Ra'īmâ on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sargon II (

The

The

Sargon II was the first king in more than a thousand years to bear the name Sargon. There were two Mesopotamian kings of the same name before his reign:

Sargon II was the first king in more than a thousand years to bear the name Sargon. There were two Mesopotamian kings of the same name before his reign:

Sargon's reign began with large-scale resistance against his rule in Assyria's heartland. Although quickly suppressed, this political instability led several peripheral regions to regain independence. In early 721,

Sargon's reign began with large-scale resistance against his rule in Assyria's heartland. Although quickly suppressed, this political instability led several peripheral regions to regain independence. In early 721,

Neo-Assyrian cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo-syllabic script that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Middle East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. It is named for the characteristic wedge-sha ...

: , meaning "the faithful king" or "the legitimate king") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history and the final and greatest phase of Assyria as an independent state. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew t ...

from 722 BC to his death in battle in 705. Probably the son of Tiglath-Pileser III

Tiglath-Pileser III (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning "my trust belongs to the son of Ešarra"), was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 745 BC to his death in 727. One of the most prominent and historically significant Assyrian kings, Tig ...

(745–727), Sargon is generally believed to have become king after overthrowing Shalmaneser V

Shalmaneser V (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning "Salmānu is foremost"; Biblical Hebrew: ) was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Tiglath-Pileser III in 727 BC to his deposition and death in 722 BC. Though Shalman ...

(727–722), probably his brother. He is typically considered the founder of a new dynastic line, the Sargonid dynasty

The Sargonid dynasty was the final ruling dynasty of Assyria, ruling as kings of Assyria during the Neo-Assyrian Empire for just over a century from the ascent of Sargon II in 722 BC to the fall of Assyria in 609 BC. Although Assyria would ult ...

.

Modelling his reign on the legends of the ancient rulers Sargon of Akkad

Sargon of Akkad (; akk, ''Šarrugi''), also known as Sargon the Great, was the first ruler of the Akkadian Empire, known for his conquests of the Sumerian city-states in the 24th to 23rd centuries BC.The date of the reign of Sargon is highl ...

, from whom Sargon II likely took his regnal name, and Gilgamesh

sux, , label=none

, image = Hero lion Dur-Sharrukin Louvre AO19862.jpg

, alt =

, caption = Possible representation of Gilgamesh as Master of Animals, grasping a lion in his left arm and snake in his right hand, in an Assyr ...

, Sargon aspired to conquer the known world, initiate a golden age

The term Golden Age comes from Greek mythology, particularly the ''Works and Days'' of Hesiod, and is part of the description of temporal decline of the state of peoples through five Ages of Man, Ages, Gold being the first and the one during ...

and a new world order, and be remembered and revered by future generations. Over the course of his seventeen-year reign, Sargon substantially expanded Assyrian territory and enacted important political and military reforms. An accomplished warrior-king and military strategist

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

, Sargon personally led his troops into battle. By the end of his reign, all of his major enemies and rivals had been either defeated or pacified. Among Sargon's greatest accomplishments were the stabilization of Assyrian control over the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

, the weakening of the northern kingdom of Urartu

Urartu (; Assyrian: ',Eberhard Schrader, ''The Cuneiform inscriptions and the Old Testament'' (1885), p. 65. Babylonian: ''Urashtu'', he, אֲרָרָט ''Ararat'') is a geographical region and Iron Age kingdom also known as the Kingdom of Va ...

, and the reconquest of Babylonia

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state c. ...

. From 717 to 707, Sargon constructed a new Assyrian capital named after himself, Dur-Sharrukin

Dur-Sharrukin ("Fortress of Sargon"; ar, دور شروكين, Syriac: ܕܘܪ ܫܪܘ ܘܟܢ), present day Khorsabad, was the Assyrian capital in the time of Sargon II of Assyria. Khorsabad is a village in northern Iraq, 15 km northeast of Mo ...

('Fort Sargon'), which he made his official residence in 706.

Sargon considered himself to have been divinely mandated to maintain and ensure justice. Like other Assyrian kings, Sargon at times enacted brutal punishments against his enemies but there are no known cases of atrocities against civilians from his reign. He worked to assimilate and integrate conquered foreign peoples into the empire and extended the same rights and obligations to them as native Assyrians. He forgave defeated enemies on several occasions and maintained good relations with foreign kings and with the ruling classes of the lands he conquered. Sargon also increased the influence and status of both women and scribes at the royal court.

Sargon embarked on his final campaign, against Tabal

Tabal (c.f. biblical ''Tubal''; Assyrian: 𒋫𒁄) was a Luwian speaking Neo-Hittite kingdom (and/or collection of kingdoms) of South Central Anatolia during the Iron Age. According to archaeologist Kurt Bittel, references to Tabal first appear ...

in Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

, in 705. He was killed in battle and the Assyrian army was unable to retrieve his body, preventing a traditional burial. According to ancient Mesopotamian religion

Mesopotamian religion refers to the religious beliefs and practices of the civilizations of ancient Mesopotamia, particularly Sumer, Akkad, Assyria and Babylonia between circa 6000 BC and 400 AD, after which they largely gave way to Syria ...

, he was cursed to remain a restless ghost for eternity. Sargon's fate was a major psychological blow for the Assyrians and damaged his legacy. Sargon's son Sennacherib

Sennacherib (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: or , meaning " Sîn has replaced the brothers") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Sargon II in 705BC to his own death in 681BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynast ...

was deeply disturbed by his father's death and believed that he must have committed some grave sin. As a result, Sennacherib distanced himself from Sargon. Sargon was barely mentioned in later ancient literature and nearly completely forgotten until the ruins of Dur-Sharrukin were discovered in the 19th century. He was not fully accepted

''Accepted'' is a 2006 American comedy film directed by Steve Pink (in his directorial debut) and written by Adam Cooper, Bill Collage and Mark Perez. The plot follows a group of high school graduates who create their own fake college after bein ...

in Assyriology

Assyriology (from Greek , ''Assyriā''; and , '' -logia'') is the archaeological, anthropological, and linguistic study of Assyria and the rest of ancient Mesopotamia (a region that encompassed what is now modern Iraq, northeastern Syria, southea ...

as a real king until the 1860s. Due to his conquests and reforms, Sargon is today considered one of the most important Assyrian kings.

Background

Ancestry and rise to the throne

Nothing is known of Sargon II's life before he became king. He was probably born 770 BC and cannot have been born later than 760 BC. His reign was immediately preceded by those ofTiglath-Pileser III

Tiglath-Pileser III (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning "my trust belongs to the son of Ešarra"), was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 745 BC to his death in 727. One of the most prominent and historically significant Assyrian kings, Tig ...

(745–727) and Tiglath-Pileser's son Shalmaneser V

Shalmaneser V (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning "Salmānu is foremost"; Biblical Hebrew: ) was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Tiglath-Pileser III in 727 BC to his deposition and death in 722 BC. Though Shalman ...

(727–722). Although Sargon is generally regarded as the founder of a new dynastic line, the Sargonid dynasty

The Sargonid dynasty was the final ruling dynasty of Assyria, ruling as kings of Assyria during the Neo-Assyrian Empire for just over a century from the ascent of Sargon II in 722 BC to the fall of Assyria in 609 BC. Although Assyria would ult ...

, he was probably a scion of the incumbent Adaside dynasty. Sargon grew up during the reigns of Ashur-dan III

Ashur-dan III (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning " Ashur is strong") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 773 BC to his death in 755 BC. Ashur-dan was a son of Adad-nirari III (811–783 BC) and succeeded his brother Shalmaneser IV as king ...

(773–755 BC) and Ashur-nirari V

Ashur-nirari V (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning " Ashur is my help") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 755 BC to his death in 745 BC. Ashur-nirari was a son of Adad-nirari III (811–783 BC) and succeeded his brother Ashur-dan III as ...

(755–745 BC), when rebellion and plague affected the Neo-Assyrian Empire

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history and the final and greatest phase of Assyria as an independent state. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew t ...

; the prestige and power of Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the A ...

dramatically declined. This trend reversed during the tenure of Tiglath-Pileser, who reduced the influence of powerful officials, reformed the army and more than doubled the size of the empire. In contrast to Tiglath-Pileser, little is recorded of Shalmaneser's brief reign.

Whereas kings typically elaborated on their origin in inscriptions, Sargon stated that the Assyrian national deity Ashur Ashur, Assur, or Asur may refer to:

Places

* Assur, an Assyrian city and first capital of ancient Assyria

* Ashur, Iran, a village in Iran

* Asur, Thanjavur district, a village in the Kumbakonam taluk of Thanjavur district, Tamil Nadu, India

* Assu ...

had called him to the throne. Sargon mentioned his origin in just two known inscriptions, where he referred to himself as Tiglath-Pileser's son, and in the Borowski Stele

Borowski (; feminine: Borowska; plural: Borowscy) is a surname of Polish-language origin.

People

* Dorota Borowska (born 1996), Polish canoeist

*Edmund Borowski (born 1945), Polish athlete

*Elie Borowski (1913–2003), Jewish art dealer and co ...

, probably from Hama

, timezone = EET

, utc_offset = +2

, timezone_DST = EEST

, utc_offset_DST = +3

, postal_code_type =

, postal_code =

, ar ...

in Syria, which referenced his "royal fathers". Most historians cautiously accept that Sargon was Tiglath-Pileser's son but not the legitimate heir to the throne as the next-in-line after Shalmaneser. If Sargon was Tiglath-Pileser's son, his mother might have been the queen Iaba. Some Assyriologists, such as Natalie Naomi May, have suggested that Sargon was a member of a collateral branch of the Adaside dynasty from the western part of the empire. In Babylonia

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state c. ...

, Sargon and his successors were considered part of the "dynasty of Hanigalbat

Mitanni (; Hittite cuneiform ; ''Mittani'' '), c. 1550–1260 BC, earlier called Ḫabigalbat in old Babylonian texts, c. 1600 BC; Hanigalbat or Hani-Rabbat (''Hanikalbat'', ''Khanigalbat'', cuneiform ') in Assyrian records, or ''Naharin'' in ...

" (a western territory), while earlier Assyrian kings were considered part of the "dynasty of Baltil" (Baltil being the name of the oldest portion of the ancient Assyrian capital of Assur

Aššur (; Sumerian: AN.ŠAR2KI, Assyrian cuneiform: ''Aš-šurKI'', "City of God Aššur"; syr, ܐܫܘܪ ''Āšūr''; Old Persian ''Aθur'', fa, آشور: ''Āšūr''; he, אַשּׁוּר, ', ar, اشور), also known as Ashur and Qal'a ...

). Perhaps Sargon was connected to a junior branch of the royal dynasty established at Hanigalbat centuries earlier. Some Assyriologists, such as John Anthony Brinkman, believe that Sargon did not belong to the direct dynastic lineage.

The

The Babylonian Chronicles

The Babylonian Chronicles are a series of tablets recording major events in Babylonian history. They are thus one of the first steps in the development of ancient historiography. The Babylonian Chronicles were written in Babylonian cuneiform, fr ...

report that Shalmaneser died in January 722 and was succeeded in the same month by Sargon, who was between forty and fifty years old. The exact events surrounding his accession are not clear. Some historians such as Josette Elayi

Josette Elayi-Escaich (; born 29 March 1943) is a French antiquity historian, Phoenician and Near-Eastern history specialist, and honorary scholar at the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS). Elayi authored numerous archaeology ...

believe that Sargon legitimately inherited the throne. Most scholars however believe him to have been a usurper; one theory is that Sargon killed Shalmaneser and seized the throne in a palace coup

A palace is a grand residence, especially a royal residence, or the home of a head of state or some other high-ranking dignitary, such as a bishop or archbishop. The word is derived from the Latin name palātium, for Palatine Hill in Rome whic ...

. Sargon rarely referenced his predecessors and, upon accession, faced massive domestic opposition. Shalmaneser probably had sons of his own who could have inherited the throne, such as the palace official Ashur-dain-aplu, who retained a prominent position under the Sargonid kings. Sargon's only known reference to Shalmaneser describes Ashur punishing him for his policies:

Sargon did not otherwise hold Shalmaneser responsible for the policies placed on Assur, since he wrote elsewhere that most of these had been enacted in the distant past. Tiglath-Pileser, not Shalmaneser, imposed forced labor on the residents of Assur. Several of Shalmaneser's policies and acts were revoked by Sargon. Hullî, a king in Tabal

Tabal (c.f. biblical ''Tubal''; Assyrian: 𒋫𒁄) was a Luwian speaking Neo-Hittite kingdom (and/or collection of kingdoms) of South Central Anatolia during the Iron Age. According to archaeologist Kurt Bittel, references to Tabal first appear ...

(a region in Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

) deported by Shalmaneser, was reinstalled and Sargon reversed Shalmaneser's attempt to decrease trade with Egypt.

Name

Sargon II was the first king in more than a thousand years to bear the name Sargon. There were two Mesopotamian kings of the same name before his reign:

Sargon II was the first king in more than a thousand years to bear the name Sargon. There were two Mesopotamian kings of the same name before his reign: Sargon I

Sargon I (also transcribed as Šarru-kīn I and Sharru-ken I) was the king (Išši’ak Aššur, "Steward of Assur") during the Old Assyrian period from 1920 BC to 1881 BC. On the Assyrian King List, Sargon appears as the son and successor of Iku ...

, a minor Assyrian king of the 19th century BC (after whom Sargon II is enumerated by modern historians), and the far more prominent 24th–23rd century BC Sargon of Akkad

Sargon of Akkad (; akk, ''Šarrugi''), also known as Sargon the Great, was the first ruler of the Akkadian Empire, known for his conquests of the Sumerian city-states in the 24th to 23rd centuries BC.The date of the reign of Sargon is highl ...

, conqueror of large parts of Mesopotamia and the founder of the Akkadian Empire

The Akkadian Empire () was the first ancient empire of Mesopotamia after the long-lived civilization of Sumer. It was centered in the city of Akkad (city), Akkad () and its surrounding region. The empire united Akkadian language, Akkadian and ...

. Sargon was probably an assumed regnal name

A regnal name, or regnant name or reign name, is the name used by monarchs and popes during their reigns and, subsequently, historically. Since ancient times, some monarchs have chosen to use a different name from their original name when they ac ...

. Royal names in ancient Mesopotamia were deliberate choices, setting the tone for a king's reign. Sargon most likely chose the name due to its use by Sargon of Akkad. In late Assyrian texts, the names of Sargon II and Sargon of Akkad are written with the same spelling. Sargon II is sometimes explicitly called the "second Sargon" (''Šarru-kīn arkû''). Though the precise extent of the ancient Sargon's conquests had been forgotten, the legendary ruler was still remembered as a "conqueror of the world". Sargon II also energetically pursued the expansion of his own empire.

In addition to the name's historical connections, Sargon connected his regnal name to justice. In several inscriptions, Sargon described his name as akin to a divine mandate to ensure that his people lived just lives, for instance in an inscription in which Sargon described how he reimbursed the owners of the land he chose to construct his new capital city of Dur-Sharrukin

Dur-Sharrukin ("Fortress of Sargon"; ar, دور شروكين, Syriac: ܕܘܪ ܫܪܘ ܘܟܢ), present day Khorsabad, was the Assyrian capital in the time of Sargon II of Assyria. Khorsabad is a village in northern Iraq, 15 km northeast of Mo ...

on:

The name was most commonly written ''Šarru-kīn'', although ''Šarru-ukīn'', is also attested. Sargon's name is commonly interpreted as "the faithful king" in the sense of righteousness and justice. Another alternative is that ''Šarru-kīn'' is a phonetic reproduction of the contracted pronunciation of ''Šarru-ukīn'' to ''Šarrukīn'', which means that it should be interpreted as "the king has obtained/established order", possibly referencing disorder either under his predecessor or caused by Sargon's usurpation. ''Šarru-kīn'' can also be interpreted as "the legitimate king" or "the true king" and it could have been chosen because Sargon was not the legitimate heir to the throne. The ancient Sargon of Akkad also became king through usurpation. The origin of the conventional modern version of the name, Sargon, is not entirely clear but it is probably based on the spelling in the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. Hebrew: ''Tān ...

(''srgwn'').

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. Hebrew: ''Tān ...

Reign

Early reign and rebellions

Sargon's reign began with large-scale resistance against his rule in Assyria's heartland. Although quickly suppressed, this political instability led several peripheral regions to regain independence. In early 721,

Sargon's reign began with large-scale resistance against his rule in Assyria's heartland. Although quickly suppressed, this political instability led several peripheral regions to regain independence. In early 721, Marduk-apla-iddina II

Marduk-apla-iddina II (Akkadian language, Akkadian: ; in the Bible Merodach-Baladan, also called Marduk-Baladan, Baladan and Berodach-Baladan, lit. ''Marduk has given me an heir'') was a Chaldean leader from the Bit-Yakin tribe, originally establi ...

, a Chaldean warlord of the Bit-Yakin tribe, captured Babylon

''Bābili(m)''

* sux, 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠

* arc, 𐡁𐡁𐡋 ''Bāḇel''

* syc, ܒܒܠ ''Bāḇel''

* grc-gre, Βαβυλών ''Babylṓn''

* he, בָּבֶל ''Bāvel''

* peo, 𐎲𐎠𐎲𐎡𐎽𐎢 ''Bābiru''

* elx, 𒀸𒁀𒉿𒇷 ''Babi ...

, restored Babylonian independence after eight years of Assyrian rule and allied with the eastern realm of Elam

Elam (; Linear Elamite: ''hatamti''; Cuneiform Elamite: ; Sumerian: ; Akkadian: ; he, עֵילָם ''ʿēlām''; peo, 𐎢𐎺𐎩 ''hūja'') was an ancient civilization centered in the far west and southwest of modern-day Iran, stretc ...

. Though Sargon considered Marduk-apla-iddina's seizure of Babylonia to be unacceptable, an attempt to defeat him in battle near Der in 720 was unsuccessful. At the same time, Yahu-Bihdi

Yahu-Bihdi (Akkadian: 𒅀𒌑𒁉𒀪𒁲 ''ia-ú-bi-ʾ-di'') also called Ilu-Bihdi (Akkadian: 𒀭𒁉𒀪𒁲 ''ìl-bi-ʾ-di'') was a governor of Hamath appointed by the Assyrian government. He declared himself king of Hamath in 720 BC and led ...

of Hama

, timezone = EET

, utc_offset = +2

, timezone_DST = EEST

, utc_offset_DST = +3

, postal_code_type =

, postal_code =

, ar ...

in Syria assembled a coalition of minor states in the northern Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

to oppose Assyrian dominion.

In addition to these revolts, Sargon may have had to deal with unfinished conflicts from Shalmaneser's reign. At some point in the 720s, the Assyrians captured Samaria

Samaria (; he, שֹׁמְרוֹן, translit=Šōmrōn, ar, السامرة, translit=as-Sāmirah) is the historic and biblical name used for the central region of Palestine, bordered by Judea to the south and Galilee to the north. The first- ...

after a siege lasting several years and ended the Kingdom of Israel. Sargon claimed to have conquered the city, but it is more likely that Shalmaneser captured the city since both the Babylonian Chronicles and the Hebrew Bible viewed the fall of Israel as the signature event of his reign. Sargon's claim to conquering it may be related to the city being captured again after Yahu-Bihdi's revolt. Either Shalmaneser or Sargon ordered the dispersal of Samaria's population across the Assyrian Empire, following the standard resettlement policy. This specific resettlement resulted in the loss of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel

The ten lost tribes were the ten of the Twelve Tribes of Israel that were said to have been exiled from the Kingdom of Israel after its conquest by the Neo-Assyrian Empire BCE. These are the tribes of Reuben, Simeon, Dan, Naphtali, Gad, Ash ...

. In his inscriptions, Sargon claimed to have resettled 27,280 Israelites. Though likely emotionally damaging for the resettled populace, the Assyrians valued deportees for their labor and generally treated them well, transporting them in safety and comfort together with their families and belongings.

Shortly after his failure to retake Babylonia from Marduk-apla-iddina in 720, Sargon campaigned against Yahu-Bihdi. Among Yahu-Bihdi's supporters were the cities of Arpad, Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

, Sumur and Samaria. Three of the cities participating in the revolt (Arpad, Sumur and Damascus) were not vassal states; their lands had been converted into Assyrian provinces governed by royally appointed Assyrian governors. The revolt threatened to undo the administrative system established in Syria by Sargon's predecessors and the insurgents went on a killing spree

A spree killer is someone who commits a criminal act that involves two or more murders or homicides in a short time, in multiple locations. The U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics defines a spree killing as "killings at two or more locations wit ...

, murdering all local Assyrians they could find.

Sargon engaged Yahu-Bihdi and his coalition at Qarqar

Qarqar or Karkar is the name of an ancient town in northwestern Syria, known from Neo-Assyrian sources. It was the site of one of the most important battles of the ancient world, the battle of Qarqar, fought in 853 BC when the army of Assyria, le ...

on the Orontes. Defeated, Yahu-Bihdi escaped into Qarqar, which Sargon besieged and captured. Sargon's army destroyed Qarqar and devastated the surrounding lands. Yahu-Bihdi was first deported to Assyria together with his family and then flayed alive. Hama and the other insurgent cities were annexed again. At the same time as large numbers of people from Syria were resettled in other parts of the empire, Sargon resettled some people to Syria, including 6,300 "guilty Assyrians", presumably Assyrians from the heartland who had fought against Sargon upon his accession but whose lives had been spared. Sargon described their resettlement as an act of mercy: "their transgression I disregarded, I had mercy on them".

Around the same time as Yahu-Bihdu, Hanunu

Hanunu ( Philistine: 𐤇𐤍𐤍 *''Ḥanūn''; Akkadian: 𒄩𒀀𒉡𒌑𒉡 ''ḫa-a-nu-ú-nu''),Gaza in the south also rebelled against Assyria. After Sargon had defeated Yahu-Bihdu, he marched south. After capturing some other cities on his way, probably including

Sargon returned to Syria in 717 to defeat an uprising led by Pisiri of

Sargon returned to Syria in 717 to defeat an uprising led by Pisiri of

Urartu remained Sargon's main strategic rival in the north. In 715, Urartu was severely weakened by an unsuccessful expedition against the

Urartu remained Sargon's main strategic rival in the north. In 715, Urartu was severely weakened by an unsuccessful expedition against the  Sargon left the Assyrian capital of

Sargon left the Assyrian capital of

The foundations of Dur-Sharrukin ("fortress of Sargon") were laid in 717. Dur-Sharrukin was built between the Husur river and Mount Musri, near the village of Magganabba, around northeast of

The foundations of Dur-Sharrukin ("fortress of Sargon") were laid in 717. Dur-Sharrukin was built between the Husur river and Mount Musri, near the village of Magganabba, around northeast of  The numerous surviving sources on the construction of the city include inscriptions carved on the walls of its buildings, reliefs depicting the process and over a hundred letters and other documents describing the work. The chief coordinator was Tab-shar-Ashur, Sargon's chief treasurer, but at least twenty-six governors from across the empire were also associated with the construction; Sargon made the project a collaborative effort by the whole empire. Sargon took an active personal interest in the progress and frequently intervened in nearly all aspects of the work, from commenting on architectural details to overseeing material transportation and the recruitment of labor. Sargon's frequent input and efforts to encourage more work is probably the main reason for how the city could be completed so fast and efficiently. Sargon's encouragement was at times lenient, particularly when dealing with grumbling among the workers, but at other times threatening. One of his letters to the governor of Nimrud, requesting building materials, reads as follows:

Dur-Sharrukin reflected Sargon's self-image and how he wished the empire to see him. At about three square kilometers (1.2 square miles), the city was one of the largest in antiquity. The city's palace, which Sargon called a "palace without rival", was built on a huge artificial platform on the northern side of the city and was fortified with a wall of its own. At 100,000 square meters (10 hectares; 25 acres), it was the largest Assyrian palace ever built. It was richly decorated with reliefs, statues, glazed bricks and stone ''

The numerous surviving sources on the construction of the city include inscriptions carved on the walls of its buildings, reliefs depicting the process and over a hundred letters and other documents describing the work. The chief coordinator was Tab-shar-Ashur, Sargon's chief treasurer, but at least twenty-six governors from across the empire were also associated with the construction; Sargon made the project a collaborative effort by the whole empire. Sargon took an active personal interest in the progress and frequently intervened in nearly all aspects of the work, from commenting on architectural details to overseeing material transportation and the recruitment of labor. Sargon's frequent input and efforts to encourage more work is probably the main reason for how the city could be completed so fast and efficiently. Sargon's encouragement was at times lenient, particularly when dealing with grumbling among the workers, but at other times threatening. One of his letters to the governor of Nimrud, requesting building materials, reads as follows:

Dur-Sharrukin reflected Sargon's self-image and how he wished the empire to see him. At about three square kilometers (1.2 square miles), the city was one of the largest in antiquity. The city's palace, which Sargon called a "palace without rival", was built on a huge artificial platform on the northern side of the city and was fortified with a wall of its own. At 100,000 square meters (10 hectares; 25 acres), it was the largest Assyrian palace ever built. It was richly decorated with reliefs, statues, glazed bricks and stone ''

In 710, Sargon decided to reconquer Babylonia. To justify the impending expedition, Sargon proclaimed that the Babylonian national deity

In 710, Sargon decided to reconquer Babylonia. To justify the impending expedition, Sargon proclaimed that the Babylonian national deity

After he took Babylon in 710, Sargon was proclaimed king of Babylon by the citizens of the city and spent the next three years in Babylon, in Marduk-apla-iddina's palace. Affairs in Assyria were in these years overseen by Sargon's son

After he took Babylon in 710, Sargon was proclaimed king of Babylon by the citizens of the city and spent the next three years in Babylon, in Marduk-apla-iddina's palace. Affairs in Assyria were in these years overseen by Sargon's son

Few sources survive describing Sargon's final campaign and death. Based on the Assyrian Eponym List and the Babylonian Chronicles, the most likely course of events is that Sargon embarked to campaign against Tabal, which had risen up against him, in the early summer of 705. This campaign was the last of several attempts to bring Tabal under Assyrian control. It is not clear why Sargon resolved to lead the expedition against Tabal in person, considering the large number of campaigns led by his officials and generals. Tabal was not a real threat against the Assyrian Empire. Elayi believes that the most likely explanation is that Sargon saw the expedition as an interesting diversion from the quiet court life of Dur-Sharrukin.

Sargon's final campaign ended in disaster. Somewhere in Anatolia, Gurdî of Kulumma, an otherwise poorly attested figure, attacked the Assyrian camp. Gurdî has variously been assumed to have been a local ruler in Anatolia or a tribal leader of the Cimmerians, during this time allied with the rebels in Tabal. In the ensuing battle, Sargon was killed. The Assyrian soldiers fleeing from the attack were unable to recover the king's body. Sargon died just over a year after the inauguration of Dur-Sharrukin.

Few sources survive describing Sargon's final campaign and death. Based on the Assyrian Eponym List and the Babylonian Chronicles, the most likely course of events is that Sargon embarked to campaign against Tabal, which had risen up against him, in the early summer of 705. This campaign was the last of several attempts to bring Tabal under Assyrian control. It is not clear why Sargon resolved to lead the expedition against Tabal in person, considering the large number of campaigns led by his officials and generals. Tabal was not a real threat against the Assyrian Empire. Elayi believes that the most likely explanation is that Sargon saw the expedition as an interesting diversion from the quiet court life of Dur-Sharrukin.

Sargon's final campaign ended in disaster. Somewhere in Anatolia, Gurdî of Kulumma, an otherwise poorly attested figure, attacked the Assyrian camp. Gurdî has variously been assumed to have been a local ruler in Anatolia or a tribal leader of the Cimmerians, during this time allied with the rebels in Tabal. In the ensuing battle, Sargon was killed. The Assyrian soldiers fleeing from the attack were unable to recover the king's body. Sargon died just over a year after the inauguration of Dur-Sharrukin.

Unlike the numerous records of such punishments against Assyrian enemies, there is no evidence that Sargon's threats were realized—it is unlikely that they ever were. Because the soldiers in many cases had themselves participated in punishments against their enemies, the threats themselves were probably sufficient. Despite this approach, Sargon was not unpopular with the military; there are no records of army uprisings against him, nor of any army officers engaging in conspiracies. It is also probable that the main motivating factor for Assyrians serving in the army was not being threatened by the king, but rather the frequent Looting, spoils of war that could be taken after victories.

Unlike the numerous records of such punishments against Assyrian enemies, there is no evidence that Sargon's threats were realized—it is unlikely that they ever were. Because the soldiers in many cases had themselves participated in punishments against their enemies, the threats themselves were probably sufficient. Despite this approach, Sargon was not unpopular with the military; there are no records of army uprisings against him, nor of any army officers engaging in conspiracies. It is also probable that the main motivating factor for Assyrians serving in the army was not being threatened by the king, but rather the frequent Looting, spoils of war that could be taken after victories.

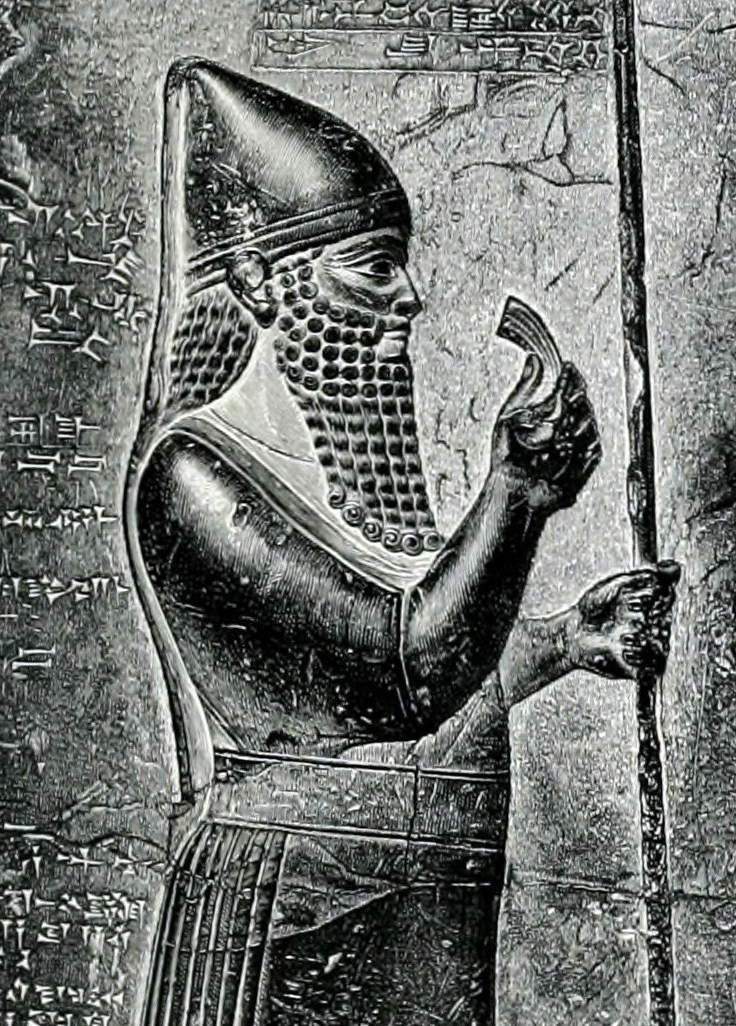

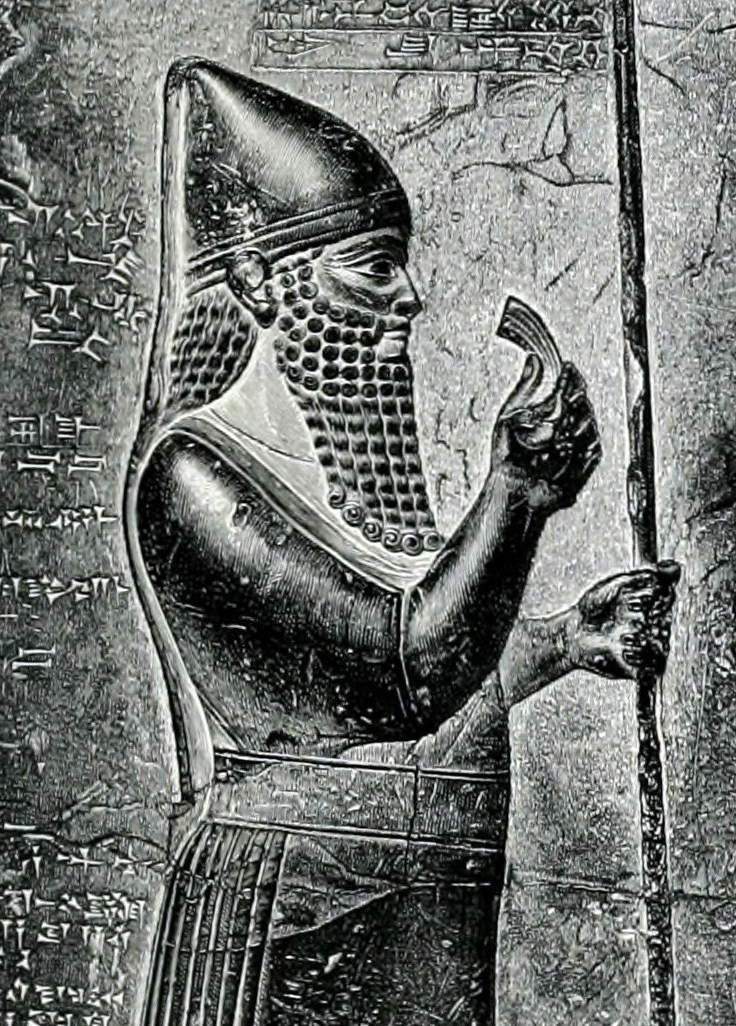

Nearly all Assyrian kings wished to outdo their predecessors and be remembered as glorious rulers. Sargon aspired to surpass all previous kings, even Sargon of Akkad. He established and cultivated his own cult of personality, for instance through having stelae made with depictions of him as a formidable king and placing these across the empire, often in highly visible places such as frequented passageways. In his palace in Dur-Sharrukin, Sargon decorated the walls with reliefs depicting himself and his achievements. He hoped that future generations would regard him as one of the greatest kings.

Sargon's aspiration for renown is also reflected in Dur-Sharrukin, which was likely founded mainly as an ideological statement given its location's lack of obvious merit. Perhaps inspired by Sargon of Akkad being credited as the founder of the city of Akkad (city), Akkad, Sargon II built Dur-Sharrukin for his own glory and intended the city, and his various other building works, to preserve his memory for generations to come. The inscriptions in Dur-Sharrukin evoke Sargon's desire to initiate a

Nearly all Assyrian kings wished to outdo their predecessors and be remembered as glorious rulers. Sargon aspired to surpass all previous kings, even Sargon of Akkad. He established and cultivated his own cult of personality, for instance through having stelae made with depictions of him as a formidable king and placing these across the empire, often in highly visible places such as frequented passageways. In his palace in Dur-Sharrukin, Sargon decorated the walls with reliefs depicting himself and his achievements. He hoped that future generations would regard him as one of the greatest kings.

Sargon's aspiration for renown is also reflected in Dur-Sharrukin, which was likely founded mainly as an ideological statement given its location's lack of obvious merit. Perhaps inspired by Sargon of Akkad being credited as the founder of the city of Akkad (city), Akkad, Sargon II built Dur-Sharrukin for his own glory and intended the city, and his various other building works, to preserve his memory for generations to come. The inscriptions in Dur-Sharrukin evoke Sargon's desire to initiate a

Sargon's legacy in ancient Assyria was severely damaged by the manner of his death; in particular, the failure to recover his body was a major psychological blow for Assyria. The shock and theological implications plagued the reigns of his successors for decades. The ancient Assyrians believed that unburied dead became ghosts that could come back and haunt the living. Sargon was believed to be doomed to a miserable afterlife; his ghost would wander the Earth, eternally restless and hungry. Soon after the news of Sargon's death reached the Assyrian heartland, the influential advisor and scribe Nabu-zuqup-kena copied Tablet XII of the ''Epic of Gilgamesh''. This tablet contains a section eerily similar to Sargon's death, with the miserable implications described in detail, which must have left the scribe stunned and distressed. In the Levant, Sargon's hubris was mocked. It is believed that a foreign ruler chided in the Biblical Book of Isaiah is based on Sargon.

Sennacherib was horrified by his father's death. The Assyriologist Eckart Frahm believes that Sennacherib was so deeply affected that he began suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder. Sennacherib was unable to acknowledge and mentally deal with what had transpired. Sargon's dishonorable death in battle and his lack of a burial was seen as a sign that he must have committed some serious and unforgivable sin that made the gods completely abandon him. Sennacherib concluded that Sargon had perhaps offended Babylon's gods by taking control of the city.

Sennacherib did everything he could to distance himself from Sargon and never wrote or built anything to honor Sargon's memory. One of his first building projects was restoring a temple dedicated to Nergal, god of the underworld, perhaps intended to pacify a deity possibly involved with Sargon's fate. Sennacherib also moved the capital to Nineveh, despite the fact that Dur-Sharrukin was entirely new and built to house the royal court. Given that Sargon modelled parts of his reign on Gilgamesh, Frahm believes that it is possible that Sennacherib abandoned Dur-Sharrukin on account of the ''Epic of Gilgamesh''. The furious and hungry spirit of a mighty king might have been feared to mean that Sennacherib would be unable to hold court there. Sennacherib spent a lot of time and effort to rid the empire of Sargon's imagery and work. Images Sargon had created at the temple in Assur were made invisible through raising the level of the courtyard and Sargon's queen Atalia was buried hastily when she died, without regard to traditional burial practices and in the same coffin as another woman. Despite this, Sennacherib attempted to avenge his father, sending an expedition to Tabal in 704 to kill Gurdî and perhaps retrieve Sargon's body; whether it was successful is not known.

After Sennacherib's reign, Sargon was sometimes mentioned as the ancestor of later kings. Assyria fell in the late 7th century BC. Though the local population of northern Mesopotamia never forgot ancient Assyria, knowledge of Assyria in Western Europe throughout the centuries thereafter derived from the writings of classical authors and the Bible. Due to the efforts of Sennacherib, Sargon was poorly remembered by the time these works were written. Sargon was obscure in

Sargon's legacy in ancient Assyria was severely damaged by the manner of his death; in particular, the failure to recover his body was a major psychological blow for Assyria. The shock and theological implications plagued the reigns of his successors for decades. The ancient Assyrians believed that unburied dead became ghosts that could come back and haunt the living. Sargon was believed to be doomed to a miserable afterlife; his ghost would wander the Earth, eternally restless and hungry. Soon after the news of Sargon's death reached the Assyrian heartland, the influential advisor and scribe Nabu-zuqup-kena copied Tablet XII of the ''Epic of Gilgamesh''. This tablet contains a section eerily similar to Sargon's death, with the miserable implications described in detail, which must have left the scribe stunned and distressed. In the Levant, Sargon's hubris was mocked. It is believed that a foreign ruler chided in the Biblical Book of Isaiah is based on Sargon.

Sennacherib was horrified by his father's death. The Assyriologist Eckart Frahm believes that Sennacherib was so deeply affected that he began suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder. Sennacherib was unable to acknowledge and mentally deal with what had transpired. Sargon's dishonorable death in battle and his lack of a burial was seen as a sign that he must have committed some serious and unforgivable sin that made the gods completely abandon him. Sennacherib concluded that Sargon had perhaps offended Babylon's gods by taking control of the city.

Sennacherib did everything he could to distance himself from Sargon and never wrote or built anything to honor Sargon's memory. One of his first building projects was restoring a temple dedicated to Nergal, god of the underworld, perhaps intended to pacify a deity possibly involved with Sargon's fate. Sennacherib also moved the capital to Nineveh, despite the fact that Dur-Sharrukin was entirely new and built to house the royal court. Given that Sargon modelled parts of his reign on Gilgamesh, Frahm believes that it is possible that Sennacherib abandoned Dur-Sharrukin on account of the ''Epic of Gilgamesh''. The furious and hungry spirit of a mighty king might have been feared to mean that Sennacherib would be unable to hold court there. Sennacherib spent a lot of time and effort to rid the empire of Sargon's imagery and work. Images Sargon had created at the temple in Assur were made invisible through raising the level of the courtyard and Sargon's queen Atalia was buried hastily when she died, without regard to traditional burial practices and in the same coffin as another woman. Despite this, Sennacherib attempted to avenge his father, sending an expedition to Tabal in 704 to kill Gurdî and perhaps retrieve Sargon's body; whether it was successful is not known.

After Sennacherib's reign, Sargon was sometimes mentioned as the ancestor of later kings. Assyria fell in the late 7th century BC. Though the local population of northern Mesopotamia never forgot ancient Assyria, knowledge of Assyria in Western Europe throughout the centuries thereafter derived from the writings of classical authors and the Bible. Due to the efforts of Sennacherib, Sargon was poorly remembered by the time these works were written. Sargon was obscure in

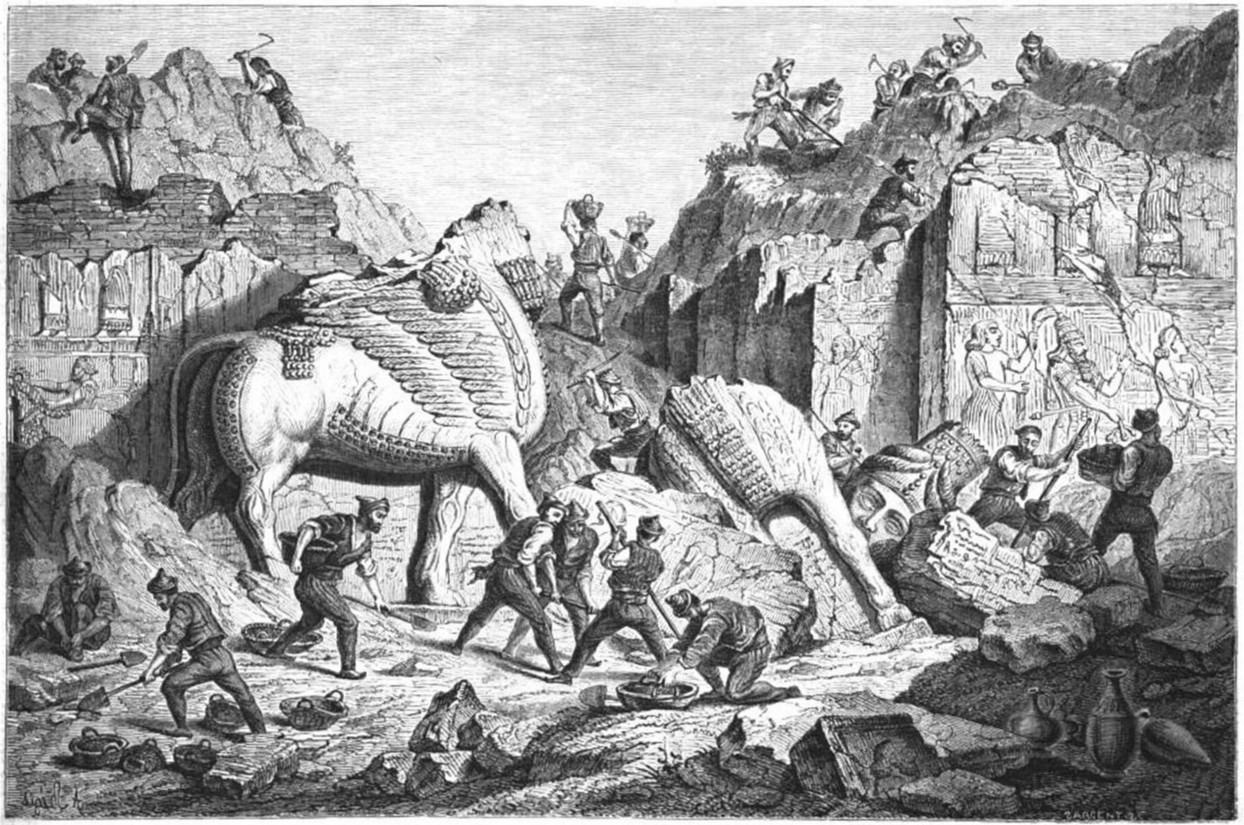

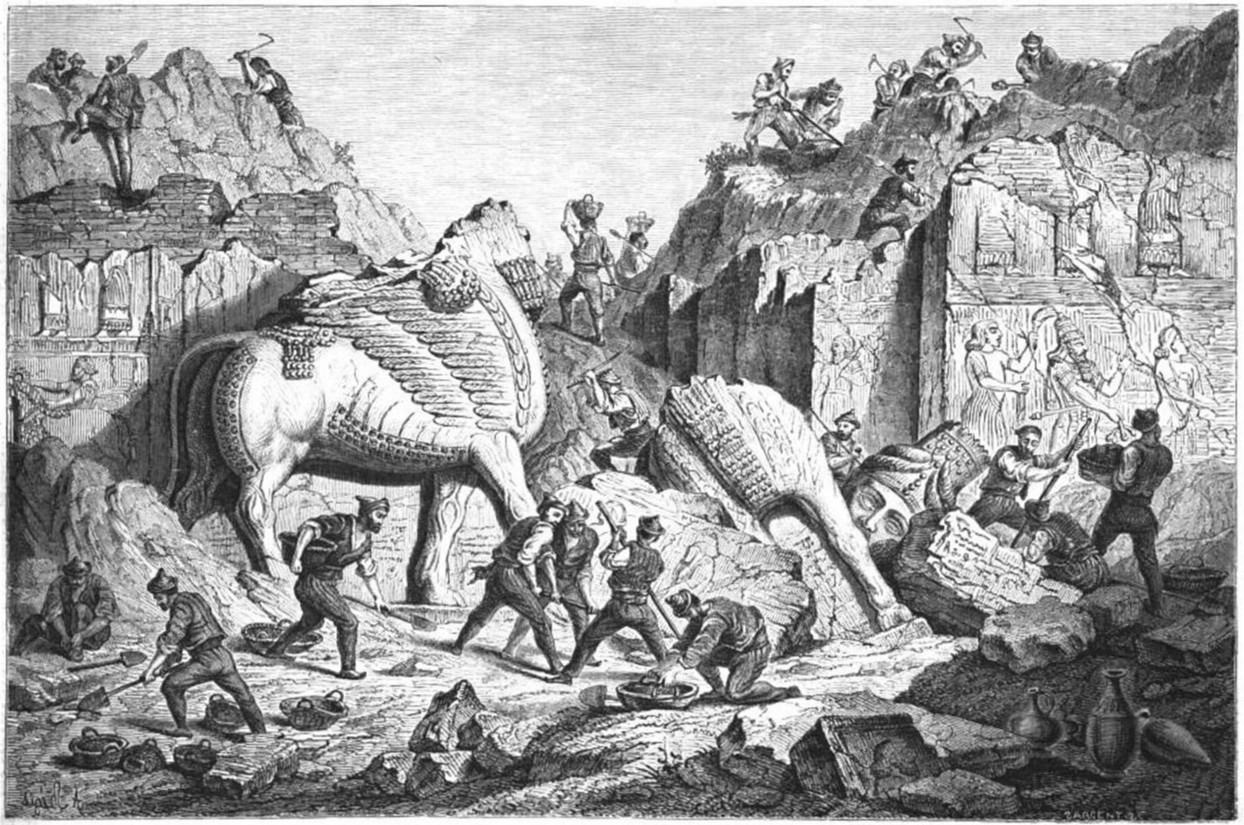

European explorers and archaeologists first began excavations in northern Mesopotamia in the early 19th century. Around this time some scholars began to place Sargon as a distinct king between Shalmaneser and Sennacherib. Dur-Sharrukin was found by chance; Paul-Émile Botta was conducting excavations at Nineveh when he heard about it from locals in 1843. Under Botta and his assistant Victor Place, virtually the entire palace was excavated, as were portions of the surrounding town. In 1847, the first-ever exhibition on Assyrian sculptures was held in the Louvre, composed of finds from Sargon's palace. Botta's report on his findings, published in 1849, garnered exceptional interest. Though much of what was excavated at Dur-Sharrukin was left in situ, reliefs and other artifacts have been exhibited across the world, including the Louvre, the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago and the Iraq Museum.

In 1845, Isidore Löwenstern was the first to suggest that Sargon was the builder of Dur-Sharrukin, although he based this identification on erroneous readings of cuneiform. After cuneiform was deciphered, archaeologist Adrien Prévost de Longpérier confirmed the king's name to be Sargon in 1847. Discussions and debate continued for several years and Sargon was not fully accepted by Assyriologists as a distinct king until the 1860s. Through the large number of sources left behind from his time, Sargon is better known than many of his predecessors and successors, and than the ancient Sargon of Akkad. Modern Assyriologists consider Sargon to have been one of the most important Assyrian kings given the substantial expansion of Assyrian territory undertaken in his reign and his political and military reforms. Sargon left a stable and strong empire, though it proved difficult to control by his successors. Sennacherib had to face several revolts against his rule, some of them motivated by the manner of Sargon's death, though they were all eventually defeated. Elayi assessed Sargon in 2017 as "the real founder of the empire" and a man who "succeeded in everything in his life, but completely failed in his death". Since the early 20th century, Sargon has also been a common name among modern Assyrian people.

European explorers and archaeologists first began excavations in northern Mesopotamia in the early 19th century. Around this time some scholars began to place Sargon as a distinct king between Shalmaneser and Sennacherib. Dur-Sharrukin was found by chance; Paul-Émile Botta was conducting excavations at Nineveh when he heard about it from locals in 1843. Under Botta and his assistant Victor Place, virtually the entire palace was excavated, as were portions of the surrounding town. In 1847, the first-ever exhibition on Assyrian sculptures was held in the Louvre, composed of finds from Sargon's palace. Botta's report on his findings, published in 1849, garnered exceptional interest. Though much of what was excavated at Dur-Sharrukin was left in situ, reliefs and other artifacts have been exhibited across the world, including the Louvre, the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago and the Iraq Museum.

In 1845, Isidore Löwenstern was the first to suggest that Sargon was the builder of Dur-Sharrukin, although he based this identification on erroneous readings of cuneiform. After cuneiform was deciphered, archaeologist Adrien Prévost de Longpérier confirmed the king's name to be Sargon in 1847. Discussions and debate continued for several years and Sargon was not fully accepted by Assyriologists as a distinct king until the 1860s. Through the large number of sources left behind from his time, Sargon is better known than many of his predecessors and successors, and than the ancient Sargon of Akkad. Modern Assyriologists consider Sargon to have been one of the most important Assyrian kings given the substantial expansion of Assyrian territory undertaken in his reign and his political and military reforms. Sargon left a stable and strong empire, though it proved difficult to control by his successors. Sennacherib had to face several revolts against his rule, some of them motivated by the manner of Sargon's death, though they were all eventually defeated. Elayi assessed Sargon in 2017 as "the real founder of the empire" and a man who "succeeded in everything in his life, but completely failed in his death". Since the early 20th century, Sargon has also been a common name among modern Assyrian people.

The Sargon Stele from Cyprus gives Sargon the following titles:

In an account of restoration work done to Ashurnasirpal II's palace in Nimrud (written before Sargon's reconquest of Babylonia), Sargon used the following longer titulature:

The Sargon Stele from Cyprus gives Sargon the following titles:

In an account of restoration work done to Ashurnasirpal II's palace in Nimrud (written before Sargon's reconquest of Babylonia), Sargon used the following longer titulature:

Ekron

Ekron (Philistine: 𐤏𐤒𐤓𐤍 ''*ʿAqārān'', he, עֶקְרוֹן, translit=ʿEqrōn, ar, عقرون), in the Hellenistic period known as Accaron ( grc-gre, Ακκαρων, Akkarōn}) was a Philistine city, one of the five cities o ...

and Gibbethon Gibbethon or Gibbeton was a city in the land of Canaan which, according to the record in the Hebrew Bible, was occupied by the Tribe of Dan after the entry of the Israelites into the Promised Land. According to the Book of Joshua, it was given as a ...

, the Assyrians defeated Hanunu, whose army had been bolstered by allies from Egypt, at Rafah

Rafah ( ar, رفح, Rafaḥ) is a Palestinian city in the southern Gaza Strip. It is the district capital of the Rafah Governorate, located south of Gaza City. Rafah's population of 152,950 (2014) is overwhelmingly made up of former Palestinian ...

. Despite the transgression, Gaza was kept as a semi-autonomous vassal state and not outright annexed, perhaps because the location, on the border of Egypt, was of high strategic importance.

Proxy wars and minor conflicts

A pressing concern for Sargon was the kingdom ofUrartu

Urartu (; Assyrian: ',Eberhard Schrader, ''The Cuneiform inscriptions and the Old Testament'' (1885), p. 65. Babylonian: ''Urashtu'', he, אֲרָרָט ''Ararat'') is a geographical region and Iron Age kingdom also known as the Kingdom of Va ...

in the north. Though no longer as powerful as it had been in the past, when it at times rivalled Assyria in strength and influence, Urartu still remained an alternative suzerain for many smaller states in the north. In 718, Sargon intervened in Mannea

Mannaea (, sometimes written as Mannea; Akkadian: ''Mannai'', Biblical Hebrew: ''Minni'', (מנּי)) was an ancient kingdom located in northwestern Iran, south of Lake Urmia, around the 10th to 7th centuries BC. It neighbored Assyria and Urartu, ...

, one of these states. This campaign was as much a military effort as it was a diplomatic one; King Iranzu

Iranzu was an important king of Mannae. King Iranzu died in 716 BC (estimated). His son Aza

Aza or AZA may refer to:

Places

*Aza, Azerbaijan, a village and municipality

*Azadkənd, Nakhchivan or Lower Aza, Azerbaijan

*Aza, medieval name of Haza ...

of Mannea had been an Assyrian vassal for more than 25 years and had requested Sargon to aid him. A rebellion by the Urartu-aligned noble Mitatti occupied half of Iranzu's kingdom, but thanks to Sargon Mitatti's uprising was suppressed. Shortly after the victory over the rebels, Iranzu died and Sargon intervened in the succession, supporting Iranzu's son Aza

Aza or AZA may refer to:

Places

*Aza, Azerbaijan, a village and municipality

*Azadkənd, Nakhchivan or Lower Aza, Azerbaijan

*Aza, medieval name of Haza, Province of Burgos, Spain

*Aźa, a Tibetan name for the Tuyuhun kingdom

*Aza, a Hebrew roman ...

rise to the throne of Mannea. Another son, Ullusunu, contested his brother's accession and was supported in his efforts against him by Rusa I

Rusa I (ruled: 735–714 BC) was a King of Urartu. He succeeded his father, king Sarduri II. His name is sometimes transliterated as ''Rusas'' or ''Rusha''. He was known to Assyrians as ''Ursa'' (which scholars have speculated is likely a more ac ...

of Urartu.

Another of Sargon's prominent foreign enemies was the powerful and expansionist Midas

Midas (; grc-gre, Μίδας) was the name of a king in Phrygia with whom several myths became associated, as well as two later members of the Phrygian royal house.

The most famous King Midas is popularly remembered in Greek mythology for his ...

of Phrygia

In classical antiquity, Phrygia ( ; grc, Φρυγία, ''Phrygía'' ) was a kingdom in the west central part of Anatolia, in what is now Asian Turkey, centered on the Sangarios River. After its conquest, it became a region of the great empires ...

in central Anatolia. Sargon worried about a possible alliance between Phrygia and Urartu and Midas' use of proxy warfare

A proxy war is an armed conflict between two states or non-state actors, one or both of which act at the instigation or on behalf of other parties that are not directly involved in the hostilities. In order for a conflict to be considered a pr ...

by encouraging Assyrian vassal states to rebel. Sargon could not fight against Midas directly but had to deal with uprisings by his vassals among the Syro-Hittite states

The states that are called Syro-Hittite, Neo-Hittite (in older literature), or Luwian-Aramean (in modern scholarly works), were Luwians, Luwian and Arameans, Aramean regional polities of the Iron Age, situated in southeastern parts of modern Turke ...

, most of them located in remote locations in the mountains of southern Anatolia. It was crucial to keep control over the regions of Tabal and Quwê

Quwê – also spelled Que, Kue, Qeve, Coa, Kuê and Keveh – was a Syro-Hittite Assyrian vassal state or province at various times from the 9th century BC to shortly after the death of Ashurbanipal around 627 BC in the lowlands of eas ...

to prevent communication between Midas and Rusa. Tabal—several minor states competing with each other, contested between Assyria, Phrygia and Urartu—was particularly important since it was rich in natural resources (including silver). Sargon campaigned against Tabal in 718, mostly against Kiakki of Shinuhtu, who withheld tribute and conspired with Midas. Sargon could not conquer Tabal because of its isolation and difficult terrain. Instead, Shinuhtu was given to a rival Tabalian ruler, Kurtî of Atunna. Kurtî conspired with Midas at some point between 718 and 713, but later maintained his allegiance to Sargon.

Sargon returned to Syria in 717 to defeat an uprising led by Pisiri of

Sargon returned to Syria in 717 to defeat an uprising led by Pisiri of Carchemish

Carchemish ( Turkish: ''Karkamış''; or ), also spelled Karkemish ( hit, ; Hieroglyphic Luwian: , /; Akkadian: ; Egyptian: ; Hebrew: ) was an important ancient capital in the northern part of the region of Syria. At times during its ...

, who had supported Sargon during Yahu-Bihdu's revolt but was now plotting with Midas to overthrow Assyrian hegemony

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one State (polity), state over other states. In Ancient Greece (8th BC – AD 6th ), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of the ''hegemon'' city-state over oth ...

in the region. The uprising was defeated and the population of Carchemish was deported and replaced with Assyrians. The city and its surrounding lands were turned into an Assyrian province and an Assyrian palace was constructed. The conquest might have inspired Sargon to build his own new capital city (Dur-Sharrukin

Dur-Sharrukin ("Fortress of Sargon"; ar, دور شروكين, Syriac: ܕܘܪ ܫܪܘ ܘܟܢ), present day Khorsabad, was the Assyrian capital in the time of Sargon II of Assyria. Khorsabad is a village in northern Iraq, 15 km northeast of Mo ...

), a project which could be financed with the silver

Silver is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/h₂erǵ-, ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, whi ...

plundered from Carchemish. Sargon took so much silver from Carchemish that silver began to replace copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkis ...

as the currency of the empire. Despite Sargon's repeated victories in the west, the Levant was not fully stabilized.

Sargon established a new trading post near the border of Egypt in 716, staffed it with people deported from various conquered lands and placed it under the local Arab ruler Laban Laban is a French language, French surname. It may refer to:

Places

* Laban-e Olya, a village in Iran

* Laban-e Sofla, a village in Iran

* Laban, Virginia, an unincorporated community in the United States

* 8539 Laban, main-belt asteroid

People

...

, an Assyrian vassal. In later writings, Sargon for unknown reasons falsely claimed that he in this year also subjugated the people of Egypt. In actuality, Sargon is recorded to have engaged in diplomacy with Pharaoh Osorkon IV

Usermaatre Osorkon IV was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh during the late Third Intermediate Period. Traditionally considered the last king of the 22nd Dynasty, he was ''de facto'' little more than ruler in Tanis and Bubastis, in Lower Egypt. He i ...

, who gifted Sargon with twelve horses.

In 716, Sargon campaigned between Urartu and Elam, perhaps part of a strategy to weaken these enemies. Passing through Mannea, Sargon attacked Media

Media may refer to:

Communication

* Media (communication), tools used to deliver information or data

** Advertising media, various media, content, buying and placement for advertising

** Broadcast media, communications delivered over mass el ...

, probably to establish control there and neutralize the region as a potential threat before confronting either Urartu or Elam. The local Medes were disunited and posed no serious threat to Assyria. After Sargon defeated them and established Assyrian provinces, he let the established local lords continue to rule their respective cities as vassals. Supplanting them and integrating the lands further into the imperial bureaucracy would have been costly and time-consuming due to their remoteness. As part of this eastern campaign, Sargon defeated some local rebels, including Bag-dati of Uishdish and Bel-sharru-usur of Kisheshim. In Mannea, Ullusunu had succeeded in taking the throne from his brother Aza. Instead of deposing Ullusunu and proclaiming a new king, Sargon accepted Ullusunu's submission and endorsed him as king, forgiving his uprising and gaining his allegiance.

Urartu–Assyria War

Cimmerians

The Cimmerians (Akkadian: , romanized: ; Hebrew: , romanized: ; Ancient Greek: , romanized: ; Latin: ) were an ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic people originating in the Caspian steppe, part of whom subsequently migrated into West A ...

, a nomadic people in the central Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historically ...

. The Cimmerians defeated the Urartian army and raided Urartian lands as far as immediately south-west of Lake Urmia

Lake Urmia;

az, اۇرمۇ گؤلۆ, script=Arab, italic=no, Urmu gölü;

ku, گۆلائوو رمیەیێ, Gola Ûrmiyeyê;

hy, Ուրմիա լիճ, Urmia lich;

arc, ܝܡܬܐ ܕܐܘܪܡܝܐ is an endorheic salt lake in Iran. The lake is ...

. Ullusunu of Mannea had switched his loyalty to Assyria. Rusa seized some of Ullusunu's fortresses and replaced him with Daiukku as the new king. Months later, Sargon invaded Mannea, recaptured Ullusunu's fortresses and restored him to the throne. Rusa attempted to drive Sargon back, but his army was defeated in the foothills of Sahand

Sahand ( fa, سهند), is a massive, heavily eroded stratovolcano in East Azerbaijan Province, northwestern Iran. At , it is the highest mountain in the province of East Azarbaijan.

Sahand is one of the highest mountains in Iranian Azerbaijan, ...

. Sargon also received the tribute of Ianzu, king of Nairi

Nairi (Traditional Armenian Orthography, classical hy, Նայիրի, ''Nayiri'', Reformed Armenian Orthography, reformed: Նաիրի, ''Nairi''; , also ''Na-'i-ru'') was the Akkadian language, Akkadian name for a region inhabited by a particular ...

, another former Urartian vassal. Preparing for a campaign against Rusa, Sargon defeated some minor rebels in Media. In Anatolia, Urik of Quwê, changed his allegiance from Sargon to Midas of Phrygia and began sending envoys to Rusa. To prevent the formation of a northern alliance, Sargon attacked Quwê, defeating Urik and recapturing some cities that had fallen to Midas. Quwê was abolished as a vassal kingdom and annexed.

Suspecting an Assyrian invasion, Rusa kept most of his army by Lake Urmia, close to the Assyrian border, which was already fortified against Assyrian invasion. The shortest path from Assyria to the Urartian heartland went through the ''Kel-i-šin'' pass in the Taurus Mountains

The Taurus Mountains ( Turkish: ''Toros Dağları'' or ''Toroslar'') are a mountain complex in southern Turkey, separating the Mediterranean coastal region from the central Anatolian Plateau. The system extends along a curve from Lake Eğirdir ...

. One of the most important places in all of Urartu, the holy city Musasir

Muṣaṣir (Assyrian cuneiform: and variants, including Mutsatsir, Akkadian for ''Exit of the Serpent/Snake''), in Urartian Ardini was an ancient city of Urartu, attested in Assyrian sources of the 9th and 8th centuries BC.

It was acquired by ...

, was located just west of this pass and was protected by fortifications. Rusa ordered the construction of the '' Gerdesorah'', a new fortress strategically positioned on a hill. The ''Gerdesorah'' was still under construction when the Assyrians invaded.

Nimrud

Nimrud (; syr, ܢܢܡܪܕ ar, النمرود) is an ancient Assyrian city located in Iraq, south of the city of Mosul, and south of the village of Selamiyah ( ar, السلامية), in the Nineveh Plains in Upper Mesopotamia. It was a majo ...

in July 714. Rejecting the shortest route through the ''Kel-i-šin'' pass, Sargon marched his army through the valleys of the Great

Great may refer to: Descriptions or measurements

* Great, a relative measurement in physical space, see Size

* Greatness, being divine, majestic, superior, majestic, or transcendent

People

* List of people known as "the Great"

*Artel Great (born ...

and Little Zab

The Little Zab or Lower Zab (, ''al-Zāb al-Asfal''; or '; , ''Zâb-e Kuchak''; , ''Zāba Taḥtāya'') is a river that originates in Iran and joins the Tigris just south of Al Zab in the Kurdistan region of Iraq. It is approximately long and dr ...

for three days before halting near Mount Kullar (the location of which remains unidentified). There Sargon chose a longer route through Kermanshah

Kermanshah ( fa, کرمانشاه, Kermânšâh ), also known as Kermashan (; romanized: Kirmaşan), is the capital of Kermanshah Province, located from Tehran in the western part of Iran. According to the 2016 census, its population is 946,68 ...

, probably since he knew the Urartians anticipated him attacking through the pass. The longer route delayed the Assyrians with mountains and greater distance. The campaign had to be completed before October, when the mountain passes would become blocked by snow. This meant that conquest, if that had been the intention, would not be possible.

Sargon reached Gilzanu, near Lake Urmia, and made camp. The Urartian forces regrouped and built new fortifications west and south of Lake Urmia. Though Sargon's forces had been granted supplies and water by his vassals in Media, his troops were exhausted and nearly mutinous. When Rusa arrived, the Assyrian army refused to fight. Sargon assembled his bodyguards and led them in a near-suicidal charge against the nearest wing of the Urartian forces. Sargon's army followed him, defeated the Urartians, and chased them west, far past Lake Urmia. Rusa abandoned his forces and fled into the mountains.

On their way home, the Assyrians destroyed the ''Gerdesorah'' and captured and plundered Musasir after the local governor, king Urzana, refused to welcome Sargon. An enormous quantity of spoils were carried back to Assyria. Urzana was forgiven and allowed to continue to govern Musasair as an Assyrian vassal. Though Urartu remained powerful and Rusa retook Musasir, the 714 campaign put an end to direct confrontations between Urartu and Assyria for the rest of Sargon's reign. Sargon considered the campaign one of the major events of his reign. It was described in exceptional detail in his inscriptions and several of the reliefs in his palace were decorated with representations of the sack of Musasir.

Construction of Dur-Sharrukin

Nineveh

Nineveh (; akk, ; Biblical Hebrew: '; ar, نَيْنَوَىٰ '; syr, ܢܝܼܢܘܹܐ, Nīnwē) was an ancient Assyrian city of Upper Mesopotamia, located in the modern-day city of Mosul in northern Iraq. It is located on the eastern ban ...

. The new city could use water from Mount Musri but the location otherwise lacked obvious practical or political merit. In one of his inscriptions, Sargon alluded to fondness for the foothills of Mount Musri: "following the prompting of my heart, I built a city at the foot of Mount Musri, in the plain of Nineveh, and named it Dur-Sharrukin". Since no buildings had ever been constructed at the chosen location, previous architecture did not have to be taken into account and he conceived the new city as an "ideal city", its proportions based on mathematical harmony. There were various numerical and geometrical correspondences between different aspects of the city and Dur-Sharrukin's city walls formed a nearly perfect square.

The numerous surviving sources on the construction of the city include inscriptions carved on the walls of its buildings, reliefs depicting the process and over a hundred letters and other documents describing the work. The chief coordinator was Tab-shar-Ashur, Sargon's chief treasurer, but at least twenty-six governors from across the empire were also associated with the construction; Sargon made the project a collaborative effort by the whole empire. Sargon took an active personal interest in the progress and frequently intervened in nearly all aspects of the work, from commenting on architectural details to overseeing material transportation and the recruitment of labor. Sargon's frequent input and efforts to encourage more work is probably the main reason for how the city could be completed so fast and efficiently. Sargon's encouragement was at times lenient, particularly when dealing with grumbling among the workers, but at other times threatening. One of his letters to the governor of Nimrud, requesting building materials, reads as follows:

Dur-Sharrukin reflected Sargon's self-image and how he wished the empire to see him. At about three square kilometers (1.2 square miles), the city was one of the largest in antiquity. The city's palace, which Sargon called a "palace without rival", was built on a huge artificial platform on the northern side of the city and was fortified with a wall of its own. At 100,000 square meters (10 hectares; 25 acres), it was the largest Assyrian palace ever built. It was richly decorated with reliefs, statues, glazed bricks and stone ''

The numerous surviving sources on the construction of the city include inscriptions carved on the walls of its buildings, reliefs depicting the process and over a hundred letters and other documents describing the work. The chief coordinator was Tab-shar-Ashur, Sargon's chief treasurer, but at least twenty-six governors from across the empire were also associated with the construction; Sargon made the project a collaborative effort by the whole empire. Sargon took an active personal interest in the progress and frequently intervened in nearly all aspects of the work, from commenting on architectural details to overseeing material transportation and the recruitment of labor. Sargon's frequent input and efforts to encourage more work is probably the main reason for how the city could be completed so fast and efficiently. Sargon's encouragement was at times lenient, particularly when dealing with grumbling among the workers, but at other times threatening. One of his letters to the governor of Nimrud, requesting building materials, reads as follows:

Dur-Sharrukin reflected Sargon's self-image and how he wished the empire to see him. At about three square kilometers (1.2 square miles), the city was one of the largest in antiquity. The city's palace, which Sargon called a "palace without rival", was built on a huge artificial platform on the northern side of the city and was fortified with a wall of its own. At 100,000 square meters (10 hectares; 25 acres), it was the largest Assyrian palace ever built. It was richly decorated with reliefs, statues, glazed bricks and stone ''lamassu

''Lama'', ''Lamma'', or ''Lamassu'' (Cuneiform: , ; Sumerian: lammař; later in Akkadian: ''lamassu''; sometimes called a ''lamassus'') is an Assyrian protective deity.

Initially depicted as a goddess in Sumerian times, when it was called ''La ...

s'' (human-headed bulls). Other prominent structures in the city included temples, a building in the southwest called the arsenal (''ekal mâšarti''), and a great park, which included exotic plants from throughout the empire. The city's surrounding wall was high and thick, reinforced at 15-meter (49 ft) intervals with more than two hundred bastions

A bastion or bulwark is a structure projecting outward from the curtain wall of a fortification, most commonly angular in shape and positioned at the corners of the fort. The fully developed bastion consists of two faces and two flanks, with fi ...

. The internal wall was named Ashur, the external wall Ninurta

, image= Cropped Image of Carving Showing the Mesopotamian God Ninurta.png

, caption= Assyrian stone relief from the temple of Ninurta at Kalhu, showing the god with his thunderbolts pursuing Anzû, who has stolen the Tablet of Destinies from En ...

, the city's seven gates Shamash

Utu (dUD "Sun"), also known under the Akkadian name Shamash, ''šmš'', syc, ܫܡܫܐ ''šemša'', he, שֶׁמֶשׁ ''šemeš'', ar, شمس ''šams'', Ashurian Aramaic: 𐣴𐣬𐣴 ''š'meš(ā)'' was the ancient Mesopotamian sun god. ...

, Adad

Hadad ( uga, ), Haddad, Adad (Akkadian: 𒀭𒅎 '' DIM'', pronounced as ''Adād''), or Iškur ( Sumerian) was the storm and rain god in the Canaanite and ancient Mesopotamian religions.

He was attested in Ebla as "Hadda" in c. 2500 BCE. ...

, Enlil

Enlil, , "Lord f theWind" later known as Elil, is an ancient Mesopotamian god associated with wind, air, earth, and storms. He is first attested as the chief deity of the Sumerian pantheon, but he was later worshipped by the Akkadians, Bab ...

, Anu

Anu ( akk, , from wikt:𒀭#Sumerian, 𒀭 ''an'' “Sky”, “Heaven”) or Anum, originally An ( sux, ), was the sky father, divine personification of the sky, king of the gods, and ancestor of many of the list of Mesopotamian deities, dei ...

, Ishtar

Inanna, also sux, 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒀭𒈾, nin-an-na, label=none is an ancient Mesopotamian goddess of love, war, and fertility. She is also associated with beauty, sex, divine justice, and political power. She was originally worshiped in S ...

, Ea and Belet-ili

, deity_of=Mother goddess, goddess of fertility, mountains, and rulers

, image= Mesopotamian - Cylinder Seal - Walters 42564 - Impression.jpg

, caption=Akkadian cylinder seal impression depicting a vegetation goddess, possibly Ninhursag, sitting ...

after gods of the Mesopotamian pantheon

Deities in ancient Mesopotamia were almost exclusively anthropomorphic. They were thought to possess extraordinary powers and were often envisioned as being of tremendous physical size. The deities typically wore ''melam'', an ambiguous substa ...

.

Further minor conflicts

In the years following the campaign against Rusa, Sargon worked to retain the loyalty of his northern vassals and to curb the influence of Elam; though Elam itself did not pose a threat towards Assyria, it would not be possible to reconquer Babylonia without first breaking Marduk-apla-iddina's alliance with the Elamites. In 713, Sargon campaigned in theZagros Mountains

The Zagros Mountains ( ar, جبال زاغروس, translit=Jibal Zaghrus; fa, کوههای زاگرس, Kuh hā-ye Zāgros; ku, چیاکانی زاگرۆس, translit=Çiyakani Zagros; Turkish: ''Zagros Dağları''; Luri: ''Kuh hā-ye Zāgro ...

again, defeating a revolt in the land of Karalla

''Karalla'' is a genus of marine ray-finned fishes, ponyfishes from the family Leiognathidae which are native to the Indian Ocean and the western Pacific Ocean.

Species

There are currently two recognized species in this genus:

* '' Karalla daura ...

, meeting with Ullusunu and receiving some tribute. In the same year, Sargon sent his ''turtanu "Turtanu" or "Turtan" (Akkadian: 𒌉𒋫𒉡 ''tur-ta-nu''; he, תַּרְתָּן ''tartān''; el, Θαρθαν; la, Tharthan; arc, ܬܵܪܬܵܢ ''tartan'') is an Akkadian word/title meaning 'commander in chief' or 'prime minister'. In Assyri ...

'' ( commander-in-chief) to help Talta of Ellipi

Ellipi was an ancient kingdom located on the western side of the Zagros (modern Iran), between Babylonia at the west, Media at the north east, Mannae at the north and Elam at the south. The inhabitants of Ellipi were close relatives of the Elam ...

, an Assyrian vassal beyond the Zagros Mountains. Sargon probably considered it important to keep good relations with Ellipi since it was a key buffer state between Assyria and Elam. Talta was threatened by a revolt, but after Assyrian intervention he retained his throne.

Rusa still intended to extend Urartian influence into southern Anatolia despite Sargon's 714 victory. In 713 Sargon campaigned against Tabal in southern Anatolia again, trying to secure the kingdom's natural resources (mainly silver and wood, required for the construction of Dur-Sharrukin) and to prevent Urartu from establishing control and contacting Phrygia. Sargon used a divide and rule

Divide and rule policy ( la, divide et impera), or divide and conquer, in politics and sociology is gaining and maintaining power divisively. Historically, this strategy was used in many different ways by empires seeking to expand their terr ...

approach in Tabal; territory was distributed between the different Tabalian rulers to prevent any one of them from growing strong enough to present a problem. Sargon also encouraged the loose hegemony of the strongest Tabalian state, Bit-Purutash (sometimes called "Tabal proper" by modern historians), over the other Tabalian rulers. The king of Bit-Purutash, Ambaris Ambaris was the sixth attested ruler of the kingdom of Tabal in Anatolia, in what is now Turkey. He ruled from 721-713 BC and under his rule the kingdom annexed the neighboring kingdom of Hilakku, forming the kingdom of Bit-Burutash.Trevor Bryce: '' ...

, was granted Sargon's daughter Ahat-Abisha in marriage and some additional territory. This strategy was not successful; Ambaris began conspiring with the other rulers of Tabal and with Rusa and Midas. Sargon deposed Ambaris, deporting him to Assyria, and annexed Tabal.

The Philistine

The Philistines ( he, פְּלִשְׁתִּים, Pəlīštīm; Koine Greek (LXX): Φυλιστιείμ, romanized: ''Phulistieím'') were an ancient people who lived on the south coast of Canaan from the 12th century BC until 604 BC, when ...

city of Ashdod

Ashdod ( he, ''ʾašdōḏ''; ar, أسدود or إسدود ''ʾisdūd'' or '' ʾasdūd'' ; Philistine: 𐤀𐤔𐤃𐤃 *''ʾašdūd'') is the sixth-largest city in Israel. Located in the country's Southern District, it lies on the Mediterran ...

rebelled under its king Azuri in 713, and was crushed by Sargon or one of his generals. Azuri was replaced as king by Ahi-Miti. In 712 the vassal king Tarhunazi of Kammanu

Kammanu was a Luwian speaking Neo-Hittite state in a plateau (Malatya Plain) to the north of the Taurus Mountains and to the west of Euphrates river in the late 2nd millennium BC, formed from part of Kizzuwatna after the collapse of the Hittite E ...

in northern Syria rebelled against Assyria, seeking to ally with Midas. Tahunazi had been placed on his throne during Sargon's 720 campaign in the Levant. This revolt was dealt with by Sargon's ''turtanu''; Tarhunazi was defeated and his lands were annexed. His capital, Melid

Melid, also known as Arslantepe, was an ancient city on the Tohma River, a tributary of the upper Euphrates rising in the Taurus Mountains. It has been identified with the modern archaeological site of Arslantepe near Malatya, Turkey.

It was ...

, was given to Mutallu of Kummuh

Kummuh was an Iron Age Neo-Hittite kingdom located on the west bank of the Upper Euphrates within the eastern loop of the river between Melid and Carchemish. Assyrian sources refer to both the land and its capital city by the same name. The city i ...

. Mutallu was a trusted ally since the kings of Kummuh had long maintained good relations with the Assyrian court. After the Assyrian army defeated a revolt by the kingdom of Gurgum

Gurgum was a Neo-Hittite state in Anatolia, known from the 10th to the 7th century BC. Its name is given as Gurgum in Assyrian sources, while its native name seems to have been Kurkuma for the reason that the capital of Gurgum—Marqas in Assyrian ...

in 711 and it was annexed, Sargon's control of southern Anatolia became relatively stable. Shortly after Sargon's victory, Ashdod revolted again. The locals deposed Ahi-Miti and in his stead proclaimed a noble named Yamani as king. In 712, Yamani approached Judah and Egypt for an alliance but the Egyptians refused Yamani's offer, maintaining good relations with Sargon. After the Assyrians defeated Yamani in 711 and Ashdod was destroyed, Yamani escaped to Egypt and was extradited to Assyria by Pharaoh Shebitku