Experimental psychology refers to work done by those who apply

experimental methods to psychological study and the underlying processes. Experimental psychologists employ

human participants and

animal subjects to study a great many topics, including (among others)

sensation & perception,

memory

Memory is the faculty of the mind by which data or information is encoded, stored, and retrieved when needed. It is the retention of information over time for the purpose of influencing future action. If past events could not be remembered, ...

,

cognition

Cognition refers to "the mental action or process of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thought, experience, and the senses". It encompasses all aspects of intellectual functions and processes such as: perception, attention, thought, ...

,

learning

Learning is the process of acquiring new understanding, knowledge, behaviors, skills, value (personal and cultural), values, attitudes, and preferences. The ability to learn is possessed by humans, animals, and some machine learning, machines ...

,

motivation

Motivation is the reason for which humans and other animals initiate, continue, or terminate a behavior at a given time. Motivational states are commonly understood as forces acting within the agent that create a disposition to engage in goal-dire ...

,

emotion

Emotions are mental states brought on by neurophysiological changes, variously associated with thoughts, feelings, behavioral responses, and a degree of pleasure or displeasure. There is currently no scientific consensus on a definition. ...

;

developmental processes,

social psychology

Social psychology is the scientific study of how thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are influenced by the real or imagined presence of other people or by social norms. Social psychologists typically explain human behavior as a result of the r ...

, and the

neural substrates of all of these.

History

Early experimental psychology

Wilhelm Wundt

Experimental psychology emerged as a modern academic discipline in the 19th century when

Wilhelm Wundt

Wilhelm Maximilian Wundt (; ; 16 August 1832 – 31 August 1920) was a German physiologist, philosopher, and professor, known today as one of the fathers of modern psychology. Wundt, who distinguished psychology as a science from philosophy and ...

introduced a mathematical and experimental approach to the field. Wundt founded the first psychology laboratory in

Leipzig, Germany

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the Germany, German States of Germany, state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's L ...

.

Other experimental psychologists, including

Hermann Ebbinghaus

Hermann Ebbinghaus (24 January 185026 February 1909) was a German psychologist who pioneered the experimental study of memory, and is known for his discovery of the forgetting curve and the spacing effect. He was also the first person to describ ...

and

Edward Titchener

Edward Bradford Titchener (11 January 1867 – 3 August 1927) was an English psychologist who studied under Wilhelm Wundt for several years. Titchener is best known for creating his version of psychology that described the structure of the min ...

, included

introspection

Introspection is the examination of one's own conscious thoughts and feelings. In psychology, the process of introspection relies on the observation of one's mental state, while in a spiritual context it may refer to the examination of one's s ...

in their experimental methods.

Charles Bell

Charles Bell

Sir Charles Bell (12 November 177428 April 1842) was a Scotland, Scottish surgeon, anatomist, physiologist, neurologist, artist, and philosophical theologian. He is noted for discovering the difference between sensory nerves and motor nerves in ...

was a British

physiologist

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemical a ...

whose main contribution to the medical and scientific community was his research on the

nervous system

In biology, the nervous system is the highly complex part of an animal that coordinates its actions and sensory information by transmitting signals to and from different parts of its body. The nervous system detects environmental changes th ...

. He wrote a pamphlet summarizing his research on rabbits. His research concluded that sensory nerves enter at the posterior (dorsal) roots of the spinal cord, and motor nerves emerge from the anterior (ventral) roots of the spinal cord. Eleven years later, a French physiologist,

Francois Magendie, published the same findings without being aware of Bell's research. As a result of Bell not publishing his research, this discovery was called the

Bell-Magendie law to honor both individuals. Bell's discovery disproved the belief that nerves transmitted either vibrations or spirits.

Ernst Heinrich Weber

Ernst Heinrich Weber

Ernst Heinrich Weber (24 June 1795 – 26 January 1878) was a German physician who is considered one of the founders of experimental psychology. He was an influential and important figure in the areas of physiology and psychology during his lif ...

, a German physician, is credited as one of experimental psychology's founders. Weber's main interests were the sense of touch and kinesthesis. His most memorable contribution to the field of experimental psychology is the suggestion that judgments of sensory differences are relative and not absolute. This relativity is expressed in "Weber's Law," which suggests that the

just-noticeable difference

In the branch of experimental psychology focused on sense, sensation, and perception, which is called psychophysics, a just-noticeable difference or JND is the amount something must be changed in order for a difference to be noticeable, detectabl ...

or jnd is a constant proportion of the ongoing stimulus level. Weber's Law is stated as an equation:

:

where

is the original intensity of stimulation,

is the addition to it required for the difference to be perceived (the jnd), and ''k'' is a constant. Thus, for k to remain constant,

must rise as I increases. Weber's law is considered to be the first quantitative law in the history of psychology.

Gustav Fechner

Fechner published in 1860 what is considered to be the first work of experimental psychology, "Elemente der Psychophysik."

[Fraisse, P, Piaget, J, & Reuchlin, M. (1963). Experimental psychology: its scope and method. 1. History and method. New York: Basic Books.] Some historians date the beginning of experimental psychology to the publication of "Elemente."

Ernst Heinrich Weber

Ernst Heinrich Weber (24 June 1795 – 26 January 1878) was a German physician who is considered one of the founders of experimental psychology. He was an influential and important figure in the areas of physiology and psychology during his lif ...

was not a psychologist, but it was Fechner who realized the importance of Weber's research to psychology.

Weber's law and Fechner's law was published in Fechner's work, "Elemente der Psychophysik," and Fechner, a student of Weber named his first law in honor of his mentor. Fechner was profoundly interested in establishing a scientific study of the mind-body relationship, which became known as

psychophysics

Psychophysics quantitatively investigates the relationship between physical stimuli and the sensations and perceptions they produce. Psychophysics has been described as "the scientific study of the relation between stimulus and sensation" or, m ...

. Much of Fechner's research focused on the measurement of psychophysical thresholds and

just-noticeable differences. He invented the psychophysical method of limits, the method of constant stimuli, and the method of adjustment, which are still in use.

Oswald Külpe

Oswald Külpe is the main founder of the Würzburg School in Germany. He was a pupil of

Wilhelm Wundt

Wilhelm Maximilian Wundt (; ; 16 August 1832 – 31 August 1920) was a German physiologist, philosopher, and professor, known today as one of the fathers of modern psychology. Wundt, who distinguished psychology as a science from philosophy and ...

for about twelve years. Unlike Wundt, Külpe believed experiments were possible to test higher mental processes. In 1883 he wrote Grundriss der Psychologie, which had strictly scientific facts and no mention of thought.

[Fraisse, P, Piaget, J, & Reuchlin, M. (1963). Experimental psychology: its scope and method. 1. History and method. New York: Basic Books.] The lack of thought in his book is odd because the Würzburg School put a lot of emphasis on mental set and imageless thought.

Würzburg School

The work of the Würzburg School was a milestone in the development of experimental psychology. The School was founded by a group of psychologists led by Oswald Külpe, and it provided an alternative to the

structuralism

In sociology, anthropology, archaeology, history, philosophy, and linguistics, structuralism is a general theory of culture and methodology that implies that elements of human culture must be understood by way of their relationship to a broader ...

of Edward Titchener and Wilhelm Wundt. Those in the School focused mainly on mental operations such as mental set (''Einstellung'') and imageless thought. Mental set affects perception and problem solving without the awareness of the individual; it can be triggered by instructions or by experience. Similarly, according to Külpe, imageless thought consists of pure mental acts that do not involve mental images. William Bryan, an American student, working in Külpe's laboratory, provided an example of mental set. Bryan presented subjects with cards that had nonsense syllables written on them in various colors. The subjects were told to attend to the syllables, and in consequence, they did not remember the colors of the nonsense syllables. Such results made people question the validity of introspection as a research tool, leading to a decline in

voluntarism and structuralism. The work of the Würzburg School later influenced many

Gestalt psychologists

Gestalt-psychology, gestaltism, or configurationism is a school of psychology that emerged in the early twentieth century in Austria and Germany as a theory of perception that was a rejection of basic principles of Wilhelm Wundt's and Edward T ...

, including

Max Wertheimer

Max Wertheimer (April 15, 1880 – October 12, 1943) was an Austro-Hungarian psychologist who was one of the three founders of Gestalt psychology, along with Kurt Koffka and Wolfgang Köhler. He is known for his book, ''Productive Thinking'', and f ...

.

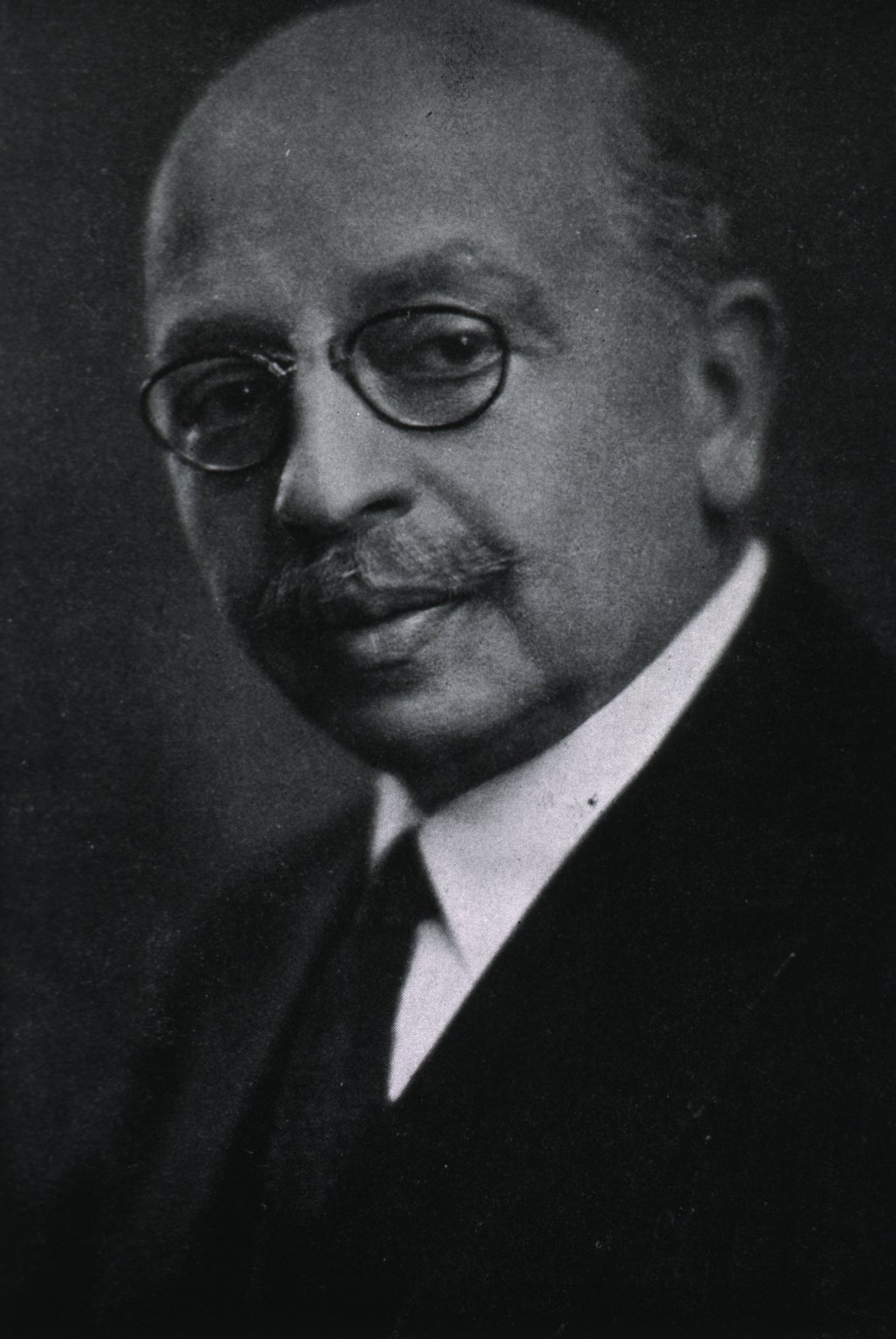

George Trumbull Ladd

George Trumbull Ladd

George Trumbull Ladd (; January 19, 1842 – August 8, 1921) was an American philosopher, educator and psychologist.

Biography

Early life and ancestors

Ladd was born in Painesville, Ohio, on January 19, 1842, the son of Silas Trumbull Ladd and ...

introduced experimental psychology into the United States and founded

Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wo ...

's psychological laboratory in 1879. In 1887, Ladd published ''Elements of Physiological Psychology'', the first American textbook that extensively discussed experimental psychology. Between Ladd's founding of the Yale Laboratory and his textbook, the center of experimental psychology in the US shifted to

Johns Hopkins University

Johns Hopkins University (Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private university, private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1876, Johns Hopkins is the oldest research university in the United States and in the western hem ...

, where

George Hall and

Charles Sanders Peirce

Charles Sanders Peirce ( ; September 10, 1839 – April 19, 1914) was an American philosopher, logician, mathematician and scientist who is sometimes known as "the father of pragmatism".

Educated as a chemist and employed as a scientist for t ...

were extending and qualifying Wundt's work.

Charles Sanders Peirce

With his student

Joseph Jastrow

Joseph Jastrow (January 30, 1863 – January 8, 1944) was a Polish-born American psychologist, noted for inventions in experimental psychology, design of experiments, and psychophysics. He also worked on the phenomena of optical illusions, ...

,

Charles S. Peirce

Charles Sanders Peirce ( ; September 10, 1839 – April 19, 1914) was an American philosopher, logician, mathematician and scientist who is sometimes known as "the father of pragmatism".

Educated as a chemist and employed as a scientist for t ...

randomly assigned volunteers to a

blinded,

repeated-measures design to evaluate their ability to discriminate weights.

Peirce's experiment inspired other researchers in psychology and education, which developed a research tradition of randomized experiments in laboratories and specialized textbooks in the 1800s.

The Peirce–Jastrow experiments were conducted as part of Peirce's

pragmatic

Pragmatism is a philosophical movement.

Pragmatism or pragmatic may also refer to:

*Pragmaticism, Charles Sanders Peirce's post-1905 branch of philosophy

*Pragmatics, a subfield of linguistics and semiotics

*''Pragmatics'', an academic journal in ...

program to understand

human perception

Perception () is the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information in order to represent and understand the presented information or environment. All perception involves signals that go through the nervous system ...

; other studies considered perception of light, etc. While Peirce was making advances in experimental psychology and

psychophysics

Psychophysics quantitatively investigates the relationship between physical stimuli and the sensations and perceptions they produce. Psychophysics has been described as "the scientific study of the relation between stimulus and sensation" or, m ...

, he was also developing a theory of

statistical inference

Statistical inference is the process of using data analysis to infer properties of an underlying probability distribution, distribution of probability.Upton, G., Cook, I. (2008) ''Oxford Dictionary of Statistics'', OUP. . Inferential statistical ...

, which was published in "

Illustrations of the Logic of Science" (1877–78) and "

A Theory of Probable Inference" (1883); both publications that emphasized the importance of randomization-based inference in statistics. To Peirce and to experimental psychology belongs the honor of having invented

randomized experiment

In science, randomized experiments are the experiments that allow the greatest reliability and validity of statistical estimates of treatment effects. Randomization-based inference is especially important in experimental design and in survey sampl ...

s decades before the innovations of

Jerzy Neyman

Jerzy Neyman (April 16, 1894 – August 5, 1981; born Jerzy Spława-Neyman; ) was a Polish mathematician and statistician who spent the first part of his professional career at various institutions in Warsaw, Poland and then at University College ...

and

Ronald Fisher

Sir Ronald Aylmer Fisher (17 February 1890 – 29 July 1962) was a British polymath who was active as a mathematician, statistician, biologist, geneticist, and academic. For his work in statistics, he has been described as "a genius who a ...

in agriculture.

Peirce's pragmaticist philosophy also included an extensive theory of mental representations and cognition, which he studied under the name of

semiotics

Semiotics (also called semiotic studies) is the systematic study of sign processes ( semiosis) and meaning making. Semiosis is any activity, conduct, or process that involves signs, where a sign is defined as anything that communicates something ...

. Peirce's student

Joseph Jastrow

Joseph Jastrow (January 30, 1863 – January 8, 1944) was a Polish-born American psychologist, noted for inventions in experimental psychology, design of experiments, and psychophysics. He also worked on the phenomena of optical illusions, ...

continued to conduct randomized experiments throughout his distinguished career in experimental psychology, much of which would later be recognized as

cognitive psychology

Cognitive psychology is the scientific study of mental processes such as attention, language use, memory, perception, problem solving, creativity, and reasoning.

Cognitive psychology originated in the 1960s in a break from behaviorism, which ...

. There has been a resurgence of interest in Peirce's work in cognitive psychology. Another student of Peirce,

John Dewey

John Dewey (; October 20, 1859 – June 1, 1952) was an American philosopher, psychologist, and educational reformer whose ideas have been influential in education and social reform. He was one of the most prominent American scholars in the f ...

, conducted experiments on human

cognition

Cognition refers to "the mental action or process of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thought, experience, and the senses". It encompasses all aspects of intellectual functions and processes such as: perception, attention, thought, ...

, particularly in schools, as part of his "experimental logic" and "public philosophy."

20th century

In the middle of the 20th century,

behaviorism

Behaviorism is a systematic approach to understanding the behavior of humans and animals. It assumes that behavior is either a reflex evoked by the pairing of certain antecedent (behavioral psychology), antecedent stimuli in the environment, o ...

became a dominant paradigm within psychology, especially in the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

. This led to some neglect of

mental phenomena within experimental psychology. In

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

, this was less the case, as European psychology was influenced by psychologists such as

Sir Frederic Bartlett,

Kenneth Craik

Kenneth James William Craik (; 1914 – 1945) was a Scottish philosopher and psychologist.

Life

He was born in Edinburgh on 29 March 1914, the son of James Craik, a solicitor. The family lived at 13 Abercromby Place in Edinburgh's Second N ...

,

W.E. Hick, and

Donald Broadbent

Donald Eric (D. E.) Broadbent CBE, FRS (Birmingham, 6 May 1926 – 10 April 1993) was an influential experimental psychologist from the UK His career and research bridged the gap between the pre-World War II approach of Sir Frederic Bartlett a ...

, who focused on topics such as

thinking

In their most common sense, the terms thought and thinking refer to conscious cognitive processes that can happen independently of sensory stimulation. Their most paradigmatic forms are judging, reasoning, concept formation, problem solving, an ...

,

memory

Memory is the faculty of the mind by which data or information is encoded, stored, and retrieved when needed. It is the retention of information over time for the purpose of influencing future action. If past events could not be remembered, ...

, and

attention

Attention is the behavioral and cognitive process of selectively concentrating on a discrete aspect of information, whether considered subjective or objective, while ignoring other perceivable information. William James (1890) wrote that "Atte ...

. This laid the foundations for the subsequent development of cognitive psychology.

In the latter half of the 20th century, the phrase "experimental psychology" had shifted in meaning due to the expansion of psychology as a discipline and the growth in its sub-disciplines. Experimental psychologists use a range of methods and do not confine themselves to a strictly experimental approach, partly because developments in the

philosophy of science

Philosophy of science is a branch of philosophy concerned with the foundations, methods, and implications of science. The central questions of this study concern what qualifies as science, the reliability of scientific theories, and the ultim ...

have affected the exclusive prestige of experimentation. In contrast, experimental methods are now widely used in fields such as developmental and

social psychology

Social psychology is the scientific study of how thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are influenced by the real or imagined presence of other people or by social norms. Social psychologists typically explain human behavior as a result of the r ...

, which were not previously part of experimental psychology. The phrase continues in use in the titles of a number of well-established, high prestige

learned societies

A learned society (; also learned academy, scholarly society, or academic association) is an organization that exists to promote an academic discipline, profession, or a group of related disciplines such as the arts and science. Membership may ...

and

scientific journals

In academic publishing, a scientific journal is a periodical publication intended to further the progress of science, usually by reporting new research.

Content

Articles in scientific journals are mostly written by active scientists such as s ...

, as well as some

university

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States, t ...

courses of study in psychology.

Institutional review board (IRB)

In 1974, the

National Research Act

The National Research Act was enacted by the 93rd United States Congress and signed into law by President Richard Nixon on July 12, 1974, after a series of congressional hearings on human-subjects research, directed by Senator Edward Kennedy. The ...

established the existence of the

institutional review board

An institutional review board (IRB), also known as an independent ethics committee (IEC), ethical review board (ERB), or research ethics board (REB), is a committee that applies research ethics by reviewing the methods proposed for research to ens ...

in the United States following several controversial experiments. Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) play an important role in monitoring the conduct of psychological experiments. Their presence is required by law at institutions such as universities where psychological research occurs. Their purpose is to make sure that experiments do not violate ethical codes or legal requirements; thus they protect human subjects from physical or psychological harm and assure the humane treatment of animal subjects. An IRB must review the procedure to be used in each experiment before that experiment may begin. The IRB also assures that human participants give informed consent in advance; that is, the participants are told the general nature of the experiment and what will be required of them. There are three types of review that may be undertaken by an IRB - exempt, expedited, and full review. More information is available on the main IRB page.

Methodology

Sound methodology is essential to the study of complex behavioral and mental processes, and this implies, especially, the careful definition and control of experimental variables. The research methodologies employed in experimental psychology utilize techniques in research to seek to uncover new knowledge or validate existing claims. Typically, this entails a number of stages, including selecting a sample, gathering data from this sample, and evaluating this data. From assumptions made by researchers when undertaking a project, to the scales used, the research design, and data analysis, proper methodology in experimental psychology is made up of several critical stages.

Assumptions

Empiricism

Perhaps the most basic assumption of science is that factual statements about the world must ultimately be based on observations of the world. This notion of

empiricism

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological theory that holds that knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience. It is one of several views within epistemology, along with rationalism and skepticism. Empir ...

requires that hypotheses and theories be tested against observations of the natural world rather than on a priori reasoning, intuition, or revelation.

Testability

Closely related to empiricism is the idea that, to be useful, a scientific law or theory must be testable with available research methods. If a theory cannot be tested in any conceivable way then many scientists consider the theory to be meaningless. Testability implies

falsifiability

Falsifiability is a standard of evaluation of scientific theories and hypotheses that was introduced by the philosopher of science Karl Popper in his book ''The Logic of Scientific Discovery'' (1934). He proposed it as the cornerstone of a sol ...

, which is the idea that some set of observations could prove the theory to be incorrect. Testability has been emphasized in psychology because influential or well-known theories like those of

Freud

Sigmund Freud ( , ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating pathologies explained as originating in conflicts in ...

have been difficult to test.

Determinism

Experimental psychologists, like most scientists, accept the notion of

determinism

Determinism is a philosophical view, where all events are determined completely by previously existing causes. Deterministic theories throughout the history of philosophy have developed from diverse and sometimes overlapping motives and consi ...

. This is the assumption that any state of an object or event is determined by prior states. In other words, behavioral or mental phenomena are typically stated in terms of cause and effect. If a phenomenon is sufficiently general and widely confirmed, it may be called a "law"; psychological theories serve to organize and integrate laws.

Parsimony

Another guiding idea of science is parsimony, the search for simplicity. For example, most scientists agree that if two theories handle a set of empirical observations equally well, we should prefer the simpler or more parsimonious of the two. A notable early argument for parsimony was stated by the medieval English philosopher

William of Occam

William of Ockham, OFM (; also Occam, from la, Gulielmus Occamus; 1287 – 10 April 1347) was an English Franciscan friar, scholastic philosopher, apologist, and Catholic theologian, who is believed to have been born in Ockham, a small vill ...

, and for this reason, the principle of parsimony is often referred to as

Occam's razor

Occam's razor, Ockham's razor, or Ocham's razor ( la, novacula Occami), also known as the principle of parsimony or the law of parsimony ( la, lex parsimoniae), is the problem-solving principle that "entities should not be multiplied beyond neces ...

.

Operational definition

Some well-known behaviorists such as

Edward C. Tolman

Edward Chace Tolman (April 14, 1886 – November 19, 1959) was an American psychologist and a professor of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley. Through Tolman's theories and works, he founded what is now a branch of psychology know ...

and

Clark Hull

Clark Leonard Hull (May 24, 1884 – May 10, 1952) was an American psychologist who sought to explain learning and motivation by scientific laws of behavior. Hull is known for his debates with Edward C. Tolman. He is also known for his work in dr ...

popularized the idea of operationism, or operational definition. Operational definition implies that a concept be defined in terms of concrete, observable procedures. Experimental psychologists attempt to define currently unobservable phenomena, such as mental events, by connecting them to observations by chains of reasoning.

Reliability and Validity

Reliability

Reliability measures the consistency or repeatability of an observation. For example, one way to assess reliability is the "test-retest" method, done by measuring a group of participants at one time and then testing them a second time to see if the results are consistent. Because the first test itself may alter the results of a second test, other methods are often used. For example, in the "split-half" measure, a group of participants is divided at random into two comparable sub-groups, and reliability is measured by comparing the test results from these groups, It is important to note that a reliable measure need not yield a valid conclusion.

Validity

Validity measures the relative accuracy or correctness of conclusions drawn from a study. To determine the validity of a measurement quantitatively, it must be compared with a criterion. For example, to determine the validity of a test of academic ability, that test might be given to a group of students and the results correlated with the grade-point averages of the individuals in that group. As this example suggests, there is often controversy in the selection of appropriate criteria for a given measure. In addition, a conclusion can only be valid to the extent that the observations upon which it is based are reliable.

Several types of validity have been distinguished, as follows:

= Internal validity

=

Internal validity

Internal validity is the extent to which a piece of evidence supports a claim about cause and effect, within the context of a particular study. It is one of the most important properties of scientific studies and is an important concept in reason ...

refers to the extent to which a set of research findings provides compelling information about causality. High internal validity implies that the experimental design of a study excludes extraneous influences, such that one can confidently conclude that variations in the independent variable caused any observed changes in the dependent variable.

= External validity

=

External Validity

External validity is the validity of applying the conclusions of a scientific study outside the context of that study. In other words, it is the extent to which the results of a study can be generalized to and across other situations, people, stim ...

refers to the extent to which the outcome of an experiment can be generalized to apply to other situations than those of the experiment - for example, to other people, other physical or social environments, or even other cultures.

= Construct validity

=

Construct validity Construct validity concerns how well a set of indicators represent or reflect a concept that is not directly measurable. ''Construct validation'' is the accumulation of evidence to support the interpretation of what a measure reflects.Polit DF Beck ...

refers to the extent to which the independent and dependent variables in a study represent the abstract hypothetical variables of interest. In other words, it has to do with whether the manipulated and/or measured variables in a study accurately reflect the variables the researcher hoped to manipulate. Construct validity also reflects the quality of one's operational definitions. If a researcher has done a good job of converting the abstract to the observable, construct validity is high.

= Conceptual validity

=

Conceptual validity refers to how well specific research maps onto the broader theory that it was designed to test. Conceptual and construct validity have a lot in common, but conceptual validity relates a study to broad theoretical issues whereas construct validity has more to do with specific manipulations and measures.

Scales of measurement

Measurement can be defined as "the assignment of numerals to objects or events according to rules."

[Torgerson, W. S. (1962) Theory and Methods of Scaling. New York: Wiley][Stevens, S. S. (1951) Mathematics, Measurement and Psychophysics in S. S. Stevens (Ed) Handbook of Experimental Psychology. New York: Wiley]

Almost all psychological experiments involve some sort of measurement, if only to determine the reliability and validity of results, and of course measurement is essential if results are to be relevant to quantitative theories.

The rule for assigning numbers to a property of an object or event is called a "scale". Following are the basic scales used in psychological measurement.

Nominal measurement

In a nominal scale, numbers are used simply as labels – a letter or name would do as well. Examples are the numbers on the shirts of football or baseball players. The labels are more useful if the same label can be given to more than one thing, meaning that the things are equal in some way, and can be classified together.

Ordinal measurement

An ordinal scale arises from the ordering or ranking objects, so that A is greater than B, B is greater than C, and so on. Many psychological experiments yield numbers of this sort; for example, a participant might be able to rank odors such that A is more pleasant than B, and B is more pleasant than C, but these rankings ("1, 2, 3 ...") would not tell by how much each odor differed from another. Some statistics can be computed from ordinal measures – for example,

median

In statistics and probability theory, the median is the value separating the higher half from the lower half of a data sample, a population, or a probability distribution. For a data set, it may be thought of as "the middle" value. The basic fe ...

, percentile, and

order correlation – but others, such as

standard deviation

In statistics, the standard deviation is a measure of the amount of variation or dispersion of a set of values. A low standard deviation indicates that the values tend to be close to the mean (also called the expected value) of the set, while ...

, cannot properly be used.

Interval measurement

An interval scale is constructed by determining the equality of differences between the things measured. That is, numbers form an interval scale when the differences between the numbers correspond to differences between the properties measured. For instance, one can say that the difference between 5 and 10 degrees on a Fahrenheit thermometer equals the difference between 25 and 30, but it is meaningless to say that something with a temperature of 20 degrees Fahrenheit is "twice as hot" as something with a temperature of 10 degrees. (Such ratios are meaningful on an

absolute temperature scale such as the Kelvin scale. See next section.) "Standard scores" on an achievement test are said to be measurements on an interval scale, but this is difficult to prove.

Ratio measurement

A ratio scale is constructed by determining the equality of ratios. For example, if, on a balance instrument, object A balances two identical objects B, then one can say that A is twice as heavy as B and can give them appropriate numbers, for example "A weighs 2 grams" and "B weighs 1 gram". A key idea is that such ratios remain the same regardless of the scale units used; for example, the ratio of A to B remains the same whether grams or ounces are used. Length, resistance, and Kelvin temperature are other things that can be measured on ratio scales. Some psychological properties such as the loudness of a sound can be measured on a ratio scale.

Research design

One-way designs

The simplest experimental design is a one-way design, in which there is only one independent variable. The simplest kind of one-way design involves just two-groups, each of which receives one value of the independent variable. A two-group design typically consists of an

experimental group

An experiment is a procedure carried out to support or refute a hypothesis, or determine the efficacy or likelihood of something previously untried. Experiments provide insight into Causality, cause-and-effect by demonstrating what outcome oc ...

(a group that receives treatment) and a

control group

In the design of experiments, hypotheses are applied to experimental units in a treatment group.

In comparative experiments, members of a control group receive a standard treatment, a placebo, or no treatment at all. There may be more than one tr ...

(a group that does not receive treatment).

The one-way design may be expanded to a one-way, multiple groups design. Here a single independent variable takes on three or more levels. This type of design is particularly useful because it can help to outline a functional relationship between the independent and dependent variables.

Factorial designs

One-way designs are limited in that they allow researchers to look at only one independent variable at a time, whereas many phenomena of interest are dependent on multiple variables. Because of this,

R.A Fisher popularized the use of factorial designs.

Factorial designs contain two or more independent variables that are completely "crossed," which means that every level each independent variable appears in combination with every level of all other independent variables. Factorial designs carry labels that specify the number of independent variables and the number of levels of each independent variable there are in the design. For example, a 2x3 factorial design has two independent variables (because there are two numbers in the description), the first variable having two levels and the second having three.

Main effects and interactions

The effects of

independent variables

Dependent and independent variables are variables in mathematical modeling, statistical modeling and experimental sciences. Dependent variables receive this name because, in an experiment, their values are studied under the supposition or deman ...

in factorial studies, taken singly, are referred to as main effects. This refers to the overall effect of an independent variable, averaging across all levels of the other independent variables. A main effect is the only effect detectable in a one-way design. Often more important than main effects are "interactions", which occur when the effect of one independent variable on a dependent variable depends on the level of a second independent variable. For example, the ability to catch a ball (dependent variable) might depend on the interaction of visual acuity (independent variable #1) and the size of the ball being caught (independent variable #2). A person with good eyesight might catch a small ball most easily, and person with very poor eyesight might do better with a large ball, so the two variables can be said to interact.

Within- and between-subjects designs

Two basic approaches to

research design

Research design refers to the overall strategy utilized to carry out research that defines a succinct and logical plan to tackle established research question(s) through the collection, interpretation, analysis, and discussion of data.

Incorporat ...

are within-subjects design and

between-subjects design. In within-subjects or repeated measures designs, each participant serves in more than one or perhaps all of the conditions of a study. In between-subjects designs each participant serves in only one condition of an experiment. Within-subjects designs have significant advantages over between-subjects designs, especially when it comes to complex factorial designs that have many conditions. In particular, within-subjects designs eliminate person confounds, that is, they get rid of effects caused by differences among subjects that are irrelevant to the phenomenon under study. However, the within-subject design has the serious disadvantage of possible sequence effects. Because each participant serves in more than one condition, the passage of time or the performance of an earlier task may affect the performance of a later task. For example, a participant might learn something from the first task that affects the second.

Research in Experimental Psychology

Experiments

The use of experimental methods was perhaps the main characteristic by which psychology became distinguishable from philosophy in the late 19th century. Ever since then experiments have been an integral part of most psychological research. Following is a sample of some major areas that use experimental methods. In experiments,

human participants often respond to visual, auditory or other stimuli, following instructions given by an experimenter; animals may be similarly "instructed" by rewarding appropriate responses. Since the 1990s, computers have commonly been used to automate stimulus presentation and behavioral measurement in the laboratory. Behavioral experiments with both humans and animals typically measure reaction time, choices among two or more alternatives, and/or response rate or strength; they may also record movements, facial expressions, or other behaviors. Experiments with humans may also obtain written responses before, during, and after experimental procedures.

Psychophysiological

Psychophysiology (from Greek , ''psȳkhē'', "breath, life, soul"; , ''physis'', "nature, origin"; and , '' -logia'') is the branch of psychology that is concerned with the physiological bases of psychological processes. While psychophysiology w ...

experiments, on the other hand, measure brain or (mostly in animals) single-cell activation during the presentation of a stimulus using methods such as

fMRI

Functional magnetic resonance imaging or functional MRI (fMRI) measures brain activity by detecting changes associated with blood flow. This technique relies on the fact that cerebral blood flow and neuronal activation are coupled. When an area o ...

,

EEG

Electroencephalography (EEG) is a method to record an electrogram of the spontaneous electrical activity of the brain. The biosignals detected by EEG have been shown to represent the postsynaptic potentials of pyramidal neurons in the neocortex ...

,

PET

A pet, or companion animal, is an animal kept primarily for a person's company or entertainment rather than as a working animal, livestock, or a laboratory animal. Popular pets are often considered to have attractive appearances, intelligence, ...

or similar.

Control of

extraneous variables

Dependent and independent variables are variables in mathematical modeling, statistical modeling and experimental sciences. Dependent variables receive this name because, in an experiment, their values are studied under the supposition or deman ...

, minimizing the potential for

experimenter bias Observer bias is one of the types of detection bias and is defined as any kind of systematic divergence from accurate facts during observation and the recording of data and information in studies. The definition can be further expanded upon to inclu ...

, counterbalancing the order of experimental tasks, adequate

sample size

Sample size determination is the act of choosing the number of observations or Replication (statistics), replicates to include in a statistical sample. The sample size is an important feature of any empirical study in which the goal is to make stat ...

, the use of

operational definitions

An operational definition specifies concrete, replicable procedures designed to represent a construct. In the words of American psychologist S.S. Stevens (1935), "An operation is the performance which we execute in order to make known a concept." F ...

, emphasis on both the

reliability

Reliability, reliable, or unreliable may refer to:

Science, technology, and mathematics Computing

* Data reliability (disambiguation), a property of some disk arrays in computer storage

* High availability

* Reliability (computer networking), a ...

and

validity

Validity or Valid may refer to:

Science/mathematics/statistics:

* Validity (logic), a property of a logical argument

* Scientific:

** Internal validity, the validity of causal inferences within scientific studies, usually based on experiments

** ...

of results, and proper

statistical analysis

Statistical inference is the process of using data analysis to infer properties of an underlying distribution of probability.Upton, G., Cook, I. (2008) ''Oxford Dictionary of Statistics'', OUP. . Inferential statistical analysis infers propertie ...

are central to experimental methods in psychology. Because an understanding of these matters is important to the interpretation of data in almost all fields of psychology, undergraduate programs in psychology usually include mandatory courses in

research

Research is "creativity, creative and systematic work undertaken to increase the stock of knowledge". It involves the collection, organization and analysis of evidence to increase understanding of a topic, characterized by a particular att ...

methods and

statistics

Statistics (from German language, German: ''wikt:Statistik#German, Statistik'', "description of a State (polity), state, a country") is the discipline that concerns the collection, organization, analysis, interpretation, and presentation of ...

.

A crucial experiment is an experiment that is intended to test several hypotheses at the same time. Ideally, one hypothesis may be confirmed and all the others rejected. However, the data may also be consistent with several hypotheses, a result that calls for further research to narrow down the possibilities.

A pilot study may be run before a major experiment, in order to try out different procedures, determine optimal values of the experimental variables, or uncover weaknesses in experimental design. The pilot study may not be an experiment as usually defined; it might, for example, consist simply of

self-reports.

In a

field experiment

Field experiments are experiments carried out outside of laboratory settings.

They randomly assign subjects (or other sampling units) to either treatment or control groups in order to test claims of causal relationships. Random assignment helps ...

, participants are observed in a naturalistic setting outside the laboratory. Field experiments differ from field ''studies'' in that some part of the environment (''field'') is manipulated in a controlled way (for example, researchers give different kinds of toys to two different groups of children in a nursery school). Control is typically more lax than it would be in a laboratory setting.

Other methods of research such as

case study

A case study is an in-depth, detailed examination of a particular case (or cases) within a real-world context. For example, case studies in medicine may focus on an individual patient or ailment; case studies in business might cover a particular fi ...

, interview,

opinion polls

An opinion poll, often simply referred to as a survey or a poll (although strictly a poll is an actual election) is a human research survey of public opinion from a particular sample. Opinion polls are usually designed to represent the opinions ...

and

naturalistic observation

Naturalistic observation, sometimes referred to as fieldwork, is a research methodology in numerous fields of science including ethology, anthropology, linguistics, the social sciences, and psychology, in which data are collected as they occur i ...

, are often used by psychologists. These are not experimental methods, as they lack such aspects as well-defined, controlled variables, randomization, and isolation from unwanted variables.

Cognitive psychology

Some of the major topics studied by cognitive psychologists are

memory

Memory is the faculty of the mind by which data or information is encoded, stored, and retrieved when needed. It is the retention of information over time for the purpose of influencing future action. If past events could not be remembered, ...

,

learning

Learning is the process of acquiring new understanding, knowledge, behaviors, skills, value (personal and cultural), values, attitudes, and preferences. The ability to learn is possessed by humans, animals, and some machine learning, machines ...

,

problem solving

Problem solving is the process of achieving a goal by overcoming obstacles, a frequent part of most activities. Problems in need of solutions range from simple personal tasks (e.g. how to turn on an appliance) to complex issues in business an ...

, and

attention

Attention is the behavioral and cognitive process of selectively concentrating on a discrete aspect of information, whether considered subjective or objective, while ignoring other perceivable information. William James (1890) wrote that "Atte ...

. Most cognitive experiments are done in a lab instead of a social setting; this is done mainly to provide maximum control of experimental variables and minimal interference from irrelevant events and other aspects of the situation. A great many experimental methods are used; frequently used methods are described on the main pages of the topics just listed. In addition to studying behavior, experimenters may use EEG or fMRI to help understand how the brain carries out cognitive processes, sometimes in conjunction with

computational modelling

Computer simulation is the process of mathematical modelling, performed on a computer, which is designed to predict the behaviour of, or the outcome of, a real-world or physical system. The reliability of some mathematical models can be deter ...

. They may also study patients with focal brain damage or neurologic disease (see

cognitive neuropsychology

Cognitive neuropsychology is a branch of cognitive psychology that aims to understand how the structure and function of the brain relates to specific psychological processes. Cognitive psychology is the science that looks at how mental processes ...

) or use brain stimulation techniques like

transcranial magnetic stimulation

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is a noninvasive form of brain stimulation in which a changing magnetic field is used to induce an electric current at a specific area of the brain through electromagnetic induction. An electric pulse gener ...

to help confirm the causal role and specific functional contribution of neural regions or modules.

Animal cognition

Animal cognition refers to the mental capacities of non-human animals, and research in this field often focuses on matters similar to those of interest to cognitive psychologists using human participants. Cognitive studies using animals can often control conditions more closely and use methods not open to research with humans. In addition, processes such as conditioning my appear in simpler form in animals, certain animals display unique capacities (such as echo location in bats) that clarify important cognitive functions, and animal studies often have important implications for the survival and evolution of species.

Sensation and perception

Experiments on sensation and perception have a very long history in experimental psychology (see History above). Experimenters typically manipulate stimuli affecting vision, hearing, touch, smell, taste and proprioception. Sensory measurement plays a large role in the field, covering many aspects of sensory performance - for example, minimum discriminable differences in brightness or the detection of odors; such measurement involves the use of instruments such as the oscillator, attenuator, stroboscope, and many others listed earlier in this article. Experiments also probe subtle phenomena such as visual illusions, or the emotions aroused by stimuli of different sorts.

Behavioral psychology

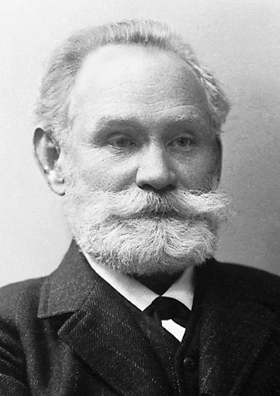

The behavioristic approach to psychology reached its peak of popularity in the mid-twentieth century but still underlies much experimental research and clinical application. Its founders include such figures as

Ivan Pavlov

Ivan Petrovich Pavlov ( rus, Ива́н Петро́вич Па́влов, , p=ɪˈvan pʲɪˈtrovʲɪtɕ ˈpavləf, a=Ru-Ivan_Petrovich_Pavlov.ogg; 27 February 1936), was a Russian and Soviet experimental neurologist, psychologist and physiol ...

,

John B. Watson

John Broadus Watson (January 9, 1878 – September 25, 1958) was an American psychologist who popularized the scientific theory of behaviorism, establishing it as a psychological school.Cohn, Aaron S. 2014.Watson, John B." Pp. 1429–1430 in ''T ...

, and

B.F. Skinner

Burrhus Frederic Skinner (March 20, 1904 – August 18, 1990) was an American psychologist, behaviorist, author, inventor, and social philosopher. He was a professor of psychology at Harvard University from 1958 until his retirement in 1974.

...

. Pavlov's experimental study of the digestive system in dogs led to extensive experiments through which he established the basic principles of classical conditioning. Watson popularized the behaviorist approach to human behavior; his experiments with

Little Albert

The Little Albert experiment was a controlled experiment showing empirical evidence of classical conditioning in humans. The study also provides an example of stimulus generalization. It was carried out by John B. Watson and his Doctoral stude ...

are particularly well known. Skinner distinguished

operant conditioning

Operant conditioning, also called instrumental conditioning, is a learning process where behaviors are modified through the association of stimuli with reinforcement or punishment. In it, operants—behaviors that affect one's environment—are c ...

from

classical conditioning

Classical conditioning (also known as Pavlovian or respondent conditioning) is a behavioral procedure in which a biologically potent stimulus (e.g. food) is paired with a previously neutral stimulus (e.g. a triangle). It also refers to the learni ...

and established the experimental analysis of behavior as a major component in the subsequent development of experimental psychology.

Social psychology

Social psychologists use both empirical research and experimental methods to study the effects of social interactions on individuals' thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Social psychologists use experimental methods, both within and outside the laboratory, and there have been several key experiments done in the past few centuries. The Triplett experiment, one of the first social psychology experiments conducted in 1898 by

Norman Triplett, noticed that the presence of others had an effect on children's performance times. Other widely cited experiments in social psychology are projects like

the Stanford prison experiment conducted by

Philip Zimbardo

Philip George Zimbardo (; born March 23, 1933) is an American psychologist and a professor emeritus at Stanford University. He became known for his 1971 Stanford prison experiment, which was later severely criticized for both ethical and scient ...

in 1971 and the

Milgram obedience experiment by

Stanley Milgram

Stanley Milgram (August 15, 1933 – December 20, 1984) was an American social psychologist, best known for his controversial experiments on obedience conducted in the 1960s during his professorship at Yale.Blass, T. (2004). ''The Man Who Shocke ...

. In both experiments ordinary individuals were induced to engage in remarkably cruel behavior, suggesting that such behavior could be influenced by social pressure. Zimbardo's experiment noted the effect of conformity to specific roles in society and the social world. Milgram's study looked at the role of authority in shaping behavior, even when it had adverse effects on another person. Because of possible negative effects on the participants, neither of these experiments could be legally performed in the United States today. These two experiments also took place during the era prior to the existence of IRBs, and most likely played a role in the establishment of such boards

Experimental instruments

Instruments used in experimental psychology evolved along with technical advances and with the shifting demands of experiments. The earliest instruments, such as the Hipp Chronoscope and the kymograph, were originally used for other purposes. The list below exemplifies some of the different instruments used over the years. These are only a few core instruments used in current research.

Hipp chronoscope / chronograph

This instrument, invented by

Matthäus Hipp

Matthäus Hipp also spelled Matthias or Mathias (Blaubeuren, 25 October 1813 – 3 May 1893 in Fluntern) was a German clockmaker and inventor who lived from 1852 on in Switzerland.

His most important, lastingly significant inventions were ele ...

around 1850, uses a vibrating reed to tick off time in 1000ths of a second. Originally designed for experiments in physics, it was later adapted to study the speed of bullets. After then being introduced to physiology, it was finally used in psychology to measure reaction time and the duration of mental processes.

Stereoscope

The first stereoscope was invented by Wheatstone in 1838. It presents two slightly different images, one to each eye, at the same time. Typically the images are photographs of the same object taken from camera positions that mimic the position and separation of the eyes in the head. When one looks through the stereoscope the photos fuse into a single image that conveys a powerful sense of depth and solidity.

Kymograph

Developed by

Carl Ludwig

Carl Friedrich Wilhelm Ludwig (; 29 December 1816 – 23 April 1895) was a German physician and physiologist. His work as both a researcher and teacher had a major influence on the understanding, methods and apparatus used in almost all branches ...

in the 19th century, the kymograph is a revolving drum on which a moving stylus tracks the size of some measurement as a function of time. The kymograph is similar to the polygraph, which has a strip of paper moving under one or more pens. The kymograph was originally used to measure blood pressure and it later was used to measure muscle contractions and speech sounds. In psychology, it was often used to record response times.

Photokymographs

This device is a photographic recorder. It used mirrors and light to record the photos. Inside a small box with a slit for light there are two drive rollers with film connecting the two. The light enters through the slit to record on the film. Some photokymographs have a lens so an appropriate speed for the film can be reached.

Galvanometer

The galvanometer is an early instrument used to measure the strength of an electric current. Hermann von Helmholtz used it to detect the electrical signals generated by nerve impulses, and thus to measure the time taken by impulses to travel between two points on a nerve.

Audiometer

This apparatus was designed to produce several fixed frequencies at different levels of intensity. It could either deliver the tone to a subject's ear or transmit sound oscillations to the skull. An experimenter would generally use an audiometer to find the auditory threshold of a subject. The data received from an audiometer is called an audiogram.

Colorimeters

These determine the color composition by measuring its tricolor characteristics or matching of a color sample. This type of device would be used in visual experiments.

Algesiometers and algometers

Both of these are mechanical stimulations of pain. They have a sharp needle-like stimulus point so it does not give the sensation of pressure. Experimenters use these when doing an experiment on analgesia.

Olfactometer

An olfactometer is any device that is used to measure the sense of smell. The most basic type in early studies was placing a subject in a room containing a specific measured amount of an odorous substance. More intricate devices involve some form of sniffing device, such as the neck of a bottle. The most common olfactometer found in psychology laboratories at one point was the Zwaardemker olfactometer. It had two glass nasal tubes projecting through a screen. One end would be inserted into a stimulus chamber, the other end is inserted directly into the nostrils.

Mazes

Probably one of the oldest instruments for studying memory would be the maze. The common goal is to get from point A to point B, however the mazes can vary in size and complexity. Two types of mazes commonly used with rats are the radial arm maze and the Morris water maze. The

radial arm maze

The radial arm maze was designed by Olton and Samuelson in 1976 to measure spatial learning and memory in rats. The original apparatus consists of eight equidistantly spaced arms, each about 4 feet long, and all radiating from a small circular cen ...

consists of multiple arms radiating from a central point. Each arm has a small piece of food at the end. The Morris water maze is meant to test spatial learning. It uses a large round pool of water that is made opaque. The rat must swim around until it finds the escape platform that is hidden from view just below the surface of the water.

Electroencephalograph (EEG)

The EEG is an instrument that can reflect the summed electrical activity of neural cell assemblies in the brain. It was originally used as an attempt to improve medical diagnoses. Later it became a key instrument to psychologists in examining brain activity and it remains a key instrument used in the field today.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI)

The fMRI is an instrument that can detect changes in blood oxygen levels over time. The increase in blood oxygen levels shows where brain activity occurs. These are rather bulky and expensive instruments which are generally found in hospitals. They are most commonly used for cognitive experiments.

Positron emission tomography (PET)

PET is also used to look at brain activity. It can detect drugs binding neurotransmitter receptors in the brain. A down side to PET is that it requires radioisotopes to be injected into the body so the brain activity can be mapped out. The radioisotopes decay quickly so they do not accumulate in the body.

Eye tracking

Eye trackers are used to measure where someone is looking or how their eyes are moving relative to the head. Eye trackers are used in the study of visual perception and--because people typically direct their attention to the place they are looking--also to provide directly observable measures of attention.

Criticism

Frankfurt school

One school opposed to experimental psychology has been associated with the Frankfurt School, which calls its ideas "

Critical Theory

A critical theory is any approach to social philosophy that focuses on society and culture to reveal, critique and challenge power structures. With roots in sociology and literary criticism, it argues that social problems stem more from soci ...

."

s claim that experimental psychology approaches humans as entities independent of the cultural, economic, and historical context in which they exist. These contexts of human mental processes and behavior are neglected, according to critical psychologists, like

Herbert Marcuse

Herbert Marcuse (; ; July 19, 1898 – July 29, 1979) was a German-American philosopher, social critic, and political theorist, associated with the Frankfurt School of critical theory. Born in Berlin, Marcuse studied at the Humboldt University ...

. In so doing, experimental psychologists paint an inaccurate portrait of human nature while lending tacit support to the prevailing social order, according to critical theorists like

Theodor Adorno

Theodor is a masculine given name. It is a German form of Theodore. It is also a variant of Teodor.

List of people with the given name Theodor

* Theodor Adorno, (1903–1969), German philosopher

* Theodor Aman, Romanian painter

* Theodor Blueger, ...

and

Jürgen Habermas

Jürgen Habermas (, ; ; born 18 June 1929) is a German social theorist in the tradition of critical theory and pragmatism. His work addresses communicative rationality and the public sphere.

Associated with the Frankfurt School, Habermas's wor ...

(in their essays in ''The Positivist Debate in German Sociology'').

See also

*

Empirical psychology

*

List of psychological laboratories

*

Outline of psychology

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to psychology:

Psychology refers to the study of subconscious and conscious activities, such as emotions and thoughts. It is a field of study that bridges the scientific and ...

*

Psychonomic Society

The Psychonomic Society is an international scientific society of over 4,500 scientists in the field of experimental psychology. The mission of the Psychonomic Society is to foster the science of cognition through the advancement and communicati ...

*

Sackett self-selection circus

*

Society of Experimental Psychologists

The Society of Experimental Psychologists (SEP), originally called the Society of Experimentalists, is an academic society for experimental psychologists. It was founded by Edward Bradford Titchener in 1904 to be an ongoing workshop in which memb ...

Notes

References

*

*

{{Authority control

Mathematical and quantitative methods (economics)

Experimental psychology emerged as a modern academic discipline in the 19th century when

Experimental psychology emerged as a modern academic discipline in the 19th century when

With his student

With his student  The behavioristic approach to psychology reached its peak of popularity in the mid-twentieth century but still underlies much experimental research and clinical application. Its founders include such figures as

The behavioristic approach to psychology reached its peak of popularity in the mid-twentieth century but still underlies much experimental research and clinical application. Its founders include such figures as