate interdisciplinary area of research, and began to rise by mid to late 20th century, afterUN Refugee Agencies

UNHCR

Headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland, the Office of theUNRWA

Unlike other refugee groups, the UN created a specific entity called the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) in the aftermath of the Al-Nakba in 1948, which led to a serious refugee crisis in the Arab region responsible for the displacement of 700,000 Palestinian refugees. This number has gone up to at least 5 million refugees in the last 70 years. The United Nations defines Palestinian refugees as “persons whose normal place of residence was Palestine during the period 1 June 1946 to 15 May 1948, and who lost both home and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 conflict.” Descendants of this generation also fall under the status of Palestinian refugee. Another refugee wave started in 1967 after the Six-day-War, where mostly Palestinians living in Gaza and the West Bank were victims of displacement. According to the United Nations, Palestinian refugees struggle with access to health care, food, clean water, sanitation, environmental health and infrastructure, education, and technology. According to the report, food, shelter, and environmental health are a human's basic needs. United Nations agency UNRWA (The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East) focuses on addressing these issues to relieve Palestinians from any harm. UNWRA was established as a temporary agency that would carry out a humanitarian response mandate for Palestinian refugees in Gaza, the West Bank, Syria, Jordan and Lebanon. The responsibilities for the assistance for protection for Palestinian refugees and human development were originally left to the United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine (UNCCP). This agency failed to function, which led the agency to stop working. UNRWA took over these responsibilities and expanded their mandate from just humanitarian emergency relief to including human development and protection of the Palestinian society. Communication with host countries where UNRWA is operating (Syria, Jordan and Lebanon) is very important as the agency's mandate changes per region. UNRWA's Medium Term Strategy is a report that lists all the issues that the Palestinians are facing and UNRWA's plan to mitigate the severeness of the issues. The report shows that UNRWA focusses mostly on food assistance, health care, education and shelter for Palestinian refugees. UNRWA has succeeded in placing over 700 schools with over 500,000 students, 140 health centers, 113 women community centers, and has awarded over 475,000 loans. UNRWA's funding relies mostly on voluntary donations. Fluctuations in these donations result in constraints in carrying out the mandate.Acute and temporary protection

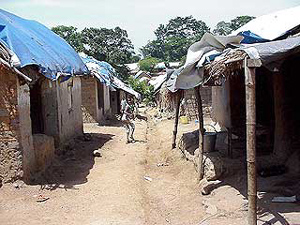

Refugee camp

A refugee camp is a place built by governments or Non-governmental organization, NGOs (such as the International Committee of the Red Cross, Red Cross) to receive refugees, internally displaced persons or sometimes also other migrants. It is usually designed to offer acute and temporary accommodation and services and any more permanent facilities and structures often banned. People may stay in these camps for many years, receiving emergency food, education and medical aid until it is safe enough to return to their country of origin. There, refugees are at risk of disease, child soldier and terrorist recruitment, and physical and sexual violence. There are estimated to be 700 refugee camp locations worldwide.

A refugee camp is a place built by governments or Non-governmental organization, NGOs (such as the International Committee of the Red Cross, Red Cross) to receive refugees, internally displaced persons or sometimes also other migrants. It is usually designed to offer acute and temporary accommodation and services and any more permanent facilities and structures often banned. People may stay in these camps for many years, receiving emergency food, education and medical aid until it is safe enough to return to their country of origin. There, refugees are at risk of disease, child soldier and terrorist recruitment, and physical and sexual violence. There are estimated to be 700 refugee camp locations worldwide.

Urban refugee

Not all refugees who are supported by the UNHCR live in refugee camps. A significant number, actually more than half, live in urban settings, such as the ~60,000 Iraqi refugees in Damascus (Syria), and the ~30,000 Sudanese refugees in Cairo (Egypt).Durable solutions

The residency status in the host country whilst under temporary UNHCR protection is very uncertain as refugees are only granted temporary visas that have to be regularly renewed. Rather than only safeguarding the rights and basic well-being of refugees in the camps or in urban settings on a temporary basis the UNHCR's ultimate goal is to find one of the three durable solutions for refugees: integration, repatriation, resettlement.Integration and naturalisation

Local integration is aiming at providing the refugee with the permanent right to stay in the country of asylum, including, in some situations, as a naturalized citizen. It follows the formal granting of refugee status by the country of asylum. It is difficult to quantify the number of refugees who settled and integrated in their first country of asylum and only the number of naturalisations can give an indication. In 2014 Tanzania granted citizenship to 162,000 refugees from Burundi and in 1982 to 32,000 Rwandan refugees. Mexico naturalised 6,200 Guatemalan refugees in 2001.Voluntary return

Voluntary return of refugees into their country of origin, in safety and dignity, is based on their free will and their informed decision. In the last couple of years parts of or even whole refugee populations were able to return to their home countries: e.g. 120,000 Congolese refugees returned from the Republic of Congo to the DRC, 30,000 Angolans returned home from the DRC and Botswana, Ivorian refugees returned from Liberia, Afghans from Pakistan, and Iraqis from Syria. In 2013, the governments of Kenya and Somalia also signed a tripartite agreement facilitating the repatriation of refugees from Somalia. The UNHCR and the IOM offer assistance to refugees who want to return voluntarily to their home countries. Many developed countries also have Assisted Voluntary Return (AVR) programmes for asylum seekers who want to go back or were Asylum seeker#Refusal of asylum, refused asylum.Third country resettlement

Third country resettlement involves the assisted transfer of refugees from the country in which they have sought asylum to a safe third country that has agreed to admit them as refugees. This can be for permanent settlement or limited to a certain number of years. It is the third durable solution and it can only be considered once the two other solutions have proved impossible. The UNHCR has traditionally seen resettlement as the least preferable of the "durable solutions" to refugee situations. However, in April 2000 the then UN High Commissioner for Refugees, Sadako Ogata, stated "Resettlement can no longer be seen as the least-preferred durable solution; in many cases it is the ''only'' solution for refugees."Internally displaced person

UNHCR's mandate has gradually been expanded to include protecting and providing humanitarian assistance to internally displaced persons (IDPs) and people in IDP-like situations. These are civilians who have been forced to flee their homes, but who have not reached a neighboring country. IDPs do not fit the legal definition of a refugee under the 1951 Refugee Convention, Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, 1967 Protocol and the OAU Convention, 1969 Organization for African Unity Convention, because they have not left their country. As the nature of war has changed in the last few decades, with more and more internal conflicts replacing interstate wars, the number of IDPs has increased significantly.Refugee status

In the United States, the term refugee is defined under the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, Immigration of Nationality Act (INA). In other countries, it is often used in different contexts: in everyday usage it refers to a forcibly displaced person who has fled his or her country of origin; in a more specific context it refers to such a person who was, on top of that, granted refugee status in the country the person fled to. Even more exclusive is the Convention refugee status which is given only to persons who fall within the #Legal definitions, refugee definition of the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol. To receive refugee status, a person must have applied for asylum, making them—while waiting for a decision—an asylum seeker. However, a displaced person otherwise legally entitled to refugee status may never apply for asylum, or may not be allowed to apply in the country they fled to and thus may not have official asylum seeker status. Once a displaced person is granted refugee status they enjoy certain Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees#Rights and responsibilities of parties to the Refugee Convention, rights as agreed in the 1951 Refugee convention. Not all countries have signed and ratified this convention and some countries do not have a legal procedure for dealing with asylum seekers.Seeking asylum

An asylum seeker is a displaced person or immigrant who has formally sought the protection of the state they fled to as well as the right to remain in this country and who is waiting for a decision on this formal application. An asylum seeker may have applied for Convention refugee status or for Asylum seeker#Complementary forms of protection, complementary forms of protection. Asylum is thus a category that includes different forms of protection. Which form of protection is offered depends on the #Legal definition, legal definition that best describes the asylum seeker's reasons to flee. Once the decision was made the asylum seeker receives either Convention refugee status or a complementary form of protection, and can stay in the country—or is refused asylum, and then often has to leave. Only after the state, territory or the UNHCR—wherever the application was made—recognises the protection needs does the asylum seeker ''officially'' receive refugee status. This carries certain rights and obligations, according to the legislation of the receiving country.

Quota refugees do not need to apply for asylum on arrival in the third countries as they already went through the UNHCR refugee status determination process whilst being in the first country of asylum and this is usually accepted by the third countries.

An asylum seeker is a displaced person or immigrant who has formally sought the protection of the state they fled to as well as the right to remain in this country and who is waiting for a decision on this formal application. An asylum seeker may have applied for Convention refugee status or for Asylum seeker#Complementary forms of protection, complementary forms of protection. Asylum is thus a category that includes different forms of protection. Which form of protection is offered depends on the #Legal definition, legal definition that best describes the asylum seeker's reasons to flee. Once the decision was made the asylum seeker receives either Convention refugee status or a complementary form of protection, and can stay in the country—or is refused asylum, and then often has to leave. Only after the state, territory or the UNHCR—wherever the application was made—recognises the protection needs does the asylum seeker ''officially'' receive refugee status. This carries certain rights and obligations, according to the legislation of the receiving country.

Quota refugees do not need to apply for asylum on arrival in the third countries as they already went through the UNHCR refugee status determination process whilst being in the first country of asylum and this is usually accepted by the third countries.

Refugee status determination

To receive refugee status, a displaced person must go through a Refugee Status Determination (RSD) process, which is conducted by the government of the country of asylum or the UNHCR, and is based on Refugee law, international, regional or national law. RSD can be done on a case-by-case basis as well as for whole groups of people. Which of the Asylum seeker#Status determination processes, two processes is used often depends on the size of the influx of displaced persons. There is no specific method mandated for RSD (apart from the commitment to the 1951 Refugee Convention) and it is subject to the overall efficacy of the country's internal administrative and judicial system as well as the characteristics of the refugee flow to which the country responds. This lack of a procedural direction could create a situation where political and strategic interests override humanitarian considerations in the RSD process. There are also no fixed interpretations of the elements in the 1951 Refugee Convention and countries may interpret them differently (see also refugee roulette).

However, in 2013, the UNHCR conducted them in more than 50 countries and co-conducted them parallel to or jointly with governments in another 20 countries, which made it the second largest RSD body in the world The UNHCR follows a set of guidelines described in the ''Handbook and Guidelines on Procedures and Criteria for Determining Refugee Status'' to determine which individuals are eligible for refugee status.

There is no specific method mandated for RSD (apart from the commitment to the 1951 Refugee Convention) and it is subject to the overall efficacy of the country's internal administrative and judicial system as well as the characteristics of the refugee flow to which the country responds. This lack of a procedural direction could create a situation where political and strategic interests override humanitarian considerations in the RSD process. There are also no fixed interpretations of the elements in the 1951 Refugee Convention and countries may interpret them differently (see also refugee roulette).

However, in 2013, the UNHCR conducted them in more than 50 countries and co-conducted them parallel to or jointly with governments in another 20 countries, which made it the second largest RSD body in the world The UNHCR follows a set of guidelines described in the ''Handbook and Guidelines on Procedures and Criteria for Determining Refugee Status'' to determine which individuals are eligible for refugee status.

Refugee rights

Refugee rights encompass both customary law, peremptory norms, and international legal instruments. If the entity granting refugee status is a state that has signed the 1951 Refugee Convention then the refugee has the Refugee employment, right to employment. Further rights include the following rights and obligations for refugees:Right of return

Even in a supposedly "post-conflict" environment, it is not a simple process for refugees to return home.Sara Pantuliano (2009

Even in a supposedly "post-conflict" environment, it is not a simple process for refugees to return home.Sara Pantuliano (2009Uncharted Territory: Land, Conflict and Humanitarian Action

Overseas Development Institute The UN Pinheiro Principles are guided by the idea that people not only have the right to return home, but also the right to the same property. It seeks to return to the pre-conflict status quo and ensure that no one profits from violence. Yet this is a very complex issue and every situation is different; conflict is a highly transformative force and the pre-war status-quo can never be reestablished completely, even if that were desirable (it may have caused the conflict in the first place). Therefore, the following are of particular importance to the right to return: * May never have had property (e.g., in Afghanistan) * Cannot access what property they have (Colombia, Guatemala, South Africa and Sudan) * Ownership is unclear as families have expanded or split and division of the land becomes an issue * Death of owner may leave dependents without clear claim to the land * People settled on the land know it is not theirs but have nowhere else to go (as in Colombia, Rwanda and Timor-Leste) * Have competing claims with others, including the state and its foreign or local business partners (as in Aceh, Angola, Colombia, Liberia and Sudan). Refugees who were third country resettlement, resettled to a third country will likely lose the indefinite leave to remain in this country if they return to their country of origin or the country of first asylum.

Right to non-refoulement

Non-refoulement is the right not to be returned to a place of persecution and is the foundation for international refugee law, as outlined in the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. The right to non-refoulement is distinct from the right to asylum. To respect the right to asylum, states must not deport genuine refugees. In contrast, the right to non-refoulement allows states to transfer genuine refugees to third party countries with respectable human rights records. The portable procedural model, proposed by political philosopher Andy Lamey, emphasizes the right to non-refoulement by guaranteeing refugees three procedural rights (to a verbal hearing, to legal counsel, and to judicial review of detention decisions) and ensuring those rights in the constitution. This proposal attempts to strike a balance between the interest of national governments and the interests of refugees.Right to family reunification

Family reunification (which can also be a form of resettlement) is a recognized reason for immigration in many countries. Divided family, Divided families have the right to be reunited if a family member with permanent right of residency applies for the reunification and can prove the people on the application were a family unit before arrival and wish to live as a family unit since separation. If application is successful this enables the rest of the family to immigrate to that country as well.Right to travel

Those states that signed the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees are obliged to issue travel documents (i.e. "Convention Travel Document") to refugees lawfully residing in their territory. It is a valid travel document in place of a passport, however, it cannot be used to travel to the country of origin, i.e. from where the refugee fled.Restriction of onward movement

Once refugees or asylum seekers have found a safe place and protection of a state or territory outside their territory of origin they are discouraged from leaving again and seeking protection in another country. If they do move onward into a second country of asylum this movement is also called ''"irregular movement"'' by the UNHCR (see also asylum shopping). UNHCR support in the second country may be less than in the first country and they can even be returned to the first country.World Refugee Day

World Refugee Day has occurred annually on 20 June since 2000 by a special United Nations General Assembly Resolution. 20 June had previously been commemorated as "African Refugee Day" in a number of African countries.

In the United Kingdom World Refugee Day is celebrated as part of Refugee Week. Refugee Week is a nationwide festival designed to promote understanding and to celebrate the cultural contributions of refugees, and features many events such as music, dance and theatre.

In the Roman Catholic Church, the World Day of Migrants and Refugees is celebrated in January each year, since instituted in 1914 by Pope Pius X.

World Refugee Day has occurred annually on 20 June since 2000 by a special United Nations General Assembly Resolution. 20 June had previously been commemorated as "African Refugee Day" in a number of African countries.

In the United Kingdom World Refugee Day is celebrated as part of Refugee Week. Refugee Week is a nationwide festival designed to promote understanding and to celebrate the cultural contributions of refugees, and features many events such as music, dance and theatre.

In the Roman Catholic Church, the World Day of Migrants and Refugees is celebrated in January each year, since instituted in 1914 by Pope Pius X.

Issues

Protracted displacement

Displacement is a long lasting reality for most refugees. Two-thirds of all refugees around the world have been displaced for over three years, which is known as being in 'protracted displacement'. 50% of refugees—around 10 million people—have been displaced for over ten years. Protracted displacement can lead to detrimental effects on refugee employment and refugee workforce integration, exacerbating the effect of the canvas ceiling. Protracted displacement leads to skills to atrophy, leading qualifications and experiences to be outdated and incompatible to the changing working environments of receiving countries by the time refugees resettle. The Overseas Development Institute has found that aid programmes need to move from short-term models of assistance (such as food or cash handouts) to more sustainable long-term programmes that help refugees become more self-reliant. This can involve tackling difficult legal and economic environments, by improving social services, job opportunities and laws.Medical problems

Refugees typically report poorer levels of health, compared to other immigrants and the non-immigrant population.PTSD

Apart from physical wounds or starvation, a large percentage of refugees develop symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and show post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) or Clinical depression, depression. These long-term mental problems can severely impede the functionality of the person in everyday situations; it makes matters even worse for displaced persons who are confronted with a new environment and challenging situations. They are also at high risk for suicide. Among other symptoms, post-traumatic stress disorder involves anxiety (mood), anxiety, over-alertness, sleeplessness, chronic fatigue syndrome, motor difficulties, failing short term memory, amnesia, nightmares and sleep-paralysis. Flashbacks are characteristic to the disorder: the patient experiences the traumatic event (psychological), traumatic event, or pieces of it, again and again. Depression is also characteristic for PTSD-patients and may also occur without accompanying PTSD. PTSD was diagnosed in 34.1% of Palestinian people, Palestinian children, most of whom were refugees, males, and working. The participants were 1,000 children aged 12 to 16 years from governmental, private, and United Nations Relief Work Agency UNRWA schools in East Jerusalem and various governorates in the West Bank. Another study showed that 28.3% of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bosnian refugee women had symptoms of PTSD three or four years after their arrival in Sweden. These women also had significantly higher risks of symptoms of depression, anxiety, and psychological distress than Swedish-born women. For depression the odds ratio was 9.50 among Bosnian women. A study by the Department of Pediatrics and Emergency Medicine at the Boston University School of Medicine demonstrated that twenty percent of Sudanese refugee minors living in the United States had a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder. They were also more likely to have worse scores on all the Child Health Questionnaire subscales. In a study for the United Kingdom, refugees were found to be 4 percentage points more likely to report a mental health problem compared to the non-immigrant population. This contrasts with the results for other immigrant groups, which were less likely to report a mental health problem compared to the non-immigrant population. Many more studies illustrate the problem. One meta-study was conducted by the psychiatry department of Oxford University at Warneford Hospital in the United Kingdom. Twenty Statistical survey, surveys were analyzed, providing results for 6,743 adult refugees from seven countries. In the larger studies, 9% were diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder and 5% with major depression, with evidence of much psychiatric co-morbidity. Five surveys of 260 refugee children from three countries yielded a prevalence of 11% for post-traumatic stress disorder. According to this study, refugees resettled in Western countries could be about ten times more likely to have PTSD than age-matched general populations in those countries. Worldwide, tens of thousands of refugees and former refugees resettled in Western countries probably have post-traumatic stress disorder.Malaria

Refugees are often more susceptible to illness for several reasons, including a lack of immunity to local strains of malaria and other diseases. Displacement of a people can create favorable conditions for disease transmission. Refugee camps are typically heavily populated with poor sanitary conditions. The removal of vegetation for space, building materials or firewood also deprives mosquitoes of their natural habitats, leading them to more closely interact with humans. In the 1970s, Afghanese refugees that were relocated to Pakistan were going from a country with an effective malaria control strategy, to a country with a less effective system. The refugee camps were built near rivers or irrigation sites had higher malaria prevalence than refugee camps built on dry lands. The location of the camps lent themselves to better breeding grounds for mosquitoes, and thus a higher likelihood of malaria transmission. Children aged 1–15 were the most susceptible to malaria infection, which is a significant cause of mortality in children younger than 5. Malaria was the cause of 16% of the deaths in refugee children younger than 5 years of age. Malaria is one of the most commonly reported causes of death in refugees and displaced persons. Since 2014, reports of malaria cases in Germany had doubled compared to previous years, with the majority of cases found in refugees from Eritrea. The World Health Organization recommends that all people in areas that are endemic for malaria use long-lasting insecticide nets. A cohort study found that within refugee camps in Pakistan, insecticide treated bed nets were very useful in reducing malaria cases. A single treatment of the nets with the insecticide permethrin remained protective throughout the 6 month transmission season.Access to healthcare services

Access to services depends on many factors, including whether a refugee has received official status, is situated within a refugee camp, or is in the process of third country resettlement. The UNHCR recommends integrating access to primary care and emergency health services with the host country in as equitable a manner as possible. Prioritized services include areas of maternal and child health, immunizations, tuberculosis screening and treatment, and Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, HIV/AIDS-related services. Despite inclusive stated policies for refugee access to health care on the international levels, potential barriers to that access include language, cultural preferences, high financial costs, administrative hurdles, and physical distance. Specific barriers and policies related to health service access also emerge based on the host country context. For example, primaquine, an often recommended malaria treatment is not currently licensed for use in Germany and must be ordered from outside the country. In Canada, barriers to healthcare access include the lack of adequately trained physicians, complex medical conditions of some refugees and the bureaucracy of medical coverage. There are also individual barriers to access such as language and transportation barriers, institutional barriers such as bureaucratic burdens and lack of entitlement knowledge, and systems level barriers such as conflicting policies, racism and physician workforce shortage. In the US, all officially designated Iraqi refugees had health insurance coverage compared to a little more than half of non-Iraqi immigrants in a Dearborn, Michigan, study. However, greater barriers existed around transportation, language and successful stress coping mechanisms for refugees versus other immigrants, in addition, refugees noted greater medical conditions. The study also found that refugees had higher healthcare utilization rate (92.1%) as compared to the US overall population (84.8%) and immigrants (58.6%) in the study population. Within Australia, officially designated refugees who qualify for temporary protection and offshore humanitarian refugees are eligible for health assessments, interventions and access to health insurance schemes and trauma-related counseling services. Despite being eligible to access services, barriers include economic constraints around perceived and actual costs carried by refugees. In addition, refugees must cope with a healthcare workforce unaware of the unique health needs of refugee populations. Perceived legal barriers such as fear that disclosing medical conditions prohibiting reunification of family members and current policies which reduce assistance programs may also limit access to health care services. Providing access to healthcare for refugees through integration into the current health systems of host countries may also be difficult when operating in a resource limited setting. In this context, barriers to healthcare access may include political aversion in the host country and already strained capacity of the existing health system. Political aversion to refugee access into the existing health system may stem from the wider issue of refugee resettlement. One approach to limiting such barriers is to move from a parallel administrative system in which UNHCR refugees may receive better healthcare than host nationals but is unsustainable financially and politically to that of an integrated care where refugee and host nationals receive equal and more improved care all around. In the 1980s, Pakistan attempted to address Soviet–Afghan War, Afghan refugee healthcare access through the creation of Basic Health Units inside the camps. Funding cuts closed many of these programs, forcing refugees to seek healthcare from the local government. In response to a protracted refugee situation in the West Nile district, Ugandan officials with UNHCR created an integrative healthcare model for the mostly Refugees of Sudan, Sudanese refugee population and Ugandan citizens. Local nationals now access health care in facilities initially created for refugees. One potential argument for limiting refugee access to healthcare is associated with costs with states desire to decrease health expenditure burdens. However, Germany found that restricting refugee access led to an increase actual expenditures relative to refugees which had full access to healthcare services. The legal restrictions on access to health care and the administrative barriers in Germany have been criticized since the 1990s for leading to delayed care, for increasing direct costs and administrative costs of health care, and for shifting the responsibility for care from the less expensive primary care sector to costly treatments for acute conditions in the secondary and tertiary sector.Exploitation

Refugee populations consist of people who are terrified and are away from familiar surroundings. There can be instances of exploitation at the hands of enforcement officials, citizens of the host country, and even United Nations peacekeepers. Instances of human rights violations, child labor, mental and physical trauma/torture, violence-related trauma, and Sexual exploitation and abuse in humanitarian response, sexual exploitation, especially of children, have been documented. In many refugee camps in three war-torn West African countries, Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Liberia, young girls were found to be exchanging sex for money, a handful of fruit, or even a bar of soap. Most of these girls were between 13 and 18 years of age. In most cases, if the girls had been forced to stay, they would have been forced into marriage. They became pregnant around the age of 15 on average. This happened as recently as in 2001. Parents tended to turn a blind eye because sexual exploitation had become a "mechanism of survival" in these camps. Large groups of displaced persons could be abused as refugees as weapons, "weapons" to threaten political enemies or neighbouring countries. It is for this reason amongst others that the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 10 aims to facilitate orderly, safe, regular and responsible mobility of people through planned and well-managed migration policies. In a November 2022 report, the Human Rights Watch accused Egypt’s law enforcement authorities of neglecting the female refugees and asylum seekers taking shelter in the African country, by failing to investigate their rape and sexual assault allegations made against the men of the country. According to the report, 11 incidents of sexual violence had been documented to have been committed in Egypt between the years 2016 and 2022. The sexual violence had been committed against seven women refugees of Sudanese and Yemeni descent and asylum seekers, which included one child. All of the women, including a transgender woman, complained of the country’s men raping them while four of them claimed assaults in more than two incidents. Whereas, the mother of the child assaulted sexually claimed that her 11 year-old daughter had been raped by a man. According to their collective statements of three women, the police in Egypt refused filing an incident report, while the remaining three claimed of being coerced into not filing a report, whereas, one of the women alleged she was sexually harassed on trying to report a rape.Crime

Little empirical evidence supports concerns that refugees commit crimes at higher rates than natives, and some evidence suggests they may even commit crime at lower rates than natives. Very rarely, refugees have been used and recruited as refugee militants or terrorists, and the humanitarian aid directed at refugee relief has very rarely been utilized to fund the acquisition of arms. Although conclusions from case studies of refugee mobilizations raised concerns that humanitarian aid may support rebel groups, more recent empirical evidence does not support the generalizability of these concerns. Support from a refugee-receiving state has rarely been used to enable refugees to mobilize militarily, enabling conflict to spread across borders. Historically, refugee populations have often been portrayed as a security threat. In the U.S and Europe, there has been much focus on the narrative that terrorists maintain networks amongst transnational, refugee, and migrant populations. This fear has been exaggerated into a modern-day Islamist terrorism Trojan Horse in which terrorists hide among refugees and penetrate host countries. 'Muslim-refugee-as-an-enemy-within' rhetoric is relatively new, but the underlying scapegoating of out-groups for domestic societal problems, fears and ethno-nationalist sentiment is not new. In the 1890s, the influx of Eastern European Jewish refugees to London coupled with the rise of anarchism in the city led to a confluence of threat-perception and fear of the refugee out-group. Populist rhetoric then too propelled debate over migration control and protecting national security. Cross-national empirical verification, or rejection, of populist suspicion and fear of refugees' threat to national security and terror-related activities is relatively scarce. Case studies suggest that the threat of an Islamist refugee Trojan House is highly exaggerated. Of the 800,000 refugees vetted through the resettlement program in the United States between 2001 and 2016, only five were subsequently arrested on terrorism charges; and 17 of the 600,000 Iraqis and Syrians who arrived in Germany in 2015 were investigated for terrorism. One study found that European jihadists tend to be 'homegrown': over 90% were residents of a European country and 60% had European citizenship. While the statistics do not support the rhetoric, a PEW Research Center survey of ten European countries (Hungary, Poland, Netherlands, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Greece, UK, France, and Spain) released on 11 July 2016, finds that the majority (ranges from 52% to 76%) of respondents in eight countries (Hungary, Poland, Netherlands, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Greece, and UK) think refugees increase the likelihood of terrorism in their country.Wike, Richard, Bruce Stokes, and Katie Simmons. "Europeans fear wave of refugees will mean more terrorism, fewer jobs." ''Pew Research Center'' 11 (2016). Since 1975, in the U.S., the risk of dying in a terror attack by a refugee is 1 in 3.6 billion per year; whereas, the odds of dying in a motor vehicle crash are 1 in 113, by state sanctioned execution 1 in 111,439, or by dog attack 1 in 114,622. In Europe, fear of immigration, Islamification and job and welfare benefits competition has fueled an increase in violence. Immigrants are perceived as a threat to ethno-nationalist identity and increase concerns over criminality and insecurity. In the PEW survey previously referenced, 50% of respondents believe that refugees are a burden due to job and social benefit competition. When Sweden received over 160,000 asylum seekers in 2015, it was accompanied by 50 attacks against asylum-seekers, which was more than four times the number of attacks that occurred in the previous four years. At the incident level, the 2011 Utøya Norway terror attack by Breivik demonstrates the impact of this threat perception on a country's risk from domestic terrorism, in particular ethno-nationalist extremism. Breivik portrayed himself as a protector of Norwegian ethnic identity and national security fighting against immigrant criminality, competition and welfare abuse and an Islamic takeover. Contrary to popular concerns that refugees cause crime, a more empirically grounded concern is that refugees are at high risk of being targets of anti-refugee violence. According to a 2018 study in the ''Journal of Peace Research'', states often resort to anti-refugee violence in response to terrorist attacks or security crises. The study notes that there is evidence to suggest that "the repression of refugees is more consistent with a scapegoating mechanism than the actual ties and involvement of refugees in terrorism." In 2018, US president Donald Trump made some comments about refugees and immigrants in Sweden; he stated that the high numbers of crimes are because of refugees and immigrants.Representation

The category of "refugee" tends to have a universalizing effect on those classified as such. It draws upon the common humanity of a mass of people in order to inspire public empathy, but doing so can have the unintended consequence of silencing refugee stories and erasing the political and historical factors that led to their present state. Humanitarian groups and media outlets often rely on images of refugees that evoke emotional responses and are said to speak for themselves. The refugees in these images, however, are not asked to elaborate on their experiences, and thus, their narratives are all but erased. From the perspective of the international community, "refugee" is a performative status equated with injury, ill health, and poverty. When people no longer display these traits, they are no longer seen as ideal refugees, even if they still fit the legal definition. For this reason, there is a need to improve current humanitarian efforts by acknowledging the "narrative authority, historical agency, and political memory" of refugees alongside their shared humanity. Dehistorizing and depoliticizing refugees can have dire consequences. Rwandan refugees in Tanzanian camps, for example, were pressured to return to their home country before they believed it was truly safe to do so. Despite the fact that refugees, drawing on their political history and experiences, claimed that Tutsi forces still posed a threat to them in Rwanda, their narrative was overshadowed by the U.N. assurances of safety. When the refugees did return home, reports of reprisals against them, land seizures, disappearances, and incarceration abounded, as they had feared.Employment

Integrating refugees into the workforce is one of the most important steps to overall integration of this particular migrant group. Many refugees are unemployed, under-employed, under-paid and work in the informal economy, if not receiving public assistance. Refugees encounter many barriers in receiving countries in finding and sustaining employment commensurate with their experience and expertise. A systemic barrier that is situated across multiple levels (i.e. institutional, organizational and individual levels) is coined "Refugee employment, canvas ceiling".Education

Refugee children come from many different backgrounds, and their reasons for resettlement are even more diverse. The number of refugee children has continued to increase as conflicts interrupt communities at a global scale. In 2014 alone, there were approximately 32 List of ongoing armed conflicts, armed conflicts in 26 countries around the world, and this period saw the highest number of refugees ever recordedDryden-Peterson, S. (2015). The Educational Experiences of Refugee Children in Countries of First Asylum (Rep.). Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Refugee children experience traumatic events in their lives that can affect their learning capabilities, even after they have resettled in first or second settlement countries. Educators such as teachers, counselors, and school staff, along with the school environment, are key in facilitating socialization and acculturation of recently arrived refugee and immigrant children in their new schools.Obstacles

The experiences children go through during times of armed conflict can impede their ability to learn in an educational setting. Schools experience drop-outs of refugee and Immigration, immigrant students from an array of factors such as: rejection by peers, low self-esteem, antisocial behavior, negative perceptions of their academic ability, and lack of support from school staff and parents. Because refugees come from various regions globally with their own cultural, religious, linguistic, and home practices, the new school culture can conflict with the home culture, causing tension between the student and their family. Aside from students, teachers and school staff also face their own obstacles in working with refugee students. They have concerns about their ability to meet the mental, physical, emotional, and educational needs of students. One study of newly arrived Bantus (Somalia), Bantu students from Somalia in a Chicago school questioned whether schools were equipped to provide them with a quality education that met the needs of the pupils. The students were not aware of how to use pencils, which caused them to break the tips requiring frequent sharpening. Teachers may even see refugee students as different from other immigrant groups, as was the case with the Bantu pupils. Teachers may sometimes feel that their work is made harder because of the pressures to meet Standards-based education reform in the United States, state requirements for testing. With refugee children falling behind or struggling to catch up, it can overwhelm teachers and administrators, further leading to anger. Not all students adjust the same way to their new setting. One student may take only three months, while others may take four years. One study found that even in their fourth year of schooling, Lao and Vietnamese boat people, Vietnamese refugee students in the US were still in a transitional status.Liem Thanh Nguyen, & Henkin, A. (1980)Reconciling Differences: Indochinese Refugee Students in American Schools

. The Clearinghouse, 54(3), 105–108. Refugee students continue to encounter difficulties throughout their years in schools that can hinder their ability to learn. Furthermore, to provide proper support, educators must consider the experiences of students before they settled the US. In their first settlement countries, refugee students may encounter negative experiences with education that they can carry with them post settlement. For example: * Frequent disruption in their education as they move from place to place * Limited access to schooling * Language barriers * Little resources to support language development and learning, and more Statistics found that in places such as Uganda and Kenya, there were gaps in refugee students attending schools. It found that 80% of refugees in Uganda were attending schools, whereas only 46% of students were attending schools in Kenya. Furthermore, for secondary education, secondary levels, the numbers were much lower. There was only 1.4% of refugee students attending schools in Malaysia. This trend is evident across several first settlement countries and carry negative impacts on students once they arrive to their permanent settlement homes, such as the US, and have to navigate a new education system. Unfortunately, some refugees do not have a chance to attend schools in their first settlement countries because they are considered Illegal immigration, undocumented immigrants in places like Malaysia for 2015 Rohingya refugee crisis, Rohingya refugees. In other cases, such as Burundians in Tanzania, refugees can get more access to education while in displacement than in their home countries.

Overcoming obstacles

All students need some form of support to help them overcome obstacles and challenges they may face in their lives, especially refugee children who may experience frequent disruptions. There are a few ways in which schools can help refugee students overcome obstacles to attain success in their new homes: * Respect the cultural differences amongst refugees and the new home culture * Individual efforts to welcome refugees to prevent feelings of isolation * Educator support * Student centered pedagogy as opposed to teacher centered * Building relationships with the students * Offering praise and providing Affirmations (New Age), affirmations * Providing extensive support and designing curriculum for students to read, write, and speak in their native languages. One school in NYC has found a method that works for them to help refugee students succeed. This school creates support for language and literacies, which promotes students using English and their native languages to complete projects. Furthermore, they have a learning centered pedagogy, which promotes the idea that there are multiple entry points to engage the students in learning. Both strategies have helped refugee students succeed during their transition into US schools. Various websites contain resources that can help school staff better learn to work with refugee students such aBridging Refugee Youth and Children's Services

With the support of educators and the school community, education can help rebuild the academic, social, and emotional well-being of refugee students who have suffered from past and present Psychological trauma, trauma, Social exclusion, marginalization, and social alienation.

Cultural differences

It is important to understand the cultural differences amongst newly arrived refugees and school culture, such as that of the U.S. This can be seen as problematic because of the frequent disruptions that it can create in a classroom setting. In addition, because of the differences in language and culture, students are often placed in lower classes due to their lack of English proficiency. Students can also be made to repeat classes because of their lack of English proficiency, even if they have mastered the content of the class. When schools have the resources and are able to provide separate classes for refugee students to develop their English skills, it can take the average refugee students only three months to catch up with their peers. This was the case with Somali refugees at some primary schools in Nairobi. The histories of refugee students are often hidden from educators, resulting in cultural misunderstandings. However, when teachers, school staff, and peers help refugee students develop a positive cultural identity, it can help buffer the negative effects refugees' experiences have on them, such as poor academic performance, isolation, and discrimination.Refugee crisis

Refugee crisis can refer to movements of large groups of forced displacement, displaced persons, who could be either internally displaced persons, refugees or other migrants. It can also refer to incidents in the country of origin or departure, to large problems whilst on the move or even after arrival in a safe country that involve large groups of displaced persons.

At the end of 2020, the UNHCR estimated the number of forcibly displaced people to be about 82.4 million worldwide. Of those, 26.4 million (nearly a third) are refugees while 4.1 million were classified as asylum seekers and 48 million being internally displaced. 68% of refugees originates from just five countries (Syria, Venezuela, Afghanistan and South Sudan and Myanmar). 86% of refugees are hosted in developing countries, with Turkey, hosting 3.7 million refugees, being the top hosting country.

In 2006, there were 8.4 million UNHCR registered refugees worldwide, the lowest number since 1980. At the end of 2015, there were 16.1 million refugees worldwide. When adding the 5.2 million

Refugee crisis can refer to movements of large groups of forced displacement, displaced persons, who could be either internally displaced persons, refugees or other migrants. It can also refer to incidents in the country of origin or departure, to large problems whilst on the move or even after arrival in a safe country that involve large groups of displaced persons.

At the end of 2020, the UNHCR estimated the number of forcibly displaced people to be about 82.4 million worldwide. Of those, 26.4 million (nearly a third) are refugees while 4.1 million were classified as asylum seekers and 48 million being internally displaced. 68% of refugees originates from just five countries (Syria, Venezuela, Afghanistan and South Sudan and Myanmar). 86% of refugees are hosted in developing countries, with Turkey, hosting 3.7 million refugees, being the top hosting country.

In 2006, there were 8.4 million UNHCR registered refugees worldwide, the lowest number since 1980. At the end of 2015, there were 16.1 million refugees worldwide. When adding the 5.2 million See also

* Asylum shopping * Conservation refugee, people displaced when conservation areas are created * Church asylum * Deportation * Diaspora, a mass movement of population, usually forced by war or natural disaster * Emergencybnb, a website to find accommodation for refugees * Emergency evacuation * Forced displacement in popular culture * Ghost town#Ghost town repopulation, Ghost town repopulation * HIAS * Homo sacer, a banned person who may be killed by anybody * Human migration * List of largest refugee crises * List of people granted asylum * List of refugees * Mehran Karimi Nasseri, an Iranian refugee who lived in Charles de Gaulle Airport * Nansen Refugee Award * No person is illegal, network that represents non-resident immigrants * Open borders * Political asylum * Private Sponsorship of Refugees Program - resettling refugees with the support and funding from private or joint government-private sponsorship * Queer migration * RAPAR, Refugee and Asylum Participatory Action Research * Refugee crisis * Refugee health * Refugee Nation, a plan to create a nation for refugees * Refugee Phrasebook * Refugee Radio * Refugee Studies Centre * Right of asylum * Refugee children and refugee women * Third country resettlementFootnotes

References

Works cited

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* Fell, Peter and Debra Hayes (2007), "What are they doing here? A critical guide to asylum and immigration." Venture Press. * Gibney, Matthew J. (2004), ''"The Ethics and Politics of Asylum: Liberal Democracy and the Response to Refugees", Cambridge University Press. * Schaeffer, P (2010), 'Refugees: On the economics of political migration.' International Migration 48(1): 1–22. * Refugee number statistics taken from 'Refugee', Encyclopædia Britannica CD Edition (2004). * Reyhani, Adel-Naim (2022), ''"Refugees"'', in Elgar Encyclopedia of Human Rights, Edward Elgar Publishing. * Waters, Tony (2001), ''Bureaucatizing the Good Samaritan'', Westview Press. * UNHCR (2001)Refugee protection: A Guide to International Refugee Law

UNHCR, Inter-Parliamentary Union

External links

UNHCR RefWorld

Bridging Youth Refugees and Children's Services

{{Authority control Aftermath of war Forced migration Population Refugees, Right of asylum