Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one

race over another.

It may also mean

prejudice,

discrimination

Discrimination is the act of making unjustified distinctions between people based on the groups, classes, or other categories to which they belong or are perceived to belong. People may be discriminated on the basis of race, gender, age, relig ...

, or antagonism directed against other people because they are of a different race or

ethnicity

An ethnic group or an ethnicity is a grouping of people who identify with each other on the basis of shared attributes that distinguish them from other groups. Those attributes can include common sets of traditions, ancestry, language, history, ...

.

Modern variants of racism are often based in social perceptions of biological differences between peoples. These views can take the form of

social actions, practices or beliefs, or

political systems in which different races are ranked as inherently superior or inferior to each other, based on presumed shared inheritable traits, abilities, or qualities.

There have been attempts to legitimize racist beliefs through scientific means, such as

scientific racism, which have been overwhelmingly shown to be unfounded. In terms of political systems (e.g.

apartheid) that support the expression of prejudice or aversion in discriminatory practices or laws, racist ideology may include associated social aspects such as

nativism,

xenophobia,

otherness,

segregation,

hierarchical

A hierarchy (from Greek: , from , 'president of sacred rites') is an arrangement of items (objects, names, values, categories, etc.) that are represented as being "above", "below", or "at the same level as" one another. Hierarchy is an important ...

ranking, and

supremacism

Supremacism is the belief that a certain group of people is superior to all others. The supposed superior people can be defined by age, gender, race, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, language, social class, ideology, nation, culture, ...

.

While the concepts of race and ethnicity are considered to be separate in contemporary

social science, the two terms have a long history of equivalence in popular usage and older social science literature. "Ethnicity" is often used in a sense close to one traditionally attributed to "race", the division of human groups based on qualities assumed to be essential or innate to the group (e.g. shared

ancestry

An ancestor, also known as a forefather, fore-elder or a forebear, is a parent or (recursively) the parent of an antecedent (i.e., a grandparent, great-grandparent, great-great-grandparent and so forth). ''Ancestor'' is "any person from whom ...

or shared behavior). ''Racism'' and ''

racial discrimination'' are often used to describe discrimination on an ethnic or cultural basis, independent of whether these differences are described as racial. According to the

United Nations's

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, there is no distinction between the terms "racial" and "ethnic" discrimination. It further concludes that superiority based on racial differentiation is

scientifically false, morally condemnable, socially

unjust

Injustice is a quality relating to unfairness or undeserved outcomes. The term may be applied in reference to a particular event or situation, or to a larger status quo. In Western philosophy and jurisprudence, injustice is very commonly—but n ...

, and dangerous. The convention also declared that there is no justification for racial discrimination, anywhere, in theory or in practice.

Racism is a relatively modern concept, arising in the European

age of imperialism, the subsequent growth of

capitalism, and especially the

Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and i ...

,

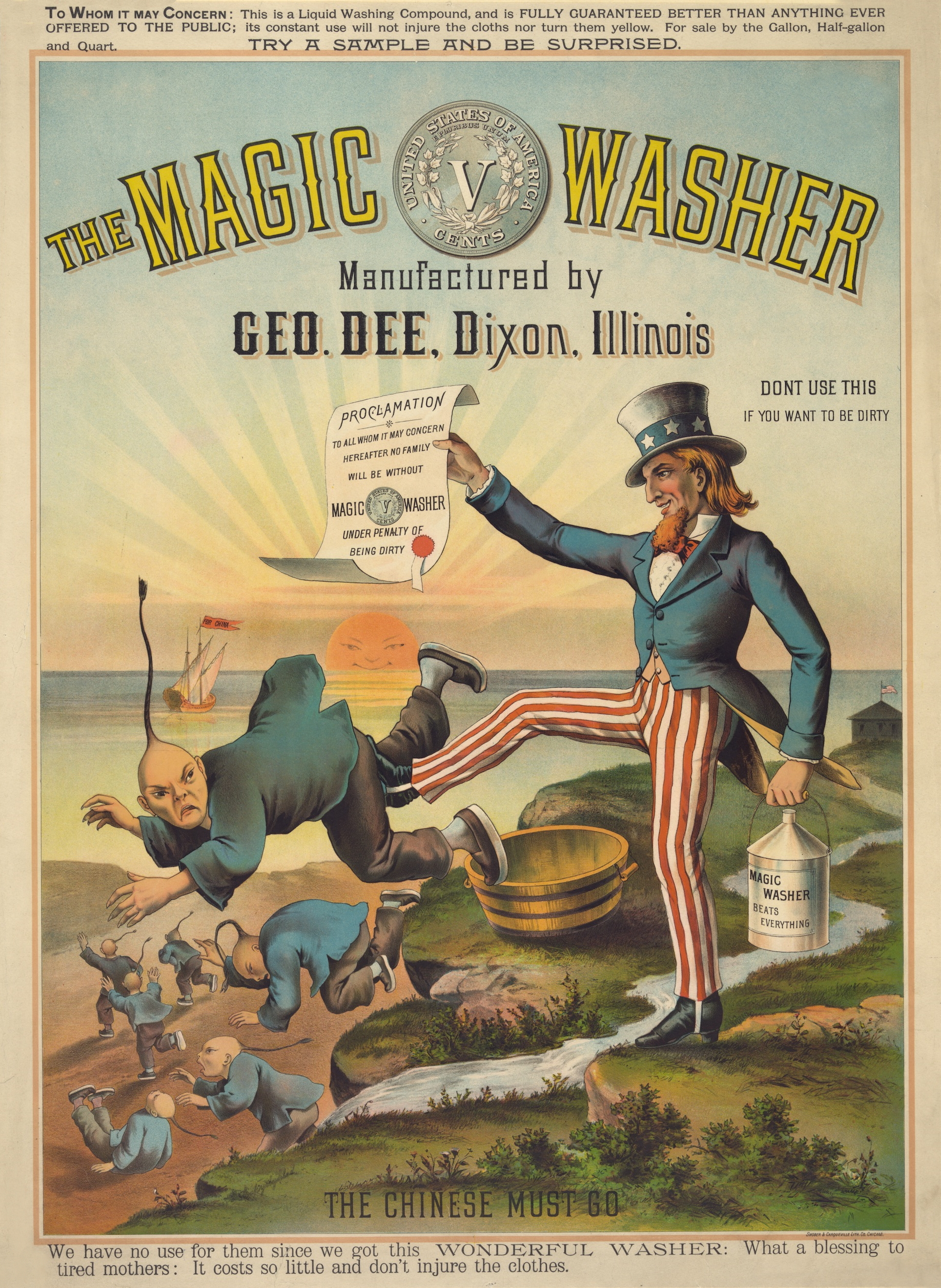

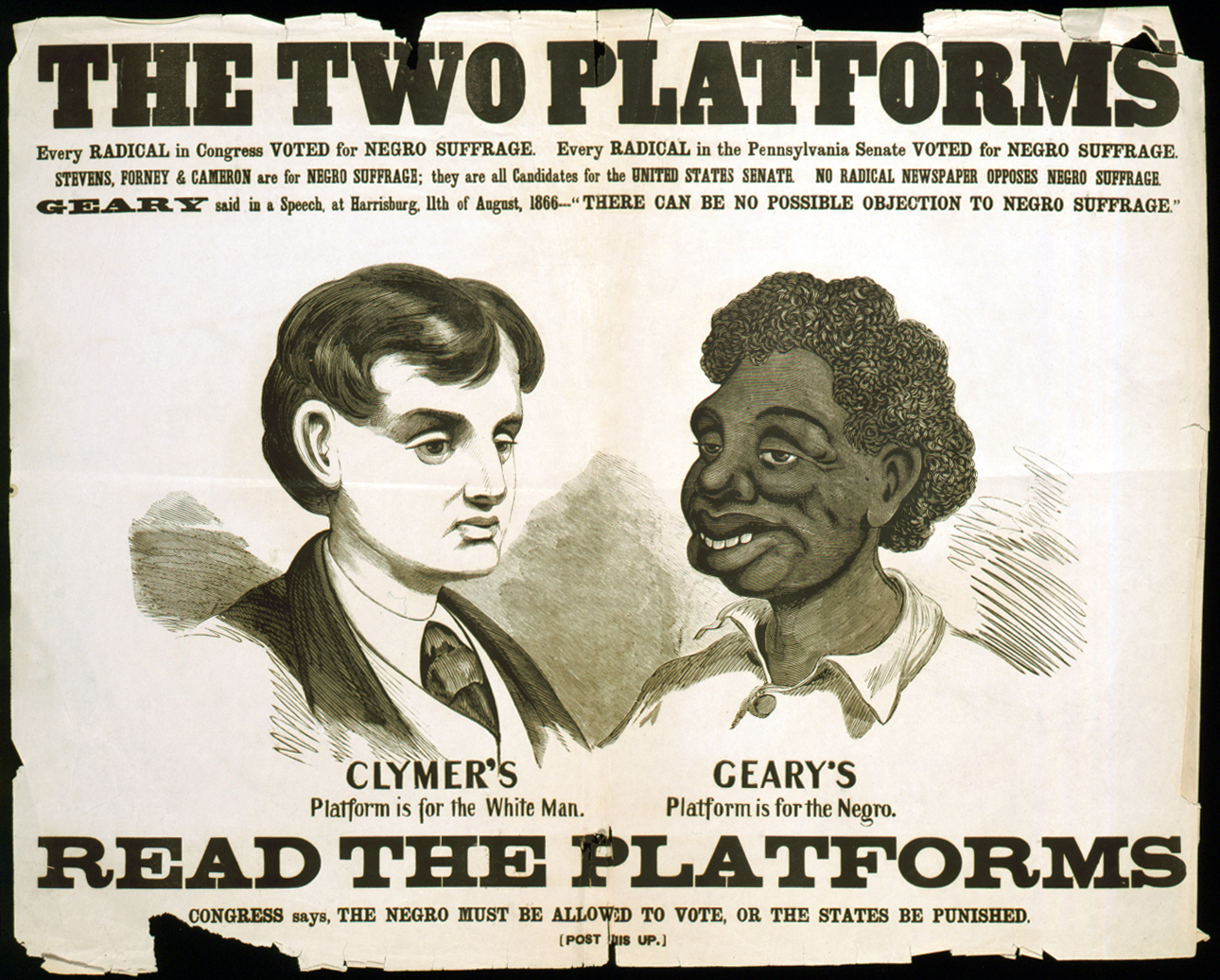

of which it was a major driving force. It was also a major force behind

racial segregation in the United States

In the United States, racial segregation is the systematic separation of facilities and services such as Housing in the United States, housing, Healthcare in the United States, healthcare, Education in the United States, education, Employment in ...

in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and of

apartheid in South Africa; 19th and 20th-century racism in

Western culture is particularly well documented and constitutes a reference point in studies and discourses about racism.

Racism has played a role in

genocides such as

the Holocaust, the

Armenian genocide, the

Rwandan genocide, and the

Genocide of Serbs in the Independent State of Croatia, as well as colonial projects including the

European colonization of

the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America, North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World. ...

,

Africa,

Asia, and the

population transfer in the Soviet Union

From 1930 to 1952, the government of the Soviet Union, on the orders of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin under the direction of the NKVD official Lavrentiy Beria, forcibly transferred populations of various groups. These actions may be classified ...

including deportations of indigenous minorities.

Indigenous peoples have been—and are—often subject to racist attitudes.

Etymology, definition, and usage

In the 19th century, many scientists subscribed to the belief that the human population can be divided into races. The term ''racism'' is a noun describing the state of being racist, i.e., subscribing to the belief that the human population can or should be classified into races with differential abilities and dispositions, which in turn may motivate a political ideology in which rights and privileges are differentially distributed based on racial categories. The term "racist" may be an adjective or a noun, the latter describing a person who holds those beliefs.

The origin of the root word "race" is not clear. Linguists generally agree that it came to the English language from

Middle French, but there is no such agreement on how it generally came into Latin-based languages. A recent proposal is that it derives from the Arabic ''ra's'', which means "head, beginning, origin" or the

Hebrew ''rosh'', which has a similar meaning. Early race theorists generally held the view that some races were inferior to others and they consequently believed that the differential treatment of races was fully justified.

These early theories guided

pseudo-scientific research assumptions; the collective endeavors to adequately define and form hypotheses about racial differences are generally termed

scientific racism, though this term is a misnomer, due to the lack of any actual science backing the claims.

Most

biologist

A biologist is a scientist who conducts research in biology. Biologists are interested in studying life on Earth, whether it is an individual cell, a multicellular organism, or a community of interacting populations. They usually specialize in ...

s,

anthropologists, and

sociologists reject a

taxonomy of races in favor of more specific and/or empirically verifiable criteria, such as

geography, ethnicity, or a history of

endogamy.

Human genome research indicates that race is not a meaningful genetic classification of humans.

An entry in the ''

Oxford English Dictionary'' (2008) defines

racialism as "

earlier term than racism, but now largely superseded by it", and cites the term "racialism" in a 1902 quote. The revised ''Oxford English Dictionary'' cites the shorter term "racism" in a quote from the year 1903. It was defined by the ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (2nd edition 1989) as "

e theory that distinctive human characteristics and abilities are determined by race"; the same dictionary termed ''racism'' a

synonym

A synonym is a word, morpheme, or phrase that means exactly or nearly the same as another word, morpheme, or phrase in a given language. For example, in the English language, the words ''begin'', ''start'', ''commence'', and ''initiate'' are all ...

of ''racialism'': "belief in the superiority of a particular race". By the end of

World War II, ''racism'' had acquired the same supremacist connotations formerly associated with ''racialism'': ''racism'' by then implied racial

discrimination

Discrimination is the act of making unjustified distinctions between people based on the groups, classes, or other categories to which they belong or are perceived to belong. People may be discriminated on the basis of race, gender, age, relig ...

, racial

supremacism

Supremacism is the belief that a certain group of people is superior to all others. The supposed superior people can be defined by age, gender, race, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, language, social class, ideology, nation, culture, ...

, and a harmful intent. The term "race hatred" had also been used by sociologist

Frederick Hertz in the late 1920s.

As its history indicates, the popular use of the word ''racism'' is relatively recent. The word came into widespread usage in the

Western world in the 1930s, when it was used to describe the social and political ideology of

Nazism, which treated "race" as a naturally given political unit. It is commonly agreed that racism existed before the coinage of the word, but there is not a wide agreement on a single definition of what racism is and what it is not.

Today, some scholars of racism prefer to use the concept in the plural ''racisms'', in order to emphasize its many different forms that do not easily fall under a single definition. They also argue that different forms of racism have characterized different historical periods and geographical areas.

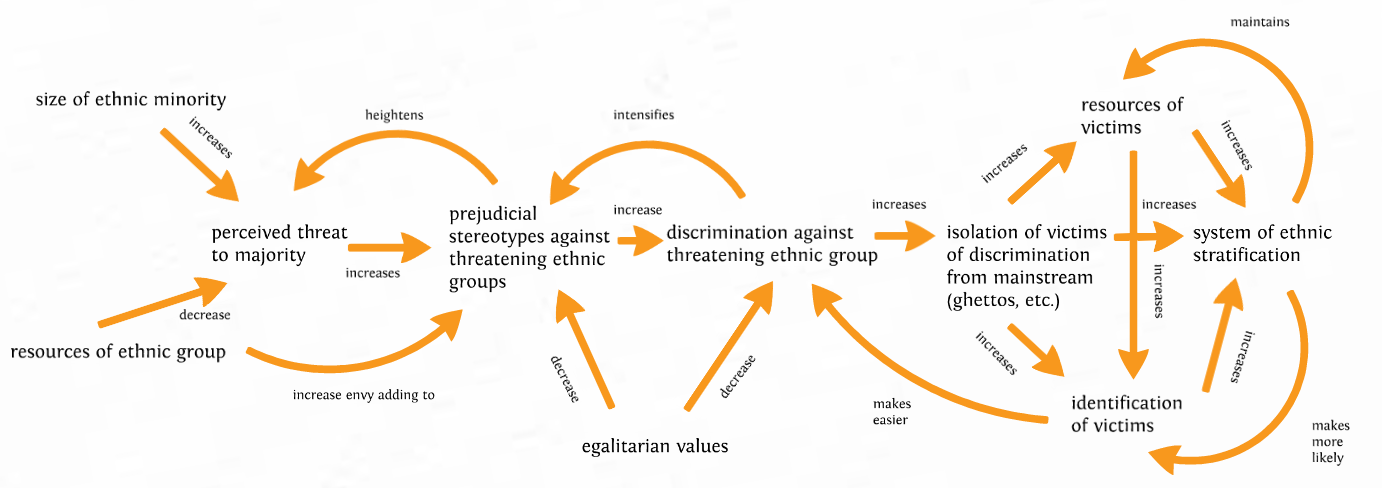

Garner (2009: p. 11) summarizes different existing definitions of racism and identifies three common elements contained in those definitions of racism. First, a historical, hierarchical

power relationship between groups; second, a set of ideas (an ideology) about racial differences; and, third, discriminatory actions (practices).

Legal

Though many countries around the globe have passed

laws related to race and discrimination, the first significant international

human rights instrument developed by the United Nations (UN) was the

Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR),

which was adopted by the

United Nations General Assembly in 1948. The UDHR recognizes that if people are to be treated with dignity, they require

economic rights,

social rights including education, and the rights to

cultural

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human Society, societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, and habits of the ...

and political participation and

civil liberty. It further states that everyone is entitled to these rights "without distinction of any kind, such as race,

colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion,

national or

social origin, property, birth or other status".

The UN does not define "racism"; however, it does define "racial discrimination". According to the 1965 UN

International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination,

The term "racial discrimination" shall mean any distinction, exclusion, restriction, or preference based on race, colour, descent, or national or ethnic origin that has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal footing, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural or any other field of public life.

In their 1978

United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Declaration on Race and Racial Prejudice (Article 1), the UN states, "All human beings belong to a single species and are descended from a common stock. They are born equal in dignity and rights and all form an integral part of humanity."

The UN definition of racial discrimination does not make any distinction between

discrimination based on ethnicity and race, in part because the distinction between the two has been a matter of debate among

academics, including

anthropologists. Similarly, in

British law, the phrase ''racial group'' means "any group of people who are defined by reference to their race, colour, nationality (including citizenship) or ethnic or national origin".

In Norway, the word "race" has been removed from national laws concerning discrimination because the use of the phrase is considered problematic and unethical. The Norwegian Anti-Discrimination Act bans discrimination based on ethnicity, national origin, descent, and skin color.

Social and behavioral sciences

Sociologists, in general, recognize "race" as a

social construct. This means that, although the concepts of race and racism are based on observable biological characteristics, any conclusions drawn about race on the basis of those observations are heavily influenced by cultural ideologies. Racism, as an ideology, exists in a society at both the individual and institutional level.

While much of the research and work on racism during the last half-century or so has concentrated on "white racism" in the Western world, historical accounts of race-based social practices can be found across the globe.

[Gossett, Thomas F. ''Race: The History of an Idea in America''. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997. ] Thus, racism can be broadly defined to encompass individual and group prejudices and acts of discrimination that result in material and cultural advantages conferred on a majority or a dominant social group. So-called "white racism" focuses on societies in which white populations are the majority or the dominant social group. In studies of these majority white societies, the aggregate of material and cultural advantages is usually termed "

white privilege".

Race and race relations are prominent areas of study in

sociology and

economics. Much of the sociological literature focuses on white racism. Some of the earliest sociological works on racism were penned by sociologist

W. E. B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois ( ; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American-Ghanaian sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist. Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in ...

, the first African American to earn a doctoral degree from

Harvard University. Du Bois wrote, "

e problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the

color line."

Wellman (1993) defines racism as "culturally sanctioned beliefs, which, regardless of intentions involved, defend the advantages whites have because of the subordinated position of racial minorities".

In both sociology and economics, the outcomes of racist actions are often measured by the

inequality in

income,

wealth,

net worth

Net worth is the value of all the non-financial and financial assets owned by an individual or institution minus the value of all its outstanding liabilities. Since financial assets minus outstanding liabilities equal net financial assets, net ...

, and access to other cultural resources (such as education), between racial groups.

In sociology and

social psychology,

racial identity

A race is a categorization of humans based on shared physical or social qualities into groups generally viewed as distinct within a given society. The term came into common usage during the 1500s, when it was used to refer to groups of variou ...

and the acquisition of that identity, is often used as a variable in racism studies. Racial ideologies and racial identity affect individuals' perception of race and discrimination. Cazenave and Maddern (1999) define racism as "a highly organized system of 'race'-based group privilege that operates at every level of society and is held together by a sophisticated ideology of color/'race' supremacy. Racial centrality (the extent to which a culture recognizes individuals' racial identity) appears to affect the degree of discrimination African-American young adults perceive whereas racial ideology may buffer the detrimental emotional effects of that discrimination."

Sellers and Shelton (2003) found that a relationship between racial discrimination and emotional distress was moderated by racial ideology and social beliefs.

Some sociologists also argue that, particularly in the West, where racism is often

negatively sanctioned in society, racism has changed from being a blatant to a more covert expression of racial prejudice. The "newer" (more hidden and less easily detectable) forms of racism—which can be considered embedded in social processes and structures—are more difficult to explore and challenge. It has been suggested that, while in many countries overt or explicit racism has become increasingly

taboo, even among those who display egalitarian explicit attitudes, an

implicit

Implicit may refer to:

Mathematics

* Implicit function

* Implicit function theorem

* Implicit curve

* Implicit surface

* Implicit differential equation

Other uses

* Implicit assumption, in logic

* Implicit-association test, in social psychology

...

or

aversive racism

Aversive racism is a theory proposed by Samuel L. Gaertner & John F. Dovidio (1986), according to which negative evaluations of racial/ethnic minorities are realized by a persistent avoidance of interaction with other racial and ethnic groups. As ...

is still maintained subconsciously.

This process has been studied extensively in social psychology as implicit associations and

implicit attitudes, a component of

implicit cognition. Implicit attitudes are evaluations that occur without conscious awareness towards an attitude object or the self. These evaluations are generally either favorable or unfavorable. They come about from various influences in the individual experience. Implicit attitudes are not consciously identified (or they are inaccurately identified) traces of past experience that mediate favorable or unfavorable feelings, thoughts, or actions towards social objects.

These feelings, thoughts, or actions have an influence on behavior of which the individual may not be aware.

Therefore, subconscious racism can influence our visual processing and how our minds work when we are subliminally exposed to faces of different colors. In thinking about crime, for example,

social psychologist Jennifer L. Eberhardt

Jennifer Lynn Eberhardt (born 1965) is an American social psychologist who is currently a professor in the Department of Psychology at Stanford University. Eberhardt has been responsible for major contributions on investigating the consequences ...

(2004) of

Stanford University

Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, is a private research university in Stanford, California. The campus occupies , among the largest in the United States, and enrolls over 17,000 students. Stanford is consider ...

holds that, "blackness is so associated with crime you're ready to pick out these crime objects."

Such exposures influence our minds and they can cause subconscious racism in our behavior towards other people or even towards objects. Thus, racist thoughts and actions can arise from stereotypes and fears of which we are not aware.

For example, scientists and activists have warned that the use of the stereotype "Nigerian Prince" for referring to

advance-fee scam

An advance-fee scam is a form of fraud and is one of the most common types of confidence tricks. The scam typically involves promising the victim a significant share of a large sum of money, in return for a small up-front payment, which the frauds ...

mers is racist, i.e. "reducing Nigeria to a nation of scammers and fraudulent princes, as some people still do online, is a

stereotype

In social psychology, a stereotype is a generalized belief about a particular category of people. It is an expectation that people might have about every person of a particular group. The type of expectation can vary; it can be, for example ...

that needs to be called out".

Humanities

Language,

linguistics, and

discourse

Discourse is a generalization of the notion of a conversation to any form of communication. Discourse is a major topic in social theory, with work spanning fields such as sociology, anthropology, continental philosophy, and discourse analysis. ...

are active areas of study in the

humanities, along with literature and the arts.

Discourse analysis seeks to reveal the meaning of race and the actions of racists through careful study of the ways in which these factors of human society are described and discussed in various written and oral works. For example, Van Dijk (1992) examines the different ways in which descriptions of racism and racist actions are depicted by the perpetrators of such actions as well as by their victims. He notes that when descriptions of actions have negative implications for the majority, and especially for white elites, they are often seen as controversial and such controversial interpretations are typically marked with quotation marks or they are greeted with expressions of distance or doubt. The previously cited book, ''

The Souls of Black Folk'' by W.E.B. Du Bois, represents early

African-American literature that describes the author's experiences with racism when he was traveling in the

South

South is one of the cardinal directions or Points of the compass, compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Pro ...

as an African American.

Much American fictional literature has focused on issues of racism and the black "racial experience" in the US, including works written by whites, such as ''

Uncle Tom's Cabin'', ''

To Kill a Mockingbird'', and ''

Imitation of Life

Imitation (from Latin ''imitatio'', "a copying, imitation") is a behavior whereby an individual observes and replicates another's behavior. Imitation is also a form of that leads to the "development of traditions, and ultimately our culture. I ...

'', or even the non-fiction work ''

Black Like Me

''Black Like Me'', first published in 1961, is a nonfiction book by journalist John Howard Griffin recounting his journey in the Deep South of the United States, at a time when African-Americans lived under racial segregation. Griffin was a nat ...

''. These books, and others like them, feed into what has been called the "

white savior narrative in film", in which the heroes and heroines are white even though the story is about things that happen to black characters.

Textual analysis of such writings can contrast sharply with black authors' descriptions of African Americans and their experiences in US society. African-American writers have sometimes been portrayed in

African-American studies as retreating from racial issues when they write about "

whiteness", while others identify this as an African-American literary tradition called "the literature of white estrangement", part of a multi-pronged effort to challenge and dismantle

white supremacy in the US.

Popular usage

According to dictionaries, the word is commonly used to describe prejudice and discrimination based on race.

Racism can also be said to describe a condition in society in which a dominant racial group benefits from the

oppression of others, whether that group wants such benefits or not. Foucauldian scholar Ladelle McWhorter, in her 2009 book, ''Racism and Sexual Oppression in Anglo-America: A Genealogy'', posits modern racism similarly, focusing on the notion of a dominant group, usually whites, vying for racial purity and progress, rather than an overt or obvious ideology focused on the oppression of nonwhites.

In popular usage, as in some academic usage, little distinction is made between "racism" and "

ethnocentrism

Ethnocentrism in social science and anthropology—as well as in colloquial English discourse—means to apply one's own culture or ethnicity as a frame of reference to judge other cultures, practices, behaviors, beliefs, and people, instead of ...

". Often, the two are listed together as "racial and ethnic" in describing some action or outcome that is associated with prejudice within a majority or dominant group in society. Furthermore, the meaning of the term racism is often conflated with the terms prejudice,

bigotry, and discrimination. Racism is a complex concept that can involve each of those; but it cannot be equated with, nor is it synonymous, with these other terms.

The term is often used in relation to what is seen as prejudice within a minority or subjugated group, as in the concept of

reverse racism. "Reverse racism" is a concept often used to describe acts of discrimination or hostility against members of a dominant racial or ethnic group while favoring members of minority groups.

This concept has been used especially in the United States in debates over

color-conscious Color consciousness is a theory stating that equality under the law is insufficient to address racial inequalities in society. It rejects the concept of fundamental racial differences, but holds that physical differences such as skin color can and d ...

policies (such as

affirmative action) intended to remedy racial inequalities. However, many experts and other commenters view reverse racism as a myth rather than a reality. Scholars commonly define racism not only in terms of individual prejudice, but also in terms of a power structure that protects the interests of the dominant culture and actively discriminates against ethnic minorities. From this perspective, while members of ethnic minorities may be prejudiced against members of the dominant culture, they lack the political and economic power to actively oppress them, and they are therefore not practicing "racism".

Aspects

The ideology underlying racism can manifest in many aspects of social life. Such aspects are described in this section, although the list is not exhaustive.

Aversive racism

Aversive racism is a form of implicit racism, in which a person's unconscious negative evaluations of racial or ethnic minorities are realized by a persistent avoidance of interaction with other racial and ethnic groups. As opposed to traditional, overt racism, which is characterized by overt hatred for and explicit discrimination against racial/ethnic minorities, aversive racism is characterized by more complex,

ambivalent expressions and attitudes.

Aversive racism is similar in implications to the concept of symbolic or modern racism (described below), which is also a form of implicit, unconscious, or covert attitude which results in unconscious forms of discrimination.

The term was coined by Joel Kovel to describe the subtle racial behaviors of any ethnic or racial group who rationalize their aversion to a particular group by appeal to rules or stereotypes.

People who behave in an aversively racial way may profess egalitarian beliefs, and will often deny their racially motivated behavior; nevertheless they change their behavior when dealing with a member of another race or ethnic group than the one they belong to. The motivation for the change is thought to be implicit or subconscious. Experiments have provided empirical support for the existence of aversive racism. Aversive racism has been shown to have potentially serious implications for decision making in employment, in legal decisions and in helping behavior.

Color blindness

In relation to racism, color blindness is the disregard of racial characteristics in

social interaction

A social relation or also described as a social interaction or social experience is the fundamental unit of analysis within the social sciences, and describes any voluntary or involuntary interpersonal relationship between two or more individuals ...

, for example in the rejection of affirmative action, as a way to address the results of past patterns of discrimination. Critics of this attitude argue that by refusing to attend to racial disparities, racial color blindness in fact unconsciously perpetuates the patterns that produce racial inequality.

argues that color blind racism arises from an "abstract

liberalism, biologization of culture, naturalization of racial matters, and minimization of racism".

Color blind practices are "subtle,

institution

Institutions are humanly devised structures of rules and norms that shape and constrain individual behavior. All definitions of institutions generally entail that there is a level of persistence and continuity. Laws, rules, social conventions a ...

al, and apparently nonracial"

because race is explicitly ignored in decision-making. If race is disregarded in predominantly white populations, for example, whiteness becomes the

normative standard, whereas

people of color are

othered, and the racism these individuals experience may be minimized or erased.

At an individual level, people with "color blind prejudice" reject racist ideology, but also reject systemic policies intended to fix

institutional racism.

Cultural

Cultural racism manifests as societal beliefs and customs that promote the assumption that the products of a given culture, including the language and traditions of that culture, are superior to those of other cultures. It shares a great deal with

xenophobia, which is often characterized by fear of, or aggression toward, members of an

outgroup Outgroup may refer to:

* Outgroup (cladistics), an evolutionary-history concept

* Outgroup (sociology), a social group

{{disambig ...

by members of an

ingroup.

In that sense it is also similar to

communalism as used in South Asia.

Cultural racism exists when there is a widespread acceptance of stereotypes concerning diverse ethnic or population groups. Whereas racism can be characterised by the belief that one race is inherently superior to another, cultural racism can be characterised by the belief that one culture is inherently superior to another.

Economic

Historical economic or social disparity is alleged to be a form of

discrimination

Discrimination is the act of making unjustified distinctions between people based on the groups, classes, or other categories to which they belong or are perceived to belong. People may be discriminated on the basis of race, gender, age, relig ...

caused by past racism and historical reasons, affecting the present generation through deficits in the formal education and kinds of preparation in previous generations, and through primarily unconscious racist attitudes and actions on members of the general population.

Economic discrimination may lead to choices that perpetuate racism. For example, color photographic film was tuned for white skin as are automatic soap dispensers and

facial recognition systems.

In 2011,

Bank of America agreed to pay $335 million to settle a federal government claim that its mortgage division, Countrywide Financial,

discriminated

Discrimination is the act of making unjustified distinctions between people based on the groups, classes, or other categories to which they belong or are perceived to belong. People may be discriminated on the basis of race, gender, age, relig ...

against black and Hispanic homebuyers.

Institutional

Institutional racism

Institutional racism (also known as

structural racism,

state racism or systemic racism) is racial discrimination by governments, corporations, religions, or educational institutions or other large organizations with the power to influence the lives of many individuals.

Stokely Carmichael is credited for coining the phrase ''institutional racism'' in the late 1960s. He defined the term as "the collective failure of an organization to provide an appropriate and professional service to people because of their colour, culture or ethnic origin".

Maulana Karenga argued that racism constituted the destruction of culture, language, religion, and human possibility and that the effects of racism were "the morally monstrous destruction of human possibility involved redefining African humanity to the world, poisoning past, present and future relations with others who only know us through this stereotyping and thus damaging the truly human relations among peoples".

Othering

Othering is the term used by some to describe a system of discrimination whereby the characteristics of a group are used to distinguish them as separate from the norm.

Othering plays a fundamental role in the history and continuation of racism. To

objectify

In social philosophy, objectification is the act of treating a person, as an object or a thing. It is part of dehumanization, the act of disavowing the humanity of others. Sexual objectification, the act of treating a person as a mere object of sex ...

a culture as something different, exotic or underdeveloped is to generalize that it is not like 'normal' society. Europe's colonial attitude towards the Orientals exemplifies this as it was thought that the East was the opposite of the West; feminine where the West was masculine, weak where the West was strong and traditional where the West was progressive.

[Said, Edward. (1978) ''Orientalism''. New York: Pantheon Books. p. 357] By making these generalizations and othering the East, Europe was simultaneously defining herself as the norm, further entrenching the gap.

Much of the process of othering relies on imagined difference, or the expectation of difference. Spatial difference can be enough to conclude that "we" are "here" and the "others" are over "there".

Imagined differences serve to categorize people into groups and assign them characteristics that suit the imaginer's expectations.

Racial discrimination

Racial discrimination refers to

discrimination

Discrimination is the act of making unjustified distinctions between people based on the groups, classes, or other categories to which they belong or are perceived to belong. People may be discriminated on the basis of race, gender, age, relig ...

against someone on the basis of their race.

Racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of humans into

socially-constructed racial groups in daily life. It may apply to activities such as eating in a restaurant, drinking from a water fountain, using a bathroom, attending school, going to the movies, or in the rental or purchase of a home. Segregation is generally outlawed, but may exist through social norms, even when there is no strong individual preference for it, as suggested by

Thomas Schelling's models of segregation and subsequent work.

Supremacism

Centuries of

European colonialism

The historical phenomenon of colonization is one that stretches around the globe and across time. Ancient and medieval colonialism was practiced by the Phoenicians, the Greeks, the Turkish people, Turks, and the Arabs.

Colonialism in the mode ...

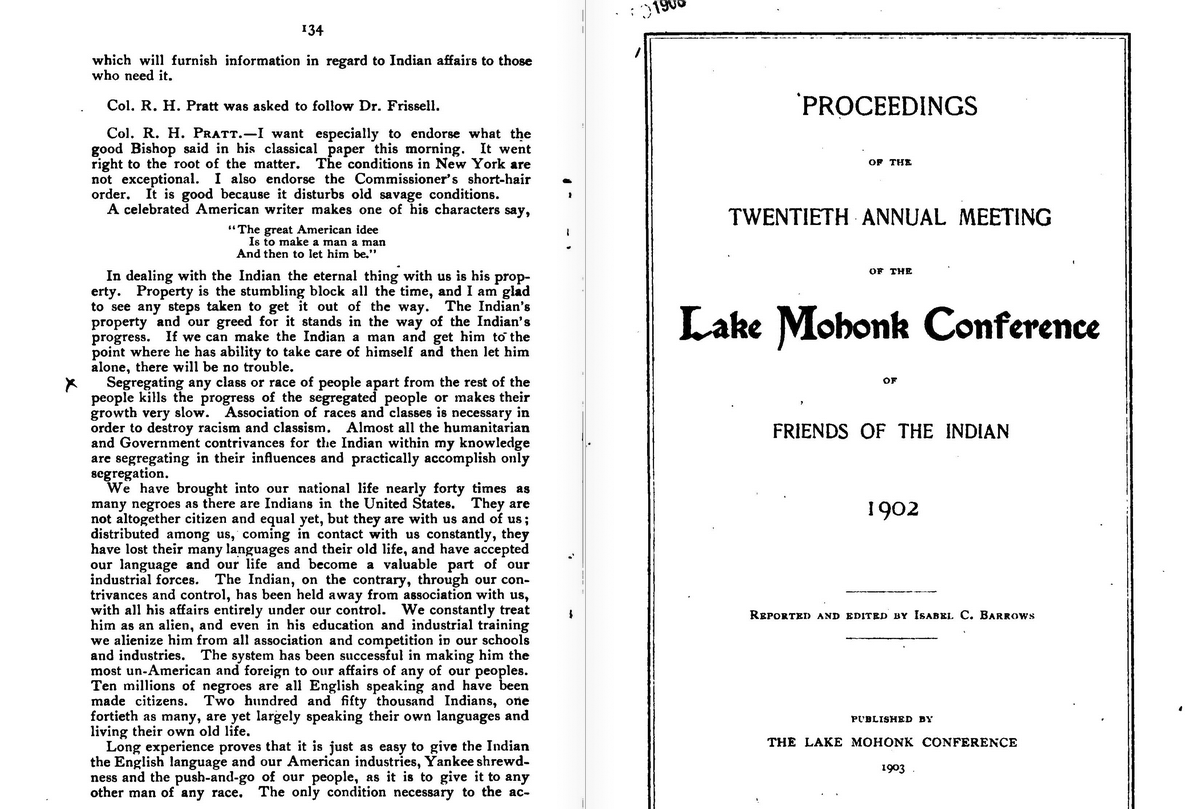

in the Americas, Africa and Asia were often justified by

white supremacist attitudes. During the early 20th century, the phrase "

The White Man's Burden" was widely used to justify an

imperialist policy as a noble enterprise. A justification for the policy of conquest and subjugation of

Native Americans emanated from the stereotyped perceptions of the indigenous people as "merciless Indian savages", as they are described in the

United States Declaration of Independence. Sam Wolfson of ''

The Guardian'' writes that "the declaration's passage has often been cited as an encapsulation of the

dehumanizing

Dehumanization is the denial of full humanness in others and the cruelty and suffering that accompanies it. A practical definition refers to it as the viewing and treatment of other persons as though they lack the mental capacities that are c ...

attitude toward indigenous Americans that the US was founded on." In an 1890 article about colonial expansion onto Native American land, author

L. Frank Baum wrote: "The Whites, by law of conquest, by justice of civilization, are masters of the American continent, and the best safety of the frontier settlements will be secured by the total annihilation of the few remaining Indians." In his ''

Notes on the State of Virginia'', published in 1785,

Thomas Jefferson wrote: "blacks, whether originally a distinct race, or made distinct by time or circumstances, are inferior to the whites in the endowments of both body and mind." Attitudes of

black supremacy

Black supremacy or black supremacism is a racial supremacist belief which maintains that black people are superior to people of other races. In the 1960s, Martin Luther King Jr. said that a doctrine of black supremacy was as dangerous as white ...

,

Arab supremacy

Racism in the Arab world covers an array of forms of intolerance against non-Arabs and the expat majority of the Arab states of the Persian Gulf coming from ( Sri Lanka, Pakistan, India and Bangladesh) groups as well as Black, European, and Asian ...

, and

East Asian supremacy also exist.

Symbolic/modern

Some scholars argue that in the US, earlier violent and aggressive forms of racism have evolved into a more subtle form of prejudice in the late 20th century. This new form of racism is sometimes referred to as "modern racism" and it is characterized by outwardly acting unprejudiced while inwardly maintaining prejudiced attitudes, displaying subtle prejudiced behaviors such as actions informed by attributing qualities to others based on racial stereotypes, and evaluating the same behavior differently based on the race of the person being evaluated. This view is based on studies of prejudice and discriminatory behavior, where some people will act ambivalently towards black people, with positive reactions in certain, more public contexts, but more negative views and expressions in more private contexts. This ambivalence may also be visible for example in hiring decisions where job candidates that are otherwise positively evaluated may be unconsciously disfavored by employers in the final decision because of their race. Some scholars consider modern racism to be characterized by an explicit rejection of stereotypes, combined with resistance to changing structures of discrimination for reasons that are ostensibly non-racial, an ideology that considers opportunity at a purely individual basis denying the relevance of race in determining individual opportunities and the exhibition of indirect forms of micro-aggression toward and/or avoidance of people of other races.

Subconscious biases

Recent research has shown that individuals who consciously claim to reject racism may still exhibit race-based subconscious biases in their decision-making processes. While such "subconscious racial biases" do not fully fit the definition of racism, their impact can be similar, though typically less pronounced, not being explicit, conscious or deliberate.

International law and racial discrimination

In 1919, a

proposal

Proposal(s) or The Proposal may refer to:

* Proposal (business)

* Research proposal

* Proposal (marriage)

* Proposition, a proposal in logic and philosophy

Arts, entertainment, and media

* The Proposal (album), ''The Proposal'' (album)

Films

...

to include a racial equality provision in the

Covenant of the League of Nations was supported by a majority, but not adopted in the

Paris Peace Conference Agreements and declarations resulting from meetings in Paris include:

Listed by name

Paris Accords

may refer to:

* Paris Accords, the agreements reached at the end of the London and Paris Conferences in 1954 concerning the post-war status of Germ ...

in 1919. In 1943, Japan and its allies declared work for the abolition of racial discrimination to be their aim at the

Greater East Asia Conference. Article 1 of the 1945

UN Charter includes "promoting and encouraging respect for human rights and for fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race" as UN purpose.

In 1950,

UNESCO suggested in ''

The Race Question''—a statement signed by 21 scholars such as

Ashley Montagu,

Claude Lévi-Strauss,

Gunnar Myrdal,

Julian Huxley

Sir Julian Sorell Huxley (22 June 1887 – 14 February 1975) was an English evolutionary biologist, eugenicist, and internationalist. He was a proponent of natural selection, and a leading figure in the mid-twentieth century modern synthesis. ...

, etc.—to "drop the term ''race'' altogether and instead speak of

ethnic groups". The statement condemned

scientific racism theories that had played a role in

the Holocaust. It aimed both at debunking scientific racist theories, by popularizing modern knowledge concerning "the race question", and morally condemned racism as contrary to the philosophy of the

Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

and its assumption of

equal rights for all. Along with Myrdal's ''

An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy'' (1944), ''The Race Question'' influenced the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court

desegregation decision in ''

Brown v. Board of Education''.

["Toward a World without Evil: Alfred Métraux as UNESCO Anthropologist (1946–1962)"](_blank)

by Harald E.L. Prins

Harald E. L. Prins (born 1951) is a Dutch anthropologist, ethnohistorian, filmmaker, and human rights activist specialized in North and South America's indigenous peoples and cultures.

Biography

Harald Prins was born in the Netherlands and is a ...

, UNESCO Also, in 1950, the

European Convention on Human Rights was adopted, which was widely used on racial discrimination issues.

The United Nations use the definition of racial discrimination laid out in the ''

International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination'', adopted in 1966:

... any distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference based on race, color, descent, or national or ethnic origin that has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal footing, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural or any other field of public life. (Part 1 of Article 1 of the U.N. International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination)

In 2001, the

European Union explicitly banned racism, along with many other forms of social discrimination, in the

Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, the legal effect of which, if any, would necessarily be limited to

Institutions of the European Union

The institutions of the European Union are the seven principal decision-making bodies of the European Union and the Euratom. They are, as listed in Article 13 of the Treaty on European Union:

* the European Parliament,

* the European Counci ...

: "Article 21 of the charter prohibits discrimination on any ground such as race, color, ethnic or social origin, genetic features, language, religion or belief, political or any other opinion, membership of a national minority, property, disability, age or sexual orientation and also discrimination on the grounds of nationality."

Ideology

Racism existed during the 19th century as "

scientific racism", which attempted to provide a

racial classification of humanity. In 1775

Johann Blumenbach divided the world's population into five groups according to skin color (Caucasians, Mongols, etc.), positing the view that the non-Caucasians had arisen through a process of degeneration. Another early view in scientific racism was the

polygenist view, which held that the different races had been separately created. Polygenist

Christoph Meiners for example, split mankind into two divisions which he labeled the "beautiful White race" and the "ugly Black race". In Meiners' book, ''The Outline of History of Mankind'', he claimed that a main characteristic of race is either beauty or ugliness. He viewed only the white race as beautiful. He considered ugly races to be inferior, immoral and animal-like.

Anders Retzius demonstrated that neither Europeans nor others are one "pure race", but of mixed origins. While

discredited, derivations of Blumenbach's taxonomy are

still widely used for the classification of the population in the United States.

Hans Peder Steensby

Hans Peder Steensby (25 March 1875, Steensby, Skamby Sogn, Funen Island – 20 October 1920, aboard ship Frederik VIII) was an ethnographer, geographer and professor at the University of Copenhagen.H. P. Steensby: Racestudier i Danmark' (PDF; 1,22 ...

, while strongly emphasizing that all humans today are of mixed origins, in 1907 claimed that the origins of human differences must be traced extraordinarily far back in time, and conjectured that the "purest race" today would be the

Australian Aboriginals.

Scientific racism fell strongly out of favor in the early 20th century, but the origins of fundamental human and societal differences are still researched within

academia, in fields such as

human genetics including

paleogenetics,

social anthropology

Social anthropology is the study of patterns of behaviour in human societies and cultures. It is the dominant constituent of anthropology throughout the United Kingdom and much of Europe, where it is distinguished from cultural anthropology. In t ...

,

comparative politics,

history of religions,

history of ideas,

prehistory,

history,

ethics, and

psychiatry. There is widespread rejection of any methodology based on anything similar to Blumenbach's races. It is more unclear to which extent and when

ethnic and national

stereotypes are accepted.

Although after

World War II and

the Holocaust, racist ideologies were discredited on ethical, political and scientific grounds, racism and

racial discrimination have remained widespread around the world.

Du Bois observed that it is not so much "race" that we think about, but culture: "... a common history, common laws and religion, similar habits of thought and a conscious striving together for certain ideals of life". Late 19th century nationalists were the first to embrace contemporary discourses on "race", ethnicity, and "

survival of the fittest

"Survival of the fittest" is a phrase that originated from Darwinian evolutionary theory as a way of describing the mechanism of natural selection. The biological concept of fitness is defined as reproductive success. In Darwinian terms, th ...

" to shape new nationalist doctrines. Ultimately, race came to represent not only the most important traits of the human body, but was also regarded as decisively shaping the character and personality of the nation. According to this view, culture is the physical manifestation created by ethnic groupings, as such fully determined by racial characteristics. Culture and race became considered intertwined and dependent upon each other, sometimes even to the extent of including nationality or language to the set of definition. Pureness of race tended to be related to rather superficial characteristics that were easily addressed and advertised, such as blondness. Racial qualities tended to be related to nationality and language rather than the actual geographic distribution of racial characteristics. In the case of

Nordicism, the denomination "

Germanic" was equivalent to superiority of race.

Bolstered by some

nationalist and

ethnocentric values and achievements of choice, this concept of racial superiority evolved to distinguish from other cultures that were considered inferior or impure. This emphasis on culture corresponds to the modern mainstream definition of racism: "

cism does not originate from the existence of 'races'. It ''creates'' them through a process of social division into categories: anybody can be racialised, independently of their somatic, cultural, religious differences."

This definition explicitly ignores the biological concept of race, which is still subject to scientific debate. In the words of

David C. Rowe

David C. Rowe (27 September 1949 – 2 February 2003) was an American psychology professor known for his work studying genetic and environmental influences on adolescent onset behaviors such as delinquency and smoking.J. L. Rodgers, K. Jacobs ...

, "

racial concept, although sometimes in the guise of another name, will remain in use in biology and in other fields because scientists, as well as lay persons, are fascinated by human diversity, some of which is captured by race."

Racial prejudice became subject to international legislation. For instance, the

Declaration on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on November 20, 1963, addresses racial prejudice explicitly next to discrimination for reasons of race, colour or ethnic origin (Article I).

Ethnicity and ethnic conflicts

Debates over the origins of racism often suffer from a lack of clarity over the term. Many use the term "racism" to refer to more general phenomena, such as

xenophobia and

ethnocentrism

Ethnocentrism in social science and anthropology—as well as in colloquial English discourse—means to apply one's own culture or ethnicity as a frame of reference to judge other cultures, practices, behaviors, beliefs, and people, instead of ...

, although scholars attempt to clearly distinguish those phenomena from racism as an

ideology

An ideology is a set of beliefs or philosophies attributed to a person or group of persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely epistemic, in which "practical elements are as prominent as theoretical ones." Formerly applied pri ...

or from scientific racism, which has little to do with ordinary xenophobia. Others conflate recent forms of racism with earlier forms of ethnic and national conflict. In most cases, ethno-national conflict seems to owe itself to conflict over land and strategic resources. In some cases,

ethnicity

An ethnic group or an ethnicity is a grouping of people who identify with each other on the basis of shared attributes that distinguish them from other groups. Those attributes can include common sets of traditions, ancestry, language, history, ...

and

nationalism were harnessed in order to rally

combatant

Combatant is the legal status of an individual who has the right to engage in hostilities during an armed conflict. The legal definition of "combatant" is found at article 43(2) of Additional Protocol I (AP1) to the Geneva Conventions of 1949. It ...

s in wars between great religious empires (for example, the Muslim Turks and the Catholic Austro-Hungarians).

Notions of race and racism have often played central roles in

ethnic conflict

An ethnic conflict is a conflict between two or more contending ethnic groups. While the source of the conflict may be political, social, economic or religious, the individuals in conflict must expressly fight for their ethnic group's positi ...

s. Throughout history, when an adversary is identified as "other" based on notions of race or ethnicity (in particular when "other" is interpreted to mean "inferior"), the means employed by the self-presumed "superior" party to appropriate territory, human chattel, or material wealth often have been more ruthless, more brutal, and less constrained by

moral

A moral (from Latin ''morālis'') is a message that is conveyed or a lesson to be learned from a story or event. The moral may be left to the hearer, reader, or viewer to determine for themselves, or may be explicitly encapsulated in a maxim. A ...

or

ethical considerations. According to historian Daniel Richter,

Pontiac's Rebellion saw the emergence on both sides of the conflict of "the novel idea that all Native people were 'Indians,' that all Euro-Americans were 'Whites,' and that all on one side must unite to destroy the other".

Basil Davidson

Basil Risbridger Davidson (9 November 1914 – 9 July 2010) was a British journalist and historian who wrote more than 30 books on African history and politics. According to two modern writers, "Davidson, a campaigning journalist whose fir ...

states in his documentary, ''Africa: Different but Equal'', that racism, in fact, only just recently surfaced as late as the 19th century, due to the need for a justification for slavery in the Americas.

Historically, racism was a major driving force behind the

Transatlantic slave trade. It was also a major force behind

racial segregation, especially in the

United States in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and South Africa under

apartheid; 19th and 20th century racism in the

Western world is particularly well documented and constitutes a reference point in studies and discourses about racism.

Racism has played a role in

genocides such as the

Armenian genocide, and the

Holocaust, and colonial projects like the European

colonization of the Americas,

Africa, and

Asia.

Indigenous peoples have been—and are—often subject to racist attitudes. Practices and ideologies of racism are condemned by the United Nations in the

Declaration of Human Rights.

Ethnic and racial nationalism

After the

Napoleonic Wars, Europe was confronted with the new "

nationalities question", leading to reconfigurations of the European map, on which the frontiers between the states had been delineated during the 1648

Peace of Westphalia

The Peace of Westphalia (german: Westfälischer Friede, ) is the collective name for two peace treaties signed in October 1648 in the Westphalian cities of Osnabrück and Münster. They ended the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) and brought pea ...

.

Nationalism had made its first appearance with the invention of the ''

levée en masse

''Levée en masse'' ( or, in English, "mass levy") is a French term used for a policy of mass national conscription, often in the face of invasion.

The concept originated during the French Revolutionary Wars, particularly for the period followi ...

'' by the

French Revolutionaries, thus inventing mass

conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

in order to be able to defend the newly founded

Republic

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

against the ''

Ancien Régime

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for "ancient, old"

** Société des anciens textes français

* the French for "former, senior"

** Virelai ancien

** Ancien Régime

** Ancien Régime in France

{{disambig ...

'' order represented by the European monarchies. This led to the

French Revolutionary Wars (1792–1802) and then to the conquests of

Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

, and to the subsequent European-wide debates on the concepts and realities of

nations, and in particular of

nation-state

A nation state is a political unit where the state and nation are congruent. It is a more precise concept than "country", since a country does not need to have a predominant ethnic group.

A nation, in the sense of a common ethnicity, may inc ...

s. The

Westphalia Treaty

The Peace of Westphalia (german: Westfälischer Friede, ) is the collective name for two peace treaties signed in October 1648 in the Westphalian cities of Osnabrück and Münster. They ended the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) and brought pea ...

had divided Europe into various empires and kingdoms (such as the

Ottoman Empire, the

Holy Roman Empire, the

Swedish Empire, the

Kingdom of France, etc.), and for centuries wars were waged between princes (''

Kabinettskriege'' in German).

Modern

nation-state

A nation state is a political unit where the state and nation are congruent. It is a more precise concept than "country", since a country does not need to have a predominant ethnic group.

A nation, in the sense of a common ethnicity, may inc ...

s appeared in the wake of the French Revolution, with the formation of

patriotic sentiments for the first time in

Spain during the

Peninsula War (1808–1813, known in Spain as the Independence War). Despite the restoration of the previous order with the 1815

Congress of Vienna, the "nationalities question" became the main problem of Europe during the

Industrial Era, leading in particular to the

1848 Revolutions

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europe ...

, the

Italian unification

The unification of Italy ( it, Unità d'Italia ), also known as the ''Risorgimento'' (, ; ), was the 19th-century political and social movement that resulted in the consolidation of different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single ...

completed during the 1871

Franco-Prussian War, which itself culminated in the proclamation of the

German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

in the Hall of Mirrors in the

Palace of Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; french: Château de Versailles ) is a former royal residence built by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, Yvelines, Versailles, about west of Paris, France. The palace is owned by the French Republic and since 19 ...

, thus achieving the

German unification.

Meanwhile, the

Ottoman Empire, the "

sick man of Europe", was confronted with endless nationalist movements, which, along with the dissolving of the

Austrian-Hungarian Empire

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1 ...

, would lead to the creation, after

World War I, of the various nation-states of the

Balkan

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

s, with "national

minorities" in their borders.

Ethnic nationalism, which advocated the belief in a hereditary membership of the nation, made its appearance in the historical context surrounding the creation of the modern nation-states.

One of its main influences was the

Romantic nationalist movement at the turn of the 19th century, represented by figures such as

Johann Herder

Johann Gottfried von Herder ( , ; 25 August 174418 December 1803) was a German philosopher, theologian, poet, and literary critic. He is associated with the Enlightenment, ''Sturm und Drang'', and Weimar Classicism.

Biography

Born in Mohrun ...

(1744–1803),

Johan Fichte (1762–1814) in the ''Addresses to the German Nation'' (1808),

Friedrich Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (; ; 27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a German philosopher. He is one of the most important figures in German idealism and one of the founding figures of modern Western philosophy. His influence extends ...

(1770–1831), or also, in France,

Jules Michelet

Jules Michelet (; 21 August 1798 – 9 February 1874) was a French historian and an author on other topics whose major work was a history of France and its culture. His aphoristic style emphasized his anti-clerical republicanism.

In Michelet's ...

(1798–1874). It was opposed to

liberal nationalism, represented by authors such as

Ernest Renan

Joseph Ernest Renan (; 27 February 18232 October 1892) was a French Orientalist and Semitic scholar, expert of Semitic languages and civilizations, historian of religion, philologist, philosopher, biblical scholar, and critic. He wrote influe ...

(1823–1892), who conceived of the nation as a community, which, instead of being based on the ''

Volk'' ethnic group and on a specific, common language, was founded on the subjective will to live together ("the nation is a daily

plebiscite", 1882) or also

John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, Member of Parliament (MP) and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of classical liberalism, he contributed widely to ...

(1806–1873).

Ethnic nationalism blended with scientific racist discourses, as well as with "continental

imperialist" (

Hannah Arendt

Hannah Arendt (, , ; 14 October 1906 – 4 December 1975) was a political philosopher, author, and Holocaust survivor. She is widely considered to be one of the most influential political theorists of the 20th century.

Arendt was born ...

, 1951

Hannah Arendt

Hannah Arendt (, , ; 14 October 1906 – 4 December 1975) was a political philosopher, author, and Holocaust survivor. She is widely considered to be one of the most influential political theorists of the 20th century.

Arendt was born ...

, '' The Origins of Totalitarianism'' (1951)) discourses, for example in the

pan-Germanism

Pan-Germanism (german: Pangermanismus or '), also occasionally known as Pan-Germanicism, is a pan-nationalist political idea. Pan-Germanists originally sought to unify all the German-speaking people – and possibly also Germanic-speaking ...

discourses, which postulated the racial superiority of the German ''

Volk'' (people/folk). The

Pan-German League

The Pan-German League (german: Alldeutscher Verband) was a Pan-German nationalist organization which was officially founded in 1891, a year after the Zanzibar Treaty was signed.

Primarily dedicated to the German Question of the time, it held pos ...

(''Alldeutscher Verband''), created in 1891, promoted

German imperialism

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic and ...

and "

racial hygiene", and was opposed to intermarriage with

Jews. Another popular current, the ''

Völkisch movement

The ''Völkisch'' movement (german: Völkische Bewegung; alternative en, Folkist Movement) was a German ethno-nationalist movement active from the late 19th century through to the Nazi era, with remnants in the Federal Republic of Germany af ...

'', was also an important proponent of the German ethnic nationalist discourse, and it combined Pan-Germanism with modern

racial antisemitism. Members of the Völkisch movement, in particular the

Thule Society, would participate in the founding of the

German Workers' Party (DAP) in Munich in 1918, the predecessor of the

Nazi Party. Pan-Germanism played a decisive role in the

interwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days), the end of the World War I, First World War to the beginning of the World War II, Second World War. The in ...

of the 1920s–1930s.

These currents began to associate the idea of the nation with the biological concept of a "

master race" (often the "

Aryan race" or the "

Nordic race") issued from the scientific racist discourse. They conflated nationalities with ethnic groups, called "races", in a radical distinction from previous racial discourses that posited the existence of a "race struggle" inside the nation and the state itself. Furthermore, they believed that political boundaries should mirror these alleged racial and ethnic groups, thus justifying

ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, and religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making a region ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal, extermination, deportation or population transfer ...

, in order to achieve "racial purity" and also to achieve ethnic homogeneity in the nation-state.

Such racist discourses, combined with nationalism, were not, however, limited to pan-Germanism. In France, the transition from Republican liberal nationalism, to ethnic nationalism, which made nationalism a characteristic of

far-right movements in France, took place during the

Dreyfus Affair at the end of the 19th century. During several years, a nationwide crisis affected French society, concerning the alleged treason of

Alfred Dreyfus

Alfred Dreyfus ( , also , ; 9 October 1859 – 12 July 1935) was a French artillery officer of Jewish ancestry whose trial and conviction in 1894 on charges of treason became one of the most polarizing political dramas in modern French history. ...

, a French Jewish military officer. The country polarized itself into two opposite camps, one represented by

Émile Zola, who wrote ''

J'Accuse…!'' in defense of Alfred Dreyfus, and the other represented by the nationalist poet,

Maurice Barrès

Auguste-Maurice Barrès (; 19 August 1862 – 4 December 1923) was a French novelist, journalist and politician. Spending some time in Italy, he became a figure in French literature with the release of his work ''The Cult of the Self'' in 1888. ...

(1862–1923), one of the founders of the ethnic nationalist discourse in France. At the same time,

Charles Maurras (1868–1952), founder of the monarchist ''

Action française'' movement, theorized the "anti-France", composed of the "four confederate states of Protestants, Jews, Freemasons and foreigners" (his actual word for the latter being the pejorative ''

métèques

In ancient Greece, a metic (Ancient Greek: , : from , , indicating change, and , 'dwelling') was a foreign resident of Athens, one who did not have citizen rights in their Greek city-state (''polis'') of residence.

Origin

The history of foreign m ...

''). Indeed, to him the first three were all "internal foreigners", who threatened the ethnic unity of the

French people.

History

Ethnocentrism and proto-racism

Aristotle

Bernard Lewis has cited the

Greek philosopher Aristotle who, in his discussion of slavery, stated that while Greeks are free by nature, "

barbarian

A barbarian (or savage) is someone who is perceived to be either Civilization, uncivilized or primitive. The designation is usually applied as a generalization based on a popular stereotype; barbarians can be members of any nation judged by som ...

s" (non-Greeks) are slaves by nature, in that it is in their nature to be more willing to submit to a

despotic government.

Though Aristotle does not specify any particular races, he argues that people from nations outside Greece are more prone to the burden of slavery than those from

Greece. While Aristotle makes remarks about the most natural slaves being those with strong bodies and slave souls (unfit for rule, unintelligent) which would seem to imply a physical basis for discrimination, he also explicitly states that the right kind of souls and bodies do not always go together, implying that the greatest determinate for inferiority and natural slaves versus natural masters is the soul, not the body. This proto-racism is seen as an important precursor to modern racism by classicist

Benjamin Isaac

Benjamin Henri Isaac (Ben Isaac; he, בנימין איזק; born May 10, 1945) is the Fred and Helen Lessing Professor of Ancient History Emeritus at Tel Aviv University. He is a member of the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities and of the A ...

.

Such proto-racism and ethnocentrism must be looked at within context, because a modern understanding of racism based on hereditary inferiority (with modern racism based on

eugenics and scientific racism) was not yet developed and it is unclear whether Aristotle believed the natural inferiority of Barbarians was caused by environment and climate (like many of his contemporaries) or by birth.

Historian Dante A. Puzzo, in his discussion of Aristotle, racism, and the ancient world writes that:

Racism rests on two basic assumptions: that a correlation exists between physical characteristics and moral qualities; that mankind is divisible into superior and inferior stocks. Racism, thus defined, is a modern conception, for prior to the XVIth century there was virtually nothing in the life and thought of the West that can be described as racist. To prevent misunderstanding a clear distinction must be made between racism and ethnocentrism

Ethnocentrism in social science and anthropology—as well as in colloquial English discourse—means to apply one's own culture or ethnicity as a frame of reference to judge other cultures, practices, behaviors, beliefs, and people, instead of ...

... The Ancient Hebrews, in referring to all who were not Hebrews as Gentiles, were indulging in ethnocentrism, not in racism. ... So it was with the Hellenes who denominated all non-Hellenes—whether the wild Scythians or the Egyptians

Egyptians ( arz, المَصرِيُون, translit=al-Maṣriyyūn, ; arz, المَصرِيِين, translit=al-Maṣriyyīn, ; cop, ⲣⲉⲙⲛ̀ⲭⲏⲙⲓ, remenkhēmi) are an ethnic group native to the Nile, Nile Valley in Egypt. Egyptian ...

whom they acknowledged as their mentors in the arts of civilization—Barbarians, the term denoting that which was strange or foreign.

Medieval Arab writers

Bernard Lewis has also cited historians and geographers of the

Middle East and North Africa region,

including

Al-Muqaddasi

Shams al-Dīn Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad ibn Abī Bakr al-Maqdisī ( ar, شَمْس ٱلدِّيْن أَبُو عَبْد ٱلله مُحَمَّد ابْن أَحْمَد ابْن أَبِي بَكْر ٱلْمَقْدِسِي), ...

,

Al-Jahiz,

Al-Masudi,

Abu Rayhan Biruni,

Nasir al-Din al-Tusi

Muhammad ibn Muhammad ibn al-Hasan al-Tūsī ( fa, محمد ابن محمد ابن حسن طوسی 18 February 1201 – 26 June 1274), better known as Nasir al-Din al-Tusi ( fa, نصیر الدین طوسی, links=no; or simply Tusi in the West ...

, and

Ibn Qutaybah.

Though the

Qur'an expresses no racial prejudice, Lewis argues that ethnocentric prejudice later developed among

Arabs, for a variety of reasons:

their

extensive conquests and

slave trade; the influence of

Aristotelian ideas regarding slavery, which some

Muslim philosophers

Muslim philosophers both profess Islam and engage in a style of philosophy situated within the structure of the Arabic language and Islam, though not necessarily concerned with religious issues. The sayings of the companions of Muhammad contained ...

directed towards

Zanj (

Bantu

Bantu may refer to:

*Bantu languages, constitute the largest sub-branch of the Niger–Congo languages

*Bantu peoples, over 400 peoples of Africa speaking a Bantu language

*Bantu knots, a type of African hairstyle

*Black Association for Nationali ...

) and

Turkic peoples;

and the influence of

Judeo-Christian

The term Judeo-Christian is used to group Christianity and Judaism together, either in reference to Christianity's derivation from Judaism, Christianity's borrowing of Jewish Scripture to constitute the "Old Testament" of the Christian Bible, or ...

ideas regarding divisions among humankind. By the eighth century, anti-black prejudice among Arabs resulted in discrimination. A number of medieval Arabic authors argued against this prejudice, urging respect for all black people and especially

Ethiopians. By the 14th century, a significant number of slaves came from

sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is, geographically, the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lies south of the Sahara. These include West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, and Southern Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the List of sov ...

; Lewis argues that this led to the likes of Egyptian historian Al-Abshibi (1388–1446) writing that "

is said that when the

lackslave is sated, he fornicates, when he is hungry, he steals." According to Lewis, the 14th-century Tunisian scholar

Ibn Khaldun

Ibn Khaldun (; ar, أبو زيد عبد الرحمن بن محمد بن خلدون الحضرمي, ; 27 May 1332 – 17 March 1406, 732-808 AH) was an Arab

The Historical Muhammad', Irving M. Zeitlin, (Polity Press, 2007), p. 21; "It is, of ...

also wrote:

...beyond nown peoples of black West Africa

A noun () is a word that generally functions as the name of a specific object or set of objects, such as living creatures, places, actions, qualities, states of existence, or ideas.Example nouns for:

* Living creatures (including people, alive, d ...

to the south there is no civilization in the proper sense. There are only humans who are closer to dumb animals than to rational beings. They live in thickets and caves, and eat herbs and unprepared grain. They frequently eat each other. They cannot be considered human beings. Therefore, the Negro nations are, as a rule, submissive to slavery, because (Negroes) have little that is (essentially) human and possess attributes that are quite similar to those of dumb animals, as we have stated.

According to

Wesleyan University professor Abdelmajid Hannoum, French

Orientalists projected racist and

colonialist views of the 19th century into their translations of medieval Arabic writings, including those of Ibn Khaldun. This resulted in the translated texts

racializing Arabs and

Berber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913–196 ...

people, when no such distinction was made in the originals. James E. Lindsay argues that the concept of an

Arab identity itself did not exist until modern times, though others like

Robert Hoyland

Robert G. Hoyland (born 1966) is a historian, specializing in the medieval history of the Middle East. He is a former student of historian Patricia Crone and was a Leverhulme Fellow at Pembroke College, Oxford. He is currently Professor of Late ...

have argued that a common sense of

Arab identity already existed by the 9th century.

''Limpieza de sangre''

With the

Umayyad Caliphate's conquest of Hispania, Muslim Arabs and

Berbers

, image = File:Berber_flag.svg

, caption = The Berber ethnic flag

, population = 36 million

, region1 = Morocco

, pop1 = 14 million to 18 million

, region2 = Algeria

, pop2 ...

overthrew the previous

Visigothic rulers and created

Al-Andalus, which contributed to the

Golden age of Jewish culture, and lasted for six centuries. It was followed by the centuries-long ''

Reconquista'', during which Christian Iberian kingdoms contested Al-Andalus and progressively conquered the divided Muslim kingdoms, culminating in the

fall of the Nasrid kingdom of Granada in 1492 and the rise of

Ferdinand V Ferdinand V is the name of:

* Ferdinand II of Aragon, Ferdinand V of Castile, ''the Catholic'' king of Castile, Aragon and Naples

*Ferdinand I of Austria

en, Ferdinand Charles Leopold Joseph Francis Marcelin

, image = Kaiser Ferdinand I.j ...

and

Isabella I as

Catholic monarchs of Spain. The legacy Catholic

Spaniards